Defending the Indefensible Part I: The National Gallery’s Tangled Rubens Web

1) “I know gossip about staff and trustees and stories connected with acquisitions I don’t think I’d better share.”

– Martin Wyld, the National Gallery’s retiring Head of Restoration in the January 2010 Museums Journal.

2) “Rubens’ Samson and Delilah is a large scale, early and entirely autograph painting of a kind the National Gallery previously lacked.”

– Michael Levey, the then-Director of the National Gallery, in the 1983 Rubens Acquisition in Focus exhibition catalogue.

3) “The Samson and Delilah was planed down to a thickness of about three millimetres and set into a new blockboard panel before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 and so no trace of a panel maker’s mark can be found.”

– Christopher Brown, the National Gallery Senior Curator, Flemish Paintings, in his 1996-97 Esso-sponsored National Gallery “Making and Meaning” exhibition catalogue Rubens’s Landscapes“. (Emphasis added.)

4) “Rubens’ panels sometimes bear the branded or carved mark of the panel maker, an example in the National Gallery being the Portrait of Susanna Lunden… unfortunately, as David Bomford has described, the back of the panel of the Samson and Delilah had been planed-down to a thickness of only about 3 mm and then the whole set into [sic] blockboard before the picture was acquired by the National Gallery, so any such marks would have been eradicated.”

– Joyce Plesters, the then-Head of Science, in the 1983 National Gallery Technical Bulletin. (Emphases added.)

5) “The treatment of Cima’s Altarpiece carried out during the 1970s and 1980’s was a rare modern example of a process that was extensively practised (often unnecessarily) in the 18th and 19th centuries – the transfer of a painting to a new support. It is nowadays only carried out in the last resort, when all other attempts at treatment have proved unsuccessful.”

– David Bomford, National Gallery conservator and author, in his 1997 National Gallery Pocket Guide: Conservation of Paintings. (Emphasis added.)

6) “Questions have been raised about aspects of the physical state of Rubens’s Samson and Delilah since its purchase by the National Gallery at auction in 1980… Recent research, however, has yielded some answers to the questions of when and why the painting may have gained this alien backing.”

– David Jaffé Christopher Brown’s successor at the National Gallery, August 2000, Apollo ‘Rubens back and front’. (Emphasis added.)

FROM THE FIRST CRITIC:

7) “Jan Bosselaers had inspected NG6461 up-close in 1977, and then again in 1980. Given his familiarity with the painting, I asked him specifically about its back. Bosselaers grabbed a piece of paper and drew a grid of three vertical lines crossed by three horizontal ones. He looked at me. ‘A cradle!’ I gasped. ‘Yes’, he said, ‘it was a cradle.’”

– Euphrosyne Doxiadis: Painter/author, in her NG6461 The Fake National Gallery Rubens (p. 117. Emphasis added.)

MICHAEL DALEY WRITES:

PART I: A REFORMULATED SAMSON AND DELILAH ACCOUNT THAT STILL DOES NOT STACK UP

With expensive and massively hyped works bought by major public institutions it would seem that acknowledging errors is an art-political impossibility. Such institutional obduracy is longstanding. In 1966 the art dealer René Gimpel noted that “The museums are even more intent than the collectors on defending their fakes or their mistaken attributions” (- a 1929 entry in his Diary of an Art Dealer.) Today, with the Samson and Delilah, the National Gallery stands in triple jeopardy: its initial error of art historical judgement has been compounded by both an apparent falsification of material evidence and a decades-long withholding of contra-testimony in its possession.

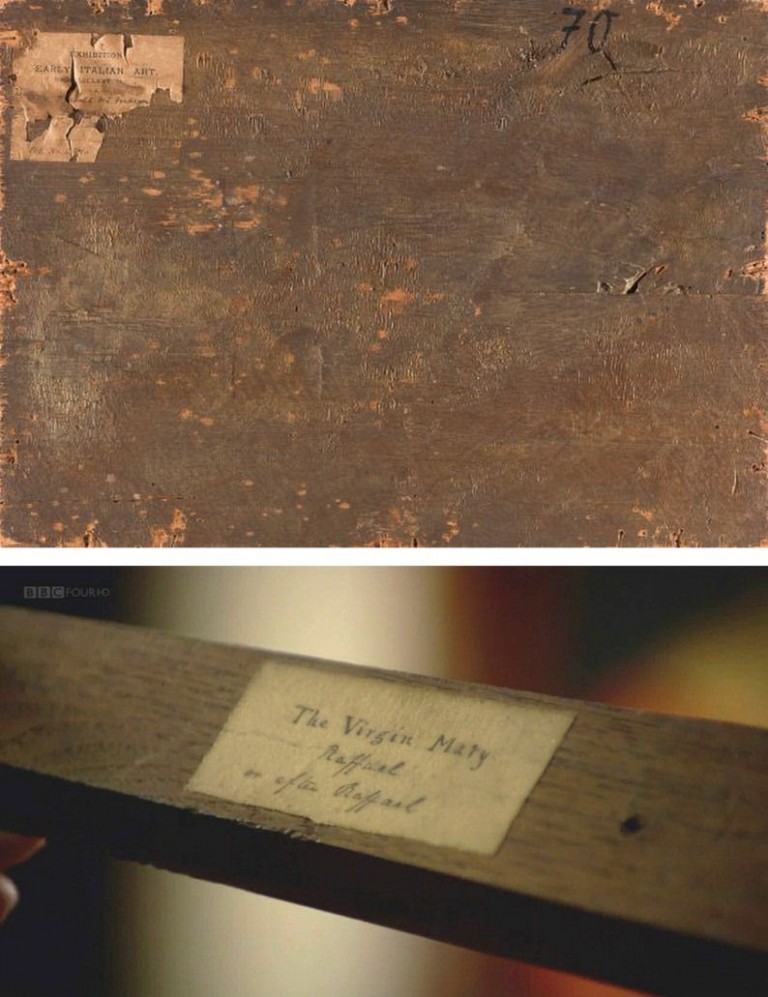

The affair began in 1980 with a deceptive unanimity of assurances and a dearth of disclosures. Today, on interrogation of the picture’s traits, provenance and technical literature, a sleight of hand emerges: the back of its panel and the historical evidence it bore were removed by the Gallery and not by earlier, unknown others, as the Gallery has claimed since 1983 – and blatantly claimed despite its possession of flatly contrary key historic documents. (See Fig. 5 below.)

Thus, there are two cross-linked issues: whether the picture is the long-lost original Rubens painting of 1609-10; and, who planed down the back of its panel and mounted it on a larger sheet of modern blockboard (- and with it, of course, “Why?”). The first is a matter of judgement. The second is one of fact that should also be – but conspicuously is not – one of record. Dr David Jaffé’s August 2000 bid in Apollo (see below) to explain why the panel painting “might have” received its alien backing before being bought by the National Gallery was doomed by his failure to follow such records as exist within the Gallery and extrapolate from them the precise place and time at which the transformation had occurred.

On matters of fact, at Fig. 2 below, we note an item on the National Gallery’s recently updated online Samson and Delilah entry which itself supplies visual confirmation of past institutional culpability.

Above, Fig. 1: top, Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s (republished) award-winning 1995 study of the Fayum encaustic paintings; above, Doxiadis’s new book NG 6461 The Fake National Gallery Rubens – N.B. “NG6461” is the Gallery’s inventory number for its supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah.

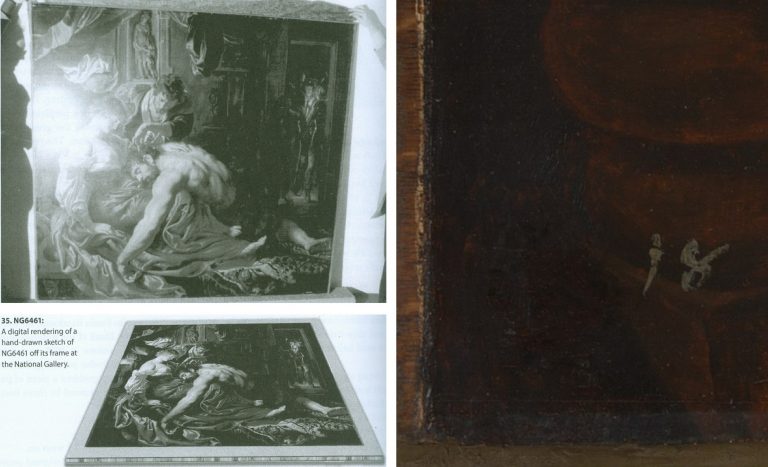

Above, Fig. 2: Top, left, The National Gallery Samson and Delilah, as seen in Antwerp in 1980 when it was about to be dispatched to Christie’s, London, and at which date the paint reached the top and bottom edges of its panel but not the side edges (to which slim battens had been attached – on which, see comment by Martin Wyld below). Above, left, Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s digital rendering of the Samson and Delilah panel on its blockboard mount, as seen by her when the picture was undergoing dendrochronological examination at the National Gallery on 25 September 1996. (Both images above are published in Doxiadis’s NG6461 The Fake National Gallery Rubens.)

Above, right, the bottom left corner of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah in which the picture’s post-1980 blockboard backing can now be seen running below the bottom of the painting. The Gallery’s online publication of this image’s visual corroboration of the panel’s post-1980 blockboard extension is intriguing. Wittingly or unwittingly it constitutes a tacit acknowledgement of institutional responsibility for the Gallery’s own (always previously denied) planing down of the panel and subsequent mounting of it on a larger blockboard sheet. (See Figs. 3 and 4 below.)

The Gallery’s online entry acknowledges – somewhat disparagingly – the existence of the Samson and Delilah picture’s “Naysayers” and cites some of their/our publications. Unfortunately, although it cites both issues of our Journal that were dedicated to the Samson and Delilah’s problems (see Fig. 7 below) it does not address their contents – as might be instanced in this pertinent item on the “Material Evidence” section in our Autumn 2000 Journal:

“…This conflict of testimony echoes one found within the Gallery in 1983 when the restorer David Bomford described the thinned panel as glued ‘onto’ the face of the blockboard while the Head of Science, Joyce Plesters, described it as ‘set into’ the blockboard. When I drew this discrepancy to [the then-Director] Neil MacGregor’s attention, he replied (letter 19th June 1997): ‘Incidentally, at the risk of being pedantic, into is the correct preposition, since the edges of the blockboard are flush with the [edge] surface of the panel. Onto would be correct if the panel had simply been glued to the blockboard and protruded above it.’ If this account is accurate, with the edges of the panel and blockboard being flush, there would be no place for the putty bevel encountered by Ms Doxiadis and Mr Norman [*1]. By the same token, had the edges of the panel and blockboard been flush, there could have been no grounds for Joyce Plesters’ 1983 [Technical Bulletin] claim that the treatment had ‘render[ed] the edges of the panel inaccessible’ for dendrochronological examination. A clear, focussed photograph of one of the picture’s corners might throw some light on the subject. Or better yet, permission to examine the panel in the flesh…”

(Emphasis added. Permission to examine the panel was never granted.)

On 14 February 2006, when examining the Samson and Delilah’s dossiers for a second time [*2], we noted photographs showing that the paintwork stopped short of the edges of the oak panel only on the vertical edges. In the present revised online Gallery entry, confirmation and possible explanation for this feature is given: “There is a narrow margin of unpainted wood at the sides of the oak panel which probably results from the support being held firm by grooved battens while the ground and then paint were applied; ‘6’ the ground and paint extend to the top and bottom edges.” The footnote ‘6’ reads: “The same can be seen on Rubens’s Judgement of Paris (NG6379). For this practice see, for example, Wadum 1998. The battens seem often to have been only along the shortest sides. A little of the unpainted margins may have been trimmed away since they are rather narrow.” With the Gallery’s Samson and Delilah, the photographic and documentary records of the restoration treatments are strikingly less complete than those of other Gallery panel paintings. For example, when writing on the restoration of the Altdorfer panel bought in 1980, Martin Wyld discusses the attachment of battens to the edges of panels: “Although some German panels of this period have channels at or near the end grain of the plank in order to accommodate battens which were fixed to the frames, the channels are seldom to be found on all four sides”.

[*1] Charles Norman, Director, The National Timber Trade Federation. As Dalya Alberge reported (The Times, 27 August 1997) on photographs supplied to us by Mr MacGregor, Mr Norman judged the back of the Samson and Delilah to be “a blockboard manufactured in the late 1970s or early 1980s”. It looked, he said, “like a manufactured item, machine-made rather than handmade”. Later, after being invited to see the picture at the National Gallery, Mr Norman amended his earlier observations. His subsequent description of the picture’s physical component parts (made by telephone, 18 & 19 September 1997 to Michael Daley) was a compromise between his original observation and Euphrosyne Doxiadis’ (above-illustrated) clear recollection of a substantial surround between the edges of the planed down panel and the blockboard support, and Mr MacGregor’s claim of flush panel and blockboard edges. That is, Mr Norman claimed that the blockboard was somewhat larger than the planed down panel but that the gap between the two had been filled by a wide putty bevel.

[*2] In 2006, under Charles Saumarez Smith’s directorship, we were given full access to the Collection’s photographic and documentary records – a privilege subsequently extended by Nicholas Penny and Gabriele Finaldi. (ArtWatch is greatly indebted to all three knights – as also to the Gallery’s kindly helpful archival and library staffs.)

With the Gallery’s present publication of the Fig. 2 photograph of the bottom left corner of the Samson and Delilah, two points should be noted. First, the Gallery’s 1997 claimed relationship between the panel and its blockboard backing was clearly unfounded. Second, the photograph of the bottom left corner is cropped and therefore does not show the full blockboard extension. Nonetheless, it does now show (MacGregor’s earlier claims notwithstanding) that, far from the edges of the panel and blockboard being flush, the latter can be seen to protrude beyond the bottom edge of the picture when, as seen above at Fig. 2, top left, it had not done so in 1980 when held by the banker, Jan Bosselaers, in Antwerp, shortly before it was sent to Christie’s. Today’s publication of that photographically-confirmed relationship has finally demonstrated that the blockboard backing must have been applied to the picture’s panel after 1980 and when in London.

CONFLICTED AND OPAQUE GALLERY ACCOUNTS – AND THE FIRST PUBLISHED APPEARANCE OF THE BLOCKBOARD BACKING

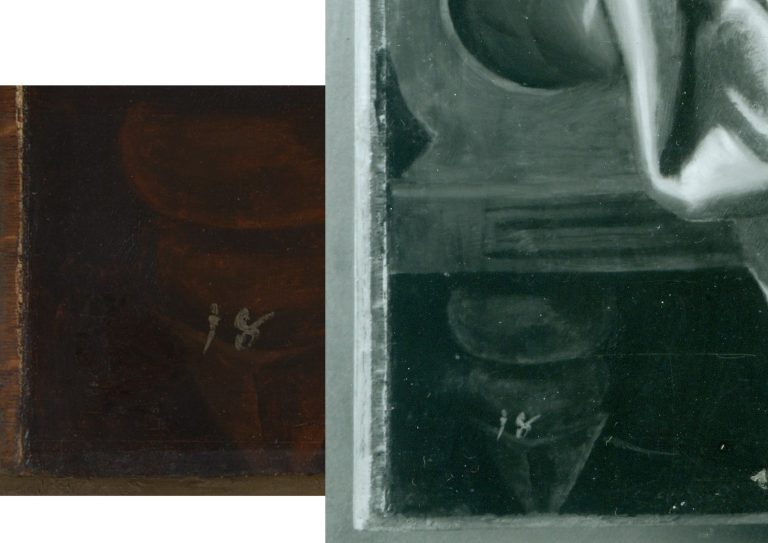

Above, Fig. 3: left, the National Gallery’s recently published online detail of the bottom left corner of the Samson and Delilah; right, a detail of the bottom left corner the Samson and Delilah in a National Gallery photograph taken on 10 August 1982 and designated: “After Cleaning, Before Restoration”.

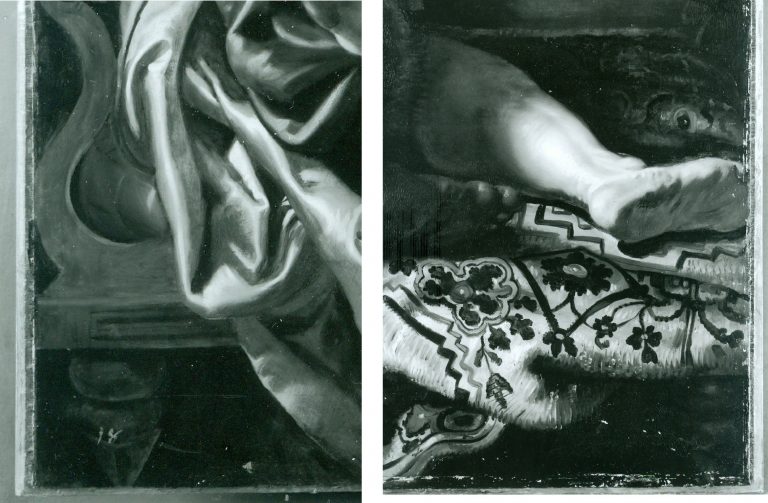

Above, right, this – so far as we know – unpublished 10 August 1982 photograph, shows the then-present blockboard backing that protrudes not only beyond the bottom edge of the panel but also beyond its left vertical edge (which is not disclosed by the cropped image presently shown online). The date on the black and white photograph shows that the picture had then been in the Gallery’s possession for twenty-five months by which time the planing and mounting on blockboard had occurred (as had also the removal of the picture’s varnish, as shown below.) What the Gallery has never produced – and, we believe, could not ever produce – is a photograph showing the blockboard’s presence before the picture was acquired from Christie’s or when it had been loaned by Christie’s to the National Gallery ahead of the sale. In the absence of such important photographic testimony, the conclusion that the National Gallery itself planed down the panel for undisclosed reasons and mounted it onto a blockboard sheet, is inescapable. The formal authorisation for the picture’s restoration from the Board of Trustees came on May 16 1982 just three months before the above-right photograph was taken. Thus, on the available official records, the removal of the Samson and Delilah panel’s back and the subsequent mounting of it on blockboard had occurred at the National Gallery between 16 May and 10 August 1982. (It is not inconceivable, however, that the formal application for permission to restore the picture had in fact followed a commencement of work on it.)

Above, Fig. 4: The Samson and Delilah’s bottom left and bottom right corners, as respectively recorded at the Gallery on the 10th and 11th of August 1982, by which dates the visible blockboard extensions (which read as the whitish strips) all around the panel had materialised within the Gallery’s own photographic records for the first time – and indicated the extent to which the new blockboard backing extended beyond the planed-down remains of the original oak panel. Earlier, the National Gallery Board Minutes of 16 May 1982 had carried the following note:

“The treatment of No 6461, proposed for Mr Bomford, was recommended by Mr Brown, who explained that the painting was to be the subject of the second ‘Acquisition in Focus’ exhibition, opening in January 1983.” It added, matter-of-factly:

“The painting had a modern support of wood attached to the original panel which had been considerably reduced in thickness and this was considered adequately stable; the surface had probably been only partly cleaned in the recent past, and tests showed considerable discolouration.”

This above account made to the Board was the first-ever mention of a blockboard backing on the painting. It had not been so described by Christie’s and, as shown below, it was even at variance with an in-house National Gallery timber expert’s 1982 account of the painting when it was on exhibition in the Gallery and ahead of its restoration. Strictly speaking, the above statement was technically accurate: the picture had, by that date, been planed down and mounted on blockboard – but only very recently so. Even though the the Gallery had had sight of the picture since the beginning of July 1980 (and had taken photographs and Infra-Red images of it on July 2 1980 – ahead of the sale) it had not – as Mr MacGregor confirmed to us – made any photographic record of the picture’s back either after buying it, or earlier when it had been loaned ahead of the July 11 1980 Christie’s sale. This lacuna is, on our familiarity with the Gallery’s technical literature and dossier records, unprecedented. Indeed the Gallery’s restorers sometimes give the impression that they are more interested in working on pictures’ physical “supports” than on their painted surfaces – and by “working on”, we mean undoing and redoing them. (See Fig. 9 below.)

A TIMBER EXPERT’S ACCOUNT OF THE SAMSON AND DELILAH PANEL

In the 1982 National Gallery Technical Bulletin, Christopher Brown, Martin Wyld and the Gallery’s (now deceased) timber expert, Anthony Reeve (who was held by Mr MacGregor to have been the “supreme practitioner of his generation”) wrote on the cleaning and restoration of Rubens’ The Watering Place and, in doing so, made clear that no blockboard backing had been applied to the Samson and Delilah at that date. That is to say, when discussing the highly problematic construction of many Rubens’ panels, Reeve noted:

“Of all the pictures in the National Gallery, Rubens’ panels have been of greater concern, because of their condition, than any other part of the collection. The reason for this is well-known. Rubens frequently found it necessary to enlarge his pictures after he had started painting… Rubens’ oak panels, often enlarged in several different stages, are amongst the most inherently unstable supports used by any artist.”

However, in so saying, Reeve drew a distinction between “the oak supports which, although made up of many planks joined together, were not enlarged during the painting process, and those which were added to.” Of that former, relatively unproblematic type, Reeve cited just three examples:

“The Rape of the Sabine Women… The Judgement of Paris… Samson and Delilah… the panels of which are made up of six, five and seven oak planks respectively. The grain of every plank, and hence the joins, are horizontal and all the planks are roughly the same width.”

In consequence, Reeve continued, although “these large panels are sensitive to changes in relative humidity (RH), they provide a sound and permanent support if kept in a controlled environment and not exposed to sudden changes in RH.” Whatever reason subsequently led to the National Gallery’s decision to plane down the panel and mount it on blockboard, it was not one of conservation necessity. Curiously, as late as 1996 Christopher Brown was still extolling the the sound construction of the Samson and Delilah’s Panel: “In contrast to a panel like the Samson and Delilah, carefully made from a small number of planks in all of which the grain runs parallel, many of the panels on which Rubens’s landscapes are painted are extremely fragile and prone to splitting”.

Thus, two years after the Gallery had bought the Samson and Delilah for a then huge sum, the Gallery itself (- and, note, just months ahead of Christopher Brown’s 16 May 1982 Board Minute-ed claim of a supposedly long-present blockboard backing) had yet to begin describing the picture as being on a radically reduced panel glued onto a larger blockboard support.

On Reeve’s (nowhere contested) 1982 Technical Bulletin testimony, although the three pictures had been well and favourably constructed, all were at risk of potential injury through their exposed bare panel backs in the event of dramatic atmospheric fluctuations. Had the Samson and Delilah already been planed down to a thickness of just 3 millimetres and mounted on a larger sheet of blockboard, there would have been no such risk or concern – and a timber craftsman as expert as Reeve could not/would not have confounded all three pictures as equally soundly-made and still intact panels which retained their original backs and such information as they bore. This conflict of testimonies within the Gallery coincides with a marked lapse in the Gallery’s own – and frequently self-proclaimed – “customary” record-keeping. That is, no documentary or photographic evidence has ever been produced to support the Gallery’s post-1983 Technical Bulletin Bomford and Plesters’ claims that the Samson and Delilah had been bought on 11 July 1980 as a greatly reduced panel mounted on a blockboard backing sheet even though, as mentioned, other photographs of the picture had been taken when it was loaned to the Gallery ahead of the sale.

Had Brown been right and Reeve wrong on the picture’s then-condition, evidence for the former would normally have been found in the customary condition reports the Gallery makes on receipt of loaned works. Because (as shown below) the Gallery has not been able to produce any written and dated reports on this picture’s condition when loaned ahead of the sale, the most-recent condition report remains that prepared in 1980 by Frans Baudouin when the picture was still – as he had testified (see below) – a cradled panel of between 2.5 and 4 centimetres thickness. Curiously, when Brown later discussed the Samson and Delilah in his 1997 Rubens Landscapes exhibition catalogue, he described it as if it comprised two separate entities. First, in step with Reeve’s 1982 Technical Bulletin account, he held it to be: “A particularly fine panel…composed of six [sic] horizontal oak planks, carefully planed and jointed. The grain runs parallel in all six pieces, which are butt-jointed. The parallel grain ensures that when exposed to humidity the wood expands and contracts without restriction…etc.” But then he went on to hold that it “was planed down to a thickness of about three millimetres and set into [sic] a new blockboard panel before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 and so, no trace of a panelmaker’s mark can be found.”

Perhaps in so reporting these two contrary states of the picture, Brown was simply recalling the two chronologically successive states of the picture as he had encountered it within the National Gallery.

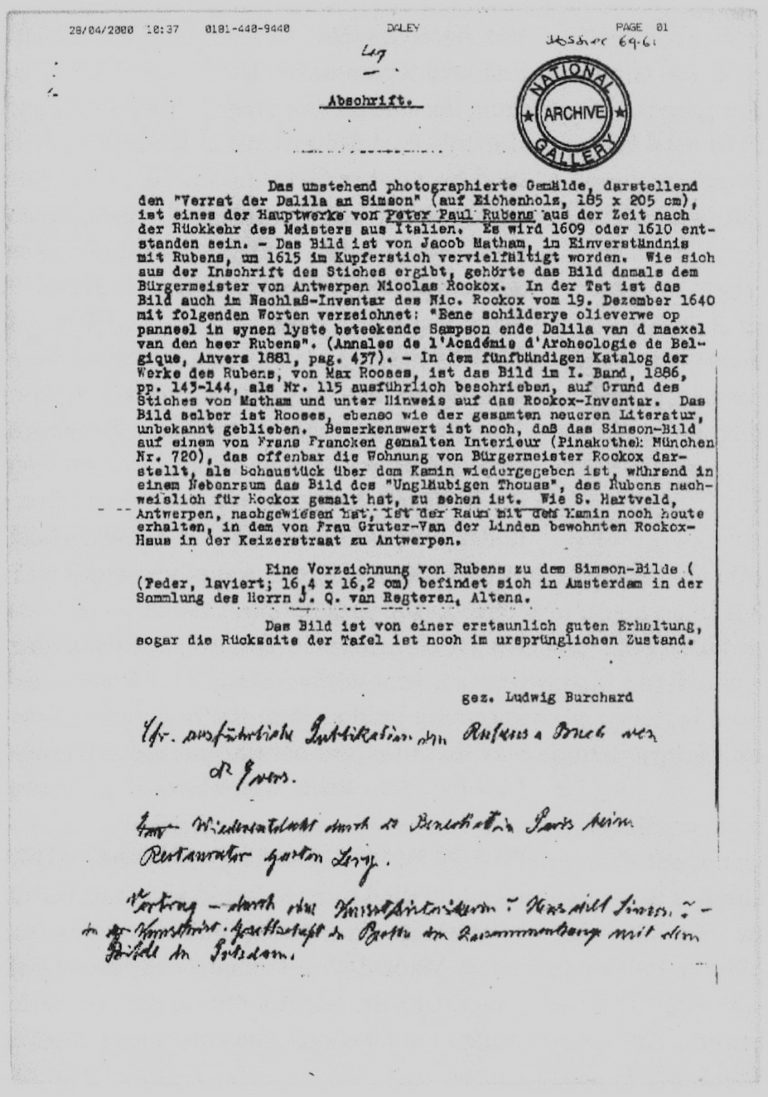

THE PIVOTAL CERTIFICATE OF AUTHENTICITY TO WHICH NOBODY REFERRED

Above, Fig. 5: A photocopy of an undated typewritten sheet in German that had comprised Ludwig Burchard’s 1930 certificate of authenticity provided to the firm Van Diemen and Benedict, and which also carries handwritten Burchard notes on the path of the picture he had authenticated. The existence of this then seventy years-old document was first published by Michael Daley in June 2000 (see note [*3])

CUSTOMARY DOGS THAT DID NOT BARK

With two such expensively acquired old master pictures it might have been expected that the accounts of both would disclose the findings of the customary Gallery technical examinations made prior to works being presented to the Trustees when seeking their authorisation to purchase. However, with the Samson and Delilah no such disclosures were offered.

In 1997 the Gallery claimed to ArtWatch UK it had not kept written records of the picture’s state in 1980 when examined at the Gallery ahead of the purchase; and, therefore, it had not presented such customary reports to its Trustees when seeking authorisation to make the purchase. Indeed, the-then Director, Neil MacGregor, specifically confessed: “The National Gallery does not have any record, photographic or written, of the back of this picture before it was planed down”. The Gallery could supply only a photograph of the picture’s back “as it is today” (see Fig. 6, below, bottom left). The consequence is that while a records trail of an intact panel runs from 1930 to 1982 – when the picture was on display the National Gallery – it is said that no official record exists of its condition on arrival at the Gallery in 1980.

However, in the picture’s own dossiers (as I discovered on 14 Feb 2006) there exist two Infra-red images of the picture (one of them being of the whole picture when still in its frame; the other, a detail showing Samson. Both images were made on the second of July 1980 – that is, nine days before the Christie’s sale at which £2.53 million changed hands. Neither image was reproduced in the 1983 Technical Bulletin even though the report on the picture carried eight images of other paintings. Nonetheless, it was precisely customary for the Gallery’s “Keeper” to prepare a report on a prospective picture’s desirability and art historical importance and for the Head of Restoration to prepare a report on the picture’s condition and soundness. That requirement was expressly noted in 1986 by the Gallery’s then deputy director, Allan Braham: “Before any purchase is made by the Gallery a report on the painting and its desirability for the collection will be made to the Director by the member of the Keeper staff with responsibility for the relevant school of painting: the condition of the painting will be investigated by the Conservation Department.”

In the 1980-81 National Gallery Report, Michael Levey thanked Christie’s for their “co-operation in allowing the Trustees to see this painting in the Gallery before the sale and thus assess not only its powerful impact but also its major contribution to our representation of the painter.” And yet, a trustee in 1980 later recalled to Euphrosyne Doxiadis that no reports had been shown to the Board on the Samson and Delilah. In a letter of May 27th 1997, Mr MacGregor confirmed to us that the painting had been inspected “in the flesh” by the Trustees before the sale but, ambiguously, he added that Christopher Brown and Martin Wyld had conducted examinations and that both remembered “quite clearly that the panel was already set into [sic] blockboard, as do the Christie’s staff most directly involved in the sale.” The person most involved at Christie’s was Gregory Martin, the former National Gallery Flemish paintings specialist. Citing the recollections of Brown and Wyld seemed further to confirm they had not produced written reports on the painting’s condition and state – indeed MacGregor said that their accounts had been delivered “orally” to the Trustees. To repeat: all National Gallery claims that the back had been planed down before the picture arrived at Christie’s are contradicted by Baudouin’s 1980 condition report as commissioned by Bosselaers – and subsequently supplied to Euphrosyne Doxiadis. It had described the picture on 4 March 1980 as a “panel, 185 x 205 cms” that was “in good shape” and in a then conservation state that could be “called excellent”.

A TALE OF TWO NATIONAL GALLERY PANELS – AND THEIR RESPECTIVE PRESENTATIONS IN THE TECHNICAL LITERATURE

In 1980 the National Gallery bought two old master panel paintings for, respectively, just below and just above £2.5 million each. Both were put on immediate display. Both generated much interest. As is customary, both were soon restored by the Gallery. They were Altdorfer’s ‘Christ taking Leave of His Mother’ and the claimed Rubens Samson and Delilah. As is also customary, both restorations were reported in the Gallery’s 1983 Technical Bulletin, but the nature and manner of their accounts diverged dramatically.

THE ALTDORFER PANEL – A PLAIN AND UNPROBLEMATIC ACCOUNT

The Altdorfer was purchased by private treaty sale from the Wernher Estates, through Christie’s, with the aid of contributions from the National Heritage Memorial Fund [NHMF], the Pilgrim Trust and the National Art‐Collections Fund (Eugene Cremetti Fund). Today the NHMF says of the Altdorfer: “The acquisition of this painting strengthened the collection of German paintings at the National Gallery, then relatively under-represented. Works by Altdorfer are exceptionally rare: this painting and the Landscape with a Footbridge (Room 4) are the only two works by the artist in this country. The painting was bought for £2.45 million by the National Gallery in 1980 from the Wernher Collection at Luton Hoo, only months after the NHMF was founded. Without the intervention of the NHMF, which gave £825,000, the National Art Collections Fund (Eugene Cremetti) and the Pilgrim Trust, the painting would have been sold at auction, and almost certainly have been exported.”

THE RUBENS PANEL – A GRAVE ATTRIBUTIONAL MISFIRE

The NHMF has subsequently given much support to the National Gallery assisting it on the purchase of eleven pictures nine of which are shown online by the Gallery; but it had not done so with that of the Samson and Delilah, where Christie’s had given no price estimate in the sale catalogue and the underbidder’s identity remains unknown to this day. We had been given to understand there had been three bidders in the sale: Sir Geoffrey Agnew, acting for the National Gallery; Dr Reinhold Baumstark of the Liechtenstein Princely Collections; and, a bidder on behalf of the Rockox House Museum, who had dropped out at £1,300,000. Christopher Brown has claimed – and his successor at the National Gallery, David Jaffé, intimated in Apollo in 2000 – that Dr Baumstark had bid for the Liechtenstein Princely Collections. However, as Euphrosyne Doxiadis has reported, the then-Prince of Liechtenstein was not the underbidder, nor had he even taken part in the bidding. (See note [*4] below.)

The Samson and Delilah was bought by Agnews on behalf of the National Gallery at a Christie’s auction for a world record Rubens price of £2.53 million. The sale took place in the morning of 11 July 1980 and the picture was hung in a reserved space at the Gallery in the afternoon. A “Strictly Confidential” Gallery press release announcing the purchase had been prepared ahead of the sale. In 1983 the National Gallery Director, Michael Levey, wrote in the “Acquisition in Focus” Samson and Delilah exhibition catalogue: “…some people might have asked why the nation needed another Rubens. In the Collection at Trafalgar Square there were already twenty paintings by the artist… Rubens’ Samson and Delilah is a large scale, early and entirely autograph painting of a kind the National Gallery previously lacked.” (As shown below, Levey’s successor, Neil MacGregor, would be obliged to explain to the public why this “Rubens” looked like no other in the Gallery.)

By that date the picture had been restored and fitted with a new replica period frame made in imitation of the frame shown in Frans Francken’s copy of the original Rubens Samson and Delilah as installed in the house of its first owner, Nicholaas Rockox when its previous frame had been thought possibly original to the painting. The restoration that had immediately preceded the Gallery’ 1983 exhibition was lauded by Levey: “Its splendid colour and vigorous handling of paint can be all the better appreciated now that it appears cleaned in this exhibition.” Along with its world-record price, the Gallery had invested much scholarly/curatorial capital in this particular acquisition – on which its successive accounts would prove so unsatisfactory.

A RISE OF NON-CURATORIAL OPPOSITION THAT DREW IMMEDIATE BLOOD

There seems little question the purchase had been made in professional good faith. Since the picture’s 1929 emergence from nowhere – or, rather, from a restorer’s studio – and its 1930 upgrading by the leading (but subsequently discredited) Rubens scholar Ludwig Burchard, no Rubens specialists had demurred from the view that a well-recorded but long-lost Rubens masterpiece had been found. By the early 1990s, however, certain artist/scholars [*3] had rejected the Rubens ascription, initially, on essentially stylistic grounds and the picture’s manifest visual incompatibility with the testimony of two securely contemporaneous copies of the original painting. Although repeatedly denied by the Gallery, it would further transpire that, during its 1981-82 restoration at the Gallery, the Samson and Delilah panel underwent a covert physical transformation that left the picture at variance with all records of its condition and composition [*4]. As seen above, in 1980, when about to be sent to London, the panel retained its original and by then cradled back. When bought by the National Gallery in 1980 , Christie’s sale catalogue entry described it as being “on panel”. When on display at Christie’s, it was seen by many to have been a cradled panel – albeit one whose “bars did not slide”, as the former-Christie’s staffer, and the then Evening Standard art critic, Brian Sewell informed us.

[*3] In February 1992 a report from three art students challenging the attribution – Euphrosyne Doxiadis (author of the acclaimed The Mysterious Fayum Portraits from Ancient Egypt – see Fig. 1 above), Steven Harvey and Siân Hopkinson – was submitted to the National Gallery and placed in the Samson and Delilah’s dossiers. The Senior Curator, Christopher Brown, would later concede that “gaps at the beginning and end of the picture’s provenance” made it impossible to be 100 per cent sure this was the original Rubens Samson and Delilah of 1609-10.

[*4] That is, when upgraded from Honthorst to Rubens by Burchard, he had specifically enthused – contrary to subsequent official National Gallery claims – that the panel painting “even retains its original back”. (See Figs. 2-5.) I discovered Burchard’s nowhere acknowledged certificate of authenticity in April 2000 in a typed manuscript copy of 8 April 1930 held in the National Gallery’s own Samson and Delilah dossiers, it having presumably been passed on to the Gallery by Christie’s after the 1980 auction. When that discovery was published in the June 2000 Art Review I sent a copy to the Gallery’s Director, Neil MacGregor. The following day, the Gallery released an unsigned statement acknowledging for the first time that, contrary to the Gallery’s (Technical Bulletin) published claims of 1983, the panel of the Samson and Delilah could not have been planed down in the 19th century or in the 1920s “because it was recorded in its original state in 1930.” Nonetheless, at the same time, the unsigned statement claimed “the recent allegation” that the planing had occurred after 1980 was “false”.

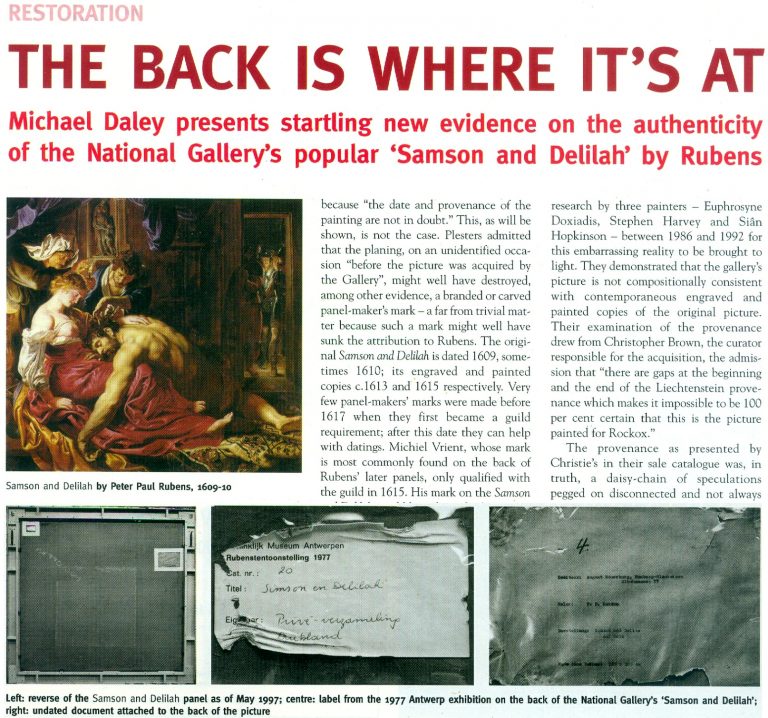

Above, Fig. 6: Extracts from the June 2000 disclosures in the Art Review.

In June 2000, in response to press coverage of the Art Review article “The back is where it’s at” (Fig. 6, above), as in the Independent on Sunday (“Tell-tale sign that £40m Rubens could be a copy”), the Times and the Guardian, the National Gallery’s director, Neil MacGregor, had a notice placed in front of the picture to explain why it looked like no other Rubens in the Gallery. That notice drew attention to a fuller statement available at the information desk in which the Gallery denied our charge of its restorers having tampered with the panel. (That document was itself an “updated” version of one prepared and displayed in 1997 in response to press coverage of challenges made by Kasia Pisarek – see Figs. 7 and 8 below).

Above, Fig. 7: The Autumn 2000 and the Spring 2006 special issues of the ArtWatch UK Journal given over to discussions of the National Gallery Samson and Delilah.

NO ANSWERS GIVEN. DEBATE REPEATEDLY SHUT DOWN. A LOOP OF SILENCE CREATED.

The National Gallery later announced Christopher Brown would publish a scholarly article in the Burlington Magazine. It never came. The magazine’s editor told us none was submitted. An article by Kasia Pisarek was submitted. It was rejected by the Burlington Magazine – and, later, by Apollo (but see [*5]). In 1998 Dr Brown left the National Gallery to direct the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. An article by his successor at the Gallery, David Jaffé, appeared in the August 2000 Apollo, but it was expressly intended to end, not launch, consideration of the evidence. Arts journalists summoned to a National Gallery press conference on the pending article were advised “it will finally silence the critics”. Our request to reply was rejected by Apollo’s editor, David Ekserdjian, a former staff member of Christie’s. He also rejected a letter from Michel Favre-Felix, a painter member of the Association Internationale pour le Respect de l’Integrite du Patrimonie Artistique – ARIPA. Christopher Brown’s departure from the National Gallery served to thwart subsequent inquiries into the Samson and Delilah’s acquisition and its subsequent unacknowledged treatment.

On 6 April 2002 (letter) we asked Neil MacGregor whether Dr Brown had been aware in 1982 of Burchard’s 1930 Certificate of Authenticity and its testimony on the then sound condition of the Samson and Delilah panel. He replied: “As I am sure you know, Christopher Brown left the National Gallery some years ago… I suggest you pursue the matter with him.” When Brown was asked by the US magazine Salon (December 2005) to comment on his past involvement in the controversy, he replied: “I am sorry but I don’t want to do this. Please address your questions to the National Gallery.” In 1983 Brown had reported: “Under the terms of Ludwig Burchard’s will, I had the privilege of consulting the manuscript notes on the Samson and Delilah. My visit to Antwerp was made possible by a grant through the Sir Martin Davies Travel Fund”. Had Burchard’s own notes held by the Rubenianum not contained a draft or other record of his 1930 certificate of authenticity, as is held in the National Gallery?

THE VALUE OF REPORTS

When, after we had published Burchard’s certificate of authenticity and Neil MacGregor had adjusted the Gallery’s position accordingly, Christopher Brown and his successor, David Jaffé, held that the Samson and Delilah had been planed down when in the collection of the German magnate, August Neuerberg, between 1930 and 1980. In doing so, they went against the testimony not only of Baudouin’s March 1980 condition report but also of a leading Rubens scholar and National Gallery benefactor who had gifted a Poussin – Christopher Norris. As first mentioned in our June 2000 Art Review, article, Norris had testified in a 1980 letter (held in the picture’s dossiers) to the director, Michael Levey, congratulating him on the Samson and Delilah’s acquisition, and adding that between 1930 and 1980, no change in the picture’s “amazing condition” had occurred, other than a toning down in its 1929 varnish, because “the owners had not touched it.”

Thus – and in addition to Baudouin’s 1980 condition report – we now know on Burchard’s and Norris’s joint written testimonies (both of which are held by – but neither of which had been disclosed by – the National Gallery) that the panel was intact, in good condition and had retained its original back from 1930 until 1980 when it was sent to Christie’s. Therefore, the only parties who might have planed-off the back are Christie’s and the National Gallery itself. Christie’s, who described and sold the picture as a panel and not as a reduced panel laid on board, or as a marouflaged panel, would hardly have so-profoundly and radically transformed someone else’s property (and someone, that is, who as the work’s sole known owner, had left the picture untouched for half a century) – or, for that matter, have had the time and the great technical means to do so. But even if Christie’s had done so, the National Gallery would then, in turn, have duly recorded that recently-altered state of the picture in its customary reports on works loaned to it ahead of sales. It had not done so (see below).

Ignoring the triangulated testimonies of Burchard, Baudouin and Norris, David Jaffé’s second tack had been a more personal charge: “Mr Daley does not seem be aware of the art historical convention whereby a painting on panel, even when thinned, is still called a panel”. He cited the following instance: on December 17th 1998, Sotheby’s auctioned Rubens’ Deluge as an “oil on oak panel” when in fact it was “on a marouflaged panel”.

But how had that been that known? It was so, Jaffé disclosed, “according to a condition report” made at the Gallery by its timber specialist/restorer, Anthony Reeve (which report is held in the Gallery’s exhibition file) when the picture was loaned to the National Gallery ahead of the sale. Why then, is no such report held and cited on the Samson and Delilah when it too had been loaned to the Gallery ahead of its 11 July 1980 sale at Christie’s?

HOW RELIABLE ARE LUDWIG BURCHARD’S ATTRIBUTIONS?

[*5] In an article published in the Spring 2006 Artwatch UK Journal (Fig. 7, above right), Kasia Pisarek (Katarzyna Krzyżagórska-Pisarek) wrote:

“While investigating Dr Ludwig Burchard’s ‘rediscovery’ [of the Samson and Delilah], I was surprised at some of the truly improbable attributions made in the past by him and other well-known experts such as G. Gluck, W. R. Valentiner, W. von Bode, A. Bredius or C. Hofstede de Groot, who all guaranteed their ‘discoveries’ with certificates of authenticity…” On Burchard, specifically, “I traced many of his attributions – he was not infallible in his judgement and changed his mind. Surprisingly, over sixty pictures attributed by Burchard were later downgraded (in Corpus Rubenianum) to studio works, copies or imitations…”

To date, Dr Pisarek has identified seventy-five fallen Burchard Rubens’ attributions. (The title of Pisarek’s 2009 Warsaw University dissertation was “Rubens and Connoisseurship: On the Problems of Attribution and Rediscovery in British and American Collections.”)

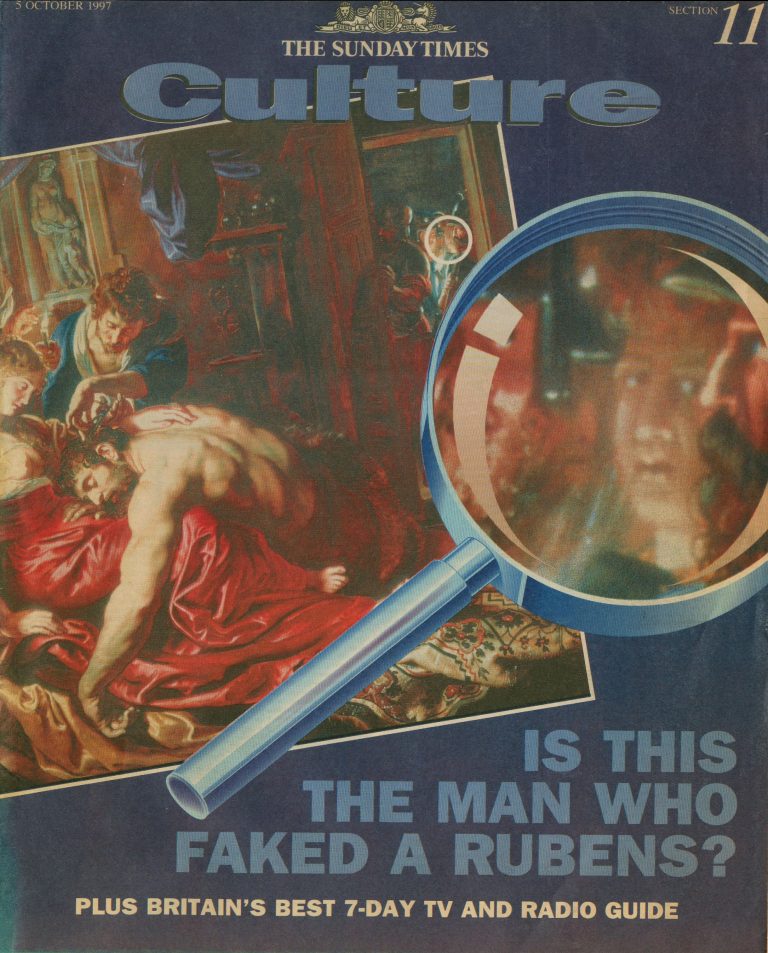

Above, Fig. 8: The Sunday Times’ 5 October 1997 coverage of Kasia Pisarek’s rejection of the Samson and Delilah’s Rubens ascription.

Certain suspicions seem to have arisen in Waldemar Januszczak’s mind as he (at that date) rejected the Samson and Delilah’s Rubens attribution in the above Culture Magazine feature and pressed the striking Whodunnit Mystery of the Disappeared Back:

“…I put this to the gallery’s chief conservator, Martin Wyld, who quips cheerfully that he was rather proud of having been accused; planing a 17th-century oak panel to wafer thinness and attaching it perfectly to blockboard while leaving its surface in pristine condition, is an exceptional feat of restoration. Nobody would or should do it today. Whoever did it earlier did a masterful job. Why did they do it at all? If a painting is in exceptionally good condition, why was there any need to hazard the transfer to block-board? A question neither the chief conservator nor MacGregor can answer. All I got from them both is the National Gallery version of: it wasn’t us, guv.”

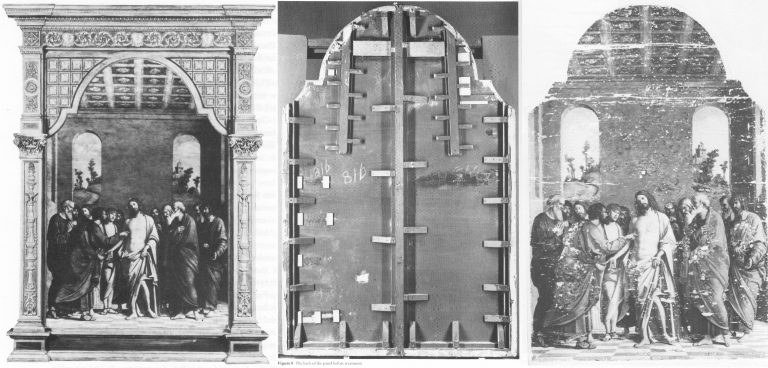

Had Januszczak been a student of the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletins he might have recalled that accounts were given in the 1985 and 1986 issues of how Martin Wyld had chiselled away the entire wood panel of seven giant planks just under two metres long of Cima’s The Incredulity of St Thomas and that, in the first stage of this supposedly now verboten practice, the panel was reduced “from c. 5 cm to 1 cm” and in the second stage, the remaining 1 cm of wood was chiselled away entirely until the back of the original gesso coatings was exposed and ready to be attached for ever to its entirely new synthetic materials sandwich.

For a glimpse into the National Gallery’s subterranean Factory for Restoration and Attribution Rehabilitations, see:The National Gallery’s Made Just like Rubens Samson and Delilah with Cropped Toes

Above, Fig. 9: The National Gallery’s Cima da Conegliano altarpiece, The Incredulity of S. Thomas. Left, the altarpiece before restoration; Centre, the back of the panel, before its entire removal and replacement; Right, as seen after cleaning and before retouching – and after the transfer of the surviving gesso and paint film onto a multi-layered synthetic support.

RECORDS v RECOLLECTIONS AND BOY-GANGS IN ACTION

If the documentary record is to be trusted, it can be said with certainty that someone within the National Gallery covertly planed the Samson and Delilah panel. Notwithstanding his later Jaffé-flaunted recollection of August 2000, Frans Baudouin [*6] had, in his 1980 condition report prepared for the Samson and Delilah’s owner, Mrs Margaret Köser, solemnly testified on his (likely financially remunerated) professional oath (as the picture was about to be dispatched by the banker Jan Bosselaers from Antwerp to Christie’s in London), that it was a panel between 2.5 cms and 4 cms thick – and, therefore, had not-yet been planed down to a thickness of under 3 millimetres and cemented onto a sheet of modern blockboard. And yet, in the face of all such precisely documented facts between 1930 and 1980, David Bomford would, in his 1983 National Gallery Technical Bulletin account, backdate the planing to an unspecified time, place, and person – viz: “At some time, probably during the present century…” – and, when so-saying, would offer not one jot of supporting technical, photographic or documentary evidence in an institution that had long claimed exemplary record keeping practices.

[*6] Frans Baudouin was described in Codart on his death in 2005 as: “the doyen of Flemish art historians. He was the former director of the Rubenshuis and the driving force behind the founding of the Rubenianum, as well as an outstanding specialist in Rubens.” Nonetheless, he had declined to discuss the Samson and Delilah’s attribution with Euphrosyne Doxiadis (the first critic of the picture’s ascription and a co-author of the 1992 Report submitted to the National Gallery) whom he had met socially. In his August 2000 Apollo article, Dr. Jaffé, belatedly acknowledging Burchard’s certificate of authenticity record of the original panel, wrote: “Three Rubens experts – Dr. Frans Baudouin, Dr. Reinhold Baumstark and Dr. Hubert von Sonnenburg – who had been contacted by potential purchasers and therefore studied the painting with particular attention, all recall seeing it in its present condition just prior to its sale at auction on 11 July 1980.”

Powerful and triangulated testimony, it might well have been thought. However, one might also assume, for example, that Baudouin’s professional documents were likely more trustworthy than his twenty years-old recollections. In support of the former, the photograph (above, Fig. 2) of the Samson and Delilah when out of frame in 1980, and as supplied to Euphrosyne Doxiadis by Jan Bosselaers, along with Baudouin’s own 1980 certificate of condition for the Samson and Delilah might be cited. Further, as mentioned, in 2001 Doxiadis asked Baumstark’s successor at the Liechtenstein Princely Collections, Dr Uwe Wieszorek, if the then-Prince of Liechtenstein had been the underbidder at the 1980 Christie’s sale. In NG6461 she now reports: “He assured me categorically in two letters that as far as the Collections were aware, the Prince was not the underbidder, nor had he even taken part in the bidding.”

As for Dr. Hubert von Sonnenburg [*7], the then Head of Conservation for the Metropolitan Museum, might he be taken as the unsuccessful underbidder? When advising that museum on the possible purchase of the then-sublimely preserved Velázquez Juan de Pareja (which was bought for the Met. from Christie’s in 1971), Sonnenburg had strenuously advised the picture should under no circumstances be bought if its canvas had been relined. Would he likely have advised that great museum to buy a reduced panel laid on blockboard at a nowhere-recorded location and time? If he had, had the Met. attempted to buy the Samson and Delilah but been outbid for once by the National Gallery? Jaffé does not say – but where Christopher Brown had told Euphrosyne Doxiadis that the Prince of Lichtenstein had been the underbidder, for their part Christie’s had refused at the time of the sale to identify the (to this day, mysterious) underbidder, whose bids were said to have been relayed to the main sale room by telephone from an anteroom.

[*7] As we noted in a March 2011 post – Hubert von Sonnenburg was certainly an adept of art museum secrecy:

When, in 1971, the Met. snatched Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja from the British (who had owned it for centuries) Thomas Hoving, Ted Rousseau, von Sonnenburg and Everett Fahy had all flown to London, Madrid, and Rome – a sort of “boy-gang”, as they saw it, playing at spreading rumours like “the disinformation section of the KGB” – as Hoving (who later claimed to have discussed with Wildenstein’s how to “manipulate the art press and crank up the rumor mill” in a general strategy of “dissimulation and misleading rumors”) put it in his memoir. Even when successfully bought, the Velázquez was not paraded at the Met. but, rather, was “sneaked” into Wildenstein and Company “for secrecy”, partly because funds had been committed without the Board’s knowledge and also because, as Hoving put it, the Board had to remain longer in the dark as further “total secrecy” would be needed to “prepare our public relations stance” and to “have the time to clean it.” The deception of the public was to be absolute: for a short period before the restoration, the picture was exhibited to New Yorkers as if it were Wildenstein’s own property. Subsequently, the Met audiences only got to see the von Sonenburg-redone Juan de Pareja and not the miraculously well-preserved jewel that had, some time before, been taken to the New World by a triumphalist, dissimulating art world boy-gang.

In Part II – A TALE OF TWO ASCRIPTIONS AND THEIR RESPECTIVE TECHNICAL EXAMINATIONS – we examine the remarkable methodological discrepancies evident in the National Gallery’s own respective 1983 accounts of its two expensively bought 1980 panel paintings, and show why the Samson and Delilah should never have been presented from 1930 onwards as the long lost Rubens of 1609-10.

POSTSCRIPT: See Dalya Alberge’s disclosures in today’s Guardian:

A £2.5m dud? Fresh doubt cast on authenticity of National Gallery Rubens

15 June 2025

Connoisseurship: Examinations, Debates and Snap Visual Responses

The rising tide of old master “sleepers” and “discoveries” carries great dangers and demands snap judgements. Some candidates for upgrades intrigue, some look dubious, some scream “Fake!” Last week two cases caught our eye.

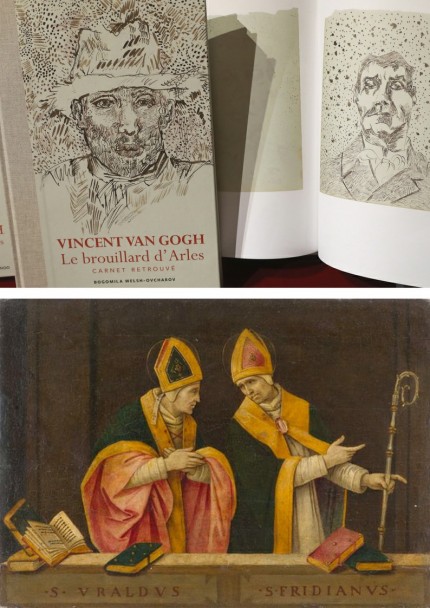

Fig. 1, above. Fig. 2, below. The newly discovered “Lost” Van Gogh sketchbook (above, top) rang our and many other fake bells. Then came a report that a small “Florentine School” painting on a €3-4k estimate fetched €375k at auction as a sleeping Filippino Lippi (above, Fig. 1). A link to another small work attributed to the artist at the North Carolina Museum of Art (Fig. 2, below) showed pronounced, seemingly reassuring correspondences, but something jarred.

On connoisseurship we hold that every claimant work should be rigorously “interrogated” in three crucial respects. Technically, in its physical composition; by documentation on its known or claimed histories (provenance); and, above all, by visual analysis because, in the visual arts, every picture is its own prime historical document and its inbuilt historically-generated artistic relationships constitute the primary subject of art critical appraisal and evaluation.

Failure to excise bad attributions deceives the public and corrupts oeuvres. A good picture has nothing to fear from challenges. No amount of scrutiny constitutes a threat as good pictures outlive their doubters and can fight another day. Argument is healthy and a successfully repulsed challenge can increase understanding and enhance a good picture’s lustre.

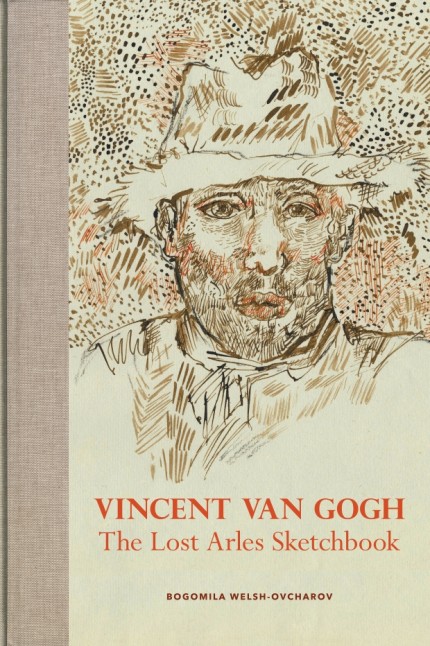

Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook

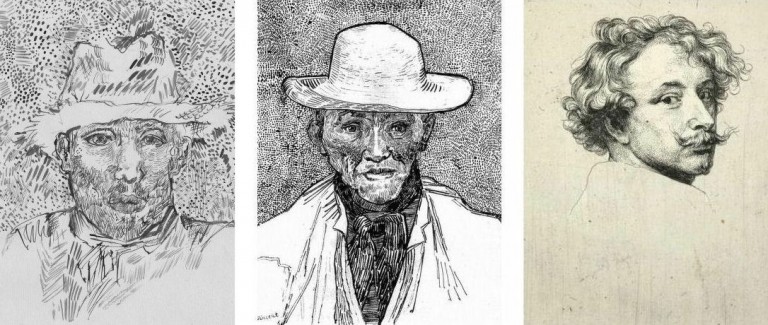

Above, Fig. 3. The controversial lost-but-now-found Van Gogh sketch book above is by Professor Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, a Van Gogh authority whose claims of authenticity are supported by Ronald Pickvance, author of Van Gogh in Arles, but the cover’s supposed Van Gogh ink self-portrait announces itself as a draughtsman’s pastiche, as Mark Hudson noted in the Daily Telegraph (“A romantic story but can it really live up to its promise?”, 16 November 2016).

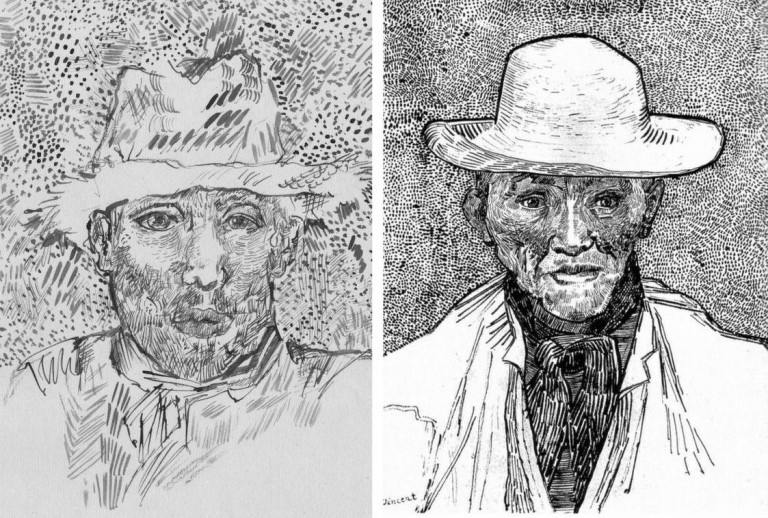

Above, Fig. 4. Simply by placing the supposed Van Gogh self-portrait next to an autograph portrait, immense and glaring differences become apparent: the author of the “discovered” drawing has abandoned symmetry with eyes of radically different sizes and a nose that seems product of a car crash. Throughout, the author mimics Van Gogh’s pen marks without comprehension of his form, power of design, and psychological acuity.

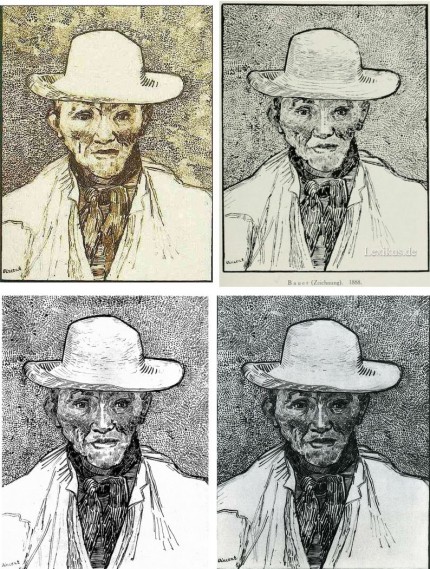

Above, Fig. 5. Instead of a form-camouflaging jumble of marks, the bona fide Van Gogh disports five graphically discrete component parts: a light-coloured jacket; a dark shirt and scarf; a varied but, on aggregate, mid-toned face; a light-toned hat with some mid and dark-toned form articulating shading; and, throwing all other values into relief, an agitated but tonally cohering background. Each of these spheres is allotted its own graphically purposive notations. The four images we show above for comparison are easily found online in historically successive reproductions. While these reproductions vary considerably, the force and artistic coherence of Van Gogh’s graphic intent and method shines through all.

Above, Fig. 6. If we place the bona fide Van Gogh between the clumsy mimicking newcomer and a masterpiece of the greatest graphic brilliance – van Dyck’s etched self-portrait – it is clear that the Van Gogh has more kinship with the latter than with the former.

Above, Fig. 7. And if we compare the Van Gogh with an entirely autograph van Dyck etched state of a figure we find a common use of a toned background that throws both subjects’ flickeringly brilliant lights and darks into relief.

The Van Gogh Museum’s objections to the “Lost Arles Sketchbook” and its track record on Van Gogh attributions

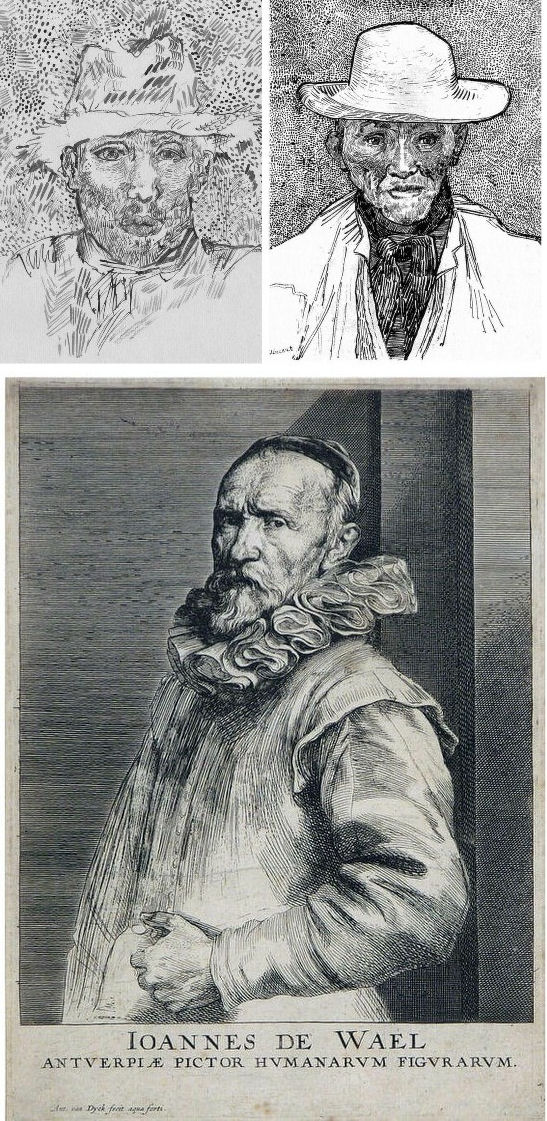

Above, Fig. 8. Prof. Welsh-Ovcharov (top) has responded to the Van Gogh Museum’s dismissal of the drawings with a rebuttal and a challenge to debate – thereby showing conviction and good faith. Her publisher reportedly characterises the proposed debate as “an opportunity to shed light on the conditions under which the Van Gogh Museum is claiming the de facto right to a monopoly of attribution.” This is a common plaint against authorities that block would-be, high-value attributions but our impression of the museum’s judgements is favourable.

In 2006 a Van Gogh – The “Head of a Man” owned by the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia (above left, on an easel) – was challenged by the art historian and Sunday Times art critic Frank Whitford when the portrait was loaned to an exhibition in Edinburgh. The newspaper asked our opinion and, when we demurred, sent a (revelatory) high resolution full colour compilation of all of Van Gogh’s painted portraits. We supported Whitford, saying to the newspaper (as reported in ArtWatch UK Journal, Spring 2008):

“The specific warning signs that should have alerted the buyer are:

“1] It is unique in Van Gogh’s portrait oeuvre

“2] It does not fit in the stylistic chronology that exists within that oeuvre. Compare it for example with the brushwork, colours and ‘attack’ of the Old Man with Beard, painted the year before that is in the Van Gogh Museum, and the Portrait of Camille Roulin painted a year or so later and that is also in the museum. There is an enormous but clear and logical development between those two pictures, from thick, laboured, relatively coarse brushwork to much more refined and ‘decorative’ marks – but both are entirely consistent and ‘all-over’ in their treatment.

“3] If its provenance goes back no further than Germany in the late 20s or early 30s, that is particularly unfortunate. Germany at the time was notorious for the certification by scholars (for a fee or sales cut) of dud works. The dealer René Gimpel has referred to the scandalous ‘amounts obtained by means of certificates given daily by German experts to German dealers. Just as there were paper marks, so there are paper canvases, an easy way of bringing dollars into Germany…The German title of Doktor impresses the Americans. The museums are even more intent than the collectors on defending their fakes or their mistaken attributions….’ By coincidence, in the current ArtWatch Journal [No 21], Kasia Pisarek cites the case of the great Rubens scholar Ludwig Burchard who issued so many optimistic certificates that he was unable ever to write his definitive book on the artist…She has identified over 60 Burchard attributions that have subsequently fallen. It was Burchard who first upgraded to Rubens the Samson and Delilah that is now in the National Gallery.

“I would add that the fact that it seems to be admitted that it is a cut-down canvas that was glued onto a panel compounds suspicions… Why should a (presumably) then only forty years old canvas, have needed gluing onto a secondary support? It might be worth asking the Gallery curators if any scholar has questioned the picture publicly or privately.

“It may be coincidence, but two of the pictures that ArtWatch has challenged in our own National Gallery, the Rubens Samson and Delilah and the Raphael Madonna of the Pinks, no longer retain their original backs. The former was planed down to 2 or 3mm thickness and glued onto a sheet of blockboard; with the latter, the family of restorers who sold the picture in the 19th century had (most unusually) polished the back of the panel thereby removing all historical evidence.”

As we have seen more recently, the claimed lost Leonardo drawing “La Bella Principessa” that emerged anonymously in 1998 had been glued to an old oak panel. Gluing canvases or drawings onto boards conceals half the material evidence. On 3 August 2007 Andrew Bolt reported in the Australian Herald Sun:

“The curious thing about the National Gallery of Victoria’s fake van Gogh is how easily it was spotted as phoney once it went on tour…. For more than 60 years this painting hung in the NGV without anyone screaming ‘Fake!’ True, a few experts now say they had their doubts, but it was only when the NGV proudly loaned its ‘van Gogh’ to Scotland’s Dean Gallery last year that the painting was denounced. Three British critics took one look at it and snorted… Even then, there were some back in Melbourne who couldn’t accept the evidence of their own eyes, as ABC Television’s 7.30 Report found:

“‘Two of the critics include Michael Daley from ArtWatch UK and Times art critic Frank Whitford. But Robyn Sloggett [an art authentication expert at Melbourne University] has questioned their expertise. ROBYN SLOGGETT: I don’t think either of them are Van Gogh experts, certainly not known to be such…[Director of the National Gallery of Victoria] DR GERARD VAUGHAN: It is a slightly offbeat picture. It doesn’t fit into the natural progression of Van Gogh’s work at that time because it was a moment in late ’86 and into early 1887 where he was experimenting with two or three different styles. In many ways, this is slipping back into his earlier realist style of the mid 1880s where he concentrates and uses these earthier ochre colours. It is a transitional picture.’”

“Conceived at special moments” and “sometimes repeating, sometimes anticipating themselves” are commonplace apologias for disqualifying incongruities in upgrades. In 1997 and 2000 the National Gallery claimed its Rubens Samson and Delilah did not look like any other Rubens in the gallery because it was “the only work in this collection typical of the artist when he had returned from Italy in 1608”. In truth the painting was unlike the (secure) one that immediately preceded it and unlike the (secure) one that immediately followed. If a Rubens, it would be the only one on which he employed flat brushes and painted finger tips with rectangular highlights. During ABC Television’s 7 August 2006 programme (“NGV’s Van Gogh Labelled a fake”), James Mollison, a former NGV director said: “This picture has been doubted by people very often.”

The upshot of the controversy was that the NGV director announced that such was the gallery’s confidence that the painting would be submitted (voluntarily) to full technical examination at the Van Gogh Museum. A year later the Herald Sun reported the attribution’s demise at the Van Gogh Museum:

“The Dutch team used X-radiograph, digital photographs, light microscopy and paint and thread analysis. Among conclusions were: THE work’s ground layer of white paint is not found in Van Gogh’s Antwerp and Paris works. ITS use of pure ochre is not found in other Van Gogh work. THE portrait shows just the top of the man’s shoulders. Van Gogh usually showed more of the clothes. “A COMBINATION of a fairly coarse and detailed painting style”, with more detail in the mouth, eyes, skin and beard than Van Gogh used. NO reference to the portrait or the sitter in Van Gogh’s extensive letters. The experts also noted no record of the work could be found before 1928, when it appeared at Berlin’s Galerie Goldschmidt and Co.”

The Rubens Samson and Delilah emerged in Germany the following year at Van Diemen and Benedict where it was offered as a Honthorst before being upgraded by Ludwig Burchard. Previously it had been attributed to Jan van den Hoecke, a follower of Rubens. Burchard had recently upgraded the supposed Rubens ink sketch design for the Samson and Delilah (see Art’s Toxic Assets and a Crisis of Connoisseurship ~ Part II: Paper – sometimes photographic – Fakes and the Demise of the Educated Eye ).

The Newly Upgraded Filippino Lippi

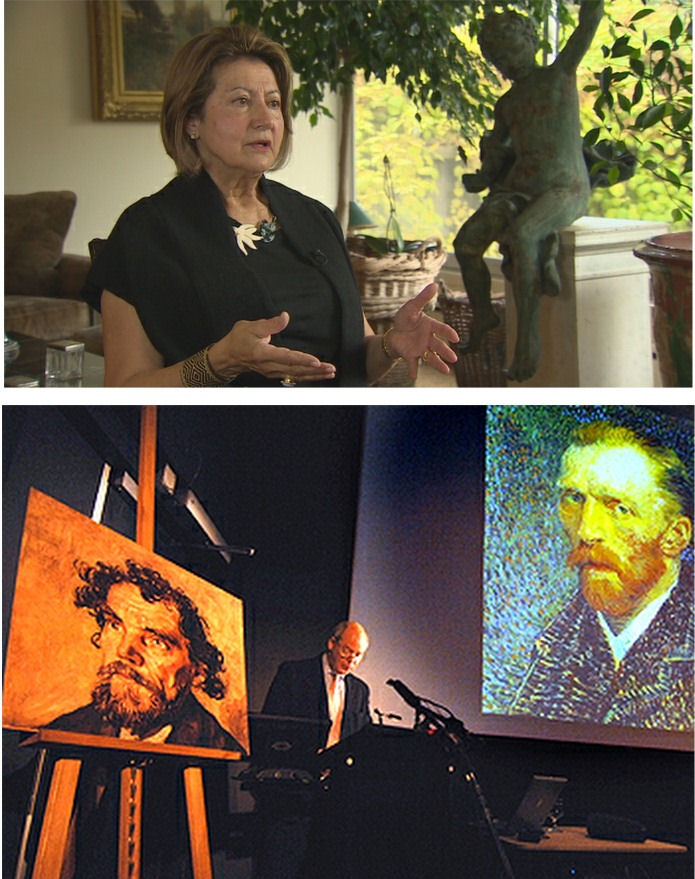

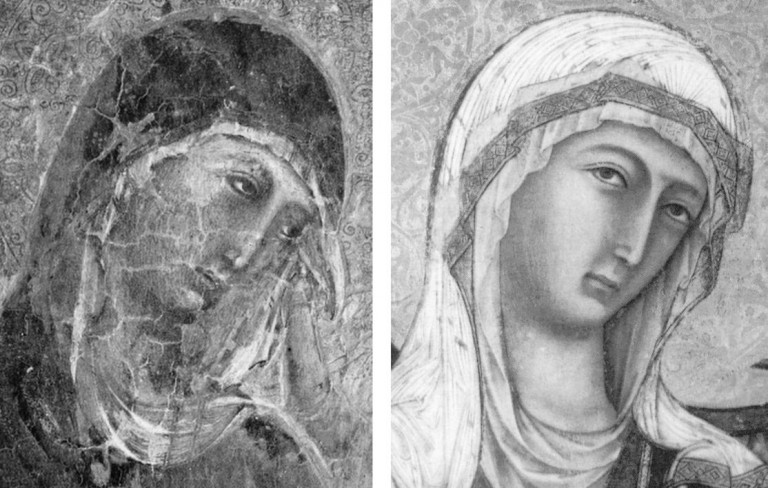

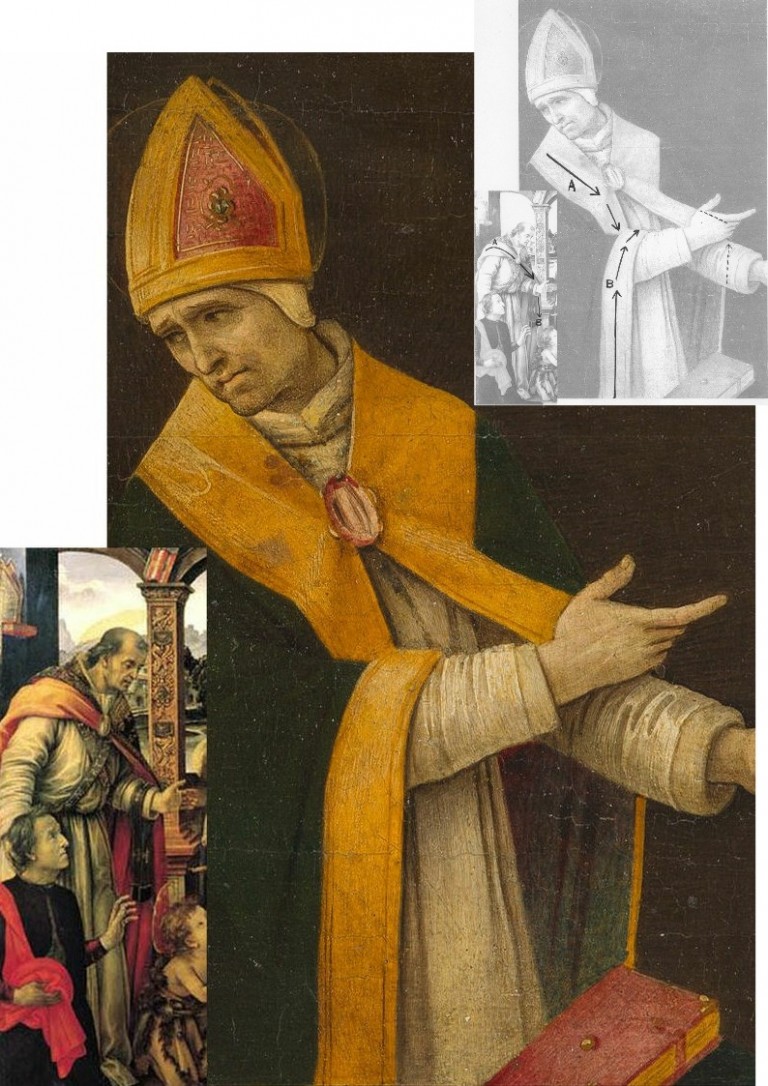

Above, Fig. 9. At first glance the awakened “Filippino Lippi” (above right) seems more plausible than the new Van Gogh drawings – especially when linked to a work attributed to the painter at the North Carolina Museum of Art (above left). In terms of palette, condition and design the two seem as peas in a pod but this closely related pair triggers no recollections of anything similar in the artist’s oeuvre. If their strikingly common format suggests original incorporation in a larger work, disjunctive variations in their parapet walls and stone inscription tablets dispels the possibility. Most inexplicably of all, the new upgrade is incongruously modernist in its emphatic planar and ‘on-the-picture-surface’ geometrical vocabulary.

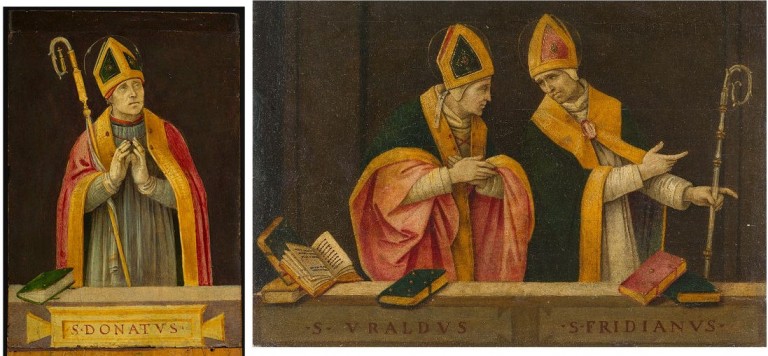

Above, Fig. 10. In 1901 the painting of Saints Uraldus and Fridianus was sold (not as a Philippino Lippi but as a Masaccio) to an English aristocrat, the Earl of Ashburnham. As with the recently proposed Haddo House Raphael (Fig. 10 above), there is little on the panel’s back other than a label in English for an exhibition of “Early Italian Art” (Fig. 10 top). For the Carolina Saint Donatus, the museum offers only a date – “circa 1490” – and the identity of the picture’s donor, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation. Such lacunae are perplexing because Filippino Lippi is a well-chronicled artist whose securely attributed works might easily be brought into direct comparison with the two more recent attributions.

Above, Fig. 11. The backs of attribution upgrades often prove problematic, and none was more so than the small panel “discovered” as a Duccio Madonna and Child (above right) in 1904 after having been bought in an antiques shop in Italy. It was then rarely seen until bought with fanfare (but no technical examinations) for $50m in 2004 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in a blind “treaty” sale conducted by an auction house among a few leading museums shortly after the picture was withdrawn from an imminent comparative exhibition of Duccio and his followers that would have introduced the painting to many scholars for the first time and in an instructive context. That withdrawal – despite the painting’s inclusion in the catalogue – might have been made out of fear of repeating the demise of the owners’ second Duccio, as described below.

The back of the tiny picture had been cradled with no fewer than eight mahogany bars and when these were later removed at the Met. a hand-written ascription to Duccio’s pupil “Segna” was found on the bare poplar wood from which painted work had been stripped. The Met Duccio contained modern wire nails, a fact not acknowledged in the museum’s post-purchase technical examination reports. When we asked after the antiquity of the nails the museum claimed they had been inserted as repairs after the panel had been cradled in the 1930s. As “proof” of that unsupported chronology it was said that one of the nails had entered one of the mahogany bars. However, as we pointed out, the head of that particular nail had been visible on the front of the frame throughout all of picture’s photographically recorded history and, while some nail heads were visible most were not and therefore had been applied before the (now heavily distressed) frame was gessoed and gilded. Thus, the panel arrived in the world at the beginning of the 20th century with modern nails intersecting a cradle that concealed an awkward ascription on a stripped-down back.

Above, Fig 12. A face painted in the 14th century by a follower of Duccio (identified by Pèleo Bacci as Segna) is shown above to the right of the face of the Met’s Duccio as it was before restorations established the blue of the Virgin’s mantle to be azurite, not the requisite ultramarine. No one ever suggested that the painting on the right was by Duccio and no one judged the Met’s picture an autograph Duccio before Bernard Berenson’s wife (Mary) in 1904 with the support of Berenson’s protégé Frederic Mason Perkins. An earlier suggestion had been that it was a work of Sano di Pietro, as Frances Vieta discovered in researches at the Frick Library, New York, that were kindly made available to us.

In 1933 Perkins attributed a second Madonna and Child to Duccio and persuaded the then owner of the Met.’s Ducio (the Belgian collector, Adolphe Stoclet) to buy it. In 1989 that Duccio was loaned to the Cleveland Museum of Art and was there identified on technical examination by Gianni Mazzoni as a fake by Icilio Federico Joni who ran a forgery factory fronted by middlemen, one of whom was Berenson’s protégé Frederic Mason Perkins.

Above, Fig. 13. A cult of Supreme Art Historical Importance was activated around the Met. Duccio and part of this mythology rested on the picture’s supposedly miraculously well-preserved, little-restored, condition. Comparison of the photographs above showing its present state (right) and an earlier state (left) discloses how extensively the work has been repainted – note the altered design of the dominant eye, and the extensive reworking of the veil. The potentially falsifying nature of restorations when determining attributions remains a conspicuously under-examined area – as does the extent and nature of repainting on stripped-down “sleepers”. (But see “A restorer’s aim – The fine line between retouching and forgery”. For a fuller account of the Met.’s Duccio difficulties, see Michael Daley: “Buyer Beware”; “Good Buy Duccio?” and “Toxic Attributions?” in the Jackdaw magazine issues of Nov/Dec. 2008, Jan/Feb. 2009, and March/April 2009.)

The Newly Upgraded Filippino Lippi (continued)

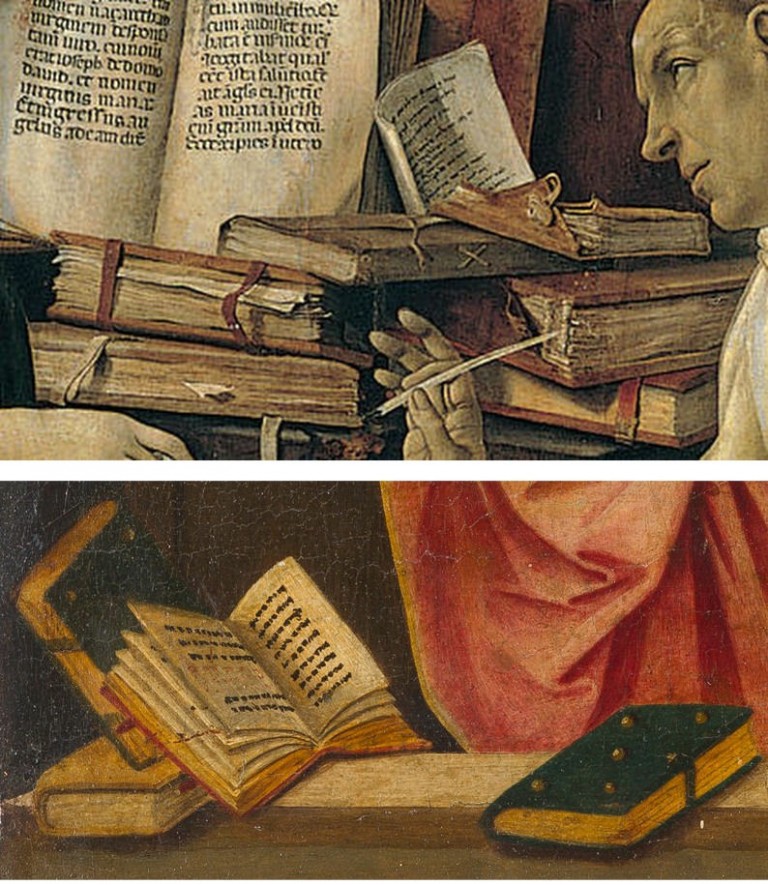

Above, Fig. 14. With the two small “Filippino Lippi” pictures at Fig. 9 and below, top, said to have been painted between 1490 to 1494, precise stylistic comparisons can be made with securely attributed works in the oeuvre. What is believed to be Filippino Lippi’s self-portrait above was executed by the artist in 1481-1482 in the Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

Above, Fig. 15. Filippino Lippi’s Apparition of the Virgin to St Bernard of 1480-86 was said by Bernard Berenson (in his 1938 revised Drawings of the Florentine Painters) to comprise “Filippino’s masterpiece, the last picture in which he is still a pure Quattrocentist, in which there is no sense of the Baroque.” Is it conceivable that some years later this artist painted the two small pictures shown here above the Apparition? Berenson reports that Filippino went on to betray excesses, not to purge and severely abstract his pictorial vocabulary: “Filippino’s Baroque, however had little in common with the qualities of the genuine [Baroque] style, and much with its worst vices. These were the sins of extravagance, of wantonness – the vulgarity of the newly enriched, who feel life is enhanced by the mere act of showy spending.”

Above, Fig. 16. At the top we see how Filippino Lippi painted books before 1486 in his Apparition of the Virgin to St Bernard and before his lapse into Baroque excesses. In this secure work we not only see great technical accomplishment but a fascination with the very means by which books were stitched together in assembled folded sections. Is it conceivable that after this tour de force celebration of the book binder’s craft skills Filippino should have been satisfied with the out-of-perspective simplifications of books in the Saint Uraldus? While the opened book has been painted in utter ignorance of book binding methods, the ochre coloured book at the bottom left of the pile has managed to anticipate to a remarkable degree the appearance of a neat modern machine-bound book.

Above, Fig. 17. Again, does the chasm of technique and sophistication in this further comparison from the Apparition and the Saint Uraldus not strain credulity at claims of a common author?

Above, Fig. 18. By 1493-94 the artist had completed his Madonna and Child with St Catherine of Alexandria and St Martin of Tours as above and we see precisely the over-elaboration Berenson castigated as Filippino’s squandering “like a nabob with a heady disorderliness all the decorative motives which the heritage of antiquity, the hard earnings of his precursors, and his own fancy had put into his hands.”

Above, Fig. 19. How conceivable is it that Filippino might, at the same short period, have made two so diverse treatments of a man parting drapery with an advancing left arm as in these two paintings? In the one the “Blanket-like drapery dear to Filippino” (in Berenson’s term), curves, twists and folds naturally across the body, while in the other it moves as if fabricated by a former sheet metal worker with little regard for any underlying body, or even for the means by which the glimpsed parts of the (wildly varying) decorative border of the cope might ever have been united as woven material. Why the arbitrary, asymmetrical placement of indeterminate embroidered decorations on the cope’s border? What holds the cope together? Is it a giant garnet or ruby, or a small tambourine? Where else in Filippino might we encounter such flattening abstractions and lax indeterminacy of depiction?

Above, Fig. 20. If the logic and treatment of Saint Donatus’ cope border (above, left) seems plausible and suitably understated, what might have carried the same artist to the Byzantine and conceptually irresolvable twin conundrums of the cope border as encountered on Saint Uraldus (above right)? What accounts for the very different depictions of the inscribed tablets on the parapet wall? If that of Saint Donatus is somewhat overly monumental and set uncomfortably close to the top of the parapet, at least it is sculpturally resolved and satisfactorily symmetrical along its horizontal axis with its twin decorative “butterfly wings” termini. Why, then, would the twinned tablets of Saints Uraldus and Fridianus meet in the middle with single butterfly-wing termini while leaving blank endings at the outer edges of the picture’s composition? Why are these two inscribed tablets skimped and devoid of projection when the saints above are greatly more dynamic and humanly engaged – almost as if in anticipation of Raphael’s later depicted dialogue between Aristotle and Plato?

Below, Fig. 21. What theological reading of Saint Uraldus’ life prompted the vast frilled neck lizard-like display of the cope’s pink lining below? If intentionally “Baroque” in its explosive ostentation and theatrical impact, why, then, its implausible combining with a geometric severity of draperies that are more snapped than folded?

With such bizarrely anomalous visual constructs, might it not be prudent to consider the waking “Filippino Lippi” sleeper as a possible product of the late 19th and early 20th century Italian forgeries boom that was tailor-made for British and American collectors? We know that many skilful artists were employed in that trade because when the Italian Government proposed stringent export taxes in 1903 to stem the country’s out-flow of art treasures, the Florentine art dealers association petitioned that the new laws would throttle the large and thriving trade in forged art and antiquities for foreign collectors. (Where did all those often excellent works go?)

At the December 2015 ArtWatch UK/LSE Law/NY Center for Art Law conference Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship (the proceedings of which will be published shortly), Professor Charles Hope pointed out how effectively 20th century scholarship had winnowed previously overblown numbers of Titians, Raphaels and such. Markets are good things and the London art market has long been a very good (much envied in Europe) force for Britain, but there are developing dangers. If perceptions were to grow that previously downgraded works are being systematically rehabilitated through “sleeper-discovery” mechanisms at a time when leading houses are fighting to the death for pole position on market share, confidence in the lots on offer might evaporate. Already, certain external structural changes are weakening the London market’s traditional and much-valued symbiotic relationship with disinterested scholarship. Increasing litigation by owners against dissenting independent scholars suppresses debate and frank expert appraisal. In a paper at our conference (“Throwing the baby out with the bath water – the Demise of Connoisseurship since the 1980s”), Brian Allen, former director of studies at the Mellon Centre, warned that recent changes of philosophy and views on connoisseurship in the academic world are greatly reducing the traditionally available body of disinterested academic expertise that counterbalances purely commercial interests:

“In my own field of British art the number of so-called ‘experts’ has now diminished alarmingly as the older generation dies off not to be replaced. It seems extraordinary to me that major artists such as Stubbs, Wright of Derby and Sir Thomas Lawrence, to name but three, don’t have an acknowledged expert to whom one can turn for a reasonably reliable, independent opinion. And this has also certainly happened in other specialist fields… Younger scholars nowadays, especially those in the universities, have almost no contact whatsoever with the art trade compared to fifty years ago. Yet for many years it was perfectly possible for the two worlds to co-exist harmoniously.”

Michael Daley 23 November 2016

Brian Sewell – Still Stinging in Death

The death on September 19th of the famously acerbic art critic Brian Sewell was generally marked by fair, balanced and sometimes touching obituary notices. For one of his critical victims, Susan Loppert, a signatory to the infamous 1994 “Gang of 35” letter calling for Sewell’s dismissal as the Evening Standard art critic, this seems to have been taken as a personal affront.

The now legendary Evening Standard letter of 5 January 1994 from thirty-five self-appointed contemporary art establishment worthies began pompously – “As members of the art world – writers, critics, artists, art historians, curators, dealers – we take the greatest exception to Brian Sewell’s writing in your newspaper…”, proceeded viciously – “His virulent homophobia and misogyny are deeply offensive, particularly the remarks made in the review of the exhibition Writing on the Wall”, and ended with pomposity, viciousness and self-pity: “We believe that the capital deserves better than Sewell’s dire mix of sexual and class hypocrisy, intellectual posturing and artistic prejudice”. This public attempt to silence a maverick critical voice was entirely self-defeating. As demonstrated below, it generated an explosion of support, catapulting the then 63 year-old art critic into a national prominence that would run for two decades.

This happy unintended outcome was, however, the exception to other manoeuvres in a bid to rig press coverage of deeply unpopular experimental art practices. A post hoc rationale for advancing against the press was given by the Tate’s director, Nicholas Serota in the 2000 Dimbleby Lecture with this plaint: “For in spite of much greater public interest in all aspects of visual culture, including design and architecture, the challenge posed by contemporary art has not evaporated. We have only to recall the headlines for last year’s Turner Prize. ‘Eminence without merit’ (The Sunday Telegraph). ‘Tate trendies blow a raspberry’ (Eastern Daily Press), and my favourite, ‘For 1,000 years art has been one of our great civilising forces. Today, pickled sheep and soiled bed threaten to make barbarians of us all’ (The Daily Mail). Are these papers speaking the minds of their readers?” Well, yes, of course they were, that is one of the things that sensible newspapers do. And that was why the articulation of such dissent posed a political threat to the contemporary art establishment’s ambitions.

COVERT MANIPULATION OF THE PRESS

The bid to unseat Sewell occurred when the Tate Gallery had become the greatest promoter of experimental art and was working closely with contemporary art dealers. In 1991 one such dealer, Jay Jopling, served on a secret Tate committee. When the editor of the art magazine Jackdaw, David Lee, later asked the Tate for the members of this shadowy committee, that gallery replied curtly that it could not say because no minutes had been taken. But why a secret committee in a publicly-funded registered charity? All businesses and institutions angle for favourable press coverage – that is why they employ large press departments. What additional purpose or purposes were best served secretly? Were there other secret committees at the Tate? Only two press accounts of this shadowy committee exist, and from these we learn that its express purpose was to plant stories to generate press coverage of, and foster interest in, what was widely reviled avant-garde art. Both insights stem from interviews with Jay Jopling when he was about to open the new White Cube gallery in Hoxton Square. The first, on 20 September 2002, was by Rose Aidin in The Guardian:

“Following a brief flirtation with film-production, Jopling started working with artists such as Damien Hirst and Marc Quinn, putting on warehouse-style shows from his Brixton home. When Nicholas Serota formed a think-tank upon his appointment to the Tate in 1991 [NB Serota had been appointed in 1988 – now some twenty-seven years ago!], Jopling was asked to join it. ‘I was very flattered to be included in this meeting to discuss how we got the newspapers to take contemporary art more seriously,’ he recalls. ‘Yet it seemed to me that if the tabloid press was only interested in ridiculing contemporary art, then get them to ridicule it properly, so that people actually take notice.