ArtWatch at Thirty, Part II: The Artful Promotion of the World’s Worst Restorations

15 APRIL 2023. MICHAEL DALEY WRITES:

In Part I we set the 1980-1994 cleaning of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes in the era’s ambitiously experimental and accident-prone restorations. Here, we examine the art-historically untenable scholarship that arose when Michelangelo’s debilitated frescoes were endorsed as if constituting revelations that merited a rewritten history of art. Three decades on, identifying and examining the polished art-political stratagems that draw so many scholars and art critics into supporting egregiously destructive restorations remains a matter of professional urgency.

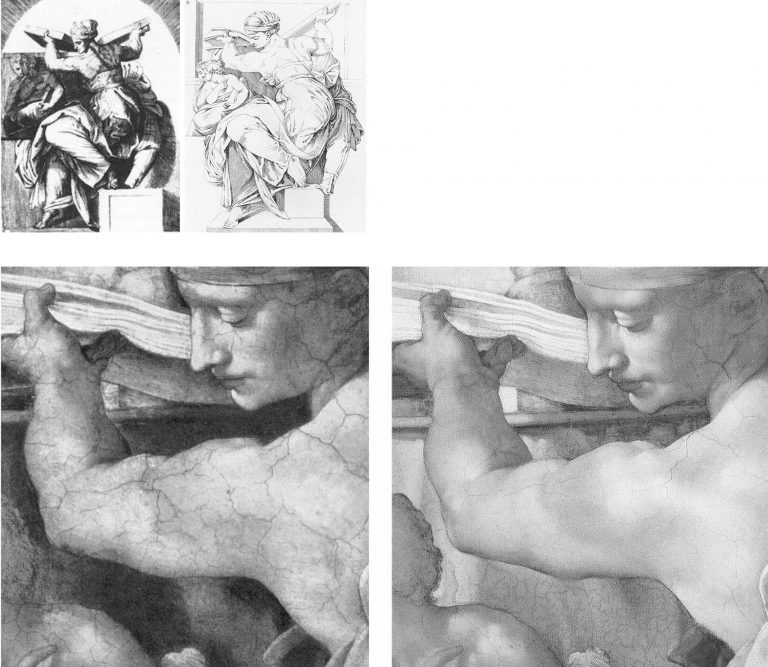

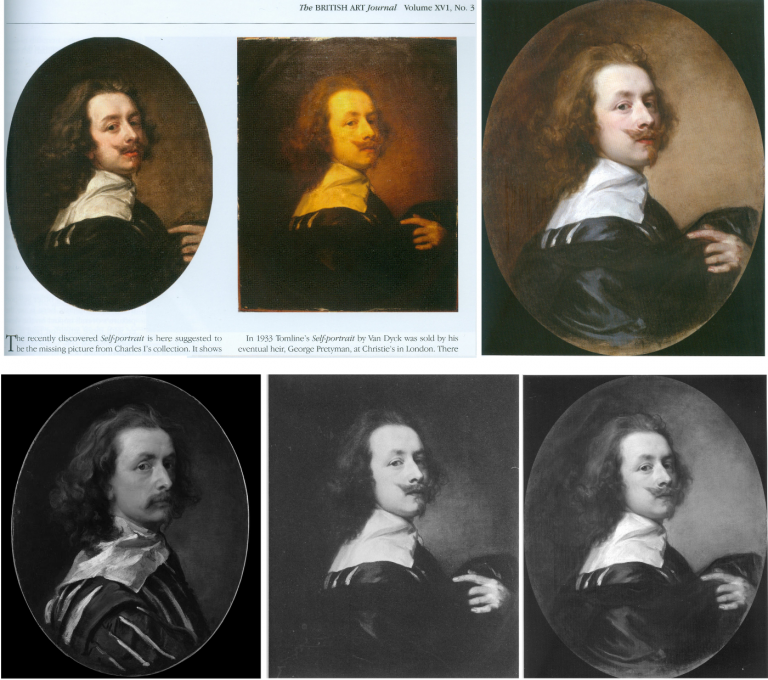

Above, Fig. 1, Top: National Geographic’s iconic photo-record of the Sistine Chapel ceiling which captured the last moments of the most acclaimed late stage of Michelangelo’s painting, including his The Crucifixion of Haman, the Prophet Jonah, and the Libyan Sibyl. Above, the post-cleaning, LED-lit chapel. When unveiled in 1512, the then brilliantly lit and shaded figures set in deep architectural spaces were eulogised for having made surfaces which physically advanced towards the viewer recede optically through Michelangelo’s powers of design and unprecedented deployment of lights and shades. At the time, no one spoke of Michelangelo’s colour – “brilliant” or otherwise.

TWIN AND CROSS-LINKED ASSAULTS ON A CRITIC

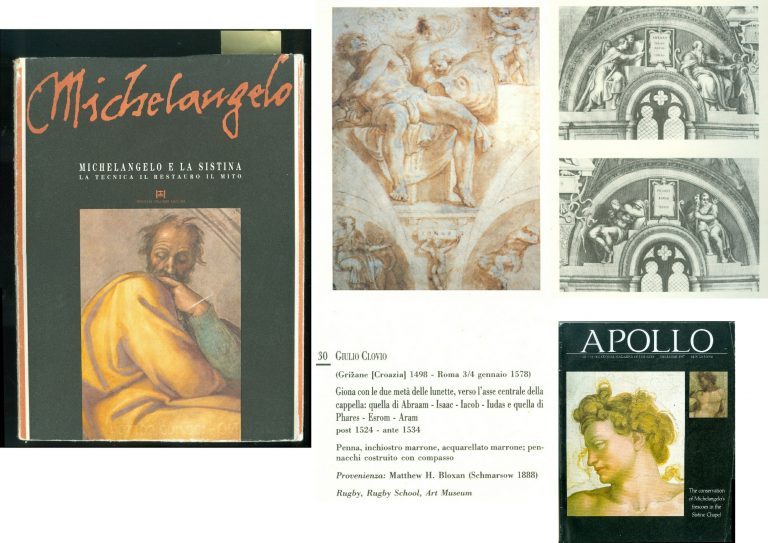

On 8 October 1987, halfway through the cleaning of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling, the restoration’s leading scholarly critic, Professor James Beck, Chairman of Columbia University’s Art History and Archaeology Department, was branded the “most culpable of the critics” by Sir John Pope-Hennessy in the New York Review of Books (“Storm Over the Sistine Ceiling”). Two months later, that attack was followed by another in the December Apollo magazine by Kathleen Weil-Garris Brandt (“Twenty-five Questions about Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling”). Like Pope-Hennessy, Brandt was a professor of Renaissance art at New York University’s post-graduate art history school, The Institute of Fine Arts (which incorporates a Samuel H. Kress Program-sponsored conservation department), and she was considered a long-standing friend by him.

Brandt characterised the restoration’s critics as “a tiny, heterogenous and vociferous cadre”. She likened their arguments to “the wild cries of some ferocious mutant of Chicken Little” and added “Many believe that the critics, like that benighted bird, were misunderstanding insufficient evidence, to draw mistaken conclusions to the alarm and detriment of the neighbours.” She conceded the issue “is a serious one” but only the better to sting: “Are the critics merely opportunists, bodysurfing in a wave of publicity they would never otherwise have enjoyed?” In his 2016 memoir, Michelangelo and I, Gianluigi Colalucci, the restorer/co-director of the Sistine Chapel restorations, described Brandt as “sweet and gentle in appearance but with a character of steel” who, having “obtained her own office in the museum complex”, had “put just about everybody under pressure with her inflexible activity”.

“THINGS ARE NOT AS YOU THINK”

There were degrees of hypocrisy in both attacks. Pope-Hennessy’s charge of professional culpability had followed his invitation to Beck to serve on a Metropolitan Museum Advisory Committee. As Colalucci would later disclose, Brandt’s denigration was not made as the self-effacing and disinterested scholar she had implied in Apollo – “Like many Renaissance scholars, I have held a kind of informal watching brief for the cleaning operation since its inception in 1981 [sic] and I talk on the subject with groups and individuals of all kinds.” Formally speaking, Brandt had two dogs in this fight. First, she had obtained her Vatican office as the official spokesman on “Scholarly and General information” for Arts and Communications Counsellors, a division of the New York Public Relations firm Ruder and Finn Inc. which had been retained by the Vatican to handle the restoration crisis. Second, she was a member of a shadowy, secretive scientific advisory committee the Vatican had set up, ostensibly, to monitor the controversial restoration. On learning of that committee, Colalucci threatened to resign but was dissuaded by his restoration co-director, Fabrizio Mancinelli, who urged him to calm down because: “You’ll see that things are not as you think…” In due course, Colalucci recalled, “we were given to understand that the findings were positive”.

As will be shown in Part III, the ploy of an institutionally self-appointed, supposedly invigilating but intended exonerating body, had been honed at the National Gallery in 1947 and 1967. Given the importance of the greatest art, whenever major restorations are started, they must, of political necessity, be defended unequivocally for the duration and at length thereafter, for fear of triggering institutional melt-downs. When a restoration of sacred art in a sacred place is funded in advance by a foreign corporation in a commercial exchange for film and photography rights, any admission of error becomes doubly inconceivable. Little surprise therefore that, as Colalucci disclosed, the Vatican’s own scientific advisory committee remained in place as a supportive “working group” throughout the entire restoration of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes. Headed by André Chastel, this group’s members, in addition to Brandt, were:

“Carlo Bertelli of Lausanne University, initiator of the restoration of Leonardo’s Last Supper executed by Pinin Brambilla [See: The Perpetual Restoration of Leonardo’s Last Supper, Part I: The Law of Diminishing Returns]; Pierluigi De Vecchi, an expert on Michelangelo; Sydney J. Freedburg from Washington; Giovanni Urban[i] former director ICR [the Istituto Centrale di Restauro]; Luitpold Frommell and Matthias Winner, directors of the Bibliotecca Hertziana in Rome; Umberto Baldini, director of the ICR [and head of the Brancacci Chapel restoration]; Michael Hirst, an expert on Michelangelo’s drawings; John Shearman, an expert on Raphael and the Sistine Chapel…The restorers were Alfio Del Serra from Florence…and Paul Schwartzbaum from New York, head of the ICCROM school and projects in Rome. Norbert Baer from New York University was the only chemist.”

THE SAMUEL H. KRESS FOUNDATION INTERVENTION

Colalucci aired a secondary grievance concerning the advisory committee in 2016: “By express desire of Chastel and the other members, we were not allowed to inform the press of the work of this group of experts, even though it would have been of great benefit to us because” [the quasi-invigilators] “wished to keep a low profile and avoid the attention of the already overly excited public opinion”. However, “Shortly afterwards, Marilyn Perry, the pleasant and dynamic president of the Kress Foundation, set up another working group, this time consisting almost exclusively of restorers on her own initiative.”

“The members were Mario Modestini, the foremost restorer in America; John Brealey, director of the restoration department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the young Dianne Dwyer, then assistant to John Brealey [see Fig. 11 below]; Andrea Rothe, director of the restoration department of the J. P. Getty Museum in Malibu; David Bull, director of the restoration department of the National Gallery in Washington [see Figs. 2 and 3 below]; and Leonetto Tintori, a highly skilled restorer from Florence [see Fig. 3 below].

“The group’s task was to monitor our work, give advice and put forward criticisms. The [single] meeting was very fruitful and ended positively with a report drawn up [by] the members of the group aimed in particular at public opinion in the United States.”

The resulting open letter from this committee to the American press executed its expressly intended effect to perfection. In April 1987, Time’s art critic, Robert Hughes, claimed:

“…most experts on Renaissance art, and on Michelangelo in particular, strongly endorse it and reject out of hand the anti’s allegation of haste or insufficient study…Last week a further vote of confidence came from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, a long-established non-profit organisation concerned with the care and preservation of Italian art. Six of the world’s leading conservators… reported in an open letter that the ‘new freshness of the colours and the clarity of the forms on the Sistine Ceiling, totally in keeping with 16th century Italian painting, affirm the full majesty and splendor of Michelangelo’s creation’”

John Russell reported in the New York Times:

“An international Group of leading conservators of Italian paintings has given its unanimous and strongly enthusiastic approval to the current restoration of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel in Rome…Though not intended as a riposte to recent criticism of the restoration the report could be said to rebut the attacks that have been made upon it. Among those who have opposed the restoration are Prof. James Beck of Columbia, Alexander Eliot, formerly of Time Inc. and a group of 14 American artists who asked the Pope to halt the work…”

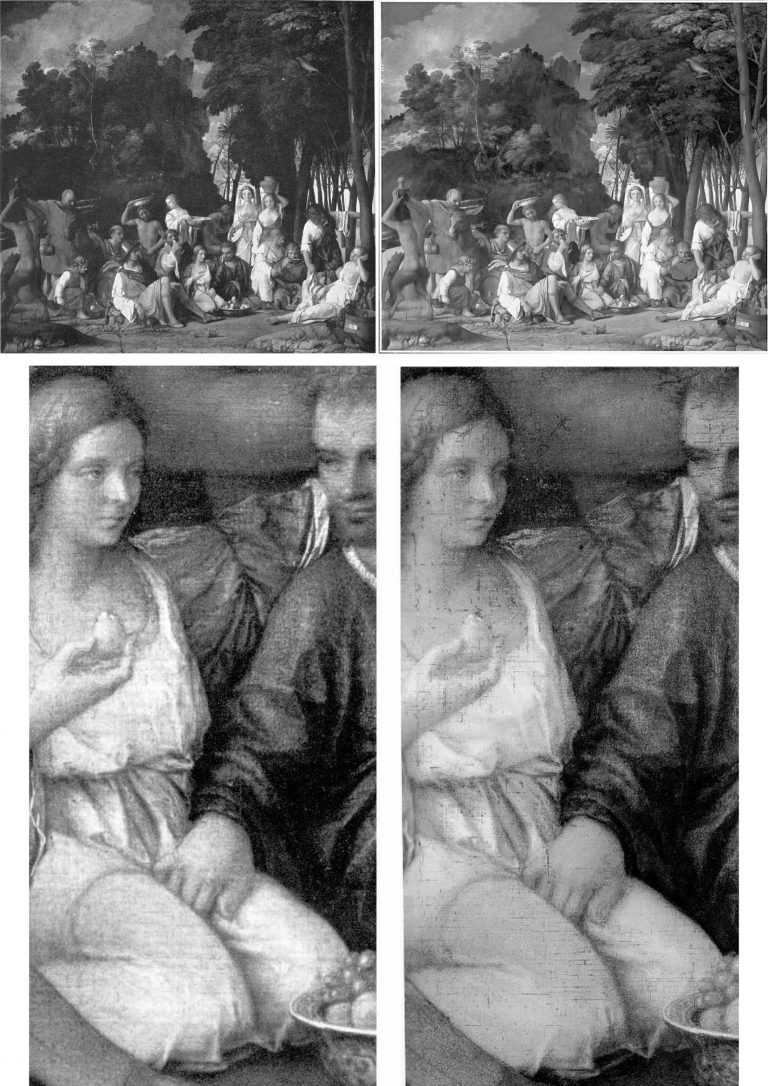

Above, Fig. 2: Top, the David Bull-restored Bellini/Titian Feast of the Gods, (before cleaning, left; after cleaning, right); below, a detail before cleaning, left, and immediately after cleaning, right. If Bull had simply removed a discoloured film of varnish, the previously discernible tonal values would have emerged enhanced – and not, as seen, diminished, compressed, and with a flattening of previously tangible forms. Such losses were Bull’s forte: when he restored Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights (Fig. 3, below), one of the picture’s two distressed steamboats disappeared and its plume of once-black smoke was painted into a waterspout. (When that restorations-wrecked picture was sent to the UK on a tour, credulous British art critics took their lead from a Tate Gallery press release and gushingly proclaimed it “One of the stars of the show”.)

Above, Fig. 3: Left, Turner’s painting of two steamboats in distress, “Rockets and Blue Lights…” as seen in: 1896 (top); 1934 after restoration by William Suhr (centre); 2003 after restoration by David Bull (above). Right, Massacio’s Holy Trinity in the Santa Maria Novella, Florence, after restoration by Leonetto Tintori.

SUCKERED ART CRITICS

Where the Kress Committee’s open letter achieved immediate propagandistic effect, it took time for the claimed unanimity of its expert endorsement to dissolve. In a 28 April 2012 post we made the following (uncontested) disclosures:

“ArtWatch has been haunted for two decades by a nearly-but-not-made restoration disclosure. In the 1993 Beck/Daley account of the Nippon TV sponsored Sistine Chapel restoration (Art Restoration: The Culture, the Business and the Scandal), we reported that in the late 1980s Leonetto Tintori, the restorer of Masaccio’s Holy Trinity in the Santa Maria Novella, Florence [Fig. 3, above] and a member of the international committee that investigated the controversial cleaning, had urged the Sistine team privately to preserve what he termed ‘Michelangelo’s auxiliary techniques’ which in his view included oil painting as well as glue-based secco. What we had not been able to say was that Tintori (who died in 2000, aged 92) had prepared a dissenting minority report expressly opposing the radical and experimental cleaning method.

“Shortly before the press conference called to announce the committee’s findings, Tintori was persuaded by a (now-deceased) member [Fabrizio Mancinelli] of the Vatican not to go public with his views. He was assured that his judgement had been accepted and that what remained on the Sistine Chapel ceiling of Michelangelo’s finishing auxiliary secco painting would be protected during the cleaning. With a catastrophically embarrassing professional schism averted, the restoration continued and the rest of what Tintori judged to be Michelangelo’s own auxiliary and finishing stages of painting was eliminated. Without knowledge of Tintori’s highly expert dissenting professional testimony, the public was assured that despite intense and widespread opposition the cleaning had received unanimous expert endorsement. Critics of the restoration were left prey to disparagement and even vilification.”

Our 1993/2012 claims on the dissent within the international committee had been double-sourced by James Beck and the Florence-based art historian Richard Fremantle in conversations with Tintori (a member of ArtWatch). They became triple-sourced and document-backed on 8 June 2011 when the Titian expert and former director of the Warburg Institute, Professor Charles Hope, gave the following account when delivering the third James Beck Memorial Lecture (“The National Gallery Cleaning Controversy”) at the Society of Antiquaries, London:

“It would be unrealistic to suppose that those directly involved in the restoration would willingly concede that large areas of Michelangelo’s own work were removed. But even those who believe that the restorers did a good job ought to recognise that much of the controversy could have been avoided if a more careful assessment of the art-historical evidence had been carried out before the restoration began. But no serious investigation was made of the records of earlier restorations, the issues raised by Wilson were not addressed, and Vasari’s testimony was accepted as conclusive evidence that Michelangelo only used buon fresco, without any recognition of its problematic character (which was well understood in the nineteenth century) and without any discussion of the evidence of Armenini. In this context, one might also mention an article in the 1995 Revue de l’art by Leonetto Tintori, the most experienced restorer of Tuscan frescoes of his generation, who died in 2000 at the age of 92. Tintori was consulted about the desirability of restoring the ceiling, and I understand that he opposed it. The most important point in his article is that the technique supposedly used by Michelangelo on the ceiling, buon fresco alone, with only very small additions in secco, was entirely inconsistent with the practice of other painters in Tuscany, from Buffalmacco to Lippi and Sarto; and the same point was made by Eve Borsook [art historian and author of the 1960 and 1980 The Mural Painters of Italy] in the same journal. Tintori ended his article by deploring the modern practice of ever deeper cleaning, concluding, ‘This new orientation aimed at the total restitution of the original paint has had the paradoxical effect that the appearance of pure authenticity has become increasingly rare.’ Given his membership of the [Kress-assembled] committee that recommended, apparently against his own advice, the restoration of the ceiling, he could hardly have attacked the results explicitly, but it cannot be by chance that he chose to say what he did, a year after the publication of the [Vatican’s] final restoration report.

WHO HAD KNOWN OF TINTORI’S DISSENT?

In his 2016 memoir, Colalucci made no mention of Tintori’s opposition or his 1995 Revue de l’art views on the destructiveness of the Sistine Chapel restorations – his sole reference to the opposing restorer came in his above-cited composition of the Kress committee. Presumably, all other members of the working group – Modestini; Brealey; Dwyer [-Modestini]; Rothe and Bull had known of his opposition, as had Mancinelli. Perhaps Marilyn Perry and Colalucci had not known, but, certainly, Robert Hughes, John Russell, and very many other journalists were duped. Brandt gave no hint of Tintori’s opposition in Apollo but she stopped fractionally short of claiming unanimity:

“Everyone agrees with David Bull, Head of Paintings Conservation at Washington’s National Gallery of Art, that ‘the work being done on the frescoes should be meticulously watched, examined and questioned… (Fresco conservators seem not to be disturbed by the cleaning.)”

POPE-HENNESSY’S ATTACK ON BECK

When dubbing Beck the most culpable scholar/critic, Pope-Hennessy detached himself from his professional obligations:

“If you are an art historian, it is essential to free yourself from the fetters of your profession. The Sistine Ceiling is no more the property of art historians than the Ninth Symphony is the property of musicologists.”

The analogy was perversely inapt: in the Sistine Chapel, two recently appointed young officials – an art historian/curator and a quasi-scientific restorer – were rewriting a score they had ignorantly/wilfully misread in defiance of their predecessors’ views and reports and they were demanding that musical history be re-written to sanctify their systematic adulterations.

Pope-Hennessy was not alone in standing on such treacherous ground – he was running with a pack. His denunciation of Beck was made in a review of the 1986 book The Sistine Chapel: The Art, the History, and the Restoration (- published in the UK as The Sistine Chapel: Michelangelo Rediscovered). The book carried accounts from the three principal Vatican agents of the restoration: Professor Carlo Pietrangeli (Director General of the Vatican Museums); Dr Fabrizio Mancinelli (Curator of the Vatican Museums’ Byzantine, Medieval and Modern collections); and Gianluigi Colalucci (the Vatican’s Chief Restorer) – the latter two being the restoration’s co-directors. Their views were implicitly endorsed by accompanying scholarly essays from André Chastel, Pierluigi de Vecchi, Michael Hirst, John O’Malley, and John Shearman. The book was co-published by the Nippon Television Network Corporation which had sponsored the 1980-1994 restoration for $3million in exchange for all film and photography rights throughout each of the restoration’s three stages (the upper wall lunettes; the ceiling; and the Last Judgement altar wall) and for three years afterwards on each part.

INDEFENSIBLE METHODS

Pope-Hennessy appreciated that the restoration breached fundamental protocols by being conducted piecemeal on a narrow, enclosed platform when under intense film-set lighting that denied the restorers any means of appraising the actions and artistic effects of their radical, oven cleaner-like gelled cocktail of soda, ammonia, and detergents. (See Figs. 1 and 4.)

The cleaning paste, AB57, had been formulated to strip all historic organic materials from the plaster surface in two three-minute applications set twenty-four hours apart and removed each time with copious amounts of sponged water. The solvents-contaminated rinse water saturated the fresco plaster so completely that underdrawings on a lower plaster layer became visible. Empty assurances were given that a new air-conditioning system would protect the newly exposed bare plaster surfaces from the Chapel’s notoriously high levels of dirt, humidity, and fluctuating temperatures. Reports later emerged of secret night-time removals of white powder accumulations on the ceiling frescoes. By 2013 the ceiling had been lit to brighter and more colourful effect with powerful LED lights, when the chief defence of the restorers had been their supposed recovery of originally brilliant colours. See “The Twilight of a God: Virtual Reality in the Vatican” where we asked:

“Given this recent history, might Prof. Brandt – or any of the restoration’s supporters at that time – ever have imagined that within a couple of decades the Vatican would conclude that the chromatically brilliant ‘New Michelangelo’ would require artificial lighting ten times more powerful than that installed at the time of the restoration?”

In 2016, Colalucci blamed the chapel’s initially too-powerful levels of artificial lighting for the cleaning controversy itself:

“None of us had realized that after cleaning, these frescoes needed minimal lighting in order to be seen correctly. We should have considered the fact that, having been painted to be seen solely in light from the windows or candles and torches, they would look wrong in very brights lights such as television crews use.”

Despite the claim that the restoration had recovered an original intense chromaticism in Michelangelo’s painting that required low levels of lighting, the apparently natural light entering through the chapel’s windows was subsequently turbo-charged:

“…in the end the entire lighting system was revolutionized and moved outside with quartz lamps behind the window panes in accordance with a project devised by the technical department for a combination of natural and artificial light. Today with the new [LED] technologies, the Vatican Museums have installed a new lighting system with good results.”

THE STILL-UNSOLVED ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION PROBLEM

On 10 January 2013 we reported:

“It is now clear that having first engineered a needless artistic calamity, the Vatican authorities have additionally contrived a situation in which the already adulterated remains of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes are presently in grave physical peril. On January 2nd 2012 Art Daily carried an Agence France-Presse report on the panic that has beset the Vatican authorities over the present and worsening environmental threat to the Chapel’s frescoes:

“The Vatican Museums’ chief warned that dust and polluting agents brought into the Sistine Chapel by thousands of tourists every-day risk one day endangering its priceless artworks. Antonio Paolucci told the newspaper La Repubblica in comments published last Thursday that in order to preserve Michelangelo’s Last Judgment and the other treasures in the Sistine Chapel, new tools to control temperature and humidity must be studied and implemented. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people a day, or over 4 million a year, visit the chapel where popes get elected, to admire its frescoes, floor mosaics and paintings. ‘In this chapel people often invoke the Holy Spirit. But the people who fill this room every day aren’t pure spirits,’ Paolucci told the newspaper. ‘Such a crowd… emanates sweat, breath, carbon dioxide, all sorts of dust,’ he said. ‘This deadly combination is moved around by winds and ends up on the walls, meaning on the artwork.’ Paolucci said better tools were necessary to avoid ‘serious damage’ to the chapel… The Sistine Chapel, featuring works by Michelangelo, Botticelli and Perugino, underwent a massive restoration that ended in the late 1990s. The restoration was controversial because some critics said the refurbishing made the colours brighter than originally intended.”

POPE-HENNESSY’S MANIFEST AMBIVALENCE

Without addressing the invasive actions of AB57 – the use of which had been condemned by restorers, scientists, artists, and art historians – or the abnormal film lighting – Pope-Hennessy did acknowledge some of their artistically disruptive consequences:

“On the other hand, it must be recognised that the effect made by any section of the fresco is contingent on the cleaning not only of that section but of the areas contiguous to it. The figure of God the Father in the Creation of the World could be cleaned faultlessly, but it would appear less dominant if the equation between the figure and the fictive moulding around it were disturbed. This has occurred in the first half of the ceiling…where the upper strip of the [fictive architectural] framing is now too light. If this happened in the second half of the ceiling, there would be protests that the Genesis scenes had been diminished or spoiled. The present width of the scaffolding is the equivalent roughly of one bay of the ceiling, and it is extremely difficult when standing on it to judge the relationship of the part of the ceiling that is within touching distance to the cleaned part beyond. I have repeatedly wondered whether it would not be prudent in the second half of the ceiling to employ a platform of double width, even at the cost of denying a larger area of the fresco to current visitors.” (Emphases added.)

Above, Fig. 4: The Sistine Chapel ceiling showing the restorers and film-makers’ platform approaching the most brilliant, deep-space final stages of Michelangelo’s painting.

“TO RESTORE OR NOT TO RESTORE” – COLALUCCI’S BREACH OF PROTOCOLS

Had Pope-Hennessy’s suggestion been made and accepted (thereby tacitly acknowledging an unsound seven-year long procedure) it would have had no effect. Colalucci had stipulated the pre-set, no variations, two three-minute AB57 applications precisely to prevent his restorers from making individual appraisals for fear of undermining his desired aesthetic homogeneity. As he put it in 2016: “I wanted to have every square centimetre under my control and was reluctant to expose others to the risk of failure or controversy.” We can now be clear that this restoration truly was one man’s folly. On his unwarranted and unfounded insistence that Michelangelo had not painted on the fresco surface, the restoration was reduced to the brutally simplistic and non-artistic goal of executing the most technically expeditious removal of all historic materials from the plaster surface – which, in truth, was to say, primarily, the last stages of Michelangelo’s own work. For this reason, even if the restorers had been able to compare the already cleaned fresco sections with the one being cleaned, they had no authority to depart from Colalucci’s twin, three-minutes AB57 applications procedure. Later, in self-exculpation at a Kress-organised conference in New York, Colalucci claimed that the heat and the brilliant film-set lighting had “fatigued the eyes” and made aesthetic appraisals impossible – when the decision to clean with AB57 had been taken before the deal with the Japanese film-makers had been struck.

On his own admission, Colalucci had sanctioned a procedure that breached the most fundamental restoration protocol of all – and one that had recently been stated by Professors Paolo and Laura Mora, the inventors of AB57 – that, at all times, the restorer and not the cleaning agent itself must assume responsibility for all the resulting changes of appearance in the work of art. The absence of declared support for the Sistine restorations by the Moras themselves is conspicuous. My (Leonardist) colleague, Jacques Franck, recalls – and may still possess – a 1980s Italian newspaper report in which it was claimed that the Moras had resigned from a Vatican committee because they had judged AB57 (which had been developed to remove traffic pollution from Rome’s marble buildings) unsuitable for Michelangelo’s frescoes. Had they been invited to serve on the Kress-assembled committee, along with Tintori – and if not, why not? Or on the Vatican’s own committee? Our researches had found a single enigmatic comment on the subject. In the Summer 1987 Art News (“Michelangelo Rediscovered”), M. Kirby Talley, Jr. wrote: “The decision to restore the Sistine frescoes was not taken lightly. ‘To restore, or not to restore, that’s the question you have to ask yourself every time you are confronted with a problem.’ cautioned Professor Laura Mora, restorer at the Istituto Centrale del Restauro and a leading authority on fresco conservation.” Talley continued: “This question was posed by the Vatican authorities, and the pros and cons were scrupulously weighed before the final go ahead was given”. No doubt they were, but the fact remains that contrary to the Kress-driven propaganda coup that may have turned Pope-Hennessy, three – and arguably, the top three – leading fresco authorities had not been on the scales. Brandt brought no clarification on the matter in Apollo with her gnomic observation “Fresco conservators seem not to be disturbed by the cleaning”.

SACRIFICING MICHELANGELO’S “COMMUNICATIVE POWER”

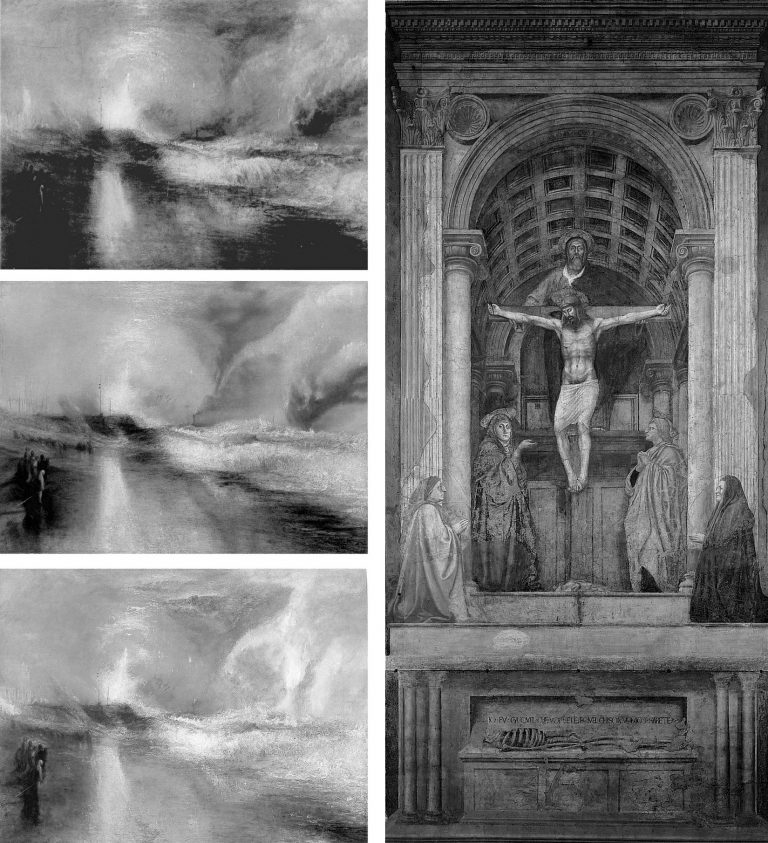

Above, Fig. 5, top: two engraved copies of the Libyan Sibyl, both of which showed the Sibyl’s left arm relieved by a tonally dark background; above, a detail of Michelangelo’s Libyan Sibyl before (left) and after (right) Colalucci’s cleaning and showing the profound and systematic losses of Michelangelo’s secco-extended tonal range of shading and aerial placements. As well as making broad-brush tonal adjustments, Michelangelo had – as Charles Heath Wilson had testified in the late nineteenth century (when very closely examining the ceiling from a special scaffolding) – also drawn secco revisions to contours and to many details such as hair and eyes. In the above photo-comparison, it can be seen that many lines which had clarified and reinforced details like the Sibyl’s thumb, lower jaw, the hair band, and the edges of the giant book, had all perished in Colalucci’s soda/ammonia/detergent double-washing. Further, Wilson had supplied an incontrovertible material/scientific proof that the secco painting was Michelangelo’s own: the secco painting had cracked as the plaster had cracked. The ceiling had begun cracking in Michelangelo’s own lifetime. Had the painting been applied centuries later by subsequent restorers, as the Vatican claimed on no evidence, it would have run into the cracks. It had not run into the cracks – but the world heard nothing of this: Wilson’s crucial, utterly subverting testimony on the secco painting had been air-brushed out by all players at the Vatican and, wittingly or unwittingly, by all of their art historical supporter/apologists.

For his part, Pope-Hennessy harboured and instanced futher (well-founded) aesthetic and historical anxieties:

“…you come in, as you have always done, through the little door under the Last Judgement and look up, speechless at the rebellious Jonah, the melancholy Jeremiah, and the Libyan Sibyl heroically supporting her colossal book [Fig. 5, above]. But about halfway down the chapel is a scaffolding resting on rails along the walls, covered with mustard-coloured fabric on which appear the shadows of ordinary mortals busily at work. [Fig. 4, above.] Beyond it you look towards the Zechariah, the Joel, and the Delphic Sibyl, suffused with light and seemingly the work of another, more lively, more decorative artist…Inevitably, judgement contains a strong subjective element, the more so as two kinds of verdict are involved, short-term judgement dominated by pleasure at the unwonted freshness of paint surface and long-term judgement in which one asks oneself whether the image has the same communicative power that it possessed before… Each time I go back to the chapel and sit, as I have so often sat, before the pitted surface of the Jeremiah, I feel concern that future generations may be denied an experience that raised the minds and formed the standards of so many earlier visitors. This is the basis of the claim of Beck and many others that the cleaning should be suspended at this point.” (Emphases added.)

Against all of which, he baldly insisted: “If there were the least reason to believe that the late frescoes would be overcleaned, this would be a valid view. But there is no evidence of overcleaning in the restored section of the chapel and there is no reason to suppose that the later frescoes will be treated less judiciously.”

THE WILFULLY DISREGARDED HISTORICAL VISUAL RECORD

On Pope-Hennesy’s own – albeit limited – admissions, there was every reason not to take the Vatican restorers’ methods on trust, not the least of these being the fact that, as any visually alert scholar should have appreciated, the many copies of the Ceiling made from Michelangelo’s day to our own, had all testified to his secco overpainting:

Above, Fig. 6: Top, left, the ink and wash copy of Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling figure Jonah, made between 1524 and 1534 by Giulio Clovio; top, right, a c. 1800 etched copy of Michelangelo’s Jonah by the Irish painter James Barry, R. A.; above, left, a detail of Michelangelo’s Jonah before Colalucci’s cleaning and showing the then surviving secco remains of the Clovio-copied dramatic shadow cast from the Prophet’s left foot; above, right, Jonah’s left foot after Colalucci’s elimination of the secco-enhanced shadows.

Disregarding all such historical visual testimony, the Vatican insisted that what had been understood since the 1512 unveiling to be Michelangelo’s own shadows, were arbitrary accumulations of soot trapped in “glue-varnishes” applied centuries later by successive restorers with sponges tied to thirty-feet long poles – poles of which, we established, no record existed and which, had they existed, would have stopped thirty-feet short of the ceiling. The phantom poles were summoned by Vatican officials in the absence – which we also established – of Vatican records of ceiling-high restoration scaffolding.

THE BOOK THAT WOULD HAVE BLOCKED THE SISTINE CHAPEL RESTORATION:

Above, Fig. 7: Left, the compendious 1990 book of historic copies of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes; centre, the book’s reproduction of Giulio Clovio’s Jonah drawing; right, the book’s reproduction of 19th century engravings (after lost copies) of the two lunettes Michelangelo had painted on the Chapel’s altar wall and would later destroy when preparing that wall for his Last Judgement.

Had the above book been published before 1980 and due consideration been given to Wilson’s account, a cleaning of the ceiling would have been stopped dead by the testimony of the above two images. The Clovio drawing alone constituted a proof positive that Michelangelo’s instantly-acclaimed lights and shadows had not only been present on the Ceiling but were also present on Michelangelo’s upper wall lunette frescoes – just as Colalucci’s Vatican restorer predecessors had reported. It did so because the two lunettes part-shown in its lower corners, were the very ones that Michelangelo destroyed to paint his Last Judgement. Thus, the sharply pronounced shadow that had been cast along the ground by Jonah’s left foot had been painted before any restorer had been near the frescoes. It could not, therefore, have been a freakishly artistic by-product of soot trapped within successive “glue varnishes” applied by restorers. Moreover, the glimpses of the shadows cast by Michelangelo’s lunette figures in Clovio were in turn confirmed by the etched copies of the two destroyed lunettes on the altar wall. Even the Clovio-recorded nude boy supporting Jonah’s name tablet had originally cast his own shadow on the wall before Michelangelo painted his Last Judgement.

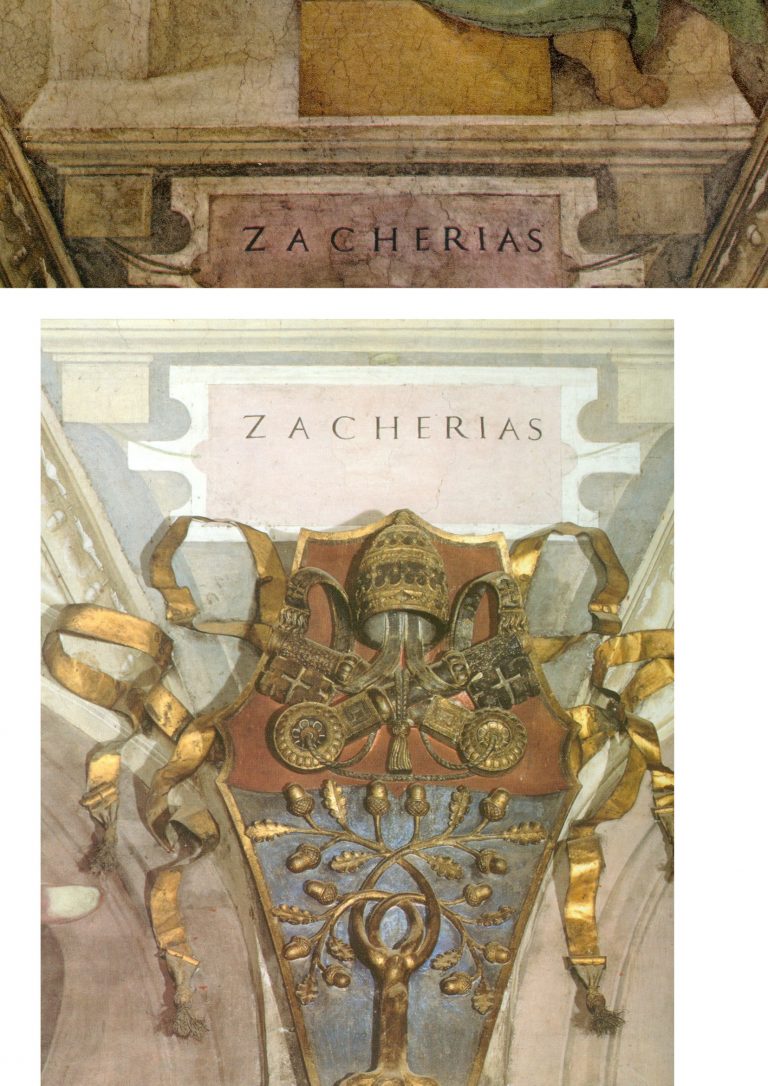

Above, Fig. 8: The name tablet for the Prophet Zacherias – top, before cleaning: above, after cleaning.

THE ELEPHANT ON THE CEILING

Michelangelo had not been the first artist to depict cast shadows. What stunned his contemporaries had been the thunderous force of spatial illusionism within which his figures had realised an unprecedentedly vivid sculptural presence-in-space. It was precisely in the wake of the illusionistic shading’s evisceration that Pope-Hennessy had (correctly) noted that where the name tablets had previously been “firmly integrated in the [real and fictive] architecture of the chapel…they [now] read like supertitles in an opera house” – see Fig. 8, above. To repeat: that tragically late-published book had shown beyond any dispute that there had been no break in the visual record of Michelangelo’s shadows from his day to ours – and, therefore, that the Vatican’s restorers had destroyed the finishing stages of Michelangelo’s own painting throughout the ceiling. In retrospect – and after all the account/demonstrations we have published (see, for example, Cutting Michelangelo Down to Size) – it might increasingly seem that this visually self-evident truth was a truth too big and too inconvenient in its implications ever to be ceded by the Vatican and the compliantly supportive art historical establishment it had garnered.

UNDERSTANDING POPE-HENNESSY’S SCHOLARLY BLANK CHEQUE

As a former director of both the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum; a professor of art history at New York University’s post-graduate Institute of Fine Arts; and the very recently retired Chairman of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Pope-Hennessy’s essay had effortless clout despite his self-subverting acknowledgements of both disturbing artistic results and – even – a wide distrust of the restoration among professionally sound peers. He opted to berate the critics while lauding the restorers, not on what they had done (on some of which he was critical) but on what he expected them to do next. Perhaps he had been privy to Mancinelli’s assurance to Tintori? He had certainly registered concern over of a group of cleaned Prophets and Sibyls:

“Optically, seen from the altar end of the chapel, they look a little smaller and less weighty than they did before. In the heads, a gain in definition is accompanied by a loss of ambiguity.”

Given that the visual arts work on and through their optical reception, how could Pope-Hennessy discount his own art historically informed, optically received, reading of diminished volumes and weights in Michelangelo’s figures? Perhaps he, like the art critics Hughes and Russell, had been swayed (or cowed) by the sheer authority of the supposedly unanimous Kress Foundation report? In any event, he wrote:

“…a gulf opened between those who adhered to the old concept of the ceiling and those who embraced the ceiling as it seemed originally to have been. The dispute was taken up in the American press, in largely polemical terms. There were demonstrations; and vociferous protests were made by both academic and non-figurative artists. The Vatican authorities went so far as to explain publicly, in two days of conferences in New York, the restoration program and the data on which it was based. Not unnaturally American criticism was reported throughout Italy, and had a disturbing, though not demoralizing, effect on the restorers involved. Arrangements, however, were made for a number of restorers of acknowledged excellence (three of them specialists in fresco decoration) to visit Rome, and they one and all endorsed the wisdom of what was being done.” (Emphases added.)

LEARNING TO LOOK

Aside from this explicit professional deference to a Higher Technical Authority in matters of aesthetic appraisal, other possible explanations for Pope-Hennessy’s stance emerged in his 1991 memoir, Learning to Look. This most distinguished scholar had a visual Achilles Heel – of time spent in an art school, he recalled “I disliked this too, and to this day I cannot draw.” Moreover, he had developed aversions to fellow art historians – and even (like Colalucci) to subjective judgements:

“One of the things about art history that I found puzzling from the first was that clever art historians (there were stupid ones too, of course, but a lot of them were really clever) should reach diametrically opposite conclusions on the basis of a tiny nucleus of evidence. The reason, so far as one could judge, was that the subjective element in art history was disproportionately large. If this were so, it was not only works of art that needed to be looked at in the original but art historians too, since their results were a projection of their personalities. So for some years, I made meeting art historians a secondary avocation.”

From the first, Pope-Hennessy had indeed made it his business to meet as many art historians as possible. When he left Balliol College, Oxford, with a second-class degree in history and an alumnus’s legendary “tranquil consciousness of an effortless superiority” (- in his case, specifically: “in the form of a self-confidence that sometimes verged on arrogance and a clear understanding of the difference between success and a succès d’estime”) he sold some inherited coconut islands off Borneo as income to be devoted “to travelling and to the preparation of a book” – and all this when, like Max Beerbohm’s Young Arnold Bennet, already having “a life plan in my mind.” During the Second World War he “found himself” in the Intelligence Department of the Air Ministry and there, for the first time, “met ordinary people” whom he considered “congenial and interesting”. In later life he expressed a preference for works of art over people of any kind:

“Objects mean more to me than people. It is not that I am frigid or reclusive, but that object-based relationships are more constant than human ones (they never change their nature and they do not pall).”

THE CHURNING “RAW MATERIAL” OF SCHOLARSHIP – AND A NEW SPECTATOR SPORT?

However, and despite his avowed attraction to the constancy of objects, as a self-made art historian, Pope-Hennessy came to welcome their radical alteration by restorers:

“People sometimes complain that there is nothing new to be said about Italian painting. They mean by this there are now monographs on many minor painters and that the works of great artists have been discussed in a large number of books. But the truth is that the raw material of Italian painting is in a constant state of flux. When paintings change through cleaning, our view of the artist who produced them changes as well.”

Above, Fig. 9: Top, the National Galley’s Piero della Francesca The Nativity before its latest restoration (left), and afterwards (right); above, a comparative detail showing the recently repainted shepherds and wall, with (inset) their previous state.

Like many of their scholarly peers, newspaper art critics have come to welcome the easy copy-generating potential of restorers’ alterations. In December 2022, Waldemar Januszczak of the Sunday Times, extolled the National Gallery’s controversially reconstructed Piero della Francesca Nativity (Fig. 9, above) and claimed that museums themselves now welcome “the inevitable brouhaha that follows any big restoration” because it “provokes interest and gets people through the door.” However, the art historian Giorgio Bonsanti deplored the intervention in IL GIORNALE DELL’ARTE and fears that such “controversies are destined not to subside but to remain and grow in future years, because the problem exists, and will remain evident to the millions of visitors to the National Gallery”. Scarcely less alarming to the Gallery must have been the Guardian critic, Jonathan Jones’, (earlier) assault on the repainted Nativity.

Jones had been the newspaper art critic of choice who was embedded within the Gallery’s conservation department during the restoration of its version of the Leonardo Virgin of the Rocks. The Evening Standard art critic, Brian Sewell, a student of Anthony Blunt at the Courtauld Institute, and a long-time scourge of National Gallery restorations, had been similarly co-opted within the restoration of Holbein’s The Ambassadors (Fig. 10, below). When so embedded, Jones predicted (wrongly) that “ArtWatch will attack the restoration”. On the Nativity, Januszczak similarly predicted: “There will be those, of course, who will howl at the changes – there always are.” In this case, at least three have now done so on the record – in addition to Jones and Bonsanti, in the March/April 2023 issue of the Jackdaw, its editor, David Lee (“Abbronzatura Solaire”), complained that aside from imposing complexions on the shepherds that are “more appropriate to Love Island than Bethlehem”, the Gallery has confounded a manifestly un-finished painting with a damaged finished painting.

Having previously studied the Nativity’s historic and restoration dossiers, we would add that this panel painting has likely suffered more accumulated restoration blunders than any other in the collection – with the possible exception, perhaps, of Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna of the Meadow. Both of those two pictures received disastrous “structural surgery” from a restorer (Richard D. Buck) who had been hired and brought over from America in 1948 by the National Gallery’s Director, Sir Philip Hendy, to introduce supposedly advanced conservation methods. Januszczak, who defends the Nativity’s recent repainting make-over on the grounds that “an active artwork that is doing what it is supposed to be doing must always trump a charming ruin”, begs the crucial question – “What is an historic picture supposed to do?” – and he clearly fails to appreciate that it is not Time and Neglect but, rather, restorers who, through their ceaseless Un-doing and Re-doing of pictures, create ruins. Where no auction house or dealer would dream of boasting that a picture on offer has had multiple restorations, museum pictures are treated today like so many bags on an airport carousel waiting to be picked up and done over on the whims and fancies of the next available restorer.

(Incidentally, Jones, Bonsanti, and Lee have by no means exhausted the many due criticisms of the Nativity’s latest restoration makeover. The ruined stone wall behind the repainted Shepherds, for example, has itself been repainted in a manner that robbed it of thickness and perspectival placement and left it running flatly across the picture plane, like so much stone-patterned wallpaper, to serve as a backdrop foil to the hypothetically reconstructed heads, as seen at Fig. 9.)

PROCLAIMED RESTORATION TRANSFORMATIONS – AND THINGS THAT CRITICS OVERLOOK

Where Pope-Hennessy had likened the Sistine Ceiling to Beethoven’s Ninth and noted that “another, more lively, more decorative artist” was emerging, Januszczak whooped at the spectacle of the transformation:

“The thin and neat scaffolding bridge moved elegantly along the ceiling like a very slow windscreen wiper. In front of it lay the old Michelangelo, the great tragedian, all basso profundo and crescendo. Behind it the colourful new one, a lighter touch, a more inventive mind, a higher pitch, alto and diminuendo. It was being able to see both of them at once – Beethoven turning into Mozart before your eyes – that made this restoration such a memorable piece of theatre.”

Unlike Januszczak, Pope-Hennessy had not always welcomed restoration-induced changes. In his 1970 book, Raphael, he observed: “But Raphael restored is Raphael interpreted; it is different from the real thing” – and in 1987 he would likely have known that a recent “Raphael restored” at the Vatican had proved disastrously different from the real thing. In 1982, Mancinelli had said of a bungled, chemically experimental restoration that required extensive repainting by Colalucci in Raphael’s Loggia, “It is the best demonstration that a restoration can also not go along well.” In 2016, Colalucci recalled that the Vatican had faced “a serious problem” when “a new inorganic substance that had not been sufficiently tried and tested” was used.

In 1991, as the Sistine Chapel restorations neared completion, Pope Hennessy reverted to his younger self’s restoration-critical stance and noted:

“In London since 1945 the National Gallery had been the target of ceaseless criticism. There had been intermittent controversies in the press over the cleaning of paintings, but successive directors had enjoyed the support of a passive, compliant board. The policy of Radical Cleaning had been espoused by Philip Hendy (who must have suffered from some retinal defect which made him see pictures as flat areas of colour) and had continued under his successors for so long that proof of the damage done to the collection over thirty years could be seen in almost every room.”

That judgement on National Gallery cleanings was sound and it constituted an international commonplace. Mario Modestini wept for half an hour at the sight the Gallery’s “flayed” restorations; in 1970 Pietro Annigoni painted “MURDERERS” on the National Gallery’s doors in protest; in March 1999 when I visited the Gallery with Professor Anatoly Alyoshin, head of the Repin Institute, St. Petersburg (Russia’s leading institute for the training of picture restorers), he was shocked by the paintings’ uniform brightness and seeming newness. Stopping between galleries, he swept his arm around and said “See! Everything in every school looks as if it was painted in the same studio at the same time.” In a sense, everything had been – after stripping paintings of all they judge extraneous, National Gallery restorers are permitted to this day to paint onto them whatever they take to have been an artist’s original intentions, even with pictures as old and venerated as Holbein’s The Ambassadors and Piero’s Nativity. Old masters are being treated like neglected scores awaiting the life-restoring interpretation of a would-be pictorial Furtwängler, von Karajan or Barenboim – but with the difference that where musical scores outlive their successive interpreters, a painting is its own score.

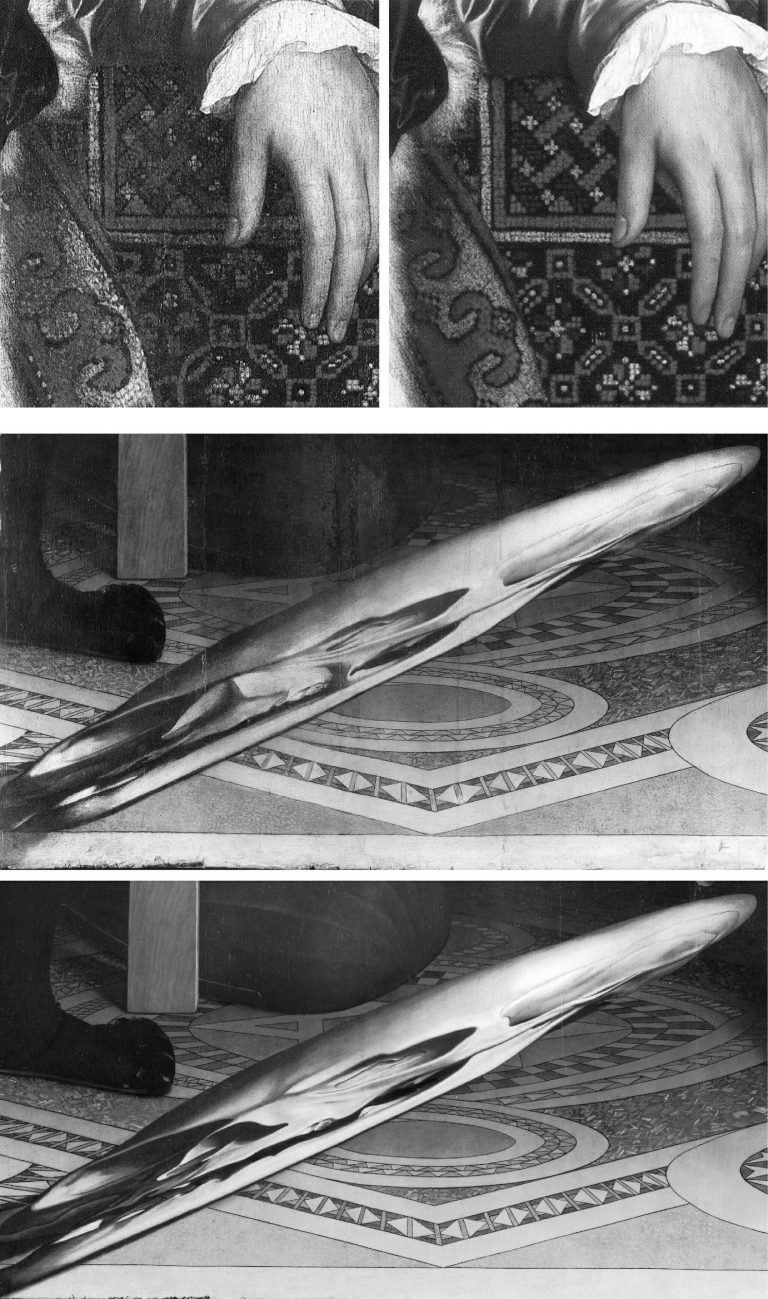

PURISM AND FAKISM: FALSE AGE CRACKS AND RE-INTERPRETATIONS ON RESTORED PAINTINGS

In the 1990s the National Gallery’s then head of restoration, Martin Wyld, contended: “The ‘Good Restorer’ is the one who ‘does the minimum necessary but not too little… we remove everything not put on by the artist and then use our judgement to get back to the original.” On 8 April 2023, the Financial Times (“Behind the seams at the museum”) reported that the present head of restoration, Larry Keith, said of his restoration of Parmigianino’s Saint Jerome’s vision of John the Baptist revealing the Virgin and Jesus, “We are editing, in a way. The work is informed by science and objective criteria, but there are decisions you take, which on some level are interpretive”. In an Esso-sponsored, BBC-filmed restoration of the Ambassadors (which has ceased to be available), Wyld was seen to have repainted much of the carpet to a new design on the authority of a “carpet expert”, and to have repainted much of Holbein’s famous anamorphic skull to a new and elongated design derived from a computer-distorted photograph of another skull. The Gallery’s defence of Wyld’s first-ever insertion of a Virtual Reality image into an old master painting was its claim that “modern imaging techniques” offered more “scope for exploring possible reconstructions” than the perspectival and optical conventions by which the skull had been produced. The pronounced differences between the Ambassadors’s old original paint and Wyld’s newly redesigned and presumptuously repainted parts of the skull, were concealed by his painting fake lines of cracking onto his own newly painted hypothetical reconstructions to match the real cracks on the real old paint.

Above, Fig. 10: Top, a detail of Holbein’s The Ambassadors, showing a section of redesigned and repainted carpet, before treatment (left) and after treatment (right); centre, the pre-restoration anamorphic skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors; above, the Wyld-extended, computer-generated skull in the Ambassadors.

PRODUCING “DIFFERENT, MORE POWERFUL” IMAGES

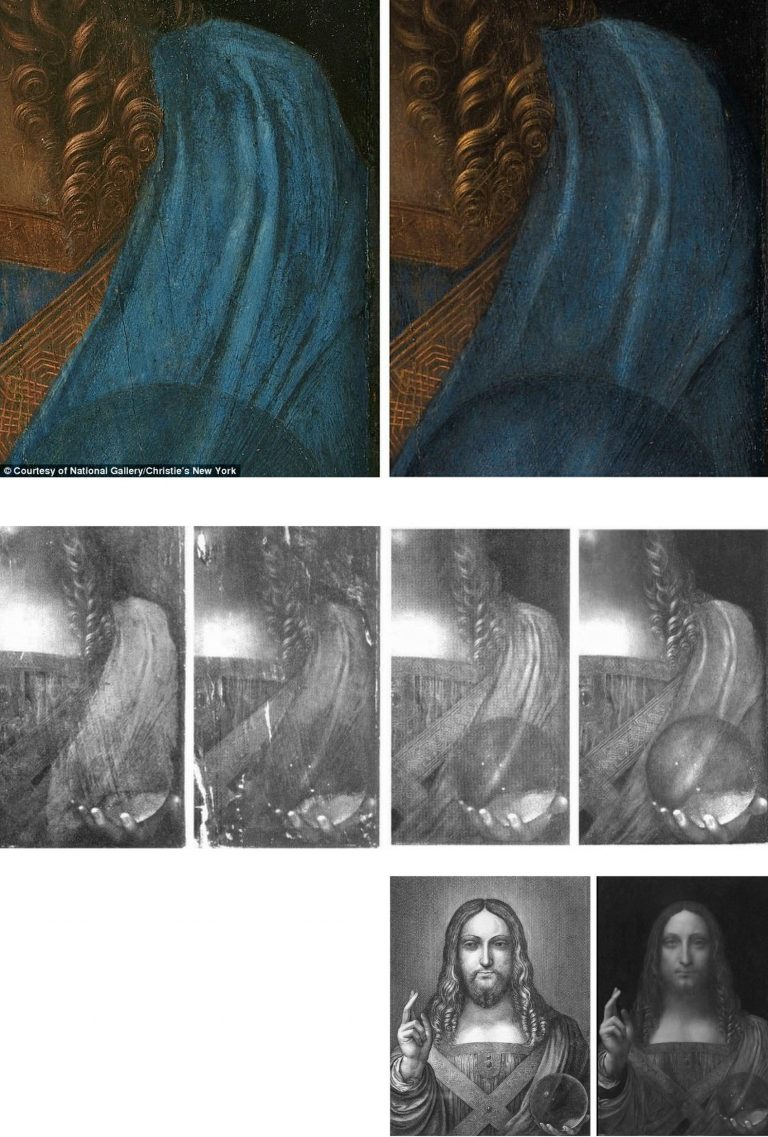

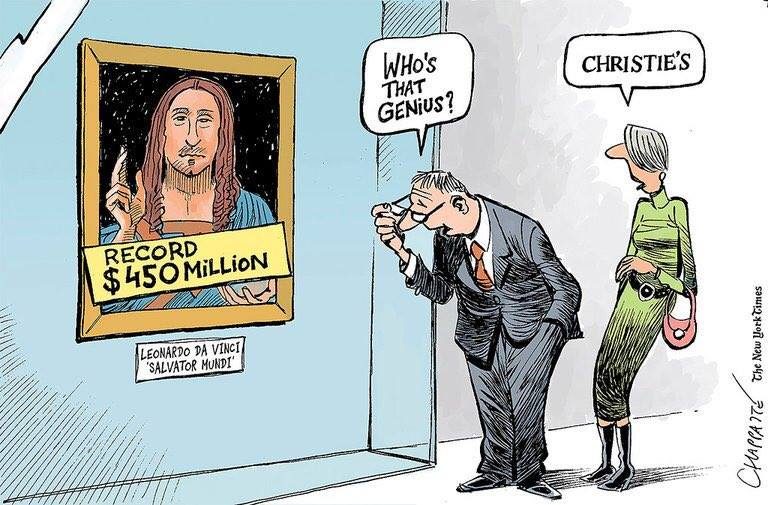

The New York restorer and Kress-appointed Sistine Chapel invigilator, Dianne Dwyer Modestini (formerly Clinical Professor, Kress Program in Paintings Conservation at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts) – very extensively repainted and artificially distressed the much-damaged Leonardo School Salvator Mundi that fetched a world record $450 million in 2017 at Christie’s, New York – prompting Thomas Campbell, a former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to ask: “450 million dollars?! Hope the buyer understands conservation issues – #readthesmallprint”. Dwyer Modestini had published this small-print report of an early intervention in her decade long undoing and redoing of the picture:

“The initial cleaning was promising especially where the verdigris had preserved the original layers. Unfortunately, in the upper parts of the background, the paint had been scraped down to the ground and in some cases to the wood itself. Whether or not I would have begun had I known, is a moot point. Since the putty and overpaint were quite thick I had no choice but to remove them completely. I repainted the large missing areas in the upper part of the painting with ivory black and a little cadmium red light, followed by a glaze of rich warm brown, then more black and vermilion. Between stages I distressed and then retouched the new paint to make it look antique. The new colour freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair, and made a different, altogether more powerful image. At close range and under a strong light the new background is obvious, but at only a slight remove, it closely mimics the original [paint work] … Most of the retouching was done with dry pigments bound with PVA AYAB. Translucent watercolours, mainly ivory black and raw siena, were used for final glazes and to draw [false age-] cracks…” (Emphasis added.)

Above, Fig. 11: Top, a section of drapery on the $450million Leonardo school Salvator Mundi, as seen in 2011-12 at the National Gallery (left), and (right) as when sold in October 2017 at Christie’s, New York; centre row, showing left, and second left, the picture detail, as when acquired in 2005 and taken to Modestini for restoration; third left, the Modestini-restored picture detail when shown as an autograph Leonardo in 2011-12 at the National Gallery; and, right, the Modestini re-modified feature, as sold in 2017 as an autograph Leonardo, at Christie’s, New York; bottom row, left, the Wenceslaus Hollar engraving that was said by the National Gallery to have been copied from the National Gallery-exhibited Salvator Mundi picture (bottom right) when in the collection of Charles I. That claim was subsequently disproved when the lost Charles I Salvator Mundi emerged in Moscow and was seen to be of an entirely different composition – at which point, the previous resemblance of the painting’s complex shoulder drapery folds to those in the Hollar etching had become more of a disqualification than a potential corroboration.

CHRISTIE’S RESPONSE

In December 2017, Christie’s was presented with photographic evidence (Fig. 11, above, top) assembled by Dr Martin Pracher, a lecturer in technical art history, that showed the changed states of the Salvator Mundi’s (true left) shoulder drapery between 2012, when exhibited at the National Gallery as an autograph Leonardo prototype painting, and 2017, immediately before the $450million October 2017 sale at Christie’s, New York, in which the picture was offered as a then different but supposedly still-autograph Leonardo prototype that enjoyed “an unusually strong consensus” of scholarly support. Under Press questioning (see Dalya Alberge in the Daily Mail) a Christie’s spokeswoman said Modestini had “partially cleaned the passage of paint in the shoulder and the dark streaks disappeared… To imply something incorrect has taken place would itself be incorrect”. Thus, it was insisted that the recently “disappeared” multiple folds, were not folds but mere “dark streaks” that had appeared during Modestini’s 2005-2010 restorations only to disappear under her 2017 ministrations.

INSTITUTIONALLY SEALED LIPS

Of whatever it consisted, Modestini’s last-minute intervention had been made under sworn secrecy at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts conservation studios, as she disclosed in her 2018 memoir, Masterpieces: Based on a manuscript by Mario Modestini. That is, when the Salvator Mundi returned to New York in July 2017 ahead of Christie’s November sale, Modestini, was instructed “not to inform anyone” when the painting was “delivered to the Conservation Center under guard and in great secrecy”. Modestini further disclosed that a deal brokered by Christie’s ahead of the sale whereby the vendor would receive at least $100million had also been “successfully kept under wraps.”

THE NATIONAL GALLERY’S ABIDING INFLUENCE ON RESTORATION “REVELATIONS”

When Pope-Hennessy deviated in 1987 from his earlier soundness on transformative restorations, he bought into the National Gallery’s longstanding picture cleaning rationale by endorsing two of the 20th century’s most spectacularly controversial restorations:

“In its cleaned form the [Sistine] ceiling has become again what Michelangelo’s contemporaries considered it, one of the supreme achievements of mankind. With Titian, the revelation started in the National Gallery in London, when the Bacchus and Ariadne was freed of centuries of dirt and proved to be painted in an altogether different tonality from any that had previously been supposed.”

That there had been no “centuries of dirt” to remove from the Titian will be shown in Part III. A fuller understanding of Pope-Hennessy’s late-life restorations lapse and an appreciation of the methodological and promotional similarities between the two most controversially transformative restorations in the second half of the twentieth century will be tracked through the records of the two successive National Gallery directors from 1934 to 1967, Sir Kenneth [later Lord] Clark, and Sir Philip Hendy. By the 1980s, that pair’s polished formulations had come to serve as an internationally infectious template for the unbridled techno-experimentalism seen in the Brancacci and Sistine chapels during what, for Colalucci, had constituted the terminus of “the golden age of restoration in Italy, the halcyon era from the late 1940s to the mid-1990s.”

In Part III, we correlate the false scholarship that flowed from the Titian Bacchus and Ariadne and Michelangelo Sistine Chapel restorations, along with the artfully engineered professional endorsements both restorations received from the then highest authorities.

Michael Daley, Director; 15 April 2023

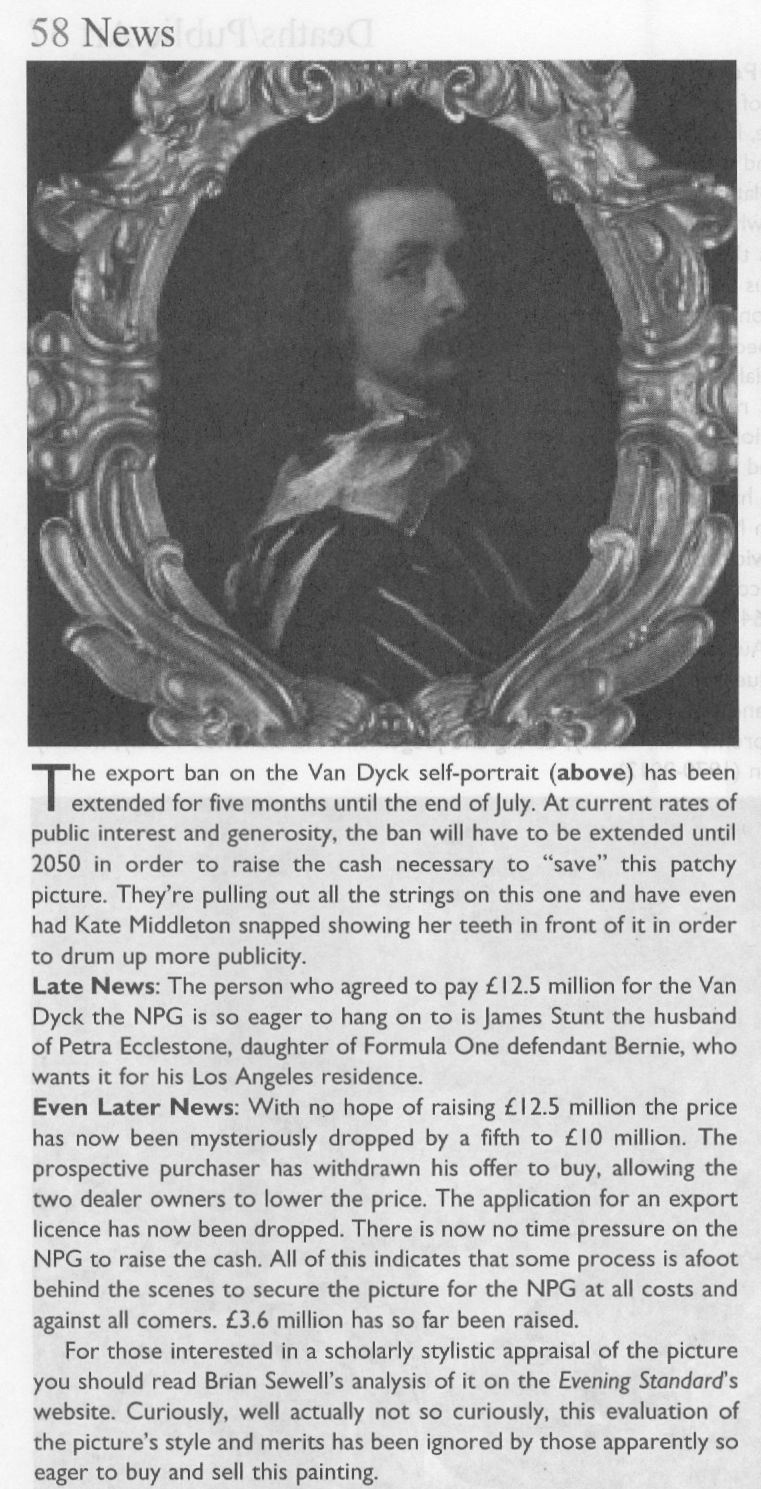

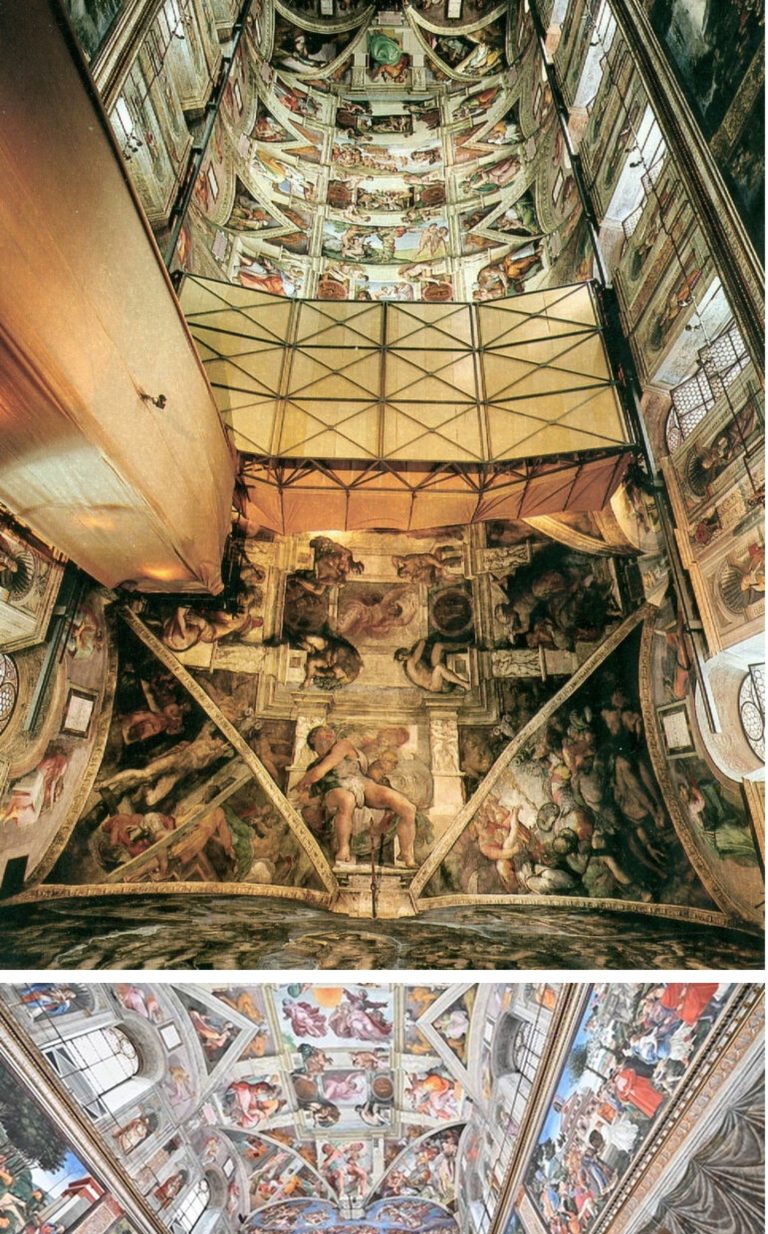

Art-Trading, Connoisseurship and the Van Dyck Bonanza

There are now two upgraded paintings in two museums that have been claimed as “The Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait” and an upgraded third painting has been presented in a third museum as a lost, earlier Van Dyck self-portrait – see Fig. 1 below. This acceptance by three museums of three self-portraits in six years has coincided with a spate of exposed forgeries and restoration-led upgraded “discoveries”. The opaque means by which three problematic pictures found their separate ways into three museums as upgraded autograph Van Dycks are items of cultural/art-political concern.

This triple elevation has spotlighted levels of scholarship and transparency within the cross-linked spheres of connoisseurship, ownership, restoration, promotion and sales in the wake of the spectacular rise and demise of the now downgraded and disappeared $450m Leonardo School Salvator Mundi that had been bought for barely a thousand dollars and somehow netted nearly two thirds of a billion dollars through three sales in five years on an implausible provenance. The institutionally sensitive roles of upgraded old master paintings serving as conduits for financial exchanges and investment are attracting attention as never before. The Van Dyck bonanza has prompted public challenges on both the artistic status of the pictures being traded and the means and manner by which public and private monies pass hands.

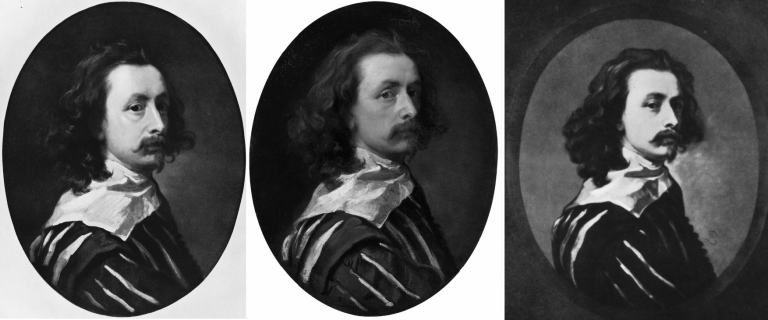

THREE UPGRADED VAN DYCK SELF-PORTRAITS

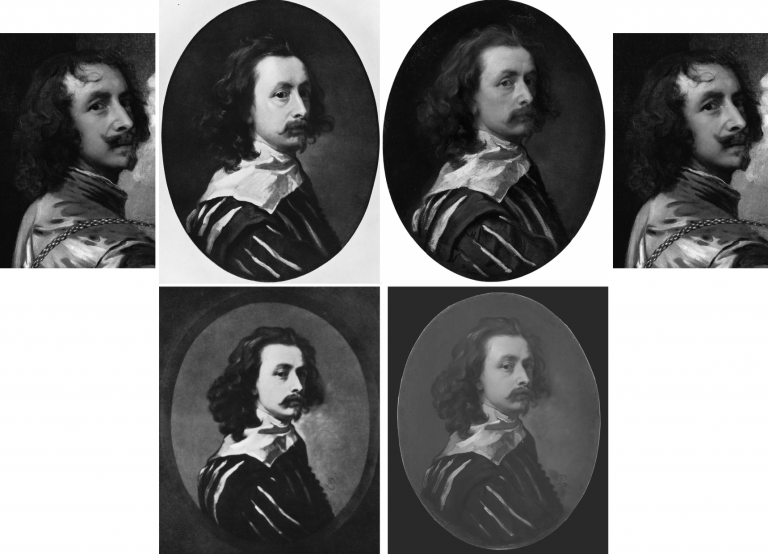

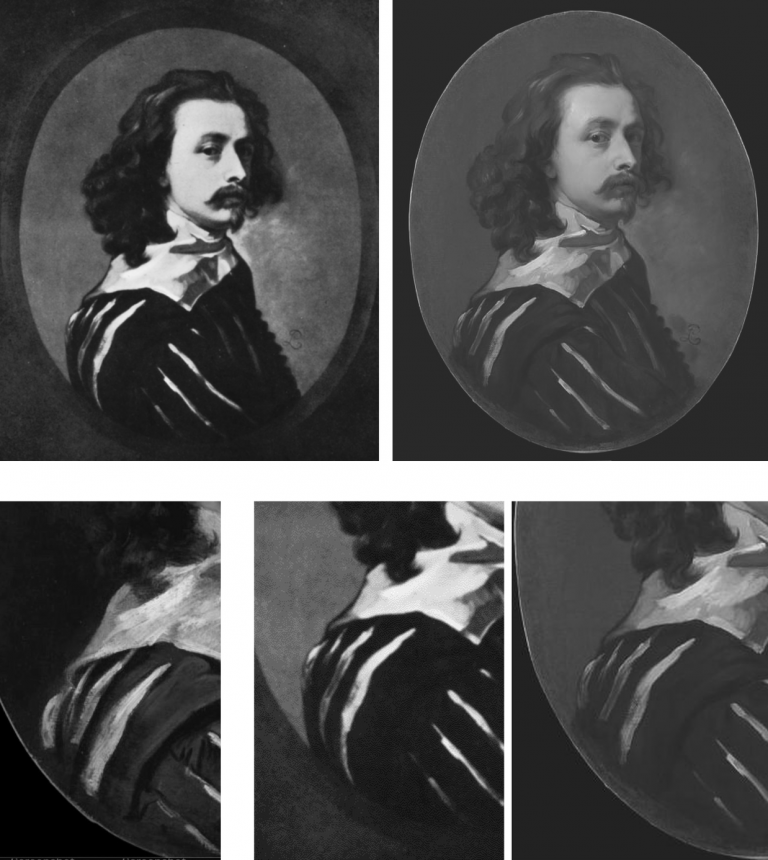

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the National Portrait Gallery’s “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait”; centre, the new Bendor Grosvenor-accredited (and owned) “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait”, as loaned to the Rubenshuis Museum, Antwerp; right, the Philip Mould/Grosvenor accredited, privately owned painting that has been loaned as an autograph Van Dyck self-portrait to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minnesota.

All three of the above self-portraits changed hands recently as autograph Van Dyck self-portraits with the first two both now claimed to be the last Van Dyck self-portrait. All three have undergone modern or recent restorations. The two on the right were transformed within the last decade (and possibly by the same restorer). The picture on the left – an undeclared, covert upgrade – was bought by the National Portrait Gallery in 2014 for £10m.

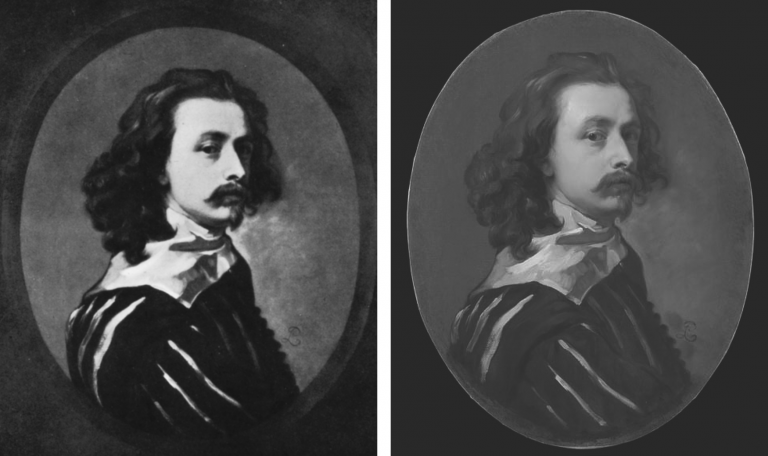

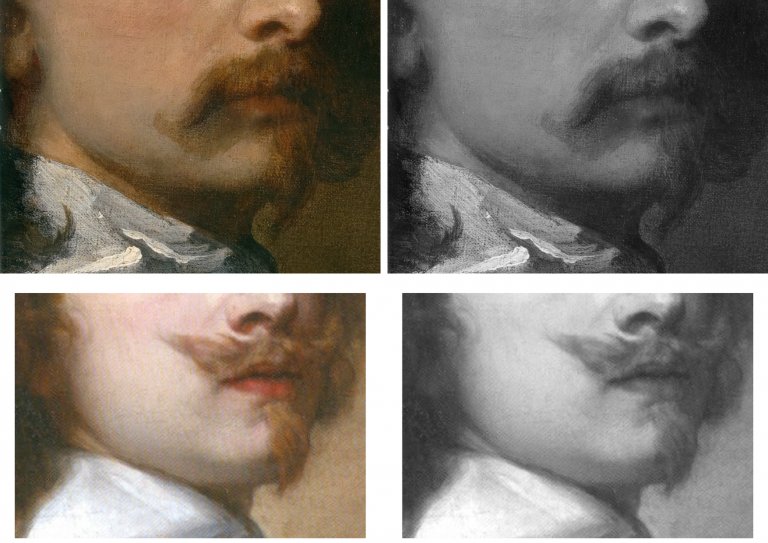

Above, Fig. 2: Left, the “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait” that was published in 1941 by Gustav Glück in The Burlington Magazine (“Reflections on Van Dyck’s early death”); right, the “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait” that was sold to the National Portrait Gallery in 2014.

Above, Fig. 3: Left, the “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait” as published by Glück in 1941; centre, the “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait” as sold to the National Portrait Gallery in 2014; right the painting published by Glück in 1941 as a copy by Sir Peter Lely of the Glück claimed last Van Dyck self-portrait shown left, here.

Above, Fig. 4: Left, the painting published by Glück in 1941 as a copy by Sir Peter Lely of the then-claimed last Van Dyck self-portrait shown above left at Fig. 3; right, the painting published in 2011 as a copy by Sir Peter Lely of the then-claimed last Van Dyck self-portrait at Fig. 1, left, which was sold to the NPG in 2014.

MILLAR’S WARNINGS

The notoriously vexing challenge of identifying autograph Van Dycks was set out with frankness and high expertise by Sir Oliver Millar, a former Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, in his contribution to the 2004 catalogue raisonné Van Dyck – A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, by Susan Barnes, Nora De Poorter, Oliver Millar and Horst Vey and published by the Paul Mellon Centre, London, the educational charity committed to supporting original research into the history of British art and architecture of all periods.

Covering Van Dyck’s last English period from 1632 to 1641, Millar listed 264 works and added an appendix of 37 works that comprise records of lost original paintings. Taken together they would average more than thirty-three paintings a year, including many double and very grand group portraits with brilliant elaborate costumes, accoutrements, settings, animals and part-landscapes but the work rate was even higher because of Van Dyck’s many and often long absences and periods of illness – he spent more than a year abroad in 1634-5 and suffered increasing pain in his painting hand. His employment of assistants caused some patrons to complain of work that was not autograph.

Millar assumed that Van Dyck had emulated the practices and “distribution of responsibilities as organised in Rubens’s studio” when setting up his own studio in London and he could hardly have spoken more bluntly of the artistic consequences of such production systems. A great deal of work “especially towards the end of his life”, he noted, “was assigned to Van Dyck’s assistants, and there was a heavy demand for repetitions, whether replicas, part replicas, variants or copies […] Sometimes Van Dyck would himself paint a new detail in a repetition otherwise painted entirely by an assistant”, whereas his “finest English portraits are painted…noticeably with a greater variety of touch.” A pronounced monotony of touch might itself, therefore, ring authorial alarms.

NEW EXPERTS ARE GROWING THE VAN DYCK MARKET

The art market correspondent, Colin Gleadell, restated the attribution problem in relation to current market expansionism, in the Telegraph (28 April 2018):

“Interestingly, Van Dyck has had more re-attributions than any other Old Master in recent times. Philip Mould, presenter of the BBC’s Fake or Fortune, traces this phenomenon to the publication of the first reliable catalogue raisonné in 2004, which allowed for detailed study of nearly 800 examples of the artist’s work.

“Of the catalogue’s four original scholars, only two are still alive, and a number of former museum directors have offered their views on attribution since. It’s differences in opinion that have allowed additional works to be added to the recognised Van Dyck corpus.

“Because Van Dyck was prolific and used studio assistants in his work, it can be tricky to unravel how much of a painting is solely by the master. Consequently, the number of works attributed to him, his studio and his many followers is plentiful. Around 300 have come up for auction in the last four years, with dozens subsequently upgraded with a full attribution.

“Taking some credit for the change in status was Mould’s researcher, Bendor Grosvenor, now a TV presenter in his own right and also a Van Dyck connoisseur, who has been quietly accumulating a small collection of discoveries of his own.

“But while Grosvenor prefers to keep his finds, his friend, Fergus Hall, is in the business of selling, his trained eye capable of recognising Van Dyck’s touch even through centuries of dirt, degraded varnish and additional paint. It is only after painstaking cleaning, though, that the full picture emerges…”

MAGICIANS ANNOINT SECOND-STRING WORKS

There exists an aggravating sub-phenomenon whereby venerable scholar/connoisseurs effectively acquire powers to elevate best available copies to autograph status. Some, like the late Sir Denis Mahon, have been known to elevate more than one such work to a single “vacancy”. (See “Art’s Toxic Assets and a Crisis of Connoisseurship”.) Occasional misattributions are inevitable (and correctable) in a field that necessarily rests on fine judgements, but wholesale upgrades risk diluting and adulterating oeuvres to the point of jeopardising market confidence. Risk is compounded when upgrades are products of prolonged restorations in which paint is subtracted and added to the surviving carcasses of pictures on singular, sometimes optimistic, readings of authorship.

BENDOR GROSVENOR’S ASSORTED CONTRIBUTIONS

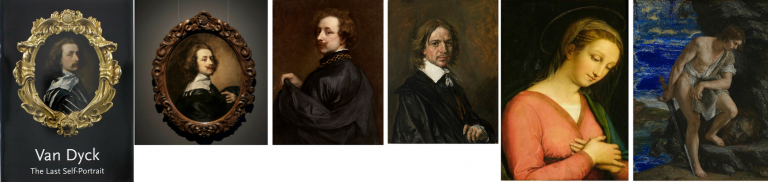

Above, Fig. 5: All six works above have been supported by Bendor Grosvenor.

The three recently and problematically upgraded Van Dyck self-portraits above left were all researched and espoused by Grosvenor. All three works on the right are manifest fakes. The Hals and the Gentileschi were initially accepted by Grosvenor and the “Raphael” attribution was made by him on television.

Respectively, the six are: left, the National Portrait Gallery’s “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait”, as shown on the gallery’s 2015 celebratory book on the painting; second left, Grosvenor’s own and self-upgraded “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait”, as loaned by him to the Rubenshuis Museum; third left, the privately owned, Grosvenor/Mould-attributed Van Dyck “Portrait of the Artist” that is now on loan to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; third right, the now notorious “Frans Hals” (which Grosvenor, the Louvre Museum and a London dealer took to be authentic before Sotheby’s proved by technical analysis that it was a modern paints-riddled fake and fully refunded its buyer ); second right, the self-contained painted fragment of a figure that Grosvenor held to be part of a larger Raphael panel on his BBC4 Britain’s Lost Masterpieces programme (5 October 2016) with near-unequivocal support from the National Gallery’s then director, Sir Nicholas Penny. (The “Raphael” was subsequently rejected and deemed possibly 18th century by the National Gallery in August 2019 following lengthy examinations, but Grosvenor still insists that Raphael had painted this fragment of a “Madonna in a Cross-over Dress” even though it had been painted inside the edges of a piece of wood and therefore could never have been part of a full panel painting); right, the fake Orazio Gentileschi David and Goliath painted on a lapis lazuli slab and which had been exhibited as authentic at the National Gallery when loaned by an anonymous private collector who had bought it from the dealer who had sold on the fake Hals through Sotheby’s.

RESTORATION “SCIENCE” AND THE DETECTION OF AUTHENTICITY

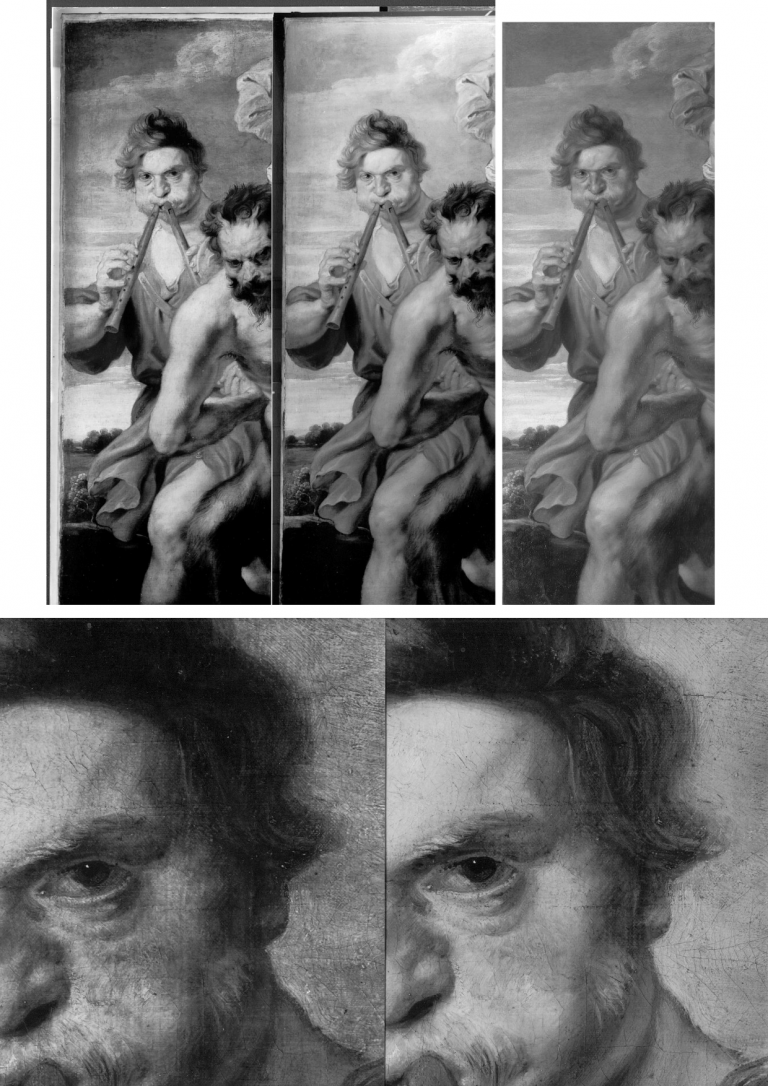

Even before Millar’s warnings, a non-art market exercise had confirmed the problem of identifying studio contributions in 1999 when, in the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin, the restorer Larry Keith reported that a recent restoration of the Rubens studio work Drunken Silenus supported by Satyrs (Fig. 6 below) had “allowed the opportunity to consider the questions around its authorship and execution afresh in the context of a collaborative technical investigation with the scientific department”. Despite the gallery’s advanced scientific apparatuses and its staffs’ best efforts, it was recognised that “The very nature of the Rubens studio, with its streamlined production and group participation, meant that the painting techniques and materials were also largely uniform, which inevitably limits the ability of technical study to inform specific attributional problems.” In the absence of documentation and relying “heavily on traditional style-based Morellian connoisseurship” the gallery attributed the picture to Van Dyck on a traditional appraisal by eye.

Above, Fig. 6: Above, top left and centre, photographs of a part of the National Gallery’s Rubens studio work Drunken Silenus supported by Satyrs, showing the work before restoration (left), after restoration (centre) and (right) as digitally presented today; below, a detail of a face before and after restoration.

As seen above, the pre- and the post-restoration states are artistically different in their tonal values and relationships. We have examined the National Gallery’s dossiers on the painting and the gallery kindly supplied the two good, hard-copy directly comparative photographs above, top. Where Gleadell shared the sleeper hunters’ proclaimed view of restoration as a benign and “enabling” process, careful comparison of the above detail of a face and its relationship to the foil of a background/sky before and after a single restoration show the debilitating disruptions of values and relationships (relative values) that can occur during a single restoration. Given that what comes off first under restorers’ swabs is what went on last with the artist’s brush, and that highly successful painters like Rubens and Van Dyck often touched up and finished off works that had been largely executed by assistants, it is not hard to appreciate how such subtractions through cleaning followed by painted additions can aggravate difficulties of attribution.

MADE-OVER UPGRADES

The principal instrument in art market upgrades is a long, supposedly “diagnostic”, visually transforming restoration. With dramatically altered pictures, scholars can more easily be chivvied to endorse new and elevating ascriptions. Few restorations give rise to downgrades. Sleeper hunters invariably swear by the brilliance and moderation of their favourite restorers and impute scientific veracity to their methods. In naïve non-specialist circles like the BBC, there exists an unexamined conviction that because today’s technologies are more advanced than earlier ones, aesthetic judgements are now scientifically validated. For example, in short £540 weekend courses at the Royal Academy (with light refreshments, an evening reception and a certificate thrown in), Philip Mould’s former apprentice, Bendor Grosvenor, (who read modern – not art – history and now works as a BBC television arts programme maker, art history blogger, occasional journalist, auction house director, a self-declared ex-dealer collector and, most recently, a picture restorer – see below), promises that “The theory and history of connoisseurship will also be explored, along with the latest scientific techniques for assessing attribution”.

There are no such techniques – science cannot appraise authorship. No matter how technically sophisticated “non-invasive” images might be, they still need to be read for significance. While the “scientific” technical analysis of pictures’ material components can readily disqualify attributed old master works that have been liberally constructed with modern materials, there are no scientific means of assessing authorship, per se.

VISUAL APPRAISALS

Painters make pictures by eye to be viewed by eye and appraisals must also be made by eye, as the National Gallery recognised with its Rubens school picture. When Berenson praised the “seeing eye” and “active not passive eyes” he meant eyes employed “with all the faculties co-operating” but in so-saying he spoke a (self-confessed) part-truth: “As a consumer of the art product I have the right to do all that. As I am neither figure artist nor architect, nor musician, I have no certain right to speak of the producer. I am in the position of most critics, philosophers and scholars. We have enjoyed experiencing the creative process in the art of words only with the logical result that writers on art seldom have in mind any of the arts except the verbal ones.”

Faculties, however refined and words however eloquent, are not the whole story. Too often overlooked is the extent to which for art-practitioners (artists) the powers of the eye are drilled into being both constructive and critical through the marriage of looking and doing that comprises artistic practice. Strictly speaking, that sequence should read: thinking, looking; doing; appraising; looking… Those who see-through-doing are best placed to recognise what counts as undoing and redoing in art. Best-placed but holding no monopoly – Millar fully recognised that restoration alterations handicap appraisals: “…the treatment it may have undergone in the past may also make it impossible to be entirely confident about its quality”. In this regard and for good reasons auctioneers place high premiums on little- or never-restored pictures.

TWO PUBLICATIONS FOUR YEARS APART AND TWO OVERLAPPING CAMPAIGNS OF ATTRIBUTION

Above, Fig.7: Top, left, the 80 pp full colour catalogue FINDING VAN DYCK , pub. PHILIP MOULD LTD, June/July 2011; top right, the Winter 2015/16 British Art Journal, which carried Bendor Grosvenor’s article “A Self-portrait by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) from the collection of Charles I”; above, left, the £10m National Portrait Gallery “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait”; above, right, the Grosvenor-owned, Rubenshuis Museum exhibited, “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait”.

SHARED EXCITEMENTS, RISKS, AND AVOIDANCE OF SIN

In 2011 Grosvenor, then an employee of the Philip Mould gallery, lauded the gallery’s (and later the National Portrait Gallery’s) “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait” picture in the FINDING VAN DYCK catalogue shown above, top left:

“Our first exhibit, Cat. 1, is Van Dyck’s last self-portrait. It was acquired by this gallery in partnership with Dr Alfred Bader in December 2009 for £8.3m at Sotheby’s in London, a record for the artist at auction. Self-portraits tend to stand out among a painter’s oeuvre as some of their most compelling works, and as an instructive connoisseurial guide in what an unquestionably genuine and pre-eminent Van Dyck looks like, Cat. 1 takes some beating.” (Emphases added.)

As fulsome advocacy the entry itself takes some beating. The FINDING VAN DYCK exhibition celebrated recently claimed works of or after Van Dyck and it constituted the high-water mark of Van Dyck sleeper-hunting at Philip Mould Ltd which became Philip Mould and Co. from which Grosvenor would depart in 2014 with a (rumoured) £1m settlement. Grosvenor seemed unaware that the Cat. 1 picture, then unsold after eighteen months in the Mould gallery, was a recent upgrade made by stealth and without due scholarly interrogation – see below.

The catalogue bore the gnomic dedication “For Dr Alfred Bader CBE. A distinguished progenitor of adventure in old masters”. Bader, an industrialist, philanthropist as well as an “inveterate collector”, as he once put it, died in December 2018 but he had been a key player in the Mould gallery’s acquisition of the “Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait” and its subsequent sale to the NPG. Bader and Mould seemed not to – but should – have appreciated how recently the painting had been upgraded. The NPG might not have been aware when buying the £10m painting as Van Dyck’s Last Self-Portrait that it was one of three Van Dyck self-portraits then being processed by the Mould gallery, one of which would shortly be presented as being both the true Last Van Dyck Self-Portrait and one with a better provenance, to boot.

LOVE IS ALL YOU NEED

In the catalogue’s foreword, Mould held that “every time a work of art is bought for reasons of love it is a discovery of sorts, albeit of a personal regard or strong emotional connection that has been visually crystallised” and that by “getting to know the signature strokes and habits of a great master, the characteristics of age, restoration and degradation, the [professional sleeper-hunter’s] eye becomes attuned, and even though there may not be many others around who can see it as you do, it can appear little short of sinful not to express the excitement of it all.” A note of anxiety crept into the self-exultation: the exercise of discovering, proclaiming, and selling lost masterpieces “involves excavation, science, observation and research – as well as a fair degree of sometimes hair-raising financial risk”. The precise burdens of risk and divisions of ownership are rarely disclosed.

WHO FUNDS ATTRIBUTION UPGRADES?

Clarity on ownership is occasionally achieved in the courts. Recent London Court of Appeal proceedings revealed that the fake Frans Hals (Figs. 5 and 9) had been bought jointly by a London-based dealer, Mark Weiss Gallery in Paris, and an investment company, Fairlight Art Ventures, for €3m in 2010 from the prime suspect in a French criminal investigation into a huge group of suspected fake Old Masters. The painting was sold in 2011 by private treaty through Sotheby’s (on a 5% commission) to the Seattle collector Richard Hedreen, for $10.75m. Weiss and Fairlight were shown to have taken an equal share of the benefit. See “’The law has to fall on someone’: Seller of allegedly fake Frans Hals must pay Sotheby’s $5.3m for cancelled sale, judge insists”, The Art Newspaper, 29 November 2020.

After discovering the fraud, reimbursing the buyer, and establishing a technical analysis department, Sotheby’s pursued the dealer, who settled first, and the investment company in protracted legal actions which were only resolved last November. In 2013 the now disappeared and Louvre Museum de-attributed $450m Leonardo School Salvator Mundi was sold by a consortium of New York dealers through Sotheby’s in a private treaty sale. The immediate flipping of the picture from $80m into $127m to a Russian oligarch triggered still-running legal proceedings. The London Court of Appeal held that at the time of the Hals sale there was “no general accepted view of the authenticity” of a “newly discovered painting which had no proper provenance, had not been published and had never been in an exhibition”.

NO FAKE-BUSTER, THIS ATTRIBUTION-MAKER

On 21 March 2016 Grosvenor reported that the London art dealer Mark Weiss had bought and sold-on the fake Orazio Gentileschi that deceived the National Gallery (Figs. 5 & 9). He also provided a (now inactive) link to Weiss’s catalogue note on the Gentileschi and asked: “Is the Gentileschi genuine? I suspect it is, but again I’m not a Gentileschi expert, and nor am I much good with late 17th Century Italian art anyway. My conviction about the painting, such as it is, must be led in part by the fact that greater minds and eyes than mine (not least at the National Gallery) have declared the picture not only period, but genuine… My best guess at this stage, working mainly from photos, is that these pictures are not all fakes.” In truth photographs should have sufficed and would have saved time expense and error. Grosvenor later wrote: “For what it’s worth, I believe it is a forgery. But it took me a long time, and a flight to Berlin to see an undisputed original Gentileschi for comparison, to figure it out.”