SAVE THE HITCHCOCK ODEON!

London’s architectural heritage is being devoured as a consequence of planning laxity in the face of Britain’s thriving economy and uncontrolled net inward migration (which, on official figures, is presently running at a rate in excess of three million people per decade).

That cities are living entities not museums is, as developers frequently claim, perfectly true – and migration brings benefits as well as pressures – but all that is new and lucrative is not necessarily of net social and cultural benefit. Today, every walk in the city reveals a fresh hole in the familiar and an ominous sprouting of cranes. As the Observer reports, some 400 skyscrapers are planned and 60% of Londoners oppose them. Initially clustered in the City of London, they now march westwards as planning authorities repeatedly prove toothless or supine with excesses granted in exchange for tiny “civic gains” or promised “modifications”. Every skyscraper serves immediately as precedent for a further neighbouring blight. (See also “A clear strategy on tall buildings is the only way to control developers”.)

A hideous 25-storey tower of 54 luxury flats in Somers Town that incenses heritage bodies and threatens to eclipse Nash and Burton terraces in Regent’s Park gained Camden Council planning approval by earmarking a portion of profits to a new primary school and other social purposes. The developer is none other than Camden Council itself. Further west, an approved private scheme to build forty-two townhouses and apartments in Kensington requires the destruction of the Art Deco cinema frequented by Alfred Hichcock. The (private) developers promise a seven-screen cinema amidst their housing project and to work hand in glove with the authorities “to the very highest standards”.

Cinema plus Design Museum

As the Evening Standard reports the new cinema-for-old scheme with a housing bonanza on top has triggered an imaginative and popular counter-proposal. A group, “Friends of the Kensington Odeon”, has marshalled support from 30,000 residents and a number of “philanthropic billionaires”. It propose a mixed arts centre (“The Hitchcock Odeon”) that would generate a “cultural hub” when joined nearby in November by The Design Museum. This scheme is backed by such distinguished actors as Sir Ian Mckellen, Dame Kristin Scott-Thomas, Sir john Hurt, Benedict Cumberbatch and David Suchet, and, “wholeheartedly” by Hitchcock’s daughter Patricia Hitchcock O’Connell.

Film-maker plus House

Hitchcock’s residency in Kensington was at 153 Cromwell Road. The recent history of that house testifies to a certain enduring commercial rapacity, as one of its present culturally distinguished residents, Selby Whittingham, outlines below. In 1975 Dr Whittingham, a student of medieval art and a devotee of both Watteau and Turner (two of the more restoration-vulnerable painters) founded a campaign for the creation of a proper and fitting Turner Gallery to house Turner’s great bequest. The campaign enjoyed much support – including that of Henry Moore, Hugh Casson, Kenneth Clark, and John Betjeman – and its committee meetings were held at 153 Cromwell Road until ended by dissensions that have left the realisation of a Turner Gallery unfinished business.

Selby Whittingham writes:

HITCHCOCK HOUSE AND OTHER DRAMAS

A recent proposal has been made, supported by cinematic celebrities, that the Odeon Kensington should become a new arts centre, The Hitchcock Odeon. The name was presumably prompted by the occupancy of the Kensington house where I have lived since 1970 by Alfred Hitchcock during the 1930s following his marriage at the Brompton Oratory, in token of which his daughter (Patricia Hitchcock O’Connell) unveiled a blue plaque on the centenary of his birth in August 1999.

The plaque celebrating Alfred Hitchcock’s residency at 153 Cromwell Road Kensington from 1926 to 1939

The Kensington Odeon was where I saw my first film, Scott of the Antarctic. I had come with my mother 70 years ago to live at 1 Scarsdale Villas, the previous tenant of which was Lady Benson, whose husband, Sir Frank, had toured the country with his company of actors selected mainly for their ability to play cricket. They had inspired my mother with a love of Shakespeare, which she transmitted to me. Lady Benson’s drama school was where John Gielgud received his first training as an actor. After her death the studio at the back reverted to being that of an artist called Maclaren, a loner of rather sinister appearance. It had been built for an illustrator, Leslie Brooke, ancestor of the onetime Culture Minister, Peter Brooke. Maclaren left and his place was taken by Flanders and Swann, attempts to commemorate whom with a blue plaque have so far been thwarted.

Alfred and Alma Hitchcock in their 153 Cromwell Road sitting room with a production secretary, right, taking notes. The photograph above comes from The Life of Alfred Hitchcock: the Dark Side of Genius by Donald Spoto.

In the 1930s many London cinemas were part of the Gaumont British empire controlled by the Ostrers. The presiding genius was Isidore Ostrer, for whom my mother-in-law worked for 30 years. One of his daughters married James Mason and another is my wife’s lively godmother. The history of the family and its eccentricities has been chronicled by Isidore’s nephew, Mark Ostrer, who has improved his portrait by Picasso, he says, by partially repainting it. In the 1970s he lived in Earls Court in a mews house, where he hid under the floorboards (where they remained when he sold it) giant tins of baked beans in preparation for World War III.

In the 1930s many London cinemas were part of the Gaumont British empire controlled by the Ostrers. The presiding genius was Isidore Ostrer, for whom my mother-in-law worked for 30 years. One of his daughters married James Mason and another is my wife’s lively godmother. The history of the family and its eccentricities has been chronicled by Isidore’s nephew, Mark Ostrer, who has improved his portrait by Picasso, he says, by partially repainting it. In the 1970s he lived in Earls Court in a mews house, where he hid under the floorboards (where they remained when he sold it) giant tins of baked beans in preparation for World War III.

That may not have broken out yet, but since 1983 at Hitchcock’s former home there have been intermittent skirmishes between the leaseholders which have enraged them and successive managing agents. In 1970 the superior lease was owned by a benevolent lady living nearby in Cornwall Gardens. She now decided to sell it. The purchaser was an outfit called Stateplan Ltd, of which the directors were Simon Longe and Richard Weston, who thought that they could make money by splitting up the two maisonettes (the top one having been Hitchcock’s) and two flats into a series of studio flats, the leases for the unexpired term being sold to the occupants and newcomers.

Longe started a series of enterprises which, like Stateplan, failed, and Weston, who practised as a solicitor at Taunton, was struck off the roll in 1991 and fined a few years ago for pretending to be a qualified solicitor. These geniuses helped provoke a new Thirty Years War. Weston drew up our lease whereby we would pay service charges in proportion to the relative values of the flats, there then being still only four, which of course changed after new ones were created, making nine in total. But in the leases he subsequently drew up for the new ones he took no account of that, with the result that we were at loggerheads with other owners almost from the start.

The inconsistency, and the consequent overcharging of ourselves, was quickly pointed out by our solicitors, Loxdales, also of Cromwell Road. A century ago they had acted for Sir Thomas Beecham, whose American father-in-law lived in South Kensington, in his dispute with his father, who had upset him by banishing his wife, Thomas’s mother, to a mental asylum. The father had as his lawyers my great-grandfather and grandfather. As a teenager I photographed his first wife in the garden of Clopton Manor, from where she claimed several of Shakespeare’s most famous scenes took their origin, a claim treated with contempt by a Shakespearian professor who called on me at Hitchcock House, which I had earlier named Turner House (I had founded the Old Turner Society there in 1975), in pursuit of his wife’s claim to be related to J.M.W.Turner, just as Lady Beecham claimed a family relationship to Shakespeare.

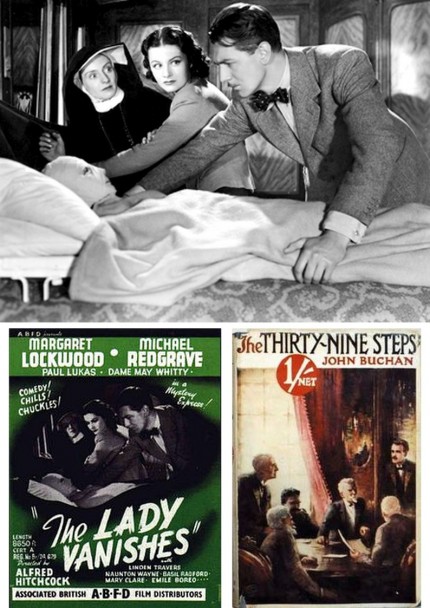

Mr Longe had promised to put the whole house in good repair before he started levying service charges. This did not happen. After the bedlam of the conversion of the other flats there suddenly collapsed the ceiling over the impressive staircase, up which luminaries such as G.B.Shaw and Michael Redgrave, whose rehearsals at Stratford I once witnessed, trod as Hitchcock worked on films such as The Lady Vanishes and Thirty-Nine Steps. Great chunks of plaster landed outside our flat door, through which I had passed minutes before. An even more impressive staircase in Belgravia was centre stage in a film by Graham Greene and Carol Reed in which my cousin Bobby Henrey, its boy star, imagined (or was it real?) he saw, as he leant over the banisters, a murder committed. (His mother wrote a book about the making of the film and more recently Bobby has published his own account). There have been no murders on our staircase, real or imagined – so far.

Next a water tank in the roof burst flooding many flats including ours. Repeated inundations afflicted the half-landing room which formed part of our “flat”, the lessors refusing to repair its roof, on to which all sorts of rubbish mysteriously landed making the flooding worse. Eventually we sold it to other leaseholders for a modest £12,500 on condition that our percentage of the service charges, which after 15 years of stalling had been reduced, should be further reduced. They reneged on the agreement to do that. They adapted the room to make a self-contained pied-à-terre which now must be worth at least ten times what they paid for it. Yet they felt indignant at having to pay the agreed increase in service charges, enforced only 10 years later after we took the matter to a tribunal, or indeed any service charges at all on it.

They named the studio Flat 2B (ours being 2). When we pointed out that it constituted a tenth flat, but was not listed among the flats paying service charges, all signs indicating 2B disappeared. At the tribunal it was still claimed that it was still just a spare room, though the council had at last got round to acknowledging its existence and had registered it as liable for Council Tax! We had drawn the council’s attention to its existence earlier, but it had done nothing and now said that it was too late to prosecute the owners. The Royal Borough moved in a similarly stately way over Leighton House, only accepting it long after all the contents from Lord Leighton’s time had been sold.

Troubles continued over the years and some disgruntled leaseholders sold their flats. At the top of the house remained the panelled room which the Hitchcocks had as their living room, decked out for them by Heal’s, while the bedrooms were on the floor below. On hearing that the panelling was being sold by its departing owner, Sandra Shevey, biographer and interviewer of Hitchcock and organiser of Hitchcock Walks, complained to the council, which again declined to do anything. Yet the house, if anywhere, should be Hitchcock’s London shrine. The dramatic spirit which invests it, and which has suspended our hopes of justice for so long, indicates that his ghost lives on in the crucible of his first triumphs.

Selby Whittingham, 30 August 2016