Sandle at Flowers Gallery, Kingsland Road

For those interested in connections between drawing and sculpture; sculpture and thought; fine art and politics, the present showing of Michael Sandle R. A. at the Flowers Gallery, Kingsland Road is not to be missed – but hurry: it closes on the 20th.

All of the photographs above are: © Michael Sandle, courtesy of Flowers Gallery, London and New York.

The works are, respectively from the top:

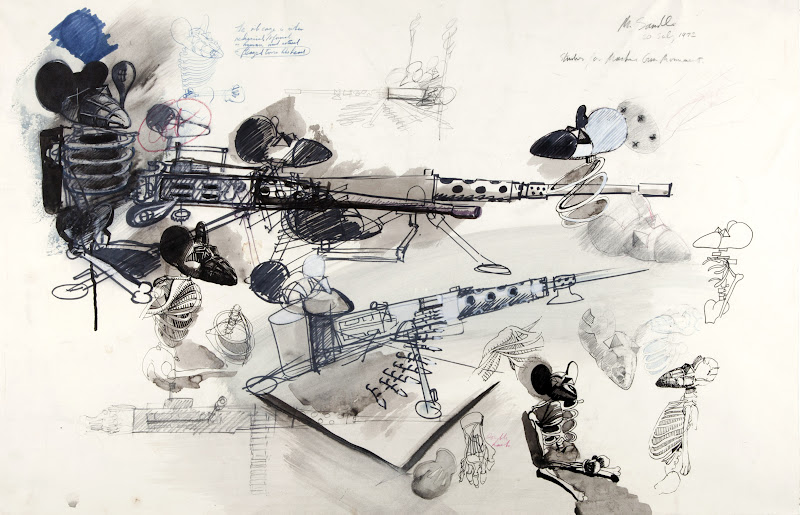

Michael Sandle: Study for Mickey Mouse Machine Gun Monument (detail), c. 1972, Ink and gouache on paper, 56 x 76 cm – 22 1/4 x 30 in.(AFG 51585)

Michael Sandle sculpture on exhibition in the ground floor gallery at Flowers East. (The drawings are shown in a first floor gallery.)

Michael Sandle: Submarine under construction, 1976, Etching, 69 x 87 cm – 27 1/8 x 34 1/4 in A/P. (FG 10192)

Michael Sandle: Der Minister fuer Propaganda, 1981, Bronze, 125 x 35 x 40 cm – 49 1/4 x 14 x 15 3/4 in.(AFG 48739)

Michael Sandle: Study for Mickey Mouse Machine Gun Monument, c. 1972, Ink and gouache on paper, 56 x 76 cm – 22 1/4 x 30 in.(AFG 51585)

Michael Sandle: Battleship, 2014, Ink and wash, 95 x 145 cm – 37 3/8 x 57 1/8 in, Framed: 103 x 153 cm.(AFG 52744)

Michael Sandle: Mickey Mouse Head with Spikes, 1980, Bronze, 40 x 42 x 40 cm – 15 3/4 x 16 1/2 x 15 3/4 in, Edition of 8. (AFG 53566)

Michael Sandle: Unmoglicher Hund (Impossible Dog), 1981, Bronze, 14 x 40 x 30 cm – 5 3/4 x 15 3/4 x 12 in, Edition 1 of 8 (1/8). (AFG 50162)

As can be seen in the photographs above, Sandle’s work speaks powerfully and eloquently for itself but, in this show, it is also assisted by a quite exceptionally thoughtful well lit display. As it happens, the particular group of photographs of Sandle’s work selected here reflects in small degree the especial interests of this author, a working draughtsman who was reared in sculpture. Graphically speaking, Sandle is brilliant. He was Slade-trained at a time when such counted. His etched depiction of a u-boat in its concrete lair in war-time Normandy may be his graphic masterpiece. His sculptures range from the monumental to medium/small phenomenally “compressed” and bristling potent artefacts, as seen especially in his politically pointed subversions of a Disney icon. For Sandle, Mickey Mouse stands primarily as a metaphor for what he sees as the “obscenely lightweight” aspects of our culture. But political ends and intentions aside, Sandle’s selection of Disney is one that has clearly nourished and armed a politically and culturally affronted artist. Inadvertently or no, Sandle, pays obeisance to the man who, arguably, has done more than anyone in the face of a modernist, reductionist, fractured twentieth century to maintain/prolong/extend the great western collective academic studio productions of sculpturally coherent, spatially situated, humanly-resonant and engaging figures. Walt Disney achieved his near universal appeal not because of his politics but through his rigorously applied hierarchical, academically purposive studio systems and craft traditions. The traditional, academic terms “master” and “student” found living contemporary equivalents in Disney’s “originators” and “in-betweeners”. Mickey Mouse and other Disney Icons are not one-off graphic images – and some may feel that such is their artistic potency that they dwarf such parasitical one-trick fine artists as Warhol and Koons. Mickey Mouse makes such a plumply rich satirical target because his creators conjured by art and artifice a living versatile, perpetually changing, culturally reflective creature. He has moods; can feel patriotism (see below). He endures and can feed even those who would mock and reject his presence.

While Sandle might wish to subvert or invert the ideological ends of the western classical tradition of monuments made to honour, celebrate and immortalise wartime sacrifices and heroism, his repeated borrowing of the stepped plinth betrays a recognition of and dependency on the sheer force and eloquence of that classical tradition. The sculptures and monuments erected by the New English sculptors after the First World War remain a thousand times more enriching than the piously liberal and “inclusive” inanity and narcissism that constitutes the state-approved public sculpture of our time. Sandle has wisely cast himself apart from such and avoided the trap of his times. If his unapologetic membership of an artistic “awkward squad” has cost him certain public commissions that he might have merited and would otherwise admirably have fulfilled, it has also innocculated him from a prevalent sculptural vacuity. Sandle does not play with materials. His strengths are complex and deep-rooted. His obsessive iconographic predelections channel more than artistic ambivalence and political anger. Having long possessed the wit to harness plinths to new purposes Sandle should, of course, in a sane and fair contemporary art world, have been a prime candidate for occupancy in Trafalgar Square. His oeuvre betrays a devotee’s admiration of and nostalgia for the great archetypal artistic sculptural monuments of our recent past – how might Lutyens ever be thought obsolete? Sandle has fabricated and occupied a Lutyens-shaped universe as surely as he would disavow any Kiplingesque impulse. Succour is obtained and relevance derived from engagement with bona fide monumental sculptural forces as encountered not in the tedious affectation of modernist architecture but in the primary source: in the real maritime architecture and sculpture of warships and their sea-borne gun emplacements. We suggested a few years back that Denys Lasdun, for all his talk of Hawksmoor and Palladio, betrayed a secret and illicit sculptural indebtedness to his first-hand knowledge and sight of the reinforced concrete structures of the German seaboard defence structures in Normandy; in the concrete ziggurats of gun emplacements and in the raked projections of u-boat pens and their bomb-proof reinforced lids (see below). Talent will out and hungry sculpturally alert architects and sculptors must take nourishment from wherever it is readily and rewardingly to hand – and do so regardless of any ideological taint or cultural associations. If Sandle seems to bite the hand of traditions on which he draws and feasts, we all benefit from his singular cultural “dynamic” – and, for a few more days, may do so in an exceptionally congenial and sympathetic venue.

Michael Daley, 16/17 February 2016

(The works below are: top, U-Boot-Boxen, by Theo Ortner; centre, a corner of the National Theatre by Sir Denys Lasdun, as published in “Modernism’s Secret Passion?”, the ArtWatch UK Journal No. 24, Summer 2008; and, bottom, Mickey Mouse from the cover of Disney During World War II, 2014, by John Baxter.)

Leave a Reply