Provenance, Dendrochronology, and the Collapse of a Faulted Construction

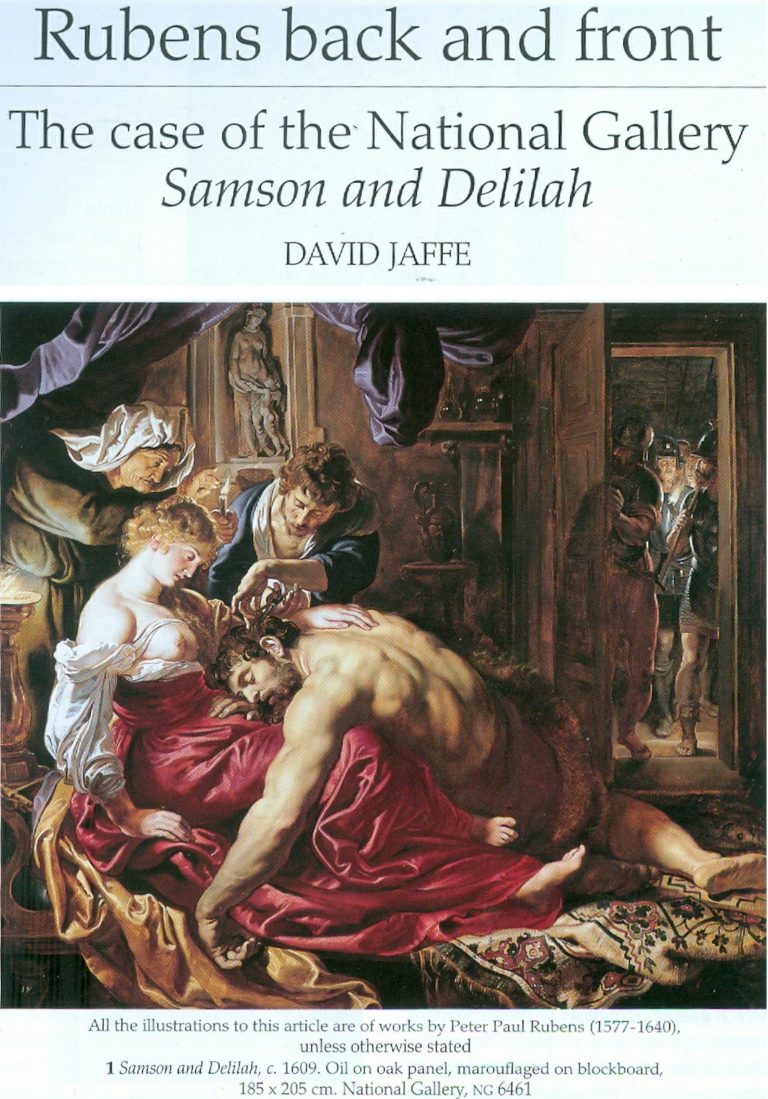

Above, Fig.1 – David Jaffe’s August 2000 Apollo Article*

[*In July 2000, journalists were called to a National Gallery press conference at which an officer declared that David Jaffe’s forthcoming article “will finally silence the critics for ever”.]

Jan Geschke is an art historian who studied with Meyer zur Capellen and Wilhelm Schlink and has recently been instrumental in correcting the consensus, ranging from Lucio Fontana’s fascist leanings to the real face of Raphael’s Madonna of the Pinks.

Since 1980, the National Gallery has presented a consistent account of the modern history of its painting Samson and Delilah. According to this account, the work was rediscovered in Paris in 1929 when the Berlin art dealer Curt Benedict unearthed it in the atelier of the restorer Gaston Lévi; it was subsequently authenticated by the Rubens specialist Ludwig Burchard and then acquired by the collector August Neuerburg. This sequence has since functioned as the painting’s point of entry into modern scholarship.

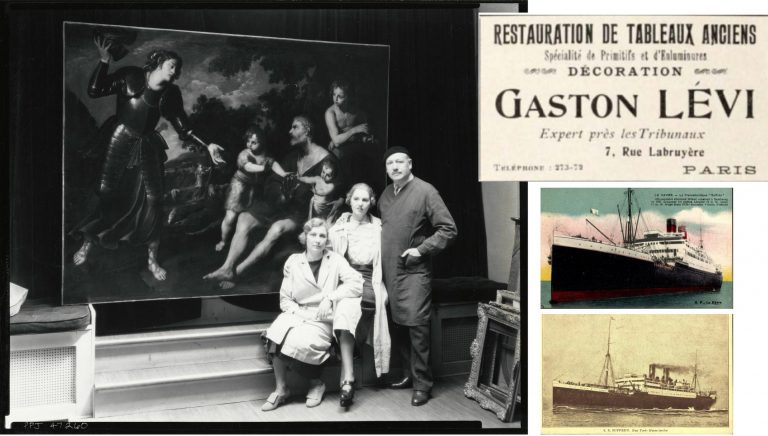

Above, Fig. 2 – Shepherding wealthy socialites in New York City instead of German art dealers in Paris – Gaston Lèvi himself after having left from Le Havre in Oct.27 on steamer SUFFREN, taking his business (here with an earlier advertisement) with him. The Vaccharo he restored ended up with the Lehman Loeb family.

The latest National Gallery narrative does not withstand factual scrutiny. Through joint research conducted by the art historians Jan Sammer (Mariánské Lázně / Marienbad) and Jan Hendrik Geschke (Hamburg), it has now been established that Gaston Lévi emigrated from France to the United States in 1927 aboard the SS Suffren as passenger no. 220 and did not return to Paris thereafter (Fig. 2 above). A discovery in Lévi’s Paris atelier in 1929 is therefore impossible. This removes the factual foundation on which the National Gallery’s post-1980 account rests.

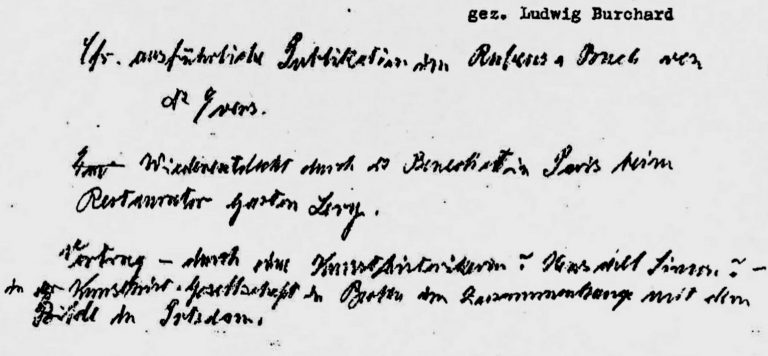

The documentary material cited in support of that account proves equally problematic. The handwritten annotations frequently described as “Burchard notes” beneath a typed copy of Burchard’s certificate of authenticity are not in Ludwig Burchard’s hand, as established by Sammer and Geschke (Fig.3 below.) They do not date from around 1930 and they twice refer explicitly to Hans Gerhard Evers as an authority – an SA member later granted an honorary professorship by the Reich – and his Rubens-Book of 1942. These annotations therefore postdate the alleged rediscovery by at least a decade and cannot be regarded as contemporaneous evidence. No primary documentation from around 1929 substantiates the Paris atelier episode as has long been rehearsed.

Above, Fig. 3 – Non-Burchard handwriting on a typed copy of his supposed authentification by an unknown

Above, Fig. 4 – Rubens-specialist Prof.h.c. Captain (art protection) Dr. Hans Gerhard Evers sacking Paris in 1941 (right) and Italy in 1944 (sic) as a Lieutenant-Colonel Prof.h.c.

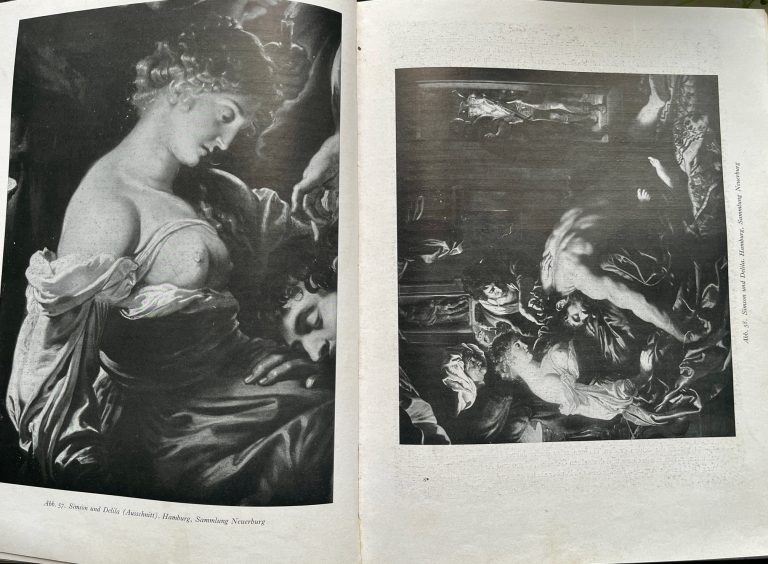

Above, Fig. 5 – “Strong, hard woman” Delilah in Hans Gerhard Evers: Peter Paul Rubens (sic), Munich 1942, 525 p. “on the order of the High Command of the German Army” (foreword).

The painting enters the scholarly record as a Rubens attribution only in 1942, through a publication by Hans Gerhard Evers (Fig. 5, above). Issued within a National Socialist art-historical programme commissioned by the High Command of the Armed Forces, the text reframed Rubens as a Germanic painter of force, struggle, and bodily domination, celebrating the aestheticisation of violence. Evers’s role was not confined to interpretation. During the Second World War he held a Wehrmacht mandate as a captain in the “Kunstschutz“ – art protection (sic) – and was entrusted with the systematic seizure and forced transfer of artworks in Paris, Antwerp, and Italy. The first sustained presentation of Samson and Delilah as a Rubens thus belongs not to pre-war academic discourse but to an ideological wartime context shaped by cultural plunder.

The collecting environment in which the painting circulated at this stage is equally specific. August Neuerburg, based in Hamburg, controlled a near-monopolistic share of the German cigarette market—approximately 82 per cent during the war years. In this period, he was closely connected with Hermann Göring as both economic partner and fellow collector. Göring’s collecting of Rubens began only after assuming command of the Luftwaffe and gaining access to systematic plunder across occupied Europe. Neuerburg’s cigarette enterprise paid approximately 18 million Reichsmark to Göring during these years, coinciding with the latter’s rapid expansion as an art collector. A documented transaction further links the households: Neuerburg’s wife sold an early Dutch child portrait to Göring’s wife, Emmy Göring, on the occasion of the birth of the regime’s celebrated war-hero’s daughter.

The immediate scholarly point of reference for the present re-examination is a defence of the Rubens attribution published by David Jaffé, then Senior Curator of the Dutch and Flemish Schools at the National Gallery (Pic.1 above). In his article “Rubens back and front: the case of the National Gallery Samson and Delilah,” published in Apollo in 2000 (no. 462, vol. 152, pp. 21–25), Jaffé reaffirmed the attribution and grounded it in the same provenance narrative and documentary material, adding dendrochronological claims attributed to Professor Peter Klein of Hamburg University. The continuing authority of this article prompted renewed scrutiny.

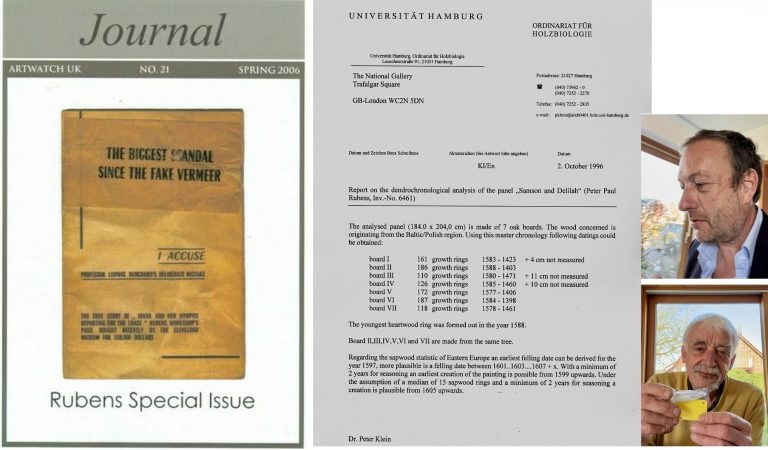

Against this background, ArtWatch UK which had rejected Jaffe’s account in its 2006 Rubens Special Issue Journal, asked Geschke to examine the technical claims involved. On 4 January 2026, Geschke spoke directly with the dendrochronologist Peter Klein.

Above, Pic. 6 – Left, the second AWUK Rubens Special Journal; centre, Dr Peter Klein’s, 1996 Report on the National Gallery Samson and Delilah; right, top, Jan Geschke; below, Dr Peter Klein.

Klein’s position in Rubens studies is foundational. In 1985 he established that Rubens consistently used Baltic oak rather than locally sourced Belgian oak for his panels, based on fieldwork in Poland conducted with two colleagues and subsequently published. He has further emphasised that it is normal for Rubens panels to have numerous “siblings” from the same tree across different works, since Rubens purchased complete Baltic oaks. In a 1997 report for the Berlin State Museums, Klein documented such a family tree for the Rubens panel Isabella Brant, identifying wood from the same trees in no fewer than thirteen other Rubens paintings. Other works, by contrast, demonstrably combine boards from several different trees.

Against this material practice, Samson and Delilah is doubly anomalous. Klein stated that he has never said or written that the National Gallery’s painting is by Rubens and that authorship judgments fall outside the scope of dendrochronology. He also stated that he never wrote a letter to the National Gallery expressing opinions on the work, despite such a letter being cited by Jaffé with a specific date.

Klein further stated that he does not know when or where dendrochronological examinations of Samson and Delilah or the Antwerp Raising of the Cross were carried out by the dendrochronologist Vynckier; that he was never approached by that colleague; and, that no exchange of results took place. Most decisively, he addressed the claim that board 6 of Samson and Delilah derives from the same tree as panels of the Raising of the Cross. According to Klein, Boards 2–7 of Samson and Delilah derive from the same tree. On dendrochronological grounds, this means that either all of those boards would match another object at tree level, or none would. He stated this explicitly in writing to Geschke on 23 September 2025 and reiterated it in their telephone conversation of 4 January 2026.

Even more unsettling is his next observation: concerned that he had been cited incorrectly 25 years ago in a matter this important, he compared Samson and Delilah’s seven boards to all boards of all 400+ Rubens in his database. He could not find a single match. Which is another rare outlier in a case full of outliers, to say the least.

As Sammer and Geschke observe, a panel composed of six boards from one tree combined with a single board from another constitutes a marked anomaly within Rubens’s established working practice. For what reason, and at whatever stage in the painting’s history the upper board was added, remains an open question requiring scrutiny. The irony that a “Rubens” hidden in Hamburg’s biggest flak bunker from the RAF’s local efforts provoked by ardent collector Hermann’s earlier Blitz on London while Neuerburg-fag smoking V1 crews unsuccessfully tried to erase Trafalgar Square, is now being defended tooth and nail by the very institution these fans of the Flemish school set out to annihilate was until now hidden from the art loving British public.

With the added board, the thusly altered format of the Evers-accredited picture became laterally constricted compositionally – as seen below – when compared with the lost original Rubens picture, as copied by F. Franken (below, top). The late-appearing picture (below, bottom) not only shed half of Samson’s foot, much of the crone/procuress’s body was also cropped. The engraved copies are consistent with Francken’s painted copy and not with the present pride of the National Gallery’s collection as shown below, bottom.

Above, Pic. 7 – The Frans Francken copy (top) vs. the National Gallery Samson (below). Note the different proportions of bodies and heads, the very different handling of space and some charming idiosyncrasies in foot handling and the ceiling vulva allusion’s position.

Jan Hendrik Geschke, 13 January 2026