Iconoclasts, Replicators and Nostalgists

Orielensis Selby Whittingham on the agitation to remove Cecil Rhodes’ statue at Oriel College, Oxford. Painter/restorer Barbara Bibb on The Day Before the Fire. University College London Professor, and Geographer of Culture, David Lowenthal ~ The Past is a Foreign Country – Revisited

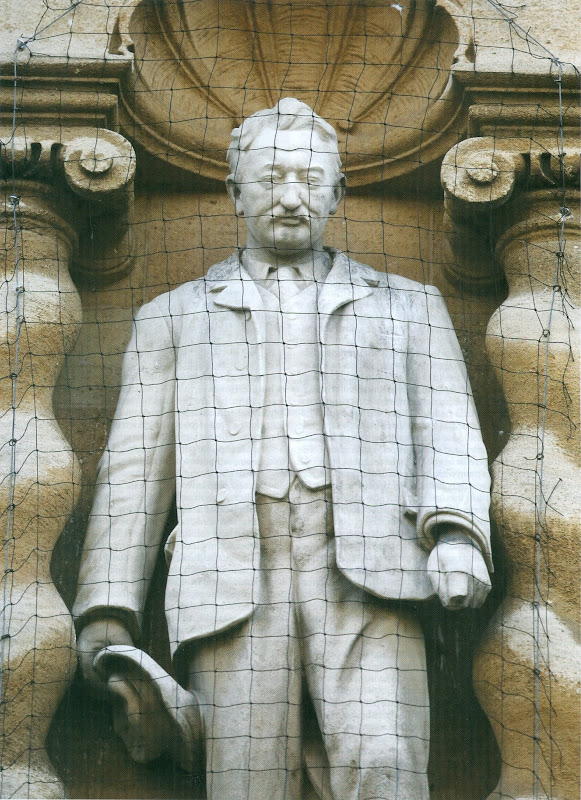

The arguments over the Cecil Rhodes’ statue at Oriel College, Oxford, have filled countless newspaper columns for weeks, the conservative press and nearly all its readers (along with the university’s chancellor, vice-chancellor, two other colleges and many students, if not a small majority against in an Oxford Union debate) in favour of it staying, the Guardian supporting the condemnation of Rhodes and Oriel College sitting on the fence, but leaning towards capitulation to the protesters.

TWO CONSIDERATIONS ARE PARAMOUNT

1. The statue is part of a Grade II* building. As such it cannot be removed without authorisation. The grading of the building may be questionable, but, being what it is, permission to remove would be deplorable.

2. The building (and so statue) was built with money from Rhodes. Though that does not constitute any legally binding requirement to keep either, it would morally be wrong (not “costless” as Orielensis Geoffrey Bindman QC says) to dishonour the donor, while keeping the money and building, not least when Oriel has lauded the latter (its annual Record, 2011, 2014) and indeed Rhodes.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS MERELY CONFUSE THE ISSUE

1. Freestanding statues erected to honour dictators etc. are regularly removed or destroyed. But this is a statue of a donor attached to a building for which he paid, like that of William of Wykeham at New College, Oxford. The removal of which other similar statues do people justify?

2. Rhodes was a mixture of good and bad according to some authorities. The protesters see him as wholly bad. Nelson Mandela and others have taken a more balanced view. The protesters have not given detailed counter-arguments. They are not so much interested in the statue or Rhodes as using these as a handle to get better African recognition at Oxford. Maybe there should be an Oxford Institute of African Studies (with a statue of whom? Mugabe is one candidate of Matthew Parris, but that is a separate issue).*

3. Prof. David Lowenthal argues that “the past is a foreign country” and one should not judge Rhodes by the standards of today. The Guardian replies that it roundly condemned Rhodes at the time of his death.

4. Matthew Parris says he is a great admirer of Rhodes and supports the retention of the statue, but only if a statue of the African king whom Rhodes is said to have swindled is erected in the college. Apart from a conventional lifesize one not being visually equivalent and not readily accommodated in any of the quads (maybe a bust in some corner of one or indoors would be practical), this is a weak concession ignoring the two key points listed above if acted on as a quid pro quo. It is back to the indefensibly weak and unprincipled response of the college so far.

Selby Whittingham (Oriel College 1960-64: Secretary-General, Donor Watch). 2 March 2016.

(* It could study, inter alia, Journal of a Residency in Ashantee, dedicated 1824 to George IV, by the son-in-law of Turner, Joseph Dupuis, viewable with Dupuis’ illustrations of Africans, in whom he took an interest, online via Google! One might also more constructively support the campaign of the late Bernie Grant MP for the return of the Benin bronzes – Benin came into the Ashantee story.)

The Day Before the Fire by Miranda France, 2015, pub. Chatto and Windus (part of The Penguin Random Group of publishers).

A stately home on the outskirts of London is razed to the ground by fire, and a band of young conservators are tasked with the job of restoring it. They wish to carry out this work as sympathetically as possible; leaving the passage of time and accident still to be read upon close inspection of the surfaces. But the formidable owner, Lady Marchant, has other ideas: her plans are that the house should be returned to its condition the day before the fire, and she is seemingly unconstrained by any limitation of funds from her Insurers.

The young protagonist, Ros, who is to restore the 18th century wallpaper, says that her aim “is to tell the true story and not let people be tricked”; and “that restoration should always be visible to those who want to see it”; both “there and not there”. A great deal of immaculate, in-depth research has been carried out by the author, and a lively interaction ensues between Lady Marchant, her son Sebastion and Ros and Co. We are also privy to the inner workings of a team of accomplished restorers, their methods and machinations vis a vis the sometimes impossible demands of their clients.

Our interest is also drawn to the dilapidations and missing pieces of Ros’s own life. How much should be revealed and how much left to time to heal.This is also a rattlingly good tale of young Londoners, who are often constrained by lack of money, yet trying to hang on to their principles in the ceaseless scramble of London life.

Barbara Bibb, 2 March 2016.

(With an inscription from Ovid’s Metamorphoses:

“Oh, most voracious Time, and you, envious Age, you destroy everything.”)

“Everything distinguishable about the past is here…A book that you will enjoy if you know that the past attracts you, or if you think that you are immune to its power or its spell”.

~ Peter Laslett, Washington Post

“It is as if he had summoned together all the most fascinating people you can think of…fascinating-daft-and/or-odd as well as fascinating-wise-or-perceptive, and invited them all to tell us what they think about the mysterious relationships between the past and present. The result is a fantastic treasure house.”

~ Colin Welch, The Spectator

Leave a Reply