The Notre-Dame Cathedral inferno was not an act of God. It arose within a particular restoration programme under a singular (ambivalent) French heritage ethos that has spawned many fires – these include, as our colleague Michel Favre-Felix of ARIPA (Association Internationale pour le Respect de l’Intégrité du Patrimoine Artistique) points out: interventions on the roof of Saint Pierre cathedral in Nantes which had led to a similar blaze disaster in 1972, and, in the very same conditions again, on Nantes’ basilica Saint Donatien in 2015; a fire caused by repairs that had threatened Amiens’ cathedral in 1987; and, a severe roof fire that destroyed unique paintings in the Hôtel Lambert, an architectural jewel of the XVIIth century in Paris, during its controversial restoration in 2013.

In the wake of the shocking cataclysm in Paris, joining up restoration’s conflagration dots seems more urgent than ever. The pattern of occurrences and reoccurrences is not confined to France. Collectively it might all be taken to reflect gross international laxity in today’s heritage stewardship regardless of administrative systems. Consider the circumstances of the following seven fires.

CASE 1: NOTRE-DAME CATHEDRAL, PARIS

See various comments below.

CASE 2: NOTRE-DAME CATHEDRAL, LUXEMBOURG

On 5 April 1985, welding work caused a fire in the belfry of Luxembourg’s Notre-Dame Cathedral’s west tower which then collapsed, destroying the bells and part of the roof. It was repaired within the year.

CASE 3: WINDSOR CASTLE

The United Kingdom, under less centralised heritage management than France, is scarcely less fire-afflicted. In 1992 the Great Fire at Windsor Castle (above) occurred when picture restorations were taking place in the Queen’s Private Chapel. A number of accounts of the cause were given but all contained a lamp, a curtain and picture restoration paraphernalia. The outcome was a fire-gutted chapel that cost £36.5 million to repair and reconstruct as closely as possible to “as was”.

Grievously damaged ancient buildings often unleash anti-history, would-be “modernising” impulses. Today, at the Notre-Dame Cathedral, President Macron, already a self-styled political Jupiter (who was possibly still in school shorts when the Louvre sprouted its pyramid), instantly assumed the role of Style King and licensed the modernisers by plucking an arbitrary five-year target date to rebuild Notre-Dame with the inducement “an element of modern architecture could be imagined” and the accompanying assurance that such a recreation will be even better than before (“more beautiful”). In consequence, war has broken out already between those who would make good the injuries and return the cathedral to its pre-conflagration state and those who would insinuate today’s professionally-dominant tastes and anti-style predilections. (The unfolding of that important debate merits separate examination.)

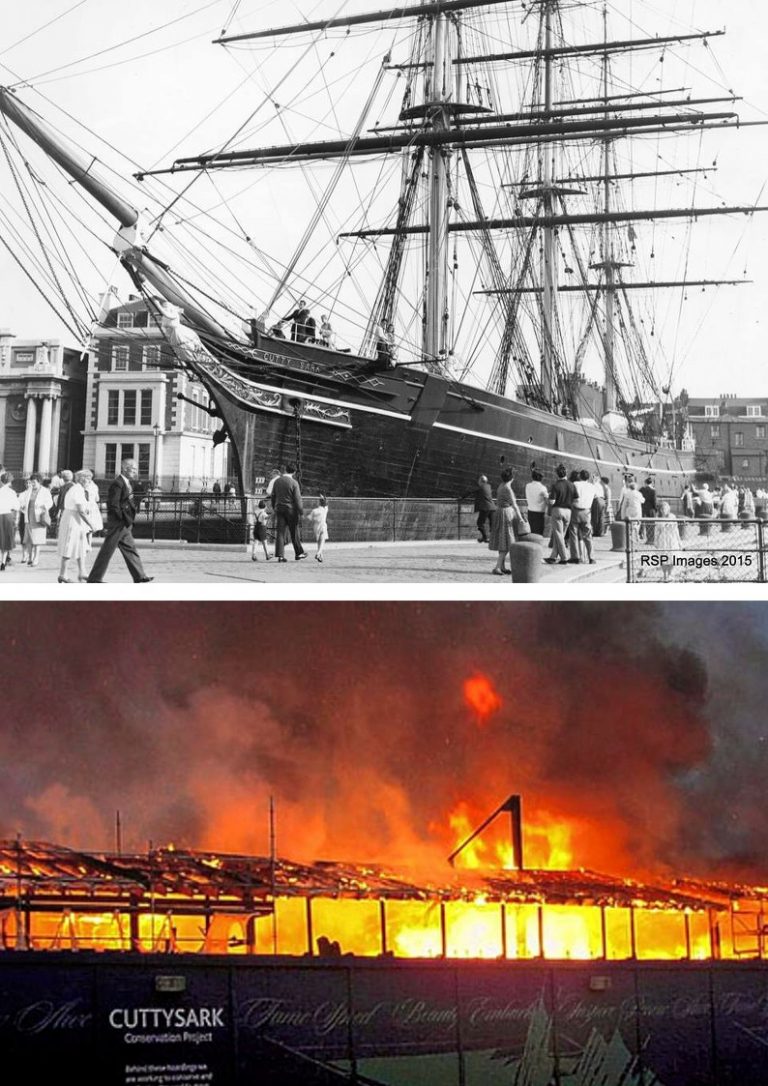

CASE 4: CUTTY SARK

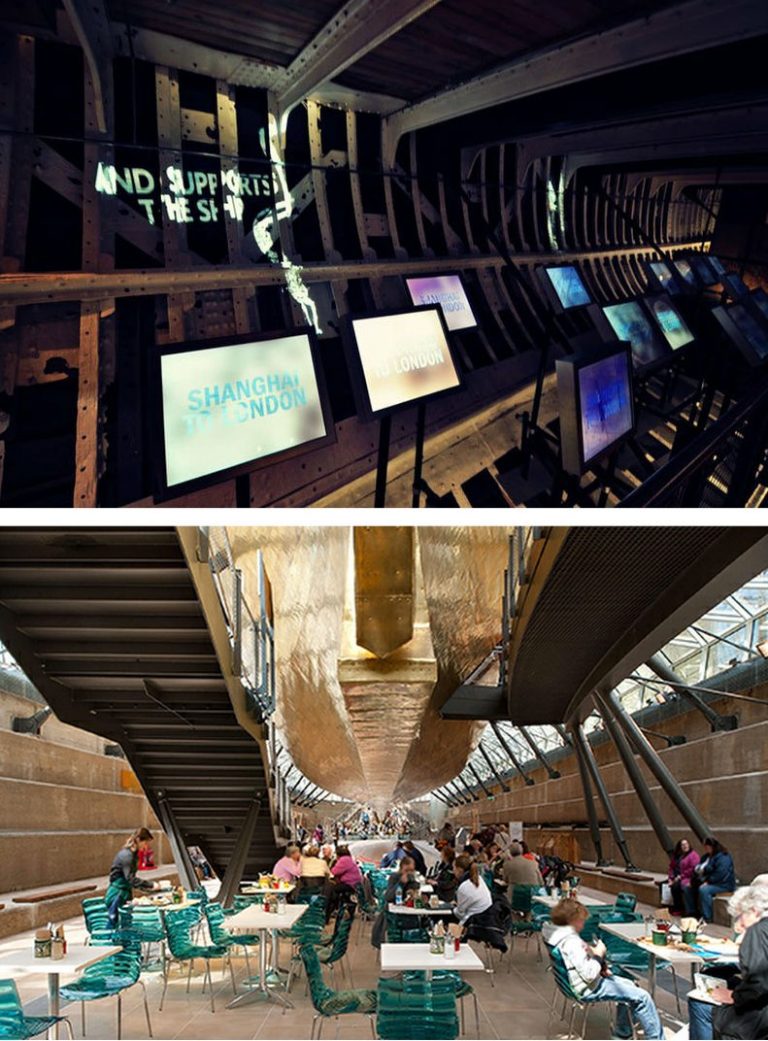

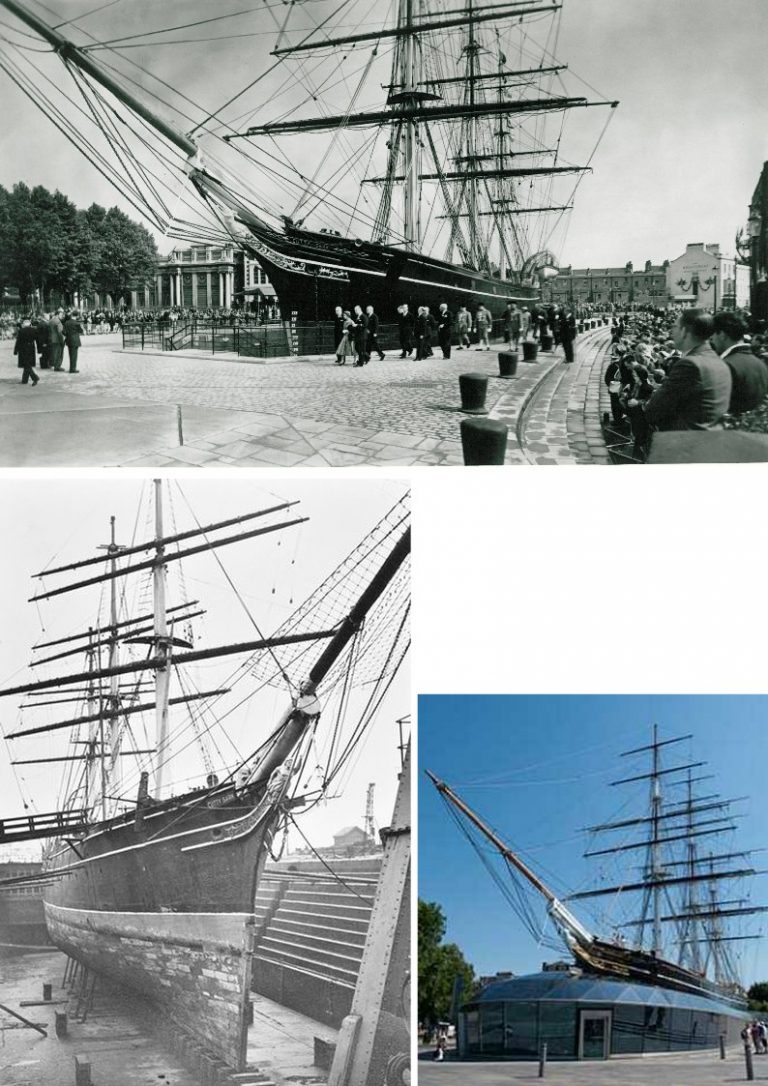

On 21 May 2007, the famous tea clipper, the Cutty Sark, was gutted by fire during restoration (above) at Greenwich. The ship’s sprinklers had been removed for the duration of the renovation. No fire alarm went off. The fire burned through all three decks, destroying all the building work structures and tools onboard. A planned £25 million renovation then became a transforming “more than £50m” rebuild that took two extra years. The ship – a globe-traversing maritime Concorde of its day – was left too weakened to support itself in water. Against highly expert advice from within and without the project, it was then raised off the ground and entombed on stilts within a modernist architectural techno-swank steel and glass structure covering a dry dock that had become a themed visitors’ centre (£13.50 entrance). This new ship/building hybrid (below) presents to the world as a sagging turquoise conservatory with a part-visible boat on top and is set in a sanitised, municipalised space with not a drop of water or a single bollard in sight:

Within this modernist makeover visitors are denied the opportunity to see real artefacts like the ship’s historic log books and instead are offered electronic “interactivity” (shaped, as always, by unseen programmers and their unexamined agendas) and off-ship catering facilities:

PHILISTINE POLITICAL GRANDSTANDING

In February 2010 the super-sleuth journalist, Andrew Gilligan, reported in the Telegraph that the then Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, had promised that the Cutty Sark, already in restoration since 2006, would be “brought back to its former glory” in time for the Olympics. “It will be yet another jewel for visitors in 2012 to enjoy,” Mr Brown predicted, notwithstanding the fact that the project’s chief engineer, Peter Mason, had resigned on grounds that the restoration should be “stopped and reviewed” because it will “damage the fabric of the ship” and could cause it to fall apart. The project had run massively late and over-budget and its main backer, the Heritage Lottery Fund, had cut off payments for most of a year amid “serious concerns” over the “governance and financial controls” of the restoration project. Prime Minister Brown, however, very much inclined to equate high-spending with “investment-in-the-future”. The Olympic Games opened in July 2012. The Cutty Sark was finally reopened four months later in November 2012 by Her Majesty the Queen, for whom the occasion might have seemed like deja vu all over again.

No one will ever again see the sleek majesty of the hull and its great projecting bowsprit rising above a body of water, as above, top, when first arriving in Greenwich in 1954 and, left, when opened by the Queen in 1957, and below, top, when opened by the Queen, and left, when resting on its keel in dry dock.

BORN FREE, FREE AS THE WIND BLOWS…

While the spirit of the ship may live on in the imagination, and in depictions, as above, the vessel itself will never again move in response to a breeze or see water. She is frozen permanently and propped (perilously, perhaps) in modernist aspic, sans water, sans buoyancy, sans motion, sans mobility. She now has no natural flexibility in the face of high winds which will inescapably subject her greatly weakened hull to unequal and un-natural stresses and tensions. She has literally been left high and dry. Ships are built from the bottom upwards on their keels. They can support themselves on their keels in dry docks with surprisingly few steadying props but Cutty Sark has been hoisted in the air and held entirely aloft on props around her hull. The fire-weakened vessel’s full weight now rests entirely on those props. The consequences of a possible second fire amidst the catering facilities do not bear thinking about.

CASE 5: GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART

Above, as reported by the Mirror, the June 2018 conflagration – the second burning down of Charles Rennie Macintosh’s Glasgow School of Art – occurred towards the end of the restoration that followed the May 2014 fire. That restoration had cost £36million. It was said to have been caused by an unattended continuous slide projection unit forming part of a student’s final year exam presentation. As with the Cutty Sark, the art school’s sprinkler system had been removed during the second restoration. The second fire was found to have been started by oily rags. Such materials are a known fire hazard: when stored in restricted spaces where heat cannot dissipate they self-combust. A spokesman for the British Automatic Fire Sprinkler Association has said that while automatic fire sprinklers had not been fitted while the building was undergoing restoration, “it should be realised that sprinklers can be fitted in buildings throughout construction on a temporary basis, as there is a considerable risk from fire during this period”. Not only had a new or a temporary sprinkler system not been installed, the removal of the old sprinklers, as the BBC reported on 17 January 2019 (“Fire expert ‘puzzled’ over art school mist system”) had itself been found mystifying:

“Holyrood’s culture committee has been taking evidence on the circumstances surrounding the second blaze. On Thursday it heard from independent fire, security and resilience adviser Stephen Mackenzie. Speaking about the equipment, which relies on cooling mist to extinguish flames, committee member Tavish Scott asked Mr Mackenzie: ‘The committee wasn’t told it was removed after the first fire and we are all puzzled as to why it would have been removed. Why would it have been removed?’ Mr Mackenzie said: ‘I’m also puzzled as an expert.’” The second rebuild is expected to cost £100million.

COMMON CAUSES

The Cutty Sark fire was found to have been caused by a blocked industrial vacuum cleaner that was left switched on and unattended over a weekend. Investigation found that unattended electrical equipment was often left plugged in; that there were loose electrical connections on the site; and, that building work debris was not removed immediately. In short, the fire had broken out and run out of control because of grossly bad practices and truly rotten management. Security guards first failed to carry out patrols and spot the start of the fire and then falsified their log book – see “Vacuum cleaner caused £10 million pound Cutty Sark fire as guards slept.

CASE 6: CLANDON PARK

Faulty electrics were said by a fire officer to have caused the devastating spontaneous (albeit not restoration-linked) fire, above, that gutted Clandon Park and its contents in 2015: “The cause of the fire was a faulty connection in the fuse board…We believe a lack of fire protection to the ceiling of the electrical fuse cupboard allowed the fire to spread quickly to the room above, and it then spread throughout the house owing to its historic design.”

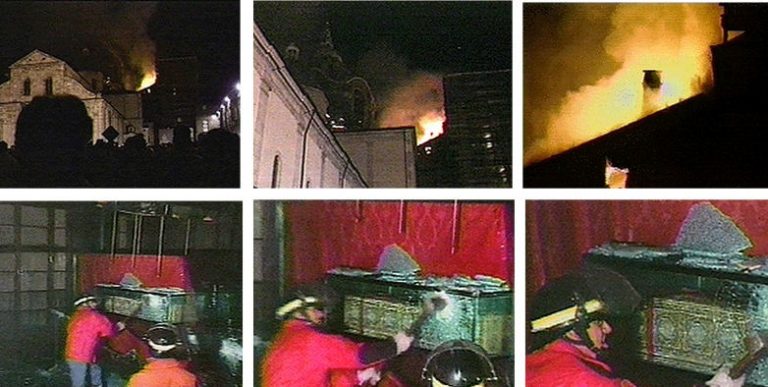

CASE 7: THE TURIN SHROUD

On 11 April 1997, the Turin Shroud had its third known encounter with fire. The dome of the Guarini Chapel, which was undergoing renovation for forthcoming public exhibitions, caught fire. It spread quickly and engulfed the chapel interior. Fortunately, the Shroud’s custodians had moved it from the chapel’s altar to a safer place inside the Cathedral itself while the restoration was underway. The Shroud’s silver casket had been placed behind bullet-proof plate glass which firemen smashed before taking the casket to the apartment of Cardinal Giovanni Saldarini, Archbishop of Turin and Custodian of the Shroud, for safekeeping. The incident is vividly told here with more photographs captured by RAI Italian Television. Whatever the status of the Shroud is taken to be that incident shows that the safety of an artefact can sometimes be treated as a matter of paramount importance.

WHAT STARTED THE NOTRE-DAME CONFLAGRATION?

With the extensive, entire-cathedral threatening fire at Notre-Dame (above), the Mailonline reported that a young construction boss had boasted about the ability of his small firm (“Cathedral Restorers”) to protect historic sites when it won a £5million contract to repair the Notre-Dame spire. Investigators reportedly believe the blaze started in the roof cavity below the spire – see below. It has since been denied that work had begun on the spire itself or that tools were present. The last of a group of large free-standing copper sculptures that surrounded the base of the spire (as also seen below) had been removed just days before the fire.

The blaze is now said to have been discovered at “around 6.50 pm” after workers reportedly downed tools between 5pm and 5.30pm. It has not been said what those workers had been doing or with what tools they had been working. According to investigators, an alarm had gone off at 6.20pm but no fire was found. The alarm sounded again at 6.43pm, by which time the flames were already burning out of control and visible across Paris. The contagion’s unaddressed half hour before the second alarm might have had even more disastrous consequences: the Notre-Dame fire-fighters had been within half an hour of losing control of the blaze and, hence, of being able to save the cathedral’s stone fabric. It would seem that this end was only achieved by an astute structural appraisal and the decision by the fire-fighters to sacrifice part of the interior in order to protect the massive timbers of the bell tower which buttresses the accumulated lateral thrust of the nave vaulting and thereby prevents the collapse of the building. (See the Architect’s Newspaper – “Here’s what saved the Notre Dame Cathedral from total destruction” )

GENERAL LESSONS

As the fire raged late into the evening of Monday 15 April, many despaired throughout France. Our colleague, the Leonardo specialist Jacques Franck, wrote:

“…We are all in tears. Just think of the same happening to Westminster Abbey and you’ll know how we feel tonight. All I can say is that we are all shattered and desperately sad: the unthinkable has destroyed 50% of France’s most beautiful cathedral! Whatever the cause of the fire, disasters of this kind should never happen. In my country the law forces ordinary people, that’s to say those not owning historical monuments with precious contents, to put warning signals in any flat or house so that the slightest sign of fire can be detected at any moment. Was it not the case in this emblematic building which had resisted the worst, wars and revolutions, through nearly a millennium? Notre-Dame will be reconstructed but the precious and unique works of art it contained are gone for ever. It is a shame that the French cultural authorities did not make such a terrible event impossible, given that all the security techniques to prevent it exist nowadays.”

In the event, although the catastrophe was less than total (the extent of the damage to the building’s stone fabric after its ordeal by fire and massive volumes of water and resulting steam, remains to be established) it seems clear that it is only through the great courage and good judgement of the fire-fighters that much of the building still stands. Had the ancient stone vaulting not largely withstood the crashing and burning spire and giant roof timbers the entire length of the cathedral including the bell Tower would likely have been engulfed. Franck’s charge of manifest official negligence still stands, a week later and as disturbing reports of prior negligence by the authorities have emerged through Italy, a French newspaper and a French arts blog.

In the 22 April 2019 La Tribune del l’Art, blog (“Audrey Azoulay est-elle légitime pour s’occuper de Notre-Dame?”) Didier Rykner points out that an alarming report on the security of the Notre-Dame in Paris had been in the French administration’s hands since 2016. The existence of this report was disclosed by the French newspaper, Marianne, on April 18 (“Notre-Dame de Paris : “Nous avions alerté le CNRS sur les risques d’incendie””). The newspaper published an interview with Paolo Vannucci, professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Versailles, which revealed that a study funded by the CNRS (- the National Centre for Scientific Research, and therefore the State) was carried out in 2016 on the safety of Notre-Dame de Paris, especially in the event of a terrorist attack. The study had concluded, it was said, that: “the risk of a burning of the roof existed”, and “it was absolutely necessary to protect and install a system of extinction”. It was further disclosed that: “In truth, there was virtually no fire protection system, especially in the attic where there was no electrical system to avoid the risk of short circuit and spark.” Worse: even lightning could trigger a fire (- much as had happened at York Minster in July 2009) and it was therefore necessary “to install a whole system of prevention”. Rykner reports that Prof. Vannucci, had confirmed that there were no smoke or heat detectors and believed that “the government was well aware” of this absence. Vannucci had attended a concluding meeting at the Ministry of Education with seven or eight people from different institutions. While he did not remember whether a representative of the Ministry of Culture was present he found it hard to imagine that the ministry, which is in charge of the Notre-Dame monument, would not have been made aware of such an alarming report, not least because although the CNRS is under the supervision of the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation, it has very close links with the Ministry of Culture.

What would seem on the fire-fighters’ forensic analysis to be beyond question, is that the fire began underneath the base of the spire from around which the group of copper sculptures had just been removed (see above). What might also be considered, perhaps, beyond dispute is that today’s custodians of western heritage have become astonishingly un-averse to risk-taking in their stewardship of artefacts – even when those artefacts comprise integral parts of ancient cathedrals.

In 2014 we complained that the authorities at Canterbury Cathedral had permitted six whole windows, each with a single monumental seated figure that, in its grandeur and gravity, had anticipated Michelangelo’s giant Sistine Chapel ceiling prophets, to be packed and sent off across the Atlantic (see above) to tour American Museums – even though these were now the only surviving parts of an original cycle of eighty-six ancestors of Christ that had once formed one of the most comprehensive stained-glass cycles known in art history. The pattern and the gravity of heritage stewardship failures seems clear and beyond dispute but from where might the will to correct it spring?

Michael Daley, 23 April 2019