An (unpublished) paper by Michael Daley, Director, ArtWatch UK, that was delivered at the Economist’s Athens Conference, 12 March 2003:

Lots of reasons have been put forward in support of the campaign to remove the so-called Elgin Marbles from the British Museum. Individually, these justifications rarely withstand scrutiny, but cumulatively, their repetition has left many in Britain with the impression that under all the smoke there must be both a fire and a wrong in need of righting.

I wish to suggest today that, to contrary, there are good reasons for contending that the restitution campaign is itself wrongheaded, unjust and culturally dangerous.

The original removal of the sculptures from the Parthenon and the ground and the walls of the Acropolis by Lord Elgin has been presented as theft when the British Museum’s legal title is today accepted by all parties to the dispute. The removal has long been caricatured as vandalism and desecration when, demonstrably, it constituted an act of rescue and celebration. This fact, too, has now largely been accepted.

Faced with the legitimacy of the British Museum’s ownership, the would-be “restitutionists” have appealed above the rule of law to the forces of sentiment – and forces, often, of distinctly nationalistic sentiment. “These sculptures mean so much more to us than they ever could to you” it is said. And even more disconcertingly:

“Without these sculptures we are not complete as a nation, they comprise our very soul.”

It would be hard for anyone to resist such morally coercive appeals – and the British are constitutionally inclined to want to “do the right thing” but, as it happens, resistance is no longer necessary: Greek scholars have testified that although the Parthenon indeed was, for members of late 19th century Greek society, a sacred symbol of the nation, the rise in the 20th century of tourism and economic modernisation has “taken them out of their role as symbols and gradually turned them into social goods”.

Confirmation of this transition appeared with a recent announcement that Greece plans to replace low-spending tourists with high spending ones by “showcasing Greek cultural traditions”.

With the decline of appeals to nationalistic sentiments, the claims of an Urgent Aesthetic Imperative have been advanced. “It is a crime against art”, the argument goes, “not to allow the component parts of a glorious entity to be seen whole.”

The cult of the dismembered-whole-in-need-of-reintegration was launched in 1945 by Thomas Bodkin with his seminal book Dismembered Masterpieces – A plea for reconstruction by International Action. It certainly is sad when artistic ensembles are scattered by history but in the case of the Parthenon sculptures it is worth recalling Bodkin’s comments on them:

“It is abundantly clear that the statues from the pediments, the portions of the frieze and the metopes now in England should never be re-integrated on their original sites. Those few sculptures which Lord Elgin did not remove have in the intervening one hundred and forty-two years been allowed to deteriorate into utter wreckage, corroded by wind and rain and the fumes ascending from the factories of Piraeus”.

Bodkin of course did not know of the notorious Athenian pollution that would be in train from the 1960s. Greek scholars have testified to the devastating consequences for the Acropolis monuments of that further, later pollution.

In the view of many here and abroad, Greece’s own past neglect and mishandling of the Parthenon and its remaining sculptures constitutes one of the greatest 20th century art conservation tragedies. To those of us who are professionally dedicated to the survival and welfare of art, the vocal opposition of Greece’s own scholars and art lovers to today’s Government-led scramble for development is certainly heartening but it does also confirm that vital lessons have not yet been learnt. These developments compel the observation that a nation that is showing indifference to its own patrimony and is cavalier with even its most precious historical sites, does not need to take on more heritage responsibilities. To those who might feel such a judgement harsh, we cite a single plea. It came recently from the island of Paros.

“…We are therefore obliged to ask for the support of the international academic community, suggesting that our overseas friends mail letters of protest to the Greek Minister of Culture, underlining their concern about the deliberate destruction of monuments on Paros. How is it possible to demand the return of the Parthenon marbles, while allowing the ruthless destruction of other ancient temples by unqualified employees?”

In the face of this actual, ongoing destruction, British restitutionists and museum personnel have taken to fretting about a need for “context”. What context? Reuniting the Elgin sculptures with the decaying Parthenon building is now, as Bodkin could already see, impossible. The new sculptural ensemble being mooted for Athens is that of a wholly severed – and, in fact, distinctly out of context collection. That is, it would be indoors, not out. It would be off Acropolis, not on. Even if every museum presently holding Acropolis sculptures were to return their works, the new “entity” would still remain incomplete because of early losses.

More embarrassingly, if all the surviving sculptures were to be returned to Athens tomorrow, they could not be joined by Greece’s own west frieze sculptures, which were removed from the Parthenon ten years ago and still await a decision on possible conservation treatments to stabilise their pollution-damaged surfaces. Were this problem to be resolved, it would still be necessary, before any assembling of the survivors could take place, for the sculptures that presently remain united with the Parthenon, to be “dis-united” from it, as if in emulation of Lord Elgin’s long condemned original actions.

In truth, of course, the Parthenon sculptures can never be “shown in context” because their original context is so long gone. It might now be imagined but it can never be replicated. We do know, however, that the sculptures originally survived as symbolic adornments to a temple standing on a reinforced hill and not in a modernist museum, to be built on stilts, on an important archaeological site in an earthquake zone and in the teeth of opposition from national and international scholars. Far from there being plans to recreate the original on-Acropolis context, there are even plans to remove, what one leading restitutionist terms, “the litter of unclassified stones” from the Acropolis in order to make more footpaths for more tourists. This is a particularly alarming prospect if Professor Snodgrass’s claim that eighty per cent of the Parthenon building is believed to be still present, is correct. There is, however, something much more important at stake in this dispute than the preservation and the right displaying of historical artefacts.

As mentioned earlier, the present hectoring demand that sculptures be moved from one museum to another is unedifying and dangerous. For one thing it constitutes nothing less than a government-led assault on the very idea of the internationally comparative museum. Greece – of all countries – does not need to be party to such a regressive manoeuvre.

It jeopardises international scholarly cooperation. It gives encouragement to those members of the museum sector in Britain who seem only too eager to shed as much as possible of what they see as so much colonial loot. I do recognise that members of the Greek Government have shown themselves to be aware of some of these dangers and that they themselves insist that the Elgin Marbles are the only sculptures for which demands will pressed. But what politician was ever able to bind his successors? Who today could guarantee that the removal of the Elgin sculptures from the British Museum would not instantly and forever thereafter be taken as a precedent for copycat campaigns in Greece and elsewhere?

For this artist, what is most saddening about the present campaign is that by trading the universal for the local, it conspires against a proper recognition of the true nature and full extent of Greece’s patrimony. There is a lot of wonderful art in the world but the truth that is being lost in this squabble over particular material objects is that Greek classical art is like no other art – it has done what no other art has ever done: millennia after its birth, it has emerged from death and neglect to seize the imaginations and enlist the passions of other people in other places. Greek classicism has even vanquished, later, better-preserved classical offspring. It has done so not by conquest or politicking but solely on merit; by example; on the unrivalled authority of its inventions. It is unfashionable to say so, but these inventions stand uniquely transcendent and enduring, outside of time, original context and regardless of geography and ethnicity, as artistic paradigms and exemplars.

Even within the antique world, Plutarch had marvelled that the sculptures of Pericles’ time, far from dating, retained a time-defying freshness and newness – as masterpieces. In the 19th century Karl Marx was stymied by the sheer force of Greek Art – to which, as a scholar at the British Museum’s reading room, he was regularly exposed. Marx’s grand meta-system was to be elegance itself: the so-called cultural superstructures of societies stand on, and are determined by, their economic bases; by their technical means of production. The more advanced the means of production, the more advanced the cultural manifestations. Primitive, economically backward societies, he planned to demonstrate, produce primitive backward art. Classical Greek art, however, blew this premise. How could it be, Marx was forced to ask himself, that an ancient art should not only continue to afford us with pleasure but should persist beyond its own time as both a standard and an unobtainable goal? The best explanation he could offer was that Greek art remained eternally charming because it represents the “the historical childhood of humanity, where it had obtained its most beautiful development.” This condescension will not do.

Greek forms have gripped modern minds, in world superpowers like Britain and the United States, not by their charm but by their potency, and their living relevance. Colonialism exposed modern Europeans to the charms of very many competing aesthetic value systems, but the power of Greece’s artefacts has remained uniquely awesome and persuasive – wherever they have come to rest.

The Greek temple, for example, stands perennially iconic as motif. It remains unequalled for its combined lucidity of construction and elegance of articulation. Which is why, for example, it remains incorporated into the fabric of Britain’s premier motorcar, the Rolls Royce – and with a winged victory as mascot on its bonnet. The Greek temple – and not, say, the pagoda – is as deeply entrenched in the modern unconscious as any Jungian archetype. Simultaneously, it confers dignity and reassurance to banking and stands guardian to free speech and debate in our modern universities and seats of government. In London, next to the historic Tower of London, a temple provides home to the names of British merchant seamen who perished in the Atlantic and Mediterranean at the hands of German U-boats and bombers.

Given the chance, Greek sculpture is seen to stand supreme in all company, in whichever museum – the bigger the museum, the greater the victory. The grandly ambitious international museum is now coming under fire politically, but it has been both an expression of and an agent for the modern renaissance of Greek antiquity. It is barely half a century since an historian like Hans Tietze could describe the artistic individuality of great museums as themselves “spiritual entities, and not merely as fortuitous accumulations of art treasures.”

Under today’s rules of correct, multi-cultural, discourse, museums like the British Museum may no longer say that ancient Greek art stands as the world’s best, as the most attractive and most humanly affirmative. But nowhere is this trait more apparent than in Bloomsbury in London, in the British Museum. By Insisting on seeing international, multi-cultural museums as repositories of loot; by fetishising original architectural/social contexts and localities; and by fostering nationalistic sentiment, we risk losing sight of a fundamental artistic truth: the sheer stand-alone transcendent quality of Greek sculpture. Pericles was given to inviting his dinner guests to see the Parthenon sculptures as they were being carved. Everyone who passes through London today can dine for free at Pericles’ table in a splendid purpose-built neo-classical hall – and certainly not in a cellar or basement as British restitutionists too often allege. It would be a tragedy if these supreme ambassadors for the finest art of sculpture were to be wrenched out of the great world forum of cultural voices that the British Museum comprises and in which they excel. Greece truly does not need to be party to such a brutal, disruptive act. Greece thrives, looks her very best in such elevated and various company. She lives. She needs nothing. Her primacy is absolute and unassailable. Well should be left alone.

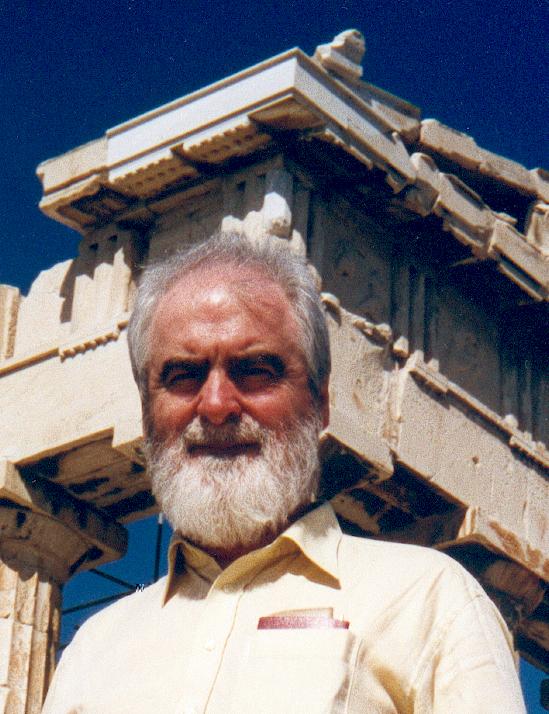

Above, Michael Daley, Director ArtWatch UK, at the Acropolis, Athens, 2003.

CODA

The Economist conference – and the campaigning contribution made by Lord (David) Owen – was reviewed in the Greek newspaper eKathimerini – as is today’s meeting of Prime Ministers Keir Starmer and Kyriakos Mitsotakis in London.

In August 1998 a correspondent in the Sunday Times’ books section wrote (under the heading “All Greek”):

“A more positive and generous list of the achievements of the ancient Greeks than Frederick Raphael’s more grudging one is given by the scholar F L Lucas: ‘Within seven centuries this race invented for itself epic, elergy, lyric, tragedy, comedy, opera, pastoral epigram, novel, democratic government, political and economic science, history, geography, philosophy, physics and biology; and made revolutionary advances in architecture, sculpture, painting, music, oratory, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, anatomy, engineering, law and war… a stupendous feat for a race… whose most brilliant state, Attica, was the size of Hertfordshire, with a free population (including children) of perhaps 160,000′!”

In February 2000 we wrote (in “Pheidias Albion”, Art Review):

And let no one believe that foreigners alone reject Greek demands or condemn Greek practices. A few years ago, The Times carried this plea from Mrs Magdala Delfas:

“When in 1967 I left Greece under the colonels’ rule, my visits to the British Museum brought me solace. I was able to keep in touch with my cultural heritage outside the geographical and political confines of Greece.

“Later, I discovered to my delight and amazement that apart from the perfect display of the Elgin Marbles in their special gallery, they are kept in a country where the study of Ancient Greece is kept alive, where Greek plays are performed either in the original or in English, and in the most erudite and scholarly fashion, like the Theban plays by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford last season and in London this year.

“Schoolchildren, among them my own son, have the privilege and joy of reciting verse and studying Homer in the original. By contrast in Greece, the study of ancient Greek in schools has been stopped. The impoverished language of today has been cut off from its natural roots.

“Visitors to museums (including that on the Acropolis) are frustrated by restricted opening times and high admission charges. Moreover, a new gallery close to the Parthenon to house the marbles would violate the Acropolis.

“The advocates of the demand for the return of the Elgin marbles, which stems from empty nationalist zeal and socialist politics, should direct their zeal and support towards Cyprus. The marbles must remain where they are, in a country which cherishes the classical tradition.”

3 December 2024