Books on No-Hope Art Attributions

The latest addition to the fast-growing but least-estimable art book publishing genre – The Book of Art Attribution Advocacy – has finally arrived. It comes eight years late and on the second anniversary of Christie’s, New York, 15 November 2017 sale of the formerly attributed-Leonardo, Salvator Mundi picture – which disappeared the following day.

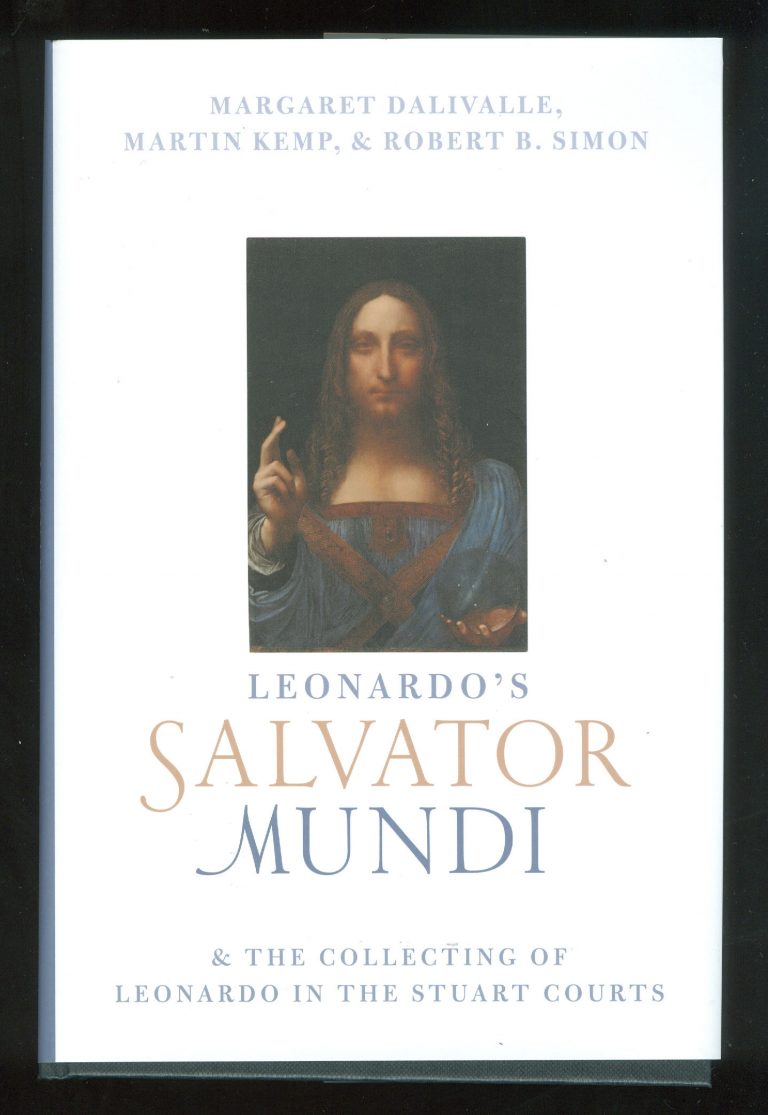

Fig. 1: The above book,Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts, constitutes the first official published account in support of the Salvator Mundi painting that was exhibited as an autograph Leonardo painting at the National Gallery in the 2011-12 exhibition, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan” (see Fig. 10) and that was sold at Christie’s two years ago for $450 million. The authors are: Margaret Dalivalle, a provenance specialist; Martin Kemp, Professor Emeritus and Leonardo specialist; and, Robert Simon, a New York art dealer and one of the two original buyers of the Salvator Mundi in 2005. The book contains no contributions by those who examined the painting technically and worked on its successive restorations. In their introduction and in defence of these startling omissions, the authors liken their book to a three-act opera: “However it is not intended to be an exhaustive treatment of the subject. As with an opera having a grand and intricate plot, this book will consider three facets of the story, each in depth, while necessarily bypassing many ancillary issues.”

There is no mention of the catcalls it has elicited. A glance at the illustrations shows the book to carry a new mystery: there would now seem to have been an undisclosed restoration.

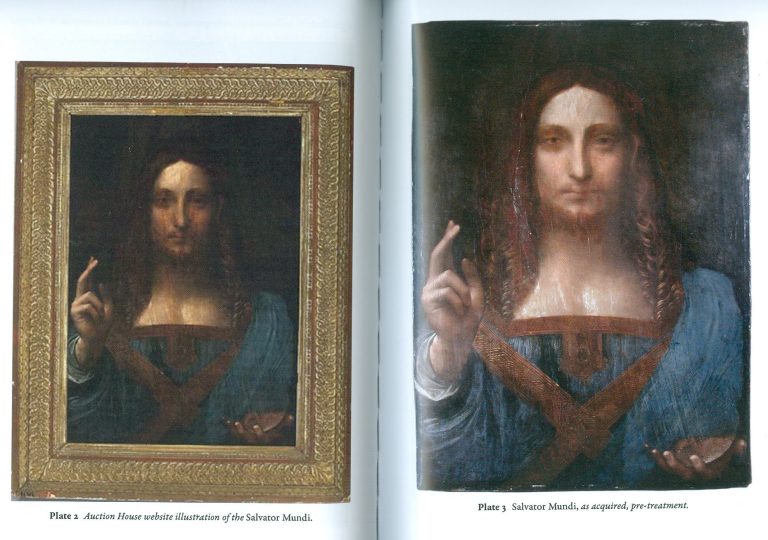

Above, Fig. 2: In this photo-spread, the first image shows the painting as illustrated by the auctioneers in 2005. The second image is said to show the picture as acquired by Robert Simon (and one other) at the auction. The restorer chosen by the new owners was Dianne Dwyer Modestini who worked on the painting in a number of restorations between 2005 and 2017. She has recalled (see Fig. 4) that when the painting was taken to her home in 2005 its surface was still sticky. The painting would thus seem to have been restored at some point after the sale catalogue was prepared and before it was taken to Modestini.

Above, Fig. 3: Simon Hewitt’s long-promised and compendious 2019 book (pp.352), Leonardo da Vinci and the Book of Doom, is written in support of the attributing to Leonardo of a mixed media drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Martin Kemp – and which remains unsold in a Swiss freeport. Now said by Hewitt to have been drawn by Leonardo in 1496 from Bianca Sforza, the illegitimate daughter of “Il Moro”, the 7th Duke of Milan, this book demonstrates – but does not expressly acknowledge – that no record of such a drawing exists before its sale at Christie’s, New York, in 1998 when it was sold as early 19th century German for $22,850 to a New York dealer who sold it on to Peter Silverman in 2007 for $19,000. In 2008 Silverman introduced himself to Hewitt by jumping into his cab saying: “May have a story for you one day! I’ll let you know.” In 2009 Silverman summoned Hewitt to Paris and a facsimile of “La Bella Principessa”. Having taken it at first sight to be early 19th century German, Hewitt produced an article for the Antiques Trade Gazette headed “Is this the greatest art market discovery of the century”.

Above, Fig. 4: Although Dianne Dwyer Modestini’s 2018 memoir, Masterpieces, is not strictly-speaking a book of art attribution advocacy, it contains as an epilogue, a chapter on the Salvator Mundi. In it, Modestini reproduces the photograph of the Salvator Mundi as shown in Fig. 2 above, right, and she describes it as being “as I first saw it in 2005”. We report in the ArtWatch UK Journal No. 32 (p. 47) how Modestini further commented on the picture in Masterpieces:

“When the Salvator Mundi returned to New York in July 2017 ahead of Christie’s November 2017 sale…having been instructed ‘not to inform anyone’ when the painting was ‘delivered to the Conservation Center [of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, where Modestini works as Senior Research Fellow and Conservator of the Kress program in Paintings Conservation] under guard and in great secrecy.’ Modestini writes approvingly of the fact that a deal brokered by Christie’s ahead of the sale whereby the vendor would receive at least $100million ‘was successfully kept under wraps’.”

For that late-stage re-restoration work in 2017, see Dalya Alberge, Mailonline, 22 December 2017, (“Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo da Vinci painting which became the world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in the last five years.”)

Above, Fig. 5: Although Martin Kemp’s 2018 Living with Leonardo is a professional lifetime memoir, he too includes chapters in support of the two Leonardo attributions he has championed – those of the Salvator Mundi and the mixed media drawing he dubbed “La Bella Principessa” that is owned by Peter Silverman – as seen above right. Kemp, like Hewitt, devotes much of his advocacy to attacking critics of the two attributions – including ArtWatch UK’s officers and associates.

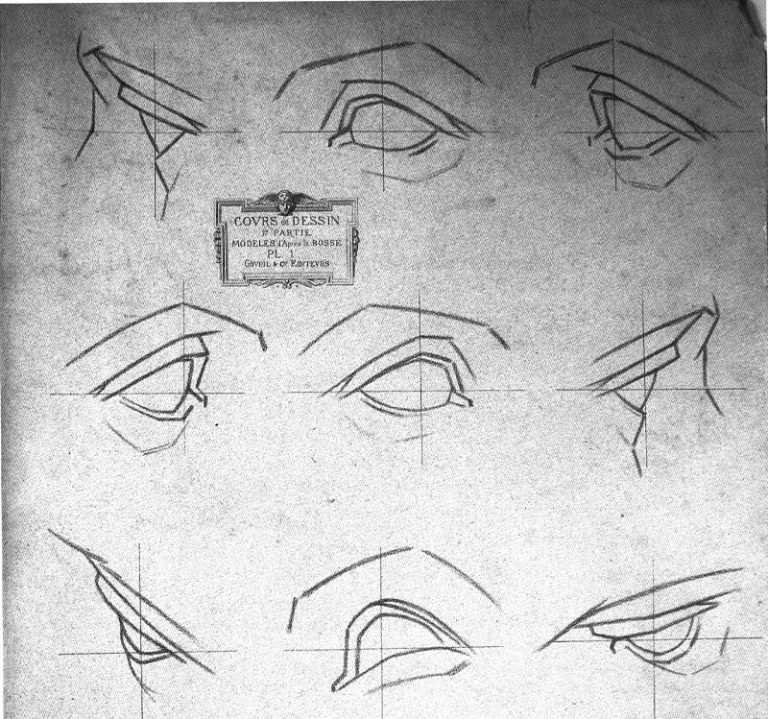

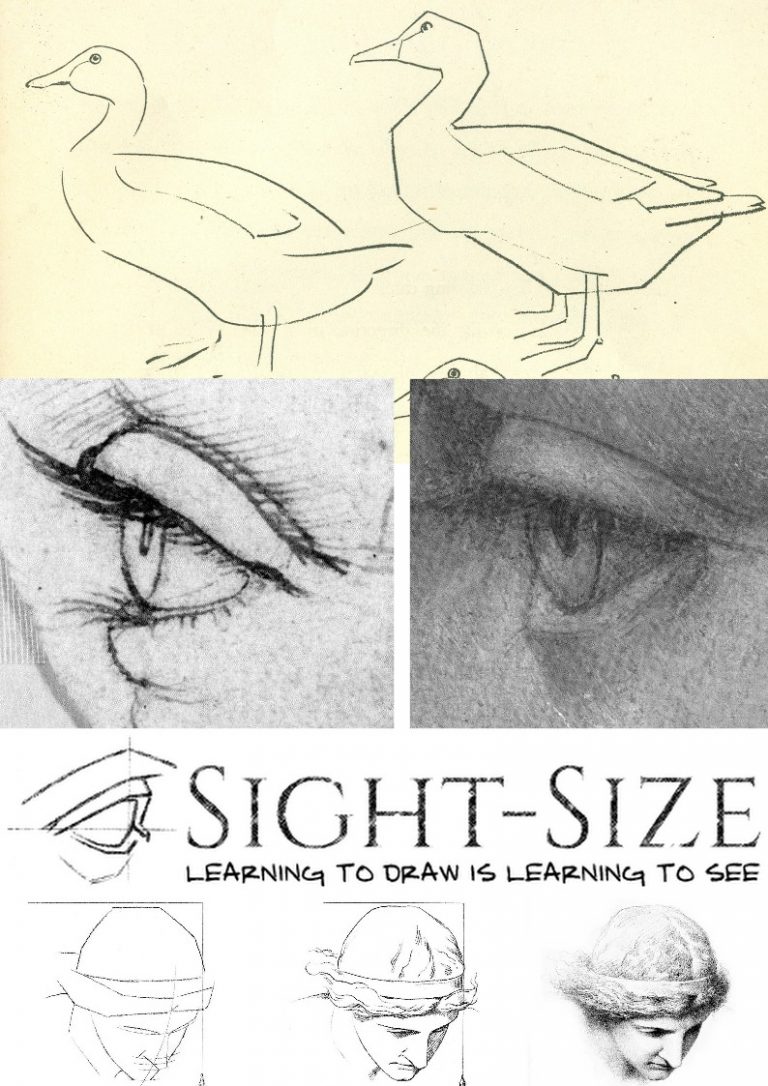

Above, Fig.6: Kemp’s publishers, Thames and Hudson, asked to reproduce a four-part graphic (top) which we had published on 3 May 2016 (“Problems with “La Bella Principessa” – Part II: Authentication Crisis”) precisely to demonstrate why, on stylistic grounds, the eye of “La Bella Principessa” could not possibly have been drawn by Leonardo. A crucial part of our cross-linked visual comparisons was an eye from a 19th century sheet of demonstrations to art students on how best to sketch eyes with short, straight lines. When Kemp’s book was published it carried a three-part diagram as shown above and as if it were the four-part one we had published. In Kemp’s reduced graphic, the embarrassing testimony of the guide to students had been omitted.

Above, Figs. 7 and 8: In the top image we show the sheet that had carried the eye which Kemp dropped. In the second image above we show (top) instructions in one of the “How to draw…” books, a guide to students on the relative merits of drawing ducks with curving lines or straight lines. Below it we show an eye drawn by Leonardo, with curving lines, and the eye of “La Bella Principessa”, drawn with straight lines. (As it happens, the eye that Kemp declined to publish is used as the logo for a drawing school – Sight-Size.)

Above, Fig. 9: This book of 2012 is something of a rarity within the genre of advocacy books in that it is written not by a professional art historian or art critic but by the work’s owner. It makes a fascinating and instructive read. We learn from the horse’s mouth, exactly who approached whom and when in the attempted formation of a sufficiency of experts to constitute an art-market “consensus of support”. We learn how Silverman planned his own media campaign to introduce both the work and its assembled supporters to the world. Such inside disclosures and resulting cross-linked accounts of the campaigning, can become sources of friction. In his 2018 memoir Kemp takes Silverman to task in a number of respects. Firstly (p.152), in terms of how the championing of the attribution should best have been managed:

“I had already written an extended report for Peter Silverman – longer than a standard academic article, shorter than a book. What I had seen and what I was gleaning from my continuing research persuaded me to write a book with Pascal [Cotte of Lumière Technology – see Fig. 11]…We also decided to include a short chapter by fingerprint specialist Paul Biro, who compared the inky fingertip with likely Leonardo prints. Ideally, nothing more should have appeared before our book [Kemp and Cotte’s, at Fig. 11] was launched. I was very concerned that the piecemeal, erratic and sensationalized release of incomplete stories was proving prejudicial. Early in 2009 I circulated a strategy to Peter and his supporters proposing that the drawing should be ‘exposed to a wholly non-commercial venue at the same time as all the research data had been released in full.’ I emphasized that all the material in the planned book should be embargoed before its publication. This placed considerable demands on Peter’s uneven reserves of discretion and patience…”

With so much cross-linking of players mishaps can arise. Members of tightly-knit groups of advocates can come collectively to see all opposition not as differing viewpoints but as quasi-pathological manifestations of “hostility” from rival “gangs”. For example, Hewitt reports:

“On July 1 Peter Paul Biro alerted Kemp and Cotte that the next edition of the New Yorker would be running a ‘potentially prejudiced and cherry-picked article about me, my work and the drawing.’ The New Yorker, he pointed out, was ‘owned by Condé Nast, which in turn is owned by Si Newhouse – a major client of Christie’s.’ ‘Christie’s and their friends are getting as much as they can in the public domain rubbishing the portrait and those who have worked on it’ replied Kemp – who had assured the New Yorker that Biro’s work on the [“La Bella”] portrait was exemplary.’ David Grann’s 16,000 word article on July 12th implied Biro was sleazy and incompetent. When Biro [unsuccessfully] sued the New Yorker for libel, a Federal judge paid implicit tribute to Grann’s verbal craftiness – declaring that his article did not make express accusations against Biro, or suggest concrete conclusions about whether or not he is a fraud.” Kemp, too, discusses Biro in his memoir:

“The strategy I had outlined fell apart when the fingerprint became the explosive subject of international attention before our book was published. Paul Biro, working from his studio in Montreal, compared Pascal’s amplified image of the fingerprint with prints in Leonardo’s unfinished St Jerome in the Vatican. Paul identified a print in the St Jerome which he saw as showing eight points of resemblance with that on the vellum. The most characteristic part of a fingerprint is the complex whorl at the centre of each fleshy pad. This was not apparent [– was not present?] in the print on the portrait which was made by the very tip of a finger. Paul’s ‘eight characteristics’ would not have been enough to secure a criminal conviction, but they were suggestive [of what?] and supportive. I could more or less see what he was seeing, if I tried hard, and I was happy to accept that he possessed a more expert eye for such things. [And besides:] The fingerprint evidence was a small part of the total fabric of evidence I was building up. But a ‘Leonardo fingerprint’ is news; it has a ‘cops and robbers’ dimension. The story was broken in the Antiques Trade Gazette by Simon Hewitt, a journalist with whom Peter had developed a trusting relationship. On 12 October 2009 the Gazette announced:

“‘ATG correspondent SIMON HEWITT gains exclusive access to the evidence used to unveil what the world’s leading scholars say is the first major Leonardo da Vinci find for 100 years…ATG have had exclusive access to that scientific evidence and can reveal that it literally reveals the hand – and fingerprint –of the artist in the work. The fingerprint is ‘highly comparable’ with one in the Vatican’.”

Kemp went on to say: “David Grann threw a lot of unpleasant mud at Paul Biro.” He then threw some of his own: “The source of much of the mud was Theresa Franks, founder of the Fine Art Registry, who had developed a reputation as an effective and litigious polemicist about the vagaries of the art world…The New Yorker piece was hugely damaging for Paul – and for the portrait, because our limited use of his evidence was used to taint the whole of the case we were making.”

Kemp’s remarks on Hewitt’s journalistic prowess might have disappointed the journalist/author whose book begins:

“INTRODUCTION

‘Is this the greatest art discovery of the century?’

“That was the front-page headline [he reproduces the front-page] in Antiques Trade Gazette on 17 October 2009, placed above my story about the portrait…It was one of the biggest stories of my career and, in terms of internet hits, the biggest story ever covered by the respected, if slightly fusty, art market weekly I had served on as Paris correspondent since 1985…”

Another attribution, another “gang” of opponents… Hewitt adds: “What Kemp dubbed ‘the New York gang’ were ‘almost bound to be hostile in an act of closing ranks, since they all missed it.’” Yet another is the “Polish gang”. Under a heading “POLES APART” Hewitt writes:

“Soon after Leonardo’s portrait of Bianca Sforza had gone on show in Monza, Katarzyna Pisarek [books editor of the AWUK Journal] published a 17,000-word article in Artibus & Historiae – a twice yearly journal edited by her Polish compatriot Józef Grabski, whose advisory committee included the Metropolitan Museum’s Everett Fahy (cited by Richard Dorment as a ‘vehement opponent of the Leonardo attribution’)…Pisarek was aping her Communist-era compatriot Bogdan Horodski, a former director of the Polish National Library…Pisarek harped on about Peter Paul Biro’s ‘dubious’ fingerprint evidence, omitting to mention that this had been removed as inconclusive from the second edition of the Kemp Cotte book…”

Hewitt seemed not to grasp the full import of the fact that an entire chapter of the Kemp/Cotte book had been excised. He pursued his Polish Conspiracy slur: “ ‘Why was Pisarek ‘suddenly so concerned to address this portrait when she had no record as a Leonardo scholar?’ wondered Martin Kemp. He presumed it ‘resulted from a kind of Polish solidarity’…On November 29 Waldemar Januszczak [Sunday Times art critic and TV broadcaster] – born in England to Polish parents…” and so on. Kemp/Cotte had had very good professional reasons to disassociate themselves from Biro. Kemp puts it with some delicacy in his memoir but the urgency is clear: “It transpired that Paul had previously achieved some notoriety in the detection of a purported Jackson Pollock discovered by a truck driver in a thrift shop. This discovery had been chronicled in a 2006 TV documentary, Who the #$&% is Jackson Pollock? Grann went on to tell a complex tale of Biro’s engagements with other Pollock authentications, in which the artist’s fingerprints appeared on paintings that were subsequently rejected by important Pollock scholars. It was alleged that Biro forged the Pollock fingerprints.”

In the first edition of the Kemp/Cotte book, the authors described the partial fingerprint as a full fingerprint in their introduction: “Following Lumière Technology’s discovery of a fingerprint and a handprint on the portrait, the authors turned to Peter Paul Biro, Director of Forensic Studies, Art and Access & Research, Montreal, to analyse this evidence in the context of what was known of Leonardo’s work…” And Kemp wrote (in his concluding chapter headed: “What constitutes proof?”): “…We have been able to detect extensive left-handed execution, not least in the layers below those we can see with our naked eye. Finger- and hand-prints have come to light in the way we have come to recognize as characteristic of Leonardo’s working methods. Indeed the isolated fingerprint near the left margin has strong if not conclusive evidential value that Leonardo himself touched the vellum.”

Above, Fig. 10: The catalogue to the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan”. Normally such a scholarly publication would not become ensnared in attribution controversies because public galleries do not, on principle, include privately owned, unpublished and un-attributed works without provenances that are on the market, but it did so with the Salvator Mundi – even though the identity of the picture’s by-then three owners (one of whom had bought-in with a $10 million stake) was undisclosed. Also undisclosed was: the venue at which the picture had been bought; the price at which it had been purchased; the identities of the leading scholars who were supposed to have endorsed the Leonardo attribution. Crucially, the supporters included the National Gallery’s director, one of its trustees and the curator and organiser of the Leonardo exhibition. The catalogue entry described the work as an autograph Leonardo painted prototype for the many similar Leonardo school Salvators that exist. Its author, Luke Syson, wrote: “This discussion anticipates the more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others. I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be presented in a forthcoming book.”

As mentioned above, that book has finally been published over eight years after the opening of the National Gallery exhibition and we now see that there are only three authors of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts: Margaret Dalivalle, Martin Kemp and Robert Simon. Modestini and Gutman-Rieppi have been dropped. In Living with Leonardo, Martin Kemp discusses the failure of Peter Silverman to get “La Bella Principessa” included in the National Gallery exhibition – on the organisation of which he (Kemp) had, at one point, been under consideration as co-curator:

“Looking back over the different fortunes of the attribution of the Salvator Mundi and the portrait of Bianca Sforza, there are some clear lessons to be drawn. The first concerns how a work of art enters the scholarly and public domains. Robert quietly introduced the Salvator Mundi to a judicious selection of experts, who – remarkably, given the usual leakiness of the art world kept their counsel for three years. By the time the painting emerged in public, there was a critical mass of influential voices who would speak in the painting’s favour. By contrast a series of incontinent leaks to the press, as happened with the Bianca prejudices a work in the eyes of specialist commentators. I regret that I did not have more influence on when and how La Bella Principessa emerged…

“Ownership also plays its role. The owners of the Salvator played their hand cleverly, fostering the idea that they wanted to do right by Leonardo’s masterpiece and were interested in it entering a public collection. Peter Silverman, on the other hand, has become a conspicuous presence in the art world…he has what is conventionally called ‘a good eye’. I believe that his intuition about the portrait of Bianca Sforza will be vindicated in the longer term, but unfortunately his variable declarations about its ownership, even if well-intentioned, did not induce trust and made him vulnerable to media criticism.”

This was in pointed contrast to Kemp’s view of Robert Simon:

“…Robert Simon, the custodian of the picture (whom I later learnt learned was its co-owner), outlined something of its history and restoration. He seemed sincere, straightforward and judiciously restrained, as proved to be the case in all our subsequent contacts…All of the witnesses in the [National] gallery’s conservation studio were sworn to confidentiality, and the painting travelled back to New York with Robert. It was becoming ‘a Leonardo’.”

Above, Fig. 11: The 2010 edition of Leonardo da Vinci, “La Bella Principessa” The Profile Portrait of a Milanese Woman. Since 2014 we have reviewed this work in the following posts:

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part I: The Look”

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part II: Authentication Crisis”

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part III: Dr. Pisarek responds to Prof. Kemp”

“Fake or Fortune: Hypotheses, Claims and Immutable Facts”

The day before the subsequently disappeared Salvator Mundi painting was sold at Christie’s, New York, we published a post explaining why the attribution was unsound and the provenance implausible:

“Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”

Weeks before the sale and before criticisms of the Salvator Mundi erupted in New York, we had spoken against the attribution in a Guardian interview – “Mystery over Christ’s orb in $100m Leonardo da Vinci painting”

Michael Daley, Director, 15 November 2019

“Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting”

Dalya Alberge reports in the Guardian that a Leonardo scholar, Matthew Landrus, believes most of the upgraded Salvator Mundi was painted by a Leonardo assistant, Bernardino Luini.

THE LUINI CONNECTION

In her Guardian article, “Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting”, Dalya Alberge further reports that the upgraded version of the Salvator Mundi that Matthew Landrus has de-attributed to Leonardo’s assistant, Bernardino Luini, is the very painting that was attributed to Luini in 1900, when acquired by Sir Charles Robinson for the Cook collection.

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the Salvator Mundi that was bought for $450m as a Leonardo for the Louvre Abu Dhabi in November 2017 as it was seen in 2007 when only part-repainted and about to be taken to the National Gallery, London, for a viewing by a small group of Leonardo scholars who are said to have been sworn to secrecy. (For the many subsequent changes to the painting see our “The $450m New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part II: It Restores, It Sells, therefore It Is” and Figs. 4 to 6 below.) Above, right: A detail of the National Gallery’s Luini Christ among the Doctors.

BIG CLAIMS ON INCOMPLETE EVIDENCE

Even after being sold twice (in 2013 and 2017) for a total of more than half a billion dollars, the painting’s 118 year long journey from a Luini to a Leonardo and now back to Luini again, remains a mystery: no one has disclosed when, from whom and where the painting is said to have been bought in 2005. Professor Martin Kemp recently disclosed that the work was bought for the original consortium of owners “by proxy”. Long-promised technical reports and accounts of the provenance have yet to appear and keep receding into the future. These lacunae notwithstanding, the painting is scheduled to be launched at the Louvre Abu Dhabi in September, and also to be included in a major Leonardo exhibition at the Paris Louvre in 2019.

THE ROLE OF LEONARDO’S ASSISTANTS IN THE LOUVRE ABU DHABI SALVATOR MUNDI

As Dalya Alberge reports, a number of Leonardo scholars have contested the present Leonardo attribution and held the work to be largely a studio production that was only part-painted by Leonardo himself. Frank Zöllner, a German art historian at the University of Leipzig and author of the catalogue raisonné Leonardo da Vinci – the Complete Paintings and Drawings, believes it to be either the work of a later Leonardo follower or a “high-quality product of Leonardo’s workshop”. Carmen Bambach, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, holds it to have been largely the work of Leonardo’s assistant Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. One scholar, Jacques Franck, suggested in a 29 November 2011 interview in the Journal des Arts that an attribution to either Luini or Leonardo’s late assistant (and effective ‘office manager’) Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called Salai or Salaino seemed plausible and persuasive. More recently, in January 2018, he tipped to Salai as the author because of strong similarities revealed by penetrating technical imaging examinations – see Figs. 2 and 3 below and “Salvator Mundi LES DESSOUS DE LA VENTE DU SIECLE”.

Above, Fig. 2: Left, an infra-red reflectogram of the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi; above, right, an infra-red reflectogram of Salai’s Head of Christ, signed and dated 1511, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana (Milan).

Above, Fig. 3: An infra-red reflectogram detail of the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. Jacques Franck writes: “This close-up view of the Fig. 2, left, document, reveals in the Saviour’s face, neck and head, the same typical underlying sketching-out technique using very thick dark lines to define the preliminary contours and modelling that are seen in Fig. 2, right. None of this underlying graphic/roughing out process is ever encountered in original Leonardo painting where the graphic/painterly stages are more subtle.”

CHANGING FACES: FOUR STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT IN THE LOUVRE ABU DHABI SALVATOR MUNDI

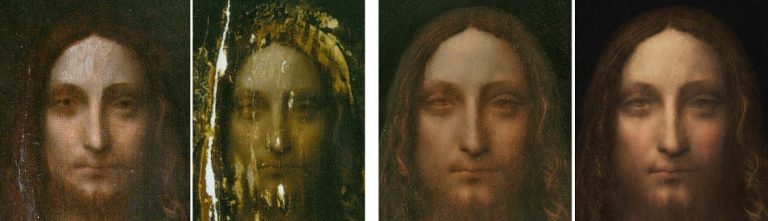

ABOVE, FIG.4: From the left, Face 1 – The former Cook collection Salvator Mundi when presented in 2005 (– when still “sticky” from a recent restoration) to the New York restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini.

Face 2: The former Cook collection painting after the panel had been repaired and the painting had been stripped down.

Face 3: The former Cook collection Salvator Mundi after several stages of repainting and as exhibited as a Leonardo at the National Gallery’s 2011-2012 Leonardo da Vinci, Painter at the Court of Milan exhibition.

Face 4: The face after yet further (- and initially undisclosed) repainting by Dianne Dwyer Modestini at Christie’s, New York, ahead of the 2017 sale – as was first published by Dalya Alberge in her Mail Online revelation: “Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo Da Vinci painting which became world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in last five years”.

Above, Fig. 5: Left, the former Cook collection painting’s face as in 2005; right, the face, as transformed over twelve years by Modestini, when presented for sale at Christie’s, New York, in November 2017.

Alberge’s current Guardian article, “Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting” has gone viral – see for example: CNN’s “Leonardo’s $450M painting may not be all Leonardo’s, says scholar”, and the ABC (Spain) “Crecen las dudas sobre la autoría del «Salvator Mundi» de Leonardo”.

In the CNN report, it is said that:

“Others are in less doubt. Curator of Italian Paintings at London’s National Gallery, Martin Kemp, sent the following statement to CNN Style by email: ‘The book I am publishing in 2019 with Robert Simon and Margaret Dalivalle (…) will present a conclusive body of evidence that the Salvator Mundi is a masterpiece by Leonardo. In the meantime I am not addressing ill-founded assertions that would attract no attention were it not for the sale price.’”

We make the following observations. Although Professor Martin Kemp is not a curator at the National Gallery he does seem to have been considered at one point as a possible co-curator of the National Gallery’s 2011-2012 Leonardo exhibition, which, in the event, was curated solely by the Gallery’s own then curator, Luke Syson, who is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Syson drew heavily for his 2011 catalogue entry on the painting on the researches of one of the owners of the Salvator Mundi, the New York art dealer, Robert Simon: “This discussion anticipates the more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others. I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be presented in a forthcoming book.” That book has now been coming for some time. First promised by the National Gallery in 2011, it was more recently promised for 2017, and then for this year, and now, for next year – and possibly in time for inclusion in the catalogue of the Paris Louvre’s planned major 2019 Leonardo exhibition?

Professor Kemp also promised a conclusive body of evidence for his attribution to Leonardo of the drawing he dubbed “La Bella Principessa”. In his 2012 book Leonardo’s Lost Princess, Peter Silverman, the owner of “La Bella Principessa”, wrote: “Martin believed that the fingerprints [compiled by the now discredited fingerprints expert Peter Paul Biro], though not conclusive on their own, added an important piece to the puzzle. He wrote to me, ‘This is yet one more component in what is as consistent a body of evidence as I have ever seen. I will be happy to emphasize that we have something as close to an open and shut case as is ever likely with an attribution of a previously unknown work to a major master. As you know, I was hugely skeptical at first, as one needs to be in the Leonardo jungle, but now I have not the slightest flicker of doubt that we are a dealing with a work of great beauty and originality that contributes something special to Leonardo’s oeuvre. It deserves to be in the public domain.’” In the event, the “La Bella Principessa” drawing did not enter the public domain. Unlike the Salvator Mundi, which sold for $450m, it was not included in the National Gallery’s 2011-2012 Leonardo exhibition and it presently remains, so far as we know, unsold, in a Swiss free port.

Kemp’s present lofty disinclination to address “ill-founded assertions that would attract no attention were it not for the sale price” marks a change of policy. Last year, immediately ahead of the sale that produced the astronomical price of the Salvator Mundi, Kemp was happy to engage polemically with those who rejected the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo attribution. As he has recently disclosed: “I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.”

SCHOLARS’ NEED FOR FULL AND DETAILED REPORTS AND FOR OPEN DEBATES

Above, Fig. 6: Left, the small-scale published (infra-red) technical image of the Salvator Mundi; centre, the painting as exhibited in 2011-2012 as a Leonardo at the National Gallery; right, the painting as presented for sale at Christie’s, New York, in 2017.

Much remains to be examined with this restoration-transformed but still, effectively, unpublished work where the promised reports on technical examinations and provenance seem perpetually trapped in the post like Billy Bunter’s postal order. Note in Fig. 6 above, for example, the radical changes made to the true left shoulder draperies; to the orb and the sole of the hand that holds it; and, above all, to the face. We must hope that the painting’s new owners will encourage the old 2005 consortium of owners to publish their privately commissioned researches as soon as possible. In general terms, it would be a much better thing if new and elevating attributions were once more published by single scholars, taking full responsibility in a scholarly publication, so that the case for a work’s re-attribution might be examined widely and discussed openly on a fully informative account and presentation of technical evidence and history of provenance. The recent tendency for owners to hold and selectively part-release researches during promotional campaigns of advocacy is not conducive to best scholarly practice.

Michael Daley, Director, 9 August 2018

Coming next:

Professor Martin Kemp and ArtWatch – Part 1: Twenty-four years of abuse on photo-testimony