SALVATOR GRUMPI – UPDATED

The July/August issue of the Art Newspaper carries three fascinating items on the standing of the disappeared Salvator Mundi painting which may or may not be included in the forthcoming Leonardo exhibition at the Louvre.

It was sharp of the Art Newspaper to spot the inconsistency (above, left) at the Queen’s Gallery exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing”. Two months ago, the Guardian reported that Martin Clayton, head of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, had said that while some experts still doubt its authenticity: “For what it’s worth, I believe it is [a Leonardo].” He then made this extraordinary claim:

“My opinion is not a controversial one among Leonardo scholars … the more somebody knows about Leonardo the more likely they are to accept the painting and the people who have been saying ‘no, Leonardo would never paint anything like that’ tend to be people who, to be frank, aren’t great Leonardo scholars.”

This seemed both ill-informed and rash. Does Clayton take himself to be a better judge of Leonardo matters than say – just to name two prominent Salvator Mundi dissenters – Carmen Bambach, curator of Drawings and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and author of the recently published four-volume study Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered, or, Frank Zöllner, author of the Leonardo catalogue raisonné? Contrary to claims made by the National Gallery and Christie’s, the author Ben Lewis has disclosed in his book The Last Leonardo that when the Salvator Mundi was examined at the National Gallery in 2008 – in one of its earlier restoration incarnations – only two out of five leading Leonardo scholars endorsed the then proposed Leonardo attribution.

Tonight Martin Clayton chairs a discussion at the Queen’s Gallery with the experts, Adam Rutherford, Maya Corry and Matthew Landrus, on the ways Leonardo understood observation and drawing while combining art and science in every aspect of his work. The event is a sell-out and, unfortunately, the Gallery declined to admit ArtWatch to cover the event for our forth-coming Journal on the theme “From Sistina to Salvator”.

Michael Daley, 4 July 2019

Update, 10 July 2019 – ATTRIBUTING UP AND ATTRIBUTING DOWN

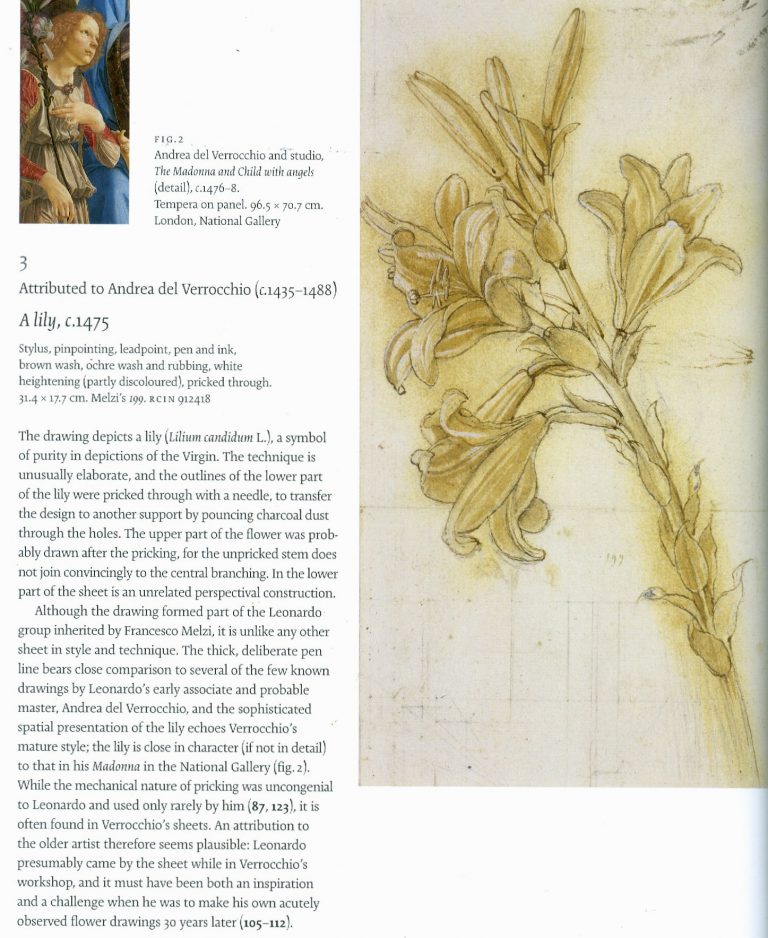

Two ArtWatchers’ present at the (£15) Leonardo observation/drawing/science discussion, report that in the “Leonardo da Vinci – a Life in Drawing” exhibition catalogue, Martin Clayton takes the c. 1475 drawing, A Lily, from Leonardo and attributes it to the artist’s master, Andrea del Verrocchio, on the grounds that the drawing bears “close comparison to several of the few known drawings” attributed to Verrocchio (Fig. 1 below). The claim goes unsupported visually. Clayton has reportedly acknowledged that:

“The Royal Collection has one less Leonardo drawing, but we have one more Verrocchio, which is even more exciting. This is our only Verrocchio. We don’t have any other drawings by [him]” and “Whereas his sculpture and architecture is very well known, very few of his drawings survive. We have something like 1,000 artistic drawings by Leonardo, whereas we have about 10 – if that – by Verrocchio [worldwide]. So, in a sense the subtraction of one drawing from Leonardo’s oeuvre matters hardly at all, whereas the addition of one drawing of Verrocchio’s is a big deal. That’s why I find it exciting… It is one of the most beautiful of his few drawings.”

For those who care about works of art as art – and not as quasi-philatelic holdings – it matters a very great deal. Consider the logic: if we re-attribute a (fabulous) Leonardo plant study and place it among Verrocchio’s very few drawings it becomes…one of the latter’s most beautiful drawings. That is an alarm bell – it should look at home in the oeuvre. In answer to the question how comfortably or plausibly the Lily sits among Verrocchio’s few drawings, Clayton’s case is twofold. First, “Leonardo’s earliest drawings do not feature the bold, confident line seen here”; then, an acknowledgement/assertion that although there is “no direct parallel in the few known drawings by Verrocchio, this penwork is close to that in his Head of an Angel and the double-sided Study of Putti”. And, for that reason: “An attribution to Verrocchio of this accomplished drawing thus seems preferable.”

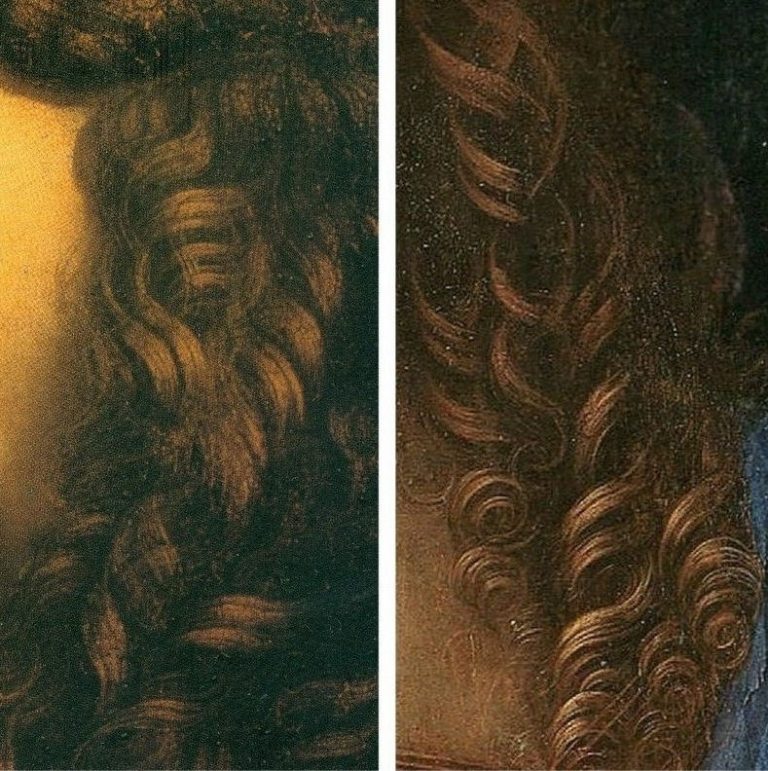

“Preferable” is an odd word in this context and is not the same thing as “more secure”. Moreover, if we juxtapose the details of the Leonardo Lily and the Verrocchio angel (as above at Fig. 2) we do not find a common bold line or a common anything. The drawing of the hair has none of the fluency of design or eloquent plasticity of the Lily. I first encountered the Lily at sixteen in a regional art school library Phaidon book, (probably Goldscheider’s Leonardo da Vinci). Then, I found it and Leonardo’s drapery studies breath-taking in their acuity and realisation of form-on-a-flat-surface. I still do. In Verrocchio’s oeuvre, the Lily is both atypical and most beautiful. This should not surprise: above grace and elegance, in this particular drawn stalk of flowers Leonardo had summoned a force of nature in an image that pulsates with life as it unfurls before us (Fig. 3).

Clayton’s principal justification for making his dramatic demotion is that the Lily constitutes a unicum within Leonardo’s surviving drawings oeuvre. It does but, then, it constitutes a more pronounced one in Verrochio’s tiny oeuvre. In making this switch Clayton discounts earlier scholarship on the drawing’s special status. Ann Pizzorusso kindly points out that while acknowledging the drawing’s distinctive nature, the late Carlo Pedretti had seen no disqualification. In Leonardo da Vinci Nature Studies from the Royal Library at Windsor Castle Pedretti noted that in nearly every one of his early paintings, Leonardo addressed landscape and “in particular” vegetation – where “Plants and flowers are consistently represented with scientific accuracy…” Moreover, “Evidence of Leonardo’s extensive study of plants and flowers in his youth is provided by Leonardo himself as he records ‘molto fiori ritratti di naturale’ in the list of works that in about 1482 he was taking to Milan or leaving in Florence…”

Whatever administrative benefits this effective de-attribution may bring, it neither rests on visual demonstration nor makes artistic sense. In our view, Clayton has thus committed a double Leonardo attribution error: he takes the now disappeared, much-restored and re-restored $450 million Salvator Mundi as a fully autograph Leonardo prototype painting and, he gives away one of Leonardo’s most brilliant studies. In both exercises methodological shortcomings are evident: neither the re-attribution nor the attribution upgrade followed a due presentation of evidence and invitation to debate. With the Salvator Mundi it is claimed that the (surviving) hair constitutes proof of Leonardo’s hand. It does nothing of the sort. Martin Kemp, the painting’s most vocal advocate, places the Salvator Mundi between the Mona Lisa and the St. John – in other words, at the very peak of Leonardo’s painterly accomplishment. In the comparison below (Fig. 4) we show details of the hair of the St. John, left, and the Salvator Mundi, right. By comparison with the secure St. John, the hair of the Salvator Mundi can be seen to be less sumptuously formed, more linear, sharper and metallic – like lathe turnings. The differences of painterly sophistication in these two works greatly outweigh any similarities of design.

Where the Lily seems to have been downgraded by a single scholar’s proclamation, with the Salvator Mundi, as Ben Lewis* has chronicled in his book, The Last Leonardo – The secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, the attribution was made through a cumulative series of covert manoeuvres between 2005 and 2011, at which late date the painting was sprung on the world with the full authority of a National Gallery director, curator and trustee, as an entirely autograph Leonardo painted prototype in the Gallery’s major Leonardo Painter at the Court of Milan blockbuster exhibition. To Lewis, Luke Syson, the exhibition curator, admits erring in his catalogue entry on the painting (which was indebted to the then – and still – unpublished papers of one of the owners). Specifically, Syson confesses: “I catalogued it more firmly in the exhibition as a Leonardo because my feeling was that I was making a proposal and I could make it cautiously or with some degree of scholarly oomph”. Nothing indicated to the reader or the exhibition visitor that a proposal was being made. As Syson put it in his entry: “The re-emergence of this picture, cleaned and restored to reveal an autograph work by Leonardo, therefore comes as an extraordinary surprise.” No “ifs”, no “buts”, this was a long-lost Leonardo. On which claimed certainty, see our review of Lewis’s book in “Selling a Leonardo with ‘oomph’” in the July/August 2019 issue of the Jackdaw.

A CURATE’S EGG OF AN ATTRIBUTION

In March 2008 five Leonardo scholars were invited to examine the Salvator Mundi in its then state of restoration. Martin Kemp has reproduced the emailed invitation he received from the Gallery’s then director, Nicholas Penny:

“I would like to invite you to examine a damaged old painting of Christ as Salvator Mundi which is in private hands in New York. Now it has been cleaned, Luke Syson and I, together with our colleagues in both paintings and drawings at the Met, are convinced that it is Leonardo’s original version, although some of us consider that there may be [parts?] which are by the workshop. We hope to have the painting in the National Gallery sometime in March or in April so that it can be examined next to our version of the Virgin of the Rocks. The best-preserved passages in the Salvator Mundi panel are very similar to parts of the latter painting. Would you be free to come to London at any time in this period? We are only inviting two or three scholars.”

In the event, five scholars were invited, and, Ben Lewis has established, of those, two accepted the attribution, one rejected it and two declined to offer a judgement. Kemp did accept it and he has further disclosed that: “All of the witnesses in the conservation studio were sworn to confidentiality, and the painting travelled back to New York with Robert [Simon, one of the consortium of owners who had bought the painting for $1,175 in 2005]. It was becoming ‘a Leonardo’.” And so it was. Having done so and having twice been sold as such for a total of over half a billion dollars, it disappeared. Its whereabouts remain unknown.

*Ben Lewis will deliver the tenth ArtWatch International James Beck Memorial Lecture (“Fingers Crossed: Wishful Thinking, White Lies, Benedictions and the Attribution of the Salvator Mundi”) in London, on Tuesday October 1st. Details to be announced shortly.