The non-appearing, disappeared, $450million, now officially not-Leonardo, Salvator Mundi

Where history is generally held to be the handiwork of victors, in the art world, losers are often quickest off the block to re-write official narratives. No sooner had the catastrophic restoration losses on the Sistine Chapel ceiling become apparent than Vatican Museum officials declared that art history would have to be re-written in light of their chemically-excavated discoveries. The art historical establishment that had underwritten the restoration’s untested technical radicalism obligingly rewrote Michelangelo (as a long-unsuspected brilliant colourist) in a score of learned articles. In Italy today that exercise might seem to have succeeded: every Italian school child now learns of the “Glorious Restoration”.

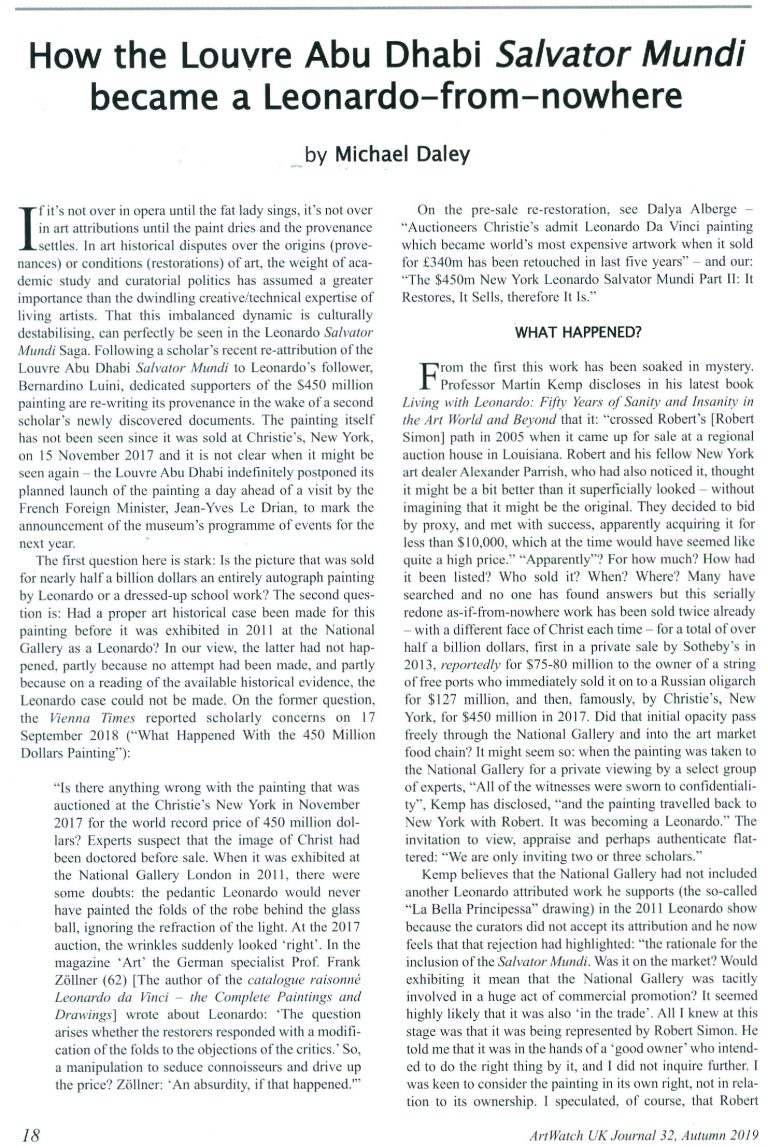

Rachel Spence, the Financial Times’ reviewer of the newly opened Louvre “not-a-blockbuster” blockbuster “Léonard de Vinci” exhibition, advised (26/27 October 2019): “Forget all the brouhaha around the ‘Salvator Mundi’ (it’s not here and shows no sign of arriving)…” How sweet that invitation not-to-address must have sounded to the Louvre authorities who had asked the day after the November 2017 sale at Christie’s, New York, to borrow the by then greatly-transformed work for their long-planned 2019 Leonardo anniversary extravaganza. That request was accompanied by one from the Royal Academy craving to include the work in their great Charles I Collection blockbuster exhibition. The 2017 sale’s outcome was taken by many of the Salvator Mundi’s advocates as an absolute validation of its post-2011 upgraded ascription.

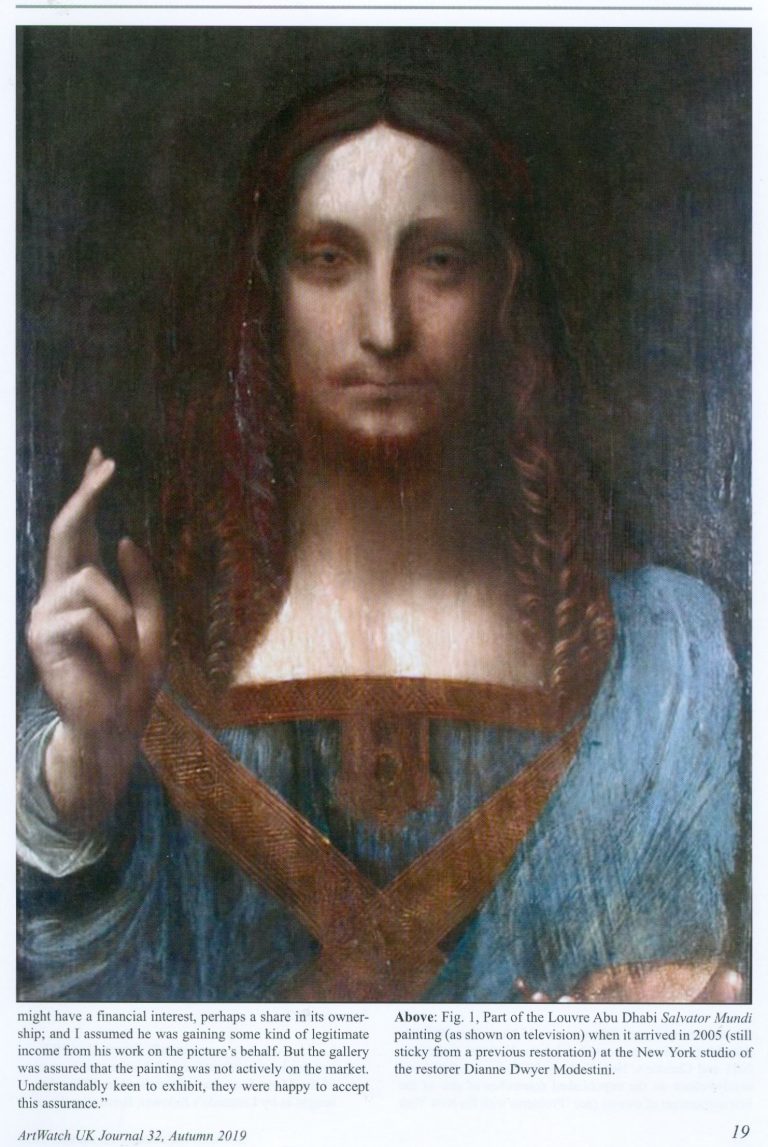

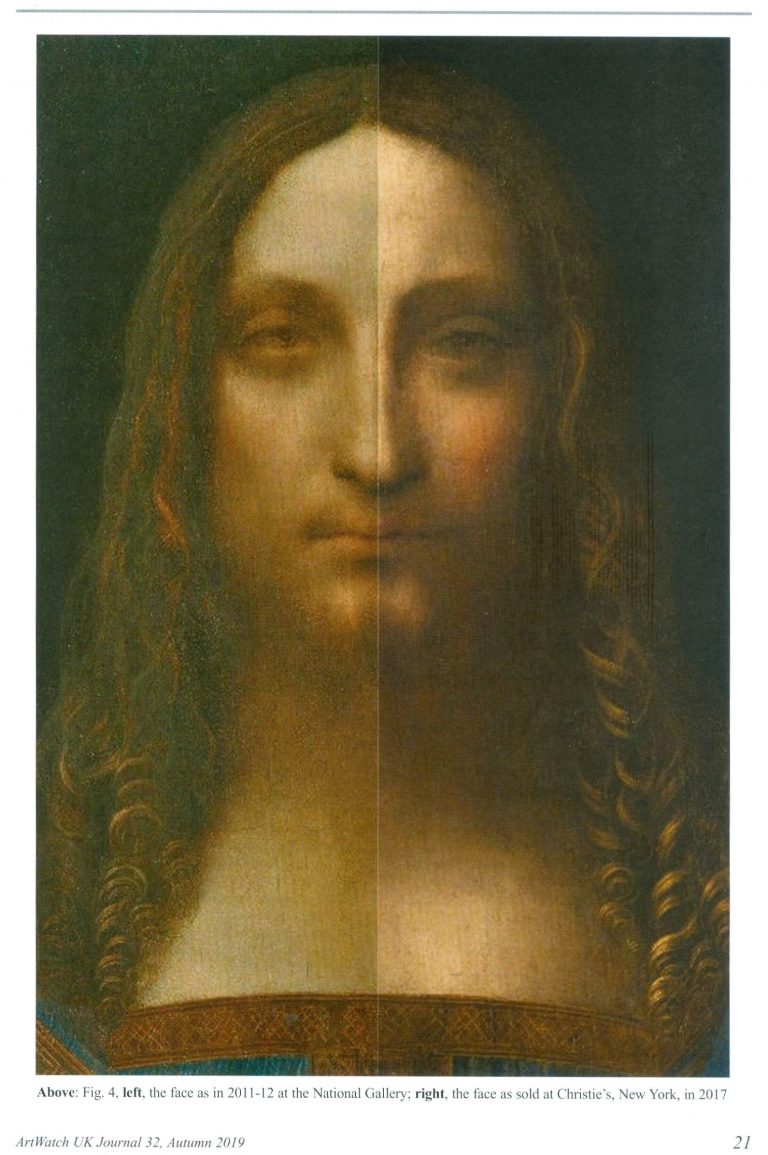

Christie’s “unusually broad consensus” of scholarly support included Vincent Delieuvin, the co-author of the present Louvre “Léonard de Vinci” exhibition. In the 2016 catalogue to the exhibition “Leonardo in Francia – Léonard en France, 1516-2016” (Figs. 2 and 3 above), held at the Italian Embassy in Paris in September/November 2016, Delieuvin wrote, p. 286: “The composition [of Salai’s Christ in the Ambrosiana, Milan] is strikingly close to Salvator Mundi, whose autograph version seems retrieved now, unfortunately in very bad condition”. Thus, in their fig. 1 reference to the restored Cook version (shown at our Fig. 1, above right, in both its 2011-12 state at the National Gallery and its 2017 Christie’s sale state) the Louvre presented the picture as the supposedly “long-lost” autograph prototype painting for the many other Salvator Mundi versions – just as it had been claimed to be by the National Gallery, in the catalogue entry for its 2011-12 Leonardo blockbuster “Leonardo da Vinci – Painter at the Court of Milan”.

In the catalogue of the present Louvre Museum Leonardo exhibition, the (absent) Salvator Mundi is no longer attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. Instead, it is simply listed as: “Fig. 103 bis, Salvator Mundi, the Cook version, c. 1505-1515”. It is reproduced in colour (p, 305) but with no catalogue entry. A chapter (pp. 302-313) by Delieuvin is devoted to a Salvator Mundi composition that has traditionally been attributed to Leonardo, though unsupported by any contemporary archival document. In other words, the New York/Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi has reverted to being one anonymous Leonardesque painting among many “with no decisive arguments which could have let a consensus emerge [regarding the attribution to Leonardo] from the concerned specialists”. Christie’s once-vaunted “unusually broad consensus” is now no consensus at all!

Some today hold that the “brouhaha” was triggered not by the substantial and various opposition to the picture’s upgrading but by the startling auction price it achieved in 2017 ($450million). At the time of the sale, many held that the attributed picture’s astronomical sale price had crushed the work’s critics and few more so than the sometime old masters art dealer and auctioneer, Bendor Grosvenor, who gushed support for Christie’s decision to pull the Salvator Mundi away from the old masters’ sale so as to thwart the depressing effect of informed art trade “nay-sayers”:

“It’s 1 a m here in the UK and I’ve just witnessed the most extraordinary moment of auction drama at Christie’s New York (via Facebook live). Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi has sold for £400m hammer, or $450m with fees.

“The lot was first announced as ‘selling’ at $80m, which I presume represents the level of the guarantee. Bidding was then brisk to the high $100ms, before, to audible gasps in the room, the picture broke through the $200m mark. Thereafter it was a battle between two phone bidders. The winning bidder kept making unilateral bids way above the usual bidding increments. Their final gambit was to announce, with the bidding at $370m, that their next bid was $400m. This finally knocked the competition out, and – after 19 minutes – the hammer came down. Whoever it was evidently has some serious cash to burn.

“And so an Old Master painting has become the most expensive artwork ever sold. It will have completely overshadowed everything else in the sale. The next lot, a Basquiat (usually a high point for contemporary sales) bought in as the room buzzed with Leonardo chatter. Will the sale prompt people to now look anew at Old Masters? Maybe. It will surely end for good now the tired cliché that the Old Master market is dead.

“Some immediate thoughts. First, the guarantor has made a few quid, and deserves it – guaranteeing that picture at this stage in its history (post rediscovery, and in the midst of an ugly legal battle between the vendor and his agent) was quite a risk. Second, the vendor – Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev – has made about $180m. He’s in the midst of a legal battle with the person he bought the picture from, an art agent called Yves Bouvier, alleging that he was over-charged (it has been reported that Bouvier bought it from Sotheby’s for about $80m, and sold it to Rybolovlev for about $125m – allegedly). I’m not sure how that over-charging allegation plays out now.

“Third, Christie’s just did something that re-writes the history of auctioneering. They took a big gamble with their brand, their strategy to sell the picture, and not to mention the reputations of their leadership team, and they pulled it off. They marketed the picture brilliantly – the best piece of art marketing I’ve ever seen. Above all, they had absolute faith in the picture. AHN [Grosvenor’s Art History News website] congratulates them all.

“Finally, despite the fact that this picture enjoyed near universal endorsement from Leonardo scholars, and had a weight of other technical and historical evidence behind it, there was a tendency in many quarters to be sniffy about it. I found this puzzling – not just because (for what it’s worth) I believed in the picture myself – since the determination amongst some to criticise the picture was in inverse proportion to their art historical expertise. It sometimes seems that the more famous the artist, the more people assume they are an expert in them. And with Leonardo being the most famous of them all, the armchair connoisseurs have been having a field day these last few weeks.

“Anyway, I’m going to bed. What a ride. I was sure the picture would sell, but never imagined it would make this much. We must all now wonder where the picture is going to end up next.”

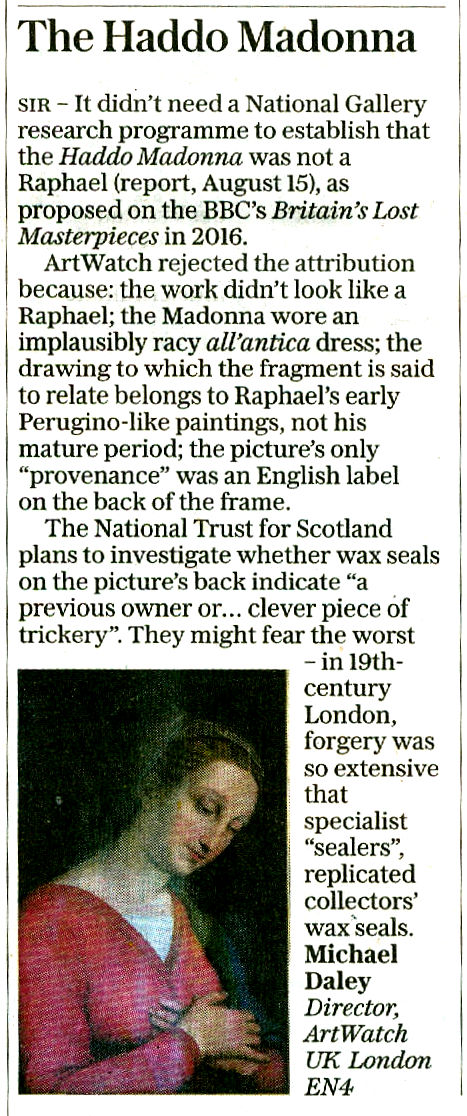

Two years later, when we, the Louvre, and everyone else, were still wondering where the picture might be, Grosvenor, in or out of his arm chair, suffered a reverse when his earlier television-launched Great Raphael Discovery bit the dust after professional examination at the National Gallery – as we observed in the 19 August 2019 Daily Telegraph:

In 2018 Professor Martin Kemp, a key member of the Scholarly Consensus was cooler on Christie’s choice of sale in his memoir Living with Leonardo:

“It was, however, a great surprise to find that the Salvator was to be sold Christie’s in New York on 15 November 2017 in a mega-auction of celebrity works of art from the modern era. [Some saw that as being apt in view of the picture’s extensive repainting.] The auctioneers sent the painting on a glamorous marketing tour of Hong Kong, San Francisco and London. I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.

“The price inched upwards from less than $100 million to $450 million, shattering the world record for a work of art. The result was cheered to the rafters. I was besieged by media requests for comment. Three weeks later reports that it had been purchased by one of two Saudi princes began to circulate, prompting Christie’s to announce that it had been acquired by Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the remarkable new ‘world museum’, where it will join Leonardo’s La belle Ferronnière. A public home at last, I hope.”

The brouhaha should not be brushed aside. Too many urgent issues have arisen concerning, for example, the singular debate and scrutiny-avoiding means by which the supposedly solid consensus was assembled (- and, on this, see Ben Lewis’s The Last Leonardo), and the top-secret restoration work that was carried out at the Conservation Center of New York University’s prestigious Institute of Fine Arts, during which covert operation the drapery at the (true) left shoulder of Christ was transformed and simplified (Figs. 1 above and 7 below) immediately ahead of the pre-sale world marketing tour – as revealed in “Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo da Vinci painting which became the world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for $340m has been retouched in the last five years”. While in truth we still don’t know the whole story or even the post-sale whereabouts of the picture, much of the recent ground is covered in the ArtWatch UK members’ Journal No 32, as sampled in Figs. 5-8 below. [AWUK Journals are distributed free to members. New members receive the previous two issues – presently as shown at Fig. 1 above. For membership application details please write to Membership at: artwatch.uk@gmail.com ]

Michael Daley, Director, 28 October 2019