Why Greece Does Not Need the Elgin Marbles

An (unpublished) paper by Michael Daley, Director, ArtWatch UK, that was delivered at the Economist’s Athens Conference, 12 March 2003:

Lots of reasons have been put forward in support of the campaign to remove the so-called Elgin Marbles from the British Museum. Individually, these justifications rarely withstand scrutiny, but cumulatively, their repetition has left many in Britain with the impression that under all the smoke there must be both a fire and a wrong in need of righting.

I wish to suggest today that, to the contrary, there are good reasons for contending that the restitution campaign is itself wrongheaded, unjust and culturally dangerous.

The original removal of the sculptures from the Parthenon and the ground and the walls of the Acropolis by Lord Elgin has been presented as theft when the British Museum’s legal title is today accepted by all parties to the dispute. The removal has long been caricatured as vandalism and desecration when, demonstrably, it constituted an act of rescue and celebration. This fact, too, has now largely been accepted.

Faced with the legitimacy of the British Museum’s ownership, the would-be “restitutionists” have appealed above the rule of law to the forces of sentiment – and forces, often, of distinctly nationalistic sentiment. “These sculptures mean so much more to us than they ever could to you” it is said. And even more disconcertingly:

“Without these sculptures we are not complete as a nation, they comprise our very soul.”

It would be hard for anyone to resist such morally coercive appeals – and the British are constitutionally inclined to want to “do the right thing” but, as it happens, resistance is no longer necessary: Greek scholars have testified that although the Parthenon indeed was, for members of late 19th century Greek society, a sacred symbol of the nation, the rise in the 20th century of tourism and economic modernisation has “taken them out of their role as symbols and gradually turned them into social goods”.

Confirmation of this transition appeared with a recent announcement that Greece plans to replace low-spending tourists with high spending ones by “showcasing Greek cultural traditions”.

With the decline of appeals to nationalistic sentiments, the claims of an Urgent Aesthetic Imperative have been advanced. “It is a crime against art”, the argument goes, “not to allow the component parts of a glorious entity to be seen whole.”

The cult of the dismembered-whole-in-need-of-reintegration was launched in 1945 by Thomas Bodkin with his seminal book Dismembered Masterpieces – A plea for reconstruction by International Action. It certainly is sad when artistic ensembles are scattered by history but in the case of the Parthenon sculptures it is worth recalling Bodkin’s comments on them:

“It is abundantly clear that the statues from the pediments, the portions of the frieze and the metopes now in England should never be re-integrated on their original sites. Those few sculptures which Lord Elgin did not remove have in the intervening one hundred and forty-two years been allowed to deteriorate into utter wreckage, corroded by wind and rain and the fumes ascending from the factories of Piraeus”.

Bodkin of course did not know of the notorious Athenian pollution that would be in train from the 1960s. Greek scholars have testified to the devastating consequences for the Acropolis monuments of that further, later pollution.

In the view of many here and abroad, Greece’s own past neglect and mishandling of the Parthenon and its remaining sculptures constitutes one of the greatest 20th century art conservation tragedies. To those of us who are professionally dedicated to the survival and welfare of art, the vocal opposition of Greece’s own scholars and art lovers to today’s Government-led scramble for development is certainly heartening but it does also confirm that vital lessons have not yet been learnt. These developments compel the observation that a nation that is showing indifference to its own patrimony and is cavalier with even its most precious historical sites, does not need to take on more heritage responsibilities. To those who might feel such a judgement harsh, we cite a single plea. It came recently from the island of Paros.

“…We are therefore obliged to ask for the support of the international academic community, suggesting that our overseas friends mail letters of protest to the Greek Minister of Culture, underlining their concern about the deliberate destruction of monuments on Paros. How is it possible to demand the return of the Parthenon marbles, while allowing the ruthless destruction of other ancient temples by unqualified employees?”

In the face of this actual, ongoing destruction, British restitutionists and museum personnel have taken to fretting about a need for “context”. What context? Reuniting the Elgin sculptures with the decaying Parthenon building is now, as Bodkin could already see, impossible. The new sculptural ensemble being mooted for Athens is that of a wholly severed – and, in fact, distinctly out of context collection. That is, it would be indoors, not out. It would be off Acropolis, not on. Even if every museum presently holding Acropolis sculptures were to return their works, the new “entity” would still remain incomplete because of early losses.

More embarrassingly, if all the surviving sculptures were to be returned to Athens tomorrow, they could not be joined by Greece’s own west frieze sculptures, which were removed from the Parthenon ten years ago and still await a decision on possible conservation treatments to stabilise their pollution-damaged surfaces. Were this problem to be resolved, it would still be necessary, before any assembling of the survivors could take place, for the sculptures that presently remain united with the Parthenon, to be “dis-united” from it, as if in emulation of Lord Elgin’s long condemned original actions.

In truth, of course, the Parthenon sculptures can never be “shown in context” because their original context is so long gone. It might now be imagined but it can never be replicated. We do know, however, that the sculptures originally survived as symbolic adornments to a temple standing on a reinforced hill and not in a modernist museum, to be built on stilts, on an important archaeological site in an earthquake zone and in the teeth of opposition from national and international scholars. Far from there being plans to recreate the original on-Acropolis context, there are even plans to remove, what one leading restitutionist terms, “the litter of unclassified stones” from the Acropolis in order to make more footpaths for more tourists. This is a particularly alarming prospect if Professor Snodgrass’s claim that eighty per cent of the Parthenon building is believed to be still present, is correct. There is, however, something much more important at stake in this dispute than the preservation and the right displaying of historical artefacts.

As mentioned earlier, the present hectoring demand that sculptures be moved from one museum to another is unedifying and dangerous. For one thing it constitutes nothing less than a government-led assault on the very idea of the internationally comparative museum. Greece – of all countries – does not need to be party to such a regressive manoeuvre.

It jeopardises international scholarly cooperation. It gives encouragement to those members of the museum sector in Britain who seem only too eager to shed as much as possible of what they see as so much colonial loot. I do recognise that members of the Greek Government have shown themselves to be aware of some of these dangers and that they themselves insist that the Elgin Marbles are the only sculptures for which demands will pressed. But what politician was ever able to bind his successors? Who today could guarantee that the removal of the Elgin sculptures from the British Museum would not instantly and forever thereafter be taken as a precedent for copycat campaigns in Greece and elsewhere?

For this artist, what is most saddening about the present campaign is that by trading the universal for the local, it conspires against a proper recognition of the true nature and full extent of Greece’s patrimony. There is a lot of wonderful art in the world but the truth that is being lost in this squabble over particular material objects is that Greek classical art is like no other art – it has done what no other art has ever done: millennia after its birth, it has emerged from death and neglect to seize the imaginations and enlist the passions of other people in other places. Greek classicism has even vanquished, later, better-preserved classical offspring. It has done so not by conquest or politicking but solely on merit; by example; on the unrivalled authority of its inventions. It is unfashionable to say so, but these inventions stand uniquely transcendent and enduring, outside of time, original context and regardless of geography and ethnicity, as artistic paradigms and exemplars.

Even within the antique world, Plutarch had marvelled that the sculptures of Pericles’ time, far from dating, retained a time-defying freshness and newness – as masterpieces. In the 19th century Karl Marx was stymied by the sheer force of Greek Art – to which, as a scholar at the British Museum’s reading room, he was regularly exposed. Marx’s grand meta-system was to be elegance itself: the so-called cultural superstructures of societies stand on, and are determined by, their economic bases; by their technical means of production. The more advanced the means of production, the more advanced the cultural manifestations. Primitive, economically backward societies, he planned to demonstrate, produce primitive backward art. Classical Greek art, however, blew this premise. How could it be, Marx was forced to ask himself, that an ancient art should not only continue to afford us with pleasure but should persist beyond its own time as both a standard and an unobtainable goal? The best explanation he could offer was that Greek art remained eternally charming because it represents the “the historical childhood of humanity, where it had obtained its most beautiful development.” This condescension will not do.

Greek forms have gripped modern minds, in world superpowers like Britain and the United States, not by their charm but by their potency, and their living relevance. Colonialism exposed modern Europeans to the charms of very many competing aesthetic value systems, but the power of Greece’s artefacts has remained uniquely awesome and persuasive – wherever they have come to rest.

The Greek temple, for example, stands perennially iconic as motif. It remains unequalled for its combined lucidity of construction and elegance of articulation. Which is why, for example, it remains incorporated into the fabric of Britain’s premier motorcar, the Rolls Royce – and with a winged victory as mascot on its bonnet. The Greek temple – and not, say, the pagoda – is as deeply entrenched in the modern unconscious as any Jungian archetype. Simultaneously, it confers dignity and reassurance to banking and stands guardian to free speech and debate in our modern universities and seats of government. In London, next to the historic Tower of London, a temple provides home to the names of British merchant seamen who perished in the Atlantic and Mediterranean at the hands of German U-boats and bombers.

Given the chance, Greek sculpture is seen to stand supreme in all company, in whichever museum – the bigger the museum, the greater the victory. The grandly ambitious international museum is now coming under fire politically, but it has been both an expression of and an agent for the modern renaissance of Greek antiquity. It is barely half a century since an historian like Hans Tietze could describe the artistic individuality of great museums as themselves “spiritual entities, and not merely as fortuitous accumulations of art treasures.”

Under today’s rules of correct, multi-cultural, discourse, museums like the British Museum may no longer say that ancient Greek art stands as the world’s best, as the most attractive and most humanly affirmative. But nowhere is this trait more apparent than in Bloomsbury in London, in the British Museum. By Insisting on seeing international, multi-cultural museums as repositories of loot; by fetishising original architectural/social contexts and localities; and by fostering nationalistic sentiment, we risk losing sight of a fundamental artistic truth: the sheer stand-alone transcendent quality of Greek sculpture. Pericles was given to inviting his dinner guests to see the Parthenon sculptures as they were being carved. Everyone who passes through London today can dine for free at Pericles’ table in a splendid purpose-built neo-classical hall – and certainly not in a cellar or basement as British restitutionists too often allege. It would be a tragedy if these supreme ambassadors for the finest art of sculpture were to be wrenched out of the great world forum of cultural voices that the British Museum comprises and in which they excel. Greece truly does not need to be party to such a brutal, disruptive act. Greece thrives, looks her very best in such elevated and various company. She lives. She needs nothing. Her primacy is absolute and unassailable. Well should be left alone.

Above, Michael Daley, Director ArtWatch UK, at the Acropolis, Athens, 2003.

CODA

The Economist conference – and the campaigning contribution made by Lord (David) Owen – was reviewed in the Greek newspaper eKathimerini – as is today’s meeting of Prime Ministers Keir Starmer and Kyriakos Mitsotakis in London.

In August 1998 a correspondent in the Sunday Times’ books section wrote (under the heading “All Greek”):

“A more positive and generous list of the achievements of the ancient Greeks than Frederick Raphael’s more grudging one is given by the scholar F L Lucas: ‘Within seven centuries this race invented for itself epic, elergy, lyric, tragedy, comedy, opera, pastoral epigram, novel, democratic government, political and economic science, history, geography, philosophy, physics and biology; and made revolutionary advances in architecture, sculpture, painting, music, oratory, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, anatomy, engineering, law and war… a stupendous feat for a race… whose most brilliant state, Attica, was the size of Hertfordshire, with a free population (including children) of perhaps 160,000′!”

In February 2000 we wrote (in “Pheidias Albion”, Art Review):

And let no one believe that foreigners alone reject Greek demands or condemn Greek practices. A few years ago, The Times carried this plea from Mrs Magdala Delfas:

“When in 1967 I left Greece under the colonels’ rule, my visits to the British Museum brought me solace. I was able to keep in touch with my cultural heritage outside the geographical and political confines of Greece.

“Later, I discovered to my delight and amazement that apart from the perfect display of the Elgin Marbles in their special gallery, they are kept in a country where the study of Ancient Greece is kept alive, where Greek plays are performed either in the original or in English, and in the most erudite and scholarly fashion, like the Theban plays by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford last season and in London this year.

“Schoolchildren, among them my own son, have the privilege and joy of reciting verse and studying Homer in the original. By contrast in Greece, the study of ancient Greek in schools has been stopped. The impoverished language of today has been cut off from its natural roots.

“Visitors to museums (including that on the Acropolis) are frustrated by restricted opening times and high admission charges. Moreover, a new gallery close to the Parthenon to house the marbles would violate the Acropolis.

“The advocates of the demand for the return of the Elgin marbles, which stems from empty nationalist zeal and socialist politics, should direct their zeal and support towards Cyprus. The marbles must remain where they are, in a country which cherishes the classical tradition.”

3 December 2024

Whiter than right

Robin Simon, editor of the British Art Journal and Honorary Professor of English at University College, London, has visited Chartres Cathedral and condemned its present restoration on a Facebook post and in a tweet:

“Just visited Chartres and I am appalled at the misguided ‘restoration’ that is covering the old stone walls in paint, with false pointing, creating a bland and uniform interior where the articulation of the architecture is crudely diminished. The history of the walls, of the building itself, is lost beneath a futile attempt to return the building to some imagined date in the distant past. What makes it much, much worse is the presence of bright electric lighting at crossing, choir and east end that destroys the effect of the greatest stained glass ever made, which used to cast the most wonderful haunting blue light throughout what was a uniquely ethereal interior. The magnificent chiefly 17th-century carved choir screen that wraps around the high altar end is also being whitewashed and the figures painted white, which is diminishing the three-dimensionality of these dramatic groups fully carved in the round. They now, remarkably, look flat, and have a smooth slimy surface with much of the miraculous crispness of the carving and detail lost.”

Robin Simon @robinsimonbaj:

“Just seen #Chartres #cathedral shocking #restoration. Walls painted, false pointing, glaring lights ruining blue light of glass, 17C carved choir screen flattened by white paint. State vandalism, arrogant architects, wrong-headed’experts’. Sign the petition https://bit.ly/2AmSRmN”

10:15 AM – 22 Oct 2018

Above, Fig. 1: Chartres Cathedral, with repainted vaulting in the choir contrasting with the existing nave and transepts in the foreground, Chartres, France, as published on July 11, 2012 in the New York Review (Photo: Hubert Fanthomme/Paris Match via Getty Images)

We have repeatedly attacked this restoration and on 16 December 2014 (“Chartres Cathedral Make-Work Scheme”) reported that this restoration had first been challenged in May 2012 by Alasdair Palmer in the Spectator – see his “Restoration tragedy” which began:

“Should old buildings look old? Or should they be restored to a condition where they look as if they could have been put up yesterday? Those questions are raised in a particularly pertinent form by the work going on at one of the most beautiful and inspiring of all old buildings: Chartres cathedral in France.

“Most of Chartres cathedral dates from between 1194 and 1230, when the bulk of the colossal stone structure, with its nearly 200 stained-glass windows and thousands of sculptures, was built. The extraordinary speed of its construction means that Chartres has an architectural and decorative unity that is unique among surviving cathedrals, most of which took a hundred years or more to complete, and were then altered drastically over the succeeding centuries.

“Chartres has suffered from the inevitable indignities inflicted by time. The paint with which the medieval artists originally covered the statues and the walls faded and flaked off within a few generations. Centuries of burning wax candles covered the interior with a thick layer of black soot. But Chartres remains far closer to the original building than almost any other medieval cathedral. The biggest effect of the intervening centuries since 1230 has been the accretion of the patina of age. A sense of the passing of time is part of the experience of looking at Chartres. The stone, the glass, the sculpture — it all looks very old, and its age is part of its fascination and its mystery.

“Or at least, it is in those parts of Chartres cathedral that have not yet been cleaned by the latest restoration project. It isn’t in those parts where the restorers have finished their work, for they look brand-new. There’s no patina of age here: there are only clean and bright surfaces.

“Is that an improvement? The restorers insist that it is…”

On 14 December 2014 Martin Filler, an architectural historian of Columbia University, New York, protested against the aims and consequences of such restorations in the New York Review (“A Scandalous Makeover at Chartres”):

“In 2009, amid a rising wave of other refurbishments of medieval buildings, the French Ministry of Culture’s Monuments Historiques division embarked on a drastic, $18.5 million overhaul of the eight-hundred-year-old cathedral. Though little is specifically known about the church’s original appearance—despite small traces of pigment at many points throughout the interior stonework—the project’s leaders, apparently with the full support of the French state, have set out to do no less than repaint the entire interior in bright whites and garish colors that are intended to return the sanctuary to its medieval state. This sweeping program to ‘reclaim’ Chartres from its allegedly anachronistic gloom is supposed to be completed in 2017.

“The belief that a heavy-duty reworking can allow us see the cathedral as its makers did is not only magical thinking but also a foolhardy concept that makes authentic artifacts look fake. To cite only one obvious solecism, the artificial lighting inside the present-day cathedral—which no one has suggested removing—already makes the interiors far brighter than they were during the Middle Ages, and thus we can be sure that the painted walls look nothing like they would have before the advent of electricity.”

Although the Chartres interior had initially been painted Filler noted that:

“…the exact chemical components of the medieval pigments remain unknown. The original paint is thought to have flaked off within a few generations and not been replaced, so for most of the building’s eight-century history it has not been experienced with painted surfaces. The emerging color scheme now allows a direct, and deeply disheartening, before-and-after comparison.”

Above, Fig. 2: left, Chartres cathedral stone work in its pre- and post-restoration conditions; right, the view looking SE in Chartres cathedral showing painted and unpainted areas adjacent to each other.

THWARTING A THREAT TO CHARTRES CATHEDRAL’S STAINED GLASS WINDOWS

As well as making a historically falsifying transformation of the interior, the funding of the restoration was itself exposing the ancient stained glass windows to needless risks. On 18 February 2016, Florence Hallett (“Chartres’ Flying Windows”) protested against plans to fly part of the cathedral’s stained glass to the United States as a fund-raising quid pro quo for support given by the American Friends of Chartres:

“While the cost of the controversial repainting of the cathedral’s interior has been met by the French state and donors including Crédit Agricole, Caisse Val de France et Fondation, and MMA assurances, the restoration of the cathedral’s famous glass has been funded in part by the American Friends of Chartres (AFC), an organisation that works ‘to raise awareness in the United States of Chartres Cathedral and its unique history, sculpture, stained glass, and architecture and their conservation needs.’

“Based in Washington, the AFC has ambitious plans to fund the restoration of the cathedral’s windows and sculptures. In 2013 it announced on its own site, and via the crowd-funding website razoo.com, that in return for funding the restoration of the Bakers’ Window (two lancets and a rose in the nave), the 13th-century glass would travel to a US museum. Indeed, the still extant webpage makes explicit the nature of the exchange, proclaiming: ‘American Friends of Chartres INVITES YOU to Restore and Bring to the United States a 13th-Century Stained Glass Window for Museum Exhibit’.”

Hallett’s specific challenge to the American Friends on the foolhardy plan to fly ancient stained glass windows to the United States seemed to have proved a successful deterrent. As we reported in a footnote:

“STOP PRESS: At 17.33 today, in answer to an email of 14 February, Florence Hallett was notified by the American Friends of Chartres that:

‘The exhibit of Bay 140 which had been envisaged will not take place because of cost reasons. And, to answer your question, of course all the proper authorizations from the French Ministry of Culture and other authorities had been secured by the DRAC-Centre Val de Loire, which had been nominated by the Ministry of Culture to execute the project. All the arrangements for the exhibit of Bay 140 would have been contractually arranged between the DRAC on behalf of the French authorities and the cultural institution that would have exhibited the window. American Friends of Chartres would not have been part of these contractual arrangements.’ ”

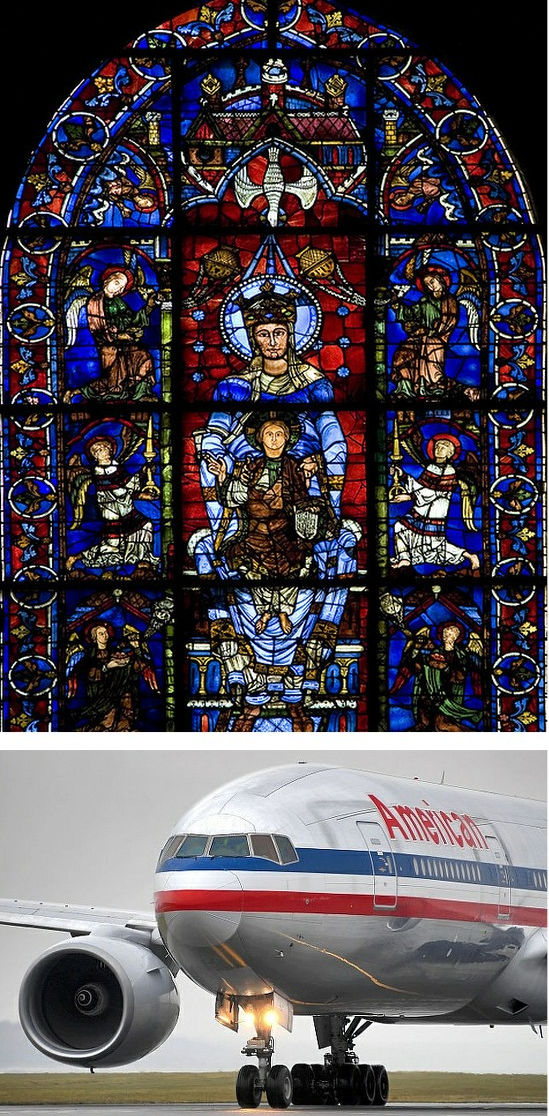

Above, Fig. 3: Top, a section of the Belle Verrière windows at Chartres. Above, a potential means of transport for early 13th century glass

If you owned or were the guardian of such ancient precious glass painting, would you pack it onto an aeroplane and dispatch it across an ocean to another continent? If “yes” you would be able to claim precedents: the ecclesiastical authorities at Canterbury cathedral sent the entire surviving six parts of an original cycle of eighty-six ancestors of Christ, once one of the most comprehensive stained-glass cycles known in art history, on a museum tour around the United States. (See “How the Metropolitan Museum of Art gets hold of the world’s most precious and vulnerable treasures”. )

Florence Hallett is the architecture and monuments correspondent at ArtWatch UK and visual arts editor at theartsdesk.com

Robin Simon gave the ninth annual ArtWatch International James Beck Memorial Lecture – “Never trust the teller trust the tale” – on 7 November 2017 at the Society of Antiquaries of London, in Burlington House, Piccadilly, London.

Alasdair Palmer has written frequently on art restoration for the Spectator and the Sunday Telegraph – see “Restoration tragedies” 26 August 2012.

Martin Filler is a prominent American architecture critic and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

WHO PROFITS?

The various strongly made cases against the Chartres Cathedral restoration project, rest in essence on the folly of attempting to replicate a speculative incompletely-informed notion of how an interior might have appeared many centuries ago when brand new. At Chartres this particular exercise is not only wrong-headed, it is, as Alasdair Palmer pointed out five and a half years ago, especially egregious: this attempted replication of an original state is inflicting a peculiarly brutal and unforgivable expunging of an ancient building’s historically lived evolving appearance. “Brutal”, because having been uniquely executed as a distinct artistically integrated whole this cathedral’s precious fabric had thereafter survived in uniquely unmolested form. Here was a building whose monumental lucidity might be considered a match for the timeless Parthenon. Here was a building which, unlike the Parthenon today, had not become a cadaver on a test bed for aggressively invasive conservation methods; which retained its forms and, even, an especial ancient illumination – one that, as Robin Simon attests, had once “cast the most wonderful haunting blue light throughout what was a uniquely ethereal interior”. Gone. And all in exchange for an $18million building contract that is already running over schedule and will, no doubt, end over budget.

When faced with incomprehensibly barbaric mistreatments of old art and monuments we must ask not only “why?” but “who profits?” The last is no slur. It is a necessary step towards explanations for otherwise inexplicably perverse cultural actions. It is indisputably the case that such high-prestige art and architecture restorations generate much employment, purchases of materials, scaffolding etc. – and that they can greatly enhance professional reputations. None of those consequences is necessarily wrong or bad in itself but due acknowledgement of them should constitute a component part of any calculus of appraisal of restorations or proposed restoration campaigns. It is concerning that in today’s rapidly accelerating restoration boom, material/professional interests are looming ever-larger as it proves increasingly easy to raise funds for large-scale building projects made on the back of the culturally-loaded, ethically coercive, names of “conservation” and “restoration”.

We have shown that it is European Union policy to increase activity in the arts sphere as a means of generating jobs in compensation for those being lost to less moribund economies: “I am especially happy to highlight the importance of culture to the European Union’s objective of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. At a time when many of our industries are facing difficulties, the cultural and creative industries have experienced unprecedented growth and offer the prospect of sustainable, future-oriented and fulfilling jobs.” See “Why is the European Commission instructing museums to incur more risks by lending more art?” and “The European Commission’s way of moving works of art around”.)

We know that the Chartres project has been part funded by the French Government. In this climate, greatly more vigilance and disclosure are now urgently required. No such project should ever be sprung on the world again. Monumentally dramatic proposals should be examined widely publicly and well in advance of the scaffolders moving in.

ASSORTED CONSERVATION RATIONALES

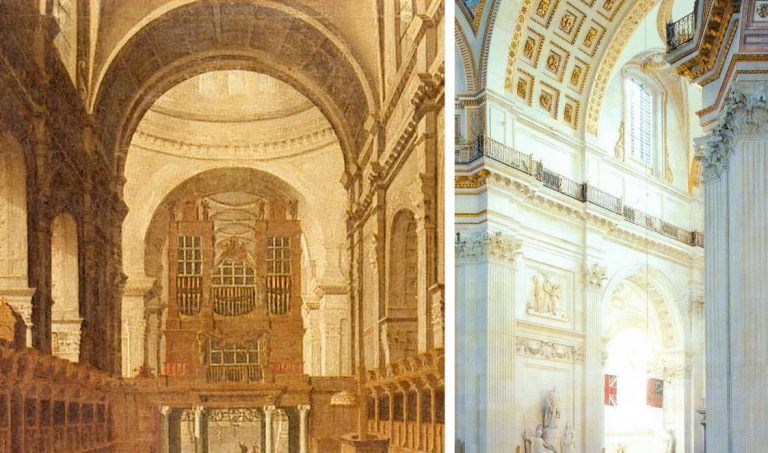

Above, Fig. 4: Left, the original interior of St Paul’s Cathedral as recorded in an undated but apparently 18th century painting that is owned by The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, at which date Sir Christopher Wren’s original painted finish comprised of three coats of warmly tinted oil paint that had been stipulated, according to Wren’s son, “not just for beautifying, but to preserve and harden the stone” still survived.

It was only disclosed during the recent under-researched stripping of the interior of St. Paul’s that Wren’s oil painted surface had contained lead white, ochre and black pigments so as to produce precisely the warm “stone colour” found in other Wren churches. Above, right, we see the new dazzling white surfaces of the building’s interior and its sculptures when illuminated by one of new electric chandeliers installed during the restoration because, as Martin Stancliffe, the cathedral’s then 17th Surveyor to the Fabric, put it, “the heart of my vision for the interior [was] to clean it and relight it”.

It is striking not only how frequently programmes have proceeded on artistically/art-historically injurious premises, but also how very contrary the aims of those various programmes can be. Where at Chartres cathedral attempt is being made to replicate a far-distant hypothesized original decorative scheme, at St Paul’s Cathedral, London, as Florence Hallett established, a major project to transform an interior was made on a reverse (and equally perverse) artistic/historical agenda. At St Paul’s, with a much more modern documented and visually recorded building, a programme was implemented to expunge the last traces of the original architect’s initial (and easily replicable) decorative programme with aesthetically falsifying – and, in the event, health-threatening – consequences even though the originally applied tinted oil paint was a known quantity, having survived intact in protected places.

In London too, much money was quickly raised but here it was spent stripping an interior down (with chemically-invasive materials never before used inside an occupied, still functioning cathedral) to create an a-historical modernist whiteness rather than to retain surviving traces or fully replicate the known original historic surface decoration. In consequence, not only has a powdery surface of stripped-down raw stone been exposed, but an already misleading appearance was subjected to the very greatly amplified artificial lighting that is shown above and was first established by Florence Hallett’s investigations: “Cleaning St. Paul’s Cathedral”, ArtWatch UK Journal 17, Winter, 2002; and “The supposedly ‘model’ restoration of St. Paul’s Cathedral”, ArtWatch UK Journal 18, Spring/summer 2003. Online, see Michael Daley: “Brighter than Right, Part 1: A Modernist Makeover at St Paul’s Cathedral” (1 June 2011) and “Brighter than Right, Part 2: Technical Problems of Protection, Health and Safety at St Paul’s Cathedral” (5 July 2011).

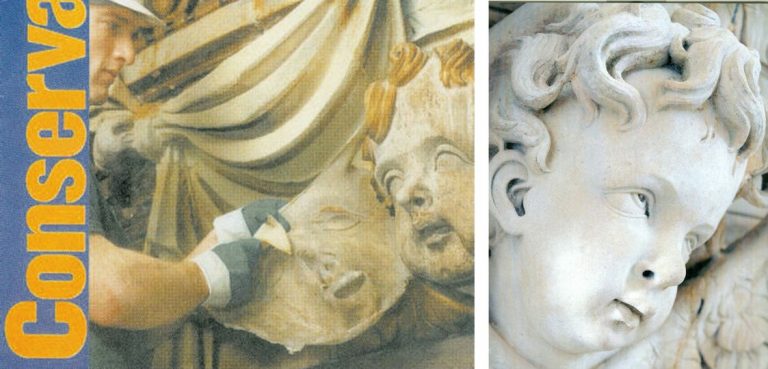

Above, Fig. 5: Left, a conservator removing a latex “cleansing pack” from a carved head at St Paul’s Cathedral, as published on the cover of Conservation News in May 2002. The journal reported that the latex was left on the surface for “one to four days” and that after its removal the stone was cleaned with “damp sponges and bristle brushes”. Right, a carved head at St Paul’s after being cleaned with water and bristle brushes. (Photography by Peter Smith/Jarrold Publishing.)

The chemical stripping-down of the cathedral’s interior surfaces to a novel whiteness was in accordance with an idée fixe of the 17th Surveyor to the Fabric, not of Sir Christopher Wren. In a 2005 programme note to a service held in honour of the restoration’s donors (“How the glory of St Paul’s was restored”), Mr Stancliffe declared that “the heart of my vision for the interior [was] to clean it and relight it”. In the Times of 10 June 2004 he announced his “pretty controversial” intention to introduce “six huge chandeliers” to flood the interior with artificial light. A year later he told the Guardian “we have installed new chandeliers and more lights” and expressed specific satisfaction on “seeing our initial vision gloriously realised.”

Above, Figs. 6 and 7: Top, the blotchy appearance of the stripped-down stone surfaces. Above, a simple, quick demonstration of the present dangerously powdery surfaces.

The brightness of this “restoration” was achieved at great aesthetic and material cost. As shown above, the surfaces have been left without patina and remain disfiguringly blotchy even after cosmetic attempts to mitigate the grosser consequences of the standardised indiscriminate cleaning method (see below). As for the supposed “conservation” purposes of this multi-million pounds programme, the interior’s now powdery surfaces are more vulnerable to environmental pollution and fluctuations of temperature and humidity than at any time in the building’s history. That the originally oil-paint protected surface of this limestone has been left as powdery as chalk was easily demonstrated by brushing the above sleeve against it.

CHECKS? BALANCES? TOOTHLESS WATCHDOGS?

Approval for the use of an experimental cleaning method on the interior of a publicly occupied and in-service cathedral had been given by The Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England in November 1999 following (claimed) earlier approvals by a bevy of heritage watchdogs: English Heritage; SPAB (The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings); The Victorian Society; and The Georgian Group. It is not possible to establish the precise chemical basis on which formal approval was given by the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England because, in breach of good conservation practices, the three technical parts of the eight part submission document were withheld on grounds of commercial confidentiality. For information on technical matters we had to rely on the cathedral’s own fluctuating (and often self-contradicting) accounts; on our correspondence with the 17th Surveyor to the Fabric, which he terminated in March 2003; and on documents obtained by cathedral employees whose health was adversely affected by the restoration.

The cleaning agent used on St Paul’s interior was an experimental, technically undisclosed, adaptation of a commercial product. In both its composition and effects, it earned censure from leading conservation experts (see below). It was a commercially available, latex rubber poultice laced with a mix of chemicals that were said to comprise an agent specifically tailored to be similar to the mild alkalinity of St. Paul’s Portland stone – that is, it was a special version of the “Arte Mundit” water-based paste manufactured by the Belgian company FTB Restoration. The instigator/director of the restoration, the architect and the 17th Surveyor to the Fabric at St Paul’s Cathedral, admitted (at a lecture on October 21st 2003) to having slim knowledge of matters chemical and of having devolved – “entrusted” – responsibility for the application of the new paste to the conservators of the firm Nimbus who themselves were learning on the job while the cathedral remained in full commercial and ecclesiastical use.

Professor Richard Wolbers, conservation scientist and solvents expert at the Winterthur Museum and Gardens, University of Delaware Art Conservation Department, was highly critical of a number of technical features of the programme and reiterated his fear that the authors “seem to have taken a poorly characterised material, a latex paste, and modified it with the addition of a considerable amount of EDTA – largely as an adaption in their minds, I suppose, of one of the main ingredients in the Mora’s AB57 cleaning system.”

(The Mora AB57 method was the notorious cocktail of EDTA, sodium and ammonium, detergent and other ingredients in a paste that was twice applied and twice washed off Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling paintings. We have chronicled the artistically disastrous consequence of stripping all organic material from the ceiling plaster. Within a generation the newly-exposed bare plaster had been secretly re-restored to remove powdering of the plaster, and then, in part-compensation, it was massively relit with coloured LED lights – see “The Sistine Chapel Restorations: Part I ~ Setting the Scene, Packing Them In” and “The Twilight of a God: Virtual Reality in the Vatican”.)

John Larson, the then Head of Sculpture and Inorganic Conservation at the Conservation Centre, National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, said that applications of moulding materials had contributed so much damage over the past 200 years that museums around the world “have now banned” their use, and that the application of liquid latex by brush or spray “has a dramatic effect on porous material such as stone…as it dries latex shrinks and clings tenaciously to the surface.” The effect of pulling it off the stone “exerts strong mechanical forces on the surfaces when the stone is carved and deeply undercut, as shown on the cover of Conservation News.” (See Figs. 5, 6 and 7 above.)

Above, Fig. 8: Left, sculptures at St. Paul’s being cleaned by steam jets; right, a detail showing the sculptures in the ambulatory of Chartres Cathedral on 11 July 2012. (Photograph by courtesy of Hubert Fanthomme/Getty Images.)

All horrible restorations are horrible in their own ways. Steam cleaning sculpture is considered an acceptable “conservation technique” even though it is visually deadening and leaves marble surfaces resembling white granular sugar and greatly more exposed to environmental pollution and fluctuations of humidity and temperature. We have witnessed conservators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, painting dead white steam-cleaned Greek marble carvings with water colours. One, when asked what he was doing, replied that he was “putting back the patina” destroyed by the cleaning. That, presumably, is why the Greek sculptures at the MET now sport a uniformly tasteful biscuit-coloured “patina” regardless of their age and geographical origins. As seen above, at St Paul’s Cathedral the all-white, sans-patina effect found favour and sculptures were left as raw-white as the building itself. At Chartres, however, the new visually deadening whiteness of the sculptures is the product of yet another method and philosophy. The sculptures are not being stripped down to the innate interior whiteness of the stone but are having a white skin of paint superimposed – before also being further brightened by artificial lights. The aesthetic, psychological and spiritual consequences of this practice at Chartres can be seen above right where just a few years ago the not-yet “restored” figures in the ambulatory still shared our common spaces. There, among us, touchable and as if alive, they had for centuries acted their roles in a drama greater than Shakespeare’s – one that, millennia ago, had been played for real on earth and, for believers, at God’s will for our benefit. Their once miraculously constructed living tableaus and endlessly changing chiaroscuro are now, as Robin Simon has so poignantly described, flattened and left with “a smooth slimy surface with much of the miraculous crispness of the carving and detail lost.”

Even now, it is not too late to save an unmolested portion of this cathedral for future generations who would otherwise never be aware of the loss and adulteration: a petition – and an invitation to comment – beckons at a touch.

Michael Daley, 30 April 2018

CODA:

Today, 30 April 2018, Electronics Weekly reports that the lighting firm Osram has announced it has won a contract to light St. Peter’s in Rome: “‘We won worldwide recognition for the LED lighting system we installed in the Sistine Chapel’, said Osram Licht CEO Olaf Berlien. ‘We are very excited about this new opportunity to demonstrate our skills as a provider of complex, large-scale lighting solutions by conducting the lighting project in St. Peter’s.’” The report does not say how much Osram will be paid to light St. Peter’s (and, thereby, showcase its own products) but it does give further information on the lighting installed in the Sistine Chapel “The aim was to light the paintings so they appear to be lit by sunlight…Researchers went so far as to incorporate the current thinking of historians – that Michelangelo mixed paints in daylight rather than under candlelight or the light of torches, and therefore needed a cooler over-all colour temperature to get the best view of them today”. Michelangelo, of course, painted in the light of the chapel and for the chapel’s then sources of lighting. Indeed, when the ceiling was stripped down with the Moras’ AB57 chemical cocktail, art historian apologists for the garish colours that emerged contended that Michelangelo had had to make his colours so intense in order for his painting to read through the gloom of the chapel. As Professor Kathleen Weil-Garris Brandt of New York University and a Vatican spokesman for the restoration, put it in Apollo in December 1987: “Michelangelo…painted the ceiling in the knowledge that his forms would have to carry in the daylight or in the golden glow of candles and oil lamps. That’s one reason why his [restored] colours are so bright. Now that they are being revealed, the anachronistic spotlights only distort the appearance of the frescoes. In fact, the strong artificial lighting of cleaned areas of the Ceiling originally contributed to the false impression which disturbed critics of the conservation project.” In other words, now that the original colours of Michelangelo had been recovered, the chapel’s strong artificial lighting was surplus to aesthetic requirements. Why, then, was Osram recently invited to create a system of lighting for those (controversially) restoration-intensified colours that mimics the power of direct sunlight? For St Peter’s, Osram have a different agenda: “the lighting will be adjustable to suit different occasions, and will ‘accentuate the properties of the materials used and the building itself, highlighting the plasticity of the structure, its marbles and its architecture.'”