The Saviour and a Stealth-Attribution

Martin Kemp and a dozen (largely mute) art historians bet the professional farm on a “from-nowhere” Salvator Mundi being an autograph Leonardo painting. On fetching $450m in 2017 it disappeared. No-one will say where it is. We now hear from a previously reliable source that it never left New York.

In February’s The Art Newspaper (“Doubly lost: Salvator Mundi fails to show up at the Louvre”) Professor Martin Kemp brings no news on the disappeared picture that he, more than any scholar, has championed. Instead, he bemoans the Salvator’s latest humiliating no-show at the Louvre’s Leonardo blockbuster exhibition (and demotion within the catalogue to the “Cook Collection” work) for having given fresh impetus to “personalised” tweets accusing him of “intimidating academics who disagreed”, and to what he deems fake news stories by journalists who confess to him that “what they are reporting does not stand up to scrutiny”. What never withstood scrutiny is the disappeared Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo ascription. The “qualitative” case for the Robert Simon and Co. picture being a Leonardo always rested on a self-defeating stylistic argument: that some of its parts were exceptionally well painted. We predicted the approaching Louvre no-show and Kemp denied it. Now, bereft of a credible espousal of a disappeared painting’s disappeared Leonardo ascription, Kemp swishes the robe of scholarly piety and tilts at the world’s unfairness:

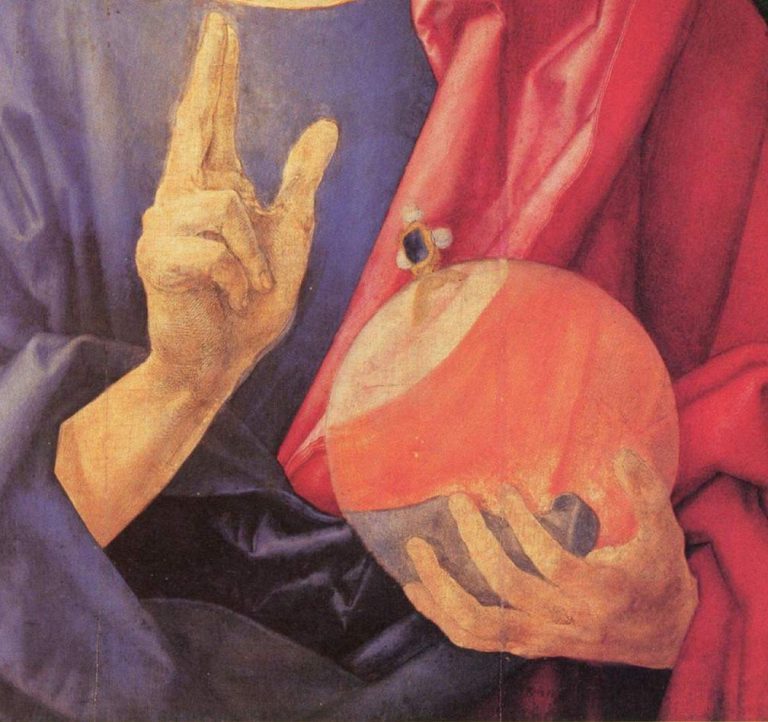

“It has become hard to look fairly at the evidence in the complex, interlocked and cumulative way that Leonardo’s paintings require. In recognising a work as by Leonardo we have the inestimable advantage that we can adduce multivalent factors from his art, theory and science. The disadvantage of this complexity is that if one factor can be picked off (convincingly or not), it can be used to taint the overall argument.” (Emphasis added.) In supposed illustration of such tainting usages Kemp contends: “A good example is the silly dispute about the optics of the sphere that Christ holds in the palm of his hand.” It was not at all a good example to cite: as discussed below, Kemp has successively held two not properly acknowledged conflicted positions on the globe’s optics.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI GLOBE’S DISTORTING OPTICS

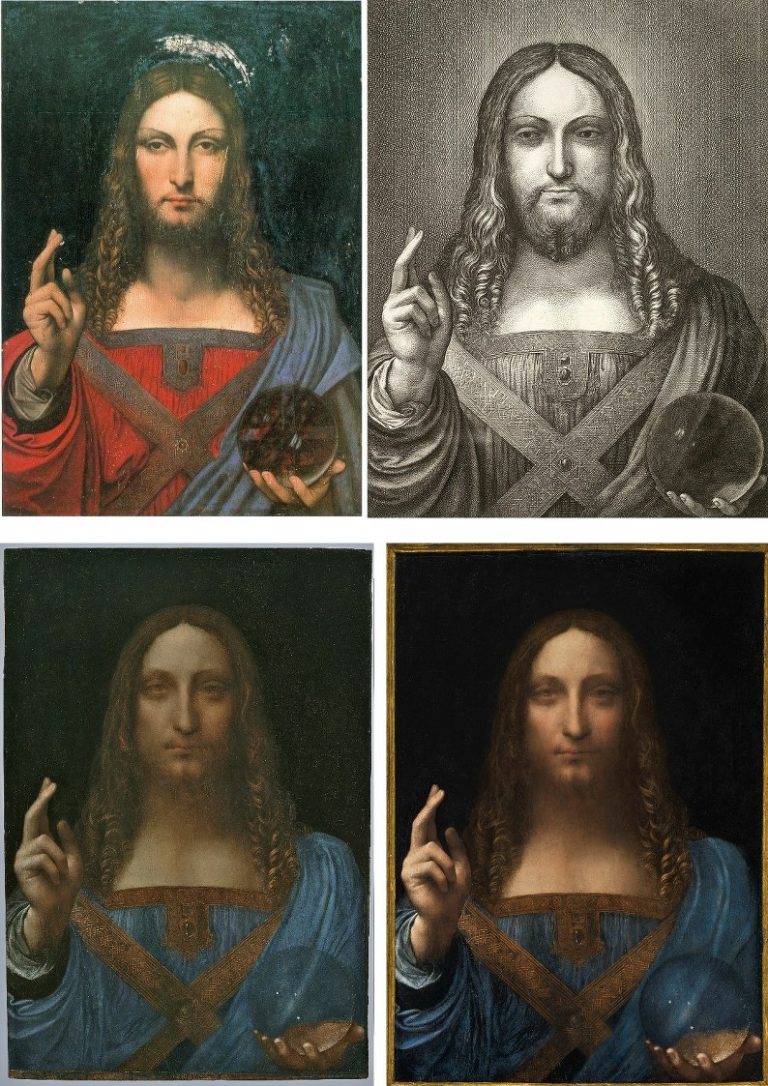

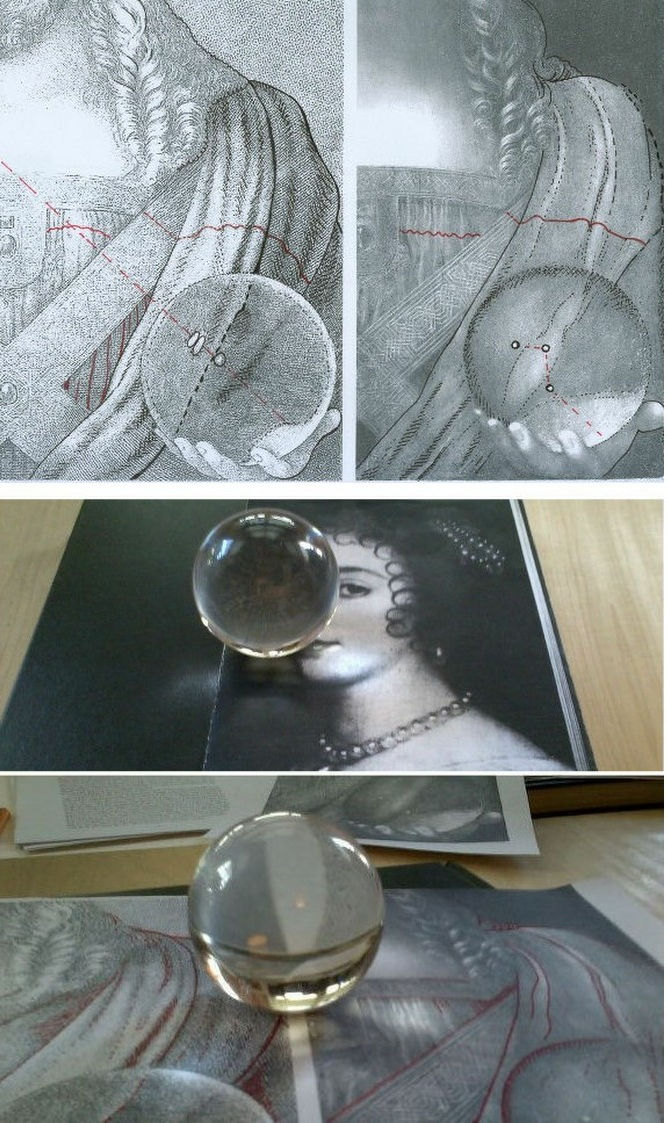

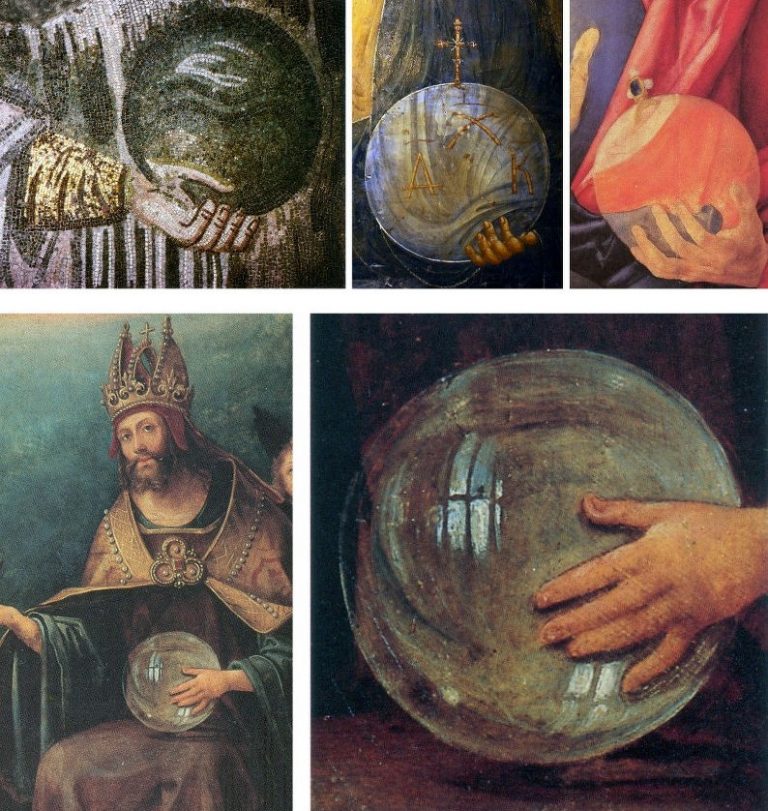

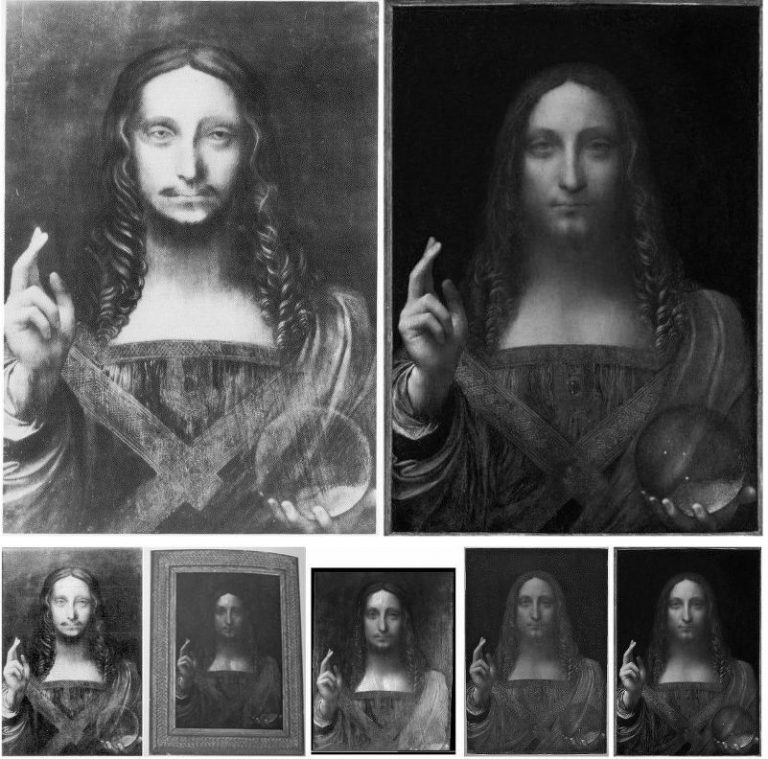

Above, Fig. 1: Bottom row, the missing Salvator Mundi, as exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12, left, and as offered for sale at Christie’s, New York, after further (covert) restoration at New York University in 2017; top row, left, the “de Ganay” Salvator Mundi which was proposed in 1982 (unsuccessfully) as the original Leonardo prototype painting; the Wenceslaus Hollar 1650 etched copy of a painting then believed to be Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi. Both candidate paintings were said to have been the subject of Hollar’s copy.

A CONFIDENTIAL INVITATION TO A SELECT COMPANY OF SCHOLARS

In March 2008 Martin Kemp was invited by the then new director of the National Gallery, Nicholas Penny, to join a small and select group of scholars to examine the Salvator Mundi painting – “We are only inviting two or three scholars”. The invitation was accompanied by the disclosure that scholars at the National Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, were already “convinced that it is Leonardo’s original version”. Kemp responded immediately to the picture’s “vibration” and the extent to which “Signs of Leonardo’s magic asserted themselves.” He warmed to the New York art dealer, Robert Simon, “the custodian of the picture (whom I later discovered was its co-owner)…All I knew at this stage was that it was being represented by Robert Simon. He told me it was in the hands of a ‘good owner’ who intended to do the right thing by it, and I did not inquire further…” Kemp decided to research “every aspect of the Salvator Mundi” which had “seemed at first sight to resonate deeply with key aspects of Leonardo’s science of art and his views of the cosmos.” In 2019 Simon said of that National Gallery meeting: “Attribution seemed not to be an issue. There was no debate.” He further discloses that even as Penny was sending his invitations to the non-debating examination (- which occasion Ben Lewis has fleshed out admirably in his 2019 The Last Leonardo), he had dispatched Luke Syson, the National Gallery curator of its forthcoming Leonardo show, to New York, to view the Simon-fronted Salvator. Kemp reports that shortly before the 15 November 2017 sale of the Salvator Mundi at Christie’s, New York, “I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.”

THE DISCOVERED OPTICS OF TRANSPARENT GLOBES

It is better practice for scholars to report what artists did do than to pronounce on what they would not have done. In his 2018 Living with Leonardo account, Kemp implies that he swiftly shifted position on the orb’s refractions during his theoretical journey on optics. In truth he had abandoned one position and adopted its antithesis. He recalls his early 2008 flush of excitement: “The most satisfying facet of my own research concerned my hunch that the globe was made of rock crystal…I had toyed with the idea that the double image of the heel of Christ’s right hand visible through the sphere might be the result of a double refraction characteristic of rock crystal; but the optics would not work. The apparent doubling is almost certainly another pentimento.” In 2018 (and therefore when speaking from his later adjusted position) Kemp advised:

“We should remember that Leonardo was drawing on his knowledge of rock crystal to devise a large sphere for Christ to hold – he was not making a ‘portrait’ of an actual sphere, nor was he following all its optical consequences to their logical conclusions. I have been asked on more than one occasion why the drapery behind the sphere is so little affected by what is, in effect, a large magnifying lens. The answer, in a word, is decorum; that is to say, pictorial good manners…Leonardo’s paintings remake nature – not only in accordance with natural law, but also in obedience to the rules that govern functioning images. He would not have disrupted the efficacy of the painting as a devotional image.”

His enthusiastic researches grew fast: “By early November 2008 I had a substantial essay of more than 8,000 words in draft, albeit with more research to conduct. The draft expanded as months went by. At one point it was entitled ‘New Wine in an Old Bottle’, to acknowledge that Leonardo had endowed a very traditional format with radically new features.”

THE NOVEMBER 2011 NATURE MAGAZINE (- “Art history: Sight and salvation”)

Those researches had been earmarked for a book of essays to be published by Yale University Press and sold at the National Gallery’s 2011-12 blockbuster exhibition, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan”. When that book failed to materialise Kemp, ever media-savvy, “turned to outlets that would deliver in time for the opening of the exhibition – not for the full research, but to get across some key points. The outlet over which I had most control was the regular column I was then writing in the science magazine Nature. There was enough science in the topic to justify the inclusion: not only the fruits of the scientific examination, but also Leonardo’s optical ingenuities and the cosmology of the crystalline sphere. The essay appeared on 10 November [2011], one day after the opening of the show.”

At that date Kemp was still holding to his initially gratifying hypothesis of materially refracted images petrified within the depicted crystal orb. In the November 2011 Nature, he specifically noted: “It seems that he [the artist] observed the double refraction produced by calcite. The heel of Christ’s hand exhibits two distinct contours, not in this case due to a change of mind.” Thus, three years on, Kemp was still “toying” with the idea that the orb depicted naturally generated refractions at the moment when the National Gallery exhibition opened and after the publication of its catalogue. What would induce an abandonment of that position? For that matter, why did the hand, as seen through the globe, change between 2011-12, when at the National Gallery, and 2017, when about to be sold by Christie’s, New York? (See Fig. 5, below).

THE BIG FLIP AND A PROVENANCE DAISY-CHAIN

Two days after publication of Kemp’s article the Times published our first intervention in which we noted that in 1650 Wenceslaus Hollar had copied refractions in the drapery seen through the orb in a painting believed at the time to be by Leonardo (see above, left, Fig. 2). Neither Kemp nor the National Gallery responded to the letter even though this optical discrepancy carried lethal provenance implications for the National Gallery’s (mysteriously owned) then-attributed Leonardo Salvator Mundi: if that painting showed no such deflected drapery, it could not have been the version copied by Hollar, as was claimed in the exhibition catalogue entry by its National Gallery curator, Luke Syson, (albeit on the borrowed researches of Robert Simon, who in turn had drawn on the not always substantiated researches of Joanne Snow-Smith who, in 1982, had proposed another Leonardo school variant – the “de Ganay” picture, top left, Fig. 1 above – as the original prototype painting). If the Simon-fronted Salvator had not been copied by Hollar then there could be no claims of English or French royal connections and, in consequence, there would be no record of the painting before 1900, when it entered the Cook Collection in England – from which collection it would be sold in 1958 for £45…to be picked up by Simon and Co. in the USA for $1,175 in 2005. In short, the Gallery had no historical support for its claim that this was a “lost” original autograph prototype painting for the very many and various Salvator Mundi paintings generated within Leonardo’s school.

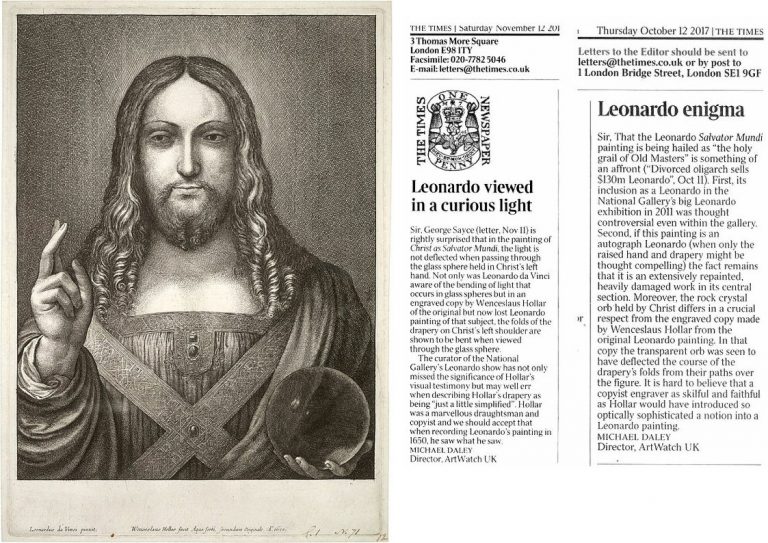

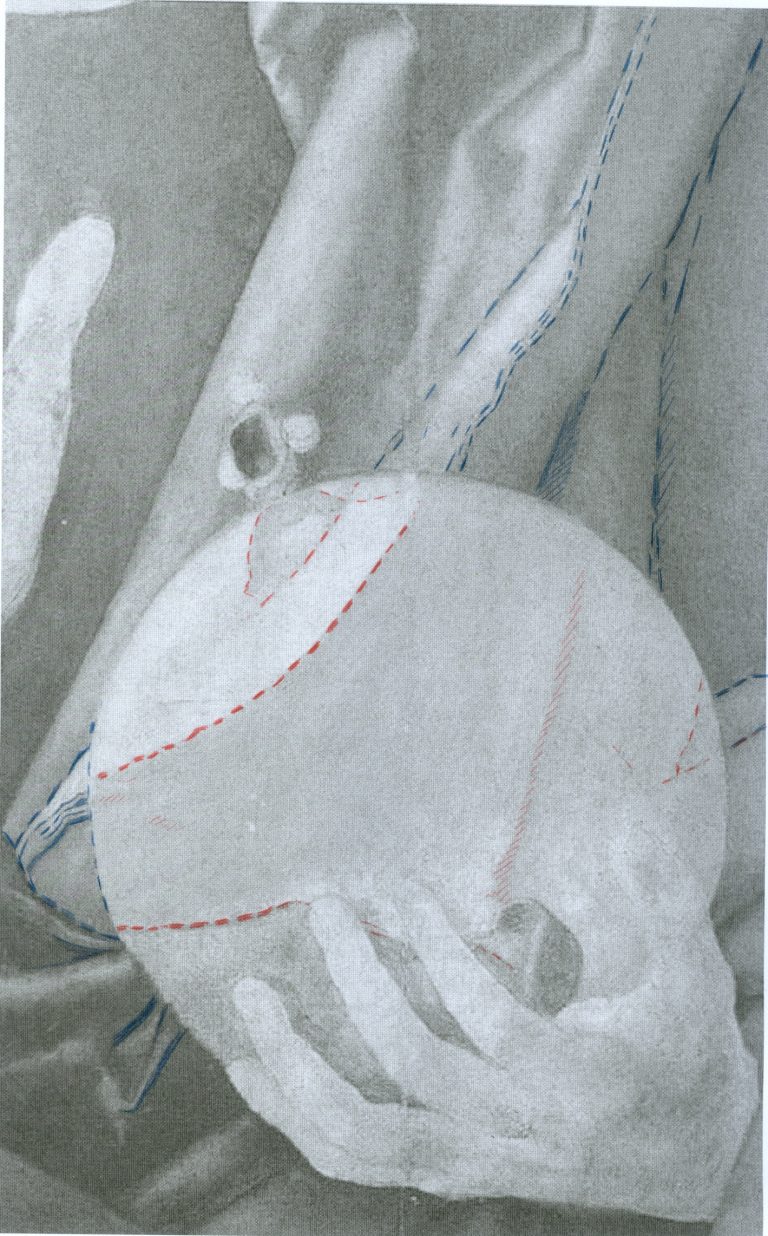

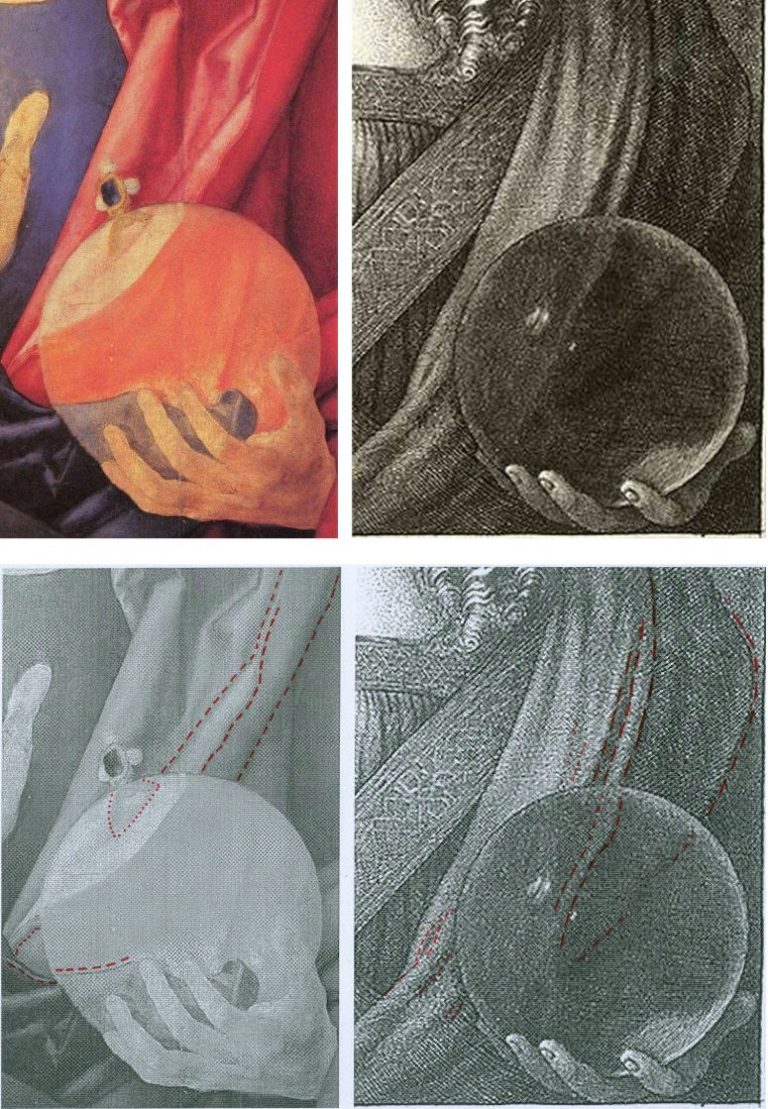

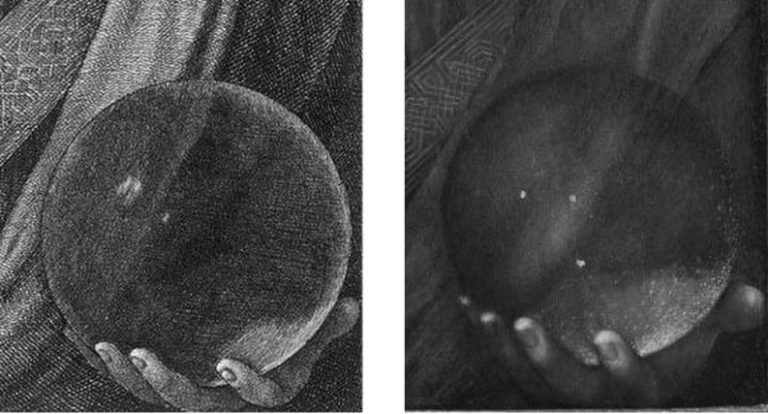

Above, Fig. 3: Left, a detail of Wenceslaus Hollar’s copy showing refractions of drapery seen through the orb; right, a detail of the Salvator Mundi painting showing no refractions of drapery. This image shows the painting not as when exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12 but as when offered for sale in 2017 after further (covert) restoration carried out at New York University. Note here the radically different depictions of the hands holding the orb and the way light had accumulated around the circumference in Hollar’s orb.

Although our letter elicited no response, in the next issue of Nature, Kemp’s comments on the orb’s optical properties came under explicit technical challenge. On 21 December 2011, five weeks into the exhibition, Nature published an exchange between Professor Kemp and a Dutch scientist, André J. Noest, who rejected Kemp’s claim that the double contour of the heel of the hand was the product of a double refraction within a calcite orb and did so precisely on the grounds that: “The painting shows no optical distortions in the folds of the clothes, for example, as would be expected from refraction by an orb of calcite, quartz or glass, or even a water-filled glass vessel.” Moreover, “The double contour of the hand continues slightly outside the orb, hence it could be due to a previous stage of the painting, or pentimento. The absence of refraction or reflection effects suggests that the orb depicts an idealised celestial sphere, with the painted specks on its surface representing heavenly bodies.”

Kemp immediately caved: “As far as we can tell, given the damage to the Salvator Mundi, the garments behind the sphere are indeed undistorted”. While so-saying he again made no reference to the contrary testimony of Hollar’s copy, even though, on 10 November 2011, he had written:

“The second variety of ‘scientific’ evidence is particular to Leonardo. He insisted that painting is a science — it relies on a systematic body of knowledge based on a deep scrutiny of cause and effect in nature. He saw painting as ‘the sole imitator of all the manifest works of nature … which with philosophical and subtle speculation considers all manner of forms … all of which are enveloped in ‘light and shade’. For any painting to be recognized as a Leonardo, it has to bear witness to such mighty ambitions. The Salvator Mundi, he held, “does so on two main optical counts…” One count was:

“The other optical effect is unique to this painting, both in Leonardo’s work and in the Renaissance more generally. The orb is not the standard globe of the world. It is translucent and glistens internally with little points of light. These are not the spherical bubbles found in glass, but are the kind of cavity inclusions (small gaps) that appear in some specimens of rock crystal and calcite. Leonardo, we know, was considered an expert in such semi-precious materials. It seems that he observed the double refraction produced by calcite. The heel of Christ’s hand exhibits two distinct contours, not in this case due to a change of mind. (Emphasis added.)

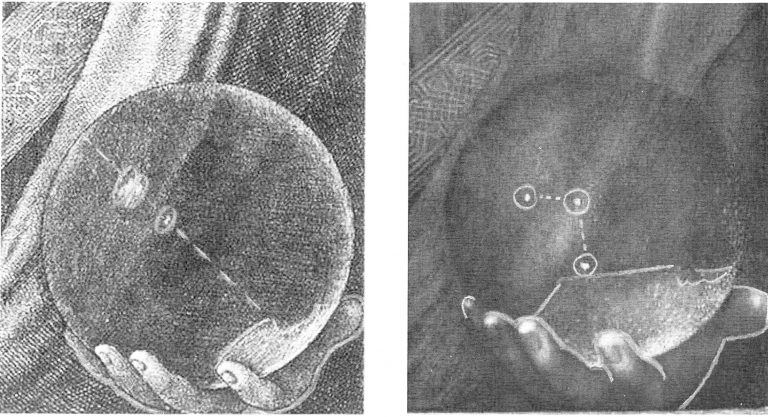

KEMP’S DISCUSSION OF THE ORB’S OPTICAL PROPERTIES

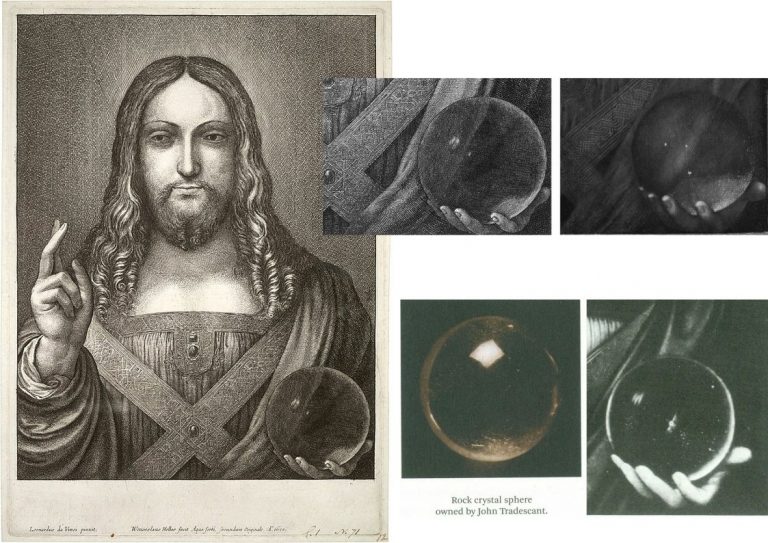

In 2018 in his memoir Living with Leonardo, Kemp reproduced just two images of orbs, as above, Fig. 4, top and centre, and wrote: “I had toyed with the idea that the double image of the heel of Christ’s right hand visible through the sphere might be a double refraction characteristic of rock crystal but the optics would not work. The apparent doubling is almost certainly another pentimento.” Again, he made no acknowledgement of Hollar’s testimony. Nor did he address the striking similarities of the Tradescant orb, as he photographed it, with that copied by Hollar and that encountered in the Worsey picture (Fig. 4, above, bottom right). Similarly, he later declined to address the differences evident in the orb between 2012 when it left the National Gallery and 2017 when offered at Christies – see Fig. 5 below:

BODIES OF COMPARATIVE VISUAL EVIDENCE

None of the many Leonardo school Salvators shows the hand in the massive and double-edged manner of the now-disappeared version (as above at Fig. 5). Just as the illumination seen in Hollar’s orb, Fig. 6, below, left and top, is strikingly similar to that seen in the lost Worsey picture’s orb, so too in both images the hand holding the orb is shown distorted and compressed towards the orb’s circumference.

While Kemp seems proud to have been the first to suggest a rock crystal orb, an orb’s material composition is of little artistic consequence in terms of its capacity to distort. Our small solid glass orb shown below at Fig. 7, demonstrates in the lower image how, when an orb straddles a parallel gap between two pictures, that gap is shown (inverted) at the top of the globe as two curved, not straight lines.

EARLY AND CONTEMPORARY ORBS

Kemp’s claim that sensationalising critics make it difficult to conduct a duly “sober and systematic analysis of primary sources” seems rich. So far as we know, he has never addressed Ludwig Heydenreich’s groundbreaking 1964 study of the many Salvator Mundi pictures produced by Leonardo’s school and followers. (We published all of Heydenreich’s illustrations – including that of the lost “Worsey Collection” picture – the day before Christie’s sold the disappeared Salvator Mundi for $450 million – see “Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”.)

Kemp praises Robert Simon’s researches: “He assembled a large bank of research images, including a growing number of copies or variants which testified to the hold that Leonardo’s inventions exercised on other artists and patrons.” In the long-promised Margaret Dalivalle, Martin Kemp and Robert B. Simon book Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi, Simon acknowledges Heydenreich’s work as “The most significant publication on the subject” and “an excellent introduction to the subject”. Further he acknowledges that Heydenreich had concluded, on the very great variations present in the works, that no autograph Leonardo painting had been produced. At the same time Simon describes the Salvator Mundi, as “One of three lost paintings by Leonardo known from copies”. What had changed since Heydenreich? Simon’s researches had identified “several more painted versions and variants”, but none was considered to have approached “the quality of our painting”. In that case, the logical/stylistic problem strengthened: where bona fide Leonardo paintings exist, all copies, however variously talented their authors, can be seen to sing from a single design sheet. In this case, the more anarchically various works emerge, the less plausible they become as supposed copies of a single autograph work.

No case – and even less any visually-comparative case – has been compiled to show the Simon and Co. painting had served as a prototype for all versions. Simon tacitly concedes this methodological lapse when saying: “this image of Christ was more of a curiosity, since relatively few versions of the Salvator Mundi composition were known and, unlike copies of the Mona Lisa, there was little consistency in the details among them; each seemed almost an interpretation of the subject rather than a faithful reproduction of a common original.” That central problem persists at macro and micro levels: if Leonardo had painted a large hand with a horizontal thumb, the tip of which was cropped by a pre-fixed frame, why did no other painting echo or follow his example? In his catalogue entry, Luke Syson says of this hand that-no-one-copied, that although it is seen through a crystal orb, “Christ’s hand seems miraculously undistorted” and that “Leonardo has therefore created an object which would be understood as a piece of divine craftsmenship, but still be his own invention.”

Kemp had checked in the photographic library of the Warburg Institute to see what other artists had made of the orb in Salvator images: “There was quite a variety. Brass globes were common, sometimes with a cross on top. Some took the form of terrestrial globes with indications of land and seas. Others were made of glass, and a few contained little landscape vistas. In two Venetian examples Christ placed his hand on an ample glass orb – appropriately enough, given Venice’s pre-eminence in glass manufacture. But none seemed to show a crystal sphere.”

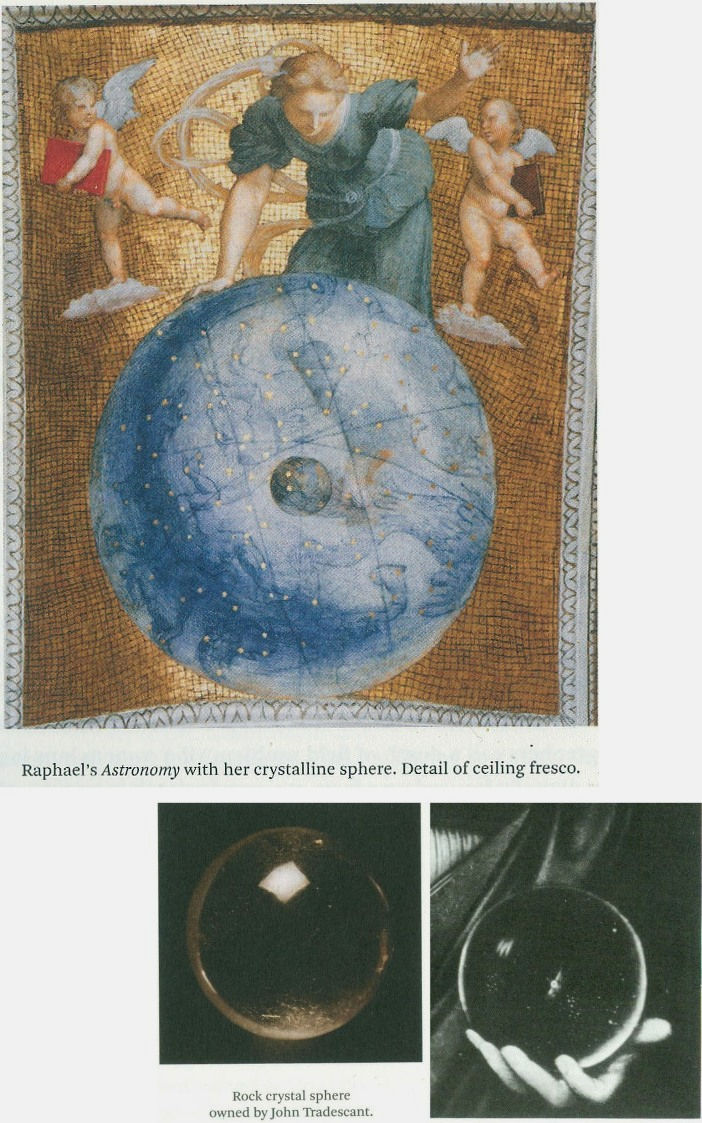

Much as Kemp hugs the especial qualities of crystal, with regard to the supposed prohibition against artists indicating refractions within transparent orbs (on grounds of propriety and decorum) the nature of the material – glass, crystal or quartz – is immaterial: if an orb gives rise to spherically-determined distortions it gives rise to spherically-determined distortions. (The mention of Venetian glass-making skills might be considered germane to this subject.) This attribution was made on a manifestly incomplete programme of studies: every time Kemp explains absences of refraction on the Simon Salvator by invoking “decorum” and “pictorial good manners” he ignores the testimony of Hollar who had copied defractions on a painting then judged to by Leonardo in 1650. Those deflections on that carefully dated 1650 etching are both material and historic facts. Where is that painting? Had Liz James’ splendid and technically illuminating 2017 book Mosaics in the Medieval World been published earlier, Kemp might have appreciated that even devout Byzantine mosaic-makers had no qualms about depicting refractions within Celestial Globes.

TRANSPARENT ORBS FROM BYZANTIUM TO DURER

Above, Fig. 8: Left, The Archangel Gabriel, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, ninth century; top, an apse mosaic depicting the Mother of God and her Child and the archangels Michael (left) and Gabriel at the sixth century Church of the Panagia Angeloktistos, Kiti, Cyprus.

Above, Fig. 9: the orb held by the Archangel Gabriel at Hagia Sophia.

Concerning decorum, how would Kemp account for the above Byzantine mosaic image of a transparent orb held by the archangel Gabriel in which the thumb and part of the supporting hand are visible through the orb; in which a deflected image of the gold sleeve is present; and in which the straight-edged, vertical feathers of Gabriel’s wing have been rotated horizontally and given wavy form when viewed within the orb? In the two sixth century orbs below at Fig. 10, as held respectively by the archangels Michael and Gabriel, four fingers are shown through the orb in the one and the thumb and part of the hand in the other. Has consideration been made of the longevity of depictions of transparent orbs in sacred Christian images?

In Fig. 11, above, we see part of Durer’s (unfinished) Salvator Mundi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Have Simon and Kemp – not to mention the Met’s own declared curatorial and conservation supporters of the attribution – not considered the possible relationships between the two great contemporary artists, Leonardo and Durer?

In Fig. 12, we see that Durer showed defractions of drapery within his transparent orb. Was he aware before 1505 of such a usage in Leonardo? Was Leonardo aware of Durer’s depiction? Was this (then-in-progress work) one of the panels Durer is known to have taken to Venice in 1505? Could Leonardo have known of this incomplete, in effect, part-coloured drawing of a Salvator Mundi with a large refractions-generating transparent orb?

Regarding Fig. 13, above, how should we consider the coincidences between Durer’s Salvator Mundi of 1505 and Hollar’s 1650 copy made in Antwerp after a Salvator Mundi then said to be by Leonardo?

Above, Fig. 14: The compilation of three hands above highlights the paucity of scholarship that accompanied the sustained and effectively covert drive to have the Simon and Co. Salvator Mundi accepted in the 2011 National Gallery exhibition as an autograph Leonardo. Ben Lewis has established that the hand on the right is found on a Salvator Mundi painting now given to Giampietrino. It lives in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow, and is incontrovertibly the Salvator Mundi that was once in Charles I’s collection, where it was given to Leonardo. Simon, Kemp and others have held that “their” Salvator Mundi was that recorded Charles I painting and that it had been copied by Hollar almost a century and a half later. Self-evidently the Pushkin Salvator cannot have been copied by Hollar because it is an entirely different – and more obviously Leonardo-like – compositional type. Without anticipating Jacques Franck’s forthcoming comments on the mis-drawn hand in the centre above, we can surely see here that in 1505 Durer and, perhaps a little later, Leonardo’s student Giampietrino had both made a better fist of drawing a Blessing Hand than had the Master of the Simon/Kemp and others’ Salvator Mundi?

Michael Daley, Director, 5 February 2020

UPDATE – 11 February 2020:

Collective Failures of Due Scholarly Diligence and Visual Acuity

Following publication of the above post some contend that the former Cook Collection Salvator Mundi painting failed to leave New York after the 15 November 2017 sale because the successful bidder declined to pay in full; and, two further Byzantine orbs showing refracted draperies have emerged, as shown and discussed below. While the monumental mystery of this painting’s whereabouts constitutes a globally shared preoccupation, it is not the essential professional concern in this affair. Before auctioneers entered the scene, a seemingly self-selecting group of international scholars by-passed all means of open appraisal, contention and debate – and then disparaged all subsequent critics. In our view, the magnitude of this particular visual misreading by a group of leading art historical figures rivals that encountered forty years ago on the restoration of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes.

Above, Fig. 15: The historical sequence of previously un-noted transparent orbs showing refracted drapery grows. A correspondent suggests that the orb encountered on the 14th Century icon of the Archangel Michael in the Byzantine & Christian Museum in Athens (as above, top centre, and below at Fig. 16) might have been known to Leonardo. If that seems unlikely – the Athens museum links the icon to a mural cycle of 1315-1320 in a Constantinople monastery – certainly, its existence might not have been expected to elude scholars today who enjoy full access to university libraries and the internet. An earlier German picture, the Athenaeum’s 1514 Coronation of the Virgin by Hans Süss von Kulmbach (above) not only contains an orb showing refracted drapery but one that appears to float and cast a shadow on God the Father’s lap – here the hand seems to be holding the orb in place rather than supporting it. In his 1998 book On Reflection Jonathan Miller noted the anomalous reflections of a window on the orb and toyed with the thought that they might have carried an allegorical function by symbolising the idea that the universe itself is a church, but he added, “they do look like the windows in the artist’s studio”. Indeed, and the upper reflection appears even to show a safety catch. It might be thought inconceivable that Durer would not have known of this orb and its treatment: von Kulmbach being the former Durer apprentice who took over the production of his master’s altarpieces in 1510. Durer, who likely had designed this orb, could not have been indebted to Leonardo and his school on transparent orbs – which underlines the unaddressed question: were they apprised of the great German master’s earlier engagement with such orbs?

Above, Fig. 17: Of course, any scholar might overlook a particular historic work. The real professional lapse here lies in a group-failure to recognise the import of manifestly un-like images. For example (and as mentioned above) it was crucial to the recent campaign to upgrade the Cook Salvator Mundi that it be accepted as the one-time subject of Hollar’s 1650 etched copy of a Salvator Mundi painting then thought to have been painted by Leonardo. If we allow for the fact that even so good a copyist as Hollar might not be expected to reproduce faithfully every detail of a relatively large painting in small etching; and, even, if we make allowances for what are nowadays euphemistically described as paintings’ “conservation histories”, no visually alert expert professional should have believed that Hollar might have copied his orb/hand, as above left, from that found on the former-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi, as shown above, right. Given the scale on which Hollar worked, the challenge of perfectly reproducing the elaborate geometric knot-pattern decorations on the stole might seem like an invitation to fudge or dissemble but, in truth, we see that Hollar contrived, in-miniature, a complex geometric pattern that is remarkably close in spirit and appearance to that encountered on the Cook Leonardo school Salvator Mundi painting. Given that close correspondence, it is simply inconceivable that Hollar derived his image from the orb/hand present on the (now-disappeared) painting, as seen above right.

A CATALOGUE OF ERRORS AND MISSTEPS

Even when the originally claimed derivation was being announced by Luke Syson in the catalogue entry to the 2011-2012 National Gallery Leonardo blockbuster exhibition, certain reservations were declared. In this regard Syson’s entry itself constitutes a catalogue of art historical missteps. First, he holds that it had “always seemed likely” that Leonardo had painted such picture. In a footnote supporting his claim, Syson states that he was writing on the authority of a then-pending and more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others:

“I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be published in a forthcoming book.” That book notoriously did not materialise until 2019. It is titled Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & The Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts. In his introduction, Simon claims it to be “the first to treat the painting monographically.” Some monograph: Modestini’s contribution was dropped – as was that of Gutman. Thus, there is no horse’s-mouth account of the picture’s long and various campaigns of restoration and no technical reports are carried. As also mentioned above, Simon acknowledges that, on the historically most thorough examination of the available evidence, Professor Heydenreich had concluded that Leonardo had not painted a Salvator Mundi.

Ill-logic has stalked this Leonardo ascription. When discussing an earlier claim that Hollar’s etching had been made after a different Leonardo painting then being advocated as a Leonardo original, Syson sensibly notes that “Hollar might very well have been copying a copy.” He further admits that the combined facts of the Hollar copy and the many workshop painted copies do “not constitute proof that Leonardo painted a Salvator Mundi.” Syson even nods towards Heydenreich’s thesis: “it has sometimes been argued that [certain…] drawings might have formed the basis for one or more finished designs – perhaps cartoons – that he [Leonardo] made expressly to be copied by pupils but with no primary version by the master himself.” But then against that, and in emulation of Simon, Syson takes the stripped-down and re-painted former Cook Collection Salvator Mundi picture to constitute proof in itself that Leonardo had painted his own prototype for all other copies after all, and that this version comprises the now-supposed and claimed “lost” Leonardo: “The re-emergence of this picture cleaned and restored to reveal [sic] an autograph work by Leonardo, therefore comes as an extraordinary surprise.”

In part, the surprise to Syson stems from the fact that a correspondence between the Cook picture and the Hollar copy is not complete: “Though Hollar’s Christ is very slightly stouter and broader, the two images coincide almost exactly” even though “The draperies are just a little simplified and there is no glow of light around Christ’s head.” Among the listed similarities, “the knot-pattern ornament on Christ’s crossed stole and the border of his vestment are very similar indeed, a particularly important consideration given that this ornament is the aspect most susceptible to change in the different surviving versions.” Now, if the perceived similarities between the Hollar copy and the Cook picture count in the latter’s favour, does it not follow that their dissimilarities should be counted in the latter’s disfavour? It seems that this $64,000 (-in fact $450 million) question may never have been asked by those who formed an orderly queue to ascribe the much remodelled former Cook painting to Leonardo himself. In our view that apparent omission is the gravest and least explicable of all: in the visual arts generally and in the making of ascriptions particularly, differences, no less than similarities, are of the essence. We have itemised the many dissimilarities previously. In Fig. 18, below, we pare the question down to a single comparison of the Hollar and Cook globes so as to pose the simple question: if this comparative image below constituted a newspaper “Spot the differences” quiz, how many differences would you be able to identify? To make the question easier, we have outlined some of the more massive and glaring discrepancies in white chalk.

The Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Not “Pear-shaped” – Dead in the water

The attribution of the world’s most expensive painting – the $450 million Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi – has collapsed under the combined weights of two scholars’ findings and the picture’s own artistic and art historical implausibility. Having disappeared immediately after its world-record sale at Christie’s, New York, in November 2017, this Leonardo-in-hiding is also mired in allegations of a joint involvement in the sale by presidents Trump and Putin. The toxic proximity of those two heads of state is a matter of intense national political concern in the United States where high-level official investigations are underway – as are a number of legal actions concerning auction house buyer/seller conflicts of interest. As those disputes play out, we consider the workings of today’s art historical and art market interface.

THE ART CRITICAL CONTEXT

In the 1990s we claimed common failures of connoisseurship in bad restorations and misattributions but thought the latter less serious because potentially correctable. That distinction is dissolving as increasingly many upgrading attributions are made on the back of “improving” restoration transformations. Generally speaking, connoisseurship shortcomings are evident in failures to detect outright fake old masters and in too-ready acceptances of elevated restoration-enhanced school works. Purpose-made fakes are closely related in their fabrications to the painted “recoveries” of supposedly original authentic appearances on stripped-down pictures. (See “A Restorer’s Aim – The fine line between retouching and forgery”.) The fakery of artificially distressed new paint and false painted craquelure is common to routine restorations; to restoration-assisted upgrades; and, to outright fakes. On the additional, extraordinary rise of the “painted-in” insinuation of computer-generated virtual reality into old master pictures, see “The New Relativisms and the Death of ‘Authenticity’” and Fig. 4 below.

Above, Fig. 2: Top row, the Metropolitan Museum’s Duccio Madonna and Child, as seen in 1904 and in 2004 (when sold for c. $50 million); above, the Leonardo Salvator Mundi as seen in c. 2005 and in 2017 (when sold for $450 million).

Above, Fig. 3: Top row, the present Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi painting as seen in 1912 and when sold in November 2017. Bottom row: as at the same dates but showing some intermediary restoration states.

Attributions, like restorations, are made in socio-cultural contexts. Here, we examine the marketing of the upgraded Salvator Mundi with reference to the marketing of a picture that had received a spectacular upgrading a century earlier – the Metropolitan Museum’s 2004 acquisition of a tiny Duccio Madonna and Child. In both cases we see elevations of studio works that had first emerged at the beginning of the 20th century and were converted through restorations into claimed major autograph works. In both cases, when viewed dispassionately and art critically, the upgraded works are seen to stand anomalous within their allotted oeuvres. In both cases, the elevations thwarted the articulation of potentially more fruitful and better informed art historical narratives.

In studying the two cases we encounter errors of connoisseurship that rest on plain failures to look; failures to discern; and failures to make use of the sharpest art critical tool in the connoisseur’s tool box – the humble photo-comparison. This methodological abstemiousness can seem wilful and perverse as much as neglectful – some disavow photo-testimony outright as a critical tool. In the visual arts, and with today’s greatly enhanced photographic means of reproduction and transmission, there can no excuse for advocates’ declining to provide visual demonstrations of claims made in support of attributions or restorations.

THE PROBLEMS OF SCHOLARLY ADVOCACY ON THE MARKET

Where once a respected scholar might have proposed an attribution in an academic journal or forum in anticipation of critical responses, today, at the high end of the art market, teams of professional supporters are assembled one-by-one behind the scenes prior to some Big Media Announcement of a “discovered” masterpiece. Within such procedures, successive scholars’ invitations to appraise works are inescapably compromised by awareness of already committed supporters. At a certain point of accumulated critical mass it can be felt a) tempting to join and/or b) professionally unwise to dissent openly. A sense can grow that nothing will be permitted to count as evidence against that which has been collectively endorsed, and that any opposition will incur a risk of being dubbed a “hostile” party. At the low end, the trade euphemism for the many restoration-enhanced upgrades is “a sleeper”.

RECENT ARTWATCH WARNINGS AND ENGAGEMENTS

ArtWatch warnings on the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo attribution: 1) On 11 November 2011 we pointed out (letter, the Times, Fig. 5 above) that the Salvator Mundi painting then on exhibition as a Leonardo at the National Gallery, and that is now the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture, lacked a sophisticated optical effect copied in 1650 by Wenceslaus Hollar from a painting then thought to be a Leonardo. 2) On 19 October 2017, nearly a month ahead of the 15 November sale of the Salvator Mundi at Christie’s, New York, we objected (in the Guardian) that the painting was inconsistent with Leonardo’s depictions of figures; that it lacked the sophisticated optical effects copied by Hollar; and, that there was insufficient evidence to support a Leonardo attribution. 3) On 14 November 2017, the day before the Salvator Mundi sale at Christie’s, New York, we warned that the provenances compiled by the National Gallery in 2011 and Christie’s in 2017 were unsupported, inflated and overly-reliant on then (and still) unpublished researches of one of the work’s first owners – see “Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”.

CHRISTIE’S MARKETING OF A SALVATOR MUNDI AS A “MALE MONA LISA” AND AN EARLIER CASE

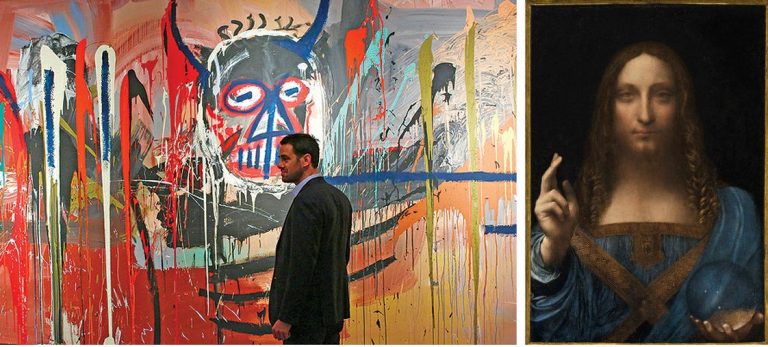

Above, top, Fig. 6: Left, Loïc Gouzer, co-chairman of Americas post-war and contemporary art at Christie’s stands next to “Untitled” by Jean-Michel Basquiat during a Christie’s, New York, press preview; right, the Salvator Mundi when sold as a Leonardo at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 – the last time it was publicly seen. (It is presently rumoured to be in a Freeport storage depot in Switzerland.)

Gouzer, who is leaving Christie’s, had claimed: “Young people look at Leonardo the same way they look at Basquiat.”

The day after Christie’s 15 November 2017 sale of the $450million Salvator Mundi, Thomas Campbell, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, observed that the “eye-popping” price was no surprise in a market where “speculation, marketing and branding have displaced connoisseurship as the metrics of value”.

Todd Levin, an art adviser, told the New York Times: “This was a thumping epic triumph of branding and desire over connoisseurship and reality.” (See “How Salvator Mundi became the most expensive painting ever sold at auction”.)

George Goldner, former chairman of drawings and prints at the Metropolitan Museum, has said the allure of the Salvator Mundi “has nothing to do with art and everything to do with money,” and that “If you were to spend $450m on a rare car or diamond and put it on display, a lot of people would come to see it. If the Salvator Mundi had sold for $20m, nobody would go. Any painting that sells for $450m will attract crowds for a while. Then, all of a sudden, people won’t care anymore”.

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM DUCCIO MADONNA AND CHILD

Above, Fig. 7: Three views of the Metropolitan Museum’s Duccio Madonna and Child

Goldner is right of course – who queues now to see the Met’s famous “Duccio” (Fig. 7, above) which, like the Leonardo Salvator Mundi, emerged at the beginning of the 20th century with no history? The then recently restored Duccio had been launched by Berenson’s wife (Mary Logan) and a protégé (Frederick Mason Perkins) in 1904 at a time when Florence was “a factory of forgers”, according to Federico Zeri, and with modern wire nails embedded under its ancient and battered gilded gesso. By further coincidence, both pictures arrived at the beginning of this century after long absences (1949 to 2004 for the Met Duccio, 1958 to 2005 for what is now the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi-in-storage.)

In hindsight, the sale of the $50 million Duccio in 2004 served Christie’s as a model for that of the Salvator Mundi. The task in both cases was to market as an absolutely secure blue chip autograph old master, a work that had arrived very late in the historical day, without provenance, and from within a large group of related but artistically diverse pictures. Both works were successfully presented by Christie’s, on substantial expert authority, when, on a full art critical and documentary interrogation, neither can safely be so regarded.

Although we still cannot examine the Salvator Mundi’s unpublished technical literature, with the Duccio we can (thanks to earlier generous assistance from Keith Christiansen, the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of European Paintings at the Met) examine that picture’s part-published technical literature and the under-reported means by which it had emerged from an antiques shop a century earlier and was, after restoration, instantly attributed to Duccio by its owner. As with the Salvator Mundi, there is no record of such a work having been produced by Duccio and no attempt has been made either to demonstrate that the Met picture was an original prototype for the many other versions of the type or to acknowledge the many historic variants themselves. Instead, five modern forgeries of the Berenson-upgraded Duccio are cited by Christiansen on grounds that they “testify to its prestige.”

THE MET DUCCIO CONTROVERSY LITERATURE:

The case for the Metropolitan Duccio has been put principally by Keith Christiansen in: the Fall 2005 Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (“Recent acquisitions”, p. 15 – “among the most important single acquisitions of the last two decades”); an October 2007 Apollo article, “The Metropolitan’s Duccio” – which was described as “the first full account”; the Summer 2008 Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin – “Duccio and the Origins of Western Painting”; also in 2008, a special Met re-printed publication, Duccio and the Origins of Western Paintings.

The case against was put by Professor James Beck in the last chapter of his 2006 book From Duccio to Raphael – Connoisseurship in Crisis, and by Michael Daley who, after corresponding with Christiansen over the attribution, published three articles in the Jackdaw magazine between November 2008 and March 2009: “GOOD BUY DUCCIO?”; “BUYER BEWARE”; “TOXIC ATTRIBUTIONS?”

FURTHER SALVATOR MUNDI AND MET DUCCIO CONNECTIONS: MARKETING THE ATTRIBUTIONS

As with the Salvator Mundi, Christie’s marketed the painting as a “Last Chance to Buy a Duccio”. Christiansen is listed by Christie’s as one of the Salvator Mundi’s supporters, as also is the Met’s chief picture restorer, Michael Gallagher, and as was Christiansen’s predecessor as paintings’ chairman, the late Everett Fahy.

When purchased, the Met Duccio had never been technically analysed. This long out-of-sight work was only subjected to technical analysis by the Met after acquisition and after challenges to its authenticity had been made by Beck and other scholars. As with the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi, the subsequent technical examination reports were not published or made available to independent scholars.

GUSH, ACQUISITIONS, SUSCEPTIBLE VIEWERS, SYCOPHANCY AND ABSENCES OF “STYLE CRITICISM”

Like Robert Simon on the Salvator Mundi, Keith Christiansen is a life-long devotee of the artist in question. His accounts of the Met Duccio have inclined towards the rhapsodic while eschewing direct engagement with style criticism. He recalls being struck on his first (2004) encounter with the Duccio at Christie’s, London, that “Like a poem or a piece of music, a great work of art – even a very small one – it has the power to cast a spell over susceptible viewers, to draw them into the world of its creator. For a few moments we were silent, each of us registering our impressions… Ever since, almost forty years ago, I first stood before the Maestà in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena, I have been haunted by Duccio’s singular gift for suggesting an ineffable, sacred presence in his depictions of the Virgin and Child, and it is this quality that first struck me – except that in this small picture there is an intimacy in the relation of mother to child that is quite different from what one finds in the artist’s public altarpieces, and the face of the Virgin is touched by a haunting melancholy even more poignant than I remembered from his larger public paintings…I knew the picture from old black and white photographs in books on Sienese painting and the two principle monographs on Duccio and his followers…There are few works of art I longed to see more than this small but astonishing picture…[which] would have been at the top of anyone’s wish list for acquisition…”

With big acquisitions museums take hyperbole and heroising gush to be in institutional order. The Met Duccio was by far the museum’s costliest ever and for a while it sparked an ecstatically uncritical hysteria. A New York restorer/dealer, Marco Grassi, for example, likened the picture’s emergence to the discovery of a manuscript score for a Mozart quartet. The world had earlier missed the chance to see it, he wrote (New Criterion, February 2005), because it was “on its way to London to be offered for sale, privately, through Christie’s.” But then, the happiest of endings:

“The Stoclet Duccio – we can now proudly call it ‘the Metropolitan Duccio’ – is an astonishing achievement…the artist places the Virgin at a slight angle to the viewer, behind a fictive parapet. She gazes away from the Child into the distance while He playfully grasps at Her veil. One must appreciate that every aspect of this composition represents a departure from pre-existing convention. With these subtle changes, Duccio consciously developed an image of sublime tenderness and poignant humanity, almost an echo of the spiritual renewal that St. Francis of Assissi had wrought only a few decades earlier…If, adding ‘strength to strength’ is a judicious policy in building collections, then, with the addition of the Duccio, its rewards will be particularly bountiful for the Metropolitan…And so, the Metropolitan’s recent arrival now rules supreme in this exalted company, and surely this could not have happened were it not for the outstanding quality of the museum’s curatorial resources. Chief Curator Everett Fahy and Associate Curator Keith Christiansen of the Department of European Paintings, in addition to Laurence Kanter, Curator of the Lehman Collection, constitute, together, a particularly prestigious concentration of scholarly expertise in the field in earlier Italian painting. No other museum can boast of a more distinguished team. One suspects that they, more forcefully and convincingly than anyone, made the case for the Metropolitan’s prodigious expenditure, and their advocacy merits our gratitude and applause…”

The celebration of “every aspect a departure” within an oeuvre is an inherently problematic and art-critically dangerous intoxication.

HOW A DREAM WISH MATERIALISED

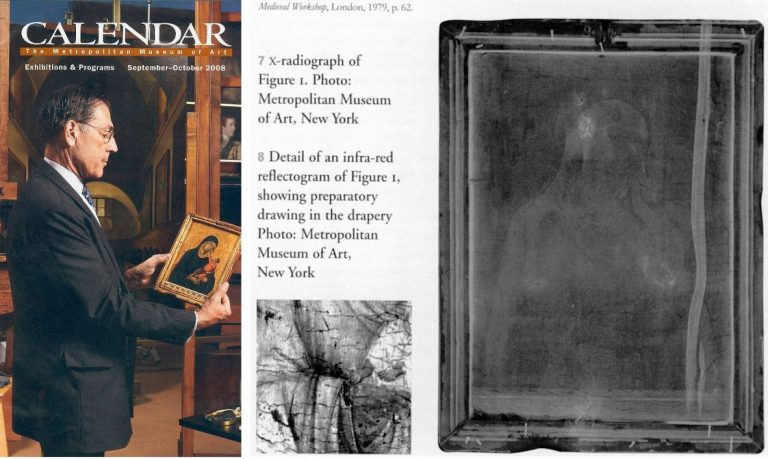

Above, Fig. 8: Left, the Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Philippe de Montebello contemplating the museum’s Duccio Madonna and Child (after its acquisition); centre, a fragment of an infra-red image of the painting, as published in Apollo in 2007; right, an x-ray of the framed Metropolitan Duccio panel, also as published in Apollo and showing the modern wire nails that no one had noticed or acknowledged.

Christiansen described how the Duccio picture was drawn to his attention in Danny Danziger’s (endlessly fascinating) 2007 Museum – Behind the Scenes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

“Nicholas Hall of Christie’s, with whom I have been friends for many years, phoned me up and said ‘I would like you to have lunch with me; there is something I’d like to show you.’ During the meal he slipped me a transparency, and I looked at it. It was a painting that had not been seen by any of the major Duccio specialists for fifty years…”

What could possibly go wrong? Nothing, Christiansen clearly thought: “…it had been in the Stoclet family and out of circulation. ‘Fantastic, how about the price? I asked. He told me. OK, I said, ‘I will deal with that later.’ And then we finished lunch.” Note, re frequently disparaging art world dismissals of photo-testimony, first, a curator had committed to the cause of a work he had never seen on sight of a single photograph; second, the Met’s director, Philippe de Montebello, would also become hooked on the painting through that photograph; third, that for over half a century, professionally-speaking, the picture’s Berenson-made attribution had been sustained on photo-testimony alone. Christiansen would later put it like this: “In 1949, [the then owner of the Duccio, the financier Adolfe] Stoclet and his wife died within a short time of each other. The collection was divided among their children, but access to it was increasingly difficult and there was even uncertainty as to whether the Duccio had been sold. The result was that a generation of scholars had to formulate their opinions on the basis of photographs, of which, fortunately, extremely good ones had long been available.”

THE CIRCUMSTANCES CONCERNING THE WITHDRAWAL FROM THE 2003 SIENA EXHIBITION

In Calvin Tomkins’ 11 July 2005 New Yorker article “The Missing Madonna”, it is said that the Met’s then head of European paintings, the late Everett Fahy, visited the Stoclets’ house in Brussels in 2002 to negotiate with of one the relatives for the Duccio’s loan (later rescinded) to the 2003 exhibition in Siena. Fahy may possibly have been the first scholar to see the painting in over fifty years. Tomkins reports Fahy saying that the picture “still hung then where it had always had, in Adolphe Stoclet’s private studio”. Christiansen later reported (Apollo 2007) that “Stoclet did not hang his gold ground pictures in this modern [Josef Hoffmann-designed house] setting but kept them in a large cupboard, taking them out, one by one, on Sunday afternoons or on the occasion of a visit of a guest such as Berenson.” Kenneth Clark had been the source of the cupboard storage claim. Fahy noted, “Everything the Stoclets collected was something you could put in your hand, small and precious”. Small, but not always precious. As Frances Vieta established (and Beck acknowledged in his 2006 connoisseurship book), Stoclet had owned two little Duccios, one of which proved to be a modern forgery in 1989. It, too, had been attributed to Duccio by Berenson’s protégé, Frederick Mason Perkins, who, along with Berenson’s wife, Mary Logan, had also upgraded the Met Duccio Madonna and Child, and two hugely expensive sculptures bought by Helen Frick that were also subsequently exposed as modern forgeries. Berenson himself had been taken in by half a dozen or so modern forgeries. The Cleveland Museum had been taken, too, but recovered when it identified modern wire nails and paints in a “Sano di Pietro” and declared it a fake. Before the Met picture had been first upgraded to Duccio by its owner, some had thought it a Sano di Pietro. The Cleveland Museum downgraded another Sano di Pietro to a school work when it – like the Met picture – was found to contain azurite not ultramarine. “With attributions”, Fahy held, “it’s not the number of people who agree with you, it’s the quality of their judgments.” The Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi had, reportedly, been unsuccessfully offered to Christie’s in 2005.

The Met picture, having narrowly missed a public viewing in the 2003 Siena exhibition for Duccio and his followers, suffered further non-visibility when Christie’s put the newly-emerged work into a private sale among just three major museums: the dollar-rich Getty Museum, which had balked at the asking price; the Louvre, which was said to be working on getting the money for the (then and still not-disclosed) asking price; and the Metropolitan Museum. Under this private sale arrangement it is possible that barely more than a dozen experts had seen the painting before it was sold to the Met and thereafter was trumpeted as an unquestionably autograph seminal and revolutionary work in the history of Western painting – and all this, as mentioned, ahead of a technical examination. The avoidance of public scrutiny during the sale seems to have occurred by design, not accident. Calvin Tomkins, whose New Yorker disclosures have not, so far as we know, been challenged, added:

“Although the ‘Madonna and Child’ was well-known in art-historical circles as the only one of Duccio’s dozen or so surviving paintings to remain in private hands, its whereabouts had been uncertain since the death, in 1949, of its last registered owner, the Belgian collector Adolphe Stoclet. In fact the picture never left the Stoclet House in Brussels. Stoclet and his wife… had willed the house to their son, Jacques, whose widow held onto it until her death in 2001. Soon after that, her heirs, (four daughters) who are very high on anonymity, agreed to lend it to an important exhibition in Siena, Duccio and his school…a few weeks before the opening in 2003, the painting was withdrawn. This coincided with rumours of an impending sale, which turned out to be true.

“Although everyone involved in the transaction is bound by omertà, it is known that both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the principal auction houses, engaged in lengthy and fiercely competitive negotiations with the heirs, and Christie’s eventually won the prize. ‘The family was very keen that the painting go to a public museum or institution,’ according to Nicholas Hall, international director of Christie’s Old Masters department. This was one reason that the family decided upon a private ‘treaty’ sale, in which the auction house and the seller determine the price and then offer the work to selected potential buyers, rather than letting it take its chances at public auction; another reason was that a private sale is more private. ‘We got it by putting a significantly higher valuation on the painting than anyone else – by multiples – based on its being the last Duccio in private hands and its being so impeccably preserved,’ Hall told me. Hall himself never met the sellers. ‘The contract document must have been four inches thick, and it was the most rigidly controlled transaction I’ve ever been involved in,’ he said…”

CHRISTIE’S LAVISH PRESENTATION LITERATURE

Tomkins reported that, in addition to the transparency, Nicholas Hall had given Christiansen the “lavish presentation booklet that Christie’s had prepared for prospective buyers”. On whose imprimatur or on what scholarly authority had that booklet been prepared? How many people got to see it? When Christie’s auctioned the Salvator Mundi, the publicly-disseminated provenance was frankly acknowledged to have derived from the National Gallery’s 2011 catalogue entry; the restorer’s 2012 report; and, through their declared joint indebtedness, to the (still today) unpublished researches of one of the original 2005-2012 consortium of dealer/owners.

A COURTIER FLATTERS?

When Christiansen left his lunch with his old friend at Christies, he wondered what to do next about the tiny work he considered “probably the most important early Italian picture that could ever come on the market”. Should he call his director who was on vacation in Canada? He decided to wait: “and then I went into his office and said, ‘I am duty bound to show you this,’ and then I showed him the transparency. I casually said to him, ‘You know, Philippe, you deserve this picture. Tom Hoving had his [1970 $5.5 million Velazquez] Juan de Pareja, Rorimer had his Rembrandt [“Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer” for $2.3 million in 1961]; I don’t see why you shouldn’t have this towards the end of your career’.”

Christiansen continued (to Danziger): “My director fortunately is a person who loves old master paintings, who grew up with old master paintings and worked as a curator in this department and does not need to be told much. He was completely riveted by it. He asked me the price while he kept looking at it, and then he said, ‘I don’t see how we can get it…’ But that, I imagine, was also when the wheels began to turn in his head, because when I left, I thought there was a real possibility.” In the heady post-acquisition days of November 2004 Christiansen recalled to Carol Vogel in the New York Times that when the director was first shown the photograph “it took him about 30 seconds to say ‘We really have to have this’”.

At the same time, Tomkins had made clear why de Montebello might have gagged on the price. The Getty Museum (which has been bitten by fakes) had already turned it down: “reportedly, because of the price. This struck Christiansen as ironic because the price was so clearly predicated on the fifty-five million dollars that the Getty had agreed to pay, two years earlier, for Raphael’s small, perfectly preserved Madonna of the Pinks.” That little Raphael in the mint of condition had, like the even littler Met Duccio, lost its original back when, for some reason it was polished by its artist/restorer/dealer/smuggler owners. When the cradle was removed from the back of the by-then Met Duccio, it was found to have been scraped down to the bare wood, on which was written an ascription to…a member of Duccio’s school. Like the Salvator Mundi, the little Raphael was one of many versions of the subject – there are over fifty-five Madonna of the Pinks. James Beck remarked in his 2006 connoisseurship book: “I find it appropriate to claim, given the situation as has already been sketched, there is no chance whatever that the Northumberland painting is an original Raphael.” But for sure, within a couple of weeks of seeing the photograph, de Montebello, Christiansen and the Met’s chief restorer, Dorothy Mahon, flew to London to see the Madonna and Child armed with a magnifier and a UVF lamp to spot retouches.

BUY FIRST LOOK AFTERWARDS

The next morning, after a couple of hours of inspection at Christie’s in London with Christiansen and Mahon, de Montebello made a quick and high offer (without Board authorisation). It was immediately accepted by Christie’s but under the terms of this “private treaty sale” the picture could not be removed from Christie’s to undergo examinations at the Met and be presented to the Board’s Acquisitions Committee for appraisal and possible approval, as was customary. This was because, as Christiansen put it, “the picture wasn’t leaving Christie’s until the whole deal was finished”. Why so – and why accepted by the Met when such a huge sum was at stake? Had this condition been stipulated by owners who seemingly had developed cold feet about the picture being seen for the first time in over half a century in the context of a show on Duccio and his followers?

In his 1993 memoir Making the Mummies Dance Thomas Hoving recalled that when he went to Christie’s in London in 1970 (with the then head of restoration, Hubert von Sonnenberg, Everett Fahy, and a Board member, Ted Rousseau), the chairman of the auction house, Sir Peter Chance – “the very symbol of upper-class culture neatly folded around commerce” – explained “The condition’s perfect…the picture will not be cleaned up for the sale. Lord Radnor forbids it. He is also against anyone…examining it…scientifically. But no matter, we all matriculated into connoisseurs without all these fashionable instruments, if I may say so, Dr. von Sonnenberg.” (Hoving was bemused when Sir Peter put the price at “approaching the two million guinea mark” – a guinea being a pound, plus a shilling: “While Sotheby’s always conducted their sales in pounds, Christie’s favoured the more pretentious guinea.” In those days the joke was that at Christie’s gentlemen pretended to be salesmen while at Sotheby’s salesmen pretended to be gentlemen. In today’s globalised ownership-fluxing art world it might prove impossible to slide a cigarette paper between them.)

That Velazquez painting truly was one of the greatest portraits ever to come to market – and, in some part it was so because it had probably not been touched in a century and a half. When the Met staffers revisited the next day, von Sonnenberg held the picture against the window when the guard left the room and discovered that it had never been lined – hence the extraordinary vigour and sparkle of the brush work. As soon as Hoving and von Sonnenberg took possession it was sent secretly to Wildenstein’s – not to the Met itself – and there it went straight under the conservation chemical cosh on a claim of dirty varnish-removal but, in reality, in conformity with the museum’s imperious proprietary and aesthetic imperatives. (See “Discovered Predictions: Secrecy and Unaccountability at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York” and “Why is the Metropolitan Museum of Art afraid of public disclosures on its picture restorers’ cleaning materials?”) Even before it might become “The Metropolitan Velazquez” the portrait became a Met-treated painting and no one else at the museum, let alone its paying public, ever got to see the great masterpiece in its unadulterated state. To his credit Rorimer had earlier confessed (privately) to Alexander Eliot that the Met’s restorers had ruined its Rembrandts – and those poor paintings were not alone:

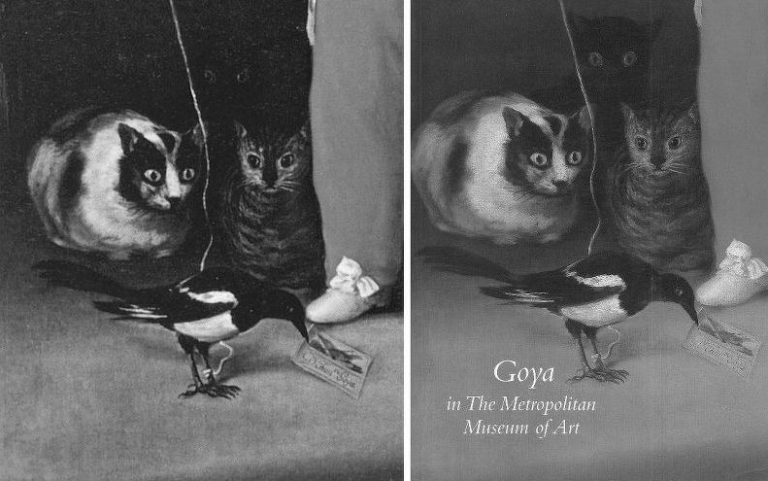

Above, Figs. 9 and 10: Details of the Met’s Goya portrait of the young Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga who died before he was eight years old. As seen before cleaning (left) and after cleaning (right).

In July 2005 Philippe de Montebello explained to Calvin Tomkins (New Yorker): “It’s the single most important purchase during my twenty-eight years as director – It’s my ‘Juan de Pareja’, it’s my ‘Aristotle.’” De Montebello later explained in the Summer 2008 Met Bulletin that he had moved so fast on an unexamined work because he felt authorised by:

“the assurance that comes from the trust I have learned to place in the curators and conservators of this great institution…As I held the picture in my hands, enraptured by its wonderful quality…I was treated all the while to Keith’s impassioned scholarship…it was particularly Keith’s precise and learned assessment of the picture that allowed me to consider the acquisition an imperative.”

(For a fuller account of de Montebello’s decision to buy, see CODA below.)

Immediately after spending nearly $50million on the unexamined Duccio at Christie’s in London, Christiansen, de Montebello and Mahon went to see the National Gallery’s Duccio triptych The Virgin and Child with Saints. Christiansen recalled (as reported in Danziger, 2007): “After about two hours at Christie’s we all walked down to the National Gallery where they have a very rare and beautiful Duccio triptych, which is simply marvellous – a touchstone of Duccio’s work – and we all felt that ‘ours’ was every bit as fine and in certain respects, more intimate and direct.” The following year, in a foreword to the 2008 Summer Met. Bulletin Christiansen elaborated:

“…we decided to walk the few blocks to the National Gallery, which owns a portable triptych by Duccio that has long been a cornerstone of its superb collection of early Italian paintings. The triptych is a work of extraordinary beauty and impeccable craftsmanship. Duccio struck a slightly different key than in the picture we had been examining, placing greater emphasis on the regal bearing of the Virgin. The motif of the Child playing with his mother’s veil is further developed, so that Christ unfurls a rich cascade of folds. But these enhancements came at the expense of the simple dignity and touching humanity of the small panel we had seen at Christie’s. In short, we felt that we had before us the opportunity of acquiring a painting that was on a par with one of Duccio’s most admired and best-preserved works, a painting that represented the artist at the very height of his powers.”

Michael Daley, Director, 6 February 2019

In Part II we consider why the Met team might have been advised to view the National Gallery Duccio triptych (and its dossiers) before visiting Christie’s and buying on the spot.

CODA:

Martin Gayford accompanied Philippe de Montebello on a walk around the Metropolitan Museum, as recorded in his 2014 book RENDEZ-VOUS WITH ART. In his chapter “The Case of the Duccio Madonna”, Gayford wrote: “We ended up sitting on a bench near perhaps Philippe’s most celebrated acquisition: a small exquisite Madonna and Child by the 14th century Sienese master, Duccio. It remains the most expensive single object ever purchased by the museum. So how, I asked, did he make the momentous decision to buy it?” De Montebello replied:

“When the Duccio was on offer, I had, as Director, to decide whether the picture was worth the huge sum I would have to raise to acquire it. To arrive at this decision, I had to wear several hats all at once: one of these was that of an informed art lover, the French ‘amateur’, and in that role focus on the seductive and lyrical lines, the harmony of the colours, the felicitous choreography of the hands and feet, the wonder of the human contact coincident with a certain respectful detachment in the depiction of figures, that are, after all divine. I also had to don my art historian’s hat and note that this Duccio was one of the very first pictures that mark the transition from medieval to Renaissance image making. It represented a key moment, a break from hieratic Byzantine models to a more gentle humanity.

“To be more specific, and it is more than just a recondite detail, look at how the parapet at the bottom connects the fictive, sacred world of the painting with temporal one of the viewer. This important observation – among others – was made by the curator Keith Christiansen as we were examining the picture in London. This led him to conclude that Duccio must have seen the Giotto frescoes in Assisi depicting the life of St. Fancis, where the illusionistic framework, including the parapet, relates the narrative scenes to the architecture of the church.

But Martin, you want to know the truth? All those considerations were largely irrelevant when the time came to decide whether to spend in the region of $45 million on the work. For this, I needed my museum director’s hat. The quantitative assessment had to be based on different criteria. First and foremost were the old-fashioned notions of quality, craft and skill. Did the work sing? Did it stop me in my tracks and did it then hold my attention? Was I reluctant to turn away from it too quickly?

“However, in my mind, the question of relative importance and quality was always pushing itself forward. That the work was beautiful and admirably well painted was not enough. It needed also to be very important, exceptional in every way, and extremely rare. If there had been three or four others similar to this one it would have meant that this picture should command a lower price.

“Then there was the question of what the price of this panel should be in comparison with one of the missing predella panels from Duccio’s Maestà in Siena were it to come up for sale. This is because the Madonna was and is a self-contained, independent and devotional image; it doesn’t belong to a larger work, the wholeness of it is part of its beauty and impact. The entire story is there in that one painting. That, too, added to its value.

“Then, as curators, we also needed to be concerned with the physicality of the work. After all, this object, which can be held in the hand, has weight and a certain thickness, and is vulnerable to the vagaries of time. Part of what drove me to buy the Duccio was the fact that for close to an hour I did hold it in my hands, that I did turn it around, looking at the back, sensing its weight, measuring its thickness. It had a corporeal reality that was almost, to use a paradox, mystical.

“No longer bound by image alone, as one would be when looking at a photograph – or even from a distance – I then focussed on the deep burn marks at the bottom of the frame, obviously made by votive candles, confirming that this was indeed a devotional picture. Just a few additional details resulted from close examination, not the least of which was that the picture was in impeccable condition, a rare thing when it comes to Trecento gold ground pictures, as most works have suffered greatly over time, mostly I’m afraid at the hands of restorers.

If you are a student of art, just think of the Jarves collection at Yale, where many of the pictures, early renaissance works, are now a near total ruin. We were also able to confirm that this was indeed not an incomplete work, a wing of a Diptych for example, there is a hole at the top indicating that the picture was hung from a hook.

“Then, of course, came the issues of the provenance or ownership history, an important preoccupation of art historians, for what it may reveal about the work. While it obviously began life as a devotional picture, made for an unknown patron, it eventually ended up in the hands of two major European collectors: Count Grigory Stroganoff at the end of the 19th century, and later the Belgian financier Adolphe Stoclet, in his Brussels house, which is a masterpiece of the Wiener Werkstätte. Also, the Duccio had been lent to the great Sienese exhibition of 1904 where it was highly praised; indeed one art historian Mary Logan (Bernard Berenson’s wife), deemed it the single finest work in the exhibition.

In addition, and not a minor factor in gauging the price, was the knowledge that there would most probably never be another Duccio for sale, as this was the only work of his known to exist outside of a museum. I also knew – which is why I made a quick and high offer – that the Louvre, the other major museum that did not have a Duccio, was after it as well and was going to make a real effort to buy it.

“So some competitive nerve was struck, and thus the need for pre-emptive action. While it may not have been conscious, I think that there is no question that a part of me wanted my institution to own that Duccio – over and above its importance to the proper representation of the development of Sienese art in the Trecento – simply to have it as yet another major work that would confirm the stature of the Met.

“At this point, the sum of all the above, which occurred in a rush of sensory and intellectual responses, led to an important psychological factor, which should not be underestimated in such cases: it is that of the curator/acquisitor experiencing what is a quasi-libidinal charge (you might even call it lust, albeit of a high order); the irrepressible need to win; to have taken the object of desire. You can’t get away from that. We are all human beings. Institutions are not just made of stone, glass and steel, they are run by people. It is absurd to try to maintain and project total objectivity.

“As a result of all these considerations, these thoughts, observations, calculations and feelings, as well as the confidence I gained from learned colleagues, the Met boasts this masterpiece of Trecento painting, while the Louvre, with its outstanding collection of Italian paintings, is still, and may forever be, lacking a Duccio. This actually saddens me, and I hope that a fine Duccio does turn up someday, from somewhere, and they can get it.”