ArtWatch at Thirty, Part I: The Unstoppable, “Rapidly Filed Away” Sistine Chapel Restoration

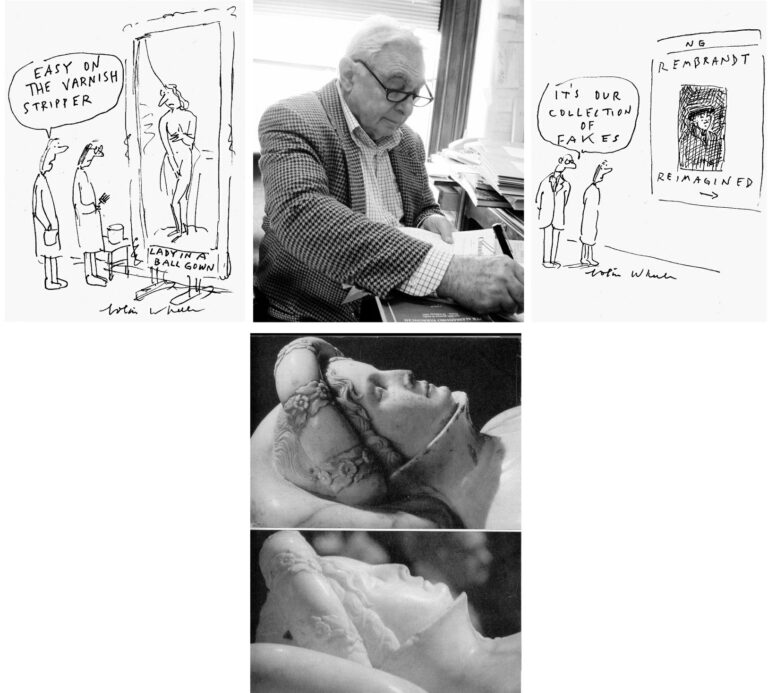

Michael Daley writes: November this year will mark ArtWatch International’s thirtieth anniversary and May 26th marks the fifteenth anniversary of the death of its founder, James Beck, Professor of Renaissance Art History at Columbia University. After facing down a possible three-year jail sentence and punitive damages on charges of criminal slander for condemning a restoration that had left Jacopo Della Quercia’s beautiful marble Ilaria del Carretto looking like oiled soap (Fig. 1), Beck created ArtWatch International in 1992 to speak for a proper and due stewardship of works of art. His “trials”, however, had begun half a decade earlier when he supported artist critics of the Nippon Television Corporation-sponsored and filmed restoration of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes – which act of artistic solidarity was taken by the restoration’s high-placed art historian apologists as an unforgiveable professional betrayal.

Throughout the famously contested* Sistine Chapel ceiling restoration it was politically impossible for the Vatican to admit error and halt the multi-million dollars NTV-filming. This obliged the authorities to permit nothing to count against the restoration. While disregarding and dismissing all contra-testimony, the Vatican’s restorers, curators, and art historical supporters claimed that things had occurred for which no evidence exists and denied the existence of things on which evidence abounded.

[* “The restoration of Michelangelo’s magnificent frescoes in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel is perhaps the most controversial event in the art world in the past three decades” – Pierluigi De Vecchi and Gianluigi Colalucci in Michelangelo The Vatican Frescoes, the Vatican’s 1996 final account of the restoration.]

Above, Fig. 1: Top, centre, Prof James Beck (Photo: Lynn Catterson); Cartoons by Colin Wheeler; above, centre, the marble Ilaria del Carretto tomb sculpture before (top) and after the restoration in which it was both abraded and oiled.

AN ABIDING CULTURAL CONUNDRUM

Revisiting that momentous 1980-1994 battle after three decades – and when variously armed with the complete published Vatican restoration literature (see Endnote 1), the study of scores of conservation dossiers in major public institutions, and the preparation of countless visual arguments against mis-restorations and misattributions – it is now clearer than ever that much as the restoration of the Sistine Chapel ceiling was an artistic abomination it was not an aberration. It was not the only great fresco cycle to have been chemically assaulted, stripped to its bare plaster surface and left artistically debilitated, falsified, and looking as never previously seen.

The successive Sistine Chapel mis-restorations (- of the lunettes, the ceiling and the Last Judgement wall) occurred within a remorselessly expansionary nexus of lavishly sponsored conservation sensation-seeking* techno-adventurism in which the intervals between restorations on major works have now dwindled to… almost nothing. In effect, the fabric of art heritage has become host to a self-propelling, self-regarding, socially favoured, artistically and culturally impoverishing job-creation engine in which every generation of restorers works-over every major work of art as of right and in response to some conjured “conservation necessity”.

[* Restorers at the Sistine and Brancacci chapels revelled in anticipated scholarly upheavals that would attend their chemical radicalism. Some years ago, the British Museum and a newspaper arts journalist combined to run a course that coached restorers on planting promotional press coverage.]

A day does not pass without press reports of some solvents-armed heritage operative having painstakingly subtracted this while “discovering” that. Despite this omnipresent PR tide, no one ever says: “This work is in marvellous condition – it has been restored x times in the last fifty years.” Auctioneers boast of excellent condition with never, or little-restored works and the term “untouched” remains a bankable guarantor of retained authenticity. Deference to conservation’s artfully cultivated mystique rests on a double sleight of hand. Deemed “picture rats” in the nineteenth century, restorers rebranded themselves “picture-surgeons”, assumed quasi-medical airs and dubbed their research “diagnostic”, their actions “treatments”, their studios “laboratories”, and their students’ “interns”. Their greatest wheeze was adopting the morally coercive appellation “conservators” as a shield against interrogation and disinterested appraisal.

THE ANTI-CRITICAL IMPERATIVE

James Beck, a highly respected Renaissance art scholar, had trained first in fine art and then politics. He appreciated that no sphere of professional activity should be free from scrutiny and appraisal, not medicine, not aeronautical or civil engineering, not art administration or restoration. Every artist, actor or musician is subject to professional critical appraisal – why, then, should those who act on and alter art evade critical evaluation?

NEEDLESS INTERVENTIONS?

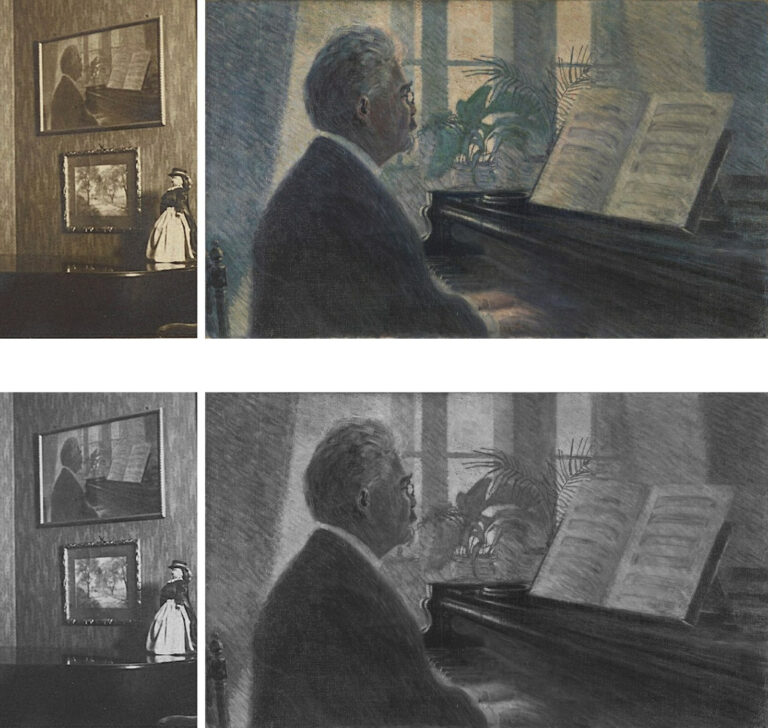

Above, Fig. 2: Left, a 1930 black and white photograph of Egon Schiele’s recently found early portrait – right, Schiele’s “Leopold Czihaczek at the Piano”.

To give a current example of the compulsions to “restore” works: on 5 May 22, Artnet reported that a lost early Egon Schiele portrait has been found and that, despite seeming to be in excellent condition (as above), it is to undergo restoration.

The picture has been loaned for five years to the Leopold Museum which wishes to buy it. Because the museum’s finances have been hit by the latest Chinese plague, a plan has reportedly been devised to created NFTs (non-fungible tokens) of the work in editions of 100, 10 and 2, for €500, €15,000 and €100,00 respectively, with the hoped-for proceeds total of €400,000 going “towards the cleaning and restoration of the painting”. “Towards”? And the “restoration” of what? The above comparison of the painting today with a 1930 photograph suggests no apparent visual deterioration.

The museum’s director, Hans-Peter Wipplinger, speaks frankly: “We start with the physical object, then we make a digital image and, if we can sell it, we can afford the painting.” Thus, a museum proposes to sell virtual reproductions of a likely never-restored painting as if in lieu of a slice of the painting itself but, if enough money is raised, will alter the painting by “restoring” it, which act will leave the NFTs standing in lieu of the picture’s disappeared earlier untouched state. A mere incanted proposal to restore seems to stand as a talismanic signifier of high moral and artistic purpose. This case is no aberration: on acquiring works in excellent condition museums routinely plunge them into restorers’ tanks to make them their own through restoration alteration and published “research findings”. See:

“An ominous silence at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York”; “Discovered Predictions: Secrecy and Unaccountability at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York”; and “Why is the Metropolitan Museum of Art afraid of public disclosures on its picture restorers’ cleaning materials?”

THE RISE AND DEMISE OF RADICAL ART CONSERVATION FADS

The 1980-1994 Sistine Chapel saga was launched on a whim with a new, aggressive, insufficiently tested cleaning agent at a moment when the discredited Italian mania for ripping frescoes from chapel walls was being replaced by fresh absolutist quests for intensified colour in ancient painting and for brilliant whiteness in ancient sculpture and buildings. For a massively falsifying modernist chemical imposition of intensified whiteness throughout a great cathedral, see: “Brighter than Right, Part 1: A Modernist Makeover at St Paul’s Cathedral” ; and, “Brighter than Right Part 2: Technical Problems of Protection, Health and Safety at St Paul’s Cathedral”.

For the most shameless and brazen art institutional PR glosses on catastrophic restoration injuries, see: “Hyping museum-restoration wrecks”; “And the world’s worst restoration is…”; and, “The world’s worst restoration and the death of authenticity”.

THE INSINUATION OF ALIEN AESTHETICS AND ANATOMICAL DEFORMITIES INTO OLD MASTERS’ PAINTINGS

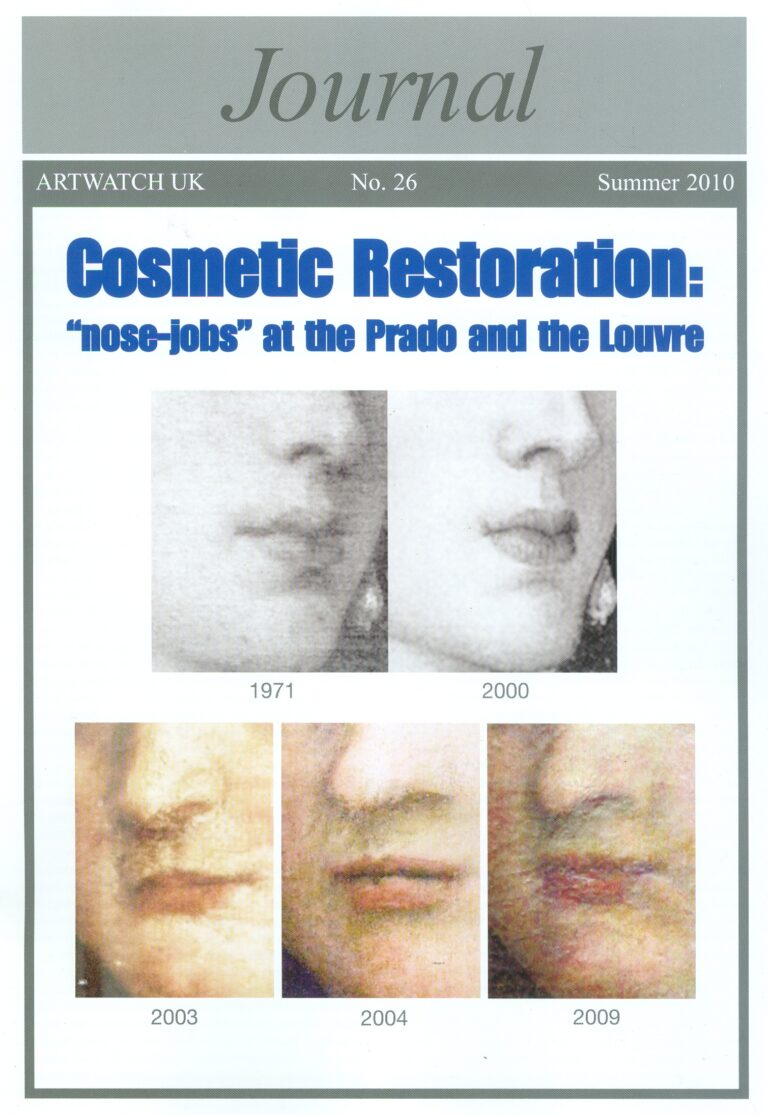

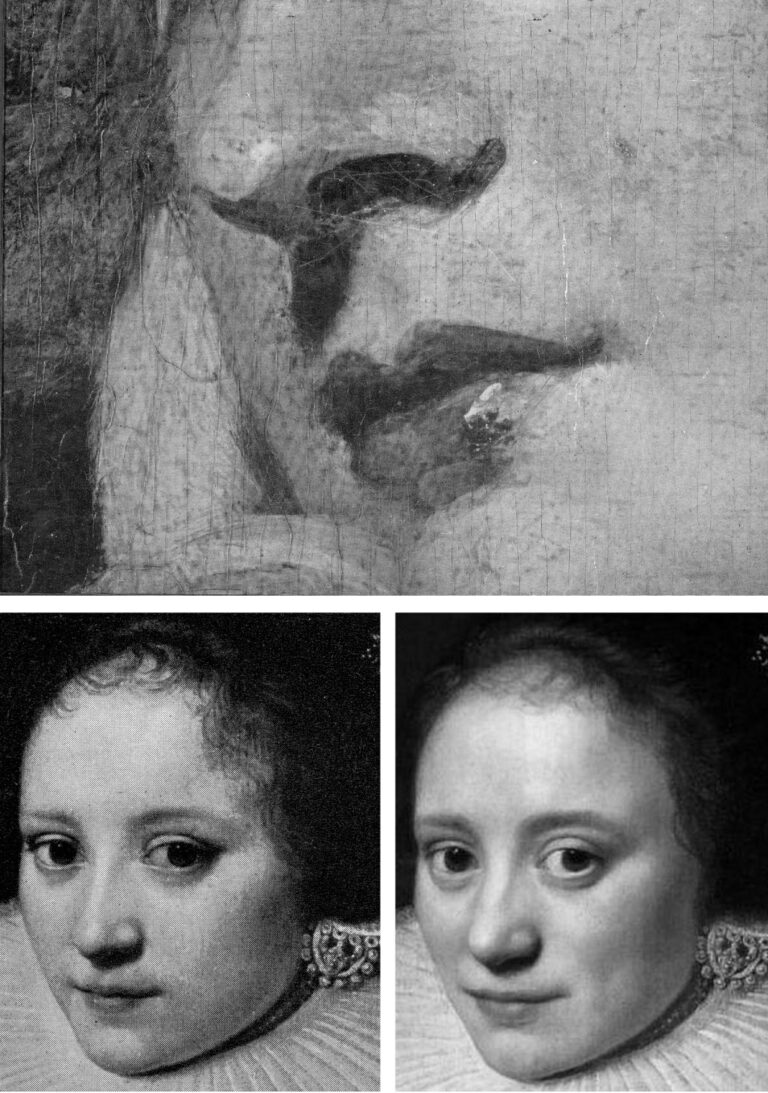

Above, Fig. 3: Mistreatments of a Titian at the Prado and a Veronese at the Louvre.

Above, Fig. 4: Left, top and centre, restoration changes made to facial features in Veronese’s Pilgrims of Emmaüs at the Louvre (top) and Titian’s Empress Isabella of Portugal at the Prado; right, top and centre, diagrams of the same illustrating unwarranted restoration changes of drawing and anatomy on works in major museums; above, three photographs of actual nose/mouth configurations and, right, a drawing (by the author) of the head of Klimt’s Judith II.

As seen above, the restorer of the Prado Titian greatly enlarged the nostril and moved the lower nose from the nasal groove and tucked it behind one of the two ridges that define the groove, as if in homage to Picasso-esque cubist contortions. As shown in the bottom row above, the base of the nose always sits centred above the top of the nasal groove. While necessarily following anatomical laws, individual mouth/nose configurations are highly distinctive and expressively mobile – which is why portrait painters pay the greatest attention to their precise depictions. Everybody is a connoisseur of mouths’ fluid and elusive expressions – hence John Singer Sargent’s rueful description of a portrait as “a picture in which there is always something not quite right about the mouth”. No power on earth can stop restorers from undoing and redoing that which they fail to comprehend.

Above, Fig. 5: Top, a detail of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ Mrs Bradyll, as carried on the cover of the 1942 edition of Bertram Nicholls’ Painting in Oils; above, left, a detail of the Wallace Collection’s A Dutch Lady by Michiel Jansz Van Mierevelt; above, right, the same Dutch lady after a 1986 cleaning at the Wallace Collection in which all the features were coarsened, the hair was thinned, and the jewellery dimmed. Note, for example, the thickened edges of the lower eye lids; the expression-changing greatly widened (true left) upper eye lid; and how the nose’s former thin highlight has been widened and deflected by a new bump.

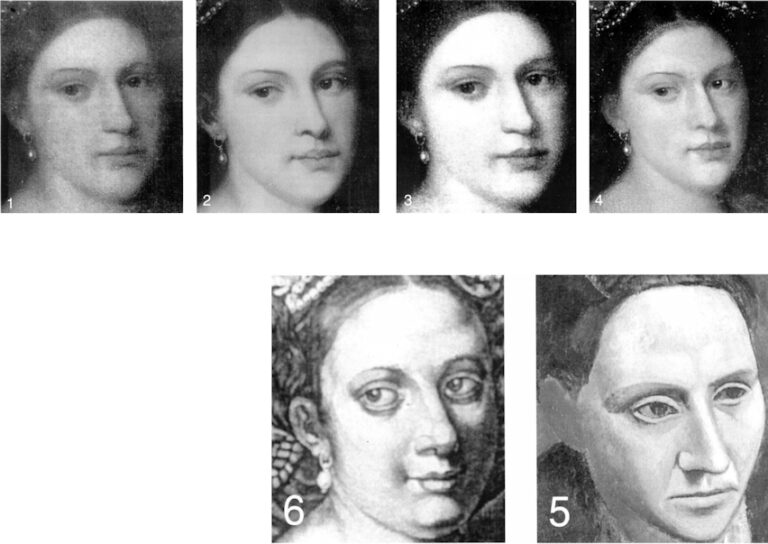

Above, Fig. 6: Top, nos. 1 to 4, a privately owned accredited Titian portrait (Laura de Dianti) after successive modern restorations; above, left (no. 6) a contemporary engraved copy of the original but now many-times changed portrait; above, right (no. 5) Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein.

It is striking how greatly more sculptural and anatomically sound the head had been when rendered by light and shade in an early engraved copy than in any of the restored states of the painting. Successive restorations imposed a modernist mask-like aspect on a refined in-depth Renaissance conception. The engraved record of the subject’s up-turned nose highlights modern restorers’ arbitrary and anatomically ill-informed impositions on eyes, mouths, and noses. The arch of the nostril rises and falls in a succession of variations on a theme in which each restorer “corrects” the previous state without ever recovering the originally recorded state. The eyes fall out of alignment, focus and life, as in the Picasso portrait. On official, highest-level indulgences of cosmeticizing “picture surgeons”’ nose- and eye-jobs, see:

“Something Not Quite Right About Leonardo’s Mouth ~ The Rise and Rise of Cosmetically Altered Art” and “From Veronese to Turner, Celebrating Restoration-Wrecked Pictures”.

“SCRUBBED UP”

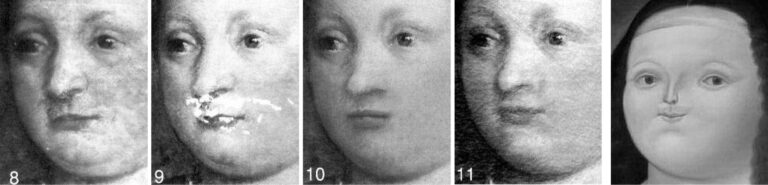

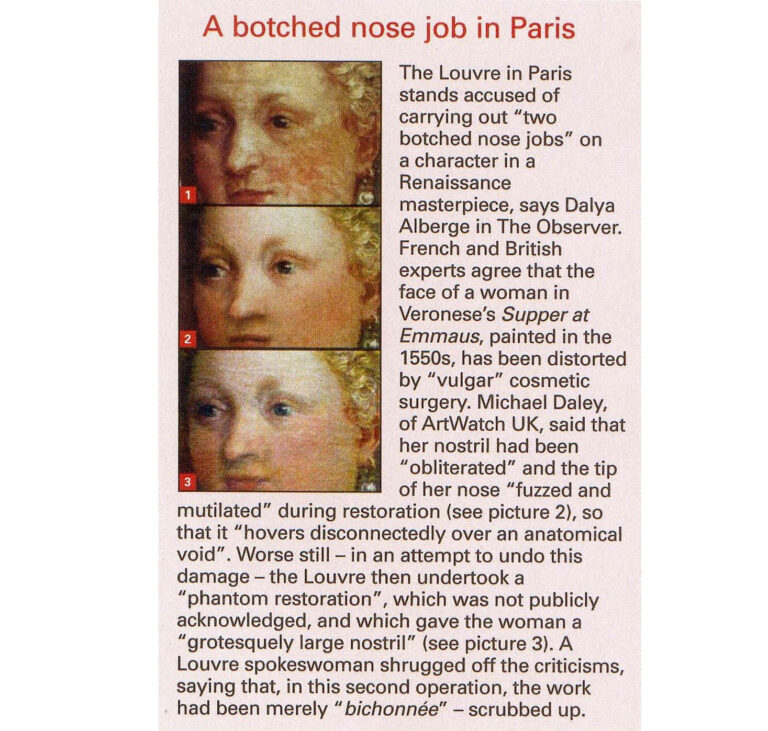

Above, Fig. 7: In the above Assorted-Mistreatments-of-a-Veronese-Face-at-the-Louvre, no. 8 shows the face before cleaning; no. 9 the face after cleaning and before restoration; no. 10 the face after cleaning and after restoration. That outcome was widely condemned and ridiculed: “A spectacular restoration own-goal…”. In response, the Louvre re-restored the face in an undocumented covert operation that spawned the fatter-lipped, sharper-nosed and more lopsided-mouth version seen at no. 11, thereby re-igniting the controversy – as was reported below at Fig. 8. Yet again, the restorers imposed a modernist aspect (as above right) by echoing Botero’s pufferfish-like spoof Mona Lisa.

Above, Fig. 8: The UK news magazine, The Week carried the above condensed report on the controversy.

DOUBLE WHAMMY

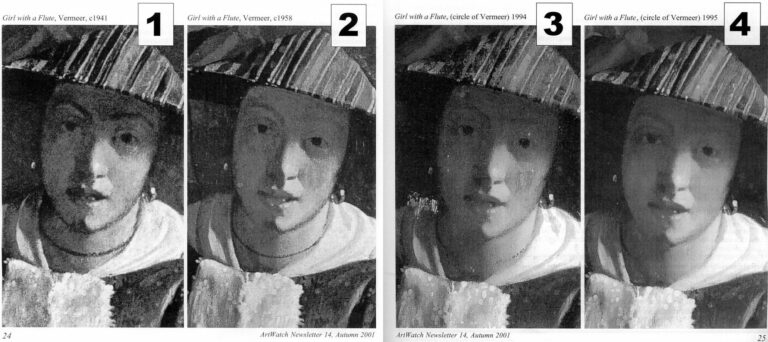

Above, Fig. 9: A former – implausibly – attributed Vermeer portrait, as seen after two modern restorations. In the first (at nos. 1 and 2), a great loss of material and shading occurred; an eyebrow disappeared; and the necklace was substantially thinned. After the next cleaning (nos. 3 and 4), the restorer lost the central section of the necklace and painted-out the surviving remnant on the right to minimise the glaring injury. The restorer also painted out an earlier striped disfigurement on the sitter’s left cheek, which action left the lit side of the face flatter and less tonally modulated than in 1941. When exhibited in a major Vermeer anniversary exhibition, no Vermeer scholar commented on its cumulative losses and alterations. The two dark stripes on the right-hand, lit side of the hat, as seen above left at no. 1, have disappeared. No one seems to have asked what kind of a striped fabric might have presented a series of parallel stripes when affixed to a cone-shaped hat.

WHAT COMES OFF IN CLEANINGS

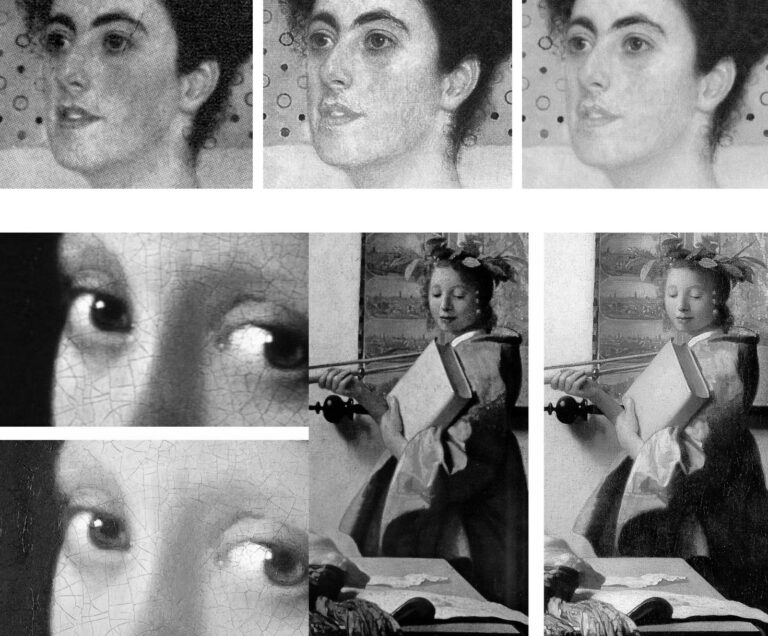

Above, Fig. 10: Top, a detail of Klimt’s 1905 Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein after successive cleanings; above, two published before- and after-cleaning details of two important Vermeer paintings showing the small- and large-scale losses of value that routinely occur when pictures are cleaned with swabs and solvents. Note, in Vermeer’s portrayal of the artist’s muse (on the right) how the weakened shading in the face and the formerly relieving darker tones of the map behind the lit side of the face, again imparted a mask-like quality to a plastically weakened head.

PSEUDO-SCIENTIFIC CONCEITS AND CONVENIENT UNTRUTHS

Where scholars might once have protested such losses as those shown between Figs. 3 – 10, they increasingly hail newly lighter, brighter, and compressed relationships of tonal value as if on a conviction that an overall cleanliness is next to godliness. For their part, restorers take any natural ageing in a varnish as an alien disfigurement that licenses a full-scale and “investigative” restoration. When artists, the makers of art, object to restoration injuries and falsifications, they are dismissed as subjective, sentimental, unscientific. The late Head Restorer and co-director of the Sistine Chapel restorations, Gianluigi Colalucci, (who had not done well at school and who had had no art training) boasted in 1986 that:

“restoration has become a fully-fledged discipline with a strong philosophical basis eliminating all subjective and arbitrary elements and a precise technical and scientific approach formulation eliminating trial and error.”

In contrast with such naïve pseudo-scientific conceit, during a controversy over paintings secretly cleaned by the National Gallery in the Second World War, Laura Knight, speaking on the authority of hands-on knowledge of the craft of painting (much as Degas and Delacroix had done in earlier controversies at the Louvre), protested in a letter to the Times in 1946 that:

“With the exception of direct painting, a comparatively modern method, a painter builds his pigment on to canvas or panel – always with the final effect in view. The actual surface of a picture is the picture as it leaves the artist’s hand. The varnish which finally covers the work for protection to a varying extent amalgamates with the paint underneath. Therefore, drastic cleaning – removal of the covering varnish – is bound to remove also this surface painting and should never be undertaken.”

Clearly stated artistic truths weigh little in an art conservation world where claimed scientific verifications are of immense political utility. Kenneth Clark disclosed in his 1977 memoir The Other Half that he had set up a science department at the National Gallery in the 1930s “with all the latest apparatus” because “until quite recently the cleaning of pictures used to arouse extraordinary public indignation, and it was therefore advisable to have in the background what purported to be scientific evidence to ‘prove’ that every precaution had been taken.”

WHAT COMES OFF IN THE WASH

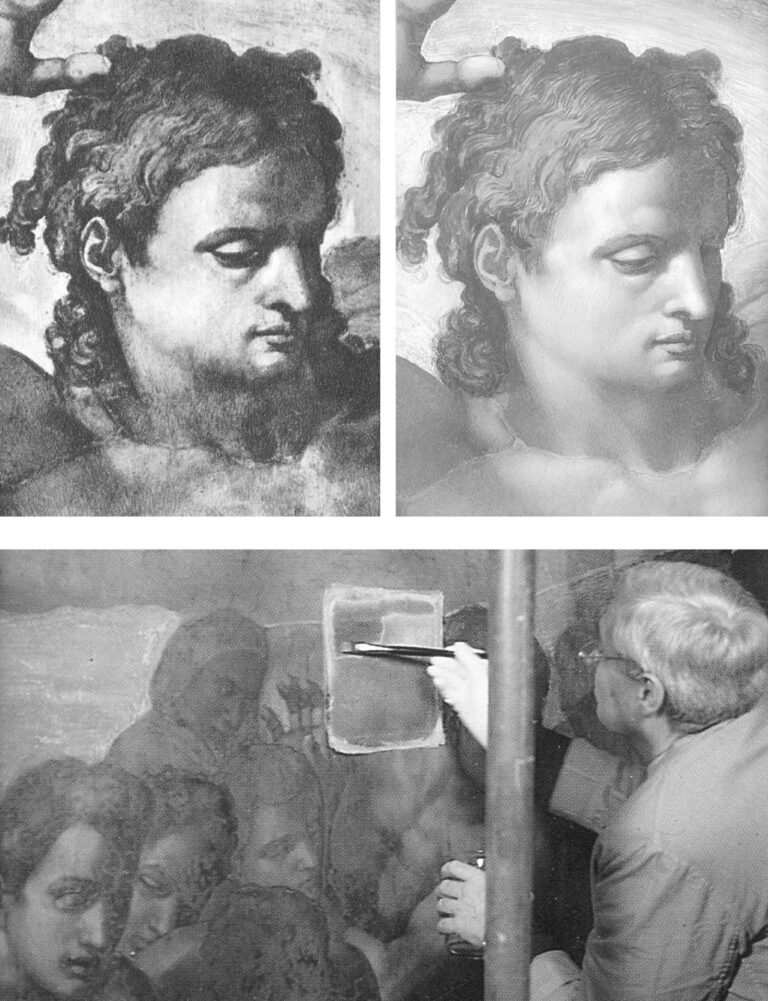

Above, Fig. 11: Top, the head of “Christ the Judge” before and after cleaning; above, Colalucci applying solvents to the Last Judgement through a paper foil.

When Colalucci cleaned the head of “Christ the Judge” (to applause from assembled restorers, one of whom filmed the event with Colalucci’s own camera, computer operators, journalists, co-director Fabrizio Mancinelli, a cleaner and the ever-present ten NTV film crew members), he applied the solvents through “a special Japanese paper” and waited for the rigidly pre-set time of fifteen minutes before removing the paper. Normally the sheets were dropped on to the floor but this time a brother restorer, Bruno Barratti, who kept a diary throughout, noted that Colalucci had “placed the sheets almost with care, crumpled though they are, in a corner of the platform.” The scaffolding cleaner whispered to the restorers as the NTV film was running “look, boys, those sheets are mine…don’t try anything on.”

If, as Colalucci maintained, his solvents had removed nothing but dirt, grease, soot and ancient glue-varnishes, the sheets would have borne no intelligible after-image. However, had he removed a secco adjustments to the head (as we believe was the case), a ghostly Turin Shroud-like image would have been captured on paper (and might still be if the sheets were not subsequently consumed by the solvents). Certainly, something was considered covetable and, as seen above at Fig. 11, the differences between the pre- and post-cleaned heads were pronounced. A photograph of those removed sheets would be of considerable evidential value today – as would be the filmed record made on Colalucci’s camera – in the absence of an official Vatican report on the restorations, which absence Colalucci attributed in 2016 to the early death in 1994 of his co-director of the restoration, Fabrizio Mancinelli, the curator of the Vatican Museums:

“This is the cause of the void created in the post-restoration studies and elsewhere. His death and the subsequent death of Pietrangeli, which was more foreseeable due to his age, led to a break in continuity of the management of the Vatican Museums that led in turn to the historic restoration being rapidly filed away as finished business.”

ART RESTORATION’S HABITUAL TECHNICAL OVER-REACHES

In the Times Educational Supplement (“As good as new?” 18 January 1991) I had written:

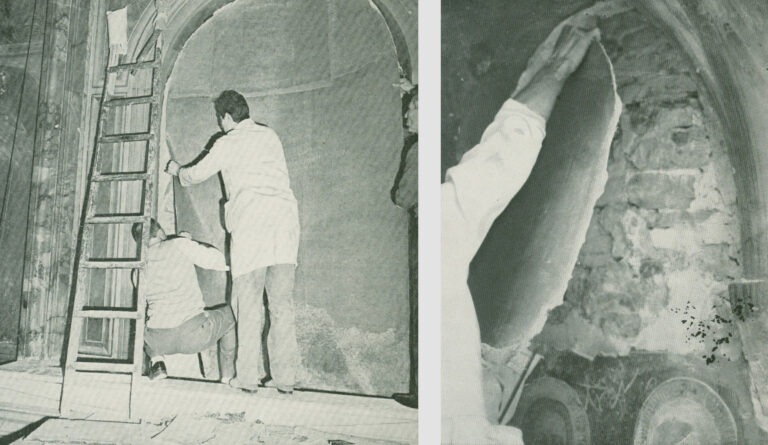

“The justification for the ultimate dismissal of artists’ expertise is that they are ‘unscientific’… [when] In matters of artistic controversy, artistic criteria must be sovereign – art operates by persuasion, not by proof. Much of the scientific validity of conservation is a sham. Conservation’s record in recent years comprises anything but a sure-footed march towards truth. In the fifties and sixties, there was a fashion, encouraged by art historians and museum curators, for removing frescoes from their surroundings, remounting them as panel pictures (thereby flattening the irregularities of the original plaster surface) and exhibiting them in museums. Much acclaimed at first, the strappo technique is now thoroughly discredited*. It damaged the walls of the buildings as well as the frescoes themselves. And, of course, it irreversibly falsified the paintings by severing them from their architectural contexts, leaving the buildings denuded and impoverished. To this day, many frescoes wrenched from their homes lie rolled unseen and unmounted in museum basements.

“A succession of cleaning solvents has been devised and used on frescoes only to be abandoned. The director of one project [the Vatican’s late Fabrizio Mancinelli, co-director with Gianluigi Colalucci of the Sistine Chapel restorations] which so damaged works of Raphael’s that they required repainting, remarked ‘what was damaged cannot be undamaged’. Frescoes recently stripped of varnish protection have been left exposed to high levels of atmospheric pollution. Synthetic resins which it was hoped offer protection have been abandoned. Air conditioning units which were also thought to be a solution are to be installed even though no one can be sure what the ideal temperature and humidity settings are and even though malfunctions by these units might result in gross damage (as happened to a major Renaissance picture being restored at the National Gallery a few years ago)…”

[* By 2003 the International Council of Monuments and Sites – ICOMOS – had warned that:

“Detachment and transfer [of frescoes] are dangerous, drastic and irreversible operations that severely affect the physical composition, material structure and aesthetic characteristics of wall paintings. These operations are, therefore, only justifiable in extreme cases when all options of in situ treatment are not viable. Should such situations occur, decisions involving detachment and transfer should always be taken by a team of professionals, rather than by the individual who is carrying out the conservation work. Detached paintings should be replaced in their original location whenever possible. Special measures should be taken for the protection and maintenance of detached paintings, and for the prevention of their theft and dispersion.”]

“OFF YOU COME!”

Above, Fig. 12: Left, “Detachment of a fresco by the strappo method.” right, “Detachment of a fresco by the stacco method.”

Both photo-illustrations above were carried in the 1968 catalogue to the Great Ages of Fresco, Giotto to Pontormo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In an introductory note on fresco techniques and their detachment from walls Professor Ugo Procacci explained the two methods:

“Stacco. The process of detaching a fresco painting from the wall by removing the pigment layer and a layer of intonaco [the final smooth thin layer of plaster which receives the artist’s painting]. Usually an animal glue is applied to the painted surface and then two layers of cloth (calico and canvas) are applied, left to dry, and later stripped off the wall, pulling the fresco with them. It is taken to a laboratory [a scientifically coercive word for a studio] where excess plaster is scraped away and another cloth is attached to its back. Finally the cloths on the face of the fresco are carefully removed. The fresco is then ready to be mounted on a new support.”

“Strappo. The process by which a fresco painting is detached when the plaster on which it is painted is greatly deteriorated. Strappo is the process of ripping off only the colour layer without removing excessive amounts of plaster. It is effected by the use of a glue considerably stronger than that used in the stacco technique. The procedure which follows is identical with that in the stacco operation. It should be noted, however, that after certain frescoes are removed by means of strappo, a coloured imprint may still be seen on the plaster remaining on the wall. This is evidence of the depth to which the pigment penetrated the plaster. These traces of colour are often removed by a second strappo operation on the same wall.”

CHEMICALLY-STRIPPING FRESCOES: 1) THE SISTINE CHAPEL

There are many dis-proofs of Colalucci’s claim that only soot and earlier restorers’ discoloured glue-varnishes were removed from the Sistine Chapel ceiling. To cite one: the loss of artistic values that had been recorded by copyists both in Michelangelo’s own lifetime and for centuries afterwards – as with Giorgio Ghisi’s engraving below of c. 1570, which was thus made long before any restorers had worked on the ceiling.

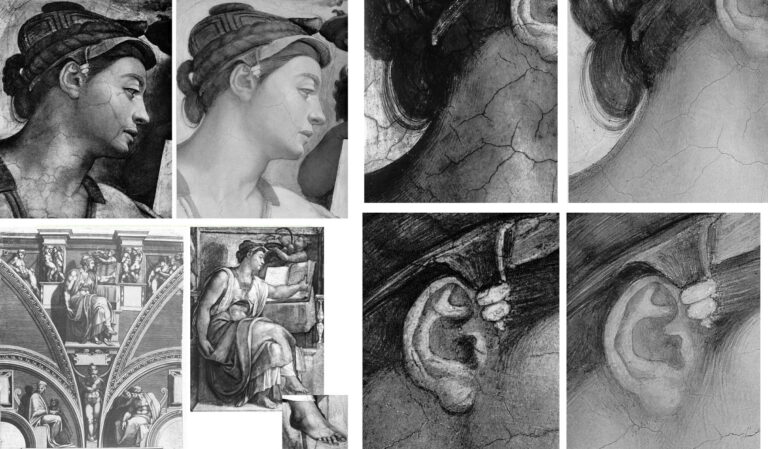

Above, Fig. 13: Top and right, details of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling figure the Erythraean Sibyl, before and after the cleaning in which, for example, relieving shading to the right of the face’s profile was stripped away, as was internal shading on the head and neck. It was always beyond inconceivable that any naturally accruing films like soot could have organised themselves to reinforce the modelling within the contours of Michelangelo’s figures.

CHEMICALLY-STRIPPING FRESCOES: 2) THE BRANCACCI CHAPEL

“The history of restoration clearly shows that with the passage of time, nearly all restorations have proven to be negative…We cannot be certain that the work we’ve done here [at the Brancacci chapel] has been positive.”

So said one of the Brancacci Chapel restorers, Marcello Chemeri, in an interview carried in Ken Shulman’s invaluable 1991 book on the Olivetti-sponsored restoration, Anatomy of a Restoration – The Brancacci Chapel. “Invaluable” because although Shulman was generally parti pris with the restorations of both the Sistine and the Brancacci chapels, he drew out full first-hand accounts from the key Brancacci players – and, also, most unusually, from across the board in their assembled team – as with Chemeri.

Thus, we learned from Shulman that Chemeri had hoped to be a painter from his early teens; that he still painted in his spare time; that as a boy he was always drawing or experimenting with colours; that he had [only] gone into restoration because he needed a job when he left art school. That he had been reluctant to give an interview. From another restorer, reluctant even to be identified, we were urged:

“Let’s be honest and admit what all restoration directors will say in private. At the beginning of any restoration, you order as many tests as you can imagine, fully aware that only about five per cent of them will be of any use during the project. The rest of them are merely window dressing.”

Shulman further explained that:

“This competition among historians to link their names to a specific method or restoration is both inevitable and understandable. With the meagre monetary remuneration usually afforded to historians and restorers, restoration professionals are usually left to vie for the various badges of merit and prestige. The Brancacci Chapel was the most prestigious jewel in the block – perhaps even more prestigious than the concurrent Sistine Chapel restoration because of the mystery surrounding the Brancacci and its history – and Baldini had it in his pocket. There were many interests involved here – the enormous artistic importance of the work, the contention between Florence and Rome, the jostling among scientists, industry, and government for the honour of participating in the project, and Baldini’s own noted ambition. Given all these, it was unthinkable that Baldini would allow the long-awaited restoration to deteriorate in the public eye into what might appear an unglamorous, methodical, albeit thoroughly effective cleaning.”

EXTREME AESTHETIC CLEANSING:

Chemeri, the most artist-like of the Brancacci restorers, had put his finger on the nub of the problem with both of the period’s major and controversial fresco restorations – which is to say, on the unwavering absolutist assertion that the original artist authors of the Brancacci and the Sistina murals had entirely confined their work to painting directly into the plaster while wet and had not made any revisions or embellishments with a secco painting. As will be shown, the restorers in both chapels had – wittingly or unwittingly – demonstrably misdiagnosed the material which they removed entirely and to artistically disastrous effects. Had they fully acknowledged and correctly addressed the known histories and circumstances of both chapels’ frescoes, the complexity and subtlety of their tasks would have leapt exponentially, and every inch of the cleaning would have been dependent on more problematically (for restorers) aesthetic and artistic appraisals and not on the proffered simplistic “brush it in on, wait a bit, wash it off” chemical solution procedures.

A PHOTO-COMPARISON WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS

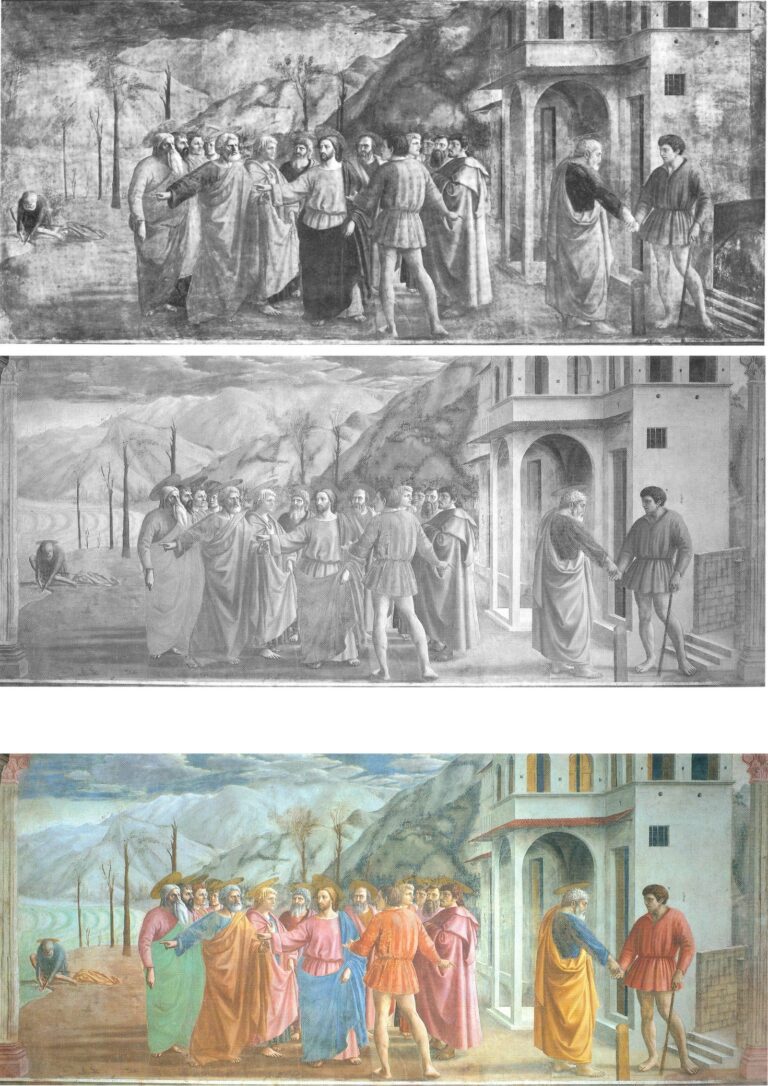

Here, a single before and after- greyscale photo-comparison will suffice, as below at Fig. 14, to demonstrate the artistic debilitation of Masaccio’s work:

Above, Fig. 14: Top, Masaccio’s wall scene, “The Tribute Money”, as published in the 1981 edition of the 1968 Masaccio (in the series L’opera complete di); centre, the same scene after restoration, as published in the 1992 edition English-language edition of The Brancacci Chapel Frescoes by Umberto Baldini and Ornella Casazza; above, the post-restoration scene in colour and before the conversion into greyscale shown above it.

The above photo-comparisons show precisely how the Brancacci Chapel restoration had damaged Masaccio’s then-revolutionary painting. As with the Sistine Chapel ceiling, it does so on the restorers’ own accounts: if the paintings really had simply been obscured by centuries-worth of filth, decaying restorations, decaying varnishes and such, then, on the laws of optics, at their removal by the restorers, the visual values and relationships that previously had been evident through the dimming and obscuring film would have emerged with hugely increased vivacity – the darks would be darker and the lights lighter; the tonal relationships would span greater ranges and so on. Instead, after stripping the frescoes of all supposedly alien “accretions” the painting emerged a pale shadow of its former supposedly badly obscured but in truth greatly more vivacious earlier self. How could that be? Why should the removal of a disfiguring film of organic material have reduced the aerial depths and space, the tonal dynamism, the previously legendary sculptural corporeality of the figures and their dramatically orchestrated narrative lucidity?

The restorers, content with their new, all-on-the-picture-surface litter of clean pastel-ised colours, made no attempt to explain the phenomenon. They declined, even, to offer direct photographic comparisons of the pre- and post-cleaning states despite having boasted of “investigating” the murals with every conceivable type of photography – viz: “1) photographic documentation using direct lighting before the restoration of the frescoed sections; 2) photographic documentation using close lighting before the restoration of the frescoed sections; 3) examination of ultraviolet fluorescence…”

In a sponsor’s note to the 1992 book on the restoration, Carlo De Benedetti, President of the Olivetti Corporation (the sponsors of the travelling fresco exhibitions), said it would be followed by a second book “containing the documentation of the analyses, studies and technical and scientific operational interventions in preparation for and during the course of the work…” So far as we know, that promised second volume – like the report on the Sistine Chapel restorations – never materialised. A condensed version of the 1992 book issued as The Brancacci Chapel in the Electa Art Guides series, carried a note on the “The Restoration: Research and Method”. It listed no fewer than fifteen methods of investigation from “photographic documentation” (1) to “designing a system to continually de-pollute the interior in ‘real time’ so as to prevent the arrival of harmful agents in the chapel’s atmosphere, especially when visitors are present” (15). Number 14 laid bare the methodological heart of the restoration’s core purpose, by seeking the:

“…development of an appropriate cleaning technique which did not alter the pigments or the surface of the frescoes in any way while chemically removing the traces of organic substances, including the residues of earlier attempts at restoration…” (Emphasis added.)

The conceptual and methodological flaws in this restoration slip out: if the frescoes, as liberated by Baldini/Casazza, have survived intact, why would earlier restorers have needed to restore them? However, if Masaccio had embellished and completed his work with a secco painting on the plaster surface, such overlaid painting would have been susceptible to decay or injury through cleaning…and therefore more likely to have been repaired or replaced by restorers. The so-called “traces” were more frequently disparagingly described as “beverone” – a veritable soup of organic material found to be comprised of egg or animal glues, both of which are well-known binders for pigments. As Shulman put it, an earlier painter/restorer called Sacconi was said to have “basted the surface of the frescoes with an egg-based protective layer which also gave the paintings a temporary transparent clarity.”

The overall assertion of absolute safety and confidence in the entirely extraneous and alien nature of everything that lay on the fresco surface was precisely that of the Vatican’s team. In 1988 Colalucci told Shulman that his cleaning technique on the ceiling:

“cannot harm the materials used in fresco, as the chemicals in the AB57 solution only react with organic matter. All we are removing are the layers of glue and wine and dust which have accumulated over the centuries.”

Like Baldini/Casazza, Colalucci appealed to the authority of “preliminary” technical analysis but, in his case, the supposedly decisive analysis had been undertaken only “on the Eleazar and Mathan lunette” at the conclusion of which, it was claimed, “Michelangelo’s use of buon fresco was unequivocably vindicated” throughout the lunettes and the (then unexamined) ceiling.

Thus, both sets of restorers had felt licensed by their own research to undertake the most profoundly radical “conservation” measures by stripping everything off the surfaces of fresco cycles that were, respectively five and a half, and more than four and half centuries old – and all of this techno-buccaneering took place as the earlier fresco-stripping infatuation (in which key restorers in Florence played most prominent roles, as shown below) had fallen into disrepute.

THE FRESCO-STRIPPING MANIA

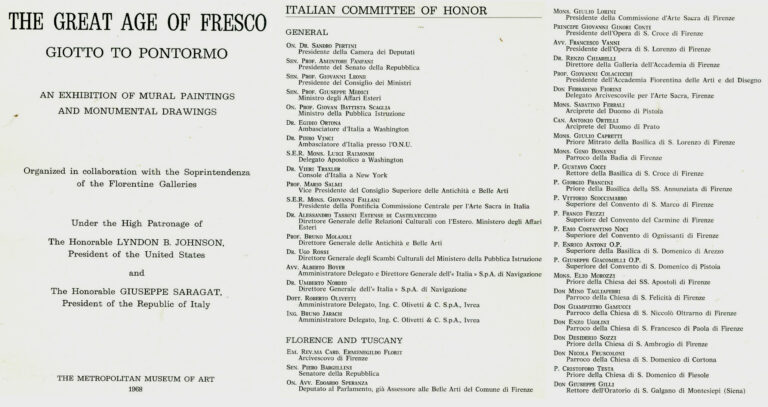

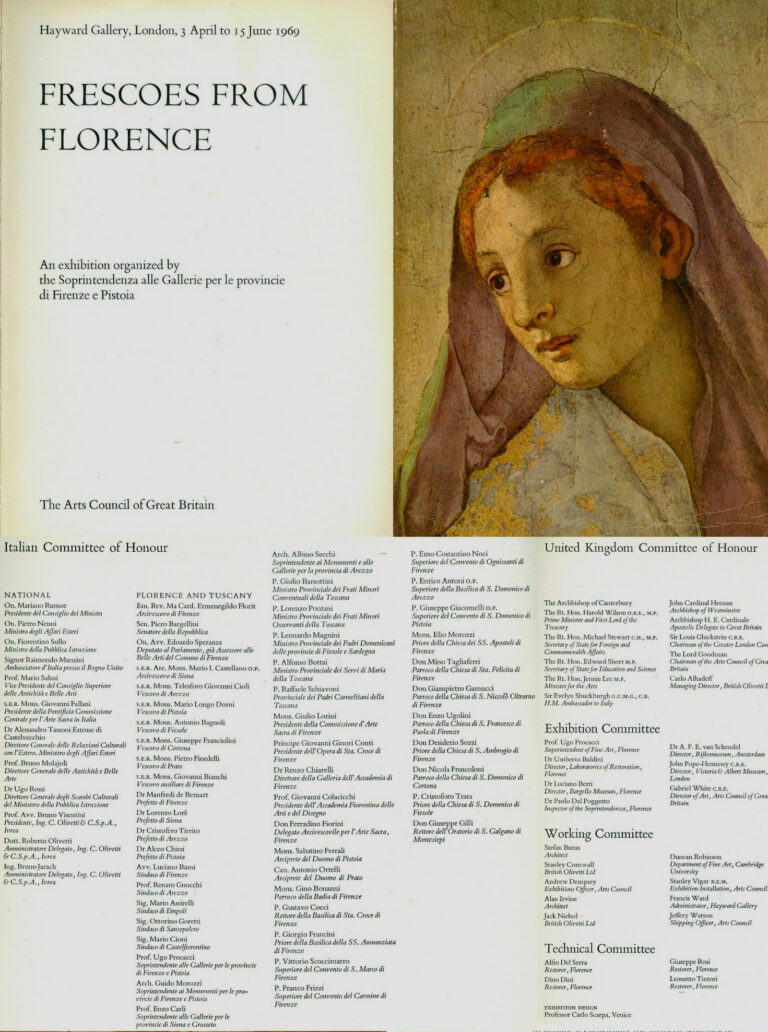

The Great Travelling Fresco Exhibitions – the 1968-69 “The Great Age of Fresco – Giotto to Pontormo” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Rijksmuseum, and the 1969 “Frescoes from Florence” exhibition at the Arts Council’s Hayward Gallery, London – had, like the Sistine Chapel restorations, attracted enthusiastic groupthink support among the highest art historical echelons. That support was trumpeted in the catalogues’ inflated “Committees-of-Honour” lists shown below at Figs. 15 to 18. In the herd-like stampede to strip, no thought was given to the risks and long-term consequences of detachment or, indeed, to the risks of sending them on tours.

Seventy of “the finest fresco paintings from Tuscany” were transported across the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean to New York in a single ship, the Cristofo Columbus – much as Mussolini had dispatched Italy’s greatest art treasures forty years earlier on the SS Leonardo da Vinci, with a back-up tug, in December 1929 from Genoa to London via a storm, in which ships were lost, off Cape Finisterre, Spain, to the legendary 1930 Royal Academy Italian Art show. The detached Tuscan frescoes show in New York was hubristically hailed:

“Birnham Wood has come to Dunsinane. What was rooted in Florence, what was bound to the walls of churches and town halls, has been freed by newly refined techniques and brought to New York for display in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

A FLAGSHIP MODERN CONSERVATION CAMPAIGN’S “PRACTICALLY NEGLIBLE” LOSSES…

Lavish credit was conferred in the catalogue:

“Almost all the sinopia (or preparatory drawings in red earth), concealed by the overlying frescoes since they were made, have been uncovered in the great modern campaign to conserve the surviving examples of this art. The campaign has been led with extraordinary knowledge and enthusiasm by Professor Ugo Procacci, aided in recent years by Professor Umberto Baldini, and it has been conducted with consummate skill by the specialists Leonetto Tintori, Dino Dini, Giuseppe Rossi and Alfio Del Serra*. These men have so refined the techniques of detachment that the loss to the fresco and underlying sinopia is practically neglible.”

A restorer at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, has claimed there is a working professional concept of “acceptable potential loss” with loaned museum works – see “Protecting the Burrell Collection ~ A Blast against Risk-Deniers”.

[* Baldini, Alfio Del Serra, and Tintori would later formally underwrite Colalucci’s treatments of the Sistine Ceiling but, on Tintori’s contrary, privately expressed views and withheld minority report, see “Rocking the Louvre: the Bergeon Langle Disclosures on Leonardo da Vinci” – viz:

“Without knowledge of Tintori’s highly expert dissenting professional testimony, the public was assured that despite intense and widespread opposition the cleaning had received unanimous expert endorsement. Critics of the restoration were left prey to disparagement and even vilification.”]

In his 2016 memoir Michelangelo and I – Facts, People, Surprises and Discoveries, Colalucci listed the membership of two invigilating committees set up under the jurisdictions of the Vatican and the Kress Foundation – the latter being administered by Professor Kathleen Weil-Garris Brandt, of New York University, who became a spokesman for the Sistine Chapel restorations and moved to Rome for a year to organise a celebratory exhibition and conference on the completion of restoration of the ceiling and the studies for the Last Judgement restoration. The membership of these bodies of scholars, restorers and scientists comprised:

André Chastel; Sidney J. Freedberg; Carlo Bertelli (the initiator of the 1977- 1999 re-restoration of Leonardo’s Last Supper which had been executed only twenty-three years earlier in 1947-1954 and to acclaim from Bernard Berenson); Pierluigi De Vecchi; Giovanni Urbani; Luitpold Frommel; Matthias Winner; Umberto Baldini; Michael Hirst; John Shearman; Kathleen Weil Garris Brandt; Alfio Del Serra; Paul Schwartzbaum; Norbert Baer; Mario Modestini; John Brealey; Dianne Dwyer (then Brealey’s assistant at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, who later married Mario Modestini and famously repainted and artificially distressed much of the $450million Leonardo school Salvator Mundi); Andrea Rothe; David Bull; and Leonetto Tintori.

THE GREAT, THE GOOD AND THE SPONSOR

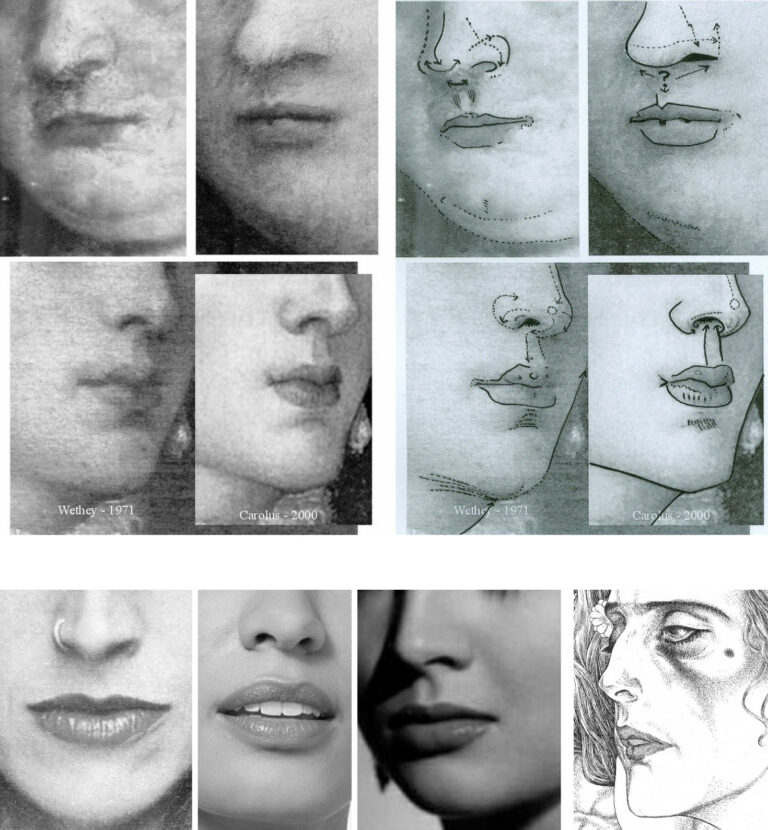

Above, Figs. 15 to 18, showing the committees of honour who had endorsed the stripping of frescoes from walls.

INSATIABLE, RISKY APPETITES FOR TRAVELLING ART LOANS

In 2014 the Metropolitan Museum mounted an exhibition of six entire windows removed from Canterbury Cathedral (in the course of “restoration”). See “How the Metropolitan Museum of Art Gets hold of the world’s most precious and vulnerable treasures”.

In 2016 we reported that, as with Canterbury, plans were underway to fly restored windows at Chartres Cathedral to the United States: “Chartres’ Flying Windows”. (In the event, and following interrogation from Florence Hallett, author of the post, the authorities decided that the risks were not worth taking and the windows stayed in France.)

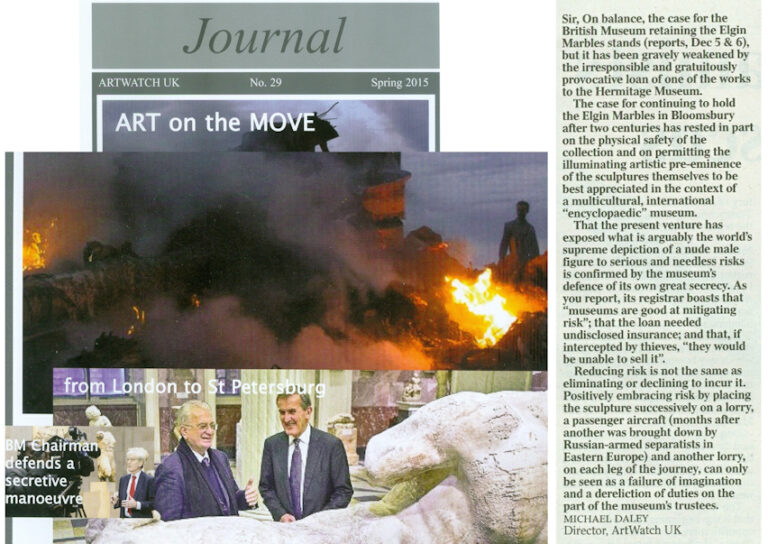

Most inexplicably of all (as reported in the ArtWatch UK Journal No. 29), in December 2014 the British Museum’s Courtauld Institute-trained director, Neil MacGregor, had gratuitously conferred a museological vote of confidence in Putin’s Russia by recklessly – and, to Greece, provocatively – sending one of the most precious Parthenon sculptures on a roundabout route that avoided EU airspace to the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. The flights occurred just months after Russian troops had annexed part of Ukraine and Russian-armed separatists in eastern Ukraine had brought down a Malaysian Airlines Boeing with a loss of 298 lives including around 100 children. The British Museum loan, which enjoyed no conservation pretext and which replicated the Hermitage’s own fine early plaster cast of the sculpture made by Lord Elgin, was conducted in an act of secrecy that blindsided the UK Government at a time when economic sanctions had been imposed on Russia in response to its annexation of Crimea.

Above, Fig. 19: The cover of the ArtWatch UK Journal No. 29, Spring 2015 showing the directors of the Hermitage and the British Museum, Mikhail Piotrovsky and Neil MacGregor; right, ArtWatch UK Letter, The Times, 9 December 2014.

THE SISTINA RESTORATION’S COSTS AND CONSEQUENCES

In his highly informative exhibition catalogue essay to the Tuscan Frescoes exhibitions, Professor Ugo Procacci set the “great mural paintings of golden age of Italian paintings” from Cimabue to Michelangelo as an interval of “true frescoes”. That common but misleading characterisation of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel painting methods served as cover for the Sistine Chapel restorers’ overall applications of the oven-cleaner-like new agent AB57 which had been designed to remove pollution-encrusted salt efflorescence from marble and not for removing a secco paint or supposed glue-varnishes. It made mincemeat of the Sistine Chapel frescoes’ highly distinctive a secco features, including those shown above which had been copied by Michelangelo’s contemporaries and by subsequent artists for centuries thereafter. Procacci and Baldini had shared Colalucci’s and Mancinelli’s desire to intensify chromatic values by making a complete removal of all material on the plaster fresco surfaces of the Brancacci Chapel. In both cases this radical aesthetic cleansing subverted the “sculptural” and “aerial” roles that tonal relationships had played within the two artists’ famous murals as shown above at Figs. 13 and 14 above.

CAUGHT ON THE HOP AND IN THE ACT

Above, Fig. 20: National Geographic’s iconic photo-record of the Sistine Chapel ceiling showing the last moments of the unrestored and most brilliant final stages of Michelangelo’s ceiling painting – which included his acclaimed portrayals of the Crucifixion of Haman, the Prophet Jonah and the Libyan Sibyl, all set in their deep and darkened spatial dramas within the forcefully articulating projections of Michelangelo’s fictive architecture.

To preserve a lucrative Vatican revenue stream from paying visitors, the chapel remained open throughout the restoration but at the cost and consequence of enabling viewers to see and compare the cleaned and not-yet-cleaned frescoes simultaneously – as above at Fig. 20. That unprecedented directly comparative opportunity drew instant criticisms and forged an unusually strong alliance of artist/critics and scholar/critics. When the art historical establishment looked the other way as Beck, a leading Renaissance scholar/critic, was put at very great personal and professional risk in the Italian courts for his critical view on the restoration of a sculpture by the artist on whom he was the world authority – and on which particular sculpture he had written a commemorative book (Fig. 22) – immense media and publishing interest was aroused. That in turn lead to the publication of the 1993 and 1996 James Beck, Michael Daley, book Art Restoration: The Culture, the Business and the Scandal.

THE SHARPENING OF HOSTILITIES AND DENIALS OF EVIDENCE

Above, Fig. 21: Above, an article carried in the 22 November 1991 Independent when Professor James Beck had been acquitted of criminal slander charges brought by the restorer of Jacopo Della Quercia’s marble Illaria del Carretto tomb monument in Lucca’s Duomo (Fig. 22); right, the 1993, London, and 1996, New York, editions of Art Restoration, The Culture, the Business and the Scandal.

PRAISE, WHERE DUE…

Above, Fig. 22: Top left, the 1988 James Beck and Aurelio Amendola book ILARIA DEL CARRETTO di Jacopo Della Quercia; top right, the 1993 book Michelangelo: The Medici Chapel by James Beck, Antonio Paolucci, Bruno Santi – and with notes on the chapel’s restoration by the restorers Agnese Parronchi and Francesco Panichi; above, the team of restorers who spent eight years between 2013 and 2021 re-restoring the Medici Chapel with a “top secret” bacteria-infused gel, as reported in the Guardian and the New York Times (Photo. by Gianni Cipriano.)

In Art Restoration Beck had noted that while nothing was more demoralizing than being obliged to respond negatively to the vast majority of restorations, there had happily been some notable successes:

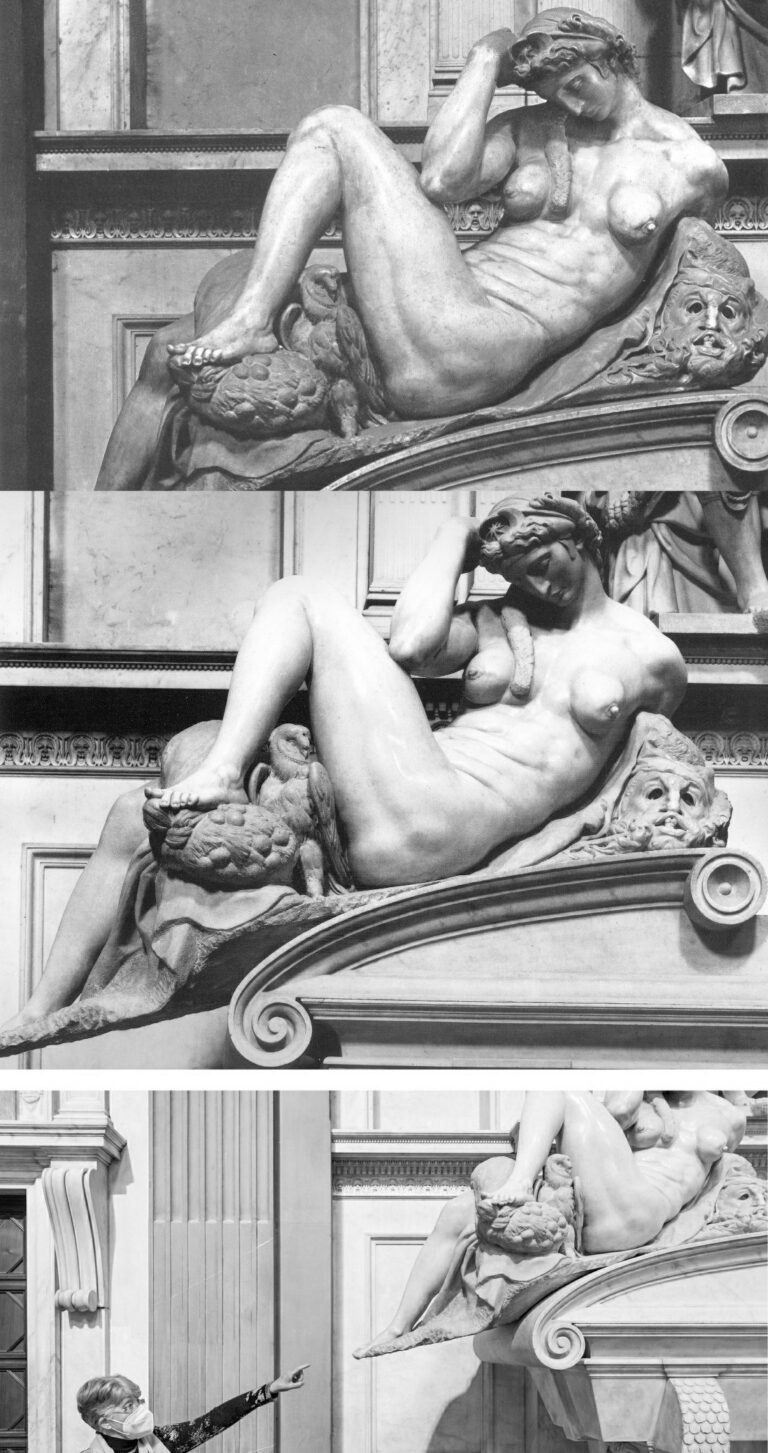

“The cleaning of Michelangelo’s sculpture for the Medici tombs in the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo, in Florence, was completed in mid-1991, and it was done with noteworthy sensitivity. Since the work was executed more or less at the same time as the Ilaria and since both were of fine-quality marble, I am enormously relieved to be able to speak enthusiastically about it. What is extraordinary about the cleaning which, again like the Ilaria, involved sculpture that was housed indoors, was that no harsh chemicals were used, no mechanical means employed, no oil applied to the surface. The dust and the dirt were gently removed with cotton wads and distilled water. What is more, the cleaning was conducted by an artistically oriented and enlightened young woman, Agnese Parronchi, who had trained a decade earlier at the Opificio. The money was supplied by a private sponsor, a foundation whose director showed the deepest respect for the works of art, while the superintendent in charge was extremely well-informed and co-operative. In other words, this restoration, together with one by the same restorer conducted on Michelangelo’s Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs relief located in the Casa Buonarroti, has provided encouraging proof that sensitive cleanings are indeed possible.”

That optimistic note was carried in both the 1993 and 1996 editions of Art Restoration. Perhaps Beck’s approval was considered a provocation by the restoration establishment. Perhaps with a change of superintendent in 1992 it was soon forgotten that the chapel had been restored to acclaim. Perhaps new donors presented themselves. In any event, as the New York Times recently splashed:

“Send in the Bugs. The Michelangelos Need Cleaning.

“Last fall, with the Medici Chapel in Florence operating on reduced hours because of Covid-19, scientists and restorers completed a secret experiment: They unleashed grime-eating bacteria on the artist’s masterpiece marbles…Nearly a decade of restorations removed most of the blemishes…In November 2019, the museum brought in Italy’s National Research Council, which used infrared spectroscopy that revealed calcite, silicate and other more organic, remnants on the sculptures and two tombs that face one another across the New Sacristy. That provided a key blueprint for Anna Rosa Sprocati, a biologist at the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, to choose the most appropriate bacteria from a collection of nearly 1000 strains, usually used to break down petroleum in oil spills or to reduce the toxity of heavy metals. Some of the bugs in her lab ate phosphates and proteins, but also the Carrara marble preferred by Michelangelo. ‘We didn’t pick those’, said Bietti…”

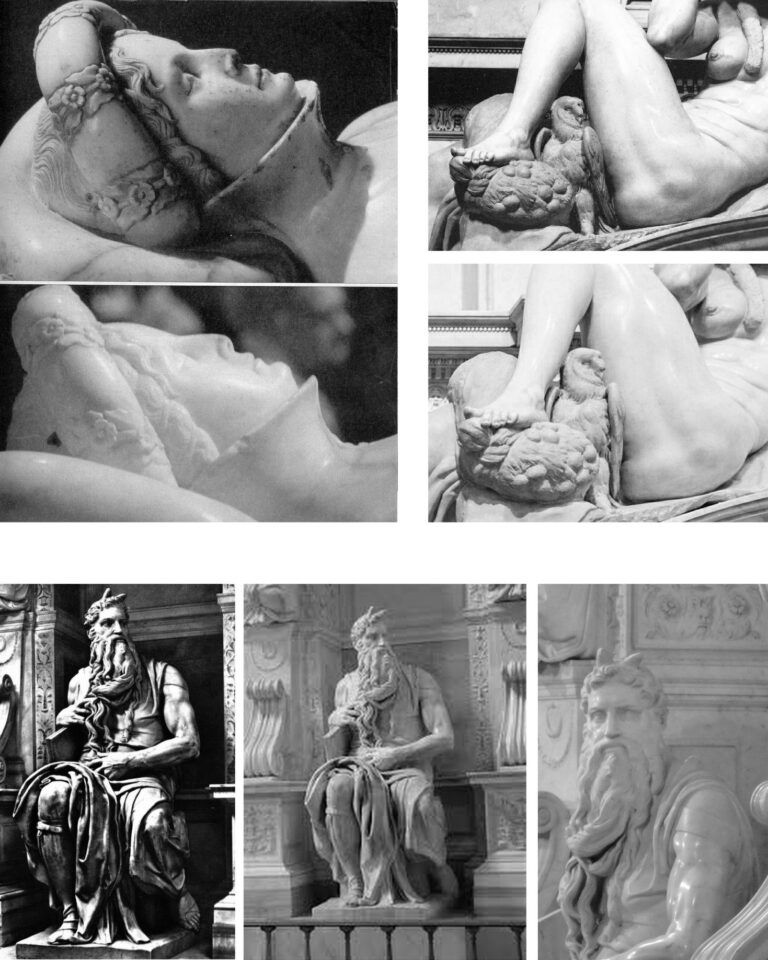

Above, Fig. 23: Michelangelo’s Medici Chapel portrayal of Night as respectively seen in: (top) the 1986 edition of Ludwig Goldscheider’s Michelangelo: Paintings, Sculpture, Architecture; (centre) the 1993 Michelangelo: The Medici Chapel by James Beck, Antonio Paolucci, Bruno Santi; (above) in recent press reports. The interval between the two last and prolonged restorations had barely been two decades. As can be seen above, the figure of Night is greatly more highly polished and the former pronounced tonal difference between the figure and its supporting accoutrements – the owl, the mask, draperies – has been greratly diminished.

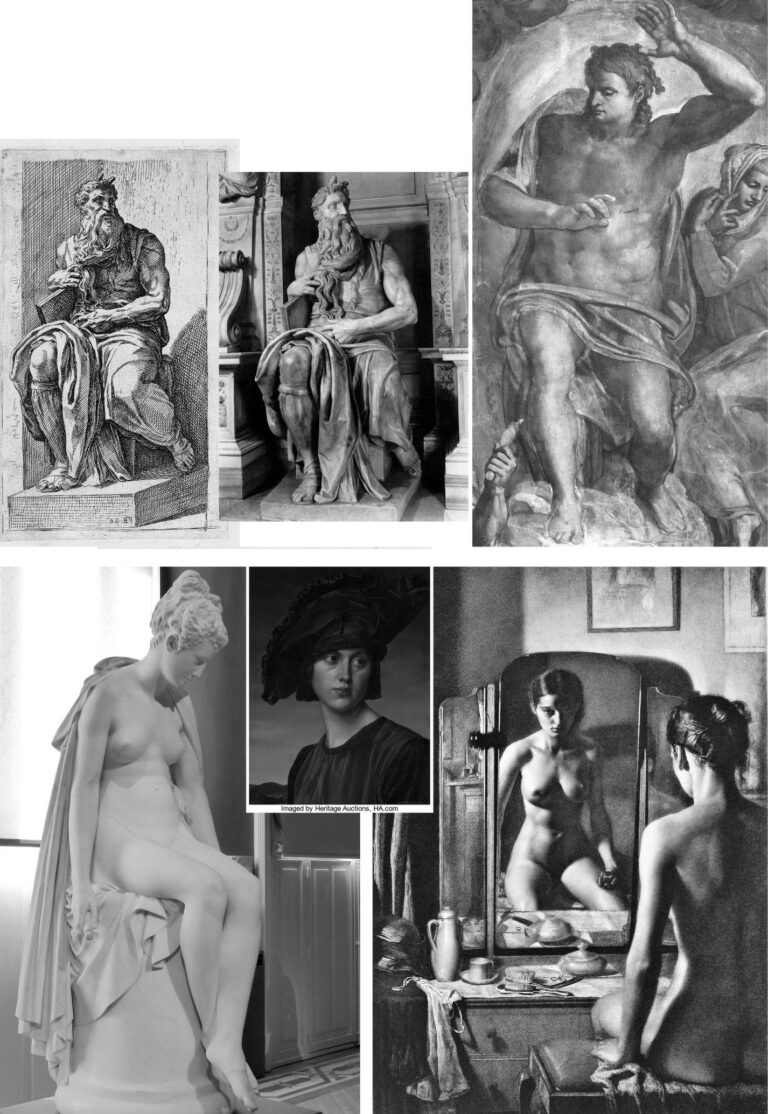

Above, Fig. 24: Top left, the head of Jacopo Della Quercia’s Ilaria del Carretto Tomb Monument, as seen before and after its last restoration; top right, a detail of Michelangelo’s Night as seen in 1993 and today; above, Michelangelo’s carving Moses in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, as seen (left) in an old post card and (right) after a restoration that began in 2001 and that was jointly funded by the firm Lottomatica and the Italian Ministry of Culture.

The gambling company Lottomatica was acquired for over a billion euros in 2021 by the Gamenet Group. A webcam was set up at the church in Vincoli to broadcast the restoration process in real time. The restoration itself thus became part of a multimedia event which included a series of photographs by the German photographer Helmut Newton and a concert by the British composer Michael Nyman. The restorer, Antonio Forcellino, fairly acknowledged that the sculpture “will never be as it was when Michelangelo made it” and that to take out the stains made when replicas were made from the carving was so risky that “we’ll limit ourselves to lower the tone of the stains themselves.” Nonetheless, the push towards a perfectly white shininess that hinders appraisals of sculptural forms and makes old stone resemble new plastic, had made a quantum leap.

FORM: ITS REALISATIONS, ITS FINISHES AND ITS READINGS

Above, Fig. 25: Top, left, an etching of 1638 by Franҫois Perrier after Michelangelo’s Moses; top, centre, Moses before its last restoration; top, right, Michelangelo’s “Christ the Judge” (mirrored); above, left, a marble carving of Psyche by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse; above, centre, a portrait by Gerald Brockhurst; above, right, Brockhurst’s etching The Artist and the Muse.

Before it becomes a thing, sculpture is an idea. Ideas can be given verbal, written, graphic, pictorial or plastic – or other – expression. A sculptural idea can be realised as a piece of sculpture – at which point it becomes a real thing-in-the-world and is subjected to any number and direction of external light sources – or, it can be given expression in graphic or pictorial form. Ideas realised as things i. e., as sculptures, are bounded by their surfaces, unlike graphic or pictorial works in which sculptural ideas find expression as depictions-on-surfaces. Although a sculptural idea expressed pictorially is generally confined to a form as perceived from a single position (as in the Brockhurst etching above – albeit where a craftily deployed mirror affords a second viewpoint) the image can carry implicit suggestions of how objects would appear from a different viewpoint. But it is never possible (not even for Picasso in full cubist mode) for a depiction to match the infinite multiplicity of indivisibly linked aspects that a given sculpture presents to a viewer when seen “in the flesh” and “in the round”. The great drawback with sculpture is that it is much slower to make and finish a thing than to depict one. When Michelangelo was compelled to stop making the figures he had planned to join his Moses he executed over three hundred figures on the Sistine ceiling alone including his suite of monumental seated Prophets and Sibyls. His “Christ the Judge” deployed every ounce of sculptural know-how but with the advantage of containing its own optimalised light-source to maximise by the play of its lights, darks and in-betweens, the greatest possible plastic vivacity.

The surface “finish” of a sculpture is an intrinsically problematic notion and an aspect of sculptural practice which is subject to personal and/or cultural preferences as well as to the nature of (sometimes) stipulated materials of construction.

A sculpture made with clay (which needs to be kept moist while being worked) will have a pleasant sheen which results in highlights and gradated shadows as the surfaces of forms turn away from the light source. If the clay is kept hollow and allowed to dry out completely, the sculpture can be fired in a kiln to varying degrees of hardness and finish, but it will emerge with a matt light-absorbing surface which most sculptors find unsatisfactory and visually deadening. If the clay sculpture is supported by an armature, it will not be able to dry out without cracking. In such cases, to preserve the form, the clay must either be kept wet indefinitely, or a “negative” cast be made from it with fine plaster. That plaster cast negative surface (the mould) can then be filled with other substances but, most commonly, this would be with reinforced plaster. The outer original cast mould can then be chiselled away to expose a hard durable positive facsimile of the originally modelled soft and wet clay. The initial surfaces of plaster casts, however, are also matt and sculpturally deadening in their highly light-absorbing capacities. Sculptors can go to considerable and resourceful lengths to work up a desired degree and nature of surface finish. There is a fascinating and eloquent video here on the “restoration” of a large Henry Moore painted plaster sculpture protype for a bronze cast as it was being “prepared” for inclusion in an exhibition by being given a “re-activated” and as if freshly worked surface.

In the case of Michelangelo’s New Sacristy sculptures, the last-but-one restoration team, Parronchi and Panichi, set out the issues raised for would-be restorers by Michelangelo’s own famously varied levels of sculptural finish. The restorers first described the approach of their own programme in general terms:

“The recent restoration of Michelangelo’s marble sculptures in the New Sacristy was the first of this century. They have been superficially cleaned from time to time, but this was the first true restoration scheme. At the beginning of the programme, it appeared that the tombs and seven statues, together with those of Saints Cosmas and Damian, had been kept in almost ideal conditions. The level of relative humidity inside the Sacristy is not very high (70% approx). The light is gently filtered through large, high windows, and for most of the day the Chapel is bathed in a glowing half-light which is accentuated by the reflection from the marble surfaces, A brilliant but soft light from the lantern is diffused inside the cupola before shining down onto the tombs, which are not subject to the full glare of direct rays. The micro-climate does not vary with the seasons, but the extreme heat of summer is alleviated by the solidity of the structure. In winter the attendants have to show a certain spartan toughness.

“In spite of this, the statues had a dull appearance. They were covered with a layer of dust beneath which thicker deposits, some sticking to the substratum, were found. They were irregularly distributed over the surfaces of the statues and were found in greater or lesser concentrations according to the angle and working of the surface, and the form, outline and position of the sculpture. It was important to establish which of the many waxes found were of animal origin and therefore particularly sensitive to climatic and atmospheric influences. They also react to light as well as to relative humidity and extremes of temperature. Restoration work is justified (one should always ask whether it is really necessary) by the presence of obvious accumulations of atmospheric particles which block the surfaces, alter their precarious balance of interacting elements, and even blur them to the point where it is no longer possible to see them accurately. At this point, in order to put the case for the critics of ‘patina’, it is appropriate to try to explain how much was removed, how much was left in place, and the reasons. We shall therefore begin by describing and analysing the factors that cause an acceleration in the natural aging process, and lead inevitably to permanent deterioration in a work of art…”

The restorers’ alertness to artistic considerations of which Beck spoke was particularly evident in this passage:

“If, as art historians maintain, Michelangelo’s sculpture was born mature, it is impossible to doubt that the finish he gave to the surfaces of Night was deliberate, as was the working of Day, which is blocked out with the subbia [a pointed heavy tool] and slightly smoothed on the face with the gradina [a sharp-toothed chisel] and is a perfect example of what is known as non-finito. After the restoration of Dusk, the way in which the gradina has been used to smooth the face and create an effect of chiaroscuro between the head and the finely polished upper body, can clearly be appreciated. This technique is even more obvious on the right shin, where the lower part is smoothed, but the upper part where the light falls, is finely polished, creating an effect of both softness and movement, and light and shade. The symbolic figure of Night is the most finito, the most lustrous of Michelangelo’s seven statues. After restoration it glows with the radiance of a moonlit night, in an obvious metaphorical and tonal contrast with the other three allegorical figures which, as the restoration has revealed have a warmer and more misty colour range…

The restorers concluded with a summary of the methods adopted and the materials used in the restoration:

“Six thousand man hours, hundreds of photographs taken by us, and thousands sent in by visitors from all over the world, litres of de-ionized water, several kilograms of cotton, cottonbuds, and volatile turpentine essence. Using these materials we tried to maintain a balance between sensitivity and research, so that art would not be destroyed by science. One hundred square metres of marble surface were restored without, of course, using any waxes or protective coatings that might create new ‘patina’…We must ask ourselves, and above all ask all art historians, and everyone to whom culture matters, whether this masterpiece bequeathed to us by the artist will survive the overweening attentions of the high priests of gleaming whiteness; whether this accumulation of technique, art, feeling and culture should be lost, or through restoration be given back to us.”

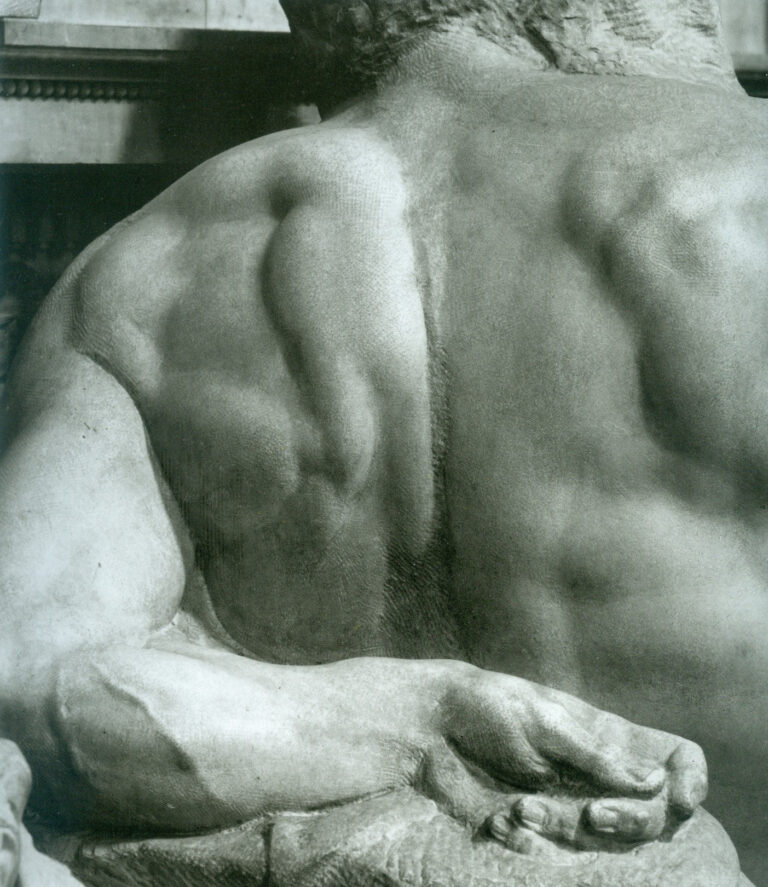

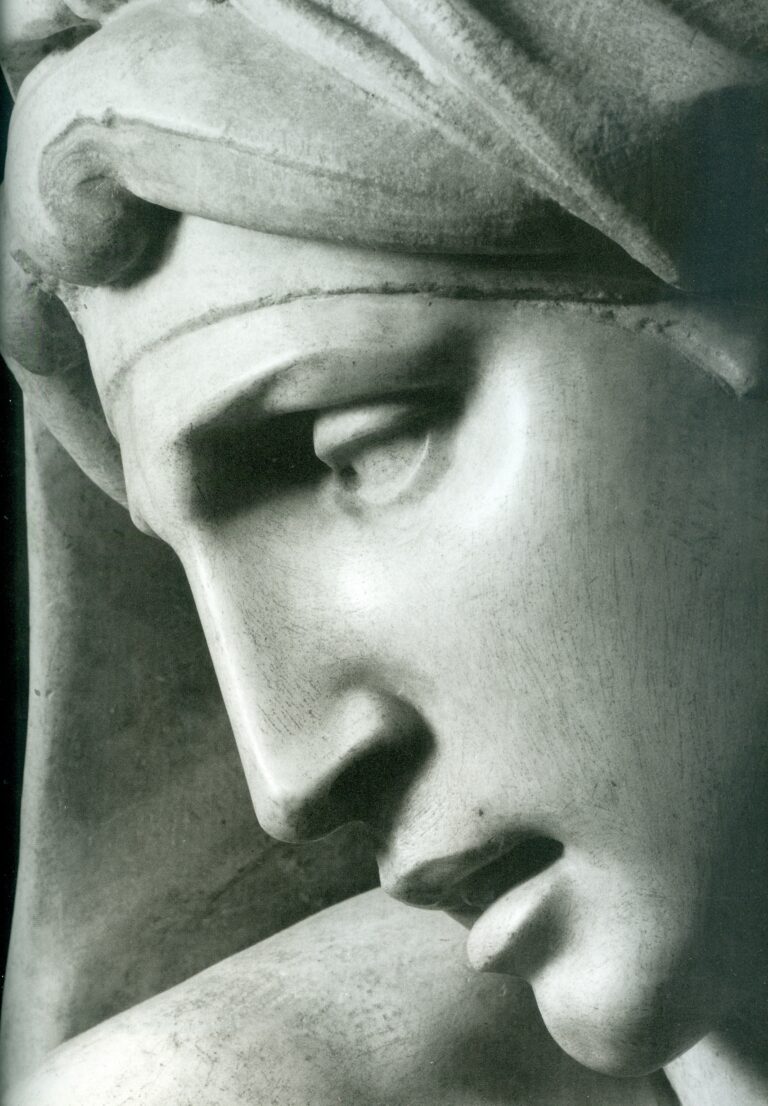

Sadly, we already now know the answer to that question: the serried, bug-happy, high priestesses of “gleaming whiteness” have had their swift revenge. We can only await their published report. It is a small consolation, but the 1993 Beck et al book and its superb Aurelio Amendola photographs was a jewel of publishing in its day, and it must now do further and extra service as a sumptuous elegiac record of what so briefly was allowed to be – as can be appreciated below in the two Amendola shots of the back of Michelangelo’s Day and that of the face of Night:

In Part II we examine how the twin Sistine and Brancacci Chapels colourisation projects came into being.

Michael Daley, Director, ArtWatch UK, 26 May 2021

ENDNOTE:

The Vatican’s complete official account is carried in this sequence of books:

1986: The Sistine Chapel: Michelangelo Rediscovered – featuring Carlo Pietrangeli, Fabrizio Mancinelli, Gianluigi Colalalucci, John Shearman, John O’Malley, S. J., Pierluigi de Vecchi, Michael Hirst.

1987: The Conservation of Wall Paintings Getty/Courtauld Symposium, Fabrizio Mancinelli – “The Frescoes of Michelangelo the Vault of the Sistine Chapel: Conservation Methodology, Problems, and Results”, and Gianluigi Colalucci – “The Frescoes of Michelangelo on the Vault of the Sistine Chapel: Original Technique and Conservation”.

1991: The Sistine Chapel (2 Vols., Edition 500) – featuring Frederick Hart, Gianluigi Colalucci, Fabrio Mancinelli.

1992: The Sistine Chapel ~ A Glorious Restoration – featuring Carlo Pietrangeli, Fabrizio Mancinelli, Gianluigi Colalucci, Nazzereno Gabrielli, Michael Hirst, John Shearman, Matthias Winner, Edward Maeder, Pierluigi de Vecchi, Piernicola Pagliara.

1992: The Art of the Conservator, Ed. Andrew Oddy (British Museum Press), Fabrizio Mancinelli – “Michelangelo’s Frescoes in the Sistine Chapel”.

1996: Michelangelo: The Vatican Frescoes – featuring Pierluigi de Vecchi and Gianluigi Colalucci.

1997: Michelangelo: The Last Judgement – featuring Dr Francesco Buranelli, acting Director General Papal Monuments, and Galleries, Loren Partridge, Fabrizio Mancinelli, Gianluigi Colalucci.

2013: La Capella Paolina – Featuring Anonio Paolucci, Arnold Nesselrath, Paolo Nicolini.

Additionally, for technical, methodological, and philosophical fresco conservation matters, see:

1984 Conservation of Wall Paintings (Butterworth) – by Paolo Mora, Laura Mora, Paul Phillipot (see Fig. 11 above).

And, for the chief restorer’s own account:

2016: Michelangelo and I ~ Facts, People, Surprises and Discoveries in the Restoration of the Sistine Chapel – Gianluigi Colalucci.

Leave a Reply