An Appliance of Science in Art Historical Studies

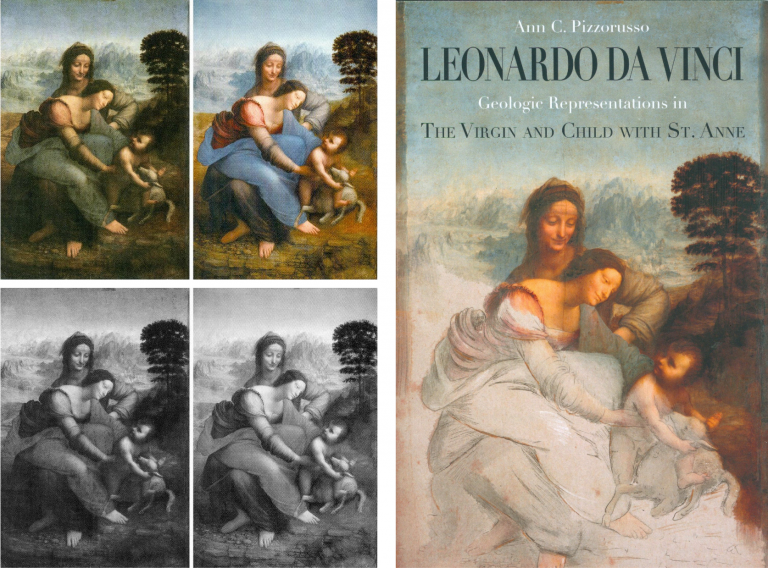

A slim but eloquent and persuasive study of the assorted depictions of rock in Leonardo’s The Virgin and Child with St. Anne examines the pictorial means of the most perplexing figural invention in the artist’s oeuvre.

Above, Fig. 1: Left, Leonardo’s The Virgin and Child with St. Anne as seen before after its recent controversial cleaning at the Louvre; right, Ann Pizzorusso’s latest book – Cover design: Francesco Filippini.

This volume is slim because its material is handled with deft and engaging concision. Whether a bright child, a lay adult, or a professional art historian, the reader will enjoy and profit from this vivid journey through time and Italy – its geography; its mountains; its fauna, and, its most famous, multi-talented artist. As one Leonardo specialist puts it:

“The thrilling focus put by Ann Pizzorusso’s researches on the geology of Leonardo’s landscapes in works such as the Virgin of the Rocks and the Louvre’s The Virgin and Child with St. Anne is of foremost importance. Pizzorusso’s analyses and synthetic, clear explanations, help us better to understand Leonardo’s amazing attachment to a truthful, scientific-like, investigation into the world in which we live. Retrospectively, it also helps to see the Master at work concretely in his quest for perfection.” – Jacques Franck

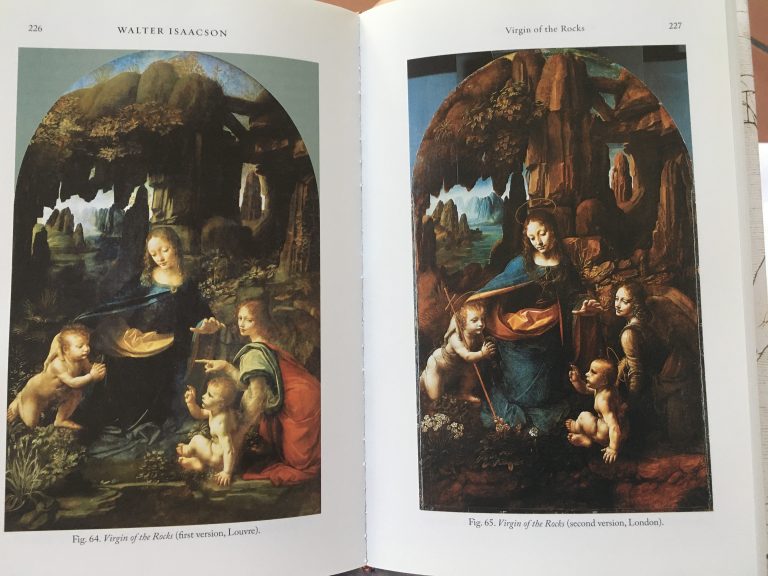

(Ann Pizzorusso‘s work was cited extensively in the geology sections of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo, Leonardo da Vinci – see Fig. 5, below.)

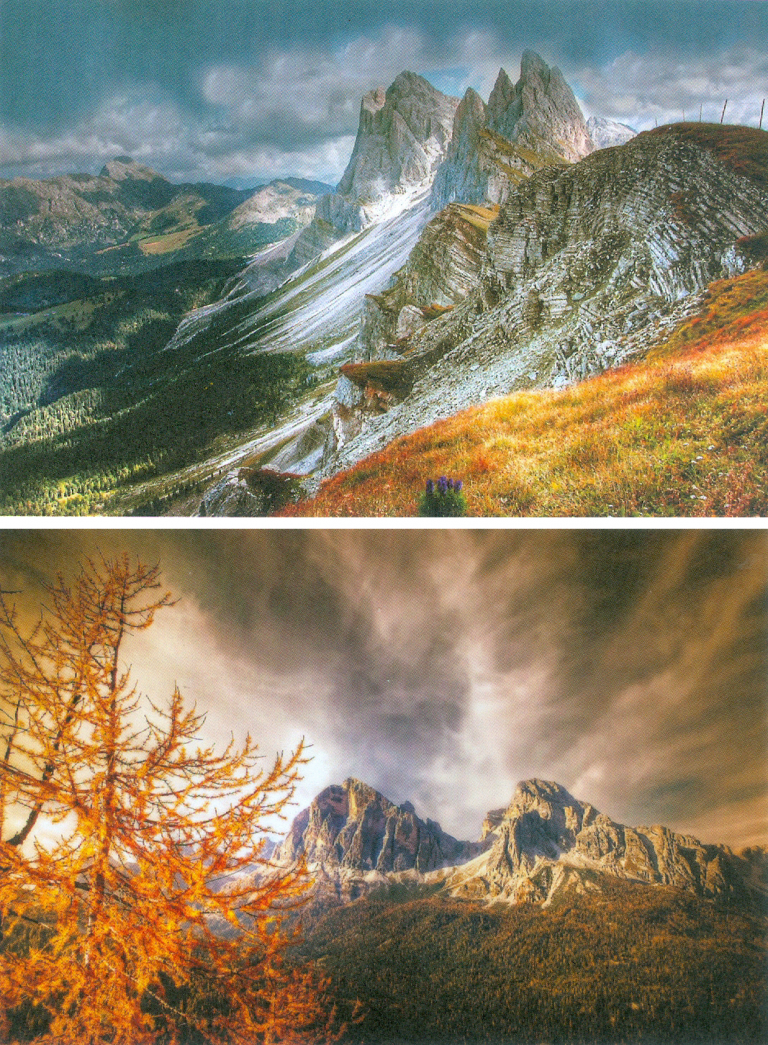

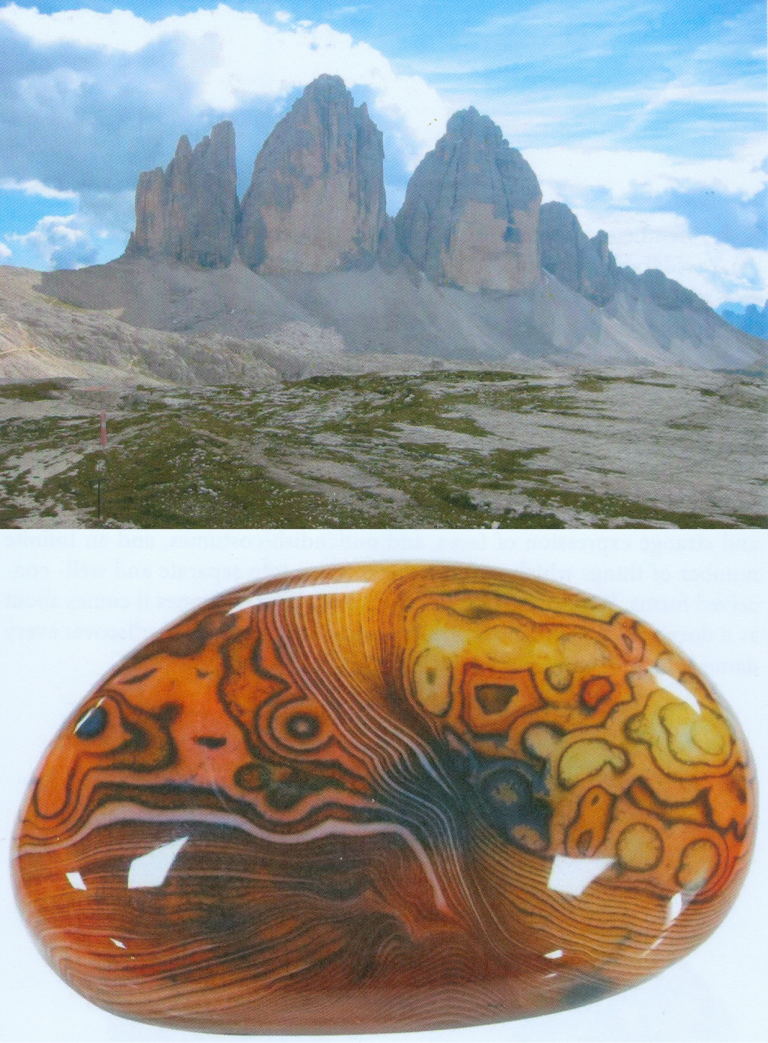

Above, Figs. 2, 3 and 4: A section of Pizzorusso’s focussed geological and botanical illustrations that run from the general to the very particular.

In current Leonardo art scholarship there are two practitioners who lay claim to direct scientific expertise. The first, Professor Martin Kemp, studied natural science at Downing College, Cambridge, with the aim of becoming a biologist but then, as he put it in his 2018 memoir Living with Leonardo, “steadily lost impetus in my studies of science” and “was drawn” into film, the visual arts and music. The second, Ann C. Pizzorusso, trained all the way through to qualifying and practicing as a geologist – but then, in the mid-1990s, “After many years of doing virtually everything in the world of geology – drilling for oil, hunting for gems, cleaning up pollution in soil and groundwater…” turned her skills towards Leonardo. Her debut article, “Leonardo’s Geology: The Authenticity of the Virgin of the Rocks” (Leonardo Magazine, Vol. 29, No, 1996, pp. 197-200 – Leonardo is a peer-reviewed academic journal published by the MIT Press) was a bomb that still reverberates.

THE TWO VIRGIN OF THE ROCKS PAINTINGS

Pizzorusso’s game-changing contention that shortcomings of scientific understanding evident in the geological and botanical descriptions in the National Gallery version of the Virgin of the Rocks were disqualifying, was well summarized and illustrated in the Guardian in 2014 (“The daffodil code: doubts revived over Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks in London”).

In her essay, Pizzorusso said of the National Gallery version:

“An observer with some knowledge of geology would find that the rock formations…do not correspond to nature; most of Leonardo’s drawings and paintings do. It seems unlikely that Leonardo would have violated his knowledge of geology in favour of abstract representation, considering that he executed an even more geologically complex picture – the “Virgin and St. Anne” (1510) – after he had completed the National Gallery painting.”

In so claiming, Pizzorusso lent belated technical support to Kenneth Clark, whose aesthetically appraised views on the authorship of the National Gallery’s second and later version of the Virgin of the Rocks had been carried in the 1938 book One Hundred details of Pictures in the National Gallery when Clark was the gallery’s director. His views on the picture’s (contested) authenticity were expressed as follows:

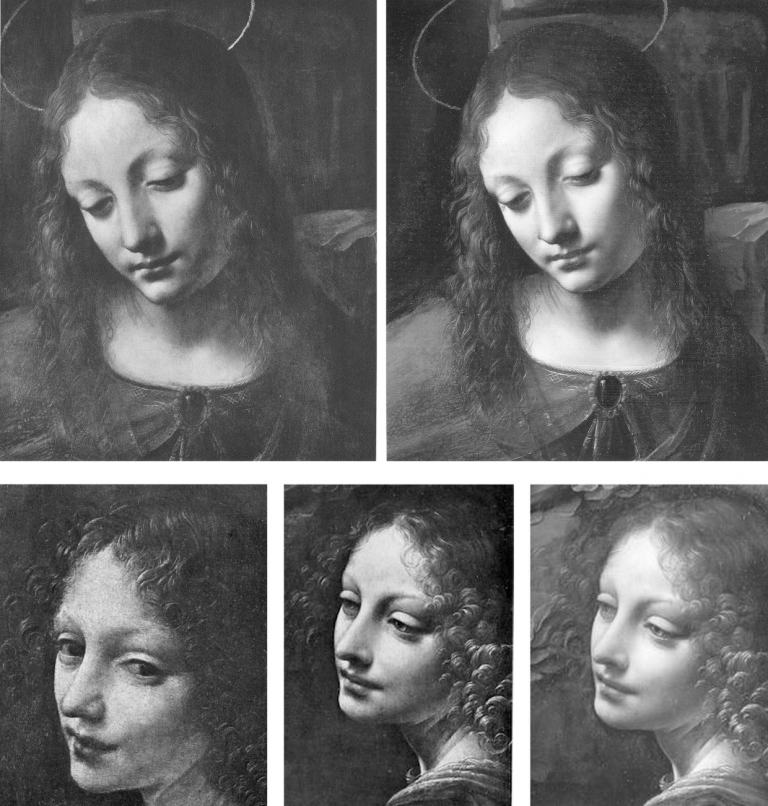

“There is no longer any doubt that the National Gallery’s Virgin of the Rocks is a second version of the subject undertaken by Leonardo some twenty years after the picture in the Louvre… It is uncertain how much of this replica he executed with his own hand, and this head of the Virgin is the most difficult part of the problem. It is too heavy and lifeless for Leonardo and the actual type is un-Leonardoesque [see Fig. 6 below, top left]; yet it seems to be painted in exactly the same technique as the angel’s head in the same picture [Fig. 6 bottom, centre]; and that is so perfect that surely Leonardo must have had a hand in it. Both show curious marks of palm and thumb (they are visible in this detail on the bridge of the Virgin’s nose) made when the paint was wet and no doubt covered by glazes long since removed [by restorers]. This perhaps is a clue to the problem. A pupil did the main work of drawing and modelling, and before his paint was dry Leonardo put in the finishing touches. Most of these have been removed from the Virgin’s face but remain in the angel’s, where perhaps they were always more numerous”

In 1990 the National Gallery republished Clark’s book with new photographs. The then director, Neil MacGregor, made two memorable comments in his foreword. The first concerned the testimony of photographs. Clark, MacGregor acknowledged, had been “fearful of what might be found if the golden veils of dirt and varnish were ever to be removed. In the years since, many have been…The reader who can compare the earlier edition with this one will decide how much is gain, how much loss.” (Emphasis added – that was the last time National Gallery staff admitted the indispensable value of photo-testimony in appraisals of restorations.) In a 1990 edition footnote, it was further conceded on the differences Clark had described between the Virgin’s and the angel’s head that: “As a result of the cleaning of the altarpiece in 1949 the differences between the heads are perhaps less apparent.” That tacit confession that such work as had recently testified to Leonardo’s partial/minimal involvement in the picture had perished in the restoration, did nothing to dissuade the gallery from further restoring the painting just eighteen years later.

Clark had seen no evidence whatsoever of Leonardo’s hand in the handling of the rocks and the plants, and Pizzorusso’s (above) charge highlights the fact that the handling of those subjects in this painting was markedly sloppier than in both Leonardo’s earlier and later outputs, as seen, respectively, in the Paris Virgin of the Rocks and the Paris Virgin and Child with St. Anne. For its part, the National Gallery perseveres with a conviction that its second (2008-9) restoration in barely more than half a century had dug sufficiently deep to uncover an entirely autograph Leonardo painting.

Above, Fig. 6: Top, the Virgin in the London Virgin of the Rocks as seen (left) in 1938 and (right) in 1990; above, left, the angel in Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks in the Louvre; centre and right, the angel in the National Gallery’s version, as seen in 1938 (centre) and (right) in 1990 and after its 1949 restoration.

MAPPING THE WORLD

In her Leonardo da Vinci cartographer and Inventor of the Google Map, Pizzorusso holds that:

“We can access any location on Earth with a simple click on our computer or cell phone. This wasn’t always the case, but it was always a desire, for man has continually sought to understand the extent of the Earth and his place on it. While this is not a treatise on the history of cartography, it will serve to show the vital importance of maps and the little known, but extraordinary accomplishments of Leonardo da Vinci as a Renaissance cartographer. Since many examples of his maps survive today, (with an extensive collection in the Royal Collection Library at Windsor Castle), we can appreciate not only his skill, but the instruments he invented to achieve nearly perfect accuracy in his measurements. He melded his knowledge of geology, engineering, surveying, hydrology, and of course art to revolutionize cartography. We can see his innovations on every map we use today and can even name him the inventor of the Google Map.”

A NOTORIOUSLY PRECARIOUS GROUPING

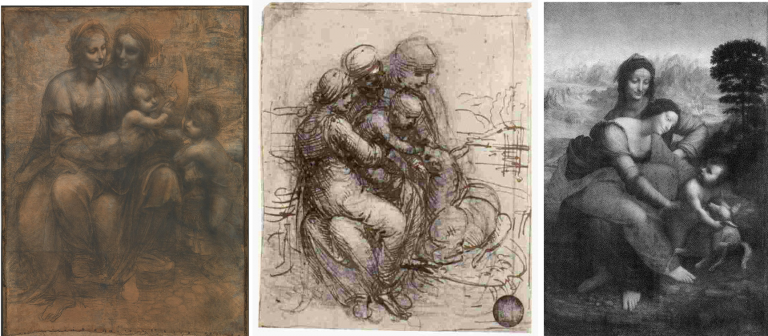

Above, Fig. 7: Left, Leonardo’s The Virgin and Child with St Anne drawing (the Burlington House Cartoon); centre, Leonardo’s (Venice – Gallerie dell’Accademia) study for The Virgin and Child with St Anne,;right, the Louvre’s Virgin and Child with St Anne before its recent restoration – see Pizzorusso’s 12 June 2012 “Could the Louvre’s ‘Virgin and St. Anne’ provide the proof that the (London) National Gallery’s ‘Virgin of the Rocks’ is not by Leonardo da Vinci?

In her latest book, Leonardo da Vinci – Geologic Representations in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Pizzorusso presses an appreciation of Leonardo’s understanding of geology and botany into an examination of the vexing figural complexities of Leonardo’s Virgin and St. Anne:

“In discussing the figure of the Virgin, Carlo Pedretti states that ‘Critics have often wondered why Leonardo should have abandoned the most satisfactory Classical sense of balance achieved in the London Burlington House Cartoon in favour of a pose that has always been taken as conveying a sense of uneasiness’. Bernard Berenson summarized his dismay with Leonardo’s treatment of St Anne as follows; ‘Seated on no visible or inferable support, she (St. Anne) in turn on her left knee sustained the restless weight of a daughter as heavy as herself.’”

And the resolution of the conundrum? It begins: “Had Berenson known his geology, he would have seen that…” The that is for the reader to discover.

The book is available worldwide, both in Kindle ebook form and in Paperback at Amazon UK and Amazon US Pizzorusso’s website is: Ann Pizzorusso – annpizzorusso.com .

Michael Daley, 12 May 2021

Leave a Reply