Why Greece Does Not Need the Elgin Marbles

An (unpublished) paper by Michael Daley, Director, ArtWatch UK, that was delivered at the Economist’s Athens Conference, 12 March 2003:

Lots of reasons have been put forward in support of the campaign to remove the so-called Elgin Marbles from the British Museum. Individually, these justifications rarely withstand scrutiny, but cumulatively, their repetition has left many in Britain with the impression that under all the smoke there must be both a fire and a wrong in need of righting.

I wish to suggest today that, to the contrary, there are good reasons for contending that the restitution campaign is itself wrongheaded, unjust and culturally dangerous.

The original removal of the sculptures from the Parthenon and the ground and the walls of the Acropolis by Lord Elgin has been presented as theft when the British Museum’s legal title is today accepted by all parties to the dispute. The removal has long been caricatured as vandalism and desecration when, demonstrably, it constituted an act of rescue and celebration. This fact, too, has now largely been accepted.

Faced with the legitimacy of the British Museum’s ownership, the would-be “restitutionists” have appealed above the rule of law to the forces of sentiment – and forces, often, of distinctly nationalistic sentiment. “These sculptures mean so much more to us than they ever could to you” it is said. And even more disconcertingly:

“Without these sculptures we are not complete as a nation, they comprise our very soul.”

It would be hard for anyone to resist such morally coercive appeals – and the British are constitutionally inclined to want to “do the right thing” but, as it happens, resistance is no longer necessary: Greek scholars have testified that although the Parthenon indeed was, for members of late 19th century Greek society, a sacred symbol of the nation, the rise in the 20th century of tourism and economic modernisation has “taken them out of their role as symbols and gradually turned them into social goods”.

Confirmation of this transition appeared with a recent announcement that Greece plans to replace low-spending tourists with high spending ones by “showcasing Greek cultural traditions”.

With the decline of appeals to nationalistic sentiments, the claims of an Urgent Aesthetic Imperative have been advanced. “It is a crime against art”, the argument goes, “not to allow the component parts of a glorious entity to be seen whole.”

The cult of the dismembered-whole-in-need-of-reintegration was launched in 1945 by Thomas Bodkin with his seminal book Dismembered Masterpieces – A plea for reconstruction by International Action. It certainly is sad when artistic ensembles are scattered by history but in the case of the Parthenon sculptures it is worth recalling Bodkin’s comments on them:

“It is abundantly clear that the statues from the pediments, the portions of the frieze and the metopes now in England should never be re-integrated on their original sites. Those few sculptures which Lord Elgin did not remove have in the intervening one hundred and forty-two years been allowed to deteriorate into utter wreckage, corroded by wind and rain and the fumes ascending from the factories of Piraeus”.

Bodkin of course did not know of the notorious Athenian pollution that would be in train from the 1960s. Greek scholars have testified to the devastating consequences for the Acropolis monuments of that further, later pollution.

In the view of many here and abroad, Greece’s own past neglect and mishandling of the Parthenon and its remaining sculptures constitutes one of the greatest 20th century art conservation tragedies. To those of us who are professionally dedicated to the survival and welfare of art, the vocal opposition of Greece’s own scholars and art lovers to today’s Government-led scramble for development is certainly heartening but it does also confirm that vital lessons have not yet been learnt. These developments compel the observation that a nation that is showing indifference to its own patrimony and is cavalier with even its most precious historical sites, does not need to take on more heritage responsibilities. To those who might feel such a judgement harsh, we cite a single plea. It came recently from the island of Paros.

“…We are therefore obliged to ask for the support of the international academic community, suggesting that our overseas friends mail letters of protest to the Greek Minister of Culture, underlining their concern about the deliberate destruction of monuments on Paros. How is it possible to demand the return of the Parthenon marbles, while allowing the ruthless destruction of other ancient temples by unqualified employees?”

In the face of this actual, ongoing destruction, British restitutionists and museum personnel have taken to fretting about a need for “context”. What context? Reuniting the Elgin sculptures with the decaying Parthenon building is now, as Bodkin could already see, impossible. The new sculptural ensemble being mooted for Athens is that of a wholly severed – and, in fact, distinctly out of context collection. That is, it would be indoors, not out. It would be off Acropolis, not on. Even if every museum presently holding Acropolis sculptures were to return their works, the new “entity” would still remain incomplete because of early losses.

More embarrassingly, if all the surviving sculptures were to be returned to Athens tomorrow, they could not be joined by Greece’s own west frieze sculptures, which were removed from the Parthenon ten years ago and still await a decision on possible conservation treatments to stabilise their pollution-damaged surfaces. Were this problem to be resolved, it would still be necessary, before any assembling of the survivors could take place, for the sculptures that presently remain united with the Parthenon, to be “dis-united” from it, as if in emulation of Lord Elgin’s long condemned original actions.

In truth, of course, the Parthenon sculptures can never be “shown in context” because their original context is so long gone. It might now be imagined but it can never be replicated. We do know, however, that the sculptures originally survived as symbolic adornments to a temple standing on a reinforced hill and not in a modernist museum, to be built on stilts, on an important archaeological site in an earthquake zone and in the teeth of opposition from national and international scholars. Far from there being plans to recreate the original on-Acropolis context, there are even plans to remove, what one leading restitutionist terms, “the litter of unclassified stones” from the Acropolis in order to make more footpaths for more tourists. This is a particularly alarming prospect if Professor Snodgrass’s claim that eighty per cent of the Parthenon building is believed to be still present, is correct. There is, however, something much more important at stake in this dispute than the preservation and the right displaying of historical artefacts.

As mentioned earlier, the present hectoring demand that sculptures be moved from one museum to another is unedifying and dangerous. For one thing it constitutes nothing less than a government-led assault on the very idea of the internationally comparative museum. Greece – of all countries – does not need to be party to such a regressive manoeuvre.

It jeopardises international scholarly cooperation. It gives encouragement to those members of the museum sector in Britain who seem only too eager to shed as much as possible of what they see as so much colonial loot. I do recognise that members of the Greek Government have shown themselves to be aware of some of these dangers and that they themselves insist that the Elgin Marbles are the only sculptures for which demands will pressed. But what politician was ever able to bind his successors? Who today could guarantee that the removal of the Elgin sculptures from the British Museum would not instantly and forever thereafter be taken as a precedent for copycat campaigns in Greece and elsewhere?

For this artist, what is most saddening about the present campaign is that by trading the universal for the local, it conspires against a proper recognition of the true nature and full extent of Greece’s patrimony. There is a lot of wonderful art in the world but the truth that is being lost in this squabble over particular material objects is that Greek classical art is like no other art – it has done what no other art has ever done: millennia after its birth, it has emerged from death and neglect to seize the imaginations and enlist the passions of other people in other places. Greek classicism has even vanquished, later, better-preserved classical offspring. It has done so not by conquest or politicking but solely on merit; by example; on the unrivalled authority of its inventions. It is unfashionable to say so, but these inventions stand uniquely transcendent and enduring, outside of time, original context and regardless of geography and ethnicity, as artistic paradigms and exemplars.

Even within the antique world, Plutarch had marvelled that the sculptures of Pericles’ time, far from dating, retained a time-defying freshness and newness – as masterpieces. In the 19th century Karl Marx was stymied by the sheer force of Greek Art – to which, as a scholar at the British Museum’s reading room, he was regularly exposed. Marx’s grand meta-system was to be elegance itself: the so-called cultural superstructures of societies stand on, and are determined by, their economic bases; by their technical means of production. The more advanced the means of production, the more advanced the cultural manifestations. Primitive, economically backward societies, he planned to demonstrate, produce primitive backward art. Classical Greek art, however, blew this premise. How could it be, Marx was forced to ask himself, that an ancient art should not only continue to afford us with pleasure but should persist beyond its own time as both a standard and an unobtainable goal? The best explanation he could offer was that Greek art remained eternally charming because it represents the “the historical childhood of humanity, where it had obtained its most beautiful development.” This condescension will not do.

Greek forms have gripped modern minds, in world superpowers like Britain and the United States, not by their charm but by their potency, and their living relevance. Colonialism exposed modern Europeans to the charms of very many competing aesthetic value systems, but the power of Greece’s artefacts has remained uniquely awesome and persuasive – wherever they have come to rest.

The Greek temple, for example, stands perennially iconic as motif. It remains unequalled for its combined lucidity of construction and elegance of articulation. Which is why, for example, it remains incorporated into the fabric of Britain’s premier motorcar, the Rolls Royce – and with a winged victory as mascot on its bonnet. The Greek temple – and not, say, the pagoda – is as deeply entrenched in the modern unconscious as any Jungian archetype. Simultaneously, it confers dignity and reassurance to banking and stands guardian to free speech and debate in our modern universities and seats of government. In London, next to the historic Tower of London, a temple provides home to the names of British merchant seamen who perished in the Atlantic and Mediterranean at the hands of German U-boats and bombers.

Given the chance, Greek sculpture is seen to stand supreme in all company, in whichever museum – the bigger the museum, the greater the victory. The grandly ambitious international museum is now coming under fire politically, but it has been both an expression of and an agent for the modern renaissance of Greek antiquity. It is barely half a century since an historian like Hans Tietze could describe the artistic individuality of great museums as themselves “spiritual entities, and not merely as fortuitous accumulations of art treasures.”

Under today’s rules of correct, multi-cultural, discourse, museums like the British Museum may no longer say that ancient Greek art stands as the world’s best, as the most attractive and most humanly affirmative. But nowhere is this trait more apparent than in Bloomsbury in London, in the British Museum. By Insisting on seeing international, multi-cultural museums as repositories of loot; by fetishising original architectural/social contexts and localities; and by fostering nationalistic sentiment, we risk losing sight of a fundamental artistic truth: the sheer stand-alone transcendent quality of Greek sculpture. Pericles was given to inviting his dinner guests to see the Parthenon sculptures as they were being carved. Everyone who passes through London today can dine for free at Pericles’ table in a splendid purpose-built neo-classical hall – and certainly not in a cellar or basement as British restitutionists too often allege. It would be a tragedy if these supreme ambassadors for the finest art of sculpture were to be wrenched out of the great world forum of cultural voices that the British Museum comprises and in which they excel. Greece truly does not need to be party to such a brutal, disruptive act. Greece thrives, looks her very best in such elevated and various company. She lives. She needs nothing. Her primacy is absolute and unassailable. Well should be left alone.

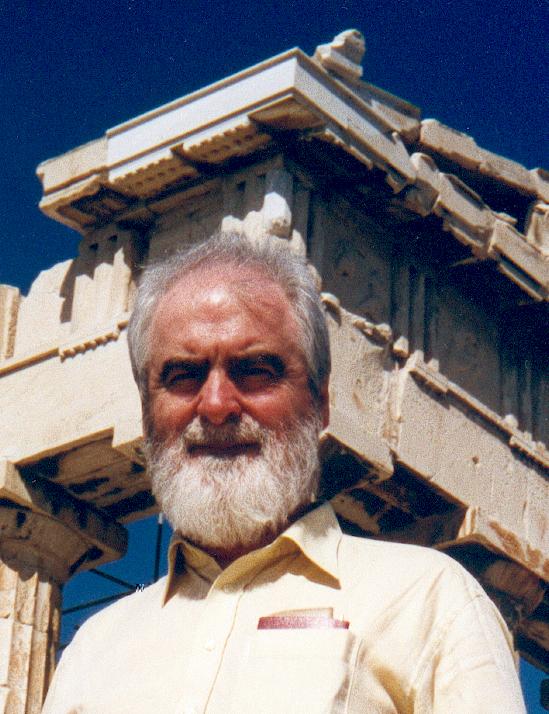

Above, Michael Daley, Director ArtWatch UK, at the Acropolis, Athens, 2003.

CODA

The Economist conference – and the campaigning contribution made by Lord (David) Owen – was reviewed in the Greek newspaper eKathimerini – as is today’s meeting of Prime Ministers Keir Starmer and Kyriakos Mitsotakis in London.

In August 1998 a correspondent in the Sunday Times’ books section wrote (under the heading “All Greek”):

“A more positive and generous list of the achievements of the ancient Greeks than Frederick Raphael’s more grudging one is given by the scholar F L Lucas: ‘Within seven centuries this race invented for itself epic, elergy, lyric, tragedy, comedy, opera, pastoral epigram, novel, democratic government, political and economic science, history, geography, philosophy, physics and biology; and made revolutionary advances in architecture, sculpture, painting, music, oratory, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, anatomy, engineering, law and war… a stupendous feat for a race… whose most brilliant state, Attica, was the size of Hertfordshire, with a free population (including children) of perhaps 160,000′!”

In February 2000 we wrote (in “Pheidias Albion”, Art Review):

And let no one believe that foreigners alone reject Greek demands or condemn Greek practices. A few years ago, The Times carried this plea from Mrs Magdala Delfas:

“When in 1967 I left Greece under the colonels’ rule, my visits to the British Museum brought me solace. I was able to keep in touch with my cultural heritage outside the geographical and political confines of Greece.

“Later, I discovered to my delight and amazement that apart from the perfect display of the Elgin Marbles in their special gallery, they are kept in a country where the study of Ancient Greece is kept alive, where Greek plays are performed either in the original or in English, and in the most erudite and scholarly fashion, like the Theban plays by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford last season and in London this year.

“Schoolchildren, among them my own son, have the privilege and joy of reciting verse and studying Homer in the original. By contrast in Greece, the study of ancient Greek in schools has been stopped. The impoverished language of today has been cut off from its natural roots.

“Visitors to museums (including that on the Acropolis) are frustrated by restricted opening times and high admission charges. Moreover, a new gallery close to the Parthenon to house the marbles would violate the Acropolis.

“The advocates of the demand for the return of the Elgin marbles, which stems from empty nationalist zeal and socialist politics, should direct their zeal and support towards Cyprus. The marbles must remain where they are, in a country which cherishes the classical tradition.”

3 December 2024

The Spring 2015 ArtWatch UK Journal

The forthcoming ArtWatch UK members’* Journal examines restoration problems; betrayals of trust; the role of conservators in the illicit trade in antiquities; and, the escalating commercial scramble by museums that is disrupting collections and putting much of the world’s greatest art at needless risk.

* For membership details, please contact Helen Hulson, Membership Secretary at hahulson@googlemail.com

ArtWatch UK Journal No. 29

Preview ~ Journal No. 29’s Introduction:

MUSEUMS, MEANS and MENACES

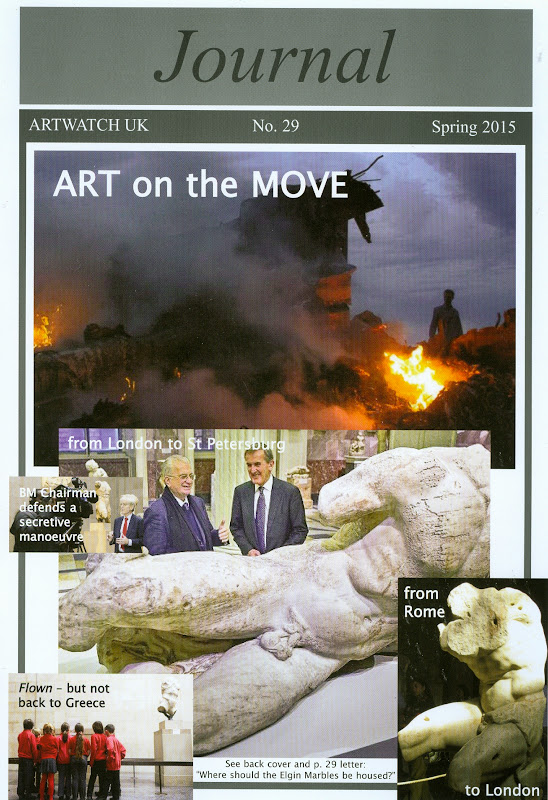

Museums once provided havens for art and solace to visitors. They were cherished for their distinctive historically-given holdings and their staffs were answerable to trustees. Today they serve as platforms for conservators to strut their invasive stuff and as springboards for directors wishing to play impresario, broadcaster or global ambassador. Collections that constituted institutional raisons d’être, are now swappable, disrupt-able value-harvesting feasts. Trustees are reduced to helpmeet enablers of directorial “visions”. No longer content to hold display and study, museums crave growth, action, crowds and corporately branded income-generation. For works of art, actions spell danger as directors compete to beg, bribe and cajole so as to borrow and swap great art for transient but lucrative “dream” compilations. Today, even architecturally integral medieval glass and gilded bronze Renaissance door panels get shuttled around the international museum loans circus.

Above, a window that depicts Jareth – one of no fewer than six monumental windows depicting the Ancestors of Christ that were removed from Canterbury Cathedral (following “conservation”) and flown across the Atlantic to the Getty Museum, California, and then on to the Metropolitan Museum, New York. (For a report on how such precious, fragile

and utterly irreplaceable artefacts become part of the international museums loans and swaps circuit, see How the Metropolitan Museum of Art gets hold of the world’s most precious and vulnerable treasures.)

Above, top, one of Ghiberti’s Florence Baptistery doors (which were dubbed “The Gates of Paradise” by Michelangelo) during restoration. Above, one of three (of the ten) gilded panels from the doors that were sent from Florence to Atlanta; from Atlanta to Chicago; from Chicago to the Metropolitan Museum, New York; from New York to Seattle; and, finally, from Seattle back to Florence. To reduce the risk of losing all three panels during this marathon of flights, they were flown on separate airplanes.

In such an art-churning milieu this organisation’s campaigning becomes more urgent. Fortunately, our website (http://artwatch.org.uk/) has increased our following fifty-fold – and see, for example: “How the Metropolitan Museum of Art gets hold of the worlds most precious and vulnerable treasures”. Here, we publish an abridged version of the fifth lecture given in commemoration of ArtWatch International’s founder, Professor James Beck, and examine persisting betrayals of trust, errors of judgement and historical reading, problematic “conservations”, and questionable museum conservation treatments of demonstrably looted antiquities. For these we warmly thank Martin Eidelberg, Alec Samuels, Alexander Adams, Einav Zamir, Selby Whittingham and Peter Cannon-Brookes. We commend two books, one for its freshness of voice, the other for a pioneering combination of high-quality images and scholarly texts in coordinated print and online productions. We also reproduce our online archive and related letters to the press.

Last July the outgoing chairman of the British Museum’s board, Niall Fitzgerald, disclosed in the Financial Times that because the director, Neil MacGregor, “obviously isn’t going to stay for ever” it was right that a new chairman [in the event a long-standing BM trustee and former editor of the Financial Times, Sir Richard Lambert] should lead the search for his successor. In December – and with levels of secrecy that would have thrilled his one-time mentor at the Courtauld Institute, Anthony Blunt – MacGregor dispatched one of the most important free-standing Parthenon sculptures, the carving of the river god Ilissos, to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. In lending Ilissos to St Petersburg just months after Russian troops had annexed part of Europe and Russian-armed separatists in Eastern Ukraine had brought down a Malaysian Airlines Boeing with a loss of 298 lives including around 100 children (see cover), the British Museum conferred an institutional vote of confidence in Putin’s Russia at a time when the West has mounted economic sanctions against his incursion and his continuing de-stabilisation of Eastern Europe. Moreover – and in a gratuitously provocative manner – by subjecting one of its most precious and controversially held works to needless and inherent risks, the British Museum presented its institutional a*** to everyone in Greece who is seeking to re-unite all of the surviving Parthenon carvings. On 9 December 2014 we protested in a letter to the Times (“Where should the Elgin Marbles be housed?” – see p. 29) that the action had gravely weakened the case for the British Museum retaining its controversially held “Elgin Marbles” and that it constituted a failure of imagination and a dereliction of duty on the part of the museum’s trustees.

Above, the carved figure of Ilissos, as displayed (top) at the British Museum, in the context of the surviving group of free-standing figures from the West pediment of the Parthenon; and, (centre and above) as displayed when on loan to the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Above, details of the back of Ilissos, (as photographed by Ivor Kerslake and Dudley Hubbard for the 2007 British Museum book, “The Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum”, by Ian Jenkins, a senior curator at the museum) showing the faultline in the stone that runs through the entire figure.

Perhaps the provocative loan was a piqued riposte to Mr and Mrs George Clooney’s attempts to have the British Museum’s Parthenon sculptures returned to Athens? Or, perhaps, simply a flaunting confirmation that nothing within the museum’s walls is now considered sacrosanct. In any event, 5,000 objects were put at risk (see below) last year in pursuit of MacGregor’s desire to transform the great “encyclopaedic” museum into a glorified lending library – or, as he puts it, into “a universal institution with global outreach”. The loan to Russia breached a two centuries old honouring of the original terms of purchase which required the Parthenon carvings collection to be kept intact. We now learn that those sculptures are to be further denuded with three more loan requests under consideration. We have supported the British Museum’s retention of the Elgin Marbles for over a decade, in print and in debates in New York, Athens and Brussels. (See Journals 19, 20, 25 and 26.) A key consideration was the relative safety of the sculptures in London and Athens. This latest policy reversal tips that balance in favour of Athens and thereby blows the moral case for the retention of the sculptures in London. It makes it impossible for us to maintain our previous support.

Such was the secrecy of this operation that the British Government was informed of it only hours before the story broke in a world-exclusive newspaper report. Under its new chairman the museum’s board proved supine, authorising the manoeuvre despite its own concerns over the sculpture’s safety. Officially, the museum betrays an almost delusional insouciance on the inherent risks when fork-lifting, packing, fork-lifting, lorrying, fork-lifting, flying, fork-lifting, lorrying, fork-lifting, unpacking – twice-over – an irreplaceable world monument on a single loan. Art handling insurers testify that works are at between six and ten times greater risk when travelling. Against this actuarial reality, the museum’s registrar variously boasted that “museums are good at mitigating risk”; that the loan had needed undisclosed insurance; and that, if intercepted by thieves, “they would be unable to sell it”. The source of this institutional confidence is unclear. As we reported in 2007 (Journal 22, p.7), in 2006 the British Museum packed 251 Assyrian objects – including its entire collection of Nimrud Palace alabaster reliefs and sent them in two cargo jets to Shanghai, with stop-overs in Azerbaijan, thus subjecting the fragile sculptures to four landings and take-offs. On arrival in Shanghai the recipient museum’s low doorways and inadequate lifts required the crated sculptures to be “rolled in through the front door”. Three crates remained too large and had to be unpacked “to get a bit more clearance”. One carving was altogether too tall and “we had to lay him down on his side” to get him in, the British Museum’s senior art handler said. It was then found that the museum’s forklift truck was unsafe (and needed to be replaced), and, that “a few little conservation things had to be done”.

When the resulting quid pro quo loan of Chinese terracotta figures was sent to the British Museum the following year, two dozen wooden crates were held for two days at Beijing airport because they were too big to enter the holds of the two cargo planes that had been chartered. When the crated sculptures arrived at the British Museum, they were also found to be too big to pass through the door of the Reading Room (from which Paul Hamlyn’s gifted library had been evicted – then temporarily, now permanently). The door frame was removed but three cases were still too big. These had to be unpacked outside the temporary exhibition space in the Great Court. The “temporary” misuse of the Reading Room became a permanent fixture until the new £135m (on a £70-100m estimate) exhibition and conservation centre in the antiseptic style of a Grimsby frozen food factory was opened last year (see back cover). Having insultingly evicted the Paul Hamlyn art library, it is now being said that the Reading Room “lacks a purpose” and that Mr MacGregor is musing on possible alternative uses to … reading books in a fabulous library previously occupied by national and international literary and political luminaries. One of these alternatives would be to raid the museum’s own diverse and encyclopaedic sculpture collections so as to tell a singular, MacGregoresque multi-cultural world story. Were he to be indulged in this (English Heritage witters alarmingly that the Reading Room’s Grade 1 listing does not necessarily preclude changes of uses), the director would leave a monument to himself achieved by subverting the historically-resonant, listed purpose made classical building in order to patronise and spoon-feed future visitors who might better have made their own judgements on the relative merits of the artefacts held in the museum’s various assembled civilisations.

If the present lending policies are not curtailed a further monument to MacGregor’s reign will be found in the art handling facilities of the new “improbably large” conservation and exhibitions centre. These are such that a crated elephant would now “arrive elegantly, the right way up”. What – surprisingly – did not arrive was the exhibition of treasures from the Burrell Collection that is being sent on a fund-raising world tour. This tour was made possible by the overturning in the Scottish Parliament of the terms of Burrell’s bequest which prohibited foreign loans. The overturning was made with the direct support and participation of Neil MacGregor and the British Museum was to have been the tour’s first stop. (Only three voices against the overturning were heard in the Scottish parliamentary proceedings: our own; the Wallace Collection’s academic and collections director, Jeremy Warren; and, the National Gallery’s director, Nicholas Penny, who attacked the “deplorable tendency” for museum staffs to deny the grave risks that are run when works of art are transported around the world.) As we reported online (“A Poor Day of Remembrance for Burrell”, 11 November 2013, Item: MR MACGREGOR’S NO-SHOW AT THE SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT HEARINGS), after a reproach in the Scottish Parliament, Mr MacGregor replied: “It was suggested by the Convener on 9th September (column 33) that as the British Museum might be involved in helping organise the logistics of a possible loan, and as works from the Burrell Collection might be shown at the British Museum, I might find myself in a position of conflict of interest. I think I can assure the Convenor that this is not so. The British Museum would not profit financially from either aspect of such co-operation with our Glasgow colleagues…” In the event, the first stop of the world tour was at Bonhams, the auctioneers, not the British Museum.

Michael Daley. 1 March 2015.