A bodge too far: “Conservation’s” catalogue of blunders

Throughout the world, Museum folks will go to any length to achieve a “good press”. Press releases are never issued announcing freshly dropped, smashed, trampled or restoration-injured works of art but are confined to Good News stories. Bad news about the condition of works only ever…leaks out.

Accidents in museums are concealed for as long as possible or are artfully spun when disclosure is unavoidable. The National Gallery’s director, Nicholas Penny, disclosed in 2000 that “museum employees are obliged to stifle their anxieties”. When, for example, a brand new state-of-the-art conservation standard synthetic board plinth collapsed under the weight of an important Renaissance marble sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, smashing it into a thousand pieces, photographs of the injuries were withheld and a suave assurance was given that all would be put back together within a couple of years. In the event, it took twelve years not two to reassemble this irreplaceable Humpty.

In museum circles even prolonged setbacks in conservation treatments provide eminently spinnable opportunities.

When restorers at the National Gallery in London were unable to reconfigure a skull they had stripped down during a BBC televised restoration (see The new relativisms and the death of authenticity), a long research programme was launched which resulted in a piece of computer-generated virtual reality being painted (along with fake lines of craquelure) into a Holbein picture.

At this very moment, the Met’s prolonged patch-up is being celebrated as a triumph of modern conservators’ scientifically aided collective brilliance. It is being said that the world is now much better prepared for the next marble figure to fall off its plinth. (It might be preferred that conservators build structurally sound plinths in the first place – or leave ancient sculptures on their ancient, period plinths.)

A TURNING TIDE?

In Egypt a lightning-swift but mysterious treatment of an injury far less serious than those at the Metropolitan Museum – where plinths collapse and sculptures fall off walls – has captured the imagination of the world’s press (see below). It would seem that by grossly over-selling modern, “scientifically” armed conservators as infallible miracle-workers, museums have succeeded in making their routinely and successive mishaps all the more newsworthy and ever-richer providers of public merriment.

Above: a detail showing a repair to the beard of Tutankamun’s death mask, which is housed and displayed in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. The Daily Telegraph reported that while some say the beard had been broken off by cleaners, other say that it had simply come loose (“Museum’s quick fix for King Tut’s broken beard: stick it back on with glue”). Three conservators, speaking anonymously, had given three different accounts of the injury, but all agreed that orders had come down for the repair to be made quickly. A tourist reported that the (“slapstick”) repair had been made last August in the museum, in front of a large crowd and without proper tools, as seen the Associated Press photograph below.

Above, top, the death mask before the accident.

Above, centre, the beard being re-attached to the mask. The Daily Mail reported:

“This is the moment the blue and gold braided beard on the burial mask of famed pharaoh Tutankhamun was hastily glued back on with the wrong adhesive, damaging the relic after it was knocked during cleaning…

The mask should have been taken to the conservation lab but they were in a rush to get it displayed quickly again and used this quick drying, irreversible material,’ they added.

The curator said that the mask now shows a gap between the face and the beard, whereas before it was directly attached: ‘Now you can see a layer of transparent yellow’.

Another museum curator, who was present at the time of the repair, said that epoxy had dried on the face of the boy king’s mask and that a colleague used a spatula to remove it, leaving scratches.

The first curator, who inspects the artifact regularly, confirmed the scratches and said it was clear that they had been made by a tool used to scrape off the epoxy.”

Above, the repaired mask showing the ugly and disfiguring bodge. Mystery fuels both speculation and conflicted accounts. The Guardian’s take went as follows:

“Did bungling curators snap off Tut’s beard last year, and if so was it stuck back on with with the wrong kind of glue?

These are the allegations levelled at the Egyptian Museum, the gloomy, under-funded palace in central Cairo where Tutankhamun’s bling is housed. Employees claim the beard was dislodged in late 2014 during routine maintenance of the showcase in which Tut’s mask is kept…The director of the museum, Mahmoud el-Halwagy, and the head of its conservation department, Elham Abdelrahman, strenuously denied the claims yesterday. Halwagy says the beard never fell off and nothing has happened to it since he was appointed director in October.”

Above, the Daily Telegraph’s (incomparable) “Matt”, 24 January 2015. See also: “By Tutankhamen’s beard: worst ever botched restorations”; and, “King Tut’s broken beard and other art disasters”; “King Tut’s beard ‘hastily glued back on with epoxy'”.

Above, the Times (“Tut’s beard in restoration comedy”) produced the most elaborate accompanying graphics, showing (top) a fresco from Tutankhamun’s tomb that is being devoured by the pollution and humidity introduced by as many as 1,000 visitors a day, as well as the mask and its injury to the beard. In the April 19/20 FT Weekend Magazine, Peter Aspden (“Welcome to the age of ‘Facsimile tourism'”) described an attempt to thwart the destructive cycle of decay and damaging restoration inside the tomb by diverting its visitors to a life-size three-dimensional facsimile. (Our complaint that restorers have long been “turning unique and irreplaceable artworks into facsimiles of their supposed original selves” was cited in the article.)

When news broke of the 81 years old painter Cecilia Gimenez’s disastrous restoration of a painting of Christ in her local church, the world fell about laughing (see “The ‘World’s worst restoration’ and the death of authenticity”). The distressed restorer took to her bed as people queued to see her infamous monkey-faced Christ and, wishing to preserve the hilarity, over 5,000 wags signed a petition to block Professorial Conservationists attempts to “return the painting to its pre-restoration glory” – as if such an outcome might credibly be in prospect.

When Ms Giménez’s unauthorised restoration of Ecce Homo – Behold the Man caused the work to be dubbed Ecce Mono – Behold the Monkey the Church authorities threatened to sue – and then quickly levied a visitors’ charge when the church became an overnight tourist attraction with Ryanair offering cut-price flights from the United Kingdom. With everyone in the world beginning to appreciate that restorations really can damage art, conservation lobbyists swiftly attempted to counter the professionally menacing dawning realisation. What caused particular alarm was recognition that although Giménez’s restoration may have been an extreme case, it was not an aberration within wider professional conservation practices – as we demonstrated in “The Battle of Borja: Cecilia Giménez, Restoration Monkeys, Paediatricians, Titian and Great Women Conservators”. (See also “Restoration Tragedies: A ruinous attempt to repaint a Spanish fresco has highlighted the dangers of art restoration” in the 23 August 2012 Sunday Telegraph.)

On 23 October 2013 the Daily Telegraph reported how a Chinese Government-approved, £100,000 restoration of a Qing dynasty temple fresco (above) left the work entirely obliterated by luridly colourised re-painting. That crime against world-ranking art and heritage came to light when a student posted comparative photographs online. In the resulting furore, a government official from the city responsible for the temple claimed that the restoration had

been “an unauthorised project” – in China, as if. (See NEW YEAR REPORT.)

BODGES AND RE-BODGES IN THE WORLD’S HIGHEST INSTITUTIONS (SUCH AS THE LOUVRE AND THE PRADO)

HOW MUSEUMS HARVEST THE VALUE OF THE ART THEY HOLD IN TRUST

The present museum world rupture between words and pictorial realities is the product of an over-heating international scramble to produce money-spinning blockbuster exhibitions. The director of Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas P. Campbell, boasted that:

“no one but the Met could have pulled off the exhibition of Renaissance tapestry we had here a few years ago, where there were forty-five tapestries on show. The politics involved, the financing involved, the leverage, and the expertise involved: No one else had that. We bribed and cajoled and twisted the arms of institutions around the world – well, we didn’t bribe, of course – but politically it was very complicated negotiating the loan of these objects”.

After prising and pulling together works from all corners (see “How the Metropolitan Museum of Art gets hold of the world’s most precious and vulnerable treasures”), curators of temporary exhibitions write as if blind to the most glaring differences of condition seen in the assembled works of an oeuvre, and as if ignorant of all restoration-induced controversies. This critical failure to address the variously altered states of pictures manifestly corrupts scholarship and confers international respectability on damaging local restoration practices. (See “From Veronese to Turner, Celebrating Restoration-Wrecked Pictures”.)

In our 2 February 2011 account of the European Commission’s desire to speed the “trafficking” (as it were) of art

objects between European museums (“The European Commission’s way of moving works of art around”), we cited the following rationale by Androulla Vassiliou, the European Commissioner for Education, Culture, Multilingualism and Youth, in her introduction to the brochure “The Culture Programme – 2007-2013”:

“I am especially happy to highlight the importance of culture to the European Union’s objective of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. At a time when many of our industries are facing difficulties, the cultural and creative industries have experienced unprecedented growth and offer the prospect of sustainable, future-oriented and fulfilling jobs.”

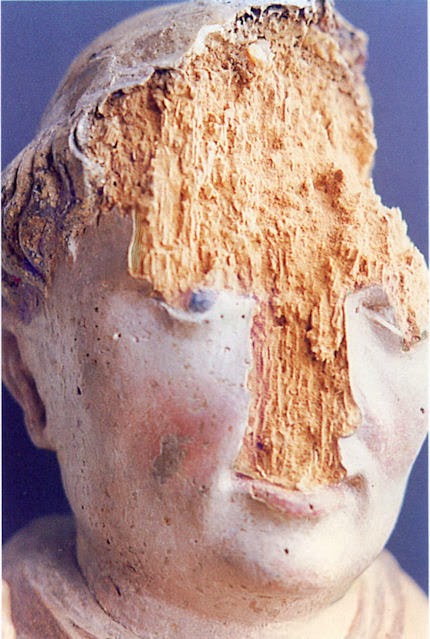

Michel Favre-Felix, President of ARIPA (Association Internationale pour le Respect de l’Intégrité du Patrimoine Artistique), drew our attention to the work shown below. It is a 14th century polychrome sculpture of Saint-Bernard. During the Benedictus Pater Europae exhibition (Gand 1981), the statue was knocked over, with the resulting loss of the major part of its face. Insurers insisted that the injuries stemmed from “pre-existing fragilities”. In 1991 the art insurer Hiscox stated that risks for works of art were ten times higher when on loan than when left at home. In 2007 Axa Art in France estimated the risks in loan venues to be six times higher than in permanent residences.

(The photograph by courtesy of © R.H.Marijnissen.)

BELOW, HOW THE NATIONAL GALLERY DID BAD, THEN GOOD, THEN BAD AGAIN

In 2008, the National Gallery’s Beccafumi panel Marcia (below) was dropped and smashed when being removed from a temporary exhibition at the gallery. (See Attacked Poussins at the National Gallery.) Insurance cover was not involved

but the consequences of the accident were enormous. The panel was immediately re-glued (without authorisation by any other than the chairman of the board of trustees and the head of conservation who was also the then acting director) and repainted. The painting is one of pair from a larger suite of works. The Marcia and her sister panel, the undamaged Tanaquil, were not returned to the main galleries after the incident. Instead, they were both consigned to the gloom of the gallery’s reserve collection which could be accessed by the public for only a few hours each week. (The reserve collection galleries have recently been turned into a gallery proper that shows fewer works – and not the Beccafumi Two. Other restoration embarrassments have disappeared from view. On an embarrassingly well-preserved Giampietrino, see The National Gallery’s £1.5 billion Leonardo Restoration.)

Some time later that incident was disclosed on the gallery’s website among the board minutes. After we reported the accident in our Journal, the gallery’s director, Nicholas Penny, made a copy of an internal report and photographs of the smashed painting available to us. For once, there was no cover-up, and the lesson seemed clear to all. But the damage done to an important pair of paintings is forever. Any movement of a fragile Renaissance panel – even within a gallery – constitutes a risk. Unnecessary movements constitute unnecessary risks. The National Gallery’s restorers made a whole series of mega-bungles with some of its greatest large works, such as Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, Sebastiano’s The Raising of Lazarus, and Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières. Such works were glued down – flattened – onto sheets of Sundeala Board – a proprietary board made of compressed paper. That board has proved unsuitable. It has lost its initial rigidity and now flexes alarming when handled or moved. Not all of conservation’s clowns live in Egypt, Spain or China.

Instead of retreating, museums are advancing. At the British Museum even the holdings of Parthenon sculptures are

now being harvested for exchange loans of irreplaceable masterpieces. Calamity awaits. The Vatican, having wrecked Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, is to loan one of the great classical works that informed the artist’s treatments of the nude figure – the Belvedere Torso – to the British Museum. Museum directors are presently binging on the institutional benefits of playing global impresarios/ambassadors with the greatest art that is held in trust. Museums are increasingly being turned from havens into transit depots. Such practices are unthinkably irresponsible. They would not likely be indulged if trustees were held personally liable for losses and injuries.

24 January 2015

Leave a Reply