Books on No-Hope Art Attributions

The latest addition to the fast-growing but least-estimable art book publishing genre – The Book of Art Attribution Advocacy – has finally arrived. It comes eight years late and on the second anniversary of Christie’s, New York, 15 November 2017 sale of the formerly attributed-Leonardo, Salvator Mundi picture – which disappeared the following day.

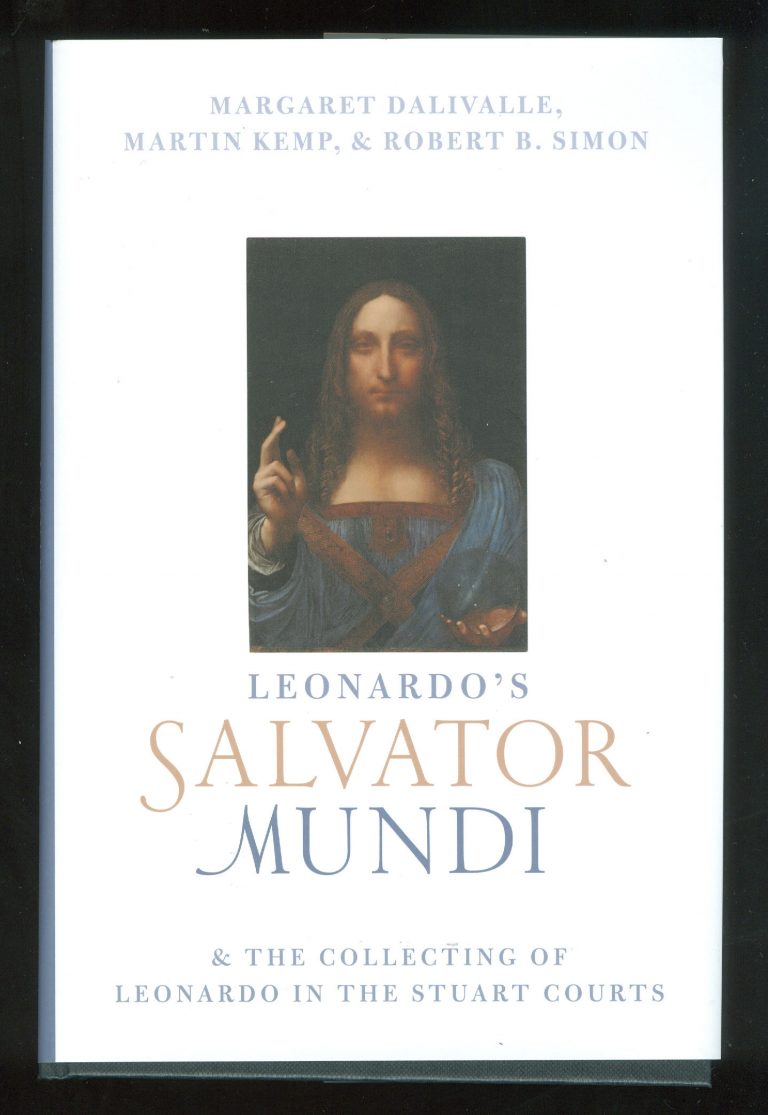

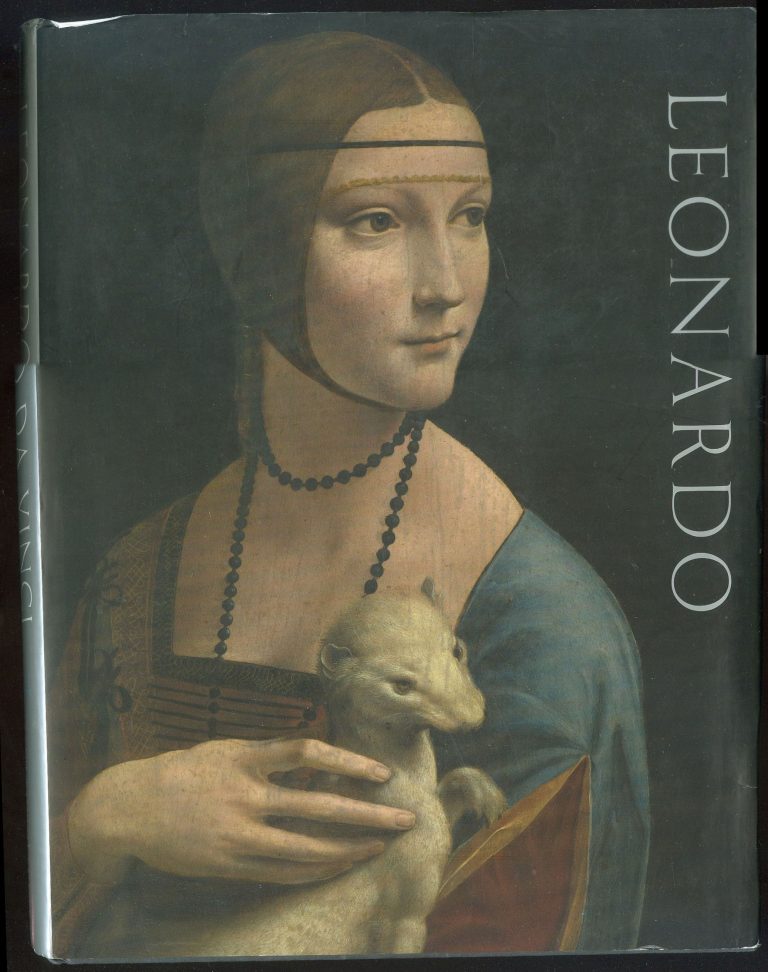

Fig. 1: The above book,Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts, constitutes the first official published account in support of the Salvator Mundi painting that was exhibited as an autograph Leonardo painting at the National Gallery in the 2011-12 exhibition, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan” (see Fig. 10) and that was sold at Christie’s two years ago for $450 million. The authors are: Margaret Dalivalle, a provenance specialist; Martin Kemp, Professor Emeritus and Leonardo specialist; and, Robert Simon, a New York art dealer and one of the two original buyers of the Salvator Mundi in 2005. The book contains no contributions by those who examined the painting technically and worked on its successive restorations. In their introduction and in defence of these startling omissions, the authors liken their book to a three-act opera: “However it is not intended to be an exhaustive treatment of the subject. As with an opera having a grand and intricate plot, this book will consider three facets of the story, each in depth, while necessarily bypassing many ancillary issues.”

There is no mention of the catcalls it has elicited. A glance at the illustrations shows the book to carry a new mystery: there would now seem to have been an undisclosed restoration.

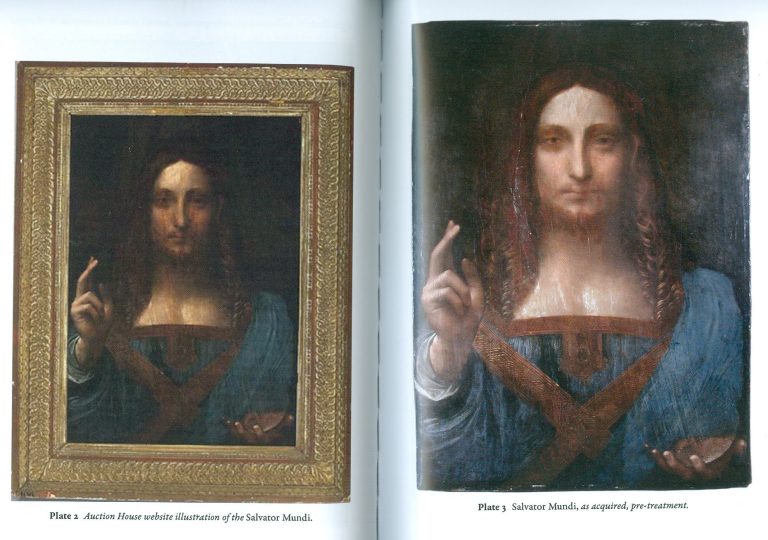

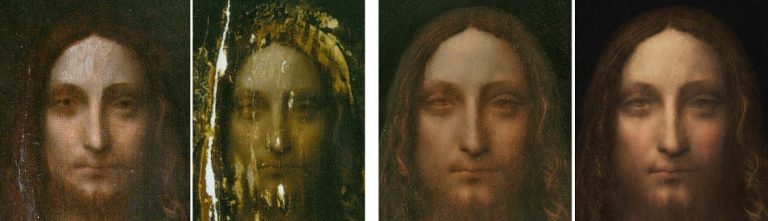

Above, Fig. 2: In this photo-spread, the first image shows the painting as illustrated by the auctioneers in 2005. The second image is said to show the picture as acquired by Robert Simon (and one other) at the auction. The restorer chosen by the new owners was Dianne Dwyer Modestini who worked on the painting in a number of restorations between 2005 and 2017. She has recalled (see Fig. 4) that when the painting was taken to her home in 2005 its surface was still sticky. The painting would thus seem to have been restored at some point after the sale catalogue was prepared and before it was taken to Modestini.

Above, Fig. 3: Simon Hewitt’s long-promised and compendious 2019 book (pp.352), Leonardo da Vinci and the Book of Doom, is written in support of the attributing to Leonardo of a mixed media drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Martin Kemp – and which remains unsold in a Swiss freeport. Now said by Hewitt to have been drawn by Leonardo in 1496 from Bianca Sforza, the illegitimate daughter of “Il Moro”, the 7th Duke of Milan, this book demonstrates – but does not expressly acknowledge – that no record of such a drawing exists before its sale at Christie’s, New York, in 1998 when it was sold as early 19th century German for $22,850 to a New York dealer who sold it on to Peter Silverman in 2007 for $19,000. In 2008 Silverman introduced himself to Hewitt by jumping into his cab saying: “May have a story for you one day! I’ll let you know.” In 2009 Silverman summoned Hewitt to Paris and a facsimile of “La Bella Principessa”. Having taken it at first sight to be early 19th century German, Hewitt produced an article for the Antiques Trade Gazette headed “Is this the greatest art market discovery of the century”.

Above, Fig. 4: Although Dianne Dwyer Modestini’s 2018 memoir, Masterpieces, is not strictly-speaking a book of art attribution advocacy, it contains as an epilogue, a chapter on the Salvator Mundi. In it, Modestini reproduces the photograph of the Salvator Mundi as shown in Fig. 2 above, right, and she describes it as being “as I first saw it in 2005”. We report in the ArtWatch UK Journal No. 32 (p. 47) how Modestini further commented on the picture in Masterpieces:

“When the Salvator Mundi returned to New York in July 2017 ahead of Christie’s November 2017 sale…having been instructed ‘not to inform anyone’ when the painting was ‘delivered to the Conservation Center [of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, where Modestini works as Senior Research Fellow and Conservator of the Kress program in Paintings Conservation] under guard and in great secrecy.’ Modestini writes approvingly of the fact that a deal brokered by Christie’s ahead of the sale whereby the vendor would receive at least $100million ‘was successfully kept under wraps’.”

For that late-stage re-restoration work in 2017, see Dalya Alberge, Mailonline, 22 December 2017, (“Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo da Vinci painting which became the world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in the last five years.”)

Above, Fig. 5: Although Martin Kemp’s 2018 Living with Leonardo is a professional lifetime memoir, he too includes chapters in support of the two Leonardo attributions he has championed – those of the Salvator Mundi and the mixed media drawing he dubbed “La Bella Principessa” that is owned by Peter Silverman – as seen above right. Kemp, like Hewitt, devotes much of his advocacy to attacking critics of the two attributions – including ArtWatch UK’s officers and associates.

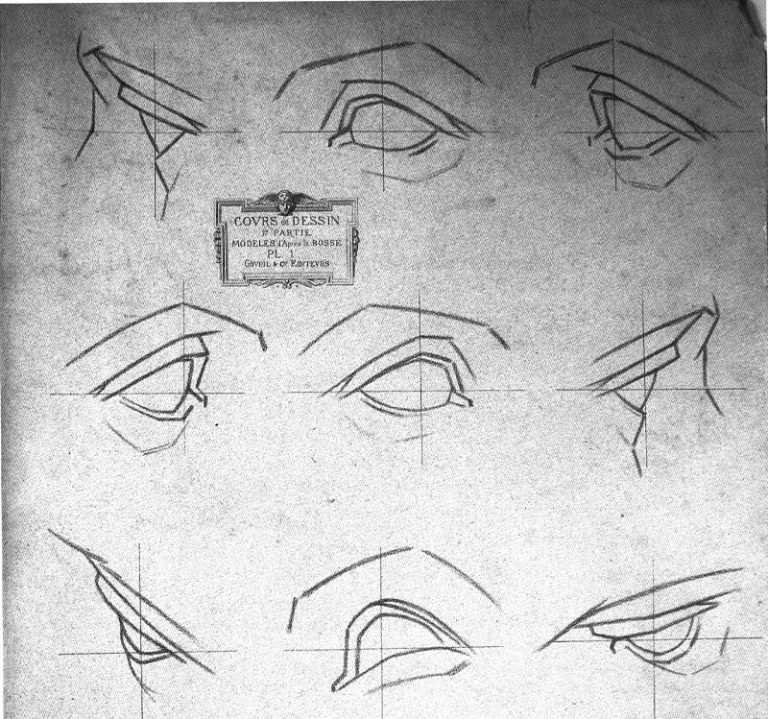

Above, Fig.6: Kemp’s publishers, Thames and Hudson, asked to reproduce a four-part graphic (top) which we had published on 3 May 2016 (“Problems with “La Bella Principessa” – Part II: Authentication Crisis”) precisely to demonstrate why, on stylistic grounds, the eye of “La Bella Principessa” could not possibly have been drawn by Leonardo. A crucial part of our cross-linked visual comparisons was an eye from a 19th century sheet of demonstrations to art students on how best to sketch eyes with short, straight lines. When Kemp’s book was published it carried a three-part diagram as shown above and as if it were the four-part one we had published. In Kemp’s reduced graphic, the embarrassing testimony of the guide to students had been omitted.

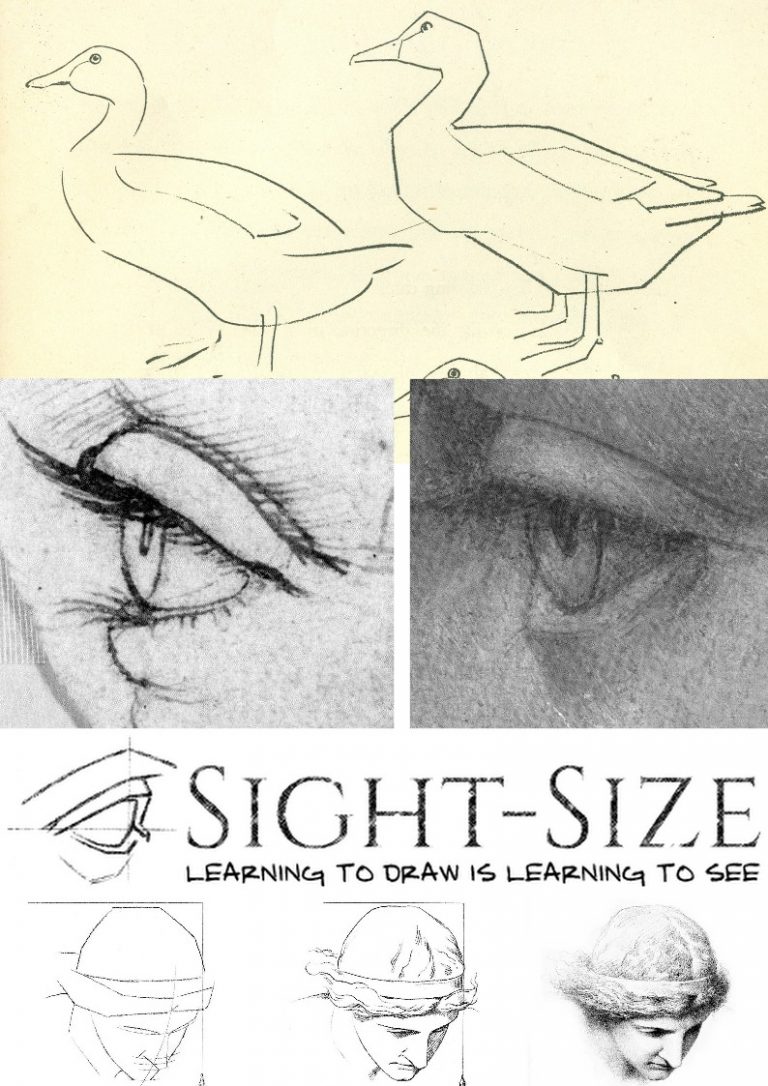

Above, Figs. 7 and 8: In the top image we show the sheet that had carried the eye which Kemp dropped. In the second image above we show (top) instructions in one of the “How to draw…” books, a guide to students on the relative merits of drawing ducks with curving lines or straight lines. Below it we show an eye drawn by Leonardo, with curving lines, and the eye of “La Bella Principessa”, drawn with straight lines. (As it happens, the eye that Kemp declined to publish is used as the logo for a drawing school – Sight-Size.)

Above, Fig. 9: This book of 2012 is something of a rarity within the genre of advocacy books in that it is written not by a professional art historian or art critic but by the work’s owner. It makes a fascinating and instructive read. We learn from the horse’s mouth, exactly who approached whom and when in the attempted formation of a sufficiency of experts to constitute an art-market “consensus of support”. We learn how Silverman planned his own media campaign to introduce both the work and its assembled supporters to the world. Such inside disclosures and resulting cross-linked accounts of the campaigning, can become sources of friction. In his 2018 memoir Kemp takes Silverman to task in a number of respects. Firstly (p.152), in terms of how the championing of the attribution should best have been managed:

“I had already written an extended report for Peter Silverman – longer than a standard academic article, shorter than a book. What I had seen and what I was gleaning from my continuing research persuaded me to write a book with Pascal [Cotte of Lumière Technology – see Fig. 11]…We also decided to include a short chapter by fingerprint specialist Paul Biro, who compared the inky fingertip with likely Leonardo prints. Ideally, nothing more should have appeared before our book [Kemp and Cotte’s, at Fig. 11] was launched. I was very concerned that the piecemeal, erratic and sensationalized release of incomplete stories was proving prejudicial. Early in 2009 I circulated a strategy to Peter and his supporters proposing that the drawing should be ‘exposed to a wholly non-commercial venue at the same time as all the research data had been released in full.’ I emphasized that all the material in the planned book should be embargoed before its publication. This placed considerable demands on Peter’s uneven reserves of discretion and patience…”

With so much cross-linking of players mishaps can arise. Members of tightly-knit groups of advocates can come collectively to see all opposition not as differing viewpoints but as quasi-pathological manifestations of “hostility” from rival “gangs”. For example, Hewitt reports:

“On July 1 Peter Paul Biro alerted Kemp and Cotte that the next edition of the New Yorker would be running a ‘potentially prejudiced and cherry-picked article about me, my work and the drawing.’ The New Yorker, he pointed out, was ‘owned by Condé Nast, which in turn is owned by Si Newhouse – a major client of Christie’s.’ ‘Christie’s and their friends are getting as much as they can in the public domain rubbishing the portrait and those who have worked on it’ replied Kemp – who had assured the New Yorker that Biro’s work on the [“La Bella”] portrait was exemplary.’ David Grann’s 16,000 word article on July 12th implied Biro was sleazy and incompetent. When Biro [unsuccessfully] sued the New Yorker for libel, a Federal judge paid implicit tribute to Grann’s verbal craftiness – declaring that his article did not make express accusations against Biro, or suggest concrete conclusions about whether or not he is a fraud.” Kemp, too, discusses Biro in his memoir:

“The strategy I had outlined fell apart when the fingerprint became the explosive subject of international attention before our book was published. Paul Biro, working from his studio in Montreal, compared Pascal’s amplified image of the fingerprint with prints in Leonardo’s unfinished St Jerome in the Vatican. Paul identified a print in the St Jerome which he saw as showing eight points of resemblance with that on the vellum. The most characteristic part of a fingerprint is the complex whorl at the centre of each fleshy pad. This was not apparent [– was not present?] in the print on the portrait which was made by the very tip of a finger. Paul’s ‘eight characteristics’ would not have been enough to secure a criminal conviction, but they were suggestive [of what?] and supportive. I could more or less see what he was seeing, if I tried hard, and I was happy to accept that he possessed a more expert eye for such things. [And besides:] The fingerprint evidence was a small part of the total fabric of evidence I was building up. But a ‘Leonardo fingerprint’ is news; it has a ‘cops and robbers’ dimension. The story was broken in the Antiques Trade Gazette by Simon Hewitt, a journalist with whom Peter had developed a trusting relationship. On 12 October 2009 the Gazette announced:

“‘ATG correspondent SIMON HEWITT gains exclusive access to the evidence used to unveil what the world’s leading scholars say is the first major Leonardo da Vinci find for 100 years…ATG have had exclusive access to that scientific evidence and can reveal that it literally reveals the hand – and fingerprint –of the artist in the work. The fingerprint is ‘highly comparable’ with one in the Vatican’.”

Kemp went on to say: “David Grann threw a lot of unpleasant mud at Paul Biro.” He then threw some of his own: “The source of much of the mud was Theresa Franks, founder of the Fine Art Registry, who had developed a reputation as an effective and litigious polemicist about the vagaries of the art world…The New Yorker piece was hugely damaging for Paul – and for the portrait, because our limited use of his evidence was used to taint the whole of the case we were making.”

Kemp’s remarks on Hewitt’s journalistic prowess might have disappointed the journalist/author whose book begins:

“INTRODUCTION

‘Is this the greatest art discovery of the century?’

“That was the front-page headline [he reproduces the front-page] in Antiques Trade Gazette on 17 October 2009, placed above my story about the portrait…It was one of the biggest stories of my career and, in terms of internet hits, the biggest story ever covered by the respected, if slightly fusty, art market weekly I had served on as Paris correspondent since 1985…”

Another attribution, another “gang” of opponents… Hewitt adds: “What Kemp dubbed ‘the New York gang’ were ‘almost bound to be hostile in an act of closing ranks, since they all missed it.’” Yet another is the “Polish gang”. Under a heading “POLES APART” Hewitt writes:

“Soon after Leonardo’s portrait of Bianca Sforza had gone on show in Monza, Katarzyna Pisarek [books editor of the AWUK Journal] published a 17,000-word article in Artibus & Historiae – a twice yearly journal edited by her Polish compatriot Józef Grabski, whose advisory committee included the Metropolitan Museum’s Everett Fahy (cited by Richard Dorment as a ‘vehement opponent of the Leonardo attribution’)…Pisarek was aping her Communist-era compatriot Bogdan Horodski, a former director of the Polish National Library…Pisarek harped on about Peter Paul Biro’s ‘dubious’ fingerprint evidence, omitting to mention that this had been removed as inconclusive from the second edition of the Kemp Cotte book…”

Hewitt seemed not to grasp the full import of the fact that an entire chapter of the Kemp/Cotte book had been excised. He pursued his Polish Conspiracy slur: “ ‘Why was Pisarek ‘suddenly so concerned to address this portrait when she had no record as a Leonardo scholar?’ wondered Martin Kemp. He presumed it ‘resulted from a kind of Polish solidarity’…On November 29 Waldemar Januszczak [Sunday Times art critic and TV broadcaster] – born in England to Polish parents…” and so on. Kemp/Cotte had had very good professional reasons to disassociate themselves from Biro. Kemp puts it with some delicacy in his memoir but the urgency is clear: “It transpired that Paul had previously achieved some notoriety in the detection of a purported Jackson Pollock discovered by a truck driver in a thrift shop. This discovery had been chronicled in a 2006 TV documentary, Who the #$&% is Jackson Pollock? Grann went on to tell a complex tale of Biro’s engagements with other Pollock authentications, in which the artist’s fingerprints appeared on paintings that were subsequently rejected by important Pollock scholars. It was alleged that Biro forged the Pollock fingerprints.”

In the first edition of the Kemp/Cotte book, the authors described the partial fingerprint as a full fingerprint in their introduction: “Following Lumière Technology’s discovery of a fingerprint and a handprint on the portrait, the authors turned to Peter Paul Biro, Director of Forensic Studies, Art and Access & Research, Montreal, to analyse this evidence in the context of what was known of Leonardo’s work…” And Kemp wrote (in his concluding chapter headed: “What constitutes proof?”): “…We have been able to detect extensive left-handed execution, not least in the layers below those we can see with our naked eye. Finger- and hand-prints have come to light in the way we have come to recognize as characteristic of Leonardo’s working methods. Indeed the isolated fingerprint near the left margin has strong if not conclusive evidential value that Leonardo himself touched the vellum.”

Above, Fig. 10: The catalogue to the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan”. Normally such a scholarly publication would not become ensnared in attribution controversies because public galleries do not, on principle, include privately owned, unpublished and un-attributed works without provenances that are on the market, but it did so with the Salvator Mundi – even though the identity of the picture’s by-then three owners (one of whom had bought-in with a $10 million stake) was undisclosed. Also undisclosed was: the venue at which the picture had been bought; the price at which it had been purchased; the identities of the leading scholars who were supposed to have endorsed the Leonardo attribution. Crucially, the supporters included the National Gallery’s director, one of its trustees and the curator and organiser of the Leonardo exhibition. The catalogue entry described the work as an autograph Leonardo painted prototype for the many similar Leonardo school Salvators that exist. Its author, Luke Syson, wrote: “This discussion anticipates the more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others. I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be presented in a forthcoming book.”

As mentioned above, that book has finally been published over eight years after the opening of the National Gallery exhibition and we now see that there are only three authors of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts: Margaret Dalivalle, Martin Kemp and Robert Simon. Modestini and Gutman-Rieppi have been dropped. In Living with Leonardo, Martin Kemp discusses the failure of Peter Silverman to get “La Bella Principessa” included in the National Gallery exhibition – on the organisation of which he (Kemp) had, at one point, been under consideration as co-curator:

“Looking back over the different fortunes of the attribution of the Salvator Mundi and the portrait of Bianca Sforza, there are some clear lessons to be drawn. The first concerns how a work of art enters the scholarly and public domains. Robert quietly introduced the Salvator Mundi to a judicious selection of experts, who – remarkably, given the usual leakiness of the art world kept their counsel for three years. By the time the painting emerged in public, there was a critical mass of influential voices who would speak in the painting’s favour. By contrast a series of incontinent leaks to the press, as happened with the Bianca prejudices a work in the eyes of specialist commentators. I regret that I did not have more influence on when and how La Bella Principessa emerged…

“Ownership also plays its role. The owners of the Salvator played their hand cleverly, fostering the idea that they wanted to do right by Leonardo’s masterpiece and were interested in it entering a public collection. Peter Silverman, on the other hand, has become a conspicuous presence in the art world…he has what is conventionally called ‘a good eye’. I believe that his intuition about the portrait of Bianca Sforza will be vindicated in the longer term, but unfortunately his variable declarations about its ownership, even if well-intentioned, did not induce trust and made him vulnerable to media criticism.”

This was in pointed contrast to Kemp’s view of Robert Simon:

“…Robert Simon, the custodian of the picture (whom I later learnt learned was its co-owner), outlined something of its history and restoration. He seemed sincere, straightforward and judiciously restrained, as proved to be the case in all our subsequent contacts…All of the witnesses in the [National] gallery’s conservation studio were sworn to confidentiality, and the painting travelled back to New York with Robert. It was becoming ‘a Leonardo’.”

Above, Fig. 11: The 2010 edition of Leonardo da Vinci, “La Bella Principessa” The Profile Portrait of a Milanese Woman. Since 2014 we have reviewed this work in the following posts:

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part I: The Look”

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part II: Authentication Crisis”

“Problems with ‘La Bella Principessa’ – Part III: Dr. Pisarek responds to Prof. Kemp”

“Fake or Fortune: Hypotheses, Claims and Immutable Facts”

The day before the subsequently disappeared Salvator Mundi painting was sold at Christie’s, New York, we published a post explaining why the attribution was unsound and the provenance implausible:

“Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”

Weeks before the sale and before criticisms of the Salvator Mundi erupted in New York, we had spoken against the attribution in a Guardian interview – “Mystery over Christ’s orb in $100m Leonardo da Vinci painting”

Michael Daley, Director, 15 November 2019

“Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting”

Dalya Alberge reports in the Guardian that a Leonardo scholar, Matthew Landrus, believes most of the upgraded Salvator Mundi was painted by a Leonardo assistant, Bernardino Luini.

THE LUINI CONNECTION

In her Guardian article, “Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting”, Dalya Alberge further reports that the upgraded version of the Salvator Mundi that Matthew Landrus has de-attributed to Leonardo’s assistant, Bernardino Luini, is the very painting that was attributed to Luini in 1900, when acquired by Sir Charles Robinson for the Cook collection.

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the Salvator Mundi that was bought for $450m as a Leonardo for the Louvre Abu Dhabi in November 2017 as it was seen in 2007 when only part-repainted and about to be taken to the National Gallery, London, for a viewing by a small group of Leonardo scholars who are said to have been sworn to secrecy. (For the many subsequent changes to the painting see our “The $450m New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part II: It Restores, It Sells, therefore It Is” and Figs. 4 to 6 below.) Above, right: A detail of the National Gallery’s Luini Christ among the Doctors.

BIG CLAIMS ON INCOMPLETE EVIDENCE

Even after being sold twice (in 2013 and 2017) for a total of more than half a billion dollars, the painting’s 118 year long journey from a Luini to a Leonardo and now back to Luini again, remains a mystery: no one has disclosed when, from whom and where the painting is said to have been bought in 2005. Professor Martin Kemp recently disclosed that the work was bought for the original consortium of owners “by proxy”. Long-promised technical reports and accounts of the provenance have yet to appear and keep receding into the future. These lacunae notwithstanding, the painting is scheduled to be launched at the Louvre Abu Dhabi in September, and also to be included in a major Leonardo exhibition at the Paris Louvre in 2019.

THE ROLE OF LEONARDO’S ASSISTANTS IN THE LOUVRE ABU DHABI SALVATOR MUNDI

As Dalya Alberge reports, a number of Leonardo scholars have contested the present Leonardo attribution and held the work to be largely a studio production that was only part-painted by Leonardo himself. Frank Zöllner, a German art historian at the University of Leipzig and author of the catalogue raisonné Leonardo da Vinci – the Complete Paintings and Drawings, believes it to be either the work of a later Leonardo follower or a “high-quality product of Leonardo’s workshop”. Carmen Bambach, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, holds it to have been largely the work of Leonardo’s assistant Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. One scholar, Jacques Franck, suggested in a 29 November 2011 interview in the Journal des Arts that an attribution to either Luini or Leonardo’s late assistant (and effective ‘office manager’) Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called Salai or Salaino seemed plausible and persuasive. More recently, in January 2018, he tipped to Salai as the author because of strong similarities revealed by penetrating technical imaging examinations – see Figs. 2 and 3 below and “Salvator Mundi LES DESSOUS DE LA VENTE DU SIECLE”.

Above, Fig. 2: Left, an infra-red reflectogram of the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi; above, right, an infra-red reflectogram of Salai’s Head of Christ, signed and dated 1511, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana (Milan).

Above, Fig. 3: An infra-red reflectogram detail of the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. Jacques Franck writes: “This close-up view of the Fig. 2, left, document, reveals in the Saviour’s face, neck and head, the same typical underlying sketching-out technique using very thick dark lines to define the preliminary contours and modelling that are seen in Fig. 2, right. None of this underlying graphic/roughing out process is ever encountered in original Leonardo painting where the graphic/painterly stages are more subtle.”

CHANGING FACES: FOUR STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT IN THE LOUVRE ABU DHABI SALVATOR MUNDI

ABOVE, FIG.4: From the left, Face 1 – The former Cook collection Salvator Mundi when presented in 2005 (– when still “sticky” from a recent restoration) to the New York restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini.

Face 2: The former Cook collection painting after the panel had been repaired and the painting had been stripped down.

Face 3: The former Cook collection Salvator Mundi after several stages of repainting and as exhibited as a Leonardo at the National Gallery’s 2011-2012 Leonardo da Vinci, Painter at the Court of Milan exhibition.

Face 4: The face after yet further (- and initially undisclosed) repainting by Dianne Dwyer Modestini at Christie’s, New York, ahead of the 2017 sale – as was first published by Dalya Alberge in her Mail Online revelation: “Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo Da Vinci painting which became world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in last five years”.

Above, Fig. 5: Left, the former Cook collection painting’s face as in 2005; right, the face, as transformed over twelve years by Modestini, when presented for sale at Christie’s, New York, in November 2017.

Alberge’s current Guardian article, “Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting” has gone viral – see for example: CNN’s “Leonardo’s $450M painting may not be all Leonardo’s, says scholar”, and the ABC (Spain) “Crecen las dudas sobre la autoría del «Salvator Mundi» de Leonardo”.

In the CNN report, it is said that:

“Others are in less doubt. Curator of Italian Paintings at London’s National Gallery, Martin Kemp, sent the following statement to CNN Style by email: ‘The book I am publishing in 2019 with Robert Simon and Margaret Dalivalle (…) will present a conclusive body of evidence that the Salvator Mundi is a masterpiece by Leonardo. In the meantime I am not addressing ill-founded assertions that would attract no attention were it not for the sale price.’”

We make the following observations. Although Professor Martin Kemp is not a curator at the National Gallery he does seem to have been considered at one point as a possible co-curator of the National Gallery’s 2011-2012 Leonardo exhibition, which, in the event, was curated solely by the Gallery’s own then curator, Luke Syson, who is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Syson drew heavily for his 2011 catalogue entry on the painting on the researches of one of the owners of the Salvator Mundi, the New York art dealer, Robert Simon: “This discussion anticipates the more detailed publication of this picture by Robert Simon and others. I am grateful to Robert Simon for making available his research and that of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Nica Gutman Rieppi and (for the picture’s provenance) Margaret Dalivalle, all to be presented in a forthcoming book.” That book has now been coming for some time. First promised by the National Gallery in 2011, it was more recently promised for 2017, and then for this year, and now, for next year – and possibly in time for inclusion in the catalogue of the Paris Louvre’s planned major 2019 Leonardo exhibition?

Professor Kemp also promised a conclusive body of evidence for his attribution to Leonardo of the drawing he dubbed “La Bella Principessa”. In his 2012 book Leonardo’s Lost Princess, Peter Silverman, the owner of “La Bella Principessa”, wrote: “Martin believed that the fingerprints [compiled by the now discredited fingerprints expert Peter Paul Biro], though not conclusive on their own, added an important piece to the puzzle. He wrote to me, ‘This is yet one more component in what is as consistent a body of evidence as I have ever seen. I will be happy to emphasize that we have something as close to an open and shut case as is ever likely with an attribution of a previously unknown work to a major master. As you know, I was hugely skeptical at first, as one needs to be in the Leonardo jungle, but now I have not the slightest flicker of doubt that we are a dealing with a work of great beauty and originality that contributes something special to Leonardo’s oeuvre. It deserves to be in the public domain.’” In the event, the “La Bella Principessa” drawing did not enter the public domain. Unlike the Salvator Mundi, which sold for $450m, it was not included in the National Gallery’s 2011-2012 Leonardo exhibition and it presently remains, so far as we know, unsold, in a Swiss free port.

Kemp’s present lofty disinclination to address “ill-founded assertions that would attract no attention were it not for the sale price” marks a change of policy. Last year, immediately ahead of the sale that produced the astronomical price of the Salvator Mundi, Kemp was happy to engage polemically with those who rejected the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo attribution. As he has recently disclosed: “I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.”

SCHOLARS’ NEED FOR FULL AND DETAILED REPORTS AND FOR OPEN DEBATES

Above, Fig. 6: Left, the small-scale published (infra-red) technical image of the Salvator Mundi; centre, the painting as exhibited in 2011-2012 as a Leonardo at the National Gallery; right, the painting as presented for sale at Christie’s, New York, in 2017.

Much remains to be examined with this restoration-transformed but still, effectively, unpublished work where the promised reports on technical examinations and provenance seem perpetually trapped in the post like Billy Bunter’s postal order. Note in Fig. 6 above, for example, the radical changes made to the true left shoulder draperies; to the orb and the sole of the hand that holds it; and, above all, to the face. We must hope that the painting’s new owners will encourage the old 2005 consortium of owners to publish their privately commissioned researches as soon as possible. In general terms, it would be a much better thing if new and elevating attributions were once more published by single scholars, taking full responsibility in a scholarly publication, so that the case for a work’s re-attribution might be examined widely and discussed openly on a fully informative account and presentation of technical evidence and history of provenance. The recent tendency for owners to hold and selectively part-release researches during promotional campaigns of advocacy is not conducive to best scholarly practice.

Michael Daley, Director, 9 August 2018

Coming next:

Professor Martin Kemp and ArtWatch – Part 1: Twenty-four years of abuse on photo-testimony

Problems with “La Bella Principessa”~ Part I: The Look

The world famous drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Professor Martin Kemp is insured for $150 million and lives in a “secure vault in Zurich”. It is not a portrait of Bianca Sforza by Leonardo da Vinci, as has been claimed, but a twentieth century forged or pastiche Leonardo.

WHITHER “LA BELLA PRINCIPESSA”

In 1998 the now so-called “La Bella Principessa” appeared from nowhere at Christie’s, New York. A hybrid work made in mixed media that were never employed by Leonardo (three chalks, ink, “liquid colour”), on a support that was never used by Leonardo (vellum), and portraying a woman in a manner that is nowhere encountered in Leonardo, it was presented as “German School, early 19th century” and “the property of a lady”. It went for $22,850 to a New York dealer who sold it nine years later on a requested discount of 10 per cent for $19,000 to an art collector, Peter Silverman, who said he was buying on behalf of another (unidentified) collector whom he later described as one of “the richest men in Europe”. Thus, at that date, it was not known who owned the drawing or by whom it had been consigned to Christie’s and it remained entirely without provenance. In its nine years long life, no one – not even its new owner(s) – had taken it to be by Leonardo.

In a 2012 book (Lost Princess ~ One man’s quest to authenticate an unknown portrait by Leonardo da Vinci), Silverman claimed a successful upgrading to Leonardo and described how he had gained the support of distinguished scholars including Professor Martin Kemp who had formulated an elaborate hypothetical history in which the drawing was said to be a Leonardo portrait made either from a living subject in celebration of her wedding or in commemoration after her death in 1496.

Nonetheless, the drawing failed to gain a consensus of scholarly support and is rejected in centres like New York, London and Vienna. Carmen Bambach, the Metropolitan Museum’s Renaissance drawings authority dismissed “La Bella” on the grounds that “It does not look like a Leonardo”. Thomas Hoving, a former Metropolitan Museum director, held it to look “too sweet” to be Leonardo. ARTnews reported that the Albertina Museum’s director, Klaus Albrecht Schröder, had noted “No one is convinced it is a Leonardo”. In the Burlington Magazine Professor David Ekserdjian suspected it to be “counterfeit”.

THE LOOK OF “LA BELLA” AND THE COMPANY SHE BEST KEEPS

In matters of attribution the most important consideration is the look of a work. Many things can be appraised simultaneously but, conceptually, the “look” of a work might be broken down into two aspects: an initial at-a-glance response to a work’s effects and appraisal of its internal values and relationships; and, a comparison of the effects, relationships and values with those of bona fide productions of the attributed artist, or with those of the artist’s students, associates or followers. It can also be useful to compare the looks of works with those of copyists and known forgers. It might fairly be said that in connoisseurship, as in the evaluation of restorations, visual comparisons are of the essence. (In ArtWatch we take pride in the extent to which we seek out all possible comparative visual material and regret that some institutions still hinder our efforts in this regard.)

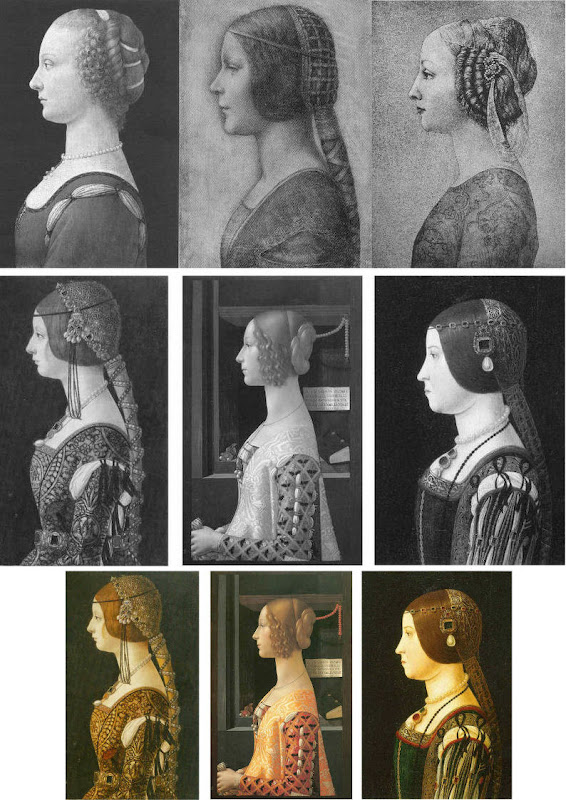

Above, Fig. 1. If we put aside questions of attribution and simply look at the group above, we find works of remarkably similar figural motifs and formats that clearly relate to and derive from a most distinctive type of 15th century Italian profile female portrait. These similar-looking works are similarly sized, being, respectively from left to right:

A Young Woman, 14 and 1/4 x 10 inches;

“La Bella Principessa”, 13 x 9 and 3/4 inches; and,

A Young Woman, 18 x 12 1/2 inches (here shown mirrored).

All show young women depicted in the strict early Renaissance profile convention made in emulation of antique relief portraits on coins and medals. Although very widely encountered (see Fig. 4), Leonardo side-stepped the type in order to intensify plastic and expressive values with sculpturally-purposive shading and axial shifts in the bodies and gazes of his portraits (see Fig. 6). The portrayals above are strikingly similar in their head/torso relationships; in their absences of background; in their highly elaborated coiffures which offset ‘sartorially’ skimped and unconvincing simplifications of costume; in their sparse or wholly absent depictions of jewellery; and, even, in their almost identically cropped motifs. Collectively they might be taken as a suite of variations on a simple theme. We take all three to be twentieth century Italian artefacts. At least two of them are linked to Bernard Berenson and the two on which reports have been published have unusual and problematic supports.

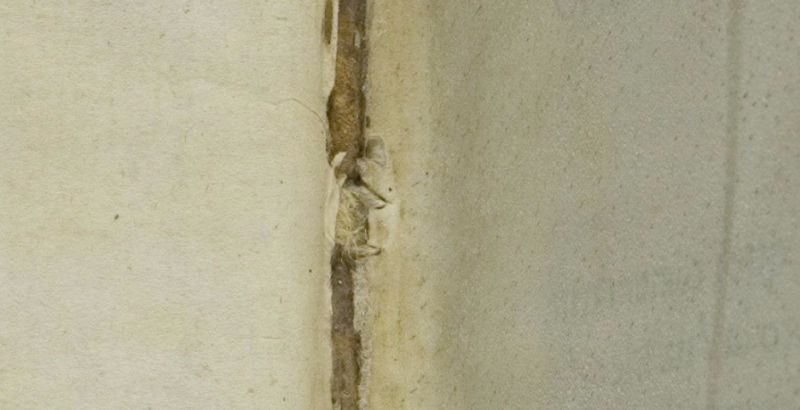

As mentioned below, the Detroit picture is painted on top of photographic paper. It is suspected that it might have been a photograph of the Frick sculpture to which the painting was initially related. The “La Bella Principessa” is drawn, exceptionally for Leonardo, on a sheet of vellum which appears to have been removed from a book and it is, most unusually, glued to an oak panel. The panel itself is a curiosity: although a number of “butterfly keys” have been inserted into its back, as if to restrain splitting, there is no evidence of splits in the panel and, if there were, the present four such keys in such a small panel might be considered restoration “over-kill”. If the panel had split while the vellum was glued to it, the drawing would have split with the panel. The fact that the vellum has been “copiously glued” to a (possibly pre-restored) oak panel makes it impossible to examine the back of the drawing which is said by one of its proponents, (Cristina Geddo, an expert in Leonardo’s students and Milanese “Leonardesques”) to bear “superimposed numbers…a written inscription…[and a] little winged dragon – at least that is what it seems.” For Geddo, this unexamined content is reassuring: “This feature, too, counts in favour of an attribution to Leonardo, who, even though he never to our knowledge used a parchment support in his work, was in the habit of re-using the paper on which he drew.”

(In reading the compendious literature on this proposed attribution, we have sometimes wondered what might be allowed by its supporters to count as evidence against the attribution.)

CONSIDER THE HISTORIES

The portrait on the left, A Young Woman, was bought in 1936 by the Detroit Institute of Arts as by Leonardo da Vinci or Andrea del Verrocchio. The institute’s director, W. D. Valentiner, made this attribution on the strength of clear correspondences with the curls in the hair of Leonardo’s painting Ginevra de’ Benci (see Fig. 6) in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and with those found in the above-mentioned marble sculpture in the Frick Museum, A Young Woman, given to Andrea del Verrocchio. (Valentiner had made a study of Leonardo’s work in Verrocchio’s workshop.) In 1991 Piero Adorno, specifically identified the Detroit picture as Verrocchio’s lost portrait of Lucrezia Donati. Notwithstanding seeming correspondences with secure works, this picture is now relegated to “An Imitator of Verrochio” – and this is an extremely charitable formulation. In Virtue and Beauty, 2001, David Alan Brown described it as “a probable forgery by its anachronistic materials and unorthodox construction”. “Probable” [!] because: “after a recent technical examination, the picture turns out to have been painted on photographic paper applied to a wood panel that was repaired before it was readied for painting. And at least one of the pigments employed – zinc white – is modern…” Valentiner judged one of two Leonardo studio works of the Madonna with a Yarnwinder to be “more beautiful than the Mona Lisa”.

The portrait on the right, A Young Woman, was attributed to Piero Pollaiuolo by Berenson in 1945. While this figure is perhaps the most attractive of the above three, with its nicely constructed counterbalancing of the thrusts in the neck/head and torso, and its credibly proportioned arm, the work itself has, so far as we can ascertain, sunk without trace. In truth, this female profile portrait type has been assailed by forgeries. Alison Wright notes in her 2005 book The Pollaiuolo Brothers, that “Complications for the historian lie both in the fact that the subjects of most female portraits are no longer identifiable and that, because of their exceptional decorative and historical appeal, such portraits were highly sought after by later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century collectors, encouraging a market for copies, fakes and over-ambitious attributions.”

The portrait in the centre (“La Bella Principessa”) has been precisely attributed by Kemp to Leonardo as a book illustration portrait of Bianca Sforza of 1495-96.

DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN THE LOOKS OF THEN OF NOW

Above, Fig. 2. In My dear BB (an incalculably valuable new resource edited and annotated by Robert Cumming), we learn that in November 1930 Kenneth Clark’s wife, Jane, wrote to Berenson: “K has seen Lord Lee’s two new pictures…The Botticelli Madonna and Child you probably know too. K thinks the latter may be genuine about 1485 or rather part of it may be, but it is not a pretty picture…” A footnote discloses that Lee had bought The Madonna of the Veil, a tempera painting on panel in 1930 from an Italian dealer for a then huge sum of $25,000 (Fig. 3). It was widely accepted by scholars as autograph Botticelli and published by the Medici Society as a “superb composition of the greatest of all Florentine painters”. Clark, doubting the attribution on sight, objected that it had “something of the silent cinema star about it” – and he likened the Madonna to Jean Harlow (Fig. 3). Lee donated the picture to the Courtauld Institute Gallery in 1947. In June 2010 Juliet Chippendale (a National Gallery curatorial intern working in association with the Courtauld Institute MA course) disclosed that scientific examination had identified pigments not known before the 18th and 19th centuries and worm holes that had been produced by a drill. It is now designated a work of the forger Umberto Giunti (1886-1970), who taught at the Institute of Fine Art in Siena and forged fresco fragments.

ART HISTORICAL SILENCES

Four months later Clark wrote to Berenson: “Just in case Lee has sent you a photograph of his new Botticelli may I ask you to forget anything Jane may have reported me as having said of it. It is one of those pictures about which it is best to be silent: in fact I am coming to believe it is best for me to be silent about every picture. Did I tell you that my Leonardo book was a mare’s nest. The man had sent photographs of two drawings from the middle of the Codice Atlantico. They must have been early copies done with some fraudulent motive – perhaps the book really did belong to Leonardo – he certainly had read it – & some pupil thought to enhance its value.”

Above Fig. 3. The young Kenneth Clark (then twenty-seven years old) displayed an admirable “eye” by spotting a fraud on sight some eighty years ahead of the pack. Is it better for a connoisseur to see but not speak than it is not to see at all? Undoubtedly, it is. Would Clark have enjoyed his meteoric rise had he humiliated the mighty and exposed the big-time fraudsters of his day? (That question might be taken as self-answering.) If Clark bided his time on Berenson, eventually he delivered an unforgiving former-insider’s repudiation in 1977 by chronicling how Berenson had “sat on a pinnacle of corruption [and] for almost forty years after 1900… [done] practically nothing except authenticate pictures”

PRETTY – AND NOT SO PRETTY – WOMEN

Above, Fig. 4. In the middle and bottom rows we see three bona fide works of the female profile type – respectively:

Portrait of Bianca Maria Sforza, c. 1493, by Ambrogio de Predis, The National Gallery of Art, Washington;

Domenico Ghirlandaio’s 1488-1490 Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid; and,

a portrait of Beatrice d’Este tentatively attributed by Kemp to Ambrogio da Predis.

The differences between this trio and the works in the top row are pronounced and eloquent. The secure works are highly individuated and immensely richer in their effects. Collectively, they do not constitute an inadvertent suite. Individually, they are greatly more various compositionally. Collectively, they are markedly richer in jewellery and ostentatiously sumptuous costumes. The distinctive physiognomies of their subjects derive from living persons, not from other art or photographs of other art. Flattery and loving attention are channelled more into the costume and bling than into the facial features. In every respect the opposite is the case in the top row where prettiness has been held at a premium with an eye on the modern photographically-informed market.

LEONARDO BREAKS THE MOULD

Above, Fig. 5: As mentioned, “La Bella Principessa” and her two companions are of a piece, and of a type never followed by Leonardo whose female portraits (see below) pioneered an unprecedentedly complex and sophisticated evocation of real, sculpturally palpable women in tangible spaces or landscapes. To include the figurally impoverished and stylistically anachronistic “La Bella Principessa” in Leonardo’s oeuvre would disjunct his revolutionary arc of insights and innovations in portraiture. Such inescapably disruptive consequences have been ceded tacitly by Kemp, “La Bella Principessa’s” principle defender – some say advocate. In “La Bella Principessa ~ The Story of the New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci” (Kemp’s 2010 book jointly written with Pascal Cotte of Lumiere Technology and including chapters by the drawings scholar Nicholas Turner and the recently discredited fingerpints expert Peter Paul Biro), Kemp converts an intractable problem into an asset by begging the essential question. That is, he underwrites “La Bella’s” credibility on an assertion that “Any important new work, to establish itself, must significantly affect the totality of Leonardo’s surviving legacy over the longer term.” Without question, the de-stabilising inclusion of “La Bella Principessa” would produce knock-on effects, but arguing backwards from that predictable disturbance to some endorsement of its source is patently unsound methodologically – the inclusion of any atypical work, whether bona fide or forged, into an oeuvre would affect its “legacy”.

LEONARDO’S ACCOMPLISHMENTS

Above, top, Fig. 6: Left, Andrea del Verrocchio’s Lady with a Bunch of Flowers of c. 1475; and (right) Leonardo’s (hypothetically extended) Ginevra de’ Benci of c. 1474-1478.

Above, Fig. 7: Left, Leonardo’s The Lady With an Ermine of about 1489-90; centre, Leonardo’s La Belle Ferronnière of about 1495-96; right, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa (La Giaconda) of about 1503-06 onwards.

In the group above we see extraordinary development in Leonardo’s portraits of women over the last quarter of the fifteenth century as he strove to incorporate the entirety of sculptural, plastic, figural knowledge, and to surpass it by making it dance to an artistically purposive tune liberated from the happenstance, arbitrary lights of nature on which sculpture then necessarily depended. Some have attributed the Bargello sculpture, the Lady with a Bunch of Flowers, to Leonardo on the grounds that its subject was Ginevra de’ Benci, the subject of Leonardo’s painting. Others have seen Leonardo’s authorship of it in the beauty of the hands. In Leonardo da Vinci and the Art of Sculpture, 2010, Gary M. Radke holds that the two works show differences that emerged in the mid-1470s between the two artists. Against this, it has been suggested that the painting might originally have borne a closer relationship to the sculpture with a possible inclusion of hands in a fuller length treatment. A study of hands by Leonardo was incorporated in a hypothetical and digitally realised extension of the painting by David Alan Brown (Virtue and Beauty, 2001, p. 143). Frank Zollner sees the painting as marking the point (1478-1480) at which Leonardo broke away from “the profile view traditionally employed in Florence for portraits of women” in favour of the three-quarters view in order to impart “a pyschological dimension to his sitter – something that would become the hallmark of Renaissance portraiture”. Which is all to say that Leonardo had broken away from the profile convention some sixteen to eighteen years before, on Kemp’s hypothesis, he made a solitary and exceptional “return” to it.

Speaking of the reconstruction of Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci painting, Brown writes:

“Ginevra’s portrait, the lower part of which was cut down after suffering some damage, may have included hands. A drawing of hands by Leonardo at Windsor Castle, assuming it is a preliminary study, aids in reconstructing the original format of the picture. As reconstructed, Leonardo’s portrait may be seen to have broken with the long-standing Florentine convention of portraying women in bust-length profile. In seeking an alternative to the static profile, Leonardo, like Botticelli, seems to have turned to Verrocchio’s Lady with a Bunch of Flowers in the Bargello, Florence. Because of the sitter’s beautiful hands which mark an advance over the earlier head-and-shoulders type of sculpted bust, the marble has even been attributed to Leonardo. But the highly innovative conception of the half-length portrait bust is surely Verrocchio’s achievement. What young Leonardo did was to was to translate this sculptural protype into a pictorial context, placing his sitter into a watery landscape shrouded in a bluish haze…”

A CASE CONSPICUOUSLY NOT MADE

For the owner and the art historical proponents of “La Bella Principessa”, the very chronology of Leonardo’s female portraits constitutes an obstacle. Given Leonardo’s famous eschewal of strict profile depictions of women, the onus is on those who would include “La Bella Principessa” (- albeit as a solitary and exceptional stylistic regression that was undertaken without ever attracting attention or comment) to make a double case.

First, they must show how and where “La Bella Principessa” might plausibly have fitted within the trajectory of Leonardo’s accepted works. Second, they must demonstrate by comparative visual means that “La Bella Principessa” is the artistic equal of the chronologically adjacent works within the oeuvre. Kemp has proposed the precise date of 1495-96 for the execution of “La Bella Principessa” but, conspicuously, has not presented direct, side-by-side visual comparisons with Leonardo’s paintings. Instead of comparing “La Bella Principessa” of 1495-6 directly with Leonardo’s La Belle Ferronnière of about 1495-6, Kemp writes:

“If the subject of Leonardo’s drawing is Bianca, it is likely to date from 1495-6. In style, it seems at first sight to belong with his earlier works rather than to the period of the Last Supper. However, Leonardo was a master of adapting style to subject. Just as his handwriting took on an earlier cast when he needed to adopt a formal script, so his drawing style could have reverted to a meticulous formality, appropriate for a precious set-piece portrait on vellum of a Sforza princess.”

“If”? “Could have”? “At first sight”? The pro-attribution literature is bedecked with daisy-chains of such tendentious and weasel words and terms. With which earlier works is “La Bella Pricipessa” deemed to be artistically comparable or compatible? With the Ginevra de’ Benci of c. 1474-1478? With The Lady With an Ermine of about 1489-90? Never mind the red herrings of handwriting and the giant, near-obliterated historical figures of the Last Supper, what of the relationship with Leonardo’s (supposedly) absolutely contemporaneous La Belle Ferronnière of 1495-96? (On this last we volunteer a pair of comparisons below.)

Above, Top, Fig. 8: Leonardo’s La Belle Ferronnière, left, and the “La Bella Principessa”.

Above, Fig. 9: Details of Leonardo’s La Belle Ferronnière, left, and the “La Bella Principessa”.

Kemp insists: “The Lady in profile [“La Bella Principessa”] is an important addition to Leonardo’s canon. It shows him utilizing a medium that has not previously been observed in his oeuvre…It testifies to his spectacular explosion and development of novel media, tackling each commission as a fresh technical challenge. It enriches our insights into his role at the Milanese court, most notably in his depiction of the Sforza ‘ladies’ – whether family members or mistresses. Above all, it is a work of extraordinary beauty.”

Even if we were to assume that for some reason Leonardo had opted to “revert” in 1496 to a type he had never employed, what might explain a pronounced indifference in “La Bella Principessa” to the detailed depiction of the “stuffs” of costume with which the artist was simultaneously engaged in La Belle Ferronnière? Given that Leonardo clearly appreciated and celebrated the fact that courtly costume required sleeves to be made as independent garments held decorously in place by ribbon bows so as to permit undergarments to peep through; and, given that Leonardo lovingly depicted not only the varying thicknesses of the costume materials but every individual twist in the threads of the elaborately embroidered band in La Belle Ferronnière, how could he possibly – when working for same ducal master, at the same time – have been so negligent and indifferent in the execution of “La Bella Principessa’s” costume? Kemp acknowledges and offers excuse for the distinct poverty of the costume: “It may be that the restraint of her costume and lack of celebratory jewellery indicates that the portrait was destined for a memorial rather than a matrimonial volume.” In so-saying, he jumps out of one frying pan into another.

If “La Bella Principessa” was made after Bianca Sforza’s death, from whence did the likeness derive? One reason why Kemp settled on Bianca as the preferred candidate subject for “La Bella Principessa” was that while (disqualifying) likenesses of the other Sforza princesses existed, none survives for her – she is an image-free figure. Kemp offers no indication of a possible means for Leonardo’s (hypothesised) post-death conjuring of Bianca’s supposed likeness other than to claim that “Leonardo has evoked the sitter’s living presence with an uncanny sense of vitality.” This again begs the crucial question and fails to consider any alternative explanations for the image’s qualities. (We will be showing how the profile of “La Bella Principessa” could well have been a “portmanteau” composite image assembled from one particular work of Leonardo’s and from that of another, unrelated painter.)

The most strikingly “Leonardesque” feature on the costume of “La Bella Principessa” – the knot patterning around the (implausible) triangular slash in the outer garment – is a source of further concern and constitutes evidence of forgery. First, the motif on which much effort will have been expended, is brutally cropped along the bottom edge of the sheet, as if by a careless designer laying a photograph into a book. Why would any Renaissance artist, let alone Leonardo, design a complicated feature so as to “run it off the page”? Further, the illusion of form (created by lights and shades) in the patterning is feeble in the extreme for Leonardo – as when compared with his treament of relief seen in the above embroidered passage in La Belle Ferronnière, for example. Leonardo probably better understood than any artist in history the vital connection between a thing made and a thing depicted. He took bodies and organs apart to understand their construction and he sought to create mental models that would make the otherwise terrifyingly arbitrary and capricious forces of nature graspable if not checkable. Most seriously of all, as our colleague Kasia Pisarek has noted and reported, while the patterning present on “La Bella Principessa” matches none found in any work of Leonardo’s, it more closely matches that found in a carved marble bust by Gian Cristoforo Romano in the Louvre – see “La Bella Principessa – Arguments against the Attribution to Leonardo”, Kasia Pisarek, artibus et historiae, no. 71, 2015. (To receive a pdf of Dr Pisarek’s article please write to: news.artwatchuk@gmail.com )

Michael Daley, 24 February 2012.

In Parts II and III we examine: the provenance of “La Bella Principessa” and the work’s problematic emergence from within the circle of Bernard Berenson; the claim by the forger Shaun Greenhalgh to have produced “La Bella Principessa” in Britain in the 1970s; the spurious “left-handed-ness” of “La Bella Principessa” and the low quality of, and the means by which the drawing was made…

Connoisseurship in Action and in Peril

“WHEN THE FIRST catalogue of the Ashmolean Museum’s Sculpture collection (in three volumes) was undertaken more than twenty-five years ago, the present author decided to exclude works made before 1540…”

“…The decision was partly determined by the quantity of the material but also in recognition of the special attention that the finest of the small bronzes given and bequeathed by Charles Drury Fortnum deserved. It is indeed because of these that the Ashmolean’s sculpture collection is the most important in the United Kingdom after that of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London…”

Above and below: The ‘Fortnum Venus’, attributed to Francesco Francia or his circle. c. 1500-05. Bronze, 26.1 cm. high. (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford).

Above, detail of St Jerome, by Cosimo Tura. c.1470. Panel, 101 by 57.2 cm. (National Gallery, London).

“The first of Jeremy Warren’s three volumes under review here includes these very figures. One of them is the

exquisite Venus associated with the Bolognese painter and goldsmith Francesco Francia (cat. No.20). It is one of the earliest responses in the Renaissance to the antique female nude, and perhaps belonged to a narrative group for, as her drapery falls, her hand is cupped as if to receive the apple from Paris…”

“…In conclusion it should be noted that the cataloguing of the permanent collection is not now often considered an essential part of the curator’s job. Any museum director who is chiefly an impresario is inevitably attentive to fashionable ideas and taste, whereas the cataloguer of a permanent collection is bound to give his or her attention to neglected artists, and to works by artists in which they are not initially interested, but which beg the question as to why the appealed to their predecessors – collectors, scholars and curators long deceased. This provides an antidote not only to the narrow outlook of the popular exhibition machine, but to that of academic institutions where scholars, having achieved promotion by imitating their seniors, are obliged to compete in appealing to the young consumers upon

whose favour the prosperity of the institution depends.”

~ NICHOLAS PENNY: “Sculpture in the Ashmolean”, Burlington Magazine, January 2016. A review of Catalogue: Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture. A Catalogue of the Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, by JEREMY WARREN, 3 vols., continuously paginated, 1188 pp. incl. numerous col. + b. & w. ills. (Ashmolean Publications, Oxford, 2014, £395.)

“FIVE NEW YEAR BLOCKBUSTERS

“It’s a new dawn, it’s a new day… what new art exhibitions will make you feel good? Read our list of the top five shows opening this season to get inspired.

“Discover the enduring impact of Botticelli and Delacroix on the art world and prepare to be star struck at exhibitions celebrating 100 years of British Vogue and the incredible beauty of our Solar System.

“Need a second opinion? Watch art historian Jacky Klein’s guide to the season’s unmissable art exhibitions.”

~ THE ART FUND, a mailing, 8 December 2016.

PERMANENT EVOLUTION – A JOB FOR LIFE

“Museums have become places where we take part in social as well as learning activity. It is easy to be cynical about

the impact of the café, restaurant or shop spaces on the culture and character of museums, but such facilities have made museums less daunting, more welcoming and more open to general visitors. However, such [democratization] needs to go deeper than the provision of opportunities to purchase or to consume.”

NICHOLAS SEROTA, the director (- since 1988) of the Tate, at the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul.

HOW ART HISTORIANS CAN BE FOOLED BY CONDITION

“One of the most influential books in the twentieth-century art history was Erwin Panofsky’s Studies in Iconology. In this seminal work, the very latest German approaches and method were presented to an Anglo-Saxon audience for the first time. One of the dazzlingly learned chapters was devoted to the figure of Cupid wearing a blindfold, and Panofsky showed how this theme could be traced back to the writings of the medieval moralists. For thinkers of this Christian stamp, lovers were metaphorically blind, since they were ‘without judgement or discrimination and guided by mere passion’. But later, in the Renaissance, ‘moralists and and humanists with Platonizing leanings’ contrasted the figure of the blindfold Cupid with another kind of…”

~ PAUL TAYLOR. Introduction, CONDITION The Ageing of Art, Paul Holberton Publishing, 2016. ISBN 978 1 907372 79 7

Illustration: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Composer Luigi Cherubini with the Muse of Lyric Poetry, 1842, detail.

“…Although Bode was extremely learned in many branches of art history and had his information always ready – he had little need of written notes and photographs – he was no scholar in the true sense. He was more fond of action than reflection, and was far from having a just and objective mind. Moreover, the distracting practice of uninterrupted daily work hindered a comprehensive synthesis of realization. The deepest motive of the scholar, namely, disinterested love of truth, could not function productively in a nature always resolutely aiming for effectiveness and visible results. Bode was utterly unphilosophical, he considered no affair from more than one side. He saw black or white, good or bad, advantageous or inimical; he knew no intermediary steps. To forsee obstacles, to fear, to guard against them was not his way. Consequently he became angry as soon as he encountered opposition. He made more mistakes by acting than by failing to act. He was a hunter, not an angler.”

~ Max J. Friedländer – Reminiscences and Reflections, Edited from the literary remains and with a foreword by

Rudolf M. Heilbrunn, 1969, New York.

“…Anyway, getting back to the book that was sent to me, its title was rather grand and pompous: La bella Principessa – the beautiful princess. Or, as I knew her, ‘Bossy Sally from the Co-op’. I’m a bit unsure of how to talk of this because the book was written by an eminent Oxford professor and must have been quite an effort. I don’t want to ruffle any feathers or cause problems but I nearly swallowed my tongue on reading its supposed value – £150 million! It would be crazy for a public body to pay such a sum. So I feel the need to say something about it.

“The drawing is thought by some to be a work by Leonardo da Vinci, but it does divide opinion and it wasn’t included in the National Gallery’s Leonardo show of 2011, a show which I thought was really well done except for it being staged ‘underground’ in the Sainsbury Wing basement…

“I drew this picture in 1978…It was done on vellum, quite a large piece to find unfolded and without crease lines. I did it on vellum because at that time I couldn’t make old paper yet…The first thing I had to do was sand off the writing with 600-grit wet and dry paper. That done, it looked too new for anything old to look right on it, so I turned it over and did the drawing on the other side. That is why the drawing is done on the hair side of the vellum instead of the much-preferred ‘flesh side’. The texture of the sanding should still seen on its reverse.

“As I said, the face is of 1970s vintage, and I think that shows in the drawing…The drawings of Leonardo and Holbein especially have always impressed me with their fineness of line and detail, and in my view they must have been done under some magnification…The vellum is mounted on an oak board…before drawing on it, the vellum was stuck to the backboard with cabinet maker’s pearl glue, so it needed to be under a weighted press for a while to allow the glue to go off without ‘cockling’ the vellum. ‘Cockling’ is the effect you see on paper when you try to paint a watercolour without soaking and stretching the paper first. On vellum the dampness looks like blisters or a cockle bed on the shore. It’s caused by the water content of the glue, so the thing needs to be under a heavy press to dry it flat.

“After a bit of experimentation, and just to prove a point to myself, I lightly traced the drawing I’d invented onto the vellum (I’m sure the graphite can still be detected) and started to draw the image in hard black chalk – carbon black in gum arabic – using a pair of jeweller’s magnifying glasses. It took some time to get used to working like that, and I had to go to back to practising on papper for a while so as not to bugger things up…

“It was done in just three colours – black white and red – all earth pigments based in gum arabic, with the carbon black mostly gone over with oak gall ink. To be a bit Leonardo-like or even Holbein-like – they were both left-handers – I put in a left-hander’s slant to it…The Leonardo book [“La Bella Principessa ~ The Story of the New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci”, By Martin Kemp and Pascal Cotte, with contributions by Claudio Strinati, Nicholas Turner and Peter Paul Biro] seems to put great store by the apparent leftyness of the drawing, but it can be shown up very easily. With the face on the vellum facing left, just turn the drawing clockwise to face her skyward, and hatch strokes from profile outwards in the normal manner…Incidentally, the book points out a palm print on the neck area, just the spot a right-hander doing an impersonation of a left-hander might rest their hand whilst doing the background hatching.

“Although I am no Oxford professor, I could list umpteen reasons for not thinking this drawing to be by leonardo…

The book mentions several holes on one margin as evidence that it has been bound into a volume, and also mentions some later ‘restoration’. I did not do these things, and don’t know who did, or where it went on its later travels. Looking closely at the picture in the book, it looks to have had the left margin peeled back an inch or so and has been restuck, not very well, especially at the bottom left. Could this be from when the left margin was pierced and roughly re-cut by someone else?

“I sold it for less than the effort that went into it to a dealer in Harrogate in late 1978 – not as a fake, or by ever claiming it was something it wasn’t. I can’t really say any more on it. At least it may now be known for what it is.”

~ SHAUN GREENHALGH – A Forger’s Tale, Published by ZCZ Editions in 2015

In the past it was customary for scholars to advance claims of attribution for particular works of art in scholarly journals and then wait to see how peers and colleagues responded to their evidence and arguments. Increasingly, we are seeing co-ordinated promotional campaigns of advocacy by players and owners who eschew venues of debate and sometimes denigrate sceptics and opponents. We invited two of the leading advocates of “La Bella Principessa’s” Leonardo’s authorship – Martin Kemp and Nicholas Turner – to speak at our recent conference on connoisseurship. Both declined. Neither our post of January 2014 (“Art’s Toxic Assets and a Crisis of Connoisseurship ~ Part II: Paper – sometimes photographic – Fakes and the Demise of the Educated Eye”) nor our colleague Kasia Pisarek’s article “La Bella Principessa: Arguments against the attribution to Leonardo” that was published in the June 2015 issue of the scholarly journal artibus et historiae have been challenged in print.

(For a pdf copy of Kasia Pisarek’s article, please write to: news.artwatchuk@gmail.com. For our conference, see Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship and Recap of Art, Law and Crisis of Connoisseurship Conference.)

The da Vinci Detective: Art Historian Martin Kemp on Rediscovering Leonardo’s Tragic Portrait of a Renaissance Princess – an ARTINFO Interview by Andrew M. Goldstein, 17 October 2011. Extracts:

…[Andrew Goldstein] “They weren’t the only ones to differ on the attribution of the painting, and when you first announced that you believed it to be a Leonardo, a lot of people disagreed. One museum director even told the Telegraph’s Richard Dorment, anonymously, that it was a “screaming 20th century fake, and not even close to Leonardo himself.” Has there been any reversal since then?

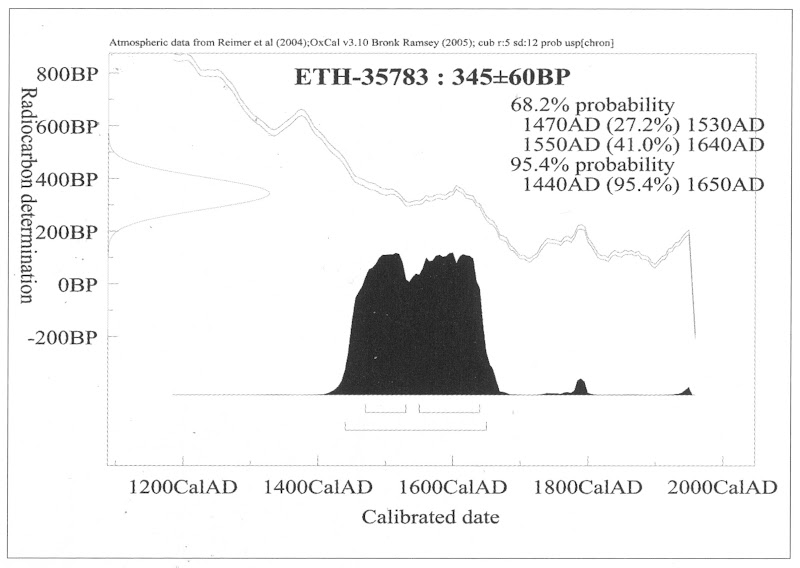

[Martin Kemp] “I don’t know who this anonymous person was, but we carbon-dated the parchment and that eliminates it from being a screaming modern forgery. If it were a forgery, it used things that we’ve only recently discovered about Leonardo’s technique in the last 20, 30 years. The fact that it was owned by Giannino Marchig takes it outside the period when it could be a forgery, knowing what we know now, so that’s not an option. The ultra-violet turns up retouching, and it’s very clear it has been heavily restored, but most objects 500 years old, including the “Salvator Mundi”, which is the new picture being shown in the National Gallery.

[…] “One thing that critics of your ‘Principessa’ attribution tend to bring up is the involvement in your research of Peter Paul Biro, a fingerprint expert whose credibility was questioned. What is your opinion of him?

“Well, Biro I knew of as someone who’d specialized in fingerprints and paintings, so we asked him to look at the fingerprint that is in the upper left side of the ‘Bella Principessa.’ I had data on finger prints and finger marks in other Leonardo paintings, and he said one of these matched – not astoundingly, because it’s just the tip of a finger, and one doesn’t rely on fingerprints on vellum. It wouldn’t convict anybody in a court of law. You need more than that. So he did a limited job here, and we didn’t depend too much on that evidence. The press liked it, of course because it was cops and robbers stuff.

“I would not now probably say much about it at all, because on reflection I don’t think we have an adequate reference bank of Leonardo fingerprints. I’ve talked to fingerprint specialists, and they typically require a full set of reference prints. We don’t have that for Leonardo. My sense is – and this is Pascal’s sense, too – that it’s probably premature, given what we know about Leonardo’s fingerprints, to come up with matches at all. But the job Biro did was perfectly straightforward. There were no grounds for dishonesty. Peter Paul Biro is suing the New Yorker*, but I can’t comment at all upon the court case because that’s about things that I know nothing about, so it’d be totally improper. But he did work for us, which I now, let’s say, place less reliance on, simply because, on reflection, I think the fingerprint evidence is rather slippery.

“Because of the work you have done to bring the ‘Principessa’ into the fold of acknowledged Leonardos, some say you have crossed from the realm of scholarship to something more like advocacy. How do you explain your passion for the portrait?

“I would say that one of the differences between being a historian of art and being a scientist, as I was trained, is that you’re dealing with objects that are deliberately communicating with something other than just our intellect. So, for me, it’s not a dry process. You begin with the feeling it’s special, and if it stands up to the research, you end with the feeling that it’s special, and I make no apology for that. I’ve been critized as acting as an advocate for it, but if I’m writing, as I am in ‘Christ to Coke’, about the ‘Mona Lisa’, I’m an advocate for that too, because it’s a miraculous picture. Also, when I’m writing about the Coke bottle, I’m not an advocate for Coke as a drink. I hate it. But it’s one of the all-time great

bits of product design and I’m happy to say that.”

“*THE MARK OF A MASTERPIECE” by David Grann, The New Yorker, 12 July 2010 ~ Extracts:

[1] “But he [Martin Kemp] also relies on a more primal force. ‘The initial thing is just that immediate reaction, as when we’re recognizing the face of a friend in a crowd,’ he explains. ‘You can go on later and say “I recognize her face because the eyebrows are like this, and that is the right colour of her hair,” but, in effect, we don’t do it like that. It’s

the totality of the thing. It feels instantaneous.'”

[2] “Moreover, according to [the curator of Drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Carmen] Bambach, there was a more profound problem: after studying an image of the drawing [La Bella Principessa] – the same costume, the same features, the same strokes that Kemp examined – she had her own strong intuition. ‘It does not look like a Leonardo’, she said.”

[3] “When such a schism emerges among the most respected connoisseurs, a painting is often cast into purgatory. But in January, 2009, Kemp turned to a Canadian forensic art expert named Peter Paul Biro who, during the past several years has pioneered a radical new approach to authenticating pictures. He does not merely try to detect the artist’s invisible hand; he scours a painting for the artist’s fingerprints, impressed in the paint on the canvas. Treating each painting as a crime scene, in which an artist has left behind traces of evidence, Biro has tried to render objective what has historically been subjective. In the process he has shaken the priesthood of connoisseurship, raising questions about the nature of art, about the commodification of aesthetic beauty, about the very legitimacy of the art world.Biro’s research seems to confirm what many people have long suspected: that the system of authenticating art works can be arbitrary and, at times, a fraud.”

[4] “Biro asserted that he had uncovered the painting’s ‘forensic provenance,’ telling a reporter, ‘The science of fingerprint identification is a true science. There are no gray areas.’ Having developed what he advertised as a ‘rigorous methodology’ that followed ‘accepted police standards,’ he began to devote part of the family business to authenticating works of art with fingerprints—or, as he liked to say, to ‘placing an artist at the scene of the creation of a work.'”

[5] “But the International Foundation for Art Research, a nonprofit organization that is the primary authenticator of Pollock’s works, balked, saying that Biro’s method was not yet ‘universally’ accepted.

[6] “In 2009, Biro and Nicholas Eastaugh, a scientist known for his expertise on pigments, formed a company, Art Access and Research, which analyzes and authenticates paintings. Biro is its director of forensic studies. Clients include museums, private galleries, corporations, dealers, and major auction houses such as Sotheby’s. Biro was also enlisted by the Pigmentum Project, which is affiliated with Oxford University.”

[7] “Biro told me that the divide between connoisseurs and scientists was finally eroding. The best demonstration of this change, he added, was the fact that he had been commissioned to examine ‘La Bella Principessa’ and, possibly, help make one of the greatest discoveries in the history of art.”

[8] “After he first revealed his findings, last October, a prominent dealer estimated that the drawing [‘La Bella Principessa’] could be worth a hundred and fifty million dollars. (The unnamed ‘lady’ who had sold it at Christie’s for less than twenty-two thousand dollars came forward and identified herself as Jeanne Marchig, a Swedish animal-rights activist. Citing, among other things, the fingerprint evidence, she sued the auction house for ‘negligence’ and ‘breach of warranty’ for failing to attribute the drawing correctly.)”

[9] “Ellen Landau, the art historian, said that she was ‘absolutely convinced’ that the paintings were by Pollock. Biro was sent a photograph of a fingerprint impressed on the front of one picture. He identified six characteristics that corresponded with the fingerprint on the paint can in Pollock’s studio—strong evidence that the work was by Pollock. But, as more and more connoisseurs weighed in, they noticed patterns that seemed at odds with Pollock’s style. Meanwhile, in sixteen of twenty art works submitted for analysis, forensic scientists discovered pigments that were not patented until after Pollock’s death, in 1956. At a symposium three years ago, Pollock experts all but ruled out the pictures. Ronald D. Spencer, a lawyer who represents the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, told me, ‘Biro can find all the fingerprints he wants. But, in terms of the marketplace, the Matter paintings are done. They are finished.'”

[10] “Reporters work, in many ways, like authenticators. We encounter people, form intuitions about them, and then attempt to verify these impressions. I began to review Biro’s story; I spoke again with people I had already interviewed, and tracked down other associates. A woman who had once known him well told me, ‘Look deeper into his past. Look at his family business.’ As I probed further, I discovered an underpainting that I had never imagined.”

[11] “During the eighties and early nineties, more than a dozen civil lawsuits had been filed against Peter Paul Biro, his brother, his father, or their art businesses. Many of them stemmed from unpaid creditors. An owner of a picture-frame company alleged that the Biros had issued checks that bounced and had operated ‘under the cover’ of defunct companies ‘with the clear aim of confusing their creditors.’ (The matter was settled out of court.) As I sifted through the files, I found other cases that raised fundamental questions about Peter Paul Biro’s work as a restorer and an art dealer.

[12] “Biro refused, multiple times, to divulge where he had obtained either of the paintings. According to the Wises, Biro insisted that the person who sold him the paintings was in Europe, and that it was impossible to contact him.

[13] “Sand sought proof of a financial transaction—a check or a credit-card payment—between Biro and Pap. Biro, however, said that he had obtained them in exchange for two musical instruments: a Steinway piano and a cello.

[14] “Sand was incredulous: ‘Is Mr. Pap a music dealer or is he an art dealer?’ After Biro could not recall where he had originally purchased the cello, Sand suddenly asked him, ‘You ever been convicted of a criminal offense, sir?’

‘No.’

‘You are certain of that?’

‘Yes,’ Biro said.”

[15] “Throughout the trial, the Biros and their attorneys maintained that the two paintings sold to the Wises were authentic, but to make their case they presented an art expert who was not a specialist on Roberts, or even on Canadian art. On September 3, 1986, the court found in favor of the Wises, and ordered Peter Paul and Geza Biro to pay them the seventeen thousand dollars they had spent on the pictures, as well as interest.”