The Louvre’s Leonardo Restorations: The Tide Turns

Recent newspaper criticisms of the Louvre’s controversial restoration of Leonardo da Vinci’s near-monochrome painting of St. John the Baptist continue in the scholarly press.

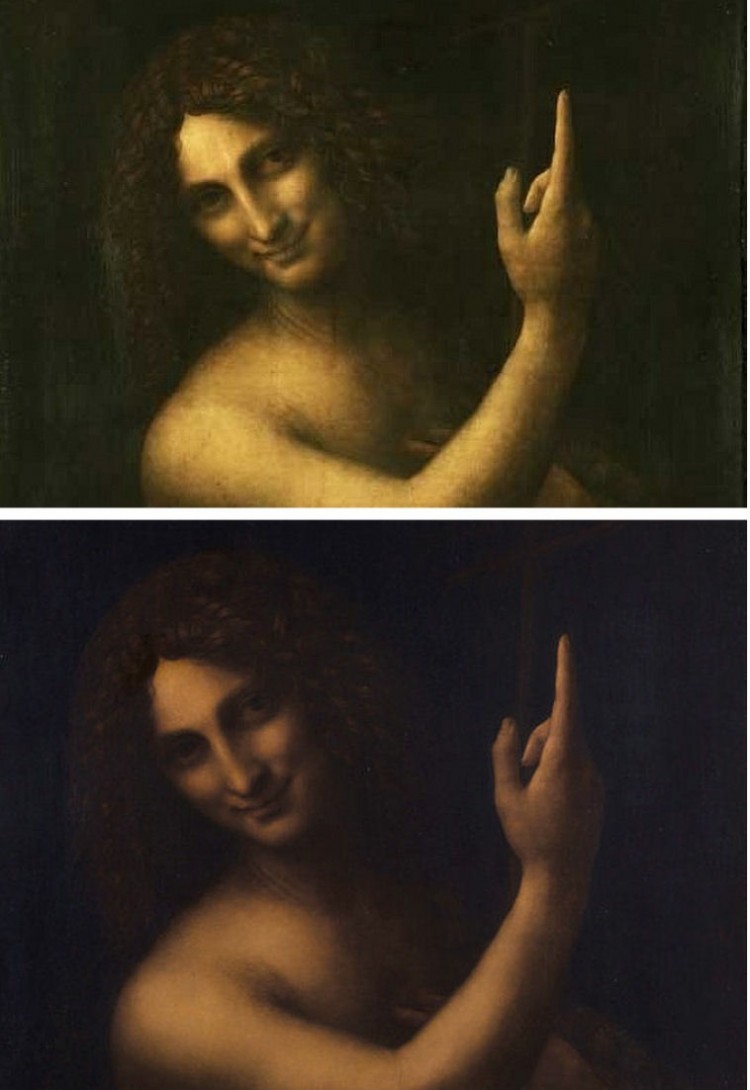

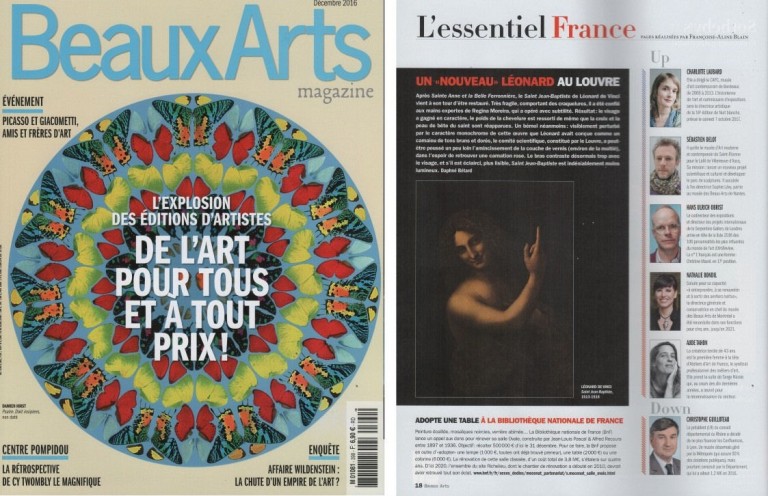

Above, Figs. 1 and 2: Leonardo’s St John the Baptist, top, before restoration; and, above, after restoration. In some publications, the order of the before and after restorations was transposed and experts expressed preferences for the supposed after restoration state when in truth it was the before restoration record. The reason for that mis-judgement becomes clear when the photographs are shown in the right order: before restoration the painting showed a greater range of values and had a markedly more vivacious appearance. Below, Fig. 3, the December 2016 issue of Beaux-Arts magazine.

In the December 2016 issue of Beaux-Arts, France’s leading magazine of the visual arts, under the heading “New” Leonardo in the Louvre, Daphné Bétard reports:

“Following the St Anne and Belle Ferronière, Leonardo’s Saint John-the-Baptist has just been restored. It is a very fragile picture, bearing much crazing. Regina Moreira, a skilled restorer, has been trusted with its cleaning and she has done a subtle job. As a result, the Saint’s face’s character is better defined while the heavy hair, the cross and the animal fur come out better. Some toning down, however: the scientific advisory committee hired by the Louvre has obviously been overtaken by this monotone brown-gold composition as Leonardo definitely wished it to be. As a result, the Louvre seems to have over-thinned the varnish (now half thick) hoping to retrieve unlikely fresh pink flesh tones. The Saint’s lighted arm now contrasts too strongly with the face. While Saint John-the-Baptist has become more legible, doubtless that it is far less radiant.”

Above, Figs. 3, 4 and 5: top, Daphné Bétard’s report; centre, the head of St. Anne in Leonardo’s The Virgin and Child with St. Anne , before restoration; above, the head of St. Anne in Leonardo’s The Virgin and Child with St. Anne , as seen after restoration.

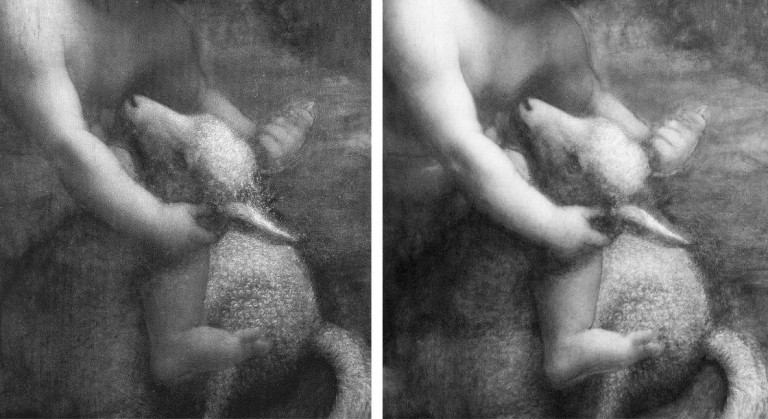

Earlier, the press reported on a number of occasions that during restoration a certain disruption had occurred between St. John’s beautifully, softly modelled face and his (proper right arm). For Eric Bietry-Rivierre in Le Figaro (5-6 November 2016), “the face and the arm are now unbalanced in terms of degree of modelling.” In La Croix online (10 November 2016), Sabine Gignoux judged that “the Precursor’s uplifted arm had acquired during cleaning a rather rigid outline along its lighted section”. Precisely such injuries to Leonardo’s uniquely subtle and refined modelling had occurred during the restoration of his “The Virgin and Child with St. Anne” – as seen above and below. Such judgements on the St. John restoration have been widely taken as vindications of warnings reported in the Wall Street Journal by Jacques Franck, a Paris-based Leonardo expert consultant to the Louvre. When the cleaning was about to start, the WSJ reported (16 January 2016) Mr Franck’s observation that: “I don’t oppose the removal of the latest layers of varnish, but am concerned they may go too far and touch original material, which could be vulnerable to the solvents used in the process for [contrary to the general belief] the aesthetics of the image were meant to be blurry and dark”.

Below, Figs. 6, 7 and 8, showing, top, a greyscale detail of the The Virgin and Child with St. Anne before cleaning, left, and after cleaning, right. The same detail is shown, centre, before cleaning, and, bottom, after cleaning.

Against such technically and aesthetically informed concerns, the Wall Street Journal, also quoted the insistence by the museum’s Head of Paintings, Sébastien Allard, that “Louvre officials say that such concerns are unwarranted because restoration techniques have evolved in recent decades to the point the process is considered safe” and that, besides, “the doctrine at the department is prudence and pragmatism”. Every generation of restorers repeats this claim of a final achievement of safety-in-restoration. While such are the stock currency of defensive museum officials the world over whenever challenged on restorations, in this case, given the manifestly injurious earlier Louvre restoration (2012) of another Leonardo masterpiece, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and a Lamb, as shown here, they might be thought to smack of complacency if not defiance. Such was the strength of opposition to the over-cleaning of the picture that two leading Louvre in-house curators resigned from the advisory scientific committee in protest.

For our own coverage of that controversy, see: The Louvre Leonardo Restoration Committee Resignations; What Price a Smile? The Louvre Leonardo Mouths that are Now at Risk; Another Restored Leonardo, Another Sponsored Celebration – Ferragamo at the Louvre ; and, Rocking the Louvre: the Bergeon Langle Disclosures on a Leonardo da Vinci restoration.

Mr Franck now wonders whether, before next listing the Mona Lisa for a face-lift, the authorities will consider whether the Louvre’s present Leonardo cleaners’ claims of “prudence and pragmatism are really reliable or mere imagination”. Her smile, he asks, “is what is now at stake, isn’t it?”

Above, Fig, 9, a detail of the Mona Lisa’s ineffably subtle, heavily crazed mouth.

Michael Daley, 29 November 2016

Leave a Reply