When major museums acquire major pictures, they invariably take additional technical and artistic possession of them through restorations. By transforming pictures’ appearances, museum staffs lay claim to an exclusive up-to-the-minute knowledge of a picture’s material and artistic traits that renders all earlier studies obsolete and activates use of the possessive “our” – as in “our Duccio” or “our Artemisia Gentileschi”. For much-criticised museums like the National Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the introduction of a well-preserved picture within a collection risks spotlighting in-house restoration damage – as might well have happened, for example, had the Met exhibited its newly acquired, fabulously well-preserved Velazquez portrait Juan de Pareja and its Perino del Vaga The Holy Family with the Infant St John the Baptist before restoring them. Today, the National Gallery seeks to counter long-standing criticisms by allowing its restorers to present their own interventions and purposes through broadcast social media. In a press release of 2 August 2019, the gallery’s Director of Collections and Research, Caroline Campbell, said of a restored panel painting:

“The National Gallery is one of just a handful of institutions across the world that is able to carry out painting conservation of this complexity. As this work has been carried out behind closed doors, this display is an opportunity to share this expertise with the public and also to celebrate our conservation skills, in a similar way to how we shared the conservation of our Artemisia Gentileschi self-portrait via a series of films.”

Such hubristic public relations manoeuvres are risky. As Michel Favre-Felix, painter and President of ARIPA (Association Internationale pour le Respect de l’Intégrité du Patrimoine Artistique), demonstrates below, restoration errors are still to be encountered among the nation’s pictures and the restorers’ own explanations leave conspicuously unaddressed questions. [M.D.]

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the National Gallery’s Artemisia Gentileschi Self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, as presented by the Paris-based auctioneer Christophe Joron-Derem for the 19 December 2017 auction; right, as subsequently restored by the National Gallery.

Michel Favre-Felix writes:

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, which was acquired two years ago for £3.6 million (a record for the artist), has already become a new iconic painting of the National Gallery. To the appeal of a self-portrait by the most celebrated female painter of the 17th century, the picture (above, Fig. 1) adds a telling symbolic aura. Commentators have not failed to underline that this martyred saint Catherine, holding the instrument of her ordeal – the miraculously broken spiked wheel – persevering in her faith in the midst of persecution and rewarded with eternal salvation, mirrors the shattering life-story of Artemisia herself, young victim of a rape, maintaining her testimony under torture and finally triumphing in her female artist career. This emblematic portrait is the central feature in the present major exhibition of her work – the first ever in UK – “Artemisia”, National Gallery, London WC2, until 24 January 2021.

Just two weeks after announcing the purchase, in July 2018, the National Gallery began posting on YouTube the first of what became a long series of videos of the restoration in progress (see the list at the end of this article). No fewer than four of them deal with the picture’s cleaning – the need for it (which will be discussed below); the expected effects; its progress and its results.

Such a pedagogic/celebratory (to re-use Caroline Campbell’s expression) public programme is unprecedented. Hitherto, if the Gallery decided to communicate an account of one of its restorations it usually appeared in its scholarly Technical Bulletin, with a strong emphasis on the scientific analysis of the picture’s material structure and a minimal part, if any, given to the hands-on cleaning process itself. The set of YouTube videos exactly reverses that relationship.

As in political discourses, vocabulary plays a key role and carries far-reaching meanings. Old traditional terms might surface, as when the curator, Letizia Treves, observes rather innocently that ‘the picture is quite dirty’, expressing her expectations from its forthcoming cleaning (in Who was… 4:18). ‘Dirty’ is the customary loaded codeword used to justify a total varnish removal. It leaves no room for investigations or nuances: ‘dirt’ cannot reasonably be even partially kept on a painting; it must be entirely wiped out. (See Fig. 1, above, left, for the pre-restoration condition.)

Larry Keith’s expressions are purposefully different. He not only restrains himself from using the loaded and derogatory, non-scientific term ‘dirt’ to describe what is in reality a coat of old varnishes, but he takes care to amend the ambiguous twin-word of ‘cleaning’, by changing its sense, at the start of his talk (in Cleaning… 0:25): ‘Cleaning meaning the… [short pause] …reduction of the old discoloured degraded varnishes’ (“reduction” being the operative word). This singular short pause in his otherwise fluent and dynamic speech is eloquent.

A closer look shows that this change of definition has matured over several years. The cleaning of the Virgin of the Rocks, in 2009/2010, was already presented as a ‘reduction’ [Endnote 1], although this peculiar aspect went rather unnoticed at the time [2]. Earlier, when commenting on the restoration of Guido Reni’s The Adoration of the Shepherds in 2007, Larry Keith mentioned that to clean might be ‘to remove or reduce the old discoloured varnishes’ [3]. If cleaning now means a reduction rather than an elimination, this new position has generated a number of unaddressed questions.

1) First, what does this policy change reveal about the systematic total cleanings made in the past? What happened to the previous certainties on which the gallery’s conservation policy was grounded and which had served to authorise its restorations? Since the post-Second World War ‘Great Picture Cleaning Controversy’, the gallery’s conservation department maintained, against its national and international critics, that a complete removal of varnish was the only way to establish the true, objective, unfalsified state of a painting, and to recover as closely as possible its original appearance as created by the artist. This was not held to be one option among others. It was the inescapable and inevitable conclusion of methodical reasoning itself. The leading proponent of this policy, the de facto chief restorer, Helmut Ruhemann, went so far as to list nine ‘main Arguments against Part Cleaning’ in a crucial chapter of his 1968 book The Cleaning of Paintings (pp. 214-217), which had set the Gallery’s official institutional methodology for more than half a century – and still exerts an influence.

Part-cleaning was not only ruled out in theory but was held to be both unfeasible and deceiving in practice. Ruhemann’s strongest and most persuasive arguments were technical ones. Using the authority of the practitioner, he asserted that a reduction of the varnishes regularly produces an uneven result leaving disruptive and disfiguring ‘patches’ scattered all over the paint. He claimed that a half-way cleaning was arbitrary and inevitably imprecise, the restorer being ‘condemned to groping in the dark’. He stressed that, if there was some old varnish left, it would be impossible to suppress all the faulty and distorting old retouching that might lie underneath. Moreover, he added that the new retouches would never correctly match the still imperfectly cleaned paint.

This argumentation, unchallenged for decades, happens to have been refuted by Larry Keith’s recent practical demonstration. Although Keith used traditional means (no revolution in tools or solvents or monitoring is used in the Gallery) his ‘reduction’ did not generate the Ruhemann-predicted failures: it neither failed to suppress the old retouches nor to avoid uneven ‘patches’ – nor even failed to achieve perfectly matching indiscernible new retouches.

2) What is the reason for adopting partial cleaning today? On the one hand, in hindsight, we can see that the previous policy of total cleaning was based on spurious arguments but, on the other, it is striking that no revised or new justification is provided in support of the present policy.

Why is it now considered to be appropriate, required – or even essential – to keep a part of the old so-called ‘degraded and discoloured’ varnishes on this painting? Is it to serve as a guarantee for the safety of the paint and possible original glazes underneath when subjected to the cleaning with solvents? Does this last layer of old varnish bear a meaningful aesthetic and/or historic value that ought to be preserved? Does the remnant of the surface coating constitute part of the artistic authenticity of the work of art? Keith provides no indication at all. A full range of arguments in favour of part-way cleaning have been put forward elsewhere since the 1950s by connoisseurs, critics and art historians but Keith refers to none.

In reality these questions concern a majority of works because this portrait is not at all an exceptional case. It was, at the time of its acquisition, in a ‘standard’ condition that is common to so many paintings from past centuries that have been subjected to restorations: from the Gallery’s report it turns out that its surface bore the usual old retouching, and its canvas, already relined as was customary in the past, had since suffered a small tear and will be relined anew.

Acknowledging the ‘reduction’ of the varnishes as the best possible care for this painting implies/concedes that it should have been similarly prescribed and applied successfully to so many comparable paintings, affected by the same usual damages, but which were radically cleaned at the National Gallery.

3) Larry Keith never explains in his videos why he chooses to thin rather than to remove the coat of ‘degraded’ varnish, as was the rule before. He simply strives to show why the old varnish needed a treatment and to demonstrate that he achieved ‘key improvements’ on the test areas where it has been reduced.

About the state of the varnish he draws a distinction, not without reason, between two effects: ‘these old varnishes when they degrade, they turn yellow and they turn foggy…’

That is true in a general way, but it is precisely from there that reflections should begin, because while the first is the natural, predictable, regular evolution of traditional materials, the latter is an unfortunate degradation that preventive care could avoid.

Above, Fig. 2: Screen capture from the video “Cleaning…” – See the full linked-list of videos below.

On this first issue, that of yellowing, the explanations are especially puzzling:

[in Cleaning… 1:27] “You see that where the varnishes have been reduced, the overall tonalities of the picture are much less yellow. The fingers [on the left] are emerging rather pink, instead of this kind of yellow colour [on the right] and I am sure that will become more evident as we move across the picture…”

These comments are puzzling because they hardly fit with what is shown. The old varnish did not turn the skin tonalities markedly and disturbingly yellow (compare the back of the hand on the right with the old varnish on, to the ‘reduced’ one on the fingers on the left at Fig. 2 above), and it is indeed anything but ‘evident’ that it distorted the perception of the colours. It may be recalled that in December 2017, during the presentation of the painting before its auction in Paris, the expert Eric Turquin praised the ‘subtle pinks’ – in his own words – he had no trouble distinguishing in the flesh tones of the portrait with the old varnish on [4].

Above, Fig. 3: Photograph (detail) from the Hyperallergic site, 12 July 2018, showing the “Artemisia” exhibition curator, Letizia Treves, facing the self-portrait before cleaning began. Although top lighting caused a pale reflection on the canvas, lightening the dark tones, it can be seen here that Artemisia’s flesh tones are not so much yellowish as close in their pinkness to the curator’s own natural colouring.

Above, Fig. 4: The restorer Larry Keith, examining the painting before cleaning began, as shown on BBC News 6 July 2018.

The above photos published in July 2018, at the very start of the intervention, in which spectators are present confirm that the variety of colours in the painting was clearly perceptible: the shades of pink of the face, the cream tone of the headscarf, the Naples yellow of the palm leaf or the ochre of the wood read easily and naturally. One can observe that there was no oppressing monochrome veil distorting the shades of the portrait, which were quite close to the natural skin tones of the viewers, as the photographs testify (Figs. 3 and 4).

Surprisingly, if not tendentiously, Keith even evokes an ‘accumulation of varnishes’, which he ventures would result from ‘many restorations that have probably occurred’ in the past (in Cleaning… 4:35). ‘Many’ is merely hypothetical since the history of this painting is totally unknown between the years of its creation, circa 1615-1617, and the 1940s when it resurfaced, only to be quietly kept in a French family (Pes, J. 2018).

Looking at the photographs of the initial state, it is difficult to deduce a superimposition of many added layers. Fortunately, this will be checked since Keith has announced that ‘minuscule samples [will] help us understand the layers structure of the accumulation of varnishes’ (in Cleaning… 4:35). Fine. It will be of great interest for the public and the experts that the result of this investigation by the laboratory be disclosed: how many layers of old varnishes? To what total thickness? Until these results are established and cited the idea of an ‘accumulation’ of layers of varnish will remain a puzzling assumption.

4) Beside the issue of yellowing – that he admitted not to be ‘evident’ – Keith places a greater emphasize on the second, undisputable, aspect of the picture condition, that of the varnish getting foggy. This loss of its transparency is, by contrast, plainly documented.

Even during the presentation at the 2017 auction in Paris, while the subtlety of the colours was praised, the ‘dullness of the varnish’ was nonetheless underlined and attributed to the fact that the painting had remained in the same family for several generations.

The video illustrates the consequences of this phenomenon (in Cleaning… from 1:40):

“… where [the foggy varnishes] are over the darker tones, the darker tones become quite a bit lighter. You can see that here, with that sort of hazy presence. And whereas down here where I started reducing the old varnishes, you can see the darker colours are much darker and the range from light to dark is much enhanced. And I think this helps you understand how [Artemisia] has laid out the folds, and helps you understand what is in front of what.

“…I think the thing here [in the ‘reduction’ in progress] that is most significant and really very rewarding is to see now the range from light to dark, which [Artemisia] has used, and her modelling of forms, which gives this sculptural presence.”

Indeed, Artemisia’s artistic expression rests on the illusion of spatial depth and on the convincing impression of three-dimensional figures. And this pictorial achievement is only displayed when the half-tones, dark values and contrasts have their full effect, which requires a good transparency of the varnish final layer.

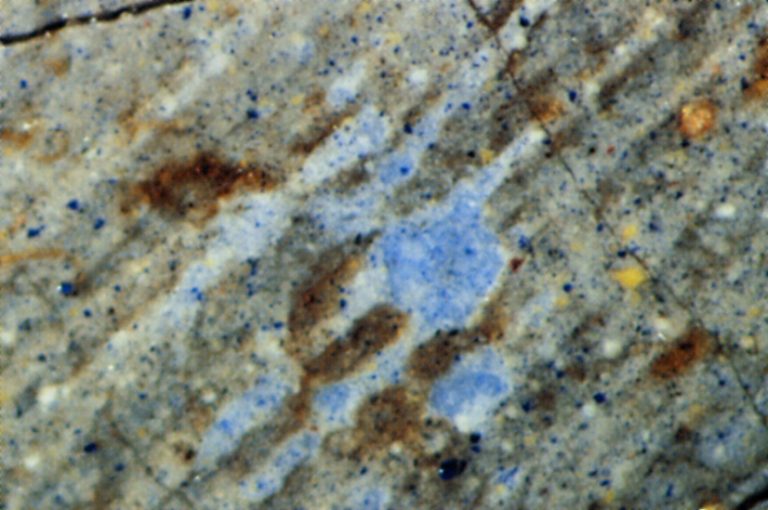

It is hence plainly justified to try to regain this fundamental quality. However, in the case of this painting, such faint cloudiness is a common and rather benign alteration caused by humidity (that is to say, by a lack of prevention from its keepers). Physically, this phenomenon results from the scattering of light – not exactly on the ‘varnish’s own kind of fine cracks’ as it is said rather simplistically in the video – but on a multitude of micro-fissures, much smaller than usual cracks, that have developed within the varnish film at a microscopic scale that is invisible to the naked eye.

Above, Fig. 5: Above, Fig. 5: detail of Artemisia’s arm, showing un-thinned (slightly dull) varnish on the right and thinned varnish on the left.

As can be seen on the video, the thinning of the varnish has cleared the cloudy effect and has thus enhanced saturation and contrasts [above, Fig. 5]. Yet, the cause/effect relationship is not that simple. The dissipation of the hazy opacity is the result of a specific physical process: it comes from the ‘closing’ of the micro-fissures, which is obtained through the momentary softening and swelling of the varnish film when suitable solvents are applied to it. Once the solvent has evaporated, the micro-fissures have closed and so, vanished. Since the ‘reduction’ was done with solvents, their penetration into the varnish film provoked the swelling/closing result. Thus, this was a linked side-effect and it would not have been necessary to thin the entire varnish layer for that to happen. For this kind of light haziness, a simple exposure of a varnish surface to an appropriate solvent, at much lower levels – i.e. ethanol in form of vapours – without any ‘reduction’, could have produced the same positive result (Pfister, P. 2011, Demuth, P. 2001): the saturation of colours; the in-depth setting of the figure; the sculptural modelling created by Artemisia, would all have been recovered.

Of course, when such a minimal treatment is chosen, the tonality of the varnish remains unchanged, since its thickness is undisturbed even as its transparency is regained.

Knowing this, we realize that there is confusion between the two results. In truth, a physical reduction was not essential to recover the range of values from light to dark and modelling of forms intended by the artist, which could have been achieved otherwise. Essentially, the thinning of the varnish was used principally and specifically to obtain the ‘much less yellow’ overall tone. This result is held – in Larry Keith’s account – to be such an obvious improvement as to require no further justification. Yet, it does – and we see below why it needs questioning.

5) The transparency is a basic undisputed requirement for this varnish (as for any other). But what is the justification for making it ‘much less yellow’?

When we leave aside our own era’s cultural preferences and consider the materials and varnishing practices that prevailed in the XVIIth century, we realize that the (disparaged) ‘old varnish’ found on this painting had the best chance of resembling the original finished appearance as made by Artemisia herself.

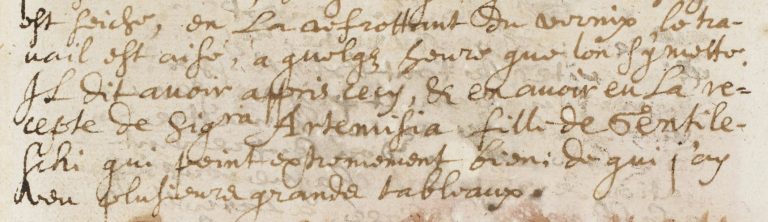

Above, Fig. 6: A section of de Mayerne’s text (Folio 151r) mentioning Artemisia Gentileschi and her varnish.

Throughout these supposedly informative and instructive videos it is striking that no reference is ever made to the kind of varnish that would have been used by the artist herself, or, even, to those that were common in her circle and time in Italy. This omission is hard to justify since relevant historical and technical references have survived and are accessible. For example, Turquet de Mayerne’s manuscript notebook (written between 1620 and 1646), which is the main historic testimony and source of information on the painting techniques of this period, contains a famous reference to an ‘amber varnish’ [5], ascribed to both Artemisia (active c. 1610-1653) and her father Orazio Gentileschi (active c. 1587 -1639) – see Fig. 6, above. De Mayerne specifies that this varnish had a strong reddish tone and was used by the instrument makers to varnish lutes [6].

It should be borne in mind that, at that time, in the absence of precise identification, the term ‘amber’ (otherwise called ‘c(h)arabe’) encompassed a group of resins that were close by their consistency, colour, workability and effect – and among which were chiefly the different semi-fossil resins that we now classify as copals, which range from semi-hard to hard and are easier to dissolve than true fossilized amber (Leonard et al. 2001, Holmes, M. 1999).

Furthermore, the expression amber varnish ‘coming from Venice, with which they varnish lutes’, added in the passage on Orazio (Folio 9v), most probably indicates a ready-made product. At that time in Italy many varnish formulations were no longer made in the artists workshops but prepared and sold by colours merchants. The painter Gian Battista Volpato quotes the ‘amber varnish’ as one of them [7]. De Mayerne states that a so-called ‘Oil of Amber from Venice’ (that is, a fat varnish made of ‘amber’ dissolved in a possibly larger proportion of oil), which he supposes to be the one used by Orazio, was sold in every Italian colour shop [8]. The main point is that these prepared varnishes formed a dry film that approached the legendary hardness of amber and had a similar golden-brassy colour. Some rosin (colophony) could be added, which was useful for improving the working properties of the mixtures (Leonard et al. 2001). Its marked orange hue would also increase the warm tonality of the whole – see Fig. 7 below.

Above, Fig. 7: Colophony (or rosin, resinous part remaining after the essential oil has been extracted from the balsam of Pinus maritima Lamb. by distillation.)

It is mentioned that Artemisia mixed her ‘amber’ varnish with oil and spread the blend as an intermediary layer upon the already dried parts of her work in progress, before continuing to paint (Folio 151r). This method, commonly called ‘oiling-out’, has three benefits for reworking: it brings back the initial saturation of the first colours that might have turned dull when drying; it enables a fluent application of the later colours; and, it promotes their physical adhesion to the ones beneath.

Concerning Orazio, de Mayerne notes that he used to add a drop of ‘amber’ varnish directly to his colours on his palette – especially to the ones of the flesh tones – in order to make them more ductile and quicker to dry (Folio 9v).

Was it also chosen as final varnish? The use of the same compound for mixing with colours, for intermediary ‘oiling-out’ and for final varnishing is indeed consistent with what is known of painters’ practices at the time. Examinations of paintings by Caravaggio (of whom Orazio was a disciple) have shown that remains of his final varnish – resin in oil – were similar to the ‘oiling-out’ layers found in his paint structure (Arciprete, B. 2004).On the same folio (151r) where de Mayern mentions Artemisia’s oiling-out method, he reports on another ‘charabe’ varnish, which can be used ‘for varnishing and for mixing on the palette with the colours’ [9].

Moreover, a discovery made by the Getty Conservation Institute in 2000 confirms that Orazio also adopted an ‘amber type’ varnish of his final coating. Found on one of his painting (Lot and his Daughters, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) executed about 1622, this rare original varnish proved to be composed of Manilla copal and rosin, precisely (Leonard et al. 2001) [Figs. 7 and 8].

Above, Fig. 8: Manilla Copal (from Agathis dammara Lamb.)

This tangible historical/material evidence of what was an ‘amber-like’ formulation provides a precious testimony of its visual effect on the picture: it displayed a notable warm golden tone over the parts where it was still present (see Figs. 9 and 10 below). Given that Artemisia learnt to paint in her father’s studio, it is beyond doubt that Orazio would have shared both his materials and his practices with his daughter.

Above, Fig. 9: The effect of Orazio’s varnish on the sky of his Lot and his Daughters (in The Burlington Magazine’s article, Vol CXLII n°1174, p.5.)

Above, Fig. 10: Macro-photograph of the varnished sky. Note the bright blue colour of the paint that appears in some spots where the ‘amber-like’ varnish is missing (from the same Burlington Magazine article, p.9.)

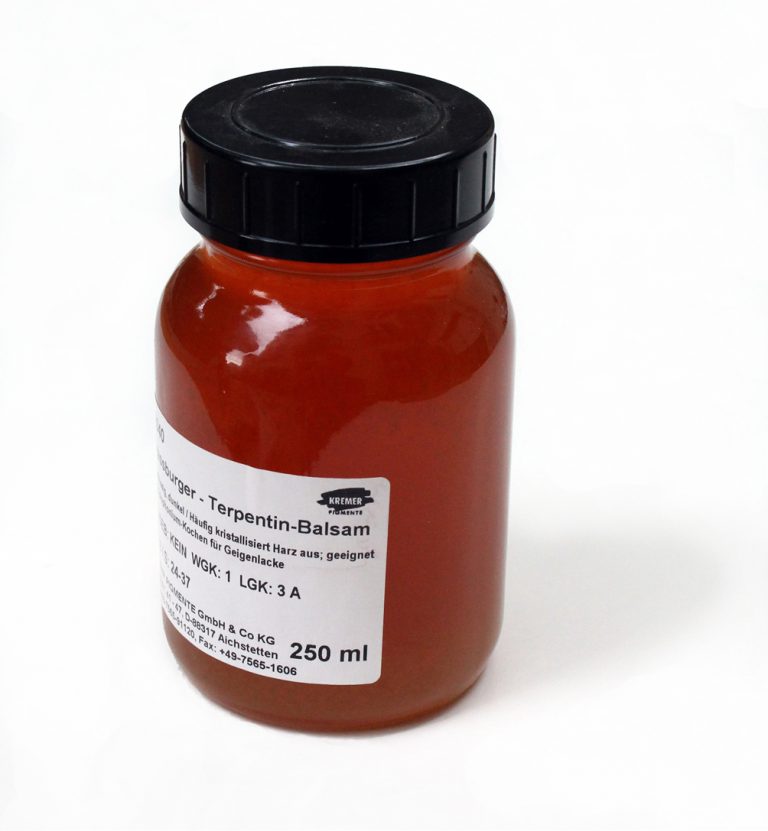

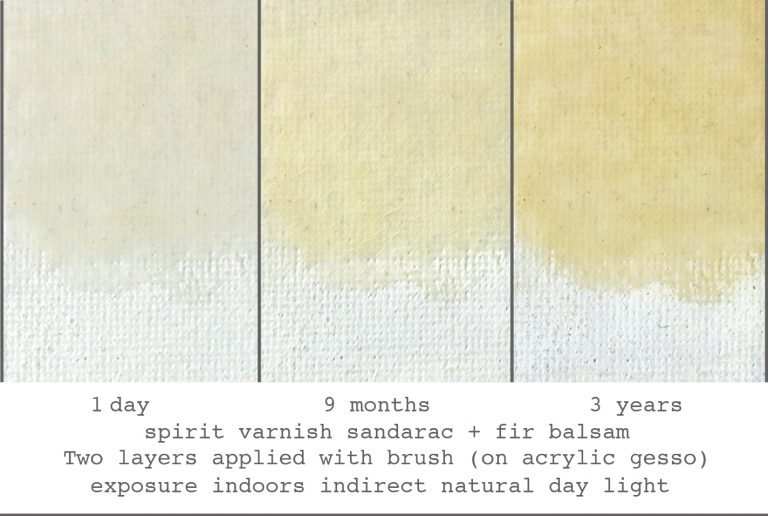

In addition to those clues, there is the certainty that Artemisia’s varnish could only have been composed with resins among those of her time (the end of 16th/ first half of 17th centuries): sandarac; oleoresins balsams from the silver fir, the larch or the spruce; colophony; mastic; copals, with or without oil [10] (Figs. 7, 8, 11 and 12). Reconstructions of historical recipes with such ingredients, prepared and applied following traditional methods are converging to show that they provided a natural warm tone – a ‘golden glow’ – that moreover increased surprisingly quickly (Favre-Félix, M. 2017, Carlyle, L. 2005, CCI 1994) (Fig. 13).

Above, Fig. 11: Strasbourg turpentine (balsam – oleoresine – of the silver fir, Abies pectinata DC. – from Kremer Pigmente.)

Above, Fig. 12: Sandarac (from Tetraclinis articulata Mast.)

Above, Fig. 13:As an example, the reconstruction of an historical recipe, using one resin and one oleoresin – a type that became increasingly prevalent from the end of the 16th and throughout the 17th centuries – showed a notable increase of its natural coloration within a short time.

Thus, there lies a major contradiction of modern restoration: the profession asserts a strict adherence to the scientific study of the artists’ materials and techniques, but continues to ignore the technical characteristics of the varnishes that are known to have been used in those centuries. Further, while it aims to present paintings as close as possible to the artists’ conception it still declines to take into account how their paintings had once looked with their original final layer on, and it persists in eliminating the ‘yellow tone’ of any varnish encountered on old master paintings.

CODA:

A last video deals with the significant choice of a frame for Artemisia’s self-portrait. The Head of Framing, Peter Schade, points out that an authentic frame from the 16th century – wood-carved, painted or gilded – will always surpass any copy of it, even those that look to be perfect reproductions. He makes the following crucial remark [Choosing… 8:45]: “We always carry the baggage of modernity, of our time… And that gets always in some way transferred into reproduction frames. Usually, we don’t see it now but you can look it back at the history of frame reproductions, in the gallery as well, and [see that with] most reproduction frames, after twenty, thirty years they don’t match up to originals.”

Larry Keith had then to admit – albeit in carefully chosen words – that the same rule of unwilling, modern distortion applies to restoration:

“[9:12] …It is the same thing about how we… decisions we make about restoration itself, you know. We think we try to be… I guess what we can say now, is that we are very transparent about the decision-making process but it’s definitely an interpretation all the way down the line”.

Restoration being a contemporary “interpretation” of the work of the past, transparency is essential, and transparency implies clear explanations for the present and for the older interventions. But, strikingly, Larry Keith has not explained in any way the main justification for reducing rather than eliminating surviving varnishes. With regard to the use of retouching – e.g. in the reconstruction of the cropped top of the crown – his presentation and discussions are fair (see Reconstructing… and Retouching…) But on matters of cleaning and varnish this essay’s conspicuous technical, aesthetic and historical documentary omissions testify to an enduring institutional avoidance of transparency on the most vital artistic questions of art conservation at the National Gallery.

Above, Fig. 14: Artemisia’s Self-portrait, left, as in 2017 at auction; centre, same state but as provided by the National Gallery to the press in July 2018, before cleaning; and, right, as at the end of 2018 at the National Gallery, after cleaning and restoration.

Michel Favre-Felix, 9 October 2020.

THE NATIONAL GALLERY RESTORATION VIDEOS:

1) Starting the restoration of Artemisia Gentileschi’s ‘Self Portrait’ – Now entitled: “The art restoration plan for Artemisia Gentileschi’s ‘Self Portrait'” – as posted on the 20th of July 2018.

2) Cleaning Artemisia Gentileschi’s ‘Self Portrait’ – as posted on the 27th of July 2018.

3) ‘It’s such a 17th century thing to do’ | Cleaning Artemisia Gentileschi’s ‘Self Portrait’ – as posted on the 3rd of August 2018.

4) Who was Artemisia Gentileschi? – as posted on the 20th of August 2018.

5) Finishing the cleaning | Cleaning Artemisia’s ‘Self Portrait’ – as posted on the 30th of August 2018.

6) Repairing a 17th century canvas – as posted on the 10th of September 2018.

7) Applying the moisture treatment – as posted on the 21st of September 2018.

8) Finishing the relining – as posted on the 2nd of October 2018.

9) Reconstructing the unusual composition of Artemisia’s ‘Self Portrait’ – as posted on the 9th of October 2018.

10) Retouching a 17th century painting – as posted on the 13th of November 2018.

11) Choosing a frame – as posted on the 26th of November 2018.

12) Framing Artemisia – as posted on the 14th of December 2018.

ENDNOTES:

[1] “Indeed not all the old varnish was removed – it was simply reduced to a level which helps us to fully appreciate the painting.” (Larry Keith – Restoring Leonardo, National Gallery website.)

[2] “By removing the ugly varnish…” Jonathan Jones commenting on this cleaning in The Guardian, 13 July 2010. When reviewing the National Gallery’s restoration of its Leonardo Virgin of the Rocks, Jones expressed delight that the painting had been “freed from an amber prison”.

[3] National Gallery Podcast: Restoring Reni’s ‘Adoration of the Shepherds’, 1 :48.

[4] ARTECENTRO – Artemisia Gentileschi, Sainte Catherine d’Alexandrie, vente le 19 décembre 2017. Time 2: 47.

[5] ‘Vernix d’Ambre venant de Venise’ (Sloane MS 2052 Folio 9v).

[6] ‘Ce Vernix est fort rouge & est celuy des faiseurs de Luths’ (Sloane MS 2052 Folio 150 v).

[7] ‘quella d’ambra si compra, quella di mastice la facio io’ (Merrrifield, M.P, p. 743).

[8] ‘Chés touts les vendeurs de couleurs en Italie on vend une huile espaisse, qu’ils appellent Huile d’Ambre de Venise […] Je croy que c’est ceste huyle dont m’a parlé & se sert Gentileschij ’ (Sloane MS 2052 folio 146v).

[9] ‘Et pour vernir: & pour mesler sur la palette avec les couleurs’ (Sloane MS 2052 folio 151r).

[10] Such a choice of resins for varnishes is also noted by Van Dyck, at the same period, on a folio of a sketchbook: fir balsam, colophony, unspecified ‘vernizia’ and amber varnish (Kirby, J. 1999, p. 13).

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Arciprete, B. (2004), ‘Il restauro’, La Flagellazione di Caravaggio, il Restauro, Electa Napoli.

Carlyle, L. (2005) ‘Representing authentic surfaces for oil paintings: experiments with 18th and 19th-century varnish recipes’, Art of the Past, Sources and Reconstructions. Proceedings of the first symposium of the Art Technological Source Research study group. Archetype Publications.

CCI (1994) Varnishes: Authenticity and Permanence Workshop, Canadian Conservation Institute, (Reviewed by Neil Cockerline).

Christiansen, K., Mann, J. W. (2001) Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi – New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven.

De Mayerne, T. Turquet, (1620) Pictoria Sculptoria & quae subalternarum artium, British Library, Sloane MS 2052. Trancription in Berger, E. (1901) Quellen für Maltechnik Während der Renaissance und Deren Folgezeit (XVI.-XVIII. Jahrhundert), München.

Demuth, P. (2001) ‘Regeneration of blanched natural resin varnishes with solvent vapour’ Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Dresden/ The ENCoRE Symposium: Recent development in conservation-restoration research 19-21 June 2001.

Eastlake, C. L., (1847) Methods and Materials of Painting, Dover Publications, New York (2001)

Favre-Félix, M. ‘On the recipe for a varnish used by El Greco’, Conservar Património 26 (2017) pp. 37-49 – ARP – Associação Profissional de Conservadores-Restauradores de Portugal http://revista.arp.org.pt/pdf/2016023.pdf

Holmes, M. (1999), ‘Amber Varnish and the Technique of the Gentileschi’, in Artemisia Gentileschi and the Authority of Art: critical reading and catalogue raisonné, R. Ward Bissel, Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 169-182.

Kirby, J. (1999) ‘The Painter’s Trade in the Seventeenth Century: Theory and Practice’- National Gallery Technical Bulletin, Vol 20.

Leonard M., Khandekar N., Carr D.W. (2001) ‘Amber Varnish and Orazio Gentileschi’s Lot and his Daughters ’, The Burlington Magazine Vol. CXLIII, pp. 4-10

Merrifield, M. P. (1849) Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting, Dover Publications, New York (1999).

Pes, J. (2018) ‘The National Gallery’s New Artemisia Gentileschi Should Be a Triumph – But Clouds Are Forming Over Its Ownership During WWII’, December 12, 2018, News-artnet.com.

Pfister, P. (2011) ‘Régénération : l’emploi des vapeurs d’alcool et les dangers des alcools liquides’ / Kunsthaus – Zürich / Nuances 42/43, pp. 24-29.

Ruhemann, H. (1968) The Cleaning of Paintings. Problems & Potentialities. Praeger Publishers.