Two developments in the no-show Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi saga

The art world is like no other. It goes its own way. It makes (and sometimes breaks) its own declared rules. Politicians scarcely dare touch it. Lawyers do well on it. It is often averse to disclosure and transparency and it is always full of surprises: since our 18 September post, there have been two spectacularly dramatic developments concerning the marketing and the appearance of the (still un-exhibited) Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi, which work appeared from nowhere in 1900 and has now rocketed from a $750 appraisal to a $450 million sale and elevation to the Louvre in barely a decade.

How? The most effective way to improve a picture’s standing and value is to change its appearance in the names of “conservation” and “restoration” – the sanctified procedures that facilitate the “discoveries” on which new evaluations may stand. In effect, restored works are new works that have shed old selves and reputations, thereby inviting re-appraisals in a new milieu. In technical parlance “conservation” is the overall process of transformation commonly described in quasi-medicalese as a “treatment” following state-of-the-art “diagnostic” technical analysis. The term “restoration” got a very bad reputation: when this Salvator Mundi was being downgraded from Luini to a Boltraffio copy, picture restorers had been dubbed “picture rats”. It is now confined to describing the late stages of conservation where conservator/restorers pick up brushes and paint towards the “recovery” of art historical authenticity. With this particular Leonardo upgrade, the changes of appearance were protracted and under-reported. Even less examined or reported were the picture’s geographical art market origins.

In “How the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi became a Leonardo-from-nowhere” we noted failed attempts by journalists, authors and researchers to identify the auction at which the Salvator Mundi had reportedly been sold for $10,000 to a “consortium” – which is not a “ring” – of buyers who had bid by proxy in 2005. How, in the world’s most technically advanced society in our digitalised era could records of a public auction and an auction house itself disappear? We asked of the picture:

“How had it been listed? Who sold it? When? Where? Many have searched and no one has found answers but this serially redone as-if-from-nowhere work has been sold twice already – with a different face of Christ each time – for a total of over half a billion dollars”

We noted that despite its unverifiable origins, this Salvator Mundi had been showcased as a Leonardo by the National Gallery in 2011-12 and then sold privately the following year by Sotheby’s for $80 million to the owner of a string of freeports who immediately sold it on to a Russian oligarch for $127 million. That sale was made under a nondisclosure agreement which, somehow, was back-dated by the vendors to include the identity of the auction house from where the picture had been bought eight years earlier. In 2017 after further (covert) restoration it was sold by Christie’s, New York, for $450 million. We asked if the initial 2005 opacity on ownership had passed through the National Gallery and into the art market because, on 9 October 2011, the Sunday Times had reported:

“For a few weeks in London you will be able to see the Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World) up close. It might be your only chance. Much of the painting’s history remains obscure. Its ownership is a closely guarded secret. Robert Simon, a New York art dealer, is representing the owner or owners – the official line is it is a ‘consortium’. Why all the secrecy? ‘It’s just privacy and security’, says Simon, ‘One doesn’t want people knocking on the door.’”

PERSISTING ART MARKET OPACITY

Six years later, by courtesy of super-diligent investigations by both a newspaper and the author of a forthcoming book on the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi, many answers have emerged on the 2005 sale (see below). At the same time, a long-running legal dispute over the manner of the Salvator Mundi’s 2013 New York private sale has flared into a legal action against Sotheby’s in the U.S. As Bloomberg and The Art Newspaper report (“Billionaire Slaps Sotheby’s With $380 Million Lawsuit”; and “Russian billionaire Rybolovlev sues Sotheby’s for $380m in fraud damages”), it is claimed in a New York lawsuit that the Salvator Mundi’s 2013 buyer, Yves Bouvier, had been materially assisted by Sotheby’s in what Rybolovlev describes as the “largest art fraud in history” by acquiring paintings at lower prices than he represented before selling them to Rybolovlev at unduly marked up rates, fraudulently pocketing millions for himself.

Rybolovlev’s widely reported legal action in New York against Sotheby’s, New York, for $380 million of damages, specifically charges the auctioneers with having knowingly and intentionally bolstered the plaintiff’s “trust and confidence in Bouvier and rendered the whole edifice of fraud plausible and credible” by brokering certain sales and inflated valuations.

Above, Fig. 1: Reports of the Rybolovlev v. Sotheby’s action carried by the Times and the Daily Telegraph on 3 October 2018.

SOTHEBY’S DEFENCE

The Antiques Trade Gazette reports that Bouvier’s legal representatives declined to comment on the latest case (“Sotheby’s refutes $380m fraud claim filed in New York court”). Where Rybolovlev had believed Bouvier to be negotiating with sellers on his behalf in return for a commission, Bouvier’s legal representatives claimed that because there had been no written agreement appointing Bouvier as an agent to Rybolovlev, their client had “acted as an independent seller transacting at arm’s length with Rybolovlev”. However, as the Art Newspaper reports, in addition to spectacularly large mark-ups, Bouvier was indeed charging Rybolovlev a commission fee: “some of the works in question include Gustav Klimt’s Wasserschlangen II (1904) which Bouvier bought in 2012 for $112m before selling it to Rybolovlev for $183.8m plus $3.6m in commission”. The Art Newspaper also reported earlier pre-emptive auction house moves to stymie Rybolovlev:

“Sotheby’s jointly sued Rybolovlev with Bouvier in Geneva in 2017 in order to block a lawsuit the Russian oligarch was planning to file in the UK. Since then, however, Rybolovlev has been granted the use of confidential documents from Sotheby’s to build his case by a New York court. The complaint filed in Manhattan on Tuesday yesterday likely stems from this development, though the documents remain publicly undisclosed.”

This is a case of potentially enormous importance in a trade that was traditionally conducted on gentlemanly agreements within a single country but now increasingly straddles borders around the globe. If, for example, the U.S. courts should find in favour of Rybolovlev, would the consortium of vendors who sold privately for $80million in 2013 under a non-disclosure agreement (only to see the painting resold immediately for $127 million), also have a case against Sotheby’s, New York? Certainly, as Professor Martin Kemp alludes in his latest book, Living with Leonardo, a sense of grievance resides in that quarter:

“In November 2016, an article in The New York Times reported the latest developments: three ‘art traders’ (Robert Simon, Warren Adelson and Alexander Parrish) were disconcerted to find that painting was ‘flipped’ by Bouvier for $47.5m more than their selling price. Was Sotheby’s a knowing party to the resale? The auction house claimed that it was not, taking pre-emptive legal action to block any law suit by the ‘traders’…”

THE FORMERLY UNDISCLOSED 2005 AUCTION HOUSE SALE

Previously, we have chided Kemp for seeming to make light of the fact that no visual record existed of the picture either when sold at Sotheby’s, London, for £45 in 1958 or at some untraceable place in the U. S. in 2005:

“Given that we do not know the identity of the 2005 vendor or the venue of the sale and given the still sticky varnish then present on the New York/Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi, it could be useful to establish the identity of the previous owner who might well have information on previous restorations and photo-records of the painting from 1958 onwards.”

The next day (19 September 2018), The Wall Street Journal reported its discovery of the 2005 sale location (“How a $450 Million da Vinci Was Lost in America —and Later Found”). The hugely informative article by Denise Blostein, Robert Libetti and Kelly Crow, raises further questions – but first, it also carries an important reproduction of the painting when framed and on offer in 2005. This new image can now be set in its historic context.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S EXTENDED, EVER-MORPHING, VISUAL NARRATIVE:

Above, Fig. 2: A detail from the catalogue to the 9-10 April 2005 sale at the St. Charles Gallery auction house, New Orleans, showing a work to be sold from the estate of a Baton Rouge business man Basil Clovis Hendry Sr.

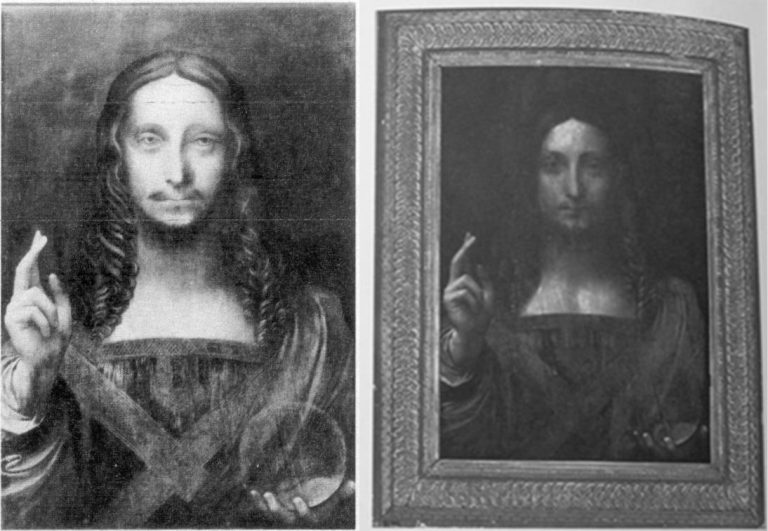

It is clear – even on the small scale, low-resolution catalogue photograph above – that the painting’s appearance had changed considerably at some point (or points) after the earliest known photograph when in the Sir Francis Cook collection (Fig. 3, below, left). Unfortunately, the 2005 vendor has yet to speak and we do not know whether any changes to the painting had been made while in the Cook collection, or by Sotheby’s (London) ahead of the 1958 sale to “Kuntz”, or by the Kuntz family and relatives at some point between 1958 and 2005.

Above, Fig. 3: Left, the photograph of the painting when in the Cook collection and judged to be a work of Bernardino Luini; right, the former Kuntz family and then Basil Clovis Hendry Sr. estate painting, as in the 2005 St. Charles Gallery catalogue.

With this new photo-record the extent of successive restoration transformations in the painting’s 1900 to 2017 journey from a Luini to a $450 million Leonardo can better be appreciated.

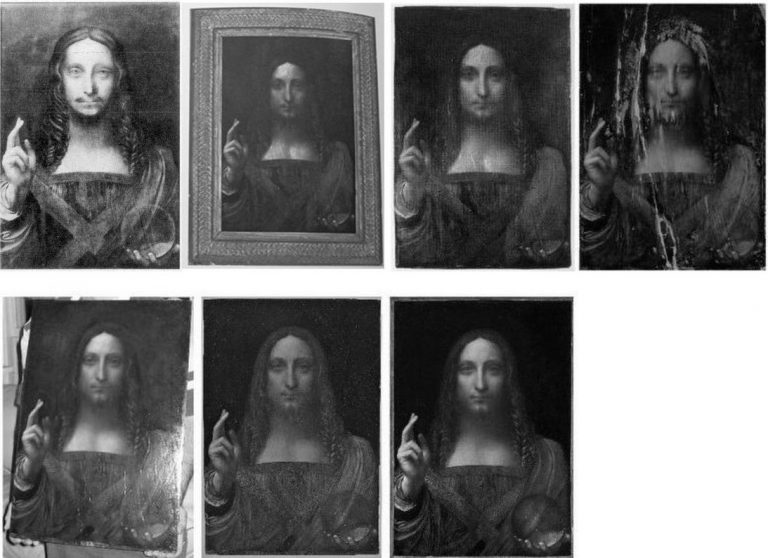

In Fig. 4, above, in the top row we see, successively: 1) the c. 1900 Cook collection photograph; 2) the 2005 New Orleans sale catalogue photograph; 3) the painting as when taken in 2005 (still sticky from some recent activity) to the New York studio of the restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini; and, 4) the 2007 record of the painting after it had been stripped and had its panel repaired. Aside from areas of total paint loss, how much of the original paint surface had been lost? If hardly any at all, as was once claimed, why so much subsequent repainting? If the original surface had been much-abraded, was due acknowledgement made of the extensive subsequent artistic changes on a single restorer’s judgements and painting? (The brushes used for this extended repainting were offered on Ebay but failed to sell.) Had all bidders in 2017 been aware of the extent to which the restorer distressed her own extensive new painting so as to confer a spurious impression of antiquity to it? (See below.) How many who bid for this painting in Sotheby’s and Christie’s sales were aware of the ratio of old to new paint?

In the second row above at Fig. 4, we see successively: 5) the painting in 2007 after Modestini’s first campaign of restoration repainting and when about to be taken to London for examination at the National Gallery by a select group of Leonardo experts who had been sworn to confidentiality; 6) the painting in 2011 after its second campaign of restoration and as exhibited at the National Gallery for the first time as a Leonardo in the gallery’s Leonardo da Vinci – Painter at the Court of Milan exhibition; and, 7) in November 2017, as sold at Christie’s New York, for $450 million after a further (covert) campaign of restoration in which the globe and the draperies at Christ’s left shoulder were radically changed.

It is not known whether the painting had been restored in 2012-13 after the National Gallery exhibition and before the opaque private sale at Sotheby’s, New York. In December 2017 (after the painting had been sold for $450 million) Christie’s, New York, acknowledged that the work had undergone further restoration by Dianne Modestini ahead of the November 2017 sale (see Dalya Alberge, “Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo Da Vinci painting which became world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in last five years” and our “The $450m New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part II: It Restores, It Sells, therefore It Is”.)

THE STRIPPING-DOWN AND REPAINTING METHOD USED ON THE LOUVRE ABU DHABI PAINTING:

“The initial cleaning was promising especially where the verdigris had preserved the original layers. Unfortunately, in the upper parts of the background, the paint had been scraped down to the ground and in some cases to the wood itself. Whether or not I would have begun had I known, is a moot point. Since the putty and overpaint were quite thick I had no choice but to remove them completely. I repainted the large missing areas in the upper part of the painting with ivory black and a little cadmium red light, followed by a glaze of rich warm brown, then more black and vermilion. Between stages I distressed and then retouched the new paint to make it look antique. The new colour freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair, and made a different, altogether more powerful image. At close range and under a strong light the new background is obvious, but at only a slight remove, it closely mimics the original…Most of the retouching was done with dry pigments bound with PVA AYAB. Translucent watercolours, mainly ivory black and raw siena, were used for final glazes and to draw [false age-] cracks…”

The above account of the repainting was delivered at a conference in the National Gallery, London, during the 2011-12 Leonardo in Milan exhibition, by Dianne Dwyer Modestini. It was later published as “The Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci rediscovered History, technique and condition” in 2014 in “Leonardo da Vinci’s Technical Practice – Paintings, Drawings and Influence”, ed. Michel Menu, Paris. It covers only the first six years of restoration up to 2011 and the National Gallery exhibition. So far as we know, no accounts have been given of the subsequent restoration work.

THE WENCESLAUS HOLLAR ETCHING PROBLEM

When this particular Leonardesque Salvator Mundi was included in the National Gallery’s Leonardo da Vinci – Painter at the Court of Milan exhibition and catalogue it was, as previously shown, presented as the original autograph Leonardo prototype for all of the other versions. In support of that claim, this version was held to have been a Leonardo painting in the collection of Charles I that had (probably) passed down from the French royal descendents of King Louis XII, who, it was suggested against contrary evidence, had commissioned Leonardo to produce the picture. As previously seen, it is now counter-claimed – again on no evidence – that although the painting had not passed down through the French royal family, it had been appropriated by Charles I from the Hamilton collection. In addition to the disintegrating provenance that buttressed the Leonardo endorsements of the National Gallery, Sotheby’s, and Christie’s between 2011 and 2017, there remains the plain visual objection that the Louvre Abu Dhabi painting is simply not consistent with Hollar’s 1650 etched copy of a Salvator Mundi painting then taken as a Leonardo.

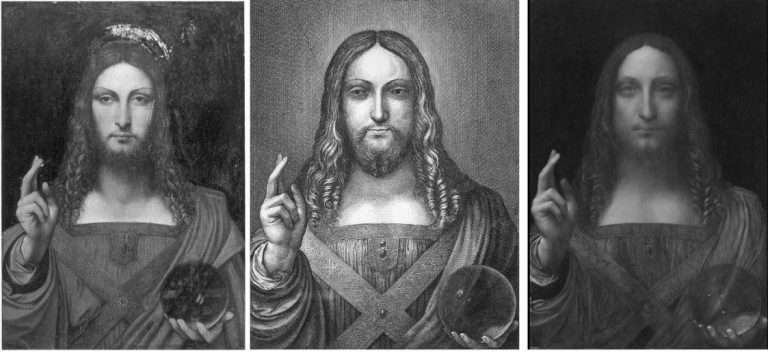

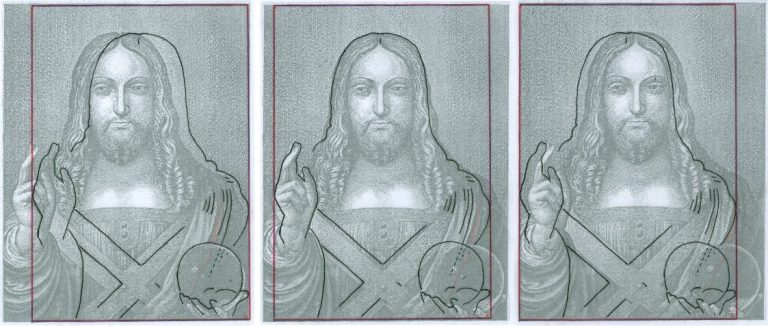

Above, Fig. 5: Successively, from the left: 1) Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1650 engraved copy of a painting believed to be a Leonardo; 2) the 1900 Cook collection painting when attributed to Luini; 3) the former Cook painting when offered for sale in 2005 from the Hendry estate; 4) the former Cook/Hendry painting when restored by Modestini and exhibited in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo show; 5) the painting in 2017 when further restored by Modestini and sold by Christie’s, New York.

SECOND TIME LUCKY

The Cook/Kuntz/Hendry painting is not the first of the score or so Leonardo school Salvator Mundis to be attributed to Leonardo himself. As previously discussed, the so-called de Ganay Salvator Mundi (below, left) was attributed to Leonardo in 1978 and 1982 and it enjoyed a greatly more plausible French lineage.

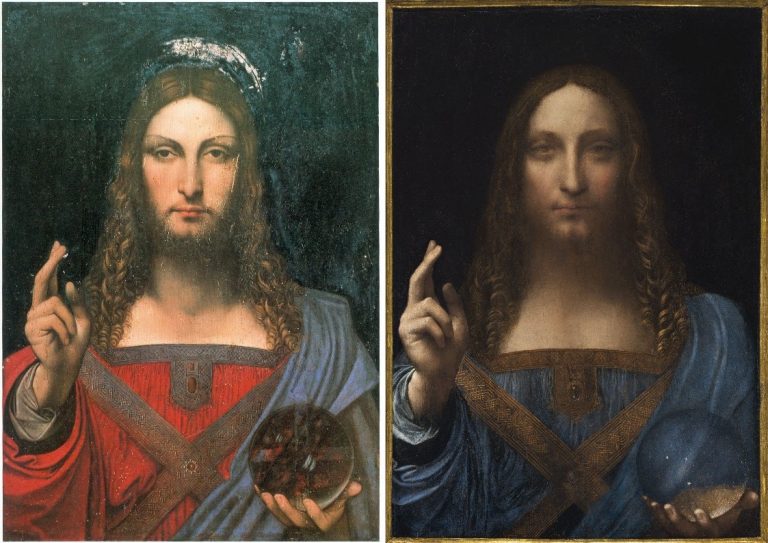

Above, Fig. 6: Successively from the left: 1) the de Ganay Salvator Mundi; 2) the Hollar 1650 etching; 3) the Cook/Kuntz/Hendry Salvator Mundi which emerged without history in England in 1900.

The compositions of neither painting above are entirely consistent with that of the Hollar copy but the de Ganay version comes closer in a number of crucial respects: its Christ has much greater sculptural presence and pictorial lucidity; its (true) left shoulder drapery has a more angular, less rounded configuration; its long, downwards-tapering, heavily bearded face is an altogether more prominently assertive feature within the painting (- and clearly was not designed to sink into the kind of “out-of-focus” aerial recession as characterised and applauded by Martin Kemp who takes this quasi-photographic effect as a confirmation of Leonardo’s hand in the Abu Dhabi picture); and, on a small but highly expressive detail, the corners of the mouth are more upturned.

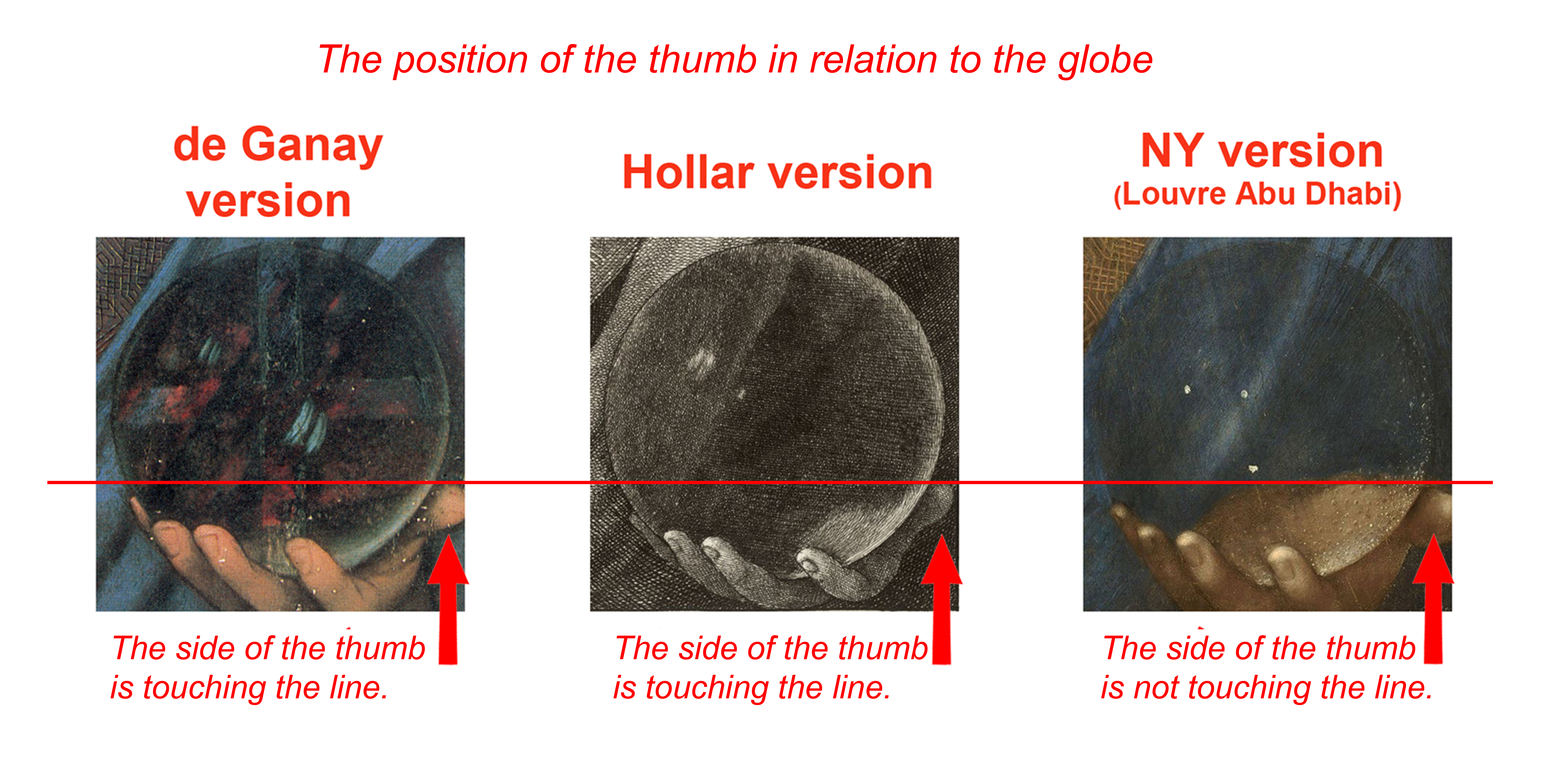

As previously discussed, there is only one respect in which the Abu Dhabi picture is more compatible with the Hollar: the hand and globe are equally tightly tucked into the bottom right-hand corner of the composition. As shown previously and below at Fig. 7, within that local coincidence, nothing approaches a “fit” between the Hollar and Abu Dhabi images.

In the three-part diagram above, a tracing of the Abu Dhabi picture’s figure (black line) and format (red box) is laid over the Hollar etching in three different positions.

In the diagram, above left, the traced outline of the Abu Dhabi painting is positioned over the Hollar image so as to align their respective and distinctive right-hand edges. That edge is a critical consideration because it had not been cut down (as the left-hand edge has been) and it shows that the painting’s author ineptly ran out of space when painting the truncated thumb that sticks out at a right angle from the hand holding the globe. This feature is utterly anomalous. Had this painting been Leonardo’s own prototype for all other versions, why had no one copied it?

In this arrangement we can see that although the globe in the Hollar is larger than that in the Abu Dhabi picture, their circumferences coincide at one point. However, when so-aligned, everything else is misaligned. If the fingers of the blessing hand are aligned, as in the second overlay, above, centre, there is also a correspondence with the outline of the tops of the heads. In the overlay above right, where the respective left-hand edges are aligned, everything is misaligned.

Above, Fig. 8: Left, the de Ganay Salvator Mundi as published in 1982; right, the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as sold in November 2017.

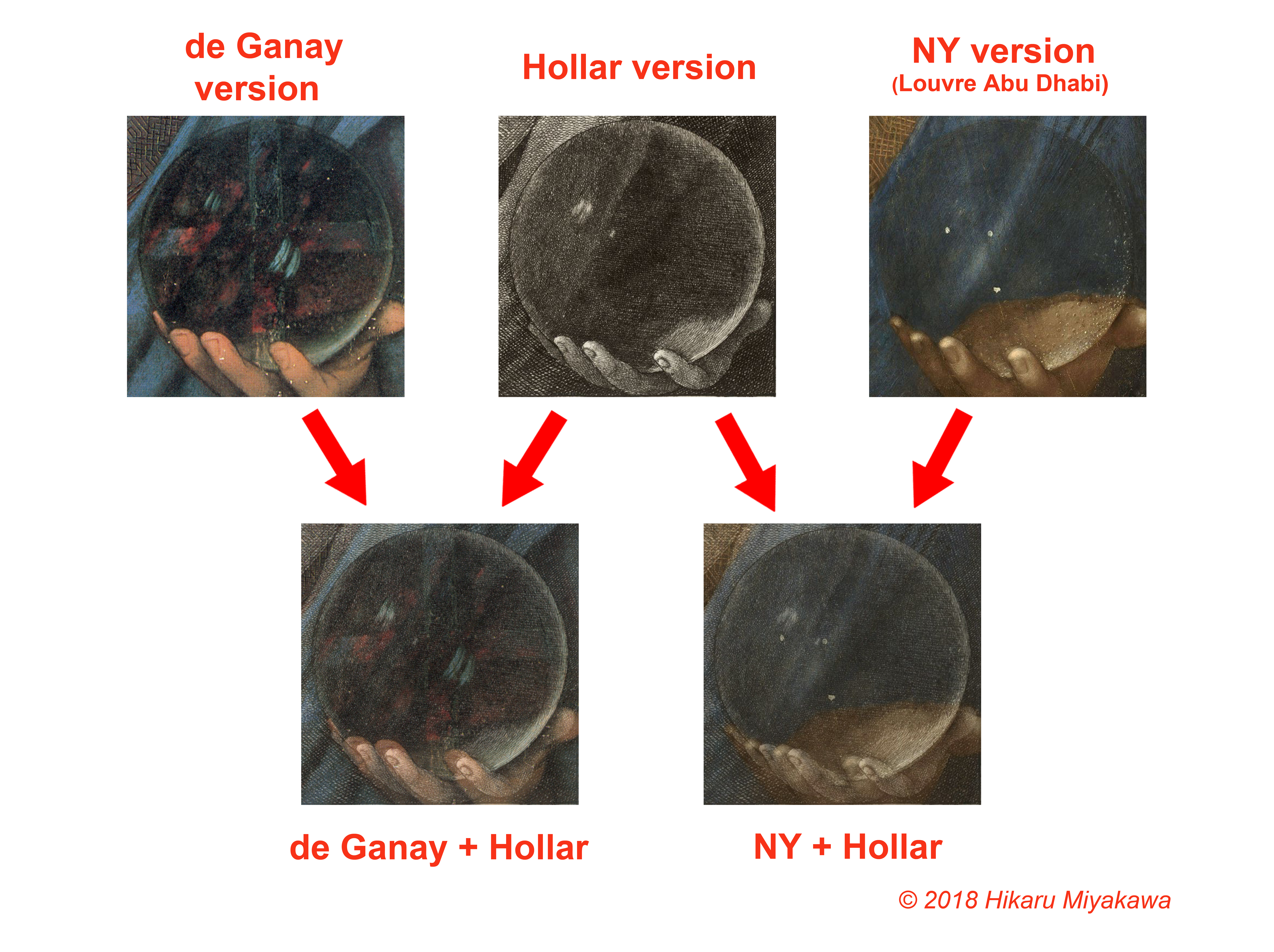

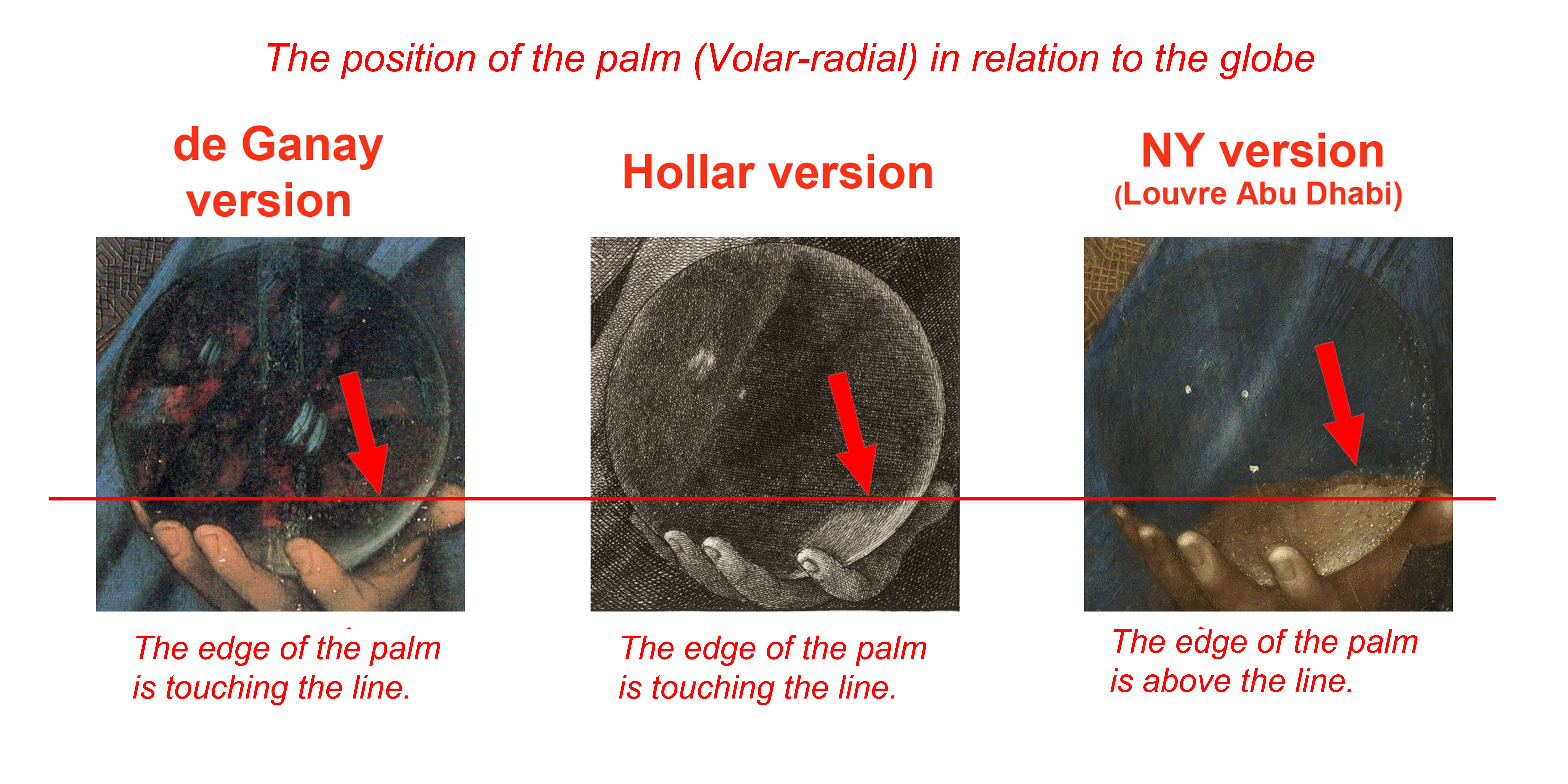

In addition to earlier comments on the de Ganay and Abu Dhabi globes, we reproduce four self-explanatory graphics below that show the hand/globe configuration in the de Ganay picture to accord more closely with the Hollar etching configuration than does that of the Louvre Abu Dhabi painting. These illustrations are the work of a Japanese painter, Hikaru Hirata-Miyakawa, who has long-engaged with Leonardo’s painted images. He writes:

“Regarding the comparison of Hollar’s etching to the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi and de Ganay Salvator Mundi, I have juxtaposed them using Photoshop. I have found that, as with the positions of the left hand, the shape and areas of reflections on the Hollar and the de Ganay globes are quite similar. Whereas, the Abu Dhabi globe does not show any reflection of the light source at all – except for the three white dots that remind me of the tiny holes for holding bowling balls. To make the comparisons I confined the images strictly to the globe and its supporting hand. While it was necessary to adjust the image sizes to make clear comparisons, I have not changed any ratios – the width and height ratio is intact and no manipulation was made to the images.”

PRESENT POSITIONS ON THE LOUVRE ABU DHABI SALVATOR MUNDI IN THE WAKE OF RECENT DISCLOSURES:

1 There is nothing to confirm that Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1650 etched copy of a Salvator Mundi painting was made from the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture.

2 There is no evidence that the painting sold in 1651 from the estate of Charles I as “A peece of Christ done by Leonardo” was either the painting copied by Hollar in 1650 or the painting acquired by the Louvre Abu Dhabi in 2017.

3 There is no evidence to support suggestions that the painting in Charles I’s collection is the painting later acquired for the Sir Francis Cook collection in 1900.

4 There is no evidence to support suggested claims that the painting in Charles I’s collection had been in French royal collections, let alone commissioned from Leonardo by Louis XII as suggested in the opening of Christie’s, New York, 2017 provenance:

“(Possibly) Commissioned after 1500 by King Louis XII of France (1462-1515) and his wife, Anne of Brittany (1477-1514), following the conquest of Milan and Genoa, and possibly by descent to Henrietta Maria of France (1609-1669), by whom possibly brought to England in 1625 upon her marriage to King Charles I of England (1600-1649)…”

5 No one has ever explained why Leonardo might have painted a prominently raised hand of Christ with two fingers that are artistically compatible with those of the Mona Lisa and three other digits that are ill-drawn, un-anatomical and consistent with no Leonardo work.

6 We do not know what, if any, provenance was provided by Sotheby’s, New York, when what is now the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture was sold privately in 2013 to Yves Bouvier. The contractual nature of Bouvier’s relationships to Sotheby’s and to the collector Dmitry Rybolovlev has yet to be determined by the courts of law in New York.

7 We now know, thanks to the Wall Street Journal, that the auction house in New Orleans at which the New York consortium/Rybolovlev/Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi was reportedly sold in 2005 for $10,000 on a $1,200-1,800 estimate (after being privately appraised for the vendor at $750) was the St. Charles Gallery branch of the New Orleans Auction Gallery in New Orleans. The New Orleans Auction Gallery reportedly went into bankruptcy proceedings and later came under new ownership as the New Orleans Auction Gallery. The Wall Street Journal reports that the director of marketing and public relations at the present New Orleans Auction Gallery has said that the new company has no records from the previous company of the same name and that: “We are not associated with that company at all”. This means that there was no possibility for the 2005 vendor to bring an action for negligence against the earlier New Orleans Auction Gallery. It means that there is presently no way of identifying/verifying/establishing who was the proxy for the consortium said to have bought the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture for $10,000 in 2005. If this is the case today, what was the situation in 2011-12 when the picture was exhibited at the National Gallery; in 2013 when Sotheby’s, New York, sold the picture privately to the fast-flipping Bouvier; and in 2017 when the picture was sold publicly by Christie’s, New York? If answers cannot be given to such questions, could anyone today challenge our 2014 contention that “As things stand, it can be safer to buy a second-hand car than an old master painting” (“Art crime”, Letter, the Times, 13 August 2014)?

THE OTHER LEONARDO-FROM-NOWHERE

In 1998 a drawing was put on the market by Christie’s, New York, as: “German School, early 19th century” and “the property of a lady”. When, some years after the sale, the work was said in the press to be a Leonardo worth $150-200 million (as the so-called “La Bella Principessa”) on fingerprint evidence (- see “PROMOTING THE DRAWING THAT CAME FROM NOWHERE”) the lady concerned disclosed her identity and brought an action for damages against the auction house on what was then only a claimed valuation on a proposed attribution, not a market-established sale. Only then was it learnt what the first buyer, a New York dealer, had not known: the vendor, Jeanne Marchig, was the widow of Giannino Marchig who was the drawing’s only owner and a painter/restorer (of Leonardo, among others) who had been an intimate of Bernard Berenson, helping him to conceal his collection from the Germans during the War. When the drawing’s second purchaser, the collector/dealer, Peter Silverman, and the Leonardo specialist, Professor Martin Kemp, trawled the Berenson archives together in search of a reference to the drawing they drew a blank. That drawing remains without history outside of the artist/restorer’s studio and, physically, it remains, as far as we know, unsold in a Swiss freeport. Such is precisely the kind of information to which potential buyers should rightfully be privy.

On the Salvator Mundi, the Wall Street Journal has said: “Mr. Simon says he has been unable to disclose details of the 2005 sale because of a nondisclosure agreement he signed when he sold the painting in 2013.” In the April 6 Antiques and Arts Weekly, Dr Robert Simon was asked: “Can you say where you found Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’?” He replied:

“Alex and I acquired the painting at an estate auction in the United States, but we’ve never divulged the location of the auction. We were not permitted to, according to the terms of the confidentiality agreement we signed at the time we sold the painting.”

Whatever purpose might have been served by the 2013 nondisclosure agreement with Sotheby’s, the painting’s origins had been unclear even before it was exhibited as a Leonardo at the National Gallery in its 2011-12 Leonardo in Milan exhibition. In the National Gallery’s 2011 catalogue entry it was said only that the Salvator Mundi was from a “Private collection”. In October 2011, the Sunday Times reported: “Luke Syson [the show’s curator] is one of the few people who knows who owns the picture. ‘We couldn’t exhibit it otherwise. It’s not being wafted to us in a brown envelope.” (Kathy Brewis, “Leonardo? Convince Me”, the Sunday Times, 9 October 2011.) Brewis wondered about the ownership and whether the National Gallery was taking a risk putting the painting on display, “so soon after its authentication”. A month afterwards the mystery of ownership remained. In the Times (“It’s kind of scary – I wrapped it in a bin liner and jumped into a taxi with it”, 12 November 2011), Ben Hoyle reported:

“Robert Simon has always hero-worshipped Leonardo da Vinci. When the New York art historian was 15 and a small-scale art dealer, he made a ‘pilgrimage’ to the artist’s birthplace in Vinci, in Tuscany. In his 20s he almost wrote his doctoral thesis on Leonardo’s followers, but was dissuaded by the immensity of the task. So when some old friends in the art world came to Mr Simon six years ago with a crudely restored picture that they had bought, he wondered if he was getting carried away when he started to speculate that it might be by one of the great man’s apprentices…He now has a stake in the picture as ‘sweat equity’ for the work he has done on it…”

Whatever the precise arrangements of ownership with the 2005 acquisition, it must be asked why the National Gallery agreed to participate in this public secrecy on a painting whose (contested) Leonardo ascription was being supported by the gallery’s director, by one of its curators and by one of its trustees.

A FURTHER THREAT TO ART WORLD TRANSPARENCY

The present lack of transparency is likely to increase with the growing practice of settling international art market disputes not through open courts but behind closed doors with lawyers working with conflicted parties on mutually confidential “mediations” or “arbitrations”. In London on 3 October 2018, an international art lawyers’ symposium on the resolution of art world and cultural heritage disputes was jointly organised by the School of International Arbitration (SIA), Queen Mary University of London, and the Switzerland and Singapore-based arbitration and mediation centre of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). The event was (generously) hosted in Park Lane by Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr LLP, America’s second biggest law firm which is famed for its federal government connections and which employs over a thousand lawyers worldwide. A former partner, Robert Mueller, is Special Counsel to the investigation into Russian interference in the last U.S. presidential campaign. Although much interesting material was disclosed at the symposium about the nature and successes of these procedures, the resolutions of no specific art world disputes were identified because of their built-in confidentiality agreements. It might be the case that the new practices will favour the big guys over the little guys – who necessarily will forfeit their strongest card – the capacity to raise institutionally embarrassing press coverage. It might not. The problem is that no one will have any way of knowing, while both parties to settlements will be able (privately) to hint at satisfaction with the invisible outcome. No one will be publicly embarrassed, chastened, admonished, exonerated or vindicated. Virtue will be unrewarded because unrecognised.

In “SECRET DEALS AND THE ARTS CLUB” we said that since our first warning in 2014 of the threat to market confidence posed by the art world’s toxic attributions, and our specific call that year (in the above-mentioned Times letter) for increased transparency through a statutory requirement that vendors should “disclose all that is known and recorded about the provenance and the restoration treatments of works of art”, Georgina Adam had written in her 2017 book Dark Side of the Art Boom, that:

“At its base, the Bouvier/Rybolovlev dispute was about the nature of their business conducted within a market that has always thrived on secret backroom deals. By keeping vendors and buyers apart – they may never know who the other is – and insisting on discretion, agents, dealers, advisors can use this anonymity to their advantage. Various reasons can be put forward, from the need for security to the desire to avoid family quarrels or the taxman, to the risk of someone else bagging the work for sale. In the Bouvier/Rybolovlev case, one of Bouvier’s emails about a Magritte, said: ‘I must carry out this [negotiation] with the greatest discretion to avoid drawing attention to the painting and its owner; the risk is that we could lose it at auction’.”

Paintings can only be “lost” at auctions if others are prepared to pay the vendor more. It would seem that, aside from facilitating stealth manoeuvres, under privately conducted sales a larger sum of monetary value is likely to accrue to the buyer and a smaller one to the owner/vendor. Traditionally, auction houses’ first loyalty has been to the sellers: by going to an open competitive market, the highest possible price is achieved for a given work – that is the promise. By comparison, the deal for buyers is less assured: the small print insists that it is for buyers to satisfy themselves that works offered for sale are as they are described to be by the auction house – descriptions are not guarantees. Were auction houses to favour big, regular buyers over vendors they would jeopardise their own reputations. In his latest book, Martin Kemp discloses that when “La Bella Principessa’s” first vendor, Jeanne Marchig, publicly filed a suit against Christie’s in 2010 and again, on appeal, in July 2011, the auction house settled out of court by donating an undisclosed sum to the vendor’s own animal charity even though, as he adds:

“It has been reported to me that anyone who asks Christie’s what they now think is told privately that the portrait is a forgery.”

Michael Daley – 11 October 2018

Leave a Reply