Hollow Gods and Dangerous Beauty

With museum and gallery visits becoming ever-more crowded noisy expensive and denuded of works loaned, in needless restorations, or stored as directors play developers as well as impresarios, the appeal of small venues grows. Bury Street in St James’s is buzzing with two (free) exhibitions, one light on drawings, one rich.

A principal delight of the non-museum/gallery sector is un-trailed and unanticipated cross-fertilisation. Until 13 December, Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert is showing Eduardo Paolozzi (Hollow Gods – Sculpture and Collage from 1946-1960) and, hard after its “From Michelangelo to Matisse: Five Centuries of Drawing”, Colnaghi is running (until 24 January) a big and various show, “Dangerous Beauty” – dangerous because themed on “the seductive beauty of the female form” at a time when “women around the world are claiming back the right to be represented without male filters”.

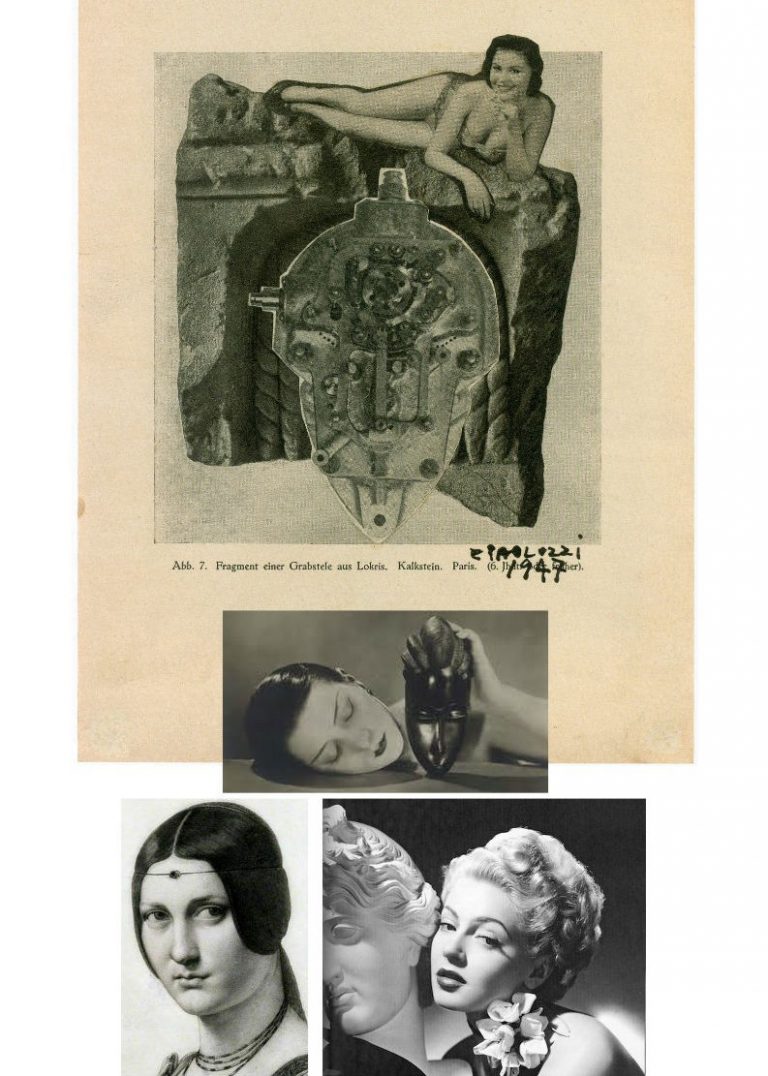

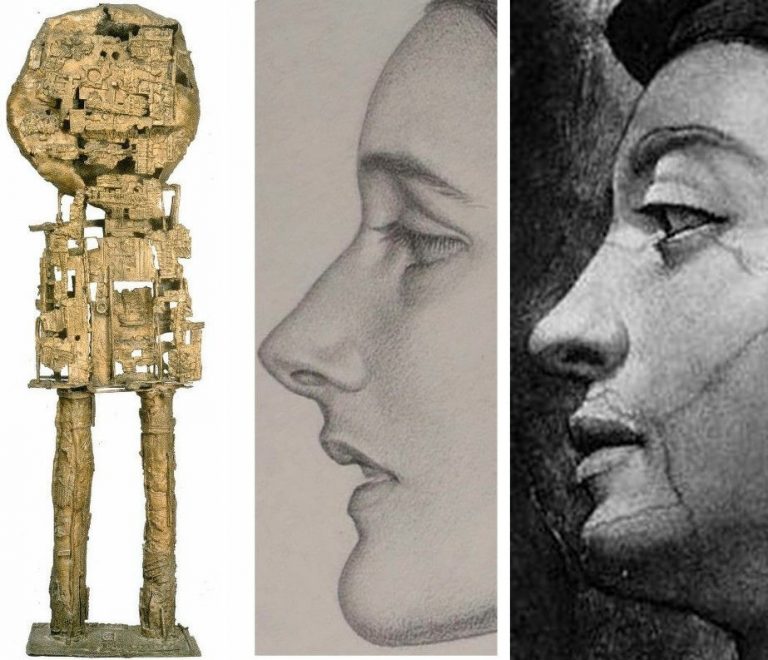

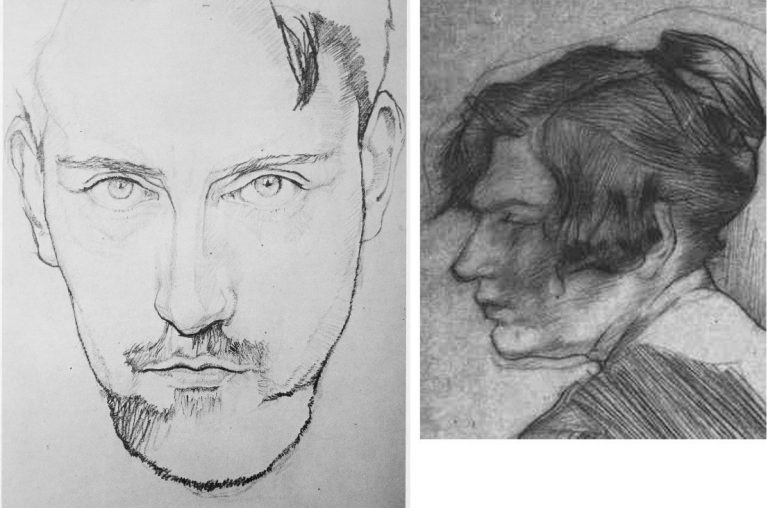

Above, Fig. 1: Left, Paolozzi’s 1947 Fragment einer Grabstele aus Lokris, detail; right, Colnaghi’s Karl Parsons 1933 pencil drawn Patricia.

Where the Paolozzi show is, as its title indicates, light on drawings, the Beauty Show is especially rich and the Parsons drawing itself constitutes a dangerous revelation in one rumbling art political context discussed below.

It was something of a shock to realise just how historic – and overdue – this (nicely catalogued) Paolozzi survey is. For nearly two decades after the Second World War the sculptor was quintessentially modish and acclaimed as an intellectually and formally invigorating force. Rich in friendships with rising modernist critics and architects, Paolozzi was unusually cosmopolitan being of Italian parents in Scotland, spending time in Paris imbibing Picasso, Klee, Giacometti, Dubuffet and admiring Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning, Leon Golub, Germaine Richier, Richard Stankeiwicz and Alberto Burri. In due course he, like many British sculptors, became an art fashion casualty of the all-conquering hard-line “concrete” formalist vocabularies forged by the St Martins School which grouping was held for a while to comprise Britain’s Greatest Sculptors since the Middle Ages. The self-impoverishment of that school’s stance – effectively, that material bears its own message – left space for Paolozzi, like Henry Moore before him, to become the leading producer of Grand Civic Sculpture and, even, to uphold the figurative banner. The Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert show demonstrates how much was lost when Paolozzi abandoned his fugitive evocatively battered but upstanding early figurative explorations for more decorative printed graphics (- sometimes veering on the psychedelic), design and large-scale architectural productions.

Strictly-speaking, Paolozzi was neither a traditional draughtsman nor a traditional sculptor. He did not carve, model or even fabricate. Rather, he scavenged, appropriated and re-assembled. From childhood he had been an avid, omnivorous reader and collector of illustrated books, comics, advertisements, sports, health and technical manuals. Amidst the world’s plethora of reproduced images and mechanical objects he showed a distinct nose and sympathy for the paradigmatic force of classical sculpture’s now-fragmentary figures, busts, bases, pedestals and so forth. It is possible that he was alerted to classical art – as well as to badges, uniforms and aeroplanes – when sent by his father to summer in fascist youth camps in Italy.

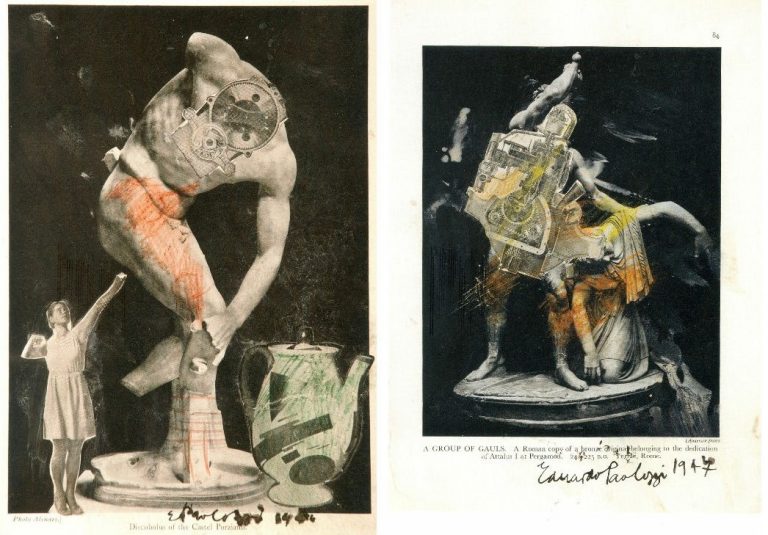

Above, Fig. 2: Left, A Group of Gauls, collage, pencil and wash, 1947; right, the Discobolus of the Castel Porziano, collage and ink wash, 1946.

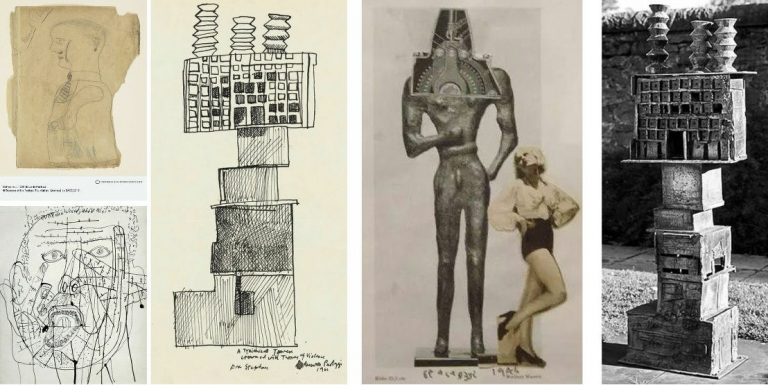

Above, Fig. 3: Left, top, Untitled, collage, 1946; above left, Small Monument, 1956, unique bronze, H 13 inches (33 cm); second left, Figure with Raised Arm, 1955, bronze, H 18 inches (46.5 cm); third left, Robot, bronze, H 19 inches (48.5 cm); right, Figure, 1957, bronze, H 48 inches (123 cm).

CUTTING AND ASSEMBLING

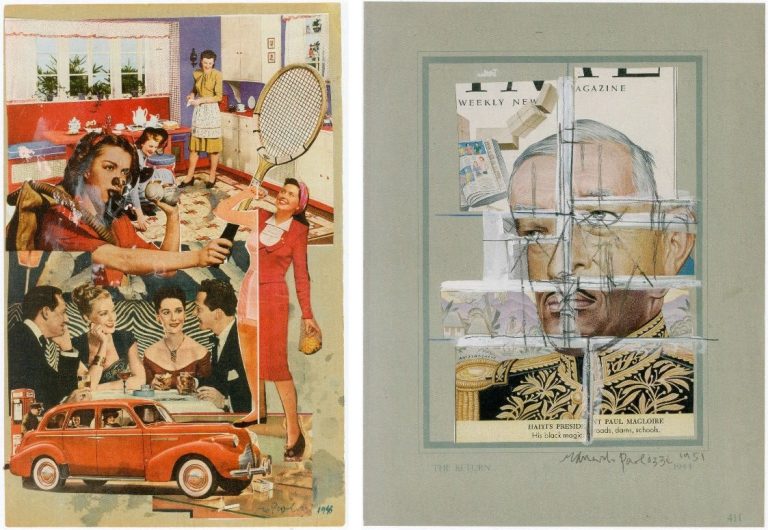

Above, Fig. 4: Left, Untitled, 1948, collage, 37 x 24 cm; right, The Return, 1954, collage, pencil and gouache, 13 x 10 inches.

Paolozzi’s witty mini-essay on monuments at Fig. 3 caught the eye of Henry Moore, who bought it. The collaged Untitled image above left might easily be taken today as a trenchant visual synopsis for the “Mad Men” TV series but in the UK’s impoverished food-rationed and punitively-taxed post-war years American affluence had yet to become a source of self-loathing shame and Paolozzi’s collaged image might better be seen as an innocent celebratory act of awe and wonderment. His affection for the United States famously (and influentially) extended to its popular culture and especially to its movies which he saw not as sources of harvestable imagery but as “direct experience” to be lived. Boris Karloff, The Mummy’s Hand and Frankenstein were, however, acknowledged to have “supplied a thread in his beat-up human image.”

As late as 1957, Paolozzi saw the United States as offering more to an artist than the Mediterranean. However, with The Return, above right (and other such graphic collages) a darker colder side emerges. Slicing up images – particularly images of faces – and reconfiguring them to misaligned satirical intent is not cuddly. Much later, in the 1980s, Paolozzi would carry the cutting and reconfiguring into grander more conventionally realised sculptures whose forms were clearly delineated by an otherwise continuous surface skin. Those late dismembering exercises seemed free of sadistic intent and to be deployed more to impart a formal dynamism than any expressive or symbolic purpose. Nonetheless, slicing up and recomposing images or effigies of human faces and heads is inherently unsettling and question-raising. Does the enlarged, flattish circular head of Paolozzi’s St Sebastian at Fig. 7 below allude to a sun/halo or an archer’s target board?

Above, Fig. 5: Left, top, a Paolozzi self-portrait made as an eleven-year old schoolchild; left, above, Paolozzi’s 1953 ink drawing Self-portrait; second left, a 1961 drawing for the sculpture Tyrannical Tower Crowned with Thorns of Violence – and as realised at the National Galleries of Scotland, above, far right; third left a photo-collage of 1946.

AUTHENTICITY IN AN ERA OF UNIVERSALLY HARVESTABLE AND REPLICABLE IMAGES

Above, Fig. 6: Above, top, Paolozzi’s 1947 photo-collage Fragment einer Grabstele aus Lokris shows the artist at full throttle. The limited means – just three “lifted” images – is classically restrained: a cheesecake pin-up of the kind that had recently graced millions of soldiers war-time lockers and kit bags; an eloquent fragment of antique carving speaking of lost civilisations; and, as representative of the future and increasing well-being, an item of machinery that perfectly mimics Western modernist artists self-consciously cultish appreciation of African masks. Today, we make what we may be permitted of this nicely triangulated homage but sparks still fly and engage with other art – as with the above famous 1926 Paris Vogue Man Ray portrait of Kiki de Montparnasse.

The Man Ray photograph had found echoes before Paolozzi, as above in the 1942 promotional/glamour photograph of Lana Turner by Eric Carpenter (which is preceded by Ingres’ pencil copy of Leonardo’s painted portrait known as La belle ferronnière ). In the 2000 Hollywood Portraits book by Roger Hicks and Christopher Nisperos, the authors raise questions of authenticity in photography-as-art. While Carpenter’s “chiaroscuro is striking”, they seem to complain, “there is much retouching in this picture. Most of what we see between the actress and the statue looks like airbrushing, particularly the shadow next to her cheek, but the keyline on the chin is genuine and beautifully executed – a reflection from the background…the profile is masterful, and the canting of the camera – a popular device at the time – is all but essential: it places the main subject’s face at a more attractive angle and greatly reduces the apparent mass of the statue, which otherwise might dominate the composition. The principal tricks in re-creating this picture are, first, the very careful control of the chiaroscuro; second, the angled camera; and third, diligent and extensive retouching…” (For Hicks and Nispero’s further views on the role and means of retouching, see “Coming to Life: Frankenweenie – A Black and White Michelangelo for Our Times” .)

With the many technical and professional advances in photography and cinema – not least digitalisation – and the widely indulged licence to tamper -the boundaries between art (where images are made) and photography (where images are taken) are clearly weakening. Practical problems follow: can steps be taken to prevent or even identify the illicit manufacture of perfectly deceiving facsimiles of bona fide works? As Dalya Alberge discloses, Man Ray’s iconic Kiki de Montparnasse image exists in more versions than should be the case – “Fake Man Ray prints are hanging on museum and collectors’ walls, leading specialist warns”.

CLASSICAL TENACITY

Above, Fig. 7: In this fast moving and problematic technical world, the simultaneous appearance within a hundred yards of Paolozzi’s 1957 bronze St Sebastian IV and Karl Parsons’ 1933 pencil drawn Patricia came as a jolt. We all well know of Paolozzi’s art but how many knew of Parsons’ society portrait drawings? The two works above left and centre might seem worlds and eons apart but where Paolozzi was thirty-three years old when he made his St Sebastian at a time when traditional art school practices were crumbling, he was nine years old when the forty-nine year old Parsons drew Patricia (in what would be the last year of his life). Parsons had attended some classes at the Central School of Arts & Crafts in London but essentially learned his craft in the doing – that is, in the time-honoured role of apprentice to a successful working master, in his case, to the leading Arts and Crafts Movement stained glass maker, Christopher Whall. Parsons went on to carry out major commissions for the windows of Canterbury, Gloucester, Cape Town and Johannesburg cathedrals. Beyond that rigorous training and high-level artistic practice, Parsons all the while had at his back centuries of tradition – it is not fanciful to see a direct line from Michelangelo’s monumental painted profile from the Sistine Chapel ceiling’s Erythraean Sibyl (here mirrored, above right) to Parson’s modest (15 by nearly 12 inches) monogrammed profile portrait in pencil on paper.

Above, Fig. 8: Colnaghi’s larger, mixed show happens to contain a mini-exhibition of modern (traditional) female profile portraits drawn on paper. First, above left, is Augustus John’s 1907 portrayal in black chalk of his mistress/muse/mother figure, Dorelia McNeill, who at sixteen had edited a magazine called The Idler. Second left, is Gerard Leslie Brockhurst’s pencil on paper portrayal, Anais. The Parsons drawing’s sitter is considered most likely to be Patricia Frances, Lady Strauss. A vintage National Portrait Gallery photograph of her (by Bert Sachsel), from the late 1930s or early 1940s, as above right, displays striking facial similarities, as well as the same hairstyle. Patricia, an author and politician who stood unsuccessfully for the Labour Party in Kensington South at the 1945 General Election, married George Strauss, MP, in 1932, and became Lady Strauss in 1979. A significant patron of both the performing and the visual arts, she led a campaign to persuade the government to use half a percent of the cost of all new buildings for works of art and pioneered the first international sculpture exhibition in Battersea Park. (In the 1963 Battersea sculpture show Paolozzi exhibited along with Henry Moore, Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick, Geoffrey Clarke, Bernard Meadows, William Turnbull and others.)

Above, Fig. 9: Top, two stained glass heads by Karl Parsons; above, left, Paolozzi’s 1953 self-portrait, and, above, right, one of his 1980s ink on tracing paper studies of the architect Richard, now Lord, Rogers. More than half a century and the Second World War stands between the above two pairs of images. The chasm of artistry and draughtsmanship between Parsons and Paolozzi in these works might seem painful to contemplate. Looking at these images today, who eclipsed whom artistically? The principal charge against Arts and Crafts depictions was of a perceived saccharine sweetness and sentimentality. Was the suppression of such traits best or necessarily made by evocations of psychic derangement and a drawn proposal for a combined scalping and splitting of an identifiable person’s effigy bust? Are we still forbidden to admire the remarkable artistry and sheer force of expression in Parsons public works?

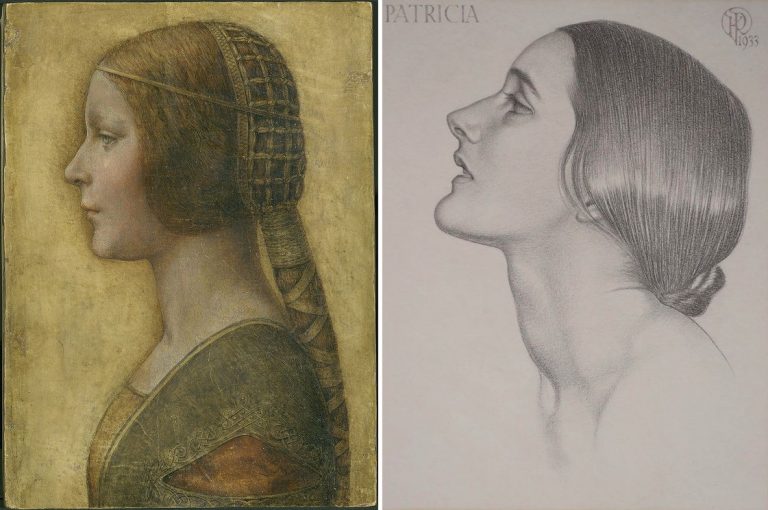

Above, Fig. 10: Left, “La Bella Principessa”, a mixed media drawing attributed to Leonardo; right, Karl Parson’s Patricia.

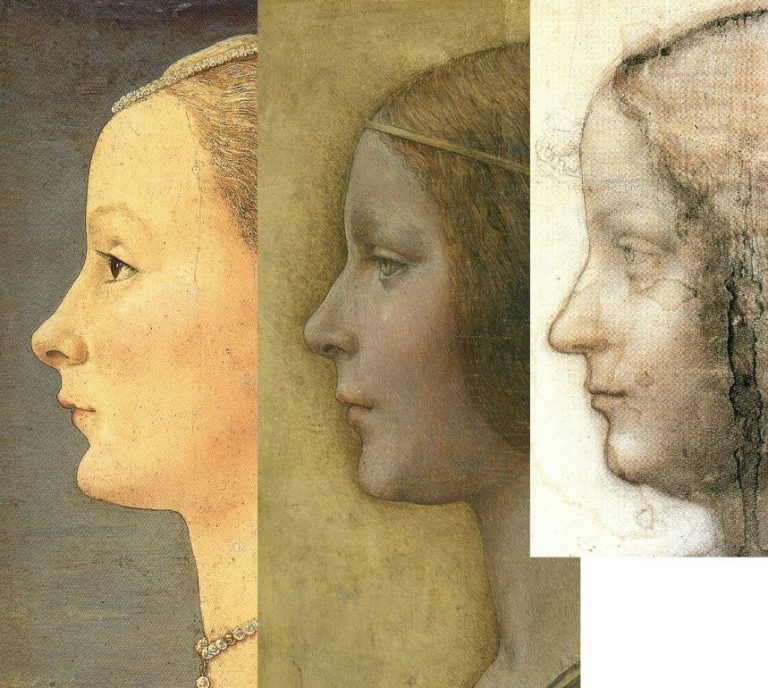

In the pairing above, we see either Parsons pitted against a newly discovered (that is, a claimed) Leonardo drawing of a princess, or – as we believe – two possibly near-contemporaneous twentieth century works. The emergence of Parson’s pencil-drawn Patricia (above right) coincides with a near decade-long campaign of advocacy on behalf of the (unsold) supposed-Leonardo portrait of a short-lived Milanese princess, Bianca Sforza (above left), that Professor Martin Kemp dubbed “La Bella Principessa”. The drawing was so attributed in knowledge that this profile portrait type has been assailed by modern forgeries: “Complications for the historian lie both in the fact that the subjects of most female portraits are no longer identifiable and that, because of their exceptional decorative and historical appeal, such portraits were highly sought after by later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century collectors, encouraging a market for copies, fakes and over-ambitious attributions” – Alison Wright, The Pollaiuolo Brothers, Yale University Press, 2005.

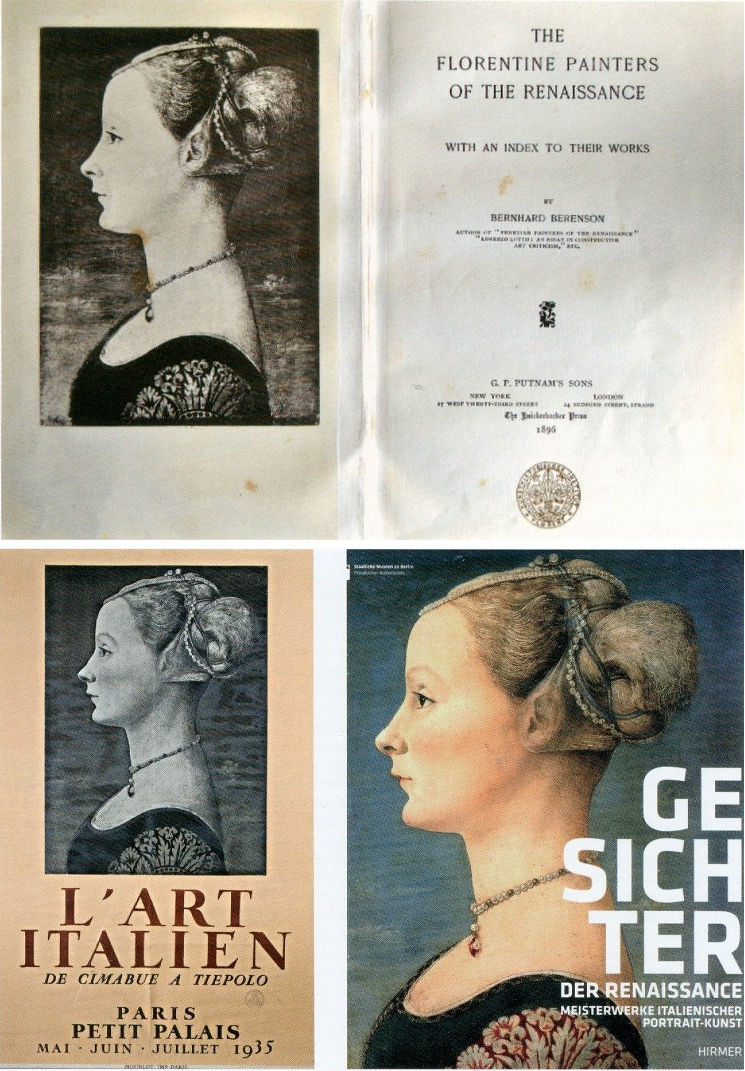

Above, Fig. 11: Left, the (mirrored) obverse of a bronze medal of c. 1486 attributed to Niccolo Fiorentino; right, four 15th century paintings judged most likely by the Polliauolo brothers, Antonio (figures 1 and 4) and Piero (figures 2 and 3). We mentioned a link between Parsons and Michelangelo. In truth, Parsons’ Patricia may intentionally have referenced the earlier (15th century) archaising profile portrait tradition with paintings made in emulation of classical relief portraits found on antique coins.

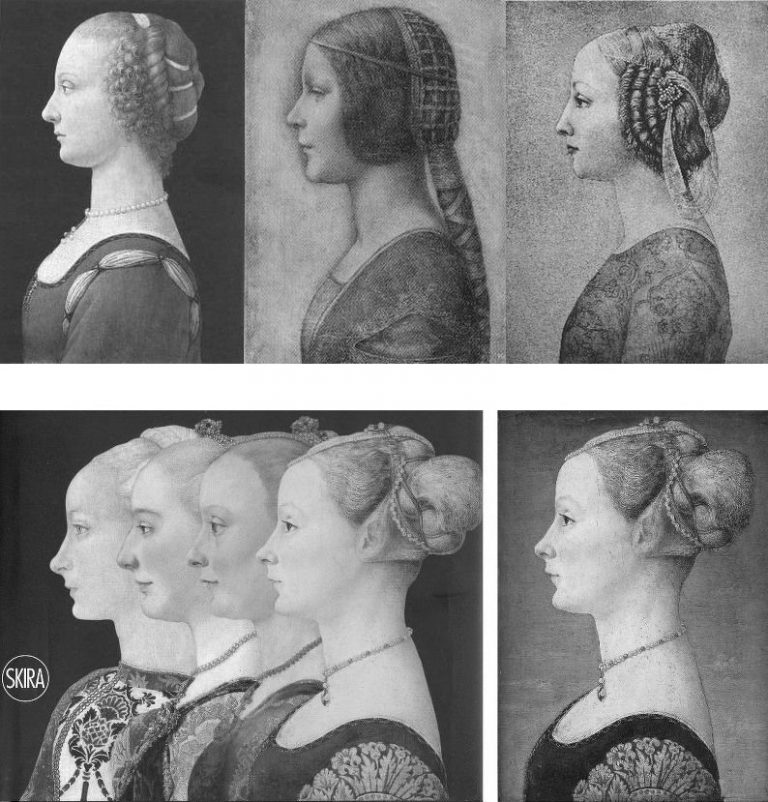

Since its first appearance as a prospective Leonardo drawing, we have suspected “La Bella Principessa” to be a work of the 20th century. The fakes-generating popularity of the profile-lady type of which Alison Wright spoke is attested in Fig. 12 above, where we see that in the early years of the 20th century, Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s Profile of a Woman seems to have enjoyed position as an exemplar of the 15th century profile portrait type wherein, as Ingres noted, “Never is a woman’s neck too long”.

TRUE TO TYPE?

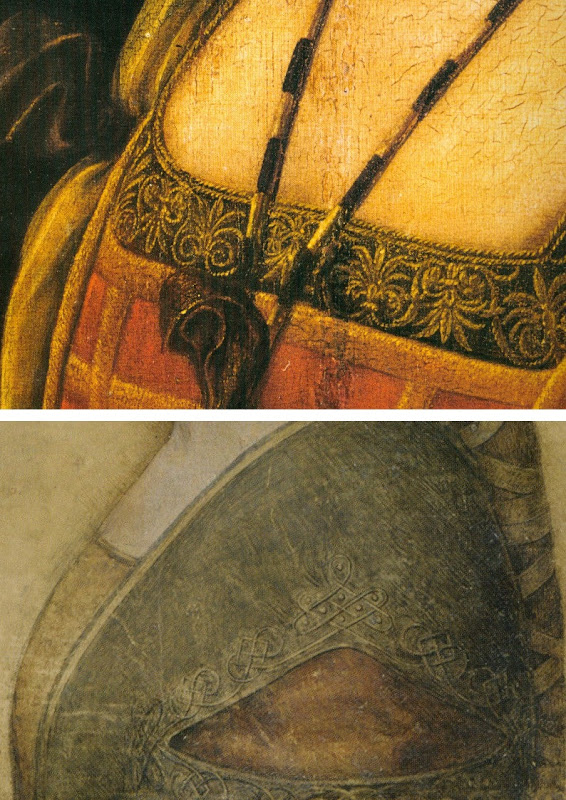

Above, Fig. 13: We take all three works in the top tier to be modern productions and all four works in the bottom row to be not only bona fide 15th century paintings but, in the case of Antonio Polliauolo’s Profile of a Woman in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan (as in the fourth and fifth images) the most popular version of a most popular type. For those wishing to make modern versions, Polliauolo’s Milan profile seems to have been taken almost as a template because of its great attractiveness and because its rather truncated composition greatly minimises the work needed properly to depict a richly and elaborately costumed torso (– as seen below at Fig. 14). The authors of all three versions in the top tier have taken short cuts and depicted implausible costumes.

The picture on the left was bought in 1936. The picture in the centre first appeared in 1998 – 502 years after its presently-claimed execution. The figure on the right was last seen in a book published in the 1940s. It then disappeared and its whereabouts are now unknown.

The first picture was bought by the Detroit Institute of Arts as by Andrea del Verrocchio or Leonardo da Vinci. It was recently exposed as an outright fake: it contains modern pigments and it was painted on top of a photograph – see “Art’s Toxic Assets and a Crisis of Connoisseurship ~ Part II: Paper (sometimes photographic) Fakes and the Demise of the Educated Eye”

The “La Bella Principessa” drawing emerged without provenance and anonymously as the property of a lady in 1998 at Christie’s, New York, where it was sold as a 19th century German work for $22, 850 to a dealer who sold it on in 2007 for $19,000 to its present owner. Its advocates have said of tests on the vellum: “This dating confirms that the portrait could well have been made in Leonardo’s lifetime, supporting Martin Kemp’s proposed date in the mid-1490s and virtually eliminating the possibility that it is a 19th century pastiche.” “Confirming” a “could well have been” is double-speak which itself rests on only a loose and wide overall estimation of probabilities. It was not acknowledged that within the overall figure, the probabilities had been greatly more precisely quantified. While the report states that there was a 68.2% probability that the sheet was made between 1470 and 1650, within that period there was only a 27.2% probability that the drawing was made between 1470 and 1530 – whereas there was an appreciably greater probability (41.0%) that the sheet was made some time between 1550 and 1650. Had the vellum been made at any point after 1496, when the work is claimed to have been executed by Leonardo, the attribution would sink. Moreover, even if the sheet had existed before 1496 that would not establish the date of the drawing’s execution: in The Art Forger’s Handbook Eric Hebborn explained that a prime source of old materials is obtained from blank end papers in books.

Above, Fig. 14: Left, Pollaiuolo’s Profile of a Woman; second left, “La Bella Principessa”; third left, Portrait of Bianca Maria Sforza, c. 1493, by Ambrogio de Predis, The National Gallery of Art, Washington; right, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni, (1488) Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

It is striking in this comparison with three secure paintings how dull and underpowered the work is and how (relatively) impoverished is the appearance now-claimed subject, Bianca Sforza, the short-lived illegitimate daughter of Il Moro, the Duke of Milan. The subject third left is said to be Bianca Maria Sforza, Bianca Sforza’s cousin. In the catalogue to the (London) National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition Arturo Galansino said of Bianca Maria’s portrait that the artist’s focus on the sumptuous clothes testified to the luxury of “the most opulent court in Italy”. How credible can it be that the strikingly impoverished, jewellery-free image of Bianca had been commissioned in celebration of the wedding of the Duke’s own daughter to a powerful ally? Martin Kemp has hedged against this implausibility with a suggestion that the portrait might, instead, have been a memorial record made after her death: “It may be that the restraint of her costume and the lack of jewellery indicate that the portrait was destined for a memorial rather than a matrimonial volume”.

Above, Fig. 15: Top, a detail of Leonardo’s portrait La belle ferronnière, the Louvre; above, a detail of “La Bella Principessa”.

DRAWN FROM LIFE OR MADE AFTER DEATH?

Above, Fig. 16: Left, Pollaiuolo’s Profile of a Woman; centre, “La Bella Principessa”; right, Leonardo’s Portrait of Isabella d’Este, of c. 1500 in the Louvre Museum (- here mirrored).

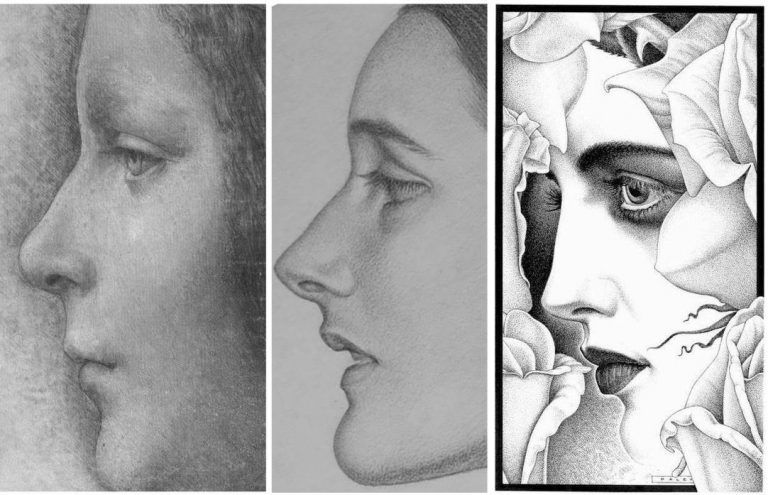

Forgers and pasticheurs alike are obliged to make their works resemble secure works of a given artist and period. On the hypothesis that “Bianca/La Bella Principessa” was likeliest a work of the late 19th, early 20th century, how might the present image have been generated? Making one that resembled Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s, Profile of a Woman in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan, as above left, would be sure to strike a reassuring stylistic and period chord. If the aim was to make a work of that archaising type that looked as if made by Leonardo, then a forger could also make use of one or other of the few female strict profile drawings that Leonardo made. If we place the face of “La Bella Principessa” between those of Pollaiuolo and Leonardo’s drawing of Isabella d’Este, as above, then a most striking hybrid emerges: feature by feature, “La Bella Principessa” hovers between the Pollaiuolo painting and the Leonardo drawing – as with, for example, a more upturned nose and pronounced “over-bite” projection at the upper lip than is seen in the Leonardo. A single feature only – the eye – does not conform to this two-way accommodation: “La Bella Principessa’s” eye is unlike either of those present in the other two works.

THE EYE IN THE OINTMENT

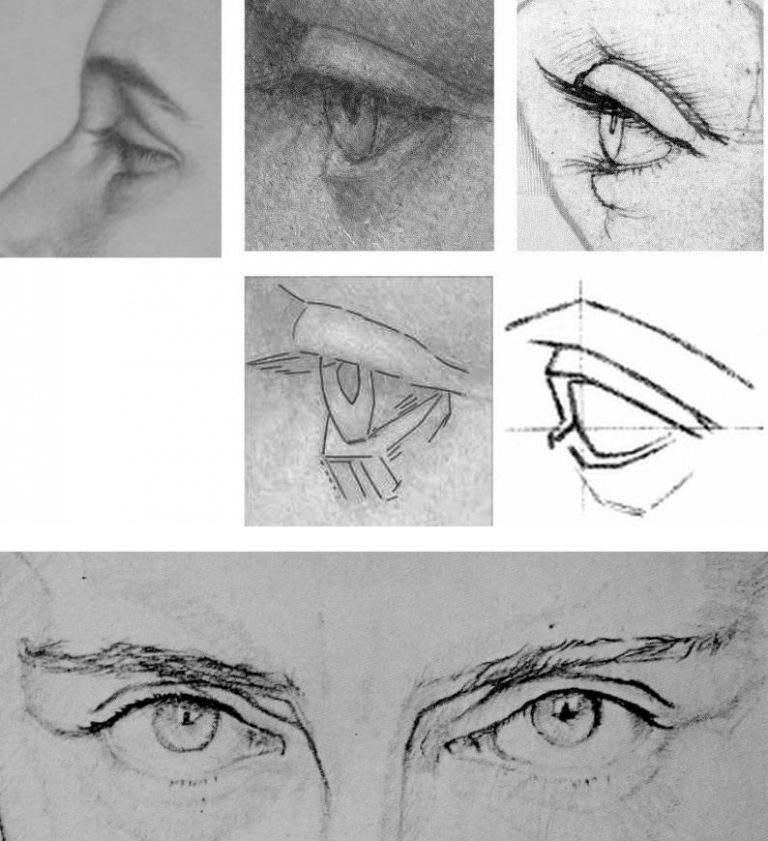

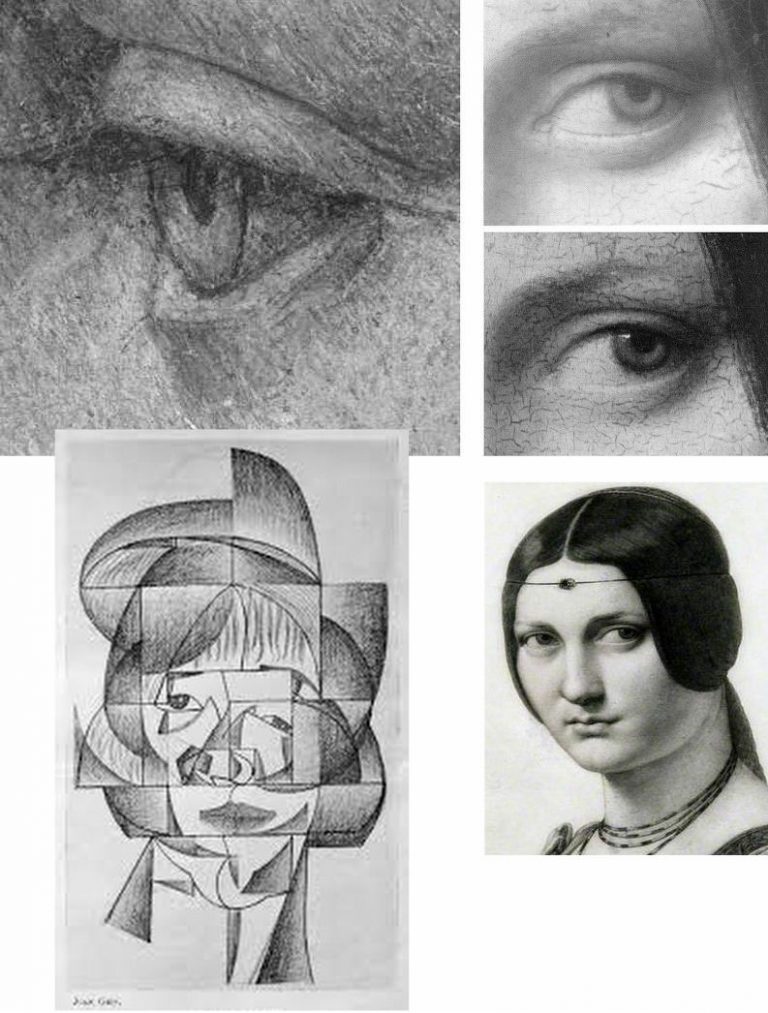

Above, Fig. 17: Left, a detail of “La Bella Principessa”; centre, a detail of the Karl Parsons Patricia; right, a drawing made by Michael Daley for the Independent newspaper (in illustration of the creation of a new rose).

In this comparison it can be seen clearly how “La Bella Principessa’s” eye breaks with the convention of classical profile portraits in which the eye is always shown looking straight ahead and never looking downwards or sideways. It should not be possible within the perspective conventions of the strictly profile face for the viewer to see the thickness of the lower eyelid. In the Daley rose drawing, the lower eyelid is also clearly visible but that is because a) the face is not seen in strict profile (both edges of the nasal channel are visible) and, b) the head is tipped downwards. As will be seen, the anomalous treatment of “La Bella Principessa’s” eye constitutes a disqualification.

Above, Fig. 18. When Karl Parsons’ eye of Patricia is placed as above top left, we see distinct similarities of curvature and the same forward looking gaze with the eye drawn by Leonardo shown in the top right. Once again, in the company of Parsons and Leonardo, “La Bella’s” eye (top centre) is a glaring odd-one-out with its straight-edged, planar manner of drawing. That very manner was commonly inculcated among art students at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century – as in the instructive published diagram seen above, centre right. Such an angular manner of drawing is nowhere to be found in Leonardo or his contemporaries, whereas, one can see distinct traces of that manner in the drawing of the male eyes above where features that would be drawn with curves by Leonardo are broken-down into short straight linked lines.

THE MARCHIGS

Above, Fig. 19: Left, a self-portrait drawn by Giannino Marchig in c. 1920 that was published in a journalist’s recent book on the “La Bella Principessa” drawing ( – see “Books on No-Hope Art Attributions”); right, an etching (mirrored) by Giannino Marchig of a lady, possibly his wife, Jeanne Marchig. Again, we see in the etching a draughtsman’s habitual favouring of angular, straight-edged and planar features. Additionally, we again encounter a profile portrait eye that is shown not convincingly set into the forms of the face.

As mentioned, the “La Bella Principessa” was sold anonymously at Christie’s, New York, in 1998. Twelve years later, Jeanne Marchig, the then widow of Giannino Marchig (who had worked as a restorer for Bernard Berenson and had restored a Leonardo painting), identified herself as the vendor in order to claim damages from Christie’s after sensational (but unfounded) reports that fingerprint evidence had proved the drawing to be by Leonardo and therefore to have been worth $100/150 million when sold in 1998.

However, and as we have reported, aside from the widow’s hearsay claims concerning the ownership of the drawing by the painter/restorer, the drawing possesses not a shred of recorded history in its supposed five centuries – and this is so despite prolonged searches made over the last nine years by specialist scholars and journalists. Giannino Marchig, initially a successful artist had hit hard times, became a restorer and an assistant to Bernard Berenson, had grown rich and acquired a collection of valuable historic works, but would not disclose – even to his wife – from whom, where or when he had acquired the drawing. Strenuous attempts by supporters of the Leonardo attribution to show that the drawing had been commissioned by the Duke of Milan for inclusion in a de luxe vellum book in 1496 have failed to find a single record of such a commission.

An early scholarly supporter of the drawing, Cristina Geddo, revealed that research made by penetrating imaging had disclosed that the back of this drawing (which cannot be seen by eye because the vellum sheet is glued onto an oak panel) carries “superimposed numbers…a written inscription…[and a] little winged dragon – at least that is what it seems.” No one has published those features; no one has offered a more detailed account of them or explained why they might have been present on what the drawing’s supporters claim (on no evidence) would have been a blank page in a luxury late 15th century commemorative book.

Above, Fig. 20: Top left, “La Bella Principessa’s” eye; top right, an eye from Leonardo’s painting La belle ferronnière, as seen, top, in an infra-red image that discloses the preparatory drawing for the curving, thin lower eyelid, and below it, the finished eye as painted by Leonardo. To a draughtsman, these eyes are as unlike as chalk and cheese and that of “La Bella Principessa” has nothing in common with any eye seen in Leonardo. It has greater affinities of style and means with the treatment of the eyes in the Juan Gris’ Cubist drawing, bottom left. Ingres’ pencil copy of La belle ferronnière shows how vividly dramatic and alive Leonardo’s eyes can be.

Scholars need not be draughtsmen but none would be harmed by practising drawing – and all would benefit by making copies of the works they address. An eye properly alert to stylistic traits is one capable of performing what we hold to be “forensic looking” (– see “Art forgers face new challenge from hi-tech authenticators”). Colnaghi has performed a service by unearthing Parsons’ Patricia. Unfashionable Arts and Crafts or no, Parsons merits attention, as his arresting portrayal of St. George at Fig. 21 below surely testifies?

Michael Daley, Director, 9 December 2019

Brian Sewell – Still Stinging in Death

The death on September 19th of the famously acerbic art critic Brian Sewell was generally marked by fair, balanced and sometimes touching obituary notices. For one of his critical victims, Susan Loppert, a signatory to the infamous 1994 “Gang of 35” letter calling for Sewell’s dismissal as the Evening Standard art critic, this seems to have been taken as a personal affront.

The now legendary Evening Standard letter of 5 January 1994 from thirty-five self-appointed contemporary art establishment worthies began pompously – “As members of the art world – writers, critics, artists, art historians, curators, dealers – we take the greatest exception to Brian Sewell’s writing in your newspaper…”, proceeded viciously – “His virulent homophobia and misogyny are deeply offensive, particularly the remarks made in the review of the exhibition Writing on the Wall”, and ended with pomposity, viciousness and self-pity: “We believe that the capital deserves better than Sewell’s dire mix of sexual and class hypocrisy, intellectual posturing and artistic prejudice”. This public attempt to silence a maverick critical voice was entirely self-defeating. As demonstrated below, it generated an explosion of support, catapulting the then 63 year-old art critic into a national prominence that would run for two decades.

This happy unintended outcome was, however, the exception to other manoeuvres in a bid to rig press coverage of deeply unpopular experimental art practices. A post hoc rationale for advancing against the press was given by the Tate’s director, Nicholas Serota in the 2000 Dimbleby Lecture with this plaint: “For in spite of much greater public interest in all aspects of visual culture, including design and architecture, the challenge posed by contemporary art has not evaporated. We have only to recall the headlines for last year’s Turner Prize. ‘Eminence without merit’ (The Sunday Telegraph). ‘Tate trendies blow a raspberry’ (Eastern Daily Press), and my favourite, ‘For 1,000 years art has been one of our great civilising forces. Today, pickled sheep and soiled bed threaten to make barbarians of us all’ (The Daily Mail). Are these papers speaking the minds of their readers?” Well, yes, of course they were, that is one of the things that sensible newspapers do. And that was why the articulation of such dissent posed a political threat to the contemporary art establishment’s ambitions.

COVERT MANIPULATION OF THE PRESS

The bid to unseat Sewell occurred when the Tate Gallery had become the greatest promoter of experimental art and was working closely with contemporary art dealers. In 1991 one such dealer, Jay Jopling, served on a secret Tate committee. When the editor of the art magazine Jackdaw, David Lee, later asked the Tate for the members of this shadowy committee, that gallery replied curtly that it could not say because no minutes had been taken. But why a secret committee in a publicly-funded registered charity? All businesses and institutions angle for favourable press coverage – that is why they employ large press departments. What additional purpose or purposes were best served secretly? Were there other secret committees at the Tate? Only two press accounts of this shadowy committee exist, and from these we learn that its express purpose was to plant stories to generate press coverage of, and foster interest in, what was widely reviled avant-garde art. Both insights stem from interviews with Jay Jopling when he was about to open the new White Cube gallery in Hoxton Square. The first, on 20 September 2002, was by Rose Aidin in The Guardian:

“Following a brief flirtation with film-production, Jopling started working with artists such as Damien Hirst and Marc Quinn, putting on warehouse-style shows from his Brixton home. When Nicholas Serota formed a think-tank upon his appointment to the Tate in 1991 [NB Serota had been appointed in 1988 – now some twenty-seven years ago!], Jopling was asked to join it. ‘I was very flattered to be included in this meeting to discuss how we got the newspapers to take contemporary art more seriously,’ he recalls. ‘Yet it seemed to me that if the tabloid press was only interested in ridiculing contemporary art, then get them to ridicule it properly, so that people actually take notice.

‘So we got the Daily Star to take a bag of chips to one of Damien’s fish in formaldehyde pieces which was then on show at the Serpentine and photograph it as the most expensive fish and chips in the world. Stunts like that forced people to know about the art and if they know about it, then that encouraged them to go and see it, and then they were forced to take a view. It certainly was a way of getting art into the public arena.'”

In another interview, “Thinking outside the square”, in the Financial Times on 21-22 September 2002, Lynn MacRitchie reported:

“Jopling recalls a ‘dark period’ when he was among a group summoned by Nick Serota to what was then simply the Tate to discuss how to get press coverage for contemporary art. At that time Jopling and his soon-to-be-star Damien Hirst, who proved a tabloid natural, were happy to go along with whatever the papers wanted – posing with a bag of chips next to the shark for the headline ‘The World’s Most Expensive Fish Supper’ was just one stunt. While Jopling concedes that the tabloids’ insistence on making ‘characters’ out of the artists went further than he had expected, the tactics, however dubious, worked – the British public, notoriously indifferent to contemporary art, was hooked…”

At the other end of the press, Tate-friendly art critics set about persuading their broadsheet newspaper editors that publishing comment articles and news page reports mocking avant garde art made their papers look down-market and “tabloid”. Both ploys worked: serious commentary articles questioning Tate policies were killed in the quality press, while in the tabloid press earlier “You call this art?” stories morphed into colourful tales of endearingly whacky new art world celebs “having a larf” at The Establishment. In no time at all, the one-time rebels were the establishment and they, like their dealers, made killings. Sometimes, the Tate’s secret manipulations of the press involved suppressing stories rather than planting them.

“DANGLED DOSH, UNDERWORLD CONNECTIONS… AND NO ARRESTS”

Above, Tate players, Sandy Nairne, left, Nicholas Serota, centre, and Stephen Deuchar, right, announcing the recovery of two stolen Tate Turners at a press conference in December 2002.

When the Tate lost two Turner paintings to thieves after loaning them to an insecure German museum in 1994, it later obtained permission from the High Court to buy them back from Serbian gangsters for a ransom of more than £3 million. Secrecy at the Tate went into overdrive when in 1998 Serota set up a so-called “Operation Cobalt”. The gangsters feared a police recovery action might be in operation. Although this was not the case (on the gangsters’ insistence the police had been “stood down” and the banknotes were unmarked), as a precaution, they released the paintings one at a time. When the first Turner was brought back secretly to London, the man who had negotiated the dangerous transfer of cash, Sandy Nairne, a signatory to the 1994 Sewell-Must-Go letter and the then director of the National Portrait Gallery, wanted to release the news. The Tate’s director, Nicholas Serota, refused on the grounds that by holding back until both pictures were recovered it would be possible to achieve a spectacular publicity coup. Hitherto, Serota said, most of the Tate’s “positive” press coverage had not been real news but, in his words, “merely promotional material”. Nairne recalled (in Art Theft, his 2012 book on the affair) that when stories began appearing in the British press “Nick [Serota] questioned me as to whether I was doing enough to ‘control’ those working for us and preventing anyone from speaking to the press…It then emerged that someone had talked to the senior crime writer on the Mail on Sunday [a sister paper to the Evening Standard]. He had heard that one painting was back in London, and he was keen to find some corroboration for this notion – something I wanted no one to know…” A high-powered press consultant, Erica Bolton, was hired on Serota’s advice and she prepared a dissimulating press statement in Serota’s name:

“November 2000 Turner Paintings

There has been much speculation over the years about the whereabouts of two paintings by J. M. W. Turner stolen in Frankfurt in 1994. And like the authorities in Germany, Tate has always been interested in any serious information which might lead to their recovery. But currently there is no new information, nor are any current discussions being conducted. Of course I remain hopeful that one day the paintings might return to the Tate.

Nicholas Serota, Tate Director“.

Nairne did not say whether or not the Tate had denied outright to the Mail on Sunday that one of the paintings had already been returned but, in any event, the dreaded article did not appear. As Nairne put it, the paper “did not publish and my fears about further investigative pieces, with imputations about ‘Serbian criminals’ receded.” The identity of the criminals had been disclosed in a 2001 book, The Unconventional Minister, by the former Treasury minister (the Paymaster-General) Geoffrey Robinson, who had bullied Lloyds’ insurance underwriters into allowing the Tate to buy back the rights for the paintings, should they be recovered, for only a small fraction of the £22 million insurance payout the gallery had earlier collected. After the final part of the ransom was paid and the second Turner painting was returned, no arrests were made. (For more on this saga, see Michael Daley, “Ransom or Reward? Part III”, the Jackdaw, January/February 2012, and our posts Questions and Grey Answers on the Tate Gallery’s recovered Turners, and Dicing with Art and Earning Approval.)

THE ELEVATION OF BRIAN

On 7 January 1994 the blow-back against the Gang of Thirty-five’s letter began on the Evening Standard letters page.

The Education Secretary, John Patten, wrote:

“I have read with dismay the letter signed by a number of the great and the good in the art world (5 January) attacking Brian Sewell. He shouldn’t be dismayed, but rather cheered…It’s not the whiff of censorship, nor the heavy scent of political correctness which pervades their letter, which concerns me, but its extraordinarily inward-looking nature. In other words, the attitude that cultural life is only for the self-styled cultured, a narrow group alternately puffing and then gently ‘criticising in context’ each other’s work…Their letter marks the barrenness and imploding nature of so much contemporary British intellectual and artistic life, with a few notable exceptions.”

Michael Daley wrote:

“Bravo, Brian. There have been signs for some time that members of our illiberal, modernist, visual arts establishment are becoming unnerved by their own self-constructed isolation. But for one critic, with one review, to derange and bag no fewer than 35 mewling, whining, Arts Council apparatchiks and awards recipients is a splendid achievement.

Long may Mr Sewell (and his Spectator comrade-at-arms Giles Auty) speak for the thinking public and the majority of practising artists. Please give him all the space he needs – the job is urgent. And overdue.”

Vaughan Allen wrote:

“What a laughable reflection on contemporary metropolitan culture was the whingeing letter by its self-appointed spokespeople (Letters, 5 January). And how arrogant to open with ‘As members of the art world’ as though this entitled them to some kind of privileged treatment. Since the sad death of Peter Fuller, Brian Sewell has emerged as one of the few critics consistently to resist the hijacking of the arts by politically correct trendies and mindless charlatans. His denunciation of the pretentious rubbish regularly paraded as art by London’s curators, dealers and critics is a welcome breath of fresh air. Without it Londoners risk suffocation by endless phoney art propaganda and pseudo-intellectual pyscho-babble beloved by a media desperate to foster any artistic fad no matter how imbecilic. Reading down the list [see below] one cannot but help notice the number of indignant signatories who constitute the capital’s incestuous and self-perpetuating art-scene maffia. No wonder they resent Mr Sewell for exposing their specious, life-diminshing but fashionable cultural values. For it is the public’s very acceptance of these warped criteria that they depend on to guarantee their inflated incomes and even more inflated reputations.”

On 14 November 1994, James Beck wrote:

“I read with relish Brian Sewell’s extraordinary ‘Down with bilge, gush and greed’ piece (10 November), nodding my head in agreement after every paragraph. There is no doubt that such views, effectively and brilliantly articulated, are annoying to the art world’s establishment, which has been running a marathon of naked emperors for decades.

Art criticism, and, I would add, official art history, is at the same low ebb, and they feed on and support each other with the aid of colossal sponsorship from international business and foundations, many of them America-based, with limitless funds.

Only with the constant and intelligent criticism by people like Brian Sewell can we hope to open honest debate on the issues that count.”

THAT WAS THEN, THIS IS NOW:

Looking back, two decades on, what effect did that affair have? And, more personally, how is Sewell now regarded on his departure? The television campaigner Mary Whitehouse suffered decades of vilification until the feminist writer Germaine Greer conceded that she had had a point all along when campaigning against gratuitous televised depictions of (male) violence against women. So Sewell was lucky to have his vindication arrive so fast. But on his death it would seem that, for the signatories of the Sewell-Must-Go letter, time brings no reprieve. Even in his grave, the still-righteous letter-writing collective casts him as wrong, vile and repellent, and themselves as both morally vindicated and art-politically triumphant. The generally balanced and charitable tone of the obituary notices pushed one of the original letter’s signatories (- in fact, we now learn, its author), Susan Loppert, into public rebuttal mode. Protesting against Jonathan Jones’ 21 September article “Brian Sewell was Mr Punch to modern art’s Judy”, Ms Loppert took affronted sisterly umbrage on behalf of Judy in a letter to the Guardian:

“As the author of the ‘naive’ letter by ‘art world types’ published by the Evening Standard in 1994 objecting to Brian Sewell’s attitude to contemporary art, I’d like to clarify why the letter was written. Sewell was an art historian whose main area of expertise was old master paintings. He was hostile to and ignorant about contemporary art, yet at the Standard he wrote lengthy reviews giving vent to his splenetic old fogeyism, virulent homophobia (surprising given his own homosexuality) and misogyny. The review that prompted our protest was a 3,000-word diatribe inveighing against a small exhibition at what is Tate Britain of work by female artists, selected by female curators, the catalogue with contributions from female writers. Sewell dismissed it all as ‘a show defiled by feminist claptrap’, in particular a ‘frightful’ female nude by Vanessa Bell that was so ‘ugly and incompetent, it could hardly be the favourite of even a purblind lesbian’.

The letter did not demand that Sewell be fired, as was erroneously claimed at the time. Stewart Steven, editor of the Standard, had told me that Sewell had been hired to be offensive without being libellous, that his work was deliberately targeted at the lowest common denominator: ‘Essex Man – the strap-hanger on the Ongar Line’. Since we recognised that ‘very occasionally, [Sewell] says something perceptive on subjects where he has some expertise’, we felt that the paper should have two art critics: one for art dating from the early 1900s with its dreaded abstraction, and Sewell for what he called ‘traditional’ art.

The 35 signatories included Bridget Riley, Rachel Whiteread, Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, Michael Craig-Martin, Marina Warner, Richard Shone, Christopher Frayling, George Melly, Angela Flowers and John Golding. Perhaps Jonathan Jones was right to say we were naive, but he’s wrong if he thinks ‘Sewell really scared [us]’. What we objected to was his deliberate cruelty and viciousness, and that he was, in the words of your obituary (21 September), ‘puffed up’; like his invented Edwardian voice – and like so many works of art – he was a fake. In the end though, as Jones notes, none of Sewell’s flailing at windmills stopped the inevitable triumph of modern art. Is Sewell turning in his bile-filled grave?”

Note the unreconstructed presumption: “We felt that the paper should have…” We, another respondent, and Ms Loppert herself, replied in letters to the Guardian (3 October) – see “Brian Sewell spoke timely truth to power”. Our letter reads:

“Susan Loppert’s defence of the notorious gang of 35’s attempt to unseat Brian Sewell at the Evening Standard is as disingenuous as her present attack on him is tasteless. Tasteless, too, for her to crow ‘none of Sewell’s flailing at windmills stopped the inevitable triumph of contemporary art. Is Sewell turning in his bile-filled grave?’.

Inevitable triumph? The triumph of all contemporary art – or of just the Tate/Arts Council-sanctioned varieties? In truth, much of the strongest support for Sewell came from contemporary artists of non-state-approved persuasions. I recall this well, having been one of the first to defend Sewell in the Standard: ‘There have been signs for some time that members of our illiberal, modernist, visual art establishment are becoming unnerved by their own self-constructed isolation. But for one critic, with one review, to derange and bag no fewer than 35 mewling, whining, Arts Council apparatchiks and awards recipients is a splendid achievement.

Long may Mr Sewell (and his Spectator comrade-at-arms Giles Auty) speak for the thinking public and for the majority of practising artists. Please give him all the space he needs – the job is urgent. And overdue.’

And so there were but, as it happened, the illiberal gangs did win out, modernism has triumphed and Serota has been anointed (Mugabe-like) Tate director-for-life. But goodness, how close it was then and how deliciously rattled they were – and still are, if Ms Loppert is any indication.”

I should not, perhaps, have mentioned Auty in 1994. He too was attacked at the Spectator by partisans of the Tate and a trendy gallery (see below). Some months later, and again in the Spectator, another of the thirty-five signatories, Richard Shone, then a deputy editor of the Burlington Magazine, attacked every single non-trendy writer on art, including Auty in his own paper – he was branded “didactic”. John McEwen of the Sunday Telegraph was dubbed “world-weary” and so forth. Shone, just like Loppert, demanded a different kind of press and called for a “shake-up of the way fine arts are treated in the press” – even as he admitted that there were “wider individual sympathies for [Sewell] among 20th-century artists than he is given credit for”.

A PAINTER AND A PAINTER/CRITIC IN DEFENCE OF SEWELL:

TAKING OUT A CRITIC ~ THE 35 SIGNATORIES:

Kathy Adler, Don Anderson, Paul Bailey, Michael Craig-Martin,

Graham Crowely, Joanna Drew, Angela Flowers, Matthew Flowers,

Pofessor Christopher Frayling, Rene Gimpel, John Golding, Francis Graham-Dixon,

Susan Hiller, John Hoole, John Hoyland, Sarah Kent,

Nicholas Logsdail, Susan Loppert, Professor Norbert Lynton, George Melly,

Sandy Nairne, Janet Nathan, Prue O’Day, Maureen Paley,

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, Deanna Petherbridge, Bridget Riley, Michele Roberts,

Bryan Robertson, Karsten Schubert, Richard Shone, Nikos Stangos,

Marina Warner, Natalie Wheen, Rachel Whiteread.

THE WIDE-RANGING CONSPIRACY TO UNSEAT DISSIDENT VOICES

Richard Shone’s assault on politically unacceptable writers prompted a further brace of letters to the Spectator (28 May 1994):

“Out Shone”

“It is heartening to see how jumpy and ratty members of our illiberal, modernist visual arts establishment (for example, Richard Shone, Arts, 21 May, Anthony Everitt, Guardian 16 May, Richard Dorment, Daily Telegraph 14 May) are becoming. Having seized all outlets from the Tate Gallery to the Royal Academy, the Arts Council to the art schools, the Late Show to Time Out and the Burlington Magazine, today’s mandarins seem to be recognising that their grip is precarious. The outside world will not be bullied into believing that commonplace materials (like brick, chocolate and dead animals) can, by fiat or alchemy, be converted into bona fide works of art. Rare, professionally dissenting voices (such as your art critic Giles Auty and the Evening Standard’s Brian Sewell) are increasingly seen, therefore, as menaces who must be removed. Fortunately, the present establishment campaign to this end is proving spectacularly counter-productive. The Gang of Thirty-five’s notorious call for Sewell’s sacking led to an embarrassing avalanche of support for his writing. Mr Shone’s linked attacks on your art critic and on ‘visually illiterate’ art editors is similarly inept: Auty’s authority and influence as a critic is underwritten precisely by his long and first-hand familiarity as a painter with the mechanics and the grammar of the art. There are visual illiterates at large but, mercifully, they rarely find space in The Spectator.

What really sinks Shone’s case, of course, is its self-contradictoriness and hypocrisy. After pious calls for disinterested criticism in general and for a plurality of voices, he ends with the prescriptive demand that critics present exclusively ‘enthusiastic account[s] written with warmth for the subject’ – no cut, no thrust, no scepticism, just remorseless sycophantic, promotional gush.

That such should come from a deputy editor of the Burlington Magazine says much of the health of our arts establishment and of the arrogance of its members. But it also betrays a fatal weakness: if, nearly a century on, modernism truly remained a vigorous, healthy and life-enhancing force, it would hardly require the present ugly, repressive machinations being made on its behalf, would it?”

Michael Daley

“Possibly the long article written by Richard Shone about the current state of art criticism needs placing in a wider context. Mr Shone was one of the signatories to a recent letter to the editor of the Evening Standard calling for the sacking of their art critic Brian Sewell. My own editor has recently received letters from two employees of another of the signatories, Karsten Schubert [the dealer], calling for my removal from this paper. The grounds are that I am not sympathetic to the sort of art that Mr Shone and his kind find quite wonderful, as exemplified by the current exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery ‘Some Went Mad, Some Ran Away’, for which Mr Shone has written a eulogistic catalogue essay. The fact that I think this last is composed largely of hot air, however elegantly written, will not be causing me to write to the editor of the Burlington Magazine, of which Mr Shone is deputy editor, calling for the latter’s instant dismissal. The fact that I do not do so may reflect differences in my character as well as writing from those of Mr Shone. I do not feel any need to defend myself against any of Mr Shone’s charges except one, being content to let 428 articles I have written for this journal on a wide variety of artistic topics, including the old Masters, make my case.

Mr Shone hints that critics grow increasingly unsympathetic to the sillier excesses of the avant-garde as they grow older. This is not my case at all; if anything I have mellowed. The logical conclusion to this argument is that only an unintelligent teenager could write rewardingly about unintelligent teenage art. In spite of Mr Shone’s boyish appearance, I would be alarmed to believe he thinks anything so silly.”

Giles Auty

Richard Shone and I have never met, and I know as little of him as he of me. Had his biographical notes in ‘The Art of Criticism’ suggested that I have reached the sad end of a once-promising career, none could disagree, but he preferred mischievous distortion for the sake of irony, omitted much of substance from my early years, and betrayed a museum’s privacy – fine and fair behaviour for the deputy editor of a scholarly magazine. He mocks my contribution to televised advertisement, but it seemed to me a more honest means of putting jam on my gingerbread than the ekphrastic bilge written for dealers’ catalogues by most other critics (and is far less well paid). He praises Richard Dorment as an exemplar to the errant – Dorment, who in praising Damien Hirst, described himself as a ‘thrill junkie’. This is, alas, a level of critical insight and language quite beyond me.”

Brian Sewell

“PEOPLE LIKE US”

At the end of the Second World War, patricians like Maynard Keynes and Kenneth Clark, recognising that the future in Britain would be socialist, turned a modest highly cost-effective little organisation CEMA (- the 1940 Committee for Encouragement of Music and the Arts) that had taken art and performances around the country during the war to improve morale, into what became today’s sinister instrument of state control for the arts – The Arts Council. With tax on earnings peaking at over 90%, the logic then was impeccable: future art patronage could come only from the state, no longer from rich individuals. This being so, as Clark put it, “people like us had better be sure to get in there to run it”. At first, the Council busied itself with good and useful works – Clark himself had generously supported fine artists like Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, and John Piper out of his own pocket. But a fateful step was taken in the 1970s when a worthy Northern adult education academic, Roy Shaw, was appointed Secretary General of the Arts Council. Shaw took the disastrous “managerial” view that the Council’s chief function was to create a secure and proper “career structure” for professional arts administrators. This resulted in an explosion of professionally pro-active but artistically-impoverished middlemen – see below. Because the Council was entirely state funded and precisely because its managers lacked the cultural confidence or judgement of a Clark or Keynes, the Council set its face against appraising art and artists in terms of quality. Instead, it took its role, simplistically and perversely, to consist of aiding that which was unlikely ever to find commercial or private funding. Thus, those who made wilfully unintelligible works, or transparently political and provocative ones or, above all, disembodied, “conceptual” and inherently un-saleable works, were ipso facto favoured over those working in any traditional medium and genre. In a blink, the Council switched from assisting and disseminating quality, to being an ideologically coercive enforcer of its own no longer-artistic socio/cultural purposes.

For all of its new professional clout and financial muscle, the Council’s widely mocked and disparaged bias in favour of pretentious novelty and socio-cultural provocations carried clear political dangers. The Council could not afford to become a public laughing stock for the art it was propagating if its own future was to remain politically secure. In addition to warping and constricting the varieties of “acceptable” art, the Council thus itself acquired a vested partisan interest in restricting the range of art-critical discourse. To impart a spurious respectability on its favoured recipients, the Council established a nation-wide chain of galleries in which the right sort of artists could be exhibited and written about by the right sort of art critics. It became possible for someone like Nicholas Serota to leave university and pass swiftly up the food chain of Arts Council funded venture and galleries – namely, becoming chairman of the new Young Friends of the Tate in 1969, a regional Arts Council officer in 1970 and then, respectively, director of MoMA (“Modern Art Oxford is extremely grateful to Arts Council England”) in 1973, the Whitechapel Gallery in 1976, and, since 1988, the Tate Gallery as was, Tate and Tate Modern today, picking up a Knighthood in 1999 and being made a Companion of Honour in 2013.

BUT WHAT IF?

If Serota has led a charmed professional life within the Arts Council family, it has also been one dogged by controversy – as over the notorious buy-back of the two ransomed Turners described above. He obtained funding from the National Art Collection Fund for purchasing the work of a serving trustee by submitting false information. In 2006 he was ruled to have broken Charity Law with many other such purchases of trustees’ work. In 1999 opposition to his rule at the Tate led to the founding of a dedicated group of opponents, The Stuckists. Many figurative artists have called for him to be sacked. He has generated a school of satirical novels. See Ruth Dudley Edwards’ Killing the Emperors – which author has held Serota to have “used his power as head of the Tate galleries to promote talentless self-publicists and to encourage the proliferation of the ugly and the pointless”. Alex Pankhurst’s Art and the Revolutionary Human Fruit Machine chronicles the collisions between modern art’s titans and small town sceptics.

The 1994 letter seeking to remove Sewell was produced at a time when the art critical running was being made by a small group of critics who were entirely immune to the appeals of state-sponsored avant-gardism. In addition to Sewell in the Evening Standard, the painter/critic Giles Auty was writing in the politically influential Spectator. The then recently deceased Peter Fuller, having migrated from both the far left and avant-garde art had been made art critic of the Daily Telegraph in 1989 and from 1987 had been the founder/editor of the heavy-weight, pro-figuration glossy magazine Modern Painters. The Art Review had been transformed since 1992 by David Lee, a vigorous champion of figurative art and artists and a relentless critic of Serota and the Arts Council. Between 1992 and 2001, when the Art Review was acquired by a new owner who wished “to get on board with Saatchi”, Lee had more than tripled the circulation and rallied many supporters. Not wishing to join the then ascendant Charles Saatchi band waggon, Lee left to found his own modestly-produced, proprietor-free, success d’estime – the still-thriving magazine Jackdaw. (He will be writing on Sewell, his great personal generosity, and other matters in its next issue.) At that time, Nicholas Serota was only six years into his reign and had yet to perfect his chillingly autocratic rule at the Tate and its proliferating satellites. However, in the event, the combined and interlocking institutional forces against the small dissident band did prove insuperable. In addition to Fuller’s death at a tragically young age in a car accident in 1990, Auty was to emigrate to Australia. It is remarkable today that notwithstanding the immense institutional power of the modernist establishment and contrary to its barrages of propagandistic hype, public disdain for “cutting edge” art forms remains firm and resolute. That this is so is demonstrated on the rare occasions when its strength is put to some objective test.

In 2003 Sir Roy Strong, a former director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and ArtWatch UK’s director Michael Daley, took part in a live BBC Radio 4 “Straw Poll” programme debate against a minor Arts Council regional apparatchik and the Saatchi-friendly (but short-lived) editor who succeeded David Lee at the Art Review. The motion under debate was “Is contemporary British Art more about money than art?” and it was supported by Strong and Daley. Each speaker was invited to make a short opening statement. Daley’s was:

Contemporary British Art is more about money than art because much of it is not about art, as such, at all. Its leading figures prosper by playing anti-art games, by flouting artistic norms, intellectual standards and even common notions of human decency.

In Britain today, an arts administrative caste, through the Arts Council and its interlocking client organisations, has rigged the contemporary art market and subverted art practices by displacing aesthetic criteria with social or political ones. Officially-approved artists now swim in a sea of subsidies, free of any need to demonstrate individual artistic skills, original thought, or sensitivity. Ideas can be begged, borrowed, stolen or supplied directly by dealers. The execution of these appropriated “ideas” is frequently farmed out to unsung technicians.

There is, of course, a glaring logical problem with the present system: if such things as an unmade bed, an enlarged toy, or a collection of navel-fluff can now count as art, then anything and everything can be art – and if everything is art, nothing is.

Two years ago, a single sheet of stained lavatory paper was presented by a Young British Artist as a self-portrait and sold at auction for £1,500. That is a lot of money for not very much art.

The debate – which was lively – was held before an invited audience at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. It was drawn from “Friends” of both the Ashmolean and the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford. When a vote was taken among the invited studio audience, the motion was narrowly defeated. The next day, the sequel programme on Radio 4 consisting of listeners’ comments on the live debate was broadcast. At the end of it a poll of the programme’s listeners was announced. Radio 4 listeners are acknowledged to be comprised of the most educated and culturally/politically sophisticated variety in the UK. With that much larger and geographically dispersed audience, the motion was carried by 86% to 14%. The slur that opponents of the contemporary art establishment were benighted “strap-hangers” on the London underground had fallen at the first objective hurdle.

“WITHIN A FAIRLY SMALL WORLD…”

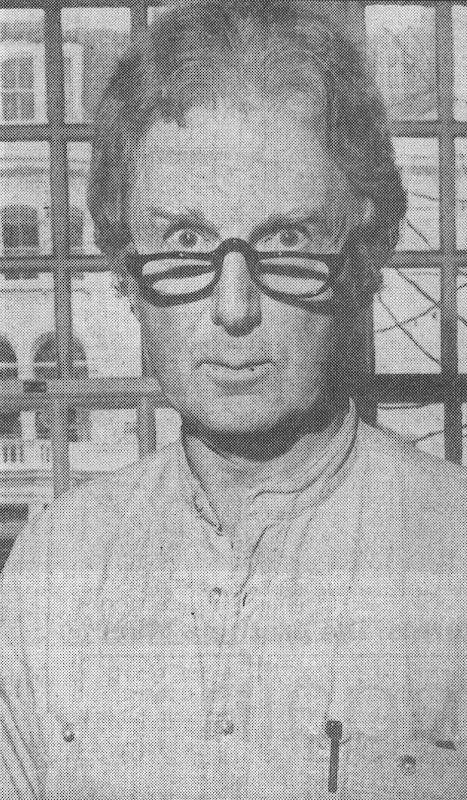

Private Eye carried the cartoon above over the exposé below:

On 24 June 2014 Sir Christopher Frayling (right) and Sir James Dyson (left) at the opening of Frayling Building – aka a renamed old block – at the Royal College or Art. (See: “The RCA Renames Kensington Common Room Block Honouring Former Rector Frayling”.)

On 22 December 1994 Professor Christopher Frayling, a signatory of the Stop Sewell Campaign, rose in the Evening Standard to defend the competence and the probity of the Arts Council’s visual arts panel (which he had chaired) against an attack from Brian Sewell. To the charge that the Arts Council was rewarding its own administrators, Frayling played a bureaucratic hand familiar to us – brushing off charges while confirming the evidence on which they rested:

“The Visual Arts Panel is criticised for being populated with ‘nobodies’. In fact it consists of an excellent committed group of well-respected artists, curators, historians and arts administrators and is chaired by Sir Richard Rogers. He [Sewell] implies that members of the Visual Arts panel have sometimes been direct beneficiaries of grants awarded by the Arts Council.

There are two basic misunderstandings here: first, the Arts Council, in general gives grants to institutions not to individuals (and it is up to the institutions to decide how they then distribute the funds); where it does give grants to individuals there are several formal mechanisms to ensure that those who have a direct or indirect interest take no part whatsoever in any decisions that might affect them. To take one of Sewell’s examples, the award to the Prudential for the Prudential Awards for the Arts. Anyone who has visited that gallery and seen its stunning transformation will not cavil at this acknowledgement. It is invevitable, if the Council seeks advice from the very best sources within a fairly small world, that some of those sources will sometimes also be recipients of public money.”

Yes, indeed, they sometimes are – and it came as no surprise to us for this particular overlap within the exceedingly small world of publicly-funded arts merry-go-rounds to be confirmed. In 1981-82 we had encountered precisely the same pattern of explanation/justification/apologia from another of the Sewell letter signatories, Joana Drew, the head of visual arts at the Arts Council. Where Frayling accused Sewell in 1994 of having produced “an article full of factual errors”, in 1982 Joanna Drew had claimed that my accounts of Arts Council subsidies (published on the letters page of the magazine Art Monthly) contained “inaccuracies of detail”. This routine bureaucratic ploy had been parodied in the advice given to a Government minister by a mandarin civil servant in the television programme “Yes, Minister” (- “Accuse them of inaccuracies of detail, Minister. We’ll find them – there are bound to be some”). My researches in art funding had come about by accident.

In the late 1970s Joanna Drew asked the painter R. B. Kitaj to commend artists to receive Arts Council grants. He had been taken by my work and wrote a generous letter of commendation to the Arts Council and so, in some hope, I applied for the first (and last) time for an Arts Council grant. Despite submitting the invited letter of commendation from Kitaj, my application was unsuccessful. The letter of rejection identified the recipients and I noticed that the awards in what was a national scheme had been swamped with abstractionists, performance artists, conceptualists and such. The Arts Council threw a press lunch so that journalists (and unsuccessful applicants) might meet the winning artists. At this lunch, with a few like-minded artist friends, I staged a small protest. After Ms Drew’s speech to the press, we handed out (silently) a sheet of paper with a list of questions concerning the manifest artistic biases of the awards scheme. We were attacked the next day in a newspaper by an art critic who defended the Council against the disruptive “nobodies”. Had he spoken to any of us at the time he would have appreciated that he had written a glowing piece appreciation of one of the protesting artists for a catalogue to his recent one-man show at the Marlborough gallery. Having made our point and registered our protest that had seemed the end of the matter. I carried on teaching part time in two London art schools and continued to read Art Monthly.

A few years later a regional Arts Council officer on the Greater London Arts Association complained in Art Monthly of “underfunding”. Having noticed that all subsequent awards winners were of the same limited artistic persuasions as those encountered earlier, I sent this short letter to the magazine:

“Given that the GLAA has now noticed that there are indeed 18,000 practising artists in London (AM 43), would it not be helpful if they stopped giving their grants to the same twenty?”

It took the Council four months to reply. In the July/August 1981 issue of Art Monthly, the (unrepentant) officer claimed that my chide of repeated funding was “inaccurate” and that “A more justifiable criticism of GLAA’s grant aid might well be that we spread our butter too thinly. We certainly do not spread jam on one corner of the slice”. Reeling with incredulity I went off and bought copies of past annual reports, and began collating the accounts of the various awards schemes, the findings of which I reported in a letter in the next Art Monthly.

JAM FOR THE FEW

Far from it being the case that only two artists had ever received more than one GLAA award, as had been claimed, I had identified no fewer than 13 artists who had received two or more awards in the previous three years alone. Four had received two awards in the same year and one had received two awards in each of the previous two years. Taking the longer period from 1973-4 to the (then) present, I found that eighty-three artists had received two or more awards, thirty-five had received three or more awards, twenty-four had received four or more, eight had received five or more, four had received six or more, one had received seven, and one – who had been successful in 1978-79, the year in which I applied – had received nine awards. Many of this lucky band had received awards when they themselves, their spouses, their partners or their colleagues were judging the schemes: “Michael Kenny is also a member of a rather more select group of artists, namely those who have, while serving as judges on awards schemes, themselves received awards – a feat achieved by Kenny [then six awards in total] in 1976-77 and by Michael Craig-Martin [a signatory to the Stop Sewell letter] and Tess Jaray in 1975-76.” It was common for artist x to make an award to artist y who, on becoming a judge, made an award to artist x. The correspondence of discovery ran for months (when the bemused editor, Peter Townsend, removed the bails, he noted that the exchanges had run to 582 column inches). To every denial from Council officers I presented fresh and further corroborating evidence. I was able to show, for example, that in the previous year, of twenty recipients, three-quarters were receiving their second, third, fourth, fifth or sixth awards. This game of “pass-the-parcel” was not an easy system for outsiders to enter. When wrongly charging me with inaccuracies, Joanna Drew made errors of her own. On scandals connected with the composition of the judging panels, she said that only five people had served as judges twice and one three times. I showed that nine had served twice, seven three times, four four times, two six times. One had served seven times and one had – at that moment – already served eight consecutive times.

Establishing the prevailing patterns of patronage within awards schemes from the Council’s own records was tedious but easy. I was taken to task in Art Monthly by a correspondent who claimed that I’d missed all “the fat cats” but who declined to identify them and proposed to carry out no research of his own. There were other dimensions to the culturally deadening and warping ideological biases of the Council (see below). One was the extent to which even private galleries and public commissions were being brought into ideological line by the wheeze of “matching funding” schemes. Shortly after finishing the researches I was offered an exhibition by a private gallery in London but it came with strings: I should apply to the Arts Council for support for a travelling exhibition (around Arts Council-sponsored regional galleries) at the end of which the show would be brought to a concluding exhibition at the London gallery, all framing and promotion costs having been met by the Council.

Having stumbled into the grossly mismanaged system of awards for artists it would have been temptingly easy to take the MacGuffin for the plot but in the March 1982 Art Monthly we put the grubby dispensations in their proper institutional and ideological contexts. First, we explained, a sense of proportion was needed: “The awards schemes have engendered hostility out of all proportion to their actual cash values. Council spends, for example, more on the pension scheme for its own central staff (£205,138 in 79-80) than it gives as awards to all visual artists combined.” It spent over twice as much on central staff travel and subsistence allowances as on all painters, sculptors and print-makers combined. The sum spent on all public art throughout the land was barely half that spent by the Council on its own “publicity and entertainment”. A massive switch of resources from artists to administrators had taken place. In the previous four years grants to artists had been halved while those to administrators had tripled. Self-interest was manifest as in all bureaucracies but even this trait did not constitute the root of the Council’s cultural perniciousness.

THE POISON OF STATE SUBSIDISED ARTS

This root, we explained, lay in a fatal ambiguity in the Council’s role as the most powerful artistic patron in the country:

“In its least contentious (and earliest) guise the Council was simply a purveyor of subsidy to the arts: the means by which a culturally responsible society augments the inadequacies or stringencies of private means to support its artistic life. But increasingly, and more and more explicitly, the Council has taken on the role not simply of almoner but of cultural commissariat […so as] to seize outright the possibility of actual intervention in cultural life. It has come to portray itself as a force for initiation and perpetration of artistic trends, for bestowing artistic accreditation, for explicitly political and and sociological direction of artistic activity.”

Bad as the situation seemed back then, worse was to come. The model I examined proved to be but a maquette for what would follow as state and Lottery monies poured in. What was started as an aid to art and artists at a time of national penury morphed into an instrument of control, direction, manipulation and subjugation during times of unimagined plenty. For two decades or more Brian Sewell wrestled with the consequences and legacies this cultural leviathan (as he did also with the Tate and others). It is not really difficult to see why so many felt that he had to be stopped at any price, is it?

Michael Daley, 6 October 2015

POSTSCRIPTS…

1) On the above-mentioned anxiety felt by the trendy establishment at the scale of opposition to its beliefs and actions, we note that in 2005 the critic Richard Cork confessed: “Even so, we would be foolish to imagine that the battle has been completely won. I still meet people who say they love Tate Modern’s spectacular building, along with the views it provides. But then they declare that the art inside is rubbish…and they think I am mad to find anything of interest on display in there. Deep-seated suspicions continue to fester. I remember the Tate director’s striking lack of elation a few months after the gallery opened. ‘Many young people are interested in the visual arts’, said Sir Nicholas Serota, ‘but I’m conscious that a huge part of the public remains sceptical about modern art. Whether it’s people in positions of power, or the many letters I receive that complain about < lack of standards > in the art displayed at Bankside, a lot of people clearly find it difficult to live in the present.'” (- “People ask: ‘But is it art?’ Yes, actually, it is ~ Richard Cork springs to the defence of modern works”, The Times, 2 March 2005.)

What an extraordinary conceit/delusion it is to maintain that unless one likes and admires the kind of works that people like Serota and Cork promote, one is not living in the present. Has this man been in charge of a national institution for twenty-seven years, while harbouring the belief that most people in the country are living, zombie-like, outside of their own time?