Books on No-Hope Art Attributions

The latest addition to the fast-growing but least-estimable art book publishing genre – The Book of Art Attribution Advocacy – has finally arrived. It comes eight years late and on the second anniversary of Christie’s, New York, 15 November 2017 sale of the formerly attributed-Leonardo, Salvator Mundi picture – which disappeared the following day.

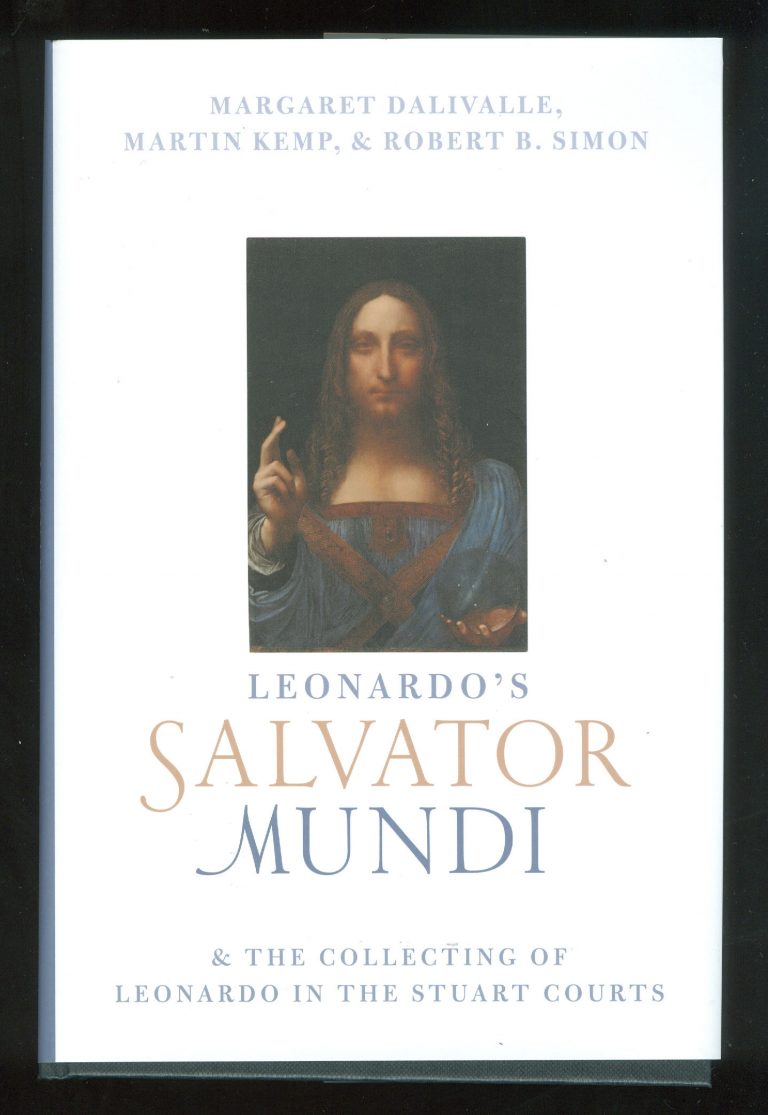

Fig. 1: The above book,Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts, constitutes the first official published account in support of the Salvator Mundi painting that was exhibited as an autograph Leonardo painting at the National Gallery in the 2011-12 exhibition, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan” (see Fig. 10) and that was sold at Christie’s two years ago for $450 million. The authors are: Margaret Dalivalle, a provenance specialist; Martin Kemp, Professor Emeritus and Leonardo specialist; and, Robert Simon, a New York art dealer and one of the two original buyers of the Salvator Mundi in 2005. The book contains no contributions by those who examined the painting technically and worked on its successive restorations. In their introduction and in defence of these startling omissions, the authors liken their book to a three-act opera: “However it is not intended to be an exhaustive treatment of the subject. As with an opera having a grand and intricate plot, this book will consider three facets of the story, each in depth, while necessarily bypassing many ancillary issues.”

There is no mention of the catcalls it has elicited. A glance at the illustrations shows the book to carry a new mystery: there would now seem to have been an undisclosed restoration.

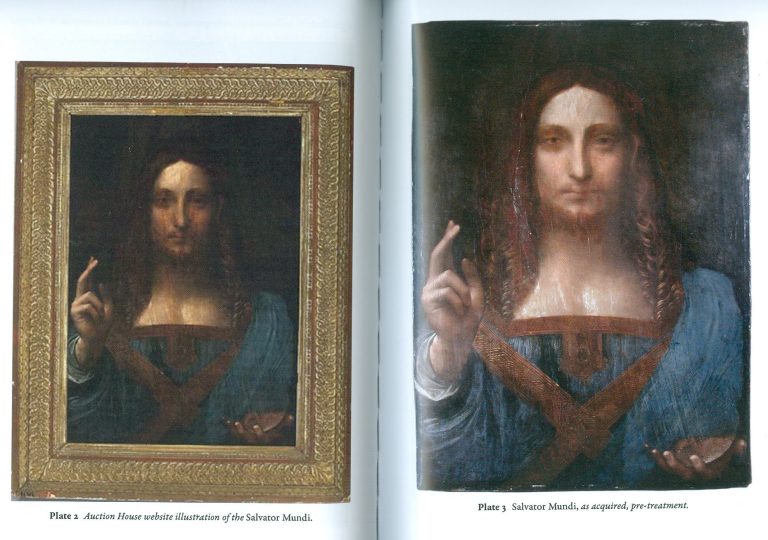

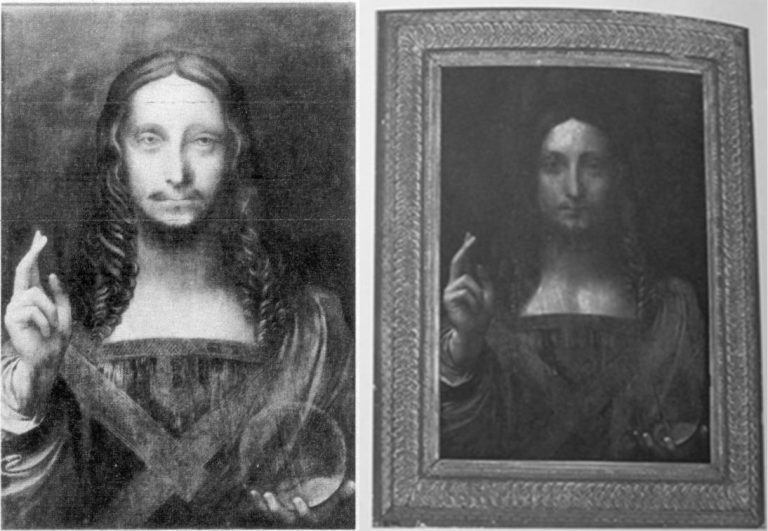

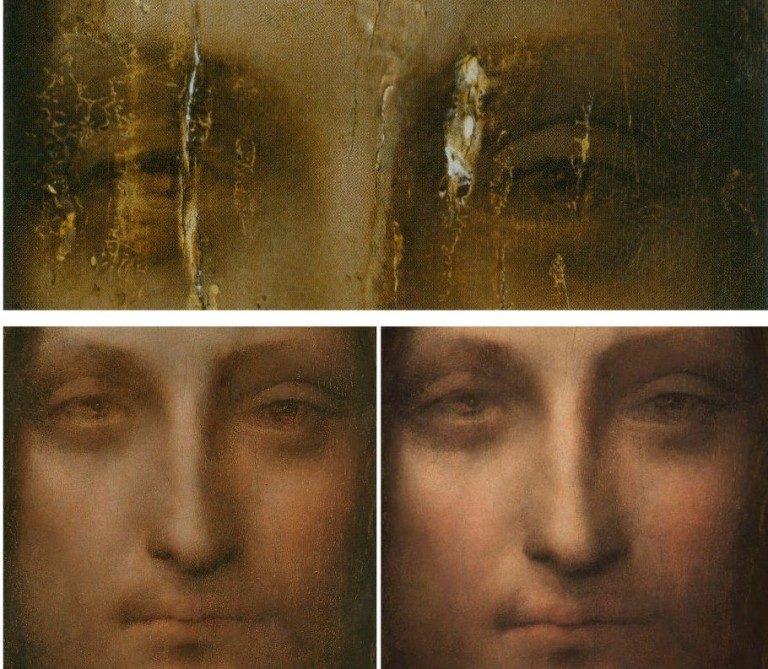

Above, Fig. 2: In this photo-spread, the first image shows the painting as illustrated by the auctioneers in 2005. The second image is said to show the picture as acquired by Robert Simon (and one other) at the auction. The restorer chosen by the new owners was Dianne Dwyer Modestini who worked on the painting in a number of restorations between 2005 and 2017. She has recalled (see Fig. 4) that when the painting was taken to her home in 2005 its surface was still sticky. The painting would thus seem to have been restored at some point after the sale catalogue was prepared and before it was taken to Modestini.

Above, Fig. 3: Simon Hewitt’s long-promised and compendious 2019 book (pp.352), Leonardo da Vinci and the Book of Doom, is written in support of the attributing to Leonardo of a mixed media drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Martin Kemp – and which remains unsold in a Swiss freeport. Now said by Hewitt to have been drawn by Leonardo in 1496 from Bianca Sforza, the illegitimate daughter of “Il Moro”, the 7th Duke of Milan, this book demonstrates – but does not expressly acknowledge – that no record of such a drawing exists before its sale at Christie’s, New York, in 1998 when it was sold as early 19th century German for $22,850 to a New York dealer who sold it on to Peter Silverman in 2007 for $19,000. In 2008 Silverman introduced himself to Hewitt by jumping into his cab saying: “May have a story for you one day! I’ll let you know.” In 2009 Silverman summoned Hewitt to Paris and a facsimile of “La Bella Principessa”. Having taken it at first sight to be early 19th century German, Hewitt produced an article for the Antiques Trade Gazette headed “Is this the greatest art market discovery of the century”.

Above, Fig. 4: Although Dianne Dwyer Modestini’s 2018 memoir, Masterpieces, is not strictly-speaking a book of art attribution advocacy, it contains as an epilogue, a chapter on the Salvator Mundi. In it, Modestini reproduces the photograph of the Salvator Mundi as shown in Fig. 2 above, right, and she describes it as being “as I first saw it in 2005”. We report in the ArtWatch UK Journal No. 32 (p. 47) how Modestini further commented on the picture in Masterpieces:

“When the Salvator Mundi returned to New York in July 2017 ahead of Christie’s November 2017 sale…having been instructed ‘not to inform anyone’ when the painting was ‘delivered to the Conservation Center [of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, where Modestini works as Senior Research Fellow and Conservator of the Kress program in Paintings Conservation] under guard and in great secrecy.’ Modestini writes approvingly of the fact that a deal brokered by Christie’s ahead of the sale whereby the vendor would receive at least $100million ‘was successfully kept under wraps’.”

For that late-stage re-restoration work in 2017, see Dalya Alberge, Mailonline, 22 December 2017, (“Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo da Vinci painting which became the world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in the last five years.”)

Above, Fig. 5: Although Martin Kemp’s 2018 Living with Leonardo is a professional lifetime memoir, he too includes chapters in support of the two Leonardo attributions he has championed – those of the Salvator Mundi and the mixed media drawing he dubbed “La Bella Principessa” that is owned by Peter Silverman – as seen above right. Kemp, like Hewitt, devotes much of his advocacy to attacking critics of the two attributions – including ArtWatch UK’s officers and associates.

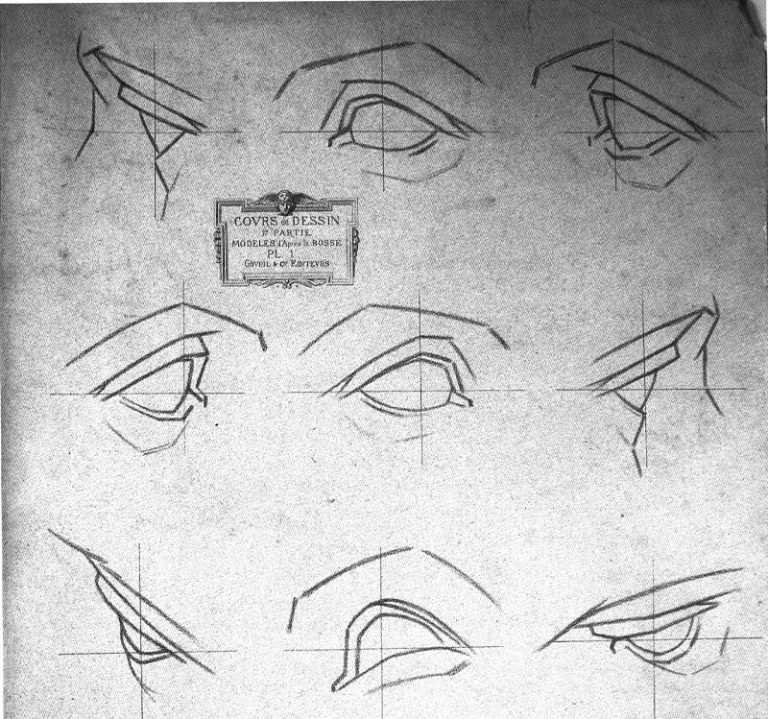

Above, Fig.6: Kemp’s publishers, Thames and Hudson, asked to reproduce a four-part graphic (top) which we had published on 3 May 2016 (“Problems with “La Bella Principessa” – Part II: Authentication Crisis”) precisely to demonstrate why, on stylistic grounds, the eye of “La Bella Principessa” could not possibly have been drawn by Leonardo. A crucial part of our cross-linked visual comparisons was an eye from a 19th century sheet of demonstrations to art students on how best to sketch eyes with short, straight lines. When Kemp’s book was published it carried a three-part diagram as shown above and as if it were the four-part one we had published. In Kemp’s reduced graphic, the embarrassing testimony of the guide to students had been omitted.

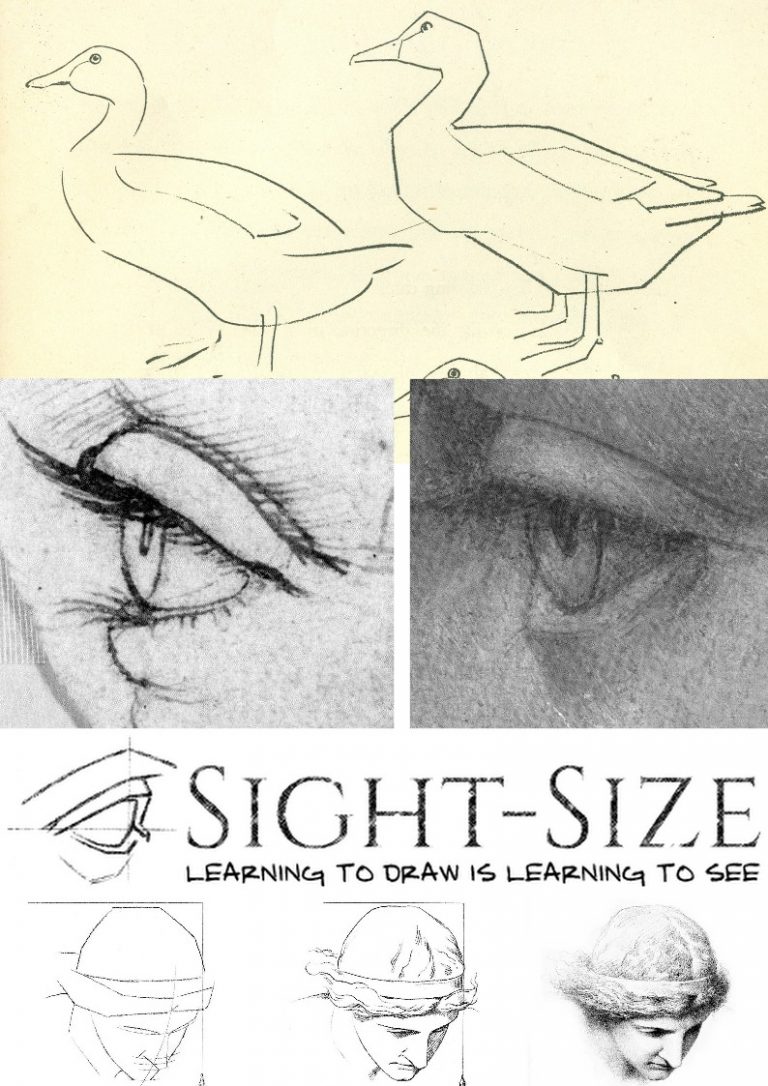

Above, Figs. 7 and 8: In the top image we show the sheet that had carried the eye which Kemp dropped. In the second image above we show (top) instructions in one of the “How to draw…” books, a guide to students on the relative merits of drawing ducks with curving lines or straight lines. Below it we show an eye drawn by Leonardo, with curving lines, and the eye of “La Bella Principessa”, drawn with straight lines. (As it happens, the eye that Kemp declined to publish is used as the logo for a drawing school – Sight-Size.)

Above, Fig. 9: This book of 2012 is something of a rarity within the genre of advocacy books in that it is written not by a professional art historian or art critic but by the work’s owner. It makes a fascinating and instructive read. We learn from the horse’s mouth, exactly who approached whom and when in the attempted formation of a sufficiency of experts to constitute an art-market “consensus of support”. We learn how Silverman planned his own media campaign to introduce both the work and its assembled supporters to the world. Such inside disclosures and resulting cross-linked accounts of the campaigning, can become sources of friction. In his 2018 memoir Kemp takes Silverman to task in a number of respects. Firstly (p.152), in terms of how the championing of the attribution should best have been managed:

“I had already written an extended report for Peter Silverman – longer than a standard academic article, shorter than a book. What I had seen and what I was gleaning from my continuing research persuaded me to write a book with Pascal [Cotte of Lumière Technology – see Fig. 11]…We also decided to include a short chapter by fingerprint specialist Paul Biro, who compared the inky fingertip with likely Leonardo prints. Ideally, nothing more should have appeared before our book [Kemp and Cotte’s, at Fig. 11] was launched. I was very concerned that the piecemeal, erratic and sensationalized release of incomplete stories was proving prejudicial. Early in 2009 I circulated a strategy to Peter and his supporters proposing that the drawing should be ‘exposed to a wholly non-commercial venue at the same time as all the research data had been released in full.’ I emphasized that all the material in the planned book should be embargoed before its publication. This placed considerable demands on Peter’s uneven reserves of discretion and patience…”

With so much cross-linking of players mishaps can arise. Members of tightly-knit groups of advocates can come collectively to see all opposition not as differing viewpoints but as quasi-pathological manifestations of “hostility” from rival “gangs”. For example, Hewitt reports:

“On July 1 Peter Paul Biro alerted Kemp and Cotte that the next edition of the New Yorker would be running a ‘potentially prejudiced and cherry-picked article about me, my work and the drawing.’ The New Yorker, he pointed out, was ‘owned by Condé Nast, which in turn is owned by Si Newhouse – a major client of Christie’s.’ ‘Christie’s and their friends are getting as much as they can in the public domain rubbishing the portrait and those who have worked on it’ replied Kemp – who had assured the New Yorker that Biro’s work on the [“La Bella”] portrait was exemplary.’ David Grann’s 16,000 word article on July 12th implied Biro was sleazy and incompetent. When Biro [unsuccessfully] sued the New Yorker for libel, a Federal judge paid implicit tribute to Grann’s verbal craftiness – declaring that his article did not make express accusations against Biro, or suggest concrete conclusions about whether or not he is a fraud.” Kemp, too, discusses Biro in his memoir:

“The strategy I had outlined fell apart when the fingerprint became the explosive subject of international attention before our book was published. Paul Biro, working from his studio in Montreal, compared Pascal’s amplified image of the fingerprint with prints in Leonardo’s unfinished St Jerome in the Vatican. Paul identified a print in the St Jerome which he saw as showing eight points of resemblance with that on the vellum. The most characteristic part of a fingerprint is the complex whorl at the centre of each fleshy pad. This was not apparent [– was not present?] in the print on the portrait which was made by the very tip of a finger. Paul’s ‘eight characteristics’ would not have been enough to secure a criminal conviction, but they were suggestive [of what?] and supportive. I could more or less see what he was seeing, if I tried hard, and I was happy to accept that he possessed a more expert eye for such things. [And besides:] The fingerprint evidence was a small part of the total fabric of evidence I was building up. But a ‘Leonardo fingerprint’ is news; it has a ‘cops and robbers’ dimension. The story was broken in the Antiques Trade Gazette by Simon Hewitt, a journalist with whom Peter had developed a trusting relationship. On 12 October 2009 the Gazette announced:

“‘ATG correspondent SIMON HEWITT gains exclusive access to the evidence used to unveil what the world’s leading scholars say is the first major Leonardo da Vinci find for 100 years…ATG have had exclusive access to that scientific evidence and can reveal that it literally reveals the hand – and fingerprint –of the artist in the work. The fingerprint is ‘highly comparable’ with one in the Vatican’.”

Kemp went on to say: “David Grann threw a lot of unpleasant mud at Paul Biro.” He then threw some of his own: “The source of much of the mud was Theresa Franks, founder of the Fine Art Registry, who had developed a reputation as an effective and litigious polemicist about the vagaries of the art world…The New Yorker piece was hugely damaging for Paul – and for the portrait, because our limited use of his evidence was used to taint the whole of the case we were making.”

Kemp’s remarks on Hewitt’s journalistic prowess might have disappointed the journalist/author whose book begins:

“INTRODUCTION

‘Is this the greatest art discovery of the century?’

“That was the front-page headline [he reproduces the front-page] in Antiques Trade Gazette on 17 October 2009, placed above my story about the portrait…It was one of the biggest stories of my career and, in terms of internet hits, the biggest story ever covered by the respected, if slightly fusty, art market weekly I had served on as Paris correspondent since 1985…”

Another attribution, another “gang” of opponents… Hewitt adds: “What Kemp dubbed ‘the New York gang’ were ‘almost bound to be hostile in an act of closing ranks, since they all missed it.’” Yet another is the “Polish gang”. Under a heading “POLES APART” Hewitt writes:

“Soon after Leonardo’s portrait of Bianca Sforza had gone on show in Monza, Katarzyna Pisarek [books editor of the AWUK Journal] published a 17,000-word article in Artibus & Historiae – a twice yearly journal edited by her Polish compatriot Józef Grabski, whose advisory committee included the Metropolitan Museum’s Everett Fahy (cited by Richard Dorment as a ‘vehement opponent of the Leonardo attribution’)…Pisarek was aping her Communist-era compatriot Bogdan Horodski, a former director of the Polish National Library…Pisarek harped on about Peter Paul Biro’s ‘dubious’ fingerprint evidence, omitting to mention that this had been removed as inconclusive from the second edition of the Kemp Cotte book…”

Hewitt seemed not to grasp the full import of the fact that an entire chapter of the Kemp/Cotte book had been excised. He pursued his Polish Conspiracy slur: “ ‘Why was Pisarek ‘suddenly so concerned to address this portrait when she had no record as a Leonardo scholar?’ wondered Martin Kemp. He presumed it ‘resulted from a kind of Polish solidarity’…On November 29 Waldemar Januszczak [Sunday Times art critic and TV broadcaster] – born in England to Polish parents…” and so on. Kemp/Cotte had had very good professional reasons to disassociate themselves from Biro. Kemp puts it with some delicacy in his memoir but the urgency is clear: “It transpired that Paul had previously achieved some notoriety in the detection of a purported Jackson Pollock discovered by a truck driver in a thrift shop. This discovery had been chronicled in a 2006 TV documentary, Who the #$&% is Jackson Pollock? Grann went on to tell a complex tale of Biro’s engagements with other Pollock authentications, in which the artist’s fingerprints appeared on paintings that were subsequently rejected by important Pollock scholars. It was alleged that Biro forged the Pollock fingerprints.”

In the first edition of the Kemp/Cotte book, the authors described the partial fingerprint as a full fingerprint in their introduction: “Following Lumière Technology’s discovery of a fingerprint and a handprint on the portrait, the authors turned to Peter Paul Biro, Director of Forensic Studies, Art and Access & Research, Montreal, to analyse this evidence in the context of what was known of Leonardo’s work…” And Kemp wrote (in his concluding chapter headed: “What constitutes proof?”): “…We have been able to detect extensive left-handed execution, not least in the layers below those we can see with our naked eye. Finger- and hand-prints have come to light in the way we have come to recognize as characteristic of Leonardo’s working methods. Indeed the isolated fingerprint near the left margin has strong if not conclusive evidential value that Leonardo himself touched the vellum.”

Above, Fig. 10: The catalogue to the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan”. Normally such a scholarly publication would not become ensnared in attribution controversies because public galleries do not, on principle, include privately owned, unpublished and un-attributed works without provenances that are on the market, but it did so with the Salvator Mundi – even though the identity of the picture’s by-then three owners (one of whom had bought-in with a $10 million stake) was undisclosed. Also undisclosed was: the venue at which the picture had been bought; the price at which it had been purchased; the identities of the leading scholars who were supposed to have endorsed the Leonardo attribution. Crucially, the supporters included the National Gallery’s director, one of its trustees and the curator and organiser of the Leonardo exhibition. The catalogue entry described the work as an autograph Leonardo painted prototype for the many similar Leonardo school Salvators that exist. Its author, Luke Syson, wrote: “This discussion anticipates the more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others. I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be presented in a forthcoming book.”

As mentioned above, that book has finally been published over eight years after the opening of the National Gallery exhibition and we now see that there are only three authors of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts: Margaret Dalivalle, Martin Kemp and Robert Simon. Modestini and Gutman-Rieppi have been dropped. In Living with Leonardo, Martin Kemp discusses the failure of Peter Silverman to get “La Bella Principessa” included in the National Gallery exhibition – on the organisation of which he (Kemp) had, at one point, been under consideration as co-curator:

“Looking back over the different fortunes of the attribution of the Salvator Mundi and the portrait of Bianca Sforza, there are some clear lessons to be drawn. The first concerns how a work of art enters the scholarly and public domains. Robert quietly introduced the Salvator Mundi to a judicious selection of experts, who – remarkably, given the usual leakiness of the art world kept their counsel for three years. By the time the painting emerged in public, there was a critical mass of influential voices who would speak in the painting’s favour. By contrast a series of incontinent leaks to the press, as happened with the Bianca prejudices a work in the eyes of specialist commentators. I regret that I did not have more influence on when and how La Bella Principessa emerged…

“Ownership also plays its role. The owners of the Salvator played their hand cleverly, fostering the idea that they wanted to do right by Leonardo’s masterpiece and were interested in it entering a public collection. Peter Silverman, on the other hand, has become a conspicuous presence in the art world…he has what is conventionally called ‘a good eye’. I believe that his intuition about the portrait of Bianca Sforza will be vindicated in the longer term, but unfortunately his variable declarations about its ownership, even if well-intentioned, did not induce trust and made him vulnerable to media criticism.”

This was in pointed contrast to Kemp’s view of Robert Simon:

“…Robert Simon, the custodian of the picture (whom I later learnt learned was its co-owner), outlined something of its history and restoration. He seemed sincere, straightforward and judiciously restrained, as proved to be the case in all our subsequent contacts…All of the witnesses in the [National] gallery’s conservation studio were sworn to confidentiality, and the painting travelled back to New York with Robert. It was becoming ‘a Leonardo’.”

Above, Fig. 11: The 2010 edition of Leonardo da Vinci, “La Bella Principessa” The Profile Portrait of a Milanese Woman. Since 2014 we have reviewed this work in the following posts:

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part I: The Look”

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part II: Authentication Crisis”

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part III: Dr. Pisarek responds to Prof. Kemp”

“Fake or Fortune: Hypotheses, Claims and Immutable Facts”

The day before the subsequently disappeared Salvator Mundi painting was sold at Christie’s, New York, we published a post explaining why the attribution was unsound and the provenance implausible:

“Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”

Weeks before the sale and before criticisms of the Salvator Mundi erupted in New York, we had spoken against the attribution in a Guardian interview – “Mystery over Christ’s orb in $100m Leonardo da Vinci painting”

Michael Daley, Director, 15 November 2019

The pear-shaped Salvator Mundi

Things have gone very badly pear-shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. It took thirteen years to discover from whom and where the now much-restored painting had been bought in 2005. And it has now taken a full year for admission to emerge that the most expensive painting in the world dare not show its face; that this painting has been in hiding since sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 for $450 million. Further, key supporters of the picture are now falling out and moves may be afoot to condemn the restoration in order to protect the controversial Leonardo ascription.

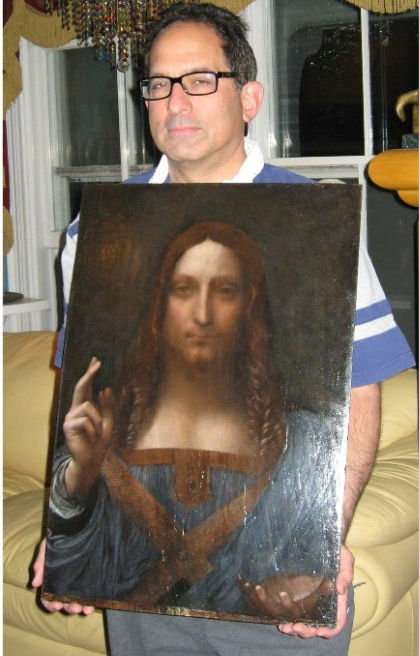

Above, Fig. 1: the Salvator Mundi in 2008 when part-restored and about to be taken by one of the dealer-owners, Robert Simon (featured) to the National Gallery, London, for a confidential viewing by a select group of Leonardo experts.

Above, Fig. 2: The Salvator Mundi, as it appeared when sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017.

THE SECOND SALVATOR MUNDI MYSTERY

The New York arts blogger Lee Rosenbaum (aka CultureGrrl) has performed great service by “Joining the many reporters who have tried to learn about the painting’s current status”. Rosenbaum lodged a pile of awkwardly direct inquiries; gained a remarkably frank and detailed response from the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini; and drew a thunderous collection of non-disclosures from everyone else. A full year after the most expensive painting in the world was sold, no one will say where it has been/is or when, if ever, it might next be seen. (See “Leonardo Canards: Conservator Dianne Modestini Debunks Doubts Over the Elusive ‘Salvator Mundi’”.)

After the Salvator Mundi’s recent no-show at Abu Dhabi Louvre, concerns and rumours have grown exponentially. (See our “Two developments in the no-show Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi saga” and “How the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi became a Leonardo-from-nowhere”.)

AN ENDURING SUPPORTER

Throughout this protracted no-show, Professor Martin Kemp, the most high profile art historical advocate of the painting’s Leonardo attribution, has offered assurances. Immediately ahead of the November 2017 sale he made a promotional video for Christie’s, New York, that was specifically designed to combat our and other warnings, warnings that he now characterizes in his self-valedictory memoir Living with Leonardo as “misinformation appearing in the press”. The Times reported on 28 August: “‘looking at the whole science’ including the rock crystal sphere that Christ was holding and the depth of field convinced [Kemp, that] ‘with Leonardo you have this wonderful body of context, of extra evidence…it is rock solid, it is damaged but rock solid’.” Kemp frequently fuses appeals to rock solid scientific evidence with art critical hyperbole. For example, to the owner of the supposed Leonardo drawing “La Bella Principessa”, he said of a partial finger print:

“This is yet one more component of what is as consistent a body of evidence as I have ever seen. I will be happy to emphasize that we have something as close to an open and shut case as is ever likely with an attribution of a previously unknown work to a major master. As you know, I was hugely sceptical at first, as one needs to be in the Leonardo jungle, but now I do not have the slightest doubt that we are dealing with a work of great beauty and originality that contributes something special to Leonardo’s oeuvre. It deserves to be in the public domain.”

So far as we know, that supposed Leonardo drawing (which the National Gallery excluded from its 2011-12 Leonardo show) remains unsold in one of Yves Bouvier’s freeports. Kemp recently assured the world that wonderful things are in train for the Salvator Mundi next year. Against his bullishness, the picture’s long-serving restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini, has now disclosed to Rosenbaum: “I have no idea about the future of the painting. No one does. Not the French, not Martin Kemp. I assume the people from Abu Dhabi know something, but they are not talking to anyone, not even the French.”

Rosenbaum had tried the Louvre, Paris:

“I thought the venerable French museum would at least be able to answer my question regarding its own exhibition plans, but Sophie Grange of the Louvre’s press office said only this: ‘It is too early, one year ahead, to communicate on the list of the loans for the Louvre exhibition. Concerning Louvre Abu Dhabi, they communicate themselves about their own collection.’ Grange advised me to get in touch with Faisal Al Dhahri at Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism—one of the three officials whom I’d already attempted to contact several times, to no avail. I think this is called: ‘Getting the Run-Around.’”

THE GOOD THINGS TO COME

Kemp may have had in mind the forthcoming 2019 Louvre exhibition to mark the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death but no one at the Paris Louvre will now confirm that the Abu Dhabi Louvre Salvator Mundi will be included. Is Paris about to spurn Abu Dhabi’s $450 million acquisition? Failure to include the work next year would risk humiliating the United Arab Emirates (who paid something like Euros 400 million for the right to exploit the Louvre title – roughly the cost of one big yacht) when French foreign policy dictates every deployment of soft cultural power to gain influence in that traditionally Anglophile quarter.

…AND THE UNKOWN UNKNOWNS

Why are so many players so silent on this painting? Why is the art world being kept in this state of darkening paralysis? Some background might help explain the jitters. The art market greatly fears the pending trial in New York between Sotheby’s and the Russian collector Dmitry Rybolovlev who seeks $380 million from the auction house for an alleged conspiracy to defraud him through his own adviser, Yves Bouvier. In 2013 Sotheby’s brokered a private sale of the Salvator Mundi for $80 million to Bouvier, the owner of a string of “tax-efficient” freeports – his Geneva facility alone reputedly holds $100 billion of art. The consortium of vendors claimed that a non-disclosure agreement made with Sotheby’s preventing them from disclosing the picture’s origins. Bouvier immediately sold the painting on (“flipped” in art trade parlance) to Rybolovlev for $127.5 million – an undisclosed mark-up of $47.5 million, with Sotheby’s, reportedly, pocketing $3 million as an agent’s fee. The Swiss police authorities recently detained Rybolovlev for questioning due to “reported allegations of corruption and ‘influence peddling.’ Rybolovlev is allegedly tied to Philippe Narmino, the former justice minister in Monaco, who retired last year after he was accused of working under the influence of the Russian collector in his fraud case against Bouvier…” Earlier, Rybolovlev had filed a complaint against Bouvier in Monaco. The latter was arrested on charges of fraud and money laundering and released on $10 million bail. Bouvier is now reported to be in Singapore. With Rybolovlev furious at being over-charged in 2013, the consortium of vendors who sold indirectly to him for $80 million are thought to remain aggrieved at being short-changed by $47.5 million on the picture’s value and having been pre-emptively blocked from action by a Sotheby’s law suit. Sotheby’s are reportedly seeking assistance from Christie’s in a separate legal fight with a dealer over the sale of a demonstrably and now scientifically-confirmed fake Frans Hals…

THE ART AND ATTRIBUTION STAKES

Unsavory art market churning must not swamp the serious art and attribution concerns at stake with this Salvator Mundi. Modestini’s reported statement to Rosenbaum merits close reading. Her first concerns are the painting’s physical condition, well-being and whereabouts:

“It’s supposed to have been in Switzerland, but I’m not quite convinced, because a conservator who was asked to make a condition report more than a month ago still hadn’t seen it as of last Monday [22 Oct. 2018]. I’m rather worried because although it was framed in a microclimate, it is not a long-term solution. I’m pretty sure it left Christie’s in mid-May. Then it disappeared. It never went to Abu Dhabi… However, the panel is badly damaged and exceptionally reactive to changes in RH [relative humidity]. It needs to be at not less than 45% RH, even though it has some protection because it’s in a microclimate created by sealing it up in an envelope of Marvelseal —a standard technique.”

Modestini’s second concern is professional and personal:

“The Abu Dhabi announcement [that it had postponed display of the painting] had nothing to do with the nonsense about its being 85% by Dianne Modestini and the rest by [Bernardino] Luini. [The Luini theory, advanced by Leonardo scholar Matthew Landrus, was reported by Dalya Alberge in the Guardian and picked up by Smithsonian Magazine, among others.]”

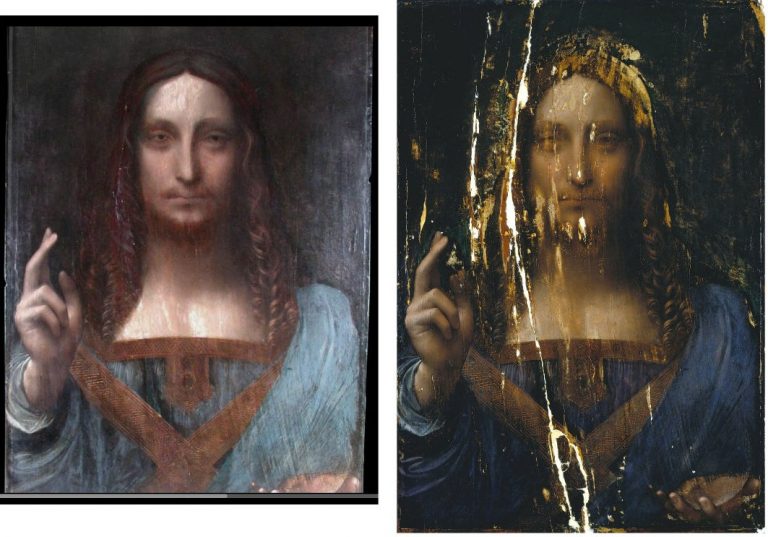

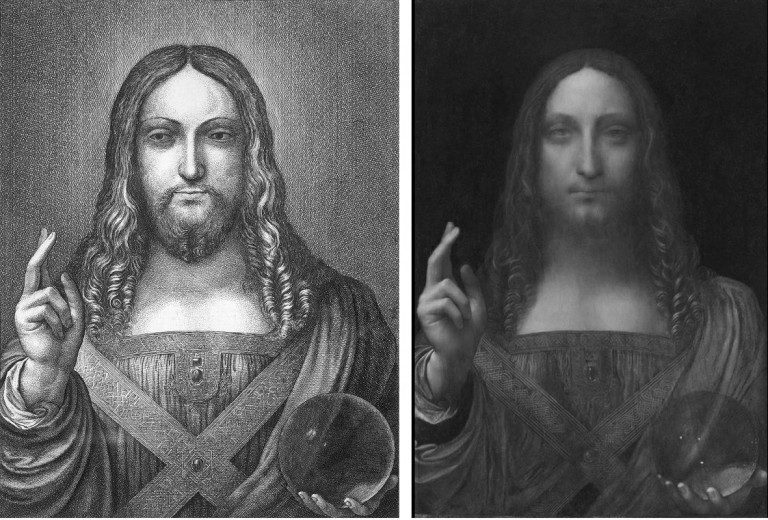

Above, Fig. 3: Left, the Salvator Mundi as restored in 2008; right, a National Gallery painting attributed to Bernardino Luini.

A GREAT FALL-OUT?

It is understandable that Modestini should be sensitive and defensive – no professionally conscientious person enjoys criticism. Following our demonstrations of the extent to which the painting changed appearances at her hand (albeit on the advice of and with support from a high-ranking group of art historical experts) between 2005 and 2017, there are now signs that art historical advocates of the Salvator Mundi may be preparing to disavow the successive restorations to protect the credibility of their attribution. Consider Jonathan Jones’ recent (15 October) account in the Guardian – “The Da Vinci mystery: why is his $450m masterpiece really being kept under wraps?”

Jones, who was the embedded journalist-of-choice within the National Gallery’s conservation department when its version of the Virgin of the Rocks was being restored, bluntly contends that it might have been better if the Salvator Mundi had not been restored at all:

“Surely it would have been more true to the greatest artist who ever lived to let his timeworn masterpiece speak to us directly. Is the Louvre Abu Dhabi taking a closer look? I think it should.”

In this maneuvre, Jones seems to draw support from Martin Kemp, who, along with a few other select experts, had been invited by the National Gallery’s incoming director, Nicholas Penny, to the confidential 2008 viewing of the Salvator Mundi when part repainted, as at Fig. 1:

“When the painting was cleaned, it turned out that Christ had two right thumbs… ‘Both thumbs,’ says Kemp of the raw state, ‘are rather better than the one painted by Dianne.’”

Kemp will likely have known that Modestini had painted out the restoration-exposed second thumb on the advice of Luke Syson, the curator of the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition in which Kemp had been set to have some curatorial input until, as he puts it: “it was later decided that all the curation should be conducted in-house”. Modestini acknowledged Syson’s guidance in her (2014) published account of her restorations preceding the painting’s appearance in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition. Syson, who went to the Metropolitan Musem, New York, has recently been appointed director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. It is possible that had Kemp been co-curator, the National Gallery Leonardo show would have included a second Kemp-supported Leonardo upgrade, the “La Bella Principessa” drawing. In any event, an emboldened Jones has now challenged Robert Simon, one of the original consortium of dealer-owners: “Why didn’t he leave the painting in its raw yet beautiful state after it was stripped down? Wasn’t that an incredible object in itself?” Simon stood firm:

“We considered leaving it, considered more limited restoration, as well as a more extensive one…In the end we decided to do what we felt was best for the picture…we felt that bringing it back to life as much as possible was the way to go.”

Jones reports Simon’s annoyance with criticisms of the restoration – he absolutely rejects the possibility of any artistic “falsehood” being introduced. “I found [Thomas Campbell’s] comments both ill-informed and offensive. ‘Inpainting’ is the right way to describe what has happened here – retouching restricted to areas of loss. In the restoration no original paint was covered.”

(When the picture was sold in November 2017 Thomas Campbell, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum, presciently tweeted that he hoped the anonymous buyer who had just paid $450m “understands conservation issues” and had “read the small print”.)

WHAT WAS DONE IN THE SALVATOR MUNDI RESTORATIONS

The claim never to have over-painted is universally asserted by restorers. While no code of restoration “ethics” sanctions painting over surviving original paint, the profession’s philosophical pieties constantly conflict with observable visual facts. We have previously shown that if you juxtapose halves of the two Salvator Mundi faces, as seen in 2011-12 at the National Gallery and at Christie’s in November 2017 (see Fig. 7 below), there is a mismatch: scarcely any passages of painting run across the halves. As the photo-records below testify, this version of the many Leonardesque Salvator Mundis has enjoyed two distinct identities in seven years and three in ten years. We discuss the unreported covert transition from the second to the third below.

DISPARAGING PHOTO-TESTIMONY

Modestini and Kemp are united on one point: both hold that restorers cannot be held to account by photo-comparisons of the alterations they make to works of art. The claim is untenable – how else might appraisals of restorations be made given that pre-restoration appearances are consumed in restorations? Both the restorer and the art historian further contend that photographs are inherently unreliable because susceptible to malicious manipulation. Modestini offers this variation on that ancient restoration slur:

“I have refrained from commenting on some of the recent articles about the restoration. However, in light of the fact that no one can now see the actual painting, various digital images are standing in for the original, all of which can be manipulated any way one wants and are a sort of falsification of the original.”

That is unworthy. First, why would anyone maliciously tamper with images to make false claims of non-existent injuries that could easily be exposed by the photographic record? How long did it take to expose the Trumpian White House’s tampering with film footage of a journalist’s attempt to retain a microphone? Second, does Modestini mean to imply that the clear photographically recorded differences between the painting’s 2011 and 2017 states are the combined result of malicious critics and auction house promotional manipulations? Modestini’s citation of the second plank of the traditional Restorers’ Defence – that all photographs of paintings are inherently untrustworthy and misleading – is scarcely more credible:

“It is very difficult to photograph any painting accurately, this one especially, because of the many thin layers, subtlety of skin tones, delicacy of transitions etc. Most paintings have three dimensions, not two. That affects our perception of them. I hardly recognize the image that now passes for the ‘Salvator Mundi.’ The photo lamps or strobes (in the case of the Christie’s images) produce a simulacrum of the actual painting, more vivid, sharper, snazzier, if you will, than the actual battered image that I restored as carefully as I could, trying not to invent anything. These flashy images cannot include the nuances and problems created by the three dimensionality of the corrugated surface and are being compared with an only slightly more accurate scan of a good 8×10 transparency of the cleaned state, which was more honest.”

That last image (here at Figs. 5-10) has been published with a drum roll by Jones in the Guardian as if a proof of Leonardo’s hand when it had been published by Modestini in 2014 (albeit small and in printed not online form). Although a considerable improvement on earlier versions (as published by us) it does not tell a different story. On the Jones premise, will Modestini now produce equally high-resolution photographs taken before and after each of her various interventions (2005-08; 2008-11; post 2012 and pre-2017)? If she insists that all photographs are inherently untrustworthy and easily falsifiable, will she explain why so many photographs of paintings are made and published and why they never carry visual health warnings? Are all photographs previously made for restorers’ own restoration reports now deemed to be unreliable testimony?

THE ART CRITICAL UNDERPINNING OF THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S CHANGING APPEARANCES

We incorporate below the Guardian’s newly released high definition photograph of the painting when cleaned but not-yet repainted within the public record of Modestini’s restorations and then consider Kemp’s scientific/art theoretical input into the restoration in the light of certain accounts in his new memoir, Living with Leonardo – Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond. But first, the changes to the painting:

Above, Fig. 4: Left, the photograph of the Salvator Mundi painting when in the Cook collection and judged to be a work of Bernardino Luini; right, the former Kuntz family and then Basil Clovis Hendry Sr. estate painting, as in the 2005 St. Charles Gallery catalogue.

Above, Fig. 5: Left, a screen grab of the Salvator Mundi as when taken, still sticky from a previous restoration in 2005 to Dianne Modestini’s New York studio; right as in 2007 in the newly released high-resolution photograph following cleaning and repairs to the panel but before any retouching, infilling or repainting. Will Modestini publish a photograph of the painting as presented to her in 2005?

Above, Fig. 6: Left, the Salvator Mundi as in 2006/7 (in high-resolution) after cleaning; right, as in 2011 as exhibited as a Leonardo at the National Gallery, London, and after much repainting – some of which was distressed and contained false, painted lines of cracking in emulation of aged paint cracks.

Above, Fig. 7: Left, the Salvator Mundi as in 2006/7 (in high-resolution) after cleaning; right, as in 2017 when sold at Christie’s, New York, after further covert restoration.

Above, Fig. 8: Left, the head of the Salvator Mundi as in 2006/7 (in high-resolution) after cleaning; right, the head in a split screen compilation showing the appearance in 2011 on the left and in 2017 on the right.

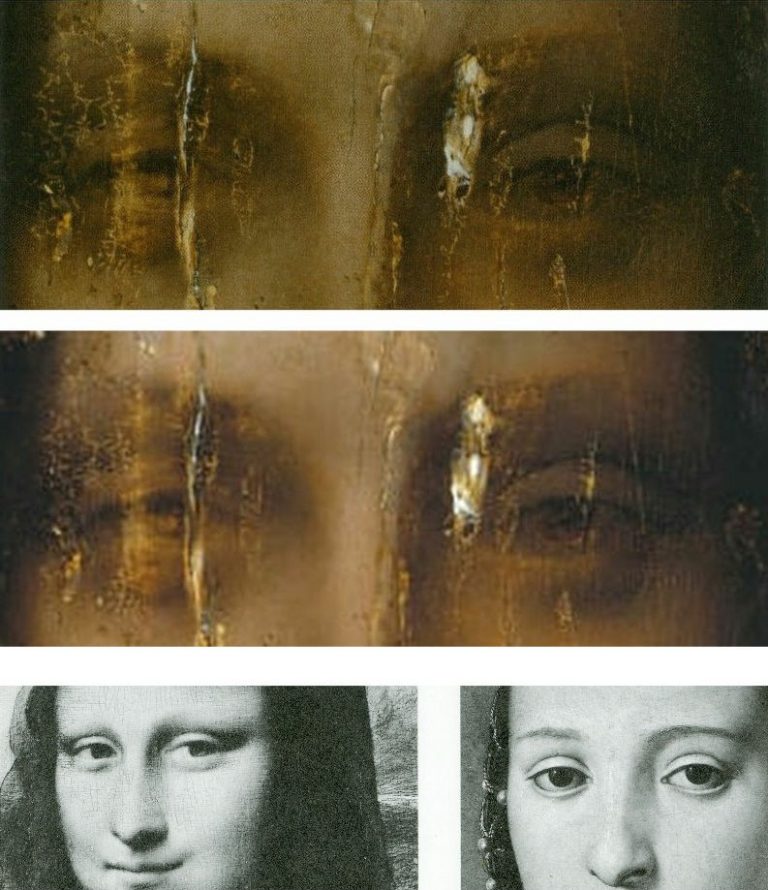

Above, Fig. 9: Top, a detail of the Salvator Mundi’s eyes as in 2006/7 after cleaning and before repainting (and as published by Modestini in 2014); above, left, the face, in 2011, and, right, as in 2017.

Above, Fig. 10: Top, a detail of the new high resolution photograph, as published online by the Guardian; centre, the corresponding detail as published by Modestini in 2014, the previously best detail of the cleaned and not-yet repainted eyes; above, eyes by Leonardo and Bronzino. The lower images are surely instructive here? The Salvator Mundi was hyped by Christie’s, New York, as an iconic thing – a “Male Mona Lisa”. Martin Kemp holds that it was painted by Leonardo after he had painted the Mona Lisa and that he had deliberately put the face “out of focus” so as create spiritual mysteriousness on the one hand and an illusion of spatial depth and recession in an emphatically flat (and heavily cropped composition) on the other. If we look at these images art critically we can safely make a number of factual, verifiable observations – and these are not “subjective”. First, although the high-resolution photograph is superior as a photograph to the lower resolution image, as published in a book, it does not tell a materially or artistically different story – in both we can see the extent of losses and the fact the treatment of the eyes is neither identical nor consistent. In particular we can see that the treatment of the heavy flattening upper eye lid on the right is sharply (and badly) drawn, while that on the left is softer and almost undoubtedly abraded. Modestini somehow equalized the effect of the eyes while leaving the implausible severity of drawing found in the lid of the eye on the right. Neither eye in this painting is remotely comparable with the Mona Lisa’s eyes where softness of effect has been achieved without loss of sculptural lucidity or anatomical veracity. These differences are ones of quality more than of style. The creases formed by the meeting of the soft flesh of the upper lids with the more taught flesh of the brow is more sharply drawn in the Bronzino but it is also drawn with greatly more acuity and finesse than the eye on the right of the Salvator Mundi. Much of the great benefit photography brings to art historical scholarship lies in the ease with which detailed style comparisons can be made. In an age of high quality and electronically transmissible photography, if you are going to claim Leonardo you really should take the opportunity to demonstrate Leonardo.

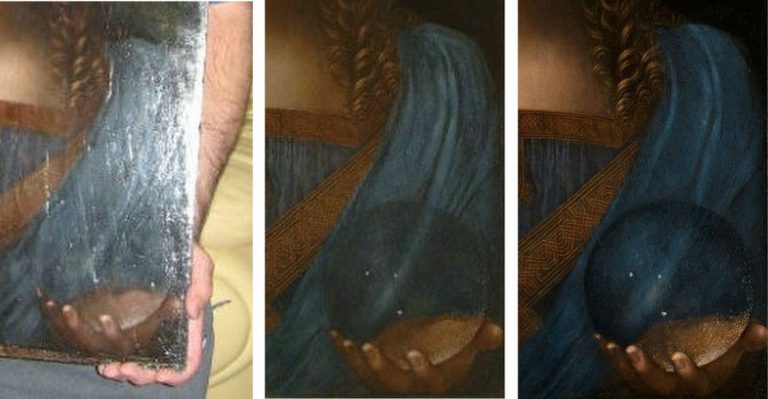

Above, Fig. 11: A succession showing the picture and two details, with the first each time, as in 2011 and, second, as in 2017. The question raised by Modestini is the extent to which the differences shown above are products of Christie’s own “more vivid, sharper, snazzier” images of the 2017 state or of her own repainting. It can safely be said that repainting must substantially account for the differences because changes have been made to the design of forms as can be seen here in the comparison of the details of the shoulder drapery. It would be helpful if all parties to the post 2005 “conservation treatments” would publish full accounts of them accompanied by the best available photo-records.

MARTIN KEMP’S THEORETICAL AND SCIENTIFIC INPUT

On the very day when the Salvator Mundi went on exhibition at the National Gallery (9 November 2011) Kemp published an article, “Art History: Sight and salvation” in Nature magazine. In it, he made a number of significant contentions/observations: 1) that although connoisseurship still has a role to play, it involves “subjective criteria that should long ago have been superseded as the key tool of attribution”; 2) that art historical evidence can be supplemented by “the scientific”, of which there are two kinds – technical examinations of pictures’ component material parts, and scientific evidence that is “particular to Leonardo”; 3) that the Salvator Mundi bears such witness in two regards: it “plays with depth-of-field problems. None of the contours is absolutely sharp, but the blessing hand and the tips of the fingers cradling the orb are discernibly clearer than the features of Christ’s face. The rapid lack of clarity in depth serves to give space to what would other-wise be a quite flat image.”

What is striking in the above series of comparisons is the extent to which Modestini has apparently added force and clarity to the hands and globe in the foreground. The globe, for example, has been emphatically darkened towards its circumference and lightened at its centre between 2011 and 2017. Modestini partially accounted for these changes in 2014: “The rock crystal orb, symbolizing the cosmos, was painted with practically nothing, thin glazes and scumbles which unfortunately have been abraded, especially along the top of the wood grain. Originally the illusion must have been magical since simply toning down the lighter areas with translucent watercolor glazes rendered it convincing.”

In Living with Leonardo Kemp discusses the two thumbs and, there, had praised Modestini’s “painstaking and diplomatic filling in of lost areas with readily soluble paint”. Kemp reports that after viewing the picture at the National Gallery in 2008 “Robert and I corresponded during the course of that summer and autumn.” There can be little doubt that differences between the painting’s appearance, when first taken to London (Fig. 1), and later in 2011 when exhibited in London (Fig. 2) are considerable. Even more dramatic are the differences between 2011 and 2017. The question, then, is under what or whose ambition or programme, were Modestini’s changes made? Was she and/or the owners in thrall to Kemp’s quasi-photographic depth-of-field thesis? We know from her own account that she made a number of artistic changes to the painting with a view to increasing spatial force:

“I repainted the large missing areas of in the upper parts of the painting with ivory black and a little cadmium red light, followed by a glaze of rich warm brown, then more black and vermilion. Between stages I distressed [how?] and then retouched the new paint to make it look antique. The new color freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair and made a different, altogether more powerful image.”

Note: these are only the changes that were made between 2007 and 2011. There has been no account of the subsequent restorations. If we look at the top of the split-image of the face at Fig. 8, we can see that the hair immediately to the right of the parting had become much darker by 2017 while the flesh tones in the forehead and nose had become lighter. No account of these changes has been published.

REFRACTIONS OR PENTIMENTI?

To return to Kemp’s 2011 Nature article, where he made this account:

“The other optical effect is unique to this painting, both in Leonardo’s work and in the Renaissance more generally. The orb is not the standard globe of the world. It is translucent and glistens internally with little points of light. These are not the spherical bubbles found in glass, but are the kind of cavity inclusions (small gaps) that appear in some specimens of rock crystal and calcite. Leonardo, we know, was considered an expert in such semi-precious materials. It seems that he observed the double refraction produced by calcite. The Heel of Christ’s hand exhibits two distinct contours, not in this case due to a change of mind.” [Emphasis added.]

That could not be clearer, could it? In Kemp’s characteristically adroit fusion of the technical and the spiritual, the superseding of traditional subjective practices of connoisseurship by newer, more astute technically and scientifically-informed analysis might seem well demonstrated – but how are such formulations to be evaluated? Must scholars without scientific backgrounds simply defer to the supposed superiority of science-loaded art historical scholarship – if told, on cited geological authority, that a material is so and so and, therefore uniquely gives rise to such and such effects, (that is, if calcite, then be on the lookout for its double refractions) who might query or dissent? Seven years later, in Living with Leonardo, Kemp retells his story on the significance of the orb and its near magical optical properties as a concrete embodiment of Leonardo’s mind, but with a twist: “The most satisfying aspect of my own research concerned my hunch that the globe was made of rock crystal”; he had “toyed with the idea that the double image of the heel of Christ’s right hand might be the result of the double refraction characteristic of rock crystal; but the optics would not work. The apparent doubling is almost certainly another pentimento [i. e. change of mind in the design – emphasis added].”

Thus, without a blush, Kemp offers a new diametrically opposite rationale: with this orb Leonardo “was not making a ‘portrait’ of an actual sphere, nor was he following all its optical consequences to their logical conclusions.”

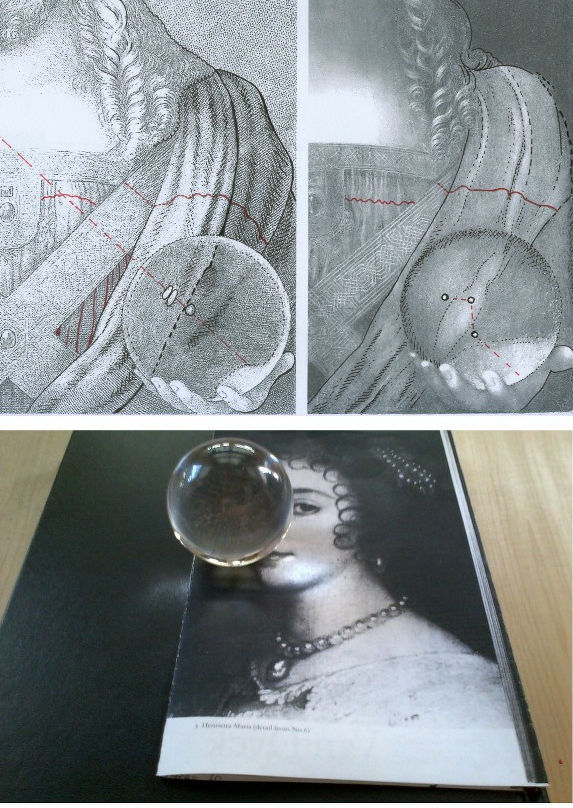

Without mention of Hollar’s testimony, a pragmatic explanation is offered for an intellectual flip: “the optics” were put to the test and it was found by due and diligent research that they “would not work”. By “would not work” Kemp suggests that his efforts with a real crystal orb to replicate the kind of refraction he had earlier claimed to recognise in the double image of the hand holding the orb had been unsuccessful. But might there not have been another reason for dropping the earlier refracted hand thesis? As mentioned, Kemp’s Nature article appeared on the day the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition opened, 9 November 2011. On 11 November, a correspondent asked in the Times why no optical deflections were evident in Christ’s globe. The next day the Time’s carried our letter (Fig. 12, below) pointing out that in an etched copy by Wenceslaus Hollar of the original but now lost Leonardo Salvator Mundi the drapery seen through the orb had been deflected.

For the National Gallery this was politically awkward: if Hollar had copied an optically sophisticated, characteristically Leonardesque, effect from a painting then attributed to Leonardo that was not present in the painting on exhibition as the original Leonardo from which Hollar had made his copy, this could only mean that Hollar’s copy had, in fact, been made from another painting. Worse, on a careful visual reading of the relationships between the etching and the Salvator Mundi painting in the exhibition, there were further grounds for drawing the same conclusion: Hollar’s Christ was stouter and heavily bearded; his face was long and it tapered inwards from the level of the eyes, it did not widen, chipmunk-like towards the jaw; the eyes looked slightly to our left, not directly at the viewer; a radiant halo-like light emitted from Christ’s head; the transparent orb had gathered light around its circumference – and not grown darker, as in the painting…

This problematic visual mismatch must have compounded political problems: the gallery’s decision to exhibit a proposed Leonardo of little provenance and no art historical or technical literature and that was in the hands of a group of dealers (and therefore, inevitably, on the market) was institutionally questionable and certainly controversial. It became the more so when at least four Leonardo scholars challenged the attribution of the painting. Kemp, at that point, was hoist on his own scientific petard. Where the gallery had claimed in its catalogue entry on the painting that “There could be no doubt that this is the picture that was copied by Hollar”, it was now evident that it could not have been – and without that claimed connection, the picture’s supposed provenance collapsed from one in which it had passed down to us first through the French royal family in Leonardo’s day and then to the English royal family in the 17th century… to one that only began in England in 1900 when it had emerged from no acknowledged source, with no history and only as a painting given to Luini. How would the gallery respond to this very public correspondence and challenge? How would Professor Kemp respond? The National Gallery made no reply to the letters in the Times perhaps judging silence to be a better defence than open art critical engagement. Professor Kemp, too, was silent in the public prints, so far as we know.

Above, Fig. 12: Two ArtWatch UK letters to the Times.

Seven years later, while the National Gallery remains silent, Kemp, in Living with Leonardo, now writes with patronising verve and confidence to a new position:

“We should remember that Leonardo was drawing on his knowledge of rock crystal to devise a large sphere [the former ‘orb’ or ‘globe’] for Christ to hold – he was not making a ‘portrait’ of an actual sphere, nor was he following all of its optical consequences to their logical conclusion. I have been asked on more than one occasion why the drapery behind the sphere is so little affected by what is, in effect, a large magnifying lens. The answer, in a word, is decorum; that is to say, pictorial good manners…Leonardo’s endowing of Christ with a rock crystal sphere was not just a case of optical and geological cleverness for the sake of it…”

Perhaps not, but then why not introduce into the discussion the visual/artistic fact that Hollar had copied a deflection of curved forms of drapery when seen through a curved transparent body symbolising the cosmos? Would a copyist have invented an optical distortion in a painting he believed to be an autograph Leonardo? In journalism, as supposedly in science, facts are held sacred and opinions somewhat less so. Are awkward facts expendable in science-rich art history? Properly considered, Hollar’s testimony is an important event in the history of scientific engagement in art – just as it had been in Holbein’s use of an optic to correct the anamorphosis in the foreground skull of The Ambassadors in the National Gallery – as a scholar had proposed in the 1970s and I had corroborated in the 1990s. How long will such testimony remain institutionally and professionally un-personned?

SOME FURTHER UNADDRESSED, PHOTOGRAPHICALLY RECORDED ARTISTIC FACTS:

Above, Fig. 13: Left, a section of drapery in the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi when exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011-12; right the Modestini-changed section of drapery when sold at Christie’s New York in 2017.

Above, Fig. 14: Left, Hollar’s 1650 engraved copy of a Salvator Mundi attributed to Leonardo that shows deflected folds of drapery within the transparent orb; right, the Abu Dhabi Louvre Salvator Mundi as seen at the National Gallery at the time of the above correspondence in the Times. The double edge of the hand holding the orb had been left in place on the then Kempian view that it demonstrated Leonardo’s sophisticated optical knowledge. Had that double image been judged a pentimento it would, like that encountered on the thumb of the raised true right hand, likely have been painted out by Modestini on the advice of the National Gallery curator, Luke Syson.

Above, Fig. 15: Changes made to the Salvator Mundi’s orb and adjacent draperies as seen respectively (from left to right) in 2008, 2011 and 2017.

Above, Fig. 16: Left, the 1650 Wenceslaus Hollar etched copy of a Salvator Mundi painting; right, the Abu Dhabi Louvre Salvator Mundi, as seen in 2017 with changed draperies. In the Hollar we can how the central, highlighted fold of drapery is deflected from its convex path into a concave formation as it runs through the centre of the orb and between the aligned double and single light reflections. We can see how the heel of the copied hand was smaller and deflected towards the circumference of the orb; right, in the Louvre Abu Dhabi painting (third state) we can see how Modestini had darkened the circumference of the orb and brightened the interior. It is simply inconceivable that as skilled a copyist as Hollar could have drawn his orb from this, now Louvre Abu Dhabi painting.

Above, Fig. 17: Top, two diagrams showing differences of design and modeling between the 1650 Hollar copy, left, and, right, the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as sold in 2017. The three reflected highlights in the Hollar orb are aligned in accord with the picture’s top-left down light source which is evident throughout the painting that Hollar copied. The three unaligned white spots in the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture were attributed by Modestini to “reflections on the sphere to an outside source, but since many of the original glazes have perished, even when toned down, they float with context.” Above, a glass sphere owned by the author that shows the pushing of light towards the circumference, as copied by Hollar.

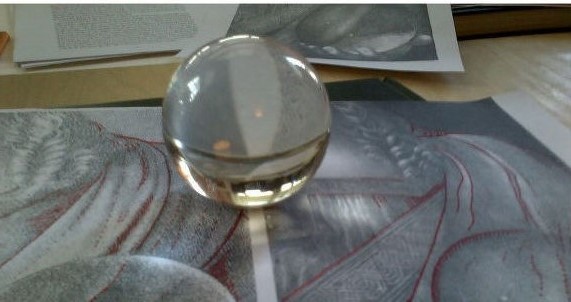

Above, Fig. 18: The author’s glass sphere. Where Martin Kemp failed to locate a double refraction in a small rock crystal orb, we demonstrated, as above, that when parallel straight lines (as here in the white gap between two photocopy diagrams) are viewed through a glass orb they are deflected into curves.

THE HOLLAR GLOBE’S BETTER FIT WITH THAT FOUND IN THE DE GANAY SALVATOR MUNDI<

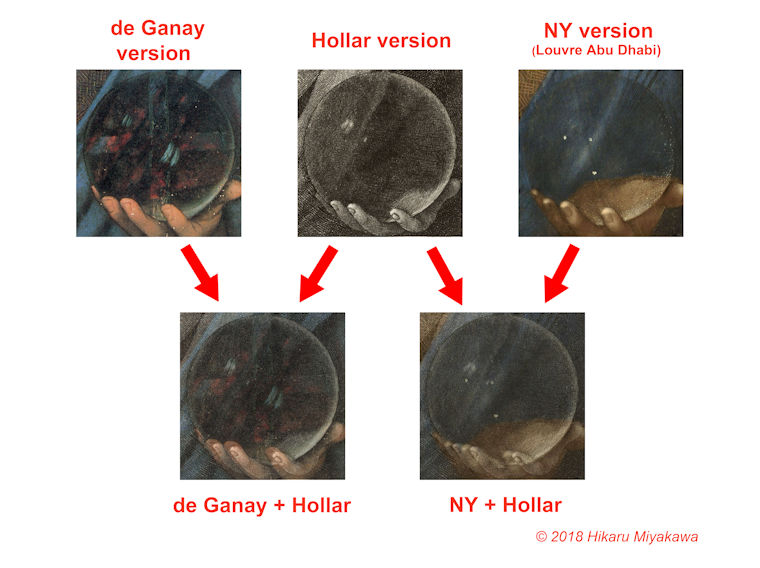

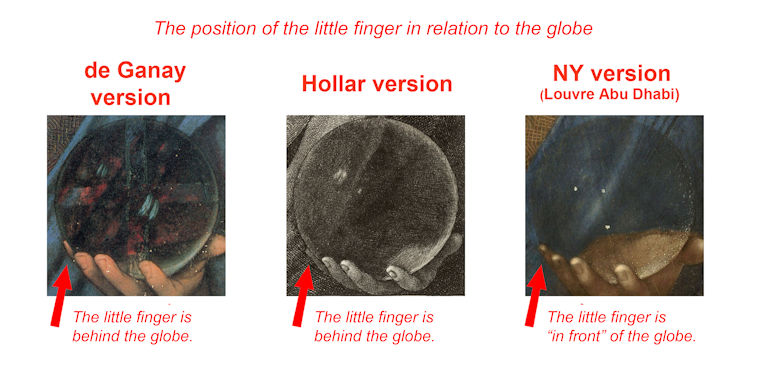

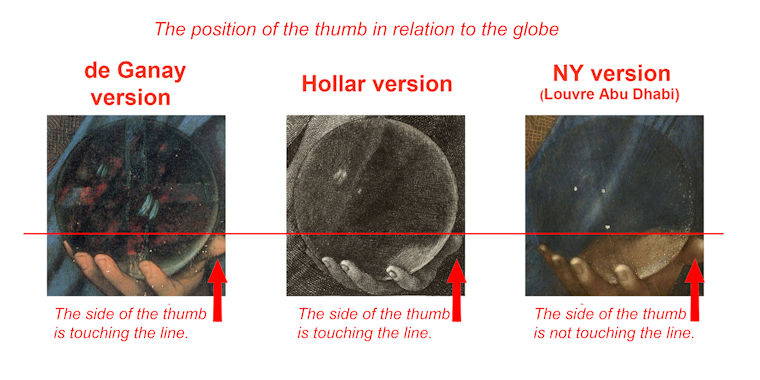

In our previous post the painter Hikaru Hirata-Miyakawa showed through the three graphics below that in addition to all the above problems with the suggestion that the Hollar engraved copy had been made from the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture, the globe copied by Hollar bears a much closer relationship to the globe found in another Leonardesque painting, the so-called de Ganay Salvator Mundi, than to the globe seen in the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi.

Michael Daley, 12 November 2018