Further Thoughts II: The less and less Leonardo ex-Cook collection Salvator Mundi

Jacques Franck here concludes his three-part demolition of the once attributed but now deposed, $450m New York/Russian/Saudi Leonardo da Vinci Salvator Mundi picture’s supposed stylistic, artistic and technical credentials.

Jacques Franck writes: Many events have occurred since the publication here of my August 2020 essay on the “New York Salvator Mundi” and it seems timely to update and close the subject in the light of recently emerged technical data on the controversial painting. To grasp the present situation, a reprise of recent key events is necessary.

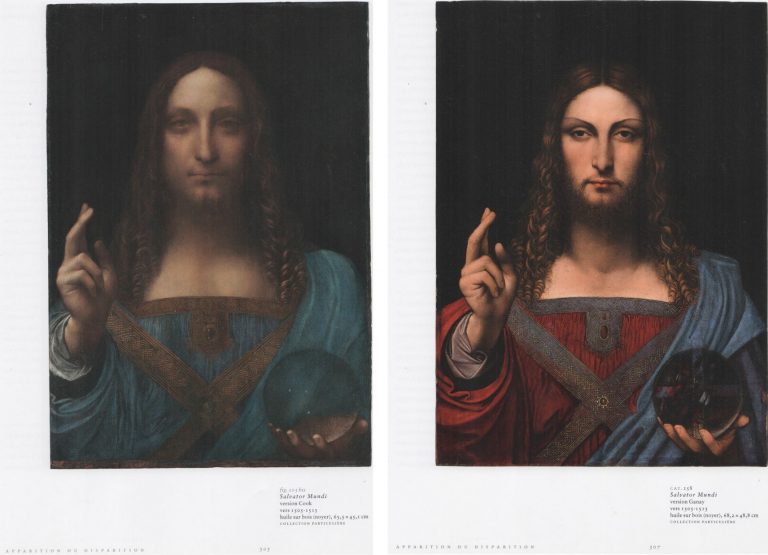

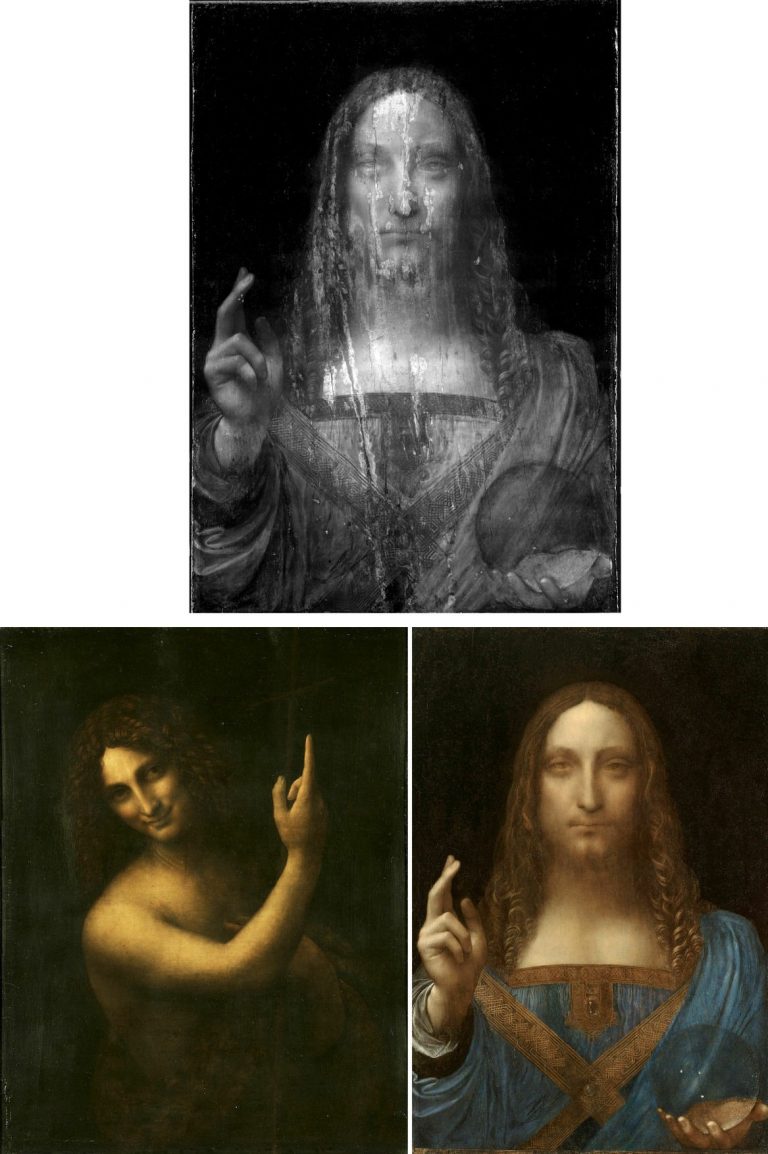

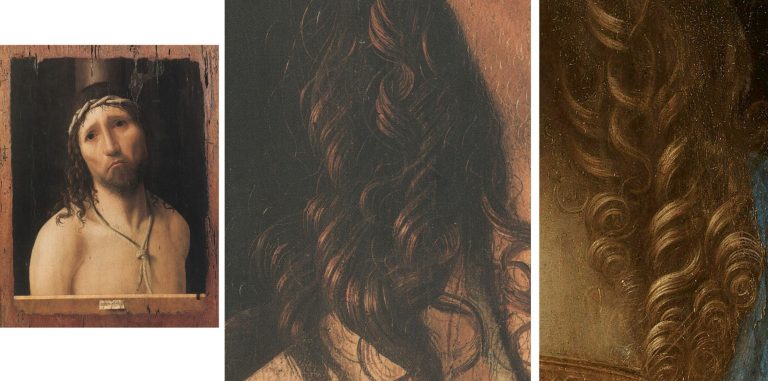

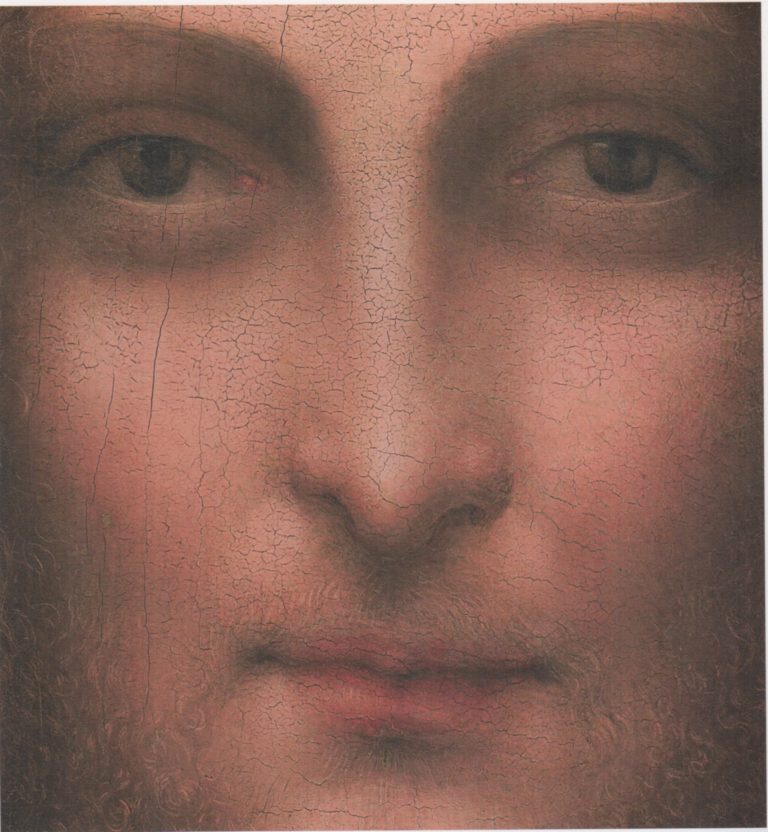

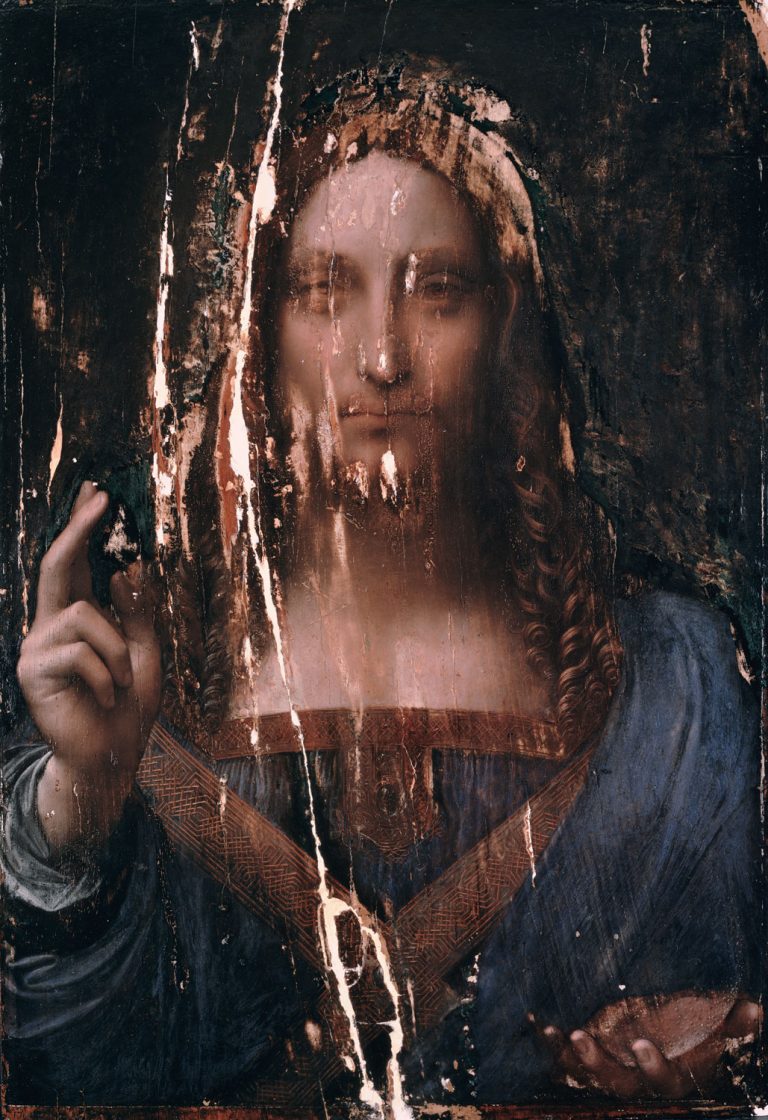

Above, Fig. 1: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of. G. A. Boltraffio?), Christ as Salvator Mundi (“the Cook version of Salvator Mundi“), c. 1506/1508-1513, oil on walnut, 65.5 x 45.1 cm (Private Collection), as seen in 2011-12.

The Louvre’s junked book: a contradiction that does not exist

It cannot be doubted that months before the Louvre’s major Leonardo da Vinci exhibition opened in Paris in Autumn 2019 the museum still believed that the Salvator Mundi was an autograph work of Leonardo. This is testified by the fact that the initial version of the Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition catalogue was printed with the (former New York, now Saudi) painting labelled as an indisputably true da Vinci picture. Shortly afterwards, that first version of the catalogue was suppressed and a new version was printed with a radically revised attribution. In it, the work – which itself was not included in the exhibition – was simply reproduced and listed as “Fig. 103 bis. Salvator Mundi version Cook” (meaning a “studio work” with a status analogous to that of another well-known Leonardo studio Salvator Mundi, called the “Ganay version”) (Fig. 2 below). Whatever reasons precipitated this sudden change, the new designation definitively constituted the Museum’s then – and still – estimation of the former New York and now “Saudi Salvator Mundi”. At this stage, that judgement is, of course, irreversible.

Above, Fig. 2: Left, Léonard de Vinci, exhibition catalogue, Louvre éditions, Paris, 2019, p. 305 (Cook Salvator Mundi); right, Léonard de Vinci, exhibition catalogue, Louvre éditions, Paris, 2019, p. 307 (Ganay Salvator Mundi).

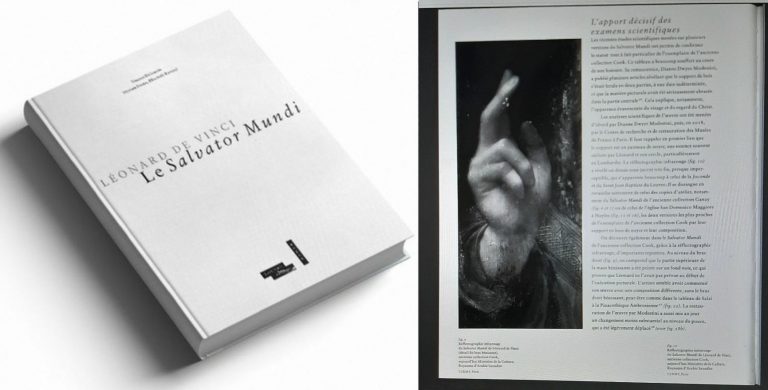

The Disappeared Louvre Technical Book – aka the “would-be-decisive-scientific-examination-of-short-lived-appearance” of December 2019

Above, Fig. 3: Left, Vincent Delieuvin, Myriam Eveno, Élisabeth Ravaud, Léonard de Vinci, Salvator Mundi, Louvre éditions – Hazan, Paris 2019, (as published in The Art Newspaper); right, a page taken from Vincent Delieuvin, Élisabeth Ravaud, Léonard de Vinci. Le Salvator Mundi, Louvre éditions – Hazan, Paris, 2019.

Above, Fig. 4: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, back of the wood panel.

Quite strangely, a 46-page booklet titled “Léonard de Vinci. Le Salvator Mundi” was published jointly by the Louvre and its laboratory (C2RMF) six weeks after the exhibition’s 24 October 2019 opening at the Louvre (Fig. 3, above). On no official announcement or evident sanction, the booklet is said to have made a very brief and accidental appearance in the Museum’s bookshop in December 2019. Its authors, Vincent Delieuvin (Leonardo curator at the Louvre), Myriam Eveno and Élisabeth Ravaud (Louvre’s laboratory C2RMF scientists), had considered and contended that the New York Salvator Mundi is an authentic Leonardo. Thus, their historical and scientific essays radically opposed the picture’s studio attribution as stated in the official exhibition catalogue. Unsurprisingly, the dissenting publication was swiftly withdrawn and the museum itself neither recognized the book’s existence nor its embarrassing contents.

With the reasons for the booklet’s leak still remaining obscure, it would be risky indeed to accept a theory in circulation whereby the pro-Leonardo version of the catalogue had been printed together with the scientific booklet in the event of the Salvator Mundi being exhibited, while another entire catalogue, in which the picture was downgraded, had also been printed simultaneously on the possibility that a loan of the picture might be refused. Such a scenario does not accord with the fact that the junked booklet was printed in December 2019 – which is to say, after the exhibition had opened – while both versions of the exhibition catalogue, one of which was abandoned, had been printed two months earlier in October. Such a theory would thus suggest that Louvre Museum staffs’ scientific investigations are determined not by matters of hard material evidence and duly considered professional judgements but, rather, according to political expediencies such as whether or not a loan request might be granted. Who could believe such a tale? Science is science and it is certainly not a discipline with one rule for one political eventuality and one rule for another. Museum laboratory researchers certainly do not draft contrary and rival test results from a single investigation so that they might comply with an institution’s future stance. Moreover, while the phantom book’s existence was known to the small circle of the Leonardo specialists after its short-lived bookshop appearance, for a long time, nobody was fully apprised of its actual contents (bar rare circulating scanned pages).

The problematic ‘‘Mona Lisa‘s male alter ego’’

While the Salvator Mundi‘s standing was not intended to remain unresolved indefinitely, its intrinsic mystery deepened with certain revelations disclosed in an April 2021 French documentary film “The Saviour For Sale. The Story of Salvator Mundi” by Antoine Vitkine on the picture’s various stages of upgrading as a retrieved Leonardo masterpiece which culminated in November 2017 when sold as such at Christie’s, New York, for $450m. Besides the sensational episodes of the work’s thriller-like route to financial success, the film addressed the long-expected loan to the Louvre and the consequent stumbling negotiations between the museum and the Salvator Mundi‘s owner, the Saudi prince Mohammad bin Salman, nicknamed MBS. Thus, we first learn that in June 2018 the panel painting was sent to the Louvre to be examined at length closely in the Museum’s laboratory and that the results of this survey, confirming the Leonardo attribution, are those recorded and discussed in the withdrawn booklet (Fig. 3 above); but then, that shortly before the blockbuster’s inauguration, the Louvre invited several Leonardo specialists to examine the painting before finalizing a loan process with MBS. At that date in 2019, the scholars’ opinion was not as favourable as that of the C2RMF scientists in 2018 and the work was downgraded to being by Leonardo in part only. The film also reports that MBS (quite understandably) resisted his property’s lowered artistic status and made clear that unless the Salvator Mundi was exhibited next to the Mona Lisa (thereby underscoring its originally claimed status when promoted by Christie’s as a “Male Mona Lisa” ahead of its November 2017 sale) the loan would be refused. Misinterpreting this imbroglio, certain parties today claim that the 2019 downgrading had prompted the Prince’s exorbitant clause. In any event, the subsequent insistence that the Salvator Mundi be shown in the exhibition as the ‘‘Mona Lisa‘s male alter ego’’, side by side, was one the Louvre could not accept for security reasons quite aside from the work’s recently lowered artistic status.

The revelations of the Vitkine film precipitated an art world earthquake: the long-running suspense from the moment the Louvre requested the loan from the owner shortly after the November 2017 New York sale, until the very day of the Leonardo exhibition opening in Paris, two years later, had been the consequence of a tumultuous negotiation over the artistic status and attribution of the painting that terminated in a late and drastic 2019 reappraisal. The unexpected downgrading by the museum that holds the most important collection of Leonardo masterpieces in the world, including the legendary Mona Lisa, constituted the strongest possible reversal and disavowal to the accrued federation of parties that had fervently and assiduously promoted the work as a Leonardo for over a decade.

Needless to say, the recent leaking of the contents of the withdrawn booklet – “the book that doesn’t exist” as many have called it – by Leonardo upgrade partisans has considerably increased the saga’s fog of ambiguity and even restored hope among the True Leonardo Believers that their icon may yet be crowned as an autograph work of the master. Nevertheless, given that the Salvator Mundi picture concerned cannot be both a true Leonardo and a studio work, the staggering contradiction between the Louvre’s present (and official attribution, as advised by leading specialists) and the C2RMF’s earlier scientific investigation of 2018, has yet to be resolved. For that reason, checking the internal scientific consistency of the “no book” now seems both essential and urgent.

Like many Leonardo scholars I have been supplied a PDF of the book “for information”, so to speak. Since, with its now international circulation, the book’s contents are no longer a guarded secret and given that many of its issues are at the heart of my own researches there are no reasons for me not to make public my observations on the mystery book’s contents and postulates. The task is made easier because the C2RMF 2018 investigation has been supplemented by other earlier and institutionally separate investigations conducted over a number of years before and after the 2017 New York sale, notably in the USA.

The assorted technical analyses of the Cook version of Salvator Mundi

The phantom Louvre booklet displays two essays: Vincent Delieuvin’s historical account of the undocumented creation of a Salvator Mundi by Leonardo (hereafter referred to as Delieuvin, 2019); and a detailed technical report by Myriam Eveno and Élisabeth Ravaud, both C2RMF scientists (hereafter referred to as Eveno and Ravaud, 2019). I shall mainly review this latter essay (albeit with some forays into Delieuvin’s piece) because its material addresses the factual aspects of the picture – that is, its physical structure and the specific components used for its execution. When necessary, I shall also refer to an American scientific investigation whose last stage was published on 20 April 2020 in Heritage Science by Nica Gutman Rieppi, Beth A. Price, Ken Sutherland, Andrew P. Lins, Richard Newman, Pen Wang, Tin Wang and Thomas J. Tague Jr. (hereafter, Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020) [1]. Some of the latter’s work was delivered by Dianne Modestini in 2014 [2].

Delieuvin’s optimistic tone contrasts with the tests themselves, which are far from conclusive, as we shall see (“The decisive contribution of the scientific examination”, Delieuvin, 2019, p. 14, my translation – unless specified, all translations are mine). My astonishment was pronounced when, having noticed the poorly significant elements actually observed by Eveno and Ravaud, I encountered the conclusion: “[In our opinion] the examination of the Salvator Mundi seems to demonstrate that Leonardo has executed the work indeed” (Eveno and Ravaud, p. 38). That latter statement was audacious: although the scientific investigation of paintings is inescapable as a rational means to understand both their structures and techniques – and as such, is of crucial assistance to art historians – it can never prove whether a painting is by one hand or another, here being that of Leonardo.

From misinterpreted observations to rushed conclusions (why the C2RMF’s 2018 scientific investigation was not to be made public)

Let us now consider a number of points which explicitly reveal why the two questionable Louvre essays, which bear conclusions extrapolated from shaky grounds, were – rightly – not meant to be published by the Louvre.

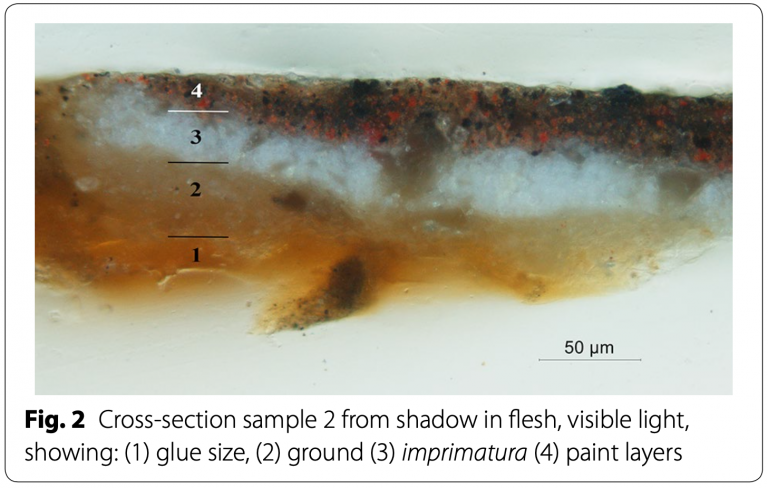

I: Panel preparation

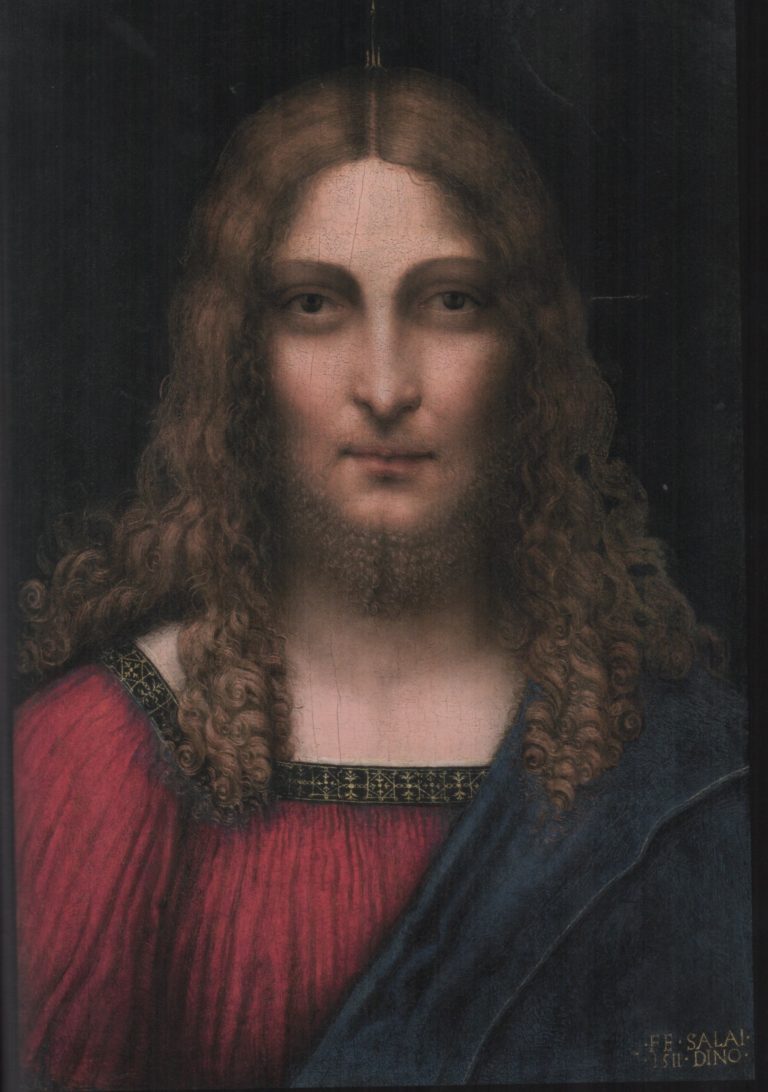

Above, Fig. 5 [after Rieppi, Price, Sutherland, et al., 2020, Fig. 2]: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, a cross section sample from shadow in flesh, visible light, showing: (1) glue size, (2) ground, (3) imprimitura, (4) paint layers.

Above, Fig. 6: Ambrogio de’ Predis (?), Portrait of a Man aged 20 (“The Archinto Portrait”), 1494, oil on walnut, 54.4 x 38.4 cm (panel), London, National Gallery.

Unlike most Leonardos (aside from the Belle Ferronnière and Saint John the Baptist), the (NY/Saudi) Salvator Mundi was painted on a walnut panel prepared with a white ground applied over the wood, which had first been coated with an unpigmented size layer (Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al. 2020, p. 9, fig. 2) (Figs. 4 and 5, above). The traditional calcium sulphate gesso is, however, mainly encountered in numerous Leonardos like the Adoration of the Magi, the Louvre version of The Virgin of the Rocks or the Saint Anne. With those, the white ground layer was followed by a thinner off-white priming layer called imprimitura; both layers contain a lead white pigment presumably bound in oil, while a small amount of a lead-tin yellow was found in the thinner second layer. These ground layers also contain glass particles of variable dimensions (consistent with manganese-containing soda-lime glass) of a type commonly encountered in Italian paintings (Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020, p. 10-12).

Eveno and Ravaud admit that the panel preparation (with the ground layers laid directly over the sized wood) of the then New York picture is unusual for Leonardo. Against that, they contend that it is found also in works like the Lady with an Ermine, the Belle Ferronnière and the Mona Lisa (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 37). While this preparatory configuration is an established fact concerning the (now) Saudi Salvator Mundi, as testified by the cross-sections published under Modestini’s direction, to my knowledge no samples (except one in the Lady with an Ermine in 1960, which is yet to be re-examined in the light of modern-day scientific methods) have been taken from the above-mentioned Leonardos. As a result, this technique of preparation is simply presumed in their case despite the researches published by the same C2RMF team in 2014 [3]. Additionally, from the latter publication we learn that this same panel preparation (ground layers of lead white applied on a walnut wood board) has been identified in Leonardo’s circle’s panel paintings, notably in the Portrait of Bernardo di Salla by Giovanni Francesco Caroto (Louvre), in a Salvator Mundi privately owned (Leonardo school) and, quite interestingly, in the Archinto Portrait attributed – notably – to either Ambrogio de ‘Predis or Marco d’Oggiono (both Leonardo’s main assistants) kept in the National Gallery in London (Ravaud and Eveno, 2014, p. 135 sq.) (Fig. 6, above). In other words, no striking evidence exists that might prove that the panel preparation in the Salvator Mundi is clearly and uniquely specific to Leonardo’s own usage, or indeed confirms that, thanks to this technical feature – as stated by the two C2RMF scientists – the possibility of its being a studio work can be automatically rejected.

Furthermore, and as if in lieu of any technical confirmation, the authors hold the preparation’s peculiarity (never observed in any of Leonardo’s own works) as strong evidence per se, on the grounds that “it accords well with Leonardo’s inventive mind, who constantly experiments new recipes, as testified by the great variety of the preparatory processes [he] employed throughout his career” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 37). And this hypothesis is offered despite the fact that the addition of grained and powdered glass particles to the two ground layers is itself another peculiarity, never encountered in Leonardo paintings either (idem) while, conversely, it has been identified in the priming layer (called imprimitura) laid over the gesso preparation in works by such artists as Lorenzo Costa, Perugino, Vincenzo Foppa, and, regularly from 1501 onwards, by Michelangelo (idem) (see infra, Fig. 12, right, backscattered electron [SEM-BSE] image).

Above, Fig. 7: top, Raphael, The Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Nicholas of Bari (“The Ansidei Madonna”), dated 1505, oil on poplar, 245 x 157 cm (painted area 216.8 x 147.6 cm), London, National Gallery; above, The Ansidei Madonna, a cross-section from the grey paint of the architecture in which particles of glass are visible in the pale yellow imprimitura.

Given that this observation is strange to Leonardo’s known practice and corresponds much more to that of other painters, including Raphael (not cited in Eveno’s and Ravaud’s 2019 essay) (Fig. 7, above) – and, presumably, to their circles – one wonders how the two C2RMF researchers came to take it as a distinctive sign of his technique. Moreover, they are further at risk when positing themselves firmly on a specific role of the glass in the ground layers: “its use, even in the preparation, appears to us as being a distinctive characteristic of Leonardo’s quest for transparency” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019 p. 38). It is true that the use of glass in paintings may be a means to improve the translucency of the paint layer, according to specific conditions, in which the refraction index of the glass and the layers where it will be introduced. In fact, the ground layers are not the level in the paint film where Leonardo would need transparency, but are where he might want to secure the proper drying of the paint, hence the American researchers’ acknowledging statement: “Glass may alternatively have been used for aesthetic effect by enhancing the translucency of the paint, but in the case of the Salvator Mundi, the glass in the lower ground and imprimitura layers more likely functioned as a siccative since these layers are not visible in the final painting image. It is also possible that the glass was added to adjust the handling and textural properties of the panel preparation materials” (Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020, p. 13) [4].

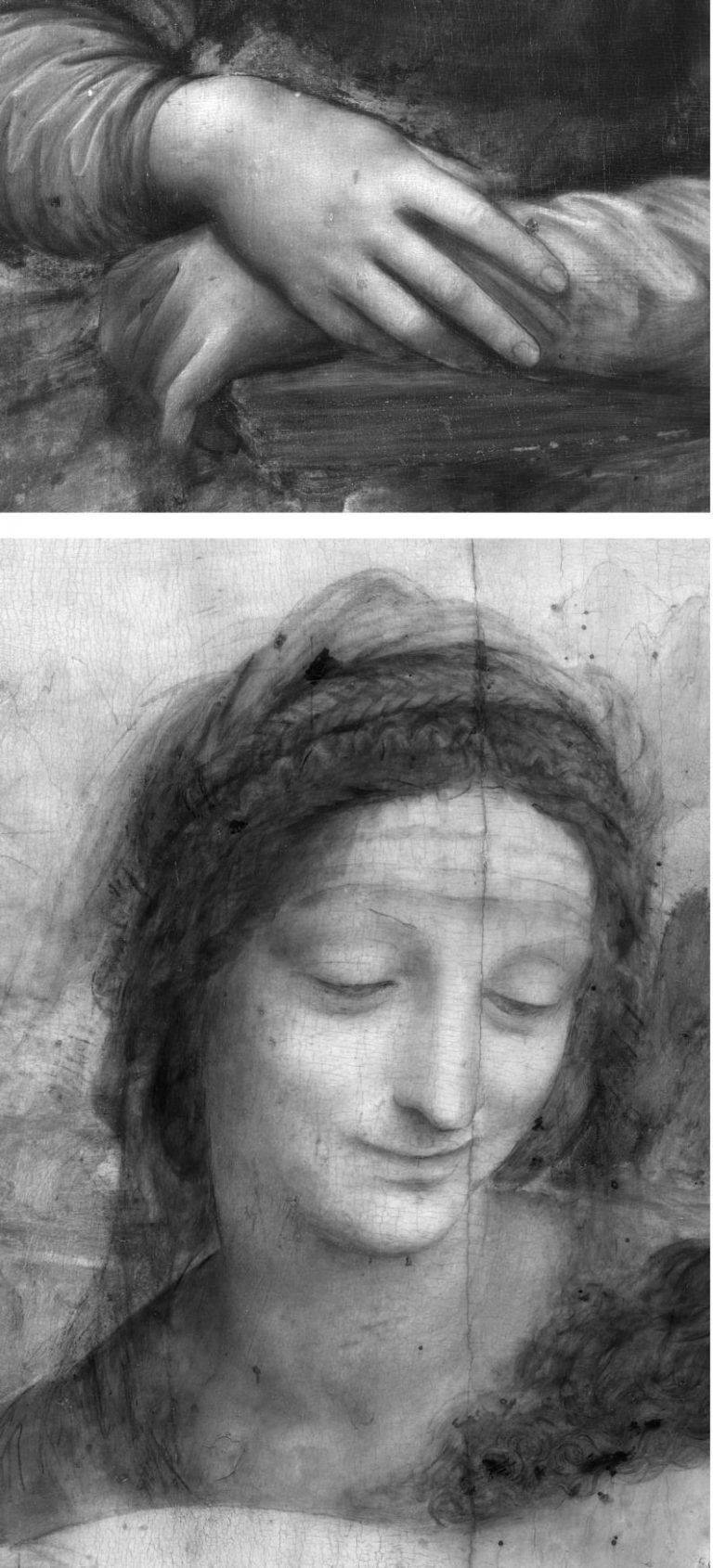

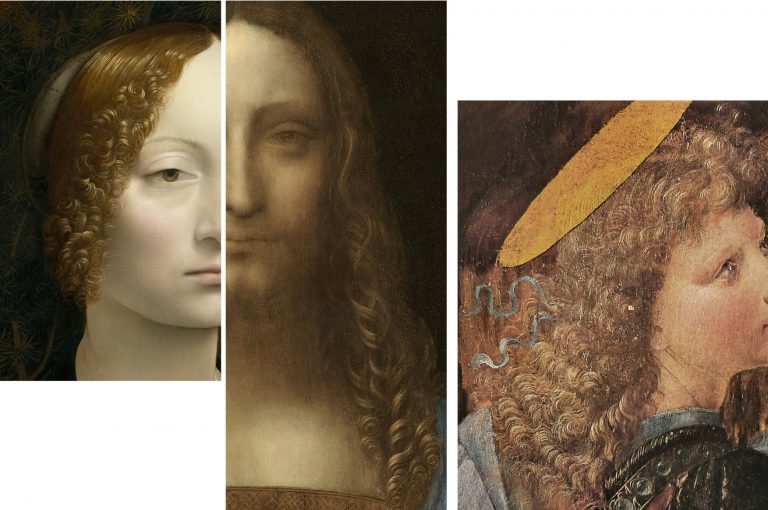

II: The underdrawing and the partial use of the infrared reflectograms

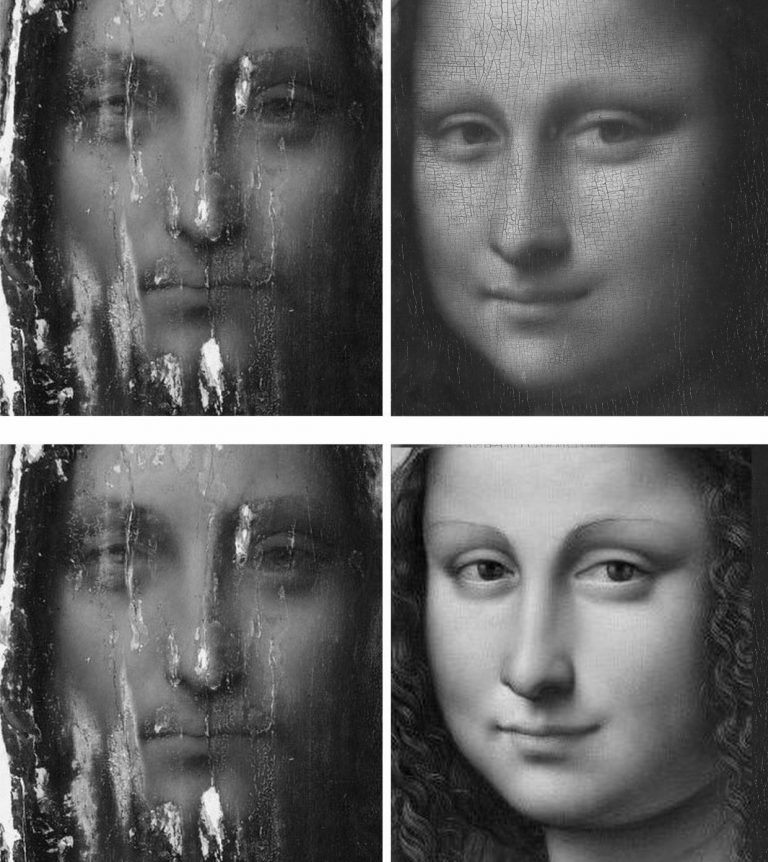

Infrared reflectography helps to detect underdrawings in paintings: infrared rays traverse the paint surface and reveal the underlying lines and wash techniques used to draw and sketch out the overall composition when they are constituted, in particular, of carbonaceous materials such as charcoal, bone black, or soot (lampblack) containing inks. Once again, Delieuvin expresses astounding optimistic views regarding the underdrawing found in the Cook Salvator Mundi: “Infrared reflectography has revealed a very thin and imperceptible underdrawing which much resembles that of the Mona Lisa and of the Saint John the Baptist in the Louvre” (Delieuvin, 2019, p. 14). This is not exactly what can be understood from Eveno’s and Ravaud’s report in the same book: “[Infrared examination has revealed] some rare thin lines absorbing infrared rays, therefore of an a priori carbonaceous nature. They delimit in particular the left eye’s iris. One notices the presence of a double contour line on a well-preserved fragment of the upper lip, although no spolvero dots can be distinguished. The other lines of the composition’s implementation have seemingly been executed in the course of the painting process” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 31).

Above, Fig. 8: top, Leonardo, The Mona Lisa, oil on poplar, 77 x 53 cm, c. 1501-1517, Paris, musée du Louvre, detail of hands (infrared reflectogram hereafter referred to as IRR); below, Leonardo, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (“The Saint Anne”), 1501-1517, oil on poplar, 168.4 x 113 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, detail of Saint Anne (IRR). In Lisa’s proper right hand, delicate contour lines have been traced to define further a now imperceptible drawing transferred from a cartoon. Thanks to tiny spolvero dots appearing on some contour lines, the use of a pricked cartoon to transfer the composition is identified in the Louvre Sainte Anne distinctly, in particular in the Saint’s proper left eyelid. The scarce and very small fragments of underdrawing in the New York Salvator Mundi are not decisive towards Leonardo’s authorship given that they don’t compare the typology of the artist’s original underdrawings. Besides, the artistic level of the painting does not match that seen in visible light in the above masterpieces.

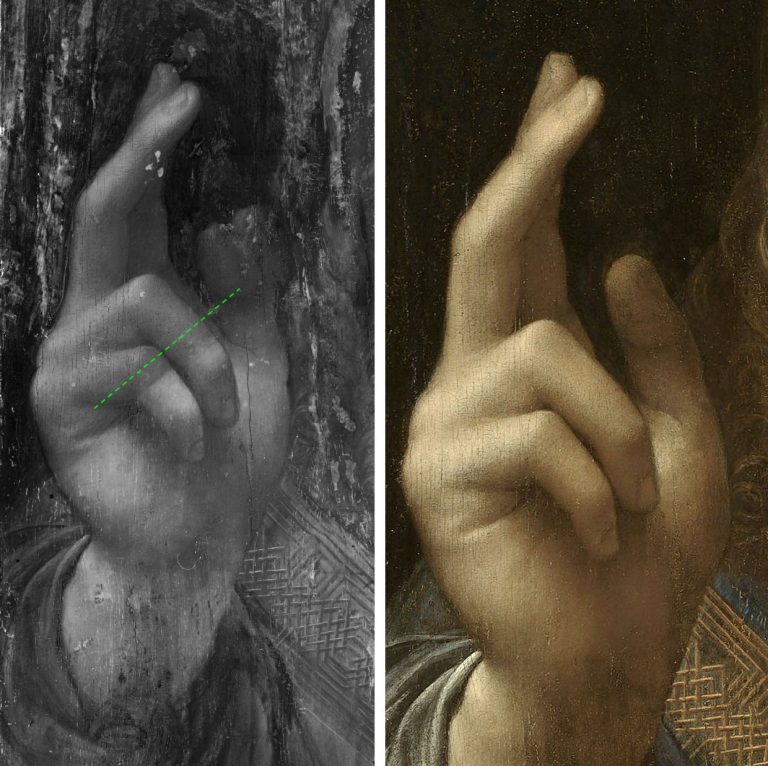

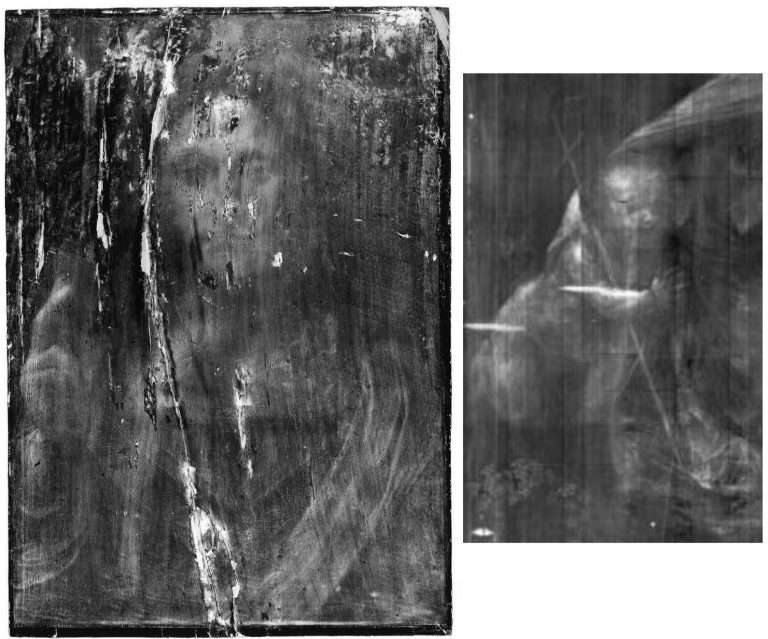

These observations are, of course, far too slight to help one figure out whether or not the Salvator Mundi‘s underdrawing compares directly with those of the late Leonardos, like the one faintly discernible, and so, just partly, in the Mona Lisa, or the one in the Louvre Saint Anne, which, conversely, is far more substantial and legible (Fig. 8, above). As already mentioned, while an excessive interpretation is drawn by Delieuvin from a barely significant item of technical information, what really matters in the infrared tests of the painting – and is therefore of far greater importance – is blatantly ignored by the three authors of the “no book”. There is a clear reason to this: the C2RMF’s infrared image is that of the restored picture, in which what is of interest does not show because the infrared rays’ deep penetration through the paint layer is stopped by the modern materials used by Modestini to reconstitute the background visually (Fig. 9, below). Fortunately, another image does exist (Fig. 10, below): it was made in 2007, before what subsists of the dark background was restored, heavily in my opinion, thus masking what is so essential in the infrared tests of the Saudi painting, that is the thick emphatic black contours of Christ’s head, shoulders and face. This crucial visual document is missing in both the withdrawn Louvre/C2RMF 2019 book and in the excellent American survey of April 2020. The significance of that image had been published in my interview in Beaux-Arts Magazine in January 2018 and for that reason, it has been known to all the parties involved closely in the Salvator Mundi‘s scientific expertise. Nonetheless, this very image does not appear either, in full at least, in Dianne Modestini’s own post-cleaning essay of 2014 on the controversial work [5]. Some details, however, especially the so fascinating one of Christ’s head, are reproduced. As the reader knows from my “Further thoughts I” posted here last year, the infrared reflectogram (IRR) of the Salvator Mundi’s background free of any inpainting reveals the amazing analogy that exists between the thick black contours of Christ’s head (a sketching-out technique never practiced by Leonardo) and those observed in a signed and dated Head of Christ, painted in 1511 by the Master’s favourite pupil and collaborator, Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called Salai (see “Further Thoughts I”, Figs. 7-11) [6]. To date, my discovery has not been commented on by those it concerns most, i. e., the various adepts at the Leonardo attribution, but it will not be kept in the background for ever.

Above, Figs. 9 A, B, and C: [A] top, workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi (IIR scan with restored background concealing the sketching out contours of Christ’s head, face, neck and shoulders); [B] below left, Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist (before the last cleaning), oil on wood, c. 1510-1517, Paris, musée du Louvre; [C] below right, The Cook version of Salvator Mundi in visible light (as in Fig. 1 above). The problem with the Modestini heavily retouched background is revealed in a clear-cut fashion when the restored stage (here, that of 2011-12, when exhibited at the National Gallery, and not yet that of 2017 when sold at Christie’s, New York) is compared visually with Leonardo’s Saint John the Baptist in the Louvre. In the latter, there is no distinct separation between light and shade. No background exists, so to speak, just an invasive obscure space within which the figure of St. John is defined thanks to the lighted zones and the transitional shading, thus resulting in an impalpable image in strict accordance with Leonardo’s quest for spatial unity between the forms and their environment, a process in which that duality is subdued extensively. In technical terms, therefore, the shadows in the background and in the foreground of the Louvre picture appear to be of the same value and “mysterious” quality. That is not the case in the Saudi Salvator Mundi: Christ’s figure is far more defined than that of St. John and clearly stands against a dark background, the shapes still have boundaries and do not float within an obscure, indefinable space like in the Louvre picture: it is an unsubtle characteristic corresponding much more to the studio’s aesthetic options observed during Leonardo’s Milanese periods of 1482-1499 and 1506/08 -1513 and for a long time after his death.

Above, Fig. 10: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi (IIR scan, 2007), before restoration, showing the heavy outlines of the underlying sketching out – unlike Leonardo’s own practice – of Christ’s head, face, neck and shoulders.

Above, Fig. 11: Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called “Salai”, Head of Christ, oil on wood, signed and dated 1511, 53 x 37.5 cm, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

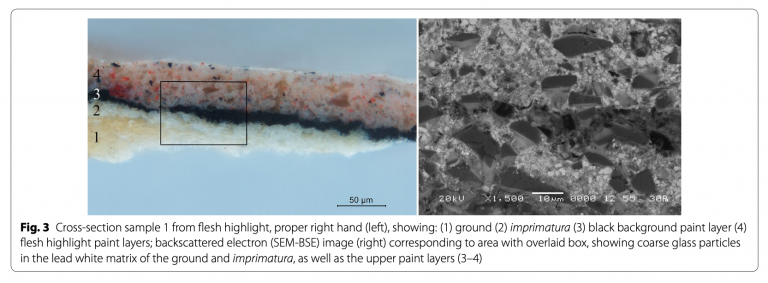

III: The blessing hand

The blessing hand is another flagrant case of extrapolated interpretation by the authors of the junked book: the elements now observed by both the C2RMF scientific team and the American one cast definitive doubt over Leonardo’s presumed contribution to the work’s execution. Still following his own line very quietly, Delieuvin seems to consider that what science reveals on that hand’s making is nothing to worry about: “Thanks to infrared reflectography, important pentimenti [autograph revisions made during the painting process] are discovered in the former Cook collection Salvator Mundi. In the proper right arm one can understand that the upper part of the blessing hand has been painted over a black background, thus proving that Leonardo had not planned it at the beginning of the execution. It seems that the artist had started working on a different composition, with no blessing arm, possibly like in Salai’s [Head of Christ] in the Ambrosiana” (Delieuvin, 2019, p. 14), (Figs. 11, 12 and 13.)

Above, Fig. 12 [after Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020, Fig. 3]: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, cross-section sample from flesh highlight showing, left: (1) ground, (2) imprimitura, (3) black background paint layer, (4) flesh highlight paint layers. The backscattered electron (SEM-BSE) image – right – shows coarse glass particles in layers 1-4. The black background paint layer underlying the flesh highlight is clearly visible here: it does not correspond to any recorded Leonardo practice.

Above, Fig. 13: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail: IRR scan image showing the black background seen through the translucent flesh paint of Christ’s right proper hand (along green dotted line); right, the proper right hand, after restoration and in visible light.

That, of course, is not the interpretation that should be drawn from this extraordinary discovery in order to respect both technical and historical accuracy: a pentimento, a word meaning “repentance” or “regret” in Italian, is an action, while being an adjustment or correction, that is consistent with the composition as it was conceived by the artist at the outset. From this standpoint, Delieuvin is right in considering that the initial composition of the Cook Salvator Mundi was identical to that of Salai’s Head of Christ in the Ambrosiana: it is the more certain as the black background was, if not finished, largely painted around the Saviour’s head and down his proper right shoulder when the blessing hand was added (as shown on the infrared documents and the cross-section sample reproduced here (Figs. 10, 12 and 13, above). We are therefore faced with a change stricto sensu, because, in chronological terms the pentimento is executed during the painting sessions inherent of the initial creation, thus within one and the same artistic logic of forms that were born together, whereas a change – or transformation – of composition and iconography is not: it radically modifies the initial composition’s outward appearance and can occur at any time, whether early or late, after that composition was left as it first was. In many cases, it may well be an autograph move and, consequently, not necessarily the sign of a late, apocryphal addition, yet in that of the controversial Salvator Mundi, its authenticity can be doubted insofar as the blessing hand’s gesture, anatomy and perspective are so wrong that Leonardo’s authorship seems improbable. What cannot be established, however, is the moment when the change took place, despite the C2RMF’s attempt to prove (on unconvincing grounds) that it is in Leonardo’s hand and soon followed the abandoned original idea (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 32). Also, it is worth of note that, interestingly, while Christ’s tunic and proper left sleeve are drawn carefully in the Windsor studies RL 12524 and 12525 (see “Further thoughts I”, figs. 2 and 3), no hand was conceived by Leonardo, whether sketchily or not on the latter sheets, or even traced on a separate one. The hand holding the orb has not been projected either. It strengthens my feeling that those projects were meant for the studio as a guideline for the figure’s clothing alone, and so without reaching a stage including the hands, thus suggesting that the assistants were left on their own for the execution of the whole painting (hence the stiffness observed in most parts of the drapery work and the weak, ill-depicted anatomy of the hands).

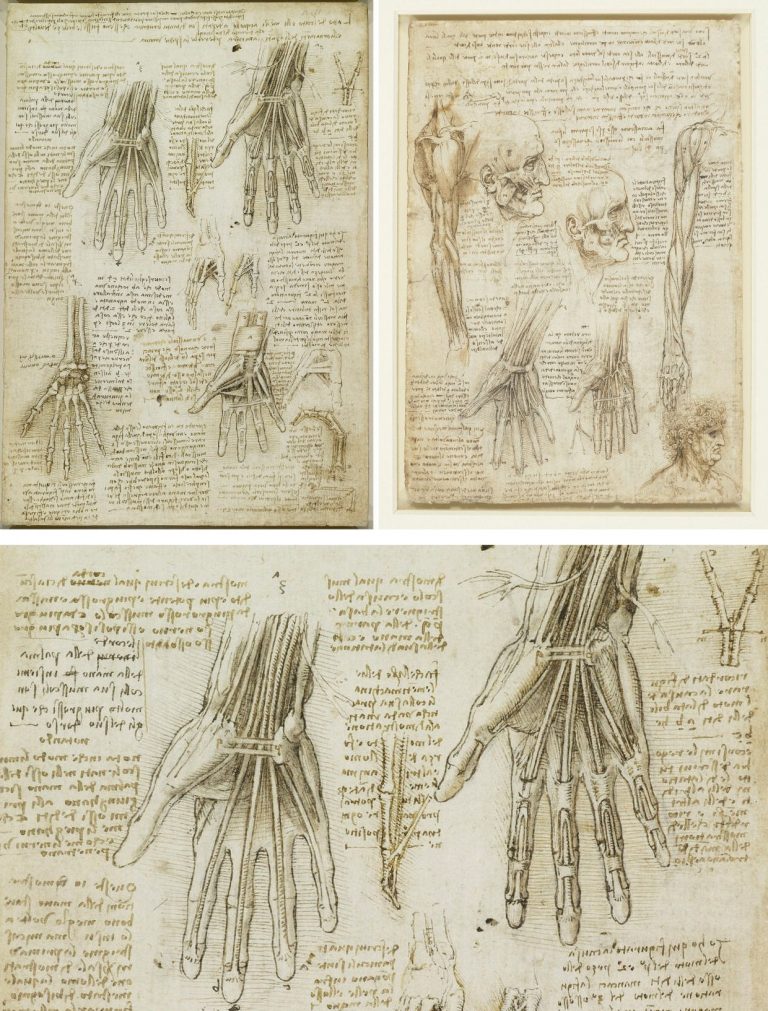

Above, Fig. 14: top, left, Leonardo, The bones, muscles and tendons of the hand, c. 1510-1511, pen and ink with wash, over black chalk, 28.8 x 20.2 cm, Windsor Castle, Royal Library, RL 19009r; top right and, above, detail, Leonardo, The muscles of the face and arm, and the nerves and veins of the hand, c. 1510-1511, pen and ink with wash, over black chalk, 28.8 x 20 cm, Windsor Castle, Royal Library, RL 19012v.

At this stage, it seems helpful to provide historical elements demonstrating Leonardo’s incredibly deep knowledge of the human hand, of its anatomy and functioning. As the reader will see, acknowledging the mass of work and the so pertinent observations contained in the artist’s research on this issue alone, is the best way to realize that the Cook Salvator Mundi’s blessing hand does not accord with Leonardo’s anatomical concepts and depictions: “The principal movements of the hand are 10; that is, forwards, backwards, to right and to left, in a circular motion, up or down, to close and to open, and to spread the fingers or to press them together” (Codex Atlanticus, folio 124v (45v-a), Richter, § 353, c. 1515- 1516). And again: “[Of the motions of the fingers] The movements of the fingers principally consist in extending and bending them. This extension and bending vary in manner; that is, sometimes, they bend altogether at the first joint; sometimes they bend, or extend, halfway, at the 2nd joint; and sometimes they bend in their whole length and in all the three joints at once. If the 2 first joints are hindered from bending, then the 3rd joint can be bent with greater ease than before; it can never bend of itself, if the other joints are free, unless all three joints are bent. Besides all these movements there are 4 other principal motions of which 2 are up and down, the two others from side to side; and each of these is effected by a single tendon. From these there follow an infinite number of other movements always effected by two tendons; one tendon ceasing to act, the other takes up the movement. The tendons are made thick inside the fingers and thin outside; and the tendons inside are attached to every joint but outside they are not” (Codex Atlanticus, folio 273a recto (99 v-a), Richter, §354, c. 1510).

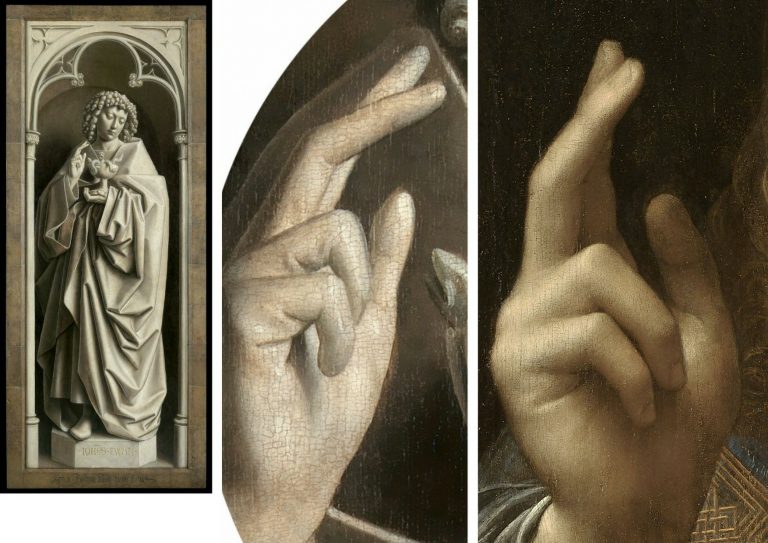

As one can see, Leonardo’s disquisition on finger movements rules out anything other than bending along a plane for each finger and provides no rotary option for any of them. To perfect the Master’s own demonstration, I have reproduced here (Fig. 14, above) two magnificent drawings of the anatomy of the hand kept in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle: beyond any discussion they prove that the artist who painted Christ’s blessing hand with something like a broken raised finger (it rotates clockwise, thus suggesting such a traumatic pathology) in the Cook Salvator Mundi cannot be the one who drew the genius sheets in Windsor. But why then such a hand? Although it is difficult to answer that question, I have long suspected that its overall concept and shape does not have an origin in Leonardo’s bottega and that its pattern, more precisely that of the “broken finger”, seems to correspond to an archaic style, thus medieval, and possibly to a Northern school artist. Whether right or not, this presumption is somehow confirmed by the right proper hand of Saint John the Evangelist in Jan van Eyck’s polyptych of the Mystic Lamb (1432), a grisaille painting at the back of a shutter of the work, where appears the same anomalous raised finger as seen in the Cook Salvator Mundi and in its numerous variants (Fig. 15, below). Neither Leonardo nor any of his close collaborators ever saw the Ghent altarpiece but this hand could well be a prototype copied from model-books by travelling artists who had circulated in Europe throughout the 15th century and had brought it to Italy at some unspecified moment. At the time the Cook Salvator Mundi was painted (c. 1510?), Leonardo was far too skilled an anatomist and an innovator to have taken any notice of such a model, but it might have been imitated while modernized by a less brilliant artist like Salai, who had spent his life in the Master’s orbit and never created anything of his own. Once again, this issue cannot be considered supportive of the Leonardo attribution. Moreover, as we shall now see, other disqualifying archaisms exist in the painting.

Above, Fig. 15: left, and centre, Jan van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece (The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb),1432, oil on wood panels, 3.4 m x 4.6m, Ghent, St Bavo’s Cathedral, showing Saint John the Evangelist, 148. 7 x 55. 3 cm, and in detail, the blessing hand; right, the restored hand in the Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi. In truth, Van Eyck’s raised middle finger is less twisted, and hence less faulty, than that in the Saudi Salvator Mundi, but its perspective is nevertheless wrong: the nail should not show so much and be in full profile instead, if at all. Also, the lower part of the finger tip should be seen more from underneath.

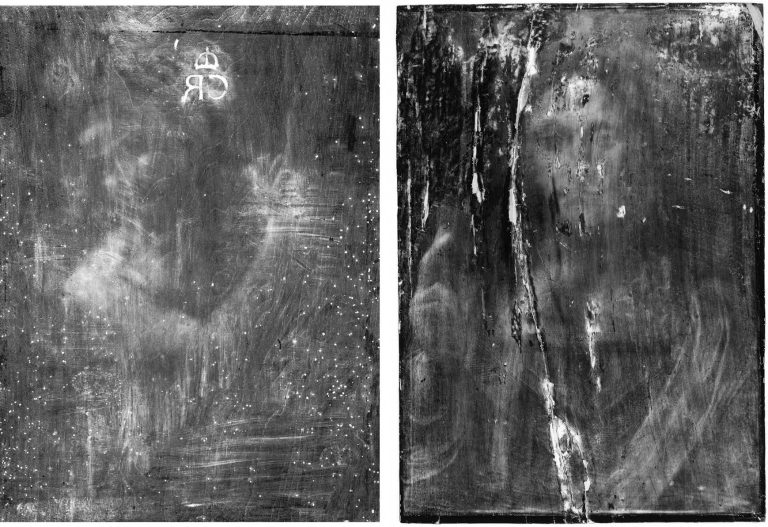

IV: (A) X-ray testimony, (B) Christ’s curls

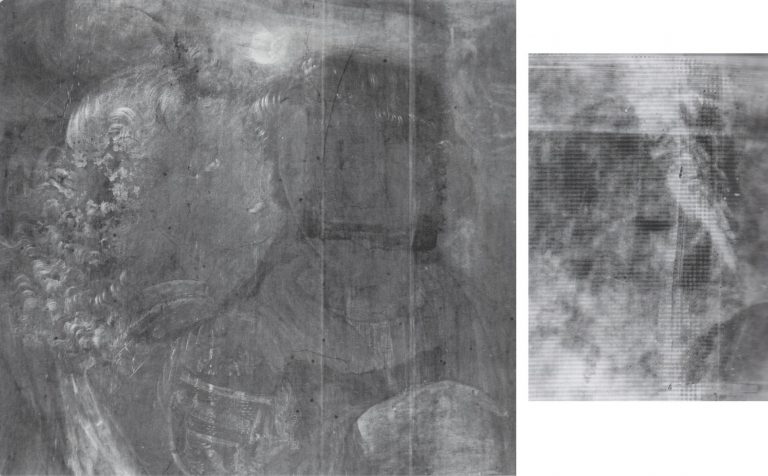

Another case in point is the typology of the X-radiograph image of the panel painting, which is also described in a tendentious manner that would leave no doubt about the work’s authenticity: “The X-radiograph of the picture displays the same ghostly image as is seen in the Saint Anne, the Mona Lisa and Saint John-the-Baptist, which is a typical feature of Leonardo’s works after 1500” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 38).

(A) – Once again, the reader is supplied with no contextual information that would otherwise disclose its arbitrariness. To my knowledge, no systematic and critical survey has been undertaken until now on the X-ray images of the Leonardos of that period with regard to X-rays of the studio’s productions, which exercise proves highly instructive (see below). Besides, the X-ray images of Leonardo’s own paintings, whatever the period of their creation, show a great variety of aspects depending, firstly, on the nature of the preparation, and secondly, on the particular technique used in the coloured layers of the paint film, and this is most especially the case in the flesh sections. For example, from roughly 1500 onwards Leonardo uses less and less lead white in the flesh paints of his figures, which abstemiousness results in the pictures’ ghostly looking radiographs whose aspect is very different from those of earlier works like the Lady with an Ermine (c. 1490) or the Belle Ferronnière (c. 1495). In the latter, the use of lead white was substantial. However, in Leonardo’s case such matters should not be simplified according to his oeuvre’s chronology : unexpectedly, one can see a marked similarity between the blurred, practically illegible X-radiograph of the head of Leonardo’s Angel in the Baptism of Christ (1472-1475) and that of Saint Anne in the Louvre’s Virgin and Child with Saint Anne painted thirty years later (c. 1501-1517), (Fig. 16, below).

Above, Fig. 16: left, Verrocchio and Leonardo, The Baptism of Christ, before 1470/ 1472 -1476 (?), tempera and oil on poplar, 177 x 151 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, X-radiograph of Leonardo’s Angel’s head (painted in oils); right, Leonardo, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, oil on poplar, 168 x 130 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, X-radiograph of Saint Anne’s head.

Above, Fig. 17: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, X-radiograph; right, Leonardo and studio (including G.A. Boltraffio), The Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1493-1499 (?)/1506-1508, oil on poplar, London, National Gallery, 189.5 x 120 cm, X-radiograph of the Infant Saint John.

Above, Fig. 18: left, Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist, c. 1510-1517, oil on walnut p, 69 x 57 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, X-radiograph; right, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, X-radiograph. In the X-radiograph of the Louvre Saint John the Baptist, one’s eye can grasp but few elements of the composition as seen in visible light (the pointing hand is illegible and the Saint’s austere garment doesn’t show at all), whereas Salvator Mundi’s X-ray image is much more consistent with the work’s aspect in visible light.

As just suggested, unless it were to be studied in the future by a cross-disciplinary team closely and rationally, this X-ray issue remains unclear and susceptible to misinterpretation. For myself, I have noticed through years of examination of the X-radiographs of Leonardo’s original paintings in the Louvre that none of them displays an image entirely consistent with that seen in direct light: when one or more details of the work can be identified on the radiograph without problem, the rest is not. In other words, the relating compositions are at best partly legible, not more. This is not the case with the Cook Salvator Mundi, whose X-ray image is misty indeed, yet reasonably consistent with what the painting looks like in day light, a legible aspect due to a very regular and even distribution of lead white over the whole composition, used for shaping and modelling in a conventional, unimaginative fashion. This resembles the use of lead white encountered in what is considered to be Boltraffio’s brush in the London National Gallery’s Virgin of the Rocks (Fig. 17, above). In contrast, in Leonardo’s X-rayed brushwork the use of lead white appears both spontaneous and random, with no lead white where one would otherwise expect it. To me this is exactly where stands the subtle, yet distinct border between the Master and his assistant(s) (Fig. 18, above).

Adding a touch of complexity to this appeal for caution with regard to the interpretation of X-ray documents close to Leonardo and his circle, the noteworthy fact stands that, in terms of typology, the X-radiographs of Salai’s Head of Christ and that of the Ganay version of Salvator Mundi are not legible at all and, in some ways, resemble the X-radiograph of the Louvre Saint Anne (Fig. 19, below).

Above, Fig. 19: left, Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called “Salai”, Head of Christ, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, X-radiograph; centre, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, the Ganay version of Salvator Mundi, oil on walnut, 68. 2 x 48.2 cm, Private Collection, X-radiograph; right, Leonardo, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, Paris, musée du Louvre, X-radiograph.

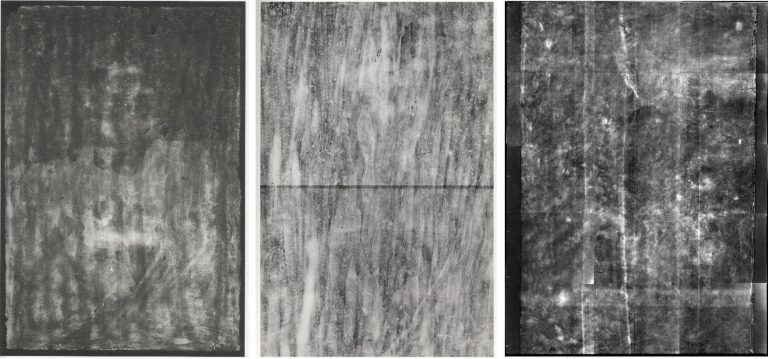

Above, Fig. 20: details, left, Leonardo, Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1474-1475, tempera and oil on poplar, 38.8 x 36.7 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art, detail of hair; centre, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail of hair; right, Verrocchio and Leonardo, The Baptism of Christ, Florence, tempera and oil on poplar, c. 1468 – 1470/ 1472 – 1475 (?), 177 x 151cm, Uffizi Gallery, detail of Leonardo’s Angel’s hair.

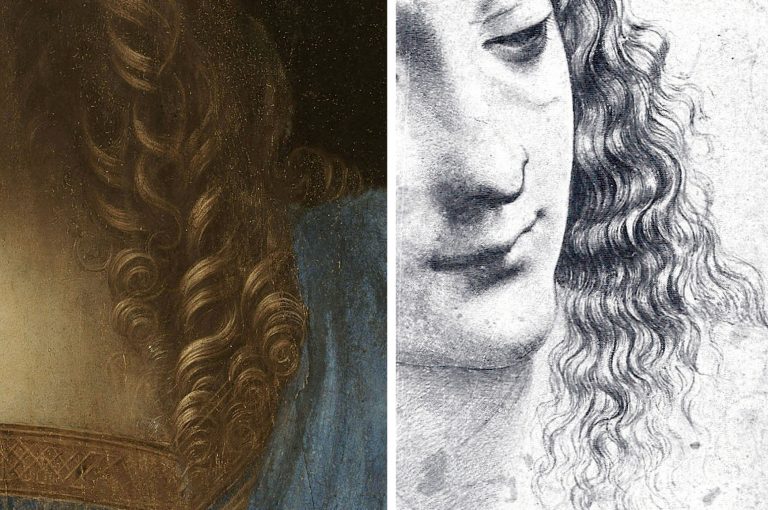

(B) – The book’s authors’ espousal of Christ’s ringlets – which they compare to Leonardo’s superb hair in the Louvre Saint John the Baptist – is also disconcerting for many reasons. “The curls falling on [Christ’s] proper left shoulder are rendered lavishly (…) Their technique is reminiscent of those of Saint John-the-Baptist in the Louvre.” (Delieuvin, 2019 p. 16) “The hair is partly damaged and the best-preserved zones are the curls falling on the proper left side of Christ’s face (…) The very fine execution of these curls is remarkable and is reminiscent of [Leonardo’s] Saint John the Baptist’s magnificent curls” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019 p. 34 -36).

The curls in question are certainly painted with extreme delicacy but are they really reminiscent of the Saint’s hair in the Louvre Saint John? Not really, in my opinion, for the style of these ringlets, not only does not resemble the hair executed by Leonardo in his late period, it is nowhere seen in any of his paintings except, perhaps, for a slight resemblance to the permed ringlets in the Portrait of Ginevra de Benci, which picture, however, dates to c. 1475 (Fig. 20). Such a period rules out the possibility that Leonardo would have gone back to his early Florentine style, as best perceived in his Angel in the Baptism of Christ, to paint the Cook Salvator Mundi’s ringlets of c. 1505-1510. The latter’s otherwise systematic and careful treatment (in the fine passages) induces my feeling that Boltraffio’s brush is not strange to their precious chiselling (Fig. 21, below), which, oddly, resembles an earlier style in the treatment of hair, such as that executed in a somehow close technique in Antonello’s Ecce Homo of 1475 in Piacenza, as at Fig. 22, below.

Above, Fig. 21: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail of hair; right, G. A. Boltraffio, Study for the heads of a Madonna and Child, silverpoint on paper, 29. 7 x 22 cm, Chatsworth, Duke of Devonshire and Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, detail of Madonna’s hair.

Above, Fig. 22: left, Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo, 1475, oil on wood (oak?), 48.5 x 38 cm (painted area 43 x 32. 4 cm), Piacenza, Collegio Alberoni; centre, Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo, detail of hair; right, detail of hair from the Cook version of Salvator Mundi. The painting technique employed in Salvator Mundi’s hair by Leonardo’s assistants c. 1510 is close to that of curly hairs executed by Antonello thirty-five years earlier.

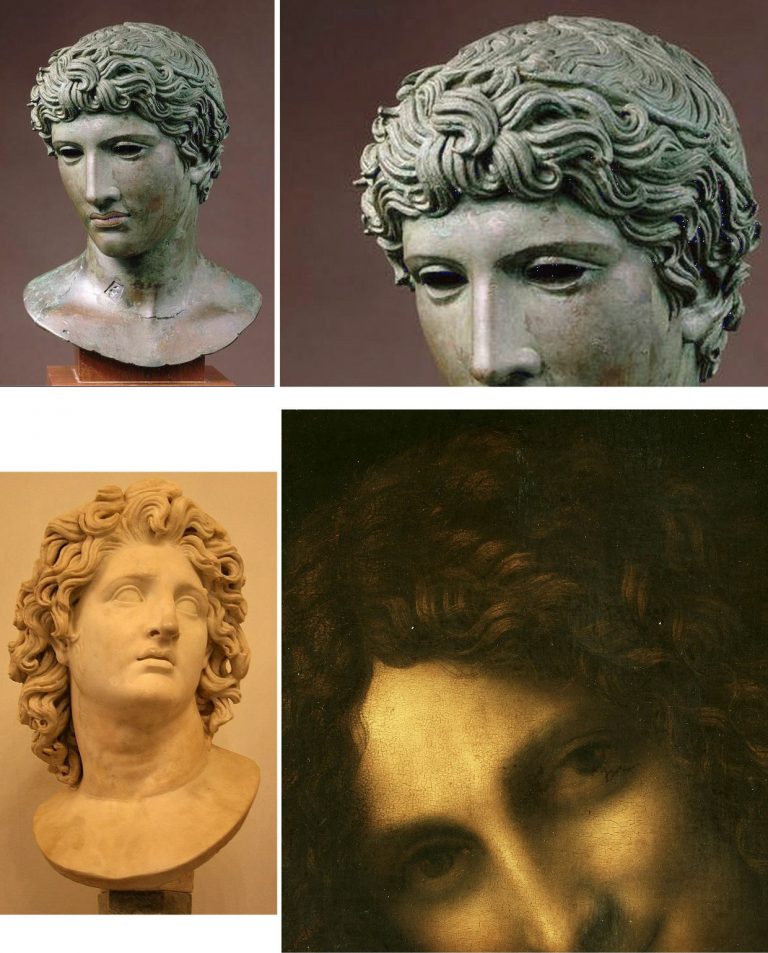

Above, Fig. 23: top left and right, Herculaneum, Campania (Southern Italy), Head of a Youth (“The Benevento Head”), 50 BC, hollow-cast bronze with red copper veneer and inlaying, H. 33cm, Paris, musée du Louvre; below left, Alexander the Great as Helios, marble, Roman copy after an Hellenistic original from 300-200 BC, H. 58. 3 cm, Rome, Musei Capitolini. Below right: Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist, musée du Louvre, detail of hair.

In truth, the overall conception of Saint John the Baptist’s hair is far stronger and more masterly than that in the Salvator Mundi: its interweaving of the locks in complex snake-like waves is of a breath-taking beauty, and its originality, nowhere else then seen in Western art, testifies unquestionably to Leonardo’s close study of the Antique. Effectively, among many examples that could prove my point, The Benevento Head (c. 50 BC, Louvre) – as above at Fig. 23, top – or Alexander the Great as Helios in Rome (a marble copy apparently executed under the reign of emperor Hadrian) as above at Fig. 23, below left, both give an idea of the artist’s concerns with the Hellenistic and Roman sources determining his late style, although their perfect assimilation results in a formula entirely detached from any plagiarism. It is therefore evident that the somehow late Gothic touch that still survives in the Salvator Mundi’s well-arranged curls is symptomatic of a Leonardo imitator from his close circle.

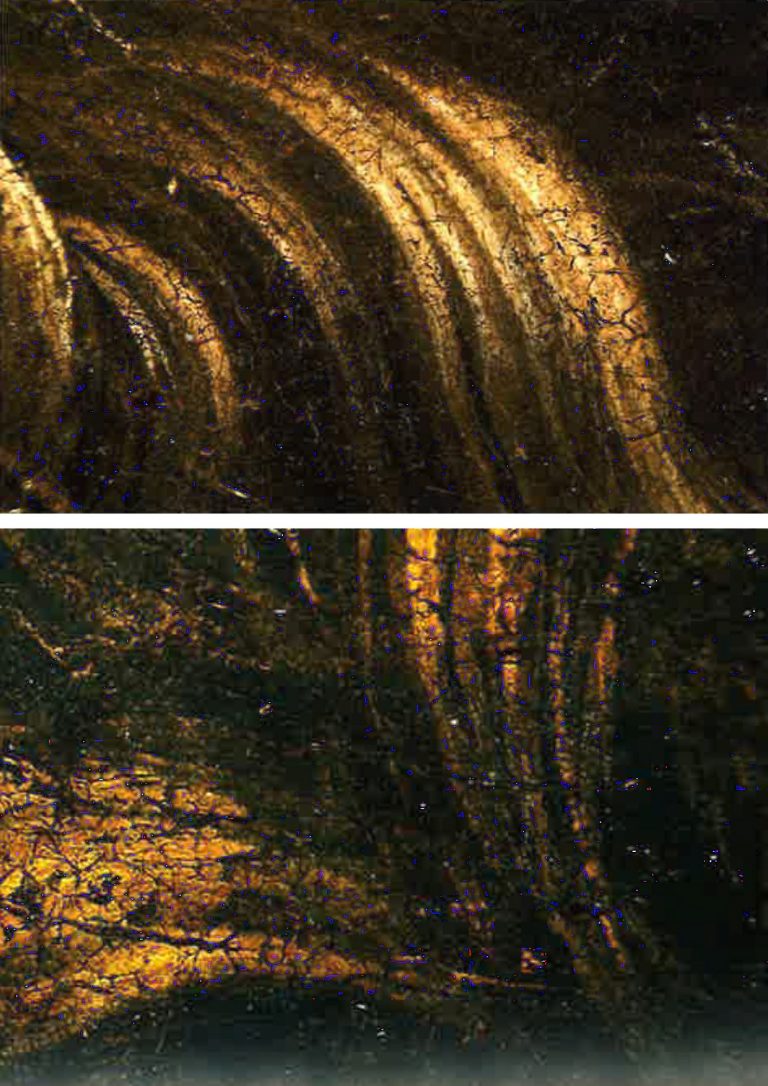

Above, Fig. 24: top, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail of hair viewed under optical microscope; above, Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist, Paris, musée du Louvre, detail of hair viewed under optical microscope.

Finally, one wonders why Eveno and Ravaud have taken the trouble to compare some selected but unfortunately too small details of the paint’s crazing network viewed under an optical microscope in the curls in both pictures (Fig. 24, above), thus trying to prove that Leonardo’s brush is identically discernible in the Salvator Mundi’s hair and in that of the Louvre Saint John. Too many unsafe parameters are involved here to make one comfortable with such a demonstration, and, additionally, it can be suspected that a studio work to which contributed, as I believe, Leonardo’s closest assistants, contains many materials employed by the Master also which, in his own works and in a studio item, would have aged through time practically in the same way. The authors’ position would be of greater interest if cross-section samples taken from both paintings might have demonstrated that the compared details’ layer structures and pigment compositions were reasonably analogous, which, apparently, is not the case.

V: Flesh paint

Above, Fig. 25: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai?) “The Prado Mona Lisa”, c. 1501-1510, oil on walnut, 76. 3 x 57 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado; right, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai?), The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (“The Hammer Saint Anne”), c. 1508-1513, oil on poplar, 178. 5 x 115. 3 cm, Los Angeles, University of California, Hammer Museum, Willits J. Hole Art Collection.

Neither essay deals as it should with the important issue of the flesh technique used in the Cook Salvator Mundi as one might especially expect. Delieuvin does not address the subject directly. He (unfavourably) likens the flesh rendering in the Ganay version of Salvator Mundi (Fig. 2, right) to that observed in two other studio paintings (The Prado Mona Lisa and the Hammer Saint Anne in Los Angeles, Fig. 25, above) so as to suggest that no match exists between the flesh paint in the latter works and in the Saudi painting: “The rosy flesh tints [in the Ganay version], made of thin red hatches, are similarly encountered in the Prado Mona Lisa and in the Saint Anne in Los Angeles (…) With regard to Leonardo’s original works, nowhere is found in them the elaborate sfumato effect and the soft transitions from light to shade giving the paint materials a vibrant looking aspect” (Delieuvin, 2019, p.18). In fact, with regard to technique, no sound comparison can be made between the flesh paint in the Hammer Saint Anne and that in the Prado Mona Lisa unless one understands, which Delieuvin regrettably does not, that it is one and the same process in different stages (Figs. 26, 27 and 29).

Above, Fig. 26: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, “The Hammer Saint Anne”, detail of flesh paint in Saint Anne’s face showing thin parallel hatching (initial stage of the “complex blending” technique), right, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, “The Hammer Saint Anne”, IRR of detail in Fig. 26, left, showing underlying thin parallel hatching (initial stage of the “complex blending” technique, whose full development can be observed in the Prado Mona Lisa, Fig. 27, below).

Above, Fig. 27: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, “The Prado Mona Lisa”, detail showing intermingled tiny brushstrokes of the advanced, yet unfinished, soft-focus modelling of the flesh using the “complex blending” technique. That process’ initial stage always uses hatches (see Fig. 29, below); the overall fuzzy effect is due to an impalpable coating of translucent paint laid by the artist, after each painting session, over the dried network of brushstrokes (tiny hatches and dots).

Nor is the C2RMF’s scientific investigation explicit about what is essential in the painting process of the Cook Salvator Mundi: the chronology and typology of the successive technical gestures that served for the artist’s creation. “The flesh sections have been built up in several stages. A rosy to dark beige underlayer is laid over the white ground preparation. Composed of lead white and ochres it substantially contains red [pigment] grains of vermilion as is revealed by mercury mapping and microscope examination. The superficial very thin layers strengthen the initial modelling [while] thin whitish glazes [sic] increase the clarity of the highlights [7]. Conversely, the shadows are deepened thanks to dark thin layers containing a substantial quantity of black [pigment] grains (…) but containing also a substantial quantity of [pigment] grains of vermilion. The relationship between shadow and vermilion shows in particular through mercury mapping in the well-preserved right hand. Calcium mapping shows this element’s significant concentration in the shaded flesh sections, thus suggesting that bone black was employed by the artist” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 36).

Once more it is very astonishing that the data provided here by Eveno and Ravaud have been considered decisive enough to attribute the Cook Salvator Mundi to Leonardo: all the pigments (and their specific tone), whether mineral (natural and artificial) or organic (natural and synthetic), mentioned in the quoted paragraph have been used by artists in the flesh paints in variable ways at all times since the Renaissance to our day. Despite the real interest of their pigment identification, no novelty emerges from that survey: any academically trained painter well knows that the flesh paint results from a traditional mixture of white, with a quantity of vermilion and some ochre, with a slight touch of black, the which mixture produces a beige hue that is first laid over the ground preparation and modelled so that the basic volume is rendered.

Above, Fig. 28: Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called “Salai”, Head of Christ, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, detail of the very subtle warm pink modelling in Christ’s face, susceptible to contain vermilion pigment as traditionally employed in flesh paints by Italian artists of the Renaissance like Leonardo and his studio (compare the flesh tints in the Prado Mona Lisa at Fig. 27 above).

When this underlayer is dry, the shading can be executed carefully using either a wide range of terras or, instead, given that the handling of these mineral pigments is somehow uneasy, a mixture of vermilion (mercury sulphide) and bone black, giving superb browns (according to the proportion of each colour): that mixture being more stable and very reliable in terms of handling, notably when highly diluted. For sure, the same or very similar pigment composition – by no means specific to Leonardo – would be detected in many paintings of his studio (to limit such an eventual research to that scope of Italian Renaissance paintings), and very probably in Salai’s Head of Christ of 1511 (Fig. 28, above), in which much of the volume is very finely modelled with vermilion red and possibly black containing warm browns. In this respect mercury or calcium mappings are not meaningful exercises unless extended to a number of studio paintings for comparison, which is not the case here. And even if it were so, the problem is less one of pigment identification (and in which proportions) in the Cook Salvator Mundi than how they have been handled during the successive stages of its creation so that the work might be ascribed to Leonardo – or not. Laboratory tests, however useful they are for dating, cannot stand in lieu of the indispensable visual assessment of the work’s intrinsic qualities as a work of art so as to support a plausible and unproblematic attribution to Leonardo

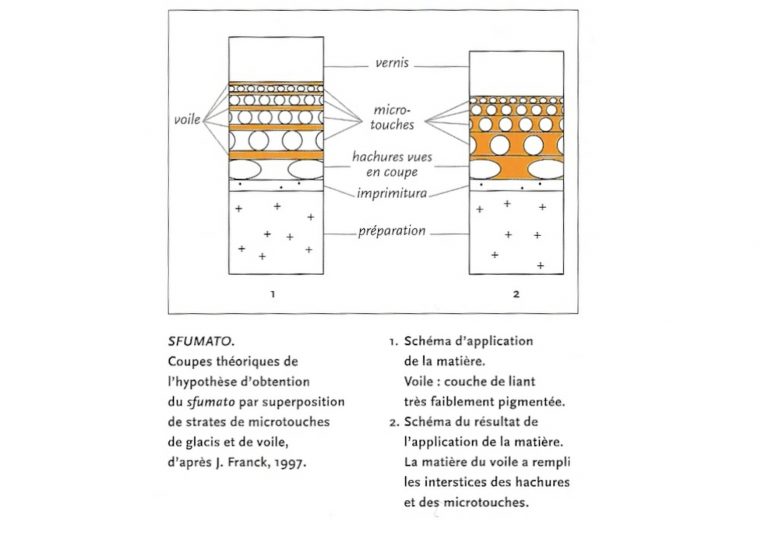

Above, Fig. 29: Theoretical cross-section showing Leonardo’s “complex blending” sfumato process. Diagram after Ségolène Bergeon Langle and Pierre Curie’s 2 vol. dictionary of art terms and techniques Peinture & Dessin, Principes d’analyse scientifique, Centre des Monuments Nationaux/ C2RMF ed., Paris, 2009, vol 1, p. 55.: 1 (bottom to top) : ground preparation, imprimitura, large hatches, medium size and thin hatches, interspersed layers of thin veils of translucent paint, micro-dots, 2 diagram of the end result: the interstices of the hatches and the micro-dots have been filled in by the paint materials of the veils (see fig. 27, above). The authors’diagram was established after my own ones published many times from 1997 onwards.

Above, Fig. 30: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, photograph in visible light (2006) before the Modestini restoration. This well-known reproduction of the Cook Salvator Mundi as it stands without the Modestini’s restoration inpainting displays a pinkish-brownish acid tone and a sfumato treatment departing from Leonardo’s paradoxical effects of simultaneous haziness and preciseness of the form.

To revert to Delieuvin’s brief analysis of the painting process: his imprecision merits further comment. The Louvre curator mentions the fine hatching observed in Saint Anne’s face in the Hammer Saint Anne in Los Angeles and in the Prado Mona Lisa as if the technique used for the flesh modelling in both paintings was fully completed in each case, thus likely to be compared. This interpretation’s inadequacy and ambiguity calls for precision (Figs. 25, 26 and 27). In those two studio works one can observe that the flesh modelling results from a process whereby the volume is built up thanks to a network of hatches; long rather thick ones first; then shorter and thinner ones; thus testifying to the very traditional construction of three-dimensional effects, whether drawn with a pen or a brush. Then comes a more complex stage in which the medium size hatches cannot be used, and so for mechanical reasons, to render with utmost accuracy the softest subtleties encountered in the flesh sections, especially in a face, for these subtleties take up very small areas, even microscopic ones, hence the use of appropriate hatches, necessarily thinner and shorter, and so on and on, up to a stage in which the tiniest hatches become practically imperceptible dots (Fig. 29). In fact, contrary to misinformed theories one cannot paint details smaller than the tip of the brush used [8].

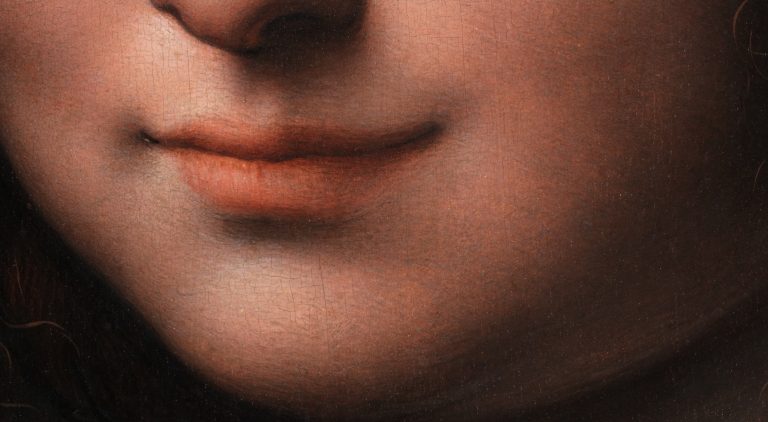

When each working session is completed, ultra-thin unifying veils of translucent paint are laid over the dry underlayer by the artist in order to conceal the tiny strokes, still visible, and, thus, to make the flesh look smooth and even. It is the technique employed in the Mona Lisa at an unprecedented level of refinement, which I call Leonardo’s “complex blending” as opposed to his “simple blending”, that is the traditional way of obtaining soft-focus effects (see my above Prologue) (Fig. 29). Taught by Leonardo himself to his pupils and collaborators, this global process is observed in the Hammer Saint Anne, where the network of hatches, mostly visible in the underlying layers thanks to IRR imaging, has not reached the stage of tiny strokes which is otherwise observed very conspicuously in the Prado Mona Lisa (Figs. 26 and 27). In this painting, advised by Leonardo in all certainty and copied next to the original from start to finish (by Salai very likely) the full deployment of the various hatches – long, medium, very small or microscopic – is observable. The fact that all these different paint strokes are seen to coexist in the Prado Mona Lisa is a clear sign that the copy is unfinished. It is, therefore, technically and historically wrong to describe the technique used as hatching because, properly speaking, the technique present must accommodate that encountered in the more finished areas – the section around the chin and the sitter’s lower proper left cheek – where the full complex blending process is distinctly discernible. Properly appraised, the Prado copy constitutes a most precious document, because its only partial completion discloses the preceding means by which the highly polished and flawlessly transitioning flesh paint in the Louvre Mona Lisa had been obtained [9].

Above, Fig. 31: top left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, photograph in visible light (2006) before the Modestini restoration, detail of head; top right, Leonardo, The Mona Lisa, Paris, musée du Louvre, detail of head [s.]; below left (as in top left); below right, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai?), The Prado Mona Lisa, detail of head. Bar the damage in the Cook Salvator Mundi, the neatness of the sfumato making is close to that observed in The Prado Mona Lisa. Da Vinci’s overall soft-focus effect is imitated well but not the supremely refined, yet just allusive, anatomical precision and the staggering rendering to the life which belong to Leonardo alone. One can well see that the overall drawing and the sfumato modelling are highly perfect in the Louvre Mona Lisa and that they are limp in both the Prado copy and the Cook Salvator Mundi (presumed to be by the same artist, Salai).

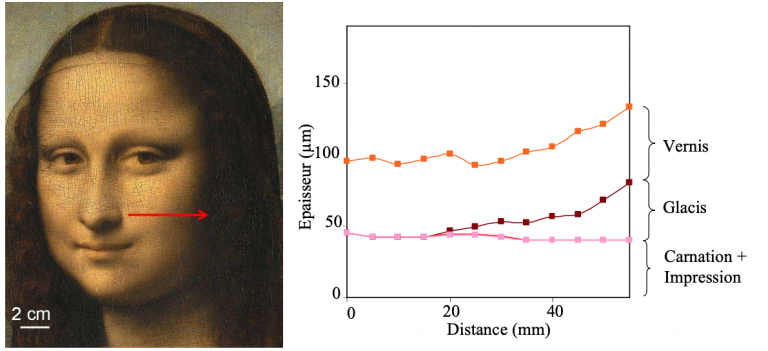

Above, Fig. 32: After Laurence de Viguerie, Propriétés physico-chimiques et caractérisation des matériaux du sfumato (Doctorate of Science, 2009), fig. 99 p. 241. X-fluorescence cross-section reckoning alongside The Mona Lisa’s face (my provisional translation). The modelled shadow (“glacis” = glaze) is laid over the pale, lead white containing, flesh paint underlayer, spared in the lights.

In any event, the technique used in the Cook Salvator Mundi had not given the flesh zones the vibrant aspect which Delieuvin both attributes to it and holds to be itself typical of Leonardo’s own flesh painting. To fully understand my objection, one should examine the photograph of the Cook panel painting as it stood before Modestini’s restoration inpainting, as is encountered in a document which has now been publicized world-wide (Fig. 30). When I first examined that state from a large reproduction, it was possible to read and mentally reconstruct the work’s overall image in spite of the enormous damage lying beneath the recent repaints. Then, I could see more clearly what is foreign to Leonardo’s method in the execution and, for that reason, what is much closer to his assistants. Contrary to what the Cook picture’s advocates claim, its sfumato effects are not identical to those seen in the Louvre’s autograph Leonardo paintings. Specifically, in the illuminated parts, the Cook picture’s flesh displays a pinkish-brownish acid tone and a milky/chalky texture that is never to be encountered in any Leonardo that I know. In addition, even where it is handled finely in the better-preserved sections, the soft-focus effect has too much evenness and continuity – which is to say, a formulaic simplification – to be really faithful to Leonardo’s supreme art, wherein, no detail, either anatomical or of any other kind, is “eaten up” and lost within the mistiness of the sfumato treatment. To the contrary, in Leonardo, each and every detail’s realism and veracity is respected, the more so as through the overall smoky veiling one can feel the presence – more than actually see – of, here, a faintly contracted cheek muscle, elsewhere, of the orbital and cheekbone construction, or of the elasticity of the flesh in movement in a face (Fig. 31).

To my knowledge, the difference in aspect between the Salvator Mundi and the Mona Lisa, for instance, lies in the nature of the making and this might now be explained thanks to the joint researches of Laurence de Viguerie and Philippe Walter (former C2RMF scientists) on Leonardo’s sfumato technique and materials [10]. As observed in the diagram above, taken from Viguerie’s doctorate of science (2009), it is clear that Leonardo builds up the shadow on a pre-existing lead white containing underlayer serving partly as a base for creating the illuminated flesh sections. In effect, while starting at the underlayer level, the shadow’s own layer rises as it extends toward the deepest darkness, as opposed to the exposed parts of underlayer which have been left intact to serve for the lights (Fig. 32). Thus, apart from the highlights of lead white added at more advanced stages, it can be recognised that little of this pigment will be really needed to achieve the less luminous surrounding flesh tints. Finally, and in marked contradistinction, we know from the work’s X-ray image that the use of lead white in the Cook Salvator Mundi is substantial and that this usage explains the milky-chalky aspect of the flesh (in strictly technical terms, that this is due to the pigment’s marked opacity with a refraction index running from 1, 94 to 2, 09, in modern pigments), an aspect not seen in the Mona Lisa, whose paint surface is more evanescent and transparent.

Conclusion: “studio work” is what science really says

The reader surely understands now why it was necessary and urgent to demystify the severe misinformation that has circulated in the international press in the past months in the form of claims that the Louvre actually holds the Cook Salvator Mundi to be an authentic Leonardo while refusing to declare its true position. That most paradoxical conspiracy theory must be rejected on its own absurd implications. We are asked to believe that the Museum had required the loan of a Leonardo painting, whose authenticity was confirmed by the institution’s in-house laboratory (C2RMF) but, despite this positive verdict, the curators of the 2019 Leonardo exhibition had, on no justification, not only not shown the work but had also downgraded its artistic status in the catalogue. Of necessity, the real story is more straightforward: the Louvre Museum had no objective reason to be so discourteous to the owner, otherwise respectable and prestigious, who, in addition, had most obligingly put the picture at its disposal for many months, in order that it be examined thoroughly by the C2RMF scientists and researchers.

Far more credible and likely is the explanation given in the Vitkine film. Before the growing contestation of the Leonardo authorship that had amplified from 2018 onwards universally, and reached its highest peak in April 2019 following the publication of Ben Lewis’ book of journalistic investigation The last Leonardo (in which it was revealed that, contrary to what had been stated urbi et orbi in the media coverage preceding the New York sale in November 2017, no real scholarly consensus had ever existed over the attribution of the Cook Salvator Mundi to Leonardo), the Louvre could not but feel ill at ease. Da Vinci is not just any name; the French Government had all the reasons, in the Summer of 2019, to require that the painting be further examined and tested in-depth before appearing as the guest star in the blockbuster show then in preparation at the Louvre. Much was at stake in terms of national prestige. The Louvre could not afford to declare and label a work as a restoration-retrieved Leonardo masterpiece without a scholarly unanimity strong enough to silence all dissenting voices. It cannot be doubted, therefore, that the Louvre’s own earlier scientific tests were peer checked according to a sole crucial criterion: does unquestionable evidence exist that the Cook Salvator Mundi was painted by Leonardo in person? In the light of what has previously been discussed here in many points, the answer, which would jump to any serious physicist and chemist’s eyes at first glance, is of course “NO”, because the material gathered from the tests (not to speak of the arguable methodology of approach) was of too little weight to urge the Louvre to risk anything beyond a studio attribution [11].

All else is just like Hamlet’s famous response to Polonius’ question: “Words, words, words” (Act II, scene II) and it might well continue vainly like this for some time in the media and the academic literature. The problem must be addressed serenely: no trick, no magic wand will disperse it and make the Cook Salvator Mundi become one day or another what it is not and never was. The reality is immutable.

CODA:

Above, Fig. 33: Left, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, The Madonna Litta, c. 1491-1495, tempera on wood transferred to canvas, 42 x 33 cm, St Petersburg, The State Hermitage; right, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, The Virgin and Child, c. 1495-1497, Budapest, Szépmüvészeti Múzeum.

It will be profitable to compare the Madonna Litta, to date attributed to Boltraffio rightly, and his Esterhazy Virgin and Child in Budapest, both painted in the years Giovanni Antonio spent with Leonardo. Not only has Boltraffio assimilated da Vinci’s manner in a brilliant – yet secca – fashion, as above, Fig. 33, one can well see the resemblance of the sfumato modelling, in particular in the Infant’s anatomies and also in what remains of the Cook Salvator Mundi, as above in Figs. 30 and 31. Adding mentally to the latter work Salai’s contribution, whose own style is mellow and misty in the flesh sections, as proven by his Head of Christ in the Ambrosiana (Figs. 11 and 28), the Saudi painting emerges as a hybrid item meant to simulate a “fully by Leonardo” devotional composition, much like the Madonna Litta, yet without the Master’s contribution to the actual making. If not this, then new theories will have to deal with the thick sketching-out contour lines seen identically and successively in Salai’s Head of Christ, in the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, in the Ganay version of Salvator Mundi, and bring contrary supporting scientific evidence and demonstrations [12].

I wish to thank Michael Daley warmly for welcoming this second contribution of mine on the ArtWatch UK website and for having adjusted its presentation with the utmost care and kindness.

Jacques Franck, 16th December 2021

ENDNOTES:

1 This survey has been published online before (a couple of years ago), in part at least, and had not reached then the neutrality observed to date. I might quote the previous version here if necessary in a future revision.

2 Cf. Dianne Dwyer Modestini, “The Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci rediscovered. History, technique and condition”, in Leonardo da Vinci’s Technical Practice, Paintings, Drawings and Influence, Michel Menu editor, Paris, 2014, p. 139-151.

3 Cf. Elisabeth Ravaud and Myriam Eveno, “La Belle Ferronnière: a non-invasive technical examination”, in Michel Menu, op. cit. supra, note 2, p. 126-138. Scientific tests have been carried out on the Lady with an Ermine in 2012 by scientists from the National Museum in Kracow jointly with several specialists, in particular from the Getty Conservation Institute and Yale University. In that essay, nowhere is stated that the paint sample taken in 1960 has been reexamined in 2012. While glass particles are not mentioned either, a small part of the preparatory layer has been analysed using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy: a thin layer of lead white has seemingly been laid on the whole surface of the panel, an observation needing confirmation. In effect, the latter technical method is a non-invasive one, thus far less reliable and conclusive than the analysis of cross-sections of paint materials taken from original works (see the above Prologue on that very issue regarding burnt umber in the Mona Lisa). Cf. Lukasz Bradasz, Michal Lukomski, Johanna Sobczyk et al., “Leonardo da Vinci Lady with an Ermine – The latest research into the artist’s painting technique and the state of preservation of the painting”. (Checked on 4 November 2021.)

4 For colourless powdered glass as paint additive and drying agent “much used in Italy”, see Marika Spring, “New insights into the materials of fifteenth-and sixteenth century Netherlandish paintings in the National Gallery, London”, Heritage Science 5, 40 (2017).

5 Cf. Diane Dwyer Modestini, in Michel Menu op. cit. supra, note 2.

6 In fact, the IRR of the Cook Salvator Mundi published in Beaux-Arts Magazine (Daphné Bétard, “Salvator Mundi, les dessous de la vente du siècle”, BAM 403, January 2018, p. 100-105) was the late one of the restored stage with the black illegible background. It was the only full IRR document available then. Just a detail of the full IRR scan before the inpainting process was to be seen in Modestini’s article cited supra note 2 (fig. 9, p. 147); the full document will be released on the American restorer’s website in August 2020 (see “Further thoughts I”, caption to Fig. 9).

7 No stricto sensu glazing can be made with lead white, which is an opaque pigment having a high refraction index. Glazes are made with pigments like red lakes, copper resinate (green), etc., whose refraction index is low enough to be close to that of the oil binder. The authors therefore allude to thin whitish translucent veils of paint in the highlights.

8 The publication in 1969 of Thomas Brachert’s fundamental investigation into Leonardo’s “handprint” painting technique, while being fascinating, has created much confusion about the exact context of this technique’s utilization in the Master’s works. It is true that Leonardo has used his fingers for swiping and dabbing the film paint, either in the early creating process of his works, as seen in the unfinished ones like The Adoration of the Magi and Saint Jerome, or in the more finished ones like the Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, The Lady with an Ermine or The Virgin of the Rocks in London. Yet except mine (in preparation), no critical research has been undertaken until now in order to clarify and explain technically, among a variety of handprint gestures, which specific ones served for what and how. It is clear, however, that microscopic details of modelling like those seen in The Mona Lisa’s face could never have been achieved with the palm of the hand, a thumb or the tip of the artist’s little finger. A painting instrument, whether a brush or a “digital instrument”, whose surface is 50 to 100 times larger than that of the detail to reproduce, is certainly not of any help in such making (see Prologue above). That seems sensible and obvious mechanically, but the Leonardo scholarly literature is full of misrepresentations of this kind regarding Leonardo’s “handprint” painting technique. Cf. Thomas Brachert, “A Distinctive Aspect in the painting Technique of the “Ginevra de’ Benci” and of Leonardo’s Early Works”, Report and Studies in the History of Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington,1969, p. 84-104; Jacques Franck, “Fondu simple ou fondu complexe? Le geste technique dans le cas du sfumato de Léonard de Vinci: ses paramètres”, Résumés des interventions, 3e Congrès de la Société française d’histoire des sciences et des techniques, École Normale Supérieure, Paris, 4-6 septembre 2008, p. 8-10; Jacques Franck, Léonard de Vinci: la technique picturale, histoire, concept et structure du sfumato, Thesis, Diplôme de l’École Pratique des Hautes Études (Paris, IVe Section, Sciences historiques et philologiques). In preparation.

9 This particular aspect is an essential one to understand my point. Specialists who do not practice traditional art and, specifically, copy-work, produce inevitably wrong interpretations of old master painting techniques. Having no such experience, although their eye might be, at best, a good one, in their mind they visualize neither the creative making as if it were being processed before them, nor its overall technical sequencing : that is why they never describe and explain it consistently. A paint layer is like a musical score which musicians alone can decipher as it should, and so is the case with (specialized) painters examining a painting (see Prologue above).

10 Cf. Laurence de Viguerie, Propriétés physico-chimiques et caractérisation des matériaux du sfumato, thèse de doctorat de sciences de l’université Pierre et Marie Curie, C2RMF, Paris, 2009; Philippe Walter, Laurence de Viguerie, Jacques Castaing, “Appareils portables pour l’analyse des œuvres d’art aux rayons X”, Images de la physique, CNRS, 2011/2012, p. 79-85; Philippe Walter, “Peinture et chimie. Comprendre le geste du peintre dans son atelier. Approches croisées entre chimie et histoire de l’art”, Cont@cts, Bulletin de l’Association royale des ingénieurs diplômés de l’Institut Meurice, juillet-août-septembre 2015, p. 10-14, (www.ardim.be: checked 16 December 2021).

11 The art market has been constantly agitated over the Salvator Mundi saga since the 2017 Christie’s sale of the picture in New York with new developments and feverish speculations about its attribution and fate every now and again. The art journalist Ben Lewis, not specifically specialized in Leonardo scholarship, just well-known for his book, The last Leonardo (2019), now bravely treads on dangerous grounds, i. e., painting technique, yet while ignoring established facts (the scientific, artistic and contextual evidence pointing to Salai and Boltraffio), and without any critical demonstration or scientific support, attributes boldly the Cook Salvator Mundi to Cesare da Sesto (1477-1523), based on Cesare’s St Jerome of c. 1520, a painting strange to Leonardo’s style and technique produced after the Master’s death in France in 1519, which, therefore, was clearly not executed under his direct supervision or influence. Cf. Ben Lewis, “Searching for the smoking thumb: a Salvator Mundi Paragone”, in Paragone. Leonardo in Comparison (Studien zur internationalen Architektur), Johannes Gebhardt and Frank Zöllner eds., Petersberg (Germany), 2021, p. 20 – 41. The same author states p. 38 that, in my opinion, the heads in the Saudi Salvator Mundi and in Salai’s Head of Christ (Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana) are in analogous proportions but I do not think so and have never written any such consideration: if it were the case, it would not change the identical sketching-out technique showing thick, emphatic contour lines on the IRR scans of both paintings. Mr. Lewis also doubts (p. 39) that the Cook Salvator Mundi painting could have been executed by two artists jointly (as was, nevertheless, so often the case in Italian Renaissance botteghe), but the recent scientific confirmation that the blessing hand was a change – stricto sensu – and not a pentimento, is a clear sign of the work’s heterogeneous execution and further supports the pertinence of my above-mentioned theory.

12 Seemingly, however, the tide is turning. In its November, 2021 issue, The Art Newspaper disclosed: “The Salvator Mundi which sold for $450m at Christie’s as a fully authenticated Leonardo, has been downgraded by curators at the Prado (…) The downgrading comes in the catalogue exhibition Leonardo and the copy of the Mona Lisa which runs in Madrid until January 2022. Although individual specialists have questioned the status of the Gulf Salvator Mundi, the Prado decision represents the most critical response from a leading museum since the Christie’s sale (…) The opening essay of the Prado catalogue is by Vincent Delieuvin, curator of the Musée du Louvre’s important 2019 Leonardo retrospective. He discusses the various views on the Gulf Salvator Mundi without giving much of his opinion, although he does refer to ‘details of surprisingly poor quality'”. Delieuvin’s unexpected comments on the painting are certainly an astonishing novelty: let us observe that those clumsy details were from the beginning the very reason why so many objections were raised by international specialists, and, therefore, why the Saudi Salvator Mundi never was and never will be a Leonardo.

It should be pointed out that in both the withdrawn first version of the exhibition catalogue (of the 2019 Leonardo show at the Louvre) and the Louvre’s junked scientific booklet issued in December of the same year, the Cook Salvator Mundi‘s then owner was stated as: ” Ministère de la Culture, Royaume d’Arabie Saoudite” (Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia Kingdom). In the reprinted and final version of the catalogue of that exhibition, the owner of the reproduced Cook Salvator Mundi (as in above Fig. 2, left) had become “Collection privée” (Private Collection). [Note, 26 December 2021] Following the publication of “Further thoughts II”, some objections have been raised here and there whereby the Louvre had not downgraded the Saudi painting in the final version of the 2019 exhibition catalogue but merely changed its mode of presentation in order to conform to the rule in force in the French museums, according to which works from private owners that are not loaned – thus not exhibited – cannot be authenticated in the latter institutions’ publications, notably when they are reproduced. While I shall not discuss why the owner in the withdrawn books differs from that in the above-mentioned catalogue of the 2019 Leonardo exhibition, it must be stressed that the Louvre Museum’s intentional downgrading cannot be doubted in the least way. In effect, the Saudi painting’s artistic status (“Cook version of Salvator Mundi“) was put at the same level as that of notorious studio versions, like the “Ganay version of Salvator Mundi”, and also, quite drastically, like the “Naples version of Salvator Mundi” (Naples, San Domenico Maggiore, exh. cat. Paris, Louvre, 2019, Fig. 103, p. 304): that very version is, of necessity a studio item, because its artistic quality is so low that Leonardo’s contribution is excluded automatically. Had the Louvre not meant to downgrade the work, why then reproduce side by side the Cook version and the Naples version in the 2019 catalogue in question with an identical status (p. 304-305)?

Leave a Reply