Defending the Indefensible Part I: The National Gallery’s Tangled Rubens Web

1) “I know gossip about staff and trustees and stories connected with acquisitions I don’t think I’d better share.”

– Martin Wyld, the National Gallery’s retiring Head of Restoration in the January 2010 Museums Journal.

2) “Rubens’ Samson and Delilah is a large scale, early and entirely autograph painting of a kind the National Gallery previously lacked.”

– Michael Levey, the then-Director of the National Gallery, in the 1983 Rubens Acquisition in Focus exhibition catalogue.

3) “The Samson and Delilah was planed down to a thickness of about three millimetres and set into a new blockboard panel before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 and so no trace of a panel maker’s mark can be found.”

– Christopher Brown, the National Gallery Senior Curator, Flemish Paintings, in his 1996-97 Esso-sponsored National Gallery “Making and Meaning” exhibition catalogue Rubens’s Landscapes“. (Emphasis added.)

4) “Rubens’ panels sometimes bear the branded or carved mark of the panel maker, an example in the National Gallery being the Portrait of Susanna Lunden… unfortunately, as David Bomford has described, the back of the panel of the Samson and Delilah had been planed-down to a thickness of only about 3 mm and then the whole set into [sic] blockboard before the picture was acquired by the National Gallery, so any such marks would have been eradicated.”

– Joyce Plesters, the then-Head of Science, in the 1983 National Gallery Technical Bulletin. (Emphases added.)

5) “The treatment of Cima’s Altarpiece carried out during the 1970s and 1980’s was a rare modern example of a process that was extensively practised (often unnecessarily) in the 18th and 19th centuries – the transfer of a painting to a new support. It is nowadays only carried out in the last resort, when all other attempts at treatment have proved unsuccessful.”

– David Bomford, National Gallery conservator and author, in his 1997 National Gallery Pocket Guide: Conservation of Paintings. (Emphasis added.)

6) “Questions have been raised about aspects of the physical state of Rubens’s Samson and Delilah since its purchase by the National Gallery at auction in 1980… Recent research, however, has yielded some answers to the questions of when and why the painting may have gained this alien backing.”

– David Jaffé Christopher Brown’s successor at the National Gallery, August 2000, Apollo ‘Rubens back and front’. (Emphasis added.)

FROM THE FIRST CRITIC:

7) “Jan Bosselaers had inspected NG6461 up-close in 1977, and then again in 1980. Given his familiarity with the painting, I asked him specifically about its back. Bosselaers grabbed a piece of paper and drew a grid of three vertical lines crossed by three horizontal ones. He looked at me. ‘A cradle!’ I gasped. ‘Yes’, he said, ‘it was a cradle.’”

– Euphrosyne Doxiadis: Painter/author, in her NG6461 The Fake National Gallery Rubens (p. 117. Emphasis added.)

MICHAEL DALEY WRITES:

PART I: A REFORMULATED SAMSON AND DELILAH ACCOUNT THAT STILL DOES NOT STACK UP

With expensive and massively hyped works bought by major public institutions it would seem that acknowledging errors is an art-political impossibility. Such institutional obduracy is longstanding. In 1966 the art dealer René Gimpel noted that “The museums are even more intent than the collectors on defending their fakes or their mistaken attributions” (- a 1929 entry in his Diary of an Art Dealer.) Today, with the Samson and Delilah, the National Gallery stands in triple jeopardy: its initial error of art historical judgement has been compounded by both an apparent falsification of material evidence and a decades-long withholding of contra-testimony in its possession.

The affair began in 1980 with a deceptive unanimity of assurances and a dearth of disclosures. Today, on interrogation of the picture’s traits, provenance and technical literature, a sleight of hand emerges: the back of its panel and the historical evidence it bore were removed by the Gallery and not by earlier, unknown others, as the Gallery has claimed since 1983 – and blatantly claimed despite its possession of flatly contrary key historic documents. (See Fig. 5 below.)

Thus, there are two cross-linked issues: whether the picture is the long-lost original Rubens painting of 1609-10; and, who planed down the back of its panel and mounted it on a larger sheet of modern blockboard (- and with it, of course, “Why?”). The first is a matter of judgement. The second is one of fact that should also be – but conspicuously is not – one of record. Dr David Jaffé’s August 2000 bid in Apollo (see below) to explain why the panel painting “might have” received its alien backing before being bought by the National Gallery was doomed by his failure to follow such records as exist within the Gallery and extrapolate from them the precise place and time at which the transformation had occurred.

On matters of fact, at Fig. 2 below, we note an item on the National Gallery’s recently updated online Samson and Delilah entry which itself supplies visual confirmation of past institutional culpability.

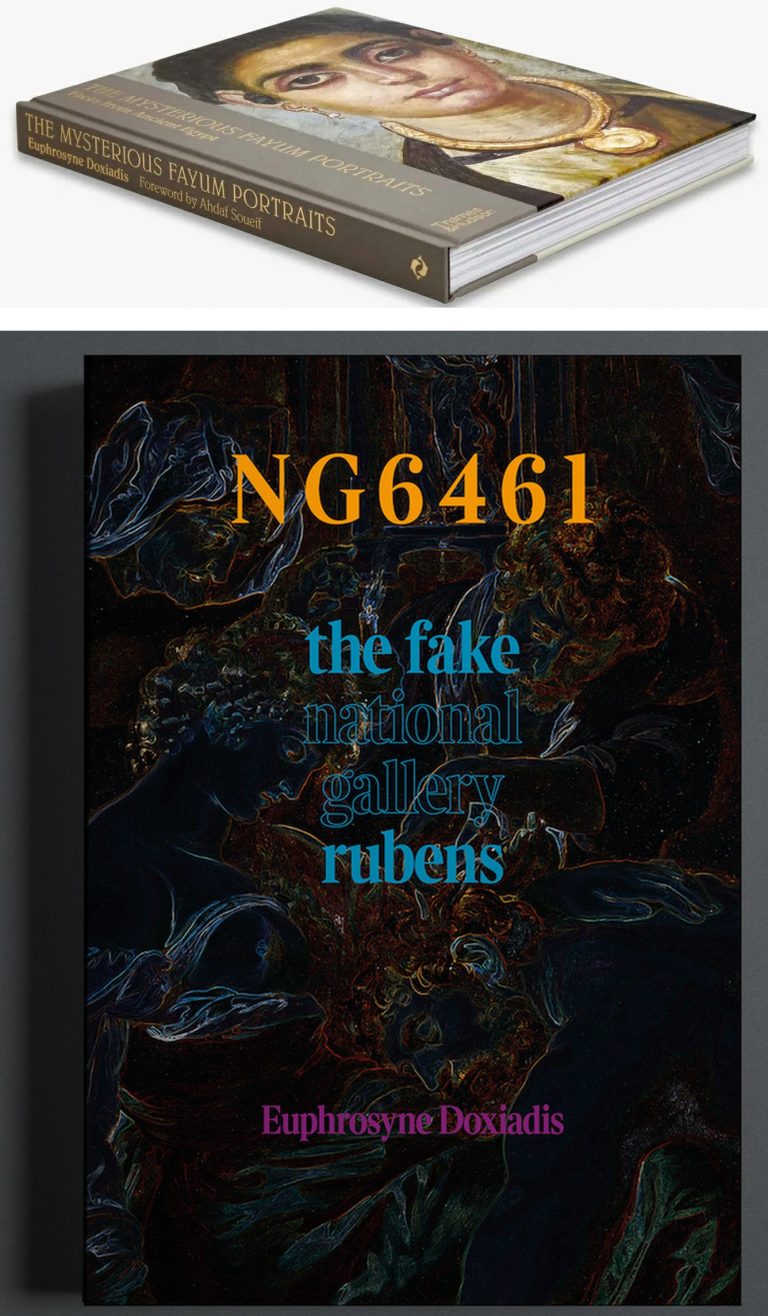

Above, Fig. 1: top, Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s (republished) award-winning 1995 study of the Fayum encaustic paintings; above, Doxiadis’s new book NG 6461 The Fake National Gallery Rubens – N.B. “NG6461” is the Gallery’s inventory number for its supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah.

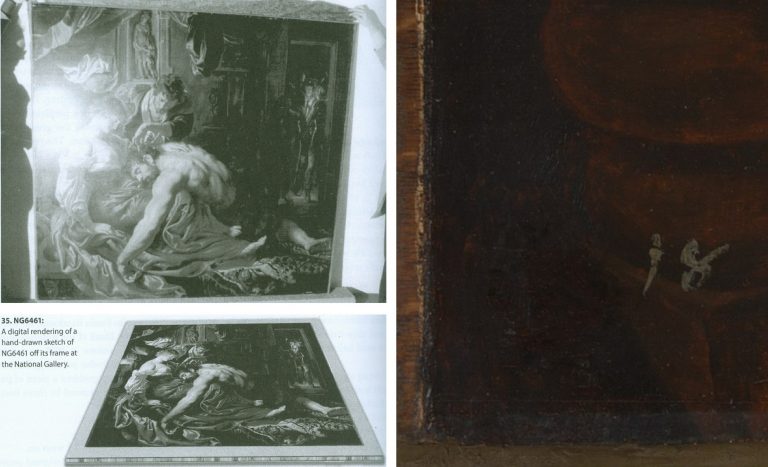

Above, Fig. 2: Top, left, The National Gallery Samson and Delilah, as seen in Antwerp in 1980 when it was about to be dispatched to Christie’s, London, and at which date the paint reached the top and bottom edges of its panel but not the side edges (to which slim battens had been attached – on which, see comment by Martin Wyld below). Above, left, Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s digital rendering of the Samson and Delilah panel on its blockboard mount, as seen by her when the picture was undergoing dendrochronological examination at the National Gallery on 25 September 1996. (Both images above are published in Doxiadis’s NG6461 The Fake National Gallery Rubens.)

Above, right, the bottom left corner of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah in which the picture’s post-1980 blockboard backing can now be seen running below the bottom of the painting. The Gallery’s online publication of this image’s visual corroboration of the panel’s post-1980 blockboard extension is intriguing. Wittingly or unwittingly it constitutes a tacit acknowledgement of institutional responsibility for the Gallery’s own (always previously denied) planing down of the panel and subsequent mounting of it on a larger blockboard sheet. (See Figs. 3 and 4 below.)

The Gallery’s online entry acknowledges – somewhat disparagingly – the existence of the Samson and Delilah picture’s “Naysayers” and cites some of their/our publications. Unfortunately, although it cites both issues of our Journal that were dedicated to the Samson and Delilah’s problems (see Fig. 7 below) it does not address their contents – as might be instanced in this pertinent item on the “Material Evidence” section in our Autumn 2000 Journal:

“…This conflict of testimony echoes one found within the Gallery in 1983 when the restorer David Bomford described the thinned panel as glued ‘onto’ the face of the blockboard while the Head of Science, Joyce Plesters, described it as ‘set into’ the blockboard. When I drew this discrepancy to [the then-Director] Neil MacGregor’s attention, he replied (letter 19th June 1997): ‘Incidentally, at the risk of being pedantic, into is the correct preposition, since the edges of the blockboard are flush with the [edge] surface of the panel. Onto would be correct if the panel had simply been glued to the blockboard and protruded above it.’ If this account is accurate, with the edges of the panel and blockboard being flush, there would be no place for the putty bevel encountered by Ms Doxiadis and Mr Norman [*1]. By the same token, had the edges of the panel and blockboard been flush, there could have been no grounds for Joyce Plesters’ 1983 [Technical Bulletin] claim that the treatment had ‘render[ed] the edges of the panel inaccessible’ for dendrochronological examination. A clear, focussed photograph of one of the picture’s corners might throw some light on the subject. Or better yet, permission to examine the panel in the flesh…”

(Emphasis added. Permission to examine the panel was never granted.)

On 14 February 2006, when examining the Samson and Delilah’s dossiers for a second time [*2], we noted photographs showing that the paintwork stopped short of the edges of the oak panel only on the vertical edges. In the present revised online Gallery entry, confirmation and possible explanation for this feature is given: “There is a narrow margin of unpainted wood at the sides of the oak panel which probably results from the support being held firm by grooved battens while the ground and then paint were applied; ‘6’ the ground and paint extend to the top and bottom edges.” The footnote ‘6’ reads: “The same can be seen on Rubens’s Judgement of Paris (NG6379). For this practice see, for example, Wadum 1998. The battens seem often to have been only along the shortest sides. A little of the unpainted margins may have been trimmed away since they are rather narrow.” With the Gallery’s Samson and Delilah, the photographic and documentary records of the restoration treatments are strikingly less complete than those of other Gallery panel paintings. For example, when writing on the restoration of the Altdorfer panel bought in 1980, Martin Wyld discusses the attachment of battens to the edges of panels: “Although some German panels of this period have channels at or near the end grain of the plank in order to accommodate battens which were fixed to the frames, the channels are seldom to be found on all four sides”.

[*1] Charles Norman, Director, The National Timber Trade Federation. As Dalya Alberge reported (The Times, 27 August 1997) on photographs supplied to us by Mr MacGregor, Mr Norman judged the back of the Samson and Delilah to be “a blockboard manufactured in the late 1970s or early 1980s”. It looked, he said, “like a manufactured item, machine-made rather than handmade”. Later, after being invited to see the picture at the National Gallery, Mr Norman amended his earlier observations. His subsequent description of the picture’s physical component parts (made by telephone, 18 & 19 September 1997 to Michael Daley) was a compromise between his original observation and Euphrosyne Doxiadis’ (above-illustrated) clear recollection of a substantial surround between the edges of the planed down panel and the blockboard support, and Mr MacGregor’s claim of flush panel and blockboard edges. That is, Mr Norman claimed that the blockboard was somewhat larger than the planed down panel but that the gap between the two had been filled by a wide putty bevel.

[*2] In 2006, under Charles Saumarez Smith’s directorship, we were given full access to the Collection’s photographic and documentary records – a privilege subsequently extended by Nicholas Penny and Gabriele Finaldi. (ArtWatch is greatly indebted to all three knights – as also to the Gallery’s kindly helpful archival and library staffs.)

With the Gallery’s present publication of the Fig. 2 photograph of the bottom left corner of the Samson and Delilah, two points should be noted. First, the Gallery’s 1997 claimed relationship between the panel and its blockboard backing was clearly unfounded. Second, the photograph of the bottom left corner is cropped and therefore does not show the full blockboard extension. Nonetheless, it does now show (MacGregor’s earlier claims notwithstanding) that, far from the edges of the panel and blockboard being flush, the latter can be seen to protrude beyond the bottom edge of the picture when, as seen above at Fig. 2, top left, it had not done so in 1980 when held by the banker, Jan Bosselaers, in Antwerp, shortly before it was sent to Christie’s. Today’s publication of that photographically-confirmed relationship has finally demonstrated that the blockboard backing must have been applied to the picture’s panel after 1980 and when in London.

CONFLICTED AND OPAQUE GALLERY ACCOUNTS – AND THE FIRST PUBLISHED APPEARANCE OF THE BLOCKBOARD BACKING

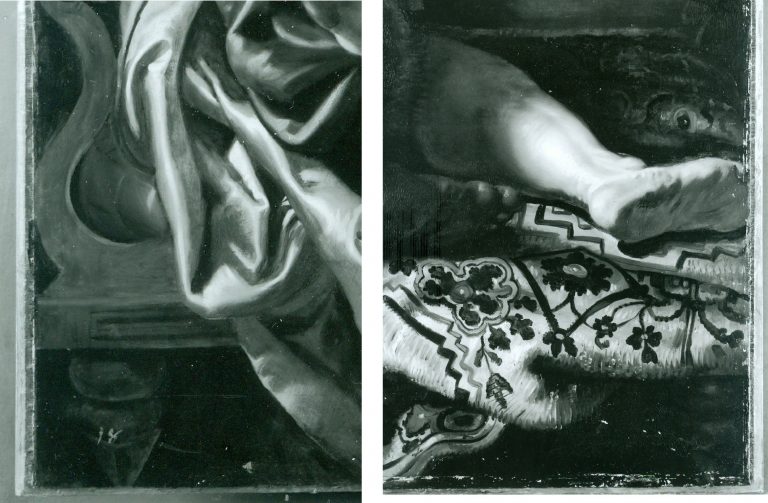

Above, Fig. 3: left, the National Gallery’s recently published online detail of the bottom left corner of the Samson and Delilah; right, a detail of the bottom left corner the Samson and Delilah in a National Gallery photograph taken on 10 August 1982 and designated: “After Cleaning, Before Restoration”.

Above, right, this – so far as we know – unpublished 10 August 1982 photograph, shows the then-present blockboard backing that protrudes not only beyond the bottom edge of the panel but also beyond its left vertical edge (which is not disclosed by the cropped image presently shown online). The date on the black and white photograph shows that the picture had then been in the Gallery’s possession for twenty-five months by which time the planing and mounting on blockboard had occurred (as had also the removal of the picture’s varnish, as shown below.) What the Gallery has never produced – and, we believe, could not ever produce – is a photograph showing the blockboard’s presence before the picture was acquired from Christie’s or when it had been loaned by Christie’s to the National Gallery ahead of the sale. In the absence of such important photographic testimony, the conclusion that the National Gallery itself planed down the panel for undisclosed reasons and mounted it onto a blockboard sheet, is inescapable. The formal authorisation for the picture’s restoration from the Board of Trustees came on May 16 1982 just three months before the above-right photograph was taken. Thus, on the available official records, the removal of the Samson and Delilah panel’s back and the subsequent mounting of it on blockboard had occurred at the National Gallery between 16 May and 10 August 1982. (It is not inconceivable, however, that the formal application for permission to restore the picture had in fact followed a commencement of work on it.)

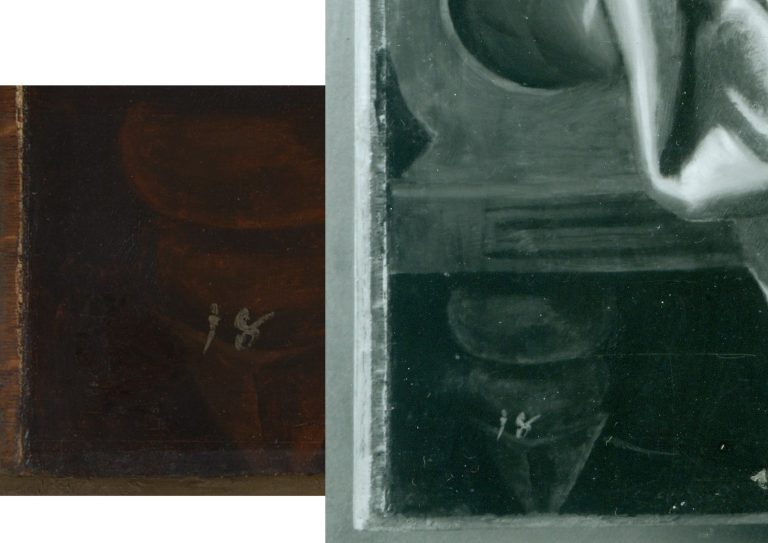

Above, Fig. 4: The Samson and Delilah’s bottom left and bottom right corners, as respectively recorded at the Gallery on the 10th and 11th of August 1982, by which dates the visible blockboard extensions (which read as the whitish strips) all around the panel had materialised within the Gallery’s own photographic records for the first time – and indicated the extent to which the new blockboard backing extended beyond the planed-down remains of the original oak panel. Earlier, the National Gallery Board Minutes of 16 May 1982 had carried the following note:

“The treatment of No 6461, proposed for Mr Bomford, was recommended by Mr Brown, who explained that the painting was to be the subject of the second ‘Acquisition in Focus’ exhibition, opening in January 1983.” It added, matter-of-factly:

“The painting had a modern support of wood attached to the original panel which had been considerably reduced in thickness and this was considered adequately stable; the surface had probably been only partly cleaned in the recent past, and tests showed considerable discolouration.”

This above account made to the Board was the first-ever mention of a blockboard backing on the painting. It had not been so described by Christie’s and, as shown below, it was even at variance with an in-house National Gallery timber expert’s 1982 account of the painting when it was on exhibition in the Gallery and ahead of its restoration. Strictly speaking, the above statement was technically accurate: the picture had, by that date, been planed down and mounted on blockboard – but only very recently so. Even though the the Gallery had had sight of the picture since the beginning of July 1980 (and had taken photographs and Infra-Red images of it on July 2 1980 – ahead of the sale) it had not – as Mr MacGregor confirmed to us – made any photographic record of the picture’s back either after buying it, or earlier when it had been loaned ahead of the July 11 1980 Christie’s sale. This lacuna is, on our familiarity with the Gallery’s technical literature and dossier records, unprecedented. Indeed the Gallery’s restorers sometimes give the impression that they are more interested in working on pictures’ physical “supports” than on their painted surfaces – and by “working on”, we mean undoing and redoing them. (See Fig. 9 below.)

A TIMBER EXPERT’S ACCOUNT OF THE SAMSON AND DELILAH PANEL

In the 1982 National Gallery Technical Bulletin, Christopher Brown, Martin Wyld and the Gallery’s (now deceased) timber expert, Anthony Reeve (who was held by Mr MacGregor to have been the “supreme practitioner of his generation”) wrote on the cleaning and restoration of Rubens’ The Watering Place and, in doing so, made clear that no blockboard backing had been applied to the Samson and Delilah at that date. That is to say, when discussing the highly problematic construction of many Rubens’ panels, Reeve noted:

“Of all the pictures in the National Gallery, Rubens’ panels have been of greater concern, because of their condition, than any other part of the collection. The reason for this is well-known. Rubens frequently found it necessary to enlarge his pictures after he had started painting… Rubens’ oak panels, often enlarged in several different stages, are amongst the most inherently unstable supports used by any artist.”

However, in so saying, Reeve drew a distinction between “the oak supports which, although made up of many planks joined together, were not enlarged during the painting process, and those which were added to.” Of that former, relatively unproblematic type, Reeve cited just three examples:

“The Rape of the Sabine Women… The Judgement of Paris… Samson and Delilah… the panels of which are made up of six, five and seven oak planks respectively. The grain of every plank, and hence the joins, are horizontal and all the planks are roughly the same width.”

In consequence, Reeve continued, although “these large panels are sensitive to changes in relative humidity (RH), they provide a sound and permanent support if kept in a controlled environment and not exposed to sudden changes in RH.” Whatever reason subsequently led to the National Gallery’s decision to plane down the panel and mount it on blockboard, it was not one of conservation necessity. Curiously, as late as 1996 Christopher Brown was still extolling the the sound construction of the Samson and Delilah’s Panel: “In contrast to a panel like the Samson and Delilah, carefully made from a small number of planks in all of which the grain runs parallel, many of the panels on which Rubens’s landscapes are painted are extremely fragile and prone to splitting”.

Thus, two years after the Gallery had bought the Samson and Delilah for a then huge sum, the Gallery itself (- and, note, just months ahead of Christopher Brown’s 16 May 1982 Board Minute-ed claim of a supposedly long-present blockboard backing) had yet to begin describing the picture as being on a radically reduced panel glued onto a larger blockboard support.

On Reeve’s (nowhere contested) 1982 Technical Bulletin testimony, although the three pictures had been well and favourably constructed, all were at risk of potential injury through their exposed bare panel backs in the event of dramatic atmospheric fluctuations. Had the Samson and Delilah already been planed down to a thickness of just 3 millimetres and mounted on a larger sheet of blockboard, there would have been no such risk or concern – and a timber craftsman as expert as Reeve could not/would not have confounded all three pictures as equally soundly-made and still intact panels which retained their original backs and such information as they bore. This conflict of testimonies within the Gallery coincides with a marked lapse in the Gallery’s own – and frequently self-proclaimed – “customary” record-keeping. That is, no documentary or photographic evidence has ever been produced to support the Gallery’s post-1983 Technical Bulletin Bomford and Plesters’ claims that the Samson and Delilah had been bought on 11 July 1980 as a greatly reduced panel mounted on a blockboard backing sheet even though, as mentioned, other photographs of the picture had been taken when it was loaned to the Gallery ahead of the sale.

Had Brown been right and Reeve wrong on the picture’s then-condition, evidence for the former would normally have been found in the customary condition reports the Gallery makes on receipt of loaned works. Because (as shown below) the Gallery has not been able to produce any written and dated reports on this picture’s condition when loaned ahead of the sale, the most-recent condition report remains that prepared in 1980 by Frans Baudouin when the picture was still – as he had testified (see below) – a cradled panel of between 2.5 and 4 centimetres thickness. Curiously, when Brown later discussed the Samson and Delilah in his 1997 Rubens Landscapes exhibition catalogue, he described it as if it comprised two separate entities. First, in step with Reeve’s 1982 Technical Bulletin account, he held it to be: “A particularly fine panel…composed of six [sic] horizontal oak planks, carefully planed and jointed. The grain runs parallel in all six pieces, which are butt-jointed. The parallel grain ensures that when exposed to humidity the wood expands and contracts without restriction…etc.” But then he went on to hold that it “was planed down to a thickness of about three millimetres and set into [sic] a new blockboard panel before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 and so, no trace of a panelmaker’s mark can be found.”

Perhaps in so reporting these two contrary states of the picture, Brown was simply recalling the two chronologically successive states of the picture as he had encountered it within the National Gallery.

THE PIVOTAL CERTIFICATE OF AUTHENTICITY TO WHICH NOBODY REFERRED

Above, Fig. 5: A photocopy of an undated typewritten sheet in German that had comprised Ludwig Burchard’s 1930 certificate of authenticity provided to the firm Van Diemen and Benedict, and which also carries handwritten Burchard notes on the path of the picture he had authenticated. The existence of this then seventy years-old document was first published by Michael Daley in June 2000 (see note [*3])

CUSTOMARY DOGS THAT DID NOT BARK

With two such expensively acquired old master pictures it might have been expected that the accounts of both would disclose the findings of the customary Gallery technical examinations made prior to works being presented to the Trustees when seeking their authorisation to purchase. However, with the Samson and Delilah no such disclosures were offered.

In 1997 the Gallery claimed to ArtWatch UK it had not kept written records of the picture’s state in 1980 when examined at the Gallery ahead of the purchase; and, therefore, it had not presented such customary reports to its Trustees when seeking authorisation to make the purchase. Indeed, the-then Director, Neil MacGregor, specifically confessed: “The National Gallery does not have any record, photographic or written, of the back of this picture before it was planed down”. The Gallery could supply only a photograph of the picture’s back “as it is today” (see Fig. 6, below, bottom left). The consequence is that while a records trail of an intact panel runs from 1930 to 1982 – when the picture was on display the National Gallery – it is said that no official record exists of its condition on arrival at the Gallery in 1980.

However, in the picture’s own dossiers (as I discovered on 14 Feb 2006) there exist two Infra-red images of the picture (one of them being of the whole picture when still in its frame; the other, a detail showing Samson. Both images were made on the second of July 1980 – that is, nine days before the Christie’s sale at which £2.53 million changed hands. Neither image was reproduced in the 1983 Technical Bulletin even though the report on the picture carried eight images of other paintings. Nonetheless, it was precisely customary for the Gallery’s “Keeper” to prepare a report on a prospective picture’s desirability and art historical importance and for the Head of Restoration to prepare a report on the picture’s condition and soundness. That requirement was expressly noted in 1986 by the Gallery’s then deputy director, Allan Braham: “Before any purchase is made by the Gallery a report on the painting and its desirability for the collection will be made to the Director by the member of the Keeper staff with responsibility for the relevant school of painting: the condition of the painting will be investigated by the Conservation Department.”

In the 1980-81 National Gallery Report, Michael Levey thanked Christie’s for their “co-operation in allowing the Trustees to see this painting in the Gallery before the sale and thus assess not only its powerful impact but also its major contribution to our representation of the painter.” And yet, a trustee in 1980 later recalled to Euphrosyne Doxiadis that no reports had been shown to the Board on the Samson and Delilah. In a letter of May 27th 1997, Mr MacGregor confirmed to us that the painting had been inspected “in the flesh” by the Trustees before the sale but, ambiguously, he added that Christopher Brown and Martin Wyld had conducted examinations and that both remembered “quite clearly that the panel was already set into [sic] blockboard, as do the Christie’s staff most directly involved in the sale.” The person most involved at Christie’s was Gregory Martin, the former National Gallery Flemish paintings specialist. Citing the recollections of Brown and Wyld seemed further to confirm they had not produced written reports on the painting’s condition and state – indeed MacGregor said that their accounts had been delivered “orally” to the Trustees. To repeat: all National Gallery claims that the back had been planed down before the picture arrived at Christie’s are contradicted by Baudouin’s 1980 condition report as commissioned by Bosselaers – and subsequently supplied to Euphrosyne Doxiadis. It had described the picture on 4 March 1980 as a “panel, 185 x 205 cms” that was “in good shape” and in a then conservation state that could be “called excellent”.

A TALE OF TWO NATIONAL GALLERY PANELS – AND THEIR RESPECTIVE PRESENTATIONS IN THE TECHNICAL LITERATURE

In 1980 the National Gallery bought two old master panel paintings for, respectively, just below and just above £2.5 million each. Both were put on immediate display. Both generated much interest. As is customary, both were soon restored by the Gallery. They were Altdorfer’s ‘Christ taking Leave of His Mother’ and the claimed Rubens Samson and Delilah. As is also customary, both restorations were reported in the Gallery’s 1983 Technical Bulletin, but the nature and manner of their accounts diverged dramatically.

THE ALTDORFER PANEL – A PLAIN AND UNPROBLEMATIC ACCOUNT

The Altdorfer was purchased by private treaty sale from the Wernher Estates, through Christie’s, with the aid of contributions from the National Heritage Memorial Fund [NHMF], the Pilgrim Trust and the National Art‐Collections Fund (Eugene Cremetti Fund). Today the NHMF says of the Altdorfer: “The acquisition of this painting strengthened the collection of German paintings at the National Gallery, then relatively under-represented. Works by Altdorfer are exceptionally rare: this painting and the Landscape with a Footbridge (Room 4) are the only two works by the artist in this country. The painting was bought for £2.45 million by the National Gallery in 1980 from the Wernher Collection at Luton Hoo, only months after the NHMF was founded. Without the intervention of the NHMF, which gave £825,000, the National Art Collections Fund (Eugene Cremetti) and the Pilgrim Trust, the painting would have been sold at auction, and almost certainly have been exported.”

THE RUBENS PANEL – A GRAVE ATTRIBUTIONAL MISFIRE

The NHMF has subsequently given much support to the National Gallery assisting it on the purchase of eleven pictures nine of which are shown online by the Gallery; but it had not done so with that of the Samson and Delilah, where Christie’s had given no price estimate in the sale catalogue and the underbidder’s identity remains unknown to this day. We had been given to understand there had been three bidders in the sale: Sir Geoffrey Agnew, acting for the National Gallery; Dr Reinhold Baumstark of the Liechtenstein Princely Collections; and, a bidder on behalf of the Rockox House Museum, who had dropped out at £1,300,000. Christopher Brown has claimed – and his successor at the National Gallery, David Jaffé, intimated in Apollo in 2000 – that Dr Baumstark had bid for the Liechtenstein Princely Collections. However, as Euphrosyne Doxiadis has reported, the then-Prince of Liechtenstein was not the underbidder, nor had he even taken part in the bidding. (See note [*4] below.)

The Samson and Delilah was bought by Agnews on behalf of the National Gallery at a Christie’s auction for a world record Rubens price of £2.53 million. The sale took place in the morning of 11 July 1980 and the picture was hung in a reserved space at the Gallery in the afternoon. A “Strictly Confidential” Gallery press release announcing the purchase had been prepared ahead of the sale. In 1983 the National Gallery Director, Michael Levey, wrote in the “Acquisition in Focus” Samson and Delilah exhibition catalogue: “…some people might have asked why the nation needed another Rubens. In the Collection at Trafalgar Square there were already twenty paintings by the artist… Rubens’ Samson and Delilah is a large scale, early and entirely autograph painting of a kind the National Gallery previously lacked.” (As shown below, Levey’s successor, Neil MacGregor, would be obliged to explain to the public why this “Rubens” looked like no other in the Gallery.)

By that date the picture had been restored and fitted with a new replica period frame made in imitation of the frame shown in Frans Francken’s copy of the original Rubens Samson and Delilah as installed in the house of its first owner, Nicholaas Rockox when its previous frame had been thought possibly original to the painting. The restoration that had immediately preceded the Gallery’ 1983 exhibition was lauded by Levey: “Its splendid colour and vigorous handling of paint can be all the better appreciated now that it appears cleaned in this exhibition.” Along with its world-record price, the Gallery had invested much scholarly/curatorial capital in this particular acquisition – on which its successive accounts would prove so unsatisfactory.

A RISE OF NON-CURATORIAL OPPOSITION THAT DREW IMMEDIATE BLOOD

There seems little question the purchase had been made in professional good faith. Since the picture’s 1929 emergence from nowhere – or, rather, from a restorer’s studio – and its 1930 upgrading by the leading (but subsequently discredited) Rubens scholar Ludwig Burchard, no Rubens specialists had demurred from the view that a well-recorded but long-lost Rubens masterpiece had been found. By the early 1990s, however, certain artist/scholars [*3] had rejected the Rubens ascription, initially, on essentially stylistic grounds and the picture’s manifest visual incompatibility with the testimony of two securely contemporaneous copies of the original painting. Although repeatedly denied by the Gallery, it would further transpire that, during its 1981-82 restoration at the Gallery, the Samson and Delilah panel underwent a covert physical transformation that left the picture at variance with all records of its condition and composition [*4]. As seen above, in 1980, when about to be sent to London, the panel retained its original and by then cradled back. When bought by the National Gallery in 1980 , Christie’s sale catalogue entry described it as being “on panel”. When on display at Christie’s, it was seen by many to have been a cradled panel – albeit one whose “bars did not slide”, as the former-Christie’s staffer, and the then Evening Standard art critic, Brian Sewell informed us.

[*3] In February 1992 a report from three art students challenging the attribution – Euphrosyne Doxiadis (author of the acclaimed The Mysterious Fayum Portraits from Ancient Egypt – see Fig. 1 above), Steven Harvey and Siân Hopkinson – was submitted to the National Gallery and placed in the Samson and Delilah’s dossiers. The Senior Curator, Christopher Brown, would later concede that “gaps at the beginning and end of the picture’s provenance” made it impossible to be 100 per cent sure this was the original Rubens Samson and Delilah of 1609-10.

[*4] That is, when upgraded from Honthorst to Rubens by Burchard, he had specifically enthused – contrary to subsequent official National Gallery claims – that the panel painting “even retains its original back”. (See Figs. 2-5.) I discovered Burchard’s nowhere acknowledged certificate of authenticity in April 2000 in a typed manuscript copy of 8 April 1930 held in the National Gallery’s own Samson and Delilah dossiers, it having presumably been passed on to the Gallery by Christie’s after the 1980 auction. When that discovery was published in the June 2000 Art Review I sent a copy to the Gallery’s Director, Neil MacGregor. The following day, the Gallery released an unsigned statement acknowledging for the first time that, contrary to the Gallery’s (Technical Bulletin) published claims of 1983, the panel of the Samson and Delilah could not have been planed down in the 19th century or in the 1920s “because it was recorded in its original state in 1930.” Nonetheless, at the same time, the unsigned statement claimed “the recent allegation” that the planing had occurred after 1980 was “false”.

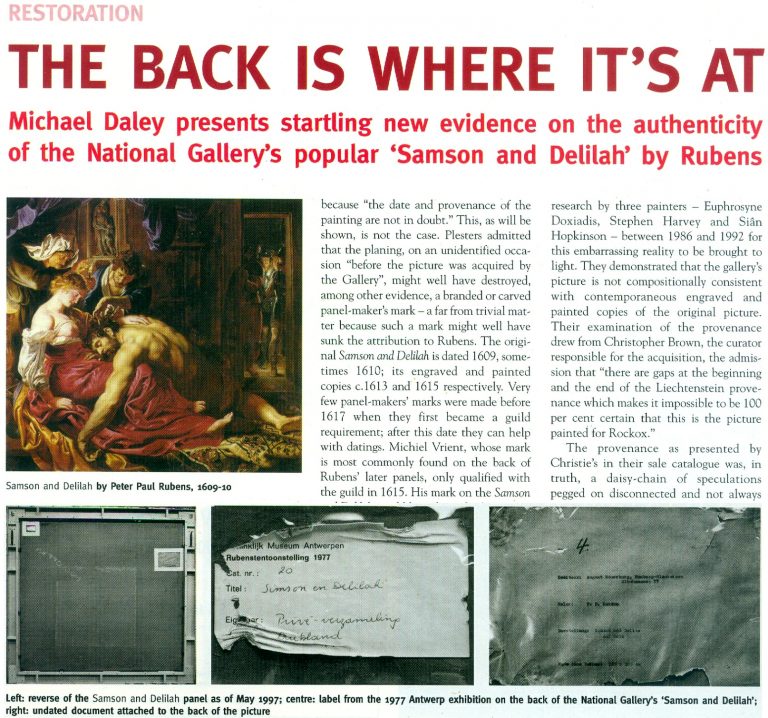

Above, Fig. 6: Extracts from the June 2000 disclosures in the Art Review.

In June 2000, in response to press coverage of the Art Review article “The back is where it’s at” (Fig. 6, above), as in the Independent on Sunday (“Tell-tale sign that £40m Rubens could be a copy”), the Times and the Guardian, the National Gallery’s director, Neil MacGregor, had a notice placed in front of the picture to explain why it looked like no other Rubens in the Gallery. That notice drew attention to a fuller statement available at the information desk in which the Gallery denied our charge of its restorers having tampered with the panel. (That document was itself an “updated” version of one prepared and displayed in 1997 in response to press coverage of challenges made by Kasia Pisarek – see Figs. 7 and 8 below).

Above, Fig. 7: The Autumn 2000 and the Spring 2006 special issues of the ArtWatch UK Journal given over to discussions of the National Gallery Samson and Delilah.

NO ANSWERS GIVEN. DEBATE REPEATEDLY SHUT DOWN. A LOOP OF SILENCE CREATED.

The National Gallery later announced Christopher Brown would publish a scholarly article in the Burlington Magazine. It never came. The magazine’s editor told us none was submitted. An article by Kasia Pisarek was submitted. It was rejected by the Burlington Magazine – and, later, by Apollo (but see [*5]). In 1998 Dr Brown left the National Gallery to direct the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. An article by his successor at the Gallery, David Jaffé, appeared in the August 2000 Apollo, but it was expressly intended to end, not launch, consideration of the evidence. Arts journalists summoned to a National Gallery press conference on the pending article were advised “it will finally silence the critics”. Our request to reply was rejected by Apollo’s editor, David Ekserdjian, a former staff member of Christie’s. He also rejected a letter from Michel Favre-Felix, a painter member of the Association Internationale pour le Respect de l’Integrite du Patrimonie Artistique – ARIPA. Christopher Brown’s departure from the National Gallery served to thwart subsequent inquiries into the Samson and Delilah’s acquisition and its subsequent unacknowledged treatment.

On 6 April 2002 (letter) we asked Neil MacGregor whether Dr Brown had been aware in 1982 of Burchard’s 1930 Certificate of Authenticity and its testimony on the then sound condition of the Samson and Delilah panel. He replied: “As I am sure you know, Christopher Brown left the National Gallery some years ago… I suggest you pursue the matter with him.” When Brown was asked by the US magazine Salon (December 2005) to comment on his past involvement in the controversy, he replied: “I am sorry but I don’t want to do this. Please address your questions to the National Gallery.” In 1983 Brown had reported: “Under the terms of Ludwig Burchard’s will, I had the privilege of consulting the manuscript notes on the Samson and Delilah. My visit to Antwerp was made possible by a grant through the Sir Martin Davies Travel Fund”. Had Burchard’s own notes held by the Rubenianum not contained a draft or other record of his 1930 certificate of authenticity, as is held in the National Gallery?

THE VALUE OF REPORTS

When, after we had published Burchard’s certificate of authenticity and Neil MacGregor had adjusted the Gallery’s position accordingly, Christopher Brown and his successor, David Jaffé, held that the Samson and Delilah had been planed down when in the collection of the German magnate, August Neuerberg, between 1930 and 1980. In doing so, they went against the testimony not only of Baudouin’s March 1980 condition report but also of a leading Rubens scholar and National Gallery benefactor who had gifted a Poussin – Christopher Norris. As first mentioned in our June 2000 Art Review, article, Norris had testified in a 1980 letter (held in the picture’s dossiers) to the director, Michael Levey, congratulating him on the Samson and Delilah’s acquisition, and adding that between 1930 and 1980, no change in the picture’s “amazing condition” had occurred, other than a toning down in its 1929 varnish, because “the owners had not touched it.”

Thus – and in addition to Baudouin’s 1980 condition report – we now know on Burchard’s and Norris’s joint written testimonies (both of which are held by – but neither of which had been disclosed by – the National Gallery) that the panel was intact, in good condition and had retained its original back from 1930 until 1980 when it was sent to Christie’s. Therefore, the only parties who might have planed-off the back are Christie’s and the National Gallery itself. Christie’s, who described and sold the picture as a panel and not as a reduced panel laid on board, or as a marouflaged panel, would hardly have so-profoundly and radically transformed someone else’s property (and someone, that is, who as the work’s sole known owner, had left the picture untouched for half a century) – or, for that matter, have had the time and the great technical means to do so. But even if Christie’s had done so, the National Gallery would then, in turn, have duly recorded that recently-altered state of the picture in its customary reports on works loaned to it ahead of sales. It had not done so (see below).

Ignoring the triangulated testimonies of Burchard, Baudouin and Norris, David Jaffé’s second tack had been a more personal charge: “Mr Daley does not seem be aware of the art historical convention whereby a painting on panel, even when thinned, is still called a panel”. He cited the following instance: on December 17th 1998, Sotheby’s auctioned Rubens’ Deluge as an “oil on oak panel” when in fact it was “on a marouflaged panel”.

But how had that been that known? It was so, Jaffé disclosed, “according to a condition report” made at the Gallery by its timber specialist/restorer, Anthony Reeve (which report is held in the Gallery’s exhibition file) when the picture was loaned to the National Gallery ahead of the sale. Why then, is no such report held and cited on the Samson and Delilah when it too had been loaned to the Gallery ahead of its 11 July 1980 sale at Christie’s?

HOW RELIABLE ARE LUDWIG BURCHARD’S ATTRIBUTIONS?

[*5] In an article published in the Spring 2006 Artwatch UK Journal (Fig. 7, above right), Kasia Pisarek (Katarzyna Krzyżagórska-Pisarek) wrote:

“While investigating Dr Ludwig Burchard’s ‘rediscovery’ [of the Samson and Delilah], I was surprised at some of the truly improbable attributions made in the past by him and other well-known experts such as G. Gluck, W. R. Valentiner, W. von Bode, A. Bredius or C. Hofstede de Groot, who all guaranteed their ‘discoveries’ with certificates of authenticity…” On Burchard, specifically, “I traced many of his attributions – he was not infallible in his judgement and changed his mind. Surprisingly, over sixty pictures attributed by Burchard were later downgraded (in Corpus Rubenianum) to studio works, copies or imitations…”

To date, Dr Pisarek has identified seventy-five fallen Burchard Rubens’ attributions. (The title of Pisarek’s 2009 Warsaw University dissertation was “Rubens and Connoisseurship: On the Problems of Attribution and Rediscovery in British and American Collections.”)

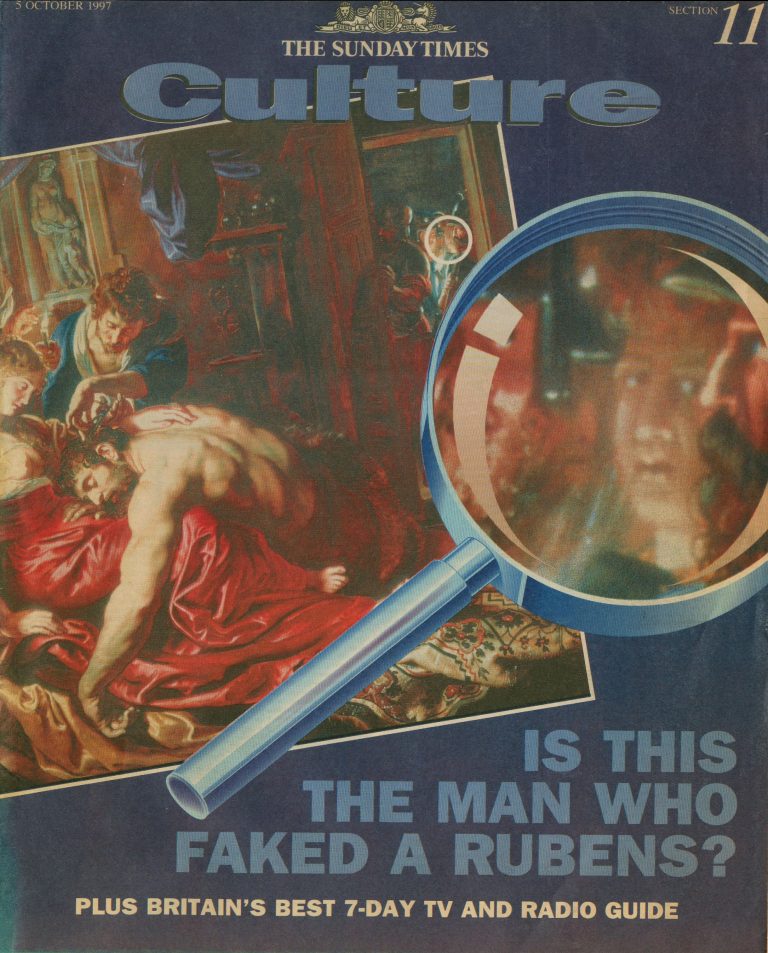

Above, Fig. 8: The Sunday Times’ 5 October 1997 coverage of Kasia Pisarek’s rejection of the Samson and Delilah’s Rubens ascription.

Certain suspicions seem to have arisen in Waldemar Januszczak’s mind as he (at that date) rejected the Samson and Delilah’s Rubens attribution in the above Culture Magazine feature and pressed the striking Whodunnit Mystery of the Disappeared Back:

“…I put this to the gallery’s chief conservator, Martin Wyld, who quips cheerfully that he was rather proud of having been accused; planing a 17th-century oak panel to wafer thinness and attaching it perfectly to blockboard while leaving its surface in pristine condition, is an exceptional feat of restoration. Nobody would or should do it today. Whoever did it earlier did a masterful job. Why did they do it at all? If a painting is in exceptionally good condition, why was there any need to hazard the transfer to block-board? A question neither the chief conservator nor MacGregor can answer. All I got from them both is the National Gallery version of: it wasn’t us, guv.”

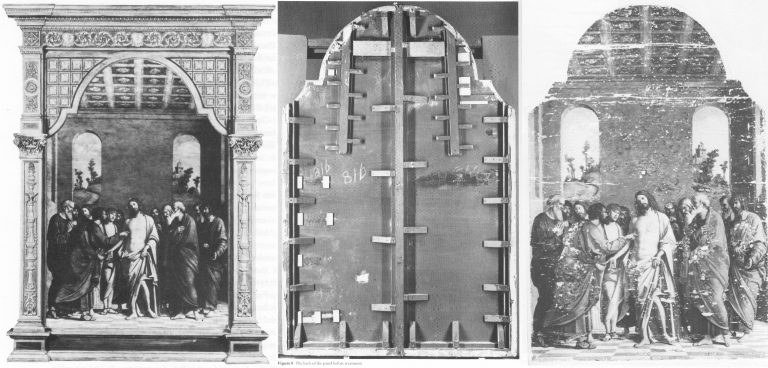

Had Januszczak been a student of the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletins he might have recalled that accounts were given in the 1985 and 1986 issues of how Martin Wyld had chiselled away the entire wood panel of seven giant planks just under two metres long of Cima’s The Incredulity of St Thomas and that, in the first stage of this supposedly now verboten practice, the panel was reduced “from c. 5 cm to 1 cm” and in the second stage, the remaining 1 cm of wood was chiselled away entirely until the back of the original gesso coatings was exposed and ready to be attached for ever to its entirely new synthetic materials sandwich.

For a glimpse into the National Gallery’s subterranean Factory for Restoration and Attribution Rehabilitations, see:The National Gallery’s Made Just like Rubens Samson and Delilah with Cropped Toes

Above, Fig. 9: The National Gallery’s Cima da Conegliano altarpiece, The Incredulity of S. Thomas. Left, the altarpiece before restoration; Centre, the back of the panel, before its entire removal and replacement; Right, as seen after cleaning and before retouching – and after the transfer of the surviving gesso and paint film onto a multi-layered synthetic support.

RECORDS v RECOLLECTIONS AND BOY-GANGS IN ACTION

If the documentary record is to be trusted, it can be said with certainty that someone within the National Gallery covertly planed the Samson and Delilah panel. Notwithstanding his later Jaffé-flaunted recollection of August 2000, Frans Baudouin [*6] had, in his 1980 condition report prepared for the Samson and Delilah’s owner, Mrs Margaret Köser, solemnly testified on his (likely financially remunerated) professional oath (as the picture was about to be dispatched by the banker Jan Bosselaers from Antwerp to Christie’s in London), that it was a panel between 2.5 cms and 4 cms thick – and, therefore, had not-yet been planed down to a thickness of under 3 millimetres and cemented onto a sheet of modern blockboard. And yet, in the face of all such precisely documented facts between 1930 and 1980, David Bomford would, in his 1983 National Gallery Technical Bulletin account, backdate the planing to an unspecified time, place, and person – viz: “At some time, probably during the present century…” – and, when so-saying, would offer not one jot of supporting technical, photographic or documentary evidence in an institution that had long claimed exemplary record keeping practices.

[*6] Frans Baudouin was described in Codart on his death in 2005 as: “the doyen of Flemish art historians. He was the former director of the Rubenshuis and the driving force behind the founding of the Rubenianum, as well as an outstanding specialist in Rubens.” Nonetheless, he had declined to discuss the Samson and Delilah’s attribution with Euphrosyne Doxiadis (the first critic of the picture’s ascription and a co-author of the 1992 Report submitted to the National Gallery) whom he had met socially. In his August 2000 Apollo article, Dr. Jaffé, belatedly acknowledging Burchard’s certificate of authenticity record of the original panel, wrote: “Three Rubens experts – Dr. Frans Baudouin, Dr. Reinhold Baumstark and Dr. Hubert von Sonnenburg – who had been contacted by potential purchasers and therefore studied the painting with particular attention, all recall seeing it in its present condition just prior to its sale at auction on 11 July 1980.”

Powerful and triangulated testimony, it might well have been thought. However, one might also assume, for example, that Baudouin’s professional documents were likely more trustworthy than his twenty years-old recollections. In support of the former, the photograph (above, Fig. 2) of the Samson and Delilah when out of frame in 1980, and as supplied to Euphrosyne Doxiadis by Jan Bosselaers, along with Baudouin’s own 1980 certificate of condition for the Samson and Delilah might be cited. Further, as mentioned, in 2001 Doxiadis asked Baumstark’s successor at the Liechtenstein Princely Collections, Dr Uwe Wieszorek, if the then-Prince of Liechtenstein had been the underbidder at the 1980 Christie’s sale. In NG6461 she now reports: “He assured me categorically in two letters that as far as the Collections were aware, the Prince was not the underbidder, nor had he even taken part in the bidding.”

As for Dr. Hubert von Sonnenburg [*7], the then Head of Conservation for the Metropolitan Museum, might he be taken as the unsuccessful underbidder? When advising that museum on the possible purchase of the then-sublimely preserved Velázquez Juan de Pareja (which was bought for the Met. from Christie’s in 1971), Sonnenburg had strenuously advised the picture should under no circumstances be bought if its canvas had been relined. Would he likely have advised that great museum to buy a reduced panel laid on blockboard at a nowhere-recorded location and time? If he had, had the Met. attempted to buy the Samson and Delilah but been outbid for once by the National Gallery? Jaffé does not say – but where Christopher Brown had told Euphrosyne Doxiadis that the Prince of Lichtenstein had been the underbidder, for their part Christie’s had refused at the time of the sale to identify the (to this day, mysterious) underbidder, whose bids were said to have been relayed to the main sale room by telephone from an anteroom.

[*7] As we noted in a March 2011 post – Hubert von Sonnenburg was certainly an adept of art museum secrecy:

When, in 1971, the Met. snatched Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja from the British (who had owned it for centuries) Thomas Hoving, Ted Rousseau, von Sonnenburg and Everett Fahy had all flown to London, Madrid, and Rome – a sort of “boy-gang”, as they saw it, playing at spreading rumours like “the disinformation section of the KGB” – as Hoving (who later claimed to have discussed with Wildenstein’s how to “manipulate the art press and crank up the rumor mill” in a general strategy of “dissimulation and misleading rumors”) put it in his memoir. Even when successfully bought, the Velázquez was not paraded at the Met. but, rather, was “sneaked” into Wildenstein and Company “for secrecy”, partly because funds had been committed without the Board’s knowledge and also because, as Hoving put it, the Board had to remain longer in the dark as further “total secrecy” would be needed to “prepare our public relations stance” and to “have the time to clean it.” The deception of the public was to be absolute: for a short period before the restoration, the picture was exhibited to New Yorkers as if it were Wildenstein’s own property. Subsequently, the Met audiences only got to see the von Sonenburg-redone Juan de Pareja and not the miraculously well-preserved jewel that had, some time before, been taken to the New World by a triumphalist, dissimulating art world boy-gang.

In Part II – A TALE OF TWO ASCRIPTIONS AND THEIR RESPECTIVE TECHNICAL EXAMINATIONS – we examine the remarkable methodological discrepancies evident in the National Gallery’s own respective 1983 accounts of its two expensively bought 1980 panel paintings, and show why the Samson and Delilah should never have been presented from 1930 onwards as the long lost Rubens of 1609-10.

POSTSCRIPT: See Dalya Alberge’s disclosures in today’s Guardian:

A £2.5m dud? Fresh doubt cast on authenticity of National Gallery Rubens

15 June 2025

To Criticise a Critic

An examination of certain pre-emptive scholarly/art market establishment strikes against a pending book that rejects the Rubens ascription of the National Gallery’s contested Samson and Delilah.

Michael Daley writes: Those who challenge art establishment scholars or institutions can suffer swift repudiation and denigration in lieu of frank and open debate, as I discovered when supporting Prof James Beck’s criticisms of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling restoration in the late 1980s. In the 1996 edition of the Beck/Daley Art Restoration – The Culture, The Business, And The Scandal, in a chapter headed “The Establishment Counter-attacks”, I noted:

“When criticized in this area, institutions react institutionally, which is to say, by deploying self-protecting mechanisms common to all establishments. The best and most favoured response is no response, implying that the criticism is inconsequential and deserves to be ignored. In those instances where a response is unavoidable, it is thought best to be made by proxy… When a direct defence is necessary, its tone becomes all important. By tradition, the tone ranges from amused disdain, through supercilious dismissiveness to outright disparagement and attempts to discredit personal or professional credentials.”

It seems little has changed and that responses to the imminent arrival of Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s book on the National Gallery’s supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah (NG6461 – The Fake National Gallery Rubens) have run true to institutional templates. As a case in point, take this even-handed Artnet account: “Is This Rubens Real? Inside the ‘Samson and Delilah’ Debate” by Jo Lawson-Tancred.

Lawson-Tancred reports an anonymous National Gallery spokesman’s claims that the picture “has long been accepted by Rubens scholars” and that the Gallery finds no cause to update its initial technical examination of the painting [as had been reported in its 1983 Technical Bulletin] and whose “findings remain valid.” The first part is true – Rubens scholars had so accepted the attribution. However, the insistence that the report on the then recently acquired, exhibited, and restored £2.53mn picture requires no updating disregards subsequent findings on this and other Rubens paintings.

To be precise, the Gallery claimed in 1983: “At some time, probably during the present century, the panel was planed-down to a thickness of 3mm and subsequently glued onto a sheet of blockboard”. As Doxiadis and we have established the picture had emerged as a panel in 1929 – albeit ascribed to Honthorst. Crucially, it had remained a panel when sent to Christie’s, London, for sale in 1980 as an autograph Rubens – indeed it was precisely so described in Christie’s 1980 catalogue (see Fig. 1 below.) The picture’s physical state as a panel had been disclosed to Doxiadis by a Belgian banker who had wished to buy the picture for the Rockox House museum in 1977 and who again held it in Antwerp for its owner in 1980 before sending it on her behalf to Christie’s, London. Beyond any question, it was still an intact panel at that date.

WHERE’S THE BEEF?

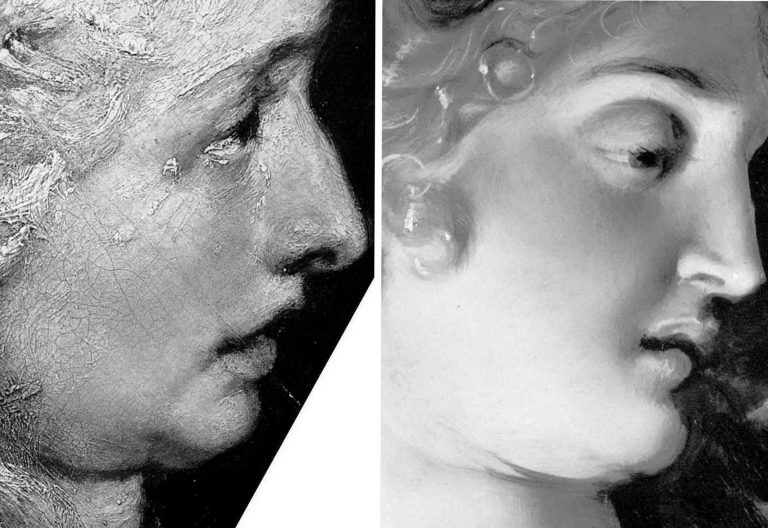

Fig. 1, above: Christie’s 1980 sale catalogue entry on the Rubens-attributed Samson and Delilah panel. Note how the entry comprises a daisy-chain of “probablys” and “possiblys” – and also its parenthetical disclosure that, throughout its claimed long stay in the Liechtenstein Collection, this Samson and Delilah had not been judged a Rubens.

Given that we informed the National Gallery a quarter of a century ago of the picture’s confirmed physical status as a bowed and cradled panel in good shape in 1980, its 1983 technical account has long needed correction because the planing had not taken place before 1980, let alone in the 19th century. And yet, that manifestly unfounded suggestion that the planing might have occurred before the 20th century had been endorsed by Joyce Plesters, the Gallery’s Head of Science in the 1983 Technical Bulletin: “Unfortunately, as David Bomford has described, the back of the panel had been planed down to a thickness of only about 3mm and then the whole set into blockboard before the picture was acquired by the National Gallery…” In truth, it had not been set into the blockboard, but rather, as Bomford had correctly reported, and Doxiadis would later discover, it had been glued onto a blockboard sheet larger than itself and fitted into a new purpose made frame.

On the combined records of 1929 and 1980 that Doxiadis and we had uncovered – and as on Christie’s own published catalogue description – it followed that the planing could only have occurred after the picture was sold to the Gallery for its then world record Rubens price of £2.53million in 1980. Our concerns were compounded when informed (by the National Gallery’s then director, Neil MacGregor) that the Gallery had not followed its own procedure of preparing written curatorial and restoration reports on the picture’s desirability and condition to assist the trustees when they examined the picture (which had been loaned to the Gallery ahead of the sale – see below) to consider an authorisation of the purchase.

AN APPEAL TO AUTHORITY

In view of Doxiadis’s recently reported disclosures on the picture’s physical condition in 1980 (Dalya Alberge “Fresh doubt cast on authenticity of Rubens painting in the National Gallery,” ) Lawson-Tancred might have questioned or challenged the National Gallery’s abiding stance. Instead, she reported:

“…despite the marginal but adamant voices of researchers like Doxiadis, top scholars in the field support Samson and Delilah’s authenticity unequivocally. Chief among these is Nils Büttner, chairman of the Centrum Rubenianum in Antwerp, who is working on the Corpus Rubenianum, the definitive catalogue raisonné for the Flemish Baroque painter. He has previously described the doubts about Samson and Delilah’s provenance as “conspiracy theories.” However, Lawson-Tancred also noted that “Büttner [had] declined to comment on Doxiadis’s book”. While Büttner, presumably, has not yet read the unpublished book, his assertions received immediate support from players in the art trade:

“Büttner’s position is backed by his peers like Adam Busiakiewicz, a lecturer and consultant on Old Master paintings for Sotheby’s. He pointed out to the Telegraph that Doxiadis is not a scholar of the period and has mostly published on Greco-Roman antiquities previously. Though she ‘had a hunch the quality of the picture wasn’t good enough’, he said, ‘I think there are some misunderstandings about the painting.’”

On misunderstandings, Busiakiewicz (who seems also to be employed by the art market “sleeper-hunter” and former Philip Mould assistant, Bendor Grosvenor, on the latter’s “Art History News” blog site), paraded just such in his reported burst of professional condescension to Doxiadis:

“Busiakiewicz explained that a comparison between Samson and Delilah and other paintings by Rubens are complicated, especially when they were made decades apart. ‘He’s an artist that changed his style throughout his career,’ he said. ‘Art historians who specialize in paintings like Rubens’ can track these changes.’ It is for this reason that the National Gallery painting has been connected to Rubens’s interest in the work of Caravaggio and other Renaissance masters whose work he had, at that time, recently encountered while traveling in Italy.”

While it is widely known that Rubens underwent changes of manner in his later paintings, Busiakiewicz failed to acknowledge (or appreciate?) that Doxiadis, we, and other critics of the attribution, such as Dr Kasia Pisarek, have for decades pointed out and demonstrated that the Samson and Delilah is glaringly unlike the bona fide Rubens paintings made precisely in that brief period when the artist had just returned from Italy.

Specifically, we had reminded readers in November 2021 that:

“In a pioneering 1992 report, the scholar/painter Euphrosyne Doxiadis and the painters Stephen Harvey and Siân Hopkinson, conducted a focussed survey of six Rubens paintings of 1609 and 1610 and demonstrated that “All these display a consistency and quality of style which is not shared by the Samson and Delilah”. That report – “Delilah cut off Samson’s hair, but who cut off his toes? The case against the National Gallery’s ‘Rubens’ Samson and Delilah” – was placed in the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah dossiers and is published on the dedicated In Rubens Name website.”

WHITHER THE PANEL’S BACK

Above, Fig. 2: The covers of two ArtWatch UK journals given over to detailed accounts of the Samson and Delilah problems and shortcomings.

In issue 21 Kasia Pisarek wrote: “The Corpus Rubenianum project is based on the archive left by the late Dr Ludwig Burchard. Should it perhaps follow it less closely? Dr Burchard was an active Rubens attributionist in Berlin before the Second World War and in London afterwards. Several paintings formerly attributed to Rubens’s school or studio or even to another artist (such as Samson and Delilah), were reinstated by Burchard as by the master. I traced many of his attributions – he was not infallible in his judgement and changed his mind. Surprisingly, over sixty pictures* attributed to Rubens were later downgraded (in Corpus Rubenianum) to studio works, copies or imitations.” Pisarek adds: “they were, however, mostly portraits of small or medium dimensions.”

If a major work like Samson and Delilah might be considered something of an exception, Doxiadis supplies a possible explanation – Burchard was a relative of one of the owners of the dealing firm that had brought the supposed Honthorst to the marketplace.

*On the subsequent completion of her PhD thesis – Rubens and Connoisseurship: Problems of Attribution and Rediscovery in British and American Collections – Dr Pisarek remarked: “I traced many paintings attributed by Ludwig Burchard… At least seventy-five works he certified authentic were subsequently downgraded to studio works, copies, and imitations in the volumes of the Corpus Rubenianum, and the list is not complete… can we trust Burchard’s old rediscovery and attribution of the London Samson and Delilah?)

In issue No.11 we had written: “On December 17th 1998 Dr Jaffe [David Jaffé, then Senior Curator at the National Gallery] writes: ‘Sotheby’s auctioned Rubens Deluge as ‘oil on oak panel’ when, in fact, it was on a marouflaged panel’.” But how is this known? It was so, Jaffé discloses, “according to the condition report made in 1996-97 when the picture was loaned the National Gallery…” But no such condition report was made when the Samson and Delilah was loaned to the National Gallery by Christies ahead of the sale. That condition report on the Deluge had been prepared by the National Gallery’s timber specialist restorer, Anthony Reeve. As recently as 1982 Reeve had reported in the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin (see Fig. 7) that the Samson and Delilah was “one of only three well-made straightforward Rubens panels in the collection” – which panels, he elaborated, required stable humidity because otherwise “The effect of wood shrinkage on the exposed backs of the panel…is for the front to become convex, and perhaps slightly corrugated”. Had the Samson and Delilah been planed-down and glued to blockboard at that date there would have been no possibility of its back being subjected to environmental hazards. It might be thought inconceivable that the National Gallery should have lost recollection of Reeve’s testimony by the following year and when writing in the same publication. As the National Gallery’s senior picture restorer Reeve was held after his death by Neil MacGregor to be the “supreme practitioner of his generation.”

There are yet further confirmations of the panel’s still-then exposed back. Doxiadis had obtained a Belgian condition report on the Samson and Delilah which began: “On arrival on 4 March 1980, about 14.30 hours the painting mentioned above (panel, 185 x 205 cms) was in good shape…” Doxiadis’s account squared with testimony supplied to ArtWatch by the art critic Brian Sewell (an ex-Christie’s man who took pride in having there identified an oil sketch as the modello for the Rubens Samson and Delilah), namely: that the panel had not been mounted on blockboard; that the back of the panel had been painted in a darkish matt colour and was criss-crossed with supporting bars of wood; that because Christie’s customary stencil number was made with dark paint it had been superimposed over a patch of white paint Christie’s had applied to the panel’s back.

Presumably Busiakiewicz has yet to access the 1992 Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson report. For the record, the document I found in the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah dossiers was a copy of the picture’s 1929 certificate of authenticity written by the great but subsequently discredited Rubens specialist Ludwig Burchard who had observed: “The picture is in a remarkably good state of preservation with even the back of the panel in its original condition”.

A CRITICAL FORMATION ASSEMBLES…

Where Busiakiewicz patronises Doxiadis on an allegedly insufficient familiarity with the Samson and Delilah literature, Nils Büttner has been joined in that disparagement by Bert Watteeuw, the director of the Antwerp Rubens House. As John Smith reports in the EuroWeekly:

“The latest suggestion that this is a 20th-century copy comes from Greek art historian Euphrosyne Doxiadis in her new book The Fake Rubens although this accusation finds little support from one of Belgium’s top Rubens experts Bert Watteeuw. Not only does he pour scorn on her status as a genuine expert, suggesting that anyone of any standard would have already checked with his Antwerp Rubens House and other specialist houses about the painting. In addition, he also said: ‘the provenance of this painting is very well known throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. A provenance that can be trusted is always crucial’…”

This implied claim of a trustworthy Rubens provenance was a brazen sleight of hand: what John Smith was not to know is that, as shown above, the provenance concerned at no point confirmed the painting as being by Rubens’ hand. Being thus kept in the dark, poor Smith could only but conclude: “Whilst the National Gallery has kept a dignified silence on the matter of the painting, it is no doubt delighted that one of the great Rubens scholars has come out publicly to dismiss the fake claim by Doxiadis which Watteeuw considers is purely invented to promote her book.”

Delighted as the National Gallery might be and while its Trappist silence might do yet further service as an institutionally imperative damage limitation exercise, it remains an untenable stance because, as one very distinguished former National Gallery trustee at the time of the Samson and Delilah purchase told Doxiadis, “the truth will come out – it always does”. As for Watteeuw, for a Rubens scholar at the supposed top of his professional tree to resort to professionally unfounded claims and personally directed abuse is as counterproductive as it is contemptible.

Moreover, in this regard, Watteeuw might be considered a serial offender: when apprised of negative AI findings on the Samson and Delilah panel he told another journalist, Colin Clapson (‘Fake Rubens in London’s National Gallery? This painting is genuine” counters Rubens House director Bert Watteeuw”) that Doxiadis’s soon-to-be-published book is “Complete nonsense and not based on facts. To begin with, I do not know this art historian and that is a sign. Most researchers on Rubens have passed by our Rubens House and the Rubenianium, the Rubens Library, in the search of sources and information,’ says Bert Watteeuw, the director of the Antwerp Rubens House. ‘Moreover, Doxiadis has an agenda of her own: to promote her book and that seems to be working well. In such cases conspiracies à la Dan Brown are more interesting than science.’ Whilst attacking its critic, Watteeuw gifts the National Gallery a clean bill of scholarly probity on its protracted silence: “‘The painting ‘Samson and Delilah’ in London is a genuine Rubens, a masterpiece. It is logical that the National Gallery does not want to comment or discuss its authenticity,’ he says.”

DISALLOWED TESTIMONY

In view of the above it might seem that among Rubens establishment scholars generally and for the National Gallery itself, nothing can be allowed to count as evidence against the challenged panel’s Rubens ascription. For example, in 2021, the brushwork of the Samson and Delilah was compared with that found in no fewer than 148 uncontested Rubens paintings. As Dalya Alberge noted in the Guardian (“Was famed Samson and Delilah really painted by Rubens? No, says AI”), “Its report concludes: ‘The AI System evaluates Samson and Delilah not to be an original artwork by Rubens with a probability of 91.78%.’ In contrast, the scientists’ analysis of another National Gallery Rubens – A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning – came out with a probability of 98.76% in favour of the artist.”

Such disinterested testimony is dismissed by the affronted – and perhaps professionally discomfited – scholarly grandees: “Watteeuw also dismisses AI research dating from a few years ago. ‘When that appeared, we engaged in extensive behind-the-scenes dialogue with that Swiss firm that had carried it out. AI can only work if you train it with an artist’s entire oeuvre. That was not the case at that time.’” (Watteeuw was here echoing Bendor Grosvenor’s mis-characterisation of the Swiss firm: “It is simply not possible to determine whether a painting is by Rubens by relying on poor quality images [sic] of not much more than half of his oeuvre…”) First, there is once again, as with Doxiadis, an implicit professional slur on the firm in question. Second, there is yet further evidence that logic is underemployed by many art establishment players: if, given the very great distinctiveness of Rubens’ style and painterly applications, you can find no visual correspondences when comparing the Samson and Delilah’s brushwork with a single one of 148 secure Rubens paintings, why would you be likely to find such correspondences in another batch of equally secure Rubens paintings? At this point, calling for yet more extensive AI tests on a vast oeuvre – and one with ever-shifting boundaries – is procrastination, the obliging sister of obdurate institutional silence.

CAN’T SEE – OR WON’T SEE?

Professor James Beck once remarked that too many of his peers “look with their ears” and that it is “only the artists who can see things clearly”. It so happens that all the principal critics of the Samson and Delilah picture – Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson/Daley/Pisarek – happen to have trained as artists, as Beck himself had done. Doxiadis noticed what no Rubens scholar, so far as we know, had noticed: that while Rubens painted with round brushes, the shadowy author of the Samson and Delilah had deployed flat brushes.

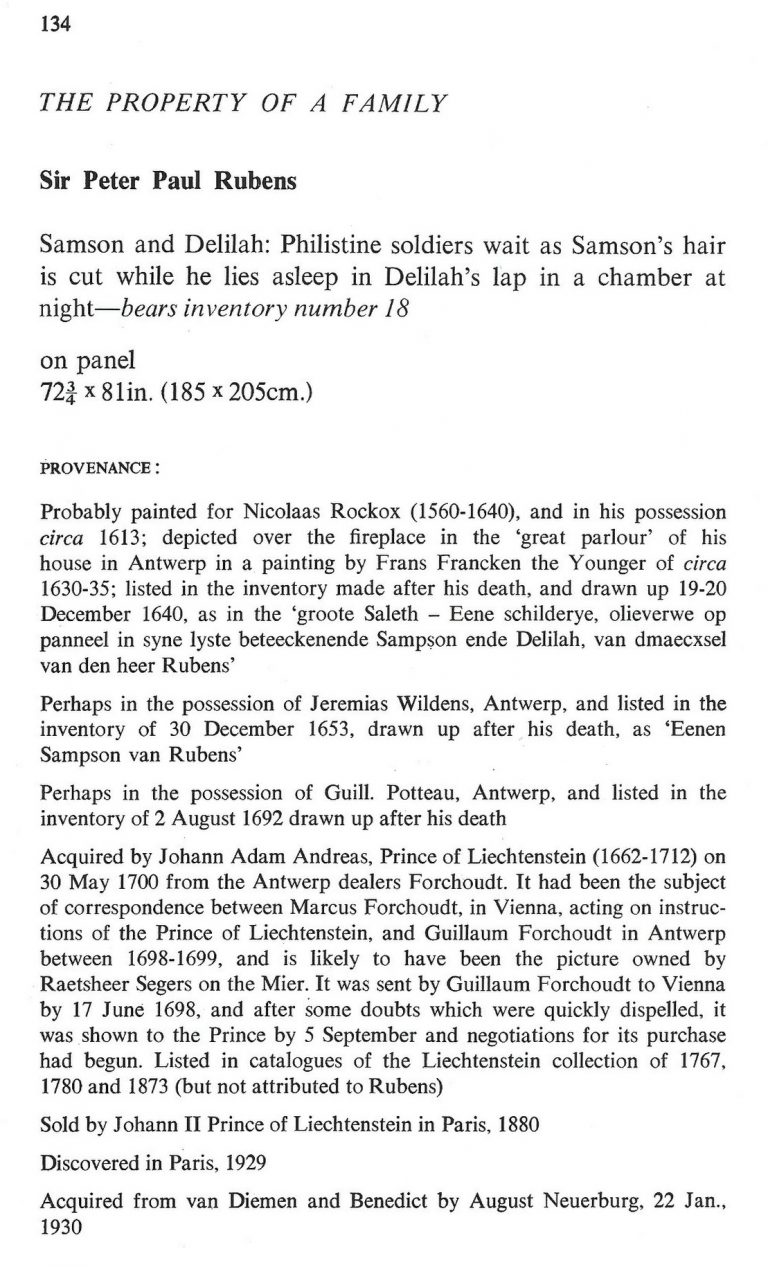

Above, Fig. 3: Top, detail of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah; above, detail of Rubens’ The Raising of the Cross, Antwerp Cathedral. Where the former is claimed to be a lost picture Rubens painted in 1609-10, the latter was indisputably made by Rubens between 1610-11. Such pronounced differences in brushwork are inconceivable as that of two autograph paintings made at the same moment in Rubens’ oeuvre. Who, looking at this photo-comparison, could believe that Rubens had flitted between the ugly angular Cubist faceted feet in the Samson and Delilah statue (– try counting the toes and note the Art Deco zigzagging hem), and the superb plastic fluency, grace and anatomical fidelity seen throughout the Raising of the Cross?

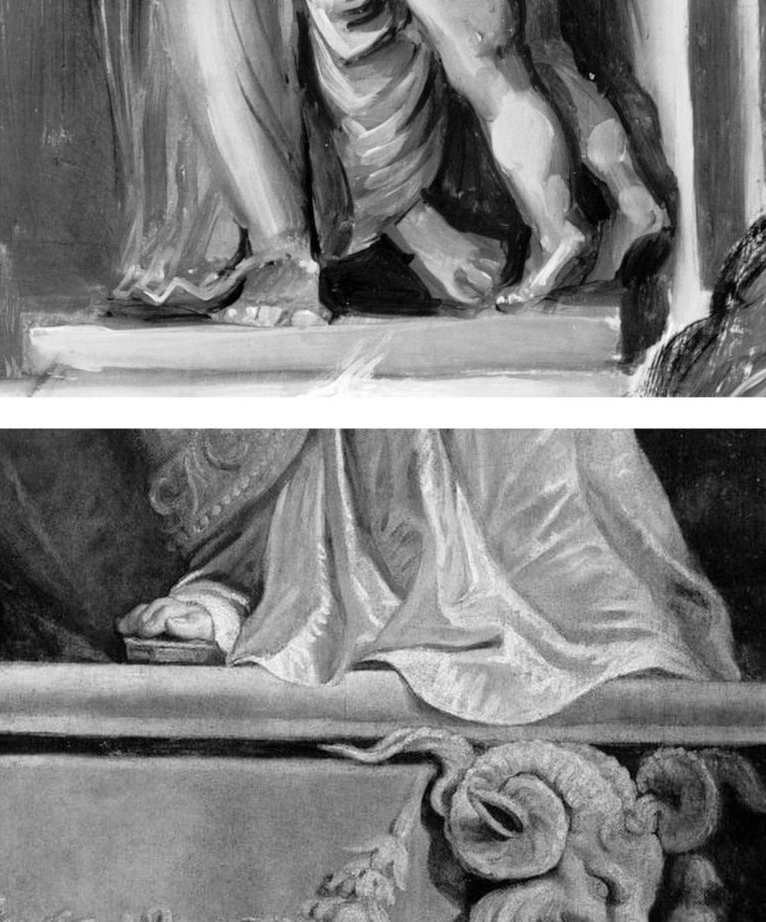

Above, Fig. 4: Two copies of the lost original Rubens Samson and Delilah – Top, Jacob Matham’s c. 1613 engraving (here reversed); bottom, Frans Francken II, a detail of his oil on copper depiction of the Grand Salon in Nicolaas Rockox’s House, made between 1615 and before 1640. Neither copy shows the cropped right foot found on the National Gallery picture. No one has cited a similarly cropped limb in any finished Rubens painting.

Above, Fig. 5: The National Gallery’s supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah painting.

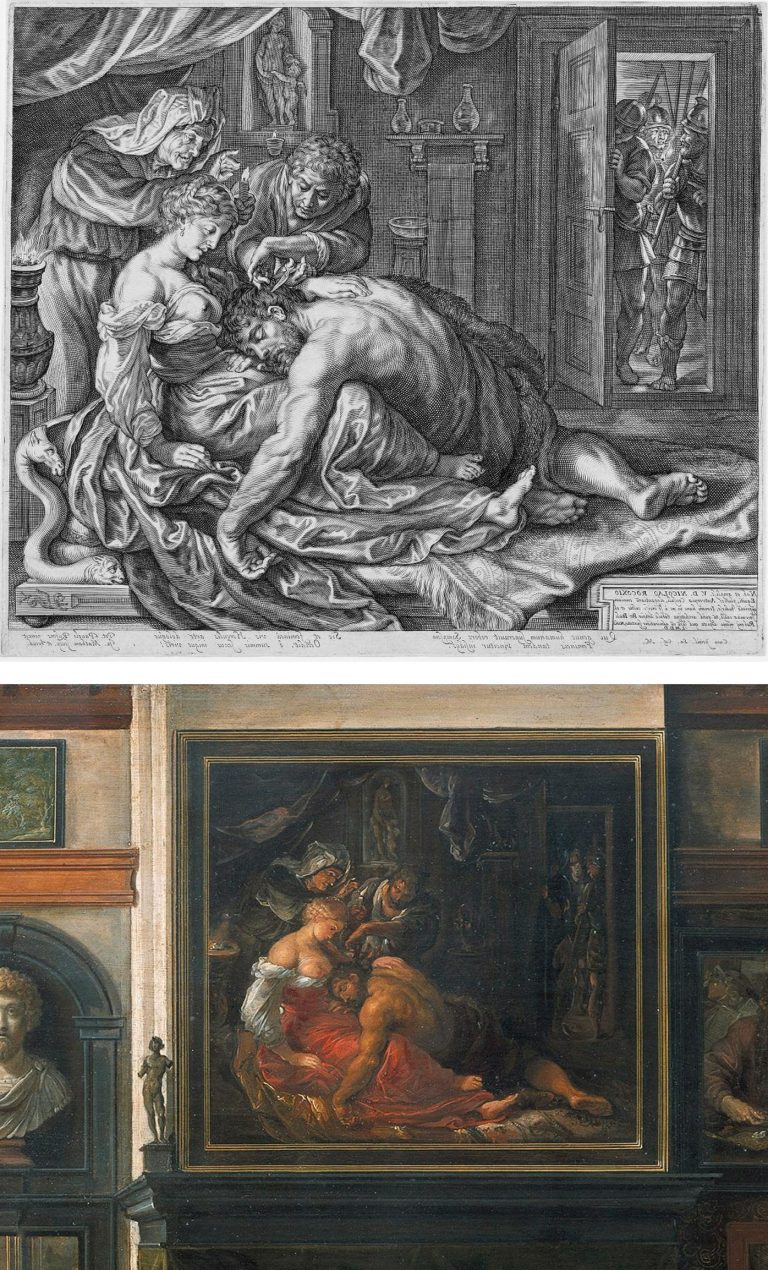

Above, Fig. 6: Left, a detail (from the left wing) of Rubens’ 1609-1610 The Raising of the Cross, Antwerp Cathedral. Right, a detail of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah which Christopher Brown (David Jaffe’s predecessor as Senior Curator at the National Gallery) dates at “c.1609” and Jaffé puts “about 1610”. Among the National Gallery picture’s countless visual disqualifications, we would cite: the thinness of the paint; the absence of a 17th century craquelure; the irresolute profile; the cinematic lighting of the head; and, the anatomical and perspectival travestying of Delilah’s nose/mouth/chin configuration.

For many more disqualifying photo-comparisons, see Abigail Buchanan’s “The National Gallery ‘masterpiece’ that’s probably a fake”.

TANGLED DOCUMENTARY WEBS…

Such clinching visual evidence, however, leaves Adam Busiakiewicz unmoved and unpersuaded. He tells the Daily Telegraph that the National Gallery Samson and Delilah could be in no one but Rubens’ hand – viz: “‘It is a really stonking great picture,’ he says. ‘The textures, the sumptuous drapery, the muscular back – no one except Rubens could have painted that.’” Each to his own art critical estimations, perhaps, but what happened to the Samson and Delilah when in the National Gallery’s restoration studios is – or should be – a matter of scrupulously recorded and reported facts. We are now faced by a major art institution that cannot/will not give a proper and credible account of its own actions; that effectively denies, even, the historical record of its own doings. Consider the recorded facts: (1) it is a matter of record that this painting emerged in 1929 as a sound panel and that it remained so in 1977 (when exhibited in Antwerp); (2) it is known that in 1980 the picture was a panel when it was dispatched to London; when it arrived in London; and, when it was sold in London to the National Gallery; (3) it is known that when in London and on exhibition at the National Gallery it remained a panel in 1982 (- see Fig. 7 below). However, it is also known that the following year the National Gallery claimed – after the picture had been restored at the Gallery – that it was not now a panel at all – and, indeed, that it had not been a panel for a very long time and possibly, even, into the 19th century or beyond. This extraordinary denial of the picture’s own documented historical record might seem inexplicable in a major national institution, but it is by no means unprecedented – and nor, for that matter, is the Gallery’s effective outsourcing of its own defence to obligingly helpful scholarly proxies.

Not the least consequence of misleading institutionally-official accounts is the corruption of subsequent scholarship and the making of monkeys out of good faith and technically trusting patrons. In part-defence against widespread and prolonged criticisms of its notoriously over-energetic techno-adventurist restorations, the National Gallery ran a series of didactic, so-called “Making and Meaning” exhibitions. One such in 1996-97 was Rubens’s Landscapes. It was organised jointly by the Gallery’s then senior curator, Christopher Brown, and by its senior restorer, Anthony Reeve. The exhibition was sponsored by Esso UK plc and its chairman and chief executive, K.H. Taylor, expressed pleasure in being associated with “the quality of research and scholarship that are the Gallery’s hallmarks”. In turn, the then National Gallery director, Neil MacGregor, expressed gratitude to Esso for its generosity, for year after year, in enabling the Gallery to “present to the public recent research on how and why the pictures were made”. In a section on the rigorously high standards of professional panel making in 17th century Antwerp it was noted that panels were marked with their makers’ monograms and that the panel back of Rubens’s “Chapeau de Paille” portrait bore Antwerp’s coat of arms and the carved initials of its maker, Michiel Vriendt. However, with the Samson and Delilah no such assurance was offered. Instead, the reader seemingly learns – with a nod to the contrary testimony of Reeve and Bomford/Plesters (see Fig. 7 below) that “A particularly fine panel made for Rubens by an Antwerp panelmaker is that for the Samson and Delilah, painted about 1609 for Nicolaas Rockox…” But then, after a section reprising Reeve’s own 1982 Technical Bulletin account of the risks posed to such fine panels by fluctuations in humidity, comes an abrupt claim that “The Samson and Delilah was planed down to a thickness of about three millimetres and set into [sic] a new blockboard panel before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 and so no trace of a panelmaker’s mark can be found…”

Now, in Fig. 7 above we see two incompatible accounts that were made and published just a year apart in successive National Gallery Technical Bulletins. Which of the contrary pair might be taken by the public and future scholars to be the more reliable and trustworthy record? Reeve’s account had preceded that of Bomford/Plesters – he had seen and reported what he saw and knew. Brown must therefore have found himself in the unenviable position of having to choose between Reeve’s earlier account and the later contrary one of Bomford/Plesters. That is, he had either to accept that the picture came into the Gallery after it had been planed down by some unknown party at an indeterminate date and that Reeve had imagined and chronicled an entirely fictional panel comprised of “six [sic] horizontal oak planks, carefully planed and jointed”, or, recognising that Reeve of all people was unlikely to have confounded a new sheet of blockboard with an early 17th century Flemish oak panel and extol its technical virtues even among Rubens’s panels, or… what? What could Brown say of the Bomford/Plesters account when he was aware that the picture’s own dossiers contained the already widely press-reported and potentially explosive 1992 Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson report precisely challenging the Bomford/Plesters account? Could he go down the middle and say that while the picture had come into the gallery as a panel in good shape – as Reeve had testified – when subsequently taken into restoration, it had been planed down and glued onto (not “into”) a new sheet of blockboard – and do so without offering any explanation for such a radical and inescapably material and historical evidence-erasing procedure? In the event, Brown did neither. Rather, he fudged a technically-incoherent mongrel account even though he and Reeve were the exhibition’s joint authors. That is, on the one hand he spoke of the Samson and Delilah having been a “particularly fine panel made for Rubens by an Antwerp panelmaker” and then, leaving a gaping, mystifying narrative hole in his own account, jumped to “The Samson and Delilah panel was planed down to… etc. etc.” This was a curatorial equivalent of the old comic book cop-out gag “With one bound, Jack was free”. It is not easy to conclude other than that it had seemed institutionally imperative to dissemble rather than clarify.

8 March 2025.