Michael Daley writes: As the world reels from China’s latest plague, the fifteen-year Salvator Mundi Saga has slipped into never-never land. The famously disappeared picture has been likened to an opera by its instigators and is set to become a musical in 2022 in which “artistic liberties will be freely taken to make an enlightening and entertaining experience”. Amazon is offering T-Shirts that carry the Salvator Mundi not as it looked in 2017 when it disappeared but as it looked in 2011 when first presented as a Leonardo at the National Gallery (see below, Fig. 3). The restorer’s own paintbrushes (which had been used to produce three distinctly different states or appearances) were auctioned on eBay with a $1,000 reserve. No bid was received. Back in the real world, before considering the rise and demise of a perpetually morphing disappeared picture’s attribution upgrade that netted $80 million, $127 million and $450 million in two restoration guises over four years on a $1,000 purchase that was overstated tenfold by its owners, we note three further bizarre developments, including a disappeared book of technical analysis and a disappeared Louvre catalogue.

1 – THE LOUVRE’S DISAPPEARED BOOK OF TECHNICAL DATA FOR A DISAPPEARED PAINTING

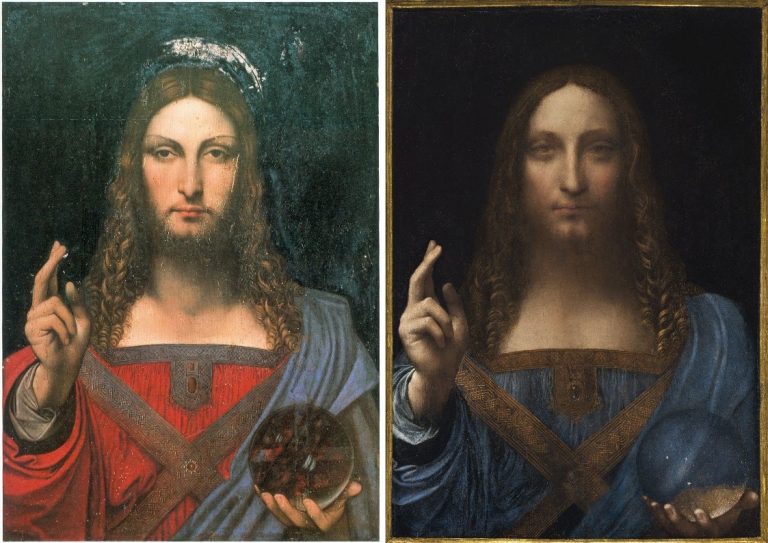

Above, Fig. 1: Left, a disappeared book; right, a disappeared ascription.

On 30 March, the Art Newspaper disclosed that last year the Louvre vaporised a 45-page book of technical examinations made in 2018 on the disappeared Salvator Mundi painting by C2RMF (Centre for Research and Restorations of the Museums of France). The Editions Hazan book, Léonard de Vinci: Le Salvator Mundi (Fig. 1, above, left), had been produced for the October 2019 opening of Léonard de Vinci, the Louvre’s major exhibition marking the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, but it was withdrawn shortly before the opening even though the authors reportedly considered their examinations “to have demonstrated that the work was executed by Leonardo”. (The claim, of course, is implausible: technical examinations can sometimes disprove an attribution but can never establish artistic authorship.)

A Louvre spokesman said the book, written by the Louvre curator Vincent Delieuvin and C2RMF’s Myriam Eveno and Elisabeth Ravaud, had been “a project in case the Louvre got the chance to exhibit the painting” and that because this had not happened “it is not going to be published” – which seems tantamount to saying “If we can borrow it, it’s a technically-supported Leonardo; if we cannot, it’s not”. A copy of the disappeared book has been seen by Dianne Dwyer Modestini, who had restored the picture between 2005 and 2017. Modestini feels the conclusions confirm her own, earlier, judgements, even though they “do not reveal anything I did not already know about the materials and techniques…”

2 – THE LOUVRE’S DISAPPEARED CATALOGUE WITH A NON-APPEARING, NOW DISAPPEARED PAINTING

Second, to the embarrassment of a disappeared book of technical examinations, we disclose another disappeared Louvre publication: the catalogue for the museum’s 2019-20 Léonard de Vinci exhibition was also junked and replaced shortly before the opening. The two editions of the catalogue were identical except for one detail. In the first, the disappeared painting was splashed on the front cover as by Leonardo – “Front cover: Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (detail of cat. 157), Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia Kingdom”. (See Fig. 1, above, right.) The author of that endorsing entry was Vincent Delieuvin, who co-curated the exhibition with Louis Frank. Delieuvin’s public commitment to the Leonardo attribution was made in the catalogue of a small 2016 Leonardo exhibition at the Italian Embassy titled: Léonard en France. Le maître et ses élèves 500 ans après la traversée des Alpes, 1516-2016 (Leonardo in France. The master and his pupils 500 years after the crossing of the Alps, 1516-2016). There, Delieuvin ventured of the now-disappeared picture “…Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi whose autograph version seems to have reappeared very recently, unfortunately in very bad condition. The circumstances of the creation of this work are unfortunately not known.”

In the second printed catalogue, Delieuvin – with no explanation for the volte-face – correctly describes the Salvator Mundi as the Leonardo studio work that entered the Cook Collection in 1900 (on no provenance and that was later sold for £45) – namely: “Salvator Mundi, version Cook, vers 1505-1515″. A second Leonardo studio version, the de Ganay Salvator Mundi, was included in the Louvre exhibition as catalogue no. 158: “Salvator Mundi, version Ganay”. The choice of substitute may have been pointed: the Ganay picture had flopped when proposed in 1978 and 1982 as the supposedly lost autograph Leonardo prototype Salvator Mundi painting of which no record exists. Such notwithstanding, provenance claims made on behalf of that candidate were adopted and merged with those made on behalf of the Cook version. Because of the non-appearance of the disappeared Cook version, originally no. 157 in the catalogue, there is now a gap in the published catalogue between cat. 156 and cat. 158. That numerical lacuna testifies to the fateful loss of institutional support for the second would-be autograph Leonardo Salvator Mundi in forty years. (See Fig. 1, above, right.)

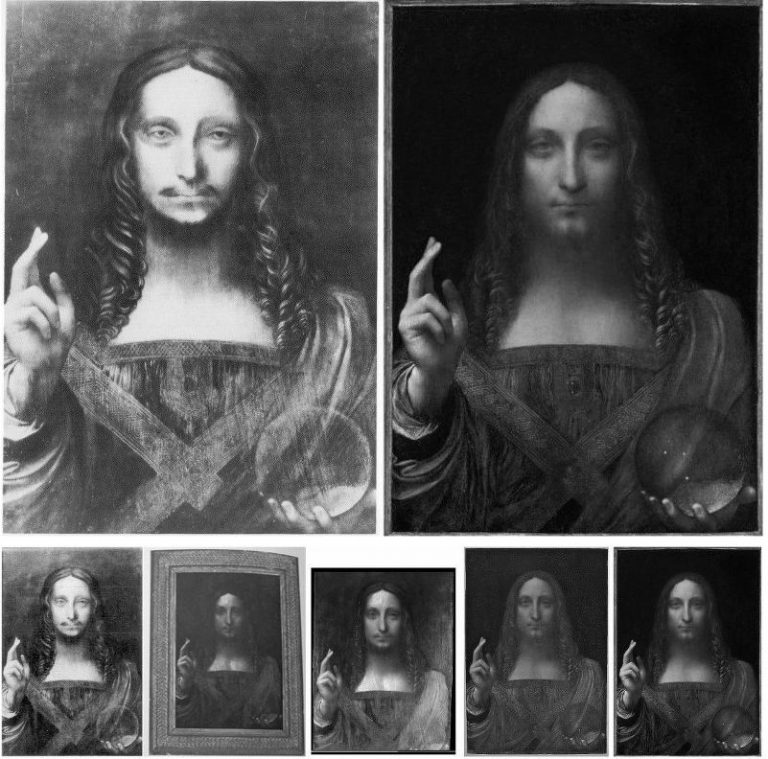

Above, Fig. 2: Left, the de Ganay Salvator Mundi which, in 1978 and 1982, had been proposed as a long-lost Leonardo prototype painting; right, the more heavily damaged and made-over ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi, which was presented as a long-lost Leonardo prototype painting at the National Gallery in November 2011.

3 – SOME DAY, MAYBE, NEVER…

After fetching $450 million in 2017 at Christie’s, New York, as Leonardo’s (supposedly) autograph, (supposedly) long-lost, (supposedly) iconic male equivalent of the Mona Lisa, the painting (really did) disappear without a trace, leaving the world bemused and the picture’s briefly “vindicated” advocates to play blame games. It was promised the painting would be launched as a Leonardo at the official opening of the United Arab Emirates spanking new Abu Dhabi Louvre Museum in 2018. That did not happen. It was said the painting would star as A Discovered Leonardo at the Paris Louvre’s grand 2019 Leonardo blockbuster. That did not happen either, just as we had predicted. The Wall Street Journal has reported that Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Culture has possession of the disappeared painting and plans to store it while deciding whether or not to build an exclusively Western art museum to house this once again officially-deemed Leonardo school Christian image (“Saudi Arabia’s Secret Plans to Unveil Its Hidden da Vinci-and Become an Art-World Heavyweight”, 6 June 2020).

A MUSEUM FOR A PICTURE NO MUSEUM WANTED

It might seem unlikely that the disappeared former Leonardo Salvator Mundi will reappear in a purpose-built museum of Western art in Arabia when it is now well known (thanks to Ben Lewis’s 2019 lid-lifting book The Last Leonardo) that the picture had been offered to, and rejected by: the Getty Museum; the Hermitage; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Vatican; the Dallas Museum; a German auction house; Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, and even, at a knock-down $80 million, to the Qatari royal family.

WHY DID THE BIG WESTERN MUSUMS BACK OFF?

The National Gallery launched the Leonardo attribution in its 2011-2012 Leonardo blockbuster, Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan, after covertly helping to assemble its proclaimed “Unusually Uniform Scholarly Consensus”. The gallery made no attempt, however, to buy the Salvator Mundi. Similarly, and notwithstanding National Gallery claims of blanket endorsement by the Metropolitan Museum’s curators of pictures and drawings, the Met, too, did not buy what Christie’s dubbed “The Last Leonardo”. Despite publicly avowing support for the Leonardo ascription, the Met’s Chairman of European Paintings, Keith Christiansen, has (so far as we know) written nothing in its support – in marked contrast to his decisive role in the museum’s 2004 purchase of the tiny Madonna and Child that Christie’s offered as the “The Last Duccio”. Where the Met’s director, Philippe de Montebello, shuffled financial mountains to acquire the Duccio at Christiansen’s behest, Thomas Campbell, de Montebello’s successor from 2009 to 2017, tweeted after the 2017 $450 million Salvator Mundi sale that he hoped the mystery buyer “understands conservation issues” and had “read the small print”. Many were sickened by Christie’s globally-hyped removal of a sixteenth century painting from an old masters’ sale context to offer it (buttressed by cross-linked and mutually assured sale guarantees) among trophy modernist “icons” – and all on a picture Christie’s had passed over when it was offered in 2005.

“SALVATOR MUNDI IS A PAINTING OF THE MOST ICONIC FIGURE IN THE WORLD BY THE MOST IMPORTANT ARTIST OF ALL TIME” – LOÏC GOUZER

Above, Fig. 3: Left, Loïc Gouzer, Christie’s former co-chairman of Americas post-war and contemporary art, next to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled at a press preview; centre, the Salvator Mundi as when sold as a Leonardo at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017; right, the Amazon T-Shirt sporting the Salvator Mundi as it appeared at the National Gallery in 2011 with many more folds visible in the drapery at Christ’s (true) left shoulder – see below, Figs. 8, 9 and 10.

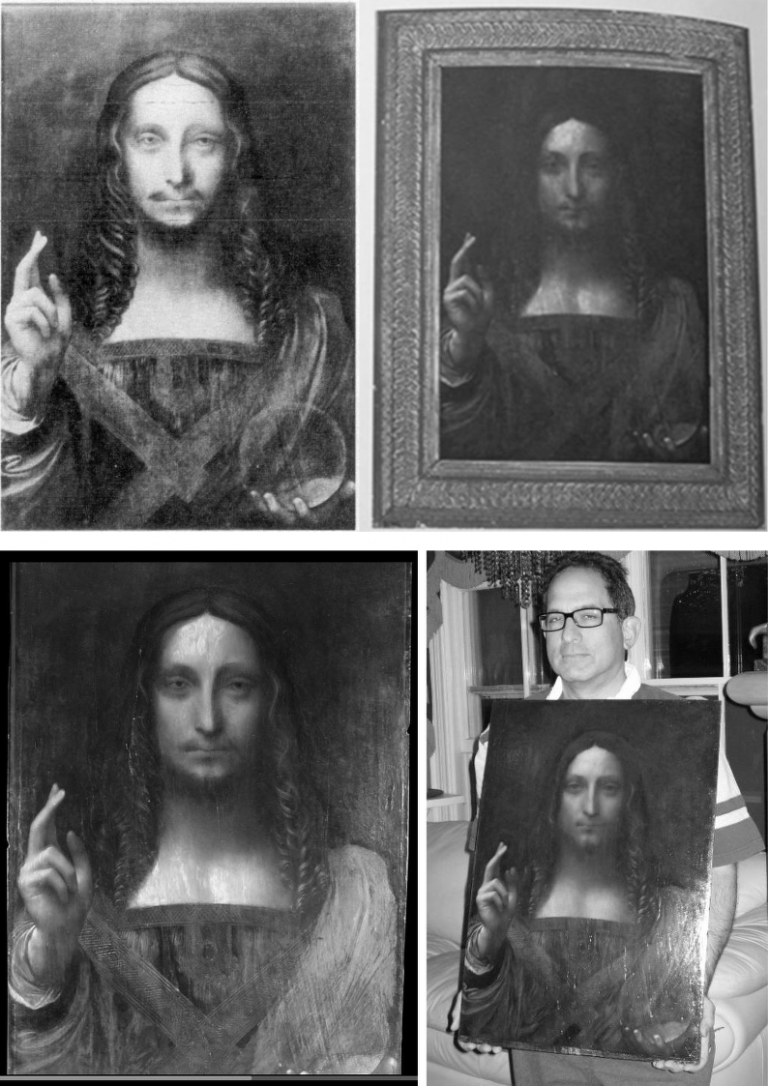

Above, Fig. 4, top row: Left, a c. 1913 photograph of the Salvator Mundi when in the Cook Collection, England; right, the Salvator Mundi as when sold at Christie’s in November 2017. Bottom row: the same time-line changes with three intermediary states from 2005; 2005; and 2011-2012 (when exhibited as a Leonardo at the National Gallery).

THE INTENSIFYING CRISIS OF ART MARKET CONNOISSEURSHIP

The epically long Salvator Debacle has put the abiding old masters’ connoisseurship crisis centre stage. To restate the intractable root problem: supply is finite – the old masters aren’t working any-more; most big-name works are already in museums; and infinite new global money craves art that bestows cachet and respectability. In February 2018, Guillame Cerutti, Christie’s CEO, purred: “our major clients are looking for trophies. They want quality and rarity in any field. This painting had both aspects, it ticked all the boxes”. Such a global trophy-hungry market can only be grown with dramatically upgraded art trade “sleepers” or outright forgeries. Both stand on restorers’ transforming skills which, along with claimed technical discoveries, licence scholars’ elevation of formerly nondescript works to revered Lost Masterpiece status.

MUSEUMS BEWARE

For Big-Name buyers, risks are high and can trip the grandest museums. The Metropolitan Museum’s David was one of its most popular paintings… until it wasn’t a “David” anymore. In 2004 the Met’s director, Philippe de Montebello, spoke of the “Stoclet Duccio” Madonna and Child as “Filling a gap in our Renaissance collection that even the Metropolitan had scant hopes of ever closing, the addition of a Duccio will enable visitors for the first time to follow the entire trajectory of European painting from its beginnings to the present. Moreover, the Duccio Madonna and Child is a work of sublime beauty. This was a unique opportunity to not only to add a masterpiece to the Museum’s holdings but to give its collections a new dimension.”

The institutional gush was infectious: “The Stoclet Duccio – we can now proudly call it ‘the Metropolitan Duccio’ – is an astonishing achievement”, wrote the New York restorer/some-time dealer, Marco Grassi, who likened the picture’s emergence to a discovered Mozart quartet. The disappeared Salvator Mundi is now likened by its original owners/supporters to the discovery of a new planet: “Paintings by the master are as significant culturally as the planets are celestially”. (It must seem cruel to have discovered and lost a planet in six short years.) Circumspection would have been prudent for Grassi and de Montebello: the Stoclet vendors had prepared a “four-inch thick” legal contract document and refused to allow the picture to be examined technically by the three big museums (the Met, the Getty and the Louvre) selected by Christie’s to bid in a private treaty sale. In 2003, the vendors had withdrawn the picture at the last moment from a big Duccio exhibition in Siena at which specialists would have had the first opportunity since 1935 to examine the picture – not one of the four Duccio scholars who had published monographic studies since 1951 had ever seen the picture which was known only by an old black and white photograph.

MARKETING “A LAST DUCCIO” AND “A LAST LEONARDO” AT CHRISTIE’S, NEW YORK

Above, top, Fig. 5: The Met Duccio as first photographed before 1904 (left); and as seen when sold in 2004.

Above, Fig.6: The disappeared $450 million Salvator Mundi as seen in c. 1913 (left); and as seen when sold at Christie’s, New York, in 2017.

In 1901 no one thought the tiny Madonna and Child (Fig. 5, above, left) a Duccio. Some thought it a Sano di Pietro. The picture had emerged after 1900 and, just like the Salvator Mundi (above, Fig. 6), it did so without provenance. It was said to have been found in a Tuscan antiques shop by Count Stroganoff, a Russian friend of Bernard Berenson and a big collector of “inediti” works that had not appeared in scholarly publications or exhibitions. Stroganoff had it restored and cradled. When, after buying it, Met conservators removed the cradle in 2005 (the year the Salvator Mundi was bought in a provincial U.S. sale for less than the low estimate of $1,200 – for $1,000 plus a $175 charge – it, as mentioned, having been turned down by Christie’s), they found that the panel’s originally gesso-ed back had been scraped down to the bare wood which bore a pencilled ascription to “Segna della Buoninsegna”, an apparent confusion between the Ducciesque painter Segna di Buonaventura and Duccio. In 1904 the head of the Uffizi Gallery judged it “in the manner of Duccio”. When an exhibition of early Sienese painting was held in 1904, a friend of Berenson’s, Carlo Placci, commended a late inclusion of Stroganoff’s recently restored picture which by then was incorporated within a larger frame bearing a metal plaque announcing a Duccio. Stroganoff had attributed his own antique shop purchase. Berenson’s circle would usher it into stardom at a time of considerable intellectual and financial crisis for the scholar – his principal source of income had dried; finding part-replacements for it were proving elusive; he had stopped writing. (Ironically, Berenson had held hopes until 1904 of finding employment as an advisor on Italian purchases at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

By 1904, as Frances Vieta discovered, Stroganoff had no fewer than eight similarly small gold background Sienese style panels, one of which was ascribed to Duccio’s follower Simone Martini and later bequeathed to the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. The “Simone Martini” had been dismissed in 1901 by the art historian Giorgio Bernardini as “so heavily restored in the skin tones, and in the red and blue robes, that it is not easy to attribute to anyone.” After seeing it at the Hermitage in 1929, George Martin Richter complained (Burlington Magazine): “Beneath this mantle there is concealed not an organically constructed body but a form rather suggestive of a bag full of washing.”

For all the Christie’s Hype, the Met had bought a Berenson Family-accredited pig in a poke. The museum came under challenge. In 1984 the now c. $50 million picture had been rejected by one of the Big Three Duccio Specialists, Florens Deuchler. ArtWatch International’s founder, Professor James Beck, wrote to the Met’s Chairman, calling for an inquiry and advising the museum to ask for its money back (see Beck’s, From Duccio to Raphael – Connoisseurship in Crisis, 2006, Italy, chapter 6 and Addendum). The Duccio pedigree, like that of the Salvator Mundi, is short, modern and precarious. The Salvator Mundi had no pre-20th century history. The Met’s official history of the Duccio begins not in 1901, when no-one considered it a Duccio, but in 1904 after it had been attributed by Bernard Berenson’s wife, Mary Logan (once), and (twice) by Berenson’s protégé, Frederick Mason Perkins, who trained in music, not art history. Christiansen elaborated: “from that point on the picture has held a central place in the Duccio literature”. Central, but with an unseen and unexamined work that had been dismissed by scholars on its six centuries-late emergence. The then 28-year old Perkins, is cast by Christiansen as a leading specialist in Sienese painting when Logan had written his first article and most of his first book.

Worse, as Vieta further established, Perkins was a fount of lucrative attributional errors. In 1923, he advised Helen Frick (then creating the incredible scholarly resource that is today’s Frick Research Library) to buy two huge marble sculptures from an antiques dealer for $150,000. He attributed these “wonderful” sculptural “masterpieces” to Duccio’s heir, Simone Martini. They had recently been made by the sculptor/forger, Alceo Dossena. Perkins’s fee was ten per cent. In 1933 he attributed an unpublished Madonna and Child surrounded by Angels to Duccio in an article carried in La Diana. The Belgian collector Adolphe Stoclet, the then owner of the now-Met Duccio, bought that second “Perkins Duccio”. In 1989 it was loaned to the Cleveland Museum of Art and there identified by Gianni Mazzoni, an Italian scholar of Sienese art and its forgers, as by the forger Icilio Federico Joni – which experience might have chilled the Stoclet family. Joni is known to have run a little factory of forgers whose works were put onto the market by middlemen, one of whom was Perkins himself. The lynchpin of Christiansen’s case for the “Met Duccio” is Berenson’s subsequent (private) hymning of the Stoclet picture as the loveliest and most characteristic thing Duccio ever did to the Duveen firm which paid him ten per cent on Italian purchases. Despite Berenson’s effusions, Duveen would not touch the “very small and ineffective” picture with a “nearly black” robe.

AN UNPUBLISHED TECHNICAL EXAMINATION AT THE MET

A top-secret post-purchase technical examination of the Duccio was carried out at the Metropolitan Museum. Staff were forbidden to talk to the press. No reports were published. The findings were discussed by Christiansen in the February 2007 Apollo. That article carried an x-ray of the painting showing modern, round-headed, wire nails underneath the picture’s ancient, badly distressed, “candles-burnt” gesso-ed frame. That hard, subversive material fact drew no comment (- other than ours in three consecutive issues of The Jackdaw, in 2008-09, as reprised in this post.) No comment was made, either, about the Met Duccio’s eccentric and pronounced craquelure. Scarcely less remiss than these “material” silences was the Met’s failure to acknowledge and address the uncharacteristically sloppy drawing of the figures, as revealed by infra-red imaging (see Fig. 7, below, centre).

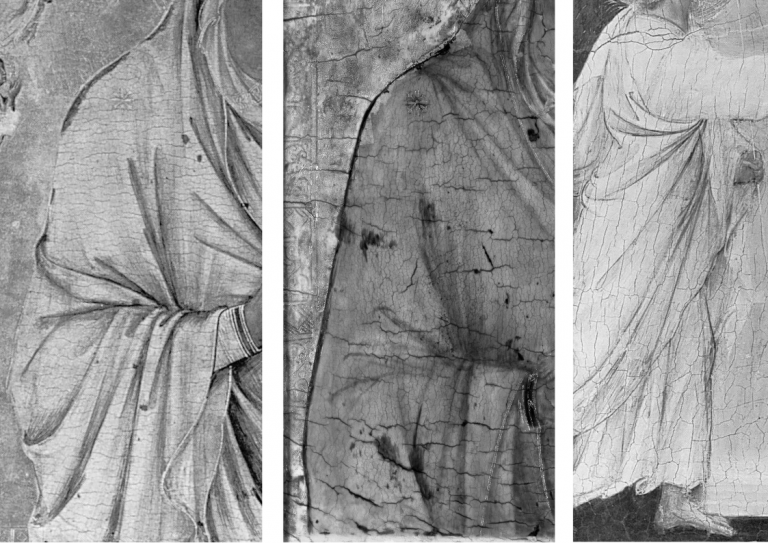

Above, Fig. 7: Left, an infra-red image of the National Gallery’s Duccio triptych (detail); centre, an infra-red image of the Met Duccio (detail); right, an infra-red image of the National Gallery’s indisputably Duccio panel, The Annunciation.

De Montebello, Christiansen and the Met picture restorer Dorothy Mahon travelled to London in autumn 2004 to view the Duccio at Christie’s. They were buying “blind” (unable to conduct technical examinations of the kind made on the other Stoclet/Perkins Duccio) and in knowledge that “the Louvre was working on trying to get the money together”. They spent an hour and a half at Christie’s where “The director made an offer for it on the spot”, and they all then went to see the National Gallery’s “rare and very beautiful Duccio triptych” – “a touchstone of Duccio’s work” (detail, above, left) so that the director “might assure himself that the two works were equivalent”. It would have been better to have gone to the National Gallery first, not only to see the triptych but to study its historical and technical dossiers, and those of the gallery’s absolutely secure Duccio Annunciation. Having bought the picture, all three “felt ‘ours’ was every bit as fine and in some respects more intimate and direct” than the triptych and was “a painting that represented the artist at the very height of his powers”. Two Duccio specialists, Deuchler and James Stubblebine, thought the NG triptych “Shop of Duccio: Simone Martini”.

Having thus bought very expensively without a trace of “buyer’s remorse”, other possible grounds for concern may have been overlooked. For example, Christie’s had won the right to conduct its private, three-museum sale by putting “a significantly higher valuation on the painting than anyone else – by multiples”, as Nicholas Hall, the international director of Christie’s Old Masters department, later told the New Yorker (Calvin Tomkins, “The Missing Madonna”, 11 July 2005). When Hall invited Christiansen (an old friend) to lunch to show him a recent transparency of the Stoclet Madonna, he was immediately smitten and proactive. As he later recalled: “‘Fantastic, how about the price?’ I asked. He told me. ‘OK,’ I said, ‘I will deal with that later,’ and then we finished our lunch.” (Danny Danziger, Museum – Behind the Scenes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2007.)

Had the Met officers opted to compare the under-drawing of the three works, as above, Fig. 7, before buying, they might have seen that on the quality of drawing one of the three was the other two’s inferior. If we think of the three images as a triptych, it is striking how much more fully and vividly realised the draperies and figures are as form in the two “wings”. Consider the left and centre under-drawing: in the outer image the drapery folds are not notionally indicated with lines that converge, as on the Met picture, but are realised, in anticipation, as autonomous three-dimensional folds and hollows that move over and around the implicit body within – one senses, for example, precisely where the unseen elbow is located, this being no “bag of washing”. The contour on the National Gallery Madonna’s outer edge is not depicted, as is the case in the Met picture, with a long un-lovely single continuous unbroken line of few deviations along which it is impossible to sense the elbow’s location. Rather, it is conceived and shown as a record of the points at which the forms and undulations of the cloth turn away from the viewer. Such differences of drawing speak of radically differing degrees of plastic/sculptural sensibility and comprehension. That on the left is greatly and decisively more sculptural, dynamically expressive, and plausible as a figure adjusting itself to support the weight of a child. Drawing has rightly been described as the probity of art and, as such, its study and evaluation must be considered one of the most pertinent and indispensable tools of critical analysis.

In the face of artistic weaknesses Christiansen blusters: “The drapery of the Virgin is astonishingly three-dimensional in the way it falls over the arm; it’s like a Roman sculpture.” All style judgements are relative: this is more, or less, or identical with, that. When drawing is weak, associated aspects often prove deficient. Viewing the triptych immediately after the Christie’s Duccio, Christiansen noted the former “struck a slightly different key than the picture we had been examining.” That difference, as the Met’s subsequent examinations disclosed, had a material basis. Ultramarine pigment was used in the triptych as opposed to the Met picture’s cheaper azurite. Moreover, the painted relief of the triptych’s ultramarine blue drapery was modelled not so much by progressive (and chromatically-debilitating – as Duveen had complained) dilution with white pigment, but by the addition of carbon black shading enriched by a red glaze – a tri-partite finish made with the best materials – and one that was emulated by Modestini on the background of the Salvator Mundi. Modestini has given two accounts of her actions. They both merit attention, because both are more detailed, and frank, than is commonly encountered in restoration reports.

REPLICATING HISTORICAL AUTHENTICITY TO PRODUCE A “DIFFERENT, ALTOGETHER MORE POWERFUL IMAGE”

Writing in a 2012 conservation report (see below), Modestini recalled:

“There were actually two stages of the current restoration. In 2008 when it went to London to be studied by several Leonardo experts, there was less retouching: I hadn’t replaced the glazes on the orb, finished the eyes, suppressed the pentimenti of the thumb and stole, and several other small details, but, chiefly the painting still had the mud-coloured modern background that was close in tone to the hair. Two years later I was troubled by the way the background encroached upon the head, trapping it in the same plane as the background. Having seen the richness of the well-preserved browns and blacks in the London Virgin of the Rocks”, and based on the fragments of black background which had not been covered up by the repainting, I suggested to the [then two] owners that it might be worthwhile to try to recover the original background and finish the incomplete restoration.

“I began to remove the overpaint mechanically under the microscope. Where it had been protected by the Verdigris [layer, that had been scraped off “at an unknown date and replaced by a mud-coloured background”], the original background was intact, and much of it survived under messily applied fill material. The difference between the original black and the modern brown was dramatic.

“The initial cleaning was promising especially where the Verdigris had preserved [because applied soon after?] the original layers. Unfortunately, in the upper parts of the background, the paint had been scraped down to the wood and in some cases to the wood itself. Whether or not I would have begun had I known, is a moot point. Since the putty and overpaint were quite thick I had no choice but to remove them completely. I repainted the large missing areas in the upper part of the painting with ivory black and a little cadmium light, followed by a glaze of rich warm brown, then more black and vermilion. Between stages I distressed and then retouched the new paint to make it look antique. The new colour freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair, and made a different, altogether more powerful image. At close range and under strong light the new background paint is obvious, but at only a slight remove it closely mimics the original.

“The retouching was done with time-tested materials.” Viz: “with dry pigments bound with PVA AYAB. Translucent water colours, mainly ivory black and raw siena, were used for final glazes and to draw [fake age] cracks. For the black background both AYAB and Maimeri Colori per restauro were used. Except for the background, I mainly used treble 0 sable watercolor brushes in a series of vertical passes until the area of loss matched the surrounding material.”

RESTORATIONS BEGET RESTORATIONS

In her 2018 memoir, Masterpieces, Modestini recalled:

“When the painting returned [in 2008 from London] to New York, I saw it on many occasions and became increasingly dissatisfied with my hastily concluded restoration. This is inevitable, especially when the painting is a damaged work by a great artist. Although I was aware of this, I itched to have it back. Leonardo’s [sic] Virgin of the Rocks in London had just been cleaned, and I made an appointment to see it. It is relatively well-preserved and, at that time, the only Leonardo that was not encumbered with centuries-old, thick, yellow, decayed coats of varnish like the Mona Lisa and the St John the Baptist in the Louvre. When I saw it, I was struck by the richness and depth of Leonardo’s blacks and realized that the principal problem of the Salvator Mundi was that the image was imprisoned by the nineteenth-century, sludge-colored repaint of the background. In a few areas, mostly around the contours of the figure, the original deep black was visible, and I knew from one [!] of the cross sections that Leonardo had paid great attention to it, building it up with four layers consisting of two different blacks, and black mixed with vermilion. I explained this to Robert [Simon], who immediately understood.

“For retouching [aka repainting] I use high-quality dry pigments, and I had a number of different blacks to work with – bone black, which Leonardo was known to favor, and a sixty-year-old tin of finely ground, pure ivory black that I had inherited from Mario [Modestini], which is no longer made. I had never used it but suddenly remembered Mario talking about how special it was…After I had polished and distressed my new paint, the result was reasonably satisfactory, at least when compared to the previous iteration. The difference it made to the painting was astounding: the great head surged forward and became much more powerful. I allowed myself to think that the decision I had taken was not so terrible after all. With the figure now more prominent and three-dimensional, some minor areas of loss and wear began to clamor for attention. This sequence is an essential part of the process of restoring a damaged painting.

“Luke Syson, the curator of the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition, asked to borrow the painting, notwithstanding some cavilling from colleagues about exhibiting a work that was on the market…”

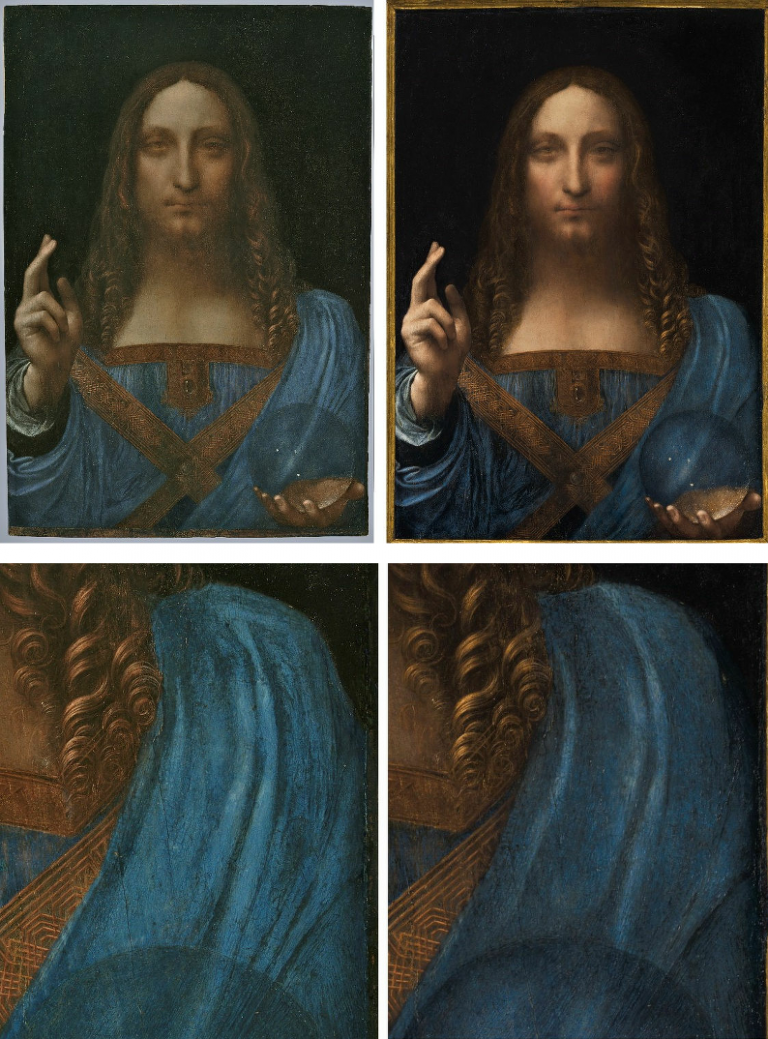

Where Modestini was licensed by the owners to act as a painter-in-arms with Leonardo, Christiansen downplayed the triptych’s greater richness of effects and materials by deeming it “Obviously…a deluxe object” made for a rich client as opposed to “the first owner of the Metropolitan’s [who] was also someone of wealth or social standing”. If the force of that distinction is not immediately apparent, there are other, no less telling, differences where cost is immaterial: the triptych’s under-drawing was made with a quill pen – the instrument said to be Duccio’s favourite. That of the Met painting was made with brush… Making repeated allowances for atypical traits is never reassuring. Modestini has disclosed that although the all-blue draperies of the disappeared ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi are of ultramarine, it is of low grade – as was the panel on which it was painted. (In 2019 Simon reported that the ultramarine had not undergone full purification and had retained large particles of quartz.) It has been claimed, as described below, that by some technical quirk, whenever the restored Salvator Mundi is re-varnished, the forms of the true left shoulder draperies expand or contract in numbers (see Fig. 8, below) precisely as occurred between 2011 when the picture was at the National Gallery, and 2017, when it was on offer at Christie’s.

ART WORLD CLOAK AND DAGGER

Above, Fig. 8: Left, top, and detail below left, the Salvator Mundi when exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12 as a long-lost autograph Leonardo painted prototype Salvator Mundi; right, top, and detail below right, the (disappeared) Salvator Mundi when offered in 2017 at Christie’s, New York, as a long-lost autograph Leonardo painted prototype Salvator Mundi with “an unusually strong consensus”.

In her 2018 memoir, Masterpieces, Modestini describes how the painting was brought to her place of work at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts’ Conservation Center in 2017:

“…I called [the Sandy Heller Group] immediately and was told the Salvator Mundi would be arriving in New York shortly and I was not to inform anyone. On Wednesday evening, July 19, the painting was delivered to the Conservation Center under guard and in great secrecy and was stored in the vault.”

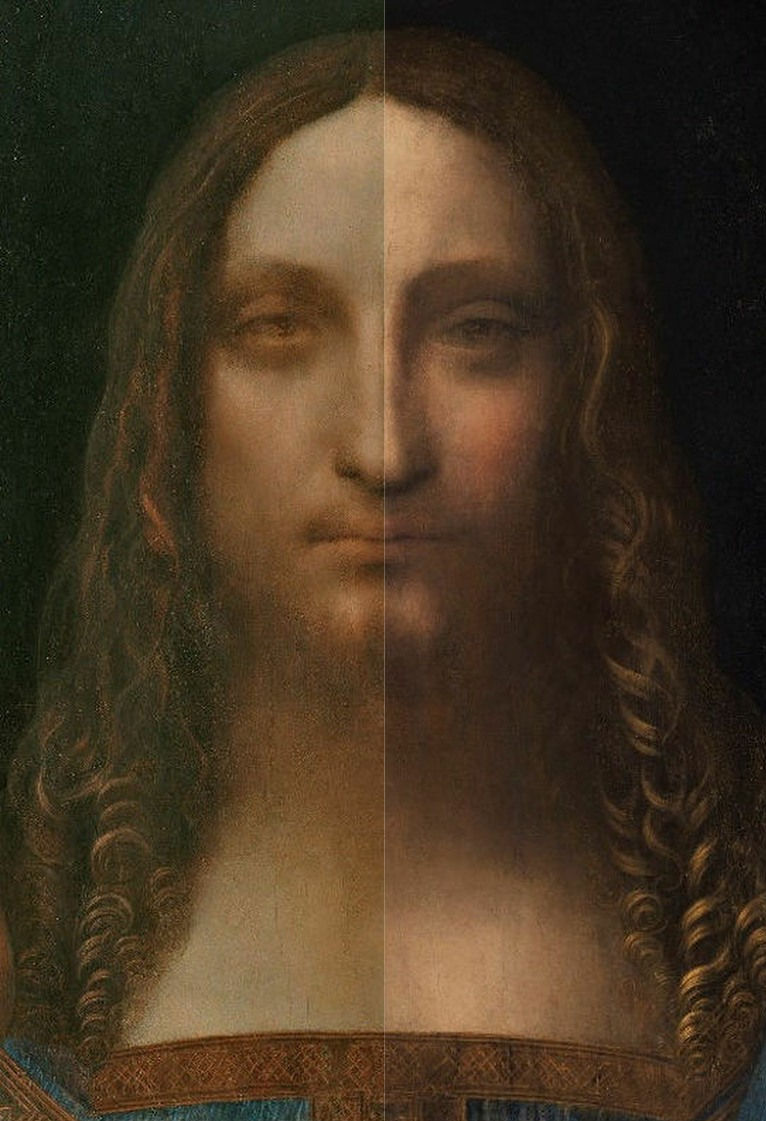

Why? Does Christie’s lack safe storage facilities? Modestini seems to have made preparations for the picture to be sent on its whistle-stop global promotional tour even though she does not approve of such risks being taken: “I had some concerns…A museum would not have agreed to this but the painting was on the market, and I realized that it was essential that prospective buyers in far-flung locations could examine it in person.” With a colleague, she “supervised the reframing and packing at Christie’s.” Why, and on whose authority was it sent to an academic institution, under guard and in great secrecy before being dispatched on its global tour? And, what happened to the painting between being stored in the Conservation Center’s vault and its being prepared for that world tour by Modestini, at Christie’s, New York? For Christie’s explanation of this episode, see Dalya Alberge’s “Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo Da Vinci painting which became world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in last five years”. The Christie’s spokeswoman said to Alberge: “Prior to its presentation for sale at Christie’s, Modestini partially cleaned the passage of paint in the shoulder and the dark streaks disappeared”. So, to disappearing books and catalogues, and paintings, must be added disappearing features within a disappeared painting. It is a pity that Modestini, while describing the manner in which the Salvator Mundi painting returned to her safe-keeping in NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, drew a veil over her own actions therein when writing her 2018 memoir Masterpieces. There are so many questions now dangling: “Why did a small painting that was cleaned in a day and had then undergone several campaigns of restoration over six-years between 2005 and 2011, receive further, covert, treatment just six years later? When Modestini first worked on the painting its varnish was “sticky”. Was it sticky once-more when sold for nearly half a billion dollars in 2017? The disappearances within the painting are one concern. Another is the differences between the picture’s appearance in 2011 when launched at the National Gallery as by Leonardo and its appearance in 2017 when offered to the world in a different guise at Christie’s, New York, as a National Gallery-endorsed miraculously discovered and recovered Leonardo. Those unexplained differences might seem encapsulated in our early split-halves composite image of Christ’s face (as shown below at Fig. 10) where there is a mismatch between the two halves. This Christ has had two faces in our times, the later one with more colour in the cheeks and more focussed eyes. Clearly, both cannot be taken as recovered authentic faces, so the real and urgent question is: Should either of them ever have been presented as Leonardo’s own work?

Above, Fig. 9: Top, left, the Salvator Mundi, c. 1913, when in the Cook Collection; top right, the Salvator Mundi as catalogued by the St Charles Gallery, New Orleans, as “After Leonardo da Vinci” for the April 9-10 2005 sale. Above, left, the Salvator Mundi as taken to the restorer, Dianne Modestini in April 2005 (with a still sticky varnish); right, the picture in May 2008 when about to be taken by Robert Simon (as above) to the National Gallery for a (confidential) examination by a small and select group of Leonardo scholars, after the first stage (as described above) of Modestini’s restorations .

Above, Fig. 10: Left, the ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi face, as exhibited in 2011 at the National Gallery; right, the ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi face, as offered at Christie’s, New York, in 2017.

A POST HOC SALVATOR MUNDI LITERATURE

As will be examined in Part II, our challenges to the perpetually mutating and “improving” Salvator Mundi were made: a) within days of its November 2011 launch at the National Gallery; b) nearly a month before Christie’s November 2017 sale; c) five days before Christie’s 2017 sale; d) the day before Christie’s sale; and, subsequently, e) in nearly a score of posts – see Endnote below. The undisclosed identity of the original owners was only uncovered in September 2018 (by The Washington Post). Until that date and disclosure, the true purchase price in 2005 was exaggerated ten-fold by both the original owners and the painting’s advocates -and therefore in all press reports over a thirteen-year period. The publication of researches that had been promised in 2011 by the owners and by the National Gallery did not occur until 2019 and, even then, it was not in full.

Four recently published books now comprise a small, belated literature on the rise and demise of the long-unloved Leonardo School work that morphed into the world’s most expensive and least visible picture. They were: Living With Leonardo – Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond, by Professor Martin Kemp, London, 2018; Masterpieces (“Based on a manuscript by Mario Modestini” and with informative chapters on: the Salvator Mundi; Cleaning Controversies; and, Misattributions, Studio Replicas and Repainted Originals) by Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Italy, 2018; The Last Leonardo – The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, by Ben Lewis, London, 2019; and, Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & The Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts, by Margaret Dalivalle, Martin Kemp, & Robert B. Simon, Oxford, 2019.

Until those four works appeared, the literature consisted of the catalogue entry “Christ as Salvator Mundi, about 1499 onwards” in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition catalogue by its curator, Luke Syson; and, Dianne Modestini’s account of the Salvator Mundi’s restoration and art historical credentials that was delivered in January 2012 at a National Gallery conference and published in 2014 as “The Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci rediscovered History technique and condition” in Leonardo da Vinci’s Technical Practice, Paintings, Drawings and Influence, Ed. Michel Menu, Paris. Both Syson’s and Modestini’s accounts acknowledged indebtedness to the private researches of one of the picture’s owners, the New York dealer, Robert Simon.

Specifically, Syson declared in 2011: “This discussion anticipates the more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others. I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and, (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be published in a forthcoming book.” In 2014 Modestini acknowledged having benefited from “…the knowledge and good eyes of Robert Simon with whom I worked closely on the restoration for six years and who generously shared with me the results of his research for this paper. I am especially indebted to Nica Gutman Rieppi, Associate Conservator in the Kress Program at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, who took the samples, made the cross-sections and coordinated the analytic work which was carried out with great thoroughness, precision and dedication by Beth Price and Kenneth Sunderland, research scientists at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with the help of Dr Thomas J. Tague of Broker, Billerica, Massachusetts who carried out the ATR FTIR analysis of the sizing.”

That research had still not been published in 2013 when the picture was sold privately and under (Simon has revealed) a non-disclosure agreement through Sotheby’s for $80 million. The research had not been published by 2017, when Alan Wintermute of Christie’s wrote (in “Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi”, one among other endorsing/bolstering essays by Frances Russell, Dianne Modestini, David Franklin and David Ekserdjian, in the auction house’s 2017 Salvator Mundi book/catalogue): “The reasons for the unusually uniform scholarly consensus that the painting is an autograph work by Leonardo are several… The present painting, although only recently discovered, has already been extensively studied, with a remarkable campaign of research lead by Dr. Robert Simon. The most insightful and broad-ranging examination of the painting was presented by Luke Syson in the 2011 catalogue of the Leonardo exhibition in London. The following discussion depends heavily on Dr. Syson’s entry, which itself drew on the unpublished research made available to him by Robert Simon, Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi, Martin Kemp and, for the picture’s provenance, Margaret Dalivalle…” Having thus drawn the scholarly research wagons around the picture (and the auction house) Wintermute disclosed that the still-unpublished researches by Dalivalle, Kemp and Simon would not be published until 2018 – which was to say, a full seven years after the painting had been declared and exhibited as a Leonardo, at the National Gallery. In the event, and even with its pared-down authorship (see below), the book would be further delayed until 2019, by which date the mystery over the subsequently disappeared picture’s ownership and whereabouts had deepened yet further.

The Simon Researches had originally been earmarked for a book of essays to be published by Yale University Press and sold at the National Gallery’s “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan” exhibition. That book proved to be the first on this Salvator Mundi picture that failed to materialise. Reasons for its demise were volunteered by Professor Martin Kemp in his Living with Leonardo:

“Robert [Simon] thought it was a good idea to publish a book of essays by various authors, including Margaret Dalivalle and myself. Yale University Press, which does not normally publish monographs on single paintings, was signed up as publisher. I was happy to go along with this, while expressing reservations about a volume with multiple authors being finished on time. Academics are notably adept at missing deadlines, and I was unconvinced that all the authors actually had anything new to say… In the event the complete book was not delivered and, deprived of the rationale of selling a good number of books at the time of the show, Yale withdrew.”

A GOOD SHEPHERD, AN UTTERLY FANTASTIC CONSENSUS AND A DONE-DEAL

The long-promised book of essays emerged in 2019 (through Oxford University Press) as the Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon compilation – but without a proper technical account of the picture’s campaigns of restoration and technical examination. Simon presents the book as “the first to treat the subject monographically” and “the first complete analysis of this essential addition to Leonardo’s oeuvre”. The authors liken their authorially-trimmed exercise to a three-act opera with each act constituting an in-depth facet of the story while “necessarily bypassing many ancillary issues”. The first act is said to chronicle the painting’s “journey from anonymity in America, with no provenance and in severely compromised condition, to its public revelation as a work by Leonardo at the exhibition in London. The six-year process of research and conservation is related by Robert Simon, who shepherded the Salvator Mundi on this remarkable journey…” When Simon took the painting to London in May 2008 (Fig. 9, above) to show it to a select group of Leonardo scholars assembled at the National Gallery, he made a good and lasting impression on Martin Kemp who, in his 2018 memoir, underscored Simon’s decisive role in the institutionally and ethically problematic attribution upgrade:

“…A general discussion followed. Robert Simon, the custodian of the picture (whom I later learned was its co-owner), outlined something of its history and its restoration. He seemed sincere, straightforward and judiciously restrained, as proved to be the case in all our subsequent contacts. We looked, we talked and we looked again. It was a remarkable occasion. By the time I left, I was determined to research every aspect of the Salvator Mundi. It seemed at first sight to resonate deeply with key aspects of Leonardo’s science of art, and his views of the role of God in the cosmos.

“I remained in touch with Robert Simon who is strongly committed to scholarly research. I learned that the eloquent painting we had viewed was in fact one of the known versions of the Salvator Mundi, formerly in the Cook Collection – previously heavily overpainted, it had now been cleaned and retouched. It had never before received serious attention; we had paid only passing attention to the black and white photograph of it [Fig. 6] that had occasionally been used as an illustration…

“All of the witnesses in the gallery’s conservation studio were sworn to confidentiality [by whom?] and the painting travelled back to New York with Robert. It was becoming ‘a Leonardo’ […and later: ‘Robert quietly introduced the Salvator Mundi to a judicious selection of experts, who – remarkably, given the usual leakiness of the art world – kept their counsel for three years. By the time the painting emerged in public there was a critical mass of influential voices who would speak in the painting’s favour.’]

“…Was it on the market? Would exhibiting it mean that the National Gallery was tacitly involved in a huge act of commercial promotion? It seemed highly likely that it was also ‘in the trade’. All I knew at this stage was that it was being represented by Robert Simon. He told me that it was in the hands of a ‘good owner’ who intended to do the right thing by it, and I did not enquire further. I was keen to consider the painting in its own right, not in relation to ownership. I speculated, of course, that Robert might have a financial interest, perhaps a share in its ownership, and I assumed he was gaining some kind of legitimate income from his work on the picture’s behalf…

“It was, however, a great surprise to find that the Salvator was to be sold at Christie’s in New York on 15 November 2017 in a mega-auction of celebrity works of art from the modern era. The auctioneers sent the painting on a glamorous marketing tour of Hong Kong, San Francisco and London. I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.”

TIGHT LIPS

The anonymity of which Simon spoke was a self-imposed, prolonged tactical ploy. In 2013, the three art dealing co-owners, Alexander Parish, Robert Simon and Warren Adelson (who in 2010 bought a one-third share for $10 million, thereby giving Simon and Parish a ten-thousand-fold return in five years on their $1,000 purchase), realised that because it was known within the opaque but gossipy art trade that the picture was being offered to museums, it would be too risky to put it to public auction: “there’s not a deader-in-the-water [thing] than a picture which you put up for auction and which then bombs”, Parish told Ben Lewis: “Supposing we had put a pretty reasonable price on the Salvator Mundi – let’s say we put a $100 million reserve on it – and it tanked, where do you go from there? Absolutely dead.”

The unidentified consortium of owners had other needs for opacity. Again, Parish to Lewis: “We’re a little opaque as to the date and location of acquisition. We purposefully have never corroborated Louisiana as the place where we bought it. And I’m not going to now. Why? Because some grandson of whoever these people are who sold it is going to decide, ‘Oh, that’s my $450 million picture. Who can I sue?’” Parish identified a third danger in professional transparency: “Part of the reason for the secrecy was the mechanics, if you will, that Bob [Simon] had to employ to get the utterly fantastic consensus that he compiled. Because in academic realms, if A says yes, B’s going to say no, just to be a dick. It’s not unheard of that certain experts are contrarian just because an opposing expert has said something else.” That last may sometimes occur but witnessing such spats enables the scholarly and art market communities to gauge the relative strengths of competing or conflicted argument and evidence. In art attributions and art restorations, as in law and in politics, things work better when propositions, expertise and evidence are subject to open appraisal and interrogation. Syson’s exclusion from the May 2008 National Gallery examination of the two leading Leonardo specialists most likely to respond negatively to the picture drew Lewis’s attention and is discussed below. The National Gallery’s preference for a select group of experts was disclosed by Kemp in 2018 when he published his March 2008 invitation to the event from the National Gallery’s new director, Nicholas Penny:

“I would like to invite you to examine a damaged old painting of Christ as Salvator Mundi which is in private hands in New York. Now it has been cleaned, Luke Syson and I, together with our colleagues in both painting and drawings in the Met, are convinced that it is Leonardo’s original version, although some of us consider that there may be [parts] which are by the workshop. We hope to have the painting in the National Gallery sometime later March or in April so that it can be examined next to our version of the Virgin of the Rocks. The best-preserved passages in the Salvator Mundi are very similar to parts of the latter painting. Would you be free to come to London at any time in this period? We are only inviting two or three scholars.”

TWO OF A KIND

Note: the claimed similarities between the two supposed autograph Leonardo pictures would once have weighed heavily against the Salvator Mundi. A former director of the National Gallery and a Leonardo specialist, Kenneth Clark, had said of the gallery’s version of the Virgin of the Rocks “A pupil did the main work of drawing and modelling, and before his paint was dry, Leonardo put in the finishing touches. Most of these have been removed from the Virgin’s face but remain in the angel’s, where perhaps they were always more numerous” – see “The National Gallery’s £1.5 Billion Leonardo Restoration”. As for claims of the Cook Salvator Mundi being a long-lost prototype-for-all-other-versions, Clark judged it “one of the versions ‘less close to the [presumed] original’”. He attended the 1958 sale at Sotheby’s where this very Salvator Mundi version limped away for £45 to the United States, and hence, eventually, to Louisiana in 2005, where it would draw just two bids and fetch its $1,000 plus $175 charges – thus, below the picture’s low estimate of $1,200. Even with the overheads of a castle to find, Clark had money to spend on art. As he reported to Bernard Berenson: “In a fit of madness I even bought some pictures at the sale of the remnants of the Cook Collection, including a very beautiful Alonso Cano of Tobias and the Angel, and a Giulio Romano; also a splendid Granet. They were sold for the price of a small Cézanne pencil drawing…” (Letter, 14 July 1958, in My dear B. B. The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Kenneth Clark, 1925-1959, ed. Robert Cumming, Yale University Press, New Haven and London.)

THE NATIONAL GALLERY’S SHOW-CASING WITH EXTRA OOMPH

Four months before its 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition the National Gallery defended its decision to include the undocumented privately-owned painting as “an important opportunity to test this new attribution”. Had the painting been included on precisely those terms and shown when cleaned and not-yet restored few would have complained at an opportunity to see a recently discovered version of the Leonardo school Salvator Mundi. That did not happen. It did not happen because Penny had become an instant partisan of the proposed upgrade and was advising Simon on building a necessary consensus of scholarly support for the picture when, all the while, the picture was undergoing transforming campaigns of restoration in accordance with Simon’s (anthropomorphising) conviction that the picture should be allowed to “live once again as a work of art”. Instead of a disinterested display of the work “as-was” after cleaning and before restoration, the Gallery exhibited it after multiple bouts of restoration, the second of which was made in declared emulation of the National Gallery’s own (questionable) version of The Virgin of the Rocks, as a miraculously recovered and, supposedly “long-lost” Leonardo. Begging a monumentally large question of attribution in this manner was a plain abuse of institutional authority and – given the picture’s fanciful and preposterously bloated provenance – a gross misrepresentation of the historical record to boot.

When Ben Lewis asked Luke Syson why the work had been catalogued unequivocally as a Leonardo, he replied: “I catalogued it more firmly in the exhibition as a Leonardo because my feeling at that point was that I was making a proposal and I could make it cautiously or with some degree of scholarly oomph. It is important not to float an idea without saying where you yourself stand on it.” Syson was standing on a house of (double-borrowed) cards. When the exhibition opened on 9 November 2011 our first objection was published within days – see Figs. 11 and 12 below.

Above, Fig. 11: Left, a detail of 1650 etched copy by Wenceslaus Hollar of a painting then attributed to Leonardo that was being claimed to be a record of the Salvator Mundi version in the National Gallery; right, ArtWatch UK letters contesting the attribution on the absence within the painting of optical features recorded by Hollar.

Above, Fig. 12: Left, a detail of the Salvator Mundi as it was immediately before its disappearance in 2017; right, top, AWUK diagrams highlighting many optical differences between the Hollar copy and the painting exhibited at the National Gallery.

SCHOLARLY RESPONSES TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY’S LEONARDO ATTRIBUTION

In the event, the Leonardo attribution was publicly challenged by at least four scholars in reviews of the 2011-12 National Gallery exhibition. Carmen Bambach, of the Metropolitan Museum and author of the major 2019 four-volumes Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered, rejected the Leonardo attribution in a 2012 Apollo review of the National Gallery exhibition and gave the painting to Leonardo’s student Boltraffio (with possible modifying touches by Leonardo). Frank Zöllner of Leipzig University and author of the Leonardo catalogue raisonné, Leonardo da Vinci – The Complete Paintings (Bibliotheca Universalis) had said ahead of the exhibition that the proportions of the nose were “too long” for such a perfectionist as Leonardo and were more likely to have been painted by a talented follower. When the late husband of the restorer, Mario Modestini, first saw the Salvator Mundi he thought it by a very great artist a generation after Leonardo.

Later, in the revised 2017 edition of his book, Zöllner said of the ex-Cook Salvator Mundi that while it surpasses the other known versions in terms of quality, it: “also exhibits a number of weaknesses. The flesh tones of the blessing hand, for example, appear pallid and waxen, as in a number of workshop paintings. Christ’s ringlets also seem to me too schematic in their execution [Fig. 6, above], the larger drapery folds too undifferentiated, especially on the right-hand side [Fig. 8, above]. They do not begin to bear comparison with the Mona Lisa, for example. It is therefore not surprising that a number of reviewers of the London Leonardo exhibition initially adopted a sceptical stance (Bambach 2012; Hope 2012; Robertson 2012; Zöllner 2012). In view of the arguments put forward to date and the above-mentioned weaknesses, we might sooner see the Salvator Mundi as a high-quality product of Leonardo’s workshop, painted only after 1507, on whose execution Leonardo was substantially involved. It will probably only be possible to arrive at a more informed verdict on this question after the results of the painting’s technical analyses have been published in full (Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2017).”

As seen, the Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon account did not materialise until 2019. Recently, Professor Charles Hope, former director of the Warburg Institute, pinned the scholarly nub in the London Review of Books (“A Peece of Christ”):

“Many of those who specialise in making such attributions have great confidence in their own judgment, even when this has proved fallible, and they tend to discount or give a tendentious spin to documentary evidence and information about provenance that does not fit with their theories.”

In 2017, Christie’s, New York, cited fifteen scholars as supporters of the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo ascription. They were:

Mina Gregori, Nicholas Penny, Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Carmen Bambach, Andrea Bayer, Keith Christiansen, Everett Fahy, Michael Gallagher – the Met’s head of picture restoration, David Allan Brown, Maria Teresa Fiorio, Martin Kemp, Pietro C. Marani, Luke Syson, David Ekserdjian and Vincent Delieuvin.

One, Carmen Bambach, as seen above, had rejected the ascription in 2011. As also seen above, another, Delieuvin, has now downgraded the picture to a school work. Crucially, none had supported the attribution in a scholarly publication or forum, and several would disavow their inclusion in this list. When Lewis spoke to the select and confidential group of five Leonardo scholars invited to see the Salvator Mundi at the National Gallery (Pietro Marani, Maria Teresa Fiorio, Carmen Bambach, David Alan Brown and Martin Kemp), he discovered that only two had committed to a Leonardo attribution; two had declined to express an opinion; and one had rejected it.

Moreover, Lewis noted two striking omissions from the event that would likely have tipped the balance. One was our colleague, Jacques Franck, a Leonardo expert who had advised Syson on the restoration of the National Gallery’s version of the Virgin of the Rocks – much as he had done at the Louvre with its Leonardo restorations. Like others, Franck identifies two authorial hands in the Salvator Mundi picture, but he sees no participation by Leonardo in the painting – see his “Further thoughts about the ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi” and our “The Louvre Museum’s bizarre charge of ‘fake information’ on the $450 million Salvator Mundi”.

The second was Frank Zöllner, who then had recently written within his catalogue raisonné of Leonardo’s paintings: “In conclusion, mention must be made of the increasing attempts, above all in recent years, to attribute second- and third-class paintings to Leonardo’s hand. In this context it should be noted that the catalogue of paintings presented here is definitive. While there may be works circulating in the fine art trade that stem from Leonardo’s pupils, the likelihood of an original by the master himself ever making a new appearance is extremely small.”

Syson admitted to Lewis that Zöllner’s omission had been a mistake but justified Franck’s exclusion on the grounds that as a trained painter he was “too far outside the world of academic and institutional art history to be invited in to this project”.

Michael Daley, Director, 12 (& 24) August 2020

In Part II, we outline reasons why it might sometimes be of assistance to scholars and curators to heed the views of artists.

Endnote: ArtWatch UK Posts on the Salvator Mundi:

14 November 2017, “Problems With the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi, Part I: Provenance and Presentation”

1 January 2018, “The $450m New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi, Part II: It Restores, It Sells, Therefore It Is”

20 February 2018, “A Day in the Life of the New Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s Pricey New Leonardo Salvator Mundi”

27 February 2018, “Nouveau Riche? Welcome to the Club!”

11 March 2018, “In Their Own Words: No. 3 – The Reception of the First Version of the Leonardo Salvator Mundi”

29 March 2018, “Startling Disclosures on the Re-re-restored Leonardo Salvator Mundi”

10 April 2018, “The Leonardo Salvator Mundi Saga: Three Developments”

9 August 2018, “Leonardo Scholar Challenges Attribution of $450m Painting”

18 September 2019, “How the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi became a Leonardo-from-Nowhere”

11 October 2018, “Two Developments in the No-Show Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi Saga”

12 November 2018, “The Pear-Shaped Salvator Mundi”

6 February 2019, “The Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Not ‘Pear-Shaped’ – ‘Dead-in-the Water’”

22 February 2019, “The Louvre Museum’s Bizarre Charge of ‘Fake Information on the $450 million Salvator Mundi’”

4 July 2019, “Salvator Grumpi – updated”

20 September 2019, “Forthcoming events: The Ben Lewis Salvator Mundi Lecture and the new ArtWatch UK Journal”

28 October 2019, “The non-appearing, disappeared, $450million, now officially not-Leonardo, Salvator Mundi”

15 November 2019, “Books on No-Hope Art Attributions”

5 & 11 February 2020, “The Saviour and a Stealth-Attribution”

3 August 2020, “Further thoughts about the ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi”