Michael Daley writes: In a bombshell article (Observer, 26 September 2021), Dalya Alberge reported on a series of Artificial Intelligence comparisons of the Samson and Delilah’s brushwork with that on 148 uncontested Rubens paintings. The exercise had produced a negative result of such magnitude that the Swiss company, Art Recognition, disbelieved its own findings and ran the tests a second time. The results were identical: an unprecedentedly crushing 91% probability that the picture was not painted by Rubens:

“…Critics have long suggested that the painting is not by Rubens. And now a series of scientific tests employing groundbreaking AI technology have concluded that the 17th-century Flemish master could never have painted it. ‘The results are quite astonishing’, Dr Carina Popavici, the scientist who carried out the study, told the Observer… ‘I was so shocked…Every patch, every single square came out as fake, with more than 90% probability.’”

ArtWatch UK was cited as observing that “coming so soon after its ill-advised espousal of the now-rejected and disappeared $450m Salvator Mundi, these results are a calamity for the National Gallery” [see POSTSCRIPT, below]. A spokesman said: “The gallery always takes note of new research. We await its publication in full so that any evidence can be properly assessed. Until such time it will not be possible to comment further.” That was a far cry from its response in the 21 May 2000 Independent on Sunday: “We have absolutely no doubts about the authenticity of the picture and nor do most experts on Rubens”.

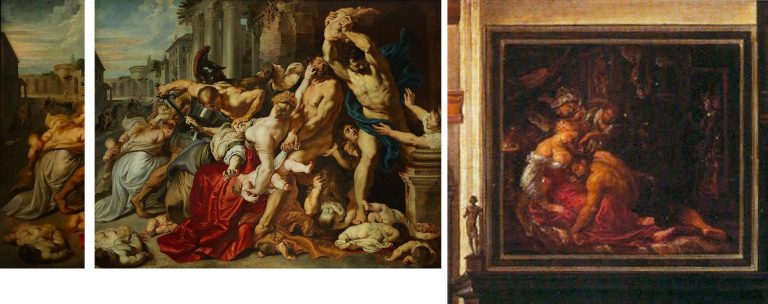

Doubts or not, the Samson and Delilah, which is promoted by the gallery as one its top thirty stars – and therefore as the best of its twenty odd Rubens’ paintings – is now a three-times disabled attribution: it had no provenance as a Rubens before a notoriously unreliable scholar’s 1929 upgrade; stylistically, it has long been shown to be untenable as a Rubens and to be compositionally incompatible with the copies made of the lost original Rubens Samson and Delilah ; and now, on multiple close technical comparisons, its brushwork finds no match with that in secure Rubens’ pictures. How the gallery comes to terms with this latest source of disqualification will test the mettle of its director and trustees, none of whom was party to the picture’s 1980 acquisition.

AN ATTACK ON THE MESSAGE

Alberge’s disclosure has been greeted by a thunderous silence of the Rubens experts – but the art history blogger, auctioneer and film-maker, Bendor Grosvenor, tweeted an immediate blanket dismissal of the findings:

“The only thing this tale should tell us is that computers still don’t understand how artists worked. And probably never will.” And “If you like a bit of science with your art history, it’s still hard to beat the National Gallery’s 1983 technical bulletin for showing the picture is indeed by Rubens.”

Grosvenor’s unsupported assertion bolstered by an appeal to the authority of an old and profoundly unsatisfactory National Gallery report gained tweeted support from the Sunday Times’ art critic, Waldemar Januszczak. In crucial respects the erratic art critical volatility of this pair of commentators (who conduct joint “Waldy and Bendy” podcasts on Januszczak’s ZCZFilms website), exacerbates the National Gallery’s now perilously exposed position. Holding Plesters’ report aloft as a standard may have been thought unhelpful by the gallery – the link Grosvenor provided to it now produces this message: “Page not found – Sorry, the page you requested has been removed or the link was incorrect.”

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the National Gallery’s attributed Rubens Samson and Delilah; second left, the Grosvenor-attributed fragmentary “Raphael” of a Madonna at Haddo House, Scotland; third left, the disappeared and demoted “Leonardo” Salvator Mundi; right, a Colin Wheeler cartoon.

Grosvenor’s appeal to the authority of National Gallery expertise was rich: when, after long examinations, that gallery’s experts recently judged his would-be “Raphael” painted fragment of a Madonna in an all’antica cross-over dress (Figs. 1 and 3) to be no more than a “possible 18th century work” he crossly rejected their findings and called for yet further tests. Where Januszczak now supports the Samson and Delilah’s Rubens attribution he does so in flat repudiation of his 1997 younger self’s rumbustious denouncement of it (Fig. 2). With their joint appeal to the authority of the National Gallery conservation staff’s record, Grosvenor and Januszczak have opened the door to the gallery’s skeleton cupboard.

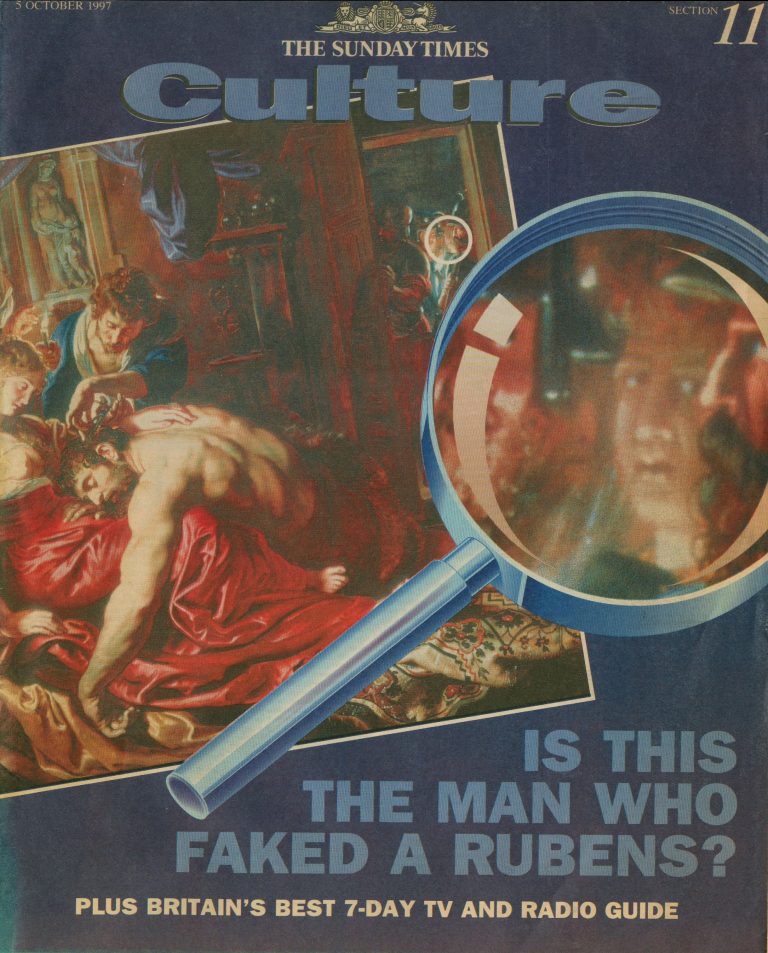

Above, Fig. 2: The cover of the 5 October 1997 Sunday Times Culture Magazine which trailed Waldemar Januszczak’s article “A Rubens or a costly copy”

Above, Fig. 3: Top, BBC4 Factual Report, 03. 10, 2016: “Britain’s Lost Masterpieces discovers hidden painting believed to be by Raphael. ‘Finding a potential Raphael is about as exciting as it gets. At first I couldn’t quite believe it might be possible, but gradually the evidence began to all point in the right direction.’ Dr Bendor Grosvenor”. So reported the art-credulous BBC with a photograph (top) of the programme’s co-presenters, art historian Jacky Klein and Bendor Grosvenor, with the putative Haddo House Raphael; above, the presenters consider the “Raphael” on the Lost Masterpieces programme with the former director of the National Gallery, Sir Nicholas Penny.

Invited to pass judgement on the attempted upgrade, Sir Nicholas (whose proselytising on behalf of the $450m Salvator Mundi had been defended by Grosvenor in the 9 October 2011 Sunday Times – “They are taking a risk and I can’t applaud them enough for it”) said that he would place the painting somewhere between “probably by Raphael” and “by Raphael” and that with a “little more time and courage” he might well go the whole hog. That stylishly diplomatic locution was of limited utility – rather like informing a woman that she is somewhere between probably pregnant and pregnant. The pity is that aside from his defences of National Gallery restorations and championing of a not-Raphael and a not-Leonardo, Penny proved the gallery’s most unapologetically serious scholar/director in recent times – as instanced in an excellent Financial Times interview.

ROLL UP

In another Financial Times interview, Simon Gillespie, the restorer who works with Grosvenor on the BBC’s Britain’s Lost Masterpieces programme, disclosed that he, too, believes that he might own yet another Raphael. Gillespie is believed to be the owner of a claimed Lely copy of the £10m “Last Van Dyck Self-portrait” that was sold by the Mould Gallery to the National Portrait Gallery for £10m on 1 May 2014.

DEFENDING INSTITUTIONS AND ATTACKING JOURNALISTIC MESSENGERS

Grosvenor frequently tilts at journalists whose stories embarrass art institutions. In a February 2019 Art History News blog post (“Salvator Mundi & the Louvre”) he berated Sunday Telegraph and Mailonline reports that the Louvre would not be showing the $450m supposed-Leonardo Salvator Mundi in a forthcoming Leonardo exhibition. That story, he sniffed, “is based on the opinion of one Jacques Franck.” It was. Franck’s judgements as the world authority on Leonardo’s painting technique have institutional clout (- and often the ear of French presidents). Franck’s prediction proved precisely correct: the Salvator Mundi was not included in the Louvre exhibition, and it was described in the exhibition catalogue as what it is and what it has remained despite successive restoration makeovers and intense global marketing razzamatazz (- which marketing Grosvenor lauded as the best ever seen) namely, the Leonardo studio work that entered the Cook Collection in 1900, viz: “Salvator Mundi, version Cook, vers 1505-1515″. (See “The Louvre Museum’s bizarre charge of “fake information” on the $450 million Salvator Mundi”.) The Art Newspaper has reported (November 2021, “Prado downgrades $450m Leonardo Salvator Mundi”) that the Prado, too, has demoted the Salvator Mundi to its original standing as the Cook version: “The Prado curator Ana Gonzáles Mozo comments in her catalogue essay that ‘some specialists consider that there was a lost prototype [of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi] while others think that the much debated Cook version is the original’ However, she suggests ‘there is no painted prototype by Leonardo’.”

(For the latest observations on the $450m Salvator Mundi, see Jacques Franck’s “Further thoughts about the ex-Cook Collection” and ArtWatch UK’s “The Disappeared Salvator Mundi’s endgame: Part I – Altered States and a Disappeared Book”. For ArtWatch UK’s first objections to the Salvator Mundi upgrade, ahead of Christie’s November 2017 $450m sale, see: Dalya Alberge, 19 October 2017: “Mystery over Christ’s orb in $100m Leonardo da Vinci painting” and, “Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”.)

THE RAMIFICATIONS

The Rubens and the Leonardo attributions are items of considerable public policy interest. Both works achieved world record prices. Both received major and controversial modifications at the hands of restorers. Both upgrades have now collapsed. Both had been championed by National Gallery directors – Michael Levey with the Samson and Delilah and Nicholas Penny with the Salvator Mundi. While Waldy and Bendy both now support the Samson and Delilah, Waldy rejected the Salvator Mundi (which Bendy supports) because: “It resembles nothing else Leonardo painted”; and, because Christie’s claimed resemblance of it to the Mona Lisa “had me laughing out loud”.

THE NATIONAL GALLEY’S WOBBLY DEFENCES

The Art Recognition findings are not, as Grosvenor would imply, off-the-wall. In June 1997 the National Gallery issued a notice claiming that the reason why the Samson and Delilah looked like no other Rubens in the gallery was because it had been painted at a special and very brief moment when Rubens had just returned from Italy and was keen to show off newly acquired Caravaggist traits. That apologia was not credible.

In a pioneering 1992 report, the scholar/painter Euphrosyne Doxiadis and the painters Stephen Harvey and Siân Hopkinson, conducted a focussed survey of six Rubens paintings of 1609 and 1610 and demonstrated that “All these display a consistency and quality of style which is not shared by the Samson and Delilah”. That report – “Delilah cut off Samson’s hair, but who cut off his toes? The case against the National Gallery’s ‘Rubens’ Samson and Delilah” – was placed in the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah dossiers and is published on the dedicated In Rubens Name website.

THE ART RECOGNITION REPORT

We are very pleased to publish here the full Art Recognition report on the Samson and Delilah, as below, and would urge all to study it along with the pioneering, methodologically exemplary Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson report.

REPORT_Samson_Delilah_Rubens_encr

With no match to be found for the picture among a score of National Gallery Rubens paintings or among six bona fide Rubens’ works of the precise (claimed) historical moment, why should it come as an affronting surprise that none was found by Art Recognition among 148 secure paintings? Just as Grosvenor demanded more tests on his wannabe Raphael, so he would seem to want the Samson and Delilah compared with every single picture in the oeuvre. On September 30th he complained: “To claim a judgement on the Samson & Delilah based only on scans of 400 [sic] works (and at what resolution? We are not told) out of an oeuvre of over 1000 works seems to me optimistic.” Rather than pressing for every work in the oeuvre to be tested, he might prefer to cite and photographically demonstrate a single other painting with brushstrokes that, to his eye, match those of the Samson and Delilah.

The National Gallery has long been unable to cite a single report or record that shows the Samson and Delilah to have been planed-down and mounted on blockboard before it was bought for a world record Rubens price in 1980. In place of evidence, the gallery, too, falls back on appeals to authority, claiming, for example, in a 23 May 2000 press statement, that “…a large number of distinguished scholars who have devoted their careers to the study of Rubens unanimously agreed that the painting was one of the artist’s masterpieces”.

Such appeals cut little ice: every restoration or attribution ArtWatch has challenged in the last thirty years had been supported by a bevy of art historical bigwigs – from the Sistine Chapel ceiling to the recent so-called Leonardo “Male Mona Lisa” (Fig. 1 above). Moreover, of all scholarship, that on Rubens remains the most problematic and herd-like, its key players being uniquely obligated by a family bequest to defer to the scholarship and judgements of the long deceased (and now discredited) scholar Ludwig Burchard.

ARTISTS KNOW

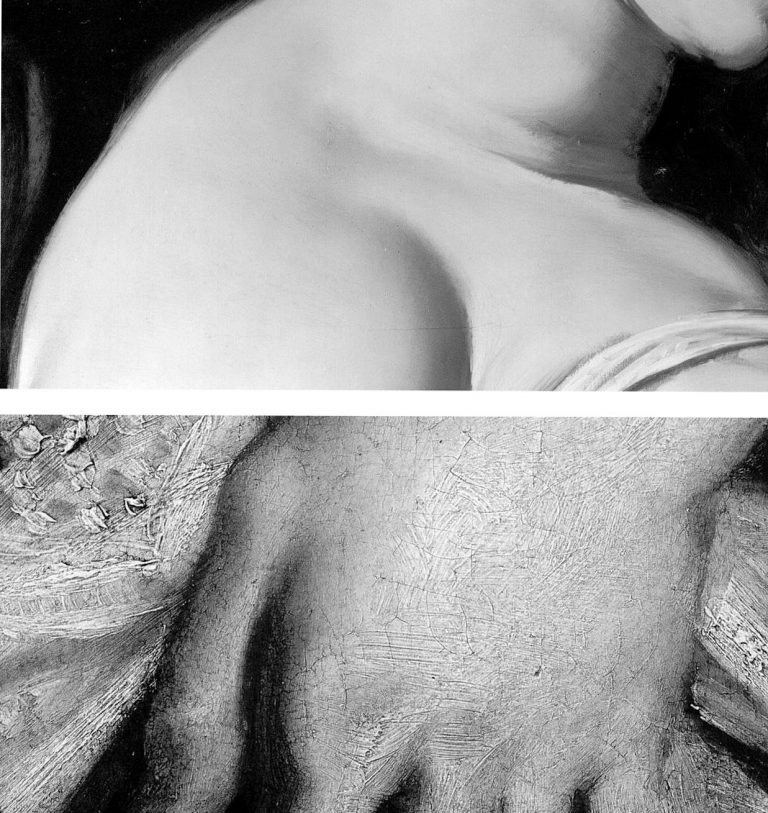

The challenge to that art historical authority has come principally from artist/scholars who are freer agents and arrive armed with hands-on knowledge of art’s practices – knowing, for example, how to put brush to paint and paint to surface. A quarter of a century ago Euphrosyne Doxiadis neatly encapsulated the now technically confirmed deficiencies of the picture’s brushwork in an interview:

“This picture is betrayed by brush strokes which are almost staccato and broken up, rather than having been done with one stroke of the wrist, which you see in all Rubenses. There is an absence of Rubens’ vibrant, pulsating-with-life strokes. In actual Rubenses, each stroke is a tour-de-force. This is clumsy and awkward.” (Dalya Alberge, “Expert denounces National Gallery’s Rubens”, The Times, 25 November 1996.)

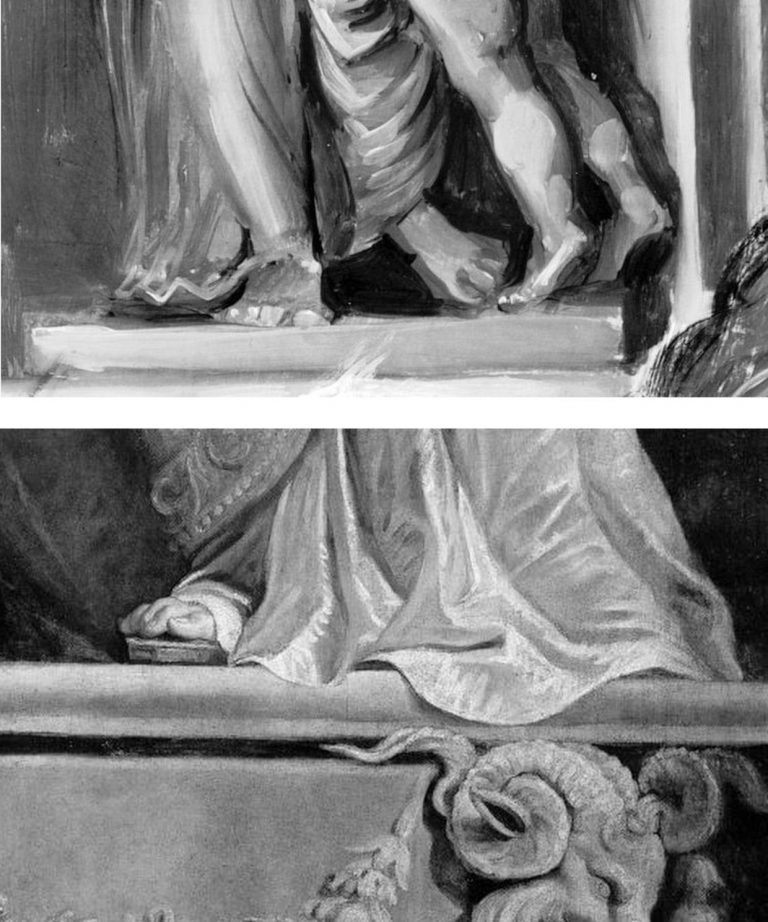

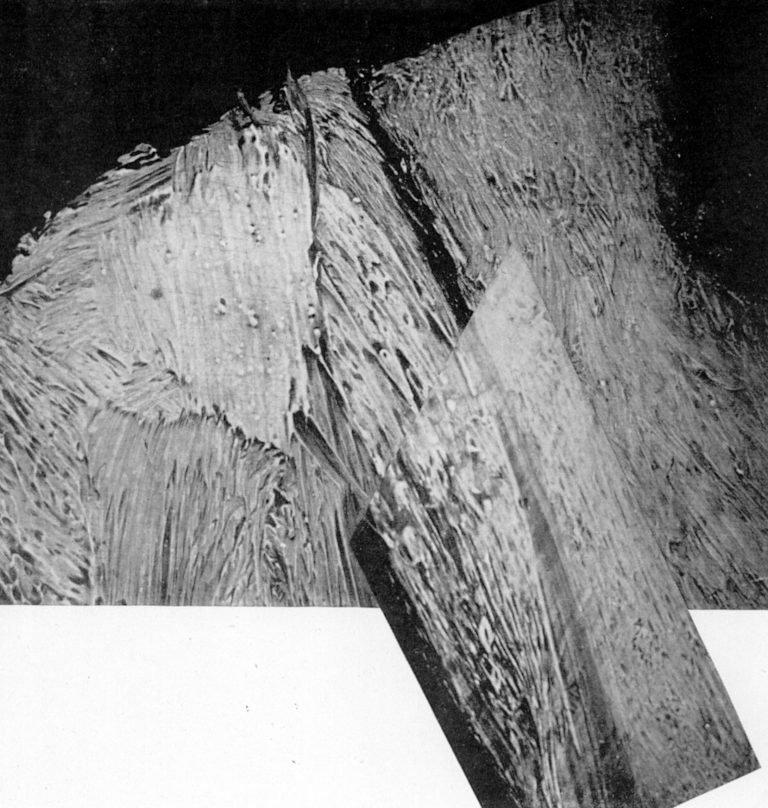

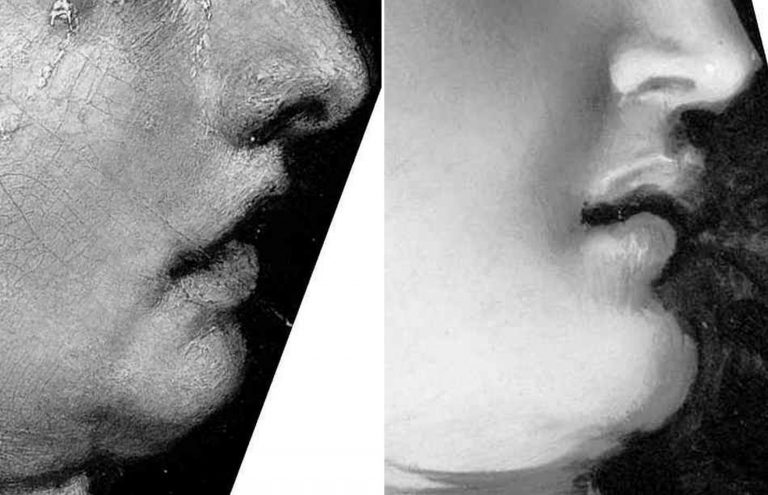

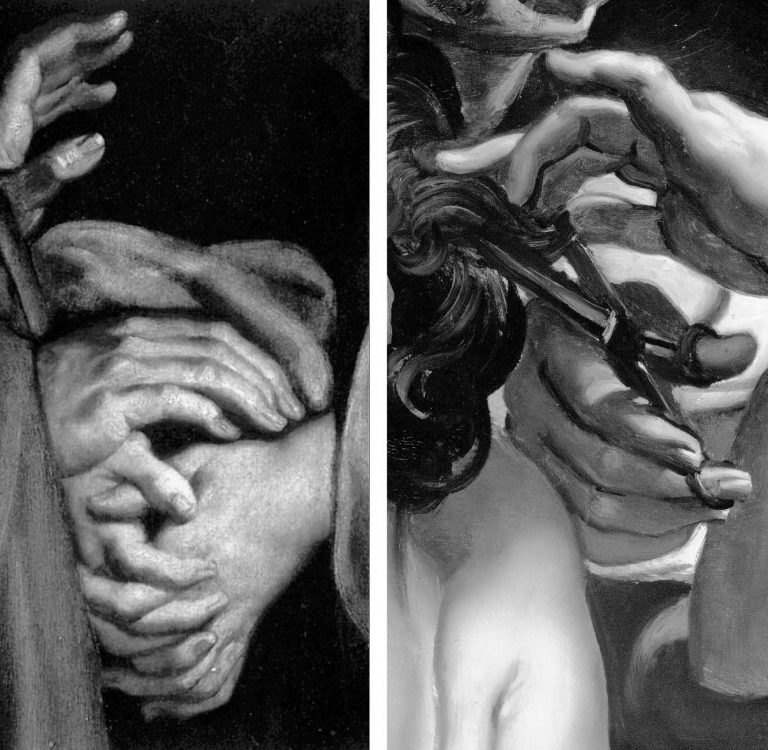

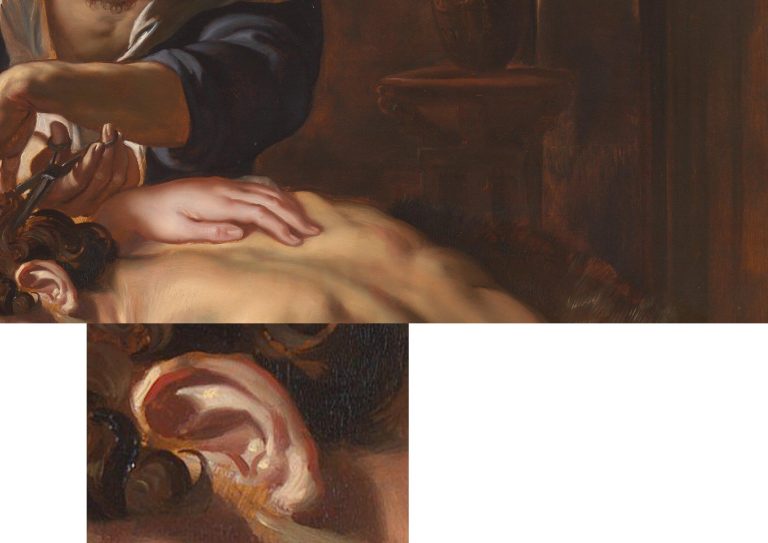

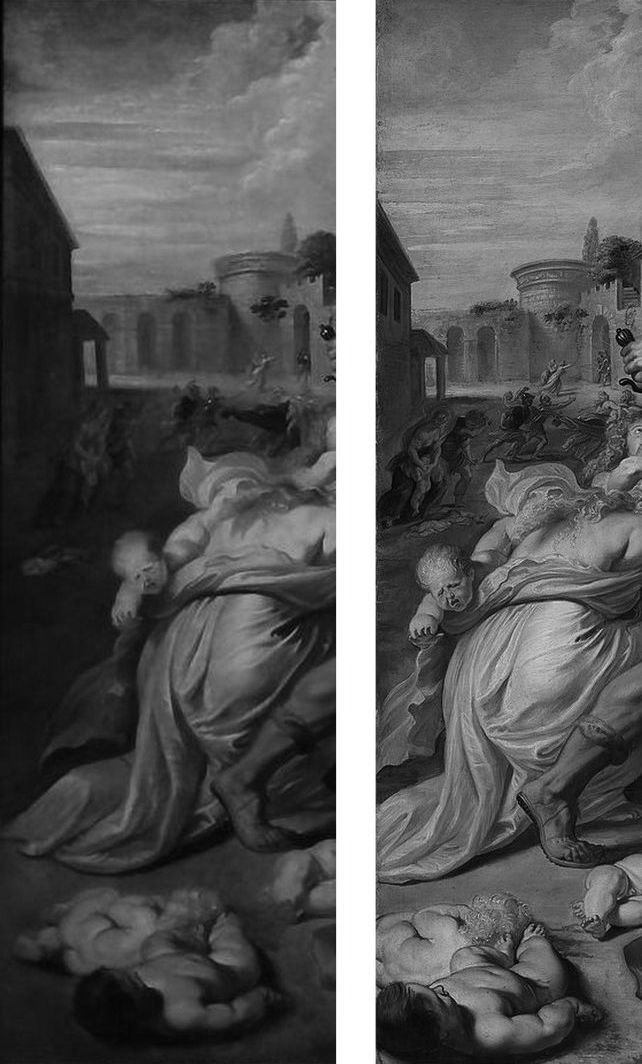

Above, Fig. 4: Top, details of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah; above, Rubens’ The Raising of the Cross, Antwerp Cathedral. Where the former is claimed to be a lost picture Rubens painted in 1609-10, the latter was indisputably made by Rubens between 1610-11. Such pronounced differences in brushwork are inconceivable as that of two autograph paintings made at the same moment in Rubens’ oeuvre. Who, looking at this photo-comparison, could believe that Rubens had flitted between the ugly angular Cubist faceted feet in the Samson and Delilah statue (– try counting the toes and note the Art Deco zigzagging hem), and the superb fluency, grace and anatomical fidelity seen in the Raising of the Cross?

THE TESTIMONY OF NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETINS

When Tweeting support for Grosvenor, Waldemar Januszczak, had seemingly forgotten his own 5 October 1997 Sunday Times article headed: “One of the World’s most valuable paintings hangs in the National Gallery. But Samson and Delilah, widely assumed to be by Rubens, is not by him but is a copy, argues Waldemar Januszczak. Who then did paint it?” Januszczak had ended with this ringing declaration: “The one thing we doubters all agree on is that the painting bought by the gallery for a staggering sum in 1980 is not by Rubens.” What has changed to un-doubt Januszczak? Under challenge on Twitter, Grosvenor admitted that he too had once entertained doubts about the Rubens ascription.

Joyce Plesters’ 1983 Technical Bulletin account was tendentious and error prone. She had counted six planks in the Samson and Delilah panel when the picture’s restorer, David Bomford, made it five and the gallery’s panel specialist, Anthony Reeve, counted seven – as would a dendrochronologist in 1996. Plesters thought the National Gallery’s attributed Michelangelo Entombment of Christ had been painted on a single giant plank when the panel is comprised of three butterfly-keyed planks. The senior curator, Christopher Brown, accepted Plesters’ six planks in the catalogue to the National Gallery’s 1983 “Acquisition in Focus” celebratory exhibition of the restored Samson and Delilah. In 1997 Januszczak poked fun at the conservation department’s shambolic technical reporting:

“I am shown these authoritative-looking documents and, on the first page, the information that the Samson is painted on five planks has been crossed out and changed to seven planks. In the published technical report we are told there are six planks. A conservation report that cannot count the number of bits of wood the gallery’s most expensive painting was done on hardly inspires confidence.”

One of the painting dossiers that I later I examined at the National Gallery (under the directorships of Charles Saumarez Smith and Nicholas Penny) disclosed that a large and important picture had been mounted on “Sundeala” boards with a honeycomb paper core. The disclosure had not been made in the report itself but had been written on an attached yellow post-it note. Plesters’ haplessness was more than arithmetical. The year before Januszczak’s tease she had suffered a mortifying professional reverse. In the 1960s, when scholars like Ernst Gombrich and Otto Kurz warned Gallery restorers against removing all-over tinted varnishes from Renaissance paintings, she insisted that the entire documented technical history of art showed “no convincing case” for any artist having emulated Apelles’ legendary dark varnishes and that the famous passage from Pliny was of “academic rather than practical importance”. She even offered to “sift” and “throw light upon” on any future historical material that Professor Gombrich might uncover.

A BURIED INCONVENIENT TRUTH

In 1977, in the National Gallery’s first Technical Bulletin, Joyce Plesters had mused complacently “one or two readers may recall the furore when the cleaning of discoloured varnishes from paintings…began to find critics.” In that year the scarcely less complacent former National Gallery director Kenneth (Lord) Clark pronounced picture cleaning “a battle won”. A third of a century after the original controversy, the practical import of Pliny’s testimony emerged in a 1996 Technical Bulletin disclosure that a Leonardo assistant, Giampietrino, had toned down his colours with a final dark “varnish” layer of oil with black and warm earth pigments.

Had those pigments been bound in a resin it would have been deemed an earlier restorer’s attempt to impart a spurious “old masters’ glow” and removed. However, Giampietrino’s dark overall toning was identical to the oil medium of the painting itself and any solvent that would dissolve the one would dissolve the other. The gallery had to leave the coating in place. Shamefully, it stifled any acknowledgement of its momentous art historical significance – and it even neglected to inform Gombrich of the corroboration of his earlier claims, despite the fact that the gallery’s then director, Neil MacGregor, held the 1960s dispute to have been “one of the most celebrated jousts” in modern art history.

When ArtWatch UK informed Gombrich of his vindication he was approaching his 87th birthday and responded: “I could hardly have a nicer present than the information you sent me. I don’t see the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin and would have missed their final conversion to an obvious truth. There is more joy in heaven (or Briardale Gardens…)” Two years later he observed: “I believe it was Francis Bacon who said that ‘knowledge is power’. I had to learn the hard way that power can also masquerade as knowledge, and since there are very few people able to judge these issues, they very easily get away with it.” (See “How the National Gallery belatedly vindicated the restoration criticisms of Sir Ernst Gombrich”.)

THE MISSING BACK, A LEGAL CHALLENGE, AND OTHER SAMSON AND DELILAH PROBLEMS

Above, Fig. 5: Two special issues of the ArtWatch UK Journal that examined the Samson and Deliah’s credentials as a Rubens.

In Journal No. 21, Kasia Pisarek wrote:

“I am in possession of a privately printed pamphlet entitled The Biggest Scandal since the Fake Vermeer written in 1960 by a well-known French art dealer Jean Neger. In it, he openly denounced Dr. Ludwig Burchard as being a dishonest man writing a certificate of authenticity for a painting that he knew was a copy. The picture in question was Diana departing for the Hunt, a large oil on canvas, sold in 1960 as a Rubens for a huge amount of money to the Cleveland Museum in America. It first appeared in an Amsterdam sale (Valkenier family) in 1796, in fact as late as 180 years after its supposed creation c.1615. Neger accused Burchard of ‘defrauding the American state of 550.000 dollars’.

“In his highly dramatic pamphlet he declared that Dr. Burchard wrote the certificate of authenticity in 1958, even though he knew that another, nearly identical version (his own) of the painting existed, and had a considerably better provenance, going back to 1655 and the prestigious Spanish collection of the marquis de Leganes, a friend of Rubens. This was the most important collection in Spain, aside from that of the King Philip IV. Leganes probably owned more paintings attributed to Rubens than any other aristocratic collector in Spain, with the possible exception of Gaspar de Haro. After researching his painting, Neger discovered that the number 214 in white paint present on his canvas was the corresponding Leganes inventory number. Moreover, his version of Diana had a lot of pentimenti visible even to the naked eye, which would indicate that it was an original, not a copy.

“According to Neger, Burchard has tried to avoid him on many occasions and has refused to see or to certify his version because he had already certified the other one as the original. When approached, he tried to ‘compromise’ by saying that he would state that Neger’s version was the first one, which Rubens had sketched and abandoned, and that he had then painted a second version, the one from Cleveland. Later, he took up Neger’s picture again, corrected it and completed it. That solution was satisfactory to Neger and yet, Dr. Burchard changed his mind again, and refused to certify Neger’s painting at all. Subsequently, he chose not to reply to Neger’s allegations which appeared to be his usual attitude in such situations.”

Dr. Pisarek concluded:

“I verified most of Neger’s statements, which on the whole appear to be true. I traced both pictures: one is in the Cleveland Museum, effectively considered to be the original by Rubens; the other is in The Getty Museum in Malibu, as ‘a workshop copy’. And yet, the Getty picture (ex-Neger’s) has better chances of being the original: it is the larger of the two versions; it has a superior and older provenance (1655 as compared to 1796); it agrees in most details (presence of sandals, lack of birds in the sky, missing tiger’s skin, background landscape) with an old copy in Cassel which provenance (1756) predates that of the alleged Cleveland’s ‘original’.”

Pisarek discussed the merits of these two pictures in the third chapter – “The two versions of Rubens’s Diana Departing for the Hunt: an American cause célèbre” – of her doctoral thesis, Rubens and Connoisseurship. On the problems of attribution and rediscovery in British and American collections, University of Warsaw, 2009, and there concluded that both the Cleveland and Getty pictures are mostly products of Rubens’s workshop.

DEFENDING MUSEUM FAKES I

On 4 March 1929, the year that Ludwig Burchard found and upgraded the Honthorst painting then owned by van Diemen and Benedict (who had bought it, Doxiadis disclosed, from a painter/restorer) and that is today the National Gallery Samson and Delilah, Rene Gimpel, author of the 1996 Diary of an art dealer, wrote:

“The Italians have sold Americans $2m worth of marbles done by Dossena (a faker). A laughable sum compared with the amounts obtained by means of certificates given daily by German experts to German dealers. Just as there were paper marks, so there are paper canvases, an easy way of bringing dollars into Germany. I went this morning to the Van Diemen gallery, which has an exhibition of sixteen Venetians. Three pictures are good, apart from the Guardis and perhaps the Longhi. Last Sunday’s Times devoted an entire page reproducing this scandalous exhibition, which gives only a faint idea of what is brought in. Bode, the director of the Berlin Museum died two or three days ago. The king is dead long live the king! The Mayers, the Gronau will replace him. The German title of Doktor impresses the Americans. The museums are even more intent than the collectors on defending their fakes or their mistaken attributions.”

WHAT LIES BEHIND

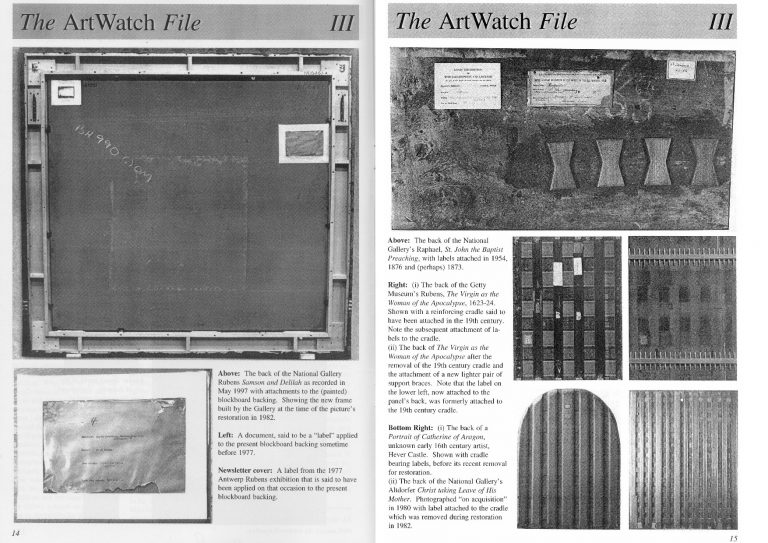

Above, Fig. 6: A spread of pages from ArtWatch UK Journal No. 11 contrasting the Samson and Delilah’s present back with the labelled and cradled backs of comparable period panel paintings.

Above, Fig. 7: Illustrations of the back of the Samson Delilah picture as supplied by the National Gallery and as published in the June 2000 Art Review (“The Back is Where It’s At”) where we showed the back of the Samson and Delilah and its attachments, as recorded in 1997. Our detailed technical and art historical case against the Rubens attribution in the Art Review ran, in full, as follows:

“Last month I referred to a National Gallery picture which lacks a back or a record of a back but on the back of which an incomplete provenance depends. This bizarre, paradoxical case arose as follows.

“On 11 July 1980, the National Gallery paid £2.53m (through Agnew’s at a Christie’s auction) for a large picture, Samson and Delilah, that was said to be an ‘entirely autograph’ Rubens, probably in its original frame. The price was a world record for the artist and, at the time, the second highest for any painting bought at auction. The acquisition was presented to the world with great fanfare, orchestrated as much by the gallery as by the auctioneers. In 1982 the picture was cleaned, restored and reframed in preparation for a special ‘Acquisition in Focus’ exhibition to be held the following year. So far, so straightforward.

“In 1983, two accounts of the restoration were published in the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin by David Bomford, restorer, and Joyce Plesters, head of science. At this point the painting, which hitherto had always been described as a panel, begins to be described in different terms. Namely, as a planed-down sliver of a panel mounted on a modern laminate sheet of blockboard. As Bomford put it, ‘the large panel on which Samson and Delilah is painted must originally have been substantially thicker than it is now. At some point, probably during the present century, the panel was planed down to a thickness of less than 3 mm and subsequently glued on to a sheet of blockboard.’ This seems in strict, factual terms to be correct, but the word ‘probably’ later came to be questionable.

“Plesters’ account was seriously misleading. She claimed that the planed-down panel had been set not onto but ‘into’ (which it had not) the sheet of blockboard, which supposed placement prevented its edges from being examined for tree-ring dating purposes – which it did not. She insisted that this phantom relationship was of no consequence because ‘the date and provenance of the painting are not in doubt.’ Which claim, as will be shown, was not the case. Plesters admitted that the planing, on an unidentified occasion ‘before the picture was acquired by the Gallery’, might well have destroyed, among other evidence, a branded or carved panel-maker’s mark – a far from trivial matter because such a mark might have sunk the attribution to Rubens. The original Samson and Delilah is dated 1609, sometimes 1610; its engraved and painted copies to c. 1613 and 1615 [sic – 1625-35] respectively. Very few panel-makers marks were made before 1617 when they first became a guild requirement; after this date they can help with datings. Michiel Vrient, whose mark is most commonly found on the back of Rubens’ later panels, only qualified in 1615. His mark on the Samson and Delilah would have been fatal.

“Clearly, establishing when, by whom, and for what purpose a planing was carried out – and what records were kept of the original back – would under any circumstance be a matter of urgency and a test of propriety. In this instance it became greatly more so when, in 1997, a number of eye witnesses reported to ArtWatch UK that the picture had retained its original, label-bearing and ‘cradled’ back immediately prior to and during its auction at Christie’s in 1980. When informed of this, Neil MacGregor, the gallery’s director, dismissed the testimony as ‘mistaken’ (letter 7 April 1997). He later said (9 April) ‘the National Gallery does not have any record, photographic or written, of the back of this picture before it was planed down.’

“This year [2000], in compliance with its ‘Code of Openness’, adopted in anticipation of Government legislation on freedom of information, the gallery reversed an eight-year-old decision and allowed me to examine the dossiers held on the picture and its treatments. I have been assured that the dossiers were complete and that no material was withheld. I am forced to report that the records are therefore lamentably incomplete. This is the more disturbing because, contrary to assurances, the picture’s provenance is extremely insecure. It is not to the gallery’s credit that it took six years of assiduous research by three painters – Euphrosyne Doxiadis, Stephen Harvey and Siân Hopkinson – between 1986 and 1992 – for this embarrassing reality to be brought to light. They demonstrated that the picture is not compositionally consistent with contemporaneous engraved and painted copies of the original picture. Their examination drew from Christopher Brown, the curator responsible for the acquisition, the admission that ‘there are gaps at the beginning and the end of the Liechtenstein provenance which makes it impossible to be 100 per cent certain that this is the picture painted for Rockox.’

“The provenance as presented by Christie’s in their sale catalogue was a daisy-chain of speculations pegged on disconnected and not always accurate citations. It was claimed in the first instance that the picture was ‘probably’ the one known to have been painted in 1609-10 for Nicolaas Rockox’s house. It was said to have ‘perhaps’ been in the possession of the painter Jeremias Wildens (albeit only as a ‘Samson’ and not as Samson and Delilah) before 1653. It was further said to have ‘perhaps’ been in the possession of a ‘Guill Potteau’ before 1692. It was then said to have passed into the hands of the Prince of Liechtenstein on 30 May 1700. The second, third and fourth suggestions are all dependent on an event having taken place for which there is no evidence whatsoever: that the original painting left Rockox’s house at his death in 1640.

“As Euphrosyne Doxiadis established (and as Dalya Alberge reported in The Times of 25 November 1996), the records show that Rockox’s collection remained in his house until its sale in 1714 after the death of Rockox’s last descendant in 1712. The house in Antwerp survives and was restored in 1977 as a museum to Rockox. A booklet produced that year by the museum acknowledged with regret that it had been impossible to reassemble the whole of the original collection which had been dispersed by a public auction in 1715. Knowledge of this sequence of events seems rapidly to have slipped from official art historical consciousness

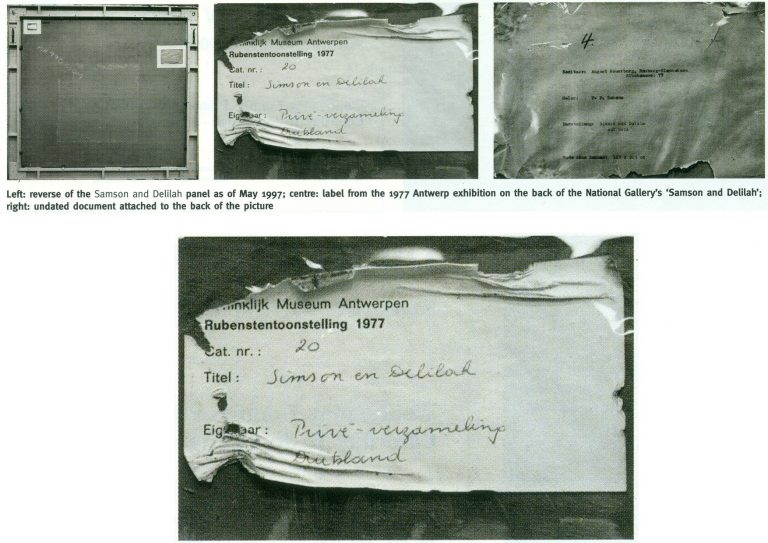

“By coincidence, the National Gallery’s picture (then in a private German collection) was exhibited in Antwerp in 1977 in a large exhibition celebrating the 400th anniversary of Rubens’ birth. In the catalogue Frans Baudoin described it as a ‘panel’. In the same year, in his book Nicolaas Rockox: ‘Friend and Patron’ of Peter Paul Rubens, Baudoin said the panel was ‘excellently preserved’. He also reported that the picture had been ‘rediscovered’ (when owned by a dealer as a Gerit van Honthorst) in 1929 by Ludwig Burchard, on whose advice, the German magnate August Neuerburg bought it in 1930 (along with another Burchard ‘Rubens’, since de-attributed).

“Burchard’s ‘rediscovery’ closed the second gap in the provenance to which Christopher Brown referred. Samson and Delilah is said to have disappeared after being sold by the Liechtenstein collection in 1880. In addition to the ‘gaps’ of 60 and 50 years at either end of the Liechtenstein provenance there are two further problems. First, the Samson and Delilah was described in every Liechtenstein inventory as a copy. Even the dealers who sold it to the collection thought it not to be by Rubens and to be greatly inferior to a work by Van Dyck. Second, every painting in the Liechtenstein collection was marked with a seal on its front or back. The National Gallery’s picture has no seal on the front. If it had one on its back, what happened to it? What possible reason could there be for removing and destroying such an important feature of a picture’s pedigree?

“When pressed on such specifics, the National Gallery summons the fogs of time. Bomford thought the planing might have taken place in the 19th century. His director, MacGregor, suggested that it was ‘possibly done this century, perhaps when the painting was in the hands of the art trade in the 1920s’ (Letter 9 April 1997.) This really will not do. The dossiers contain, I discovered, an undated sheet of typescript by Burchard (which the gallery’s archivist tells me is part of a letter dated 8 April 1930, but which contains a handwritten postscript referring to an article of 1942) which not only describes the picture as being ‘in a remarkably good state of preservation’ but, crucially, testifies that ‘even the back of the panel is still in its original condition.’ Given Burchard’s testimony, and bearing in mind that Christopher Brown made a special study of Burchard’s manuscript notes on the painting (which we have not been allowed to see) prior to the 1983 ‘Acquisition in Focus’ exhibition, how could the gallery have believed that the planing might have taken place before the last [the 20th] century or when the picture was in French hands?

“These questions are the more perplexing because, after Burchard’s testimony, every single reference to the picture describes it as a ‘panel’ in good – or better – condition. A further document in the [National Gallery] dossier that throws light on the picture’s condition also seems to have been overlooked. Christopher Norris, a benefactor of the gallery, sent a letter of congratulations to Michael Levey, the director, the day after the sale at Christie’s. Norris attributed the picture’s still ‘amazing condition’ to the fact that the German owners [between 1930 and 1980] had not touched it. It still retained, he noted, the varnish applied during its stay in France in 1929. The only change that had occurred during Norris’s forty-seven years’ acquaintance with the picture was that the varnish had toned down. (In 1983 Bomford cited the picture’s ‘thick, considerably yellowed varnish’ as the ‘principal reason’ for cleaning.)

“In 1977, Gregory Martin, the author of Christie’s catalogue entry, reviewed the Antwerp Rubens exhibition. He observed with relief that the Samson and Delilah was one of two ‘great works…on panel’ that were ‘none the worse for their journeys’ to Antwerp. (In 1982, the picture was described in the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin as one of only three well-made and untroublesome panels in the collection.) Three years later the picture again left Germany when it was sent, on offer of sale, to a Belgian museum. On its arrival, a condition report (dated 4 March 1980) was prepared by a leading Rubens expert. He described the picture as a ‘panel…in good shape’ with painting in a condition ‘which can be called excellent’. The panel remained for several months at the museum before being dispatched directly to Christie’s. During its stay at the museum, the picture was seen to be an old, thick, somewhat bowed, label-bearing and cross-battened panel. Brian Sewell (who had discovered the Samson and Delilah modello some years earlier at Christie’s) recalls that the picture, when at Christie’s, was an intact, cross-battened panel with a blackish painted back on which the Christie’s number [as given to every work on arrival] was stencilled in white paint.

“On 27 May 1997, Neil MacGregor sent me photographs of the picture’s back ‘as it is now’. He drew attention to the Christie’s number (chalked and stencilled in black paint) and to ‘two labels attached to the back of the blockboard’ (see illustrations). One, he said, is from the Antwerp exhibition of 1977, the other ‘rather older, from the Neuerburg Collection’. It was, he said, ‘hard to imagine any of these being put on after the picture left Christie’s.’ It is not. Neither document – only one of which appears to be a label – would seem to be glued or pasted to the blockboard. Both appear to be held in place, identically, with cellophane fixed by clean masking tape. Both documents are clearly proud of the surface and are seen to cast shadows on it. The 1977 Antwerp label shows clear signs of having been attacked with a scraper. Why? When? And by whom? After receiving these photographs, I asked to see the back on an occasion when the picture had been removed from its frame. So far, I have not been permitted to do so, and two requests to government ministers for an inquiry have been turned down.”

THE DIFFERENCE A MISPLACED HISTORICAL WORD CAN MAKE IN AN AUCTION CATALOGUE

Today, given the Samson and Delilah’s recent further disqualification on a technical analysis of its brushwork, the National Gallery’s continuing claim of a Rubens authorship runs increased risks.

First: That espousal continues to fly in the face of historical documentary evidence that the picture cannot safely be ascribed to Rubens – evidence that had emerged and was published twenty-five years ago by Dalya Alberge (“Artists raise fresh doubts on gallery’s Rubens masterpiece” 26 September 1996, the Times”):

“ARTISTS challenging the attribution of Rubens’s Samson and Delilah in the National Gallery believe that evidence presented in an auction house’s catalogue was mistaken. The artists also allege that the gallery refuses to acknowledge historical facts that cast doubt on the picture being by the 17th-century master. The National Gallery acquired the painting from Christie’s in 1980 for £2.5 million, equivalent to £6 million today. The auction catalogue referred to a 1653 inventory which described the painting as ‘Eenen Samson van Rubens’, which would mean ‘by Mr Rubens’. But a Flemish genealogist who has studied the inventory said that it read ‘Eenen Samson naer Rubens’: ‘naer’ is translated as ‘made just like Rubens’ or ‘after Mr Rubens’. Another inventory, dated 1692, lists it as ‘copye’ – a copy.

“Euphrosyne Doxiadis, an artist and scholar, and the painters Steven Harvey and Siân Hopkinson believe that the genealogist’s finding backs the stylistic evidence against the picture being by Rubens… It was only as recently as 1929 that the painting was hailed as a long-lost Rubens. For 180 years it was in the collection of the Princes of Liechtenstein and inventories in 1767, 1780 and 1873 attributed it to a minor hand, Jan Van Den Hoecke…”

THE SHIFTING TESTIMONY OF LUDWIG BURCHARD

Second: With this picture never having been thought an autograph Rubens before Burchard’s 1929 upgrade, everything rests on that scholar’s tarnished standing. Aside from the Neger scandal, Pisarek noted in the Spring 2006 ArtWatch UK Journal (No. 21, “The ‘Samson and Delilah’ – a question of attribution”) that over 60 pictures, albeit mainly small works, attributed by Burchard to Rubens had been down-graded in Corpus Rubenianum to studio works, copies or imitations. In a 1950 letter to a fellow art historian, Burchard had said of a painting now in the North Carolina Museum of Art: “The Rubens-like painting was once shown to me. I missed the transparency of the shadows, which one would expect at least in places. The picture seemed to me like a compilation by a contemporary of Rubens.” However, in 1954 he had said of the same painting in a certificate of 28 May addressed to the D. M. Koetser Gallery, London: “the vigour of the design, the brilliance of the vivid colours, the concentration of movement are comparable in several details to the painter’s Defeat of Sennacherib c. 1612…”

THE FIXED TESTIMONY OF PAINTWORK

Third: As mentioned, the 1992 Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson Report had anticipated and thereby now effectively corroborates the Art Recognition findings in its section on Rubens’ painterly technique:

“We have now studied the technical deficiencies in the execution of the National Gallery Painting; we have collected a very comprehensive catalogue of faults which are demonstrated by comparison with works of that period. This can be done when visual material is included…

“It is totally out of character for Rubens to use what the National Gallery calls ‘bold’ handling over the entire surface of a painting. In all his other works, areas of beautiful and infinitely detailed work appear, in addition to areas which have been handled boldly – a woman’s jewellery, for instance, the lace on a ruff, or a flower in the foreground. On the whole, the great downfall of the National Gallery’s picture is the crudeness with which it has been painted. Quite apart from the unsubtle transitions from tone to tone and from colour to colour (look for example on the Venus statue in the background [here, Fig. 4, above], or at Samson’s ear [Fig. 24, below], compared with his own ear in the self portrait of Rubens and Isabella Brant in the Honeysuckle Bower painted in the same year) there are two enormous drips of paint on the surface of the work, which no painter with even the most basic training would have allowed himself to do at that period….

“Looking closely at Samson and Delilah one misses the vibrant, twisting nature of the brushstrokes themselves. The shapeless, unanimated strokes in this painting seem flat and unexciting when compared with Rubens’ usual virtuosity.”

SO, ONCE AGAIN, WHO PLANED THE BACK OFF THE SAMSON AND DELILAH PANEL?

Fourth: The Samson and Delilah picture retains an abiding technical mystery: at what date and by whom was the panel planed down and attached to a modern laminate sheet of blockboard?

It should always be appreciated that no reference had ever been made to a planing and a blockboard backing before the Plesters/Bomford accounts of 1983, and that the National Gallery’s accounts are inconsistent, shifting and full of holes. As seen, some have said the planing may have occurred in the 19th century or early 20th century, others that it took place between 1930 and 1980. The gallery claims to have kept no records of the picture’s state in 1980 when purchased and, even, to have prepared no reports for its trustees when seeking authorisation to make a then massive purchase that would consume most of the gallery’s annual purchases grant. A director, Neil MacGregor, expressly admitted (in a 1997 letter to ArtWatch UK) that “The National Gallery does not have any record, photographic or written, of the back of this picture before it was planed down” – which, as indicated above and as is further shown below, was not the case.

When the senior curator at the time of the 1980 acquisition, Christopher Brown, and his successor, David Jaffé, both held that it was planed down when in the collection of the German magnate, August Neuerberg, between 1930 and 1980, they did so against the testimony of the National Gallery benefactor (who had gifted a Poussin), Christopher Norris. As first mentioned in the 2000 Art Review, Norris testified in a letter to the director in 1980, Michael Levey, that between 1929 and 1980, no change of condition had occurred in the painting, other than a toning down in its 1929 varnish, because the owners had not touched it. Thus, because we know, on Burchard’s (written) testimony held by the National Gallery, that the panel was intact in 1929 when sold to Neuerburg and, on Norris’s (written) testimony, held by the National Gallery, that the owner had never touched the picture, the only parties who might have planed-off the back are Christie’s and the National Gallery. Christie’s, who described and sold the picture as a panel – not as a reduced or marouflaged panel – are hardly likely to have so-transformed someone else’s property – or even to have had the time and means of doing so. On currently available records, the National Gallery, becomes, willy-nilly, the sole candidate, having itself never once described the picture as a planed-down panel before 1983 – and because its own published records testify that the work was an intact panel up to 1982.

REDUCTIO AD ABSURDUM: THE CASE OF A TOTALLY DISAPPEARED NATIONAL GALLERY ALTARPIECE PANEL

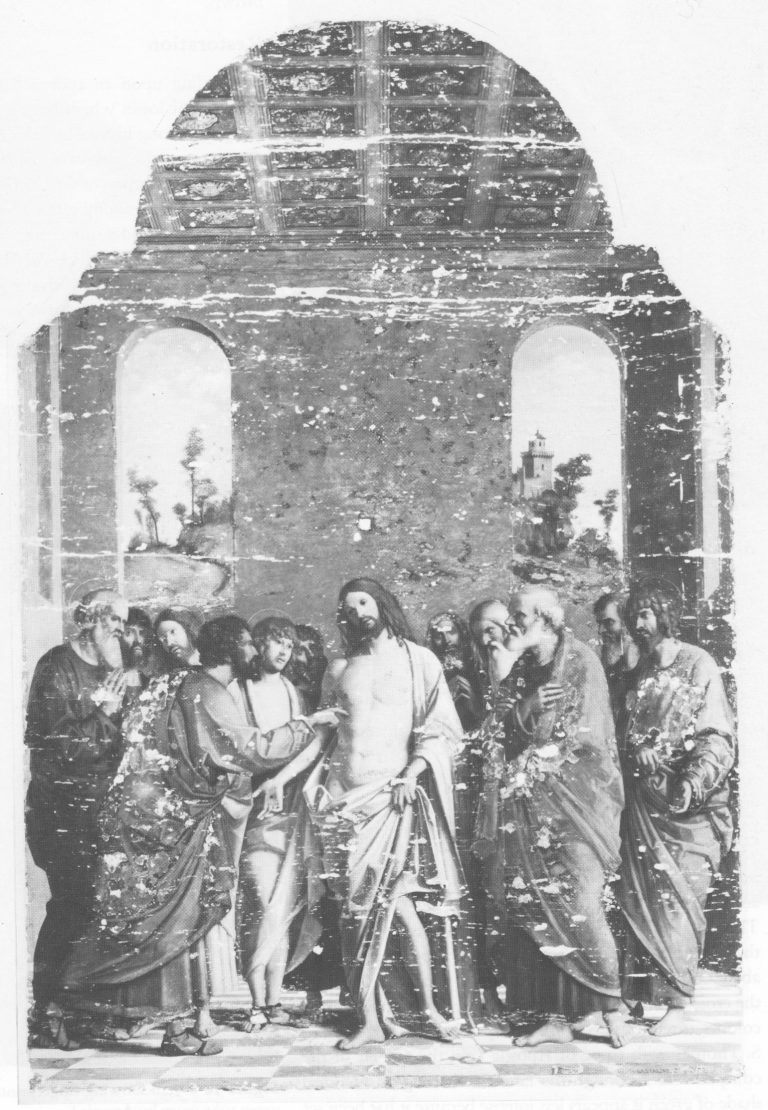

Above, Fig. 8: Top, the National Gallery’s 1504 altarpiece The Incredulity of S. Thomas by Cima da Conegliano, as seen before and after an utterly transforming campaign of restoration in which a modern synthetic composite support was substituted for the original giant poplar panel and a new frame was built to replace the gallery’s own 19th century frame; above, a 1978 pen and ink drawing, “The Ages of Woman”, by the author.

As can be seen above, top, the cleaning and subsequent retouching of the picture surface left a tonally and perspectivally altered appearance: what had been dark and tonally relieving (the back wall) became lighter; what had been contrasted became equalised (the wall and ceiling); what had been dramatically central and axially assertive (the “spotlighted” figure of Christ) became quietened and subsumed within a group. The reduced ornamentation on the new frame left two architecturally assertive raised circles that now vie for attention with the picture’s own depicted half-round windows – which features, the lightening of the wall has brought closer to the picture plane and, therefore, closer also to the new more abstractly assertive frame. The net effect of the physical and pictorial transformations this altarpiece underwent was to leave a painted image surface that is now as flat, de-natured and ahistorical as a giclée print. Above, to a draughtsman (who necessarily commences work on a sheet of – initially – “no-values” to a gradually built-up and considered disposition of “values”, the alterations that are routinely made by restorers during “cleanings” and “restorations” to other artists’ works are as un-missable as they are perplexing and artistically impoverishing.

Above, Fig. 9: Left, the back of the altarpiece panel which was totally removed (i. e. destroyed) and replaced by a multi-layered fibreglass and aluminium board – the long-term stability of which is unknown – during restoration. Right, the diagram of the new, entirely synthetic glass fibre and aluminium support in cross-section, as published in the gallery’s 1985 Technical Bulletin.

Above, Fig. 10: The Cima altarpiece, as published in the 1986 Technical Bulletin with the caption: “The picture after cleaning and transfer, before restoration.”

A MASTERFUL JOB

When Waldemar Januszczak was in art critically doubting mode on the Samson and Delilah’s attribution in October 1997, he addressed the persisting Whodunnit Mystery of the Disappeared Back:

“I put this to the gallery’s chief conservator, Martin Wyld, who quips cheerfully that he was rather proud of having been accused; planing a 17th-century oak panel to wafer thinness and attaching it perfectly to blockboard while leaving its surface in pristine condition, is an exceptional feat of restoration. Nobody would or should do it today. Whoever did it earlier did a masterful job. Why did they do it at all? If a painting is in exceptionally good condition, why was there any need to hazard the transfer to blockboard? A question neither the chief conservator nor MacGregor can answer. All I got them from both is the National Gallery version of: it wasn’t us, guv.”

If stunned by Januszczak’s question, Wyld and MacGregor can hardly have been caught unawares. In a then recent letter in the Daily Telegraph (“Doubts about gallery’s Rubens”, 16 August 1997) we had written on that very question:

“…More disturbingly, crucial technical and documentary evidence concerning the picture’s weak provenance was destroyed when the back of its oak panel was planed away in a mysterious intervention for which no one accepts responsibility and during which no records were kept. The National Gallery claims the planing took place before the picture was bought at Christie’s for a record £2.5 million in 1980. If this was so, two questions arise. Why did the gallery’s trustees authorise the acquisition of a picture with no back (the planed-down remains having been glued on to a sheet of blockboard) and with no documented history of a back? And why did the gallery not ask the vendors, who had owned the painting for 50 years, for an account of the planing and a record of the pre-planed back?… Answers to all these questions lie in the reports that were prepared by the gallery staff for the trustees prior to the 1980 purchase and prior to the gallery’s 1982 cleaning and restoration of the picture. The gallery has not responded to requests that these reports be made available for inspection. Nor is it prepared to produce photographs of the picture’s back, as taken by Christie’s staff before the sale, or by gallery staff before the restoration.”

Unable to answer those questions, the head restorer had clearly been ‘avin a larf when he suggested to the Sunday Times’ art critic that planing a panel down to 3 mm and gluing it onto a sheet of block board was an exceptional feat far beyond anyone’s capacities at the National Gallery. Back then in 1997, a reading of recent National Gallery Technical Bulletins would soon have disclosed the gallery’s great pride in its radical substitutions of modern synthetic composite backings for old pictures’ historic (wood or canvas) supports. We had complained in the 1993 and 1996 James Beck and Michael Daley book Art Restoration: The Culture; the Business and the Scandal of the gallery’s use of the compressed paper “Sundeala” boards on to which Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, Seurat’s The Bathers and Sebastiano’s The Raising of Lazarus had been affixed.

The spectacularly gung-ho treatment of the latter picture – the largest in the Gallery’s collection – epitomised the artistic presumption and techno-adventurism of the gallery’s restorers. The deleterious consequences of that intervention began to be conceded by the gallery’s restorers in its 2009 Technical Bulletin:

“…eventually it was decided to brush on multiple thin layers of warm wax-resin dissolved in white spirit, embedding a layer of inert terylene net fabric [-“Terylene is a specific form of polyester, more specifically polyethylene terephthalate. It is created via the extraction and mixing of ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid. When turned into a fiber with dyes and other treatments, it becomes a great synthetic with a lot of potential in different sectors” ] within the layers as they solidified. Although the discoloured varnishes had yet to be removed from the paint surface, the appearance of the picture was considered to be darker than intended as a result of lack of reflectance from the ground and so titanium white (titanium dioxide) was added to the wax cement…Once the wax and titanium white layers had been built up to a sufficient thickness the painting could then be mounted on a solid new support. This had previously been coated with wax-resin allowing a bond to be achieved by ironing with a thermostatically controlled iron to soften the wax-resin layers which then fused as they cooled. Although it is unlikely that these methods and materials would be used nowadays, the treatment can be judged a success in that there has been no further flaking of the paint layers. Unfortunately, the work took place before the introduction of lightweight and stable panels made from glass fibre with aluminium honeycomb cores. The painting is mounted, therefore, on a support constructed with a ‘sundeala’ composite board outer faces and a core of paper honeycomb. In spite of its wooden edges and an internal wooden framework this panel is now showing signs of instability, with a tendency to flex and twist when the painting is moved, an operation which is therefore avoided as far as possible.” Emphasis added.

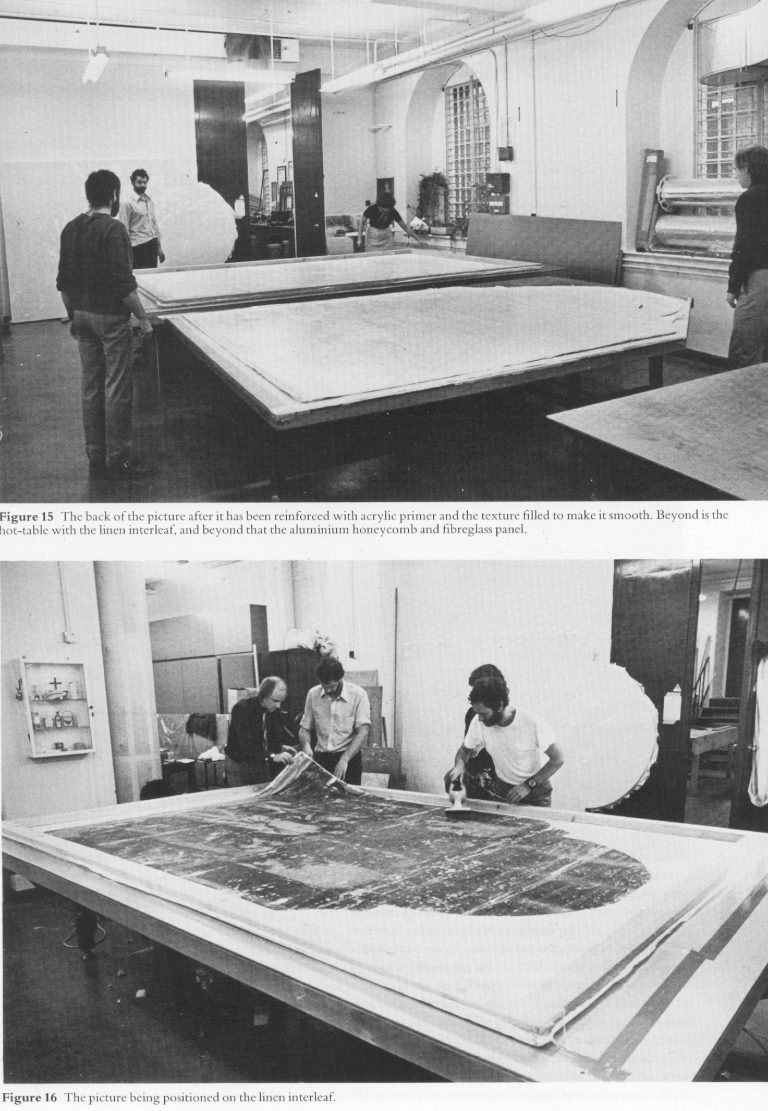

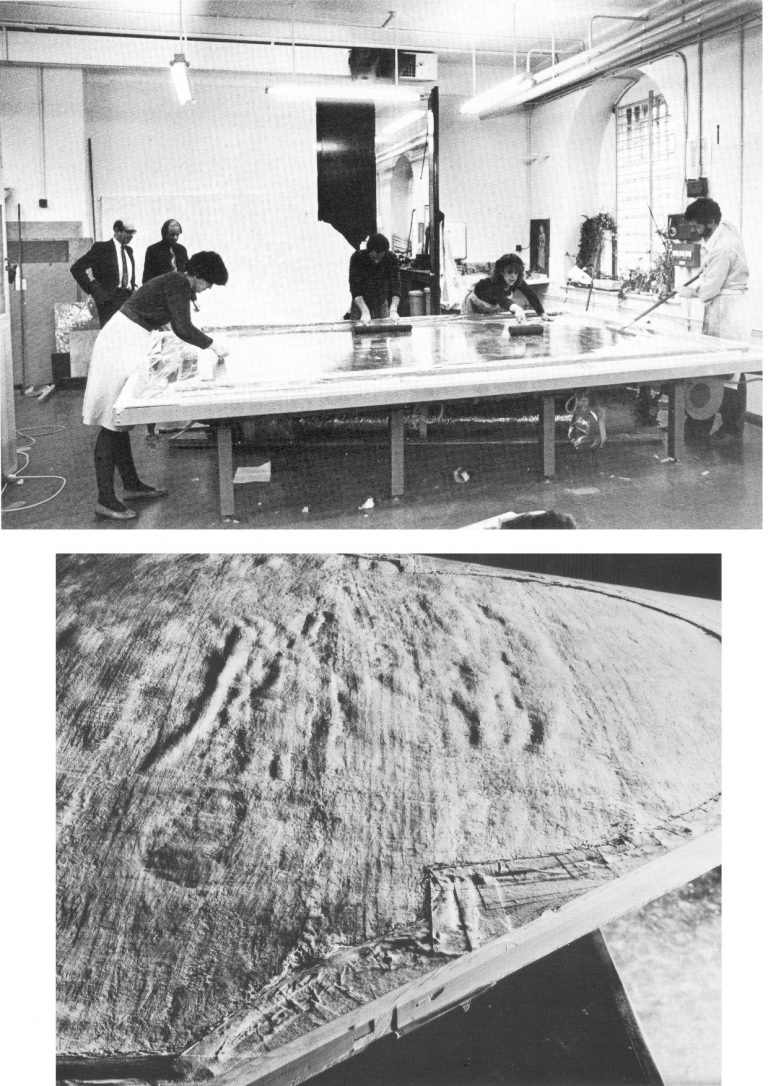

Above, Fig. 11: Staff in the National Gallery’s restoration studio at work on the remains of Cima da Conegliano’s altarpiece, The Incredulity of S. Thomas, after the complete removal of its giant poplar panel and before its transfer onto a multi-layered synthetic support – as shown in the NG’s 1985 Technical Bulletin.

A reading of the 1985 and 1986 Technical Bulletins would have disclosed how gallery restorers had chiselled away the entire wood panel of seven giant planks just under two metres long of Cima’s altarpiece The Incredulity of St Thomas (Figs. 8-10). In the first stage, the panel was reduced “from c. 5 cm to 1 cm.” In the second, the remaining 1 cm of wood was chiselled away entirely until the back of the original gesso coatings was exposed. In the 1985 Technical Bulletin, Martin Wyld described the means and the tools of that perilous operation:

“The removal of the wood then commenced. The techniques used were entirely manual. Though mechanical routers and planes are often used with success in transfer, there is a danger of a power tool, however carefully handled, snagging on knots in the wood or on the bent nails which are mysteriously but commonly found in old panels, and ripping up far more wood than is intended. Semi-circular 15 mm gouges were pushed along the grain, cutting channels 6-7 mm deep, and the ridges left between the channels were then cut down. Each plank was reduced by a similar amount, and the process repeated until the panel had been reduced from c 5 cm to 1 cm in thickness. Many nails were found embedded in the panel and several knots were also cut out.

“The removal of the first layers of wood is usually the easiest part of a transfer [of a paint film to a new support]. The removal of the final layer of wood was complicated by several factors. Many different blister-laying adhesives had been used on the Cima, often in very large quantities. Fig. 6 shows a detail of the Apostles’ heads on the right; the lines of white dots are holes of a syringe in order to inject animal glue under the gesso. Much of this glue, which must have been considerably diluted with water in order to be used in a syringe, had run into the worm channels and soaked into the wood, making the panel surface more brittle…Areas where wax had been used for blister-laying presented less difficulty.

“Experience during earlier transfers had shown that the safest method of removing the last layer of wood was to cut a very shallow slope at a slight angle to the direction of the grain and to shave away the tapered edge of the wood with a small fish-tail chisel. The method proved to be impractical on the Cima. The parts of the panel affected by thick animal glue (of the consistency of carpenter’s glue) or putty filling the worm channels, by knots and by later or original inserts of wood obviously needed individual treatment. However, the remainder of the wood was so insecurely attached to the gesso that it was impossible to cut a shallow slope because strips broke away along the grain no matter how carefully the chisel was used. Strips of wood 10-12 cm long and 3-4 cm wide would become completely detached, but usually with a few small fragments of paint and gesso stuck to them. These fragments were laboriously cut off the wood and replaced… It was found that the safest method of removing the last layer of wood in the very loose areas was to cut it away at an angle of 30 ? to the gesso, instead of across at the very shallow angle normally used, and to cut across rather than along the grain…”

Above, Fig. 12: Top, the director, Michael Levey, and the head restorer, Martin Wyld (top left), watching four restorers in the National Gallery’s basement restoration studios attaching the pictorial remains of Cima da Conegliano’s altarpiece, The Incredulity of S. Thomas, to a linen interleaf on the hot-table after the complete removal of its giant poplar panel and before its transfer onto a multi-layered synthetic support – as shown in the NG’s 1985 Technical Bulletin. Above, the exposed and buckled gesso months after the Cima panel had been chiselled away entirely and the air-conditioning system had malfunctioned.

AN OVERNIGHT MALFUNCTION

Note Wyld’s own account of the “conservation treatment” of the Cima altarpiece:

“Fig. 13 [here, “Fig. 12, above”] shows the arched top of the picture, where the removal of the final layer of wood had started. The panel and gesso had been carefully covered with Melinex and heavy rubber mats all through the transfer, but the gesso had absorbed some moisture from the atmosphere and swollen slightly. An air-conditioning malfunction, which produced RH of 100% for several hours one night, led to pronounced swelling and buckling of the gesso [and the paint layers attached to it] which can be seen in this photograph taken months later.”

Wyld further reported:

“Fig. 13 shows the severe buckling of the top of the picture due to the gesso having absorbed moisture from the atmosphere. Less pronounced buckling had affected some of the lower half of the picture as well. The facing layers had moved with the gesso, and were still secure. The picture was detached from the temporary support and slid face-down onto the Melinex covered hot-table, sealed with a membrane and heated to 40 ? C at a pressure of 15 mbar (1.5 kPa) for an hour. The buckling slowly reduced until the picture was almost flat and relaxed, and the same low pressure, which prevented any alteration of the surface texture, was maintained while the hot-table cooled.”

ALAS, POOR HOLBEIN

The apogee of the white heat of technically transforming restorations was eventually reached in Wyld’s luxuriously long, Esso-sponsored, BBC-televised 1993-96 swank-restoration of Holbein’s The Ambassadors. There, the gallery’s head of restoration produced the world’s first painted insinuation of “virtual reality” into an old master painting by reconstructing the picture’s famous (but damaged) anamorphic skull not according to the laws of perspective by which it had been constructed but from a gallery-generated computer manipulation of a photograph of a medical model of a skull. That operation was defended by the then director, Neil MacGregor on the grounds that “We believe it is our duty to try to present to the public, as much as we can, what the artist intended them to see.” Wyld went further, re-painting a section of the rug to a new design on the authority of a rug expert and painting false and camouflaging “age cracks” onto his own new painting.

And yet, notwithstanding Wyld’s publicly paraded technical expertise, he would have had Waldemar Januszczak believe that the National Gallery’s restorers lacked the wherewithal to reduce a panel to a thickness of c 3 mm and glue it onto a sheet of blockboard.

In the absence of any prior record of a planing, the National Gallery’s last resort defence against suspicions of having carried out the operation has rested on what might seem to be a confession of exceptional negligence – rather as if saying: “With this picture, which we considered a pre-eminent masterpiece within Rubens’ oeuvre and for which we had paid a fortune, we failed to follow our customary procedures and safeguards. We made no records; we took no photographs, neither when we bought it for a world record Rubens price nor earlier, ahead of the sale at Christie’s, when we had borrowed it and were seeking our trustees’ permission to buy it”.

AN OPEN GOAL?

Januszczak might have pressed his point harder. On the absence of records, we had recently reported (“Is this really a Rubens?” The Art Review, July/August 1997) that:

“In the 1980/81 Annual Report the then director, Michael Levey, thanked Christie’s for ‘allowing the trustees to see this painting in the gallery before the sale.’ A trustee at the time has disclosed that in all such purchases curators present a case for the purchase to the trustees who then examine the work ‘in the flesh’. A former Keeper and Deputy Director, Allan Braham, has disclosed that reports on the desirability and condition are prepared by curatorial and conservation staffs for the director before any major purchase…”

A TALE OF TWO OLD PANELS BOUGHT BY THE NATIONAL GALLERY IN 1980

The Gallery’s seeming failure to record and investigate this single work is the more perplexing because the director, Michael Levey, had truly nailed his professional and managerial colours to the painting. He had announced in 1979 that, having reassessed the National Gallery’s holdings of Rubens, he had concluded that it lacked a monumental figurative composition and that he intended to pass this information on to the Trustees at their next Meeting with a recommendation that they should look to acquiring one at the first opportunity. He did not have long to wait for the emergence at Christie’s of the Burchard Samson and Delilah – which might have seemed like a prayer answered. Notwithstanding the eventual very high cost, Levey’s enthusiasm for the picture seemed unbounded. In his foreword to the 1983 “Acquisition in Focus” exhibition, he wrote:

“When on Friday 11th July 1980 the National Gallery acquired at auction in London a Rubens painting of Samson and Delilah – at a cost of over two million pounds – some people might have asked why the nation needed another Rubens. In the Collection at Trafalgar Square there were already twenty paintings by the artist.

“This exhibition, the second in our ‘Acquisition in Focus’ series, will serve as a striking demonstration, I believe, that the painting was indeed needed and will confirm that a crude numbers game in matters of great painters and great paintings is no less obtuse than asking how a piece of canvas [?] can ‘be worth’ so many million pounds. An odd aspect of such questions is that they are rarely directed to areas of national expenditure outside the arts.

“Rubens’ Samson and Delilah is a large scale, early and entirely autograph painting of a kind the National Gallery previously lacked. Its splendid colour and vigorous handling of paint can all the better be appreciated now that it appears cleaned in this exhibition…”

ATTRIBUTIONAL TURBULENCE

If a whiff of defensiveness about the cost of the acquisition might be sensed, it would be understandable: a ferocious dispute was running in the early 1980s between Rubens scholars over the famous paper cartoons-for-tapestries that had been bought for the National Museum Cardiff as by Rubens – and Levey was in the thick of it, having sided with Julius Held who had dissed his arch rival Michael Jaffé’s attribution of the cartoons to Rubens. This would have been the very worst of times for another museum to have been thought to have acquired a dud “Rubens” – and, indeed, for Levey to have been its principal begetter.

In that context, it must be said that the self-declared failure to keep customary (if not statutory) records on the Samson and Delilah stands in bewilderingly sharp contrast with the abundance of prior investigations and records kept and published on another old panel picture bought by the gallery in 1980, (for an undisclosed sum made with contributions from The Art Fund, The Pilgrim Trust and the National Heritage Memorial Fund) – namely, Altdorfer’s Christ taking Leave of His Mother. That purchase was also discussed in the 1983 Technical Bulletin. In Wyld’s report on the treatment of that picture, the first note is headed “The condition on acquisition”. It begins:

“Altdorfer’s Christ taking Leave of his Mother (No. 6463) was examined by the National Gallery Conservation Department before its acquisition in October 1980. As is customary, X-radiographs and infra-red photographs were taken and the picture was studied with infra-red vidicon system and under ultra-violet light…” By those and other examinations it was established ahead of the purchase that the panel was composed of six planks joined vertically and that these had been planed-down to about 6 – 8 mm and cradled. In a section on the subsequent treatment of the panel, Wyld notes of one photograph, “Fig. 5 shows the back of the panel as it was on acquisition…” (Emphasis added.) No such photograph has ever been produced of the Samson and Delilah.

LOOP OF SILENCE

When, on 6 April 2002 (letter), we asked the National Gallery’s then director, Neil MacGregor, whether Dr. Brown had been aware in 1982 of Burchard’s 1930 testimony on the condition of the Samson and Delilah, he replied (letter, 9 April 2002): “As I am sure you know, Christopher Brown left the National Gallery some years ago…I suggest you pursue the matter with him.” When Brown was asked (December 2005) by the US magazine, Salon to comment on his past involvement in the controversy surrounding Samson and Delilah, he replied: “I am sorry but I don’t want to do this. Please address your questions to the National Gallery.” And so, a great silence fell.

On re-visiting the Technical Bulletins today, the mystery of the disappeared picture back deepens. Not only had no one ever spoken of a planing and mounting on blockboard before the picture was acquired in 1980 but no one at the gallery had done so in the two years before the 1983 Plesters/Bomford report. Quite to the contrary, in the 1982 Technical Bulletin, Christopher Brown, Martin Wyld and the gallery’s (now deceased) timber specialist, Anthony Reeve (who was described by Mr MacGregor as the “supreme practitioner of his generation”), wrote on the cleaning and restoration of Rubens’ The Watering Place. In discussing the highly problematic construction of many Rubens’ panels, Reeve wrote:

“Of all the pictures in the National Gallery, Rubens’ panels have been of greater concern, because of their condition, than any other part of the collection. The reason for this is well-known. Rubens frequently found it necessary to enlarge his pictures after he had started painting…Rubens’ oak panels, often enlarged in several different stages, are amongst the most inherently unstable supports used by any artist.”

However, Reeve drew a distinction between “the oak supports which, although made up of many planks joined together, were not enlarged during the painting process, and those which were added to.” On that former, unproblematic, type, Reeve cited just three examples:

“The Rape of the Sabine Women (No. 38) (1.699 x 2.362 m), The Judgement of Paris (No. 6379) (1.339 x 1.1.74 m); Samson and Delilah (No 6461) (1.85 x 2.05 m), the panels of which are made up of six, five and seven oak planks respectively. The grain of every plank, and hence the joins, are horizontal and all the planks are roughly the same width.”

In consequence, Reeve continued, although “these large panels are sensitive to changes in relative humidity (RH), they provide a sound and permanent support if kept in a controlled environment and not exposed to sudden changes in RH.” Conspicuously, he made no mention of the Samson and Delilah as being then a radically reduced panel that had been glued onto a larger blockboard support (Doxiadis reported seeing something like a four inches wide surround of pinkish blockboard when the picture was out of its frame and flat on its back). Of those three fortunate panels Reeve wrote:

“Wood expands and contracts across rather than along its grain. The effect of wood shrinkage of the exposed back [emphasis added] when all the planks are parallel is for the front to become convex, and perhaps slightly corrugated. This shrinkage may cause the joins between the planks to open, or splits to form at the end grain, but treatment and stabilisation are usually straightforward.”

In other words, although all three pictures had been well and favourably constructed, all three were at potential risk of injury through their exposed backs in the event of atmospheric fluctuations – not to mention air-conditioning malfunctions. That was said in 1982. Had the Samson and Delilah already been planed-down to 3 mm and glued or cemented to a larger blockboard panel at that date, a timber craftsman so expert and informed as Reeve could not have bracketed the three panels as being at equal risk of atmospheric changes through their exposed backs.

The planed-down and mounted-on-panel Samson and Delilah artefact described by Plesters and Bomford in 1983 was no longer exposed to fluctuations of humidity: its front was protected by priming, painting and varnish; its back was sealed by its fixture to the blockboard; even its slender 3 mm edges were sealed and protected by putty. Indeed, as Bomford put it in 1983: “Although the nature of this treatment would not find favour today, Samson and Delilah, fortunately, had been treated skilfully. The joins and splits are still secure, the panel is firmly attached to blockboard in all areas and the overall warp (which one might expect to be considerable in a picture of this size) is minimal”. Bomford noted, “no further support treatment is necessary.”

How to account for the two restorers’ discrepancies of accounts between 1982 and 1983? Mr MacGregor once suggested that Burchard might have mistaken a planed-down panel laid on blockboard for an original and intact early 17th century oak panel, but after three decades of removing cradles and reducing panels, Reeve was even less likely to have mistaken a modern blockboard for a 17th century oak panel. He knew the differences well and had noted in the 1981 Technical Bulletin that:

“A very large number of the fifteenth and early sixteenth century Italian panels made of poplar have been planed-down and cradled before they came to the National Gallery collection. This form of panel treatment seems to have been very common in England in the 19th century. The problems caused by the planing-down and cradling vary from panel to panel, but it leaves almost all the panels vulnerable in that they are liable to splitting. Thirty years of experience removing cradles, rejoining splits in the panels and securing them by the method described above has shown that, providing the pictures are then kept in a reasonably well-controlled environment, the panels will remain stable.”

If Burchard truly had mistaken a planed-down panel on blockboard for an original early 17th century, it was a mistake made by everyone else who ever encountered the panel up until the moment it was restored at the National Gallery. Proceeding on the testimony of all the available records, the question might now sensibly be narrowed: who, between 1982 and 1983, planed down the panel and mounted it on blockboard – and who authorised the action?

THE MUTE, ELOQUENT TESTIMONY OF PHOTOGRAPHED BRUSHWORK

While past and present National Gallery players have yet to comment on the Art Recognition findings, eloquent witnesses remain in the Samson and Delilah’s own brushstrokes. Grosvenor’s snap dismissal that computers do not and cannot understand art mis-states the issue: computer programmes do not have to possess all human capacities and levels of understanding to perform otherwise immensely laborious but valuable visual tasks with unerring reliability. To give a commonplace example: for graphic artists who work on A3 or larger sheets, it is prohibitively expensive and space consuming to acquire scanners of corresponding size and capacity; in practice, it not necessary to have such equipment because there are now many computer programmes capable of seamlessly “stitching” overlapping part-scans of large images – as was done with this author’s drawing below at Fig. 13.

Above, Fig. 13: The author’s drawing of Donald Trump’s Relationship with the Republican Party, as published in The Conservative, September 2017.

The earlier revolution of photographic reproduction facilitated all manner of handmade graphic inventions by collage and montage but absolutely seamless conjoining was not possible – the sharpest scalpel cutting through paper cannot do other than leave a trace of its actions. It has taken digitalised computer power to accomplish seamless and effortless manipulations of images and, even, with the advent of AI, of videos. Just as it is not necessary to understand the programming means by which part-images can be invisibly joined, so it is not necessary to envisage the mechanisms whereby a programme might successfully identify distinguishing traits within individual artists’ brushstrokes. Pace Grosvenor, such a programme cannot be deemed theoretically inconceivable for the simple reason that we can already see for ourselves precisely such autographically distinguishing characteristics in paintings – were they not already present and discernible, how would any connoisseur identify any work’s author by eye?

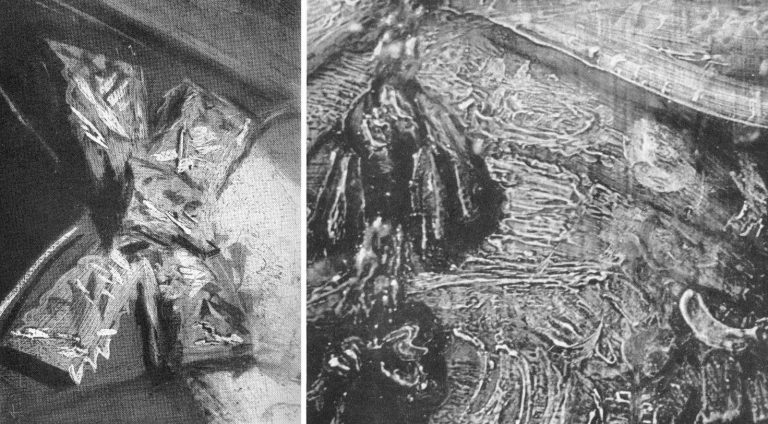

THE NEGLECT OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AIDS TO CONNOISSEURSHIP

Far from being an incredible prospect, the study and evaluation of distinctive brushwork through magnified photographic examination has been around as a diagnostic aid for nearly a century. Despite their proven and demonstrable usefulness, the studies in question and their potential applications have been greatly and perhaps wilfully neglected in subsequent art world practices which have favoured the technical analysis of art’s material components rather than the patterns of artistry which are realised through them.

Above, Fig. 14: An image reproduced in our Journal No. 21 with the following caption:

“This illustration is a photomicrograph of the highlight on the shoulder of [Rembrandt’s] Woman Bathing, National Gallery, No. 54. The patch is pasted on from a photomicrograph of a picture whose attribution had to be tested. It will be seen that the brushwork is identical in both cases. It is possible for a skilful forger to imitate a signature, but it is quite impossible to combine the quality of the paint, the nature of the brush, and the handling of the paint by the painter, so as to reproduce this complete identity.”

So said A. P. Laurie, Professor of Chemistry to the Royal Academy of Arts, in his 1949 book The Techniques of the Great Painters. Would anyone, looking at the above photographic splicing of two brushstrokes from two paintings doubt that both brushstrokes were products of the same author? Professor Laurie was also the author of the invaluable pioneering The Brushwork of Rembrandt and his School (1932), New Light on Old Masters (1935), and, The Painter’s Methods and Materials (1960). Fascinated by scientific means of examining art, Laurie was firm in his conviction that we cannot separate the history of style from the history of artistic technique. Unfortunately, the lesson of Laurie’s penetrating and helpfully clarifying studies were displaced by more clamorous and institutionally self-serving appliances of science – and photography – and in Britain the principal villain had been an earlier director of the National Gallery.

THE PURPORTED SCIENCE OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY

As a very young (and Lord Duveen-engineered) director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, whose picture cleanings produced fury among artists, set up a scientific department so as, as he put it in his 1977 autobiography, to “have in the background what purported to be scientific evidence to ‘prove’ that every precaution had been taken [by the gallery’s restorers and curators].” In pronounced contrast, Laurie’s impeccably disinterested and transparent method was conducted in good faith.

First, he explained, by magnifying details of paintings: “…we isolate the drawing with the brush: we magnify the individual strokes, and, owing to the dark varnish lying in the hollows of the paint, reveal every stroke of the brush with the utmost definiteness.” Second, “If we now proceed to take silver prints of the magnified photographs of two pictures, one known and the other unknown, and cutting up the one, put a portion of the other print so adjusted that the strokes of the brush follow on, we have an infallible method of identification.”

Thus, Laurie appreciated, the marks of brushes left in paint can be as “forensically” helpful as the rifling marks on a bullet. Unlike Plesters, Laurie combined technical ingenuity with artistic perspicacity. On his schema, great precision of identifications of authorship might indeed be attained by almost anyone – and therein may lie the rub and an explanation of institutional resistance and exclusion: his method demystified the mumbo-jumbo of pseudo-scientific museum world “conservation”.

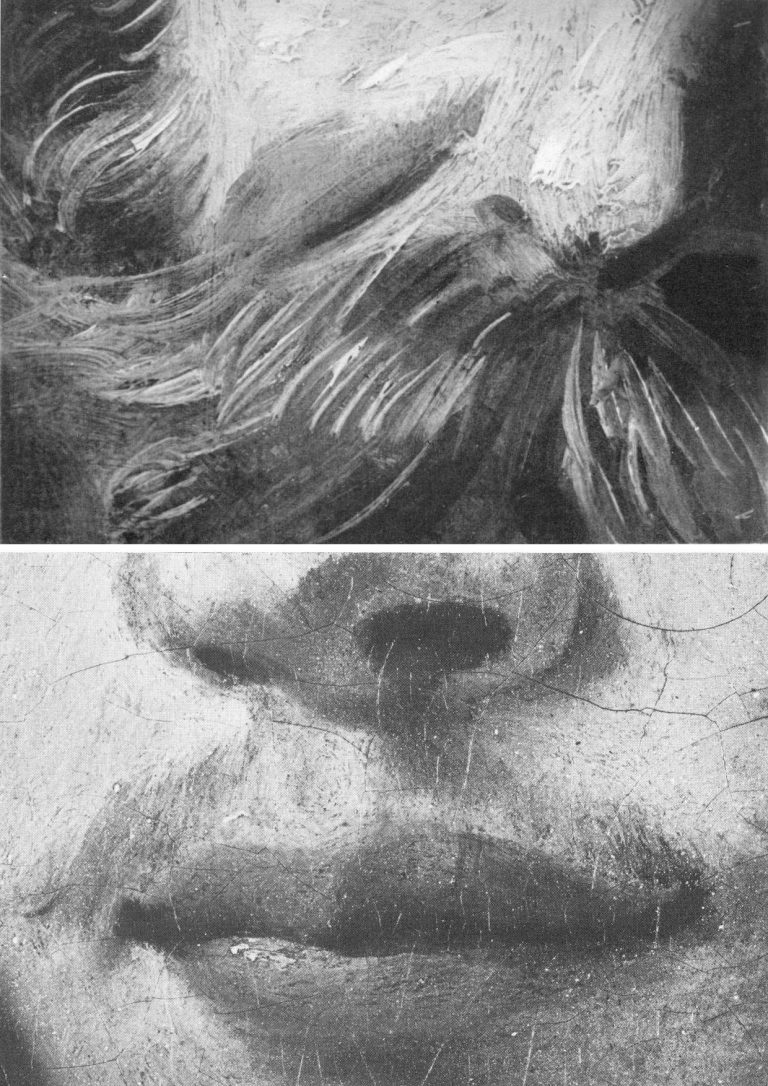

On the certainly pertinent and potential tripwire question “Can we be sure that artists brushstrokes do not evolve to the point of transformation?” Laurie answered in the affirmative: “As in writing, once a painter has formed his style of brushwork, it is curiously persistent. His pictures may alter with the years: they may develop a greater depth of meaning and a richer quality, as we find with Rembrandt, but the brushwork remains the same.” Laurie, who claimed nothing that he was unable to demonstrate for all to see, continued: “Now take a jump from 1633 to about 1660 and examine through a lens the impasto of the portrait of himself (No. 221 in the National Gallery). You will recognise the same impasto, though with a more stiffly ground paint. Or again, the lens will reveal same impasto as in the portrait of Titus in the Wallace Collection. [See Fig. 15 below] A study of these three painters, Velazquez, Rembrandt and Frans Hals will soon convince the reader of the truth of what has been said above. If then we can emphasise this characteristic, we have a powerful weapon to assist in the attribution of painters.”

Above, Fig. 15: Top, in this juxtaposition of the eye in the Wallace Collection portrait of Titus, (the condition of which Laurie described as above in his ground-breaking 1932 study of Rembrandt’s brushwork) and, above, the eye in the National Gallery self-portrait (of which picture’s condition Laurie noted “This, except for the coarse repairs in the corner of the eye and on the upper lip, is in excellent condition and is the best example of his latest manner I have seen which has not been injured by the restorer”), it can be seen that Rembrandt’s brushwork could swish without change through time.