IN THEIR OWN WORDS: No. 3 [11 March 2018] – The Reception of the First Version of the Leonardo Salvator Mundi

Mounting concerns over transparency in art world deals are throwing back-dated light on the Salvator Mundi’s reception in its first-restored incarnation when included in the 2011 National Gallery exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S FIRST PUBLIC OUTING IN 2011

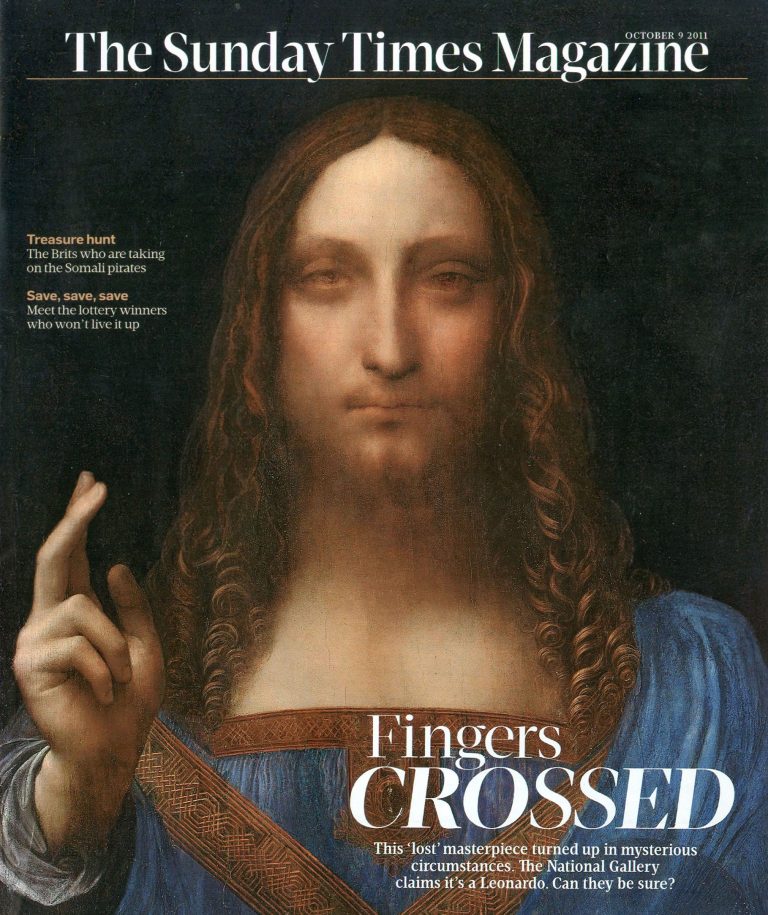

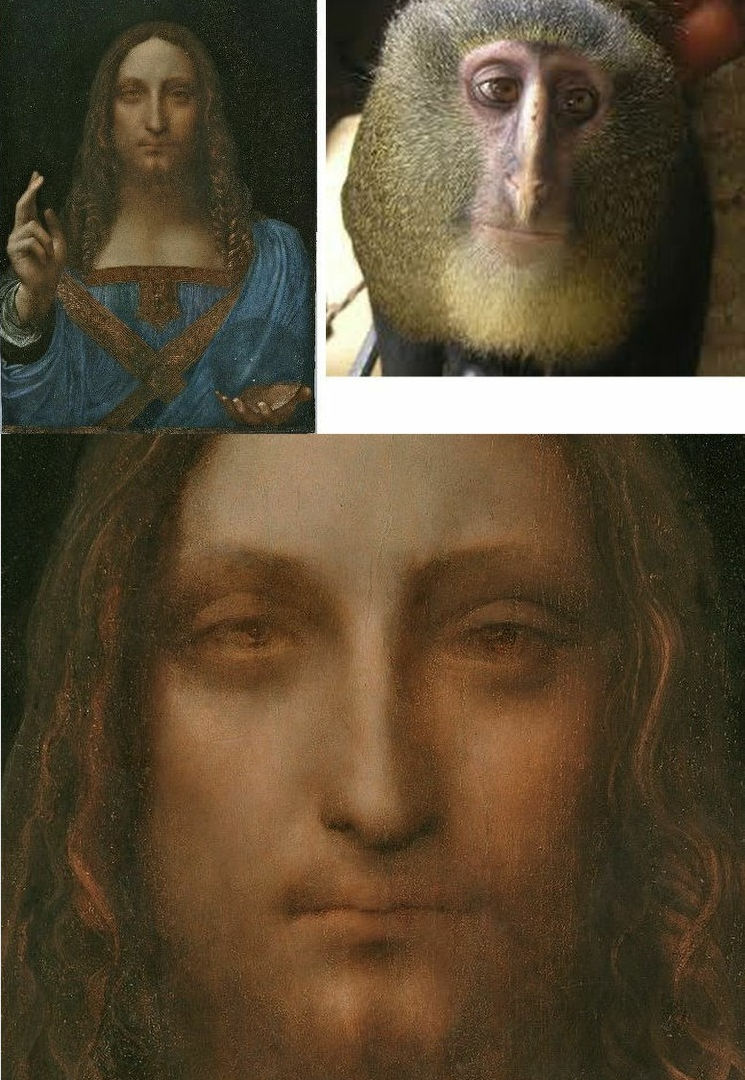

Above, top, the Sunday Times magazine cover of 9 October 2011. Above, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen after repainting in 2011, left; above, right, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen in November 2017 after further repainting between 2012 and 2017.

In the 9 October 2011 Sunday Times (“LEONARDO? CONVINCE ME”), Kathy Brewis wrote:

“For a few weeks in London you will be able to see the Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World) up close. It might be your only chance. Much of the painting’s history remains obscure. Its ownership is a closely guarded secret. Robert Simon, a New York art dealer, is representing the owner or owners – the official line is it is a ‘consortium’. Why all the secrecy? ‘It’s just privacy and security’, says Simon, ‘One doesn’t want people knocking on the door.’

“…He showed it to Mina Gregori, a retired professor at Florence University, who was stunned: ‘I believe it’s by Leonardo.’ Then he showed it to Nick Penny, who had just been appointed director of the National Gallery. ‘He understood it in a nanosecond. He said that one of his ambitions was for the gallery to be a venue for scholarly inquiry and research and that he’d like the painting to be brought to London so it could be compared with the Virgin of the Rocks.’ It was Penny who told him [Simon]: ‘You need a consensus…’

“Since Robert Simon went public with the discovery, he has received many emails from Leonardo fanatics. ‘There’s the serious obsession and there’s the lunatic one – people for whom Leonardo is a source of fantasy. The paintings are not knowable,’ he muses. ‘Every one of them presents a problem and a challenge.’ Even at this stage? ‘Art historians are a prickly, competitive lot. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone stuck their hand up and said “I don’t believe it”’. Could the experts be wrong? ‘They could be wrong about anything. But as much as I believe anything in this world, I believe this is by Leonardo.’”

Above, and top left, the Salvator Mundi as exhibited in 2011 at the National Gallery’s big Leonardo exhibition.

Kathy Brewis continued:

“…Frank Zöllner of Leipzig University [- and author of the Leonardo catalogue raisonné] is a rare dissenter: he thinks the proportions of the nose (‘too long’ for such a perfectionist as Leonardo) make it more likely to have been painted by a talented follower. The rest are convinced, if a little jealous that they didn’t unearth it themselves. ‘People in the art world get sniffy about dealers,’ says Bendor Grosvenor, director of the London fine-art dealership Philip Mould. ‘But if it wasn’t for the trade, discoveries like this wouldn’t be made. Specialist dealers are the ones who are prepared to buy a dirty picture, roll their sleeves up and get stuck in to seeing what it is.’

“Is it wise for the National Gallery to put it on show so soon after its authentication? ‘They are taking a risk,’ says Grosvenor, ‘and I can’t applaud them enough for it. Connoisseurship is a nebulous discipline. There can never be absolute 100% proof. You have to accept there’s an element of doubt and go with it.’”

Note – On 5 March 2018 Grosvenor declared himself an ex-dealer on his blog Art History News: “Now, portraiture can be a hard sell – I know this from having spent over a decade actually selling portraits, in my former life as a dealer.” This did not come as an absolute bolt out of the blue: although he remains a director of the Scottish auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull Limited, last year Grosvenor briefly closed down his website following certain professional criticisms, commenting as he did so: “at the same time AHN also makes me a significant number of, well, ‘enemies’ is not too strong a term. Every walk of life has its Salieris, but in the art market there are an awful lot of them.”

Kathy Brewis continued with a discussion on the Salvator Mundi’s owners:

“Luke Syson, the show’s curator is one of the few people who know who owns the picture. ‘We couldn’t exhibit it otherwise. It’s not being wafted to us in a brown envelope.’”

Ben Hoyle reported the Salvator Mundi’s owners’ plans in the Times of 12 November 2011 (“It’s kind of scary – I wrapped it in a bin liner and jumped into a taxi with it”):

“‘Everyone involved recognises the importance of it as a work of art. Doing the right thing has been very important and will continue to be,’ Mr Simon says. If that means selling it for half the price they could attract, to ensure that it stays on public view, then they would prefer to do that.”

In the event the picture was sold privately by Sotheby’s in 2013 to a Swiss businessman, Yves Bouvier, who is known as the “Freeport King” (and who, among many commercial interests, owns an art conservation and authentication service), for appreciably less than the sums of $150-200m being talked about in 2011 (when the owners reportedly had turned down a $100m offer). The original consortium and Robert Simon received $80m for the Salvator Mundi from Bouvier who resold it for $127.5m to the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev.

To this day we do not know who owned the Salvator Mundi before 2005 or between 2005 and 2013. From whomever and by whomever it was bought in 2005, the painting’s reception as an attributed Leonardo in 2011 was very far from uniformly rapturous. In addition to the dissenting scholars we cited on 14 November 2017 (see THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF THE NEW YORK SALVATOR MUNDI), a number of newspaper art critics were un-persuaded.

In the 13 November 2011 Sunday Telegraph (“The genius of Leonardo”), Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote:

“…The picture is certainly Leonardesque. But is it by Leonardo? That is the considerably-more-than-million-dollar question for the consortium of art dealers who acquired the work a few years ago for an undisclosed sum. If the attribution holds up they can expect to reap £125m as a reward for their good judgement.

“Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan is a breathtaking and truly remarkable exhibition which brings together around half of the surviving 15 or so surviving paintings by the famously dilatory artist of the Italian Renaissance…Two works in particular appear destined to come under scholarly fire.

“Although it gets the thumbs up from the National Gallery’s curator, [Luke] Syson, there will certainly be those who question the new Christ. The picture undeniably displays a number of the painter’s characteristic devices and mannerisms, but there are other aspects of it that seem foreign to Leonardo himself.

“He was prized by his contemporaries as one of the most innovative and forceful painters of emotion, yet the face of this Christ seems peculiarly inert. Taken individually, its elements are convincing enough, but viewed as a whole its expression seems to lack a certain subtle Leonardo magic: the spark of inner life and feeling…”

Even after the picture had been re-done-over by the restorer, Diane Modestini, ahead of the 15 November 2017 sale, the Sunday Times’ art critic, Waldemar Januszczak, responded with less tact than Graham-Dixon (“The Miracle of da Vinci: Turning a £45 Oddity into a £341m Old Master”, 19 November 2017):

“…To call the Salvator Mundi untypical is massively to understate the case. It resembles nothing else Leonardo painted

“The claim by Loic Gouzer, chairman of contemporary art at Christie’s in New York, that the record-breaking Jesus bears ‘a patent compositional likeness’ to the Mona Lisa had me laughing out loud. Yes, it shows the upper half of a figure in a frame. But that is the only compositional likeness the Salvator Mundi shares with the Mona Lisa…

“The next time I saw the painting was in 2011 when the big Leonardo exhibition was opened in London. Full of magnificent loans – the Lady With an Ermine, from Poland; the Virgin of the Rocks from the Louvre – it really was a once-in-a-lifetime event. And there on the wall was the recently rediscovered Salvator Mundi looking just as strange and sci-fi as I remembered it.

“At the time it was owned by a consortium of art dealers who had bought it in an American estate sale for $10,000 as a work by a follower of Leonardo. The dealers had it comprehensively cleaned and repainted. The National Gallery, eager to give its show a boost, announced it as the first new Leonardo discovered in 100 years. Wow…

“Soon after its London unveiling it was sold on to the Russian Billionaire, Dmitry Rybolovlev, for a reputed £98m. It was Rybolovlev who sold it again in New York last week.

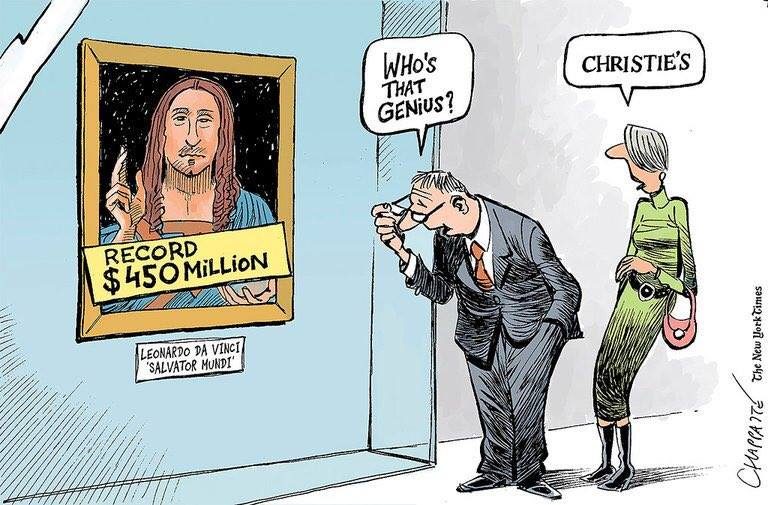

“How did Leonardo’s sci-fi Christ, who looks as if he belongs on the cover on one of L Ron Hubbard’s scientology textbooks, end up costing all those shekels? It was mostly due to the wicked brilliance of Christie’s.

“Not only did the auction house tour the picture noisily to Hong Kong, and London before the New York sale, drumming up interest among the newly rich, but its hype department was also in full swing on this one. Finding a new Leonardo, boomed Gouzer, ‘is rarer than finding a new planet’. It’s ‘the greatest discovery of the century’ repeated the Christie’s chorus.

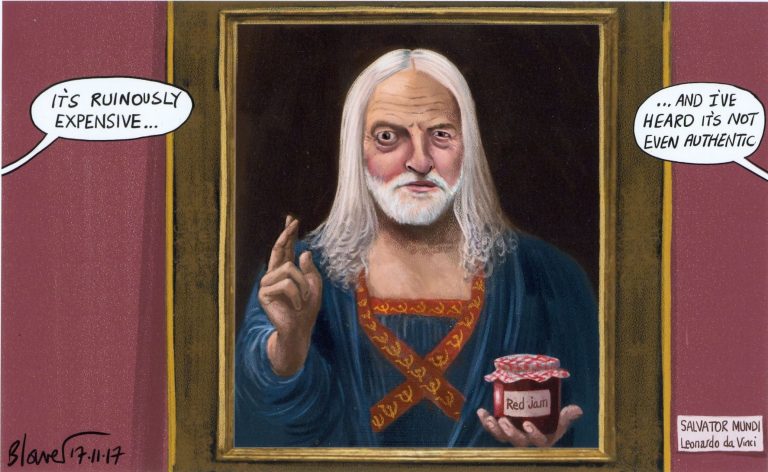

Above, Patrick Chappatte’s take on the Salvator Mundi sale/attribution for the New York Times. Below, Patrick Blower’s incorporation of the Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, for the Daily Telegraph:

Waldemar Januszczak continued:

“In recent years modern art has been where the money goes. A new generation of mega-rich collectors who know a lot about luxury brands but not much about art, have piled into the market and sent prices soaring.

“Earlier this year a quickly splattered Jean-Michel Basquiat of a face shaped like a skull sold in New York for an astonishing £85m. By putting the Leonardo in such a context, Christie’s circumnavigated the knowledgeable world of the Old Master collector and headed straight for the dumb f**** with the money.

“There are various ways to understand events in New York on Wednesday night [of 15 November 2017].

“You can see them as evidence of Leonardo’s treasured and mythic status in art. You can see them as testimony to the power of attribution. Or you can see them as proof that we live in a mad world that has lost sense of true value and in which obscenely rich people waste obscene amounts of money on the obscene acquisition of trophy art. Going, going, gone.”

SUPPORT AND DISSENT

It so happens that the scholar who first attributed the Salvator Mundi to Leonardo, Professor Mina Gregori, was also the first scholar to attribute the proposed Leonardo drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Professor Martin Kemp. However, “La Bella Principessa” was not included in the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition and, seven years later, it remains unsold. Although we know precisely why the dissenting scholars rejected the Salvator Mundi attribution (- they published their views in the scholarly press), we have virtually no information of who said what and in what order among the consensus of scholars listed by Christie’s (see Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation).

SECRET DEALS – AND THE ARTS CLUB

Since we began warning on this site in 2014 of the threat to market confidence posed by the art world’s toxic attributions and specifically called for increased transparency through a statutory requirement that vendors should disclose all that is known and recorded about the provenance and the restoration treatments of works of art (“As things stand, it can be safer to buy a second-hand car than an old master painting” – “Art crime”, ArtWatch UK letter, the Times, 13 August 2014), secret deals have come under increasingly intense investigation. In her 2017 book Dark Side of the Art Boom, Georgina Adam wrote:

“At its base, the Bouvier/Rybolovlev dispute was about the nature of their business conducted within a market that has always thrived on secret backroom deals. By keeping vendors and buyers apart – they may never know who the other is – and insisting on discretion, agents, dealers, advisors can use this anonymity to their advantage. Various reasons can be put forward, from the need for security to the desire to avoid family quarrels or the taxman, to the risk of someone else bagging the work for sale. In the Bouvier/Rybolovlev case, one of Bouvier’s emails about a Magritte, said: ‘I must carry out this [negotiation] with the greatest discretion to avoid drawing attention to the painting and its owner; the risk is that we could lose it at auction.”

In this weekend’s Financial Times (10/11 March 2018 – “Laundering Picasso: British dealer among accused in $50m case”), Melanie Gerlis cites the emergence of another highly embarrassing series of documents:

“Potential shenanigans involving art are in the spotlight once again. London art dealer Matthew Green is among defendants in the case against Beaufort Securities, three other corporations and five other individuals, accused by the US Department of Justice of a multiyear $50m-plus securities fraud and scheme to launder money, partly through the sale of a £6.7m painting by Picasso.

“The indictment alleges that Green, described as the owner of Mayfair Fine Art Limited, met last month with an investment manager from Beaufort Securities (now declared insolvent), as well as a property developer and an undercover federal agent masquerading as a client of the brokerage firm. At this meeting held around February 5, the court papers say that the agent-client was told he could ‘purchase a painting from Green using the proceeds of the stock manipulation deals and later sell the painting to “clean the money”’…The papers describe the art business as ‘the only market that is unregulated’”.

“The papers also say that Green – who had allegedly asked for a 5 per cent profit on the transaction, ‘so that he would not be asked why he was in the money laundering business’”. [Green] sent a message via What’sApp to the Beaufort Securities manager that read: ‘[O]bviously because of the nature of this transaction we need to preserve a certain amount of anonymity which [the undercover agent] and I discussed and clarified at the Arts Club!’”

UNDERCHARGING FOR CURRENT MARKET PRACTICES

The Art Market Monitor blogger, Marion Manneker, made this observation in his (5 March) comments on the trial:

“Green doesn’t seem to know that the price for laundering money is much higher than 5% which definitely isn’t worth the risk if it gets you indicted after being in business all of three months. Worse still, Green and his partners don’t seem to be the swiftest criminals. They boasted that the art market is unregulated but then created a scheme that seems to have had little to do with the art market itself.

“The art sale is only one of several money-laundering venues that the person was offered. Offshore banks and real estate deals figure prominently in the indictment. What’s more, Green’s scheme could have been conducted in just about any commercial transaction. And, since the payment for the Picasso was due March 6, 2018, we’ll never know if Green was actually capable of pulling off the sale at the price he claims or would have survived any kind of audit.”

OLD HABITS DIE HARD?

Manneker’s comments on the cut-price scale of Matthew Green’s alleged laundering service charges recalls certain comments of Kenneth Clark who recognized that his appointment as director of the National Gallery at a very tender age owed much to the fact, as he wrote in his 1977 memoir Another Part of the Wood, that:

“[T]he ideal candidate for the post was disqualified. This was a Finnish art-historian named Tancred Borenius. He was a good scholar, a pleasant companion and a passionate upholder of the concept of the monarchy. He would have made an ideal courtier. Unfortunately, he was known to have followed the continental practice, described above, of taking payments for certificates of authenticity; and what was worse, quite small payments (known as ‘smackers under the table’); if he had taken large payments like a few scholars on the continent, no one would have objected.”

Michael Daley, 11 March 2018

UPDATE, 12 March 2018. On 11 March, a Sunday Telegraph supplement (“Arts, Antiques and Collectibles”) carried a “Promotional feature” – “Managing Risk When Buying and Selling Art” – for the law firm Constantine / Cannon. In offering the firm’s services, the article began:

“TRADING IN ART has traditionally been done on a handshake, but this is changing. You would not buy or sell a house without relying on a lawyer to prepare the contract, would you? The same goes with art, and now buyers and sellers are increasingly turning to lawyers to help them manage the risks associated with expensive works. The art market used to function like a club of like-minded people, but that’s no longer the case. The market now is truly global, and it has become less transparent in the process…”