The Consequences of “Cleaning” Pictures

Pride and Prejudice and Patina ~ A most welcome – and potentially explosive – art cultural event is to take place in New York. Professor Salvador Muñoz Viñas is to discuss the great complexities and the (often adverse) consequences of “cleaning” pictures.

Those lucky enough to attend this lecture might wish first to read Professor Muñoz Viñas’s own philosophically intriguing (and art-politically fair-minded) 2005 book Contemporary Theory of Conservation (see below), and an account of the significance of (even discoloured) varnishes in the proper apprehension of paintings that was given and published by our French colleagues in ARIPA as: “The pictorial role of old varnishes and the principle of their preservation” and “Le rôle pictural des vernisanciens et le principe de leur conservation”.

PRIDE AND PREDJUDICE AND PATINA ~ a Lecture in New York

Salvador Muñoz Viñas

Professor and Head of Paper Conservation

Universitat Politècnica de València

Monday, February 9, 2015, 6:00 PM

The Institute of Fine Arts

1 East 78th Street

New York City

Seating is limited – RSVP required: click here

Seating in the Lecture Hall is on a first-come, first-served basis with RSVP. There will be a simulcast in an adjacent room to accommodate overflow.

About the Lecture:

The decision to clean a painting may seem relatively straightforward upon first glance. However, when the decision-making process is carefully analyzed, different, unexpected variables are bound to arise. One of the main problems in this regard is that it may be difficult to precisely ascertain what “clean” means when speaking of paintings. The kaleidoscopic notion of patina is perhaps a consequence of this basic indetermination, and thus reflects the varied attitudes towards what we call the “cleaning” of artworks. Yet, however different, these attitudes share a basic trait: they are all based on a standard classical conservation narrative. Borrowing from Caple’s “RIP model,” this classical narrative can be summarized by describing the main goals of conservation as the “revelation,” “investigation” and/or “preservation” of truth. This widespread narrative, however, is not devoid of problems. As any reader of Sherlock Holmes (or any CSI fan) knows, dirt may be very important when it comes to determining truth. Cleaning, i.e., the removal of dirt, may thus askew the truth, and mislead the observer in some way. The classical conservation narrative is at odds with this potential incongruence; and, in turn, it suggests there may be certain reasons for cleaning that vary from those which are commonly accepted in the heritage world.

About Salvador Muñoz Viñas:

Dr. Salvador Muñoz Viñas is a Professor at the Universitat Politècnica de València and the head of Paper Conservation at the University’s Conservation Institute. He is also a Fellow of the International Institute for Conservation. His teaching and research work revolves around both the theory of conservation and the technical aspects of paper conservation. He has published several books on these topics, including Contemporary Theory of Conservation (Oxford, 2005), which has been translated into several languages, such as Chinese, Persian or Italian, and has been said to “bring conservation into the 21st century” (C. Hucklesby, An Anthropology of Conservation).

For more information on the Judith Praska Distinguished Visiting Professor in Conservation and Technical Studies, click here.

Public lectures at the Institute of Fine Arts are made possible by our generous supporters. Please make a gift today to help the IFA continue providing superior public programming for years to come. Click here to make your gift online to the IFA Annual Fund, or find out more information about supporting the Institute.

22 January 2015

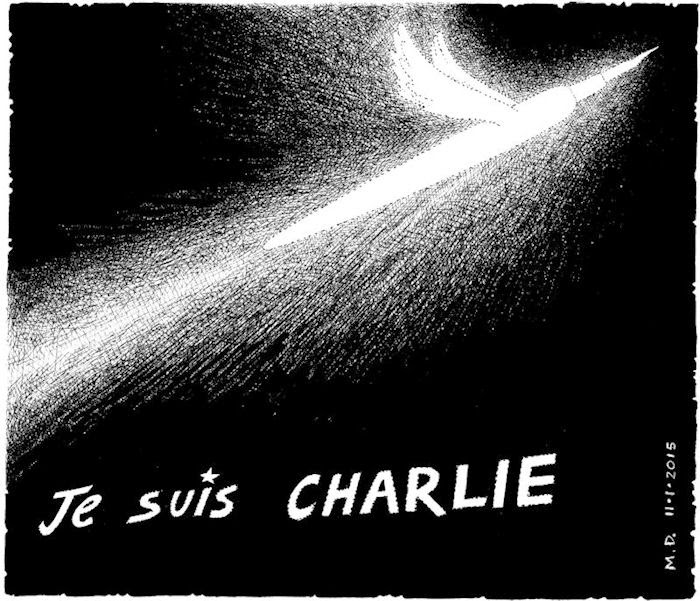

Je suis CHARLIE

Some talk of Alexander, and some of Hercules.

Of Hector and Lysander, and such great names as these…

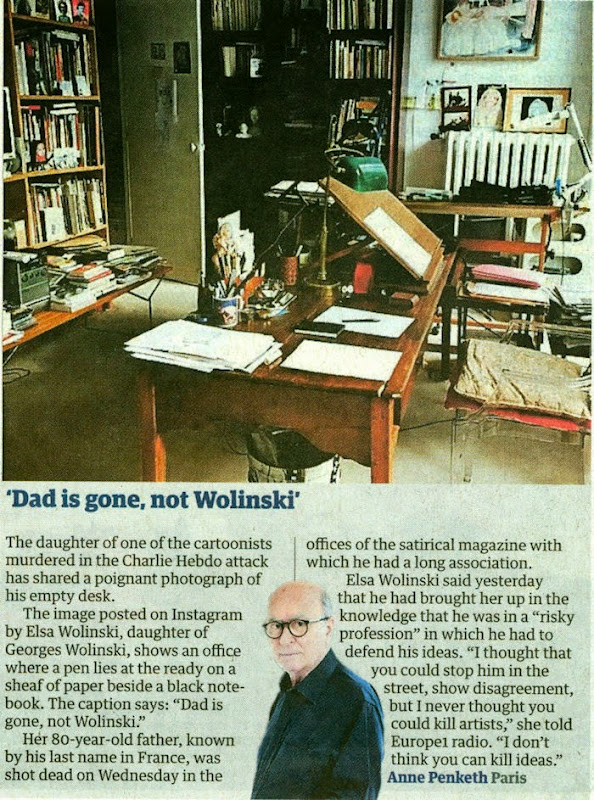

…Elsa Wolinski has lost her Dad (as the Guardian reported) but, indeed, he is not gone. Evil might still a pen but it cannot expunge the courage of those who dared to use it. Her Dad and his brave colleagues will be remembered: the very blackness of the deed makes their light the more brilliant – and their example the more certain of enduring.

An ArtWatch member in France reports:

“It has been an extraordinary week here in France. The marches yesterday were incredibly moving, and it was wonderful to see such a positive spirit emerge from such appalling and shocking circumstances. In our home town of Rennes alone, there were 115,000 of us on the streets – well over half of the city’s population; people of all ages and from all backgrounds, all quiet and respectful throughout. We had to wait an hour from the planned start, just standing still, before the procession got moving, probably because there were apparently three times as many of us as they expected, so in the end the whole of the centre of the city was cordoned off for it – there wasn’t room for all of us on the initially planned route! I have never known such a feeling of togetherness among so many diverse people, and I don’t expect ever to feel it again. It was a moment to treasure; it makes me well up to think about it – and the feeling must have been even stronger in Paris.” ~ Abigail Grater.

12 January 2015

Chartres Cathedral Make-Work Scheme

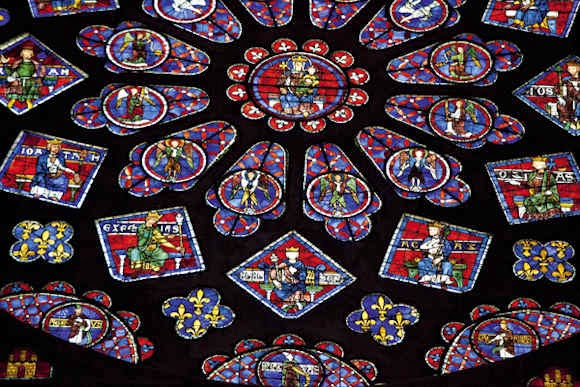

A Columbia University trained architectural historian, Martin Filler, has reported (A Scandalous Makeover at Chartres) his great shock when visiting Chartres Cathedral to discover that:

“In 2009, amid a rising wave of other refurbishments of medieval buildings, the French Ministry of Culture’s Monuments Historiques division embarked on a drastic, $18.5 million overhaul of the eight-hundred-year-old cathedral. Though little is specifically known about the church’s original appearance—despite small traces of pigment at many points throughout the interior stonework—the project’s leaders, apparently with the full support of the French state, have set out to do no less than repaint the entire interior in bright whites and garish colors that are intended to return the sanctuary to its medieval state. This sweeping program to ‘reclaim’ Chartres from its allegedly anachronistic gloom is supposed to be completed in 2017.”

Filler (correctly) notes that:

“The belief that a heavy-duty reworking can allow us see the cathedral as its makers did is not only magical thinking but also a foolhardy concept that makes authentic artifacts look fake. To cite only one obvious solecism, the artificial lighting inside the present-day cathedral—which no one has suggested removing—already makes the interiors far brighter than they were during the Middle Ages, and thus we can be sure that the painted walls look nothing like they would have before the advent of electricity.”

At Chartres, although the interior had initially been painted, Filler further notes that:

“…the exact chemical components of the medieval pigments remain unknown. The original paint is thought to have flaked off within a few generations and not been replaced, so for most of the building’s eight-century history it has not been experienced with painted surfaces. The emerging color scheme now allows a direct, and deeply disheartening, before-and-after comparison.”

Shocking though the case is it is no aberration. To the contrary, it is part of a well-established mania for the execution of aggressively radical transformations of world heritage buildings, the most dramatic of which was the notorious so-called restoration of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes in the 1980s. In his New York Review blog, Martin Filler maintains – despite all criticisms and evidence – that the restoration of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling did no harm and he declares that “in the opinion of many, myself included, the ultimate emergence of characteristically high-keyed Mannerist colors—acidulous pinks, greens, yellows, and oranges—from beneath the Sistine ceiling’s long-predominant blues and browns confirmed the project’s correctness”. (For the material and historic evidence of injuries published on this site, see Michelangelo’s disintegrating frescoes)

At St Paul’s Cathedral in London, the opposite process to that underway at Chartres was executed. Here, parts of the original painted interior applied by Sir Christopher Wren had survived and their pigments had been analyzed. It was known that Wren had applied three coats of oil paint to produce a uniformly warm not-white, not bare-stone finish. The cathedral’s present architect surveyor, Martin Stancliffe, harboured a modernist infatuation with dazzling white interiors and, accordingly, he stripped St Paul’s of the last vestiges of its original painted interior surfaces. Having done so, he then greatly increased the amount of artificial light to heighten the effects of his own historical falsification. See our accounts:

Brighter than Right, Part 1: A Modernist Makeover at St Paul’s Cathedral

Concern on the repainting of the Chartres Cathedral was first raised in the Spectator on 12 May 2012 (Restoration tragedy ~ Alasdair Palmer questions the ill-conceived makeover of Chartres cathedral which robs us of the sense of passing time that is part of its fascination and mystery). The contempt for history in Grandiose Conservation Projects is as much a constant as their high costs. Against the estimated $18.5m at Chartres the whitening at St Paul’s Cathedral (inside and out) cost £40m.

Self-evidently, major transforming restorations serve substantial vested material and professional purposes. They also take place in economic and cultural climates. The now long-running attempt to create a United States of Europe is an economically and politically failing enterprise. As manufacturing jobs flee the continent and democratically elected governments are replaced by bureaucrats, make-work schemes in the cultural sector are finding great favour as a means to stimulate compensatory economic growth. Not only do such grand and labour intensive restoration schemes make jobs for their duration, they stimulate tourism which is now one of the world’s greatest industries.

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (See the future of tourism), the UN’s World Tourism Organisation reckons that, by 2020, the number of travelling tourists will approach 1.6 billion, double the number who packed their bags this year. Those directly employed by tourism worldwide will rise from 238 million this year to 296 million, or one in every 10.8 jobs, by 2018. The USA will build 720,000 new hotel rooms over the next ten years, and a further 432,000 will be built in Asia over the same period. In this respect, we discussed the pressures to create blockbuster exhibitions and increase the velocity of borrowing and lending works of art by disregarding the known risks in two posts in 2011:

Why is the European Commission instructing museums to incur more risks by lending more art?

The European Commission’s way of moving works of art around

In 2001 we complained of the role being played by heritage bodies in stimulating tourism with recreations of long-lost historic interiors – see:

Applying recreated authenticity to historic buildings in the name of their conservation

In addition to boosting tourist revenues, another benefit of major restoration projects is that they continue to make work further work down the line. At Chartres, the interior was untreated for 800 years but its new and speculative livery will rapidly go dingy and need re-doing every twenty or so years. As we have recently seen, within twenty years at the Sistine chapel, urgent restoration measures have been carried out (in part in secret) because Michelangelo’s frescoes are physically disintegrating following the destruction-by-restoration of his final coat of secco painting. As for the resulting over-bright “restored” colours, to compensate for their already fading appearance, a new, immensely brighter artificial lighting system (with thousands of LED lights) has been installed. As the great “conservation” merry-go-round goes round, lightening, brightening, physically undermining and aesthetically falsifying, it is becoming increasingly necessary for those concerned for the integrity of our common artistic heritage to join the dots and to “follow the money”.

M. D. 15 December 2014

Above, top: Chartres Cathedral, with repainted vaulting in the choir contrasting with the existing nave and transepts in the foreground, Chartres, France, July 11, 2012

Above: The ambulatory of Chartres Cathedral, with repainted vaulting visible (right), July 11, 2012

Photographs by courtesy of Hubert Fanthomme/Getty Images. For more photographs and for treatment of statuary, see Art History News

UPDATES: 16 December 2014. The painter and former Rhodes Scholar Edmund Rucinski writes:

This even further compounds the damage done during the horrid “restoration” of the stained glass. Instead of doing the proper thing and sandwiching the original glass between protective layers of modern clear glass and re-leading the windows, the original glass was impregnated with some acrylic which filled in all the tiny irregularities that gave the original glass its famous quality.

Bear in mind that the leading naturally deteriorates and needs to be re done every so often (like replacing deteriorated stonework)…..so none (if any) of the original medieval leading is there anyway.

The result of the glass ‘restoration’ was to give the appearance of a garish plastic reproduction of the originals. This impregnation with the offending plastic may never be able to be reversed.

Fortunately, I managed to see Chartres before the vile attack on the windows. [See below]

For a grossly irresponsible and exploitative treatment of glass from Canterbury Cathedral, see How the Metropolitan Museum of Art gets hold of the world’s most precious and vulnerable treasures viz:

“An exhibition of stained glass that has been removed from “England’s historic Canterbury Cathedral” has arrived at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, after being shown at the Getty Museum in California. The show (“Radiant Light: Stained Glass from Canterbury Cathedral at the Cloisters”) is comprised of six whole windows from the clerestory of the cathedral’s choir, east transepts, and Trinity Chapel. These single monumental seated figures anticipate in their grandeur and gravity the prophets depicted by Michelangelo on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. They are the only surviving parts of an original cycle of eighty-six ancestors of Christ, once one of the most comprehensive stained-glass cycles known in art history.”

A New Threat to the Warburg Institute

It had looked in light of a recent High Court judgement as if the future of the Warburg Institute’s survival as an uniquely valuable and internationally cherished autonomous body had been secured. Big Institutions, however, can prove bad losers and capable of behaving thuggishly and, sadly, the University of London would seem to be one such.

We have received the following disturbing note from Professor Margaret McGowan, the Chair of the Warburg’s Advisory Council.

“I am writing again to keep you abreast of matters relating to the recent court judgment. The Advisory Council of the Institute met last week and agreed that an open letter should be sent to the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the University of London, Sir Richard Dearlove, inviting the University not to submit an appeal but to join the Institute in seeking mediation to agree ways to implement the terms of the judgment.

That letter was sent to Sir Richard today and a copy is attached for your information. We will also be posting a copy on the Institute website and hope that our many supporters will feel able to help us in raising the profile of our position and to encourage the Board of Trustees of the University to resolve the dispute through negotiation.

With our very warm thanks for all your support and for your continued interest in the Warburg Institute and our efforts to secure its long term future.”

The (19 November) Letter to Sir Richard Dearlove KCMG OBE, the Chair of Trustees at the University of London, reads as follows:

“Dear Sir Richard

We are writing this open letter to you in the sincere hope that we can work together to resolve the long-standing dispute with the University concerning the Warburg Institute and its trust deed.

We are sure that you and your colleagues have been as greatly touched as we have been, by the outpouring of support and affection for the Institute over the last few months. Now that judgment has been handed down in the recent litigation, the parties have an opportunity finally to end the dispute and agree a way to deal with matters in the future.

In the context of respecting the terms of the trust deed and judgment, we see no reason why we cannot settle matters once and for all, and to that end we would like to extend an invitation to you to join us in a mediation in the near future to agree ways to implement the terms of the judgment. It may not be an easy process, and there are undoubtedly strong feelings on both sides (and amongst our supporters), but if we all commit to participate in sensible, good faith discussions, we dare to believe that it can be accomplished.

In making this public approach, we are motivated by our desire to secure the long-term future of the Institute as a fully cooperative and viable unit (as defined by the trust deed) within the University of London. We are mindful of our many thousands of supporters who have openly demonstrated the esteem in which the Institute is held, not only in the UK but worldwide; we feel that the eyes of the world are on us, and on the University, at this time.

When the judgment was handed down we declared, through our press release, that we were very satisfied with its essential findings. The University’s press release made a similar declaration. That the judgment should be welcomed by both sides seemed to augur well, so far as the amicable and constructive settlement of any remaining disagreements was concerned.

And yet, at the same time, the University’s lawyers sought leave to appeal against the judgment. This development contrasts with the statement by the Vice-Chancellor of the University, quoted in the press release, which regretted that the matter had gone to court at all, and observed that ‘the financial and opportunity cost’ to the University had been ‘serious’. Similarly, in a blog article posted on the Times Higher Education website on 25 October 2014, the Chief Operating Officer of the University, Chris Cobb, noted that “Legal fees have been eye-watering, diverting valuable resources that could otherwise have been used to fund research and teaching.” We understand, from Mr Cobb’s statement, that the University uses funds for its legal costs that could otherwise be used to further the University’s primary charitable purposes in the field of education and research, and we very much regret this.

We also consider that prolonging the legal action could only exacerbate whatever damage may have been done, during the course of this dispute, to the University’s reputation. And we believe that both the Warburg Institute and the University would be harmed by subjecting both to another long period of uncertainty in these matters.

For all these reasons we very much hope that you and the Board of Trustees will decide not to exercise the right of appeal. Instead, we hope that you will agree to our proposal of mediation, and we look forward to discussing suitable mediators with you. The use of a mediator should make possible the resolution of any remaining disagreements in a constructive spirit, and certainly in a way that was less costly, less time-consuming and altogether less damaging to both sides than a return to the courts.

In the University’s press release the Vice-Chancellor was quoted as saying: “Now, we must look forward, and get back to the task of supporting this unique institute and the academic community who value it so highly.” We very much hope that the University will now act in the spirit of that very positive and encouraging statement. For our part, it is our view that the “battle” Mr Cobb referred to in his blog ought to stop, and that includes accepting the judgment and beginning to work constructively with us.

So, for the good of the Warburg Institute, the University of London, and all those worldwide who care so deeply about the Institute’s future, we hope that you will on reflection decide not to submit an appeal, but instead to accept our proposal, the underlying aim of which is to secure the Institute’s future so that it can prosper and grow under the University’s continued trusteeship.

We look forward to receiving your response at the earliest opportunity.

Yours sincerely

Professor Margaret M. McGowan

Chair, Warburg Institute Advisory Council”

20th November 2014. Michael Daley

Michelangelo’s disintegrating frescoes

As we predicted at the time of the last restoration of the Sistine chapel ceiling, by removing all of the glue-painting applied by Michelangelo to finish off and heighten the effects of his frescoes, the Vatican’s restorers exposed the bare fresco remains for the first time in their history to new dangers from the atmospheric pollution that is exacerbated by huge numbers of paying visitors.

Then, 2 million visitors entered the chapel every year. Now, that figure is 6 million.The Vatican has been carrying out secret attempts to remove disfiguring calcium deposits building up over the remains of Michelangelo’s painting. These deposits are caused when moisture given off by tourists and air-borne pollutants are absorbed by the plaster. This now-acknowledged process will also activate, as we specifically contended, the remnants of the cleaning agents (sodium and ammonia) that were washed into the frescoes during the rinse cycles of their last so-called restoration and conservation treatments. At the time, the use of the ferociously aggressive cleaning agent AB 57 was justified by the Vatican on the grounds that it was necessary to remove, among other things…ordinary solvent-resistant calcium deposits that had built up over the centuries in parts of the ceiling exposed to leaks in the roof.

Then, the Vatican promised that special air-conditioning systems would protect the newly exposed fresco surfaces in perpetuity. That system had failed even before the Vatican recently celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the end of the last restorations of Michelangelo’s paintings. Today, as the new physical threat is seen to be turning the frescoes white, the Vatican promises new, improved air conditioning units (from the same firm). To counter the new pale appearance, the Vatican recently installed thousands of LED lights, each individually attuned to heighten the colours in Michelangelo’s painting. Michelangelo’s now twice-injured painting has been left a colourised but still lucrative wreck – and an EU-funded (EUR 867 000) showcase (“This made the Vatican City’s Sistine Chapel the ideal venue for LED4ART”) for a company that shows in its advertisements that it has no idea what the Sistine Chapel looks like.

We said at the time that the restoration constituted a crime against art. Now, the Vatican promises to limit the numbers of visitors inside the chapel to 2,000 at any one time. But that means allowing a crowd as big as a full capacity audience at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London, to pack into the small chapel all day long. The Vatican’s administrators – who have known of the present problems since 2010 – now concede that the glue coatings (that were in truth Michelangelo’s own final painted adjustments) had served as a protective barrier against all air-borne pollutants. The tills will continue to ring. Art lovers remain weeping. Shame on the Vatican’s administrators.

For our previous coverage, see:

Misreading Visual Evidence ~ No 2: Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Ceiling;

The Sistine Chapel Restorations: Part I ~ Setting the Scene, Packing Them In;

The Sistine Chapel Restorations, Part II: How to Take a Michelangelo Sibyl Apart, from Top to Toes;

The Sistine Chapel Restorations, Part II – CODA: The Remarkable Responses to Our Evidence of Injuries; and Thomas Hoving’s Rant of Denial;

The Sistine Chapel Restorations, Part III: Cutting Michelangelo Down to Size;

The Twilight of a God: Virtual Reality in the Vatican;

Sistina Progress and Tate Transgressions;

ArtWatch Stock-taking and the Sistine Chapel Conservation Debacle;

Coming to Life: Frankenweenie – A Black and White Michelangelo for Our Times

11th November 2014. Michael Daley

UPDATE: 16 November 2014

While the Vatican now admits the hitherto concealed fact of the damage that is being caused to Michelangelo’s frescoes by the massive increase of tourist numbers, it remains in denial about the destruction during the last restoration of the final a secco adjustments that Michelangelo had made to those frescoes. That autograph last-stage painting – which was observed and described with perfect, detailed clarity by the painter Charles Heath Wilson in the 1881 (second) edition of his book Life and Works of Michelangelo Buonarroti – is characterised, preposterously, and against the evidence of all contemporary and subsequent copies of the Sistine ceiling, as consisting of “centuries of built-up candle wax, dirt and smoke”, as if such substances might somehow have disported themselves along the lines of Michelangelo’s design so as to reinforce his modelling and depict shadows cast by his figures. This latest apologia is carried in an Associated Press article “Sistine Chapel frescoes turning white ~ Humidity, tourists’ CO2 to blame”.

A paperback facsimile of a 1923 edition of Wilson’s milestone book (in which he describes his close examination of the ceiling on a special portable scaffold) is now available. It is time for the Vatican to acknowledge that Michelangelo had indeed finished his frescoes with secco painting, and that its curators, restorers and conservation scientists had blundered badly and inexplicably when, having judged Michelangelo’s specific, purposive pictorial enhancements and modifications to be nothing other than arbitrary accumulations of polluting material, removed it – and, thereby, exposed the lime plaster surfaces of the frescoes to their present dangers. That initial error and the subsequent falsification of art history that was made on its back, have both now been maintained for two decades.

Jonathan Jones over-heats, again

Jonathan Jones, the Guardian’s visual art blogger, has taken a second swipe at ArtWatch UK (- he was livid some years ago when leading scholars and conservators in Poland appealed to this organisation for support – An Appeal from Poland.) His viciousness then seemed bizarre – see Response to Attack.

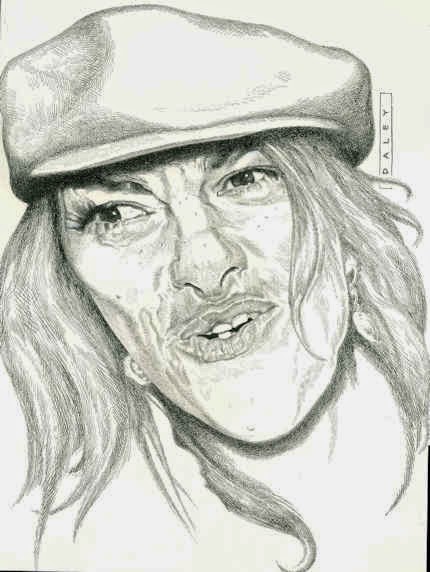

Now, we are just collateral damage, caught in his (very, very) cross wires for having been cited by one of Fleet Street’s funniest (and most trenchant) critics, Quentin Letts, who had observed in his review (“Tracey Emin’s vulgar show proves the art luvvies are dragging civilisation backwards”) of Tracey Emin’s current exhibition, that: “The art critic of The Guardian almost self-immolated, he was so hot for this show. He called it ‘eerie, poetic and beautiful’, and ‘a masterclass in how to use traditional artistic skills in the 21st century’.” That, in our view, was a fair and moderate account of Jones’s own, over-heating review: “Tracey Emin: The Last Great Adventure is You review – a lesson in how to be a real artist”. Jones may be in thrall to the talents of the Royal Academy’s former, short-lived [not current, Ed., 26 Oct.] Professor of Drawing – to the point, even, of likening her to Michelangelo. I (as an alumnus of the Royal Academy Schools, as it happens), am not and would not. Words are Jones’ currency. Drawings are mine. He talks about drawing. I do it. Each to his own? – Michael Daley

Mike Dempsey, in his blog Graphic Journey [http://mikedempsey.typepad.com/graphic_journey_blog/art/] writes:

“In the glowing, five-star review, art critic Jonathan Jones linked Emin’s understanding of drawing with that of Michelangelo. I had to read that line twice. Why?

Well, this is a drawing by Michelangelo…

And this is a drawing by Emin…

“Either Jones should have gone to Specsavers or he needs to be certified – or perhaps both. Emin’s drawing ability is frankly laughable. However, Jones went on and on to say that Emin’s drawing skills are ‘a master class in how to use traditional artistic skills in the 21st century’. He added that her nudes ‘have a real sense of observation’.

“And three more descriptions I couldn’t resist sharing: ‘Framed blue meditations on the human body’, ‘Flowing and pooling lines of gouache define form with real authority’ and ‘The rough, unfinished suggestiveness of her style evokes pain, suffering, and solitude’. I agree with the pain and suffering.

“I have loved the skill of artists who draw beautifully ever since I was a small boy. In my professional life, I have had the pleasure of commissioning very many great people. So, it was baffling for me when Emin was appointed ‘Professor’ of Drawing at the Royal Academy a few years back. Emin has said she’d never learnt to draw. But the RA still went ahead with the appointment. In a recent Guardian web chat, she said: ‘They sacked me.’ I wonder why?”

COMMENTS:

October 26th 2014 ~ The sculptor and draughtsman Michael Sandle responds:

I read Monsieur Jones’s review of Tracey’s show – I thought I’d better go to the Bermondsey White Cube and see if there was something I wasn’t getting.

There is indeed a “bat-squeak” of emotion to be felt in her work – which I suppose is positive compared to the sterility of much Contemporary “art”. But the sketches – not really drawings as I understand it – are very definitely formulaic. They are not based on “looking” and she could do them in her sleep. To compare her with Michelangelo is worse than stupid it because it shows a profound ignorance. The poor man doesn’t understand that there is something known as “High Art”. Her little bronzes are like doodles in clay – they have, I suppose, an “innocence” which, considering the effort (including anatomical dissection) that Michelangelo undertook to master his craft, means it is extraordinarily difficult to see any connection whatsoever. Her problem is, that like that of a lot of people who can’t really draw, she can’t see “shape” – if you can’t see “shape” you can’t draw, it’s as simple as that. If Jones’ comments had any truth it would mean that we are “dumbed-down” beyond hope i.e. “f*****” – which I actually think we are.

Michael Sandle, R.A.

October 27th 2014 ~ The painter and critic William Packer (and art critic of the FT from 1974 to 2004) writes:

I remember a particular moment in the life room when I was a student: the tutor looked over my shoulder and remarked that I had not drawn the feet. “No”, I said, “I wasn’t really interested in the feet.” “Hmmm”, he replied, “difficult, aren’t they”, and strolled off. I could have hit him, but of course he was right, and I’ve never forgotten, either him or the feet, since.

William Packer

October 27th 2014 ~ The painter Thomas Torak writes:

I find Tracey Emin, herself, her artistic endeavours and her sex life, profoundly uninteresting. If there were anything in her work that was worthy of criticism I would happily do so. To quote Abraham Lincoln “People who like this sort of thing will find this is the sort of thing they like.” As for Mr. Jones’s review, well, let me just say if I were to have dinner with someone who made a favourable comparison of the work of Ms. Emin to that of Michelangelo I would not let him pick the restaurant.

Thomas Torak

October 28th 2014 ~ Who wrote:

“Art criticism has become too fawning – time for a best hatchet job award?

“Jenny Saville? A heroic mediocrity. Tracey Emin? Outshone by your average newspaper cartoonist. And art critics, like their literary counterparts, should be encouraged to say so”

…and the answer is:

JONATHAN JONES, on 9 January 2013, in the Guardian.

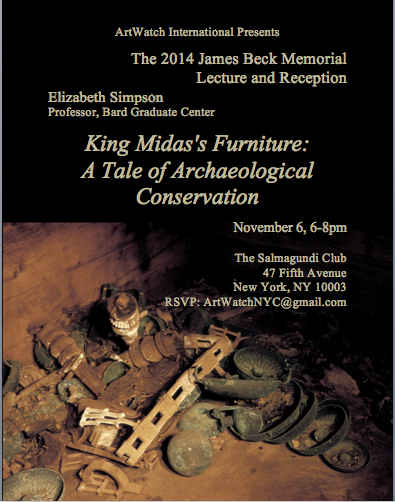

The 2014 James Beck Memorial Lecture

“King Midas’s Furniture: A Tale of Archaeological Conservation”

“We don’t need a New Michelangelo – there was nothing wrong with the old”, so said the late Professor James Beck, founder in 1992 of ArtWatch International. This year’s memorial lecture is to be given on November 6th in New York by Professor Elizabeth Simpson of the Bard Graduate Center, New York.

For more information please contact ArtWatch NYC

24th September 2014. MD