Leonardo and the Growing Sleeper Crisis

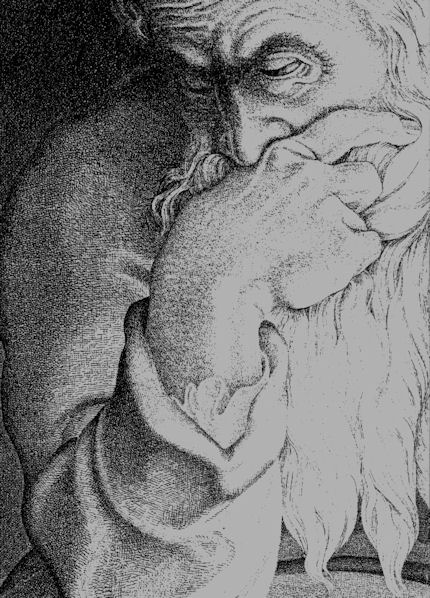

Another day, another new Leonardo drawing – this time a St. Sebastian with a mismatched verso and recto, with as many legs as a millipede, and lashed in a gale-force wind to a tree set in a landscape of icebergs…

Above, Fig. 1. A newly proposed Leonardo whose problems will be the subject of our next post. See Scott Reyburn’s “An Artistic Discovery Makes a Curator’s Heart Pound”, the New York Times, 11 December 2016.

The old masters world is bursting with Leonardo “discoveries” that flaunt their five-century no-histories. (See Problems with “La Bella Principessa”~ Parts I, II and III; and, “Fake or Fortune: Hypotheses, Claims and Immutable Facts”. “Problems with La Bella Principessa ~ Part I: The Look”.) At the same time there is a near meltdown over a spate of recent high quality exposed fake “sleepers” and “discoveries”. Sotheby’s has hired its own in-house technical analyst to spot inappropriate materials in new-to-the-scene old masters so as to “help make the art market a safer place” (“FBI expert to head up Sotheby’s new anti-forgery unit”, 6 December 2016, the Daily Telegraph). This is no bad thing and the appointment has been universally welcomed when, following the fake Frans Hals affair, it is reportedly feared that 25 forgeries sold for up to £200million are on the walls of unsuspecting owners, and when the new Sotheby’s appointee had himself single-handedly unmasked 40 supposed modern masterpieces sold for £47million at the now deservedly gone Knoedler Gallery, New York.

The real crisis, however, is the product of failures of judgements even more than failures to carry out due diligence checks on the material components of works. It remains the case that aside from works instantly disbarred by technical diagnosis, identifying authorship and establishing authenticity will necessarily and inescapably continue to be a matter of professional judgement. (We hold that here is systemic methodological flaw in appraisals that has yet to be addressed.) Meanwhile, dealers, critics, scholars and collectors embarrassed by suspected fakes are left agonising: should they concede error and take a hit on credibility but thereby limit damage, or should they stand firm and double the risks?

Even professional sleeper-hunters are falling out in acrimonious fashion over rival BBC television platforms – sorry, programmes – with one said to believe the other jealous of his good looks and success: “It’s a copy: Fake or Fortune? Stars try to halt rival show”, Richard Brooks, Sunday Times, 4 December 2016.

One auctioneer shouts you’ve ruined my sale at a musical scholar on Radio4. “Sotheby’s view is shared by the majority of world renowned Beethoven scholars who have inspected the manuscript personally”, the Sotheby’s man insists when characterising a scholar’s refusal to come in to view the manuscript as “irresponsible” (“Sotheby’s give Beethoven expert an earful after copied manuscript row scuppers sale”, The Times, 30 November 2016.)

The charge is a red herring, we say: if errors in the manuscript are visible in an auction house’s high quality photographs, coming in to touch the paper will not make them go away. If the auction house’s (anonymous) world authority musical experts think there are no errors, we add, they should come forward and say so. A Cambridge professor of musical theory did step forward to affirm his endorsement of the manuscript but he also admitted having been bothered by an anomaly (“Sotheby’s expert admits doubts over Beethoven script”, The Times, 3 December 2016.) To Sotheby’s likely mortification, it was revealed that arch-rival Christie’s had refused to sell the score last year, after being unable to confirm its authenticity – “Beethoven manuscript row remains unfinished”, the Daily Telegraph, 30 November 2016: “There was some good news for Sotheby’s however as the auction house succeeded in breaking a new auction world record for another musical manuscript…Gustav Mahler’s complete Second Symphony (the ‘Resurrection’), written in the composer’s own hand…went for £4,546,250.”

“Sotheby’s catalogue was an artful dodge, claims Russian billionaire” – the Times, which reported on 8 December: “Mr Ivanov said that honest mistakes were understandable. The problem is at Sotheby’s the fakes are listed as the top lots and are published”. With experts in as much disarray as auction houses and dealer/broadcasters, what perfect timing, then, for the appearance of a new, cool and calm legal anatomy of the sleeper phenomenon and its associated problems of authentication.

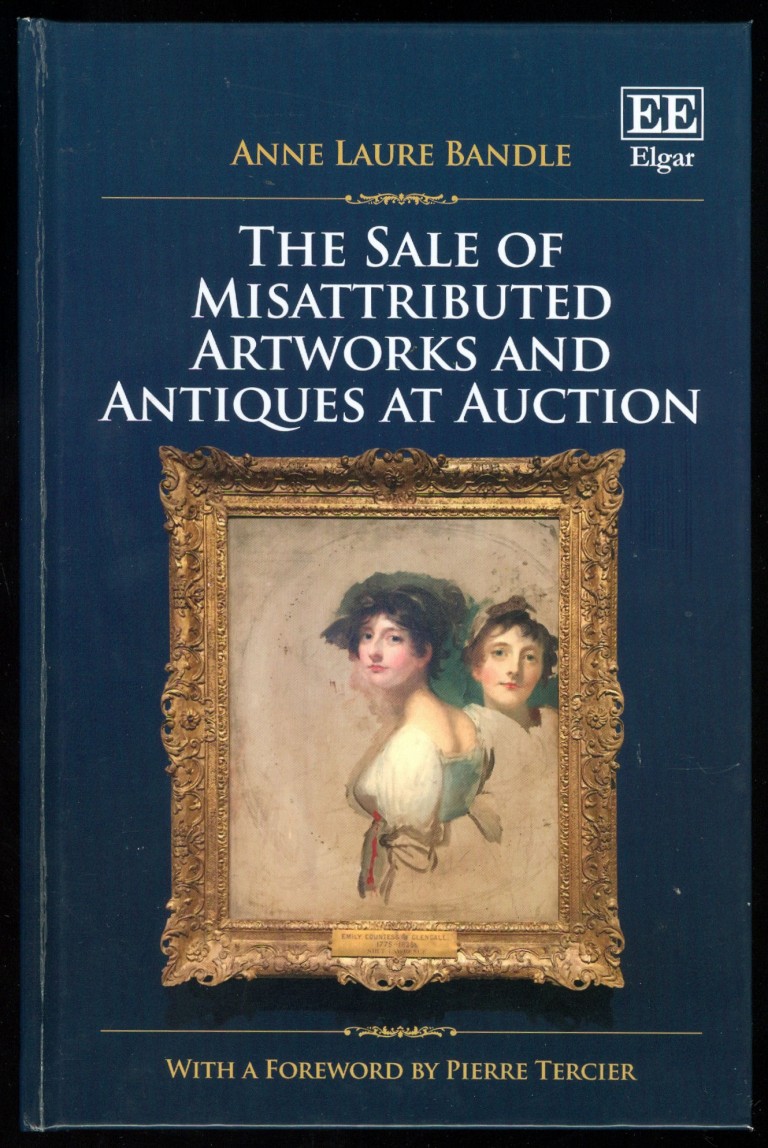

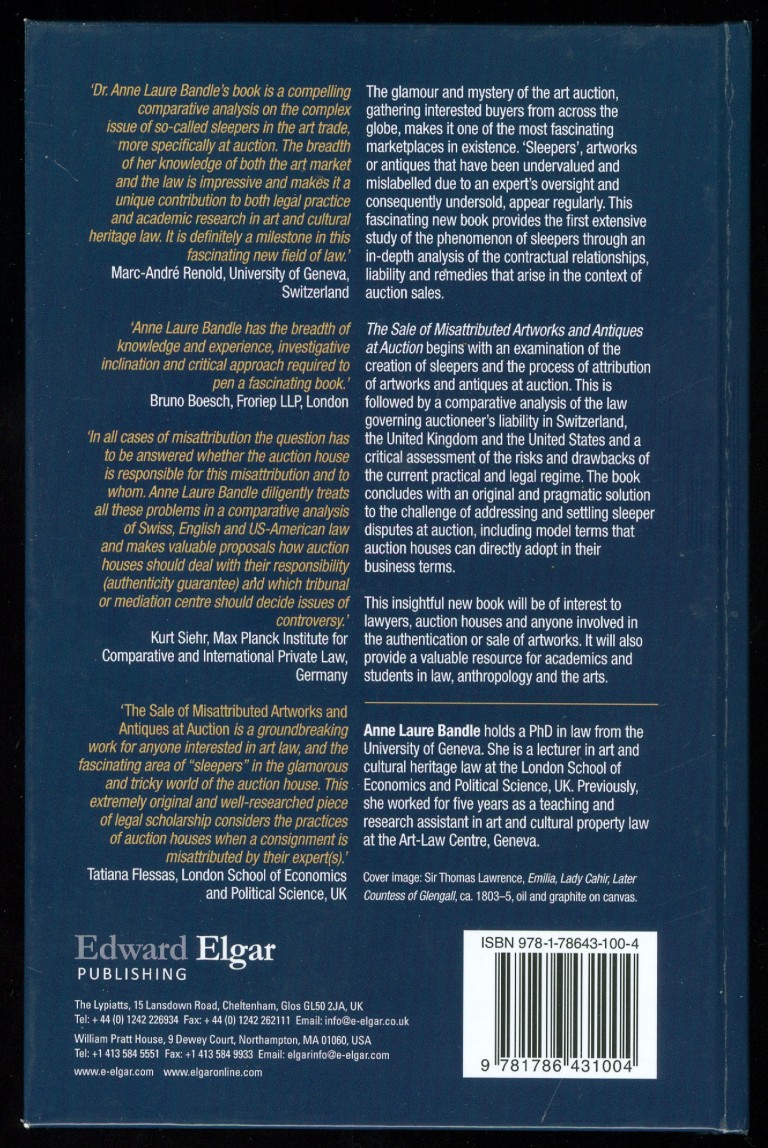

Above, Fig. 2. In “The Sale of Misattributed Artworks at Antiques at Auction” by Anne Laure Bandle of the London School of Economics and a director of the Art Law Foundation (Geneva), we encounter a book greatly richer and more urgently required than what is simply “said on its tin”. This work, the product of a PhD at the LSE, deftly turns over the law with regard to art market workings as encountered and applied under three key (for the art market) systems of law, those of Swizterland, England and the United States. Under all three it is shown how the auctioneer’s primary duty is to the seller (the consignor) not the buyer. It follows therefore that failing to identify the proper status of a work of a work when conferring an attribution can/should carry penalties of compensation to the consignor. However, in response to this duty/financial danger, auctioneers insert massive disclaimers of liability into their contracts and attributions. These disclaimers are also widely appreciated in terms of warnings to buyers of a need to satisfy themselves of the validity, accuracy and reliability of any catalogue description before buying. Such self-protective clauses have consequences that can bite hard on those who apply them. For one thing, we would add, forgers have not been slow to notice them.

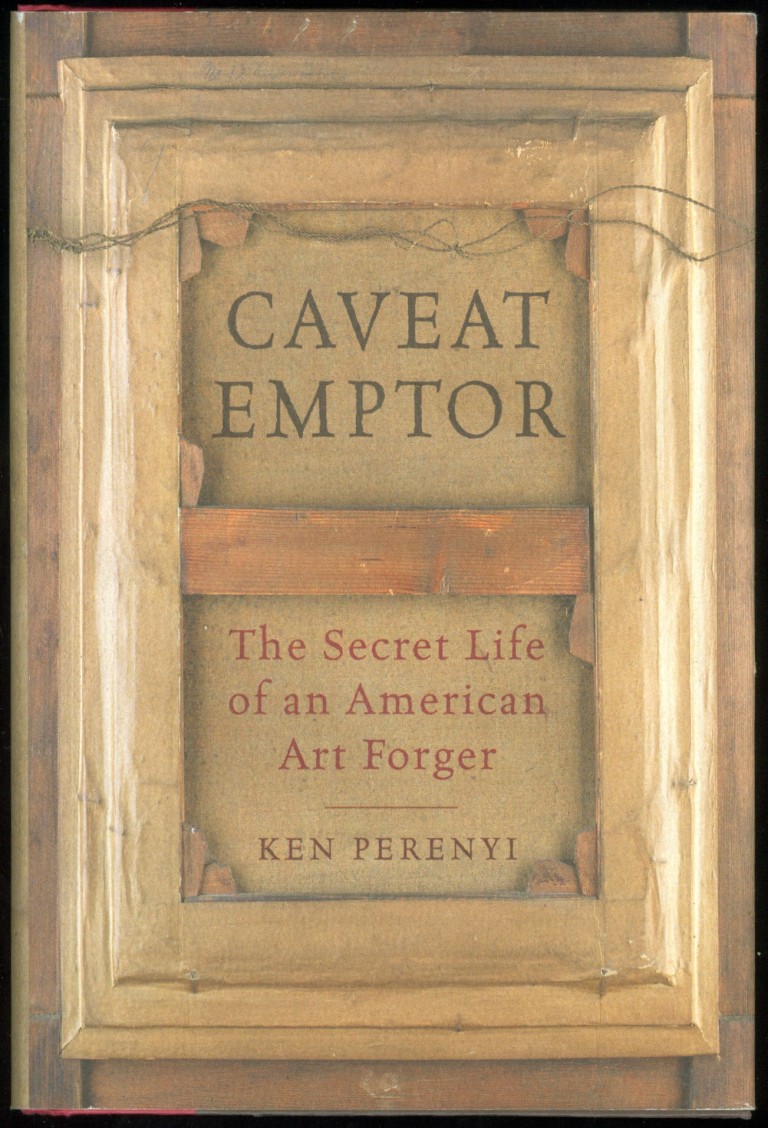

Above, Fig. 3. The American Ken Perenyi, cheekily called his 2012 Forger’s Memoir Caveat Emptor – The Secret Life of an American Forger. With little interest in consignors’ rights – he being both the knowing maker and the eager consignor of forgeries – Perenyi, after first studying the terminology of attributions in London auction house catalogues (“Attributed to; Signed; Studio of; Circle of; Manner of…”) swiftly moved to “Conditions of Business”; “Limited Warranty”; and thence “Terms and Conditions”. He reported (pp. 228-247) that when in London he noted that:

“In what can only be described as a masterpiece of duplicity, the terms and conditions made it clear (that is, if one has a law degree) that they warranted and guaranteed absolutely nothing. However, farther down, a paragraph entitled ‘Guarantee’ made it plain for even the most thickheaded. It stated: ‘Subject to the obligations accepted by Christie’s under this condition. Neither the seller Christie’s, its employees, or agents is responsible for the correctness of any statement as to the authorship, origin, date, age, size medium, attribution, genuiness, or provenance of any lot.’”

On return to the United States he then examined New York auction house catalogues: “Again and again we saw the phrase neither Christie’s nor the consignor make any representations as to the authorship or authenticity of any lot offered in this catalogue. ‘Hell, they don’t guarantee anything [over] here either!’ I said.”

After reading a paragraph on forgeries stating that if within five years of a sale the buyer could establish “scientifically” that a purchased painting was a fake, the “Sole Remedy” would be a refund of monies paid [- But for a cautionary case-in-point today, see UPDATE , below] Perenyi concluded the following: “A) Virtually nothing sold here was guaranteed to be what it claimed to be, B) Neither the auction house nor the seller assumed any responsibility whatsoever, C) Even if a buyer discovered a painting to be an outright fake, all he could do was ask for a refund, I came to the conclusion that this was an engraved invitation to do business.”

His late partner, José, concluded “Well, maybe we could save people the trouble of going to London and sell them [Perenyi’s forgeries] right here!”

In her new book, Dr Bandle carries the full terms and conditions of three auction houses (Christie’s, Koller Auctionen’s and Sotheby’s) as an appendix. She notes that notwithstanding disclaimers, such is the volume and reach of art sales that many art market players take auction house catalogues as reference points on the identification and evaluation of art and antiques and do so particularly with regard to attributions, confidence in which confers authority and engenders trust. In this regard the “sleeper”, as an under-identified and therefore under-valued work, is a special problem. A (conceptually subtle and fascinating) chapter is devoted to the sleeper’s elusive and problematic character. In fact, a delight of this book is its constant precision, economy and deftness of language in what is a perpetually shifting and re-forming arena where the market structures have both democratised and globalised the ownership of art but where buyers gathered from around the globe must compete in heated races to acquire multi-million valued art in spectacular shows of competitive bidding that are over in minutes. In a recent double television celebration of Christies-in-the-World, the term “buyer’s remorse” was heard in counterbalance to auctioneers’ seductively whispered advice to “think how terrible you will feel tomorrow if you don’t get this”.

A “sleeper” is first identified as being not a legal term but a figurative illustration of a legal problem. It is one that fleshes the notion that an artwork can remain a “dormant treasure” until it is properly identified. If not so identified, it stands dangerously (to auctioneers, and expensively to consignors) as a work that has been “undervalued and mislabelled due to an expert’s oversight and consequently undersold”. Sleepers are products of three types of error and each receives its own section. The extent to which restorations aiming and claiming to recover original conditions may alter objects and mislead authenticators is examined.

(But for our specialised concerns, recognition of the inherently problematic nature of restoration’s role in the identification and subsequent elevation of authenticity is a rare instance of under-examination in this book. Stripping off later materials does not in itself recover original states. It may disclose little more than badly damaged remains of an earlier, more “authentic” state. How much repainting, or “retouching” as it is euphemised, should be considered permissible before a worked-over sleeper approaches a forged recovery of authenticity? – See “A restorer’s aim – The fine line between retouching and forgery”.

It should be said that sensitivity in this arena is not an art market-confined problem: the Frick Museum does not publish the photograph below – Fig. 6 – of a stripped-down, not-yet repainted Vermeer that the Getty Institute holds and makes freely available – and many museums, in our experience, sit on photographs of their own restoration-wrecked paintings.)

Dr Bandle’s section on the relationship between sleepers and fakes or forgeries, between the unrecognised and the counterfeit, is adroitly introduced: “sleepers are the negative reflection of counterfeits: both are held as something that they are not.” Fine distinctions are drawn between a fake and a forgery. Both are characterised “negative concepts, referring, as they do, not to qualities but to their absences.” Before considering the legal status of sleepers, a fascinating examination is made of the tools and methods of attribution. So examined, too, are the hoped-for instruments of probity, the best-practice and ethical codes for authentication and dealing. Like auction house terms and conditions, ethical codes are shown carry their own disclaimers: “Similarly, the Swiss Association of Dealers in Antiques and Art contains a disclaimer of the attribution and appraisal’s accuracy.” (One hears a Perenyi expletive of delight here.) As for auction houses, while they “issue attributions in sale catalogues, they are not considered to be formal authentication reports”, whatever weight they might carry in the market and for buyers.

The section on the “Essence of Attribution” might be considered essential reading for all art market players and commentators, not least because the art market “greatly relies on scholarship”, and such expert appraisal is uniquely challenged “by the peculiarities of the art world” – one of which is that however long debates rage, scholars themselves “may very well never achieve a consensus”, in which case, the circularity is complete: “scholarship cannot halt during the art object’s identification process by establishing an attribution, not even temporarily”. Like painting the Forth Bridge, attributing an art object can be “an ongoing undertaking that never settles”. Existing attributions are constantly subject to challenge or revision.

The law itself can seem helpless or exasperated in the face of art world processes. Elusive notions of authenticity tax judges as well as scholars. With regard to establishing the merit or applicability of warranties of authenticity or the diligence of experts, even the admission of testimony is problematic within both Swiss civil law and the English and United States traditions of common law. Swiss courts can commission reports and instruct experts to answer set questions. Under common law conflicting parties support their rival positions by calling rival and conflicting experts. Courts may confine these adversarial jousts to “that which is reasonably required”. Under US Federal rules courts may exclude what they consider “unreliable expert testimony” and even when testimony is based on scientific principles it may be held acceptable only when these principles have “gained general acceptance”.

Under Swiss, English and United States jurisdictions alike, contractual relationships governing art auction sales are not clearly defined by law and are subject to scholarly debate (which, as mentioned, is a never-ending process). Further complications arise from the dual and conflicted position of the auctioneer. Does he really serve the buyer’s or the seller’s interest – or, somehow, both? In practice, we might think, he should/must aim to serve both since different people must always be persuaded any moment that it is a “good time” to sell and a “good time” to buy. Failures to recognise “sleepers” are the mirror image of failures to recognise fakes or forgeries: the one injures consignors’ interests, the other those of the buyer. But how to stay out of trouble as an auctioneer when case law results in unclear and unreliable notions of liability – and while there is a requirement to perform diligently but not one to produce to specific results?

By increments the law emerges as unfit for its presently allotted purpose in resolving sleeper disputes. Auctioneers are judged by standards predicated on what is little more than a fiction. Standards of performance must be interpreted on a case-by-case basis but these provide no benchmark in cases of sleepers sold at auctions. Aside from these problems, judges generally lack connoisseurship in art and art auction sales and may have difficulty in assessing authenticity and in reconstructing the attribution process – and while this is understandable because art connoisseurship and art market mechanisms are both highly sensitive and influential forces, judges, no matter how well educated and competent in other areas of the law, will struggle to redress a present structural imbalance between the interests of (favoured) buyers and (disfavoured) consignors.

Can applications of the law be made to work in this arena? Are alternatives to the law presently or potentially available? For answers to these questions it is necessary to read the concluding section of a timely book that will commend itself to Art’s players and watchers alike.

The Sale of Misattributed Artworks and Antiques at Auction, Anne Laure Bandle. ISBN: 978 1 78643 100 4 Price £100 or Web: £90

Michael Daley, 15 December 2016

UPDATE 17 December 2016

In the 17/18 December Financial Times “The Art Market”, Melanie Gerlis writes:

“ Art is notoriously a ‘buyer beware’ market, but even prolific professionals can get caught out. Micky Tiroche, a private dealer in London and co-founder of the Tiroche auction house in Israel, bought ‘Sun and Stars’, a gouache attributed to Alexander Calder, for £28,000 (with fees) at Bonhams, London in 2007. The purchase was made through his dealing company, Thomas Holdings, which has about 160 works on paper by Calder.

“In 2013, the gouache was submitted, along with other works, to the Calder Foundation in New York, which doesn’t officially authenticate the artist’s works but gives them an inventory number (known as an ‘A-number’ because the digits are prefixed with the letter A). ‘Sun and Stars’ was not given an A-number, making it effectively unsellable.

“Christie’s, Sotheby’s and now Bonhams will not sell Calder works that do not have an A-number.

“Tiroche, who buys frequently at Bonhams as well as elsewhere, says that he asked the auction house for a refund and was refused. He has suggested alternative, less visible ways of refunding (such as deducting its value from other works) and legal letters have been exchanged, but to no avail.

“A spokesman for Bonhams said: ‘It is [the auction house’s policy] not to discuss individual cases, beyond saying that we are in communication with Mr Tiroche’s company about the situation.”

Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship

Connoisseurship may be defined as expertise in art in the very narrowest of senses; surprisingly, however, it is also a definition in which many different disciplines intersect.

In the public realms of law and the art world, a ‘connoisseur’ must be recognized as being an expert, as being capable of giving credible testimony regarding the subject, and as remaining actively engaged with the world in which attributions and authentications are made. This public recognition takes years of work and is hard-won.

Yet, does this public recognition of expertise signify accuracy or truth in the claims that a connoisseur makes about art? This one-day conference investigates the always-interrelated and often mutually-troubled processes by which connoisseurship is constructed in the fields of art and law, and the ways in which these different fields come together in determining the scope and clarity of the connoisseur’s ‘eye’.

“Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship”

A conference organized by ArtWatch UK, the Center for Art Law (USA) and the LSE Cultural Heritage Law (UK), to be held at: The Society of Antiquaries of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BE – all inquiries to: artwatch.uk@gmail.com.

1 December 2015 from 08:30 to 19:30 (GMT)

London, United Kingdom

For full conference programme, see below.

Admission is by ticket only.

For ticket prices and to purchase tickets (exclusively through Eventbrite ), please click on: Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship

PROGRAMME

8.30 – 9.00: Registration

PART I: The Making of Art and the Power of Its Testimonies

9.00-25: Welcome and Keynote Paper: Michael Daley, “Like/Unlike; Interests/Disinterest”

Michael Daley (UK), Director, ArtWatch UK, an artist who trained for twelve years (with post-graduate studies at the Royal Academy Schools) and taught in art schools for fifteen years before practicing as an illustrator (principally with the Financial Times, the Times Supplements, the Independent and, presently, Standpoint magazine), will suggest that the principles of sound connoisseurship in making attributions and appraising restorations are implicit in fine art training and practice, and will discuss the trial in Italy of Professor James Beck on a charge of aggravated criminal slander brought in Italy by a restorer against the scholar but not against the newspapers which had carried his reported comments.

9.25-9.40: Euphrosyne Doxiadis, “Perception, Hype and the Rubens Police.”

Euphrosyne Doxiadis (Greece), a painter/scholar whose 1996 book The Mysterious Fayum Portraits: Faces from Ancient Egypt won the won the Prix Bordin, the Prix d’ ouvrage by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Institut de France, and, the 1997 “Prize of the Athens Academy”, will challenge the Rubens attribution given to the National Gallery’s oil on panel Samson and Delilah in the 28th year of her researches. Astonished at her first sighting of this painting in the National Gallery, the author will discuss both its manifest artistic disqualifications and the edifice of support that surrounds an attribution first made in 1930 by a leading Rubens scholar who today is notorious for his many excessively-generous certificates of authenticity.

9.40-9.55: Jacques Franck, “Why the Mona Lisa would not survive modern day conservation treatment.”

Jacques Franck (FR), an art historian and a painter trained in Old Master techniques, is the Permanent Consulting Expert to The Armand Hammer Center for Leonardo Studies at The University of California, Los Angeles, with its European headquarters at the Centro Studi Leonardo da Vinci e il Rinascimento, Università degli Studi di Urbino, and an editorial consultant to Achademia Leonardi Vinci. He was a curator/exhibitor in the Uffizi’s exhibition La mente di Leonardo (2006) and will draw on experiences as an adviser to the Louvre’s restorations of Leonardo’s St Anne and Belle Ferronnière, and his current PhD investigations on Leonardo’s sfumato technique at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, to demonstrate the threats presently facing the Mona Lisa in a museum conservation system that he considers inadequate to preserve the masterpiece in the event of it being cleaned at the Louvre.

9.55-10.10: Ann Pizzorusso, “Leonardo’s Geology: The Authenticity of the Virgin of the Rocks”

Ann Pizzorusso (US) is a professional geologist and a Renaissance scholar whose work focuses on Leonardo da Vinci as a geologist. She has written numerous scholarly articles on Leonardo and his students, and the artists who preceded and followed him, analyzing the use of geology in their works. Her landmark article, “Leonardo’s Geology: The Authenticity of The Virgin of the Rocks” compared the two versions of the paintings. Demonstrating geology as a diagnostic tool – which was in fact Leonardo’s trademark – she will attribute only one of the two versions to Leonardo. Her new, four gold medals-winning book, Tweeting Da Vinci, discusses how the geology of Italy has influenced its art, literature, religion, medicine.

10.10-10.30: Discussion/Questions: – Irina Tarsis, Center for Art Law, Moderator

10.30-11.00: COFFEE

11.00-11:15: Segolene Bergeon-Langle, “Can science deliver its promises to art?”

Segolene Bergeon-Langle (FR), France’s Honorary General Curator of Heritage, is both a scientist and an art historian. A former Head of Painting Conservation in the Louvre and the French National Museums, and a former Chair of the ICCROM Council (Rome), she is presently a member of the Louvre’s preservation and conservation committee. She will discuss various restoration cases showing how scientific analysis can fail properly to understand painters’ techniques and the deterioration of paint layers when questions are inadequately framed or when the interpretation of scientific reports is inadequate. Such difficulties can be overcome when connoisseurs themselves ask for scientific analysis to clarify some problem they have encountered, or when they can examine technical reports together with their scientific partners so as to avoid otherwise possible misinterpretations.

11.15-11.30: Michel Favre-Felix, “Overlooked Witnesses: The Testimony of Copies”

Michel Favre-Felix (FR) is a painter, the president of ARIPA (association for the respect of the integrity of artistic heritage), the director of the review Nuances, and the 2009 recipient of the ArtWatch International Frank Mason Prize, will present two restoration cases, studied from the French Museums’ scientific files, illustrating how restorations fail by not heeding the testimony of historical copies. He will stress the importance of disciplined arguments and of expert guidance from art historians, in a critical approach, rather than as the endorsement of “discoveries” claimed during restorations by restorers. His cases will demonstrate how successive restorations can impose fresh and compounding misrepresentations on art when supposedly correcting previous errors.

11.30-11.45: Kasia Pisarek, “How reliable are today’s attributions in art? The case of “La Bella Principessa” examined.”

Kasia Pisarek (Poland/UK), an independent art historian and research specialist on attributions, took an MA at the Sorbonne and a PhD at the University of Warsaw. Her doctoral dissertation “Rubens and Connoisseurship ~ On the problems of attribution and rediscovery”, identified many recently fallen Rubens attributions. She will set out a number of interlocking aesthetic, art historical and technical arguments against the recently claimed attribution to Leonardo of the drawing “La Bella Principessa”, which work appeared anonymously and without provenance in New York in 1998. Her findings were published in the June 2015 Artibus et Historiae.

11.45-12.15: Discussion/Questions: Irina Tarsis, Center for Art Law, Moderator

12.15-1.15: LUNCH

Part II: Righting the Record – Diverse Experts as Authority

1.15-1.20: Introduction: Tatiana Flessas, Cultural Heritage Law, LSE Law, Moderator

1.20-1.35: Brian Allen — “Throwing the baby out with the bathwater – the Demise of Connoisseurship since the 1980s.”

Brian Allen (UK) is a former Director of Studies at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and is now Chairman of the London Old Master dealers Hazlitt Ltd. He will speak about the gradual demise of connoisseurship in academic art history (especially in the UK) over the past three decades and will consider the effect of this on the study of art history and the art market. Up to the early 1980s few questioned the importance for young art historians of acquiring the skills to determine authorship but as the discipline of art history evolved from its amateur roots in Britain so too did a determination to adopt the theoretical principles of other areas of study. Only now are we witnessing the consequences of this change of emphasis.

1.35-1.50: Peter Cannon-Brookes, “Reconciling Connoisseurship with Different Means of Production of Works of Art”

Peter Cannon-Brookes (UK) turned from natural sciences to art history and has been active as a museum curator with strong interests in conservation and security. Connoisseurship has been undermined by the decay of museum-based pre-Modern Movement scholarship leading to the growing corruption of reference collections and of connoisseurship enhanced by the detailed study of them. Can the systems of stylistic analysis evolved from the 1940s and social anthropology be reconciled with the actual processes of production of works of art throughout the ages? The business models adopted by Raphael, El Greco and Rubens are by no means exceptional, and the evident disdain of Rodin for those prepared to pay high prices for indifferent drawing-room marble versions of his compositions, encourage re-evaluation of connoisseurship as an essential tool.

1.50-2.05: Charles Hope, “Demotion and promotion: the asymmetrical aspect of connoisseurship”

Charles Hope (UK) is a former Director of the Warburg Institute and will discuss the tension that exists between connoisseurship as a type of expertise acquired by long experience and as an activity based on the use of historical evidence and reasoned argument. Will claim that, in practice, these two aspects are often in contradiction to one another, and that many connoisseurs have been unable or unwilling to provide clear arguments about how they have reached their opinions. Too often, judgements about authorship are decided by appeals to authority, and almost by vote, rather than by evidence.

2.05-2.20: Martin Eidelberg, “Fact vs. Interpretation: the Art Historian at Work”

Martin Eidelberg (US), professor emeritus of art history at Rutgers University, will discuss the reliability and fallibility of provenance and scientific analysis of pictures in determining the authenticity of paintings. Using case histories that he has gathered from his research in preparing a catalogue raisonné of the paintings of Jean Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), he will consider whether such supposedly factual data is reliable, or whether it is subjective and open to the interpretation of scholars.

2.20-2.40: Discussion/Questions: Tatiana Flessas, Cultural Heritage Law, LSE Law, Moderator

2.40-2.55: Robin Simon, “Owzat! The great cricket fakes operation”

Robin Simon (UK) is Editor of The British Art Journal and Honorary Professor of English, UCL. Recent books include Hogarth, France and British Art and (with Martin Postle) Richard Wilson and the Transformation of European Landscape Painting. He will report his discovery (in 1983) that many of the paintings depicting cricket in the MCC collection at Lord’s were fakes, most of them made by one person between 1918 and 1948 but purporting to date from the 16th century to the 20th. They had been presented to MCC by Sir Jeremiah Colman (of the mustard family) who acquired them from a variety of agents and dealers. It is quite a tale and turns, among other things, upon an ingenious manipulation of provenance.

2.55-3.10: Anne Laure Bandle, “Sleepers at auction: Boon or bane?”

Anne Laure Bandle (CH) is guest lecturer at the LSE, director of the Art Law Foundation, and a trainee lawyer at the law firm Froriep in Geneva. She wrote a PhD in law on the misattribution of art at auction and more specifically on the sale of sleepers. She will discuss the creation of sleepers at auction by means of different cases, and focus on the attribution process of auction houses and their liability when selling a sleeper.

3.10-3.25: Elizabeth Simpson, “Connoisseurship: Its Use, Disuse, and Misuse in the Study of Ancient Art”

Elizabeth Simpson (USA) is a professor at the Bard Graduate Center in New York, NY; a consulting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia, PA; and director of the project to study and conserve the collection of wooden objects excavated from the royal tumulus burials at Gordion, Turkey.She will address the use and misuse of connoisseurship in the study of ancient art, the scholarly and methodological divides between archaeology and art history, and the current trend away from connoisseurship in the study of ancient art and artifacts. She will also show how connoisseurship is used to fabricate narratives for looted objects in order to validate unprovenienced works in private and museum collections.

3.25-3.45: Round table discussion: Tatiana Flessas, Cultural Heritage Law, LSE Law, Moderator

3.45-4.15: TEA

Part III: Wishful Thinking, Scientific Evidence and Legal Precedent

4.15-4.20: Intro by Session Moderator, Charles Hope.

4:20-4.35: Irina Tarsis, “Reputation is no Substitute to Due Diligence: Lessons from the closure of the Knoedler Gallery (1857-2011) ”

Irina Tarsis (USA), is an art historian and an attorney based in Brooklyn, NY. Founder and Director of Center for Art Law, Ms. Tarsis is an author of multiple articles on the subject of restitution, provenance research, book history and copyright issues. With degrees in International Business, Art History and Law, in her practice Ms. Tarsis focuses on ownership disputes surrounding tangible and intangible property. She will discuss the history of the Knoedler Gallery that closed after more than 160 years in business having sold a cache of misattributed forgeries. Short of a dozen lawsuits were brought against the principles and staff of the Gallery for selling works attributed to the blue chip artists. Ms. Tarsis will discuss the responsibilities of dealers, collectors and art advisors to their clients and the scholarship when handling art in business transactions.

4:35-4.50: Nicholas Eastaugh, “The Challenge of Science: Does ‘Fine Art Forensics’ Really Exist?”

Dr Nicholas Eastaugh (UK), Founder/Director, Art Analysis and Research Ltd., London, originally trained as a physicist before going on to study conservation and art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, where he completed a PhD in scientific analysis and documentary research of historical pigments in 1988. Since 1989 he has been a consultant in the scientific and art technological study of paint and paintings. A frequent lecturer, he is also a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Oxford. In 1999 he co-founded the Pigmentum Project, an interdisciplinary research group developing comprehensive high-quality documentary and analytical data on historical pigments and other artists’ materials. This led to the publication of The Pigment Compendium in 2004, which quickly became a standard reference text in the field. In 2008 he identified the first of the forgeries to be recognised as by Wolfgang Beltracchi, the now infamous ‘Red Painting with Horses’.

4.50-5.05: Megan Noh, “Trends in Authentication Disputes”

Megan E. Noh (USA) is the Associate General Counsel of Bonhams, one of the world’s largest international auction houses. Based in the New York office, Ms. Noh practices in a global hub for art transactions, and is uniquely poised to observe the numerous transactions conducted by Bonhams which require its specialists’ assistance with the authentication process, as well as the growing body of caselaw and legislative efforts emerging from this key jurisdiction. Ms. Noh’s presentation will cover trends in authentication disputes, including the cessation of artists’ foundations and authentication boards to issue opinions confirming attribution, as well as increased litigation and reliance of parties on scientific evidence and testimony. She will also elucidate the position of auction houses as a liaisons or “middlemen” in this process, facilitating the flow of information as between collectors (sellers and buyers) and third party authenticators.

5.25-50: Final Discussion/Questions: Charles Hope, Moderator.

5.50-5.55: Closing Remarks: Irina Tarsis, Center for Art Law.

6.00-7.30: RECEPTION