The Leonardo Salvator Mundi Saga: Three Developments

“The more I read it, the more it looks probable.”

Above, Salvator Mundi, the painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and sold at auction in 2017 for $450 million. Photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images – as published on 2 April 2018 in Buffalo News

The sensational Mail Online story (“EXCLUSIVE: The world’s most expensive painting cost $450 MILLION because two Arab princes bid against each other by mistake and wouldn’t back down (but settled by swapping it for a yacht”) discussed here in this News & Notices post, has been questioned or disparaged by a number of commentators but not directly challenged by Christie’s, so far as we know. On March 30 Bendor Grosvenor wrote (“Who underbid the Salvator Mundi?):

“I’m sceptical about this version of events. First, the source seems determined to prove mainly that the picture is somehow ‘not worth’ what it made – the figure of $80m is mentioned – when there were other underbidders up to the $200m level. Second, I’ve been told that the underbidder to $400m was not from the Middle East, from a source who would know.”

Had Grosvenor’s source been correct and the Mail’s story, thus, been seriously misleading, one would expect Christie’s’ lawyers to have demanded either changes to the online article or its removal. Grosvenor’s seeming partisanship on the Salvator Mundi case takes two forms. As well as knocking the knockers, he hypes his brother-auctioneers’ hype, as, on November 12 2017 (“Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ to be sold at Christie’s”):

“I love this video of people seeing Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi. Christie’s say 20,000 have been to see the painting on its world tour. I’ve been impressed by how Christie’s have marketed the picture – in fact, I’d say that they’ve taken marketing Old Masters to a whole new level. A well deserved AHN pat on the back to all involved. The sale is on Wednesday 15th November. Anyone care to make a prediction?”

On November 16, the day after the $450m sale, Grosvenor was ecstatically supportive (“’Salvator Mundi’ – the most expensive artwork ever sold at auction”):

“Christie’s just did something that re-writes the history of auctioneering. They took a big gamble with their brand, their strategy to sell the picture, and not to mention the reputations of their leadership team, and they pulled it off. They marketed the picture brilliantly – the best piece of art marketing I’ve ever seen. Above all, they had absolute faith in the picture. AHN congratulates them all.”

Pace Grosvenor and his sources, questions on Christie’s marketing of the Salvator Mundi persist. The whispering campaign against the Mail’s disclosures has not worked. In this weekend’s Financial Times the author Melanie Gerlis closed her art market column with the item below:

As things stand, no one has disproved the Mail’s suggestion that the (disputed) Leonardo Salvator Mundi has been swapped for a luxury yacht. In her book Art as Investment, Gerlis noted that because the “worth and price are known to only a few” in an art market that is underpinned by a lack of “verifiable and meaningful data”, those looking to art purely as a secure investment “might first consider looking elsewhere.”

With the Salvator Mundi, some 13 years after its emergence, we still do not know when, where and by whom the painting was bought. There have been many conflicting accounts on the work’s ownership (see below). In the April 6 Antiques and Arts Weekly, the New York dealer Dr Robert Simon was asked: “Can you say where you found Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’?” He replied:

“Alex and I acquired the painting at an estate auction in the United States, but we’ve never divulged the location of the auction. We were not permitted to, according to the terms of the confidentiality agreement we signed at the time we sold the painting.”

The sale was conducted privately in 2013 through Sotheby’s when it was acquired by the “Freeport King”, Yves Bouvier, who was acting as an agent for the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev. Did Sotheby’s insist that the origin of the picture not be disclosed? Or Bouvier? Whomever – the enforced confidentiality clause was made eight years after the claimed discovery/acquisition in 2005. However constricting the terms of the 2013 sale agreement might have been, they could hardly account for the non-disclosure of the owners’ identities for the previous eight years – including the time the picture spent in the National Gallery. When the Salvator Mundi was about to enter the Gallery’s big Leonardo show in 2011 as an autograph Leonardo, the Sunday Times reported:

“Its ownership is a closely guarded secret. Robert Simon, a New York art dealer, is representing the owner, or owners – the official line is it is a ‘consortium’.”

Why, then, did the National Gallery agree to participate in this secrecy on the ownership of a painting whose (contested) Leonardo ascription had been supported by the gallery’s own director; by one of its curators; and, by one of its trustees?

Another of the scholar-supporters of this upgraded Leonardo is Professor Martin Kemp. In 2011 Kemp told the Sunday Times how he had been invited to view the work by the National Gallery (“there’s something it’s worth you coming in to look at”, was how Kemp put it). Kemp described entering the National Gallery’s conservation studios and joining “a little group of people, including some Leonardo scholars from Italy and America, and Robert Simon.” Robert Simon had been accompanied on that trip by the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini. In 2012 Modestini would deliver a paper on the picture’s (then) two restoration campaigns at a conference held in the National Gallery.

FRESH CLAIMS

On April 6 Buffalo News reported that Dianne Modestini was to speak on April 9 in the Burchfield Penney Art Center at SUNY Buffalo State and was about to make two new claims.

First, that she and her late husband, the restorer Mario Modestini, had entertained no doubts that this was an autograph Leonardo painting: “We were completely convinced and we felt that we could justify this to anyone without sounding like idiots.” This goes further than Modestini’s 2012 paper: “…when I first saw it I never imagined what would transpire with this lovely but damaged painting on panel…I wasn’t aware of a lost, much-copied Salvator Mundi by Leonardo and I was perplexed. I showed the painting to my then 98 year old husband, Mario…He looked at it for a long time and said, ‘It is by a very great artist, a generation after Leonardo’.”

Second, that no technical evidence had emerged to confirm authorship by Leonardo. Modestini reportedly said that what made her so sure was not “the discovery of any single clue attributable to the master’s style or any technical element of the painting that could be traced to his hand, but rather the quality of the painting”. There was “no under-drawing for example, that was Leonardo’s drawing style, or anything like that. The pigments are the pigments that any one of his contemporaries could have used, and did.” This attribution was entirely a matter of judgment: “the quality of the painting, the sort of old-fashioned connoisseurship and skills, which art historians have always used to make an attribution, were in the end the telling factor for us.”

Those present at her lecture might have learnt why a painting that had so soon revealed itself as an autograph Leonardo to two experienced restorers and in which “apart from the discrete losses, the flesh tones of the face retain their entire structure, including the final scumbles and glazes” had needed a third campaign of restoration with substantial repainting of the face, some time between 2016 (when the Qataris reportedly turned down a private offer of the painting for $80m) and the spectacular $450m sale at Christie’s on 15 November 2017 amidst modern works, not old masters.

A NEW BOOK – FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

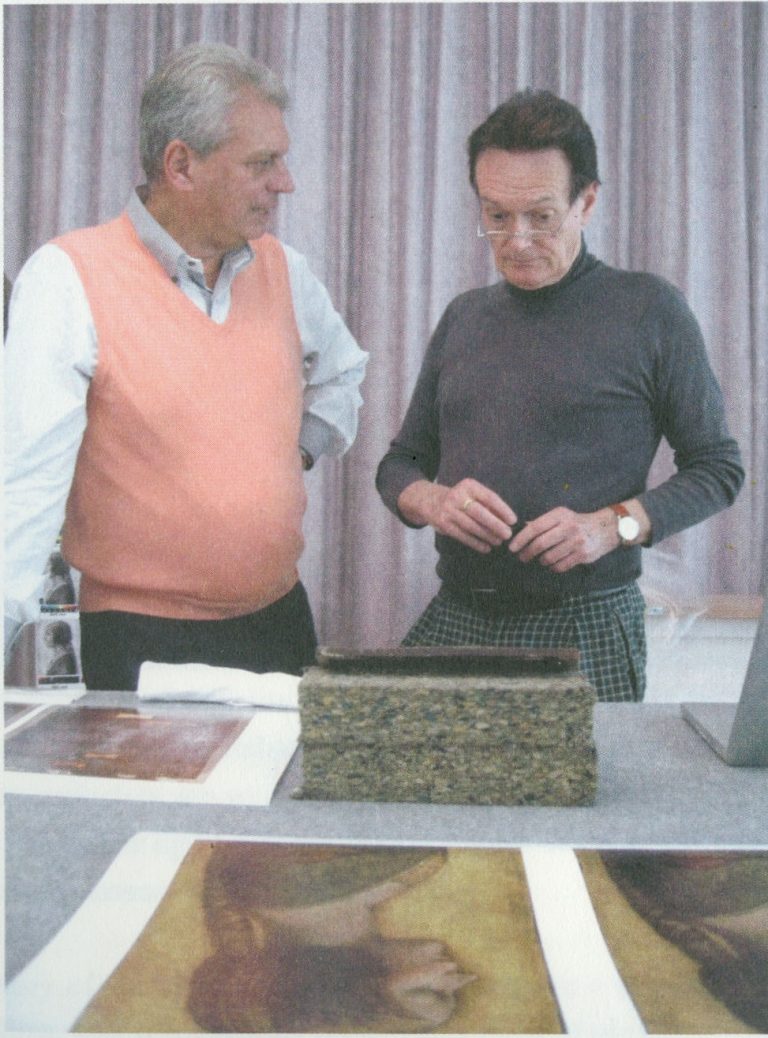

Above: left, Peter Silverman, the owner of the drawing “La Bella Principessa”; right, Professor Martin Kemp, author of the 2010 book “La Bella Principessa” – The Story of the New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci. Photo: as published in Martin Kemp’s Living With Leonardo

Professor Martin Kemp has published a new book (Living with Leonardo – Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond) in which he pays a back-handed compliment to ArtWatch in his second chapter: “Theirs has been the most sustained and fully researched of the hostile polemics”. Elsewhere he launches a series of slurs against three named ArtWatch UK contributors and officers in defence of his own support for two recently attributed Leonardos, the Salvator Mundi painting, and the mixed media drawing on vellum glued onto oak, that he dubbed “La Bella Principessa”. The slurs will be refuted, but we note here that Kemp has now provided a fuller, and apparently verbatim, account of the National Gallery’s invitation to him to view the Salvator Mundi:

“On 5 March 2008, my birthday, an email arrived, announcing the appearance of a new Leonardo – a painting rather than a drawing […It] came from a well known source: Nicholas Penny, then director of the National Gallery in London.

“I would like to invite you to examine a damaged old painting of Christ as Salvator Mundi which is in private hands in New York. Now it has been cleaned, Luke Syson and I, together with our colleagues in both paintings and drawings in the Met, are convinced that it is Leonardo’s original version, although some of us consider that there may be [parts? – Kemp’s parenthesis] which are by the workshop. We hope to have the painting in the National Gallery sometime later in March or in April so that it can be examined next to our version of the Virgin of the Rocks. The best preserved passages in the Salvator Mundi panel are very similar to parts of the latter painting. Would you be free to come to London at any time in this period? We are only inviting two or three scholars.”

The following observations on that stage of the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo accreditation might be made:

1) The method of inviting successive select groups of scholars to see and appraise the painting in the prior knowledge of others’ support for the new attribution might be thought to have fallen short of the National Gallery’s own practices. When Nicholas Penny, as a curator at the National Gallery, proposed the Northumberland version of Raphael’s Madonna of the Pinks as the original painted prototype of the very many versions, he first published a thorough and well-received scholarly article in the Burlington Magazine, and later invited a group of some thirty Raphael scholars to discuss the matter during a day-long symposium at the National Gallery.

2) With this Salvator Mundi upgrade, none of the fifteen or so invited experts has published a case for the attribution. Robert Simon has yet to publish the researches to which both Modestini’s restoration report and Luke Syson’s exhibition catalogue entry were indebted. It is not clear whether Modestini was present when the painting was examined at the National Gallery. Kemp writes in his new book:

“No one in this assembly was openly expressing doubt that Leonardo was responsible for the painting, although the possibility of participation by an assistant or two was generally acknowledged. I sensed that Carmen [Bambach, of the Metropolitan Museum drawings] was the most reserved about the painting’s overall quality. A general discussion followed. Robert Simon, the custodian of the picture (whom I later learnt was its co-owner), outlined something of its history and its restoration. He seemed sincere, straightforward and judiciously restrained, as proved to be the case in all our subsequent contacts…”

Carmen Bambach rejected the Leonardo attribution in a 2012 Apollo review of the National Gallery exhibition and gave the painting to Leonardo’s student Boltraffio. Ironically, the Times reported on 9 April 2017 that Kemp has now demoted the Hermitage Museum’s Litta Madonna (which was included as a Leonardo in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition) from Leonardo to Boltraffio.

3) After seeing the Salvator Mundi next to the National Gallery’s version of Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks (which is to say, its second version), Dianne Modestini was inspired to change the appearance of the former:

“There were actually two stages of the current restoration. In 2008 when it went to London to be studied by several Leonardo experts, there was less retouching. I hadn’t replaced the glazes on the orb, finished the eyes, suppressed the pentimenti on the thumb and stole, and several other small details but, chiefly, the painting still had the mud-coloured modern background that was close in tone to the hair. Two years later I was troubled by the way the background encroached upon the head, trapping it in the same plane as the background. Having seen the richness of the well-preserved browns and blacks in the London Virgin of the Rocks and based on fragments of the black background which had not been covered up by the repainting, I suggested to the owners that it might be worthwhile to try to recover the original background and finish the complete restoration.”

Thus, Modestini had intervened radically on the painting shortly before it was included in the National Gallery’s major 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition and two years after it was appraised by selected Leonardo scholars at the National Gallery.

4) Restoration campaigns, like wars, are easy to start. In 2012 Modestini acknowledged an ambition to finish a “complete restoration”, after seeing the National Gallery’s restored Virgin of the Rocks. Permission, she recalled, was granted to strip and repaint the entire background:

“The initial cleaning [i. e. paint and varnish removal] was promising especially where the verdigris had preserved the original layers. Unfortunately, in the upper parts of the background, the paint had been scraped down to the ground and in some cases the wood itself. Whether or not I would have begun had I known, is a moot point. Since the putty and overpaint were quite thick I had no choice but to remove them completely. I repainted the large missing areas in the upper part of the painting with ivory black and a little cadmium light red, followed by a glaze of rich warm brown, then more black and vermilion. Between stages I distressed and then retouched the new paint to make it look antique. The new colour then freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair, and made a different, altogether more powerful image.”

5) “Restorations”, which might more accurately be described as “stripped and painted re-presentations commissioned by owners”, are rarely straightforward and unproblematic. Modestini made her decisions in the sincere belief that the London Virgin of the Rocks is an entirely autograph Leonardo painting and therefore a reliable guide to her own interventions on the Salvator Mundi. However, that Leonardo attribution has only been widely thought to be the case since the painting’s recent restoration. Kenneth Clark, when director of the National Gallery thought otherwise. In 1944 he said of the head of the picture’s angel: “This is one part of our Virgin of the Rocks where the evidence of Leonardo’s hand seems undeniable, not only in the full, simple modelling, but in the drawing of the hair. The curls around the shoulder have exactly the same movement as Leonardo’s drawings of swirling water. Beautiful as it is, this angel lacks the enchantment of the lighter, more Gothic angel in the Paris version…” Of the head of the Virgin, Clark wrote:

“…It is uncertain how much of this replica [of the first, Louvre, Virgin of the Rocks] he [Leonardo] executed with his own hand, and this head of the Virgin is the most difficult part of the problem. It is too heavy and lifeless for Leonardo and the actual type is un-Leonardesque; yet it is painted in exactly the same technique as the angel’s head in the same picture; and that is so perfect that Leonardo must surely have had a hand in it. Both show curious marks of palm and thumb…made when the paint was wet, and no doubt covered by glazes long since removed. This perhaps is a clue to the problem. A pupil did the main work of drawing and modelling, and before the paint was dry Leonardo put in the finishing touches. Most of these have been removed from the Virgin’s face but remain in the angel’s, where perhaps they were always more numerous.”

Above, top: The head of the Virgin in the National Gallery’s (second) version of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin of the Rocks, as published in 1944 in Kenneth Clark’s One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery. Above, the Head of the Virgin as published in the 1990 re-issue of Clark’s “Details” book and, therefore, after its post-war restoration by Helmut Ruhemann but before its more recent re-restoration by Larry Keith (in which the mouth of the Angel was altered, on Luke Syson’s advice, as discussed here in “Something Not Quite Right About Leonardo’s Mouth ~ The Rise and Rise of Cosmetically Altered Art”).

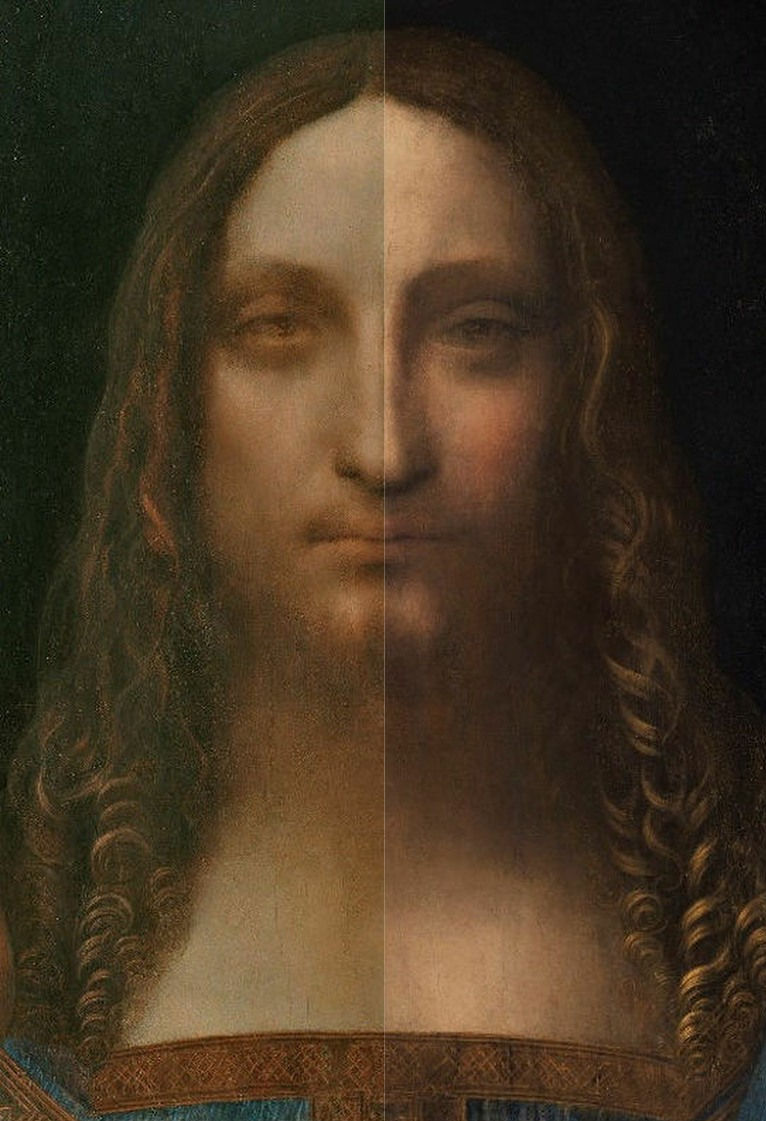

Above, the face in the accredited Leonardo da Vinci Salvator Mundi, as exhibited, left, in the National Gallery in 2011-12, and, right, as when sold at Christie’s in November 2017.

In 1990 the National Gallery remarked that “as a result of” the picture’s 1949 restoration “the differences between the heads are perhaps less apparent”. That being so, either one face had received new glazing or the other had lost original glazing. For Kemp, a crucial technical proof of Leonardo’s authorship of the Salvator Mundi is the fact that technical examinations had disclosed that “As is generally the case with Leonardo, infrared rays delivered the most striking results. It was good to be able to see that the artist had pressed his hand in to the tacky paint above Christ’s left eye – which we have seen to be characteristic of Leonardo’s technique.”

THE UNDERSTANDING TODAY ON THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S OWNERSHIP BETWEEN 2005 AND 2013

In his seventh chapter (“The Saviour”) Kemp twice discusses the ownership of the Salvator Mundi. He does so first with regard to the exclusion from the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition of the “La Bella Principessa” drawing (– whose Leonardo ascription he has energetically advocated):

“This episode highlighted the rationale for the inclusion of the Salvator Mundi. Was it on the market? Would exhibiting it mean that the National Gallery was tacitly involved in a huge act of commercial promotion? It seemed highly likely that it was also ‘in the trade’ [like the ‘La Bella Principessa’]. All I knew at this stage [2011] was that it was being represented by Robert Simon. He told me that it was in the hands of a ‘good owner’ who intended to do the right thing by it, and I did not inquire any further.”

So, it would seem that the National Gallery had not disclosed the identity of the owner/owners to the scholars it invited to appraise the painting. Kemp continued:

“I was keen to consider the painting in its own right, not in relation to its ownership. I speculated, of course, that Robert might have a financial interest, perhaps a share in its ownership; and I assumed that he was gaining some kind of legitimate income from his work on the picture’s behalf. But the gallery was assured that the work was not on the market. Understandably keen to exhibit it, they were happy to accept this assurance…Might the Salvator have been less well regarded if its messy sale [in 2013, privately through Sotheby’s] to Bouvier [for $80m – $68m in cash and a Picasso valued at $12m, according to Georgina Adam in her “Dark Side of the Boom” book] and its resale [to Dimitry Rybolovlev for $127.5m] had been apparent before its public debut [at the National Gallery in 2011-12]? It has turned out to be a substantial mess. In November 2016, an article in The New York Times reported the latest developments: three ‘art traders’ (Robert Simon, Warren Adelson and Alexander Parrish) were disconcerted to find that painting was ‘flipped’ by Bouvier for $47.5m more than their selling price. Was Sotheby’s a knowing party to the the resale? The auction house claimed that it was not, taking pre-emptive legal action to block any law suit by the ‘traders’….It was however a great surprise to find that the Salvator was to be sold at Christie’s in New York on 15 November 2017 at a mega-auction of celebrity works from the modern era. The auctioneers sent the painting on a glamorous marketing tour of Hong Kong, San Francisco and London. I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.”

Where would we be without a free and vigilant press? Where, precisely, is the $450m Salvator Mundi today?

Michael Daley, 10 April 2018

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: No. 3 [11 March 2018] – The Reception of the First Version of the Leonardo Salvator Mundi

Mounting concerns over transparency in art world deals are throwing back-dated light on the Salvator Mundi’s reception in its first-restored incarnation when included in the 2011 National Gallery exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S FIRST PUBLIC OUTING IN 2011

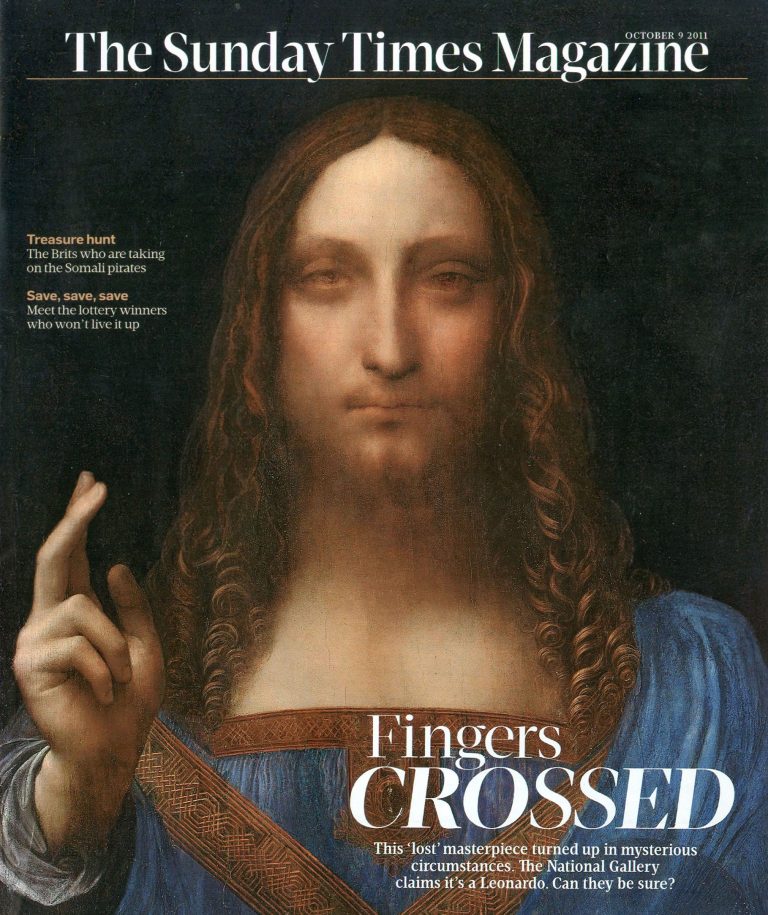

Above, top, the Sunday Times magazine cover of 9 October 2011. Above, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen after repainting in 2011, left; above, right, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen in November 2017 after further repainting between 2012 and 2017.

In the 9 October 2011 Sunday Times (“LEONARDO? CONVINCE ME”), Kathy Brewis wrote:

“For a few weeks in London you will be able to see the Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World) up close. It might be your only chance. Much of the painting’s history remains obscure. Its ownership is a closely guarded secret. Robert Simon, a New York art dealer, is representing the owner or owners – the official line is it is a ‘consortium’. Why all the secrecy? ‘It’s just privacy and security’, says Simon, ‘One doesn’t want people knocking on the door.’

“…He showed it to Mina Gregori, a retired professor at Florence University, who was stunned: ‘I believe it’s by Leonardo.’ Then he showed it to Nick Penny, who had just been appointed director of the National Gallery. ‘He understood it in a nanosecond. He said that one of his ambitions was for the gallery to be a venue for scholarly inquiry and research and that he’d like the painting to be brought to London so it could be compared with the Virgin of the Rocks.’ It was Penny who told him [Simon]: ‘You need a consensus…’

“Since Robert Simon went public with the discovery, he has received many emails from Leonardo fanatics. ‘There’s the serious obsession and there’s the lunatic one – people for whom Leonardo is a source of fantasy. The paintings are not knowable,’ he muses. ‘Every one of them presents a problem and a challenge.’ Even at this stage? ‘Art historians are a prickly, competitive lot. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone stuck their hand up and said “I don’t believe it”’. Could the experts be wrong? ‘They could be wrong about anything. But as much as I believe anything in this world, I believe this is by Leonardo.’”

Above, and top left, the Salvator Mundi as exhibited in 2011 at the National Gallery’s big Leonardo exhibition.

Kathy Brewis continued:

“…Frank Zöllner of Leipzig University [- and author of the Leonardo catalogue raisonné] is a rare dissenter: he thinks the proportions of the nose (‘too long’ for such a perfectionist as Leonardo) make it more likely to have been painted by a talented follower. The rest are convinced, if a little jealous that they didn’t unearth it themselves. ‘People in the art world get sniffy about dealers,’ says Bendor Grosvenor, director of the London fine-art dealership Philip Mould. ‘But if it wasn’t for the trade, discoveries like this wouldn’t be made. Specialist dealers are the ones who are prepared to buy a dirty picture, roll their sleeves up and get stuck in to seeing what it is.’

“Is it wise for the National Gallery to put it on show so soon after its authentication? ‘They are taking a risk,’ says Grosvenor, ‘and I can’t applaud them enough for it. Connoisseurship is a nebulous discipline. There can never be absolute 100% proof. You have to accept there’s an element of doubt and go with it.’”

Note – On 5 March 2018 Grosvenor declared himself an ex-dealer on his blog Art History News: “Now, portraiture can be a hard sell – I know this from having spent over a decade actually selling portraits, in my former life as a dealer.” This did not come as an absolute bolt out of the blue: although he remains a director of the Scottish auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull Limited, last year Grosvenor briefly closed down his website following certain professional criticisms, commenting as he did so: “at the same time AHN also makes me a significant number of, well, ‘enemies’ is not too strong a term. Every walk of life has its Salieris, but in the art market there are an awful lot of them.”

Kathy Brewis continued with a discussion on the Salvator Mundi’s owners:

“Luke Syson, the show’s curator is one of the few people who know who owns the picture. ‘We couldn’t exhibit it otherwise. It’s not being wafted to us in a brown envelope.’”

Ben Hoyle reported the Salvator Mundi’s owners’ plans in the Times of 12 November 2011 (“It’s kind of scary – I wrapped it in a bin liner and jumped into a taxi with it”):

“‘Everyone involved recognises the importance of it as a work of art. Doing the right thing has been very important and will continue to be,’ Mr Simon says. If that means selling it for half the price they could attract, to ensure that it stays on public view, then they would prefer to do that.”

In the event the picture was sold privately by Sotheby’s in 2013 to a Swiss businessman, Yves Bouvier, who is known as the “Freeport King” (and who, among many commercial interests, owns an art conservation and authentication service), for appreciably less than the sums of $150-200m being talked about in 2011 (when the owners reportedly had turned down a $100m offer). The original consortium and Robert Simon received $80m for the Salvator Mundi from Bouvier who resold it for $127.5m to the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev.

To this day we do not know who owned the Salvator Mundi before 2005 or between 2005 and 2013. From whomever and by whomever it was bought in 2005, the painting’s reception as an attributed Leonardo in 2011 was very far from uniformly rapturous. In addition to the dissenting scholars we cited on 14 November 2017 (see THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF THE NEW YORK SALVATOR MUNDI), a number of newspaper art critics were un-persuaded.

In the 13 November 2011 Sunday Telegraph (“The genius of Leonardo”), Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote:

“…The picture is certainly Leonardesque. But is it by Leonardo? That is the considerably-more-than-million-dollar question for the consortium of art dealers who acquired the work a few years ago for an undisclosed sum. If the attribution holds up they can expect to reap £125m as a reward for their good judgement.

“Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan is a breathtaking and truly remarkable exhibition which brings together around half of the surviving 15 or so surviving paintings by the famously dilatory artist of the Italian Renaissance…Two works in particular appear destined to come under scholarly fire.

“Although it gets the thumbs up from the National Gallery’s curator, [Luke] Syson, there will certainly be those who question the new Christ. The picture undeniably displays a number of the painter’s characteristic devices and mannerisms, but there are other aspects of it that seem foreign to Leonardo himself.

“He was prized by his contemporaries as one of the most innovative and forceful painters of emotion, yet the face of this Christ seems peculiarly inert. Taken individually, its elements are convincing enough, but viewed as a whole its expression seems to lack a certain subtle Leonardo magic: the spark of inner life and feeling…”

Even after the picture had been re-done-over by the restorer, Diane Modestini, ahead of the 15 November 2017 sale, the Sunday Times’ art critic, Waldemar Januszczak, responded with less tact than Graham-Dixon (“The Miracle of da Vinci: Turning a £45 Oddity into a £341m Old Master”, 19 November 2017):

“…To call the Salvator Mundi untypical is massively to understate the case. It resembles nothing else Leonardo painted

“The claim by Loic Gouzer, chairman of contemporary art at Christie’s in New York, that the record-breaking Jesus bears ‘a patent compositional likeness’ to the Mona Lisa had me laughing out loud. Yes, it shows the upper half of a figure in a frame. But that is the only compositional likeness the Salvator Mundi shares with the Mona Lisa…

“The next time I saw the painting was in 2011 when the big Leonardo exhibition was opened in London. Full of magnificent loans – the Lady With an Ermine, from Poland; the Virgin of the Rocks from the Louvre – it really was a once-in-a-lifetime event. And there on the wall was the recently rediscovered Salvator Mundi looking just as strange and sci-fi as I remembered it.

“At the time it was owned by a consortium of art dealers who had bought it in an American estate sale for $10,000 as a work by a follower of Leonardo. The dealers had it comprehensively cleaned and repainted. The National Gallery, eager to give its show a boost, announced it as the first new Leonardo discovered in 100 years. Wow…

“Soon after its London unveiling it was sold on to the Russian Billionaire, Dmitry Rybolovlev, for a reputed £98m. It was Rybolovlev who sold it again in New York last week.

“How did Leonardo’s sci-fi Christ, who looks as if he belongs on the cover on one of L Ron Hubbard’s scientology textbooks, end up costing all those shekels? It was mostly due to the wicked brilliance of Christie’s.

“Not only did the auction house tour the picture noisily to Hong Kong, and London before the New York sale, drumming up interest among the newly rich, but its hype department was also in full swing on this one. Finding a new Leonardo, boomed Gouzer, ‘is rarer than finding a new planet’. It’s ‘the greatest discovery of the century’ repeated the Christie’s chorus.

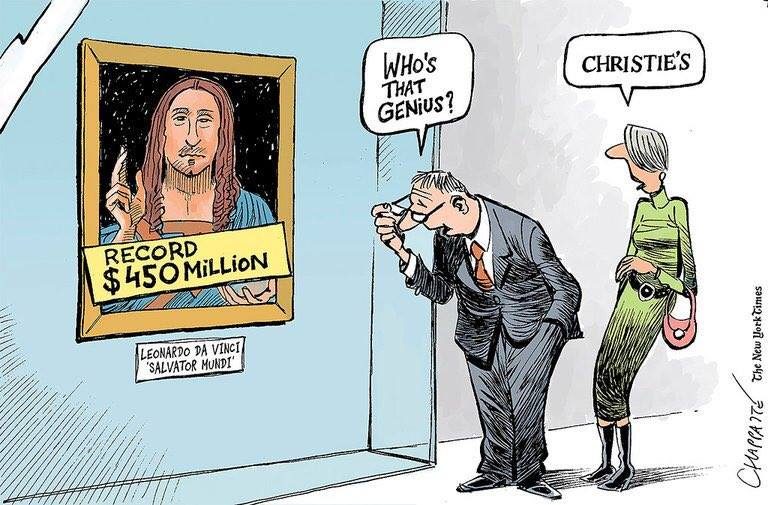

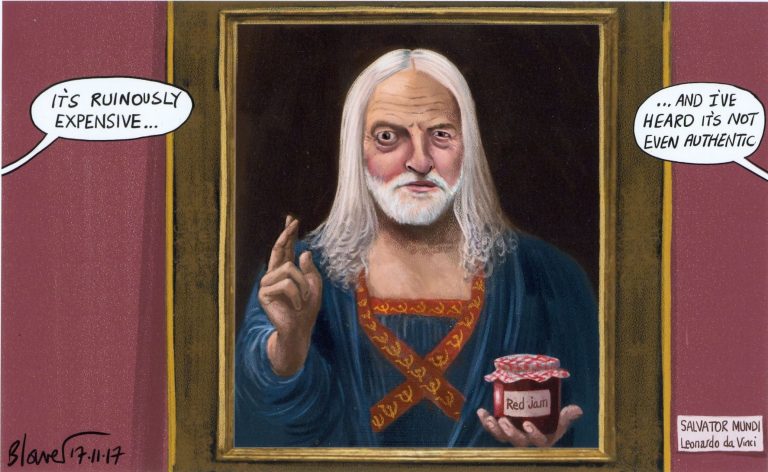

Above, Patrick Chappatte’s take on the Salvator Mundi sale/attribution for the New York Times. Below, Patrick Blower’s incorporation of the Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, for the Daily Telegraph:

Waldemar Januszczak continued:

“In recent years modern art has been where the money goes. A new generation of mega-rich collectors who know a lot about luxury brands but not much about art, have piled into the market and sent prices soaring.

“Earlier this year a quickly splattered Jean-Michel Basquiat of a face shaped like a skull sold in New York for an astonishing £85m. By putting the Leonardo in such a context, Christie’s circumnavigated the knowledgeable world of the Old Master collector and headed straight for the dumb f**** with the money.

“There are various ways to understand events in New York on Wednesday night [of 15 November 2017].

“You can see them as evidence of Leonardo’s treasured and mythic status in art. You can see them as testimony to the power of attribution. Or you can see them as proof that we live in a mad world that has lost sense of true value and in which obscenely rich people waste obscene amounts of money on the obscene acquisition of trophy art. Going, going, gone.”

SUPPORT AND DISSENT

It so happens that the scholar who first attributed the Salvator Mundi to Leonardo, Professor Mina Gregori, was also the first scholar to attribute the proposed Leonardo drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Professor Martin Kemp. However, “La Bella Principessa” was not included in the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition and, seven years later, it remains unsold. Although we know precisely why the dissenting scholars rejected the Salvator Mundi attribution (- they published their views in the scholarly press), we have virtually no information of who said what and in what order among the consensus of scholars listed by Christie’s (see Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation).

SECRET DEALS – AND THE ARTS CLUB

Since we began warning on this site in 2014 of the threat to market confidence posed by the art world’s toxic attributions and specifically called for increased transparency through a statutory requirement that vendors should disclose all that is known and recorded about the provenance and the restoration treatments of works of art (“As things stand, it can be safer to buy a second-hand car than an old master painting” – “Art crime”, ArtWatch UK letter, the Times, 13 August 2014), secret deals have come under increasingly intense investigation. In her 2017 book Dark Side of the Art Boom, Georgina Adam wrote:

“At its base, the Bouvier/Rybolovlev dispute was about the nature of their business conducted within a market that has always thrived on secret backroom deals. By keeping vendors and buyers apart – they may never know who the other is – and insisting on discretion, agents, dealers, advisors can use this anonymity to their advantage. Various reasons can be put forward, from the need for security to the desire to avoid family quarrels or the taxman, to the risk of someone else bagging the work for sale. In the Bouvier/Rybolovlev case, one of Bouvier’s emails about a Magritte, said: ‘I must carry out this [negotiation] with the greatest discretion to avoid drawing attention to the painting and its owner; the risk is that we could lose it at auction.”

In this weekend’s Financial Times (10/11 March 2018 – “Laundering Picasso: British dealer among accused in $50m case”), Melanie Gerlis cites the emergence of another highly embarrassing series of documents:

“Potential shenanigans involving art are in the spotlight once again. London art dealer Matthew Green is among defendants in the case against Beaufort Securities, three other corporations and five other individuals, accused by the US Department of Justice of a multiyear $50m-plus securities fraud and scheme to launder money, partly through the sale of a £6.7m painting by Picasso.

“The indictment alleges that Green, described as the owner of Mayfair Fine Art Limited, met last month with an investment manager from Beaufort Securities (now declared insolvent), as well as a property developer and an undercover federal agent masquerading as a client of the brokerage firm. At this meeting held around February 5, the court papers say that the agent-client was told he could ‘purchase a painting from Green using the proceeds of the stock manipulation deals and later sell the painting to “clean the money”’…The papers describe the art business as ‘the only market that is unregulated’”.

“The papers also say that Green – who had allegedly asked for a 5 per cent profit on the transaction, ‘so that he would not be asked why he was in the money laundering business’”. [Green] sent a message via What’sApp to the Beaufort Securities manager that read: ‘[O]bviously because of the nature of this transaction we need to preserve a certain amount of anonymity which [the undercover agent] and I discussed and clarified at the Arts Club!’”

UNDERCHARGING FOR CURRENT MARKET PRACTICES

The Art Market Monitor blogger, Marion Manneker, made this observation in his (5 March) comments on the trial:

“Green doesn’t seem to know that the price for laundering money is much higher than 5% which definitely isn’t worth the risk if it gets you indicted after being in business all of three months. Worse still, Green and his partners don’t seem to be the swiftest criminals. They boasted that the art market is unregulated but then created a scheme that seems to have had little to do with the art market itself.

“The art sale is only one of several money-laundering venues that the person was offered. Offshore banks and real estate deals figure prominently in the indictment. What’s more, Green’s scheme could have been conducted in just about any commercial transaction. And, since the payment for the Picasso was due March 6, 2018, we’ll never know if Green was actually capable of pulling off the sale at the price he claims or would have survived any kind of audit.”

OLD HABITS DIE HARD?

Manneker’s comments on the cut-price scale of Matthew Green’s alleged laundering service charges recalls certain comments of Kenneth Clark who recognized that his appointment as director of the National Gallery at a very tender age owed much to the fact, as he wrote in his 1977 memoir Another Part of the Wood, that:

“[T]he ideal candidate for the post was disqualified. This was a Finnish art-historian named Tancred Borenius. He was a good scholar, a pleasant companion and a passionate upholder of the concept of the monarchy. He would have made an ideal courtier. Unfortunately, he was known to have followed the continental practice, described above, of taking payments for certificates of authenticity; and what was worse, quite small payments (known as ‘smackers under the table’); if he had taken large payments like a few scholars on the continent, no one would have objected.”

Michael Daley, 11 March 2018

UPDATE, 12 March 2018. On 11 March, a Sunday Telegraph supplement (“Arts, Antiques and Collectibles”) carried a “Promotional feature” – “Managing Risk When Buying and Selling Art” – for the law firm Constantine / Cannon. In offering the firm’s services, the article began:

“TRADING IN ART has traditionally been done on a handshake, but this is changing. You would not buy or sell a house without relying on a lawyer to prepare the contract, would you? The same goes with art, and now buyers and sellers are increasingly turning to lawyers to help them manage the risks associated with expensive works. The art market used to function like a club of like-minded people, but that’s no longer the case. The market now is truly global, and it has become less transparent in the process…”

Nouveau riche? Welcome to the Club!

Our previous news/notice – “A day in the life of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s pricey new Leonardo Salvator Mundi” – was pegged on Georgina Adam’s Financial Times interview with Christie’s CEO, Guillame Cerutti.

In today’s Art Market Monitor blog, Marion Maneker defends Georgina Adam’s book, The Dark side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, against a review in The New Republic:

“Unfortunately, [Rachel] Wetzler’s idea of a critique is to somehow fault Adam for not belabouring the obvious context of her book:

‘But while Adams paints a detailed and convincingly dire picture of the art world’s excesses, she never fully probes its implications. Perhaps ironically, its central weakness is her narrow focus on the activities of the art market itself: Her book largely brackets an exploration of the art market from the broader context of rising income inequality, economic exploitation, and staggering concentrations of wealth in the hands of the very few, all of which have enabled activity at the its upper reaches to continue unabated despite global downturns in other financial sectors. According to the sociologist Olav Velthuis, the art market ultimately benefits from an unequal distribution of wealth, as newly minted billionaires turn to blockbuster art purchases as a means of announcing their arrival…’”

Maneker dismisses the general charge as “both obvious and silly” but sows confusion with a claim that the rich “have many ways to announce their arrival” other than by social climbing. While that, too, may be self-evident it distracts from the force and precision of Adam’s analysis of certain shortcomings within the art market’s own institutions. When speaking of an apparent art world unwillingness to eliminate decades-long fraudulent practices – even after the most revelatory scandals – Georgina Adam (p. 191-2) pinpoints specific failures:

“What is surprising is the lack of impact the art market scandals have actually had, as lawyer Donn Zaretsky told me:

‘I haven’t seen much change after Knoedler [’s great Fakes Scandal]…I still see people doing deals on a handshake. The fact is the art market is a market but also a social world. If people are buying Tribeca real estate they will do the necessary research, bring in the lawyers, stitch up the contracts, and yet if they buy a picture for $3m they will hardly do anything.

‘It’s all part of this social world, meeting the artist, going to the parties. And buying art is an entrée to this world. You need to understand this in order to understand why these things happen, and why the art market will be so hard to regulate.’”

Marion Maneker’s Art Market Monitor blog of 22 February linked to a discussion between Glenn Fuhrmann and Lary Gagosian and noted that: “in this interview, one can see some indications of how deeply Gagosian’s success is tied to his ability to create among his clientele the sense of belonging to an exclusive club.”

There exist further three-way relationships between dealers, auction houses and collectors. Gagosian reportedly underwrote the recent $450m sale at Christie’s of the Salvator Mundi with a $100m guarantee to buy. This is said to have been in exchange for a $60m guarantee from the Salvator Mundi’s vendor to buy – in the very same auction of modern art – a Gagosian-owned Warhol of Leonardo’s Last Supper.

Michael Daley, 27 February 2018