Holbein’s Anne Boleyns and the “Discovery” Trope

Art is made by artists to order, or for the market, or from personal compulsions. Thereafter its standing is determined by others – primarily scholars, curators, auctioneers, and dealers – who confirm or reject the authenticity of works and the identities of sitters within them. Such judgements are often presented not as expert, professional opinions on which scholarly discussions might proceed, but as discovered truths. Discoveries can be well-founded or spurious. In art restoration, where claimed “discoveries” so often mask bungled interventions, the proof of the pudding is in the looking (at comparative photo-records) and it should be considered so, too, with claimed art historical discoveries.

A CASE IN POINT: TWO HOLBEIN ANNE BOLEYN ASCRIPTIONS

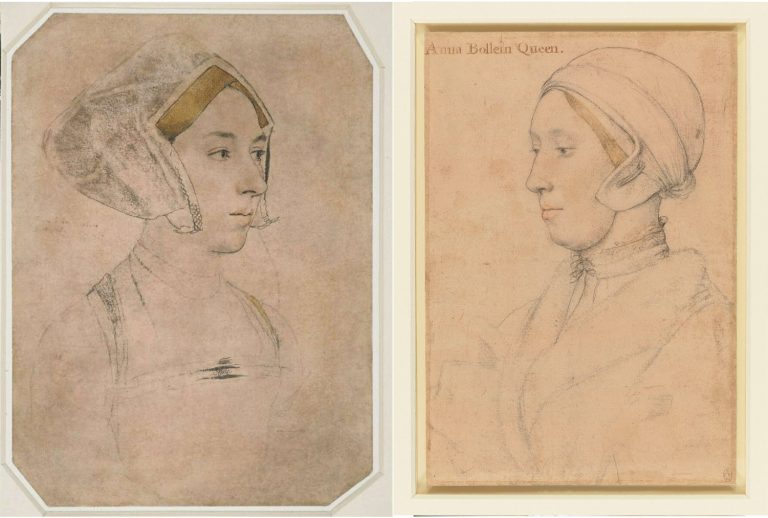

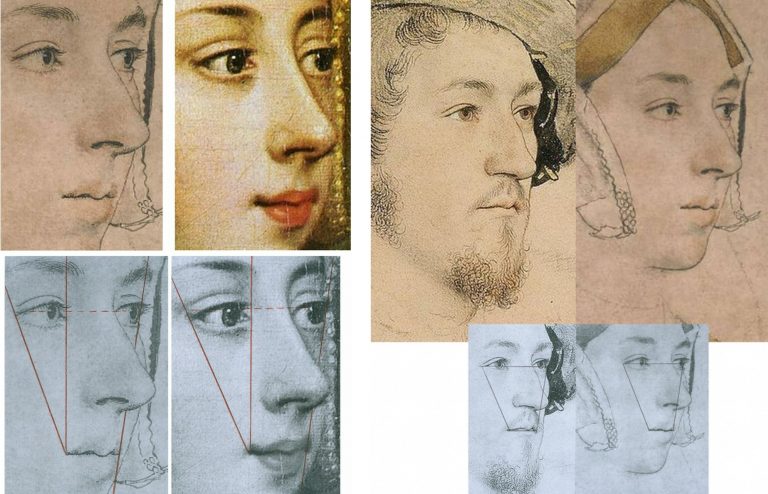

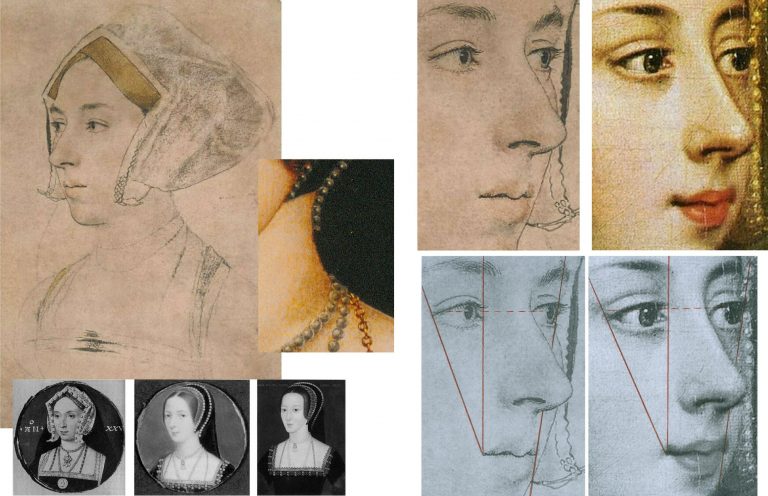

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the British Museum (formerly “Bradford”) Anne Boleyn-inscribed Holbein drawing; right, the Royal Collection Anne Boleyn-inscribed Holbein drawing.

Both of the above English Holbein portrait drawings are securely provenanced – both entered the Royal Collection on Holbein’s death. Both bear inscriptions identifying the portrayed sitter as Anne Boleyn. One or other of the drawings might be of Anne Boleyn but both cannot be so because, as all parties are agreed, the drawings depict two different people. In this case both sitters had been identified by the same respectable near-contemporary witness, Sir John Cheke, but for almost five centuries everyone had taken the (now) British Museum drawing to be the true record of Anne’s likeness. In the last half-century an overlapping succession of three people (an art historian, a Tudor historian and a modern historian) laboured for three decades to reverse that traditional identification. They all did so without offering a direct photo-comparison of the two drawings at issue. Effectively, this campaign was an anomalous images-light war of words.

We take the eventual success of that campaign as a prime case of a visually unsupported and spuriously claimed discovery, notwithstanding its seeming vindication in 2007 when the Royal Collection held that its Anne Boleyn-inscribed Holbein drawing bears the ill-fated queen’s likeness. Four years later that dramatic reversal was recalled/celebrated by Bendor Grosvenor in a 15 December 2011 Art History News post “Anne Boleyn regains her head”:

“This isn’t ‘news’ as such, but in a foray into the Tudor realms of Twitter last night I mentioned the drawing of Anne Boleyn by Holbein in the Royal Collection. I said that although in the past the identity was doubted by art historians, the sitter was now catalogued with certainty as ‘Anne Boleyn’, as you can see on the Royal Collection website…”

That claimed certainty of identification had rested on a three-stage campaign that ran between 1977 and 2007 and to which Grosvenor had contributed last. It proceeded as follows.

STAGE I: A REVISIONIST CHALLENGE

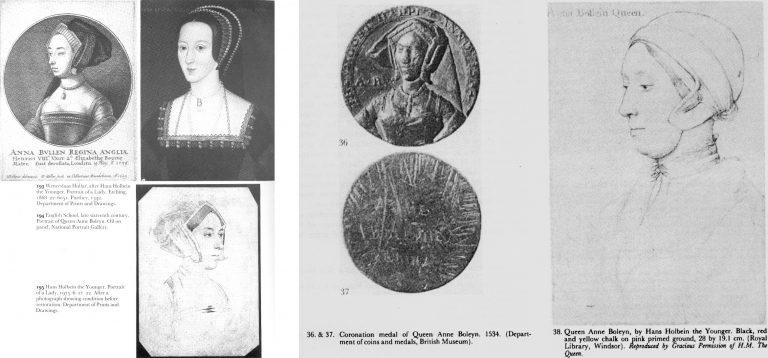

In 1977 John Rowlands, the deputy keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum, challenged the traditional identification of Anne in the museum’s newly acquired landmark Holbein Anne Boleyn drawing. He did so in a commemorative article (“A portrait drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger”) carried in the British Museum YEARBOOK No. 2. The challenge rested on an objection that the drawing’s documentary records began in the 17th century (- see Part I: Sex, Trigonometry and Anne Boleyn’s Recovered Likeness.) Rowlands’ article carried just three photographs (Fig. 2, below) with none showing the Windsor Royal Library drawing being proposed as the true Anne Boleyn Likeness.

STAGE II: THE 1983 ROWLANDS/STARKEY COLLABORATION

Six years later, Rowlands co-authored an article with the Tudor historian David Starkey in the February 1983 Burlington Magazine (“An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein’s Portrait of Anne Boleyn”). Dr Starkey had scored a Bull’s Eye in a 1981 Burlington Magazine article (“Holbein’s Irish Sitter?”) by identifying a more plausible sitter in a Royal Collection Holbein drawing given to “Ormond”. As Jane Roberts put it in her 1993 National Galleries of Scotland Holbein and the Court of Henry VIII catalogue:

“The old identifying inscription, ‘Ormond’, has led to some confusion concerning the subject of this drawing. There were for a time two rival claimants to the Earldom of Ormond (or Ormonde): Thomas Boleyn (1477-1539) and James Butler (c. 1504-46). The former, the father of Anne Boleyn, was considered the most obvious candidate, although it was remarked that the drawing appeared to show someone younger than fifty (Thomas Boleyn’s age at the time of Holbein’s first visit to England.) David Starkey has plausibly suggested that the drawing instead represents James Butler, son of Piers Butler, the illegitimate kinsman of the 7th Earl of Ormond (died 1515) and claimant to his title and lands…”

As with Rowlands, Rowlands/Starkey gained no official acceptance. Recognition would only be obtained in 2007 when Starkey joined forces with the Philip Mould Gallery in an “identity discoveries” fest, some thirty years after Rowlands’ initial challenge (see below). Where Starkey’s independent professional historical elucidation of Ormond familial relationships had proved valuable to art historians, on his 1983 pairing with Rowlands he became a partisan/advocate to a historically unsupported and visually unexamined ascription. On this turkey of a case, Starkey’s professional juju failed.

Offering no visual argument, Rowlands/Starkey effectively attempted a verbal sleight of hand on a non sequitur by holding that because Sir John Cheke (the source of the English Holbein portrait drawings’ sitters identifications) might have been better placed to validate an Anne Boleyn inscription than had previously been appreciated, the Windsor drawing’s sitter therefore was the true Anne Boleyn likeness. Thus, the logical flaw of Rowlands’ initial 1977 essay remained: the more well-placed Cheke becomes as an identifier of sitters, the more reliable he becomes as the man who had also identified the sitter in the British Museum’s Anne Boleyn-ascribed Holbein drawing.

NO BEEF

The authors tacitly acknowledged the absence of corroborating evidence for the Windsor drawing’s sitter by contending that “In view of all the evidence accumulated here it seems likely at the least that Holbein was taken up by the Queen as well”. (Emphases added.) Even if such a relationship been established, it could not in itself have weighed in favour of one rival Anne Boleyn inscribed drawing over the other, for reasons given – but it had not been so established: a “likely” is not a “was” – and nor is a “likely was”. In an article cumulatively held together by a “could have”; a “would have”; a “must have”; a “could well have”; a “could have taken”; a “had every reason to take”; a “most likely”; and, a “we would guess,” the authors’ peroration itself comprised a further mini daisy-chain of question-begging speculations (emphases added):

“…his appointment as the King’s painter probably antedates it. And the likely responsibility rests with Anne Boleyn herself. For it may not be a coincidence that Holbein’s advancement at court… appears to have progressed largely through the favour of adherents to religious reform…”

That lame ending had followed a weak opening. The existence of the two rival Holbein Anne Boleyn drawings was acknowledged, as was the fact that they “clearly show different sitters”, but the drawings were not shown together side-by-side so as to permit a direct visual comparison – the authors’ claims had to be taken on trust. Similarly, it was claimed on no cited evidence that because Rowlands’ 1977 identification had “apparently” been “generally accepted” the case for the possible authenticity of the Windsor Anne Boleyn inscribed drawing “must be re-opened”.

ABSENCES OF EVIDENCE

Had Rowlands’ 1977 case been accepted, there would have been no cause to reopen it in 1983. Whether Rowlands’ original claims had been partly/largely accepted or not, the features on the two Anne Boleyn-ascribed drawings remained physically incompatible (see Figs. 1 & 3). Only one, therefore, might be a true likeness. Rowlands/Starkey conceded further absences of evidence for their position by (wrongly) claiming that no visually comparative means of adjudicating between the rival likenesses existed: “For such a re-examination there is no available visual evidence”. That assertion was made on the grounds that the only secure contemporary image of Anne is that on the damaged coronation medal of 1534. The damage on the medal is local and by no means robs the image of all testimonial capacity. When the authors published the medal and the Windsor drawing side-by-side, they claimed (rightly) that no correspondences exist between those two works, when, as can be seen at Fig. 2 below, there are clear correspondences with the British Museum drawing, the etched copy of it by Wenceslaus Hollar, and the National Portrait Gallery painting of Anne Boleyn.

Above, Fig. 2: Left, the three illustrations carried in Rowlands’ 1977 British Museum Year-Book II article “A portrait drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger”; right, the two illustrations carried in the Rowlands/Starkey February 1983 Burlington Magazine article “An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein’s Portrait of Anne Boleyn”.

As if aware that their “evidential” cupboard was bare, the authors continued “fortunately… there are other pointers”.

AN UNFORCED ERROR

The first Rowlands/Starkey “pointer” was that the sitter in the Windsor drawing shows, like Henry’s other queens, little signs of prettiness – “and certainly nothing to compare with the ‘Bradford’ lady’s charm, which could well explain why in the seventeenth century the latter was claimed to be the bewitching Queen”. By alleging a supposedly misleading power of influence to Anne’s appearance in the British Museum drawing, the authors tacitly conceded that it – and not the Windsor drawing – had for five centuries been taken as the true likeness and that it had informed the subsequent late sixteenth century Anne Boleyn paintings (see Figs. 10-13.) No iconographic legacy of any sort attaches to the Windsor “Anne”.

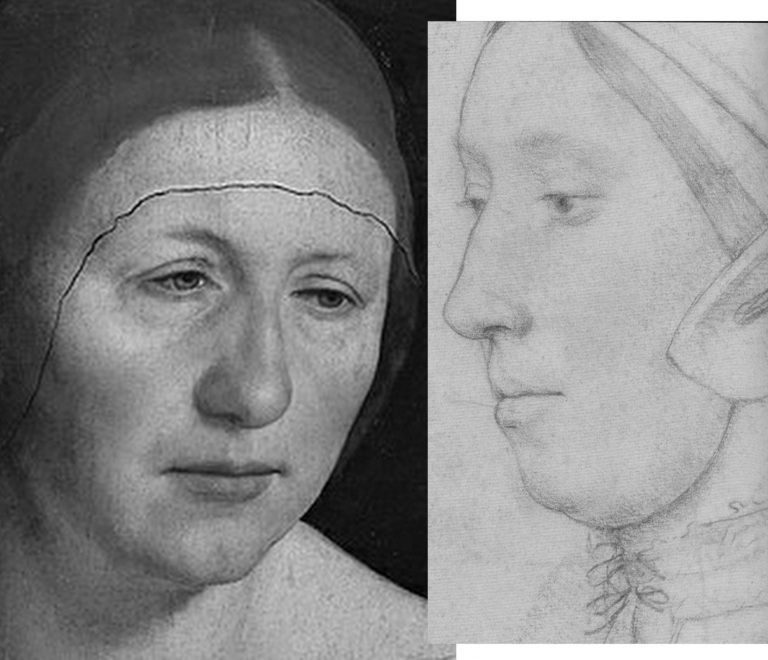

Against their own acknowledgement of the British Museum drawing’s historically influential artistic potency, the authors offered a subjective counterclaim that the Windsor portrait had given true expression to the “strong will and intelligence [of Anne Boleyn] that her contemporaries noted”. As shown above, below, and previously, the sleepy-eyed, older, fleshier, fair-haired not dark-haired sitter in the Windsor drawing does not look more charismatically strong-willed and intelligent than the British Museum drawing’s sitter. Had the authors’ estimation of the relative traits in the rival drawings been sound it would have helped their cause to demonstrate the relationship by showing the two likenesses together, as here below.

A PHOTO-COMPARISON THAT DID NOT SHOW ITS FACE

Above Fig. 3: Details of the British Museum Holbein Anne Boleyn-ascribed drawing, left, and, right, the Royal Collection Holbein Anne Boleyn-ascribed drawing.

POINTERS AND CONCRETE INDICATIONS

Evidently still fearful of the manifest weaknesses in their case and notwithstanding their own “pointers”, the authors cited certain “more concrete indications” of Anne Boleyn’s “appearance and dress”. These supposed concretely reliable indications were hearsay comments made in an acknowledged “anonymous and scurrilous French account” of Anne’s grandly ceremonial entry into London the day before her coronation. That is, Rowlands/Starkey presented as if concrete and corroborating evidence, the account of an unknown, manifestly malicious source who had described Anne as “scrofulous” (suffering from a form of tuberculosis and glandular swelling) and of having worn her dress fastened up very high on her throat to conceal a goitre. Thus, from Rowlands/Starkey: “In the [Windsor] drawing her double chin is so pronounced, as to suggest such a swelling of the throat glands, which is indeed partly hidden by a high neckline.”

There were so many problems with acceptance of that malicious account. First, the reported, supposedly goitre-concealing, garment worn by Anne was not her customary dress but what the Tudor historian Eric Ives described as “the traditional high-necked English coronation mantle”. Second, the Windsor drawing’s sitter was not wearing any form of day wear: “She wears some kind of under-cap and a furred nightgown over her chemise”. Third, the tied neck of the chemise did not conceal the double chin – only a very high turtle-necked garment might have done so. Fourth, the displaying of such “undress” for a likeness-recording artist, was held to constitute proof of regal identity because: “only a woman of the highest rank could have taken such a liberty in court circles.” Begging their own question, the authors added: “Several of Holbein’s male sitters appear in similar states of undress but Anne was the only woman to do so.” In this instance, a “could have” became a “was” in two breaths, with a seeming wish once again being the father of the deed.

Had Holbein drawn Henry’s second queen in such a state of undress, he would have put himself at risk of accompanying her and her alleged lovers to the executions. Had the fair-haired Windsor sitter been the mother of Holbein’s two English children, no suspicion of impropriety could have arisen. As it happens, downcast eyes and wistful expressions are common to the Windsor drawing and Holbein’s German wife, as depicted in his The Artist’s Wife and Children – detail below, left. (Also, as discussed below, the Windsor sitter bears certain facial similarities with another contested Holbein sitter in the Royal Collection.)

Above, Fig. 4: Left, detail, Holbein’s The Artist’s Wife and Children; right, a detail of the Royal Collection “Anne Boleyn” drawing.

THREE NOSTRILS AND TWO TRAPEZOIDS

While nothing is known of the mother of Holbein’s two English children, Anne Boleyn famously had a brother, George, three or four years her junior, and with whom she was alleged to have committed adultery. No Holbein drawing in the Royal Collection is identified as George, but as luck would have it, one of Holbein’s unidentified portraits in the collection happens to have been made from a closely similar viewpoint to that of the British Museum Anne. As shown below, an unmissably similar configuration of brows, eyes, and nose is present in the two drawings. The only significant difference in the features is the appreciably more masculine jaw in the – here proposed – George Boleyn likeness. Unlike the Windsor sitter’s nose, those of George and Anne both have deep nostril apertures.

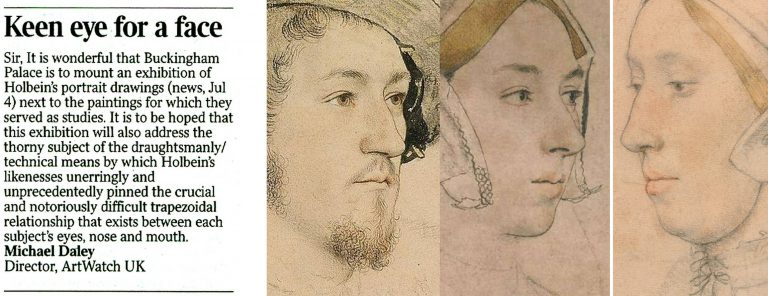

Above, Fig. 5. From left to right: ArtWatch UK letter, the Times, 5 July 2023; an unidentified Royal Collection Holbein drawing which we take to be of George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford; the British Museum “Ann Boleyn”; the Royal Collection “Ann Boleyn”.

HOLBEIN’S “UNIDENTIFIED MAN”

The above Holbein male portrait is today described by the Royal Collection as “An unidentified man, c. 1532-43”. Sir Karl Parker, author of the seminal 1945 Holbein’s Drawings at Windsor Castle, described it as “A Gentleman: Unknown”. Given the many facial similarities in the two drawings we can, perhaps, take it that Sir John Cheke had either not known Anne’s brother or had failed to recall him.

Above, Fig. 6: Left, the proposed Holbein portrayal of George Boleyn; right, the five centuries long accepted British Museum Holbein drawing of Anne Boleyn. Does this “George” not seem a little younger – and perhaps sweeter – than this Anne Boleyn? For that matter, has Holbein ever drawn eyes that are more vividly alive and penetrating than those found in this Anne?

Above, Fig. 7: Left, the similarities between the British Museum Anne and a later painting, as shown in Part I; right, the similarities between the Windsor “George” and the British Museum Anne.

STAGE THREE: A CASE NOT MADE

As with Rowlands, so Rowlands/Starkey had failed to effect a switch of the sitters’ identities. It would take twenty-four more years for victory to be claimed. On 14 March 2007 the Daily Mail (“Finally historians can give Anne Boleyn her head back”) reported:

“A Holbein drawing has been revealed as the only portrait of Henry VIII’s second wife Anne Boleyn. The c.1530 picture carries Anne’s name but other evidence suggested this was an error. Now expert Bendor Grosvenor and historian David Starkey have traced the inscription to her contemporary Sir John Cheke, confirming she is indeed the subject.”

No evidence had been presented by Starkey/Grosvenor that Cheke had specifically and exclusively ascribed the Windsor drawing – or that he had not also so ascribed the British Museum drawing. On the reported claims to have “traced” the Windsor drawing’s identification to Cheke, see below. Nothing had been found and nothing had changed – except, that is, the 1983 Rowlands/Starkey Burlington Magazine thesis had been robustly challenged and rejected in 1986 by a major Tudor historian, Eric Ives, in his biography Anne Boleyn, which work was frequently reprinted until 1994 and later superseded in Ives’ highly acclaimed 2004 The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn ‘The Most Happy.’ Starkey, author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII and Elizabeth, had generously described Ives’ biography as “The best full-length life of Anne Boleyn and a monument to investigative scholarship”.

THE IVES INTERREGNUM

Prof. Ives’ challenge to Rowlands/Starkey in his books had also been developed separately in a major article for the July 1994 Apollo magazine “The Queen and the Painters – Anne Boleyn, Holbein and the Tudor Royal portraits”. Where Starkey/Rowlands had taken two and a half Burlington pages, which included just two photographs, Ives’ essay ran over ten pages and carried sixteen photographs. Although not all pages addressed the Holbein Anne Boleyn drawings, Ives’ substantial scholarly and visually supported account seemed to have trumped Rowlands/Starkey and put the lid on the Windsor sitter campaign. So far as we know, Starkey never added to his joint 1983 Burlington article contribution. When Rowlands returned to the Windsor drawing in 1988 on publishing the British Museum portrait (which was then described as “Portrait of a Lady, thought to be Anne Boleyn”) in his catalogue to the museum’s “The Age of Durer and Holbein” exhibition, he claimed no more against the British Museum Anne Boleyn drawing’s ascription than that the “circumstantial grounds in favour of the Windsor drawing are really very compelling, and one cannot necessarily cast aside Sir John Cheke’s authority for the identification merely because of the confusion over a sitter in the Windsor series being called by him in error ‘Mother Iak’”.

Ives had indeed challenged Cheke’s reliability, and Rowlands acknowledged that his own (somewhat defensive) stance had followed the publication of Ives’ 1986 Anne Boleyn biography:

“Its rejection by Ives in his brilliant historical study is based on a mistaken disregard of the widely varying value of the different supposed likenesses of the Queen; for it is not wise to rely too readily on inferior Elizabethan portraits to form a basis for establishing her appearance.”

Thus, in another attempt to bolster Cheke’s reliability, Rowlands again discounted the testimonies of the many later painted portraits of Anne, none of which, as mentioned, showed any indebtedness to or affinities with the Windsor drawing. As shown in Part I and below, the markedly contrasting degrees of connectedness of the two Anne Boleyn-ascribed Holbein drawings to the many subsequent portraits of the queen constitute the art critical nub of this dispute: How and why had the British Museum Anne – and not the Windsor Anne – come to be held the true likeness for five centuries? To be clear: the contrary case presented for the Windsor Anne rested on nothing more than a) an assertion of near-infallibility in Cheke’s identifications; and b) a systematic disparagement of the visual testimony found in the (near-forty?) subsequent surviving late sixteenth century painted portraits of Anne. Nonetheless, where Rowlands, and Rowlands/Starkey had failed in 1977 and 1983 respectively, Starkey plus Team Philip Mould Ltd would seemingly prevail in 2007. It happened as follows.

TURNING ART MARKET STORIES TO COMPETE WITH SEX SCANDALS AND WARS

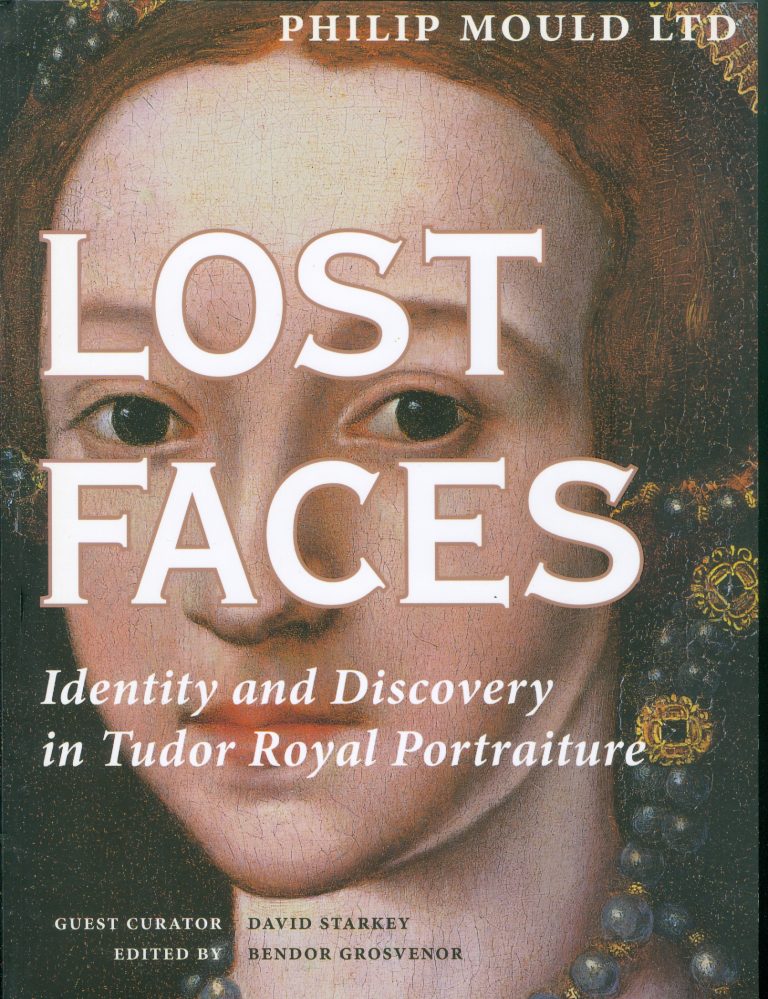

Above, Fig. 8: The catalogue to the 2007 Philip Mould Ltd “Lost Faces – Identity & Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture” exhibition.

The Philip Mould catalogue’s editor, Dr Bendor Grosvenor, set out the contributors’ aims:

“This exhibition seeks to raise questions, stimulate debate, and, where appropriate, suggest answers. Its purpose is intentionally provocative. The authors are indebted to those who have researched and published in the field of Tudor portraiture before. We hope that in bringing fresh eyes to bear on the subject we do not offend, merely illuminate further this fascinating subject.”

ADDING COMMERCIAL VALUE AND ACADEMIC RESPECTABILITY

The commercial and historical importances of attaching faces to historical figures was set out frankly and with passion, respectively, by Philip Mould and David Starkey. Mould began in the Foreword:

“When, early last year, David Starkey mentioned he would like to collaborate with us on an exhibition highlighting some of the more interesting discoveries in the Tudor arena, I responded with what must have seemed unseemly enthusiasm. On one level it was naturally a very great privilege to work with such an esteemed historian and communicator – cause enough for celebration. However I was also personally delighted to have the opportunity to show how making and announcing art discoveries can have a more substantive purpose and legacy when set in the context of academic history.

“When we lurched into life as a business twenty years ago it was discoveries in a modest form that both paid the rent and paved the way for the future identity of the company. We found that the subject of revealing lost faces, with its inherent humanity and drama was something people liked to read about, and some years later, as a further response to this phenomenon, I wrote Sleepers, which was an account of some of the more sensational finds in the art business, combined with some insights into both the process and the people who make them.

“A discovery requires three elements to turn it into a story: a discoverer with whom the reader can identify; the recovery or disclosure of something that matters; and a writer or commentator who can authoritatively communicate the discovery’s significance. The reason that we get asked regularly by newspaper editors for any discoveries is that they are a valuable news commodity. But it goes both ways. Not only do they sell newspapers, they are also one of the few ways that history and antique art can compete with celebrity, sex scandal and world wars for news headlines. In other words it allows art and history a safe passage into the hearths of middle England…”

THE ENTRANCE OF DAVID STARKEY

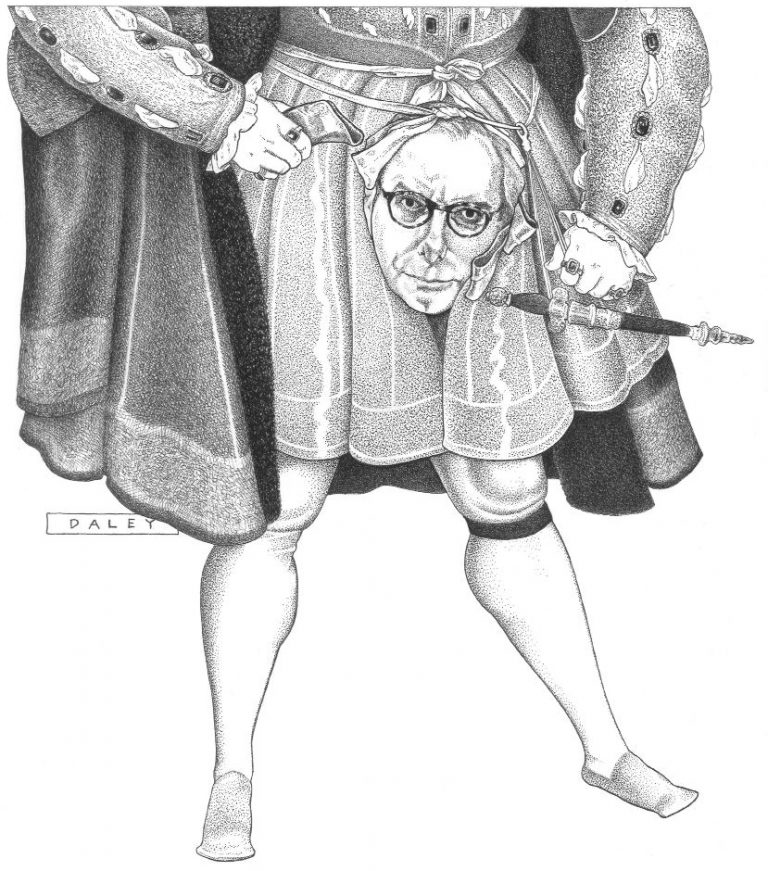

Above, Fig. 9, an ink drawing (in the collection of Professor Edward Chaney) of David Starkey made by the author to illustrate a profile article, “The apoplectic academic”, by D. J. Taylor, in the Independent on Sunday, 9 November 2001.

The Independent profile had tracked Dr Starkey’s pathway to celebrityhood:

“In the absence of the late Sir Malcolm Bradbury, whom can we safely characterise as Britain’s foremost media don? …by far the most successful performer in this glitzy but exhausting medium, delight of both the set-tethered TV audience and the browsers of bookshop history shelves, is the engagingly self-styled ‘academic thug’, David Starkey. Strictly speaking, to mark down the Tudor bruiser as a media don is a technical inaccuracy. Dr Starkey no longer teaches professionally, and the Cambridge quadrangles and the senior common room of the LSE have yielded up to ‘private research’ and solitary archival jaunts…

“For a bright, academically inclined teenager, the path from the local grammar school could lead only south, in this case to Cambridge, where he took a first in history and became a protégé of the leading Tudor historian of the age, Professor Geoffrey Elton. Starkey quickly decided that Elton’s view of history was sharply opposed to his own. Elton’s magisterial analyses of Tudor government rested on ideas of bureaucratic improvement. Starkey, on the other hand, was a personality man, seduced by the thought of titanic egos in conflict, ante-room punch-ups and backstairs intrigue. His first book, The Reign of Henry VIII: politics and personalities, was among other things a spectacular debunking of the Elton line. Sir Geoffrey is supposed to have taken this intellectual throwing over very hard…”

THE ROLE AND IMPORTANCE OF VISUAL EVIDENCE

In the catalogue’s Introduction, Starkey spoke with verve to the great importance – and the rarity – of visual evidence in historical studies:

“‘Henry VIII’, the lecturer declared, ‘is the only king whose shape you remember’. He then proved his point with a quick blackboard sketch, which deconstructed Holbein’s great full-length portrait into its elements of almost Cubist geometry. He made the body a trapezium, the legs splayed columns, the arms triangles, the head and neck a single massive cylinder, and finished off with the hat, which he drew with a flourish as a short acute angle to the head.

“We all laughed, for once un-sycophantically, as back then we were unused to visual aids and the joke was rather a good one. The time was 1964; the place a Cambridge lecture theatre; and the lecturer G. R. Elton. Elton was already the doyen of Tudor studies, but he spoke more truly than even he knew. For without the Holbein painting, how would we have an image of Henry at all? And without an image, how could Henry be memorable let alone world-famous? Would even, that is to say, the upheavals of the Reformation and the magnificent storyline of Henry and his Six Wives be enough if we could not envisage so vividly the male lead, let alone the female co-stars?

“I think not. For, speaking now as a television presenter as much as an historian, seeing is more than half of believing and almost all of caring. This means that Holbein’s painting is more than ‘the most enduring of all Henry VIII’s portraits – perhaps indeed the most memorable image of any English monarch’, it is Henry. It is, more than anything else, the reason that he fascinates us and that we study him; it is, I would go further, the beginning of his biography and the key to his mind. Once, it was poets who had promised eternal fame; with the Renaissance, painters were able to offer a more certain and enduring pathway to celebrity.”

In the 2007 Mould catalogue Dr Starkey made no further claims for the Windsor Anne Boleyn likeness. Dr Grosvenor, the catalogue editor, took the reins – and, later, part-credit for its acceptance by the Royal Collection, as in his 15 December 2011 Art History News post “Anne Boleyn regains her head”:

“…There used to be an article online in The Times detailing how research by myself and David Starkey had helped confirm the identity. But it has now disappeared behind the paywall. So below the jump, and online for the first time, is the article I wrote for an exhibition at Philip Mould in 2006 [sic] called ‘Lost Faces – Identity & Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture’, which was guest curated by David. The article was in the context of a fine but posthumous portrait of Anne we had borrowed from Hever Castle, Anne’s childhood home [Fig. 10, below, left]. The Royal Collection have found all the evidence compelling enough to change their cataloguing of the drawing (saying ‘this is a rare surviving portrait of Anne’), which is very pleasing. Let me know if you agree (or disagree)!”

The Times (“Nightgown clue turns Holbein’s unknown lady into Anne Boleyn”, 14 March 2007) had reported:

“Academics have now traced the inscription to Boleyn’s contemporary, Sir John Cheke, who began his career at the court under her patronage, before becoming secretary to Edward VI. A document of 1590 notes that Sir John inscribed numerous Holbeins for the King, helping to identify faces of royals and courtiers. Bendor Grosvenor, who carried out the research with David Starkey, the Tudor Historian, said: ‘Cheke was one of the brightest brains of the Tudor court. He would have known most of Holbein’s sitters, if not on personal terms, then at least visually’…Mr Grosvenor, who works at Philip Mould Historical Portraits, London, said: “it is inconceivable that she did not sit at some point for her portrait…’ The drawing appears to be a most unqueenly portrait, as the sitter is wearing a nightgown. Mr Gosvenor said: ‘Only a woman of the highest rank would have taken such a liberty in court circles.’ …The Royal Collection accepted that the portrait was of Boleyn.”

Among respondents to Grosvenor’s 2011 Art history News post, the author Claire Ridgway said on her Anne Boleyn Files blog: “…it is a very interesting read when compared with the thoughts of Eric Ives and Roland Hui…”

In a January 2000 post (“A Reassessment of Queen Anne Boleyn’s Portraiture”), Hui had noted that:

“The confusion surrounding the portraiture of Anne Boleyn was addressed by the art historian E. W. Ives in his biography of the Queen in 1986…In regard to the [Windsor] Holbein sketch, John Rowlands and David Starkey have proposed that the sitter was indeed Anne Boleyn… She is seen in three-quarters profile dressed in a furred robe over a chemise laced at the throat, and wears a simple undercap…Rowlands and Starkey have argued that such ‘undress’ on the part of this ‘royal’ sitter was a novelty of sorts to ‘relax’ the dictates of court etiquette. However, it seems unlikely that Anne with her much commented upon sense of style would have permitted herself to be depicted as such…Since her early days at court Anne Boleyn had a reputation in fine dressing in fashion-setting. George Wyatt, the grandson of Anne’s admirer, the Celebrated poet Thomas Wyatt, wrote that in her attire ‘she excelled them all’. Even those hostile to Anne Boleyn, such as the Elizabethan Catholic Nicholas Sander, admitted to the Queen always being ‘well dressed, and every day made some change in the fashion of her garments’…”

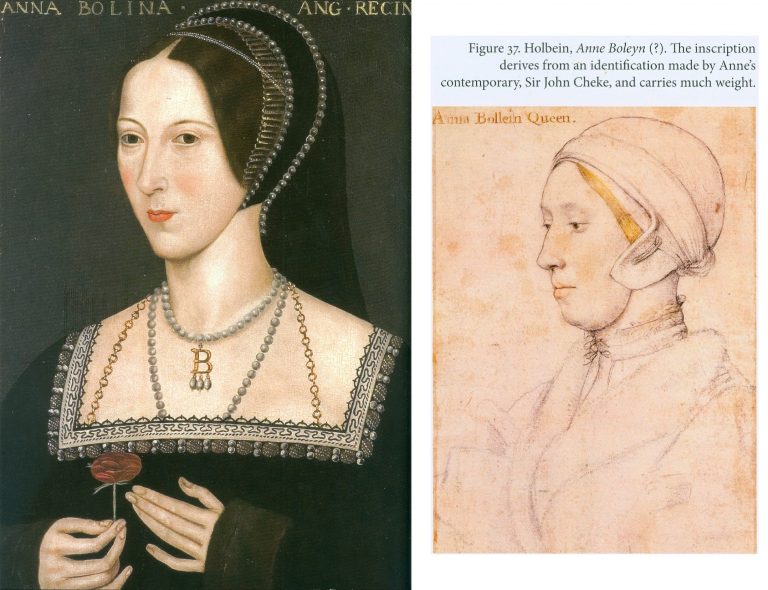

Above, Fig. 10: The photo-linkage that was carried across two pages of Anne Boleyn-ascribed works, as discussed by Grosvenor in the 2007 Philip Mould Gallery catalogue “Lost Faces – Identity & Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture”.

Note that, as seen above, in Grosvenor’s section of the 2007 Mould catalogue, the proposed Windsor sitter’s identification as Anne Boleyn carried a parenthetical question mark, and that nothing more was said of Cheke’s claimed identification of it than that it carried much weight – when, by the same token, so too must Cheke’s identification of the British Museum Anne – to repeat: because the two drawings’ sitters are, as everybody agrees, physically incompatible, if Cheke was right on one he had to be wrong on the other. In three decades of campaigning no one had established that Cheke had only endorsed the one drawing and not the other.

In “Lost Faces”, Grosvenor acknowledged his own restating of Rowlands/Starkey and strenuously endeavoured to show that Cheke had been proved right on almost every sitter’s identification. To two Ives-cited Cheke misidentifications he responded:

“We can surely forgive Cheke these errors, for the drawings date to Holbein’s first trip to England between 1526-8, well before Cheke came to Court.”

Ives had written:

“Most worrying of all, the portrait of Margaret Clements, More’s foster daughter, is identified as ‘Mother Jak’, Edward the VI’s nurse. Not only is it highly likely that Cheke knew Margaret – her husband John was erstwhile reader in Greek at Oxford, and Cheke was Regius Professor of Greek at Cambridge – but, as tutor to the future Edward VI, Cheke undoubtedly knew the real ‘Mother Jack’. Clearly, his authorship of the current [Anne Boleyn] identifications is highly questionable.”

CONCEALING GOITRES

Like Rowlands/Starkey, Grosvenor took the politically hostile witnesses’ accounts as firm corroborations of the Windsor drawing’s Anne. One such, Nicholas Sanders, alleged “a large wen under her chin” which she had attempted to conceal. Where Ives had rebutted Sanders’ testimony outright – “one can dismiss out of hand the arguments which seeks to link the [Windsor] sitter’s double chin and high collar with… a velvet mantle with a high collar to conceal a scrofulous neck” – Grosvenor countered: “We do know, however, from another contemporary source Sanders’ description of a swelling under her chin was probably correct.” A footnote to this claim cited Sir Roy Strong’s seminal work Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, but, as readers of Strong’s book will appreciate, while he had indeed identified a second observer (who claimed a grossly disfiguring wart and a swelling “resembling a goitre”), he, like Ives later, had dismissed both observers as hostile and, in Sanders’ case, of also being “too late to be taken as reliable evidence”.

DISCOUNTING AUTHORITIES

Although Grosvenor had cited both Strong and Ives in footnotes, on the former, he might have left an impression of support for his own position when Strong had not only dismissed the hostile witnesses’ reliability but had also noted that their accounts were incompatible (had failed to “harmonise very closely”) with the later painted pictures of Anne. Strong’s recognition of the testimonial value of the later paintings highlights the collective and abiding failure of the Windsor drawing’s successive champions to acknowledge and heed the evidential force of artistic images when, properly considered, such works of art themselves constitute primary documents as (truly) concrete manifestations of highly specific and personal artistic/intellectual productions. Grosvenor’s footnote on Ives’ 1994 Apollo article said no more of him than that he was one of the “authorities [who] have dismissed the validity of the [Windsor] ‘Anna Bollein’ inscription due to other inconsistencies and errors in the [Cheke] identifications.”

Ives had objected to more than the unreliability of Cheke’s identifications. He had made a methodologically rigorous visual and comparative appraisal of the available pictorial and graphic records that would have done a trained art historian proud. He rejected the two Holbein Anne Boleyn drawings as likenesses of Anne – but not equally so. While recognising that a case can be made for each, he pointed out that where the British Museum Anne looks the part – “The love of Henry VIII’s life should have looked like that” – against that, the “curious undress” of the Windsor sitter suggested that rather than being a queen, “A far more likely explanation of the implied intimacy would be a link between artist and sitter”. The combined facts that Hollar had chosen to engrave the now British Museum Anne and not the Windsor Anne, and the latter’s intimate garb “should make further discussion of the Windsor drawing unnecessary”.

Having disregarded an entire tranche of historically adjacent paintings of Anne Boleyn, Grosvenor, following Rowlands and Starkey, subscribed to the veracity of the widely recognised malice on alleged facial disfigurements as reliable corroborations of the double chinned, heavy jawed sitter with the (disqualifying) fair-not-famously-dark hair in the Windsor drawing: “The chin in the drawing is perhaps swollen, and would accord with Anne’s alleged misfortune” – and this, despite Ives’ objection that the Windsor drawing sitter’s “almost bovine impression” was “fatally contradicted by the medal’s long assertive neck and its total absence of a double chin.” (See Fig. 11, below.)

ROYAL HEADWEAR

Above, Fig. 11: Left, the British Museum-owned 1534 Coronation medal; centre, top, the British Museum “Anne Boleyn” Holbein drawing (mirrored) and, bottom, the Windsor “Anne Boleyn” Holbein drawing; right, the Hever Castle Anne Boleyn painting loaned to the 2007 Mould Gallery exhibition. Although the medal is certainly damaged, pace Rowlands/Starkey, it clearly shows Anne to be attired and be-jewelled, as in the B.M. drawing. The sitter in both wears a “gable hood” – which fashion would be superseded within Anne’s own reign by the “French Bonnet” fashion, as found in the Hever paintings. In the above formation of images, where the similarities of costume and composition arc from the medal through the British Museum Anne to the painting, the Windsor drawing, by contrast, acts as a circuit breaker between the medal and the painting.

Where Grosvenor made no comment on Strong’s recognition of the wider testimonial force of artistic depictions, on the testimony itself he faced both ways, declaring on the one hand that “The author does not believe that the [Windsor] likeness… is totally dissimilar to the later portraits of Anne, such as that exhibited here [the Hever Castle portrait at Fig. 11, above, right]”, while, on the other hand, dismissing the testimonial power of the later portraits en masse:

“As with all posthumous portraits, however, they are subject to the historical, political, and visual prejudices of those who created and commissioned them. They cannot give us an accurate picture of what Anne really looked like”.

THE PERILS OF DISAVOWING PICTORIAL TESTIMONY

Above, Fig. 12: Left, as shown in Part I, appraising and evaluating artistic productions is not a mystical or even an entirely subjective exercise. As seen above, left, while the Windsor sitter was shown in nightwear and sans jewellery, Holbein’s British Museum sitter was fully dressed and with indications of three rows of necklaces. Many paintings of Anne show her in precisely such dress and so be-jewelled – jewellery which often included her initial “B” as a suspended centrepiece. Elsewhere in the Mould catalogue, Grosvenor accepted the testimonial power of jewellery when defending Cheke’s reliability on a Holbein sitter that had been doubted – “The Lady Mary after Queen”:

“But the Holbein drawing certainly is Mary. A study of the jewellery allows a positive identification to be made…”

Above, right: with the British Museum Anne Boleyn drawing, not only does the indicated jewellery clinch the status of the drawing as the precursor to the paintings, it was (as previously shown) further possible to demonstrate the clear derivation of a particular painting (also at Hever Castle) from the drawing.

Above, Fig. 13: In the above sequence it is possible to see a morphing familial relationship in the faces in which, notwithstanding stylistic changes, a progressive sequencing of slight rotations of the head from the original near profile drawing (in which the nose fractionally overlapped the cheek contour and the edge of the gable hood) progresses towards a more frontal face in which the eyes in the second Hever Castle Anne painting (here mirrored) turn to confront the viewer.

DOUBLE CHINS AND CHEKE’S RELIABILITY

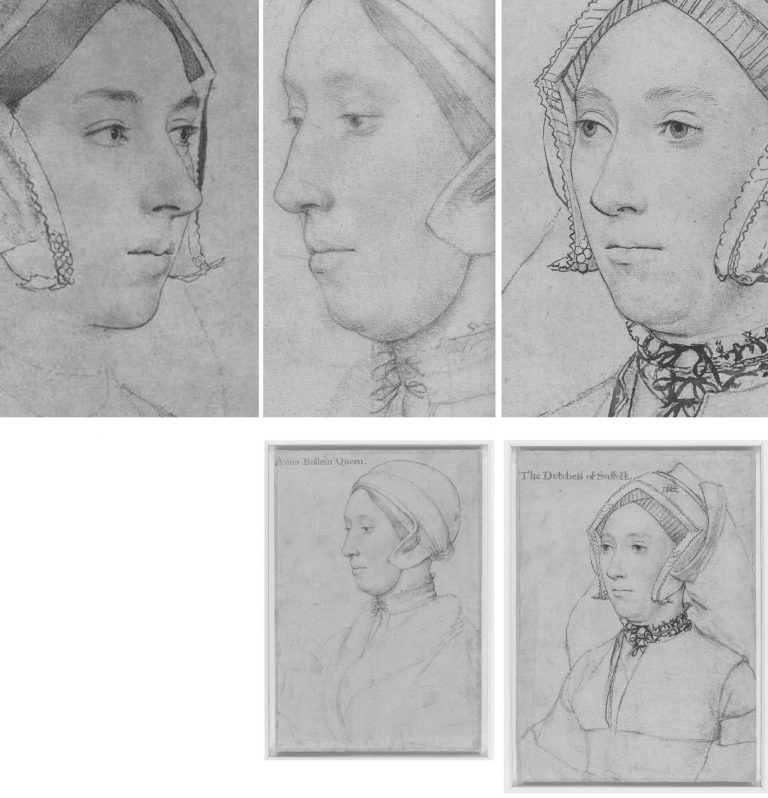

As shown in Part I, the features of the Windsor sitter markedly better resemble those of the ascribed Duchess of Suffolk (Fig. 14, below) than those of the British Museum drawing. As mentioned, when Starkey paired with Rowlands in the 1983 Burlington Magazine article hopes of a visually supported case for the Windsor “Anne Boleyn” were dashed, and again, with Starkey/Grosvenor, after three decades, no direct visual comparison of the rival Holbein drawings was offered to readers.

Above, Fig. 14: Left and centre, the British Museum and the Windsor Holbein “Anne Boleyn drawings; right, the Royal Library’s “The Dutchess of Suffolk”. Note, in the case of the British Museum Anne, a nostril that is markedly larger than the two similarly shaped nostrils on the other two drawings.

Collectively, Rowlands, Rowlands/Starkey, and Starkey/Grosvenor had all failed to acknowledge that the sitter in the Windsor drawing was not the only double-chinned, high cheek-boned lady wearing a (potentially) goitre concealing, neck-tied chemise in Holbein’s drawn portraits. As seen above, Holbein’s later inscribed portrayal of Katherine Brandon, the “Dutchess of Suffolk”, bears not only another double chin but an almost identically laced and tied high-necked garment. Were both sitters scrofulous? Or might they have been one and the same person?

CODA: AGE CUTS BOTH WAYS

Ironically, an unsuccessful attempt was made in the Lost Faces exhibition to re-assign the identity of the Duchess of Suffolk’s sitter to an earlier wife and to count the proposed switch as another Mould and co. “discovery”. Grosvenor raised the reliability of the ascribed Duchess of Suffolk sitter:

“…there has been some confusion about which ‘Dutchess of Suffolk’ Holbein shows, an issue raised below in some detail by Alisdair Hawkyard.”

Hawkyard, possibly in emulation of Starkey on “Ormond”, wrote:

“One of the drawings of a sitter whose identity has been doubted is inscribed ‘The Dutchess of Suffolk’. She has been identified as Catherine Willoughby born c. 1519 who in September 1533 married her guardian Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. The woman depicted is more mature than Catherine would have been had she sat to Holbein before his death in 1543. The sitter’s greater maturity suggests that she was Suffolk’s third wife Mary who died on 25 June 1533. Mary, Henry viii’s younger surviving sister, had married Suffolk in 1515 while still in mourning for her recently deceased husband King Louis xii of France and without the consent of either her brother or the new King of France, Francis I. The physiognomy of the Duchess accords with what is known of her appearance…”

If Hawkyard’s objection seems a fair one, it would follow that the very similar-looking Windsor sitter is also too old to be Anne who, on Ives’ reckoning, was thirty-one when Holbein began his second visit to England and thirty-five when executed. Grosvenor dismissed the British Museum drawing’s sitter on grounds of age: “Alas, this pretty sitter is too young to be Anne”, adding, “The drawing has been convincingly discounted by, among others, John Rowlands”. (Which others? – the people who “apparently” had “generally accepted” Rowlands’ identification?) On Anne’s age, Margot Robbie, who played Barbie in the recent film, is thirty-three. Lily James is thirty-five. Had the Royal Collection accepted the Grosvenor/Mould Gallery’s proposed re-identification of the Duchess of Suffolk sitter, it would, of course, have spoken further against Cheke’s reliability.

Despite Grosvenor/Starkey’s reported claims to have “traced” the Windsor drawing’s provenance to Cheke and to have discovered a document of c. 1590 which noted that Cheke had inscribed “numerous Holbeins for the King”, as mentioned above, there had been no tracing or discoveries because the claims made had derived directly from (and added nothing to) Parker’s 1945 account. Viz:

“…The basis, of course, for all such inquiry is the evidence provided by the inscriptions on the drawings themselves, or to be more exact, by the inscriptions that appear on sixty-nine of the total of eighty-five, the further sixteen having remained nameless. At this point we must revert to the Lumley inventory of 1590, and complete the quotation of that vitally important entry with the further information that the names were ‘subscribed’ to the drawings by ‘Sir John Cheke, Secretary to the Edward the 6.’ One of the most learned men of his day, Cheke, then in his twenties, was summoned to Court in July, 1542, to succeed Richard Cox as tutor to Prince Edward. On the newcomer’s arrival, therefore, Holbein himself was still on the scene, and the circle of his more recent sitters still about him. That Cheke must have had personal contacts with many of them is beyond doubt. It follows that if the names now inscribed on the drawings correspond, as presumably they do, with Cheke’s identifications referred to in the inventory, they have abundant claim to interest and attention, though not, of course, to blind faith. It is demonstrable that their accuracy is not infallible, nor can the date of their recording have been otherwise than belated.”

Moreover, respectful as he had been of Cheke’s authority, Parker had rejected the Windsor drawing’s identification as a portrayal of Anne Boleyn:

“The inscription is certainly incorrect, the features showing no resemblance whatever with the well authenticated drawing of Anne Boleyn in Lord Bradford’s [now the British Museum’s] possession.”

SUGGESTIONS BECOME FACTS

Grosvenor’s counter to Parker’s dismissal of the Windsor “Anne” comprised nothing more than appeals to the authority of his predecessor-partisans’ authority:

“The present author, however, here restates an earlier suggestion that the sitter is, in fact, Anne Boleyn – Originally suggested by John Rowlands and David Starkey in ‘An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein’s portrait of Queen Anne Boleyn”, Burlington Magazine, CXXV (1983).”

Cheke was personally pressed into Grosvenor’s service:

“On simple probability alone, the chances of the [Windsor] inscription being erroneous are slim. And, as mentioned above, Anne is one of the sitters Cheke was least likely to get wrong.”

Grosvenor’s 2007 contention was thus, like that of Rowlands/Starkey in 1983, yet a further sleight of hand: Cheke cannot be held to have ascribed the Windsor drawing alone, because, on the same historical record, he had also ascribed the now British Museum drawing. The Royal Collection switched the Anne Boleyn identities in error and on a case lacking either scholarly merit or visual credibility – this truly was a spurious discovery.

Michael Daley, Director; 31 May 2024

Leave a Reply