Holbein’s Anne Boleyns and the “Discovery” Trope

Art is made by artists to order, or for the market, or from personal compulsions. Thereafter its standing is determined by others – primarily scholars, curators, auctioneers, and dealers – who confirm or reject the authenticity of works and the identities of sitters within them. Such judgements are often presented not as expert, professional opinions on which scholarly discussions might proceed, but as discovered truths. Discoveries can be well-founded or spurious. In art restoration, where claimed “discoveries” so often mask bungled interventions, the proof of the pudding is in the looking (at comparative photo-records) and it should be considered so, too, with claimed art historical discoveries.

A CASE IN POINT: TWO HOLBEIN ANNE BOLEYN ASCRIPTIONS

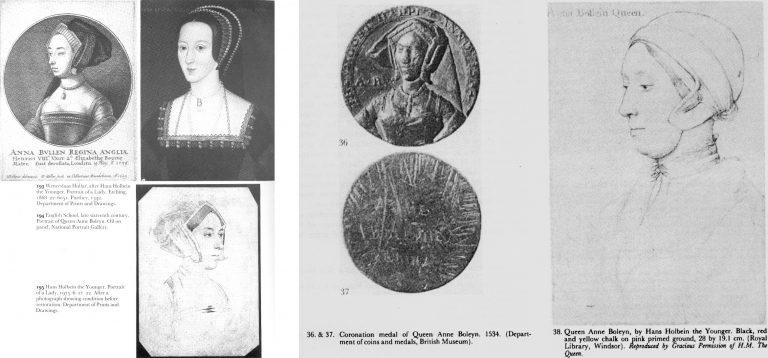

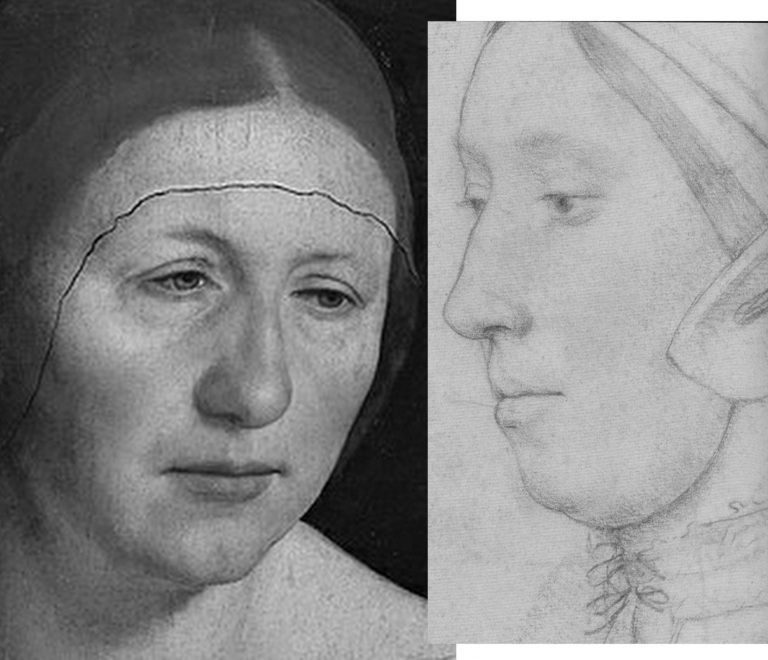

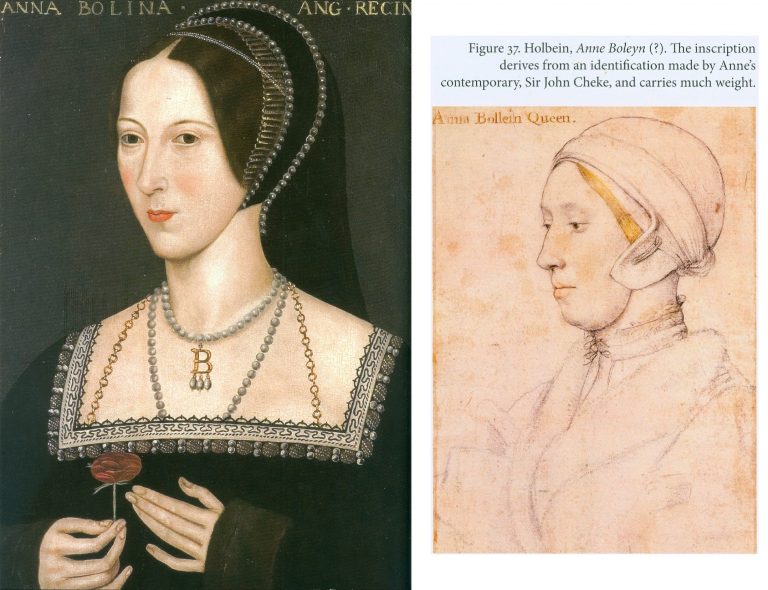

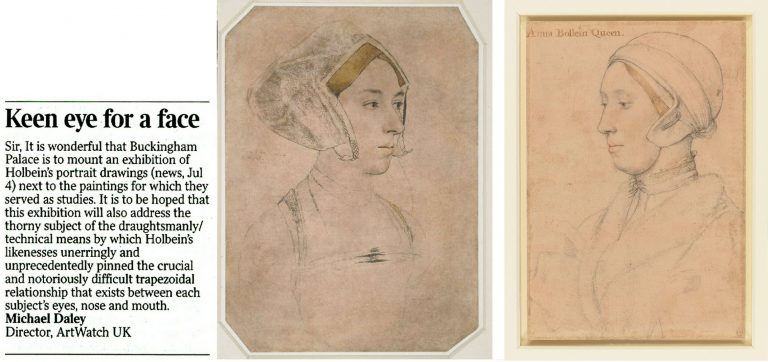

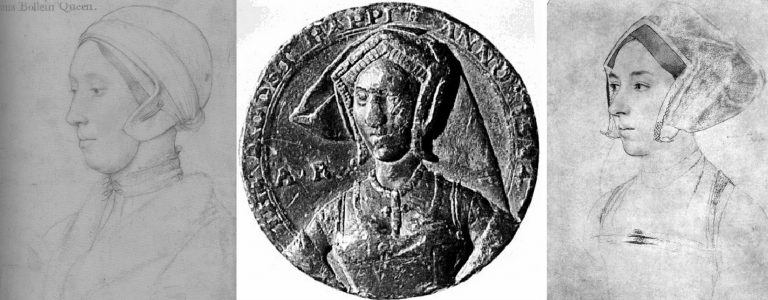

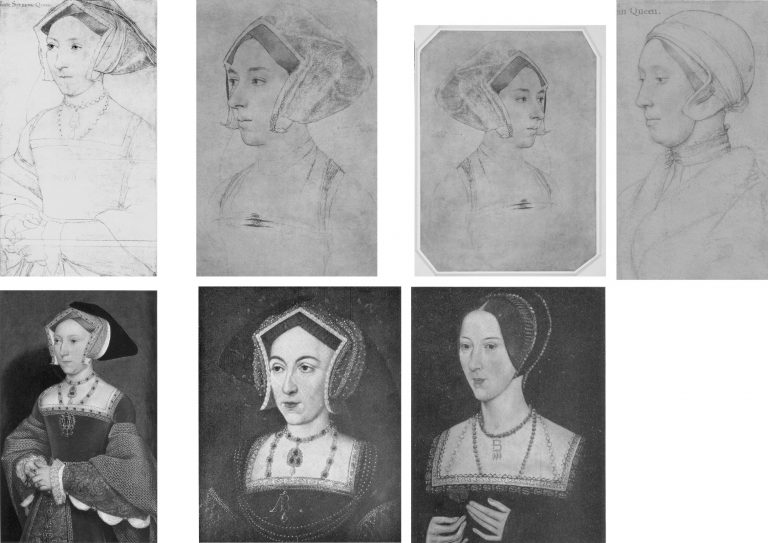

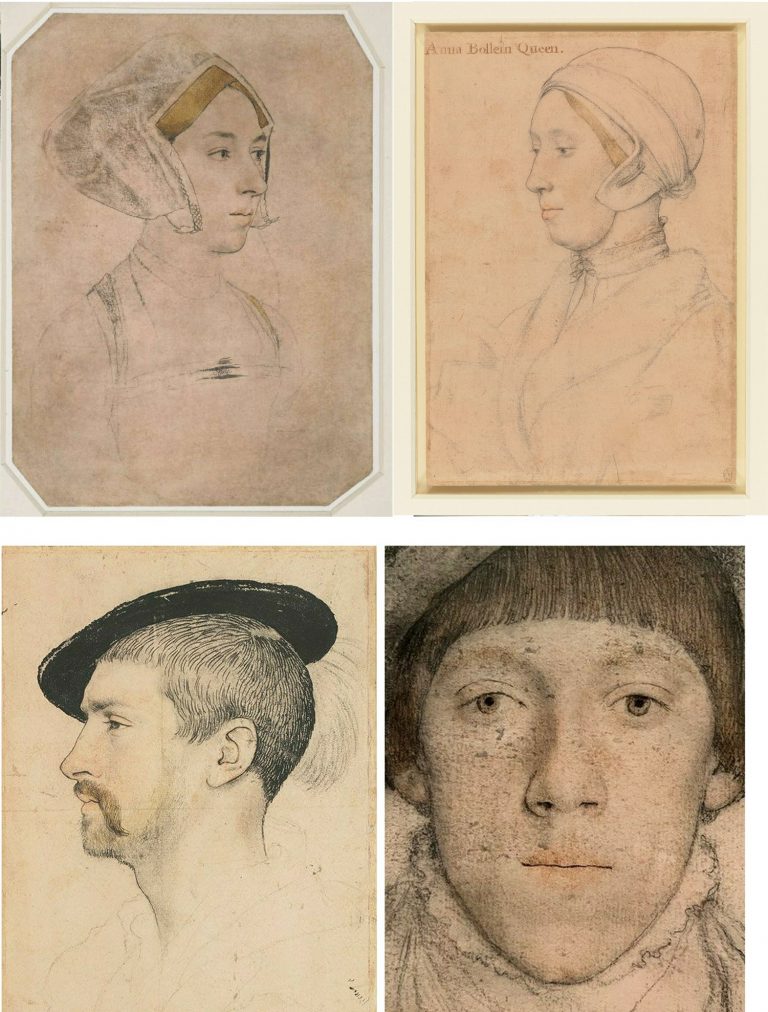

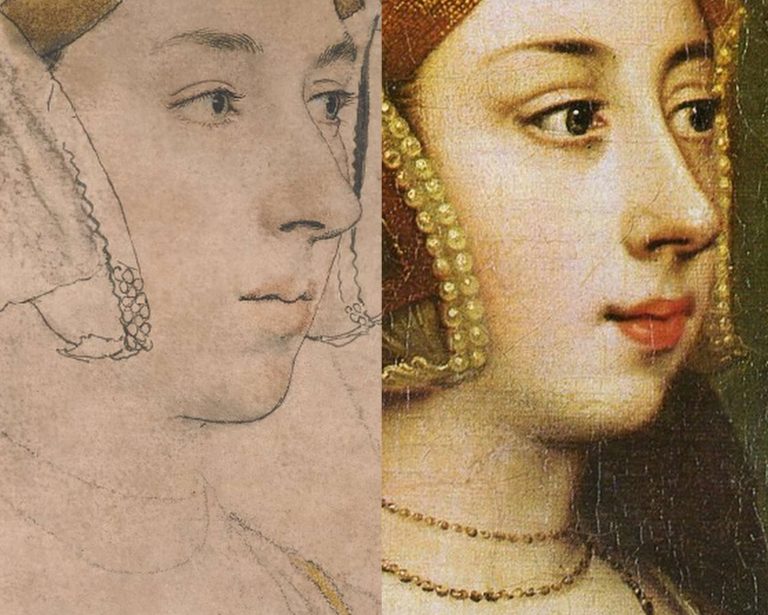

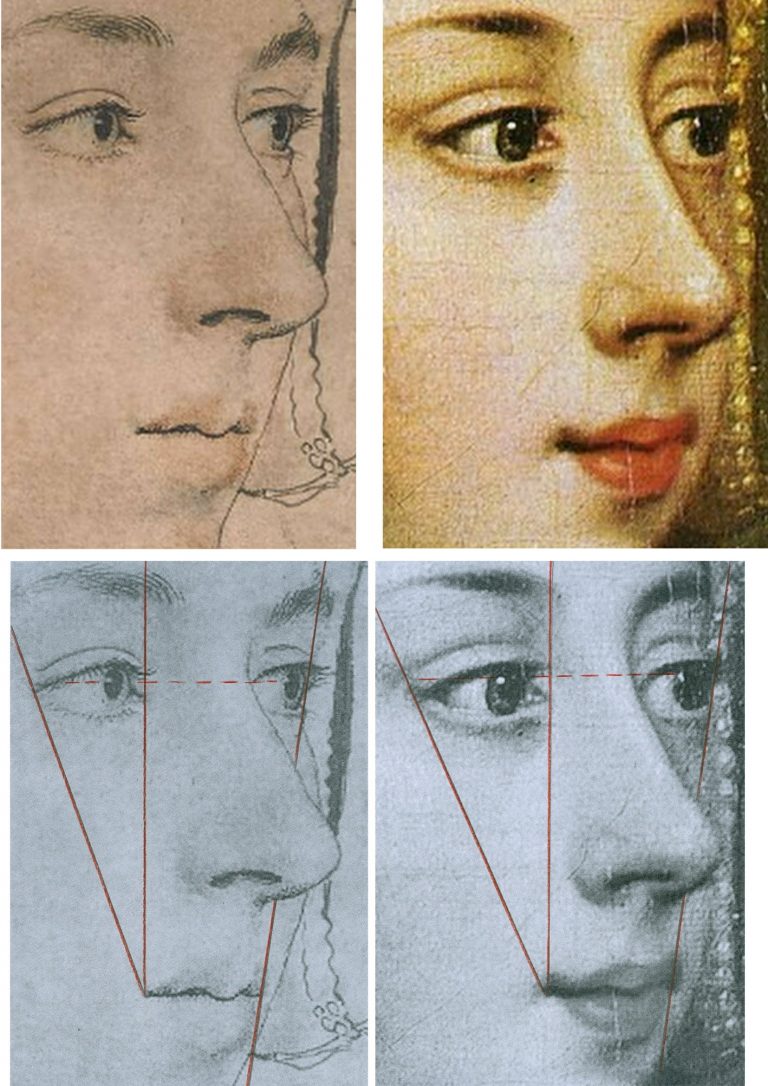

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the British Museum (formerly “Bradford”) Anne Boleyn-inscribed Holbein drawing; right, the Royal Collection Anne Boleyn-inscribed Holbein drawing.

Both of the above English Holbein portrait drawings are securely provenanced – both entered the Royal Collection on Holbein’s death. Both bear inscriptions identifying the portrayed sitter as Anne Boleyn. One or other of the drawings might be of Anne Boleyn but both cannot be so because, as all parties are agreed, the drawings depict two different people. In this case both sitters had been identified by the same respectable near-contemporary witness, Sir John Cheke, but for almost five centuries everyone had taken the (now) British Museum drawing to be the true record of Anne’s likeness. In the last half-century an overlapping succession of three people (an art historian, a Tudor historian and a modern historian) laboured for three decades to reverse that traditional identification. They all did so without offering a direct photo-comparison of the two drawings at issue. Effectively, this campaign was an anomalous images-light war of words.

We take the eventual success of that campaign as a prime case of a visually unsupported and spuriously claimed discovery, notwithstanding its seeming vindication in 2007 when the Royal Collection held that its Anne Boleyn-inscribed Holbein drawing bears the ill-fated queen’s likeness. Four years later that dramatic reversal was recalled/celebrated by Bendor Grosvenor in a 15 December 2011 Art History News post “Anne Boleyn regains her head”:

“This isn’t ‘news’ as such, but in a foray into the Tudor realms of Twitter last night I mentioned the drawing of Anne Boleyn by Holbein in the Royal Collection. I said that although in the past the identity was doubted by art historians, the sitter was now catalogued with certainty as ‘Anne Boleyn’, as you can see on the Royal Collection website…”

That claimed certainty of identification had rested on a three-stage campaign that ran between 1977 and 2007 and to which Grosvenor had contributed last. It proceeded as follows.

STAGE I: A REVISIONIST CHALLENGE

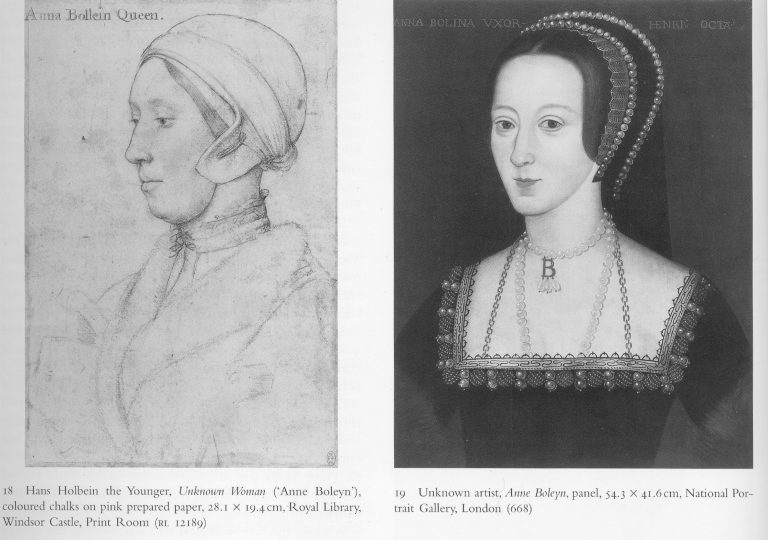

In 1977 John Rowlands, the deputy keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum, challenged the traditional identification of Anne in the museum’s newly acquired landmark Holbein Anne Boleyn drawing. He did so in a commemorative article (“A portrait drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger”) carried in the British Museum YEARBOOK No. 2. The challenge rested on an objection that the drawing’s documentary records began in the 17th century (- see Part I: Sex, Trigonometry and Anne Boleyn’s Recovered Likeness.) Rowlands’ article carried just three photographs (Fig. 2, below) with none showing the Windsor Royal Library drawing being proposed as the true Anne Boleyn Likeness.

STAGE II: THE 1983 ROWLANDS/STARKEY COLLABORATION

Six years later, Rowlands co-authored an article with the Tudor historian David Starkey in the February 1983 Burlington Magazine (“An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein’s Portrait of Anne Boleyn”). Dr Starkey had scored a Bull’s Eye in a 1981 Burlington Magazine article (“Holbein’s Irish Sitter?”) by identifying a more plausible sitter in a Royal Collection Holbein drawing given to “Ormond”. As Jane Roberts put it in her 1993 National Galleries of Scotland Holbein and the Court of Henry VIII catalogue:

“The old identifying inscription, ‘Ormond’, has led to some confusion concerning the subject of this drawing. There were for a time two rival claimants to the Earldom of Ormond (or Ormonde): Thomas Boleyn (1477-1539) and James Butler (c. 1504-46). The former, the father of Anne Boleyn, was considered the most obvious candidate, although it was remarked that the drawing appeared to show someone younger than fifty (Thomas Boleyn’s age at the time of Holbein’s first visit to England.) David Starkey has plausibly suggested that the drawing instead represents James Butler, son of Piers Butler, the illegitimate kinsman of the 7th Earl of Ormond (died 1515) and claimant to his title and lands…”

As with Rowlands, Rowlands/Starkey gained no official acceptance. Recognition would only be obtained in 2007 when Starkey joined forces with the Philip Mould Gallery in an “identity discoveries” fest, some thirty years after Rowlands’ initial challenge (see below). Where Starkey’s independent professional historical elucidation of Ormond familial relationships had proved valuable to art historians, on his 1983 pairing with Rowlands he became a partisan/advocate to a historically unsupported and visually unexamined ascription. On this turkey of a case, Starkey’s professional juju failed.

Offering no visual argument, Rowlands/Starkey effectively attempted a verbal sleight of hand on a non sequitur by holding that because Sir John Cheke (the source of the English Holbein portrait drawings’ sitters identifications) might have been better placed to validate an Anne Boleyn inscription than had previously been appreciated, the Windsor drawing’s sitter therefore was the true Anne Boleyn likeness. Thus, the logical flaw of Rowlands’ initial 1977 essay remained: the more well-placed Cheke becomes as an identifier of sitters, the more reliable he becomes as the man who had also identified the sitter in the British Museum’s Anne Boleyn-ascribed Holbein drawing.

NO BEEF

The authors tacitly acknowledged the absence of corroborating evidence for the Windsor drawing’s sitter by contending that “In view of all the evidence accumulated here it seems likely at the least that Holbein was taken up by the Queen as well”. (Emphases added.) Even if such a relationship been established, it could not in itself have weighed in favour of one rival Anne Boleyn inscribed drawing over the other, for reasons given – but it had not been so established: a “likely” is not a “was” – and nor is a “likely was”. In an article cumulatively held together by a “could have”; a “would have”; a “must have”; a “could well have”; a “could have taken”; a “had every reason to take”; a “most likely”; and, a “we would guess,” the authors’ peroration itself comprised a further mini daisy-chain of question-begging speculations (emphases added):

“…his appointment as the King’s painter probably antedates it. And the likely responsibility rests with Anne Boleyn herself. For it may not be a coincidence that Holbein’s advancement at court… appears to have progressed largely through the favour of adherents to religious reform…”

That lame ending had followed a weak opening. The existence of the two rival Holbein Anne Boleyn drawings was acknowledged, as was the fact that they “clearly show different sitters”, but the drawings were not shown together side-by-side so as to permit a direct visual comparison – the authors’ claims had to be taken on trust. Similarly, it was claimed on no cited evidence that because Rowlands’ 1977 identification had “apparently” been “generally accepted” the case for the possible authenticity of the Windsor Anne Boleyn inscribed drawing “must be re-opened”.

ABSENCES OF EVIDENCE

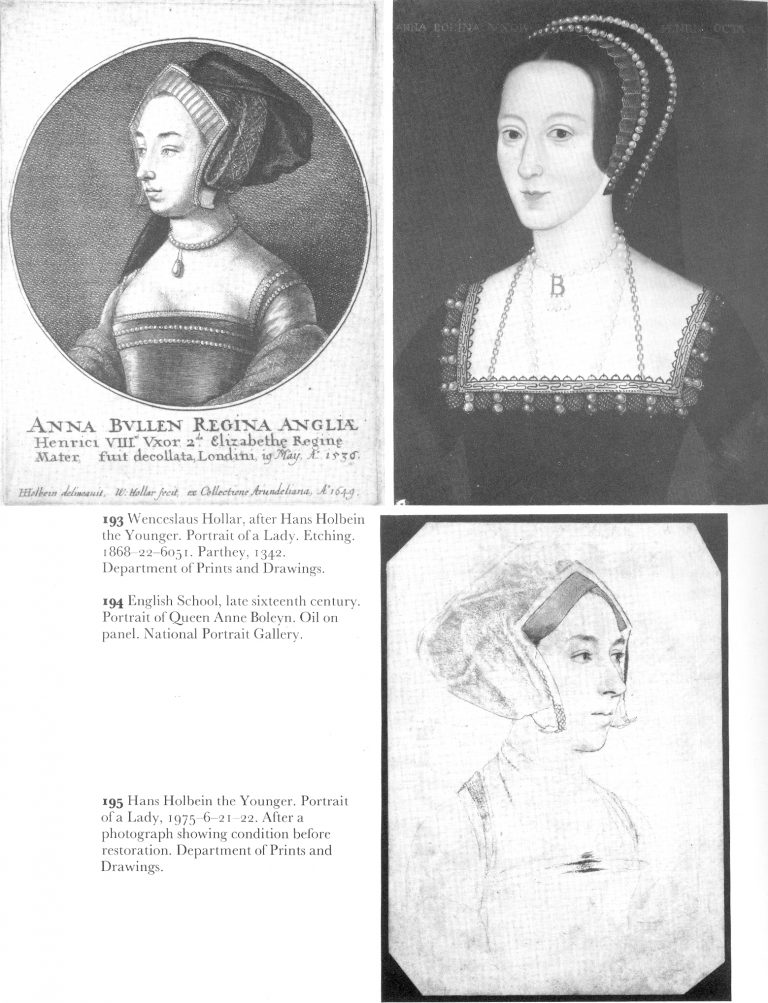

Had Rowlands’ 1977 case been accepted, there would have been no cause to reopen it in 1983. Whether Rowlands’ original claims had been partly/largely accepted or not, the features on the two Anne Boleyn-ascribed drawings remained physically incompatible (see Figs. 1 & 3). Only one, therefore, might be a true likeness. Rowlands/Starkey conceded further absences of evidence for their position by (wrongly) claiming that no visually comparative means of adjudicating between the rival likenesses existed: “For such a re-examination there is no available visual evidence”. That assertion was made on the grounds that the only secure contemporary image of Anne is that on the damaged coronation medal of 1534. The damage on the medal is local and by no means robs the image of all testimonial capacity. When the authors published the medal and the Windsor drawing side-by-side, they claimed (rightly) that no correspondences exist between those two works, when, as can be seen at Fig. 2 below, there are clear correspondences with the British Museum drawing, the etched copy of it by Wenceslaus Hollar, and the National Portrait Gallery painting of Anne Boleyn.

Above, Fig. 2: Left, the three illustrations carried in Rowlands’ 1977 British Museum Year-Book II article “A portrait drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger”; right, the two illustrations carried in the Rowlands/Starkey February 1983 Burlington Magazine article “An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein’s Portrait of Anne Boleyn”.

As if aware that their “evidential” cupboard was bare, the authors continued “fortunately… there are other pointers”.

AN UNFORCED ERROR

The first Rowlands/Starkey “pointer” was that the sitter in the Windsor drawing shows, like Henry’s other queens, little signs of prettiness – “and certainly nothing to compare with the ‘Bradford’ lady’s charm, which could well explain why in the seventeenth century the latter was claimed to be the bewitching Queen”. By alleging a supposedly misleading power of influence to Anne’s appearance in the British Museum drawing, the authors tacitly conceded that it – and not the Windsor drawing – had for five centuries been taken as the true likeness and that it had informed the subsequent late sixteenth century Anne Boleyn paintings (see Figs. 10-13.) No iconographic legacy of any sort attaches to the Windsor “Anne”.

Against their own acknowledgement of the British Museum drawing’s historically influential artistic potency, the authors offered a subjective counterclaim that the Windsor portrait had given true expression to the “strong will and intelligence [of Anne Boleyn] that her contemporaries noted”. As shown above, below, and previously, the sleepy-eyed, older, fleshier, fair-haired not dark-haired sitter in the Windsor drawing does not look more charismatically strong-willed and intelligent than the British Museum drawing’s sitter. Had the authors’ estimation of the relative traits in the rival drawings been sound it would have helped their cause to demonstrate the relationship by showing the two likenesses together, as here below.

A PHOTO-COMPARISON THAT DID NOT SHOW ITS FACE

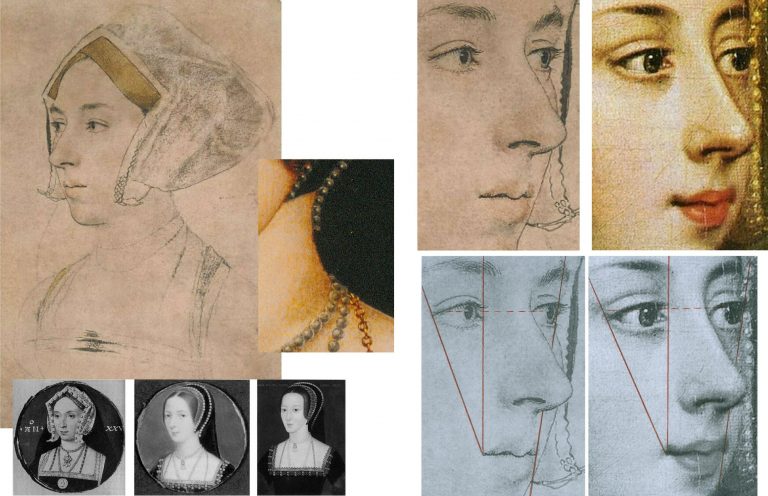

Above Fig. 3: Details of the British Museum Holbein Anne Boleyn-ascribed drawing, left, and, right, the Royal Collection Holbein Anne Boleyn-ascribed drawing.

POINTERS AND CONCRETE INDICATIONS

Evidently still fearful of the manifest weaknesses in their case and notwithstanding their own “pointers”, the authors cited certain “more concrete indications” of Anne Boleyn’s “appearance and dress”. These supposed concretely reliable indications were hearsay comments made in an acknowledged “anonymous and scurrilous French account” of Anne’s grandly ceremonial entry into London the day before her coronation. That is, Rowlands/Starkey presented as if concrete and corroborating evidence, the account of an unknown, manifestly malicious source who had described Anne as “scrofulous” (suffering from a form of tuberculosis and glandular swelling) and of having worn her dress fastened up very high on her throat to conceal a goitre. Thus, from Rowlands/Starkey: “In the [Windsor] drawing her double chin is so pronounced, as to suggest such a swelling of the throat glands, which is indeed partly hidden by a high neckline.”

There were so many problems with acceptance of that malicious account. First, the reported, supposedly goitre-concealing, garment worn by Anne was not her customary dress but what the Tudor historian Eric Ives described as “the traditional high-necked English coronation mantle”. Second, the Windsor drawing’s sitter was not wearing any form of day wear: “She wears some kind of under-cap and a furred nightgown over her chemise”. Third, the tied neck of the chemise did not conceal the double chin – only a very high turtle-necked garment might have done so. Fourth, the displaying of such “undress” for a likeness-recording artist, was held to constitute proof of regal identity because: “only a woman of the highest rank could have taken such a liberty in court circles.” Begging their own question, the authors added: “Several of Holbein’s male sitters appear in similar states of undress but Anne was the only woman to do so.” In this instance, a “could have” became a “was” in two breaths, with a seeming wish once again being the father of the deed.

Had Holbein drawn Henry’s second queen in such a state of undress, he would have put himself at risk of accompanying her and her alleged lovers to the executions. Had the fair-haired Windsor sitter been the mother of Holbein’s two English children, no suspicion of impropriety could have arisen. As it happens, downcast eyes and wistful expressions are common to the Windsor drawing and Holbein’s German wife, as depicted in his The Artist’s Wife and Children – detail below, left. (Also, as discussed below, the Windsor sitter bears certain facial similarities with another contested Holbein sitter in the Royal Collection.)

Above, Fig. 4: Left, detail, Holbein’s The Artist’s Wife and Children; right, a detail of the Royal Collection “Anne Boleyn” drawing.

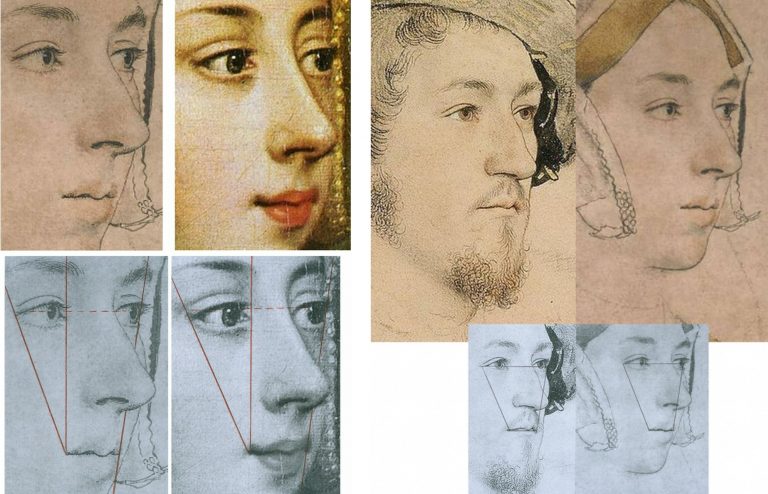

THREE NOSTRILS AND TWO TRAPEZOIDS

While nothing is known of the mother of Holbein’s two English children, Anne Boleyn famously had a brother, George, three or four years her junior, and with whom she was alleged to have committed adultery. No Holbein drawing in the Royal Collection is identified as George, but as luck would have it, one of Holbein’s unidentified portraits in the collection happens to have been made from a closely similar viewpoint to that of the British Museum Anne. As shown below, an unmissably similar configuration of brows, eyes, and nose is present in the two drawings. The only significant difference in the features is the appreciably more masculine jaw in the – here proposed – George Boleyn likeness. Unlike the Windsor sitter’s nose, those of George and Anne both have deep nostril apertures.

Above, Fig. 5. From left to right: ArtWatch UK letter, the Times, 5 July 2023; an unidentified Royal Collection Holbein drawing which we take to be of George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford; the British Museum “Ann Boleyn”; the Royal Collection “Ann Boleyn”.

HOLBEIN’S “UNIDENTIFIED MAN”

The above Holbein male portrait is today described by the Royal Collection as “An unidentified man, c. 1532-43”. Sir Karl Parker, author of the seminal 1945 Holbein’s Drawings at Windsor Castle, described it as “A Gentleman: Unknown”. Given the many facial similarities in the two drawings we can, perhaps, take it that Sir John Cheke had either not known Anne’s brother or had failed to recall him.

Above, Fig. 6: Left, the proposed Holbein portrayal of George Boleyn; right, the five centuries long accepted British Museum Holbein drawing of Anne Boleyn. Does this “George” not seem a little younger – and perhaps sweeter – than this Anne Boleyn? For that matter, has Holbein ever drawn eyes that are more vividly alive and penetrating than those found in this Anne?

Above, Fig. 7: Left, the similarities between the British Museum Anne and a later painting, as shown in Part I; right, the similarities between the Windsor “George” and the British Museum Anne.

STAGE THREE: A CASE NOT MADE

As with Rowlands, so Rowlands/Starkey had failed to effect a switch of the sitters’ identities. It would take twenty-four more years for victory to be claimed. On 14 March 2007 the Daily Mail (“Finally historians can give Anne Boleyn her head back”) reported:

“A Holbein drawing has been revealed as the only portrait of Henry VIII’s second wife Anne Boleyn. The c.1530 picture carries Anne’s name but other evidence suggested this was an error. Now expert Bendor Grosvenor and historian David Starkey have traced the inscription to her contemporary Sir John Cheke, confirming she is indeed the subject.”

No evidence had been presented by Starkey/Grosvenor that Cheke had specifically and exclusively ascribed the Windsor drawing – or that he had not also so ascribed the British Museum drawing. On the reported claims to have “traced” the Windsor drawing’s identification to Cheke, see below. Nothing had been found and nothing had changed – except, that is, the 1983 Rowlands/Starkey Burlington Magazine thesis had been robustly challenged and rejected in 1986 by a major Tudor historian, Eric Ives, in his biography Anne Boleyn, which work was frequently reprinted until 1994 and later superseded in Ives’ highly acclaimed 2004 The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn ‘The Most Happy.’ Starkey, author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII and Elizabeth, had generously described Ives’ biography as “The best full-length life of Anne Boleyn and a monument to investigative scholarship”.

THE IVES INTERREGNUM

Prof. Ives’ challenge to Rowlands/Starkey in his books had also been developed separately in a major article for the July 1994 Apollo magazine “The Queen and the Painters – Anne Boleyn, Holbein and the Tudor Royal portraits”. Where Starkey/Rowlands had taken two and a half Burlington pages, which included just two photographs, Ives’ essay ran over ten pages and carried sixteen photographs. Although not all pages addressed the Holbein Anne Boleyn drawings, Ives’ substantial scholarly and visually supported account seemed to have trumped Rowlands/Starkey and put the lid on the Windsor sitter campaign. So far as we know, Starkey never added to his joint 1983 Burlington article contribution. When Rowlands returned to the Windsor drawing in 1988 on publishing the British Museum portrait (which was then described as “Portrait of a Lady, thought to be Anne Boleyn”) in his catalogue to the museum’s “The Age of Durer and Holbein” exhibition, he claimed no more against the British Museum Anne Boleyn drawing’s ascription than that the “circumstantial grounds in favour of the Windsor drawing are really very compelling, and one cannot necessarily cast aside Sir John Cheke’s authority for the identification merely because of the confusion over a sitter in the Windsor series being called by him in error ‘Mother Iak’”.

Ives had indeed challenged Cheke’s reliability, and Rowlands acknowledged that his own (somewhat defensive) stance had followed the publication of Ives’ 1986 Anne Boleyn biography:

“Its rejection by Ives in his brilliant historical study is based on a mistaken disregard of the widely varying value of the different supposed likenesses of the Queen; for it is not wise to rely too readily on inferior Elizabethan portraits to form a basis for establishing her appearance.”

Thus, in another attempt to bolster Cheke’s reliability, Rowlands again discounted the testimonies of the many later painted portraits of Anne, none of which, as mentioned, showed any indebtedness to or affinities with the Windsor drawing. As shown in Part I and below, the markedly contrasting degrees of connectedness of the two Anne Boleyn-ascribed Holbein drawings to the many subsequent portraits of the queen constitute the art critical nub of this dispute: How and why had the British Museum Anne – and not the Windsor Anne – come to be held the true likeness for five centuries? To be clear: the contrary case presented for the Windsor Anne rested on nothing more than a) an assertion of near-infallibility in Cheke’s identifications; and b) a systematic disparagement of the visual testimony found in the (near-forty?) subsequent surviving late sixteenth century painted portraits of Anne. Nonetheless, where Rowlands, and Rowlands/Starkey had failed in 1977 and 1983 respectively, Starkey plus Team Philip Mould Ltd would seemingly prevail in 2007. It happened as follows.

TURNING ART MARKET STORIES TO COMPETE WITH SEX SCANDALS AND WARS

Above, Fig. 8: The catalogue to the 2007 Philip Mould Ltd “Lost Faces – Identity & Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture” exhibition.

The Philip Mould catalogue’s editor, Dr Bendor Grosvenor, set out the contributors’ aims:

“This exhibition seeks to raise questions, stimulate debate, and, where appropriate, suggest answers. Its purpose is intentionally provocative. The authors are indebted to those who have researched and published in the field of Tudor portraiture before. We hope that in bringing fresh eyes to bear on the subject we do not offend, merely illuminate further this fascinating subject.”

ADDING COMMERCIAL VALUE AND ACADEMIC RESPECTABILITY

The commercial and historical importances of attaching faces to historical figures was set out frankly and with passion, respectively, by Philip Mould and David Starkey. Mould began in the Foreword:

“When, early last year, David Starkey mentioned he would like to collaborate with us on an exhibition highlighting some of the more interesting discoveries in the Tudor arena, I responded with what must have seemed unseemly enthusiasm. On one level it was naturally a very great privilege to work with such an esteemed historian and communicator – cause enough for celebration. However I was also personally delighted to have the opportunity to show how making and announcing art discoveries can have a more substantive purpose and legacy when set in the context of academic history.

“When we lurched into life as a business twenty years ago it was discoveries in a modest form that both paid the rent and paved the way for the future identity of the company. We found that the subject of revealing lost faces, with its inherent humanity and drama was something people liked to read about, and some years later, as a further response to this phenomenon, I wrote Sleepers, which was an account of some of the more sensational finds in the art business, combined with some insights into both the process and the people who make them.

“A discovery requires three elements to turn it into a story: a discoverer with whom the reader can identify; the recovery or disclosure of something that matters; and a writer or commentator who can authoritatively communicate the discovery’s significance. The reason that we get asked regularly by newspaper editors for any discoveries is that they are a valuable news commodity. But it goes both ways. Not only do they sell newspapers, they are also one of the few ways that history and antique art can compete with celebrity, sex scandal and world wars for news headlines. In other words it allows art and history a safe passage into the hearths of middle England…”

THE ENTRANCE OF DAVID STARKEY

Above, Fig. 9, an ink drawing (in the collection of Professor Edward Chaney) of David Starkey made by the author to illustrate a profile article, “The apoplectic academic”, by D. J. Taylor, in the Independent on Sunday, 9 November 2001.

The Independent profile had tracked Dr Starkey’s pathway to celebrityhood:

“In the absence of the late Sir Malcolm Bradbury, whom can we safely characterise as Britain’s foremost media don? …by far the most successful performer in this glitzy but exhausting medium, delight of both the set-tethered TV audience and the browsers of bookshop history shelves, is the engagingly self-styled ‘academic thug’, David Starkey. Strictly speaking, to mark down the Tudor bruiser as a media don is a technical inaccuracy. Dr Starkey no longer teaches professionally, and the Cambridge quadrangles and the senior common room of the LSE have yielded up to ‘private research’ and solitary archival jaunts…

“For a bright, academically inclined teenager, the path from the local grammar school could lead only south, in this case to Cambridge, where he took a first in history and became a protégé of the leading Tudor historian of the age, Professor Geoffrey Elton. Starkey quickly decided that Elton’s view of history was sharply opposed to his own. Elton’s magisterial analyses of Tudor government rested on ideas of bureaucratic improvement. Starkey, on the other hand, was a personality man, seduced by the thought of titanic egos in conflict, ante-room punch-ups and backstairs intrigue. His first book, The Reign of Henry VIII: politics and personalities, was among other things a spectacular debunking of the Elton line. Sir Geoffrey is supposed to have taken this intellectual throwing over very hard…”

THE ROLE AND IMPORTANCE OF VISUAL EVIDENCE

In the catalogue’s Introduction, Starkey spoke with verve to the great importance – and the rarity – of visual evidence in historical studies:

“‘Henry VIII’, the lecturer declared, ‘is the only king whose shape you remember’. He then proved his point with a quick blackboard sketch, which deconstructed Holbein’s great full-length portrait into its elements of almost Cubist geometry. He made the body a trapezium, the legs splayed columns, the arms triangles, the head and neck a single massive cylinder, and finished off with the hat, which he drew with a flourish as a short acute angle to the head.

“We all laughed, for once un-sycophantically, as back then we were unused to visual aids and the joke was rather a good one. The time was 1964; the place a Cambridge lecture theatre; and the lecturer G. R. Elton. Elton was already the doyen of Tudor studies, but he spoke more truly than even he knew. For without the Holbein painting, how would we have an image of Henry at all? And without an image, how could Henry be memorable let alone world-famous? Would even, that is to say, the upheavals of the Reformation and the magnificent storyline of Henry and his Six Wives be enough if we could not envisage so vividly the male lead, let alone the female co-stars?

“I think not. For, speaking now as a television presenter as much as an historian, seeing is more than half of believing and almost all of caring. This means that Holbein’s painting is more than ‘the most enduring of all Henry VIII’s portraits – perhaps indeed the most memorable image of any English monarch’, it is Henry. It is, more than anything else, the reason that he fascinates us and that we study him; it is, I would go further, the beginning of his biography and the key to his mind. Once, it was poets who had promised eternal fame; with the Renaissance, painters were able to offer a more certain and enduring pathway to celebrity.”

In the 2007 Mould catalogue Dr Starkey made no further claims for the Windsor Anne Boleyn likeness. Dr Grosvenor, the catalogue editor, took the reins – and, later, part-credit for its acceptance by the Royal Collection, as in his 15 December 2011 Art History News post “Anne Boleyn regains her head”:

“…There used to be an article online in The Times detailing how research by myself and David Starkey had helped confirm the identity. But it has now disappeared behind the paywall. So below the jump, and online for the first time, is the article I wrote for an exhibition at Philip Mould in 2006 [sic] called ‘Lost Faces – Identity & Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture’, which was guest curated by David. The article was in the context of a fine but posthumous portrait of Anne we had borrowed from Hever Castle, Anne’s childhood home [Fig. 10, below, left]. The Royal Collection have found all the evidence compelling enough to change their cataloguing of the drawing (saying ‘this is a rare surviving portrait of Anne’), which is very pleasing. Let me know if you agree (or disagree)!”

The Times (“Nightgown clue turns Holbein’s unknown lady into Anne Boleyn”, 14 March 2007) had reported:

“Academics have now traced the inscription to Boleyn’s contemporary, Sir John Cheke, who began his career at the court under her patronage, before becoming secretary to Edward VI. A document of 1590 notes that Sir John inscribed numerous Holbeins for the King, helping to identify faces of royals and courtiers. Bendor Grosvenor, who carried out the research with David Starkey, the Tudor Historian, said: ‘Cheke was one of the brightest brains of the Tudor court. He would have known most of Holbein’s sitters, if not on personal terms, then at least visually’…Mr Grosvenor, who works at Philip Mould Historical Portraits, London, said: “it is inconceivable that she did not sit at some point for her portrait…’ The drawing appears to be a most unqueenly portrait, as the sitter is wearing a nightgown. Mr Gosvenor said: ‘Only a woman of the highest rank would have taken such a liberty in court circles.’ …The Royal Collection accepted that the portrait was of Boleyn.”

Among respondents to Grosvenor’s 2011 Art history News post, the author Claire Ridgway said on her Anne Boleyn Files blog: “…it is a very interesting read when compared with the thoughts of Eric Ives and Roland Hui…”

In a January 2000 post (“A Reassessment of Queen Anne Boleyn’s Portraiture”), Hui had noted that:

“The confusion surrounding the portraiture of Anne Boleyn was addressed by the art historian E. W. Ives in his biography of the Queen in 1986…In regard to the [Windsor] Holbein sketch, John Rowlands and David Starkey have proposed that the sitter was indeed Anne Boleyn… She is seen in three-quarters profile dressed in a furred robe over a chemise laced at the throat, and wears a simple undercap…Rowlands and Starkey have argued that such ‘undress’ on the part of this ‘royal’ sitter was a novelty of sorts to ‘relax’ the dictates of court etiquette. However, it seems unlikely that Anne with her much commented upon sense of style would have permitted herself to be depicted as such…Since her early days at court Anne Boleyn had a reputation in fine dressing in fashion-setting. George Wyatt, the grandson of Anne’s admirer, the Celebrated poet Thomas Wyatt, wrote that in her attire ‘she excelled them all’. Even those hostile to Anne Boleyn, such as the Elizabethan Catholic Nicholas Sander, admitted to the Queen always being ‘well dressed, and every day made some change in the fashion of her garments’…”

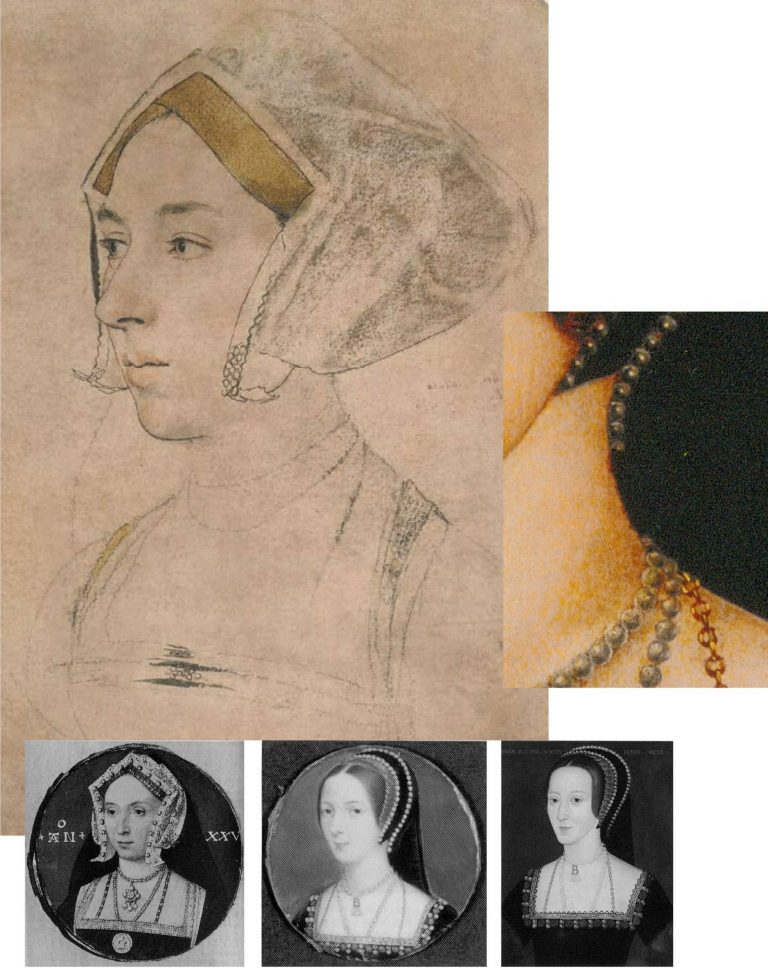

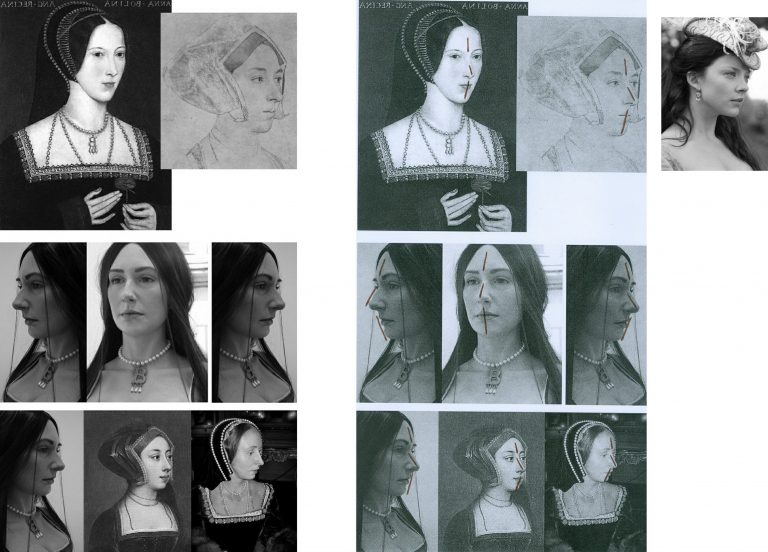

Above, Fig. 10: The photo-linkage that was carried across two pages of Anne Boleyn-ascribed works, as discussed by Grosvenor in the 2007 Philip Mould Gallery catalogue “Lost Faces – Identity & Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture”.

Note that, as seen above, in Grosvenor’s section of the 2007 Mould catalogue, the proposed Windsor sitter’s identification as Anne Boleyn carried a parenthetical question mark, and that nothing more was said of Cheke’s claimed identification of it than that it carried much weight – when, by the same token, so too must Cheke’s identification of the British Museum Anne – to repeat: because the two drawings’ sitters are, as everybody agrees, physically incompatible, if Cheke was right on one he had to be wrong on the other. In three decades of campaigning no one had established that Cheke had only endorsed the one drawing and not the other.

In “Lost Faces”, Grosvenor acknowledged his own restating of Rowlands/Starkey and strenuously endeavoured to show that Cheke had been proved right on almost every sitter’s identification. To two Ives-cited Cheke misidentifications he responded:

“We can surely forgive Cheke these errors, for the drawings date to Holbein’s first trip to England between 1526-8, well before Cheke came to Court.”

Ives had written:

“Most worrying of all, the portrait of Margaret Clements, More’s foster daughter, is identified as ‘Mother Jak’, Edward the VI’s nurse. Not only is it highly likely that Cheke knew Margaret – her husband John was erstwhile reader in Greek at Oxford, and Cheke was Regius Professor of Greek at Cambridge – but, as tutor to the future Edward VI, Cheke undoubtedly knew the real ‘Mother Jack’. Clearly, his authorship of the current [Anne Boleyn] identifications is highly questionable.”

CONCEALING GOITRES

Like Rowlands/Starkey, Grosvenor took the politically hostile witnesses’ accounts as firm corroborations of the Windsor drawing’s Anne. One such, Nicholas Sanders, alleged “a large wen under her chin” which she had attempted to conceal. Where Ives had rebutted Sanders’ testimony outright – “one can dismiss out of hand the arguments which seeks to link the [Windsor] sitter’s double chin and high collar with… a velvet mantle with a high collar to conceal a scrofulous neck” – Grosvenor countered: “We do know, however, from another contemporary source Sanders’ description of a swelling under her chin was probably correct.” A footnote to this claim cited Sir Roy Strong’s seminal work Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, but, as readers of Strong’s book will appreciate, while he had indeed identified a second observer (who claimed a grossly disfiguring wart and a swelling “resembling a goitre”), he, like Ives later, had dismissed both observers as hostile and, in Sanders’ case, of also being “too late to be taken as reliable evidence”.

DISCOUNTING AUTHORITIES

Although Grosvenor had cited both Strong and Ives in footnotes, on the former, he might have left an impression of support for his own position when Strong had not only dismissed the hostile witnesses’ reliability but had also noted that their accounts were incompatible (had failed to “harmonise very closely”) with the later painted pictures of Anne. Strong’s recognition of the testimonial value of the later paintings highlights the collective and abiding failure of the Windsor drawing’s successive champions to acknowledge and heed the evidential force of artistic images when, properly considered, such works of art themselves constitute primary documents as (truly) concrete manifestations of highly specific and personal artistic/intellectual productions. Grosvenor’s footnote on Ives’ 1994 Apollo article said no more of him than that he was one of the “authorities [who] have dismissed the validity of the [Windsor] ‘Anna Bollein’ inscription due to other inconsistencies and errors in the [Cheke] identifications.”

Ives had objected to more than the unreliability of Cheke’s identifications. He had made a methodologically rigorous visual and comparative appraisal of the available pictorial and graphic records that would have done a trained art historian proud. He rejected the two Holbein Anne Boleyn drawings as likenesses of Anne – but not equally so. While recognising that a case can be made for each, he pointed out that where the British Museum Anne looks the part – “The love of Henry VIII’s life should have looked like that” – against that, the “curious undress” of the Windsor sitter suggested that rather than being a queen, “A far more likely explanation of the implied intimacy would be a link between artist and sitter”. The combined facts that Hollar had chosen to engrave the now British Museum Anne and not the Windsor Anne, and the latter’s intimate garb “should make further discussion of the Windsor drawing unnecessary”.

Having disregarded an entire tranche of historically adjacent paintings of Anne Boleyn, Grosvenor, following Rowlands and Starkey, subscribed to the veracity of the widely recognised malice on alleged facial disfigurements as reliable corroborations of the double chinned, heavy jawed sitter with the (disqualifying) fair-not-famously-dark hair in the Windsor drawing: “The chin in the drawing is perhaps swollen, and would accord with Anne’s alleged misfortune” – and this, despite Ives’ objection that the Windsor drawing sitter’s “almost bovine impression” was “fatally contradicted by the medal’s long assertive neck and its total absence of a double chin.” (See Fig. 11, below.)

ROYAL HEADWEAR

Above, Fig. 11: Left, the British Museum-owned 1534 Coronation medal; centre, top, the British Museum “Anne Boleyn” Holbein drawing (mirrored) and, bottom, the Windsor “Anne Boleyn” Holbein drawing; right, the Hever Castle Anne Boleyn painting loaned to the 2007 Mould Gallery exhibition. Although the medal is certainly damaged, pace Rowlands/Starkey, it clearly shows Anne to be attired and be-jewelled, as in the B.M. drawing. The sitter in both wears a “gable hood” – which fashion would be superseded within Anne’s own reign by the “French Bonnet” fashion, as found in the Hever paintings. In the above formation of images, where the similarities of costume and composition arc from the medal through the British Museum Anne to the painting, the Windsor drawing, by contrast, acts as a circuit breaker between the medal and the painting.

Where Grosvenor made no comment on Strong’s recognition of the wider testimonial force of artistic depictions, on the testimony itself he faced both ways, declaring on the one hand that “The author does not believe that the [Windsor] likeness… is totally dissimilar to the later portraits of Anne, such as that exhibited here [the Hever Castle portrait at Fig. 11, above, right]”, while, on the other hand, dismissing the testimonial power of the later portraits en masse:

“As with all posthumous portraits, however, they are subject to the historical, political, and visual prejudices of those who created and commissioned them. They cannot give us an accurate picture of what Anne really looked like”.

THE PERILS OF DISAVOWING PICTORIAL TESTIMONY

Above, Fig. 12: Left, as shown in Part I, appraising and evaluating artistic productions is not a mystical or even an entirely subjective exercise. As seen above, left, while the Windsor sitter was shown in nightwear and sans jewellery, Holbein’s British Museum sitter was fully dressed and with indications of three rows of necklaces. Many paintings of Anne show her in precisely such dress and so be-jewelled – jewellery which often included her initial “B” as a suspended centrepiece. Elsewhere in the Mould catalogue, Grosvenor accepted the testimonial power of jewellery when defending Cheke’s reliability on a Holbein sitter that had been doubted – “The Lady Mary after Queen”:

“But the Holbein drawing certainly is Mary. A study of the jewellery allows a positive identification to be made…”

Above, right: with the British Museum Anne Boleyn drawing, not only does the indicated jewellery clinch the status of the drawing as the precursor to the paintings, it was (as previously shown) further possible to demonstrate the clear derivation of a particular painting (also at Hever Castle) from the drawing.

Above, Fig. 13: In the above sequence it is possible to see a morphing familial relationship in the faces in which, notwithstanding stylistic changes, a progressive sequencing of slight rotations of the head from the original near profile drawing (in which the nose fractionally overlapped the cheek contour and the edge of the gable hood) progresses towards a more frontal face in which the eyes in the second Hever Castle Anne painting (here mirrored) turn to confront the viewer.

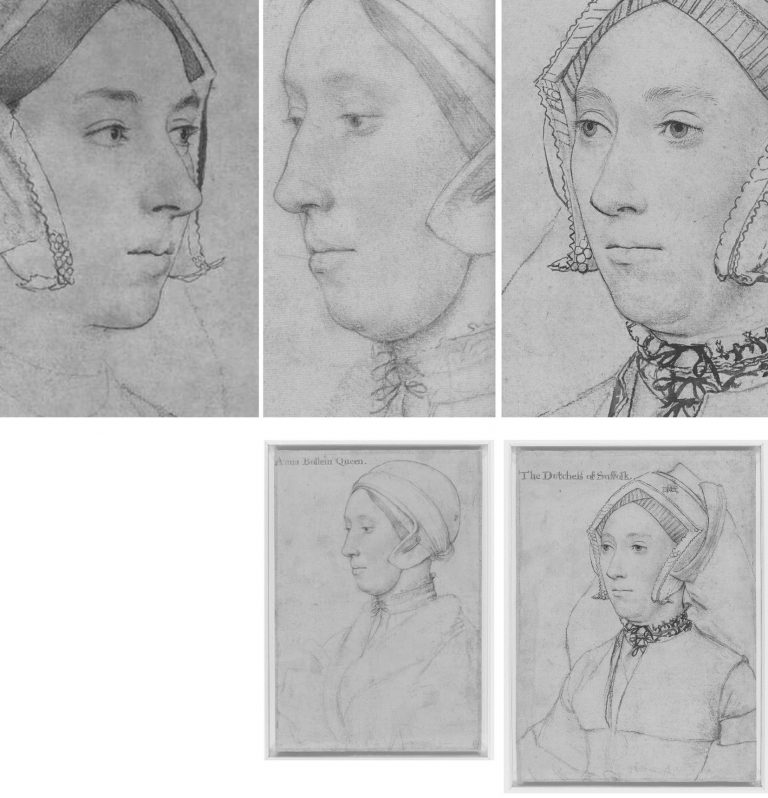

DOUBLE CHINS AND CHEKE’S RELIABILITY

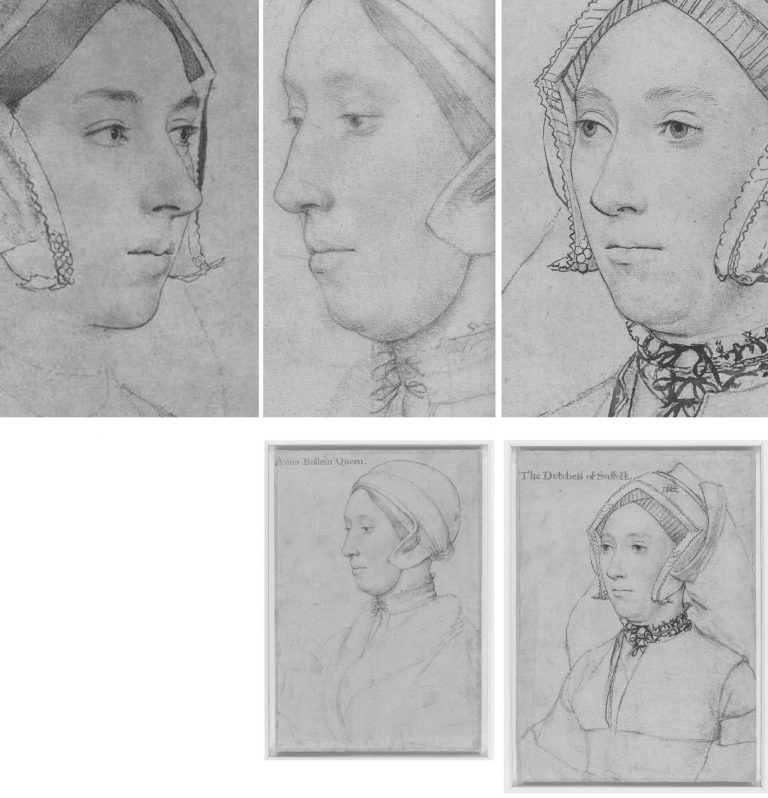

As shown in Part I, the features of the Windsor sitter markedly better resemble those of the ascribed Duchess of Suffolk (Fig. 14, below) than those of the British Museum drawing. As mentioned, when Starkey paired with Rowlands in the 1983 Burlington Magazine article hopes of a visually supported case for the Windsor “Anne Boleyn” were dashed, and again, with Starkey/Grosvenor, after three decades, no direct visual comparison of the rival Holbein drawings was offered to readers.

Above, Fig. 14: Left and centre, the British Museum and the Windsor Holbein “Anne Boleyn drawings; right, the Royal Library’s “The Dutchess of Suffolk”. Note, in the case of the British Museum Anne, a nostril that is markedly larger than the two similarly shaped nostrils on the other two drawings.

Collectively, Rowlands, Rowlands/Starkey, and Starkey/Grosvenor had all failed to acknowledge that the sitter in the Windsor drawing was not the only double-chinned, high cheek-boned lady wearing a (potentially) goitre concealing, neck-tied chemise in Holbein’s drawn portraits. As seen above, Holbein’s later inscribed portrayal of Katherine Brandon, the “Dutchess of Suffolk”, bears not only another double chin but an almost identically laced and tied high-necked garment. Were both sitters scrofulous? Or might they have been one and the same person?

CODA: AGE CUTS BOTH WAYS

Ironically, an unsuccessful attempt was made in the Lost Faces exhibition to re-assign the identity of the Duchess of Suffolk’s sitter to an earlier wife and to count the proposed switch as another Mould and co. “discovery”. Grosvenor raised the reliability of the ascribed Duchess of Suffolk sitter:

“…there has been some confusion about which ‘Dutchess of Suffolk’ Holbein shows, an issue raised below in some detail by Alisdair Hawkyard.”

Hawkyard, possibly in emulation of Starkey on “Ormond”, wrote:

“One of the drawings of a sitter whose identity has been doubted is inscribed ‘The Dutchess of Suffolk’. She has been identified as Catherine Willoughby born c. 1519 who in September 1533 married her guardian Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. The woman depicted is more mature than Catherine would have been had she sat to Holbein before his death in 1543. The sitter’s greater maturity suggests that she was Suffolk’s third wife Mary who died on 25 June 1533. Mary, Henry viii’s younger surviving sister, had married Suffolk in 1515 while still in mourning for her recently deceased husband King Louis xii of France and without the consent of either her brother or the new King of France, Francis I. The physiognomy of the Duchess accords with what is known of her appearance…”

If Hawkyard’s objection seems a fair one, it would follow that the very similar-looking Windsor sitter is also too old to be Anne who, on Ives’ reckoning, was thirty-one when Holbein began his second visit to England and thirty-five when executed. Grosvenor dismissed the British Museum drawing’s sitter on grounds of age: “Alas, this pretty sitter is too young to be Anne”, adding, “The drawing has been convincingly discounted by, among others, John Rowlands”. (Which others? – the people who “apparently” had “generally accepted” Rowlands’ identification?) On Anne’s age, Margot Robbie, who played Barbie in the recent film, is thirty-three. Lily James is thirty-five. Had the Royal Collection accepted the Grosvenor/Mould Gallery’s proposed re-identification of the Duchess of Suffolk sitter, it would, of course, have spoken further against Cheke’s reliability.

Despite Grosvenor/Starkey’s reported claims to have “traced” the Windsor drawing’s provenance to Cheke and to have discovered a document of c. 1590 which noted that Cheke had inscribed “numerous Holbeins for the King”, as mentioned above, there had been no tracing or discoveries because the claims made had derived directly from (and added nothing to) Parker’s 1945 account. Viz:

“…The basis, of course, for all such inquiry is the evidence provided by the inscriptions on the drawings themselves, or to be more exact, by the inscriptions that appear on sixty-nine of the total of eighty-five, the further sixteen having remained nameless. At this point we must revert to the Lumley inventory of 1590, and complete the quotation of that vitally important entry with the further information that the names were ‘subscribed’ to the drawings by ‘Sir John Cheke, Secretary to the Edward the 6.’ One of the most learned men of his day, Cheke, then in his twenties, was summoned to Court in July, 1542, to succeed Richard Cox as tutor to Prince Edward. On the newcomer’s arrival, therefore, Holbein himself was still on the scene, and the circle of his more recent sitters still about him. That Cheke must have had personal contacts with many of them is beyond doubt. It follows that if the names now inscribed on the drawings correspond, as presumably they do, with Cheke’s identifications referred to in the inventory, they have abundant claim to interest and attention, though not, of course, to blind faith. It is demonstrable that their accuracy is not infallible, nor can the date of their recording have been otherwise than belated.”

Moreover, respectful as he had been of Cheke’s authority, Parker had rejected the Windsor drawing’s identification as a portrayal of Anne Boleyn:

“The inscription is certainly incorrect, the features showing no resemblance whatever with the well authenticated drawing of Anne Boleyn in Lord Bradford’s [now the British Museum’s] possession.”

SUGGESTIONS BECOME FACTS

Grosvenor’s counter to Parker’s dismissal of the Windsor “Anne” comprised nothing more than appeals to the authority of his predecessor-partisans’ authority:

“The present author, however, here restates an earlier suggestion that the sitter is, in fact, Anne Boleyn – Originally suggested by John Rowlands and David Starkey in ‘An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein’s portrait of Queen Anne Boleyn”, Burlington Magazine, CXXV (1983).”

Cheke was personally pressed into Grosvenor’s service:

“On simple probability alone, the chances of the [Windsor] inscription being erroneous are slim. And, as mentioned above, Anne is one of the sitters Cheke was least likely to get wrong.”

Grosvenor’s 2007 contention was thus, like that of Rowlands/Starkey in 1983, yet a further sleight of hand: Cheke cannot be held to have ascribed the Windsor drawing alone, because, on the same historical record, he had also ascribed the now British Museum drawing. The Royal Collection switched the Anne Boleyn identities in error and on a case lacking either scholarly merit or visual credibility – this truly was a spurious discovery.

Michael Daley, Director; 31 May 2024

May 31, 2024 | Categories: blog | Tags: Albrecht Durer, Anne Boleyn, ArtWatch UK, Bendor Grosvenor, Charlotte Bolland, David Starkey, Duchess of Suffolk, Emma Pooley, Eric Ives, Francesca Kaes, Francesco Bartolozzi, Hans Holbein, Henry howard, Hever Castle, Jane Seymour, John Rowlands, jonathan Richardson, Kate Heard, Mellon Centre, Michael Daley, Paul ganz, Philip Mould, Prof Edward Chaney, Royal Drawing school, Sir John Cheke, Sir Karl Parker, Susan Foister, The Royal Collection, The Royal Library, Warwick Castle | Leave A Comment »

Sex, Trigonometry and Anne Boleyn’s Recovered Likeness

Art can suffer many injuries and indignities. The worst of these, short of outright destruction – but also irreversible – is restoration damage. Misattributions corrupt and debilitate oeuvres and can mask restoration injuries – but they can be corrected. In portraiture depicted sitters can be misidentified but, again, these can be corrected. When presented to the world, injurious restorations, misattributions and misidentifications alike are commonly trumpeted as “discoveries”. Such discoveries, as in the misidentification examined here, can be claimed without supporting evidence or, even, against strong contra-evidence.

ANNE BOLEYN’S NEW HEAD

On 14 March 2007 the Daily Mail (“Finally historians can give Anne Boleyn her head back”) reported:

“A Holbein drawing has been revealed as the only portrait of Henry VIII’s second wife Anne Boleyn. The c.1530 picture carries Anne’s name but other evidence suggested this was an error. Now expert Bendor Grosvenor and historian David Starkey have traced the inscription to her contemporary Sir John Cheke, confirming she is indeed the subject.”

Four years later the claimed confirmation of the Royal Collection’s “Anne Boleyn” drawing graduated into “certainty” on Bendor Grosvenor’s 15 December 2011 Art History News post “Anne Boleyn regains her head”:

“This isn’t ‘news’ as such, but in a foray into the Tudor realms of Twitter last night I mentioned the drawing of Anne Boleyn by Holbein in the Royal Collection. I said that although in the past the identity was doubted by art historians, the sitter was now catalogued with certainty as ‘Anne Boleyn’, as you can see on the Royal Collection website…”

THE TRUE ANNE BOLEYN LIKENESS

Since 1977, the dispute over Anne Boleyn’s likeness has turned on two Holbein portrait drawings of equal artistic merit and provenance strength but of manifestly different sitters. One drawing is in the British Museum, the other is in the Royal Library at Windsor (see Fig. 1 below). While the Windsor drawing’s advocates claim “certainty” on their “Anne Boleyn” identification, both drawings bear written Anne Boleyn ascriptions derived from the same largely reliable historical source and the British Museum drawing had been considered the true likeness for many centuries. How, then, had the switch occurred? The now protracted Anne Boleyn Identity Literature discloses the Royal Collection’s acceptance of a campaign which had eschewed all use of the most illuminating art critical tool – the photo-comparison. In this switch of identities, Art had been denied its own voice as words trumped the intrinsic – and markedly contrary – visual testimony of images.

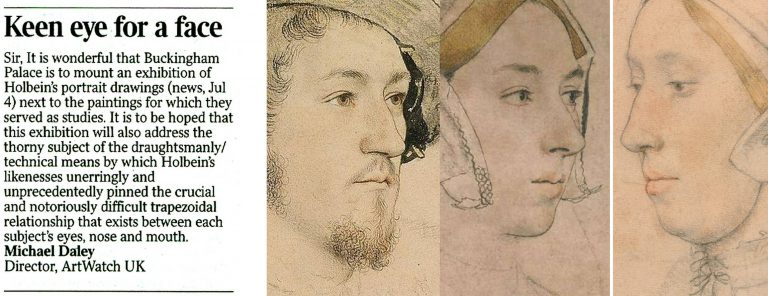

EYES, NOSES and MOUTHS: GIVING A VOICE TO HOLBEIN

In a letter to the Times (5 July 2023) we had hoped a forthcoming Holbein portrait drawings exhibition might address the drawn method by which Holbein unerringly fixed the characteristic trapezoidal relationships between a sitter’s eyes, nose, and mouth.

Above, Fig. 1: Left, ArtWatch UK letter; centre, the British Museum Holbein drawing formerly said to depict Anne Boleyn; right, the Royal Collection Holbein drawing now said to depict Anne Boleyn.

The British Museum Anne Boleyn drawing was not in the Buckingham Palace exhibition Holbein at the Tudor Court and therefore was not discussed. The Royal Collection Trust’s Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings, Kate Heard, speaks in the catalogue of Holbein’s “sensitive and life-like” depictions that “bring us face to face” with key Tudor players. The portraits are addressed in terms of social history and patterns of patronage, as in Holbein’s rise from foreign itinerant to court artist, and with Heard wondering whether, as the only artist of his day to possess a horse, Holbein travelled to his sitters, or they to him. His drawing method was discussed as “taking likenesses” and on the frequency with which his chalk drawings had been reinforced with ink in possible preparation for transfer as “patterns” for painted portraits.

Heard’s “taking likenesses” was a telling phrase because distinctions are commonly drawn between making drawings and taking photographs and because Holbein’s depicted facial features can seem as reliably fixed as in any photograph.

Above, Fig. 2: Durer’s depiction of a method of capturing traced outlines and features on a pane of glass.

The scholar who had held the formerly Bradford family, now British Museum, Holbein portrait of Anne Boleyn to be the true likeness (Fig. 1, above, centre) was K. T. Parker in his seminal 1945 book The Drawings of Hans Holbein in the Collection of His Majesty the King at Windsor Castle. Parker succeeded Kenneth Clark as Keeper of the Department of Fine Art in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and was Keeper of the whole museum from 1945 until his retirement in 1962. His high reputation as a connoisseur is said to have been laid when working in the British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings with A. E. Popham and Campbell Dodgson.

THE RELIABILITY OF INSCRIPTIONS

In Parker’s book, the Windsor Royal Library drawing’s inscribed identification as “Anna Bollein Queen” (Fig. 1, above, right) was bluntly dispatched:

“The inscription is certainly incorrect, the features showing no resemblance whatever with the well authenticated drawing of Anne Boleyn in Lord Bradford’s possession”.

Parker drew a distinction between “two kinds” of evidence – “pictorial” and “literary” (or visual and documentary) and was duly alert to the importance of both. As will be examined separately, he also advanced a pictorially sophisticated hypothesis that Holbein, like Durer at Fig. 2 above, might have fixed the essential features of his sitters by tracing them onto a pane of glass and transferring the resulting image to paper. Here, we consider how and why visual records failed to receive due critical consideration when the Anne Boleyn sitters’ identities were switched.

A REVISIONIST CHALLENGE

In 1977 John Rowlands, the then deputy keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum (and, later, Keeper from 1981 to 1991), challenged the Anne Boleyn identification in the Parker-endorsed drawing. The “demotion” was curiously, if not inappropriately executed. First, it was made not in a scholarly journal – which could have facilitated a correspondence – but in the museum’s own YEARBOOK No. 2 (“A portrait drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger”). Second, it was not advanced on its own merits but was slipped within a commemorative article on the British Museum’s recent acquisition from the Bradford family of its landmark Holbein drawn portrait. The article itself carried just three photographs (as shown below) and with none of the Royal Library drawing being espoused as the new, true Anne Boleyn likeness.

Above, Fig. 3: The three illustrations to Rowlands’ British Museum Year-Book II article. There was also a full colour plate of the newly acquired drawing.

Rowlands acknowledged the new acquisition as an outstanding drawing that had traditionally been held to be of Queen Anne Boleyn (Paul Ganz,1937; Karl Parker 1945). He offered no artistic grounds for his “de-identification” of the drawing’s sitter – indeed, as shown below, he celebrated the drawing’s supreme artistry – and he made no suggestion of another likely or possible sitter. The relative visual authority/plausibility of the two radically different depictions of the same historical figure was not examined. Rowlands’ sole objection to the British Museum’s own drawing was documentary – that its Anne Boleyn ascription could be traced no further back than 1649 when in the Earl of Arundel’s collection and where it was copied in Wenceslaus Hollar’s etching (Fig. 3 above, top left).

The objection seemed something of a pedantic contrivance: both the etching and the drawing bore an inscription which identified the sitter as Anne Boleyn and gave the date of her beheading – “Anna Bullen decollata fuit Londini 19 May 1536”. On the general authority of the inscriptions on Holbein’s drawings, Parker had reported that of the eighty-five Royal Collection Holbein drawings sixty-nine bore written inscriptions from an inventory made in 1590 to which the names of the identified sitters had been “subscribed” by “Sir John Cheke, Secretary to King Edward the 6th”. Cheke had died in 1557. The British Museum’s new drawing had been part of the Royal Collection’s Holbein holdings after the artist’s sudden death in 1543 from the plague. Most inscriptions on Holbein’s portraits thus originate from the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Parker held that because Cheke had had direct contact with many of the drawings’ sitters, his subscribed names enjoyed “abundant claim to interest and attention, though not, of course, to blind faith.” The eventual acceptance of Rowlands’ misidentification by the Royal Collection evidently rested on a claimed near-infallibility of Cheke’s recorded identifications – even though he had evidently given the same sitter to two incompatible drawn portraits.

IN AND OUT OF HISTORY

Rowlands, who would later be supported by two historians (David Starkey and Bendor Grosvenor) and opposed by a third (Eric Ives, author of an acclaimed Anne Boleyn biography), acknowledged “a strong likelihood” that the Bradford/BM drawing had been incorporated in the famous “Great Booke” of bound Holbein drawings and had subsequently been removed from it:

“How and when the ‘Anne Boleyn’ sheet became separated from the rest is unknown, but this probably occurred after the death of the earl of Arundel in 1646”.

Rowlands also held that although the British Museum drawing had been incorporated within the famous book, such incorporation was no guarantor of pedigree: the Windsor group “undoubtedly contains drawings which are not by Holbein”. Such a consideration would, of course, apply to all works bound in the book. Parker had said in 1945 that: “The Windsor series certainly contains extraneous matter, but the only drawing known to be incorporated at a later date is the so-called ‘Amelia of Cleves’…in the eighteenth century”. Rowlands spoke too of “extractions” from the book, with the first having probably begun “around 1630″. With the British Museum drawing, he said its date of extraction was unknown but had “probably occurred after the death of the Earl of Arundel in 1646” and “probably in the reign of Charles II [1660-1685]”.

A CLASH OF DATES AND AN ARISTOCRATIC VILLAIN

Against his own “probablys”, Rowlands cited and accepted a detailed account of how the now British Museum drawing had been stolen by the Bradford family when the great book was owned by Jonathan Richardson, senior. Rowlands quoted Richardson’s son’s account of the theft in full:

“The Original of this Drawing, by Holbein, of his finest style & most Capital, the Old E[arl] of Bradford cheated my father of Thus. When he was confined with gout, a little before his Death, He sent request to my F[ather] that he would lend him a Book of Drawings to Divert him; w[hi]ch my F[ather] compl’d with. The E[arl] sent him back the Book in a few Days, but without this Drawing. My F[ather] went immediately to wait on him, & found the Drawing hanging by the Bed side in which he lay, in a Frame & Glass. There was other Company in the Room, so my F[ather] could not claim it at that time; but look’d several times at ye Drawing, stedfastly, & lookd at my L[or]d. My L[or]d stood it, discoursing with him, quite unconcerned; & in two or three days failly sneak’d out of the world, & kept the Drawing. My F[ather] could not claim it afterwards of his Heir (L[or]d Torrington I think) without accusing Bradford of a most infamous piece of Villany, of which he had no witness.”

Rowlands thought the Earl was likely to have been Henry Newport who died in 1734 and added “since then this drawing has been in the possession of the Earl’s descendants”. Parker (whose Holbein scholarship is considered “exemplary” by Susan Foister) had stated that the great book was “broken up” in 1727 when back in royal possession and that by 1728 the drawings had been glazed, framed, and displayed at Richmond Lodge. The Bradford theft must therefore have occurred before the book returned to Royal ownership, the date of which Parker said remains unknown in a period “so full of problems”.

Rowlands acknowledged that after Hollar’s 1649 printed copy, “all representations of Anne Boleyn, whether they were painted or engraved, were based on the Bradford drawing, right through the next two centuries.” He did not ask why this had been so or wonder why no such comparable copies had been made from the Royal Collection “Anne Boleyn” drawing he was championing as the sole and true record of Anne Boleyn’s likeness. On Rowlands’ account, the theft of the drawing had clearly left the Richardson family highly aggrieved. At the time of the theft, Jonathan Richardson senior had owned both inscribed Anne Boleyn drawings and had made a pencil copy of the British Museum version (Fig. 13, below). Similarly, when the Earl of Bradford had both inscribed “Anne Boleyn” drawings bound in the (loaned) book before him, he stole the now British Museum version and not the one that returned to the Royal Collection. As Eric Ives would later point out, when Hollar had had the the option of copying either of the Anne Boleyn-inscribed Holbein drawings, he opted – or was instructed – to copy the now British Museum likeness.

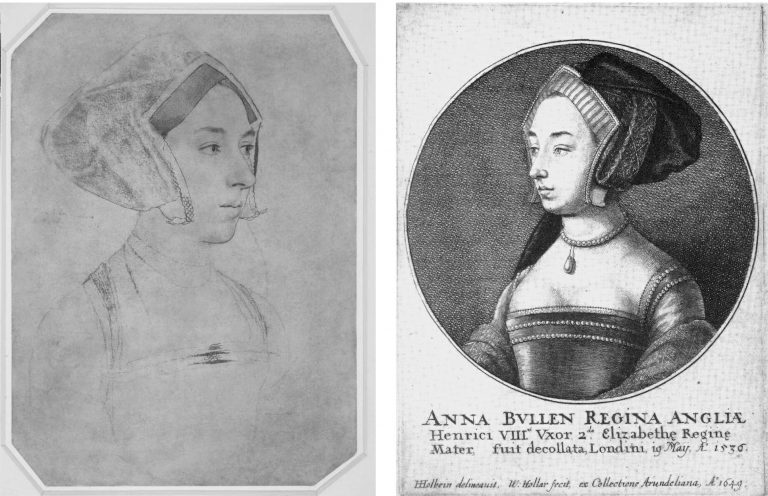

Above, Fig. 4: Left, the Bradford/BM Holbein Anne Boleyn drawing and, right, the Hollar copy of 1649. Hollar had of necessity resorted to a degree of invention with the costume and jewellery – and he showed only one of the three necklaces indicated on the Holbein drawing. His seemingly strengthened shading around the cheek, jaw and neck might indicate a subsequent loss of chalk shading on the drawing itself (see Fig. 13, below).

A SOLE RELIABLE RECORD

Rowlands noted that the only securely known contemporary likeness of Anne “is the medal struck to commemorate her coronation in 1533” but which, he said, is too worn to give any indication of her features (see Fig. 5 below). Given his unsteady and visually unsupported 1977 account, it might seem timely to consider the expanded and invigorated joint Rowlands/David Starkey 1983 Burlington Magazine article, but note should first be made of the methodological and visual shortcomings in Rowlands’ solo challenge to Parker – on the (slim) authority of which all subsequent accounts rested. Rowlands had not shown the drawing he was espousing. He had not shown the relationship between the two rival “Anne Boleyn” drawings. He had not shown how the two drawings respectively related to the medal’s likeness as the only securely dated contemporary image of Anne. Nor had he claimed any resemblance of the Windsor drawing to either the medal’s image of Anne Boleyn or any of the later painted portraits of her. His case comprised little more than a visually unsupported expression of a contrary professional opinion – an unsubstantiated glancing swipe, as it were, from a rising mid-career scholar to one who had retired fifteen years previously.

Fig. 5 above. When the Royal Collection drawing (left) and the Bradford/B.M. drawing (right, here mirrored) are seen with the medal it shows markedly more kinship with the latter drawing.

That scholarly prudence and diligence is required on these matters was recognised in Susan Foister’s 2004 Mellon Centre/Yale published monograph Holbein & England:

“There is every reason to suppose that Holbein might have painted Anne’s portrait, but no clear evidence that he did… No portraits of Anne Boleyn are mentioned as such in contemporary inventories, and official images of her are unlikely to have circulated after her execution…The only contemporary likeness of Anne appears to be that in a medal, showing her thin-faced and in a gable headdress; later painted portraits echo this image, and show her wearing jewellery with the initials A and AB…”

Above, Fig. 6: This photo-comparison, carried in Foister’s 2004 Holbein & England, showed the great discrepancy between the Rowlands-claimed Royal Library near-profile portrayal of Anne Boleyn (above left) and one of the many subsequently painted three-quarters view portraits like that in the National Portrait Gallery (above right) and at Hever Castle (as in Figs. 9, 10, and 13, below.)

THE WRONG HAIR COLOUR

Foister objected that the Windsor “Anne Boleyn” drawing (see Figs. 1, 14 & 18) “shows a sitter with fair hair and quite a different appearance to the [painted] portrait in the National Portrait Gallery in which the dark-haired sitter wears a pendant B.”

A seeming attempt to defuse problems arising from the Royal Collection’s acceptance of the fair-haired Windsor “Anne Boleyn” presently appears on its website:

“A portrait drawing of Anne Boleyn (c.1500-1536) on pink prepared paper. She is shown bust length in profile facing to the left. She wears a fur collar and linen cap… Although the identification of the sitter has been doubted, her informal dress and the presence of an inscription based on an identification made by Sir John Cheke have been cited as convincing evidence that the sitter is the queen (see, for example, John Rowlands and David Starkey in the Burlington Magazine, February 1983, pp. 90-2)…

“Abrasion has removed some pigment from the sitter’s hair meaning that it may now appear lighter than it did when the drawing was made. The sitter’s eyes are brown…”

Certainly, as Parker had noted, the “Windsor Holbeins have suffered in both ways from rubbing and reworking, and the fact has long been known and all too emphatically stressed.” The recorded superimposition of oiled paper for the purpose of making tracings (for engravings) can only have had deleterious effects on drawings made largely of chalks. Nonetheless, one must wonder what kind of precisely selective abrasion might have left a sitter’s eyes brown while turning her dark brown hair fair.

In her 2006 Tate Gallery catalogue Holbein in England, Foister cast doubts on both “Anne Boleyn” drawings – but not equally so. Of the British Museum drawing, and echoing Rowlands/Starkey: “The identification as Anne Boleyn arose when the drawing was in the Arundel collection and was etched by Hollar in 1649. It appears to have been based on a superficial similarity to portraits which have a reasonable claim to represent Anne… Whether Holbein portrayed Anne remains an open question: a drawing at Windsor (Parker 63) inscribed with her name shows a fair-haired woman whose appearance differs greatly from the painted portraits.” Of the British Museum drawing Foister said the dress is “similar to that of representations of those of the More family but also those of higher status: the jewels on her hood and on her bodice indicate that she might have been a member of a noble family…”

PICTORIAL TESTIMONY

What seems not to have been appreciated by any supporters of the Royal Collection drawing is that in the absence of a Holbein painted portrait of Anne – or an evidently intermediary work – adjudications between the two rival and incompatible “Anne Boleyn” drawings can only proceed on an examination of their respective correspondences with both the historically secure and dated medal and the many later painted depictions of Anne. With Anne long deceased, the later paintings had to have derived from something already painted or drawn, so the question is: which of the rival drawings is a better fit with the surviving Anne Boleyn depictions. Given the virtually complete concordance of design in Holbein’s portrait drawings and paintings (Figs. 10 and 11), appraising and comparing the now rival “Anne Boleyn” drawings with the medal and the depictions of Anne that followed her 1536 execution and the 1547 death of Henry VIII, is not only germane, it becomes, in the absence of “literary” records, of the pictorial essence – and thus is, pace Foister, a far from superficial exercise.

For example, the three rows of jewellery indicated in shorthand at the neck of Anne in the British Museum drawing are also found in completed form on the necks of both the National Portrait Gallery and Hever Castle paintings of Anne (see Figs. 7 and 11 below). Further, while this now officially discounted Holbein drawn likeness of Anne had either directly determined or – somehow – anticipated a crucially important and distinctive feature common to both types of the later painted portraits of Anne, the upgraded Royal Collection “Anne Boleyn” drawing found no echo in either type of the many later paintings.

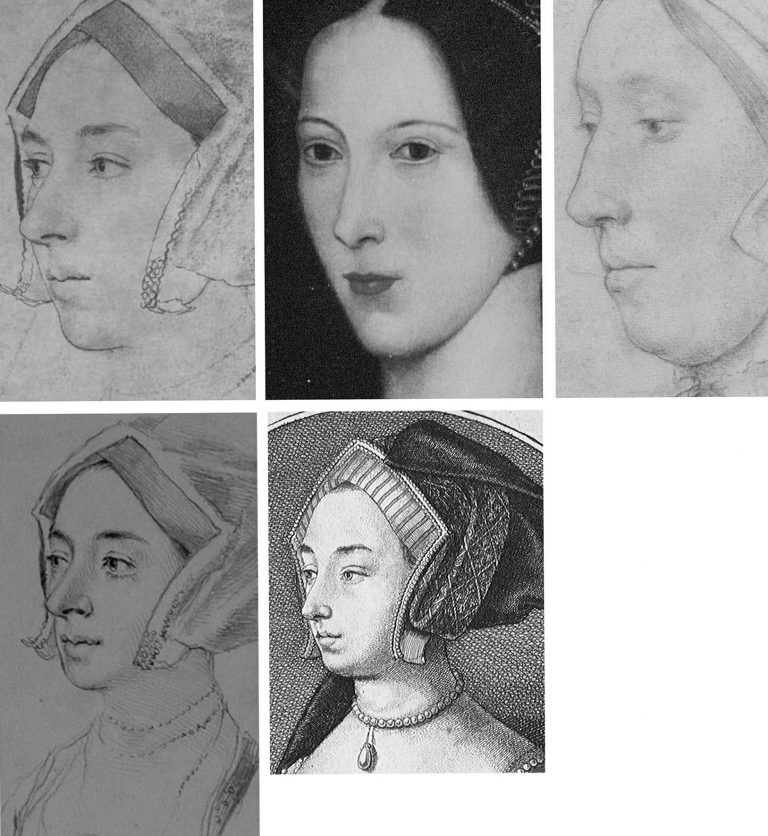

Above, Fig. 7: Top, the British Museum Anne Boleyn (mirrored); right, inset, a detail of the Hever Castle Anne Boleyn painting; bottom row, painted portraits of Anne by Lucas Horenbout (in the gable hood type) and (in the French bonnet type) by John Hoskins, and anonymous.

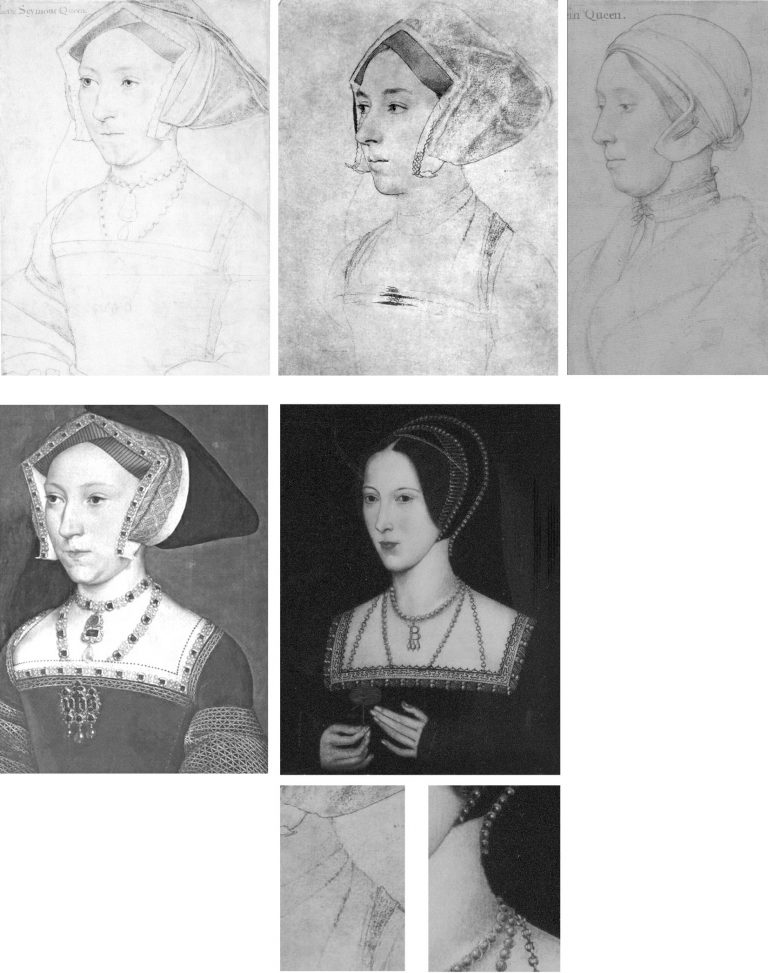

THE MEDAL IN THE ROOM

The only securely surviving – and dated – contemporary likeness of Anne is on the damaged 1534 commemorative medal. The medal itself, however, will have derived from a drawn design or model – but by whom? Given his designs for jewellery and other precious objects, might Holbein be considered in this regard?

Above, Fig. 8: Left, the British Museum-owned 1534 medal; second and third left, respectively, the British Museum and the Windsor Holbein “Anne Boleyn” portraits; right an 18th century engraved copy by Francesco Bartolozzi of the Windsor “Anne Boleyn”. Prints of the Bartolozzi copy can be obtained from the National Portrait Gallery – where they are described as “Unknown woman, formerly known as Anne Boleyn”. Because of the Bradford family’s theft, there is no comparable Bartolozzi copy of the now British Museum Anne, but it might be noted that Bartolozzi showed the Windsor sitter to be fair- not dark-haired and, thus, any abrasion to the sitter’s hair must have preceded this record.

Above, Fig. 9: A possible chronological migratory sequence of depictions and motifs spanning one hundred and fifteen years. From left to right: the British Museum’s Cheke, Ganz, and Parker-ascribed Holbein drawing (here mirrored); the 1534 commemorative medal; third left, the Hever Castle, late 16th century English School oil-painted portrait of Anne Boleyn; right, the 1649 Hollar engraved copy of the British Museum drawing. It might be proposed that the British Museum drawing more likely predated the 1534 medal (struck just two years before Anne’s execution) and that it might, with its gable hood and indications of jewellery, have served in mirrored form as something of a guide to the medal maker.

Above, Fig. 10: The extremely close design relationship between Holbein’s drawings and paintings can be seen (left column) in his drawn and painted portrayals of Jane Seymour. Such constancy would be expected also in a Holbein painting of Anne but, given either that one was never made or that none has survived, we must therefore consider from whence the (above, centre) Hever pattern of portraits might have sprung. Clearly, in terms of costume and physiognomy, it could not possibly have derived from the Windsor drawing – whereas, as seen at Fig. 7 and above here, the triple necklaces motif had migrated from the British Museum drawing to the later paintings while the Royal Collection linen cap and fur-collared nightwear costume would seem to have influenced no other work.

Above, Fig. 11: In the left-hand column we again see the absolute unity of design in Holbein’s drawing (top) and painting (bottom) of Jane Seymour. In the second and third columns we see degrees of kinship between Holbein’s British Museum portrait of Anne Boleyn (top row) and, below, with the two types of the later painted portraits, as found formerly at Nidd Hall, now privately owned, and at Hever Castle.

Above, Fig. 12. While all agree that the rival “Anne Boleyn” drawings (top, left and centre) could not have been made from the same person, it has not been remarked that with the Windsor “Anne Boleyn” (centre column), the general set of the face, the disqualifying double chin, and, the greater age of the sitter, find correspondences in the Royal Library’s “The Dutchess of Suffolk” (right hand column) – which include an almost identically tied, high-necked chemise. (An unsuccessful attempt was made to re-assign the identity of the Duchess of Suffolk’s sitter to an earlier wife and to count the proposed switch as a “discovery” in the 2007 Philip Mould Gallery Lost Faces exhibition.)

Fig. 13, above. In terms of likenesses, the late sixteenth century painted portrait at Hever Castle (above, top, centre) has common traits with the BM drawing (mirrored, above, top left) but none with the Windsor drawing (above, top, right) – other, that is, than a sharply drawn edge to the lower face caused, doubtlessly, by tied bonnets. As seen at bottom left, a (mirrored) pencil copy of the Bradford/BM drawing held in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and now attributed to Jonathan Richardson senior, suggests that more supplementary chalk shading might formerly have articulated the head/neck relationship on the Bradford/BM drawing – and, as seen at bottom, centre, above, (and at Figs. 3 and 4), the Hollar copy of 1649 had indicated by tonal variations an implicitly continuous line of demarcation between the lower face/jaw and the neck.

HOLBEIN’S CAPTURED LIKENESSES AND THEIR ORIENTATIONS

Above, Fig. 14: Top, The British Museum and Royal Collection “Anne Boleyn” Holbein drawings; bottom, left, Holbein’s “Simon George”, which carries an inscription “S. George of Cornwall”; bottom, right, Holbein’s “Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey” (detail).

Holbein possessed a seemingly effortless ability to draw heads from any position – in one perspectival tour de force, John Poyntz (in the Royal Collection) was drawn from behind and below. Because the portraits are such vivid, compelling likenesses the artist’s remarkable spatial/plastic illusionistic facility can be underestimated. As shown below at Fig. 15, Holbein, like a sculptor, clearly appreciated that a head is an object, and that depicted faces constitute a record of the visible front of an object that is deeper than it is wide – and, therefore, that a face drawn full-on must find the graphic means to evoke the depths of a head (as was brilliantly achieved by Holbein in Henry Howard, above, right) by plastically nuanced tonal variations. So-saying is not to fail to recognise that for very good reasons and from infancy, human beings attend more to faces than to profiles – and nor is it to disregard Holbein’s own distinctive human engagement and psychological penetration*. It is simply to recognise the paradoxical ease with which viewers can safely make plastic/sculptural extrapolations from Holbein’s predominantly linear drawn likenesses. In this regard, Paul Ganz, spoke eloquently in his 1950 The Paintings of Hans Holbein: “…line was the means by which he rendered form, indicated movement and suggested expression. It remained the sure foundation even of his painting, and gave to his figure compositions, his portraits and even his decorative works an astonishing clarity and organically coherent solidity.” (*On Holbein’s emotional truthfulness, see Susan Foister’s fine “Holbein the Portraitist” in her 2004 Holbein & England.)

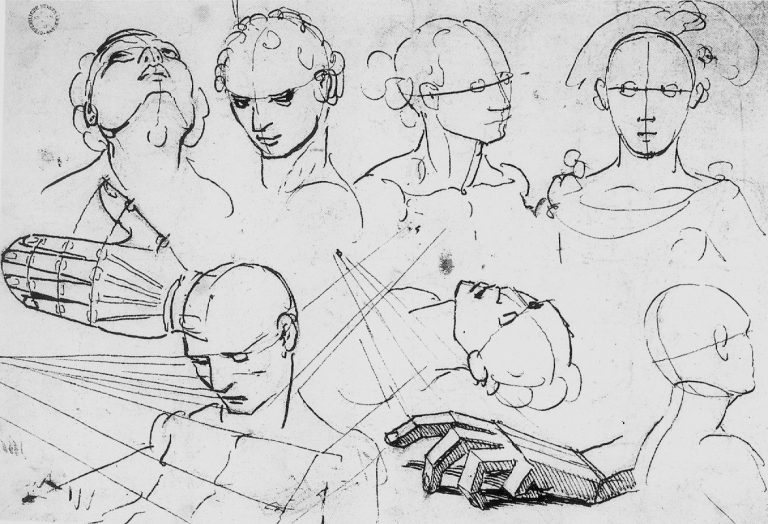

Above, Fig. 15: An ink-over-chalk study sheet in which Holbein simultaneously examines the plastic structures of heads; the expressive force of directional gazes; and – with a curving line in each head (except for the top right head where, being seen from the front, the profile registers as a straight line) – unfailingly locates and orientates the faces’ profiles. (Ӧffenliche Kunstsammlung, Basel, Kuperfestichkabinett.)

In all graphic, painted, and sculptural media, the profile of a head is the single most potent contour because the plastic entirety of a head is bounded by and articulated within it. Expressively speaking, the profile also fixes the distinctive “set” of a sitter’s head, as seen below and above at Fig. 14 with Holbein’s “Simon George” drawing.

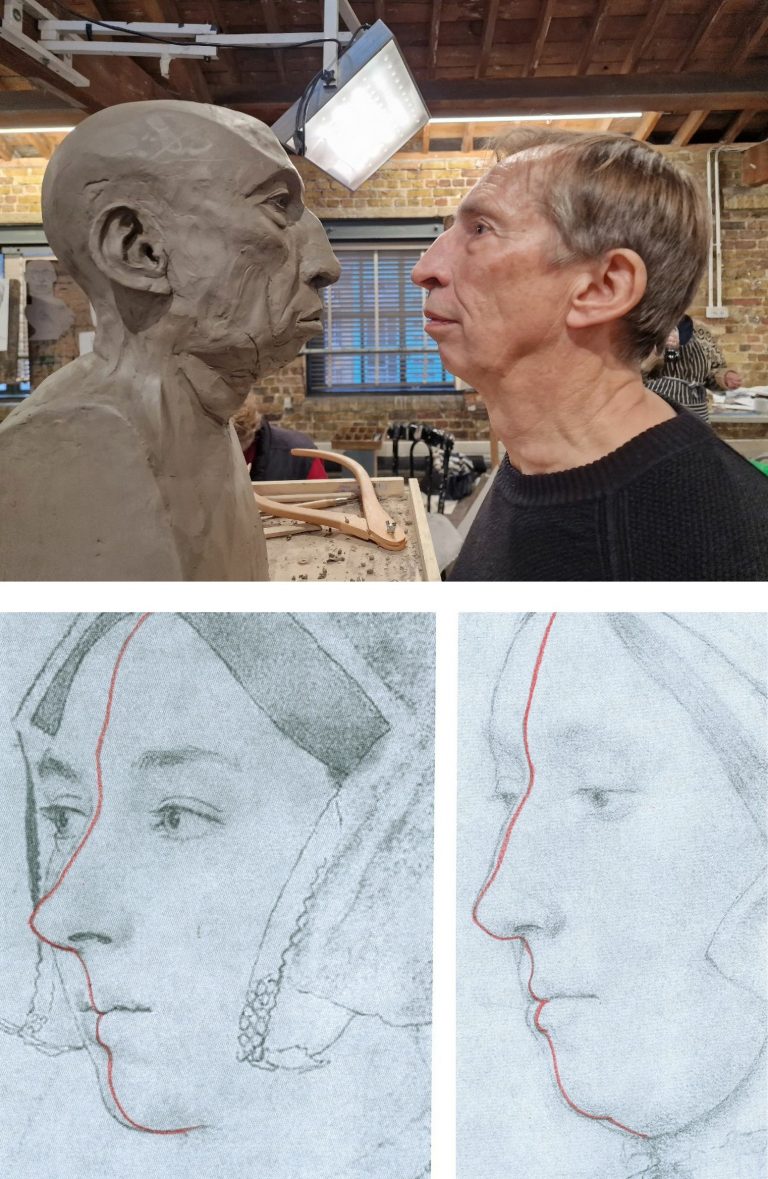

Above, Fig. 16: Top, a modelled head-in-progress and its sitter, at the Royal Drawing School; bottom, extrapolated lines indicating the location of the sitters’ profiles in the two contested “Anne Boleyn” portraits. While flesh might sag with age, the bony part of the nose does not continue to grow.

Above, Fig. 17: Top row, the Hever Castle Anne Boleyn painting (mirrored) and a detail of the British Museum Anne Boleyn drawing, far right, the actor Natalie Dormer in role as Anne Boleyn in the 2007-10 TV series The Tudors; centre row, views of an Anne Boleyn waxwork at Hever Castle modelled by Emma Pooley (– “I settled on Holbein’s sketch of Anne as it has always been my favourite, and is by far the most realistic reproduction, in terms of skill, of her image from around the time”); bottom row – the Pooley waxwork at Hever Castle; a painting of Anne Boleyn at Hever Castle; a waxwork of Anne Boleyn at Warwick castle.

All the above paintings and waxwork reconstructions of Anne Boleyn share a common and simple three-part dynamic in their profiles with that present in the British Museum drawing. That is, in each, from the top downwards: the forehead advances somewhat; the nose advances more rapidly; but then, from the base of the nose the profile moves into reverse and retreats appreciably down through the mouth and to the chin. The Royal Collection drawing’s profile has a different, flatter dynamic and for clear reasons of anatomy could not have been made from the same sitter.

WHO WAS ANNE BOLEYN?

Above, Fig. 18: Left, the British Museum Holbein Anne Boleyn drawing (detail); right, the Royal Collection Anne Boleyn drawing (detail). Note the line that descends from the turned-up wing of the gable hood on the right of the BM drawing.

The sitter on the left is younger, slimmer, brighter-eyed (albeit with grey/blue eyes, not brown) and is shown to have dark hair and dark eyebrows. She has a sharper, less highly bridged and more upturned nose with markedly larger nostrils. Her eyes are focussed, attentive, seemingly purposive, certainly not downcast, or self-absorbed and reflective – or with a pronounced fold of flesh over the upper eyelids. She has a single, not a double chin. In this context, Anne’s recorded character and appearance might be considered. Eric Ives, author of the acclaimed 2004 The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn (which succeeded his 1986-1994 Anne Boleyn), wrote:

“Captivating to men, Anne was also sharp, assertive, subtle, calculating, vindictive, a power dresser and a power player, perhaps a figure to be more admired than liked…All reports agree that she was dark. As well as Sanuto’s ‘swarthy’, Thomas Wyatt gave her the poetic name, ‘Brunet’.”

Ives cited a host of contemporary descriptions:

“…beautiful with an elegant figure”; “very beautiful”; “very eloquent and gracious, and reasonably good looking”; “young and good looking”; “not one of the handsomest women in the world, she is of middling stature, swarthy complexion, long neck, wide mouth, a bosom not much raised, and eyes which are black and beautiful…” Ives summarised: “Looks only tolerable, but a splendid head of dark hair and fine eyes”. One observer expanded on Anne’s use of her eyes: “…eyes always most attractive Which she knew well how to use with effect, sometimes leaving them at rest, and at others sending a message to carry the secret witness of the heart. And truth to tell, such was their power That many surrendered to their obedience.” Ives remarked that Anne “…radiated sex”. Emma Pooley’s choice of source image was sound: no female sitter’s eyes in Holbein’s drawings better evoke such reported properties and powers than those found in the British Museum drawing of Anne Boleyn – and, on this emotionally charged correspondence, Rowlands had seemed almost to concur in 1977: “The eyes, of a rare beauty, the eyebrows and eyelashes are all marvellously drawn”.