To Criticise a Critic

An examination of certain pre-emptive scholarly/art market establishment strikes against a pending book that rejects the Rubens ascription of the National Gallery’s contested Samson and Delilah.

Michael Daley writes: Those who challenge art establishment scholars or institutions can suffer swift repudiation and denigration in lieu of frank and open debate, as I discovered when supporting Prof James Beck’s criticisms of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling restoration in the late 1980s. In the 1996 edition of the Beck/Daley Art Restoration – The Culture, The Business, And The Scandal, in a chapter headed “The Establishment Counter-attacks”, I noted:

“When criticized in this area, institutions react institutionally, which is to say, by deploying self-protecting mechanisms common to all establishments. The best and most favoured response is no response, implying that the criticism is inconsequential and deserves to be ignored. In those instances where a response is unavoidable, it is thought best to be made by proxy… When a direct defence is necessary, its tone becomes all important. By tradition, the tone ranges from amused disdain, through supercilious dismissiveness to outright disparagement and attempts to discredit personal or professional credentials.”

It seems little has changed and that responses to the imminent arrival of Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s book on the National Gallery’s supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah (NG6461 – The Fake National Gallery Rubens) have run true to institutional templates. As a case in point, take this even-handed Artnet account: “Is This Rubens Real? Inside the ‘Samson and Delilah’ Debate” by Jo Lawson-Tancred.

Lawson-Tancred reports an anonymous National Gallery spokesman’s claims that the picture “has long been accepted by Rubens scholars” and that the Gallery finds no cause to update its initial technical examination of the painting [as had been reported in its 1983 Technical Bulletin] and whose “findings remain valid.” The first part is true – Rubens scholars had so accepted the attribution. However, the insistence that the report on the then recently acquired, exhibited, and restored £2.53mn picture requires no updating disregards subsequent findings on this and other Rubens paintings.

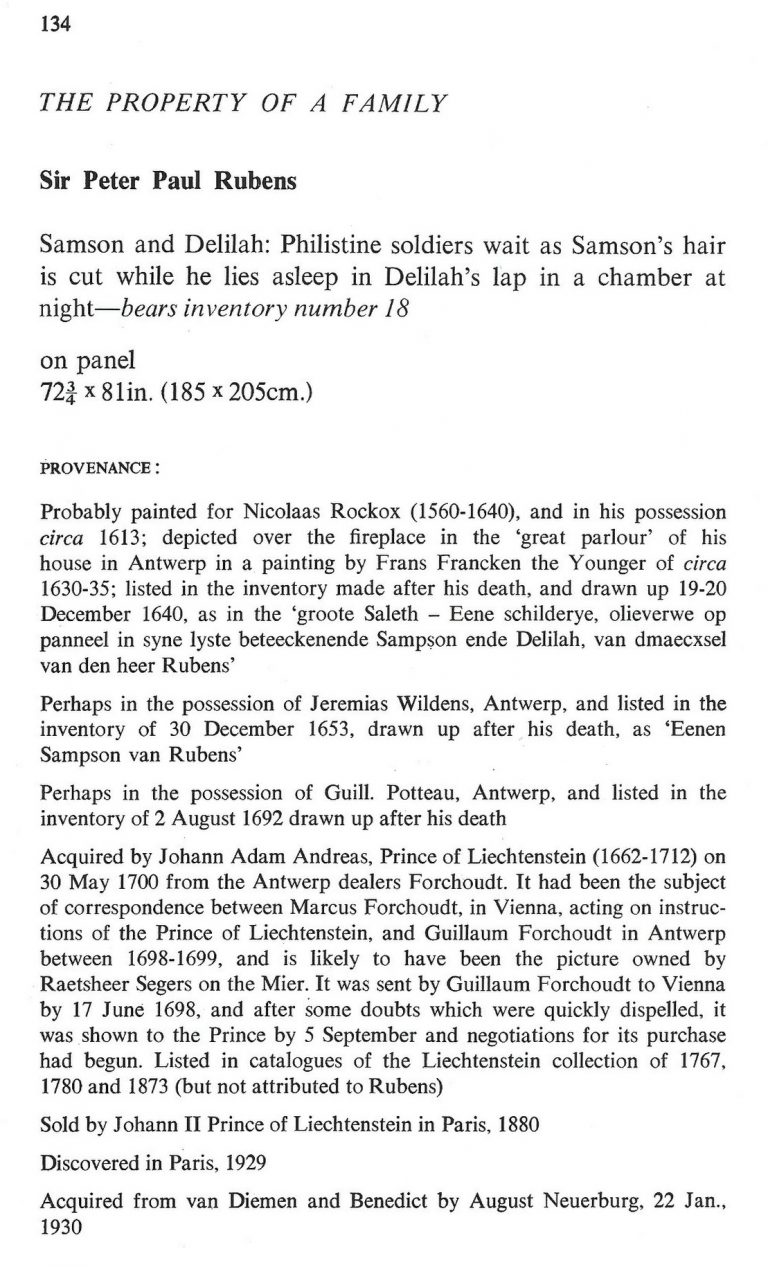

To be precise, the Gallery claimed in 1983: “At some time, probably during the present century, the panel was planed-down to a thickness of 3mm and subsequently glued onto a sheet of blockboard”. As Doxiadis and we have established the picture had emerged as a panel in 1929 – albeit ascribed to Honthorst. Crucially, it had remained a panel when sent to Christie’s, London, for sale in 1980 as an autograph Rubens – indeed it was precisely so described in Christie’s 1980 catalogue (see Fig. 1 below.) The picture’s physical state as a panel had been disclosed to Doxiadis by a Belgian banker who had wished to buy the picture for the Rockox House museum in 1977 and who again held it in Antwerp for its owner in 1980 before sending it on her behalf to Christie’s, London. Beyond any question, it was still an intact panel at that date.

WHERE’S THE BEEF?

Fig. 1, above: Christie’s 1980 sale catalogue entry on the Rubens-attributed Samson and Delilah panel. Note how the entry comprises a daisy-chain of “probablys” and “possiblys” – and also its parenthetical disclosure that, throughout its claimed long stay in the Liechtenstein Collection, this Samson and Delilah had not been judged a Rubens.

Given that we informed the National Gallery a quarter of a century ago of the picture’s confirmed physical status as a bowed and cradled panel in good shape in 1980, its 1983 technical account has long needed correction because the planing had not taken place before 1980, let alone in the 19th century. And yet, that manifestly unfounded suggestion that the planing might have occurred before the 20th century had been endorsed by Joyce Plesters, the Gallery’s Head of Science in the 1983 Technical Bulletin: “Unfortunately, as David Bomford has described, the back of the panel had been planed down to a thickness of only about 3mm and then the whole set into blockboard before the picture was acquired by the National Gallery…” In truth, it had not been set into the blockboard, but rather, as Bomford had correctly reported, and Doxiadis would later discover, it had been glued onto a blockboard sheet larger than itself and fitted into a new purpose made frame.

On the combined records of 1929 and 1980 that Doxiadis and we had uncovered – and as on Christie’s own published catalogue description – it followed that the planing could only have occurred after the picture was sold to the Gallery for its then world record Rubens price of £2.53million in 1980. Our concerns were compounded when informed (by the National Gallery’s then director, Neil MacGregor) that the Gallery had not followed its own procedure of preparing written curatorial and restoration reports on the picture’s desirability and condition to assist the trustees when they examined the picture (which had been loaned to the Gallery ahead of the sale – see below) to consider an authorisation of the purchase.

AN APPEAL TO AUTHORITY

In view of Doxiadis’s recently reported disclosures on the picture’s physical condition in 1980 (Dalya Alberge “Fresh doubt cast on authenticity of Rubens painting in the National Gallery,” ) Lawson-Tancred might have questioned or challenged the National Gallery’s abiding stance. Instead, she reported:

“…despite the marginal but adamant voices of researchers like Doxiadis, top scholars in the field support Samson and Delilah’s authenticity unequivocally. Chief among these is Nils Büttner, chairman of the Centrum Rubenianum in Antwerp, who is working on the Corpus Rubenianum, the definitive catalogue raisonné for the Flemish Baroque painter. He has previously described the doubts about Samson and Delilah’s provenance as “conspiracy theories.” However, Lawson-Tancred also noted that “Büttner [had] declined to comment on Doxiadis’s book”. While Büttner, presumably, has not yet read the unpublished book, his assertions received immediate support from players in the art trade:

“Büttner’s position is backed by his peers like Adam Busiakiewicz, a lecturer and consultant on Old Master paintings for Sotheby’s. He pointed out to the Telegraph that Doxiadis is not a scholar of the period and has mostly published on Greco-Roman antiquities previously. Though she ‘had a hunch the quality of the picture wasn’t good enough’, he said, ‘I think there are some misunderstandings about the painting.’”

On misunderstandings, Busiakiewicz (who seems also to be employed by the art market “sleeper-hunter” and former Philip Mould assistant, Bendor Grosvenor, on the latter’s “Art History News” blog site), paraded just such in his reported burst of professional condescension to Doxiadis:

“Busiakiewicz explained that a comparison between Samson and Delilah and other paintings by Rubens are complicated, especially when they were made decades apart. ‘He’s an artist that changed his style throughout his career,’ he said. ‘Art historians who specialize in paintings like Rubens’ can track these changes.’ It is for this reason that the National Gallery painting has been connected to Rubens’s interest in the work of Caravaggio and other Renaissance masters whose work he had, at that time, recently encountered while traveling in Italy.”

While it is widely known that Rubens underwent changes of manner in his later paintings, Busiakiewicz failed to acknowledge (or appreciate?) that Doxiadis, we, and other critics of the attribution, such as Dr Kasia Pisarek, have for decades pointed out and demonstrated that the Samson and Delilah is glaringly unlike the bona fide Rubens paintings made precisely in that brief period when the artist had just returned from Italy.

Specifically, we had reminded readers in November 2021 that:

“In a pioneering 1992 report, the scholar/painter Euphrosyne Doxiadis and the painters Stephen Harvey and Siân Hopkinson, conducted a focussed survey of six Rubens paintings of 1609 and 1610 and demonstrated that “All these display a consistency and quality of style which is not shared by the Samson and Delilah”. That report – “Delilah cut off Samson’s hair, but who cut off his toes? The case against the National Gallery’s ‘Rubens’ Samson and Delilah” – was placed in the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah dossiers and is published on the dedicated In Rubens Name website.”

WHITHER THE PANEL’S BACK

Above, Fig. 2: The covers of two ArtWatch UK journals given over to detailed accounts of the Samson and Delilah problems and shortcomings.

In issue 21 Kasia Pisarek wrote: “The Corpus Rubenianum project is based on the archive left by the late Dr Ludwig Burchard. Should it perhaps follow it less closely? Dr Burchard was an active Rubens attributionist in Berlin before the Second World War and in London afterwards. Several paintings formerly attributed to Rubens’s school or studio or even to another artist (such as Samson and Delilah), were reinstated by Burchard as by the master. I traced many of his attributions – he was not infallible in his judgement and changed his mind. Surprisingly, over sixty pictures* attributed to Rubens were later downgraded (in Corpus Rubenianum) to studio works, copies or imitations.” Pisarek adds: “they were, however, mostly portraits of small or medium dimensions.”

If a major work like Samson and Delilah might be considered something of an exception, Doxiadis supplies a possible explanation – Burchard was a relative of one of the owners of the dealing firm that had brought the supposed Honthorst to the marketplace.

*On the subsequent completion of her PhD thesis – Rubens and Connoisseurship: Problems of Attribution and Rediscovery in British and American Collections – Dr Pisarek remarked: “I traced many paintings attributed by Ludwig Burchard… At least seventy-five works he certified authentic were subsequently downgraded to studio works, copies, and imitations in the volumes of the Corpus Rubenianum, and the list is not complete… can we trust Burchard’s old rediscovery and attribution of the London Samson and Delilah?)

In issue No.11 we had written: “On December 17th 1998 Dr Jaffe [David Jaffé, then Senior Curator at the National Gallery] writes: ‘Sotheby’s auctioned Rubens Deluge as ‘oil on oak panel’ when, in fact, it was on a marouflaged panel’.” But how is this known? It was so, Jaffé discloses, “according to the condition report made in 1996-97 when the picture was loaned the National Gallery…” But no such condition report was made when the Samson and Delilah was loaned to the National Gallery by Christies ahead of the sale. That condition report on the Deluge had been prepared by the National Gallery’s timber specialist restorer, Anthony Reeve. As recently as 1982 Reeve had reported in the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin (see Fig. 7) that the Samson and Delilah was “one of only three well-made straightforward Rubens panels in the collection” – which panels, he elaborated, required stable humidity because otherwise “The effect of wood shrinkage on the exposed backs of the panel…is for the front to become convex, and perhaps slightly corrugated”. Had the Samson and Delilah been planed-down and glued to blockboard at that date there would have been no possibility of its back being subjected to environmental hazards. It might be thought inconceivable that the National Gallery should have lost recollection of Reeve’s testimony by the following year and when writing in the same publication. As the National Gallery’s senior picture restorer Reeve was held after his death by Neil MacGregor to be the “supreme practitioner of his generation.”

There are yet further confirmations of the panel’s still-then exposed back. Doxiadis had obtained a Belgian condition report on the Samson and Delilah which began: “On arrival on 4 March 1980, about 14.30 hours the painting mentioned above (panel, 185 x 205 cms) was in good shape…” Doxiadis’s account squared with testimony supplied to ArtWatch by the art critic Brian Sewell (an ex-Christie’s man who took pride in having there identified an oil sketch as the modello for the Rubens Samson and Delilah), namely: that the panel had not been mounted on blockboard; that the back of the panel had been painted in a darkish matt colour and was criss-crossed with supporting bars of wood; that because Christie’s customary stencil number was made with dark paint it had been superimposed over a patch of white paint Christie’s had applied to the panel’s back.

Presumably Busiakiewicz has yet to access the 1992 Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson report. For the record, the document I found in the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah dossiers was a copy of the picture’s 1929 certificate of authenticity written by the great but subsequently discredited Rubens specialist Ludwig Burchard who had observed: “The picture is in a remarkably good state of preservation with even the back of the panel in its original condition”.

A CRITICAL FORMATION ASSEMBLES…

Where Busiakiewicz patronises Doxiadis on an allegedly insufficient familiarity with the Samson and Delilah literature, Nils Büttner has been joined in that disparagement by Bert Watteeuw, the director of the Antwerp Rubens House. As John Smith reports in the EuroWeekly:

“The latest suggestion that this is a 20th-century copy comes from Greek art historian Euphrosyne Doxiadis in her new book The Fake Rubens although this accusation finds little support from one of Belgium’s top Rubens experts Bert Watteeuw. Not only does he pour scorn on her status as a genuine expert, suggesting that anyone of any standard would have already checked with his Antwerp Rubens House and other specialist houses about the painting. In addition, he also said: ‘the provenance of this painting is very well known throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. A provenance that can be trusted is always crucial’…”

This implied claim of a trustworthy Rubens provenance was a brazen sleight of hand: what John Smith was not to know is that, as shown above, the provenance concerned at no point confirmed the painting as being by Rubens’ hand. Being thus kept in the dark, poor Smith could only but conclude: “Whilst the National Gallery has kept a dignified silence on the matter of the painting, it is no doubt delighted that one of the great Rubens scholars has come out publicly to dismiss the fake claim by Doxiadis which Watteeuw considers is purely invented to promote her book.”

Delighted as the National Gallery might be and while its Trappist silence might do yet further service as an institutionally imperative damage limitation exercise, it remains an untenable stance because, as one very distinguished former National Gallery trustee at the time of the Samson and Delilah purchase told Doxiadis, “the truth will come out – it always does”. As for Watteeuw, for a Rubens scholar at the supposed top of his professional tree to resort to professionally unfounded claims and personally directed abuse is as counterproductive as it is contemptible.

Moreover, in this regard, Watteeuw might be considered a serial offender: when apprised of negative AI findings on the Samson and Delilah panel he told another journalist, Colin Clapson (‘Fake Rubens in London’s National Gallery? This painting is genuine” counters Rubens House director Bert Watteeuw”) that Doxiadis’s soon-to-be-published book is “Complete nonsense and not based on facts. To begin with, I do not know this art historian and that is a sign. Most researchers on Rubens have passed by our Rubens House and the Rubenianium, the Rubens Library, in the search of sources and information,’ says Bert Watteeuw, the director of the Antwerp Rubens House. ‘Moreover, Doxiadis has an agenda of her own: to promote her book and that seems to be working well. In such cases conspiracies à la Dan Brown are more interesting than science.’ Whilst attacking its critic, Watteeuw gifts the National Gallery a clean bill of scholarly probity on its protracted silence: “‘The painting ‘Samson and Delilah’ in London is a genuine Rubens, a masterpiece. It is logical that the National Gallery does not want to comment or discuss its authenticity,’ he says.”

DISALLOWED TESTIMONY

In view of the above it might seem that among Rubens establishment scholars generally and for the National Gallery itself, nothing can be allowed to count as evidence against the challenged panel’s Rubens ascription. For example, in 2021, the brushwork of the Samson and Delilah was compared with that found in no fewer than 148 uncontested Rubens paintings. As Dalya Alberge noted in the Guardian (“Was famed Samson and Delilah really painted by Rubens? No, says AI”), “Its report concludes: ‘The AI System evaluates Samson and Delilah not to be an original artwork by Rubens with a probability of 91.78%.’ In contrast, the scientists’ analysis of another National Gallery Rubens – A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning – came out with a probability of 98.76% in favour of the artist.”

Such disinterested testimony is dismissed by the affronted – and perhaps professionally discomfited – scholarly grandees: “Watteeuw also dismisses AI research dating from a few years ago. ‘When that appeared, we engaged in extensive behind-the-scenes dialogue with that Swiss firm that had carried it out. AI can only work if you train it with an artist’s entire oeuvre. That was not the case at that time.’” (Watteeuw was here echoing Bendor Grosvenor’s mis-characterisation of the Swiss firm: “It is simply not possible to determine whether a painting is by Rubens by relying on poor quality images [sic] of not much more than half of his oeuvre…”) First, there is once again, as with Doxiadis, an implicit professional slur on the firm in question. Second, there is yet further evidence that logic is underemployed by many art establishment players: if, given the very great distinctiveness of Rubens’ style and painterly applications, you can find no visual correspondences when comparing the Samson and Delilah’s brushwork with a single one of 148 secure Rubens paintings, why would you be likely to find such correspondences in another batch of equally secure Rubens paintings? At this point, calling for yet more extensive AI tests on a vast oeuvre – and one with ever-shifting boundaries – is procrastination, the obliging sister of obdurate institutional silence.

CAN’T SEE – OR WON’T SEE?

Professor James Beck once remarked that too many of his peers “look with their ears” and that it is “only the artists who can see things clearly”. It so happens that all the principal critics of the Samson and Delilah picture – Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson/Daley/Pisarek – happen to have trained as artists, as Beck himself had done. Doxiadis noticed what no Rubens scholar, so far as we know, had noticed: that while Rubens painted with round brushes, the shadowy author of the Samson and Delilah had deployed flat brushes.

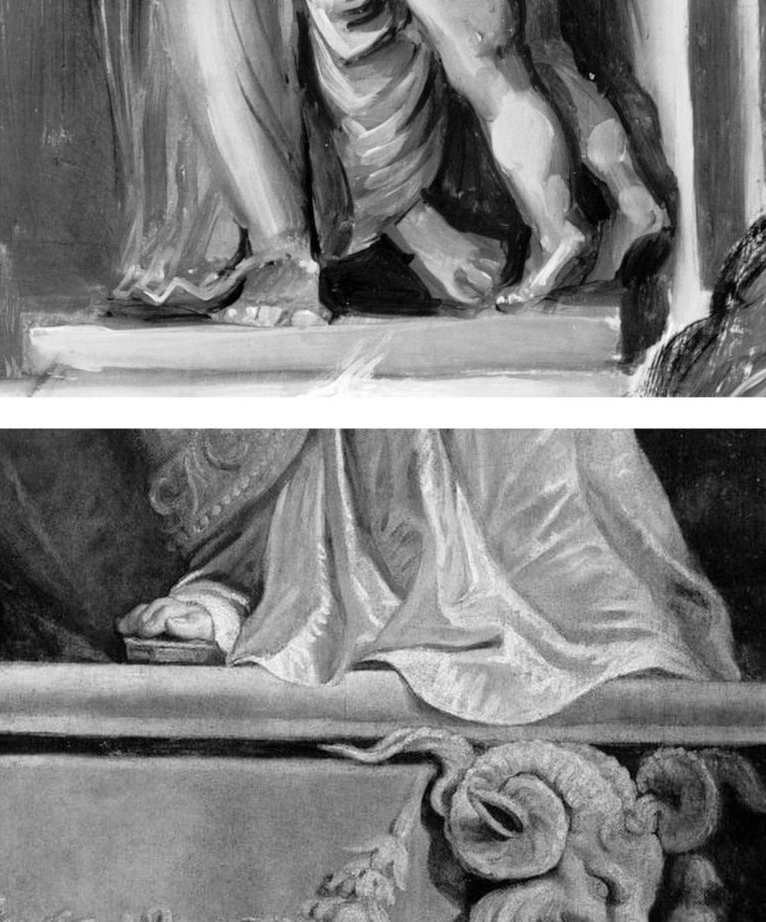

Above, Fig. 3: Top, detail of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah; above, detail of Rubens’ The Raising of the Cross, Antwerp Cathedral. Where the former is claimed to be a lost picture Rubens painted in 1609-10, the latter was indisputably made by Rubens between 1610-11. Such pronounced differences in brushwork are inconceivable as that of two autograph paintings made at the same moment in Rubens’ oeuvre. Who, looking at this photo-comparison, could believe that Rubens had flitted between the ugly angular Cubist faceted feet in the Samson and Delilah statue (– try counting the toes and note the Art Deco zigzagging hem), and the superb plastic fluency, grace and anatomical fidelity seen throughout the Raising of the Cross?

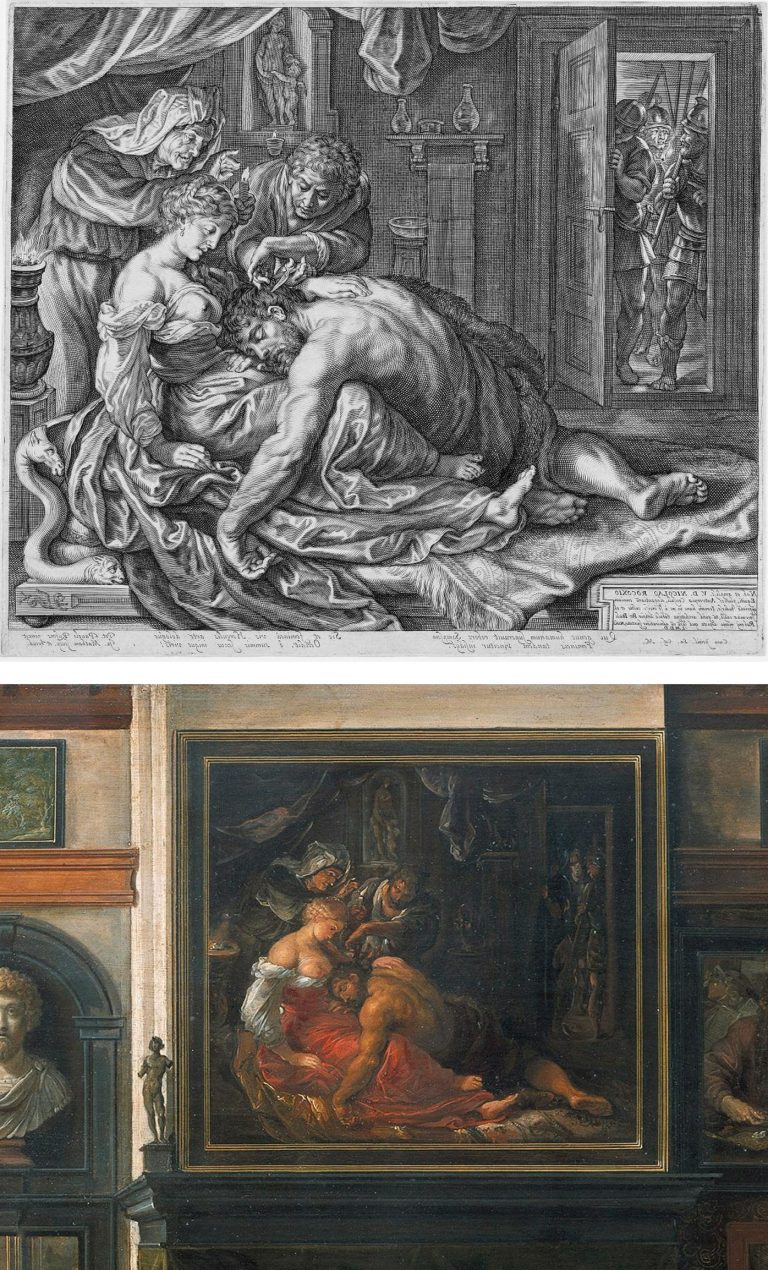

Above, Fig. 4: Two copies of the lost original Rubens Samson and Delilah – Top, Jacob Matham’s c. 1613 engraving (here reversed); bottom, Frans Francken II, a detail of his oil on copper depiction of the Grand Salon in Nicolaas Rockox’s House, made between 1615 and before 1640. Neither copy shows the cropped right foot found on the National Gallery picture. No one has cited a similarly cropped limb in any finished Rubens painting.

Above, Fig. 5: The National Gallery’s supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah painting.

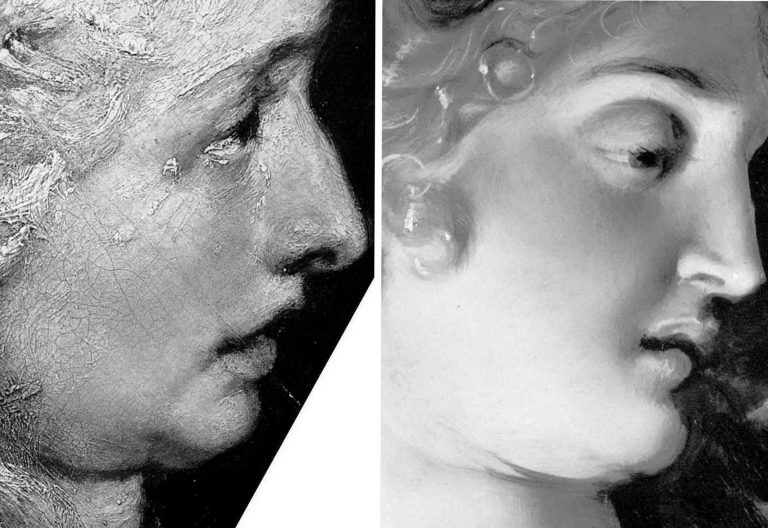

Above, Fig. 6: Left, a detail (from the left wing) of Rubens’ 1609-1610 The Raising of the Cross, Antwerp Cathedral. Right, a detail of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah which Christopher Brown (David Jaffe’s predecessor as Senior Curator at the National Gallery) dates at “c.1609” and Jaffé puts “about 1610”. Among the National Gallery picture’s countless visual disqualifications, we would cite: the thinness of the paint; the absence of a 17th century craquelure; the irresolute profile; the cinematic lighting of the head; and, the anatomical and perspectival travestying of Delilah’s nose/mouth/chin configuration.

For many more disqualifying photo-comparisons, see Abigail Buchanan’s “The National Gallery ‘masterpiece’ that’s probably a fake”.

TANGLED DOCUMENTARY WEBS…

Such clinching visual evidence, however, leaves Adam Busiakiewicz unmoved and unpersuaded. He tells the Daily Telegraph that the National Gallery Samson and Delilah could be in no one but Rubens’ hand – viz: “‘It is a really stonking great picture,’ he says. ‘The textures, the sumptuous drapery, the muscular back – no one except Rubens could have painted that.’” Each to his own art critical estimations, perhaps, but what happened to the Samson and Delilah when in the National Gallery’s restoration studios is – or should be – a matter of scrupulously recorded and reported facts. We are now faced by a major art institution that cannot/will not give a proper and credible account of its own actions; that effectively denies, even, the historical record of its own doings. Consider the recorded facts: (1) it is a matter of record that this painting emerged in 1929 as a sound panel and that it remained so in 1977 (when exhibited in Antwerp); (2) it is known that in 1980 the picture was a panel when it was dispatched to London; when it arrived in London; and, when it was sold in London to the National Gallery; (3) it is known that when in London and on exhibition at the National Gallery it remained a panel in 1982 (- see Fig. 7 below). However, it is also known that the following year the National Gallery claimed – after the picture had been restored at the Gallery – that it was not now a panel at all – and, indeed, that it had not been a panel for a very long time and possibly, even, into the 19th century or beyond. This extraordinary denial of the picture’s own documented historical record might seem inexplicable in a major national institution, but it is by no means unprecedented – and nor, for that matter, is the Gallery’s effective outsourcing of its own defence to obligingly helpful scholarly proxies.

Not the least consequence of misleading institutionally-official accounts is the corruption of subsequent scholarship and the making of monkeys out of good faith and technically trusting patrons. In part-defence against widespread and prolonged criticisms of its notoriously over-energetic techno-adventurist restorations, the National Gallery ran a series of didactic, so-called “Making and Meaning” exhibitions. One such in 1996-97 was Rubens’s Landscapes. It was organised jointly by the Gallery’s then senior curator, Christopher Brown, and by its senior restorer, Anthony Reeve. The exhibition was sponsored by Esso UK plc and its chairman and chief executive, K.H. Taylor, expressed pleasure in being associated with “the quality of research and scholarship that are the Gallery’s hallmarks”. In turn, the then National Gallery director, Neil MacGregor, expressed gratitude to Esso for its generosity, for year after year, in enabling the Gallery to “present to the public recent research on how and why the pictures were made”. In a section on the rigorously high standards of professional panel making in 17th century Antwerp it was noted that panels were marked with their makers’ monograms and that the panel back of Rubens’s “Chapeau de Paille” portrait bore Antwerp’s coat of arms and the carved initials of its maker, Michiel Vriendt. However, with the Samson and Delilah no such assurance was offered. Instead, the reader seemingly learns – with a nod to the contrary testimony of Reeve and Bomford/Plesters (see Fig. 7 below) that “A particularly fine panel made for Rubens by an Antwerp panelmaker is that for the Samson and Delilah, painted about 1609 for Nicolaas Rockox…” But then, after a section reprising Reeve’s own 1982 Technical Bulletin account of the risks posed to such fine panels by fluctuations in humidity, comes an abrupt claim that “The Samson and Delilah was planed down to a thickness of about three millimetres and set into [sic] a new blockboard panel before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 and so no trace of a panelmaker’s mark can be found…”

Now, in Fig. 7 above we see two incompatible accounts that were made and published just a year apart in successive National Gallery Technical Bulletins. Which of the contrary pair might be taken by the public and future scholars to be the more reliable and trustworthy record? Reeve’s account had preceded that of Bomford/Plesters – he had seen and reported what he saw and knew. Brown must therefore have found himself in the unenviable position of having to choose between Reeve’s earlier account and the later contrary one of Bomford/Plesters. That is, he had either to accept that the picture came into the Gallery after it had been planed down by some unknown party at an indeterminate date and that Reeve had imagined and chronicled an entirely fictional panel comprised of “six [sic] horizontal oak planks, carefully planed and jointed”, or, recognising that Reeve of all people was unlikely to have confounded a new sheet of blockboard with an early 17th century Flemish oak panel and extol its technical virtues even among Rubens’s panels, or… what? What could Brown say of the Bomford/Plesters account when he was aware that the picture’s own dossiers contained the already widely press-reported and potentially explosive 1992 Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson report precisely challenging the Bomford/Plesters account? Could he go down the middle and say that while the picture had come into the gallery as a panel in good shape – as Reeve had testified – when subsequently taken into restoration, it had been planed down and glued onto (not “into”) a new sheet of blockboard – and do so without offering any explanation for such a radical and inescapably material and historical evidence-erasing procedure? In the event, Brown did neither. Rather, he fudged a technically-incoherent mongrel account even though he and Reeve were the exhibition’s joint authors. That is, on the one hand he spoke of the Samson and Delilah having been a “particularly fine panel made for Rubens by an Antwerp panelmaker” and then, leaving a gaping, mystifying narrative hole in his own account, jumped to “The Samson and Delilah panel was planed down to… etc. etc.” This was a curatorial equivalent of the old comic book cop-out gag “With one bound, Jack was free”. It is not easy to conclude other than that it had seemed institutionally imperative to dissemble rather than clarify.

8 March 2025.