The National Gallery’s continuing silence on its removal of the oak panel support of the attributed Rubens Samson and Delilah increasingly resembles a tacit acknowledgement of institutional culpability.

Matters were recently brought to a head by Dalya Alberge’s explosive account (“Fresh doubt cast on authenticity of Rubens painting in National Gallery” ) of Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s book NG6461 – The Fake National Gallery Rubens. That account left both the National Gallery and Christie’s (from whom the gallery acquired the picture in 1980 for a then world record Rubens price) declining to offer a response.

This dispute was already of long standing in 2000 when Artwatch UK devoted an entire issue of its journal – the first of two – to the untenable nature of both the Rubens ascription and the National Gallery’s official accounts of its restoration, as published in its own Technical Bulletins – see the journal’s cover and introduction below:

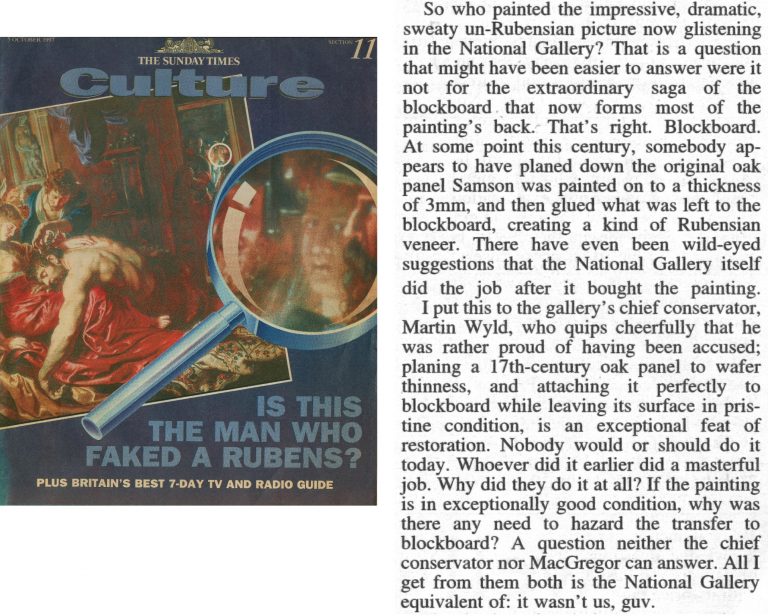

SO, WHODUNNIT THEN?

Above, Pic 3: The 5 October 1997 Sunday Times Culture magazine in which its art critic Waldemar Januszczak supported critics of the Samson and Delilah’s Rubens attribution and suggested that the picture’s forger had included his own portrait among a group of soldiers. Januszczak subsequently endorsed the Rubens ascription but here he challenged the National Gallery to identify the persons responsible for planing down a cradled panel and attaching its greatly reduced (3 mm thick) structure to a sheet of modern blockboard. The restorer Martin Wyld expressed admiration for the undisclosed restorer’s skill by quipping he was rather proud of being accused but, like the gallery’s then director, Neil MacGregor, he too was at a loss to propose the restorer in question. (On Wyld’s own but not there-declared great familiarity with, and expertise on, planed-down panels at the National Gallery, see below.)

Below, an article published in The Jackdaw, March/April 2010<strong, on the retirement of a National Gallery restorer:

PEAK NATIONAL GALLERY RESTORATION TECHNO-ADVENTURISM:

After the National Gallery’s recurrent and bruising restoration controversies of the 1940s and 1960s, by 1980 the confidence, ambition and experimental zeal of its restorers and scientists was high and rising.

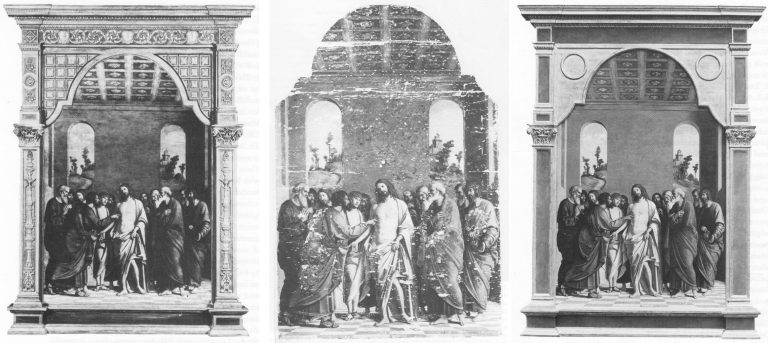

Above, Pic. 6: The National Gallery’s altarpiece panel painting The Incredulity of S. Thomas by Cima da Conegliano, as here seen (left) before restoration; after cleaning (centre); and (right), after repainting and remounting in its radically altered frame.

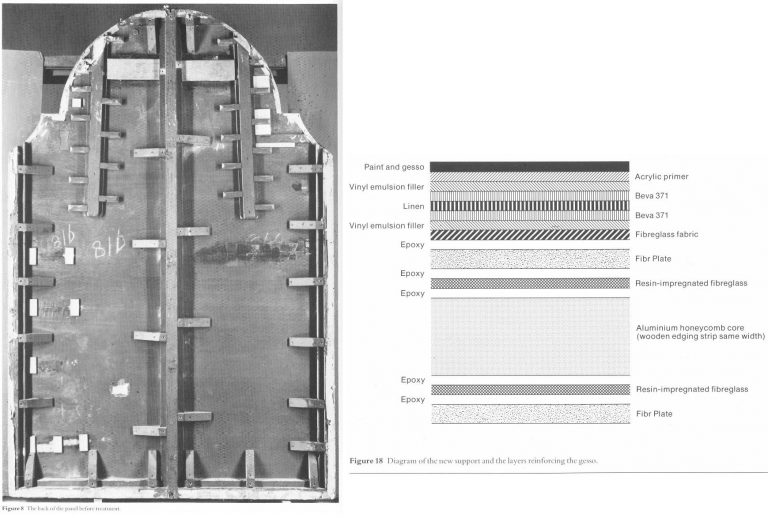

The Cima altarpiece underwent the most radical alterations on every component part: its panel; its frame; and, the painting itself. This was a totally made-over work. All aspects of its history-defying transformation were lovingly reported in the successive National Gallery Technical Bulletins of 1985 and 1986. Setting aside the profoundly radical pictorial alterations, of particular interest here is the elimination of the entire panel on which Cima’s painting had been made and its replacement by an extravagantly multi-layered sandwich of modern synthetic materials. The painting itself was left as flat as a dry-mounted photograph.

Above, Fig. 7, showing (left) the original giant reinforced panel of Cima’s altarpiece, and (right) a cross-section diagram showing the multiple layers of synthetic materials assembled in replacement of the picture’s original panel

HOW TO DISAPPEAR AN ENTIRE PANEL

Concerning Martin Wyld’s 2010 publicly declared knowledge of the locations of certain National Gallery skeletons – and the earlier comments he had made on the Samson and Delilah panel to Waldemar Januszczak, his account in the 1986 Technical Bulletin of his chiselling away of the entire wood panel of seven giant planks just under two metres long on this major Cima altarpiece becomes an item of historical and institutional interest. In the first stage, the picture was laid down with its painted surface face upwards and a temporary support was added to it – that is to say attached to the front of the painting itself. This support comprised, Wyld reported, first covering the painted surface with two layers of tissue fixed in place with a resin (and small amount of oil) coating and then a third added layer of tissue. Cheese cloth was then pasted over this layer. Then a paraffin wax layer was brushed on and then largely scraped off to leave a thin even layer. Then a substantial structure was added to provide a temporary support for the paint and gesso layers. This support consisted of a 1cm thick board of Sundeala board (soft, pinboard material) which was supported by a 5 cms deep paper honeycomb glued on to a hardboard layer. The painting was then turned over, exposing the original and by then reinforced panel and its entire removal was begun. In the first stage, the panel was reduced by Wyld “from c. 5 cm to 1 cm.” with entirely manual means – that is to say, to by chisels:

“Semi-circular 15 mm gouges were pushed along the grain, cutting channels 6-7 mm deep, and the ridges left between the channels were then cut down. Each plank was reduced by a similar amount, and the process repeated until the panel was reduced from c. 5 cm to 1 cm thickness…The removal of the first layers of wood is usually the easiest part of a transfer [of the paint layers]. The removal of the final layer of wood was complicated by several factors [principally, where previous repairs of the paint had left the original wood panel impregnated by waxes and glues] … Experience during earlier transfers had shown that the safest method of removing the last layer of wood was to cut a very shallow slope at a slight angle to the grain and to shave away the tapered edge of the wood with a small fish-tail chisel. The method proved impractical on the Cima. The parts of the panel affected by thick animal glue (of the consistency of carpenter’s glue) or putty filling the worm channels, by knots and by later or original inserts of wood obviously needed individual treatment. However, the remainder of the wood was so insecurely attached to the gesso that it was impossible to cut a shallow slope because strips broke away along the grain no matter how carefully the chisel was used. Strips of wood 10-12 cm long and 3-4 cm wide would become completely detached, but usually with a few small fragments of paint and gesso stuck to them. These fragments were laboriously cut off the wood and replaced… It was found that the safest method of removing the last layer of wood in the very loose areas was to cut it away at an angle of 30 degrees to the gesso, instead of across at the very shallow angle normally used, and to cut across rather than along the grain…”

Such thinning to the point of the complete removal of an entire panel, clearly, calls for impressively high levels of mechanical skill. By comparison, simply reducing the Samson and Delilah’s 2.5 cm to 4 cm panel to c. 3 mm and then glueing it on to a new sheet of blockboard must have seemed a piece of cake.

For more information on the National Gallery’s restoration treatments and curatorial appraisals – including a major structural accident that befell the Cima altarpiece – and National Gallery photographs showing the work in progress under the eye of the then Director, Michael Levey, see: The Demise of the National Gallery’s “made just like Rubens” Samson and Delilah with inexplicably cropped toes.

Michael Daley, Director, 1 April 2025