The Louvre Museum’s bizarre charge of “fake information” on the $450 million Salvator Mundi

The Louvre Museum in Paris has attacked one of its own named Leonardo restoration consultants – Jacques Franck – with professional disparagement and an allegation of having conveyed “fake information”.

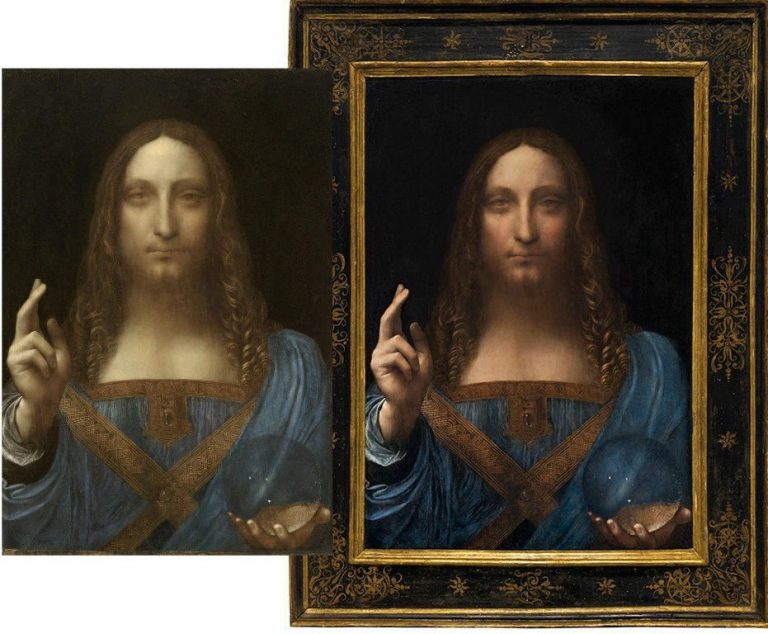

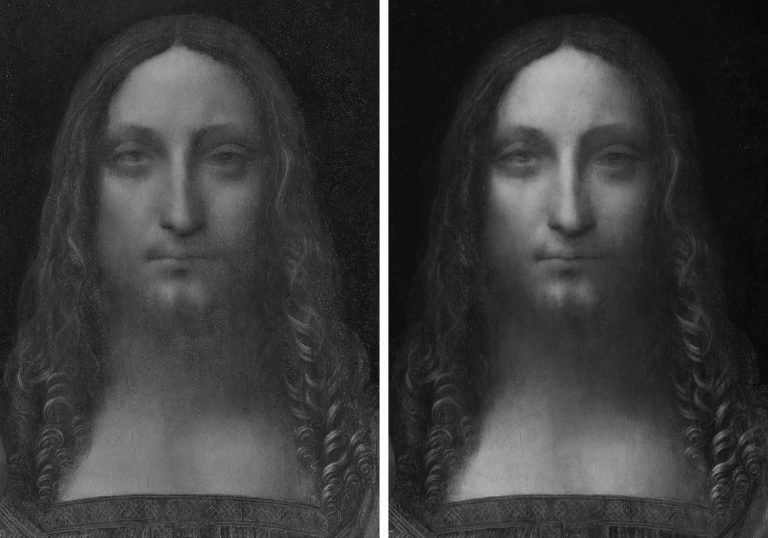

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as when taken in 2005 (still sticky from a recent treatment) to the New York studio of the restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini; right, as when taken in 2008 by one of the consortium of owners, Robert Simon, to the National Gallery in London for a covert viewing by a small group of Leonardo specialists.

Above, Fig 2: Left, the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as exhibited in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition Leonardo da Vinci – Painter at the Court of Milan; right, as seen at the end of Modestini’s restoration programmes in 2017 at Christie’s, New York.

Whenever vicious personal attacks are made by institutions on experts, two things should always be considered: what, precisely, is being said; and, what has been left unsaid. The Louvre’s Trumpian “Fake information” slur on Franck was made by its press officers in response to a report by Dalya Alberge in the Sunday Telegraph (“Paris Louvre ‘will not show’ world’s most expensive painting amid doubts over authenticity”) that the Leonardo painting technique specialist, Jacques Franck, has been told by high level politicians that the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi will not be included in the Paris Louvre’s forthcoming Leonardo exhibition and that Louvre staff “know that the Salvator Mundi is not a Leonardo”.

Jacques Franck’s role as advisor to the Louvre’s Leonardo restorations

In attempts to defuse and refute Franck’s (honest) testimony, the museum’s press officers have also scattered red herrings and sown misinformation. To the Mailonline (“Is the world’s most expensive painting a FAKE?”) they claimed that:

“M. Franck was part of the scholars who have been consulted 7 or 8 years ago for the restoration of the Saint Ann.

“He is not currently working on the Leonardo da Vinci exhibition and has never been curator for the Louvre.

“His opinion is his personal opinion, not the one of the Louvre.”

It should go without saying that when called by the Louvre to give technical advice, Franck’s expert views are his own and not those of the museum – why else would he be being called in? No one had claimed that Franck is a Louvre curator. No one had claimed he is working on the Louvre’s forthcoming Leonardo exhibition. So, contrary to appearances, nothing was being refuted. However, on the extent and frequency of his contributions, it would seem that the Louvre’s officials have misinformed the museum’s spokeswomen who have in consequence scattered seriously misleading accounts around the press.

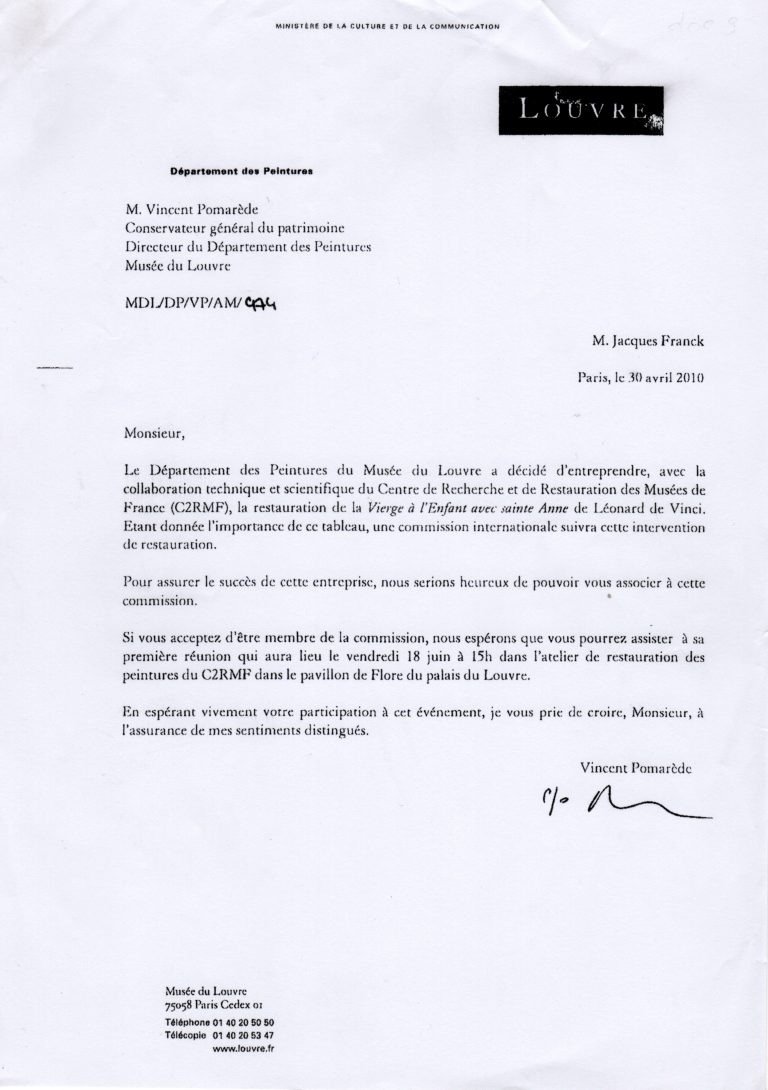

Contrary to their claims to the press, Franck’s association with the Louvre had not ended in 2011-12 after the controversial restoration of Leonardo’s the “Virgin and Child with St Anne” – see Endnote 2 and Figs. 8, 9 and 10. In 2014 his advice was sought by the Louvre when it planned to restore Leonardo’s portrait of the Belle Ferronnière (see Figs. 3 and 4 below). Vincent Pomarède was the Head of Paintings at the time, he had launched the project but before the restoration began he was appointed principal Assistant to the Louvre Museum’s Chairman. He was replaced by Sébastien Allard as Head of Paintings, who became ipso facto, as is the usual custom in the Louvre, the Chair of the scientific advisory committee, while Pomarède retained a prominent role in that committee, partly on account of having promoted the project when Head of Paintings, and also on account of being close to the Louvre’s own Chairman. At this stage he decided that Franck’s contribution was officially that of his special “private adviser” during “all the time that restoration would last”.

Two years later, in 2016, when the cleaning of Leonardo’s Saint John-the-Baptist started, Franck was asked jointly with Ségolène Bergeon Langle, the former head of Conservation in the Louvre (and a legendary figure of the French museums’ restoration), to supply “all remarks and advice” to the then new head of Paintings, Sébastien Allard, on joint visits to see the painting with him in the conservation studio.

The Paris Louvre’s inscrutable position on the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi

The case against Franck, as offered by the Louvre press office on 18 February to the Art Newspaper (“’We want Salvator Mundi’ for Leonardo blockbuster, Louvre says”) rested on two claimed statements of fact: that “the Musée du Louvre has asked for the loan of the Salvator Mundi for its October exhibition and truly wishes to exhibit the artwork”; and, that “the owner has not given his answer yet.”

Those claims are utterly perplexing. As the Art Newspaper noted, the Louvre’s statement suggests that the painting is not, after all, owned by the Louvre Abu Dhabi museum, but by a single individual, widely believed to be Mohammed bin Salman, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia. Can that really be the case? If so, when did the Paris Louvre make a direct request to him to borrow his painting for its big celebratory 2019 Leonardo exhibition? The terse but vague Louvre phrase “has asked” gives no indication of the timing of the request but the Louvre was understood, like the Royal Academy, to have requested such a loan in the immediate aftermath of the Salvator Mundi’s triumphant $450 million sale in November 2017. Was that earlier request renewed, or is it the sole and original request to which the Paris Louvre press office now refers? Either way, the question arises: What grounds has the Crown Prince given to the Paris Louvre museum for withholding his permission to borrow the Salvator Mundi?

Curatorial Dogs that have not barked

Could it be that the Paris Louvre does still wish to include the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi (it would be immensely politically embarrassing for it to exclude the Abu Dhabi Louvre Museum painting from this year’s long-planned Leonardo extravaganza) but is no longer prepared to describe the painting in its own catalogue and literature as it was described first in the National Gallery exhibition of 2011-12 and later by Christie’s at its 2017 sale – namely, as a Salvator Mundi that “was painted by Leonardo da Vinci [and that] is the single original painting from which the many copies and student versions depend”? If, however, as today’s press officers imply but do not expressly state, the curators and the director of the Louvre really do presently consider the Abu Dhabi painting to be precisely as described in Christie’s’ sale literature, why was no one with curatorial authority at the museum prepared to make that claim publicly and within the official response to Franck’s cited contrary testimony? For that matter, has any Paris Louvre curator ever supported the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo ascription in written scholarly form?

At the same time, is it not also possible that the Salvator Mundi’s individual owner or the Louvre Abu Dhabi museum – whichever presently pertains – will not accede to a loan request on anything less than an assurance from the Paris Louvre that, if included in the major Leonardo anniversary exhibition, it will be categorised as an entirely and unquestionably secure autograph Leonardo prototype painting? If such possibilities are not the case, what exactly has been the cause of the fifteen month-long stand-off between Paris and Abu Dhabi and the cause of the latter’s failure to exhibit the painting – or, even, to disclose its whereabouts? As for the present ownership, after the work was auctioned in November 2017, Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism released a statement saying it had acquired the work for the new Louvre Abu Dhabi museum.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi’s undisclosed whereabouts

The Abu Dhabi museum was scheduled to launch the Salvator Mundi last September but it cancelled its own event with no explanation. It had been widely expected that the Louvre Abu Dhabi would announce plans to exhibit its Salvator Mundi on the 10 February 2018 official visit of the French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe, who toured the Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum on Saadiy island in the Emirati capital, specifically to launch the French-Emirati “Year of Cultural Dialogue” in the company of Shiekh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, CEO of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. But once again, the world’s most expensive painting made a no-show on a no-explanation: the Minister and the CEO both declined to answer any questions about the unexplained decision not to exhibit the painting in Abu Dhabi. (See “A day in the life of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s pricey new Leonardo Salvator Mundi ” and Fig. 5 below.)

Above, Fig. 5: The French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe (centre) poses with Shiekh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (right), CEO of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, during inauguration of BNP paribas Abu Dhabi Global market Branch on February 10, 2018, as photographed by Karim Sahib for AFP and featured in Art Daily’s “The Best Photos of the Day” on February 11, 2018.

Whatever the problem was on those two earlier occasions, it is clear on the Paris Louvre’s press office’s latest statements that that blockage remains in place – just as the whereabouts of the painting itself remain undisclosed fifteen months after the painting was sold for a world record price. The essential question therefore remains outstanding: Why will the Abu Dhabi Louvre museum neither exhibit its own Salvator Mundi painting nor agree to lend it to the Paris Mother-Museum? In truth, the issue here is not one of fake information by critics of the attribution, but of a bizarre combined refusal by two museums and/or a prince to explain their own repeatedly aborted-actions and prolonged failures to reach an agreement or disclose information.

If Franck’s sources are correct in claiming that the Paris Louvre Museum has lost confidence in the Salvator Mundi as an autograph Leonardo, then an explanation for the present perplexing state of affairs offers itself: there exists today a perfect state of mutual paralysis as the Louvre wishes to avoid an international, inter-governmental embarrassment by including the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi painting but not as an accredited autograph work; while the owner(s) will gladly lend it but not as an attributed work of Leonardo’s studio.

The present manifest disinclination of the Louvre’s own officers and curators to make any personal declaration of confidence in this Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo attribution is encountered also among almost all of the painting’s original dozen or so Christie’s-cited supporters. If, as the Paris Louvre’s press officers claim, the Abu Dhabi painting really does retain the confidence of both the museum’s own curatorial staff and the dozen or so scholars identified as supporters by Christie’s ahead of the sale, as an autograph work of Leonardo, they would all seem to share a funny way of not-showing it. As things stand, and as we were reported as saying in the 17 February Sunday Telegraph, “What we now have is effectively an un-dead painting – no one believes in it; no one will say where it is; no one can lay it to rest.”

Endnote 1:

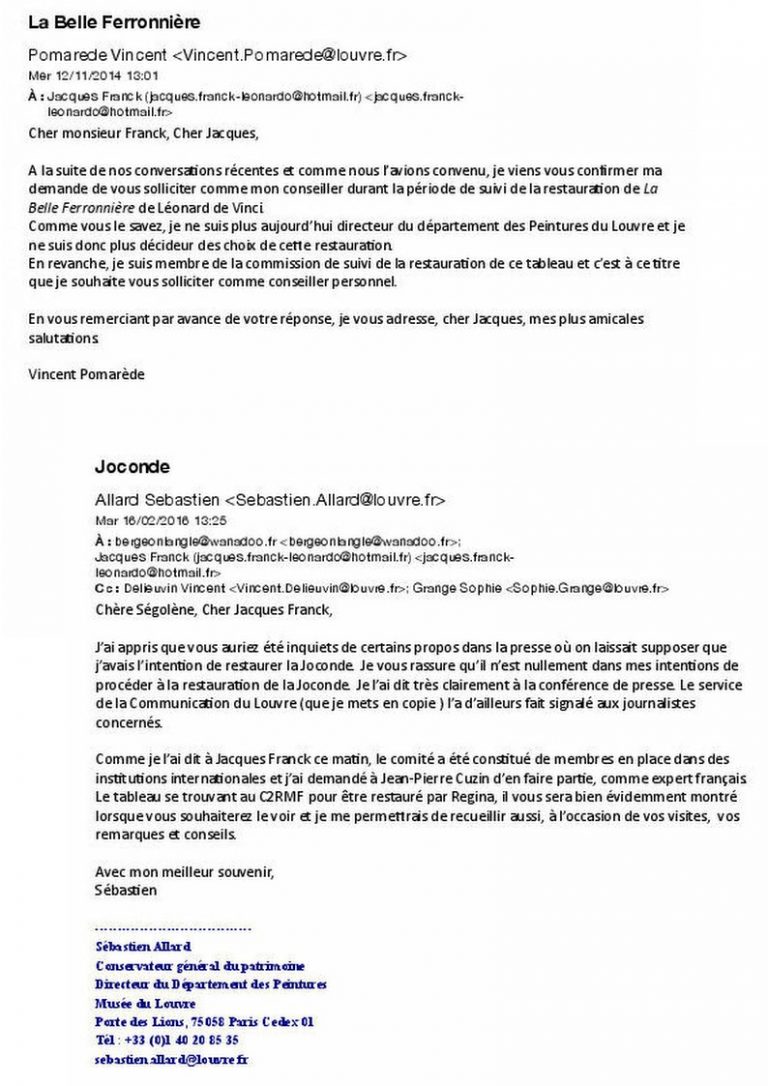

Experience shows that on matters of art restoration Louvre press office claims are sometimes best taken with a pinch of salt. In 2010 we carried a report of a covert second repainting at the Louvre of a face in a Veronese painting – see “A spectacular restoration own-goal: undoing, re-doing and (on the quiet) re-re-doing a Veronese masterpiece at the Louvre Museum.”

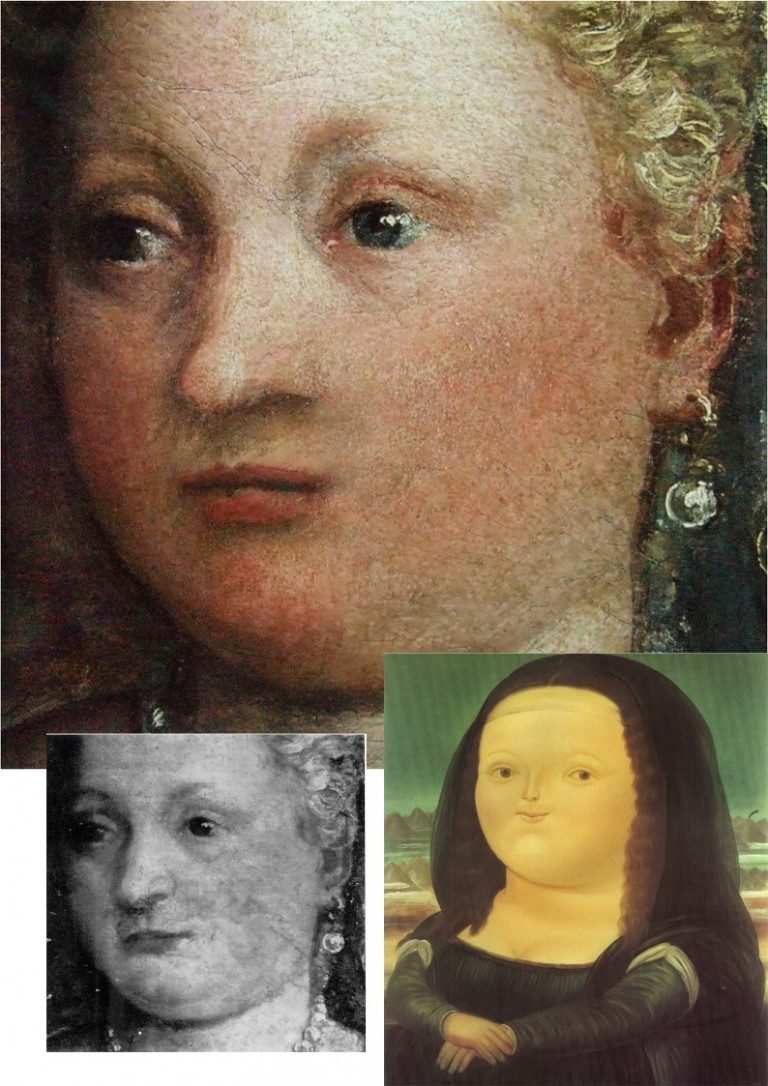

Above, Figs. 6 and 7: However good their intentions, however avowedly “ethical” their professional codes, restorers, like forgers (who are often themselves restorers or ex-restorers), cannot avoid leaving personal imprints and those of their cultural milieus in their repainting. The more ambitious the aspirant, the more deficiencies of artistic reading and anatomical understanding can be imposed on mute works of art. The Louvre Veronese restorer above seemed in thrall to the pneumatic forms and miniaturised features of Botero. That such eccentric aesthetic predilections should ever have been institutionally authorised would augur badly for the Mona Lisa herself in a Louvre Museum today where the curators are bingeing on radical restorations as they play catch-up with the technological adventurism long-encountered in British and American museums.

In June 2010 when the arts journalist Dalya Alberge asked for explanations of this second covert and unrecorded repainting of the Veronese face, the Louvre press officer stated that the restoration had consisted of the painting being merely “scrubbed up” (“bichonnée” – a term normally used for very light interventions such as dusting or retouching a minor scratch unnoticed in the museum etc). That the museum’s official description bore little connection with the pictorial truth of the situation can be seen at glance above at Figs. 6 and 7 and here:

“Louvre masterpiece by Veronese ‘mutilated’ by botched nose jobs”.

Endnote 2:

On the Paris Louvre’s controversial restoration of Leonardo’s the “Virgin and Child with St Anne”, see:

“The Louvre Leonardo Restoration Committee Resignations”;

“What Price a Smile? The Louvre Leonardo Mouths that are Now at Risk”;

“Another Restored Leonardo, Another Sponsored Celebration – Ferragamo at the Louvre…”;

“Rocking the Louvre: the Bergeon Langle Disclosures on a Leonardo da Vinci restoration”.

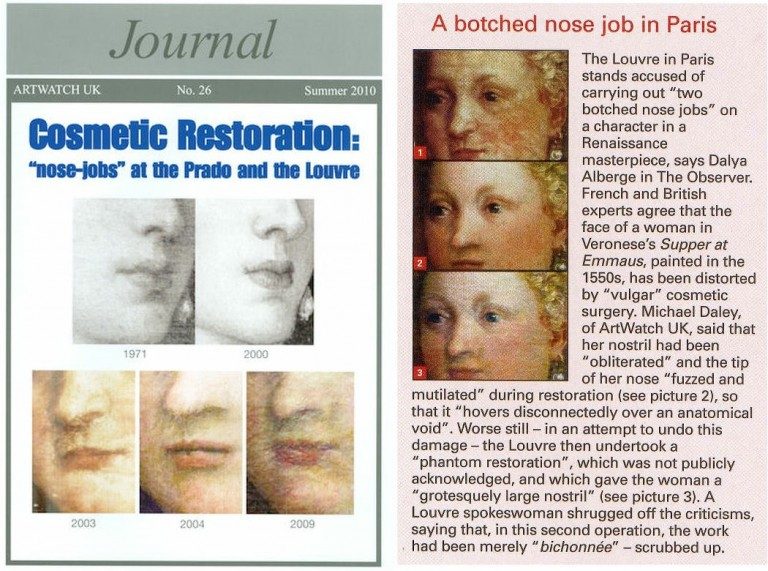

Above, Figs. 8, 9 and 10: Top and centre, a detail of the Louvre’s “Virgin and Child with St Anne”, before restoration, left; after restoration, right. Above a detail of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi, as exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011, left, as sold at Christie’s in 2017.

In the above three sequences we can see the principal twin consequences of “restoration” procedures: with a bona fide Leonardo masterpiece (top and centre) values are diminished and degraded. With a not-Leonardo, above, we see attempts to move a painting further towards a modern conception of what bona fide Leonardos look like. The outcomes – degradation or falsification – can occur on the same work. There are more restorers than ever before in history and they are ceaselessly working and re-working a finite pool of old master paintings which resemble themselves less and less. Pontormos and Giorgiones alike increasing resemble coloured drawings.

Michael Daley, Director, 22 February 2019

Leave a Reply