The Art World’s Toxic Assets – Part III: Failures of Scrutiny

Within a couple of years of our warnings on the art world’s accumulating toxic assets of upgraded Old Master attributions, that sphere has been rocked by a spate of discovered/alleged old master forgeries that have recently deceived and embarrassed leading experts and major institutions alike.

In the midst of this turmoil, a Raphael-esque painting of insecure provenance (which is to say, of none before 1841), that relates to no known Raphael work, that is said to be good in parts and perhaps to have been a fragment of a lost unknown painting by Raphael, was launched to the world in the Guardian on October 3rd as a provisional “discovery” (“Raphael ‘copy’ once valued at £20 may be a £20m original”) to be shown on 5 October in a new three-part BBC4 series, “Britain’s Lost Masterpieces” [see Figs. 1a and 1b below]. The programmes were co-presented by an art historian, Jacky Klein, and a fast rising young player in the Old Masters attributions field, Bendor Grosvenor. Formerly of the Philip Mould Gallery and the BBC “Fake or Fortune” series, Grosvenor doubles as an art market commentator on a blog site, “Art History News” and, occasionally, for the Financial Times.

In the 8/9 October Weekend FT (“An eye for the real thing”) Dr Grosvenor held that the recently exposed failures of judgement constituted a scandal that threatens “to undermine the art world’s long established system of deducing authenticity”. He suggested that this danger stemmed from too great a reliance on the judgements of “independent, usually academic” experts who have published works on the artists they appraise, and from insufficient heed being paid to those (by implication like himself) who have not studied art history or published on artists but who, nonetheless, possess a “good eye”.

This recommendation was advanced even as Grosvenor admitted that he, along with France’s National Centre for Research and Restoration at the Louvre; a leading Louvre curator; numerous Frans Hals scholars; the Burlington Magazine; Christies (on scholarly advice); the Weiss gallery; and, Sotheby’s (at first), had been deceived by a recently exposed fake Frans Hals [Fig. 2, above], and, that he had come within a whisker of being deceived by a Gentileschi fake that snared the Guardian art critic and blogger, Jonathan Jones, and the National Gallery which had accepted the work as authentic when it was offered on loan (“Was the National Gallery scammed with a fake Old Master painting?”).

Where we held in the April 2006 ArtWatch UK Journal [Fig. 3, above] that too many in the art world were disregarding Mark Twain’s admonition to “buy land because they are not making it anymore” when buying upgraded school works as autograph masterpieces, Bendor Grosvenor often declares a state of rude good health in the old masters market. Because so many old masters have already been taken off the market and into museums, and because, by definition, old master paintings are no longer being produced, market growth increasingly depends on the discovery of “sleepers” – which is to say, of suspected hitherto unrecognised major works whose true identities will emerge during dealers’ un-monitored, sometimes radical stripping-down, repairing and retouching of paintings. (More recently we published a post that indicated means by which restorations might slide towards outright fakery in cases which, coincidentally, involved earlier “Frans Hals” paintings. See “A restorer’s aim – The fine line between retouching and forgery”.) On 13 August 2014 we called in a letter to The Times for a statutory requirement for vendors to disclose all that is known on a work’s provenance and conservation history [see Fig. 4, below]

On the BBC4 series “Britain’s Lost Masterpieces” Bendor Grosvenor got very excited at the prospect of a distinctly Raphael-esque painting in Haddo House in Scotland being an autograph Raphael [Fig. 1a]. BBC coverage of the visual arts rarely airs dissenting voices and this programme was constructed with many narrative layers all of which sang the same encouraging tune: Although this work has little provenance we should be assured by the fact that it had been bought in the early 19th century as an autograph Raphael by the 4th Earl of Aberdeen, George Hamilton-Gordon (1784-1860), who, in his early years and travels, was an impassioned devotee of the classical arts of Greece and Italy, and who somehow managed, despite being “flat broke”, to acquire a fine collection through a “shrewd nose for bargains”. Particular assurance was seen in the fact that the picture had been exhibited as a Raphael at the British Institution in 1841. However, an old hand-written label attached to one of two oak bars that reinforced the back of the poplar panel says, in English, “The Virgin Mary, Raffael or after Raffael” [see Fig. 1b]. As that is the only documentation (other than an indecipherable fragment of a wax seal) on the back of an assumed 500 years old panel, it would seem likely that the label was present when the painting was exhibited in 1841 as a Raphael. If it had not been present in 1841, why would its owner have added such a weakening document to his own painting?

The question of the label’s origin is the more perplexing because, as we now learn from Dr Grosvenor, the canny Scottish Fourth Earl of Aberdeen, George Hamilton-Gordon, had not bought the painting while on his early travels in Italy because he had not bought it all. Rather, he had inherited it more than a generation later from his brother, Robert Gordon, when he died in 1847 (by choking on a fish bone). The provenance thus descends entirely from Robert Gordon who was born in 1791 and would not likely have bought the painting (from whomever – for no one knows) much before 1810. Although Robert Gordon was the owner when the picture was exhibited at the British Institution, there are no family inventories listing the painting before 1867 and none thereafter lists it as a Raphael. In two entries it is priced at £80 and later at £20. On both occasions it was listed as a copy. In the television programme, the co-presenters describe seeing their perceived challenge as being to reverse a hypothecated “increasing scepticism” with which the painting was viewed after George Gordon’s death in 1860. But what if the Raphael attribution had always been appreciated within the family as being uncertain? Or, might not a contrary reading have been considered of the possibility that it only became politic for independent scholars to dissent on a claimed Raphael attribution after the death of the fourth earl who had been an extremely powerful and well-connected political figure – and one with with a sarcastic turn to boot?

Against the fragmentary picture’s distinctly weak provenance, it was claimed (- but not demonstrated) that a close fit existed with secure Raphael Madonnas. The belief that this work might be an autograph Raphael received high level scholarly and (implicit) institutional endorsement as Bendor Grosvenor is filmed ascending the grand stairs of the National Gallery’s Sainsbury Wing in the company of the Gallery’s former director, Sir Nicholas Penny. The camera catches the pair passing the monumental carved Roman Letters “RAPHAEL” [see Fig. 5, below] and jumps in a nanosecond to a painting in the Gallery’s substantial Raphael holdings – but not to one its finest, instead to the least secure, most recent, so-called Madonna of the Pinks that had been attributed to Raphael in 1992 by Nicholas Penny when a curator at the Gallery, and that was later bought by the Gallery for nearly £35millon after a public appeal. Towards the end of the film [Fig. 6, below] Nicholas Penny places the putative Grosvenor-Raphael, somewhere between “probably by Raphael” and “by Raphael” and suggests that with a little “more time and courage” he might well go the whole hog.

Above, (top – and running clockwise), Figure 5: Bendor Grosvenor passes the monumental carved “RAPHAEL” in the National Gallery’s Sainsbury Wing; the National Gallery’s (disputed) Raphael Madonna of the Pinks; the Bendor Grosvenor-proposed Haddo House Raphael Madonna, before restoration; and, the National Gallery’s Madonna of the Pinks, as presently framed. Above, Fig. 6: Jacky Klein, Bendor Grosvenor and Nicholas Penny seen examining the Haddo House Madonna in the 5 October BBC4 “Britian’s Lost Masterpieces” programme.

Although a caveat was offered in the programme (and reported in the Guardian) with an admission that there had not been the time and money to run all appropriate tests, Grosvenor nonetheless claimed that all the evidence seemed to point in the right direction. As if to dispel any doubts, the television programme (which was produced by Tern TV and commissioned by Mark Bell, Head of Arts Commissioning, BBC, under the Executive Producer for the BBC, Emma Cahusac) carried a strong implicit message that the Grosvenor-proposed Raphael is as sound as the National Gallery’s Penny-attributed Raphael Madonna of the Pinks. We would counter that, with both pictures, such assurances were misleading and that the principal evidence on the strength of these attributions is found in the look of the pictures, which testify in different ways[ see Fig. 5] against Raphael’s authorship, as will be shown in Part IV.

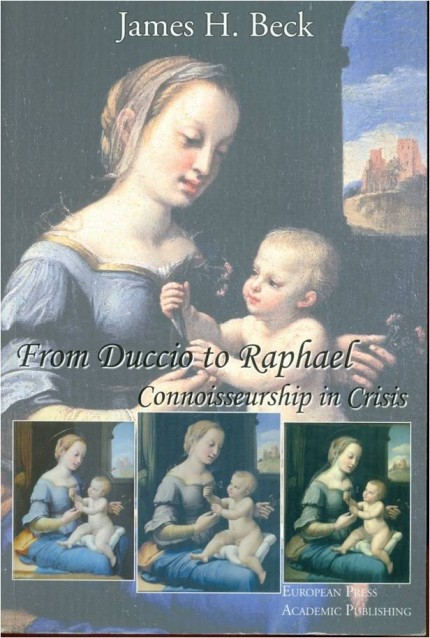

We would add two points here. First, that Dr Grosvenor seems unaware of the extent to which the Madonna of the Pinks had been rejected as by Raphael in the 19th century and more recently by scholars including Professor James Beck, the founder of ArtWatch International who devoted three chapters of his last (2006) book, From Duccio to Raphael – Connoisseurship in Crisis, to problems with the present attribution [see Fig. 7, below]. Although Nicholas Penny is a highly respected Renaissance specialist, and his Raphael attribution had been fittingly proposed in a long, thorough scholarly article in the Burlington Magazine (“Raphael’s Madonna dei garofani” Rediscovered, 134, 1992) that had impressed Professor James Beck, the attribution itself received only majority approval from a group of specialist scholars assembled at the National Gallery. Contrary to initial Gallery press claims, there had been no firm consensus of scholarly opinion – a fifth of the invited scholars dissented from the attribution when questioned directly by Beck.

At the time, we pointed out that the then majority for support had reversed over a century’s scholarly consensus of judgement. The Penny-Raphael had been rejected as early as 1854 by Gustav Friedrich Waagen as “the small picture in the Camuccini collection which I do not consider to be original. The tone of the flesh has something insipid and heavy. The Treatment makes me suspect a Netherlandish hand.” Professor Martin Kemp rejected the Penny-Raphael Madonna on the grounds of her most disconcerting and uncharacteristic teeth-baring opened mouth: “In reality, for any Renaissance woman to be portrayed showing her teeth, American-style, is unthinkable”. (Leonardo, Oxford/New York, 2005, p. 242.)

There were structural problems with the picture, as well as stylistic incongruities. In the 2003 ArtWatch UK Journal 29, we drew attention to the disturbing fact that the National Gallery’s Madonna of the Pinks Raphael – like the Gallery’s (challenged) Rubens Samson and Delilah painting – had lost vital physical and documentary evidence. With both paintings the original, evidence-bearing back is missing, as is also the case in the drawing that has been dubbed “La Bella Principessa” and given to Leonardo da Vinci by Martin Kemp, even after it emerged that the supposedly 500 years old work had been sold anonymously and without a shred of provenance by the widow of a restorer who was the work’s first known and sole owner. That atypical drawing on an atypical medium has been (unusually) glued down onto an oak panel, thereby preventing an appraisal of drawings known to be present on its reverse.

The Samson and Delilah panel painting had been planed down to wafer thinness and glued onto a modern sheet of blockboard in an operation of which no record exists. The back of the Madonna of the Pinks was “polished”, coated and given three wax seals in the 19th century when in the hands of its first known owners, the notorious Camuccini family

of artists, copyists, restorers, art dealers and art smugglers. We cited much else that was problematic about the Madonna of the Pinks:

“It possesses, for example, an irregular border of unpainted wood that is ‘unusual’ for Raphael. The picture’s unusually highly-wrought finish, ‘jewel-like, as Dr Ekserdjian and associates put it; made up of ‘tiny, almost invisible brushstrokes’, as the National Gallery puts it, is said to have been the result of the work’s especial execution for the close contemplation of a nun…Even if this fanciful explanation for the unusual brushwork were to be accepted, it would not also explain the picture’s atypical colour scheme [which] Dr Penny suggests, may reflect ‘a particular moment of indebtedness by Raphael to Leonardo…’ ”

We complained that “Dr Penny’s case seems to rest on the belief that the outcome of technical analysis carried out at the National Gallery somehow displaces or neutralises all accumulations of otherwise awkward evidence…A manifest weakness of Dr Penny’s case is that no technical analysis or even photographic comparison is offered on any of the picture’s forty or so rival contenders…” It was later learned that scientific analysis had identified the wood of this most unusual artefact as being, not poplar, as might have been expected, or even a fruit wood, as is the case with one large Raphael panel, but yew – a wood nowhere encountered in Raphael or, so far as we know, in any Italian Renaissance painting. As will be seen in Part IV, the proposed Grosvenor-Raphael bears many handicaps.

Michael Daley, 20 October 2016

Leave a Reply