Mondrian, Schmondrian – another lapse of museum expertise

Another day, yet another herd of museum experts are bitten by a work that should not, on a cursory glance, have been taken as what it purported to be.

Yesterday Nina Siegal reported in the New York Times (‘It Might Have Been a Masterpiece, but Now It’s a Cautionary Tale’) on the mega-embarrassment of museum experts at the Bozar Center for the Arts in Brussels, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland, who had all taken on trust a work of unexamined provenance owned by an anonymous private collector who lives in Switzerland. As Ms Siegal puts it:

“What started out as a potentially major cultural discovery now turns out instead to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of presenting works of art owned by private collectors that have not been systematically vetted. In this case, art experts seem to have passed the buck on conducting basic due diligence on the artwork before displaying it as a Mondrian — putting their own reputations on the line because they gave such credence to a private collector.”

It seems that the director of the Stedelijk Museum saw the pretendy Mondrian at the home of the said collector and discussed the possibility of exhibiting it at the Stedelijk – to which museum it was sent for examination. In self-exculpation the museum now bleats in a reported official statement that a) the Stedelijk was unaware of any doubts about the painting’s authenticity – despite the fact that it had twice been rejected by a leading authority on the artist, and, b) that, besides, the task of a museum is: “to promote art, try to show works that are not yet known to the public and in order to do so, build connections with private collectors. It is not the role of a museum to determine authenticity of a work.”

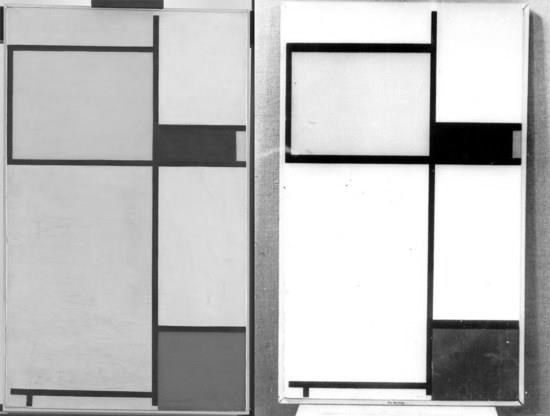

We beg to differ. We would respectfully suggest that it is the first and prime duty of a museum to know its art from its elbow. All museums should look carefully and critically at any work offered on loan and take nothing on trust. In this case the most obvious first step would have been to compare the photograph of the bona fide Mondrian that had been thought lost during the Second World War with a photograph of the newly presented work and see if any differences emerge. We show below the lost Mondrian on the right and its supposedly resurrected self on the left. Is it really so difficult these days for museum experts to see that these two photographic records are not of the self-same work?

Michael Daley, 20 September 2017

23 September 2017, UPDATE. Philip Coucke, a member of the Brussels Bar, writes:

“The Belgian Bozar ‘center of the arts’ paid several thousand euros for a restoration of the fake Mondrian in consideration of the loan. Their lame excuses sound like a politician trying to explain away the inexplicable – ‘We are not a museum’ and we don’t do ‘authentications’. Why would any publicly funded institution pay for the restoration of admittedly ‘unauthenticated’ paintings?”

Leave a Reply