A memorial lecture, two journals and an assault on scholarship

‘Never trust the teller trust the tale’, cautioned DH Lawrence. He meant: don’t pay attention to what anyone tells you about a work of art, not even the artist; nor, we might add, a ‘curator of interpretation’. Study it yourself. But can we always trust the evidence of our own eyes?

THE ANNUAL JAMES BECK MEMORIAL LECTURE: ‘Never trust the teller trust the tale’

On 7 November the ninth annual ArtWatch International James Beck Memorial Lecture will given by Robin Simon and held in Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W. 1. Robin Simon is Honorary Professor of English at University College, London, and the editor of The British Art Journal, which esteemed publication has launched an attack on the prohibitively high fees that museums now charge scholars for reproducing works of art – even when, as often, these are publicly owned and out of copyright – in their publications and lectures (- see below “A licence to print money, a licence to kill scholarship, at the Tate, the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery”). His recent books include Hogarth, France and British Art and (with Martin Postle) Richard Wilson and the Transformation of European Landscape Painting. Professor Simon writes:

‘Never trust the teller trust the tale,” cautioned DH Lawrence. He meant: don’t pay attention to what anyone tells you about a work of art, not even the artist; nor, we might add, a ‘curator of interpretation’. Study it yourself. But can we always trust the evidence of our own eyes?

Above, Mars chastising Cupid by Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582–1622), 1613. Art Institute of Chicago.

For details of the (evening) lecture and tickets, please contact Helen Hulson at:hahulson@gmail.com.

THE ARTWATCH UK JOURNAL AND THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2015 CONFERENCE ‘ART, LAW AND CRISES OF CONNOISSEURSHIP’

Later this month we publish the ArtWatch UK members’ Journal No. 31. It comprises 112 pages and contains the full and illustrated proceedings of the 5 December 2015 conference “Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship” organised by ArtWatch UK, the Center for Art Law, New York, and LSE Law – see below. It will be followed in December by issue No. 32, a special edition on Michelangelo. The ArtWatch UK Journal, is not sold but is distributed free to all members. For membership details please contact Helen Hulson at: hahulson@gmail.com.

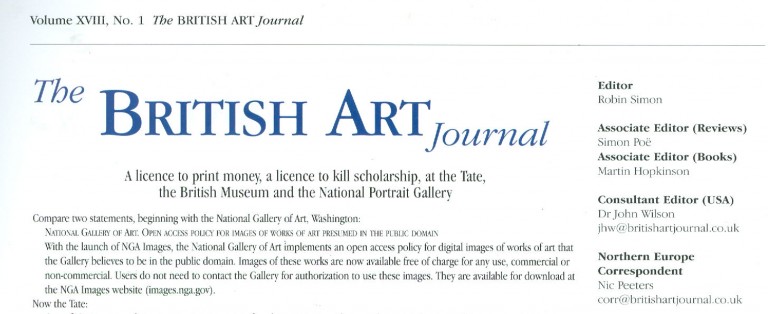

A LICENCE TO PRINT MONEY, A LICENCE TO KILL SCHOLARSHIP, AT THE TATE, THE BRITISH MUSEUM AND THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

The British Art Journal (XVIII, 1 2017) editorial in full:

Compare two statements, beginning with the National Gallery of Art, Washington:

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART. OPEN ACCESS POLICY FOR IMAGES OF WORKS OF ART PRESUMED IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN.

‘With the launch of NGA Images, the National Gallery of Art implements an open access policy for digital images of works of art that the Gallery believes to be in the public domain. Images of these works are now available free of charge for any use, commercial or non-commercial. Users do not need to contact the Gallery for authorization to use these images. They are available for download at the NGA Images website (images.nga.gov).’

Now the Tate:

‘One of Tate’s core goals is to promote enjoyment of, and engagement with, art and artists within our collection, to audiences wherever they are in the world. As part of this, we are releasing some of our Archive collection digital content and some items from our main Collection for use for non-commercial and educational purposes under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported) licence. The aim is to provide a simple, standardised way to grant copyright permission for the use of Tate’s intellectual property (its photography) and artists’ creative work for specific uses only, whilst safeguarding Tate’s own income from its IP in commercial contexts whilst ensuring artists, copyright holders and Tate get credit for their work and are protected by law.’

And so what, then, is ‘commercial’ use? The Tate begins:

‘Creative Commons defines commercial use as “reproducing a work in any manner that is primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or monetary compensation”.’

Unfortunately for the Tate, this does not suit it at all, since no-one could argue that academic work in particular is ‘primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or monetary compensation’. If it were to be excluded, the Tate would not be able to seize fees for the vast majority of publishing about its collections. And so it simply invents its own definition, even while still invoking the Creative Commons licence, bringing academic (and indeed any other) work within ‘commercial use’, as follows:

‘Tate further defines commercial use… [our italics] [as] use on or in anything that itself is charged for [! our exclamation], on or in anything connected with something that is charged for, or on or in anything intended to make a profit or to cover costs [we are running out of !s]… Tate would usually regard the following uses of Tate imagery as commercial activity: use online or in print by commercial organisations, including (for the avoidance of doubt) trading arms of charities; use on an individual’s website in such a way that adds value to their business, or for promotional purposes, or where offering a service to third parties; use of images by university presses [we can afford one more !] in publications online or in print; use in publicity and promotional material connected with commercial events; unsolicited use of images by news media, including front covers and centre-page spreads; use in compilations of past examination papers; use by commercial galleries and auction houses.’

And so any publication, however useful to the Tate in expanding public knowledge and understanding of works in the collection, if it is to avoid the hefty fees that the Tate imposes, must needs be handed out free and never, ever, published by a university press… This attitude is disgraceful. Alas, the British Museum, which under Neil MacGregor and Antony Griffiths had a praiseworthy free use of images in Prints and Drawings, has followed the Tate’s lead and now invokes a Creative Commons licence with the purpose of imposing reproduction fees, as does the National Portrait Gallery.

The Tate has given up on attempts to assert copyright in works of art that are actually out of copyright, and instead asserts that it is now, rather, protecting the copyright of its photographs of those works, defining them as its ‘intellectual property’ (IP) in what is meant to be a nifty sidestep. That cannot, however, avoid the fact that, as we have pointed out in these pages, this is unsound in law, in view of the purely mechanical nature of the image-recording operation. Fascinatingly, the NPG seems to have a different understanding of the matter, asserting in a letter in response to an enquiry about it:

‘The National Portrait Gallery owns the copyright of the majority of the images in its collection. Even if an image is “out of copyright”, as it is still part of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, then copyright continues to be managed by the Gallery.’

This runs directly contrary to copyright law defined in the NPG’s own ‘Introduction to copyright’, as follows:

‘Under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended), copyright protects original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works; films; sound recordings; broadcasts and typographical arrangements… Copyright usually lasts for the creator’s lifetime, plus the end of 70 years after their death.’

Precisely. We note that works under copyright must be ‘original’ in UK law. But the photographs of works in these collections, if they are to the job they are required to do, must needs exclude originality and remain precisely faithful to, yes, the original works – most of which are, of course, out of copyright.

The adoption of Creative Commons licences has nothing to do with the law of copyright in the UK. It is simply a device adopted in order to allow the museums to continue to charge for the reproduction of out-of-copyright works of art in their care, which, moreover, belong to the public they are charging for use. There seems, frankly, no good reason for this restrictive practice if these museums are indeed concerned, as the Tate puts it, ‘to promote enjoyment of, and engagement with, art and artists’. Could it be, then, that its purpose is to perpetuate the employment of the gallery staff who collect the money? Any fees collected will be largely cancelled out by costs: salaries, administration, office space, equipment, pensions and so on. Any profits are likely to be minimal and of no real help to the institution: but they are obtained at the greatest possible cultural and educational cost.

For a museum that is not a profit; it is a loss.

For whose benefit do these museums exist? Do they exist for the benefit of the staff who run them or for that of the public and the world of knowledge they were created to serve? Do they aim to enhance knowledge of their collections? If so, why do they go out of their way to penalize any publication or form of dissemination of images that does that work for them? The use of images of works of art in ‘news media… front covers’ or even on biscuit tins, bathmats or shower curtains, all serve the same purpose, which, to repeat, the Tate defines as ‘to promote enjoyment of, and engagement with, art and artists’.

Strange to say, these ‘Creative Commons’ licences originate in the USA where, however, the position, as set out by the NGA above, is clear and simple, and directly contrary to that of these UK museums. No wonder the Tate has to add so many subordinate clauses and pseudo-legal assertions to the provisions of the Creative Commons licence it invokes.

It would be a far, far better thing if these pointlessly rapacious museums in the UK adopted a different, transatlantic, model: that of the National Gallery of Art in Washington and of countless other museums throughout the USA. What are they afraid of?

And who pays for digitizing their images? It so happens that the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art handed out it largest ever grant, £500,000, to the British Museum to digitize its British drawings, surely not with the intention that the museum might now charge for their use. The Mellon Centre’s parent institution is the Yale Center for British Art – where images of artworks in the collections are offered free for any purpose.

To return to the Tate… If, say, you look up Arthur Melville on the Tate website you will find that his biography, far from being written by a curator, as one might hope, is simply a link to Wikipedia. By what right? Yes, by yet another Creative Commons licence which, luckily for the cynical Tate, states on the Wikipedia site that anyone may ‘share… copy, distribute and transmit the work… for any purpose, even commercially.’

Now that sounds like a sensible licence.

Michael Daley, 17 October 2017

Leave a Reply