Fakes, Falsifications and Failures of Connoisseurship

2017 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of ArtWatch International and, today, the tenth anniversary of the death of its founder, Professor James Beck. This year, the eleventh anniversary of Beck’s From Duccio to Raphael: Connoisseurship in Crisis, will see the ninth annual James Beck Memorial Lecture (in London) and publication of the proceedings of the 2015 ArtWatch UK, LSE Law, and the Center for Art Law conference “Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship” – which examined the crises from the perspectives of artists, scholars, scientists, and lawyers.

During the early 1990s Michelangelo restoration battles we soon saw misattributions and restoration injuries as twinned failures of connoisseurship. Subsequent events confirmed that analysis and vindicated our warnings on toxic attributions [1]. Our recent protracted silence covered studies of the present fakes/connoisseurship malaise and the results will be published during the year.

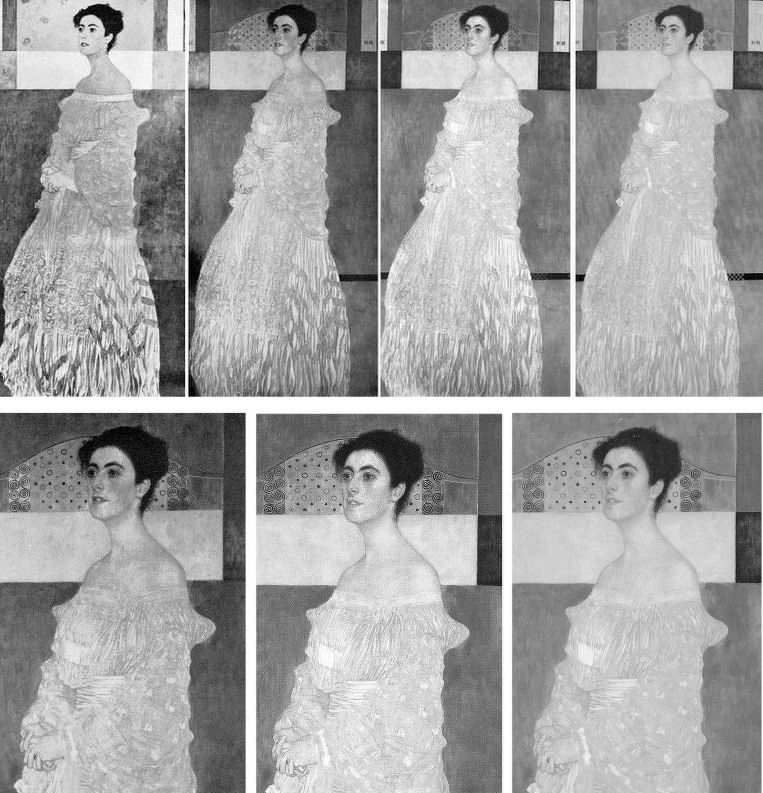

Above, Figs. 1 and 2: restoration degradations to two Klimt paintings – his Danae of 1907-08, as seen before 1956 and today; and his oil on canvas Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, as seen, left in 1905 when not-yet finished and subsequently in 1911, pre-1956 and today.

The starburst of exposed fakes that brought down New York’s (unrepentant) House of Knoedler, embarrassed ancient firms like Colnaghi’s and venerable publications like the Burlington Magazine has also humiliated the Louvre, the National Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum, the British Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Tate, the Galleria Nazionale in Parma, the Van Gogh Museum and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. On 11 April the FBI warned there could be hundreds more fakes in circulation in addition to the forty the agency has identified from a single forger who donated works to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Detroit Institute of Arts. Had the FBI prosecuted the forger Ken Perenyi there might have been as many embarrassments again [2]. The problem of fakes occurs online, on land, and at sea outside of legal jurisdictions, as Anthony Amore has shown in his 2015 compendium of scams, The Art of the Con.

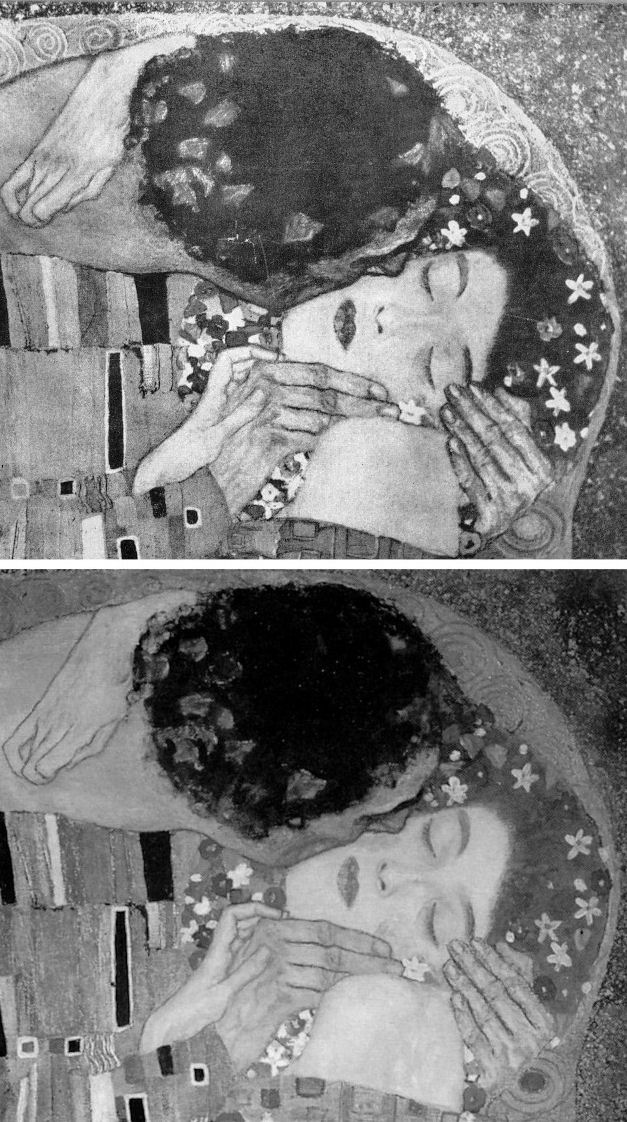

Above, Fig. 3, Klimt’s 1907-08 The Kiss, (detail) as seen before 1956 (top) and today.

With fakes and restoration injuries, the latter are greatly more destructive. Misattributions can be corrected, money can be paid back. However it might be ascribed at a given moment, the work of art – the art object – remains its own prime document (insofar as restorers permit). Sometimes restoration injuries are localised within a work, sometimes they are overall and catastrophic. Successive damaging restorations compound injuries and falsifications irreversibly (as seen above with Klimt and below with Renoir, Degas and Michelangelo). Slow cumulative damages are perhaps more serious than abrupt aberrant mistreatments that draw immediate notice. Scholars who shy from considerations of condition [3] must proceed on the premise that what is today is what originally was – an untenable view given that every restorer loves to undo and redo the works of predecessors but does so at a yet further remove from the work’s original condition and artistic milieu.

RESPONSES TO THE PRESENT ATTRIBUTIONS CRISIS

Responses to the attributions crisis have ranged from panic through self-exculpation and blame-casting to denial and cheerleading assurances of future streams of discoveries from sleeper/hunters. This is not an exclusively art market problem. Its roots are deeper and wider. The market trades objects on what others claim them to be. There has been concern among leading experts over the trade’s capacities of recognition and discrimination because of a precipitate decline in hands-on objects-informed expertise within the academic and museum spheres which have traditionally underpinned market activity [4]. Where Sotheby’s swiftly refunded purchases and took technical precautions, public museums are still flaunting restoration-wrecked pictures [5] and dubious attributions [6]. Much of art historical academia absents itself, fretting over alleged “engendered gazes”, for example, while missing (or disregarding) restoration-wrecked Renoirs and Klimts.

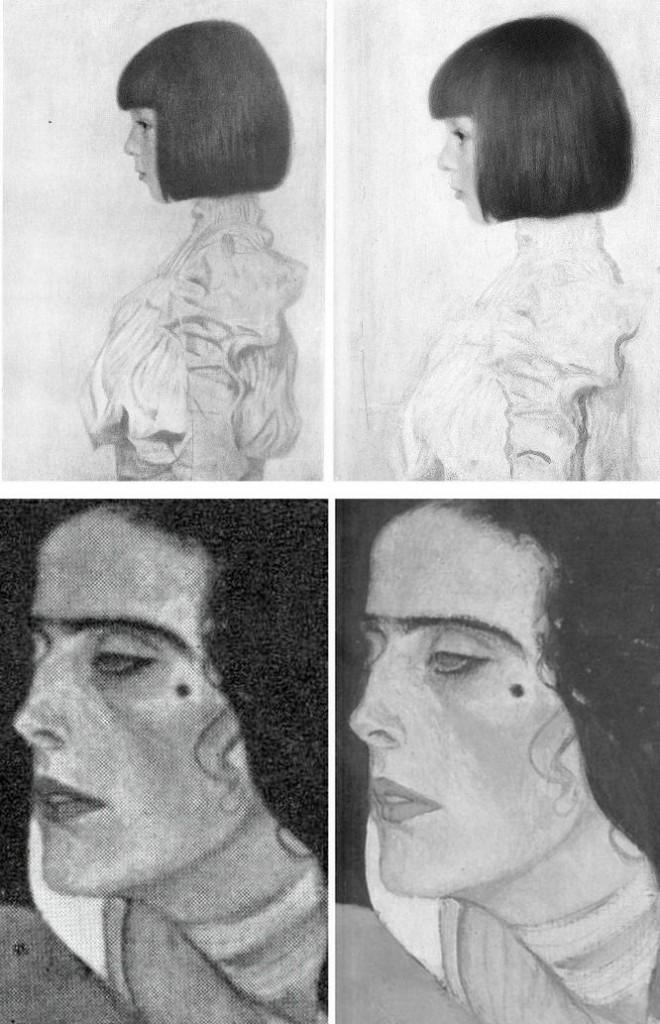

Above (top), Fig. 4, Klimt’s portrait of his niece Helene in 1956 and in 2007. Above, a detail of Klimt’s Judith II (Salome) of 1909, as published in 1956 (left) and in 1985 (Gustav Klimt ~ Women).

Below (left), Fig. 5, a detail of Renoir’s La Loge, as seen in 1921 and in the Courtauld Gallery’s 2008 exhibition catalogue Renoir at the Theatre – Looking at La Loge.

MUSHROOMING MARKETS

Without the cover of museums’ previously thought invincible technical authority, the mechanics of error are suddenly in plain view. To repeat our warnings, three years ago in “Art’s Toxic Assets and a Crisis of Connoisseurship” we wrote:

“‘Buy land’, Mark Twain advised, ‘they’re not making it anymore’. This logic ought to apply to the old masters but does not. Land makes sound investment not only because of its scarcity and its potential for development but because, in law-abiding societies, it comes fixed with legally defendable boundaries… Attributions, however, are neither guaranteed nor immutable. They are made on mixtures of professional judgement, artistic appraisal, art critical conjecture and, sometimes, wishful thinking or deceiving intent. They remain open to revision, challenge, manipulation or abuse… as some buyers later discover to their cost. Buyers are advised in the small print to beware and proceed on their own judgement… few people would dream of buying a house without legal searches and a structural survey.”

Eleven years ago we noted: “…The artists themselves may be dead but their works proliferate. As recently as the 1960s, 250 sheets of drawings were accepted as authentic Michelangelo. Today, over 600 sheets are. Such increases are fed not so much by forgery or the discovery of genuinely long-lost original works (both of which occur) but by a too-ready upgrading of copies, or studio works, to ‘original’ status.” [7.]

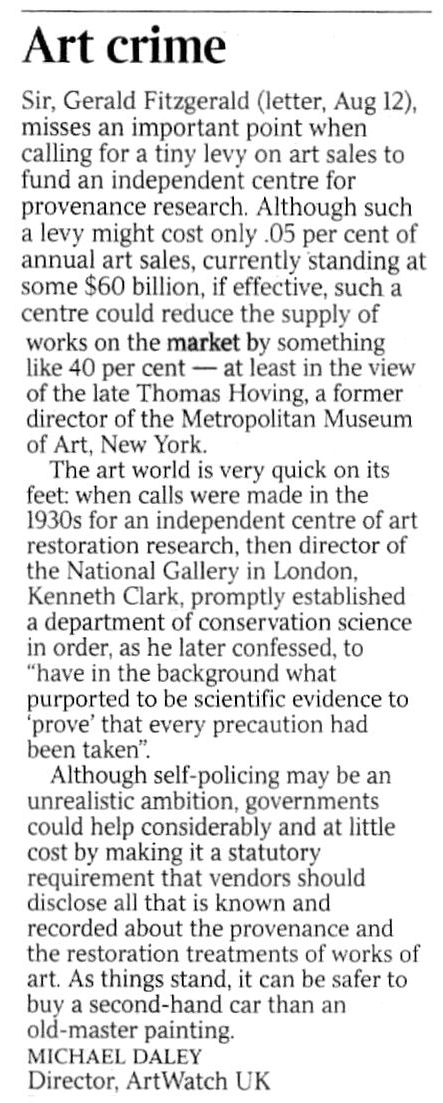

Three years ago we warned that buying old master paintings could be riskier than buying second-hand cars and asked for vendors to be required to disclose all that is known about a work’s provenance and restoration history (13 August 2014, letter, the Times – Fig.6, above). At the time we received silence. This month the art market blogger, Marion Maneker, complained (Art Market Monitor, 2 May 2017) that:

“The Financial Times has yet another ‘How Transparent Is the Art Market?’ story written by an announced participant in an upcoming art market regulation conference revealed in the pages of the Financial Times the week before. Considering the amount of interest the FT has shown in regulating the art market, one would expect the international business newspaper to have some proposals about how to police the trade.” See Georgina Adams, “How transparent is the art market”. Where Maneker complained: “The closest the story comes to offering ideas is to compare the art market to the second-hand car market (unfavorably)” Adams had quoted two art world players who so liken the art market:

“The fundamental problem, according to the FBI’s art and antiquities special agent Meredith Savona, is the lack of records of ownership. ‘Even for cars, I can see who owned it for a certain period of time,’ she says. ‘In the art market there is nothing, no regulation. If someone will not tell you who was the previous owner there’s a reason. There needs to be a way of having records maintained for, say 20 or 30 years.’ This chimes with the stand taken by Nanne Dekking, a Dutch entrepreneur whose start-up Artory aims to bring more transparency to the market through catalogue raisonnés and provenance research – ‘In Holland there is a digital registry for second-hand cars – it’s obligatory to register, so if you buy a car you know exactly what you are getting’, he says. ‘…That’s the kind of transparency we’re after.”

In 2013 Dekking was appointed Sotheby’s Executive Vice President and Vice Chairman, Americas after eleven years with Wildenstein & Co. He is a board member of the Authentication in Art group which first welcomed and then rejected a proposed paper we had offered on the flaws of Technical Art History for a forthcoming AiA conference. We see open and freely published debate as a precondition to reforming a system that is proving unfit for purpose.

PROVENANCE RESEARCH

Georgina Adams also reported calls for a levy on art sales to fund independent bodies to establish and maintain standards in the protection of buyers but such suggestions, in our view, are unworkable. The art market is global and increasingly an arena of private/secret transactions. Taxes are levied by governments. How and by whom would levies be collected around the world, pooled and then disbursed? Who would guarantee the independence of such bodies? Would they be national or international and to whom would they be answerable? Would they charge fees to offset their own costs? Less problematic, much cheaper and perhaps more to the point would be for governments to give buyers enshrined statutory rights to be informed about what should appropriately be known when buying a work of art. Presently, vendors enjoy de facto rights not to disclose their identities; not to disclose how often and to what extent works have been made over by restorers.

CONCEALMENT OF IDENTITIES

In 1998 a pastiche Leonardo drawing was put on the market by Christie’s NY as “German School, early 19th century” and “the property of a lady”. When the work was claimed to be a Leonardo worth $200million (as the so-called “La Bella Principessa”) the lady concerned disclosed her identity and brought an action for damages against the auction house on what was only a claimed valuation, not a sale. Only then did we learn that the vendor was the widow of a painter/restorer (of Leonardo, among others) who had been an intimate of Bernard Berenson, helping him to conceal his collection from the Germans during the War, and the drawing’s only known owner. When the new owner, and Professor Martin Kemp, an AiA board member and a leading advocate of the Leonardo attribution, trawled the Berenson archives together in search of an earlier reference to the drawing they drew a blank. The drawing remains without history outside of the studio of the artist/restorer who is said to have restored it. Such is precisely the kind of information to which potential buyers should rightfully be privy.

THE LAW, SECRECY AND MAKING THE BONA FIDE FAKE

When the Art Newspaper examined the legal ramifications of the current crisis (“It’s time the art market got tough on fakes” 2 February 2017) it found no appetite for either external regulation or self-policing and a blithe acknowledgement that bad restorations convert bona fide pictures into effective forgeries:

“At the annual art-crime symposium held in November at New York University, participants agreed that the culprit was the market’s notorious secrecy. But discussions revealed deep divisions about what should be done. Insurers, auction houses, dealers and other players each have their own interests to protect in a market where, as one participant remarked, the ‘level of greed…is so great’.

‘Information is the currency of the art market,’ said lawyer Steven Thomas, the head of the art law practice at the Los Angeles law firm Irell & Manella. He offered an example showing how information was withheld in trying to close a sale. When one of his clients learned that an impressionist painting he was interested in had been restored so extensively it was no longer considered authentic, he confronted the dealer, a prominent New York gallerist. ‘Oh, you found out,’ was the cavalier response. Such is the attitude in a market where the burden of due diligence as a practical matter may fall on the buyer.”

ACKNOWLEDGING RESTORATION INJURIES TO SAVE AN ATTRIBUTION – AND THE PARAMOUNT IMORTANCE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORDS

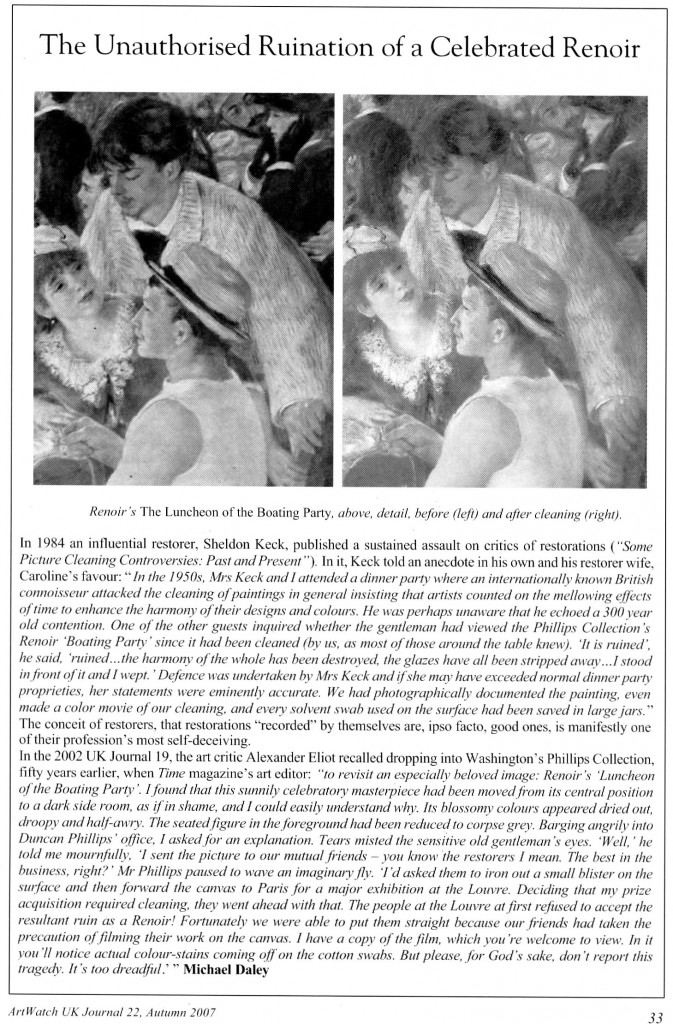

Secrecy on condition can tempt owners. Duncan Phillips privately admitted that his great Renoir The Luncheon of the Boating Party (detail below, Fig. 7) was so mauled by two pre-eminent restorers that it was rejected as authentic when loaned to the Louvre:

“Fortunately we were able to put them right because our friends had taken the precaution of filming their work on the canvas. I have a copy of the film which you’re welcome to view. In it you’ll notice actual colour stains coming off on the cotton swabs. But please, for God’s sake, don’t report this tragedy. It’s too dreadful.” [8.]

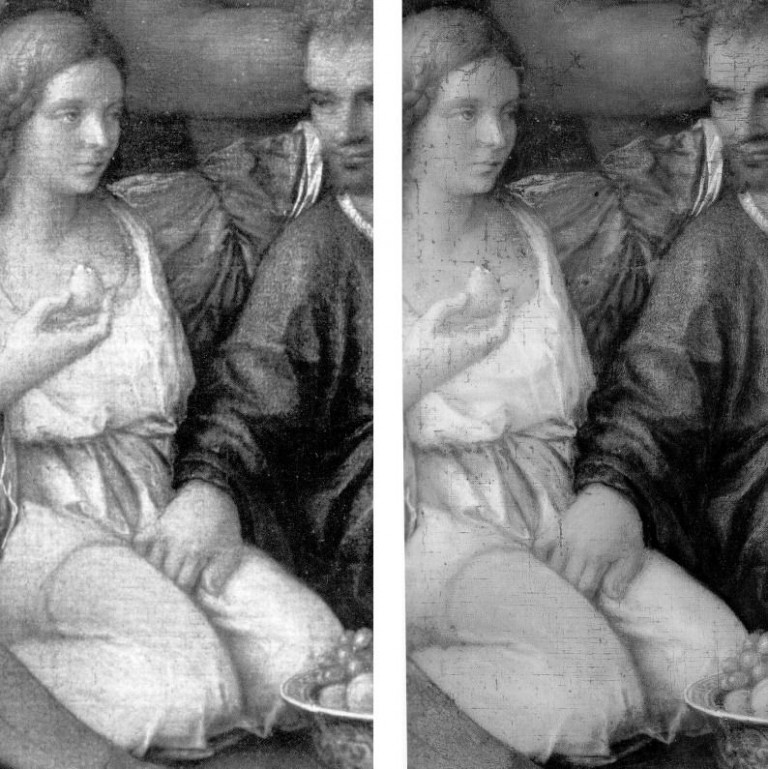

Today one can see on the painting where a colour in one part was introduced into the cracks of another area – and yet Phillips’s widow, Marjorie, wrote in her 1970 memoir Duncan Phillips and his Collection “the Sheldon Kecks, outstanding restorers, operated on the Renoir successfully!” We have asked the Phillips Collection’s director several times to see the film and the painting’s restoration records but always without reply. At the National Gallery, under the directorships of Charles Saumarez-Smith and Nicholas Penny, we were given permission to examine the historic and conservation dossiers of paintings with the kind and helpful assistance of the gallery’s librarians and archivists. In contrast, when we asked to see the records of the Bellini/Titian The Feast of the Gods at the National Gallery, Washington, the conservation department refused outright. A curatorial department was more open and supplied good-quality pre and post-restoration photographs of the painting’s states which enabled us to demonstrate losses of value during the cleaning (as at Fig. 8 below). We learn that a member of the gallery’s conservation staff keeps more sensitive photographic records at home for fear that they “might fall into the wrong hands”.

Above, Fig. 7: a page in the Autumn 2007 ArtWatch UK Journal published in memory of James Beck who died on 26 May 2007. In the same journal we published a comparison of a detail of the Feast of the Gods, as taken before cleaning (left) and after cleaning but before repainting – see Fig. 8, below:

SPURIOUS CONSERVATION SCIENCE

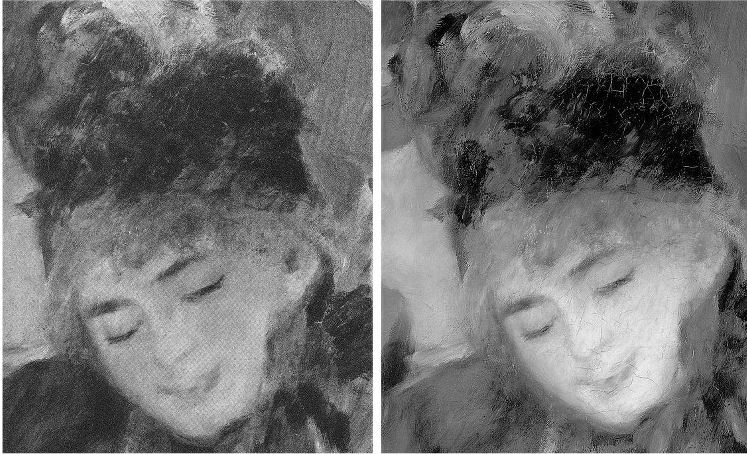

Above, top, Fig. 9: a detail from the National Gallery’s Renoir The Umbrellas before cleaning (left) and after cleaning in 1954. Below, Fig. 10, the face, after cleaning and restoring.

It should be clear to any scholar or connoisseur of paintings that the National Gallery cleaning was injurious, that the picture’s values and relationships were degraded and deranged – and yet the technical promises underpinning the restoration were “top-of-the-range” and authoritative. Cleaning was preceded by a physical and a chemical analysis of the painting by two gallery scientists who concluded that an “extremely thin” natural resin varnish could safely be removed “by solvents of a strength well below that likely to attack the paint film, which is resistant to the solvent action of pure acetone.” The scientists offered an additional assurance: “In the hands of a competent restorer [Norman Brommelle, husband of the National Gallery’s head of science, Joyce Plesters, was chosen] there is no reason to fear that the paint layers will be disturbed in the course of cleaning. Since, in this particular picture, there is no evidence of a linoxyn film, nor the presence of any resin in the medium, there is, in our opinion, no need to adopt any special precaution.”

Brommelle reported that the varnish was removed with a 3:1 turpentine/acetone mixture containing a small percentage of diacetone alcohol and that the last traces were removed with toluene but no one explained why an extremely thin varnish layer of no great antiquity needed to be removed. The cracks seen above at Fig. 10 were products of the cleaning (some local cracking had occurred previously where the canvas vibrated against a central stretcher bar on its regular exchanges between London and Dublin. (Technical information by courtesy of the National Gallery Conservation Department.)

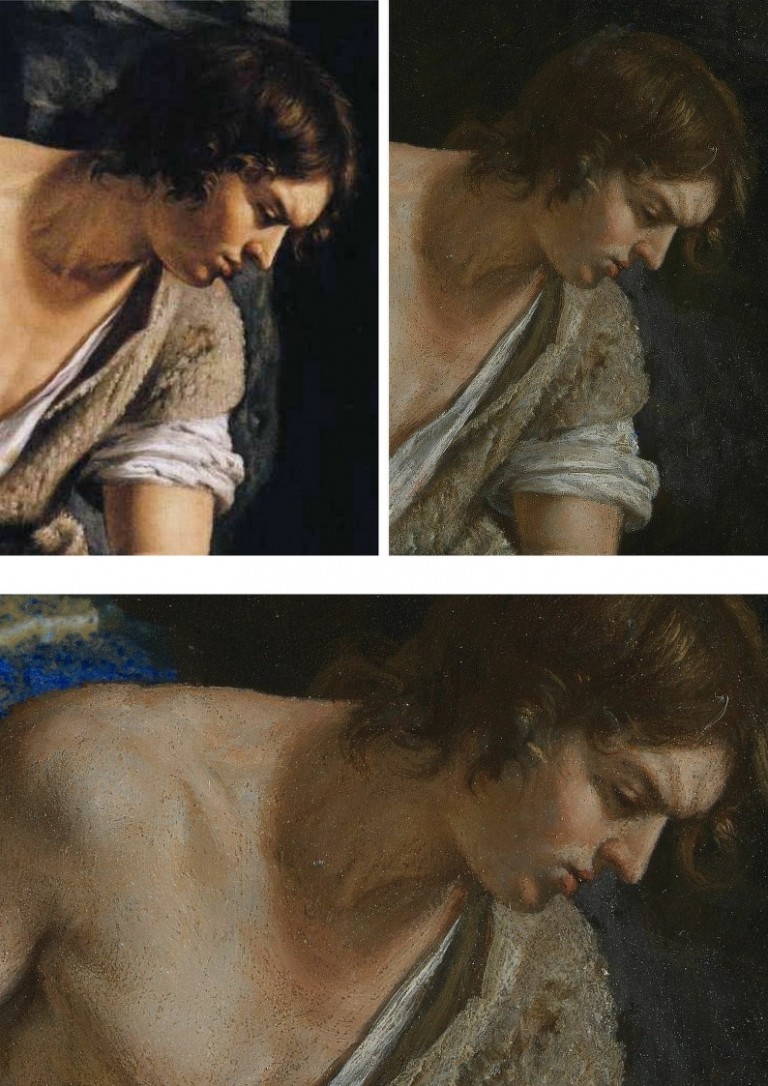

THE TECHNICAL AND SCHOLARLY UNDERWRITING OF A FAKE AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY

One of the recently disclosed fakes, an “Orazio Gentileschi” (above right at Fig. 11 next to an authentic work), had been accepted by the National Gallery on a loan from its owner. When the now rejected no-history painting was withdrawn, the gallery justified its inclusion with the claim (Antiques Trade Gazette): “The gallery always undertakes due diligence research on a work coming on loan as well as a technical examination.” After this historical and technical examination, the Gallery label declared that “the poetic depiction of ‘David Contemplating the Head of Goliath’” had been produced by Gentileschi “for a collector’s cabinet” – an unsupported claim that, like “made for private devotion”, often serves as a flag of convenience for small recently-discovered old works without histories.

Above, Fig. 12, here we see a detail (top left) of the real Gentileschi David and (top right and below) the loan accepted as authentic by the National Gallery. If, instead of whatever technical and art historical examinations were carried out, the Gallery had run a few simple photo-comparative checks of the kind shown here, it should have been obvious to anyone with an alert eye that the picture in the top left had been the bona fide historical prototype for the other, markedly inferior and modern-looking, version. Qualitatively, they are not remotely co-equals: the one is a crude pastiche of the other. In every detail the chasm of quality should have identified the loan as a pastiche.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF (UNACKNOWLEDGED) RESTORATION INJURIES

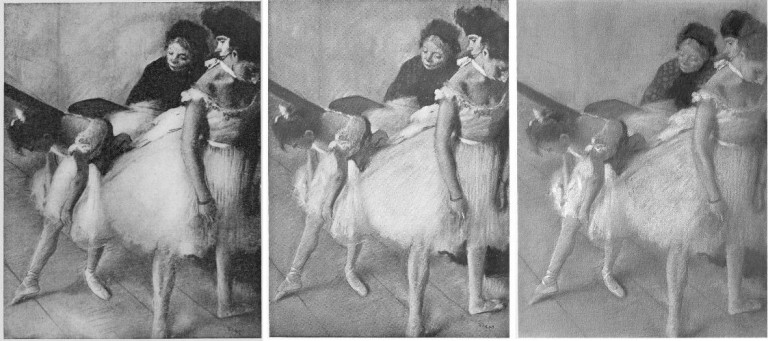

Although this impostor has now been rejected from the National Gallery there is no redress for individual badly restored bona fide works – and often not even an acknowledgement of their plight. Nor is there any apparent means of stemming the swelling tide of destruction that masquerades as a conservation service while delivering incremental degradations of pictures, such as those that can be shown to have taken place in less than a century on what is now the Denver Art Museum’s Degas’ superb pastel and charcoal The Dancing Class or Dance Examination of 1880 below at Fig. 13. The first photograph in the sequence was published in 1918 (Degas, Paul Lafond) when the drawing was not yet forty and therefore likely to have been in an original or near-original state. The third photograph was published in 2002 in the catalogue to Degas and the Dance, a sponsored travelling exhibition organised by the American Federation of Arts (- the “the prime movers”), the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The show was curated by the leading Degas specialists Richard Kendall and Jill Devonyar.

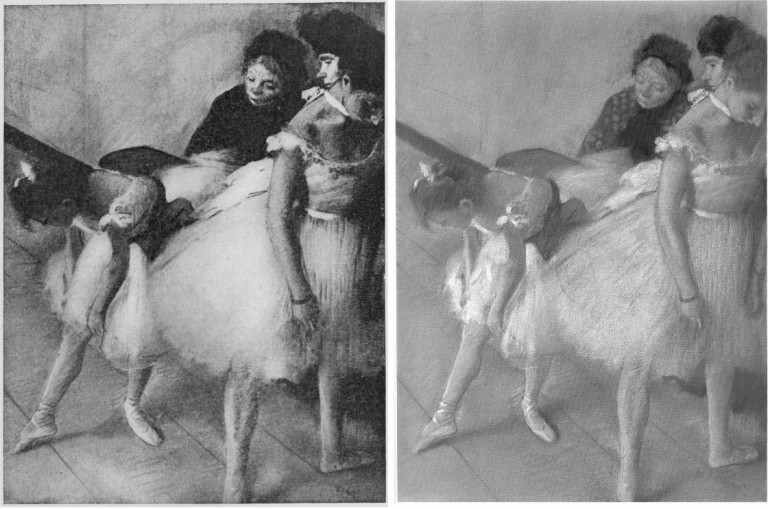

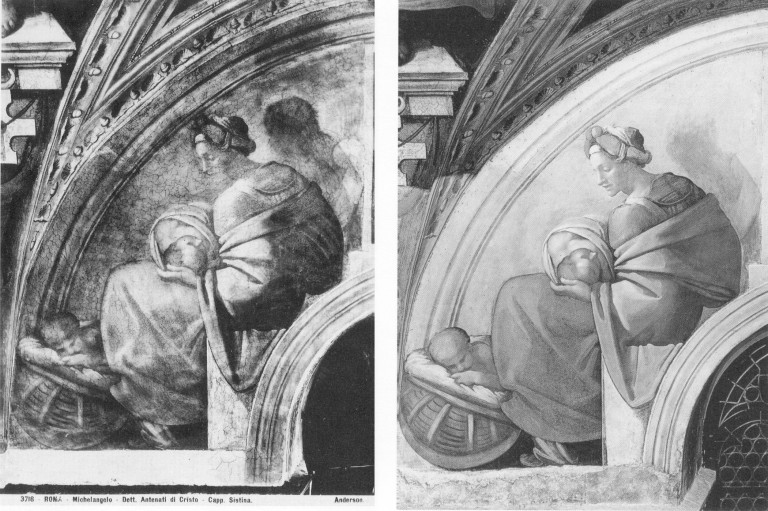

The sequence of states at Fig. 13 above resembles a succession of an etching’s proof states in reverse: the most complete condition is seen in the oldest record and the most debilitated state is recorded most recently. If we make the most direct comparison with the earliest and the most recent records of this drawing, as at Fig. 14 below, the differences become startling and heartbreaking. What happens to one artist happens to all in turn, as was most shamefully seen to Michelangelo at the Sistine Chapel – see Fig. 15 where an early Anderson photograph of a lunette is shown with its post-restoration state. By such simple comparative means we can see/demonstrate that Degas and Michelangelo have not been restored or conserved so much as subjected to a cultural pathology – an infantile revulsion at or terror of darkness and a failure to appreciate that darkness, as artists appreciate, confers brilliance and radiance. Without shadows to relieve lights there is no great vivacity – art’s life-affirming gift. Our historic cultural legacy is being made over into a blander, more homogenised arbitrary colourfulness. With so much value and vivacity already lost in the Dance Class’s first century, who, if offered the chance, would today vote for “More of the same, please” in the next? Restorers can never put the clock back. They can only offer more of the same: yet further intensifications of hue and losses of form and space-creating tones.

THE INCALCULABLY VALUABLE TESTIMONY OF PHOTOGRAPHS

Photographic reproductions do not have to be taken as absolutely faithful replications to have great value as record – why else would they be published and consulted in such great numbers? They are particularly eloquent as witnesses when seen in company with predecessors and successors, because the patterns that successive images make disclose the truth about present conditions. The net consequence of restorations during the last much-photographed century can be seen/shown to have been gravely damaging, effectively washing away art’s pictorial strength, disrupting the internal relationships of individual works, rendering oeuvres capriciously erratic and incoherent and, thereby, creating spaces, opportunities and, even, seeming precedents for misattributions and outright fabrications.

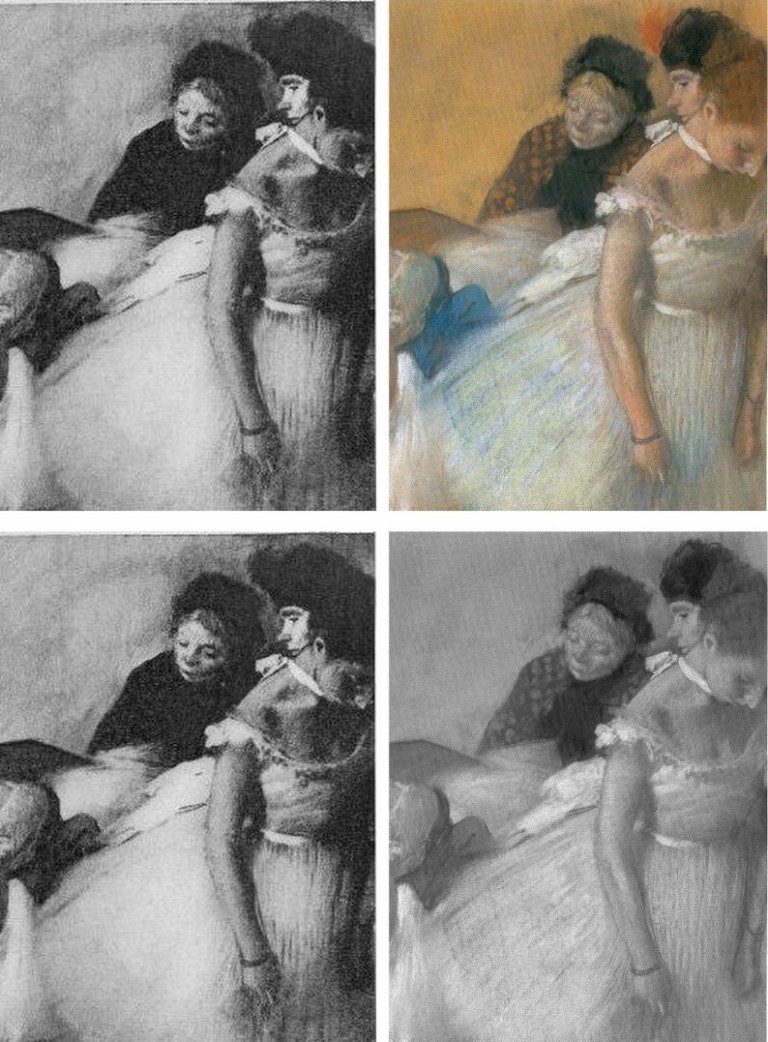

COLOURS V TONES

Although we do not have a colour photograph to match the black and white Durand Ruel photograph published in 1918, we can, by juxtapositions, estimate the degrees of loss today. At Fig. 16 below, the top comparison shows that the bump on the head of the woman in the upper right-hand corner was formerly a red feathery hat decoration. It now survives as a smear of colour that, tonally, is almost indistinguishable from the wall behind. We can see in the greyscale comparison at the bottom that the red decoration had originally been given a halo. On his own declared pictorial statagems, we might deduce that Degas had used the pocket of red to create a triad of local counterpointing primary colours: red feathers, ochre spots and an intense dark blue ribbon bow. Certainly, speculations aside, since that date the ineffably soft back of the standing dancer’s tutu has both hardened and become see-through. The feathered, layered back of the bending dancer’s tutu has, on some bizarre and alien tidy-minded logic, been reduced a ghostly but sharp-edged right angle. Degas is leaving us, involuntarily. He learnt and extracted much from photography. Is it too much to ask that all scholars use our very great resources of photography and historic photographic evidence to calibrate the injuries done to his oeuvre and therefore more fully appreciate and give due account of Degas’ great and supremely fresh and audacious genius?

Certainly, the most urgent single reform needed in today’s crisis of connoisseurship lies in increasing the accessibility of photographic records of condition and treatments. In an age of electronically transmissible, high quality photographic images this would be easier to achieve and more instructive than ever before. There are no good reasons for institutions, owners and dealers continuing to sit on such material and thereby prevent people from seeing what’s what.

Michael Daley, 26 May 2017

Coming next: Degrading Degas and Michelangelo

ENDNOTES:

[1] We first used the term in connection with the so-called Stoclet Madonna, the Metropolitan Museum’s attributed Duccio, in “Toxic Attributions?” The Jackdaw March/April 2009.

[2] “In the end, after a five-year investigation and a mountain of evidence collected, no one, neither the two ‘conspirators’ nor I, was ever charged with a crime or indicted” – so wrote Ken Perenyi, in his 2012 memoir Caveat Emptor, p. 312.

[3] One scholar who has engaged on this territory with his pioneering book Condition:The Ageing of Art, Paul Taylor, incurred immediate wrath from some restorers who would claim monopoly rights on all discussions in the field, but a firm welcome elsewhere. Apollo noted that “There are unquestionably many art critics and even academic art historians for whom the material context of art, and particularly flat art, has become a rarefied field. That needs to change, if we are not to see total severance between those who work to preserve physical objects and those who claim to construe their meanings.”

[4] In a paper delivered at the ArtWatch UK/LSE/Centre for Art Law December 2015 conference (“Throwing the baby out with the bathwater”), Brian Allen, a former director of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (1992 to 2012) and Chairman of the Art Fund observed: “…increasingly, the only young connoisseurs emerging are to be found in the commercial art trade and this surely cannot be a desirable state of affairs. It might be argued that many of the best ‘eyes’ have always been in the art trade but, until recently, there was always a body of disinterested academic ‘experts’ to counterbalance commercial self-interest…” In the March 2017 Art Newspaper, Anna Somers Cocks, the paper’s Chairman and a former curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, discloses that the V&A now considers the giving of opinions a drag on its curators’ time and devotes only three hours a month to it when, in the 1990s, it reserved two afternoons a week to telling the public what their heirlooms were. In the same issue of the Art Newspaper Mark Jones, a former director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, said that expertise, by which he meant “the ability to recognise and identify objects, surmise their history from their appearance, tell the genuine from the false and make judgements about quality” has become patchy, even rare, in museums. Mark Jones was the curator/organiser of the British Museum’s legendary 1990 exhibition “Fake? The Art of Deception”, the catalogue of which remains a seminal study in the field.

In response to Mark Jones the dealer Peter Nahum wrote in the April 2017 Art Newspaper (letter, “Dealers and curators should work together to spot fakes”):

“The art forger Shaun Greenhalgh and his father George visited my gallery in 1984. It was after 6pm and they offered me a painting they said was by Samuel John Peploe, for which I gave them a cheque. As soon as the banks opened at 9am the next morning I cancelled the cheque and called in the police. I was the first to report the family from Bolton for purveying a fake, 16 years before their arrest.

“When they were finally arrested, my cheque was still on their desk. I also advised Bolton Museum on the purchase of the painting by Thomas Moran and subsequently saved them from buying a fake watercolour purportedly by the same artist.

“I have long campaigned for the art and antiques trade and academics, especially those in museums, to work more closely together. Our job, as dealers, is to defend our clients against the legion of fakes and wrongly catalogued items on the market. As we are personally financially responsible for all transactions we make and advise on, we are the most vulnerable and, by necessity, the most careful. As a result we are often best placed to authenticate works.

“Academies and museums obviously have great experts on their staffs, but their prime focus is the history and provenance of objects and thus their visual skills often take a secondary position. When both professions work together, mistakes are lessened.

“I have made it my mission to track down and report those who make fake art, as they are the bane of our lives and can cost those who buy art a great deal of money. They are simply con-men extracting money from innocent people by deceit.

“As dealers, academics and collectors, we are all motivated to push the boundaries of our knowledge, and thus all of us are vulnerable to those who wish to take money under false pretences. We have to be constantly on our guard as each one of us will fall into one of the fakers’ traps sooner or later – we are all human after all.

“Thus, I applaud Mark Jones’s article: scholarly research is flourishing but curators’ ability to judge an object’s quality is not (The Art Newspaper Review, March, p.13) with two main comments. The painting by Samuel John Peploe was not sold, and academics have rarely been the greatest visual judges – that is more our job than theirs. That does not mean that there are not great visual experts in academia – of course there are – it simply means it has never been their primary function.

Peter Nahum.

Peter and Renate Nahum Agency (the Leicester Galleries), London.”

[5] See “From Veronese to Turner, Celebrating Restoration-Wrecked Pictures” and “Taking Renoir, Sterling and Francine Clark to the Cleaners” and THE ELEPHANT IN KLIMT’S ROOM and, finally, “Now let’s murder Klimt”.

[6] The National Gallery includes one of its most dubious and controversial attributions – the Rubens Samson and Delilah – in its list of 30 “must-see” pictures. There are more than twenty secure and superior works by Rubens in the gallery including the magnificent Minerva protects Pax from Mars (‘Peace and War’). When controversy broke over the attribution in 1997 the gallery’s director, Neil MacGregor, placed a statement next to the painting to explain why it looked like no other Rubens in the collection. Two special issues of the ArtWatch UK Journal have been devoted to this picture’s problems. See: “The Samson and Delilah ink sketch – cutting Rubens to the quick” and “Art’s Toxic Assets”

The National Gallery’s highlights list also includes the restoration-wrecked Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian, on which, see: “The Battle of Borja: Cecilia Giménez, Restoration Monkeys, Paediatricians, Titian and Great Women Conservators”

[7] “Oh Blessed Honthorst”, Michael Daley, ArtWatch UK Journal No. 21 Spring 2006 – a Rubens special issue dedicated to the National Gallery’s ascribed Rubens Samson and Delilah), p.4.

[8] As reported by Alexander Eliot, a former Time magazine art critic, in “A Conversation about Conservation”, The World and I (Volume: 15), June 2000.

Leave a Reply