The restoration injuries on Klimt’s paintings now rival those seen on Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes. Both cases testify to profession-wide failures to read pictures as art and to heed the testimony of photo-records – that is, they testify to the linked failures of restorers who inflict damage and of scholars who accommodate adulterated works within their narrative accounts.

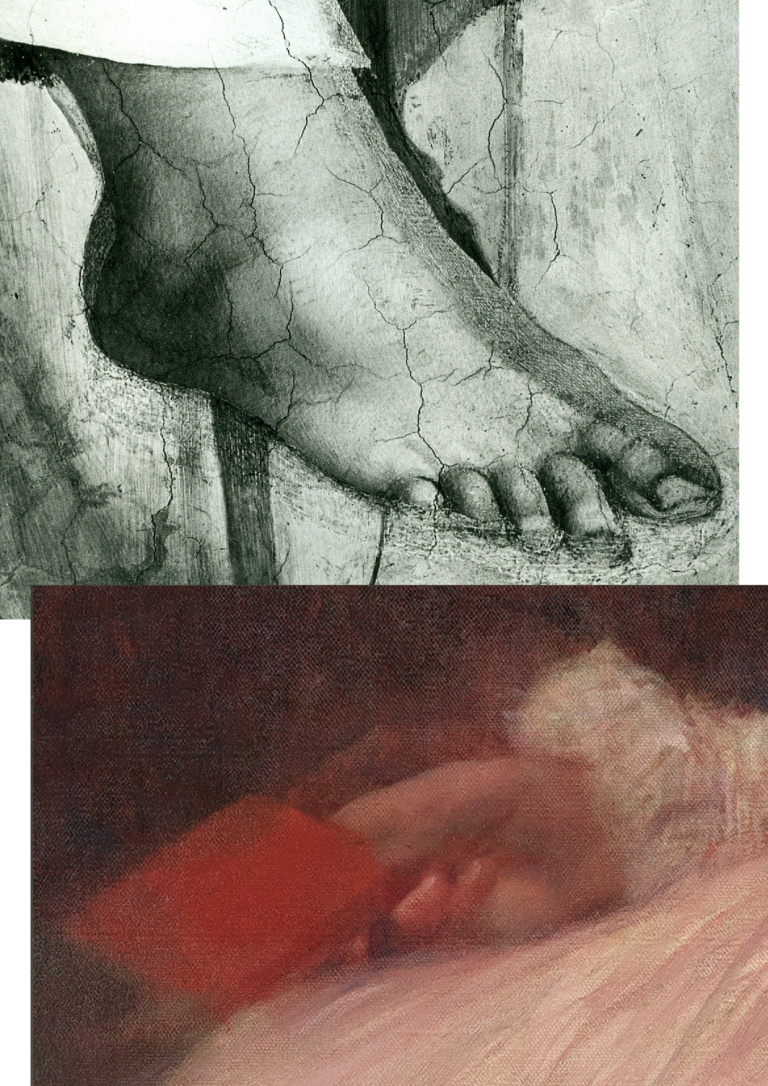

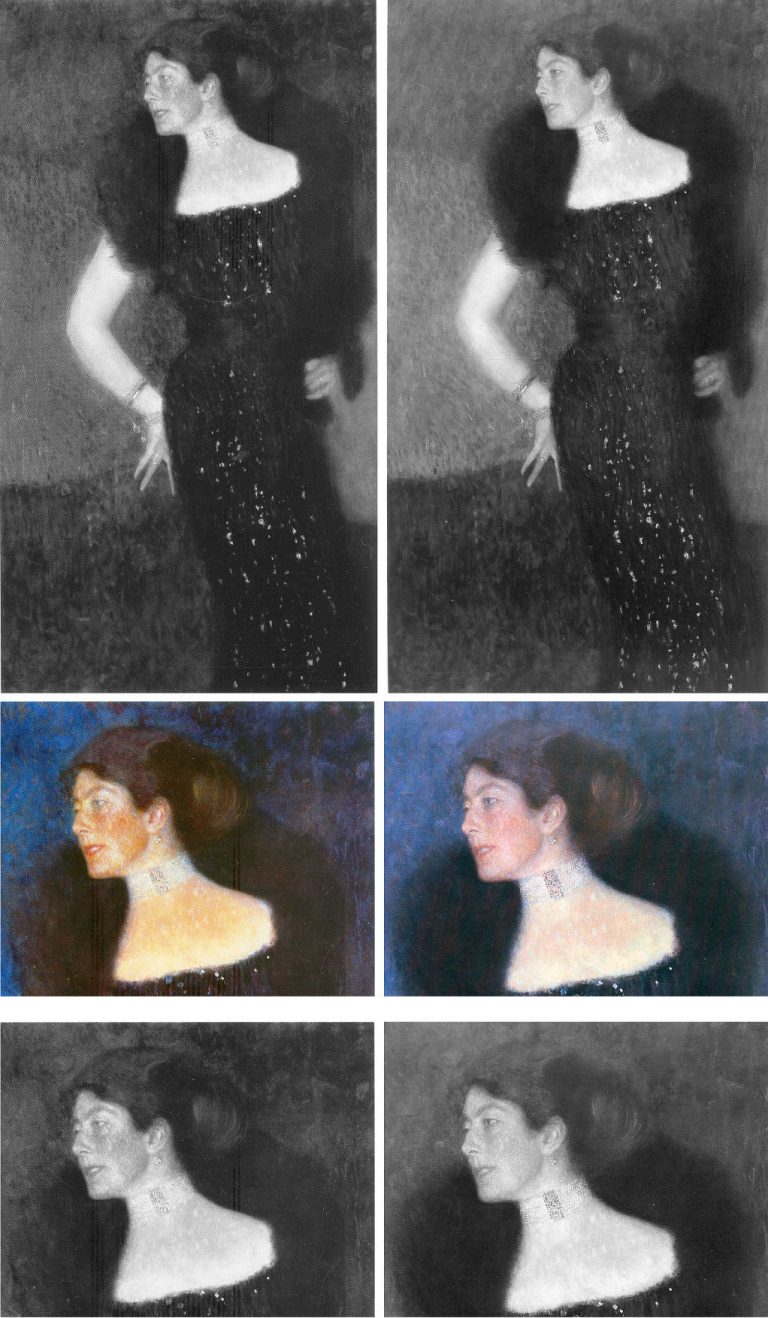

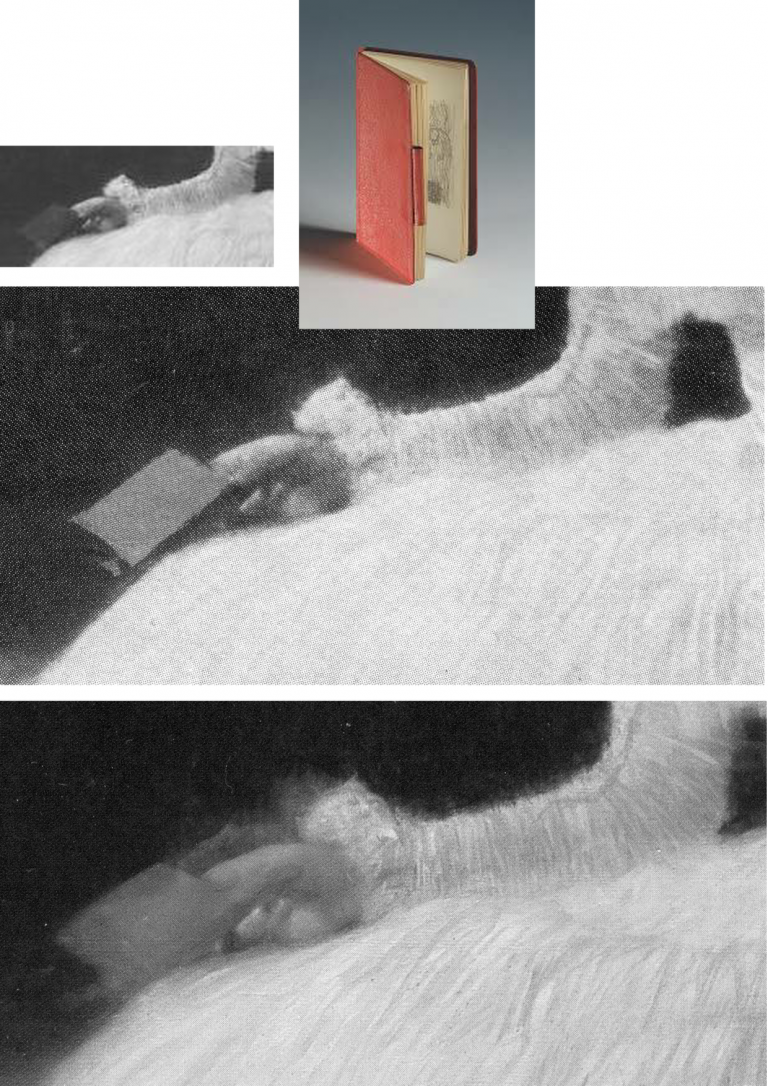

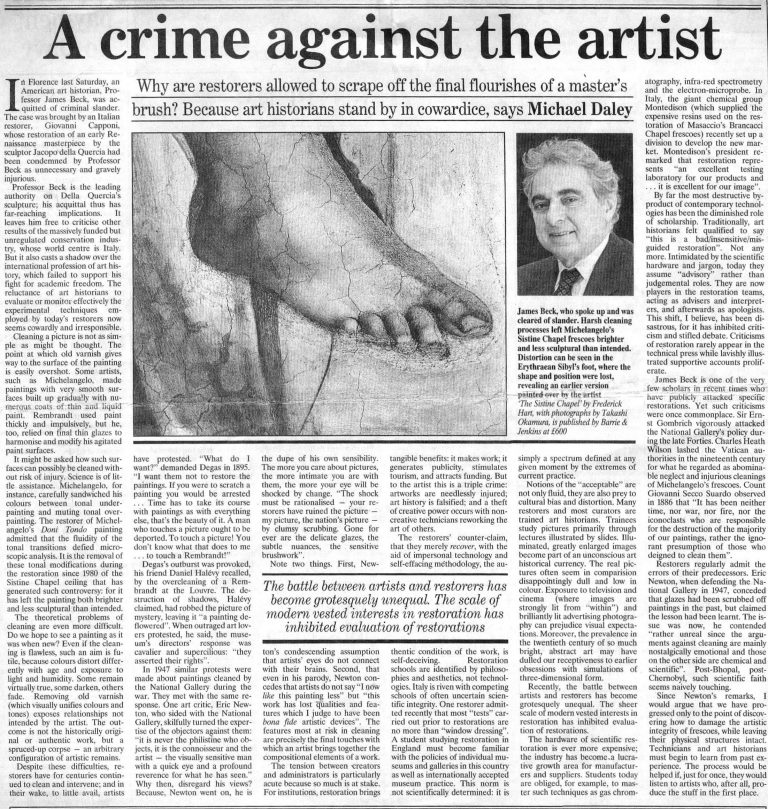

Above, Fig. 1: Top, the after-restoration right foot of Michelangelo’s monumental Erythraean Sibyl on the Sistine Chapel ceiling; below, the after-restoration right hand in Klimt’s 1898 Portrait of Sonja Knips, as seen today (in the Galerie Belvedere, Vienna).

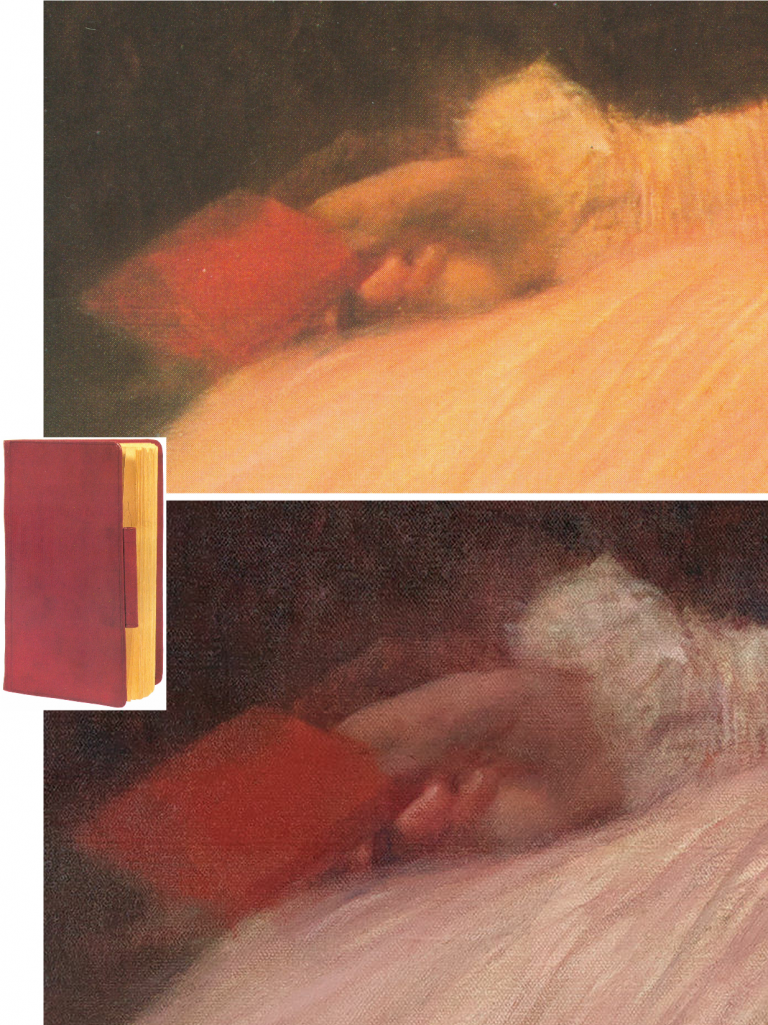

Above, Fig. 2: Top, the after-restoration right hand in Klimt’s Portrait of Sonja Knips, as in Christian M. Nebehay’s 1992 Gustav Klimt; above, the after-restoration right hand in the Portrait of Sonja Knips today. Inset, left, the book held by Sonja Knips in Klimt’s portrait.

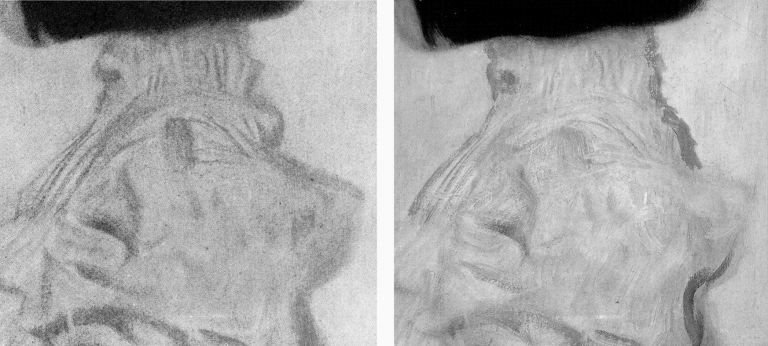

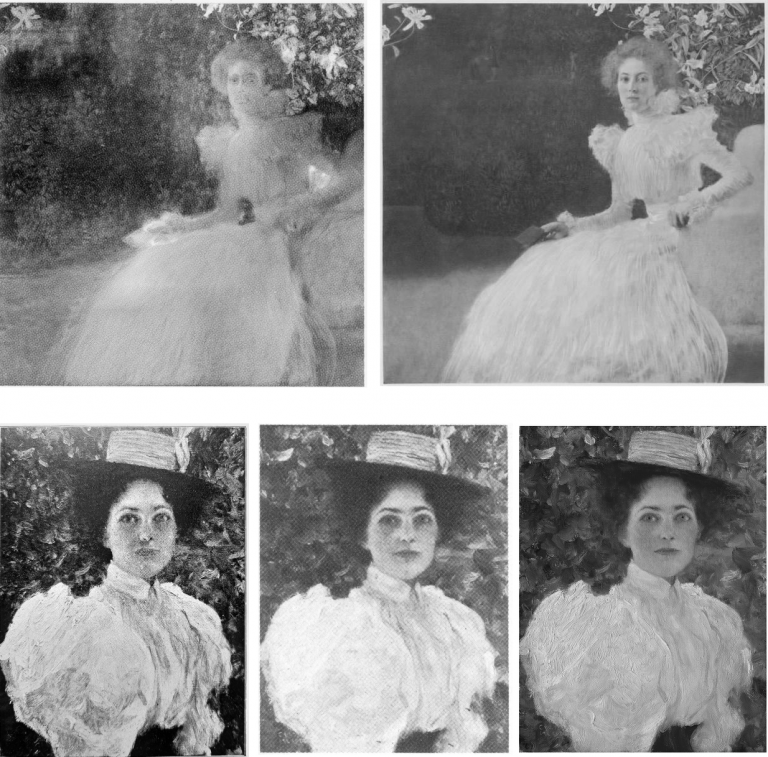

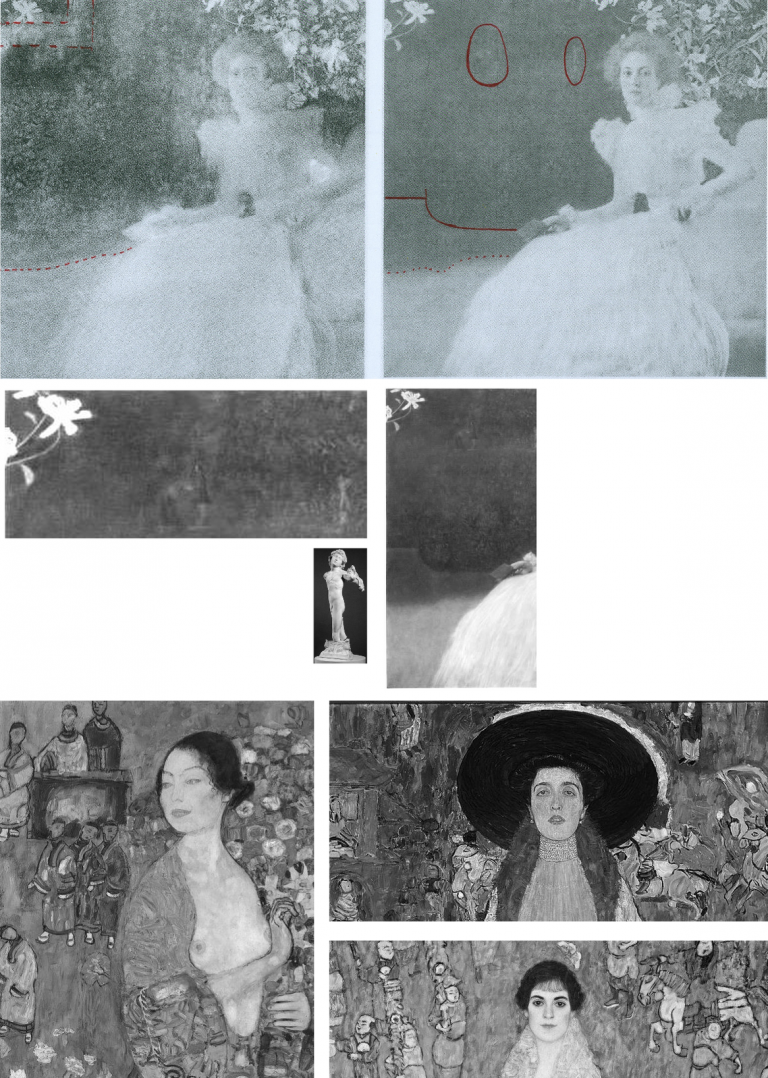

Above, Fig. 3: A detail of Klimt’s portrait of Helene Klimt as seen before restoration, left, in 1956 and after restoration, right, in 2012.

While the injuries to the two artists are comparable in magnitude, the means are quite unalike. With the Sistine Chapel, there is no mystery about the cause. Before the cleaning of the ceiling started (after the cleaning of Michelangelo’s lunettes on the chapel’s upper walls), leading Michelangelo scholars endorsed a Dan Brown-esque claim that self-declared New-Era restorers had uncovered a New Michelangelo whose true traits had gone unnoticed by all those who had, in the artist’s lifetime and for nearly half a millennium afterwards, copied and studied his work. The claim was preposterous, but the fact of the ceiling’s highly controversial and radically transformed appearance was acknowledged by all parties and is now on the historical record. Moreover, twenty-two years after the greatly contested restoration finished, the late chief restorer, Gianluigi Colalucci, admitted that his predecessor at the Vatican, Luigi Brandi, “the old chief restorer”, had warned him that Michelangelo had conducted much if not most of his painting with “pigments perhaps diluted with oil or resin or varnish” on the fresco surface.

What neither Colalucci nor the Vatican ever acknowledged was that in the late 1980s, as we had first reported in 1993, Leonetto Tintori, the restorer of Masaccio’s Trinity in the Santa Maria Novella, Florence, and a member of the international committee that investigated the controversial cleaning in the mid-1980s, had “urged the Sistine team privately to preserve what he termed ‘Michelangelo’s auxiliary techniques’ which in his view included oil painting as well as glue-based secco”.

Cleaning the ceiling had been thought impossible because of the complexity and vulnerability of Michelangelo’s method. To justify the use throughout the ceiling of a ferocious solvent gel that was robotically brushed on and washed off twice in twenty-fours like an oven cleaner in a pre-determined method devised to ensure a homogenous appearance, the restorers and curators claimed – against material and documentary evidence – that Michelangelo had not worked on top of his frescoes when dry. The Vatican never delivered a report on the restoration and now, with the death of Colalucci, never will. The photo-record, thanks to digitalisation and the web will endure.

With Klimt’s oeuvre, the debilitation occurred piecemeal in public and private collections over (roughly) half a century and on no overtly declared programme. Again, thanks to photography, there can be no long-term cover for mis-restorations because we know how Klimt left his works and can calibrate and demonstrate injuries to them, as with the two portraits of Sonja Knips and Helene Klimt.

Klimt’s instruction that those wishing to understand him need only look at his pictures is widely acknowledged but little comprehended. “I am convinced that I am not particularly interesting as a person”, he had written, “if anyone wants to find out about me – as an artist, the only capacity in which I am of any note – they should look carefully at my paintings and try to learn from them what I am and what I have tried to achieve.”

That is no longer possible. It no more occurred to Klimt that his works would cease to bear true witness than it had to Michelangelo that he would one day be hailed as the Matisse of the Renaissance by a restorer (see our “Maestro Colalucci: His Method and its Madness”, Jackdaw, May/June 2021, and “A crime against the artist”, The Independent, 22 November 1991, at Fig. 34 below.) Now, a century on from Klimt’s death and with scarcely a single picture true to its original self, the most charitable view of scholarly silences on injuries might be to assume that those who depend on access to Klimt’s works and records either know or fear they cannot afford professionally to embarrass private or institutional owners by citing past or recent injuries. However, Klimt scholarship and publications have exploded in recent years and it is now possible (through photo-illustrations) to make fair appraisals of the various changes his works have undergone at the hands of restorers – even though their actions remain almost nowhere acknowledged.

HELENE KLIMT: ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

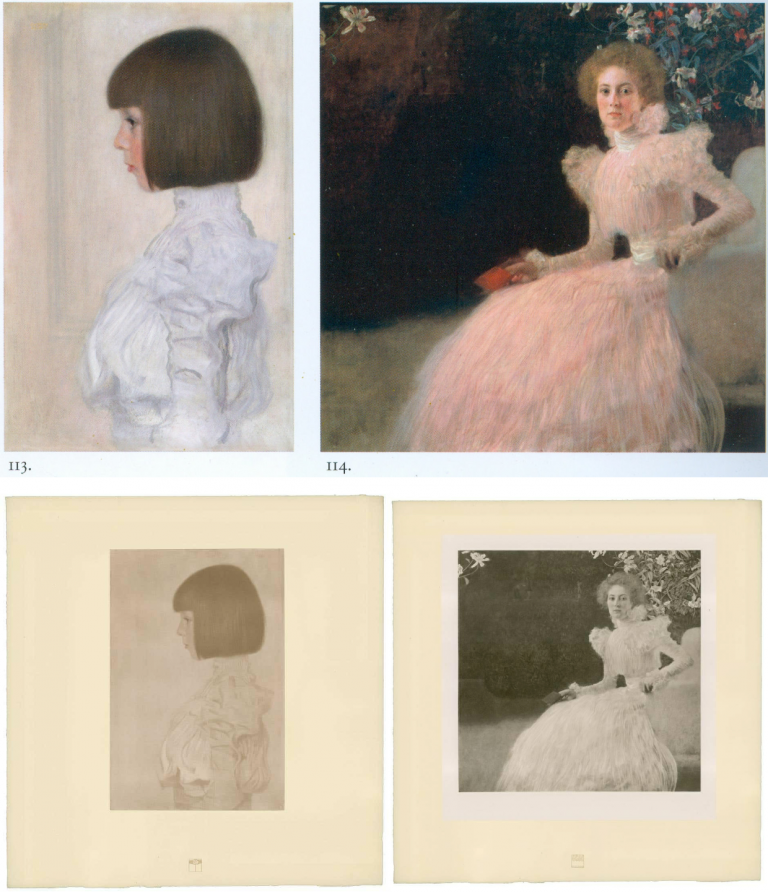

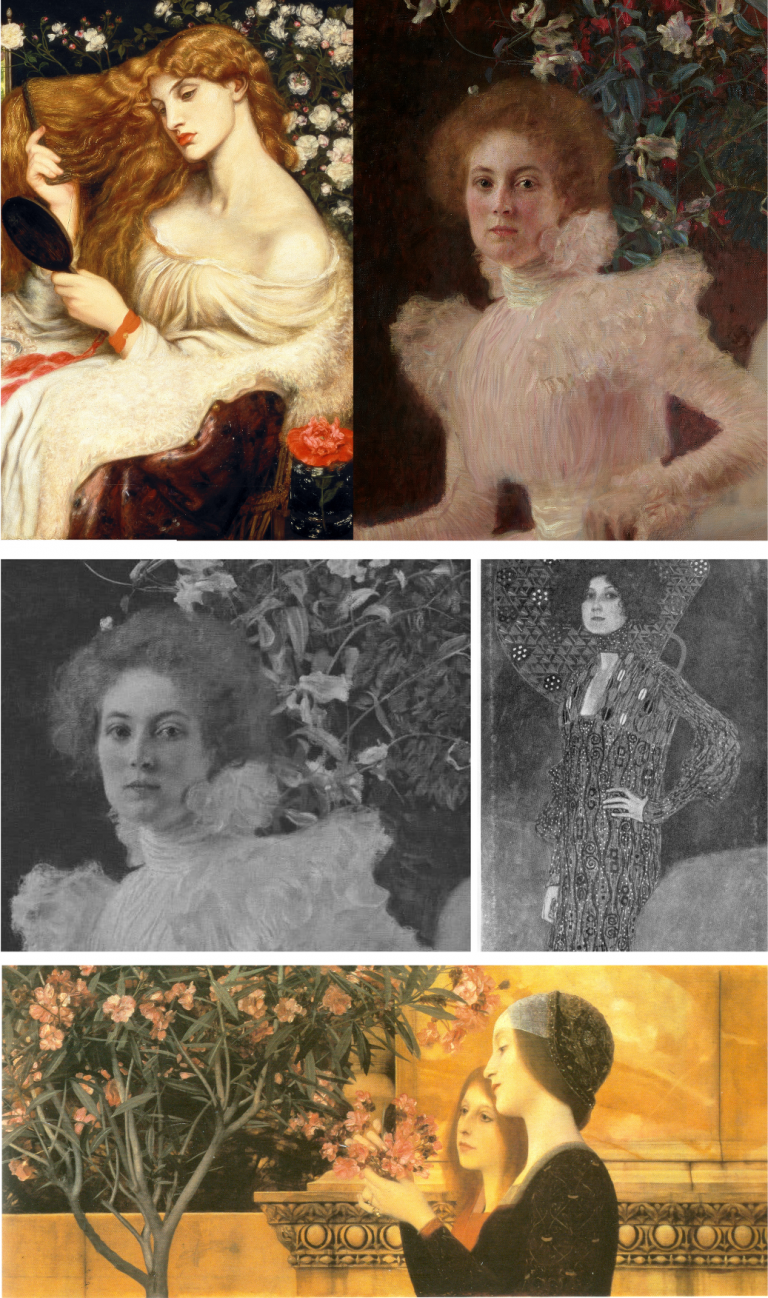

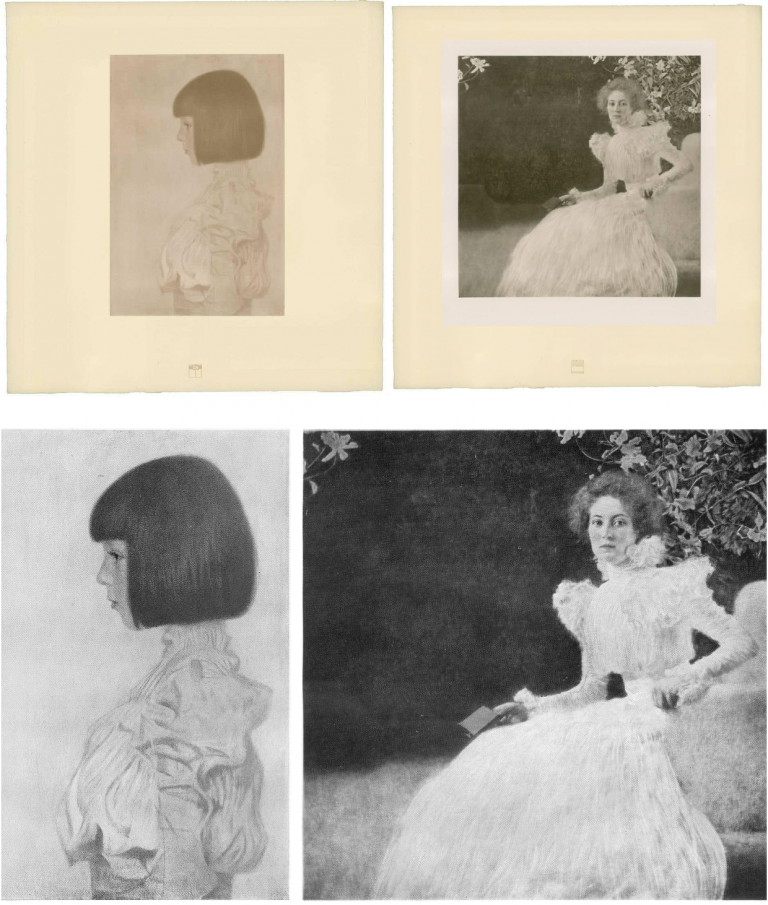

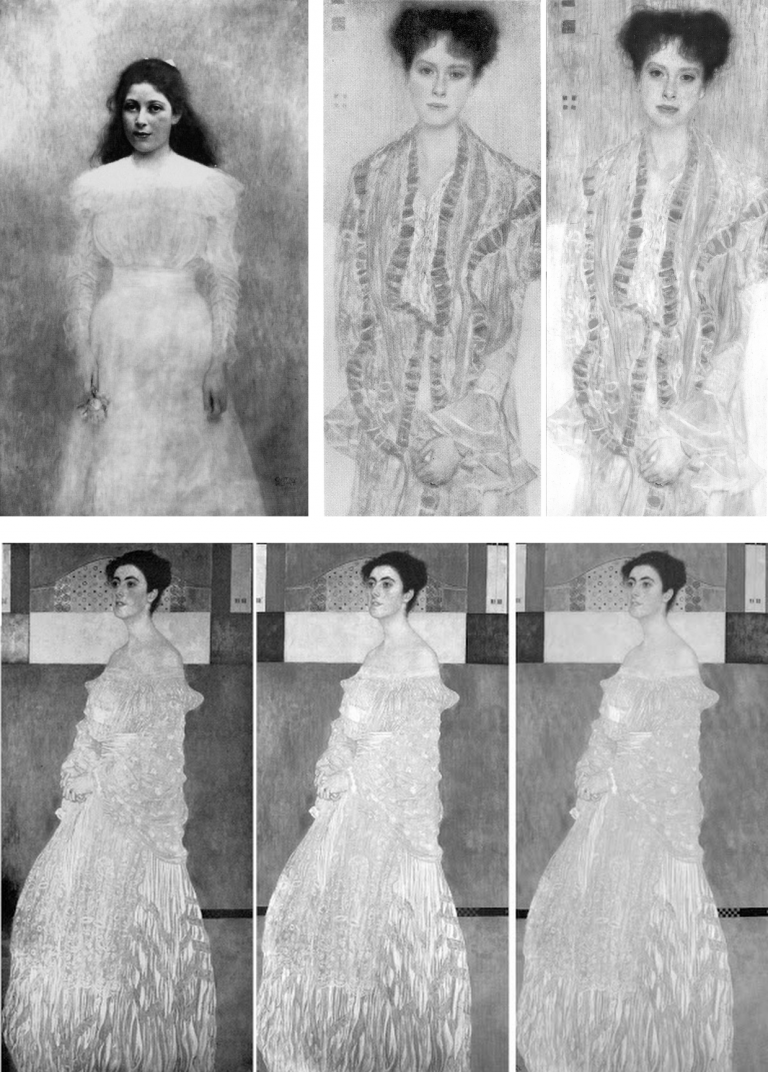

Fig. 4, above: Top, Klimt’s portraits of Helene Klimt and Sonja Knips, as bracketed in the precious and giant – it weighs 16 lbs – 2012 Taschen Gustav Klimt The Complete Paintings, Ed. Tobias G. Natter; above, the Klimt and Knips portraits as published with Klimt’s approval between 1908-14.

As Dr Natter hoped, the Taschen book is now a standard work of reference. His ambition to supplement updated “details about each work, its provenance, exhibition history and selected bibliographic references” with a picture of “how it was received in its day” proves richly informative. Notwithstanding such art historical diligence, no account is given of what restorers euphemise as pictures’ “conservation histories” and therefore this book, like all others in the field, fails to address how each work looked in its day and to estimate how much or how little it does so today. Seemingly failing to recognise that every work of visual art starts life as its own primary document, this ambitious book takes what restorers have left in their wake as synonymous with the art Klimt produced. As is customary in the field, Natter expresses deep and sincere gratitude to all owners and “in particular, the private owners” for their trust, helpfulness, and inspiring conversations.

ART HISTORICAL NARRATIVES

One of the book’s contributors, Susanna Partsch, (“Paintings of women”), sets the above two portraits as staging posts in a now prevalent art historical schema:

“The earliest portraits on display at that occasion [a 1903 Klimt exhibition] were the private ones of his young niece Helene Klimt and the Portrait of Sonja Knips both of which were completed in 1898. The some twenty portraits that Klimt produced between 1891 and 1898, most of them showing anonymous models, seem to have been finger exercises on the way to a new style.”

With the Portrait of Helene Klimt, the artist’s then six years old niece who became his ward on the death of his brother (Fig. 4, above left), Natter jumps straight into formalist art criticism:

“If Klimt’s portraits of the early 1890s had shown him dissolving line and blurring colour in a painterly manner, the artist here explores the harmony of the strict profile view. This is reinforced by the precision of the page-boy haircut, the neutral background and the high-necked blouse, its fabric interpreted and ennobled by the generosity of the execution. The dualism of mimesis and dissolution, of faithful reproduction and painterly openness, is already in evidence here as a stylistic means.” (Emphases added.)

Thus, the head is said to be painted in one manner and the blouse in a radically contrary one, but this supposed pictorial dichotomy rests on an assumption that the picture’s present traits are as when originally executed when the photo-record (at Fig. 3 and below) testifies that they are not. Natter cites but does not reproduce an early record of the Portrait of Helene Klimt: “A previously unheeded photograph published in the magazine Das Interieur in 1911 [that] shows the child’s portrait hanging in a bedroom in the Flöge sisters’ home in Ungargasse, Vienna (N.N. 1911).” Having brought photography to the table, Natter neglects to consider the testimony of the earliest published photographs of this painting including one above at Fig. 4 of 1908-14 which Klimt himself had carefully vetted and endorsed.

This profession-wide neglect of historical photo-records persists even as Klimt’s own use of photography attracts attention. In 2012 Prestel published Gustav Klimt & Emilie Flöge Photographs, edited by Agnes Husslein-Arco and Alfred Weidinger, the scientific director of the Linz Upper Austrian State Museum; former vice-president of the Belvedere in Vienna; and a digital and film photography specialist with a preference for black and white images. Agnes Husslein-Arco, a former figure skater and Sotheby’s Austrian director, was director of the Belvedere museum between 2007 and 2016 and is credited with transforming it into a major tourist attraction in Vienna. In the book’s preface, the then director said: “The product, a chronological presentation of photographs and snapshots, illustrates a biographical panoptic of these two personalities who were so influential in the fin-de-siècle art world…The following contribution by Alfred Weidinger provides information about Klimt’s relationship to photography and the use of the same in his artistic creations.” Weidinger wrote: “The reference to Klimt’s involvement with photography, only briefly sketched out here, is meant to offer a first look at a hitherto neglected area of Klimt research, and, at the same time, make evident the importance of this medium to the artist.”

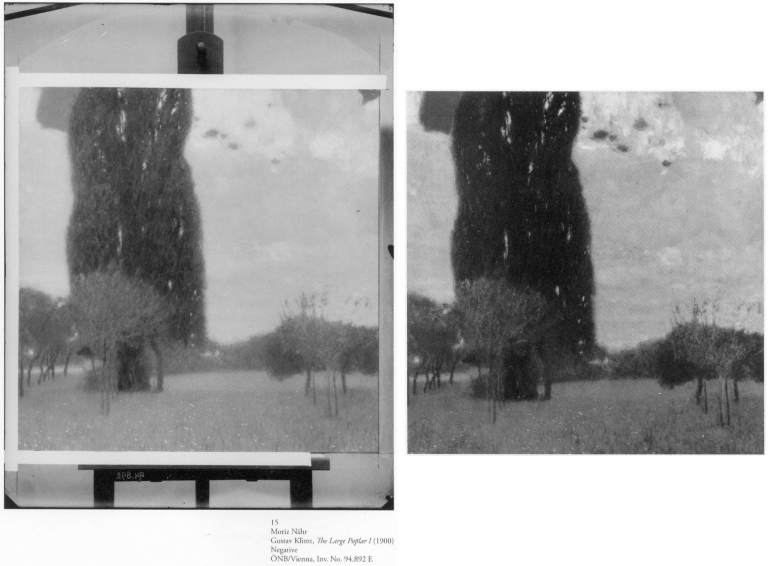

Above, Fig. 5: Left, one of a group of Moriz Nähr photographs acquired by the Austrian National Library in 1943 that recorded both Klimt himself and “revealing reproductions” of his paintings, as here above left with his 1900 The Large Poplar I. Above right, The Large Poplar I, as reproduced (with slightly trimmed edges) in Alfred Weidinger’s 2007 Prestel Gustav Klimt – an earlier massive and compendious complete catalogue with specialist essays which had weighed in at a respectable 10 lbs. Weidinger expressed the hope that the book, which offered a fundamentally new basis for research, “holds out an invitation to discover many new aspects of the life and work of the great painter whose artistic home is the Vienna Belvedere.” (We welcome and accept that invitation.)

A SECOND OPINION

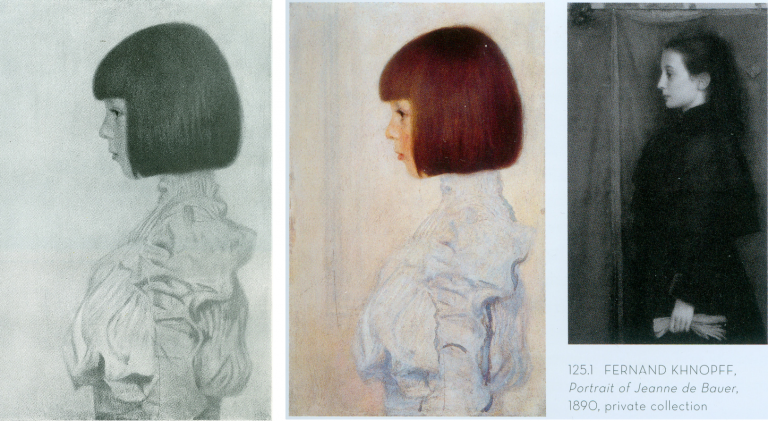

Above, Fig. 6: Left, Klimt’s 1898 portrait of his niece (and later ward), Helene Klimt, as published in Emil Pirchan’s pioneering 1942 and 1956 book Gustav Klimt and, centre and right, Helene, as paired with a Fernand Knopff profile portrait by Alfred Weidinger in his 2007 Gustav Klimt.

As with Dr Natter, Dr Weidinger’s catalogue entry on the Helene Klimt portrait made no reference to the Pirchan book’s photographic testimony. Instead, he drew attention to Klimt’s apparent indebtedness to an 1890 Fernand Knopff portrait in which “a severely profiled half-length portrait faces to the left, with an almost monochrome background which is divided into two areas by a thick brown vertical line.” Weidinger further notes that while Klimt “reduces his composition to the girl and the pale background we may detect a reminder of Knopff’s composition in the group of vertical lines in the front of Helene’s face, which in the Jeanne de Bauer portrait, functions as a special accent”. The stylistic comparison with Knopff is apt and fair but no mention is made of the photographically recorded fact that the lines to which Weidinger refers had not been visible in the picture in its 1908-14 and 1942-1956 photographs.

Weidinger takes pride that it had been “a major concern of ours to see, as far as possible, all Klimt’s pictures in the original and to take new photographs of them” and that their wishes had been met in the great majority of cases. That the lines in the portrait’s background had not previously been present must mean that they had emerged in a post-1956 restoration, which in turn suggests that a restorer had uncovered and left exposed a feature previously begun and then painted out by Klimt, perhaps because of second thoughts about introducing a parallel secondary motif that would have stood distractingly in competition with the picture’s subject.

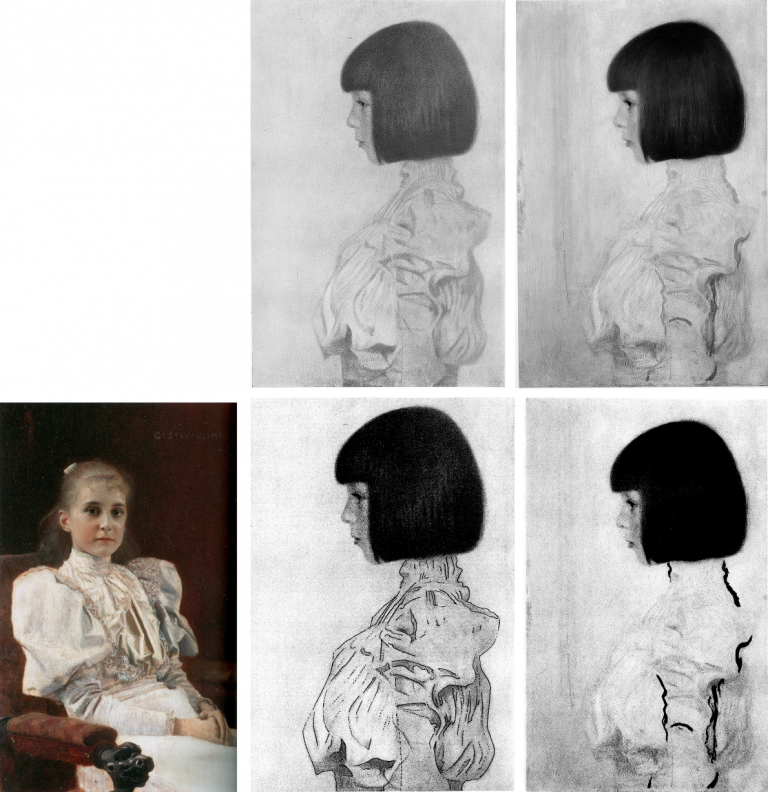

Above, Fig. 7: Left, Klimt’s portrait of Helene Klimt as recorded before 1956 in Pirchan; right, the portrait as reproduced by Weidinger in 2007.

Had Weidinger compared the above pair of images he would surely have noted not only the late emergence of the lines but also the many changes to the blouse – and perhaps have offered some account for them. Instead, and seemingly accepting the 2007 state as if Klimt’s own, he drew a stylistic distinction between the treatment of the undamaged head – “the fine brushstrokes with which Klimt renders her hairstyle and profile give a draughtsman-like character to the girl’s head” – and the body, where: “the treatment of the high necked, puff-sleeved blouse, which Klimt paints in cream and light blue tones, is sketchy.” In 2012, Natter saw more in the blouse than sketchiness – viz: “fabric interpreted and ennobled by the generosity of the execution”; and, in the now disrupted head/blouse relationship, “a dualism of mimesis and dissolution, of faithful reproduction and painterly openness”. The photo record shows that both scholars missed countless injuries and adulterations to the blouse – including superimpositions that crudely redrew the collar and the arm’s contours – all of which they took to comprise evidence of a significant step in the march of Klimt’s stylistic development of which Partsch spoke in 2012.

Had Weidinger addressed such a comparison as that above, he would likely have seen that the draughtsman-like character of the head had been no less evident in the economical but precise elegant treatment of blouse, too, and that viewed as a whole, the work had originally shown no great dichotomy of pictorial means and, rather, comprised a beautifully measured record of a young girl’s dutifully patient self-conscious expression and resolute little soldier-like stance.

Above, Fig. 8: Left, Klimt’s portrait of Helene Klimt as in Weidinger, 2007 and, right, as reproduced by Natter in 2012.

The above, same-size, greyscale, direct photo-comparison shows that the painting underwent further changes between 2007 and 2012: the long-invisible vertical lines that emerged in 2007 had by 2012 turned more clearly towards the child suggesting a framed picture on a parallel background wall; an area of damage in the centre of the picture’s left edge that was visible in 2007 has been touched out, as were several scratches of long-standing.

Above, Fig. 9: Klimt’s portrait of Helene Klimt as recorded, left, between 1908-14; as before 1956, second left; as by Weidinger in 2007, second right; right, as by Natter in 2012.

Comparing four same-size successive photographs above shows the first two records of the blouse (1908-14 and 1942-56) to be identical and radically different from the two in 2007 and 2012. The post-2007 traits that are now enshrined in the literature as “sketchy”, or an “ennoblement by generosity of execution” can be seen on a simple photo-comparison to be products of hands other than Klimt’s. The photographic record incontrovertibly shows that in this portrait, autograph features that survived until at least 1956 were subsequently weakened or erased, and that new and stylistically alien contours had been added in an evident attempt to simulate something of the then-botched blouse’s original coherence and richness of design. Thus, field-leading contemporary scholarship had failed to notice, acknowledge, or condemn a vandalising act of bowdlerisation. Instead, it has incorporated a restorer’s deformations into a celebratory narrative of a privately owned work that is on loan to a public museum (Berne, Kunstmuseum).

Above, Fig. 10: Top, left, Klimt’s Portrait of Helene Klimt in Pirchan, 1956; and, top right, in Weidinger’s 2007 Gustav Klimt. Above, left, Klimt’s 1894 Seated Young Girl; above, centre and right, a diagram showing first the 1956 Pirchan illustration with the then folds of the blouse outlined in black, and right, with what we take to be a post-1956 restorer’s superimpositions also identified in black.

Weidinger’s comments on Klimt’s indebtedness to Knopff (and to Whistler) are constructive and, in Klimt’s early Seated Young Girl, above left, he sees indebtedness to both Klimt’s brother, Ernst, and their joint master, the painter Hans Makart. Despite such fine-tuned stylistic discrimination, Weidinger seems to see no relation in the Seated Young Girl to Helene’s blouse. Had Natter addressed the losses and additions in the post-1956 blouse, would he have spoken of a “dualism of mimesis and dissolution, of faithful reproduction and painterly openness, [that] is already in evidence here as a stylistic means” in Klimt’s supposedly contrasting handling of the head and blouse? The blunt tuth is that, with Helene’s blouse, the dissolution was chemically and physically induced decades after Klimt’s death by an unidentified restorer on an unrecorded/undisclosed occasion.

SONJA KNIPS

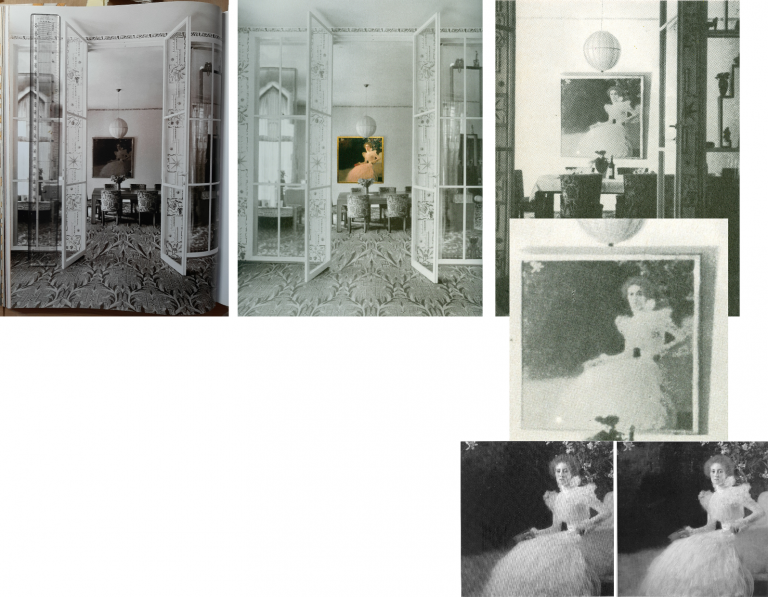

Above, Fig. 11: A 1915 photograph of the Sonja Knips portrait in the dining room of the Villa Knips, as in the giant 2012 Taschen book, left; as in the Neue Galerie’s, 2008 Gustav Klimt: The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabasky Collections, Ed. Renée Price, where a modern colour photograph of the painting has been superimposed, centre; and right, top and centre, as in Christian M. Nebehay’s, 1976 Gustav Klimt; bottom right, Sonja Knips as published respectively in Weidinger, 2007, and Natter 2012.

Natter and Weidinger both carry historic photographs showing Klimt paintings in the background but without comment on their then appearances. The Nebehay image above, right and centre, is small and printed on poor paper but even at this level of reproduction, it gives indication of the picture’s tonal hierarchies and dispositions – the subject is brilliantly lit on the left and moves into shadow on the right of the picture.

Klimt’s paintings were much photographed in his lifetime (that is, before his death in 1918), many were seen in their exhibited environments, some were photographed before being first exhibited and then again after subsequent reworking. For all this, and even though both 1898 portraits at Fig. 4, top, have exceptionally long and secure photo-histories, their narratives have been written without regard to such evidence and in terms of constituting steps towards subsequent pictorial developments – which progressivist schema happens to provide perfect art historical cover for dramatically altered pictures.

Of the Portrait of Sonja Knips, Dr Natter summarises: “This graceful female portrait marks a turning point in Klimt’s portraiture and is rightly considered a prelude to his Secessionist works. The sitter is portrayed in life size, seated in an outdoor setting. The square format is new and represents a fundamental choice whose possibilities Klimt would explore over the next few years. New, too, is the corresponding juxtaposition of light and dark, foreground and background, fullness and void.” That account was more consistent with the picture’s 2012 published appearance, Fig. 4, top right, than when first recorded as at, Fig, 4, bottom right, where today’s “void” comprised distinctly articulated spaces, forms and, even, mini-figures.

Of the painterly means, Natter adds: “Klimt employs a differentiated manner of painting, executing some areas of the portrait in a cursory fashion while focussing with great precision upon others. He thereby creates a fascinating contrast between the naturalistically modelled head of the sitter and the gauzy shimmer of her dress. This latter conceals a wealth of painterly effects and is infused with a rustling tension by a cascade of multiple parallel brushstrokes. Klimt at the same time camouflages the highly artificial nature of the arrangement as a snapshot.” In terms of a perceived stylistic dichotomy no mention is made of the picture’s former second carefully composed and precisely, naturalistically realised component – the now transformed and deranged small red sketchbook, as seen at Figs. 1 and 2.

AN AFFAIR – OR NOT?

With Klimt and his female subjects there is always a relationship issue and with this picture scholarly differences have arisen. Natter is agnostic: “Whether – as some suspect – Klimt and Sonja Knips enjoyed an intimate relationship, cannot be verified. But it is certainly the case that the painter presented her with one of his sketchbooks as a token of his particular affection.” He first speculates: “Whether he indeed pressed one such red leather-bound book into her hand during a sitting, because he felt the painting needed an accent of colour at that point remains conjecture”. (The reported source for this formalist reading had been the subject herself, as discussed below.) Natter takes the fact that such a scenario is conceivable to be “a clear reminder that Klimt, unlike the expressionists, continued to legitimize internal compositional requirements by cloaking them in external motifs.” Thus, a key question is begged: Whatever the relationship between the artist and the sitter, the book served an essentially formal pictorial purpose – the pink dress had “needed” on chromatic/pictorial grounds to be offset by a small red parallelogram of which just such an instance was conveniently to hand in a book of sketches Klimt had gifted to the picture’s beautiful subject whom he had known since her teenage years.

Thus was a formalist painterly purpose attributed to an immensely charged and fastidiously depicted small book, even after its – undiscussed – visually deranging transformation into the quasi-Cubist construct at Figs. 1 and 2.

TWO SCHOLARLY TAKES ON THE TWO PORTRAITS

Above, Fig. 12: Top left, the infra-red image of the Sonja Knips portrait published by Weidinger in 2007; top right, the second oldest (1908-1914) photo-record of the painting; below, Klimt’s 1896 Girl in the Foliage as published, left, in Emil Pirchan’s 1942 Gustav Klimt, centre, in Johannes Dobai’s 1978 Klimt, and, right, by Weidinger in 2007.

Weidinger situates the Sonja Knips portrait in the same part of the oeuvre’s developmental arc but also within social artistic and fashion contexts:

“This portrait is considered a turning point in Klimt’s portrait painting…the beginning of a series of large format portraits of ladies, predominantly of the prosperous, Viennese upper-middle class…and their wish for prestigious portrayal…[Knips] was one of his few models from the circles of – albeit minor – nobility…Klimt portrayed Sonja Knips sitting in a chair. A portrait formula he had already tried out in small-format portraits of ladies of 1896-98. The diagonal division of the painting into two zones places the subject opposite an empty space in tones of dark brown – a motif also used in Whistler’s Arrangement of Grey and Black No 1: Portrait of the artist’s mother (1867-71) and already taken up by Klimt in his Lady in an Armchair (cat. 106) and Lady by the Fireplace (cat. 106)…”

While the social/professional account of Klimt’s developing career is of interest, the perceived dichotomy of subject and void better accords with the picture’s present appearance than that seen in the special reproduction of 1908-14 (Fig. 4, right). Weidinger’s “empty space” had been closer than Natter’s “void” to the picture’s original and distinctly articulated spaces and forms but, then, he brushed away all claims that Klimt had originally “painted figures, a pool, or even a horse in the background which he then overpainted” on the grounds that no figural elements can be identified in the infra-red image. Thus, the testimony of a single undated technically penetrating image trumps all the compendious photo-records that testify to the contrary.

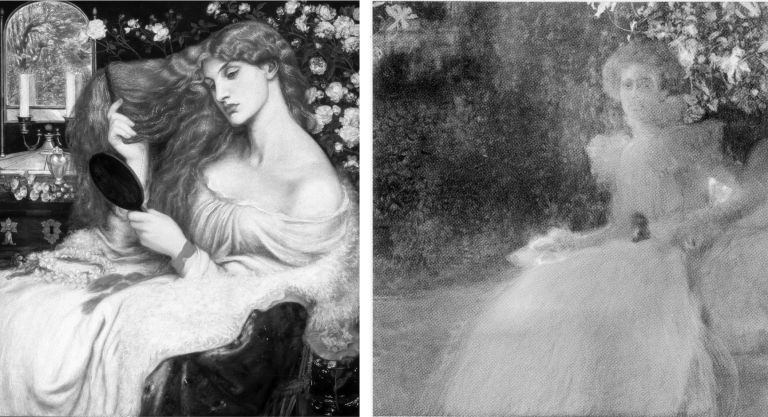

Above Fig. 13: Left, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1868 Lady Lilith; right, the undated infra-red image of the Sonja Knips portrait made – presumably – at the Belvedere, Vienna.

In lieu of an evaluation of the infra-red image in the context of the picture’s full photo-history, Weidinger pursues stylistic antecedents and influences: “The all-over brushstrokes suggest a landscape of bushes and trees such as Klimt had already once depicted in his Girl in the Foliage”, as above Fig. 12. Further, “In the upper left-hand corner of the picture there is a recognisable view, accentuated by a flower. Since Sonja is presumably in a garden, as suggested by the lilies above her head, this may be a view of the landscape, similar to Rossetti”. (In the Rossetti above, the landscape view is a reflection in a framed mirror.)

Above, Fig. 14: Above, Rossetti and Klimt details; centre, details, of Klimt’s Sonja Knips and Emilie Flöge portraits before restorations; below, Klimt’s Two Girls with Oleander.

Notwithstanding his reading of the infra-red testimony on foliage, Weidinger adds: “Admittedly, it is also possible that the setting is an interior room.” The picture’s present void may thus be read either as an ex-interior or an ex-garden or even a landscape – but which and how to decide? While the lilies above Sonja’s head might have been made in homage to Rossetti’s roses, in terms of Klimt’s stylistic development, they might also be considered to have anticipated his first placement of a decorative foil behind a portrait, which scholars have located in Klimt’s slightly later and more abstracted 1902 portrait of Emilie Flöge, as above, centre right. At the same time, Klimt might have been nodding back to his recent self’s 1890-92 counterpointing of closely adjacent flowers and young female subjects in the Wadsworth, Connecticut Two Girls with Oleander (as above, bottom) – which picture Weidinger nicely pairs with Alma Tadema’s deep-spaced 1893 Unconscious Rivals, at Bristol City Museum.

KLIMT’S CROPPING DEVICE

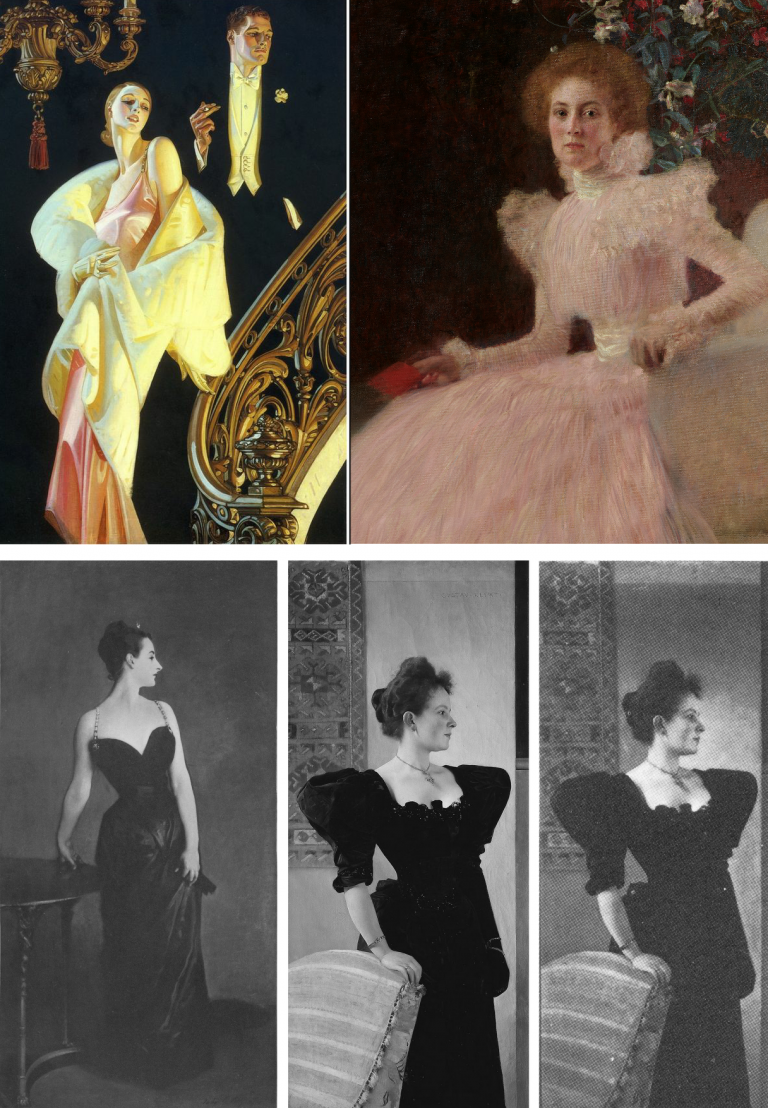

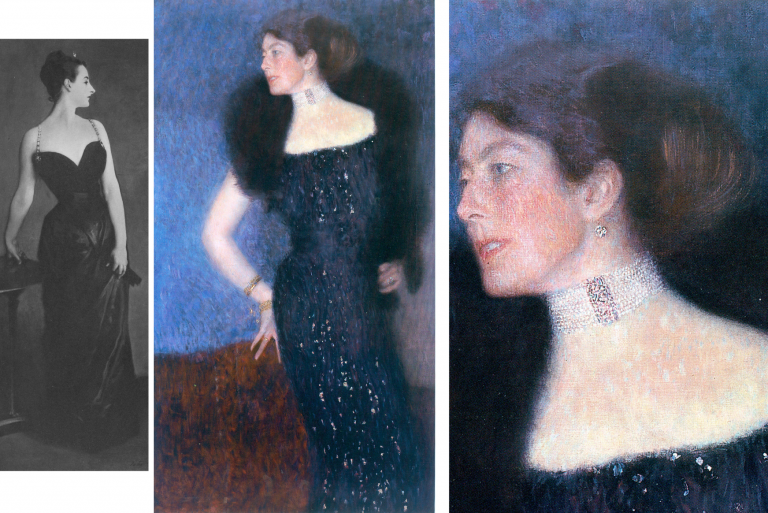

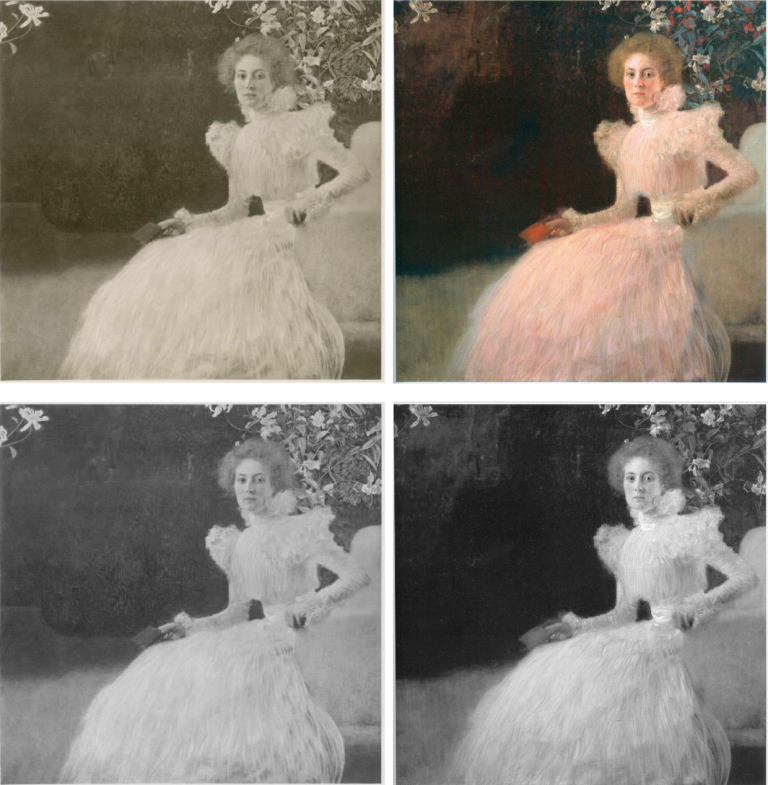

Above, Fig. 15: Top, left, J. C. Leyendeker, Couple Descending a Staircase, c. 1925; right a detail of Klimt’s Sonja Knips portrait; above, left, John Singer Sargent’s 1884 sensation-generating “Madame X”; centre, Klimt’s c.1894 Portrait of a Lady in Black as seen today; right, Klimt’s Lady in Black as shown in 1978.

Sonja Knips is shown wearing an elaborate evening dress and seated in a softly upholstered armchair. Her and the chair’s images are cropped by the bottom and right-hand edges of the picture and therefore are brought closer to the viewer while left without a clear relationship to a ground plane. Such cropping facilitates key modernist picture plane-asserting strategies – as evident in the above Sargent and Klimt portraits of a standing lady in a black costume. Sargent sets the whole figure in a dark enveloping but bounded space. The fused figure and (vertically, not horizontally, cropped) table are as securely placed on the floor as a linked piece of sculpture on a plinth. Adding to that palpable sense of the body, Sargent’s light picks up form-disclosing drapery configurations within the dress’s overall blackness. That mix of a theatrically lit figure and minimal but precisely realised furniture may have found echo in the American illustrator J. C. Leyendecker’s brilliant advertisement for Arrow Shirts (above, top left).

With the cropped chair and figure in Klimt’s lady-in-black, above centre, we are given fewer such lights and altogether less spatial orientation – except in narrow overlapping recessional relief: the chair overlaps the lady, who overlaps the hanging carpet and the wall, which overlaps a second parallel wall. While such treatment can be read as a staging post in a long march towards modernism, Klimt had shown fondness for precisely such compositional parallelisms and eschewing of deep spaces at the height of his neo-classical “historicist” period, as recapitulated in his Young Girls with Oleander at Fig. 14 above.

In any event, whether a recapitulation or an anticipation, in his lady-in-black, the emphatically extravagant shapes of the black dress pin the subject to the picture plane like a butterfly to a board. Or, rather, they do so in the picture’s present restored and buffed state. Originally, and as late as in its 1978 appearance as above right (in Johannes Dobai’s Klimt) when much of Klimt’s complex and nuanced hierarchy of values survived, the lighting was not uniformly bright but softer and more focussed, in a more Sargent-like theatrically light-animated space. Then, the décolleté was rendered both more brilliant and more plastic by adjacent as well as internal tonal values. A darker tone at the back of the neck/shoulder in combination with the more shadowed profile face and shoulder (offset by a spotlighted halo) bestowed a more columnar, sculptural neck.

Klimt was then disposing lights and shades imbibed from his classical training like a masterly cinematographer with his lamps. The great British cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, learnt his lighting in childhood from studying old masters in museums and his lighting was so skilful and flattering that great actresses of a certain age would only appear in films employing him. (One of Klimt’s sons, Gustav Ucicky, began a distinguished filmmaking career as a camera man in 1916, as Nebehay discussed in his 1992 Gustav Klimt: From Drawing to Painting.)

THE FULL PHOTO-RECORD

Weidinger’s inclusion of the Belvedere infra-red image raised awkward methodological questions. With a century old painting, can a “below-the-surface” view reliably locate a work’s original appearance? If infra-reds are admissible evidence, what grounds exist for excluding the testimony of all other photographic records?

Above, Fig. 16: Top, Klimt’s Helene and Sonja portraits, as published between 1908-14 through the H. O. Miethke gallery in Vienna; and (above), the portraits as published in 1942 and 1956 in Emil Pirchan’s Gustav Klimt.

In Klimt’s portrait of Sonja Knips, the group of lilies shown above and close behind her head must be presumed to be either cut flowers in a hidden vase or some free-floating artistic/symbolic device. Presently (as at Fig. 11, bottom right), the subject herself aside, all is indeed darkly mysterious and serves effectively as a backdrop/foil to the brightly lit head and spectacular dress – almost as in Leyendecker (Fig. 15, top left) when the early photo-record shows Sonja set in an articulated and bounded space.

In 1908, Klimt and Galerie Miethke had collaborated on the publication of a group of collotypes marketed under the name Das Werk Gustav Klimts, a project aimed to distribute his work to a new type of collector. From 1908 to 1914, Klimt personally supervised the 50-print enterprise, which faithfully reproduced what he thought to be his most important paintings from 1898 to 1913 and he designed a unique signet for each print, which was placed beneath the image and impressed in gold ink. Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria was the first to own the initial instalment.

Where some might sniff at the enterprise’s commercialism, Weidinger reminded us (2008, the Tate, “The master of erotic theatre” ) that: “Contrary to what people think and what has been written about the Secession, it was not a museum, but a gallery operation that generated cash. The artists had families and needed the money.” In the event, those limited edition ultra-high quality photographic reproductions generated a niche market as quasi-artworks. (See, for example, 1stDibs; Acquisitions of Fine Art and the Jason Jacques Gallery.)

If the art historical testimony of these images remains neglected, their role in the withdrawal of the Klimt group of artists from the Secession was reported in Nebehay, 1992:

“In the spring of 1905, after a difference of opinion regarding Carl Moll’s activities in the then leading gallery H. O. Miethke, the ‘Klimt group’ had left the Secession. This group, which comprised apart from Klimt, architects such as Josef Hoffmann and Otto Wagner and artisans such as Kolo Moser, was opposed by the so-called painter group, led by Jose Engelhart, who protested against Moll’s exhibition activities at Miethke’s which, they said (not without reason) were damaging to the Secession. When it came to a ballot, the opponents – having roped in one of their members then staying in Berlin – won by only one vote. Again, the real talents gathered around Klimt: the rest were mediocre. The eight wonderful years of the Vienna Art Spring were over: after the ‘Ver Sacrum’ came no mild summer, no fruitful autumn, no contemplative winter.”

A MOST ADVANCED METHOD OF PHOTOGRAPHIC REPRODUCTION

The following technically informative account of the role of the originally created portfolio of ten Klimt works is given by 1stDibs:

“…the folios of collotype prints published by H.O. Miethke in Vienna between 1908-1914 known as Das Werk Gustav Klimts, are important art documents worthy of as much consideration for the bold stand they take on established ways of thinking about artistic collaboration as they are for their breathtakingly striking images…Miethke’s pioneering art house had become Klimt’s exclusive art dealer and main promoter of his modernist vision. Paul Bacher and Carl Moll, a founding member with Klimt of the Vienna Secession, who all broke away during the rift in 1905, took stewardship of the gallery following the fallout with the Secession. Das Werk Gustav Klimts is a prime example of Miethke’s masterful and revolutionary approach to marketing art. Miethke’s innovative marketing strategy played to a penchant for exclusivity. The art gallery and publishing house utilized the press and art critics – such as Austria’s preeminent Art Historian, Hugo Haberfield, who became Director of the gallery in 1912 – as a means of gaining publicity as well as maintaining effective public relations. Miethke used the grand exposition format to extend the art gallery’s market reach, cultivating their product’s prestige by stroking the egos of current art patrons while simultaneously creating accessibility for newcomers and other avid collectors to share a relative proximity to other wealthy and respected members of the art collecting community… Between 1908 and 1914, H.O. Miethke published a total of 5 instalments of print folios of Klimt’s painted work, each comprising 10 prints. The series was limited in availability to 300 and purchase was arranged through subscription. Each issue was presented unbound in a gold embossed black paper folder…These folios were not comprehensive of Klimt’s work; but rather, they feature what he believed were his most important paintings from 1898-1913. Only 2 collotypes in each folio were multicolored…Alice Strobl’s scholarship on this subject confirms Klimt’s involvement throughout the 7-year production process. The Virgin, for example, which dates from c. 1912-1913, was created well after the portfolio was first conceived c. 1908. Its corresponding signet, therefore, could not have been created a priori [see Fig. 17 below] … Understanding the fragile nature of the collotype printing process also reinforces this project’s distinctive and ground-breaking characteristics. The fragile collotype plates could not be reused. As such, this necessitated the completion of a run on the first go and also dictated the limited production numbers such as the 300 pulled for Klimt’s Das Werk. Printed by hand, the collotypes required deft handling by the printer, k.k..Hof-und Staatsdruckerei. A complicated and lengthy process involving gelatin colloids mixed with dichromates, the creation of 16 color separation thin glass filters to achieve the light-sensitive internegative images which could faithfully capture all of the painting’s tonal gradations and colors, exposure to actinic light, and delicate chine collie papers which allowed for greater color saturation, the printer’s collaborative role in capturing and transmitting Klimt’s nuanced paint strokes is nothing short of remarkable. Ernst Ganglbauer, Director of kaiserlich-konigliche Hof-und Staatsdruckerei (1901-1917) was eager to promote art prints. An innovator, he elevated the Kaiser’s press to international renown by assembling the best of the best in technical and aesthetic advisors. This dream team of free-lance artists developed adaptive uses for the Staatsdruckerei’s existing equipment and, together with the printers there, perfected the multicolor print process for Miethke and Klimt’s Das Werk.

(Emphases added.)

Clearly, these early Klimt-approved images were as good as could be made at the time and might properly form the starting point for any comparative study of the two pictures’ photo-records. Their then technological sophistication was truly remarkable: in key respects, the multiple colour separations made to capture the exact tones and hues anticipated by a century the ground-breaking multi-spectral high-definition digital camera invented by the engineer/optician Pascal Cotte of Lumiere Technology.)

Other collotypes made and produced in limited-edition books today sell at eye-watering prices. In 1942 and again in 1956 the two portraits (along with many others) were published in Emil Pirchan’s book Gustav Klimt, as above at Fig. 16.

PHOTOGRAPHIC DEMONSTRATIONS OF RESTORATION INJURIES

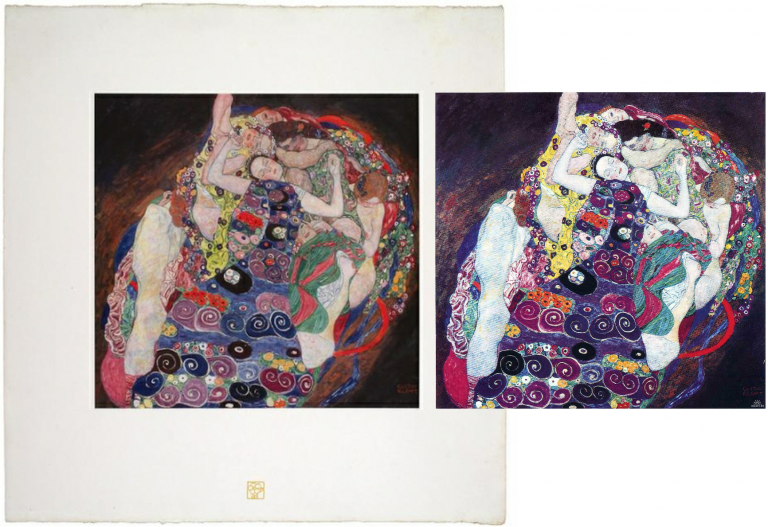

Above, Fig. 17: Left, a collotype print of Klimt’s The Virgin published between 1908-14 through the H. O. Miethke gallery in Vienna, here overlapped by its Wiki image. The chromatic and tonal differences between the two records speak for themselves.

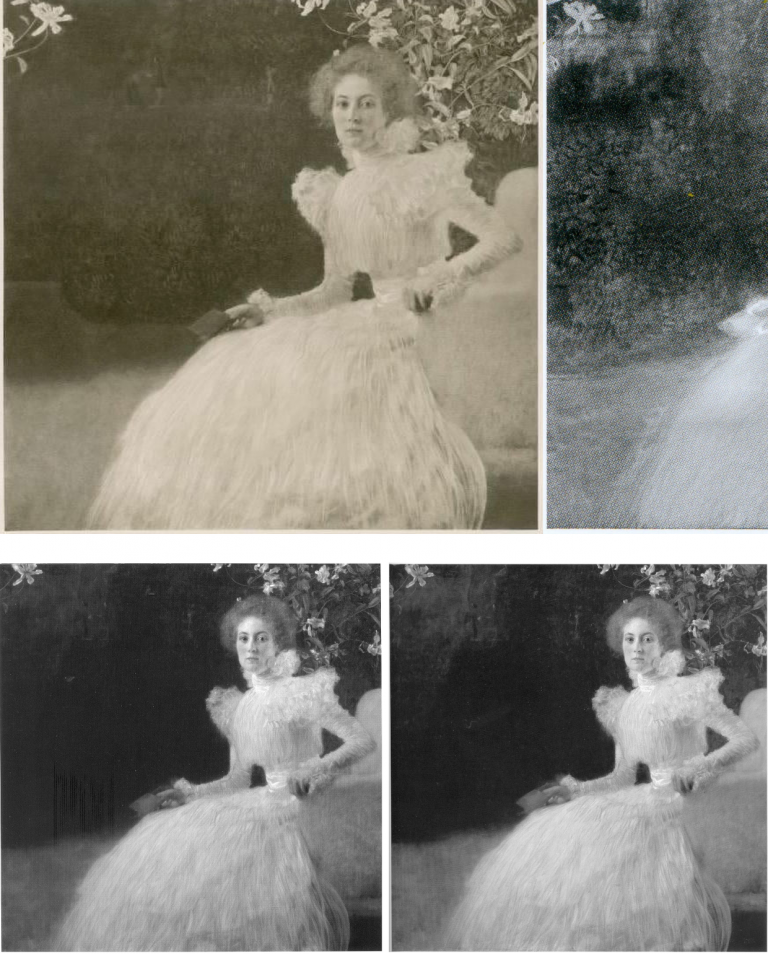

Above, Fig. 18: Top left, Klimt’s Sonja Knips portrait (a Miethke 1908-14 collotype); right, the left section of the Belvedere infra-red image published by Weidinger in 2007. Above left, the portrait as in 2007 and, above right, in 2012.

The above comparison of the testimony of the 1908-14 photo-record and the pre-2007 infra-red image, suggests that formalist accounts of a light v. dark triangular pictorial dualism are over-stated, space-denying simplifications. Note that almost half-way up the photo-record’s left-hand edge, the picture is bisected by a short horizontal tonal division between a darker upper area and a less dark, seemingly shadowed area of ground. That crisp horizontal division speaks not of a void but of a distinction between a wall and a ground plane. Such an architectural reading is further indicated in the top left-hand corner of the infra-red image by a seeming bottom corner of a window or aperture. On the combined evidence of the Klimt-approved Miethke collotype and the Weidinger infra-red image we can conclude – much as with the Helene portrait – that Klimt had toyed with the idea of inserting an implicit rectangular feature (a fragment of a window, or aperture) in the picture’s top left-hand corner which would have echoed the picture plane but that he had decided against it and painted it out. Having painted out the feature, Klimt then pulled that corner of the picture back towards the picture plane with the “echoing” parallelism of the flowers’ motif. (Had the superimposed fragmentary flowers not been in place, the restorers might well have semi-excavated the window aperture as with the frame behind Helene.)

With further regard to the Klimt-approved Miethke-recorded spaces and structures, if we read leftwards from the centre of Klimt’s strategically placed little red book, another tonal division runs horizontally before turning upwards diagonally to meet (almost) that of the wall/floor junction running in from the left edge. Above this lower division there are leaf-like formations that suggest a shrub or topiary that runs upwards and behind the lilies. However, on the infra-red image detail, above right, the leaf-like formations also run below the book and into the area that had read in 1908-14 as the shadowed section of the floor. That would indicate that Klimt had painted out the lower leaf-like forms to produce the ground plane as recorded in the Miethke gallery collotype. Today, as seen above in 2007 and 2012 (Fig. 18), the originally distinct tonal zones have been subsumed in the larger, undifferentiated dark zone that is now taken as a Klimt-intended emptiness or void. However, even today, within this supposed void, a seeming tableau of small figures and statuary can still be glimpsed despite having been ruled out on the supposed evidence of the sole infra-red image.

FIGURES IN THE BUSHES OF A TRULY EXCEPTIONAL PICTURE

In her 1989 Klimt, Life and Work, Susanna Partsch wrote of the Knips portrait:

“Sonja Knips is sitting in a park or garden, on the edge of a light-coloured chair…The light earth contrasts with the dark background, which has some red in it on the left. There is something mysterious about the dark, irregularly applied colour, which casts shadows on the light earth. There is the merest suggestion of a pond in the background. Against this background Sonja Knips sits in a sumptuous pink dress with high neck and ruffles, narrow waist and full skirt. The lower edge of the picture cuts off the bottom of the skirt, which is therefore not visible, any more than are the feet. With her left hand, Sonja Knips grips the armrest, as if she were just about to get up, and this impression is strengthened by the way she sits on the edge of the chair but is contradicted by her right hand, which rests quietly on her leg clasping a red booklet. Nor does the expression on her face suggest that she is about to move, she gazes straight ahead out of the picture, disquieting in her immobility. This portrait is the only one with a hint of landscape in the background. Klimt painted many landscapes and many people but kept the two distinct, which makes this portrait truly exceptional. It was painted at a time of upheaval, when Klimt had abandoned historicism but not yet found his own style. In the same year he painted his first landscape pictures. The orchids and the pond in the portrait represent a subdued symbolism, hinting at sumptuousness and mystery.”

That nicely observed account presumably preceded the picture’s restoration. Twenty-three years later in her 2012 Taschen essay “Paintings of women” Dr Partsch writes of the same picture:

“…She is sitting at the very front of the seat of a generously sized armchair and is leaning on the upholstered arm as if she were about to stand up. In her right hand she holds a small red book. With her body angled to the left, she has turned her head so that she is looking straight out the picture and fixes the viewer with her gaze. The curls of her hair are taken up in the ruffles of her dress, while her head is framed as a whole by a backdrop of flowers – lilies or orchids that are either growing in a garden or standing in a large vase on the floor. Beyond the top of the canvas, blooms and branches form an invisible arch that descends into the picture in the top left-hand corner in the shape of another flower. This left half of the picture consists of two planes clearly divided by their colour. The [lower] area of pale brown, in some places shot with green, in the lower left-hand corner barely distinguishes itself from the tender pink dress and forms a floor of some kind. The dominant field of blackish brown, which provides a foil to the flowers and the female sitter, contains several lighter patches. These have inspired numerous interpretations, with some authors suggesting that Klimt had painted over what was originally a garden setting. Infra-red photography has failed to confirm this theory and it thus remains unclear whether Sonja Knips is situated in a room or outdoors in a garden…”

The two accounts of the same picture by the same author differ – but what has changed if not the picture itself? A certain hardening of a feminist stance emerges. Sonja is now more assertively “looking straight out the picture” and “fixes the viewer with her gaze”. Partsch now complains generally that Klimt’s portraits of women “seldom reveal the individuality, character or abilities of the women they depict” and raps him over the knuckles for having reduced one female subject, his Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann of 1901, “to a figure of elegance and sensualism” while neglecting to indicate that “she was a pioneering female alpinist who became the first woman to climb the East Face of Watzmann and Thurwieserspitze in the Ortler Alps”. The complaint seems something of an ideology-signalling contrivance: short of tying some rope, climbing boots and crampons around his subject’s neck, it is hard to see how Klimt might better have done justice to her than as below at Figs. 19 to 21.

A digression is merited on this female portrait: the charge of “reducing” his subject to elegance and sensualism – as if those two traits preclude all others – is unfounded. Klimt, who said of Alma Schindler “She is beautiful, she is clever and witty, she has everything that a fastidious man can expect from a woman”, did not rob the subjects of his commissioned female portraits of dignity, gravity or intelligence, any eroticising tendencies notwithstanding – and nor was he formulaic in his portrayals: every subject prompted a re-invention, and a re-invention that was preceded by multiple exploratory studies. Natter’s close attention to the receptions initially given to Klimt’s paintings is pertinent on Rosthorn-Friedmann: “her death, still relatively young, on 19 January 1919, prompted Hugo von Hoffmannsthal to write a letter to her widowed husband, in which he emphasized the striking beauty, intelligence and warmth of this exceptional woman.”

Above, Fig. 19: Left, Sargent’s “Madame X”; right, Klimt’s portrait of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann, as in Natter, et al, 2012.

In Rosthorn-Friedmann Klimt fused glamour athleticism and grit, if not steel (note the eyes; the pinched nostrils; the mouth and its bared teeth); not to mention the sinuous lightness of a delicately perched and coiled figure whose torsion more than vies with that of Sargent’s “Madame X”. With what is known of his subject, all would seem to be in order in Klimt’s painted account. Partsch casts doubt on Alma Schindler’s claim that Klimt had just begun an affair with his model, but Natter spells it out: “In her diary entry of 19 January 1900, Alma mentioned Klimt’s latest liaison: ‘What’s more, he’s just started an affair with Rose Friedmann, that old hag! He takes where he finds.”

Above, Fig. 20: Klimt’s 1901 portrait of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann as seen in the two deluxe Klimt catalogues: that is, as in Weidinger, 2007 left; and as in Natter, 2012, right.

We cannot vouch for the veracity of the two books’ reproductions of the painting and both publishers take fair pride in their productions. Yet, as seen above, there are numerous chromatic and tonal differences in the respective photo-illustrations which, given the chronology, suggest a post-2007 restoration. Because Weidinger attempted to have every Klimt work re-photographed for the 2007 Prestel book’s catalogue we can, perhaps, safely take the images above left to be a fair record of the then state of the picture. So what might account for the general losses of tonal and chromatic vivacity as seen on the right in 2012? For example, Partsch notes (Taschen, 2012) that “her dark, coiffured hair is barely distinguishable from the blue of the background”. That indeed was the case, but it had not been so in the 2007 Weidinger reproduction as above left, centre, when the blues, blacks and whites were warmed and enriched by red. The evident weakening of the strong form and shape of the greatly more lustrous hair in 2007 is not an isolated incident within the picture. It had been accompanied in 2007 by a markedly sharper, darkly unified near-diamond shape of background enclosed by the arm and body.

WHICH IS THE REAL KLIMT?

Above, Fig. 21: Left, Klimt’s working drawing for the Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann portrait (which picture is held in a private collection in Switzerland); right, a detail of the painting, as reproduced respectively in: 1988, Gabriella Belli, Gustav Klimt Masterpieces; 2007, Weidinger, et al; and in 2012, Natter, et al.

The picture had long been thought lost and was known only by a single photograph. Unfortunately, no one seems to have reproduced that early record. What is to be made of the above trio of details recorded consecutively in just twenty-four years? With the above detail, we see three successive states: 1988; 2007; 2012. With the second and third – which is to say, the two most recent states – we can dismiss the possibility of photo/reproduction variations because such could not be responsible for distinctly local changes, as with the dramatically and selectively darkened space between the little and the ring finger that occurred between 2007 and 2012. All three images are individually of a piece and speak of distinct appearances in the picture. Of the three states, the first (1988) is the one that is least like the others: its arm has two sharply defined contours and is slimmer than those in the other two photographs. To this photo-testimony, might anything be gleaned from what is known and what has been said about the picture?

Writing on the most recent (2012) state Natter speaks first of its reception and then of Klimt’s initial struggle: “Klimt wrestled long and hard with the composition and the standing motif, as his preliminary drawings testify… Only gradually did he arrive at the curvaceous, serpentine pose of the final portrait… Noteworthy is the dialogue between the figure and background…Such a permeability of natural forms and representations of the human figure is therefore thoroughly typical of Klimt…” (Emphasis added.)

Writing on the 2007 state, centre image above, Weidinger related the picture’s “erotic connotations” to Klimt’s “numerous snaky women who populate the symbolist paintings of 1898 to 1907” and held that, in this portrait, Klimt “emphasizes both line and area so as to produce a stylized rendering of the body such as manifested itself first in his Symbolist works…Instead of twisting three-dimensionally around her own axis, as do Mannerist figures [and Sargent’s “Madame X”] Rose von Rosthorn’s S-shaped body appears to be all on the same plane; the effect of this, coupled with the emphatic outlining, is to make the portrait seem curiously flat.”

There is a crucial difference in the two accounts. Where Natter speaks of the permeability evident in a dialogue between the figure and its background, he seems on safe ground with the borders of the extravagant fur stole and the lower body on the right, and with the division between the background and the assumed reddish chair, but there is no such permeability at the contour of the face and choker, or at the scissors-like fingers and chair back. Weidinger notes that the red of the armchair had been achieved with “the application of innumerable tiny brushstrokes, pointing in all directions at once” and that “the same method is used for the skin, although here the outcome is not so coarse”. The key difference in the two accounts lies in Weidinger’s recognition of Klimt’s deployment of both line and area. The line (which bounds impermeable shapes) is confined to the areas of bare flesh – the head neck and arm – where Klimt’s classically trained draughtsmanship asserts itself. In his commissioned portraits Klimt retained a respectful and more traditionally hierarchical attentiveness to the forms of heads and hands, whatever indulgence might have been given elsewhere to symbolism, pattern-making abstractions, and decorations.

The earliest photograph, above left is, by definition, the record that is temporally closest to the picture’s original appearance and it should, accordingly, be taken as a more reliable record than the two later states. Additionally, this 1988 state better accords with a vivid contemporary response to the painting. In contradiction of the present (post-2012) chilled blue background, Natter cites Frans Servaes’ captivation in 1901 with Klimt’s use of colour: “The shimmering violet of the background plays with tumultuous gentleness around the bare propped arm and the dark dress covered with spangles in the most wonderful fashion.” Today, one sees no violet against the arm in Figs. 19 and 20. A patch of background to the right of the dress might be thought of as violet but the larger cooler blue areas certainly could not. Might there have been earlier losses in the background as with those seen more recently in the hair? Natter also mentions that Ludwig Hevesi had been particularly struck by “Slender elastic lines having a singular swing, profile to the left…A slim pale arm supports itself on three fingertips on a piece of furniture; one realizes immediately that a figure such as this really does not need to support itself” – like that of an agile, super-fit rock climber, perhaps? Klimt’s final, working study, above left, had fixed the slim arm’s outer contour with deftness and precision. Such decisiveness of design in the arm is best seen here in the oldest record (1988) and is least evident in the most recent and most fumbled arm (2012) where the contours have succumbed to a havering state of permeability. To discount the 1988 photo-testimony in favour of the later states it would be necessary to claim that an earlier restorer had wrongly imposed an alien linearity on the arm and that in two successive restorations an original, fumbled and fatter arm had been recovered. The non-publication of the sole photograph by which this once lost painting was known is to be regretted.

VOID SPACE OR INTRIGUE?

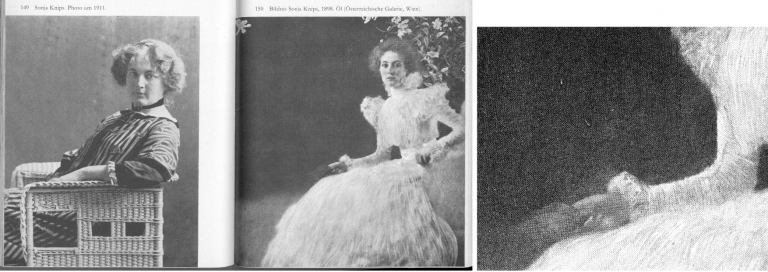

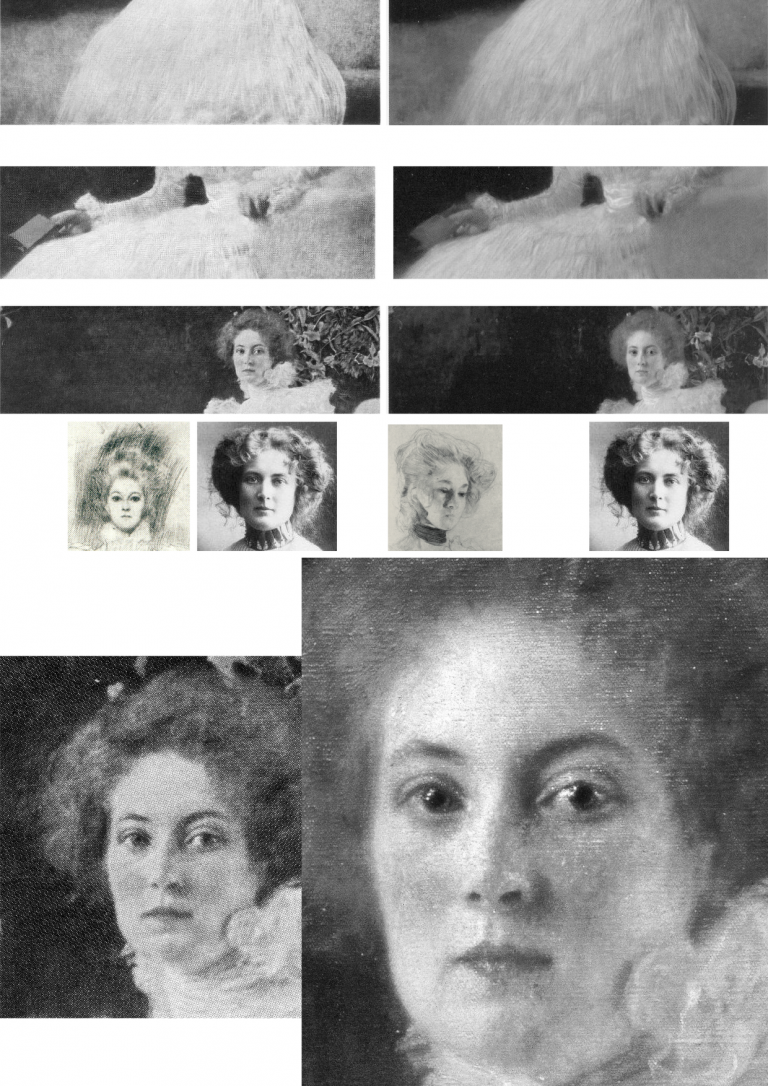

To return to the Knips portrait, in both Figs. 16 above and 22 below it is possible to read miniature figures or statuary within the vegetation along a horizontal line to the left of Sonja Knips’ forehead.

Above, Fig. 22: Left, the 1908-14 collotype of Sonja Knips; right, a lightened section of the collotype’s left-hand area, in which the original two-tone ground/wall/shrubbery boundary is clearer. The above greyscale inset is a detail of a photograph carried in the October 1900 Figaro Illustré, as discussed by Emily Braun in the 2001 Gustav Klimt Modernism in the Making, Ed. Colin B. Bailey. In all three images the horizontal line of figures and a statue is discernible.

Above, Fig. 23: Top row, left, the 2007 Weidinger infra-red image; right, the 1908-14 Miethke collotype – in these, we indicate (in red) the moving ground/wall boundaries and the placement of the “window”. Below, in the centre group, we see how the reported figures had appeared in early photographs. In his 2007 rejection of earlier claims of perceptible figures in the picture’s upper half on the testimony of the infra-red image, Weidinger cites scholarly experts who had variously identified: “cupids and two figures…[a] pool and fish-like creatures… [and a] horse’s head…” Given such testimony – and the fact that discernible figures had registered in the dark background to the left of Sonja’s head in the Klimt-approved collotype and subsequent photographs to this day, as in Fig. 24, right below – those figures’ status might better have been resolved by the publication at high resolution of all the Belvedere’s photographs and technical records of the picture rather than with a dismissal by technical fiat on a single, out-of-context, difficult-to-read infra-red image.

The small, photographed free-standing Cupid sculpture in the centre group above is the former antiques shop find that has been upgraded and displayed at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, as an autograph early Michelangelo. If it might seem improbable that Klimt should have included secondary figures in a large and exceptional portrait, it could equally be held that the photographically-recorded figures in question were forerunners of the artist’s later incorporations of entire armies of people and horse riders – as in the above three later portraits of The Dancer (1916-17), left; Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912), top; and Elisabeth Lederer (1914-16) bottom right.

Above, Fig. 24: The Portrait of Sonja Knips, as in 1908-14, left, and today, right, as seen in both colour and in greyscale.

THE DEMISE OF THE LILIES AND THE RISE OF “APPROPRIATE RESTORATION STRATEGIES” AT THE BELVEDERE

Above, Fig. 25: Three details of the lilies backdrop as recorded in: 1908-14, left; 1942-56, centre; today, right. In the inset, above right, a 1912 British Vogue fashion shot.

The differences seen above between 1908-14, left, and 1942-56, centre, are not substantial and might amount to little more than variations in reproduction values. The subsequent differences seen above, right, however, are of another magnitude and show outright losses of autograph material, as to the foliage between the upper arm and the back of the chair.

Above, Fig. 26: Left and centre, a two-page spread from Christian Nebehay’s 1969 Gustav Klimt, showing Sonia Knips in 2011 and her portrait when the hand/notebook motif was still intact; right, a detail from Johannes Dobai’s 1978 Klimt showing that by that date the hand/book had been injured and left incoherent. The offending restoration must, therefore, have taken place between 1969 and 1978. The picture itself was commissioned by Sonja Knips (1873-1959) and owned by her until 1950 when she was seventy-seven and it was bought by the Belvedere, Vienna. The museum says of its (manifestly hyperactive) conservation department:

“The Belvedere’s restoration and conservation department is dedicated to the preservation and care, restoration, and technological research into the art and cultural assets of the Belvedere’s collection, which ranges from the Middle Ages to contemporary art. Its mission is to record and preserve objects of historical and cultural significance. Conserving these irreplaceable originals requires a methodical and scientific approach in order to shed light on the historical, stylistic, iconographical, technological, and material aspects of the artworks. With this in mind, the Belvedere’s conservators devise appropriate strategies. On average, the department conserves and restores 150 paintings and frames each year, and frames and mounts between 100 and 150 graphic works.”

THE DECONSTRUCTION OF SONJA’S LITTLE RED BOOK

Above, Fig.27: The red leather-bound Klimt sketch book held by Sonja Knips, as seen, respectively in 1908-14, top; in 1956, centre; and today, above.

In this photo-sequence we see that crucial differences of appearance arose between 1956 and 2012 – in fact, on above evidence, between 1956 and 2007. Given the book’s changed appearances, Dr Natter’s claim that “The dualism of mimesis and dissolution, of faithful reproduction and painterly openness, is already in evidence here as a stylistic means” becomes problematic. Given that the once faithfully tight and precise book/right-hand had by then been left in a quasi-Cubist double image that resembles time-lapse photography, should it have been regarded as an instance of mimesis or dissolution? Natter’s view remains unknown because has not commented on the present condition. Such questions arise with other Klimt portrait pictures:

Above Fig. 28: Top, left, Klimt’s now lost 1900 portrait of the thirteen-years old Trude Steine (note the strong line of the shoulders); centre and right, a large detail of Klimt’s 1902 Portrait of Gertrud Loew, as in 1956 and today; above, a three-part chronological sequence of Klimt’s 1905 Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein.

As a lost work, the Trudy Steine picture, will at least now never lose its great – photographically preserved – vivacity and force. Gertrud Loew disappeared when sent to Berlin in 1938. Her portrait survives but it has not been spared by restorers. Speaking to its condition today, as top right, Weidinger writes:

“Ludwig Hevesi [1902] referred to the portrait of Gertrud Loew – shown for the first time at the ‘Klimt Collective exhibition’ at the Secession in 1902 – as ‘the most fragrant lyric of which the painter’s palette is capable’. Like Serena Lederer the subject is clad in white. Colour accents are set by her long, downward cascading shawl with its lilac-coloured border. Klimt renders her pale skin in tones close to that of her dress, and only her red lips, blue eyes and dark hair supply the necessary contrasts. Her loosely flowing dress betrays no sense of corporeality. In this connection, Natter speaks of her ‘dematerialization’”. Weidinger adds that when exhibited in 1903 it had been said to possess “all the charm of radiant filminess” and “the gauziest lyricism of which the palette is capable.”

That was then. Restorers thought the filminess might be taken further and, to that end, simultaneously darkened the upper background and lightened the upper costume, thereby dematerializing the previously clear articulation of the subject’s shoulders. To add to the tonal mayhem, both the lower background and the lower dress have been lightened. This is no longer the picture Klimt painted of Loew. The Pirchan reproduction gives a truer account than the painting itself.

Above, Fig. 29: Main centre images: a detail of the picture as recorded in 1956 and today, in which sequence it is easy to identify the obliteration of leaves, multiple micro-losses of value in this dress and the loss/painting-over of the original foliage between the shoulder and the chair back; insets, a detail of one of Klimt’s preparatory studies for the painting; and (bottom left), a detail from a photograph of the portrait carried in the October 1900 Figaro Illustré (as discussed by Emily Braun in the 2001 Gustav Klimt Modernism in the Making, Ed. Colin B. Bailey).

Natter’s claim that Klimt camouflaged disparate pictorial means by simulating a photo snapshot holds fair insofar as Sonja grips the arm of chair firmly and (as others have noted) leans forward as if caught when about to rise, but the picture was no product of a snatched moment, as the many studies Klimt made of his subject when in costume and in the chair testify (see Fig. 30 below). It is also part-true that Klimt conjured a “fascinating contrast between the naturalistically modelled head of the sitter and the gauzy shimmer of her dress” (we are advised that the material was likely either very finely pleated silk chiffon or muslin) but, aside from the abundant skirt, there is no near-abandonment of corporeality: even in semi-repose this dress in animated and formed by the lithe, almost geometricized, body that was captured in Klimt’s preliminary studies.

Notwithstanding the abundance of small folds on the sleeves, the thin shapely taught-ness of the arm seen by Klimt and captured in the drawn studies had asserted itself in the painting. On comparing the above photographic sequence, it is evident that in the very earliest recorded state (1900, bottom left), the orchestrated collection of shadows at the bottom of the lower arm much better and more decisively “drew” the limb’s contour: at the turn of the sharply defined elbow there is first a discernible concavity and then a convexity that straightens as it runs down towards the wrist. That original taught-ness of form/anatomy and relative weight of shadow at the lower contour was also evident even in the small low-quality image from Nebehay’s, 1976 Gustav Klimt, shown above at Fig. 11, but, like so much in Klimt, it has subsequently been fuzzed and lost.

Above, Fig. 30: Some of Klimt’s many sketches for the Portrait of Sonja Knips, in every one of which the forms and the massing of the hair were noted in relation to the head.

Above, Fig. 31: Top, three photo-comparisons of details showing changes between 1956 and today; centre row, left, a drawing of Sonja Knips and a later photograph; right, a Klimt study for another painting; bottom row, Knips in 1956 and in 2007 (Weidinger).

More than a first foray into a new type, this arguably stands as one of Klimt’s best female portraits, its twenty-five years-old subject being utterly composed, beautiful, intelligent and with a resolute, if poignant gaze. As mentioned, having first seen Sonja to be gazing out of the picture, Susanna Partsch (“Paintings of Women”, Taschen, 2012) now sees a Gorgon-like demeanour with Sonja turning her head “so that she is looking out of the picture and fixes the viewer with her gaze”. That reading is not remiss on today’s appearance but in Pirchan’s 1956 image (here bottom left) the gaze seemed fractionally averted and the effect markedly more reflective than confrontational. Moreover, a comparison of the mouth’s two states shows that Sonja has received a fresh lipstick that no long conforms to the shapes and forms of her lips.

Partsch writes that “The curls of her hair are taken up in the ruffles of her dress” without noticing that the earlier softly disposed forms and luxuriance of the hair have been drained of form and vitality – as with the disappeared darkly accented shadow at the lower temple and cheek that formerly served to draw the contour of the face and drew attention to Knips’ right eye. Considering the importance of hair as a feminine adornment and how hard artists labour to do justice to its glories, it seems odd that clear injuries to it, as here and with Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann alike, should generally go unremarked.

Above, Fig. 32: Left, Sonja Knips in 1911; centre, top, Evelyn Nesbit, the muse of the American illustrator Dana Gibson, left, and one of Gibson’s famous “Gibson Girl” drawings; right, a Klimt drawing of 1898-1900; centre above, a Gibson Girl left and Sonja Knips in 1911 in Japanese-style Reformklied, as carried in the Neue Galerie 2007 Gustav Klimt. (For live early film footage of American women sporting Gibson Girl hairdos, see “The Real Edwardian Gibson Girls of the USA” at Glamour Daze.)

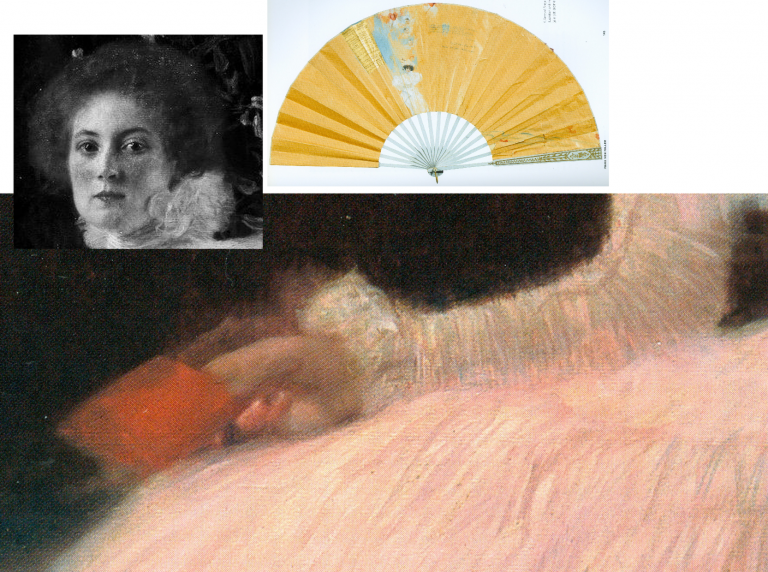

Above, Fig. 33: Main picture, the right hand of Sonja Knips; top left inset, Sonja Knips; above right, Sonja Knips’ fan, as decorated by Klimt.

Consensual views break down on Klimt’s and Sonja Knips’ relationship. In the 2007 Neue Galerie book, Knips’s granddaughter, Dr Manu von Miller, author of Sonja Knips Und Die Wiener Moderne, 2004, reports (“Embracing Modernism, Gustav Klimt and Sonja Knips”) that recently disclosed materials from the Knips family revealed much about Sonja and shed light on previously unknown aspects of Klimt’s life and person. Thus: Klimt’s Sonja portrait “likewise contains hints about the life of the artist” and that the two had had an affair years before it was painted, Klimt having known her since she was a teenager. Painting Sonja had released Klimt from his role as “a ‘decorative’ painter”, and he in turn enormously influenced Knips enabling her to “break free of the rigid bourgeois conventions of her time, and to create her own highly personal approach to aesthetics and collecting.” In 1896 Sonja married the industrial magnate Anton Knips – a mismatch, he not sharing her passions for socialising, modern art and young artists. Klimt’s relationship had, Dr Miller reported, “blossomed at some point into an amorous relationship. How long the affair lasted is not known but Gustav and Sonja’s romance is substantiated by notations on a paper fan found among Sonja Knips’s personal effects.” Those included a love poem dated 1895, the year before Sonja married Anton. A member of her family had told Miller the affair ended because Klimt was unwilling to marry her. The fan was thus “a love note and a farewell”, Klimt having ended another affair in the same manner…and given that Sonja sat for Klimt’s portrait scarcely a year after her wedding, Miller felt “It is hard to imagine that the painting could have been produced without their recent love affair being in the minds of both artist and sitter. She may have viewed the portrait as an enduring reminder of the relationship; it was noted by an acquaintance of Sonja’s that her eyes would light up when she was asked about the history of the painting’s creation.”

As mentioned, Sonja Knips kept the painting until her seventy-seventh year and, as Miller noted, she purchased Klimt’s unfinished (and highly erotic) Adam and Eve after his death and hung it “in the small boudoir next her bedroom”. Partsch will have none of Miller’s account, writing (Taschen, 2012): “On the basis of this fan and the decoration on the reverse side, Manu von Miller reconstructed a love affair between Gustav Klimt and Sonja Knips before her marriage and proposed that Klimt used the fan as a way of ending their relationship. Miller also suggests that Klimt may have done the same with a second fan destined for an unknown recipient and on that occasion carrying the German proverb… (‘Best to get unpleasant things over and done with’) … It is my view that the fan belonging to Sonja Knips points neither to a love affair between the artist and his model nor to a rupture between the two. Rather, it shows Klimt expressing his congratulations to Sonja Knips upon her engagement…”

What then, to make of the prominently displayed (- almost at the picture’s geometrical centre) little red book? In 1992 Nebehay wrote of “a small red notebook: a sketchbook that Klimt gave her.” It had been found in Sonja Knips’s estate and edited by Nebehay and was one of only three such surviving notebooks. It contained a small photograph of Klimt. Alice Strobl had dated Klimt sketches in it to between 1897 and 1899. Strobl had reported an eyewitness’s recollection of Klimt’s studio floor “strewn with thin red notebooks in which he jotted his artistic ideas down in shorthand, as it were.” Nebehay notes that Klimt was as disorderly with his notebooks as with his sketches which lay about in heaps on the floor.

On the book’s possible significance, Nebehay, like Partsch, leaned towards scepticism: “A married society woman would never have dared keep anything that was more than a souvenir” and, he went on, “Johannes Dobai reports that the lady [Knips] told him that the figures hidden in the foliage behind her had no symbolic meaning and as for the notebook in her hand, that was chosen for the colour effect.” Against that, Weidinger wrote in 2007:

“During his second series of studies, Klimt appears to have wanted to portray Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann holding a rose in her right hand, but in the final version decided against this. The little sketchbook Sonja Knips is portrayed holding serves a similar purpose. Her claim that Klimt had merely wanted to add a shot of colour can be refuted on the grounds that the book appears in the studies for this work as well. Klimt is clearly using the book as an attribute which he considers apposite.”

Alma Schindler who so jealously and angrily cited Klimt’s affair with Rose had been delighted when Klimt preferred to make a new fan for her rather than contribute to a fan gifted by another man. Klimt pursued Alma as a teenager and was greatly distressed when prevented from initiating an affair with her. Klimt, as mentioned had known Sonja, too, as a teenager before her marriage. If the presence of the book is to be discounted, what of the picture’s part-hidden Cupid and figures and why have they been so uniformly dismissed on the sole testimony of a technically penetrating image?

Partsch contests an affair against much evidence and trusts an infra-red image: “The dominant field of blackish brown, which provides a foil to the flowers and the female sitter, contains several lighter patches. These have inspired numerous interpretations… [which infra-red photography] has failed to confirm…” In 2008 Rachel Barnes (Gustav Klimt) wrote: “There was a theory that Klimt painted a number of things in the background, including a horse. Subsequent infra-red examination has proved this was not the case.”

It is unfortunate on many levels that in modern times scholars turned from artists to restorers for guidance on technical and aesthetic matters when restorers have no technical means of analysing artistic values and, through their interventions, so repeatedly demonstrate inabilities even to recognise and respect them. It seems that nothing might arrest their long march through the world’s art – no matter how egregiously they mangle its images and, hence, meanings. We live in hope that owners and scholars will better defend the integrity and dignity of works of art but note that we first complained of restorers’ manifestly and indefensibly destructive actions – and of art historians’ effective complicity – in an article, “A crime against the artist”, in The Independent of 22 November 1991 as reproduced below at Fig. 34:

Michael Daley, Director, 29 April 2021