The Saviour and a Stealth-Attribution

Martin Kemp and a dozen (largely mute) art historians bet the professional farm on a “from-nowhere” Salvator Mundi being an autograph Leonardo painting. On fetching $450m in 2017 it disappeared. No-one will say where it is. We now hear from a previously reliable source that it never left New York.

In February’s The Art Newspaper (“Doubly lost: Salvator Mundi fails to show up at the Louvre”) Professor Martin Kemp brings no news on the disappeared picture that he, more than any scholar, has championed. Instead, he bemoans the Salvator’s latest humiliating no-show at the Louvre’s Leonardo blockbuster exhibition (and demotion within the catalogue to the “Cook Collection” work) for having given fresh impetus to “personalised” tweets accusing him of “intimidating academics who disagreed”, and to what he deems fake news stories by journalists who confess to him that “what they are reporting does not stand up to scrutiny”. What never withstood scrutiny is the disappeared Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo ascription. The “qualitative” case for the Robert Simon and Co. picture being a Leonardo always rested on a self-defeating stylistic argument: that some of its parts were exceptionally well painted. We predicted the approaching Louvre no-show and Kemp denied it. Now, bereft of a credible espousal of a disappeared painting’s disappeared Leonardo ascription, Kemp swishes the robe of scholarly piety and tilts at the world’s unfairness:

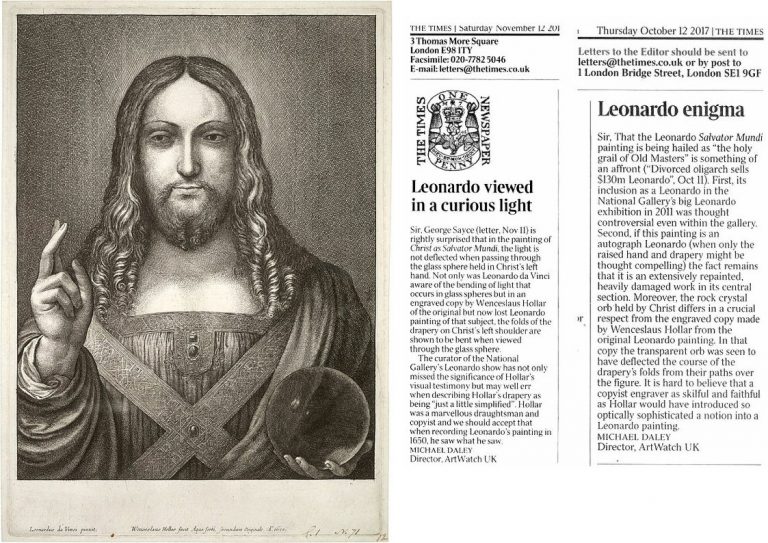

“It has become hard to look fairly at the evidence in the complex, interlocked and cumulative way that Leonardo’s paintings require. In recognising a work as by Leonardo we have the inestimable advantage that we can adduce multivalent factors from his art, theory and science. The disadvantage of this complexity is that if one factor can be picked off (convincingly or not), it can be used to taint the overall argument.” (Emphasis added.) In supposed illustration of such tainting usages Kemp contends: “A good example is the silly dispute about the optics of the sphere that Christ holds in the palm of his hand.” It was not at all a good example to cite: as discussed below, Kemp has successively held two not properly acknowledged conflicted positions on the globe’s optics.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI GLOBE’S DISTORTING OPTICS

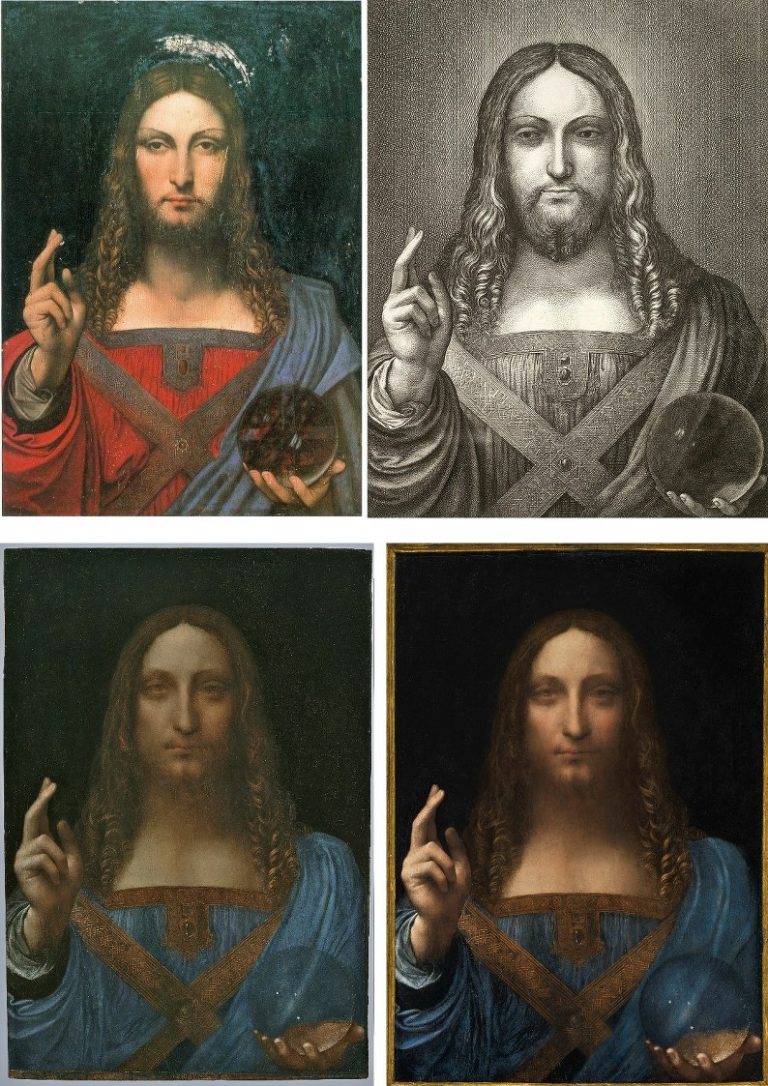

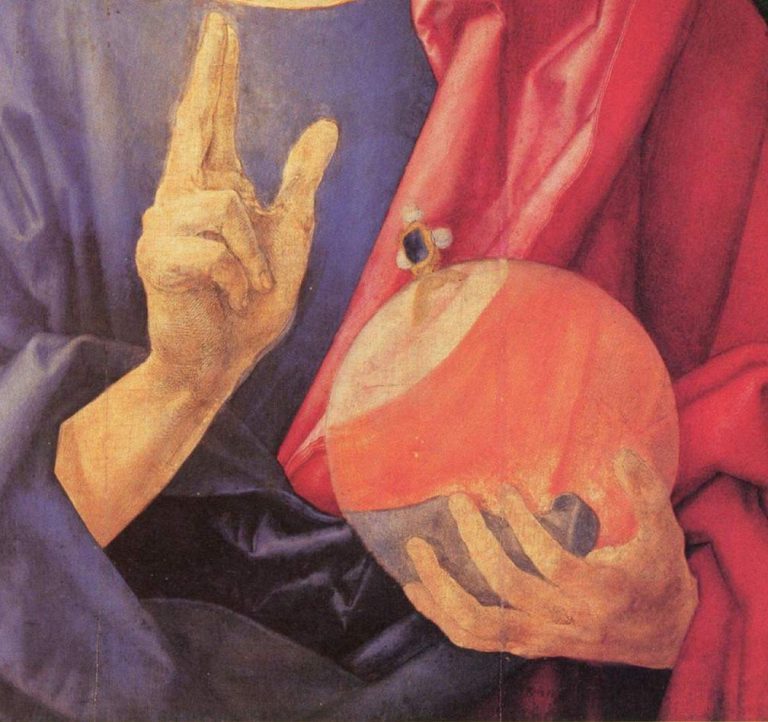

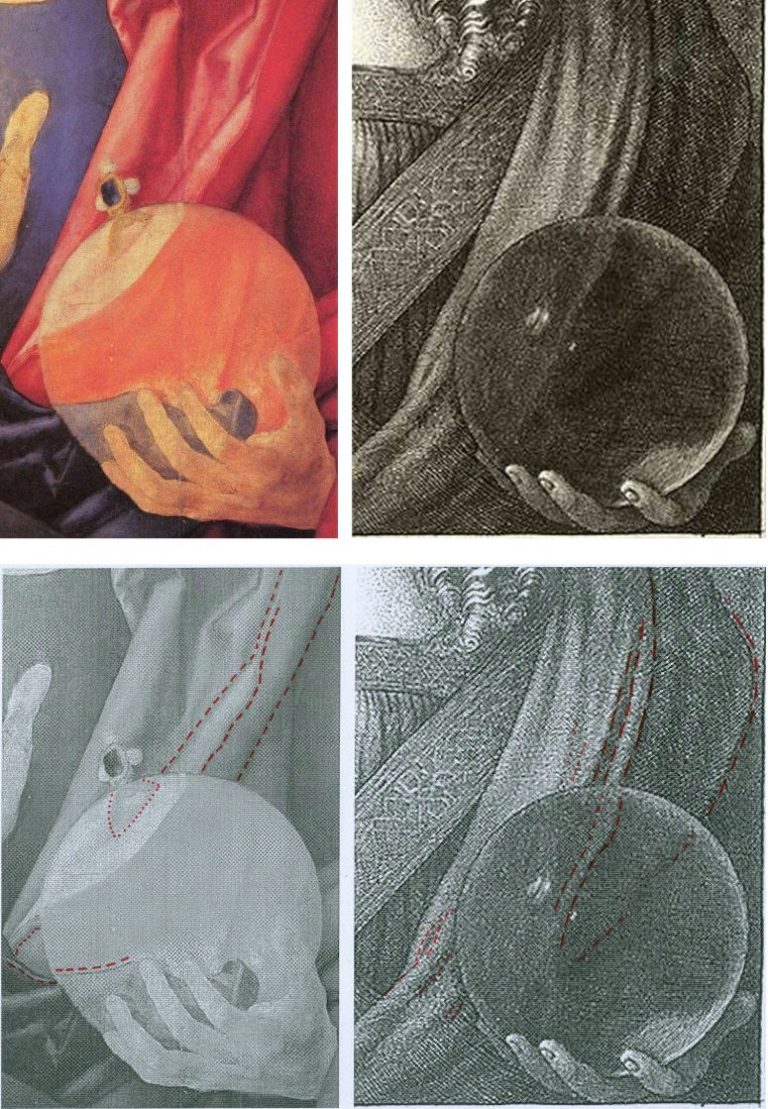

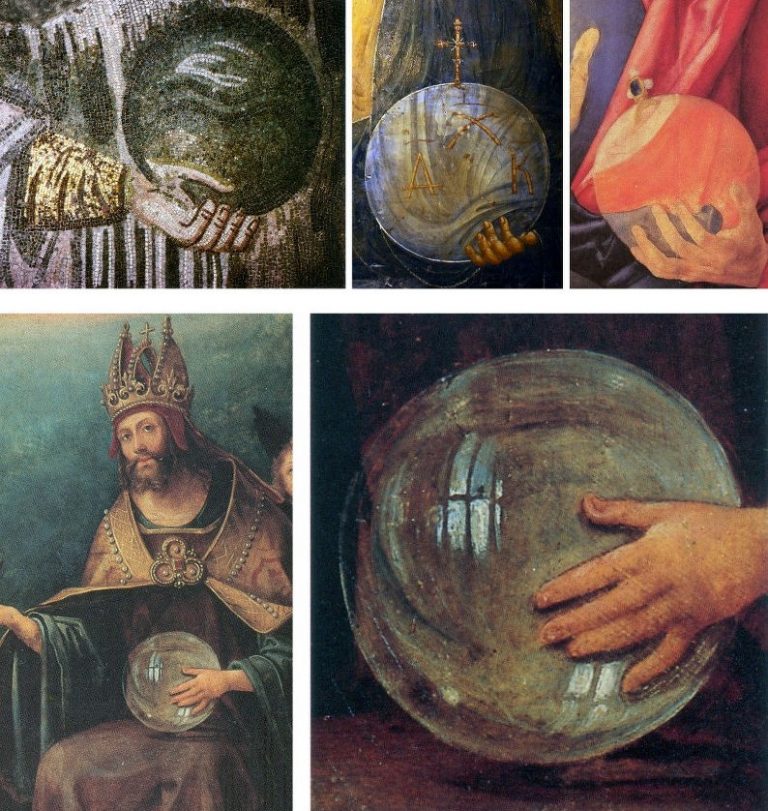

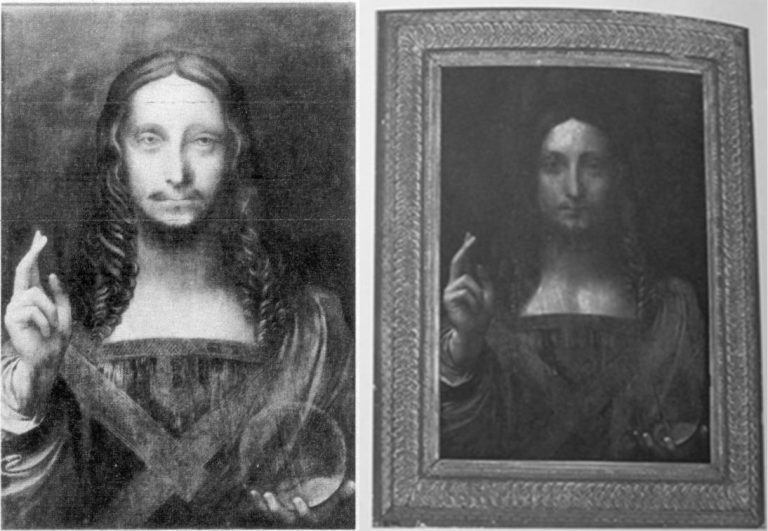

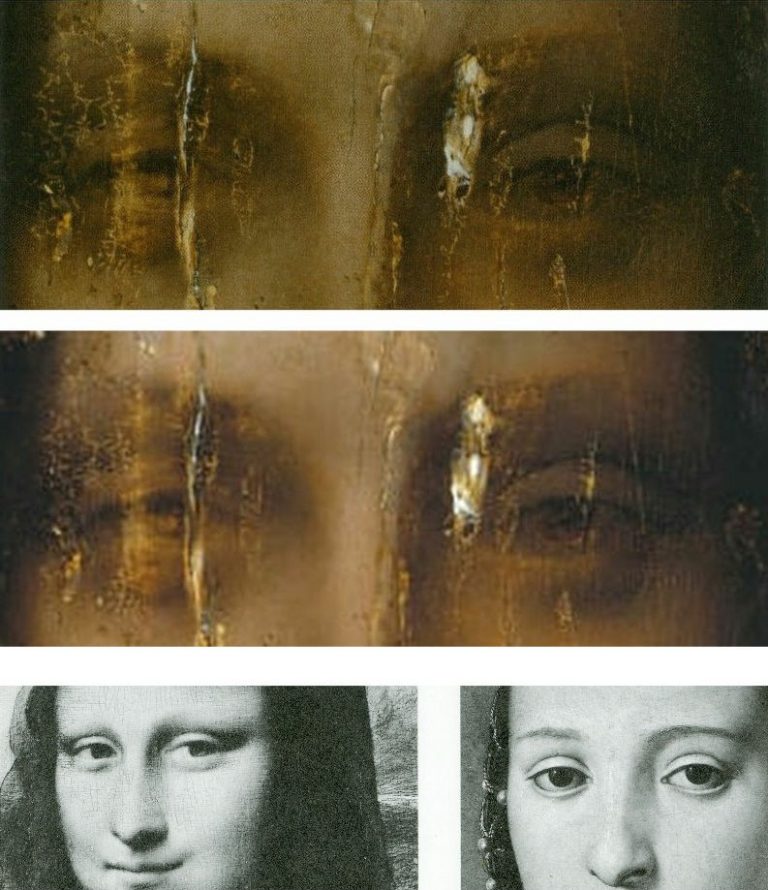

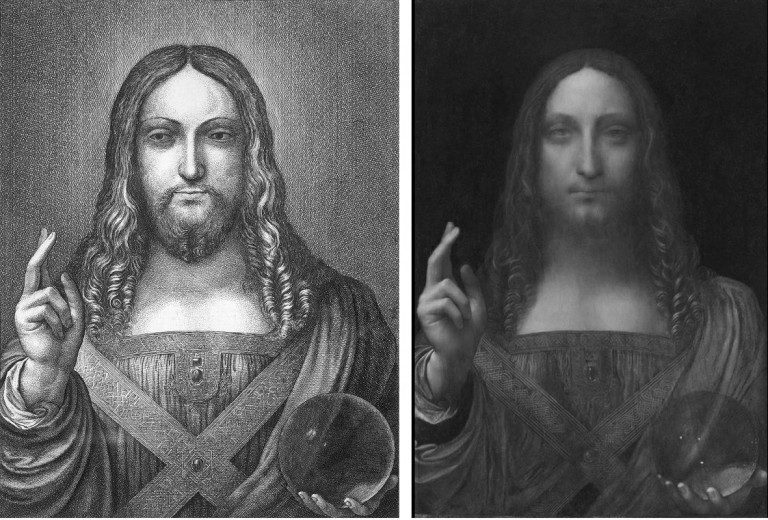

Above, Fig. 1: Bottom row, the missing Salvator Mundi, as exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12, left, and as offered for sale at Christie’s, New York, after further (covert) restoration at New York University in 2017; top row, left, the “de Ganay” Salvator Mundi which was proposed in 1982 (unsuccessfully) as the original Leonardo prototype painting; the Wenceslaus Hollar 1650 etched copy of a painting then believed to be Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi. Both candidate paintings were said to have been the subject of Hollar’s copy.

A CONFIDENTIAL INVITATION TO A SELECT COMPANY OF SCHOLARS

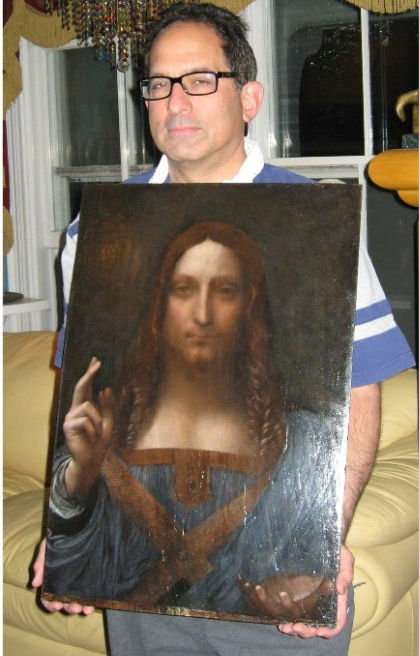

In March 2008 Martin Kemp was invited by the then new director of the National Gallery, Nicholas Penny, to join a small and select group of scholars to examine the Salvator Mundi painting – “We are only inviting two or three scholars”. The invitation was accompanied by the disclosure that scholars at the National Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, were already “convinced that it is Leonardo’s original version”. Kemp responded immediately to the picture’s “vibration” and the extent to which “Signs of Leonardo’s magic asserted themselves.” He warmed to the New York art dealer, Robert Simon, “the custodian of the picture (whom I later discovered was its co-owner)…All I knew at this stage was that it was being represented by Robert Simon. He told me it was in the hands of a ‘good owner’ who intended to do the right thing by it, and I did not inquire further…” Kemp decided to research “every aspect of the Salvator Mundi” which had “seemed at first sight to resonate deeply with key aspects of Leonardo’s science of art and his views of the cosmos.” In 2019 Simon said of that National Gallery meeting: “Attribution seemed not to be an issue. There was no debate.” He further discloses that even as Penny was sending his invitations to the non-debating examination (- which occasion Ben Lewis has fleshed out admirably in his 2019 The Last Leonardo), he had dispatched Luke Syson, the National Gallery curator of its forthcoming Leonardo show, to New York, to view the Simon-fronted Salvator. Kemp reports that shortly before the 15 November 2017 sale of the Salvator Mundi at Christie’s, New York, “I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.”

THE DISCOVERED OPTICS OF TRANSPARENT GLOBES

It is better practice for scholars to report what artists did do than to pronounce on what they would not have done. In his 2018 Living with Leonardo account, Kemp implies that he swiftly shifted position on the orb’s refractions during his theoretical journey on optics. In truth he had abandoned one position and adopted its antithesis. He recalls his early 2008 flush of excitement: “The most satisfying facet of my own research concerned my hunch that the globe was made of rock crystal…I had toyed with the idea that the double image of the heel of Christ’s right hand visible through the sphere might be the result of a double refraction characteristic of rock crystal; but the optics would not work. The apparent doubling is almost certainly another pentimento.” In 2018 (and therefore when speaking from his later adjusted position) Kemp advised:

“We should remember that Leonardo was drawing on his knowledge of rock crystal to devise a large sphere for Christ to hold – he was not making a ‘portrait’ of an actual sphere, nor was he following all its optical consequences to their logical conclusions. I have been asked on more than one occasion why the drapery behind the sphere is so little affected by what is, in effect, a large magnifying lens. The answer, in a word, is decorum; that is to say, pictorial good manners…Leonardo’s paintings remake nature – not only in accordance with natural law, but also in obedience to the rules that govern functioning images. He would not have disrupted the efficacy of the painting as a devotional image.”

His enthusiastic researches grew fast: “By early November 2008 I had a substantial essay of more than 8,000 words in draft, albeit with more research to conduct. The draft expanded as months went by. At one point it was entitled ‘New Wine in an Old Bottle’, to acknowledge that Leonardo had endowed a very traditional format with radically new features.”

THE NOVEMBER 2011 NATURE MAGAZINE (- “Art history: Sight and salvation”)

Those researches had been earmarked for a book of essays to be published by Yale University Press and sold at the National Gallery’s 2011-12 blockbuster exhibition, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan”. When that book failed to materialise Kemp, ever media-savvy, “turned to outlets that would deliver in time for the opening of the exhibition – not for the full research, but to get across some key points. The outlet over which I had most control was the regular column I was then writing in the science magazine Nature. There was enough science in the topic to justify the inclusion: not only the fruits of the scientific examination, but also Leonardo’s optical ingenuities and the cosmology of the crystalline sphere. The essay appeared on 10 November [2011], one day after the opening of the show.”

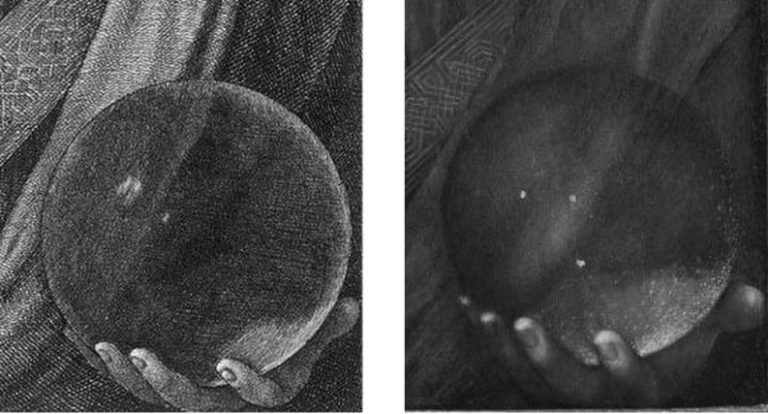

At that date Kemp was still holding to his initially gratifying hypothesis of materially refracted images petrified within the depicted crystal orb. In the November 2011 Nature, he specifically noted: “It seems that he [the artist] observed the double refraction produced by calcite. The heel of Christ’s hand exhibits two distinct contours, not in this case due to a change of mind.” Thus, three years on, Kemp was still “toying” with the idea that the orb depicted naturally generated refractions at the moment when the National Gallery exhibition opened and after the publication of its catalogue. What would induce an abandonment of that position? For that matter, why did the hand, as seen through the globe, change between 2011-12, when at the National Gallery, and 2017, when about to be sold by Christie’s, New York? (See Fig. 5, below).

THE BIG FLIP AND A PROVENANCE DAISY-CHAIN

Two days after publication of Kemp’s article the Times published our first intervention in which we noted that in 1650 Wenceslaus Hollar had copied refractions in the drapery seen through the orb in a painting believed at the time to be by Leonardo (see above, left, Fig. 2). Neither Kemp nor the National Gallery responded to the letter even though this optical discrepancy carried lethal provenance implications for the National Gallery’s (mysteriously owned) then-attributed Leonardo Salvator Mundi: if that painting showed no such deflected drapery, it could not have been the version copied by Hollar, as was claimed in the exhibition catalogue entry by its National Gallery curator, Luke Syson, (albeit on the borrowed researches of Robert Simon, who in turn had drawn on the not always substantiated researches of Joanne Snow-Smith who, in 1982, had proposed another Leonardo school variant – the “de Ganay” picture, top left, Fig. 1 above – as the original prototype painting). If the Simon-fronted Salvator had not been copied by Hollar then there could be no claims of English or French royal connections and, in consequence, there would be no record of the painting before 1900, when it entered the Cook Collection in England – from which collection it would be sold in 1958 for £45…to be picked up by Simon and Co. in the USA for $1,175 in 2005. In short, the Gallery had no historical support for its claim that this was a “lost” original autograph prototype painting for the very many and various Salvator Mundi paintings generated within Leonardo’s school.

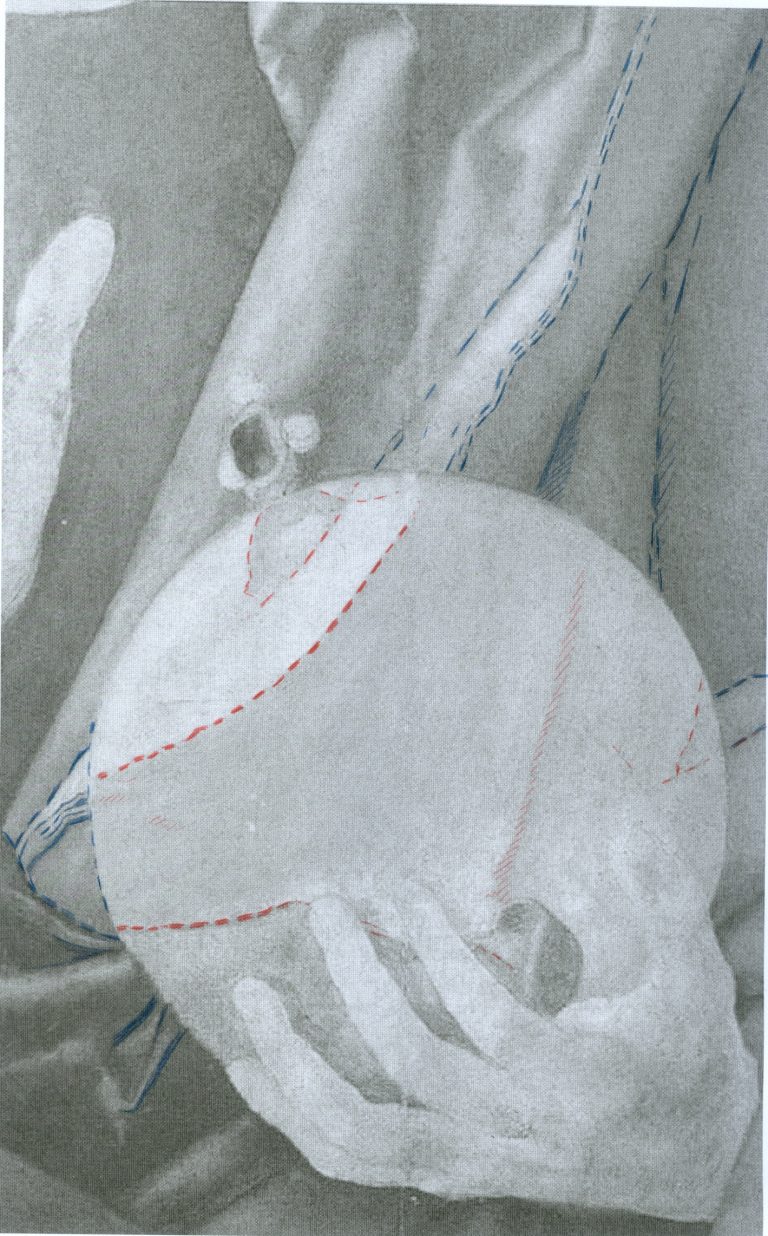

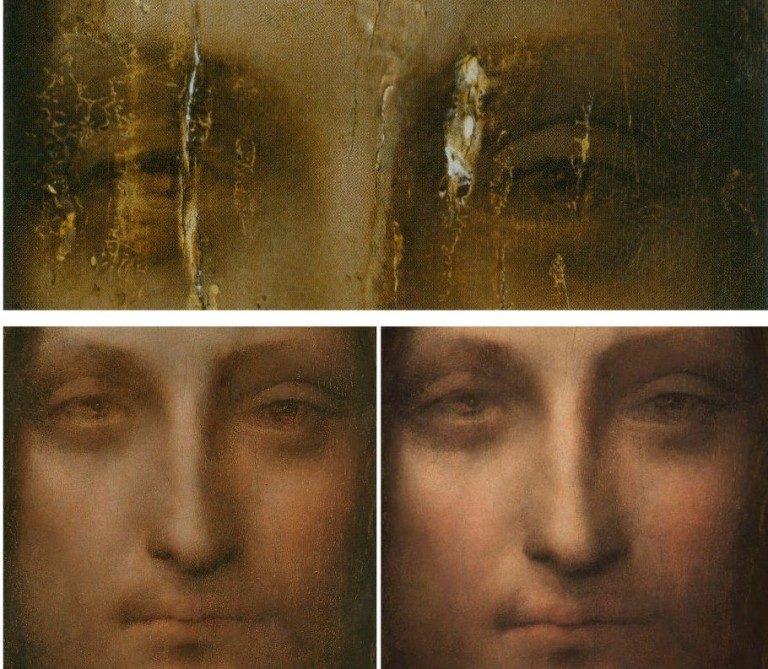

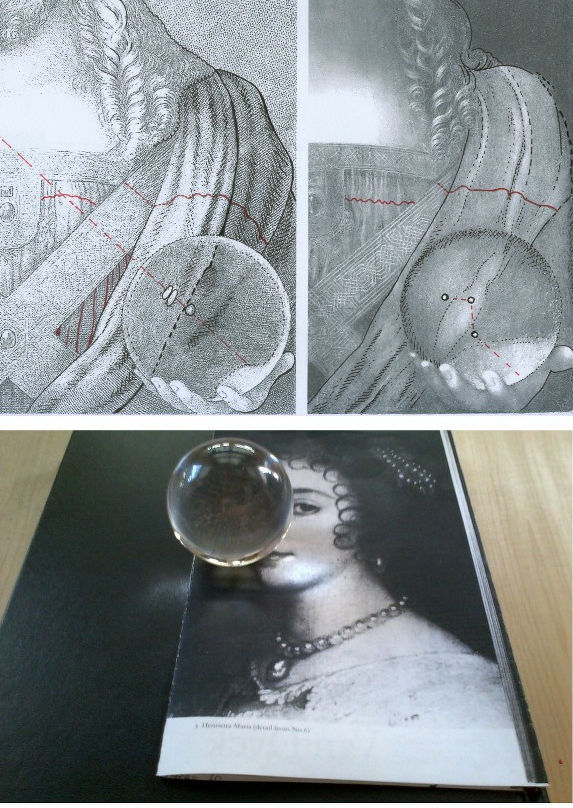

Above, Fig. 3: Left, a detail of Wenceslaus Hollar’s copy showing refractions of drapery seen through the orb; right, a detail of the Salvator Mundi painting showing no refractions of drapery. This image shows the painting not as when exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12 but as when offered for sale in 2017 after further (covert) restoration carried out at New York University. Note here the radically different depictions of the hands holding the orb and the way light had accumulated around the circumference in Hollar’s orb.

Although our letter elicited no response, in the next issue of Nature, Kemp’s comments on the orb’s optical properties came under explicit technical challenge. On 21 December 2011, five weeks into the exhibition, Nature published an exchange between Professor Kemp and a Dutch scientist, André J. Noest, who rejected Kemp’s claim that the double contour of the heel of the hand was the product of a double refraction within a calcite orb and did so precisely on the grounds that: “The painting shows no optical distortions in the folds of the clothes, for example, as would be expected from refraction by an orb of calcite, quartz or glass, or even a water-filled glass vessel.” Moreover, “The double contour of the hand continues slightly outside the orb, hence it could be due to a previous stage of the painting, or pentimento. The absence of refraction or reflection effects suggests that the orb depicts an idealised celestial sphere, with the painted specks on its surface representing heavenly bodies.”

Kemp immediately caved: “As far as we can tell, given the damage to the Salvator Mundi, the garments behind the sphere are indeed undistorted”. While so-saying he again made no reference to the contrary testimony of Hollar’s copy, even though, on 10 November 2011, he had written:

“The second variety of ‘scientific’ evidence is particular to Leonardo. He insisted that painting is a science — it relies on a systematic body of knowledge based on a deep scrutiny of cause and effect in nature. He saw painting as ‘the sole imitator of all the manifest works of nature … which with philosophical and subtle speculation considers all manner of forms … all of which are enveloped in ‘light and shade’. For any painting to be recognized as a Leonardo, it has to bear witness to such mighty ambitions. The Salvator Mundi, he held, “does so on two main optical counts…” One count was:

“The other optical effect is unique to this painting, both in Leonardo’s work and in the Renaissance more generally. The orb is not the standard globe of the world. It is translucent and glistens internally with little points of light. These are not the spherical bubbles found in glass, but are the kind of cavity inclusions (small gaps) that appear in some specimens of rock crystal and calcite. Leonardo, we know, was considered an expert in such semi-precious materials. It seems that he observed the double refraction produced by calcite. The heel of Christ’s hand exhibits two distinct contours, not in this case due to a change of mind. (Emphasis added.)

KEMP’S DISCUSSION OF THE ORB’S OPTICAL PROPERTIES

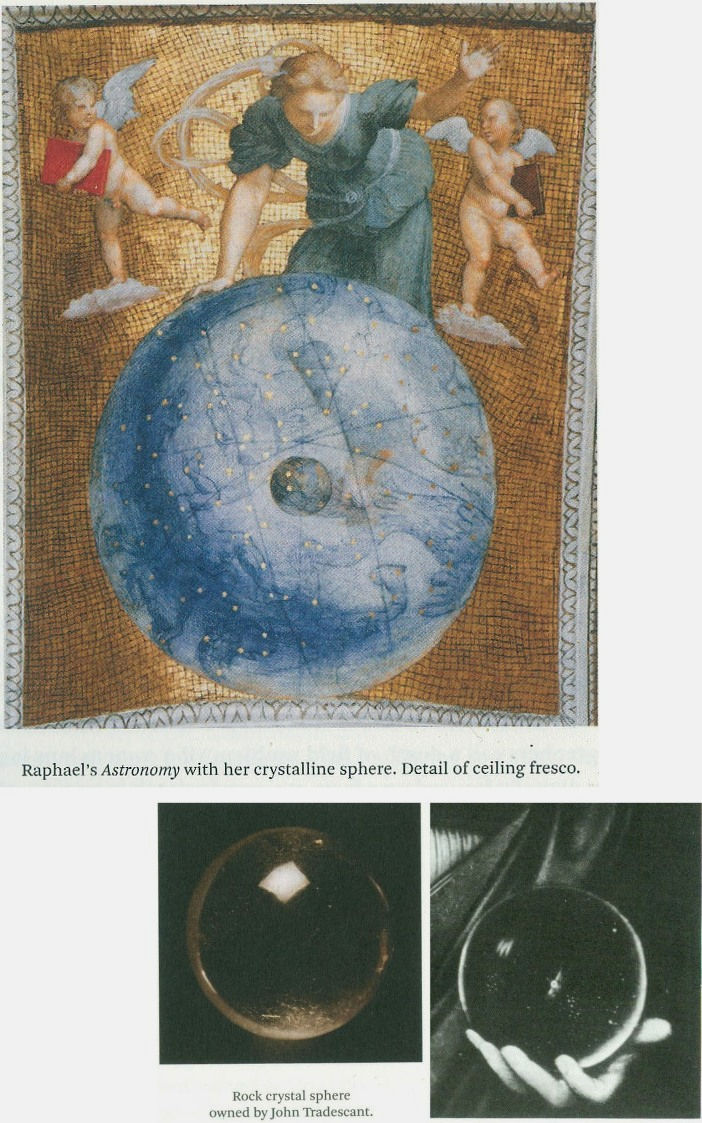

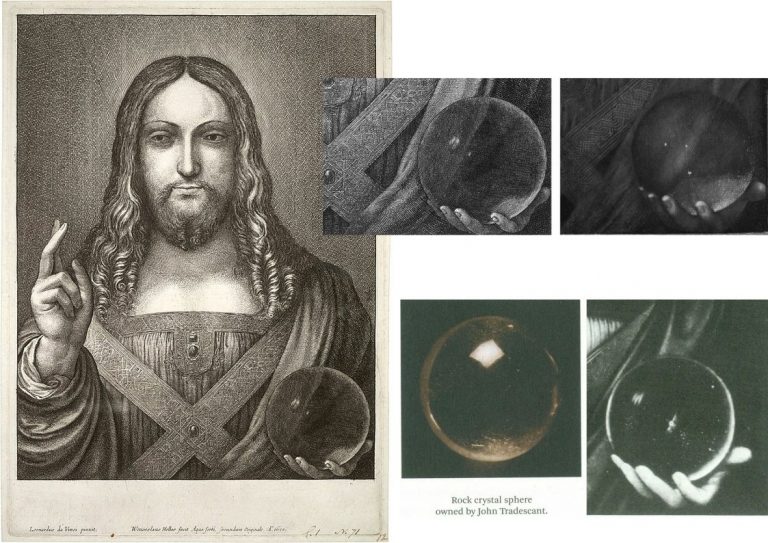

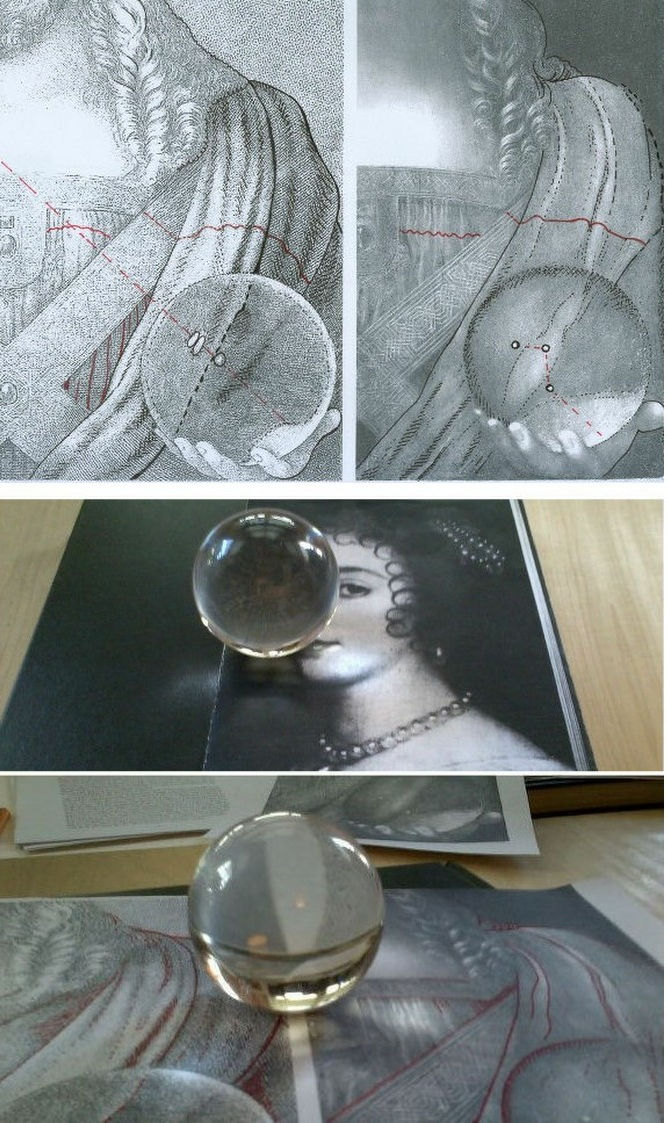

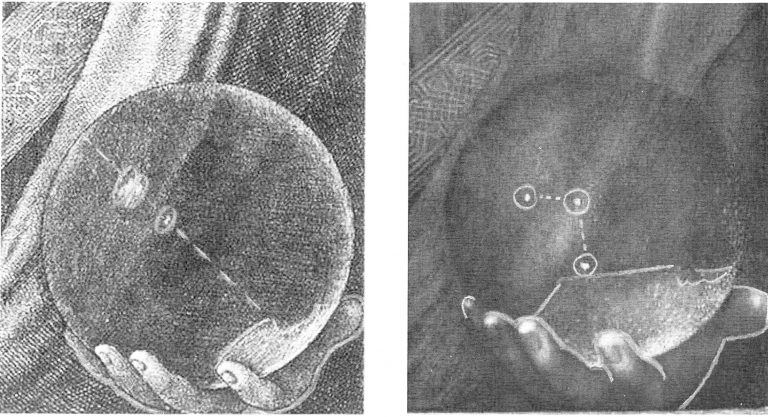

In 2018 in his memoir Living with Leonardo, Kemp reproduced just two images of orbs, as above, Fig. 4, top and centre, and wrote: “I had toyed with the idea that the double image of the heel of Christ’s right hand visible through the sphere might be a double refraction characteristic of rock crystal but the optics would not work. The apparent doubling is almost certainly another pentimento.” Again, he made no acknowledgement of Hollar’s testimony. Nor did he address the striking similarities of the Tradescant orb, as he photographed it, with that copied by Hollar and that encountered in the Worsey picture (Fig. 4, above, bottom right). Similarly, he later declined to address the differences evident in the orb between 2012 when it left the National Gallery and 2017 when offered at Christies – see Fig. 5 below:

BODIES OF COMPARATIVE VISUAL EVIDENCE

None of the many Leonardo school Salvators shows the hand in the massive and double-edged manner of the now-disappeared version (as above at Fig. 5). Just as the illumination seen in Hollar’s orb, Fig. 6, below, left and top, is strikingly similar to that seen in the lost Worsey picture’s orb, so too in both images the hand holding the orb is shown distorted and compressed towards the orb’s circumference.

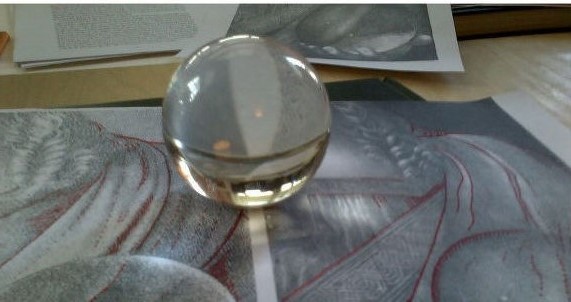

While Kemp seems proud to have been the first to suggest a rock crystal orb, an orb’s material composition is of little artistic consequence in terms of its capacity to distort. Our small solid glass orb shown below at Fig. 7, demonstrates in the lower image how, when an orb straddles a parallel gap between two pictures, that gap is shown (inverted) at the top of the globe as two curved, not straight lines.

EARLY AND CONTEMPORARY ORBS

Kemp’s claim that sensationalising critics make it difficult to conduct a duly “sober and systematic analysis of primary sources” seems rich. So far as we know, he has never addressed Ludwig Heydenreich’s groundbreaking 1964 study of the many Salvator Mundi pictures produced by Leonardo’s school and followers. (We published all of Heydenreich’s illustrations – including that of the lost “Worsey Collection” picture – the day before Christie’s sold the disappeared Salvator Mundi for $450 million – see “Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”.)

Kemp praises Robert Simon’s researches: “He assembled a large bank of research images, including a growing number of copies or variants which testified to the hold that Leonardo’s inventions exercised on other artists and patrons.” In the long-promised Margaret Dalivalle, Martin Kemp and Robert B. Simon book Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi, Simon acknowledges Heydenreich’s work as “The most significant publication on the subject” and “an excellent introduction to the subject”. Further he acknowledges that Heydenreich had concluded, on the very great variations present in the works, that no autograph Leonardo painting had been produced. At the same time Simon describes the Salvator Mundi, as “One of three lost paintings by Leonardo known from copies”. What had changed since Heydenreich? Simon’s researches had identified “several more painted versions and variants”, but none was considered to have approached “the quality of our painting”. In that case, the logical/stylistic problem strengthened: where bona fide Leonardo paintings exist, all copies, however variously talented their authors, can be seen to sing from a single design sheet. In this case, the more anarchically various works emerge, the less plausible they become as supposed copies of a single autograph work.

No case – and even less any visually-comparative case – has been compiled to show the Simon and Co. painting had served as a prototype for all versions. Simon tacitly concedes this methodological lapse when saying: “this image of Christ was more of a curiosity, since relatively few versions of the Salvator Mundi composition were known and, unlike copies of the Mona Lisa, there was little consistency in the details among them; each seemed almost an interpretation of the subject rather than a faithful reproduction of a common original.” That central problem persists at macro and micro levels: if Leonardo had painted a large hand with a horizontal thumb, the tip of which was cropped by a pre-fixed frame, why did no other painting echo or follow his example? In his catalogue entry, Luke Syson says of this hand that-no-one-copied, that although it is seen through a crystal orb, “Christ’s hand seems miraculously undistorted” and that “Leonardo has therefore created an object which would be understood as a piece of divine craftsmenship, but still be his own invention.”

Kemp had checked in the photographic library of the Warburg Institute to see what other artists had made of the orb in Salvator images: “There was quite a variety. Brass globes were common, sometimes with a cross on top. Some took the form of terrestrial globes with indications of land and seas. Others were made of glass, and a few contained little landscape vistas. In two Venetian examples Christ placed his hand on an ample glass orb – appropriately enough, given Venice’s pre-eminence in glass manufacture. But none seemed to show a crystal sphere.”

Much as Kemp hugs the especial qualities of crystal, with regard to the supposed prohibition against artists indicating refractions within transparent orbs (on grounds of propriety and decorum) the nature of the material – glass, crystal or quartz – is immaterial: if an orb gives rise to spherically-determined distortions it gives rise to spherically-determined distortions. (The mention of Venetian glass-making skills might be considered germane to this subject.) This attribution was made on a manifestly incomplete programme of studies: every time Kemp explains absences of refraction on the Simon Salvator by invoking “decorum” and “pictorial good manners” he ignores the testimony of Hollar who had copied defractions on a painting then judged to by Leonardo in 1650. Those deflections on that carefully dated 1650 etching are both material and historic facts. Where is that painting? Had Liz James’ splendid and technically illuminating 2017 book Mosaics in the Medieval World been published earlier, Kemp might have appreciated that even devout Byzantine mosaic-makers had no qualms about depicting refractions within Celestial Globes.

TRANSPARENT ORBS FROM BYZANTIUM TO DURER

Above, Fig. 8: Left, The Archangel Gabriel, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, ninth century; top, an apse mosaic depicting the Mother of God and her Child and the archangels Michael (left) and Gabriel at the sixth century Church of the Panagia Angeloktistos, Kiti, Cyprus.

Above, Fig. 9: the orb held by the Archangel Gabriel at Hagia Sophia.

Concerning decorum, how would Kemp account for the above Byzantine mosaic image of a transparent orb held by the archangel Gabriel in which the thumb and part of the supporting hand are visible through the orb; in which a deflected image of the gold sleeve is present; and in which the straight-edged, vertical feathers of Gabriel’s wing have been rotated horizontally and given wavy form when viewed within the orb? In the two sixth century orbs below at Fig. 10, as held respectively by the archangels Michael and Gabriel, four fingers are shown through the orb in the one and the thumb and part of the hand in the other. Has consideration been made of the longevity of depictions of transparent orbs in sacred Christian images?

In Fig. 11, above, we see part of Durer’s (unfinished) Salvator Mundi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Have Simon and Kemp – not to mention the Met’s own declared curatorial and conservation supporters of the attribution – not considered the possible relationships between the two great contemporary artists, Leonardo and Durer?

In Fig. 12, we see that Durer showed defractions of drapery within his transparent orb. Was he aware before 1505 of such a usage in Leonardo? Was Leonardo aware of Durer’s depiction? Was this (then-in-progress work) one of the panels Durer is known to have taken to Venice in 1505? Could Leonardo have known of this incomplete, in effect, part-coloured drawing of a Salvator Mundi with a large refractions-generating transparent orb?

Regarding Fig. 13, above, how should we consider the coincidences between Durer’s Salvator Mundi of 1505 and Hollar’s 1650 copy made in Antwerp after a Salvator Mundi then said to be by Leonardo?

Above, Fig. 14: The compilation of three hands above highlights the paucity of scholarship that accompanied the sustained and effectively covert drive to have the Simon and Co. Salvator Mundi accepted in the 2011 National Gallery exhibition as an autograph Leonardo. Ben Lewis has established that the hand on the right is found on a Salvator Mundi painting now given to Giampietrino. It lives in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow, and is incontrovertibly the Salvator Mundi that was once in Charles I’s collection, where it was given to Leonardo. Simon, Kemp and others have held that “their” Salvator Mundi was that recorded Charles I painting and that it had been copied by Hollar almost a century and a half later. Self-evidently the Pushkin Salvator cannot have been copied by Hollar because it is an entirely different – and more obviously Leonardo-like – compositional type. Without anticipating Jacques Franck’s forthcoming comments on the mis-drawn hand in the centre above, we can surely see here that in 1505 Durer and, perhaps a little later, Leonardo’s student Giampietrino had both made a better fist of drawing a Blessing Hand than had the Master of the Simon/Kemp and others’ Salvator Mundi?

Michael Daley, Director, 5 February 2020

UPDATE – 11 February 2020:

Collective Failures of Due Scholarly Diligence and Visual Acuity

Following publication of the above post some contend that the former Cook Collection Salvator Mundi painting failed to leave New York after the 15 November 2017 sale because the successful bidder declined to pay in full; and, two further Byzantine orbs showing refracted draperies have emerged, as shown and discussed below. While the monumental mystery of this painting’s whereabouts constitutes a globally shared preoccupation, it is not the essential professional concern in this affair. Before auctioneers entered the scene, a seemingly self-selecting group of international scholars by-passed all means of open appraisal, contention and debate – and then disparaged all subsequent critics. In our view, the magnitude of this particular visual misreading by a group of leading art historical figures rivals that encountered forty years ago on the restoration of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes.

Above, Fig. 15: The historical sequence of previously un-noted transparent orbs showing refracted drapery grows. A correspondent suggests that the orb encountered on the 14th Century icon of the Archangel Michael in the Byzantine & Christian Museum in Athens (as above, top centre, and below at Fig. 16) might have been known to Leonardo. If that seems unlikely – the Athens museum links the icon to a mural cycle of 1315-1320 in a Constantinople monastery – certainly, its existence might not have been expected to elude scholars today who enjoy full access to university libraries and the internet. An earlier German picture, the Athenaeum’s 1514 Coronation of the Virgin by Hans Süss von Kulmbach (above) not only contains an orb showing refracted drapery but one that appears to float and cast a shadow on God the Father’s lap – here the hand seems to be holding the orb in place rather than supporting it. In his 1998 book On Reflection Jonathan Miller noted the anomalous reflections of a window on the orb and toyed with the thought that they might have carried an allegorical function by symbolising the idea that the universe itself is a church, but he added, “they do look like the windows in the artist’s studio”. Indeed, and the upper reflection appears even to show a safety catch. It might be thought inconceivable that Durer would not have known of this orb and its treatment: von Kulmbach being the former Durer apprentice who took over the production of his master’s altarpieces in 1510. Durer, who likely had designed this orb, could not have been indebted to Leonardo and his school on transparent orbs – which underlines the unaddressed question: were they apprised of the great German master’s earlier engagement with such orbs?

Above, Fig. 17: Of course, any scholar might overlook a particular historic work. The real professional lapse here lies in a group-failure to recognise the import of manifestly un-like images. For example (and as mentioned above) it was crucial to the recent campaign to upgrade the Cook Salvator Mundi that it be accepted as the one-time subject of Hollar’s 1650 etched copy of a Salvator Mundi painting then thought to have been painted by Leonardo. If we allow for the fact that even so good a copyist as Hollar might not be expected to reproduce faithfully every detail of a relatively large painting in small etching; and, even, if we make allowances for what are nowadays euphemistically described as paintings’ “conservation histories”, no visually alert expert professional should have believed that Hollar might have copied his orb/hand, as above left, from that found on the former-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi, as shown above, right. Given the scale on which Hollar worked, the challenge of perfectly reproducing the elaborate geometric knot-pattern decorations on the stole might seem like an invitation to fudge or dissemble but, in truth, we see that Hollar contrived, in-miniature, a complex geometric pattern that is remarkably close in spirit and appearance to that encountered on the Cook Leonardo school Salvator Mundi painting. Given that close correspondence, it is simply inconceivable that Hollar derived his image from the orb/hand present on the (now-disappeared) painting, as seen above right.

A CATALOGUE OF ERRORS AND MISSTEPS

Even when the originally claimed derivation was being announced by Luke Syson in the catalogue entry to the 2011-2012 National Gallery Leonardo blockbuster exhibition, certain reservations were declared. In this regard Syson’s entry itself constitutes a catalogue of art historical missteps. First, he holds that it had “always seemed likely” that Leonardo had painted such picture. In a footnote supporting his claim, Syson states that he was writing on the authority of a then-pending and more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others:

“I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be published in a forthcoming book.” That book notoriously did not materialise until 2019. It is titled Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & The Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts. In his introduction, Simon claims it to be “the first to treat the painting monographically.” Some monograph: Modestini’s contribution was dropped – as was that of Gutman. Thus, there is no horse’s-mouth account of the picture’s long and various campaigns of restoration and no technical reports are carried. As also mentioned above, Simon acknowledges that, on the historically most thorough examination of the available evidence, Professor Heydenreich had concluded that Leonardo had not painted a Salvator Mundi.

Ill-logic has stalked this Leonardo ascription. When discussing an earlier claim that Hollar’s etching had been made after a different Leonardo painting then being advocated as a Leonardo original, Syson sensibly notes that “Hollar might very well have been copying a copy.” He further admits that the combined facts of the Hollar copy and the many workshop painted copies do “not constitute proof that Leonardo painted a Salvator Mundi.” Syson even nods towards Heydenreich’s thesis: “it has sometimes been argued that [certain…] drawings might have formed the basis for one or more finished designs – perhaps cartoons – that he [Leonardo] made expressly to be copied by pupils but with no primary version by the master himself.” But then against that, and in emulation of Simon, Syson takes the stripped-down and re-painted former Cook Collection Salvator Mundi picture to constitute proof in itself that Leonardo had painted his own prototype for all other copies after all, and that this version comprises the now-supposed and claimed “lost” Leonardo: “The re-emergence of this picture cleaned and restored to reveal [sic] an autograph work by Leonardo, therefore comes as an extraordinary surprise.”

In part, the surprise to Syson stems from the fact that a correspondence between the Cook picture and the Hollar copy is not complete: “Though Hollar’s Christ is very slightly stouter and broader, the two images coincide almost exactly” even though “The draperies are just a little simplified and there is no glow of light around Christ’s head.” Among the listed similarities, “the knot-pattern ornament on Christ’s crossed stole and the border of his vestment are very similar indeed, a particularly important consideration given that this ornament is the aspect most susceptible to change in the different surviving versions.” Now, if the perceived similarities between the Hollar copy and the Cook picture count in the latter’s favour, does it not follow that their dissimilarities should be counted in the latter’s disfavour? It seems that this $64,000 (-in fact $450 million) question may never have been asked by those who formed an orderly queue to ascribe the much remodelled former Cook painting to Leonardo himself. In our view that apparent omission is the gravest and least explicable of all: in the visual arts generally and in the making of ascriptions particularly, differences, no less than similarities, are of the essence. We have itemised the many dissimilarities previously. In Fig. 18, below, we pare the question down to a single comparison of the Hollar and Cook globes so as to pose the simple question: if this comparative image below constituted a newspaper “Spot the differences” quiz, how many differences would you be able to identify? To make the question easier, we have outlined some of the more massive and glaring discrepancies in white chalk.

The pear-shaped Salvator Mundi

Things have gone very badly pear-shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. It took thirteen years to discover from whom and where the now much-restored painting had been bought in 2005. And it has now taken a full year for admission to emerge that the most expensive painting in the world dare not show its face; that this painting has been in hiding since sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 for $450 million. Further, key supporters of the picture are now falling out and moves may be afoot to condemn the restoration in order to protect the controversial Leonardo ascription.

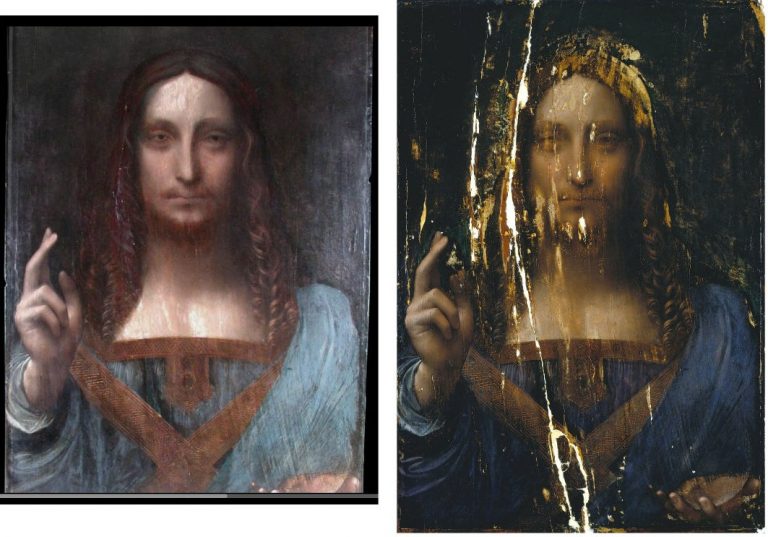

Above, Fig. 1: the Salvator Mundi in 2008 when part-restored and about to be taken by one of the dealer-owners, Robert Simon (featured) to the National Gallery, London, for a confidential viewing by a select group of Leonardo experts.

Above, Fig. 2: The Salvator Mundi, as it appeared when sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017.

THE SECOND SALVATOR MUNDI MYSTERY

The New York arts blogger Lee Rosenbaum (aka CultureGrrl) has performed great service by “Joining the many reporters who have tried to learn about the painting’s current status”. Rosenbaum lodged a pile of awkwardly direct inquiries; gained a remarkably frank and detailed response from the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini; and drew a thunderous collection of non-disclosures from everyone else. A full year after the most expensive painting in the world was sold, no one will say where it has been/is or when, if ever, it might next be seen. (See “Leonardo Canards: Conservator Dianne Modestini Debunks Doubts Over the Elusive ‘Salvator Mundi’”.)

After the Salvator Mundi’s recent no-show at Abu Dhabi Louvre, concerns and rumours have grown exponentially. (See our “Two developments in the no-show Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi saga” and “How the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi became a Leonardo-from-nowhere”.)

AN ENDURING SUPPORTER

Throughout this protracted no-show, Professor Martin Kemp, the most high profile art historical advocate of the painting’s Leonardo attribution, has offered assurances. Immediately ahead of the November 2017 sale he made a promotional video for Christie’s, New York, that was specifically designed to combat our and other warnings, warnings that he now characterizes in his self-valedictory memoir Living with Leonardo as “misinformation appearing in the press”. The Times reported on 28 August: “‘looking at the whole science’ including the rock crystal sphere that Christ was holding and the depth of field convinced [Kemp, that] ‘with Leonardo you have this wonderful body of context, of extra evidence…it is rock solid, it is damaged but rock solid’.” Kemp frequently fuses appeals to rock solid scientific evidence with art critical hyperbole. For example, to the owner of the supposed Leonardo drawing “La Bella Principessa”, he said of a partial finger print:

“This is yet one more component of what is as consistent a body of evidence as I have ever seen. I will be happy to emphasize that we have something as close to an open and shut case as is ever likely with an attribution of a previously unknown work to a major master. As you know, I was hugely sceptical at first, as one needs to be in the Leonardo jungle, but now I do not have the slightest doubt that we are dealing with a work of great beauty and originality that contributes something special to Leonardo’s oeuvre. It deserves to be in the public domain.”

So far as we know, that supposed Leonardo drawing (which the National Gallery excluded from its 2011-12 Leonardo show) remains unsold in one of Yves Bouvier’s freeports. Kemp recently assured the world that wonderful things are in train for the Salvator Mundi next year. Against his bullishness, the picture’s long-serving restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini, has now disclosed to Rosenbaum: “I have no idea about the future of the painting. No one does. Not the French, not Martin Kemp. I assume the people from Abu Dhabi know something, but they are not talking to anyone, not even the French.”

Rosenbaum had tried the Louvre, Paris:

“I thought the venerable French museum would at least be able to answer my question regarding its own exhibition plans, but Sophie Grange of the Louvre’s press office said only this: ‘It is too early, one year ahead, to communicate on the list of the loans for the Louvre exhibition. Concerning Louvre Abu Dhabi, they communicate themselves about their own collection.’ Grange advised me to get in touch with Faisal Al Dhahri at Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism—one of the three officials whom I’d already attempted to contact several times, to no avail. I think this is called: ‘Getting the Run-Around.’”

THE GOOD THINGS TO COME

Kemp may have had in mind the forthcoming 2019 Louvre exhibition to mark the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death but no one at the Paris Louvre will now confirm that the Abu Dhabi Louvre Salvator Mundi will be included. Is Paris about to spurn Abu Dhabi’s $450 million acquisition? Failure to include the work next year would risk humiliating the United Arab Emirates (who paid something like Euros 400 million for the right to exploit the Louvre title – roughly the cost of one big yacht) when French foreign policy dictates every deployment of soft cultural power to gain influence in that traditionally Anglophile quarter.

…AND THE UNKOWN UNKNOWNS

Why are so many players so silent on this painting? Why is the art world being kept in this state of darkening paralysis? Some background might help explain the jitters. The art market greatly fears the pending trial in New York between Sotheby’s and the Russian collector Dmitry Rybolovlev who seeks $380 million from the auction house for an alleged conspiracy to defraud him through his own adviser, Yves Bouvier. In 2013 Sotheby’s brokered a private sale of the Salvator Mundi for $80 million to Bouvier, the owner of a string of “tax-efficient” freeports – his Geneva facility alone reputedly holds $100 billion of art. The consortium of vendors claimed that a non-disclosure agreement made with Sotheby’s preventing them from disclosing the picture’s origins. Bouvier immediately sold the painting on (“flipped” in art trade parlance) to Rybolovlev for $127.5 million – an undisclosed mark-up of $47.5 million, with Sotheby’s, reportedly, pocketing $3 million as an agent’s fee. The Swiss police authorities recently detained Rybolovlev for questioning due to “reported allegations of corruption and ‘influence peddling.’ Rybolovlev is allegedly tied to Philippe Narmino, the former justice minister in Monaco, who retired last year after he was accused of working under the influence of the Russian collector in his fraud case against Bouvier…” Earlier, Rybolovlev had filed a complaint against Bouvier in Monaco. The latter was arrested on charges of fraud and money laundering and released on $10 million bail. Bouvier is now reported to be in Singapore. With Rybolovlev furious at being over-charged in 2013, the consortium of vendors who sold indirectly to him for $80 million are thought to remain aggrieved at being short-changed by $47.5 million on the picture’s value and having been pre-emptively blocked from action by a Sotheby’s law suit. Sotheby’s are reportedly seeking assistance from Christie’s in a separate legal fight with a dealer over the sale of a demonstrably and now scientifically-confirmed fake Frans Hals…

THE ART AND ATTRIBUTION STAKES

Unsavory art market churning must not swamp the serious art and attribution concerns at stake with this Salvator Mundi. Modestini’s reported statement to Rosenbaum merits close reading. Her first concerns are the painting’s physical condition, well-being and whereabouts:

“It’s supposed to have been in Switzerland, but I’m not quite convinced, because a conservator who was asked to make a condition report more than a month ago still hadn’t seen it as of last Monday [22 Oct. 2018]. I’m rather worried because although it was framed in a microclimate, it is not a long-term solution. I’m pretty sure it left Christie’s in mid-May. Then it disappeared. It never went to Abu Dhabi… However, the panel is badly damaged and exceptionally reactive to changes in RH [relative humidity]. It needs to be at not less than 45% RH, even though it has some protection because it’s in a microclimate created by sealing it up in an envelope of Marvelseal —a standard technique.”

Modestini’s second concern is professional and personal:

“The Abu Dhabi announcement [that it had postponed display of the painting] had nothing to do with the nonsense about its being 85% by Dianne Modestini and the rest by [Bernardino] Luini. [The Luini theory, advanced by Leonardo scholar Matthew Landrus, was reported by Dalya Alberge in the Guardian and picked up by Smithsonian Magazine, among others.]”

Above, Fig. 3: Left, the Salvator Mundi as restored in 2008; right, a National Gallery painting attributed to Bernardino Luini.

A GREAT FALL-OUT?

It is understandable that Modestini should be sensitive and defensive – no professionally conscientious person enjoys criticism. Following our demonstrations of the extent to which the painting changed appearances at her hand (albeit on the advice of and with support from a high-ranking group of art historical experts) between 2005 and 2017, there are now signs that art historical advocates of the Salvator Mundi may be preparing to disavow the successive restorations to protect the credibility of their attribution. Consider Jonathan Jones’ recent (15 October) account in the Guardian – “The Da Vinci mystery: why is his $450m masterpiece really being kept under wraps?”

Jones, who was the embedded journalist-of-choice within the National Gallery’s conservation department when its version of the Virgin of the Rocks was being restored, bluntly contends that it might have been better if the Salvator Mundi had not been restored at all:

“Surely it would have been more true to the greatest artist who ever lived to let his timeworn masterpiece speak to us directly. Is the Louvre Abu Dhabi taking a closer look? I think it should.”

In this maneuvre, Jones seems to draw support from Martin Kemp, who, along with a few other select experts, had been invited by the National Gallery’s incoming director, Nicholas Penny, to the confidential 2008 viewing of the Salvator Mundi when part repainted, as at Fig. 1:

“When the painting was cleaned, it turned out that Christ had two right thumbs… ‘Both thumbs,’ says Kemp of the raw state, ‘are rather better than the one painted by Dianne.’”

Kemp will likely have known that Modestini had painted out the restoration-exposed second thumb on the advice of Luke Syson, the curator of the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition in which Kemp had been set to have some curatorial input until, as he puts it: “it was later decided that all the curation should be conducted in-house”. Modestini acknowledged Syson’s guidance in her (2014) published account of her restorations preceding the painting’s appearance in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition. Syson, who went to the Metropolitan Musem, New York, has recently been appointed director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. It is possible that had Kemp been co-curator, the National Gallery Leonardo show would have included a second Kemp-supported Leonardo upgrade, the “La Bella Principessa” drawing. In any event, an emboldened Jones has now challenged Robert Simon, one of the original consortium of dealer-owners: “Why didn’t he leave the painting in its raw yet beautiful state after it was stripped down? Wasn’t that an incredible object in itself?” Simon stood firm:

“We considered leaving it, considered more limited restoration, as well as a more extensive one…In the end we decided to do what we felt was best for the picture…we felt that bringing it back to life as much as possible was the way to go.”

Jones reports Simon’s annoyance with criticisms of the restoration – he absolutely rejects the possibility of any artistic “falsehood” being introduced. “I found [Thomas Campbell’s] comments both ill-informed and offensive. ‘Inpainting’ is the right way to describe what has happened here – retouching restricted to areas of loss. In the restoration no original paint was covered.”

(When the picture was sold in November 2017 Thomas Campbell, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum, presciently tweeted that he hoped the anonymous buyer who had just paid $450m “understands conservation issues” and had “read the small print”.)

WHAT WAS DONE IN THE SALVATOR MUNDI RESTORATIONS

The claim never to have over-painted is universally asserted by restorers. While no code of restoration “ethics” sanctions painting over surviving original paint, the profession’s philosophical pieties constantly conflict with observable visual facts. We have previously shown that if you juxtapose halves of the two Salvator Mundi faces, as seen in 2011-12 at the National Gallery and at Christie’s in November 2017 (see Fig. 7 below), there is a mismatch: scarcely any passages of painting run across the halves. As the photo-records below testify, this version of the many Leonardesque Salvator Mundis has enjoyed two distinct identities in seven years and three in ten years. We discuss the unreported covert transition from the second to the third below.

DISPARAGING PHOTO-TESTIMONY

Modestini and Kemp are united on one point: both hold that restorers cannot be held to account by photo-comparisons of the alterations they make to works of art. The claim is untenable – how else might appraisals of restorations be made given that pre-restoration appearances are consumed in restorations? Both the restorer and the art historian further contend that photographs are inherently unreliable because susceptible to malicious manipulation. Modestini offers this variation on that ancient restoration slur:

“I have refrained from commenting on some of the recent articles about the restoration. However, in light of the fact that no one can now see the actual painting, various digital images are standing in for the original, all of which can be manipulated any way one wants and are a sort of falsification of the original.”

That is unworthy. First, why would anyone maliciously tamper with images to make false claims of non-existent injuries that could easily be exposed by the photographic record? How long did it take to expose the Trumpian White House’s tampering with film footage of a journalist’s attempt to retain a microphone? Second, does Modestini mean to imply that the clear photographically recorded differences between the painting’s 2011 and 2017 states are the combined result of malicious critics and auction house promotional manipulations? Modestini’s citation of the second plank of the traditional Restorers’ Defence – that all photographs of paintings are inherently untrustworthy and misleading – is scarcely more credible:

“It is very difficult to photograph any painting accurately, this one especially, because of the many thin layers, subtlety of skin tones, delicacy of transitions etc. Most paintings have three dimensions, not two. That affects our perception of them. I hardly recognize the image that now passes for the ‘Salvator Mundi.’ The photo lamps or strobes (in the case of the Christie’s images) produce a simulacrum of the actual painting, more vivid, sharper, snazzier, if you will, than the actual battered image that I restored as carefully as I could, trying not to invent anything. These flashy images cannot include the nuances and problems created by the three dimensionality of the corrugated surface and are being compared with an only slightly more accurate scan of a good 8×10 transparency of the cleaned state, which was more honest.”

That last image (here at Figs. 5-10) has been published with a drum roll by Jones in the Guardian as if a proof of Leonardo’s hand when it had been published by Modestini in 2014 (albeit small and in printed not online form). Although a considerable improvement on earlier versions (as published by us) it does not tell a different story. On the Jones premise, will Modestini now produce equally high-resolution photographs taken before and after each of her various interventions (2005-08; 2008-11; post 2012 and pre-2017)? If she insists that all photographs are inherently untrustworthy and easily falsifiable, will she explain why so many photographs of paintings are made and published and why they never carry visual health warnings? Are all photographs previously made for restorers’ own restoration reports now deemed to be unreliable testimony?

THE ART CRITICAL UNDERPINNING OF THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S CHANGING APPEARANCES

We incorporate below the Guardian’s newly released high definition photograph of the painting when cleaned but not-yet repainted within the public record of Modestini’s restorations and then consider Kemp’s scientific/art theoretical input into the restoration in the light of certain accounts in his new memoir, Living with Leonardo – Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond. But first, the changes to the painting:

Above, Fig. 4: Left, the photograph of the Salvator Mundi painting when in the Cook collection and judged to be a work of Bernardino Luini; right, the former Kuntz family and then Basil Clovis Hendry Sr. estate painting, as in the 2005 St. Charles Gallery catalogue.

Above, Fig. 5: Left, a screen grab of the Salvator Mundi as when taken, still sticky from a previous restoration in 2005 to Dianne Modestini’s New York studio; right as in 2007 in the newly released high-resolution photograph following cleaning and repairs to the panel but before any retouching, infilling or repainting. Will Modestini publish a photograph of the painting as presented to her in 2005?

Above, Fig. 6: Left, the Salvator Mundi as in 2006/7 (in high-resolution) after cleaning; right, as in 2011 as exhibited as a Leonardo at the National Gallery, London, and after much repainting – some of which was distressed and contained false, painted lines of cracking in emulation of aged paint cracks.

Above, Fig. 7: Left, the Salvator Mundi as in 2006/7 (in high-resolution) after cleaning; right, as in 2017 when sold at Christie’s, New York, after further covert restoration.

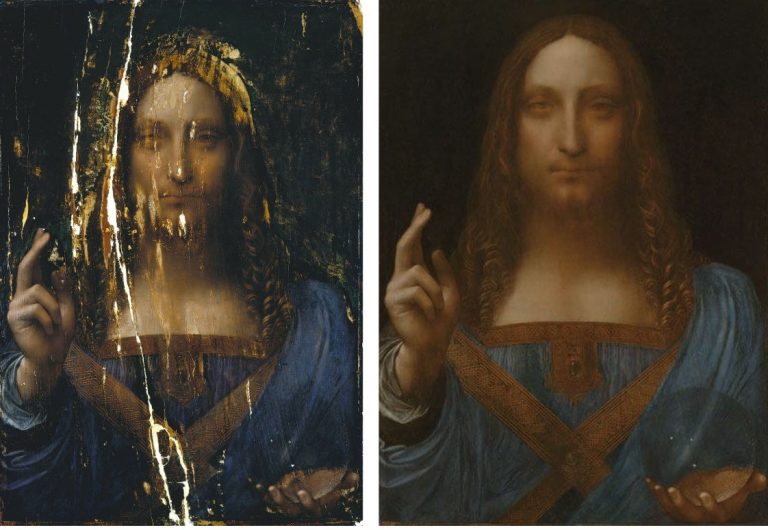

Above, Fig. 8: Left, the head of the Salvator Mundi as in 2006/7 (in high-resolution) after cleaning; right, the head in a split screen compilation showing the appearance in 2011 on the left and in 2017 on the right.

Above, Fig. 9: Top, a detail of the Salvator Mundi’s eyes as in 2006/7 after cleaning and before repainting (and as published by Modestini in 2014); above, left, the face, in 2011, and, right, as in 2017.

Above, Fig. 10: Top, a detail of the new high resolution photograph, as published online by the Guardian; centre, the corresponding detail as published by Modestini in 2014, the previously best detail of the cleaned and not-yet repainted eyes; above, eyes by Leonardo and Bronzino. The lower images are surely instructive here? The Salvator Mundi was hyped by Christie’s, New York, as an iconic thing – a “Male Mona Lisa”. Martin Kemp holds that it was painted by Leonardo after he had painted the Mona Lisa and that he had deliberately put the face “out of focus” so as create spiritual mysteriousness on the one hand and an illusion of spatial depth and recession in an emphatically flat (and heavily cropped composition) on the other. If we look at these images art critically we can safely make a number of factual, verifiable observations – and these are not “subjective”. First, although the high-resolution photograph is superior as a photograph to the lower resolution image, as published in a book, it does not tell a materially or artistically different story – in both we can see the extent of losses and the fact the treatment of the eyes is neither identical nor consistent. In particular we can see that the treatment of the heavy flattening upper eye lid on the right is sharply (and badly) drawn, while that on the left is softer and almost undoubtedly abraded. Modestini somehow equalized the effect of the eyes while leaving the implausible severity of drawing found in the lid of the eye on the right. Neither eye in this painting is remotely comparable with the Mona Lisa’s eyes where softness of effect has been achieved without loss of sculptural lucidity or anatomical veracity. These differences are ones of quality more than of style. The creases formed by the meeting of the soft flesh of the upper lids with the more taught flesh of the brow is more sharply drawn in the Bronzino but it is also drawn with greatly more acuity and finesse than the eye on the right of the Salvator Mundi. Much of the great benefit photography brings to art historical scholarship lies in the ease with which detailed style comparisons can be made. In an age of high quality and electronically transmissible photography, if you are going to claim Leonardo you really should take the opportunity to demonstrate Leonardo.

Above, Fig. 11: A succession showing the picture and two details, with the first each time, as in 2011 and, second, as in 2017. The question raised by Modestini is the extent to which the differences shown above are products of Christie’s own “more vivid, sharper, snazzier” images of the 2017 state or of her own repainting. It can safely be said that repainting must substantially account for the differences because changes have been made to the design of forms as can be seen here in the comparison of the details of the shoulder drapery. It would be helpful if all parties to the post 2005 “conservation treatments” would publish full accounts of them accompanied by the best available photo-records.

MARTIN KEMP’S THEORETICAL AND SCIENTIFIC INPUT

On the very day when the Salvator Mundi went on exhibition at the National Gallery (9 November 2011) Kemp published an article, “Art History: Sight and salvation” in Nature magazine. In it, he made a number of significant contentions/observations: 1) that although connoisseurship still has a role to play, it involves “subjective criteria that should long ago have been superseded as the key tool of attribution”; 2) that art historical evidence can be supplemented by “the scientific”, of which there are two kinds – technical examinations of pictures’ component material parts, and scientific evidence that is “particular to Leonardo”; 3) that the Salvator Mundi bears such witness in two regards: it “plays with depth-of-field problems. None of the contours is absolutely sharp, but the blessing hand and the tips of the fingers cradling the orb are discernibly clearer than the features of Christ’s face. The rapid lack of clarity in depth serves to give space to what would other-wise be a quite flat image.”

What is striking in the above series of comparisons is the extent to which Modestini has apparently added force and clarity to the hands and globe in the foreground. The globe, for example, has been emphatically darkened towards its circumference and lightened at its centre between 2011 and 2017. Modestini partially accounted for these changes in 2014: “The rock crystal orb, symbolizing the cosmos, was painted with practically nothing, thin glazes and scumbles which unfortunately have been abraded, especially along the top of the wood grain. Originally the illusion must have been magical since simply toning down the lighter areas with translucent watercolor glazes rendered it convincing.”

In Living with Leonardo Kemp discusses the two thumbs and, there, had praised Modestini’s “painstaking and diplomatic filling in of lost areas with readily soluble paint”. Kemp reports that after viewing the picture at the National Gallery in 2008 “Robert and I corresponded during the course of that summer and autumn.” There can be little doubt that differences between the painting’s appearance, when first taken to London (Fig. 1), and later in 2011 when exhibited in London (Fig. 2) are considerable. Even more dramatic are the differences between 2011 and 2017. The question, then, is under what or whose ambition or programme, were Modestini’s changes made? Was she and/or the owners in thrall to Kemp’s quasi-photographic depth-of-field thesis? We know from her own account that she made a number of artistic changes to the painting with a view to increasing spatial force:

“I repainted the large missing areas of in the upper parts of the painting with ivory black and a little cadmium red light, followed by a glaze of rich warm brown, then more black and vermilion. Between stages I distressed [how?] and then retouched the new paint to make it look antique. The new color freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair and made a different, altogether more powerful image.”

Note: these are only the changes that were made between 2007 and 2011. There has been no account of the subsequent restorations. If we look at the top of the split-image of the face at Fig. 8, we can see that the hair immediately to the right of the parting had become much darker by 2017 while the flesh tones in the forehead and nose had become lighter. No account of these changes has been published.

REFRACTIONS OR PENTIMENTI?

To return to Kemp’s 2011 Nature article, where he made this account:

“The other optical effect is unique to this painting, both in Leonardo’s work and in the Renaissance more generally. The orb is not the standard globe of the world. It is translucent and glistens internally with little points of light. These are not the spherical bubbles found in glass, but are the kind of cavity inclusions (small gaps) that appear in some specimens of rock crystal and calcite. Leonardo, we know, was considered an expert in such semi-precious materials. It seems that he observed the double refraction produced by calcite. The Heel of Christ’s hand exhibits two distinct contours, not in this case due to a change of mind.” [Emphasis added.]

That could not be clearer, could it? In Kemp’s characteristically adroit fusion of the technical and the spiritual, the superseding of traditional subjective practices of connoisseurship by newer, more astute technically and scientifically-informed analysis might seem well demonstrated – but how are such formulations to be evaluated? Must scholars without scientific backgrounds simply defer to the supposed superiority of science-loaded art historical scholarship – if told, on cited geological authority, that a material is so and so and, therefore uniquely gives rise to such and such effects, (that is, if calcite, then be on the lookout for its double refractions) who might query or dissent? Seven years later, in Living with Leonardo, Kemp retells his story on the significance of the orb and its near magical optical properties as a concrete embodiment of Leonardo’s mind, but with a twist: “The most satisfying aspect of my own research concerned my hunch that the globe was made of rock crystal”; he had “toyed with the idea that the double image of the heel of Christ’s right hand might be the result of the double refraction characteristic of rock crystal; but the optics would not work. The apparent doubling is almost certainly another pentimento [i. e. change of mind in the design – emphasis added].”

Thus, without a blush, Kemp offers a new diametrically opposite rationale: with this orb Leonardo “was not making a ‘portrait’ of an actual sphere, nor was he following all its optical consequences to their logical conclusions.”

Without mention of Hollar’s testimony, a pragmatic explanation is offered for an intellectual flip: “the optics” were put to the test and it was found by due and diligent research that they “would not work”. By “would not work” Kemp suggests that his efforts with a real crystal orb to replicate the kind of refraction he had earlier claimed to recognise in the double image of the hand holding the orb had been unsuccessful. But might there not have been another reason for dropping the earlier refracted hand thesis? As mentioned, Kemp’s Nature article appeared on the day the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition opened, 9 November 2011. On 11 November, a correspondent asked in the Times why no optical deflections were evident in Christ’s globe. The next day the Time’s carried our letter (Fig. 12, below) pointing out that in an etched copy by Wenceslaus Hollar of the original but now lost Leonardo Salvator Mundi the drapery seen through the orb had been deflected.

For the National Gallery this was politically awkward: if Hollar had copied an optically sophisticated, characteristically Leonardesque, effect from a painting then attributed to Leonardo that was not present in the painting on exhibition as the original Leonardo from which Hollar had made his copy, this could only mean that Hollar’s copy had, in fact, been made from another painting. Worse, on a careful visual reading of the relationships between the etching and the Salvator Mundi painting in the exhibition, there were further grounds for drawing the same conclusion: Hollar’s Christ was stouter and heavily bearded; his face was long and it tapered inwards from the level of the eyes, it did not widen, chipmunk-like towards the jaw; the eyes looked slightly to our left, not directly at the viewer; a radiant halo-like light emitted from Christ’s head; the transparent orb had gathered light around its circumference – and not grown darker, as in the painting…

This problematic visual mismatch must have compounded political problems: the gallery’s decision to exhibit a proposed Leonardo of little provenance and no art historical or technical literature and that was in the hands of a group of dealers (and therefore, inevitably, on the market) was institutionally questionable and certainly controversial. It became the more so when at least four Leonardo scholars challenged the attribution of the painting. Kemp, at that point, was hoist on his own scientific petard. Where the gallery had claimed in its catalogue entry on the painting that “There could be no doubt that this is the picture that was copied by Hollar”, it was now evident that it could not have been – and without that claimed connection, the picture’s supposed provenance collapsed from one in which it had passed down to us first through the French royal family in Leonardo’s day and then to the English royal family in the 17th century… to one that only began in England in 1900 when it had emerged from no acknowledged source, with no history and only as a painting given to Luini. How would the gallery respond to this very public correspondence and challenge? How would Professor Kemp respond? The National Gallery made no reply to the letters in the Times perhaps judging silence to be a better defence than open art critical engagement. Professor Kemp, too, was silent in the public prints, so far as we know.

Above, Fig. 12: Two ArtWatch UK letters to the Times.

Seven years later, while the National Gallery remains silent, Kemp, in Living with Leonardo, now writes with patronising verve and confidence to a new position:

“We should remember that Leonardo was drawing on his knowledge of rock crystal to devise a large sphere [the former ‘orb’ or ‘globe’] for Christ to hold – he was not making a ‘portrait’ of an actual sphere, nor was he following all of its optical consequences to their logical conclusion. I have been asked on more than one occasion why the drapery behind the sphere is so little affected by what is, in effect, a large magnifying lens. The answer, in a word, is decorum; that is to say, pictorial good manners…Leonardo’s endowing of Christ with a rock crystal sphere was not just a case of optical and geological cleverness for the sake of it…”

Perhaps not, but then why not introduce into the discussion the visual/artistic fact that Hollar had copied a deflection of curved forms of drapery when seen through a curved transparent body symbolising the cosmos? Would a copyist have invented an optical distortion in a painting he believed to be an autograph Leonardo? In journalism, as supposedly in science, facts are held sacred and opinions somewhat less so. Are awkward facts expendable in science-rich art history? Properly considered, Hollar’s testimony is an important event in the history of scientific engagement in art – just as it had been in Holbein’s use of an optic to correct the anamorphosis in the foreground skull of The Ambassadors in the National Gallery – as a scholar had proposed in the 1970s and I had corroborated in the 1990s. How long will such testimony remain institutionally and professionally un-personned?

SOME FURTHER UNADDRESSED, PHOTOGRAPHICALLY RECORDED ARTISTIC FACTS:

Above, Fig. 13: Left, a section of drapery in the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi when exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12; right the Modestini-changed section of drapery when sold at Christie’s New York in 2017.

Above, Fig. 14: Left, Hollar’s 1650 engraved copy of a Salvator Mundi attributed to Leonardo that shows deflected folds of drapery within the transparent orb; right, the Abu Dhabi Louvre Salvator Mundi as seen at the National Gallery at the time of the above correspondence in the Times. The double edge of the hand holding the orb had been left in place on the then Kempian view that it demonstrated Leonardo’s sophisticated optical knowledge. Had that double image been judged a pentimento it would, like that encountered on the thumb of the raised true right hand, likely have been painted out by Modestini on the advice of the National Gallery curator, Luke Syson.

Above, Fig. 15: Changes made to the Salvator Mundi’s orb and adjacent draperies as seen respectively (from left to right) in 2008, 2011 and 2017.

Above, Fig. 16: Left, the 1650 Wenceslaus Hollar etched copy of a Salvator Mundi painting; right, the Abu Dhabi Louvre Salvator Mundi, as seen in 2017 with changed draperies. In the Hollar we can how the central, highlighted fold of drapery is deflected from its convex path into a concave formation as it runs through the centre of the orb and between the aligned double and single light reflections. We can see how the heel of the copied hand was smaller and deflected towards the circumference of the orb; right, in the Louvre Abu Dhabi painting (third state) we can see how Modestini had darkened the circumference of the orb and brightened the interior. It is simply inconceivable that as skilled a copyist as Hollar could have drawn his orb from this, now Louvre Abu Dhabi painting.

Above, Fig. 17: Top, two diagrams showing differences of design and modeling between the 1650 Hollar copy, left, and, right, the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as sold in 2017. The three reflected highlights in the Hollar orb are aligned in accord with the picture’s top-left down light source which is evident throughout the painting that Hollar copied. The three unaligned white spots in the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture were attributed by Modestini to “reflections on the sphere to an outside source, but since many of the original glazes have perished, even when toned down, they float with context.” Above, a glass sphere owned by the author that shows the pushing of light towards the circumference, as copied by Hollar.

Above, Fig. 18: The author’s glass sphere. Where Martin Kemp failed to locate a double refraction in a small rock crystal orb, we demonstrated, as above, that when parallel straight lines (as here in the white gap between two photocopy diagrams) are viewed through a glass orb they are deflected into curves.

THE HOLLAR GLOBE’S BETTER FIT WITH THAT FOUND IN THE DE GANAY SALVATOR MUNDI<

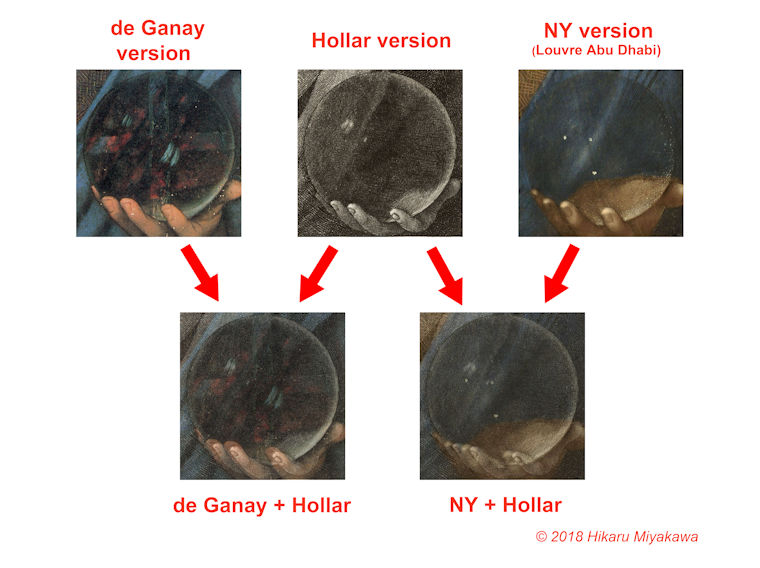

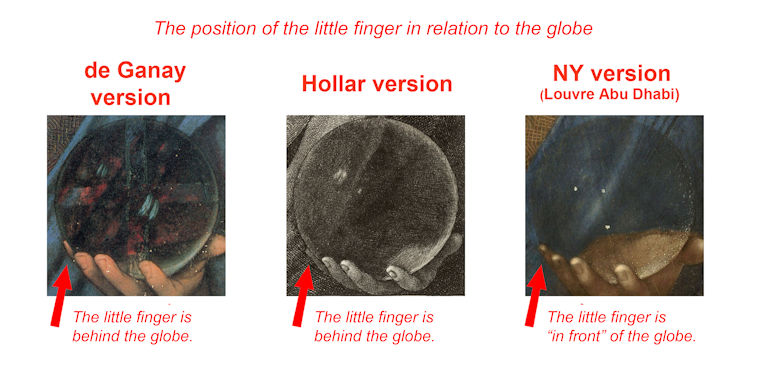

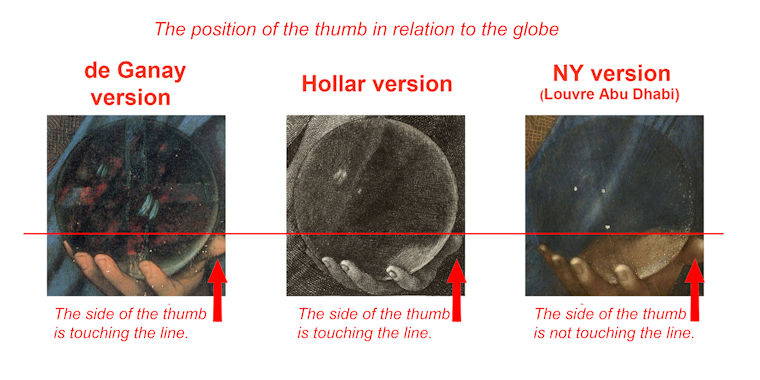

In our previous post the painter Hikaru Hirata-Miyakawa showed through the three graphics below that in addition to all the above problems with the suggestion that the Hollar engraved copy had been made from the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture, the globe copied by Hollar bears a much closer relationship to the globe found in another Leonardesque painting, the so-called de Ganay Salvator Mundi, than to the globe seen in the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi.

Michael Daley, 12 November 2018