Leonardo, Salvator Mundi, and an “unusual lapse”

On 20 October, Bendor Grosvenor posted an attack, “’Mystery’ over Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’”, on a Guardian article written by Dalya Alberge, “‘Puzzling anomaly’ at heart of £75m artwork”.

The Guardian piece had reported my views on the viability of the recent attribution to Leonardo of a damaged and re-restored Salvator Mundi painting (Fig. 3 below) and it had noted the addressing of those views by Walter Isaacson in his new book Leonardo da Vinci ~ The Biography. (My concerns had been published in two – unchallenged – letters to the Times: “Leonardo viewed in a curious light”, 12 November 2011, and “Leonardo enigma”, 12 October 2017. See Fig. 1 below).

Grosvenor carries the following passage from Alberge’s article:

“But in a forthcoming study, Leonardo da Vinci: The Biography, Walter Isaacson questions why an artistic genius, scientist, inventor, and engineer showed an ‘unusual lapse or unwillingness’ to link art and science in depicting the orb.

“He writes: ‘In one respect, it is rendered with beautiful scientific precision…But Leonardo failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb.’

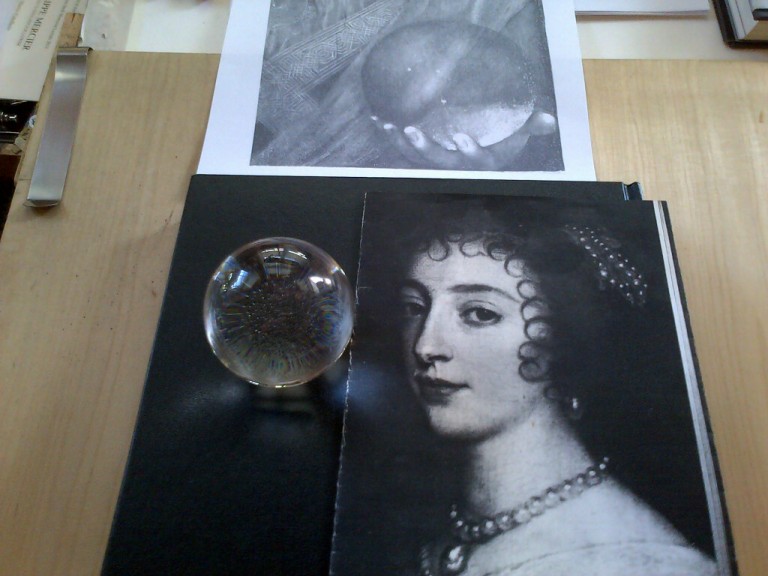

“‘Solid glass or crystal, whether shaped like an orb or a lens, produces magnified, inverted, and reversed images. [See Fig. 4 below] Instead Leonardo painted the orb as if it were a hollow glass bubble that does not refract or distort the light passing through it.’

“He argues that if Leonardo had accurately depicted the distortions, the palm touching the orb would have remained the way he painted it, but hovering inside the orb would be a reduced inverted mirror image of Christ’s robes and arm.”

Grosvenor then contends that:

“All of which might lead you to believe that Isaacson did not think the painting was by Leonardo, or at least was raising serious questions.”

In so claiming, Grosvenor seemed to have overlooked this further passage in which Alberge reports a conversation she had with the author:

“Isaacson said Leonardo filled his notebooks with diagrams of light bouncing around. So did he [Leonardo] choose ‘not to paint it that way, because he thought it would be a distraction…or because he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality’.”

That passage correctly indicates that Isaacson was genuinely perplexed as to why Leonardo had on that occasion not painted in a way that might have been expected, given his great interest and passion for optical laws. It did not say that Isaacson himself had concluded that Leonardo had not painted the picture. However, Grosvenor adds:

“But on his Facebook page, Isaacson writes: ‘Just to be very clear, this article leaves a bit of a false impression. In my new book, I state clearly and unequivocally that the painting of Salvator Mundi is by Leonardo. And I explore the reasons that he did not show the crystal orb distorting the robes of Christ. I say it was a conscious decision on Leonardo’s part. I do not say in my book, nor did I say in the interview, nor do I believe, that anyone but Leonardo painted this painting. I believe he made a decision to paint the crystal orb in a way that is miraculous and not distracting. All of the experts I know agree, from Martin Kemp to Luke Syson.’”

It is not the case that all Leonardo experts endorse the Leonardo attribution. Nor is it apparent why Isaacson might have felt impelled to make such a “lawyered-sounding” statement over what he feared might at most be “a bit of a false impression” but Grosvenor seemed to relish the fact of it:

“So that’s that; nothing to see here. And please don’t be at all persuaded by the attempt, elsewhere in the article, to use Wenceslaus Hollar’s engraving of the Salvator Mundi to cast doubt on the painting. It has been suggested that because the engraving shows some small, in some cases actually imperceptible, differences to the painting at Christie’s, then the painting at Christie’s might not be the painting which was engraved. This is fantasy art history. First, such differences reflect more on Hollar’s ability as an engraver than the painting. Second, compare other examples of Hollar’s engravings with the paintings to which they relate and you will see that he regularly altered aspects of the composition. Third, we cannot know how long Hollar had to study the original. Finally, Hollar saw the painting more than one hundred years after it was painted. Who knows what might have happened to it in that period?”

Grosvenor’s strained disparagement of Hollar’s engraved testimony (“small, in some cases imperceptible”) alludes to quoted remarks of mine in the Guardian article and to my 12 October Times letter (“Leonardo enigma”). Coming as this does from a man who has likened himself to a Mozart among Salieris in the art dealing, sleeper-hunting community, it may require a response consisting of the very clearest visual evidence. Such will follow in a later post. Here, it might be noted that although my position is certainly not shared by Isaacson, it was not disparaged by him in his book. To the contrary, during his interview for the Guardian article he generously acknowledged having been prompted by my views to raise the very question of why Leonardo might have painted the orb in such a strikingly unexpected fashion. In addition, he cited our 12 June 2012 article “Could the Louvre’s ‘Virgin and St Anne Provide the Proof that the (London) National Gallery’s ‘Virgin of the Rocks’ Is Not by Leonardo da Vinci?”. (See Fig. 2 below.)

CODA – Walter Isaacson on the Salvator Mundi in his Leonardo da Vinci ~ The Biography:

“There is, however, a puzzling anomaly in the painting [see Fig. 3 above], one that seems to be an unusual lapse or unwillingness by Leonardo to link art and science. It involves the clear crystal orb that Jesus is holding. In one respect, it is rendered with beautiful scientific precision. There are three jagged bubbles in it that have the irregular shape of the tiny gaps in crystal called inclusions.

“Around that time, Leonardo had evaluated rock crystals as a favor for Isabella d’Este, who was planning to purchase some, and he captured accurately the twinkle of inclusions. In addition, he included a deft and scientifically accurate touch, showing he had tried to get the image correct: the part of Jesus’ palm pressing into the bottom of the orb is flattened and lighter, as it would indeed appear in reality. But Leonardo failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb. Solid glass or crystal, whether shaped like an orb or a lens, produces magnified, inverted, and reversed images. Instead, Leonardo painted the orb as if it were a hollow glass bubble that does not refract or distort the light passing through it. At first glance it seems as if the heel of Christ’s palm displays a hint of refraction, but a closer look shows the slight double image occurs even in the part of the hand not behind the orb; it is merely a pentimento that occurred when Leonardo decided to shift slightly the hand’s position. Christ’s body and the folds of his robe are not inverted or distorted when seen through the orb. At issue is a complex optical phenomenon. Try it with a solid glass ball [see our demonstration at Fig. 4 below]. A hand touching the orb will not appear to be distorted. But things viewed through the orb that are an inch or so away, such as Christ’s robes, will be seen as inverted and reversed. The distortion varies depending on the distance of the objects from the orb. If Leonardo had accurately depicted the distortions, the palm touching the orb would have remained the way he painted it, but hovering inside the orb would be a reduced and inverted mirror image of Christ’s robes and arm.

“Why did Leonardo not do this? It is possible that he had not noticed or surmised how light is refracted in a solid sphere. But I find that hard to believe. He was, at the time, deep into his optics studies, and how light reflects and refracts was an obsession. Scores of notebook pages are filled with diagrams of light bouncing around at different angles. I suspect that he knew full well how an object seen through a crystal orb would appear distorted, but he chose not to paint it that way, either because he thought it would be a distraction (it would indeed have looked very weird), or because he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality to Christ and his orb.”

Michael Daley, 23 October 2017

Leave a Reply