IN THEIR OWN WORDS: No. 1 – Civilisations and Burrell Loans

It’s official: the BBC remake of Kenneth Clark’s highly acclaimed television series Civilisation is an intellectually incoherent artistically obtuse “right-on” mish-mash. It is official: Glasgow is repeatedly dicing with Burrell’s bequeathed art for financial peanuts and supposed profile enhancement.

NICE PICTURES, POOR WORDS

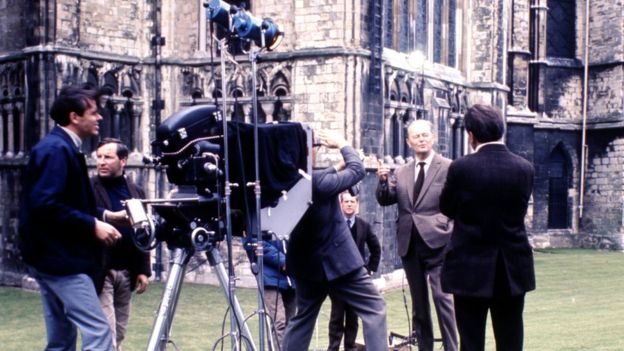

Above, top, Kenneth Clark shooting on the still-acclaimed 1969 series Civilisation; above, Simon Schama fronting the scathingly-received 2018 multi-voiced Civilisations outside Itimad-ud-Daulah’s Tomb in Agra, Uttar Pradesh.

“…By adding a single pluralising letter to the classic BBC art history series Civilisation (1969), the programme makers of Civilisations opened up the tantalising possibility of producing a new TV series that didn’t simply match its singular predecessor, but was much better.

“You can see the sense in the idea. Instead of an old-fashioned, patriarchal, white, western, male view of human cultures and creativity, why not make a show that acknowledges there are different civilisations and different views, which can be put across by different presenters? (In this case, three TV-ready, scarf-wearing academics: Mary Beard, David Olusoga and Simon Schama.) …from the programmes I have seen, Civilisations is more confused and confusing than a drunk driver negotiating Spaghetti Junction in the rush hour.

Above left, Aphrodite of Menophantos, Praxiteles, (4th Century BCE), Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome; above, right, Hand Stencils found in the Cave of El Castillo in Spain.

“The series starts with Schama – who has ‘always felt at home in the past’ – showing us library footage of an Islamic State wrecking crew in Mosul destroying ancient art and artefacts.

“He tells us the grisly story of how they brutally murdered the 82-year-old Syrian scholar Khaled al-Asaad for withholding information from them as to the whereabouts of the antiquities under his curatorial care in Palmyra.

“‘The record of human history brims over with the rage to destroy,’ the historian tells us with his passion dial turned up all the way to 11 (it rarely dips below 10).

“There is no mention made of similarly barbaric acts that have taken place over millennia – on occasion perpetrated by a civilisation much closer to home – or an explanation as to the cultural rationale behind the actions of those wielding the sledgehammers in this instance.

“…Music swells, titles roll, and we’re off – back to the beginning and the caves of South Africa, where we are shown a 77,000-year-old block of red ochre with the ‘oldest deliberately decorative [human] marks ever discovered’.

“This is ‘the beginning of culture’, Schama tells us, but he doesn’t dwell. Moments later we’re travelling through time and space like Doctor Who in a sci-fi remake of Treasure Hunt, touching down around 40,000 years later in northern Spain to visit El Castillo Cave.

“Here, both the programme and the presenter start to settle down and enjoy what they’ve brought us to see: cave paintings and hand stencils.

“Apparently similar images have been found ‘as far apart as Indonesia and Patagonia’, which is interesting. But then frustrating as no explanation is forthcoming to enlighten us as to why that might be.

“We are told: ‘These hand stencils do what nearly all art that would follow would aspire to. Firstly, they want to be seen by others. And then they want to endure beyond the life of the maker.’

“Really? Was that actually the motivation behind our stencil-making ancestor? Was he or she honestly most concerned with artistic ego and posterity? Were the painted hands even intended as art? Could they not have been a functional way-finding device or a ritualistic mark or part of a magical spell?

“…These are patchwork programmes with rambling narratives that promise much but deliver little in way of fresh insight or surprising connections.

Above, Mary Beard fronting Civilisations at the Colossi of Memnon in Luxor, Egypt.

“Mary Beard’s episode, How Do We Look, is particularly disappointing because the premise is so enticing, as is the prospect of one of our foremost thinkers on matters cultural giving us a new perspective.

Sadly, other than a couple of memorable TV moments when Beard encounters an ancient statue for the first time, we are offered little to excite our imaginations.

We don’t get the alluded-to update on Clark’s Eurocentric views or on John Berger’s Walter Benjamin-inspired Ways of Seeing series.

There is no substantial new polemic with which to wrestle. Instead we are served a tepid dish of the blindingly obvious (art isn’t just about the created object but also about how we perceive it), and the downright silly (an ancient story about a young man who supposedly ejaculated on a nude sculpture of Aphrodite thousands of years ago, which Beard describes with great theatricality as rape – ‘don’t forget Aphrodite [the stone statue] never consented’).

Above, David Olusoga fronting Civilisations with Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“David Olusoga is altogether more measured and less mannered than his fellow presenters. His two films – one exploring the meeting of cultures between the 15th and 18th Centuries, the other looking at the enlightenment and industrialisation – benefit from his inquisitive nature and relaxed style.

“If the scripts in the series are far from being literary masterpieces, the camerawork is of the highest quality throughout – although there are too many stylised shots of out-of-focus presenters with their backs to us.

“But when trained on art and artefacts, the new technology and techniques at the 21st Century TV director’s disposal provide us with plenty of delicious visual treats (the images from Simon Schama’s trip to Petra are stunning).

“Ultimately though, Civilisations feels like a series made by committee: a terrific-sounding idea on paper that I suspect was a lot harder to realise in practice.

“The result is a well-intentioned, well-funded series that has top TV talent in all departments but which ended up being less than the sum of its parts. A case of too many cooks, maybe?”

– Will Gompertz, the BBC’s art editor (Will Gompertz review: Civilisations on BBC Two 3 March 2018).

NICE PICTURES, NEEDLESS MULTIPLE RISKS

Above, Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal (1874) CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

“Fascinating details about a tour of the Burrell Collection’s late 19th-century French paintings have been revealed. Financial data on touring exhibitions is normally highly secret, but the Burrell’s data has been recorded in a report for a Glasgow City Council meeting on Thursday (8 March). This meeting is expected to approve the exhibition loans.

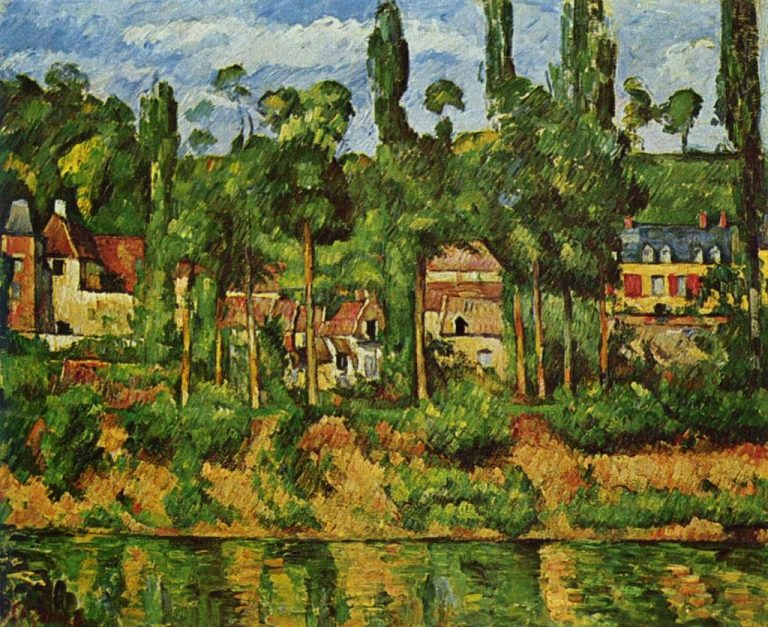

“A group of 58 works is being lent to the Musée Cantini in Marseille, which reopens on 18 May after refurbishment. The council report values the 47 paintings and 11 works on paper at £180.7m. The pictures include Degas’s The Rehearsal (around 1874) and Cézanne’s The Château of Médan (around 1880).

“Although the Japanese tour will be larger, with 55 paintings and 25 works on paper (including seven non-Burrell works from Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum), the value of the loans will be lower: £141.8m.

“What is even more interesting [is] the complex financial details of the deal. No fee is being paid by the Musée Cantini, but a sponsor is assisting the Burrell. It will contribute €100,000 towards the exhibition costs and €50,000 towards the Burrell’s refurbishment costs. The Art Newspaper understands that the sponsor is likely to be the London-based financial advisors Rothschild & Co and its new Marseille banking partner, Rothschild Martin Maurel.

“The Japanese tour, which will go to five venues from this October to January 2020, is being financed on a different basis. Each venue is paying a hire fee of £30,000, plus £1 per visitor after the first 100,000. If, for the sake of argument, each venue attracts 150,000 visitors, then the full total from Japan would be £400,000 (plus €50,000 for the French venue).

“When the tour idea was first considered, five years ago, the Burrell hoped to raise many millions from a touring exhibition, but this target has proved much too ambitious. James Robinson, the director of the Burrell Renaissance project, says that ‘profile raising for the Burrell and for Glasgow is just as important as the funding’.

“The Burrell Collection… building is now in need of a fundamental refurbishment. The cost of the refurbishment project is estimated at £66m, which means that the touring shows may bring in around 1% of the total. Glasgow City Council is to provide up to half the £66m and the Heritage Lottery Fund has awarded £15m, with contributions from other donors.

“Under the terms of Burrell, who died in 1958, his works could not be lent abroad because he was concerned about transport risks. In 2014 the Burrell trustees obtained special approval from the Scottish Parliament to enable them to lend abroad. The collection’s works by Degas are currently on loan to London’s National Gallery, until 7 May.

“The Burrell Collection closed for refurbishment in October 2016 and is due to reopen in late 2020.”

– Martin Bailey, “Revealed: the profits of staging a touring exhibition”, The Art Newspaper, 5 March 2018

Above, Cézanne, Château de Médan (1880) CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Michael Daley, 5 March 2018

Coda: For our earlier words on the overturning of the terms of Burrell’s bequest, see:

“Protecting the Burrell Collection ~ A Blast against Risk-Deniers”;

Leave a Reply