“The Fate of the Parthenon Sculptures before and after Elgin”

The abiding central contention in the Elgin Marbles dispute is that the acquisition of the sculptures was such a base and illegal act of plunder that it must be undone and righted. The charge is not only unfounded it masks subsequent Greek culpabilities on the preservation of its Acropolis monuments.

The Parthenon sculptures, which are considered by the British Museum to be the greatest material productions of mankind and which are, as such, superbly well and fittingly displayed, were rescued from an abominable neglect and desecration that persisted on the Acropolis after their removal. Because the Marbles were lawfully acquired over two centuries ago, would-be restitutionists are effectively demanding that today’s asserted moral rights be backdated to circumvent and trump the law.

An even-handed (if not entirely unpartisan) examination of such restitution demands has been given by Alexander Herman, the director of the Institute of Art and Law in his 2021 and 2023 books, Restitution and The Parthenon Marbles Dispute. In the former, while noting a general shift in favour of policies that “do justice for wrongs committed in the distant past” Herman concedes that much as the term “restitution” evokes notions of justice, equity, fairness and the righting of wrongs, “it is not, strictly speaking, a legal term”. But when acknowledging the intrinsically problematic nature of restitution (“it reveals a tension between the aspirations of those seeking justice for a cause and the tough reality of legal constraint and practical considerations”), he betrays exasperation on the ineffectuality of many would-be restitution claims with a counter plaint “Perhaps the usual arguments for retaining the treasures of another culture, be they legal or museological, are beginning to wear thin”.

That the “retentionist” case often proves undefeatable on argument or evidence* is testified by Herman’s resort to the counter authority of precedents: “those arguments are in need of being tested in the light of the many recent developments that have taken place” – the developments in question being the widescale returning of human remains and artefacts to indigenous descendants. Ironically, this appeal to precedent with the Elgin Marbles is made when the Greeks have long denied that their return to Athens would itself create a monumentally dangerous museum-emptying precedent even though, as Herman acknowledges, almost all “restitution stories trace their points of reference, one way or another, back to Greece’s claim over the Parthenon Marbles.”

[* Calls for the return of supposedly looted British Museum Chinese artefacts have spectacularly backfired with the publication of Prof. Justin M. Jacobs’ Plunder? How Museums Got Their Treasures. As Dalya Alberge reported in the Observer, research has established willing and enthusiastic Chinese assistance on their acquisition.

This book will very possibly prove a game-changer. It takes the current wave of restitutionist cant head-on… and thrashes it: “Neither Stein nor Elgin acquired these objects in a manner that could be described as military plunder… Lord Elgin was unarmed… he was in fact the flesh and blood embodiment of Great Britain’s military alliance with the Ottoman sultan against the French navy in the Mediterranean…and that gratitude came in the form of permission – both written and oral – to remove ancient Greek sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens…” He asks: “Can anyone truly speak on behalf of ancestors – literal or figurative – who lived four, five, or even ten generations ago?” He invokes the wisdom of David Lowenthal: “In 1985 the historian David Lowenthal published a book titled The Past Is a Foreign Country, a now classic study of how we humans constantly rework the heritage of past generations for new purposes in the present wholly unanticipated by our forebears. ‘The past is a foreign country’, I often tell my students. ‘They do things differently there.’” And he expresses the number of British Museum artefacts that can, technically speaking, be designated as plunder as a proportion of the entire collection – “0.000024 per cent”. ]

In The Parthenon Marbles Dispute, where he greatly expands his examination of the Marbles, Herman’s frustration at obdurate retentionist facts might seems evident: “whether we like it not, there is little in the way of impugning the legality of the permission given for the removal of the Marbles.” Such a grudging recognition that there was neither plunder nor theft, might have cued George – “There is a deal to be done” – Osborne, Chair of the British Museum’s Board of Trustees who, like Donald Trump, seemingly exults in his own deal-making capacities (- in which very respect, however, he has been charged with performing a disservice to the museum’s trustees by Lord Sumption, medieval historian and former Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom).

Recognising that Britain never occupied Greece and that, accordingly, “the claim for restitution is less clearcut”, Herman then shifts ground and temporal location to claim the issue is “less about the circumstances of the original removal and more about vulnerability felt by modern Greeks, especially when it comes to threats [?] from the outside, and the traditional inability of those on the British Museum side to show much empathy.” Aside from the Meghan Markle-like whine of an institution-wide empathy-deficit at the British Museum, Herman ignores the greatly more than empathetic roles played by the British in both Greece’s 19th century War of Independence and her subsequent liberation from Nazi-rule.

Precisely because there is neither a legal nor a compelling stand-alone moral case for “restitution”, Herman commends a deployment of the currently fashionable “conflict resolution” mediation procedures designed to bypass courts and their notorious costs and risks. On this stratagem he speaks of the role for a (somehow) mutually acceptable “mediator” – and goes so far as to float the prospects of the so-called “Parthenon Project”, an avowed restitution outfit led and funded by members of a single Greek family and which boasts on its website that “The Chair of the British Museum recently publicly confirmed that there is a deal to be done between the British Museum and Greece”. The site also carries a Financial Times report of a secret meeting at the Berkeley Hotel in November 2021 between Greece’s prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, and George Osborne:

“Osborne listened intently as Mitsotakis set out his case. He had barely given any thought to the Parthenon Sculptures during his career in British politics. He’s best known for his role as the country’s ‘chancellor’ after the global financial crash. But recently installed as chair of the world’s oldest public museum, Osborne saw a chance to show he is running an enlightened institution ready to engage in the debate about the repatriation of artefacts. He also saw a man across the table with whom he could do business. ‘Nobody has tried, well, ¬forever,’ Osborne has told colleagues… Osborne has declined to speak publicly about his talks with Mitsotakis, fearing that anything he says could be used against the prime minister, who is facing an election in the coming months.”

In the event Mitsotakis survived the election but, as we tweeted on 16 August, “in 2003, possibly encouraged by Lord Owen’s support, the [then] Greek Prime Minister said to Tony Blair ‘I have an election to fight next year – could you do something about the Marbles?’” That earlier request for political assistance is public knowledge only because, Herman discloses, it was picked up by TV cameras. It is not known whether the FT article was “sourced” by Mitsotakis or Osborne, or both.

Herman also reminds the reader that in 2019 the Institute of Art and Law gave training courses to members of the British Museum staff on museum-world laws and ethics but perhaps most valuably, he alerts us to the true dangers of a would-be Osborne-engineered “loan” deal by applauding the success of a past recovery from the British Museum of an indigenous Canadian artefact by the expedient manoeuvre of a perpetually renewed three-year loan: “The result may not be ideal. The mask is still effectively owned by the British Museum trustees. But no one could fault [Andrea] Stanborn calling the event a ‘repatriation’…the loan was once again renewed in 2020…” That de facto repatriation was only made possible, however, because the recipients acknowledged the museum’s ownership: “The British Museum did recall it for an exhibition in London in 2017, but then returned it…”

That there is no legal case against the B.M.’s ownership of the Elgin Marbles would now seem to be widely recognised. That being so, it should equally be recognised that there can be no countervailing moral or culturally compelling case for moving the Marbles after more than two centuries from one museum to another, either once and for all, or repeatedly at intervals with all the increased concomitant risks of injury. In their first secret meeting, Osborne and Mitsotakis proceeded so fast as to have identified possible loan “swaps” from Athens to London but at a later meeting the Greek prime minister told Osborne that he wanted the whole collection back permanently and not on loan. The present chair of the B.M.’s trustees is said still to believe “a deal is possible”.

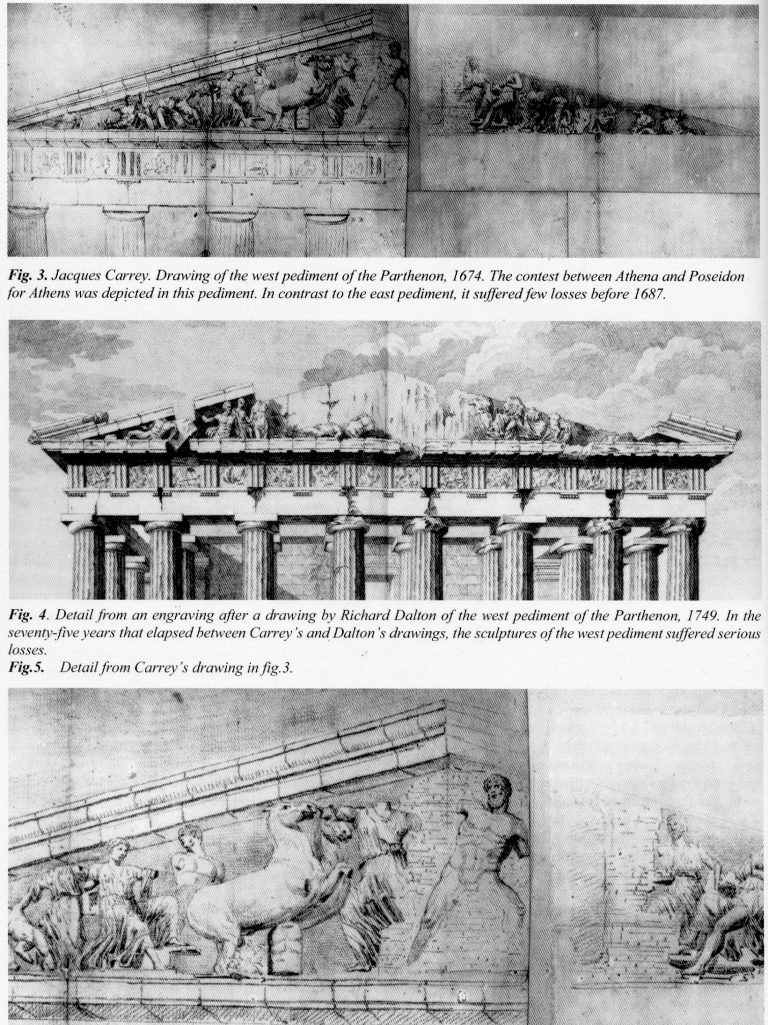

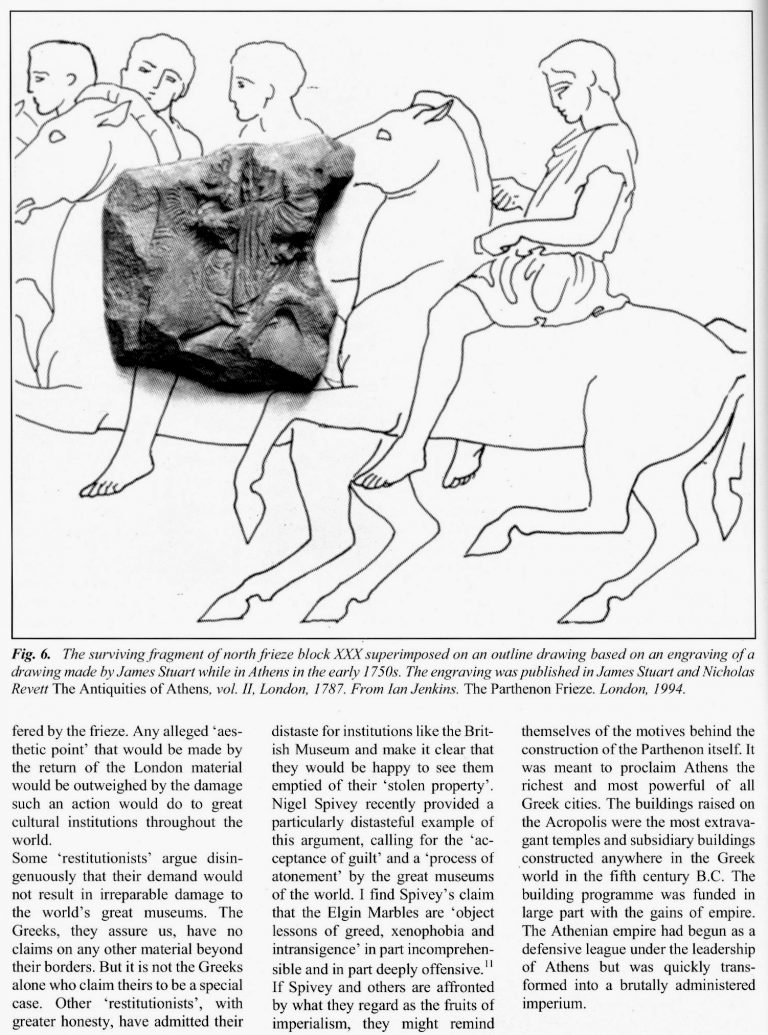

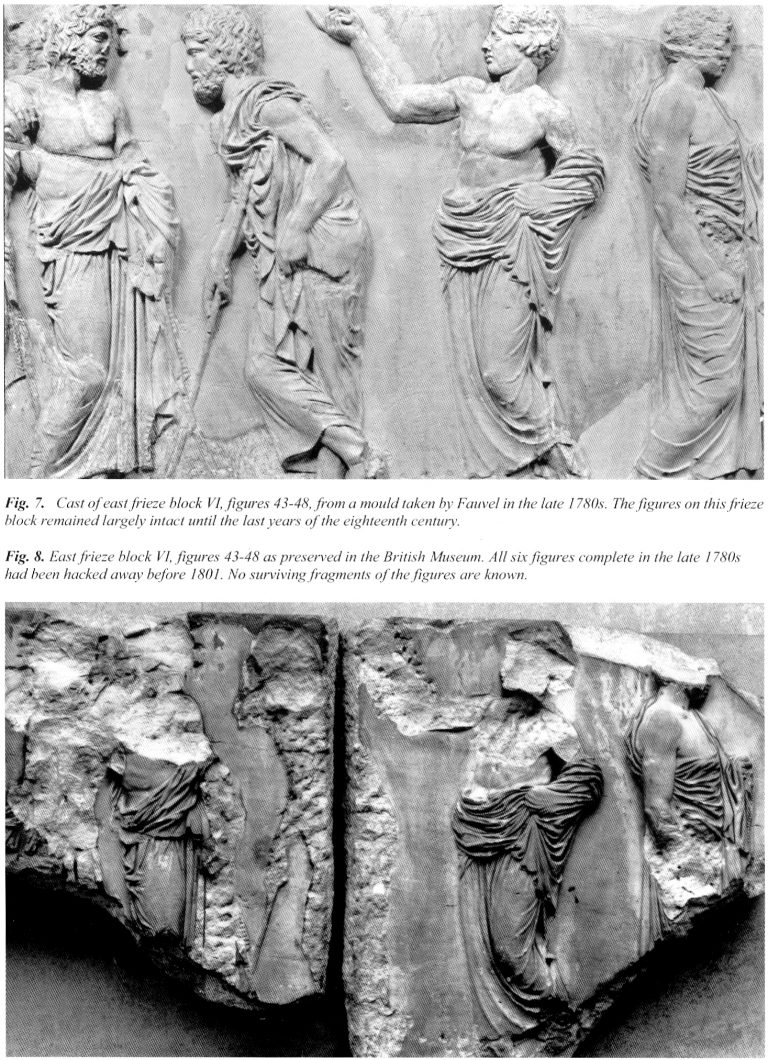

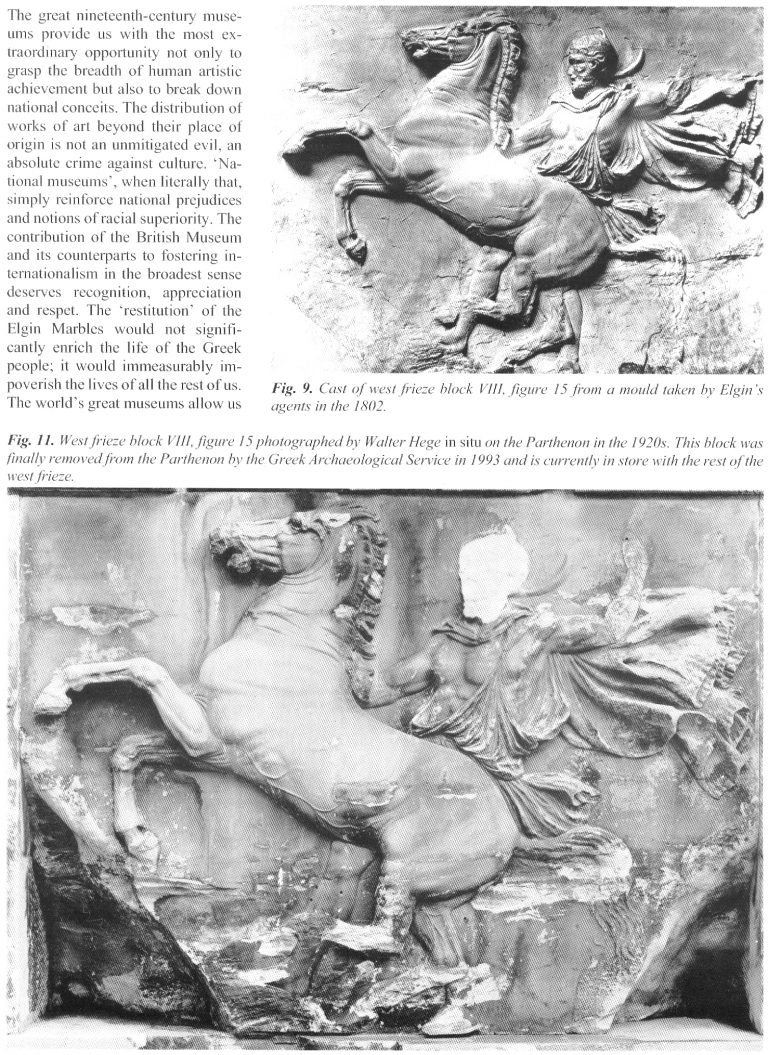

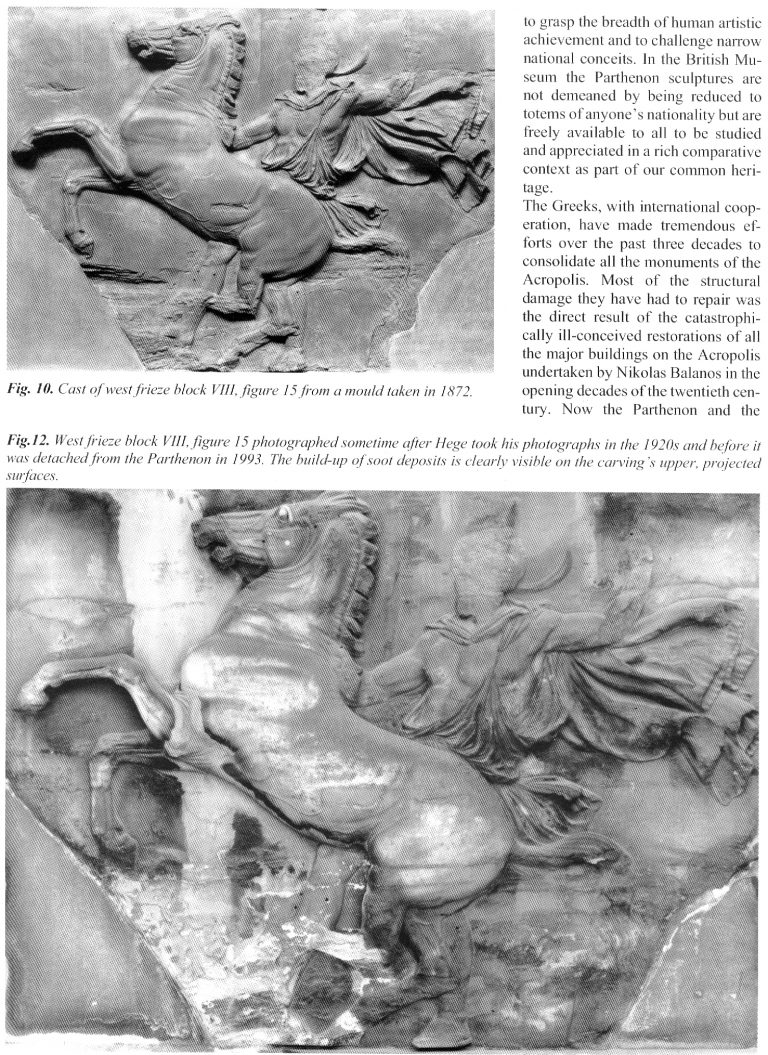

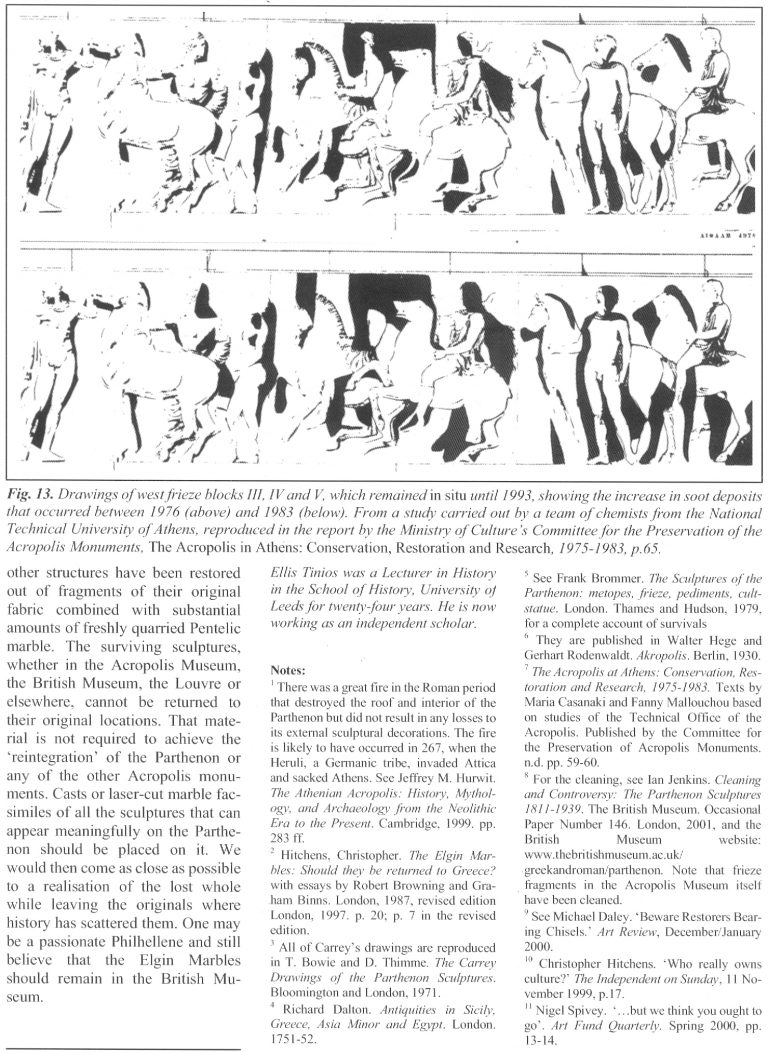

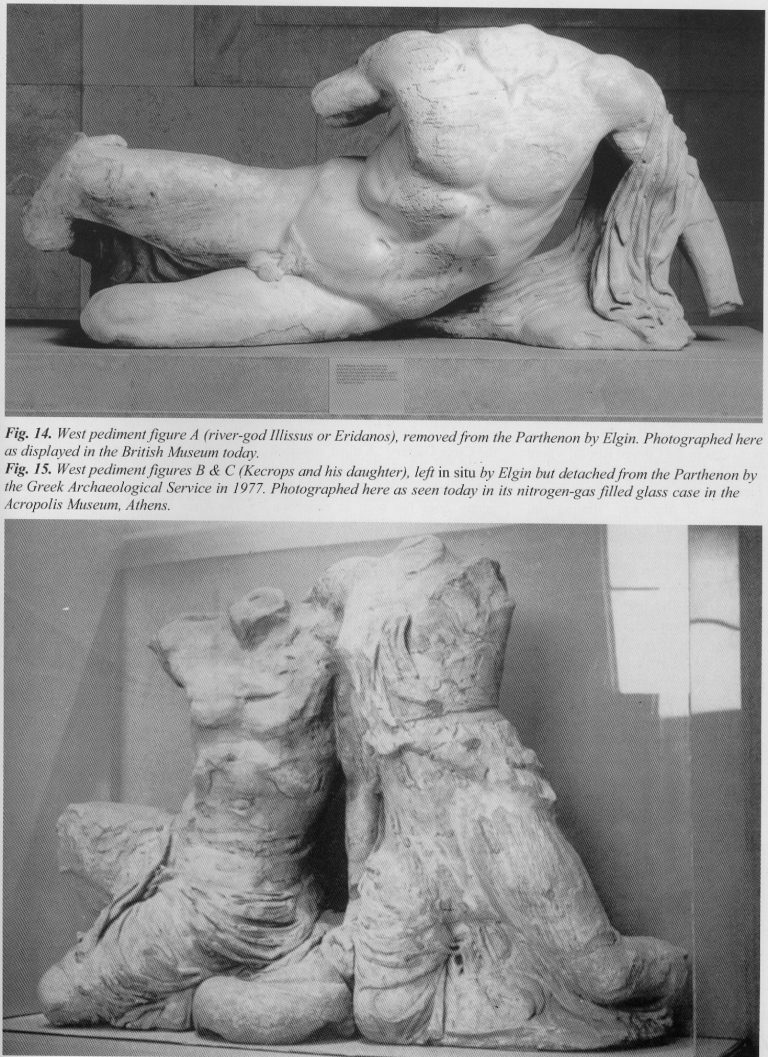

As for the conspicuous moral lacuna in the persisting restitution claim for the Elgin Marbles, it can best be appreciated by examining the scale of neglect and desecration that Lord Elgin discovered and the magnitude of his act of cultural preservation and appreciation. Not only were so many sculptures removed to safety, but the craftsmen and artists Elgin employed had also made meticulous cast and drawn records of the then preservation-states of other sculptures which today testify to subsequent losses and erosions when in Greek hands. A due recognition of Elgin’s service to art requires no new instruments of law, no secret meetings between politicians and trustees, and no wordy mediated haggles but, rather, nothing more than the simple use of our own eyes. Abundant photographic and other visual evidence testifies to the scale of pre- and post-Elgin abuses and desecrations of Greece’s cultural legacy. In our Summer 2002 journal we carried an article by the independent scholar Ellis Tinios which chronicled the extent and the truly terrible artistic consequence of those losses. We were and remain grateful to him as we reproduce his illustrated account in full below.

Michael Daley, Director: 20 August 2024

Leave a Reply