Now let’s murder Klimt

We have seen that works of art are under physical threat and that proper contemplation of them is becoming impossible through commercial exploitation and lax administration. (We will return shortly to the especially alarming case of the British Museum.) Aside from institutional mismanagement, all the while the stock of art is being debilitated in the name of its conservation.

It goes without saying that it is easier to destroy art than to create it. Gothic churches can be razed in an afternoon (and without explosives). With restoration injuries it is easy to recognise them but impossible to reverse them. Restoration is a one-way street: every little hurts; the harm that restorers can do individually and do do cumulatively can never be undone.

It was long ago contended that every picture restoration is a partial destruction, but every restoration is also a falsification. When destructive subtractions of material are completed, the restorer’s own painted additions begin. Restorers do not make the soundest judges of their own performance. Their accounts claim lots of different things simultaneously. First, that their additions (somehow) help to recover lost original conditions. Second, that their additions/ “recoveries” are made with removable synthetic materials so that the next restorer can easily impose his or her own interpretation of the lost original state. Worse, not only is there an expectation that each generation of restorers will have a different estimation of lost original states, within generations one restorer will have a different understanding from another. At the National Gallery (London) relativity has been written into the institution’s “philosophy” of restoration practice. It does not matter, the gallery claims, if restorers do their own things when attempting to recover authentic original states, so long as each version is realised “safely”.

Use your eyes – everything is in the looking

The proof of picture restoration’s pudding is not in self-protective philosophising or proclaimed professional “ethics”. It is in the looking – pictures are made by hand, brain and eye to be looked at, not to be bombarded by solvents, swabs, scalpels, heat-inducing imaging techniques, hot irons, adhesives, synthetic materials and such. In this regard, every day brings a new alarm.

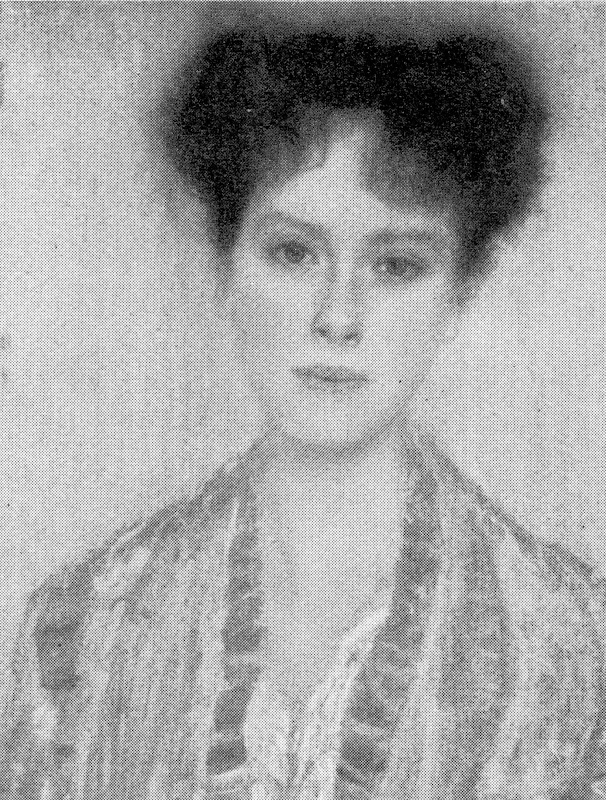

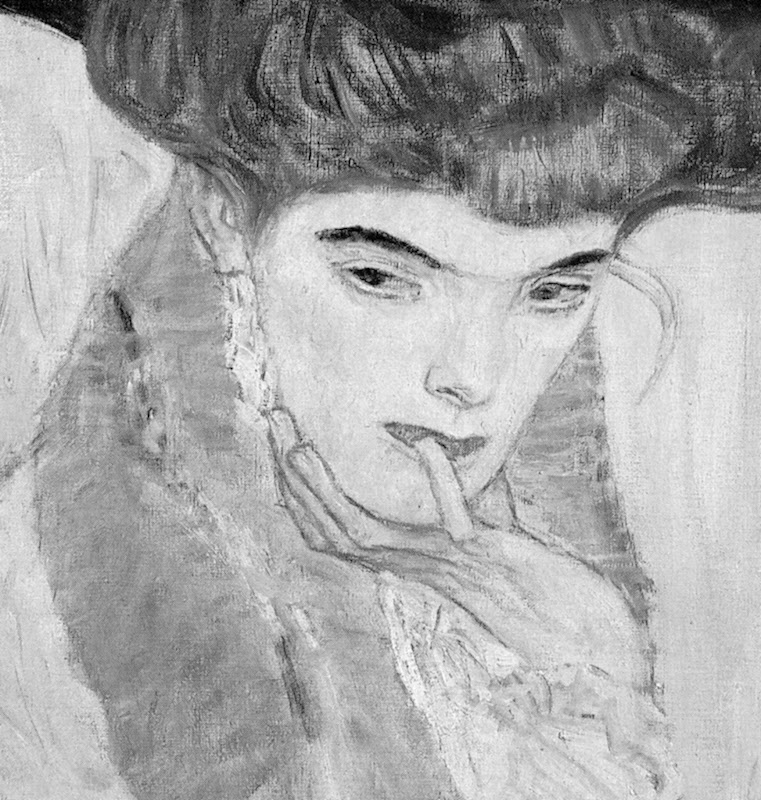

Yesterday, the Daily Telegraph and many other media outlets reported that a painting made in 1902 of a young Jewish woman (Gertrud Loew) by Gustav Klimt has been “restored” to her family. Such cases are heartening and just, but so often the accompanying photographs of returned works are, as here, disturbingly unlike early photographic records. The image shown above of this returned painting is from a printed paper copy of the Daily Telegraph. Newsprint photography is never of the highest quality but, with all allowances made, the strikingly washed-out appearance of the painting is evident also in the higher quality online reproductions, as below where all images are shown in greyscale to facilitate fair visual comparisons. What can be seen in all of these comparisons is a progressive and debilitating loss of values in the painting’s design, drawing, modelling and spatial ‘envelope’. Such sequences invariably run chronologically from darker, richer, sharper and better-modelled depictions, to lighter, brighter, flatter, more abstract, less plastic, less life-like arrangements. If dirt alone had been removed, the opposite effect would be obtained: all values would be more intense; all relationships would be more vivacious in their effects.

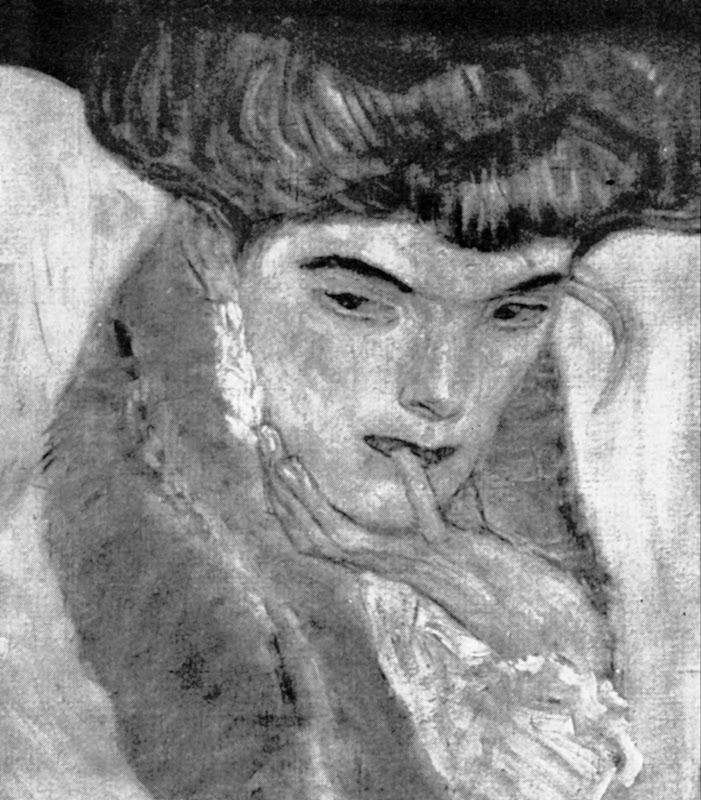

Above, these details show the painting as successively recorded a) before 1956 (top), when it was at most 54 years old and probably never previously restored; b) as before 1986 (centre); and, above c) as it is today (albeit, here, in an over-enlarged detail).

Above, top, a detail of the painting as before 1956; above, the detail as seen today. In this comparison we see, for example, that the contour of the subject’s left arm was more clearly drawn and shaded before 1956; that the shaded modelling around the eyes was more emphatic before 1956 than it is today; that the costume had two distinct parts – a darker over-garment and a lighter undergarment; and, that the tone of the flesh at the neck and above the undergarment was appreciably darker before 1956.

Above, a detail of Klimt’s 1910 picture The Black Feathered Hat shown (top) before 1956; as seen on a Dover postcard (centre); and (above), as seen today.

The Black Feathered Hat, as used on a CD cover of music accompanying an exhibition at the Neue Galerie, New York.

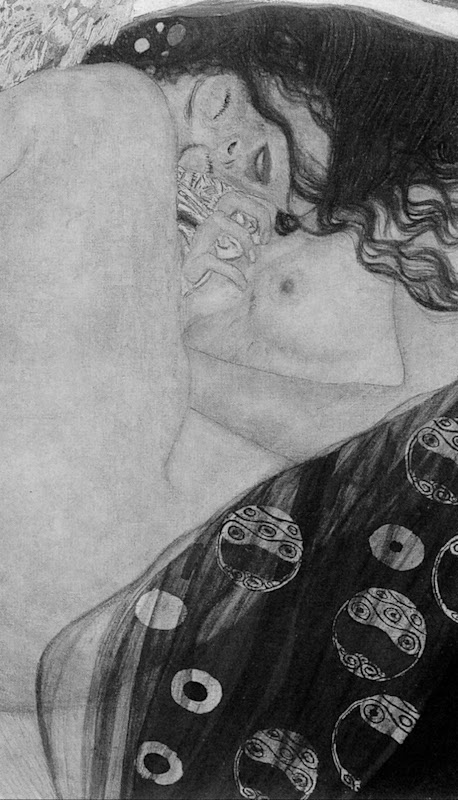

Below, a detail of Klimt’s Danae of 1907-08.

Above (top) Danae before 1956 and (above), as seen today. Note in particular the radically altered (and weakened) relationships at the crucially intense and psychologically-charged face/sheet/hand/breast configuration.

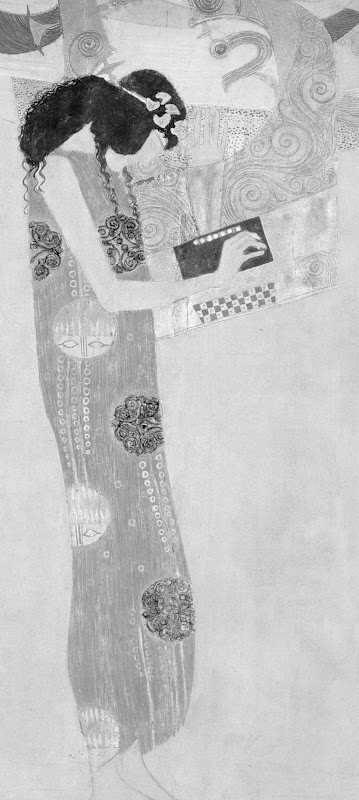

Below, the figure Poetry from Klimt’s 1901-02 Beethoven Freeze, before 1956 (top) and today (bottom).

Below, finally: SPOT THE DIFFERENCES – AND WEEP

Michael Daley, 5 June 2015.