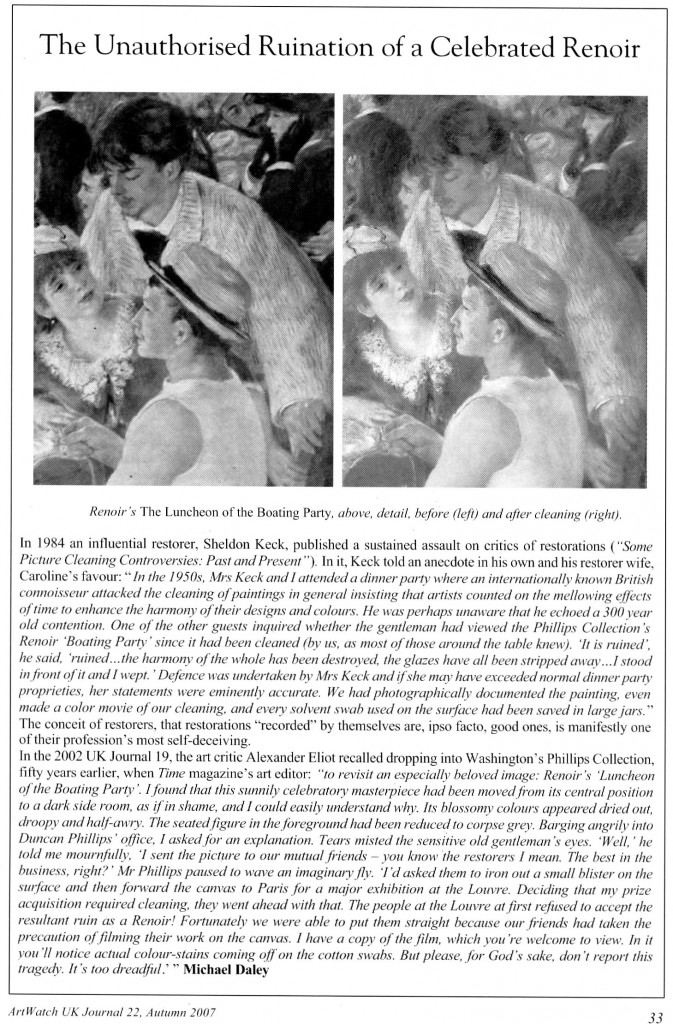

Rodin and ancient Greek art – a personal view of a magnificent show

Last night we were bidden, as Sir Roy Strong might have put it, to the opening and reception of the joint British Museum and Rodin Museum exhibition “Rodin and the art of Greece”.

It proved an extraordinary and privileging occasion that was close to our heart in very many respects. Guests were ushered into a corner of the Great Court for drinks and canapés. In that dwarfing space the buzz of expectation among the small standing groups resembled a Royal Opera House opening of Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. The company was illustrious. Among the many VIPs, journalistic aristocracy was present in Sir Simon Jenkins of the Guardian and Lord Gnome of Private Eye. The Two Greatest Living British Sculptors were represented by Sir Anthony Gormley R. A. (who sported some Palestinian headwear around his neck). The British Museum’s new director, Hartwig Fischer, opened the speeches well and graciously. The man from the generous sponsors, Bank of America, Merrill Lynch, followed and the French Ambassador opened the exhibition itself with certain ironical asides about the virtues of European cooperation. And we then poured into the exhibition.

As others have already indicated, this show, the combined product of a great dedicated artists’ museum and a great “universal” encyclopaedic museum, is simply stupendous. On entry, the shock of the space and its fabulous contents was also operatic: a beautifully lit elegantly constructed chip-board “set” snakes down the centre of the otherwise soul-less and dispiriting Lord Rogers’ black box, which, thankfully on this occasion, has been opened to disclose a courtyard. The continuous low plinth carries the larger, show-stopping sculptures and creates subsidiary spaces that house drawings and smaller works. Sparks fly between the works on display. The labels are good and the catalogue is exemplary. If the essential message of this engagement of a giant of modernism (Rodin) with a legendary classical artist (Phidias) – that to advance we must look back – seems subversively reactionary in today’s art world, so much the worse for us. But for this artist, the timing feels optimal: Modernism is a spent and disintegrating force. Its void is filling with assorted non-artistic activisms and relativisms.

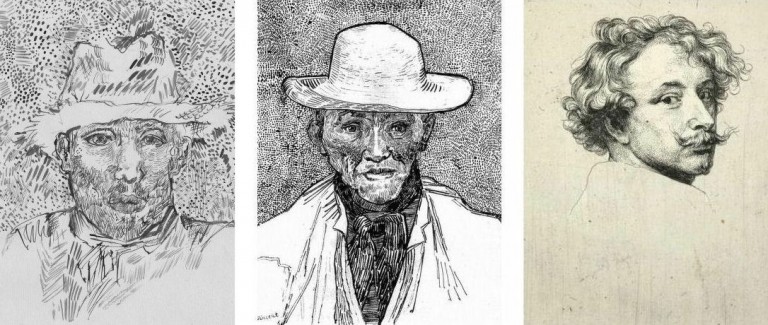

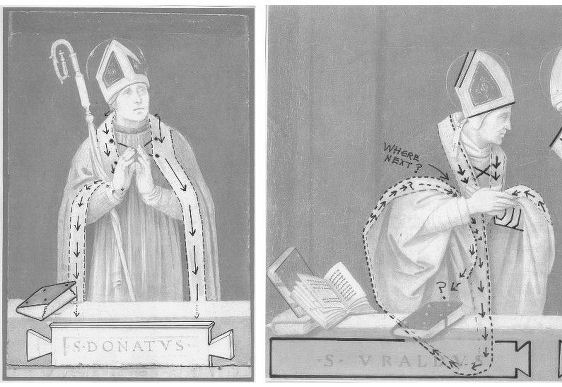

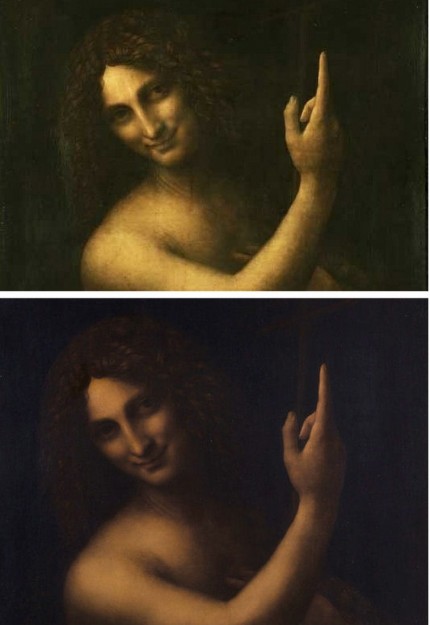

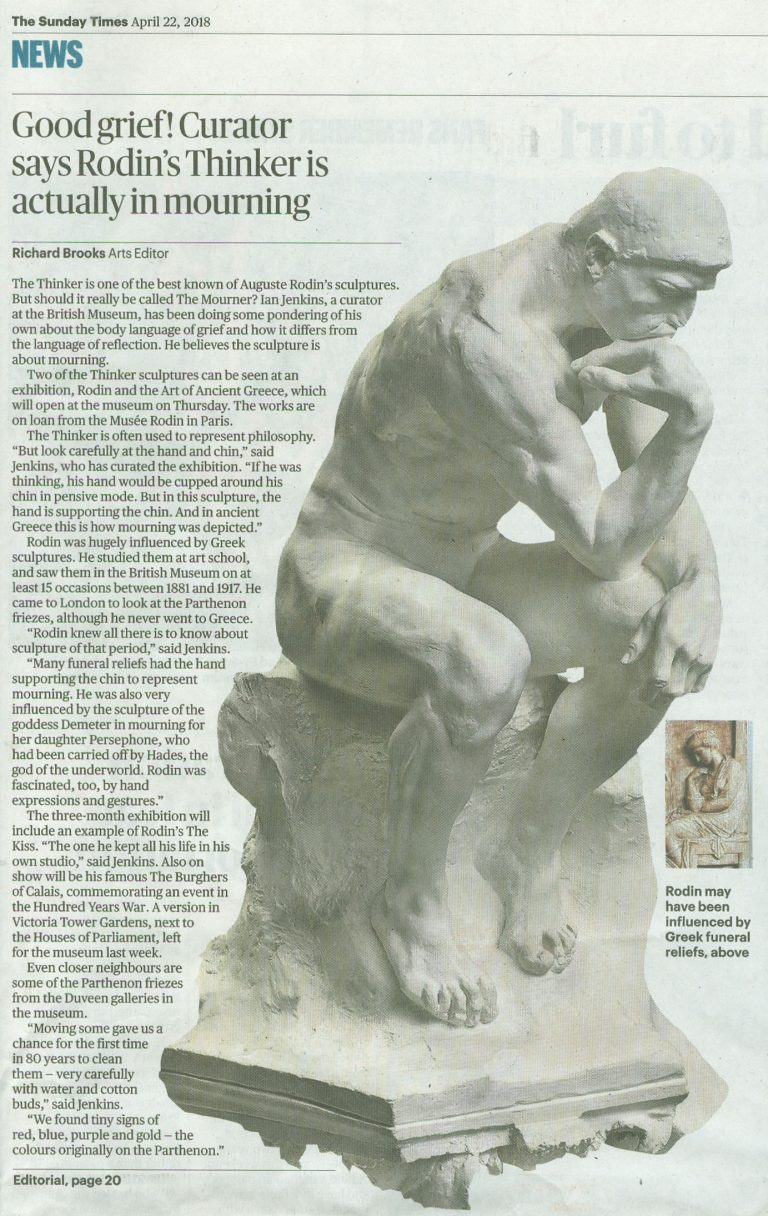

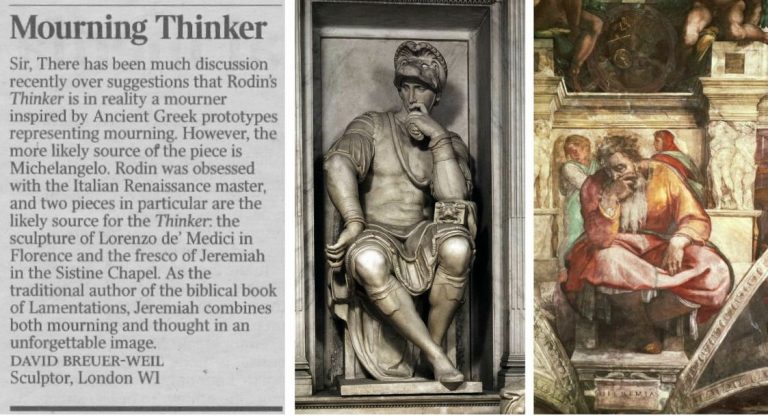

The show is welcome in other respects. It springs from the strengths of museum curators working to their departmental briefs, in this case that of Ian Jenkins, a very fine classical scholar, who himself, as it happens, has carved stone. Even before the show opened Jenkins was creating sparks of his own. He had noticed a distinct echo in Rodin’s “Thinker” of a convention for mourning figures in Greek classical art. Yesterday (24 April), a sculptor took issue with this suggestion in a letter to the Times (see below) claiming a likelier source to be present in Michelangelo’s sculpture and paintings.

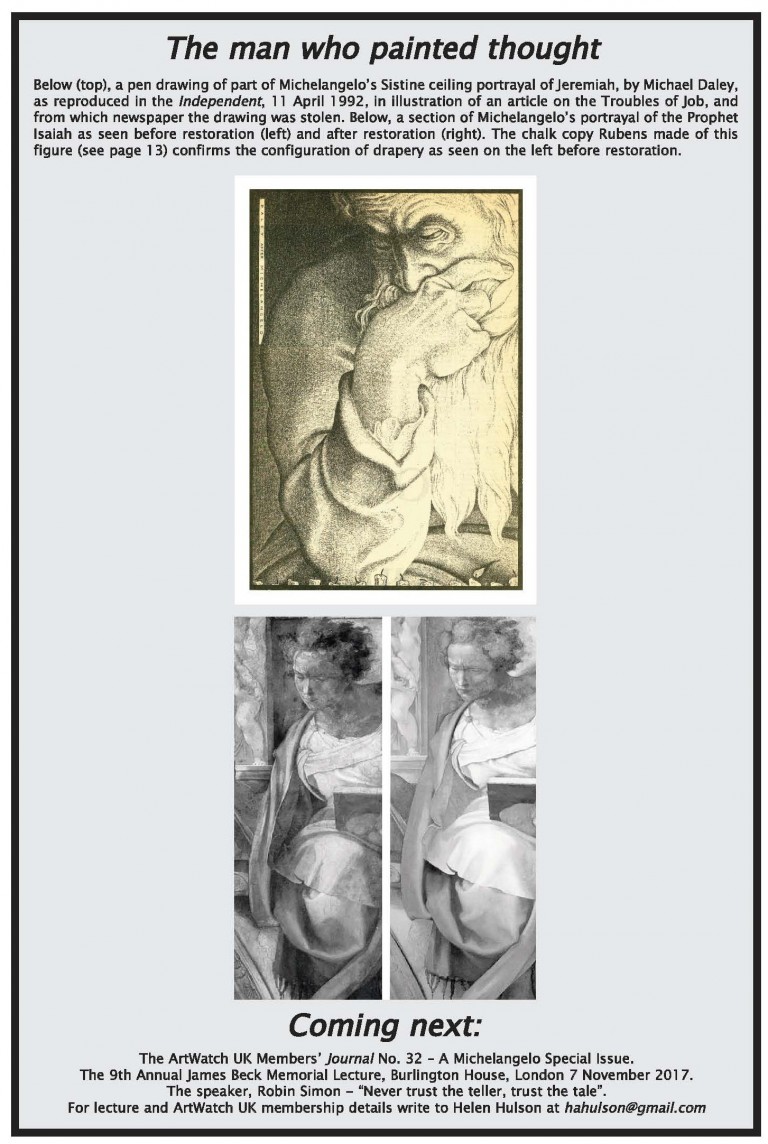

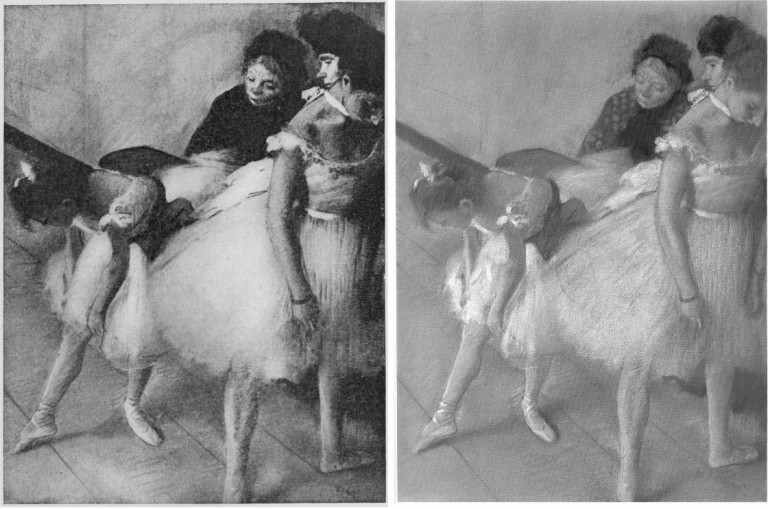

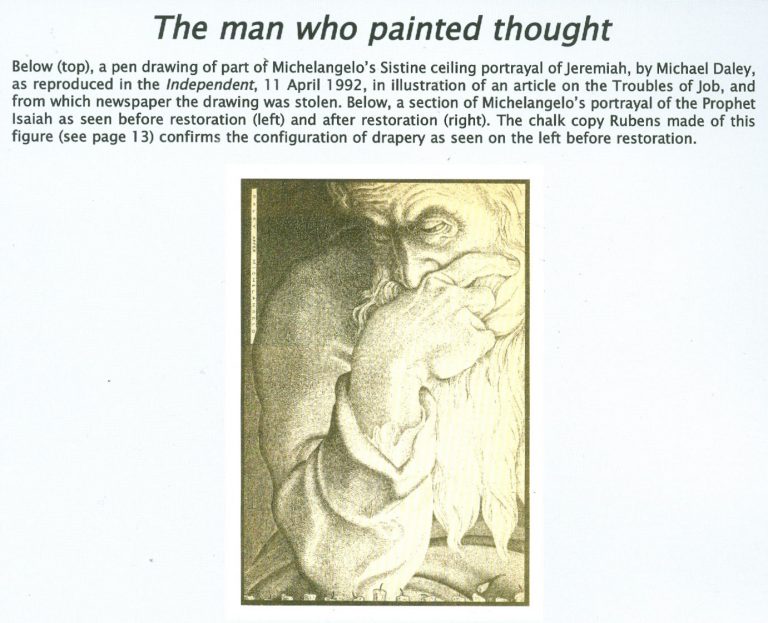

Certainly, Rodin’s awareness of and indebtedness to Michelangelo (who once said that he was never less alone than when alone with his own thoughts) was immense and, as David Breuer-Weil points out, there are strong figural resemblances. Nonetheless, Jenkins’ point was phrased with precision and he had elaborated it with striking eloquence on yesterday’s Radio 4 Today programme – this itself being a most welcome development: we have rather forgotten in recent years that museums are their curators. In the two cited Michelangelos the Lorenzo de’ Medici figure is thoughtful but imperious and unperturbed. His back is straight and his shoulders are held high. A forefinger touches his nose and lips but it has no structural function. In the painted prophet Jeremiah from the Sistine Chapel ceiling, while the figure slumps the lower legs are decorously crossed and bear little weight. It so happens, this is a figure with which we have engaged in the past and it is carried on the back of the current ArtWatch UK members’ Journal:

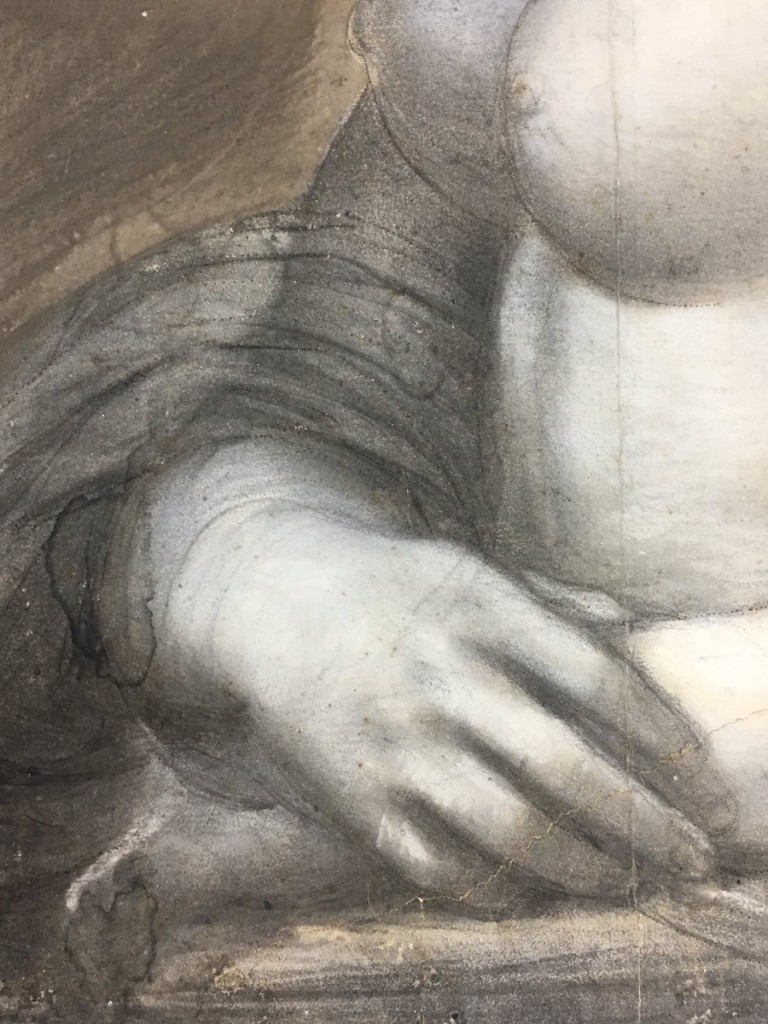

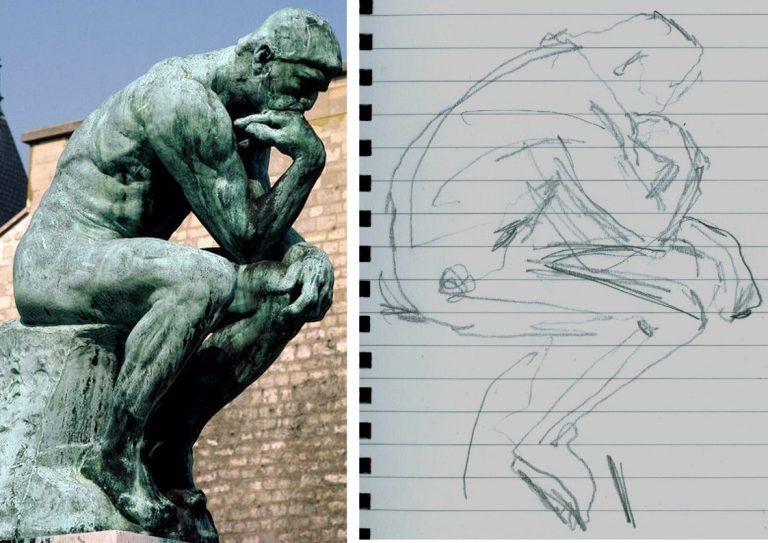

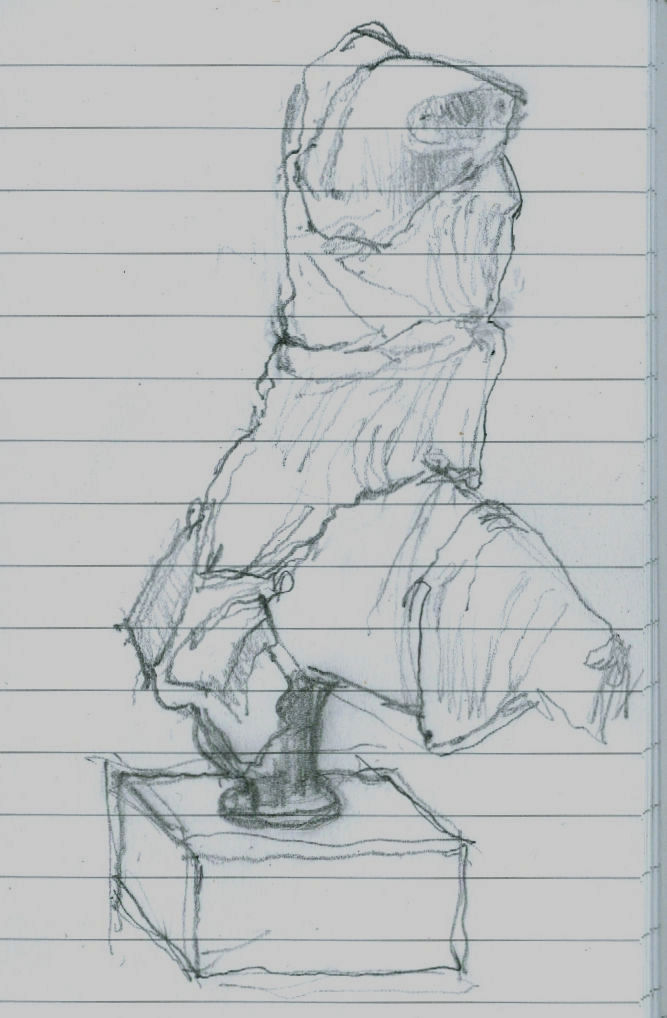

As seen in the Jeremiah detail we had adapted for a newspaper illustration (above), the head rests heavily on the hand which grips the lower face and entirely conceals the mouth – perhaps this near-universal indicator of thought stems from the source of speech being taken out of commission? There is a vital difference between the Thinker and the Jeremiah. In the former, the head rests heavily on the hand but the forearm/hand serves only as a prop or buttress. Indeed, the entire figure is a dynamic portrayal of weight, as we noted in graphic shorthand last night in the diagram below right. Even the legs are involved in buttressing the entire slumping figure who grips the very earth with his toes (photo. by promentary.net.au). Crucially, the hand does not engage directly or expressively with the face other than insofar as the upward buttressing force of the knuckles distorts the upper lip.

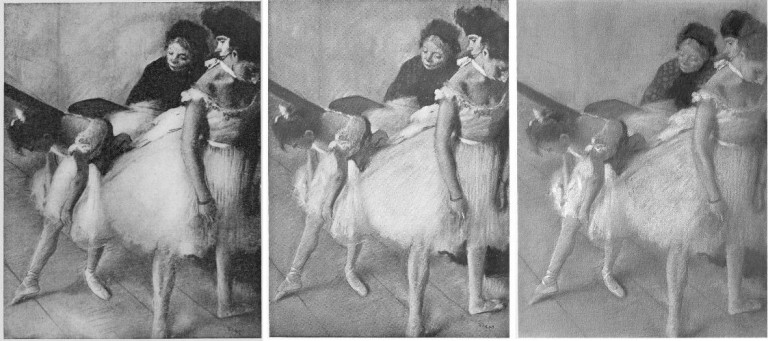

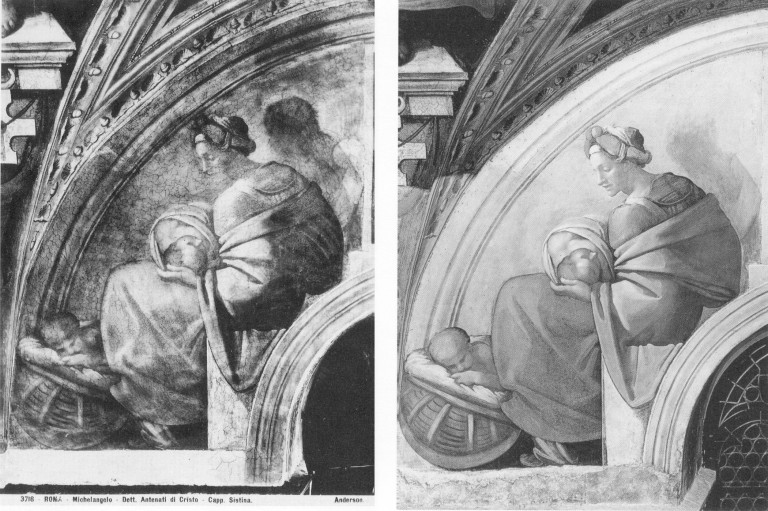

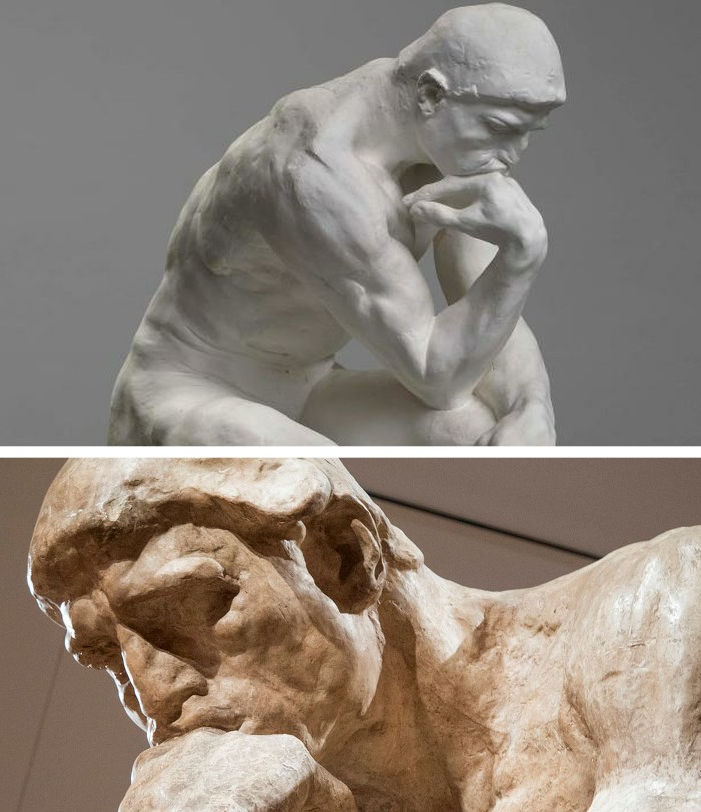

The face itself (above) is not simply thoughtful or absorbed but mournful, desolate. This head is as heavy as the heart within the figure. Jenkins seems vindicated on his observation. For artists and, particularly for sculptors, this show is, more than an invitation, a command to stop, look and draw. The British Museum has sensed as much and will be making drawing materials available to visitors. For our part, we would urge them not to be bashful and to seize the opportunity to draw unselfconsciously and purposively. Drawings are best seen not as a species of self-expression but as straightforward explanations. Draw to explain that which seems interesting significant or distinctive in a particular figure. There are no right answers here, just nice observations worthy of being made. Drawing regularly disciplines thinking and sharpens looking. (Degas once told a woman she had a beautifully drawn head. Draughtsmen know exactly what he meant.) Last night we snatched some drawings of the backs of figures, as below with Iris from the Parthenon whose flowing animalistic energy directly inspired Rodin to make an even more dynamically eroticised bronze.

RODIN’S METHOD ENCAPSULATED

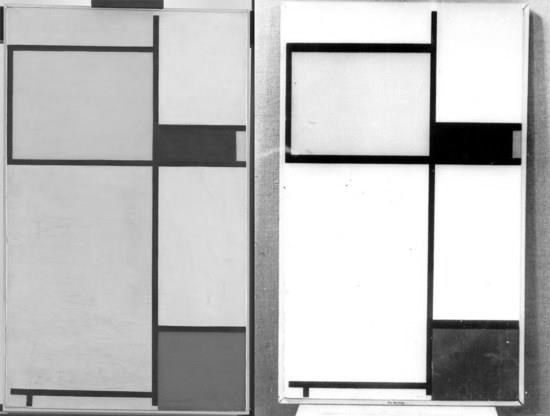

We would especially urge all visitors to take careful note of a little showcase at the far end of the gallery (next to a demonstration of plaster piece/mould casting). In it are two small modelled figures that constitute a summation of Rodin’s sculptural insights. The models were made to explain/demonstrate the differences between classical sculpture and Michelangelo’s figures. We wrote of Rodin’s understanding of differing figural conventions four years ago in the Jackdaw magazine.

The quoted Rodin comments in the article above came from the 1912 English version of Paul Gsell’s Art by Auguste Rodin. We supplement them here with a fuller account from the horse’s mouth:

“One Saturday evening Rodin said to me ‘Come and see me tomorrow morning at Meudon. We will talk of Phidias and of Michael Angelo and I will model statuettes for you on the principles of both. In that way you will quickly grasp the essential differences of the two inspirations, or, to express it better, the opposed characteristics which divide them’…Rolling balls of clay on the table, he began rapidly to model a figure talking at the same time. ‘This first figure will be founded on the conception of Phidias. When I pronounce that name I am really thinking of all Greek sculpture, which found its highest expression in Phidias.’

“The clay figure was taking shape. Rodin’s hands came and went, adding bits of clay; gathering it with in his large palms, with swift accurate movements; then the thumb and the fingers took part, turning a leg with a single pressure, rounding a hip, sloping a shoulder, turning the head, and all with incredible swiftness, almost as if he were performing a conjuring trick. Occasionally the master stopped a moment to consider his work, reflected, decided, and then rapidly executed his idea…Rodin’s statuette grew into life. It was full of rhythm, one hand on the hip, the other arm falling gracefully at her side and the head bent. ‘I am not [f]atuous enough believe that this quick sketch is as beautiful as an antique,’ the master said, laughing, ‘but don’t you find it gives you a dim idea of it? […]Well, then, let us examine and see from what this resemblance arises. My statuette offers, from head to feet, four planes which are alternatively opposed. The plane of the shoulders and chest leads to the left shoulder – the plane of the lower half of the body leads towards the right side – the plane of the knees leads again towards the left knee, for the knee of the right leg, which is bent, comes ahead of the other – and finally, the foot of this same right leg is back of the left foot. So, I repeat, you can note four directions in my figure which produce a very gentle undulation through the whole body.

‘This impression of tranquil charm is equally given by the balance of the figure. A plumb-line through the middle of the neck would fall on the inner ankle bone of the left foot, which bears all the weight of the body. The other leg, on the contrary, is free – only its toes touch the ground and so furnish a supplementary support; it could be lifted without disturbing the equilibrium. The pose is full of abandon and of grace.

‘There is another thing to notice. The upper part of the torso leans to the side of the leg which supports the body. The left shoulder is, thus, at a lower level than the other. But, as opposed to it, the left hip, which supports the whole pose, is raised and salient. So, on this side of the body, the shoulder is nearer the hip, while on the other side the right shoulder, which is raised, is separated from the right hip, which is lowered. This recalls the movement of an accordion which, closes on one side and opens on the other…Now look at my statuette in profile. It is bent backwards; the back is hollowed and the chest is slightly expanded. In a word, the figure is convex and has the form of a letter C. This form helps it to catch the light, which is distributed softly over the torso and the limbs and so adds to the general charm…Now translate this technical system into spiritual terms; you will then recognise that antique art signifies contentment, calm, grace, balance and reason…And now, by the way, an important truth. When the planes of a figure are well placed, with decision and intelligence, all is done, so to speak; the whole effect is obtained; the refinements which come after might please the spectator but they are almost superfluous. This science of the planes is common to all great epochs; it is almost ignored today.’”

And then, Gsell noted, Rodin turned to Michelangelo: “‘Now! Follow my explanation. Here, instead of four planes, you have only two; one for the upper half of the statuette and the other, opposed, for the lower half. This gives at once a sense of violence and constraint – and the result is a striking contrast to the calm of the antiques. Both legs are bent, and consequently the weight of the body is divided between the two instead of being borne exclusively by one. So there is no repose here, but work for both lower limbs…Nor is the torso less animated. Instead of resting quietly, as in the antique, on the most prominent hip, it, on the contrary, raises the shoulder on the same side so as to continue the movement of the hip. Now, note that the concentration of effort places the two limbs one against the other, and the two arms, one against the body and the other against the head. In this way there is no space left between the limbs and the body. You see none of those openings which, resulting from the freedom with which the arms and legs were placed, gave lightness to Greek sculpture. The art of Michelangelo created statues all of a size in a block. He said himself that only those statues were good which could be rolled from the top of a mountain without breaking; and in his opinion all that was broken off in such a fall was superfluous

‘His figures surely seem to be carved to meet this test; but it is certain not a single antique could have stood it; the greatest works of Phidias, of Praxiteles, of Polycletes, of Scopas and of Lysippus would have reached the foot of the hill in pieces. And this proves how a formula which may be profoundly true for one artistic school may be false for another.

‘A last important characteristic of my statuette is that it is in the form of a console; the knees constitute the lower protuberance; the retreating chest represents the concavity, the bent head the upper jutment of the console. The torso is thus arched forward instead of backward as in antique art. It is that which produces here such deep shadows in the hollow chest and beneath the legs. To sum it up, the greatest genius of modern times has celebrated the epic of shadow, while the ancients celebrated that of light. And if we now seek the spiritual significance of the technique of Michael Angelo, as we did that of the Greeks, we shall find that his sculpture expressed restless energy, the will to act without hope of success – in fine, the martyrdom of the creature tormented by unrealisable aspirations…To tell the truth, Michael Angelo does not, as is often contended, hold a unique place in art. He is the culmination of all Gothic thought…He is manifestly the descendant of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. You constantly find in the sculpture of the Middle Ages this form of the console to which I drew your attention. There you find this same restriction of the chest, these limbs glued to the body, and this attitude of effort. There you find above all a melancholy which regards life as a transitory thing to which you must not cling.’”

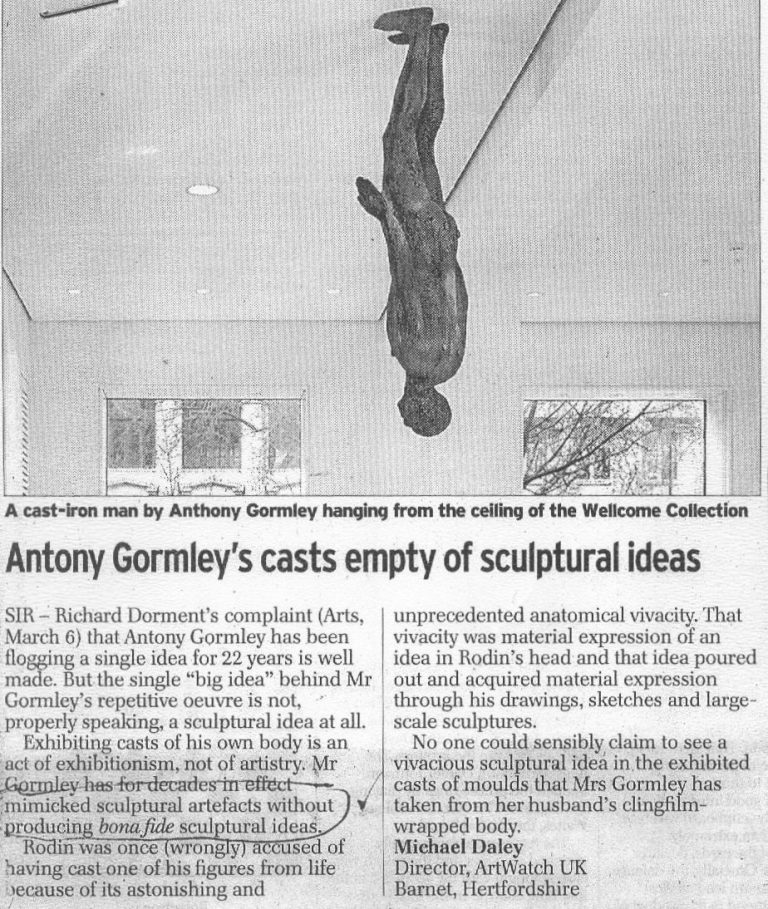

Clearly, Rodin would have no shortage of ideas if invited to deliver the Reith Lectures. We think we understand what political point Gormley wishes to make with his neckwear. The point of his sculptures is less apparent, as we complained in a letter to the Daily Telegraph (12 March 2008):

This Rodin/Phidias show has not been cost-free in terms of disruption and the further cleaning of the Parthenon sculptures but, leaving such aside, it is the most sculpturally engaging and instructive we have seen since the great 1972 Royal Academy and Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition “The Age of Neo-Classicism”.

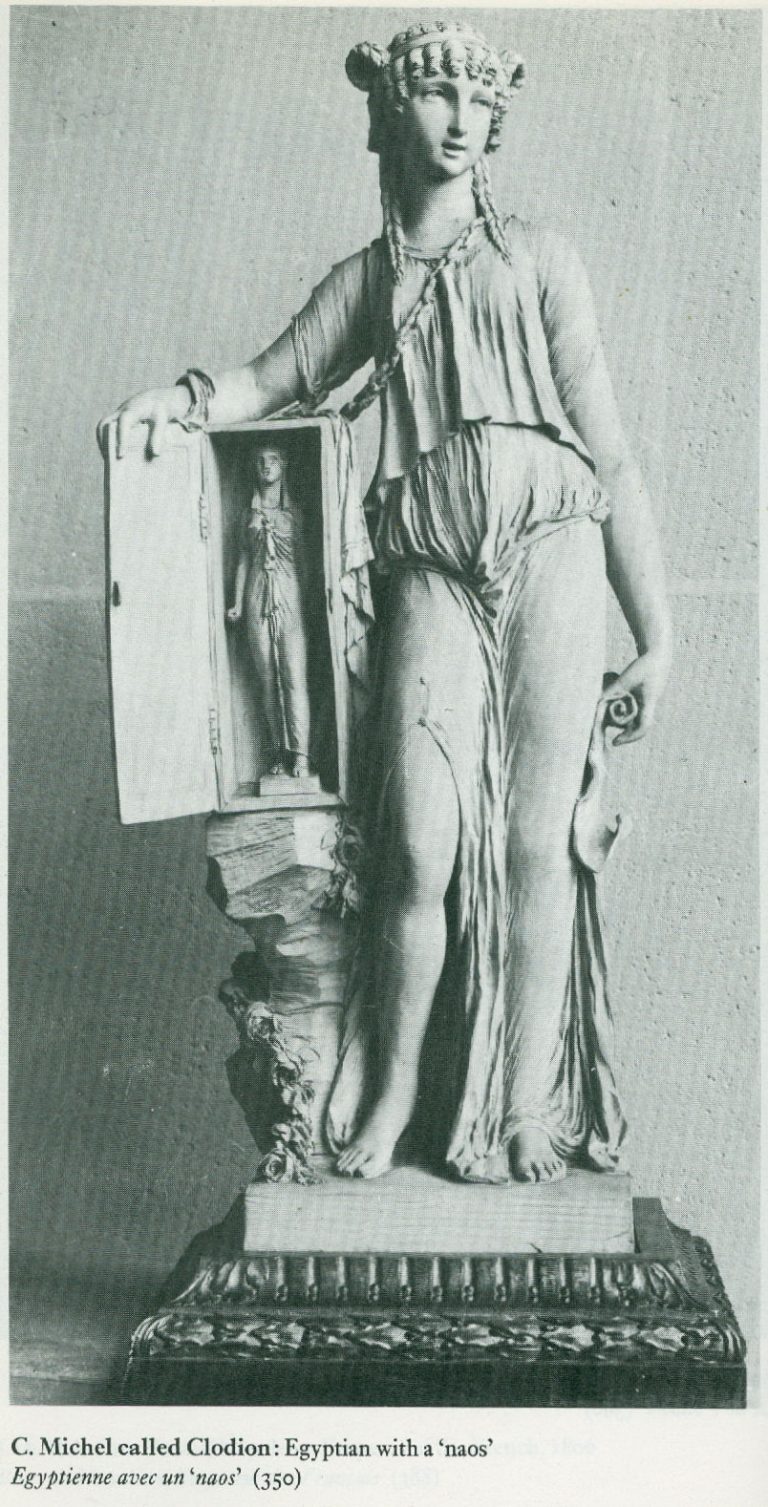

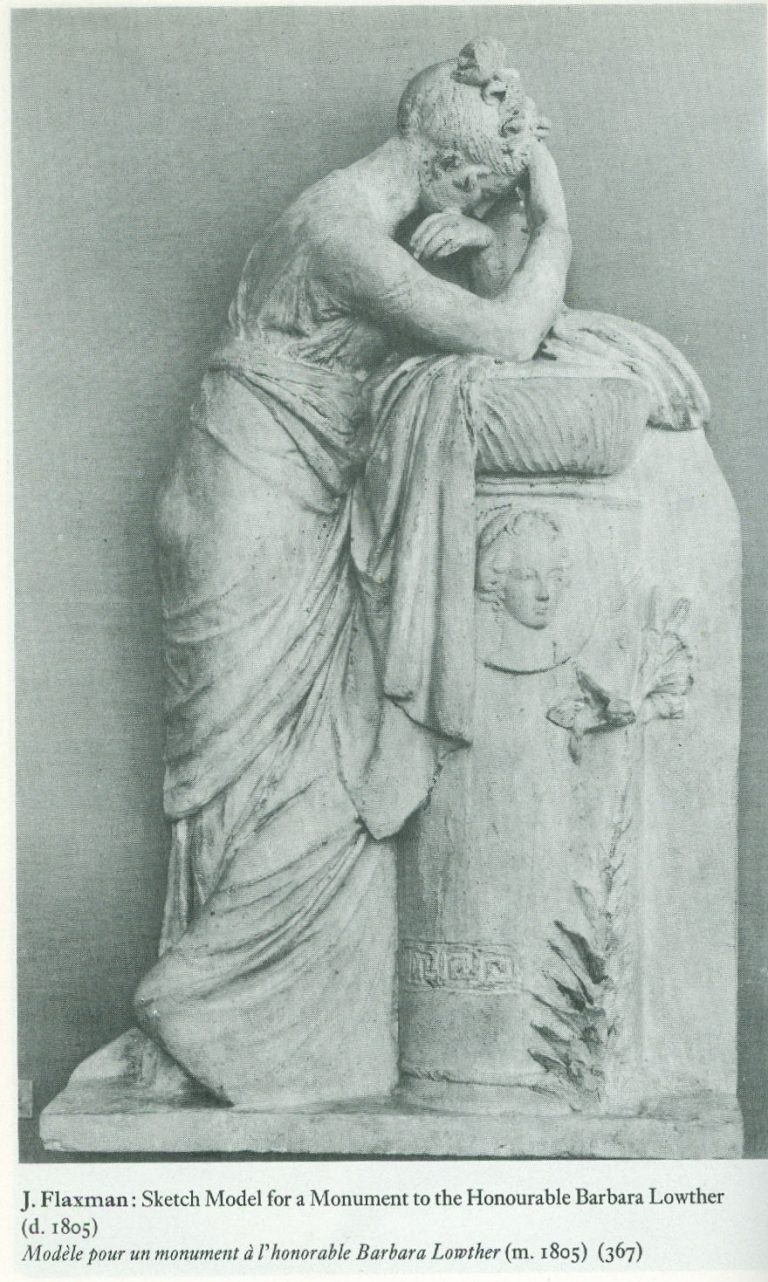

ArtWatch has no politics and, as mentioned, this is an entirely personal response to an exhibition but, nonetheless, we would respectfully point out to the French Ambassador that that earlier wonderful internationally cooperative Neo-classicism show – the fourteenth exhibition of the Council of Europe – was mounted two years before Britain voted to join what was presented to its electorate as a common market in goods. Culturally-speaking we were all Europeans then and we will remain so after Britain has exited the grand project (some believe great folly) that is the European Union. In or out of that organisation, Britain and France will continue to play roles in pan-European culture, just as did the two sculptors below, one being French, one British, whose work was included in the 1972 exhibition. The Briton, Flaxman, had earlier echoed the ancient convention of mourning that Ian Jenkins has so well spotted in Rodin. Art is a universal and welcoming, all-inclusive language. We should keep politics out of it at all costs.

Michael Daley, 25 April 2018

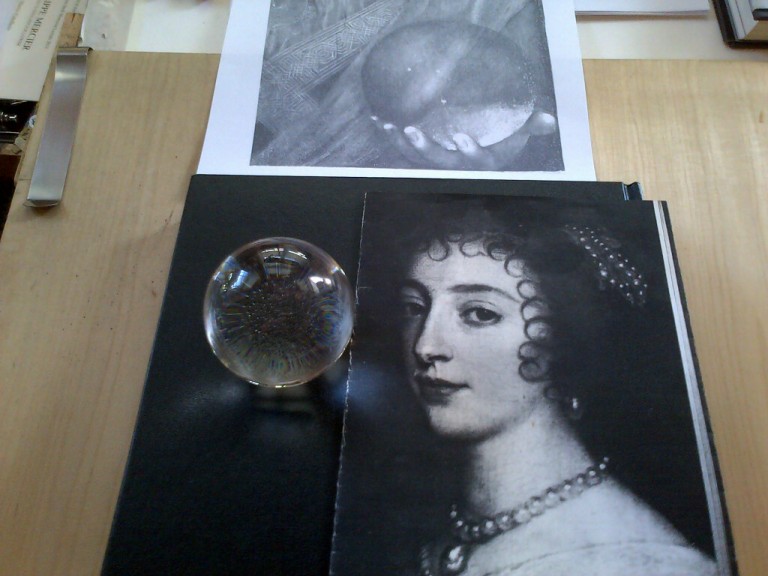

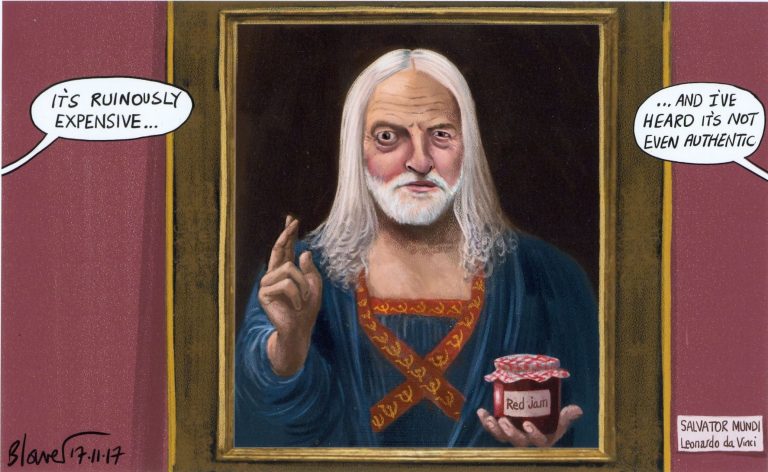

The Leonardo Salvator Mundi Saga: Three Developments

“The more I read it, the more it looks probable.”

Above, Salvator Mundi, the painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and sold at auction in 2017 for $450 million. Photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images – as published on 2 April 2018 in Buffalo News

The sensational Mail Online story (“EXCLUSIVE: The world’s most expensive painting cost $450 MILLION because two Arab princes bid against each other by mistake and wouldn’t back down (but settled by swapping it for a yacht”) discussed here in this News & Notices post, has been questioned or disparaged by a number of commentators but not directly challenged by Christie’s, so far as we know. On March 30 Bendor Grosvenor wrote (“Who underbid the Salvator Mundi?):

“I’m sceptical about this version of events. First, the source seems determined to prove mainly that the picture is somehow ‘not worth’ what it made – the figure of $80m is mentioned – when there were other underbidders up to the $200m level. Second, I’ve been told that the underbidder to $400m was not from the Middle East, from a source who would know.”

Had Grosvenor’s source been correct and the Mail’s story, thus, been seriously misleading, one would expect Christie’s’ lawyers to have demanded either changes to the online article or its removal. Grosvenor’s seeming partisanship on the Salvator Mundi case takes two forms. As well as knocking the knockers, he hypes his brother-auctioneers’ hype, as, on November 12 2017 (“Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ to be sold at Christie’s”):

“I love this video of people seeing Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi. Christie’s say 20,000 have been to see the painting on its world tour. I’ve been impressed by how Christie’s have marketed the picture – in fact, I’d say that they’ve taken marketing Old Masters to a whole new level. A well deserved AHN pat on the back to all involved. The sale is on Wednesday 15th November. Anyone care to make a prediction?”

On November 16, the day after the $450m sale, Grosvenor was ecstatically supportive (“’Salvator Mundi’ – the most expensive artwork ever sold at auction”):

“Christie’s just did something that re-writes the history of auctioneering. They took a big gamble with their brand, their strategy to sell the picture, and not to mention the reputations of their leadership team, and they pulled it off. They marketed the picture brilliantly – the best piece of art marketing I’ve ever seen. Above all, they had absolute faith in the picture. AHN congratulates them all.”

Pace Grosvenor and his sources, questions on Christie’s marketing of the Salvator Mundi persist. The whispering campaign against the Mail’s disclosures has not worked. In this weekend’s Financial Times the author Melanie Gerlis closed her art market column with the item below:

As things stand, no one has disproved the Mail’s suggestion that the (disputed) Leonardo Salvator Mundi has been swapped for a luxury yacht. In her book Art as Investment, Gerlis noted that because the “worth and price are known to only a few” in an art market that is underpinned by a lack of “verifiable and meaningful data”, those looking to art purely as a secure investment “might first consider looking elsewhere.”

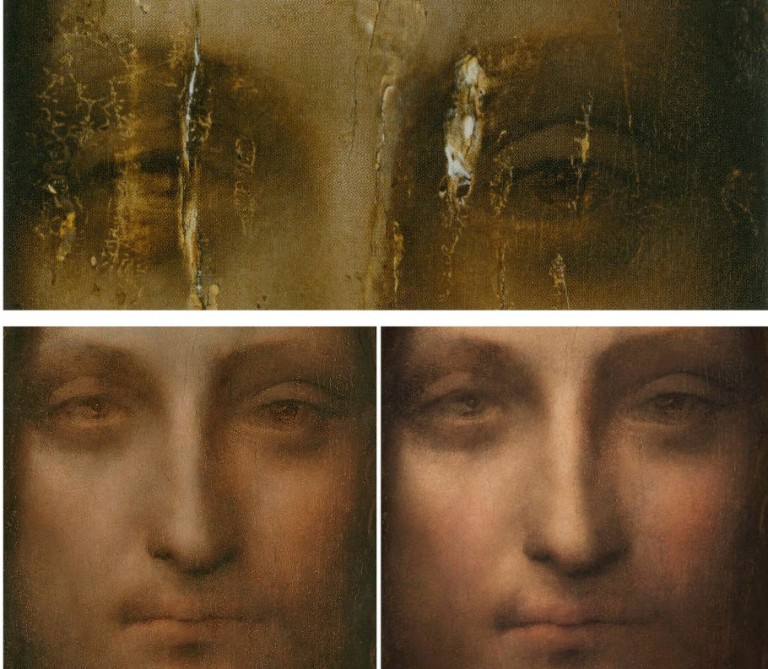

With the Salvator Mundi, some 13 years after its emergence, we still do not know when, where and by whom the painting was bought. There have been many conflicting accounts on the work’s ownership (see below). In the April 6 Antiques and Arts Weekly, the New York dealer Dr Robert Simon was asked: “Can you say where you found Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’?” He replied:

“Alex and I acquired the painting at an estate auction in the United States, but we’ve never divulged the location of the auction. We were not permitted to, according to the terms of the confidentiality agreement we signed at the time we sold the painting.”

The sale was conducted privately in 2013 through Sotheby’s when it was acquired by the “Freeport King”, Yves Bouvier, who was acting as an agent for the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev. Did Sotheby’s insist that the origin of the picture not be disclosed? Or Bouvier? Whomever – the enforced confidentiality clause was made eight years after the claimed discovery/acquisition in 2005. However constricting the terms of the 2013 sale agreement might have been, they could hardly account for the non-disclosure of the owners’ identities for the previous eight years – including the time the picture spent in the National Gallery. When the Salvator Mundi was about to enter the Gallery’s big Leonardo show in 2011 as an autograph Leonardo, the Sunday Times reported:

“Its ownership is a closely guarded secret. Robert Simon, a New York art dealer, is representing the owner, or owners – the official line is it is a ‘consortium’.”

Why, then, did the National Gallery agree to participate in this secrecy on the ownership of a painting whose (contested) Leonardo ascription had been supported by the gallery’s own director; by one of its curators; and, by one of its trustees?

Another of the scholar-supporters of this upgraded Leonardo is Professor Martin Kemp. In 2011 Kemp told the Sunday Times how he had been invited to view the work by the National Gallery (“there’s something it’s worth you coming in to look at”, was how Kemp put it). Kemp described entering the National Gallery’s conservation studios and joining “a little group of people, including some Leonardo scholars from Italy and America, and Robert Simon.” Robert Simon had been accompanied on that trip by the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini. In 2012 Modestini would deliver a paper on the picture’s (then) two restoration campaigns at a conference held in the National Gallery.

FRESH CLAIMS

On April 6 Buffalo News reported that Dianne Modestini was to speak on April 9 in the Burchfield Penney Art Center at SUNY Buffalo State and was about to make two new claims.

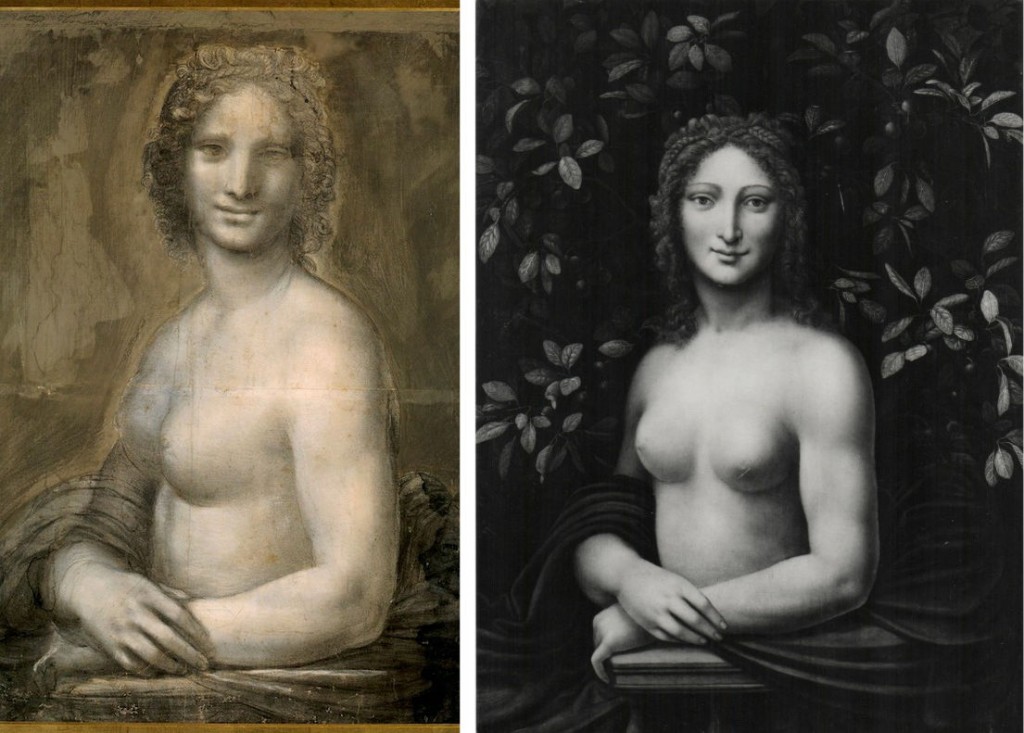

First, that she and her late husband, the restorer Mario Modestini, had entertained no doubts that this was an autograph Leonardo painting: “We were completely convinced and we felt that we could justify this to anyone without sounding like idiots.” This goes further than Modestini’s 2012 paper: “…when I first saw it I never imagined what would transpire with this lovely but damaged painting on panel…I wasn’t aware of a lost, much-copied Salvator Mundi by Leonardo and I was perplexed. I showed the painting to my then 98 year old husband, Mario…He looked at it for a long time and said, ‘It is by a very great artist, a generation after Leonardo’.”

Second, that no technical evidence had emerged to confirm authorship by Leonardo. Modestini reportedly said that what made her so sure was not “the discovery of any single clue attributable to the master’s style or any technical element of the painting that could be traced to his hand, but rather the quality of the painting”. There was “no under-drawing for example, that was Leonardo’s drawing style, or anything like that. The pigments are the pigments that any one of his contemporaries could have used, and did.” This attribution was entirely a matter of judgment: “the quality of the painting, the sort of old-fashioned connoisseurship and skills, which art historians have always used to make an attribution, were in the end the telling factor for us.”

Those present at her lecture might have learnt why a painting that had so soon revealed itself as an autograph Leonardo to two experienced restorers and in which “apart from the discrete losses, the flesh tones of the face retain their entire structure, including the final scumbles and glazes” had needed a third campaign of restoration with substantial repainting of the face, some time between 2016 (when the Qataris reportedly turned down a private offer of the painting for $80m) and the spectacular $450m sale at Christie’s on 15 November 2017 amidst modern works, not old masters.

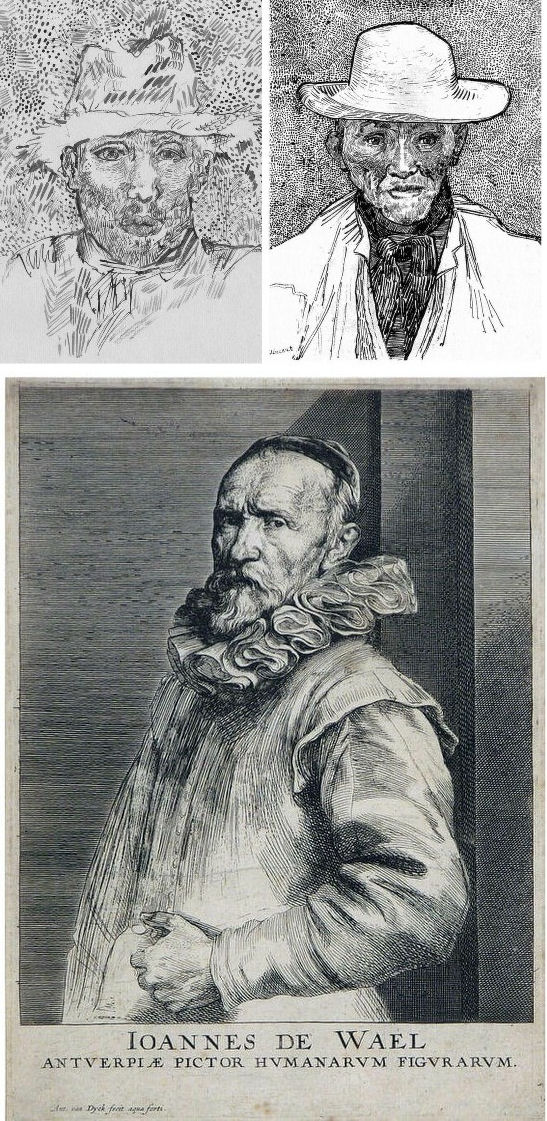

A NEW BOOK – FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

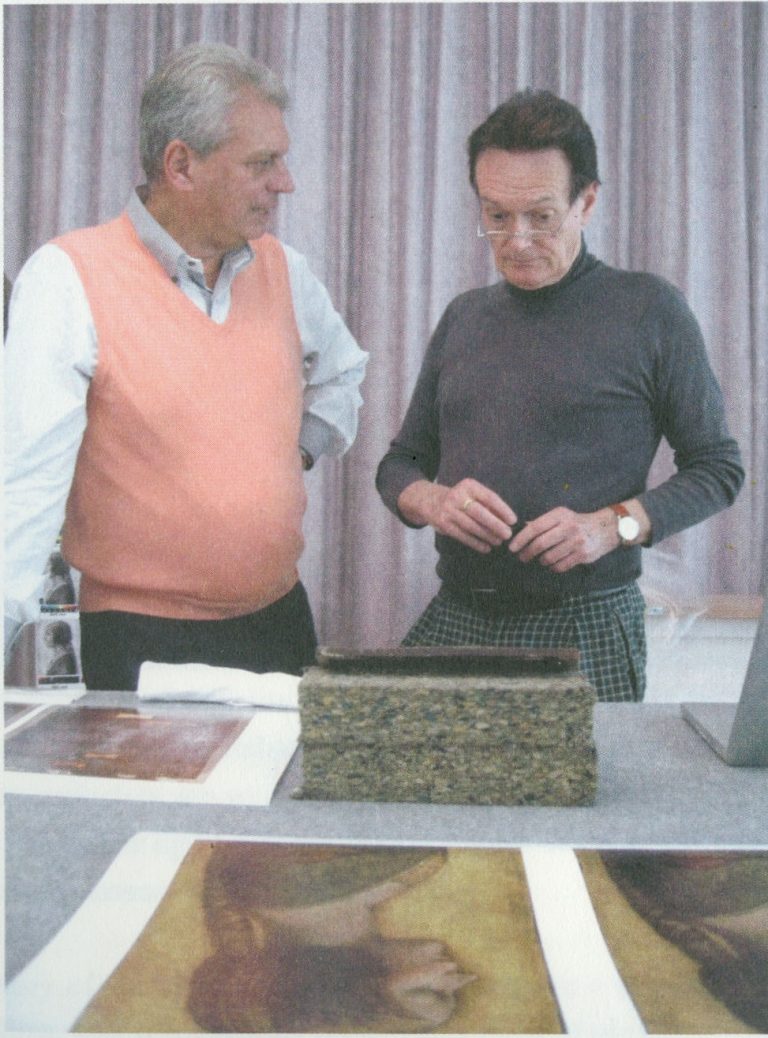

Above: left, Peter Silverman, the owner of the drawing “La Bella Principessa”; right, Professor Martin Kemp, author of the 2010 book “La Bella Principessa” – The Story of the New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci. Photo: as published in Martin Kemp’s Living With Leonardo

Professor Martin Kemp has published a new book (Living with Leonardo – Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond) in which he pays a back-handed compliment to ArtWatch in his second chapter: “Theirs has been the most sustained and fully researched of the hostile polemics”. Elsewhere he launches a series of slurs against three named ArtWatch UK contributors and officers in defence of his own support for two recently attributed Leonardos, the Salvator Mundi painting, and the mixed media drawing on vellum glued onto oak, that he dubbed “La Bella Principessa”. The slurs will be refuted, but we note here that Kemp has now provided a fuller, and apparently verbatim, account of the National Gallery’s invitation to him to view the Salvator Mundi:

“On 5 March 2008, my birthday, an email arrived, announcing the appearance of a new Leonardo – a painting rather than a drawing […It] came from a well known source: Nicholas Penny, then director of the National Gallery in London.

“I would like to invite you to examine a damaged old painting of Christ as Salvator Mundi which is in private hands in New York. Now it has been cleaned, Luke Syson and I, together with our colleagues in both paintings and drawings in the Met, are convinced that it is Leonardo’s original version, although some of us consider that there may be [parts? – Kemp’s parenthesis] which are by the workshop. We hope to have the painting in the National Gallery sometime later in March or in April so that it can be examined next to our version of the Virgin of the Rocks. The best preserved passages in the Salvator Mundi panel are very similar to parts of the latter painting. Would you be free to come to London at any time in this period? We are only inviting two or three scholars.”

The following observations on that stage of the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo accreditation might be made:

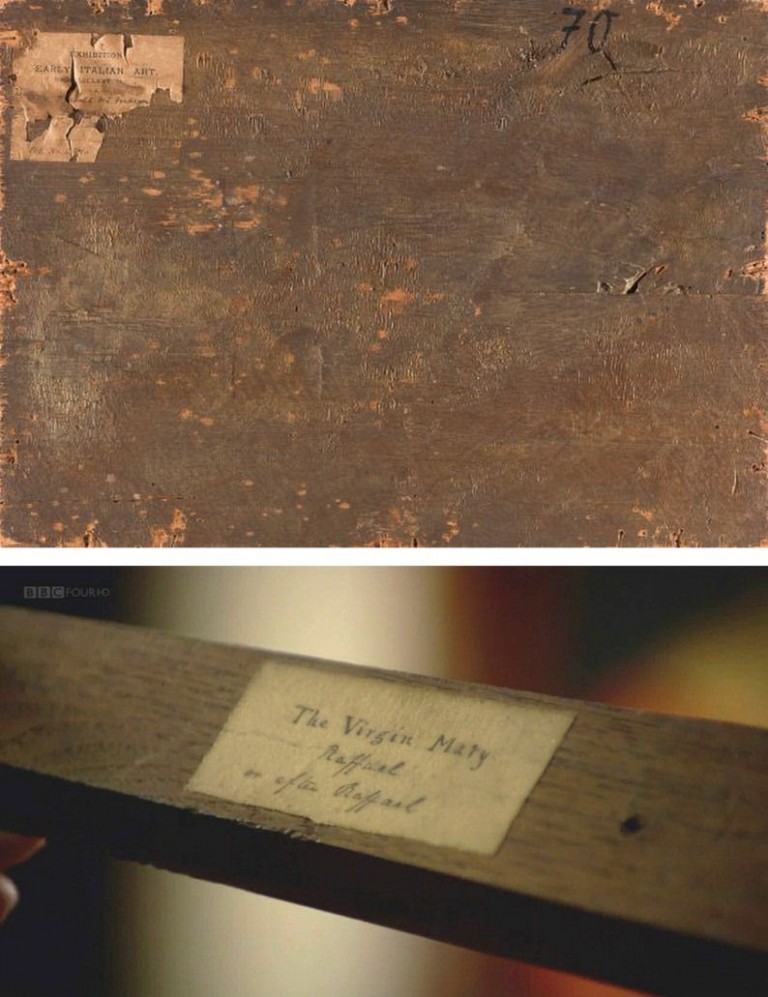

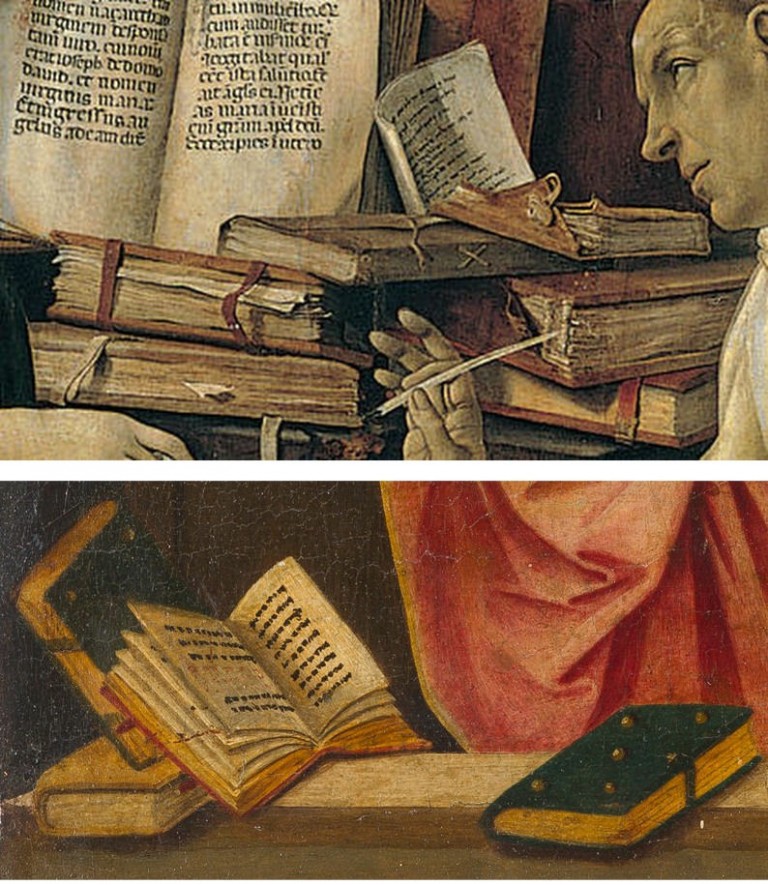

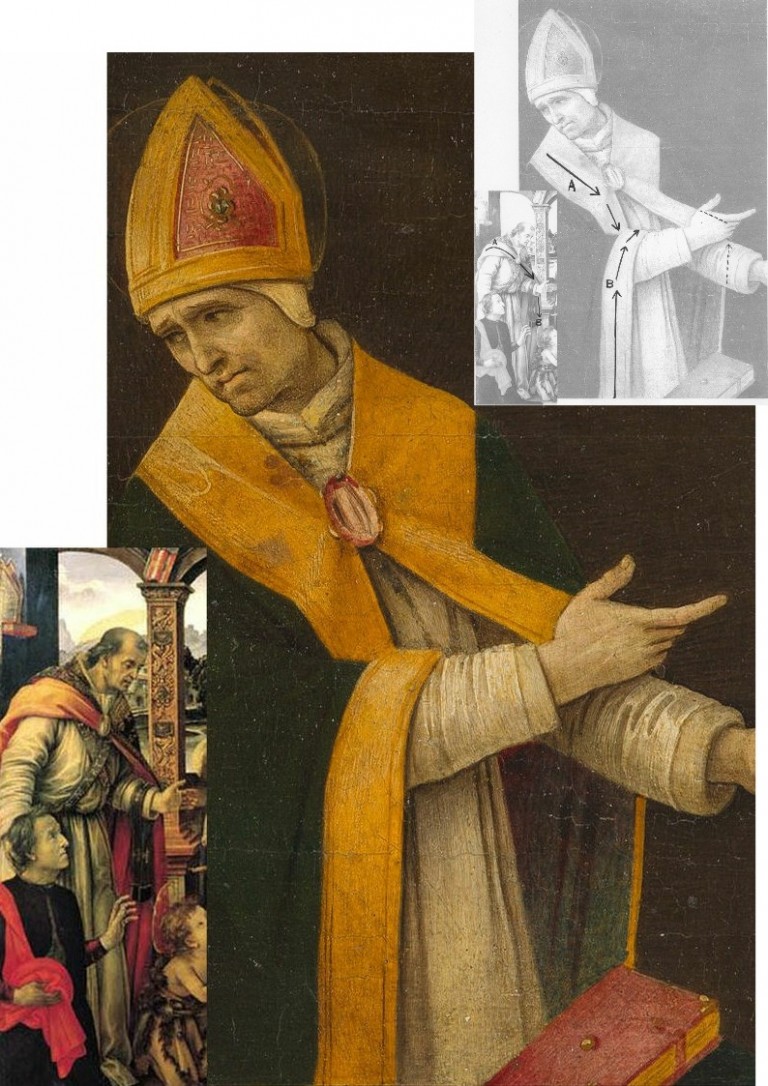

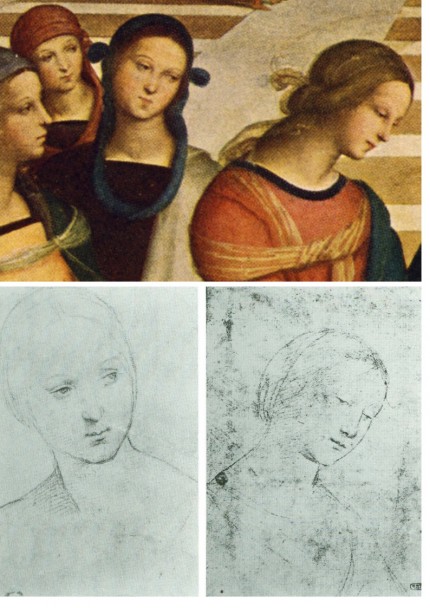

1) The method of inviting successive select groups of scholars to see and appraise the painting in the prior knowledge of others’ support for the new attribution might be thought to have fallen short of the National Gallery’s own practices. When Nicholas Penny, as a curator at the National Gallery, proposed the Northumberland version of Raphael’s Madonna of the Pinks as the original painted prototype of the very many versions, he first published a thorough and well-received scholarly article in the Burlington Magazine, and later invited a group of some thirty Raphael scholars to discuss the matter during a day-long symposium at the National Gallery.

2) With this Salvator Mundi upgrade, none of the fifteen or so invited experts has published a case for the attribution. Robert Simon has yet to publish the researches to which both Modestini’s restoration report and Luke Syson’s exhibition catalogue entry were indebted. It is not clear whether Modestini was present when the painting was examined at the National Gallery. Kemp writes in his new book:

“No one in this assembly was openly expressing doubt that Leonardo was responsible for the painting, although the possibility of participation by an assistant or two was generally acknowledged. I sensed that Carmen [Bambach, of the Metropolitan Museum drawings] was the most reserved about the painting’s overall quality. A general discussion followed. Robert Simon, the custodian of the picture (whom I later learnt was its co-owner), outlined something of its history and its restoration. He seemed sincere, straightforward and judiciously restrained, as proved to be the case in all our subsequent contacts…”

Carmen Bambach rejected the Leonardo attribution in a 2012 Apollo review of the National Gallery exhibition and gave the painting to Leonardo’s student Boltraffio. Ironically, the Times reported on 9 April 2017 that Kemp has now demoted the Hermitage Museum’s Litta Madonna (which was included as a Leonardo in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition) from Leonardo to Boltraffio.

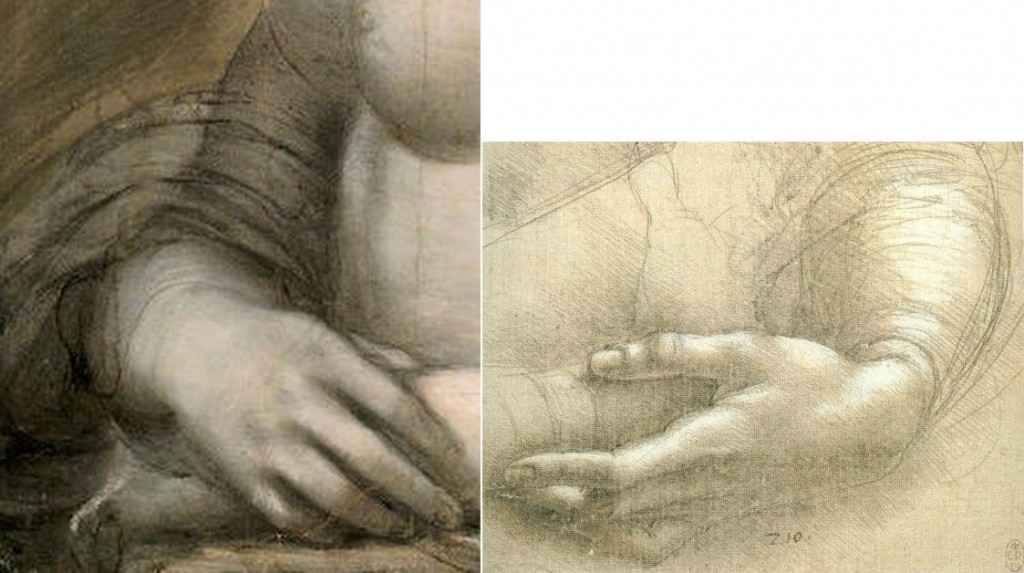

3) After seeing the Salvator Mundi next to the National Gallery’s version of Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks (which is to say, its second version), Dianne Modestini was inspired to change the appearance of the former:

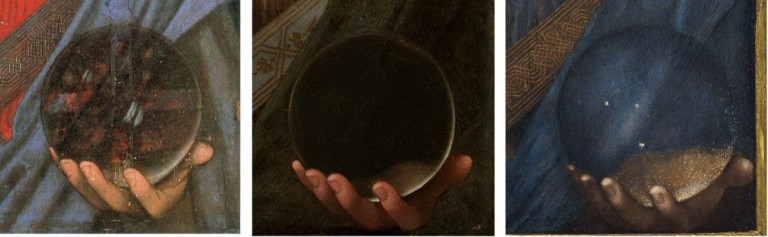

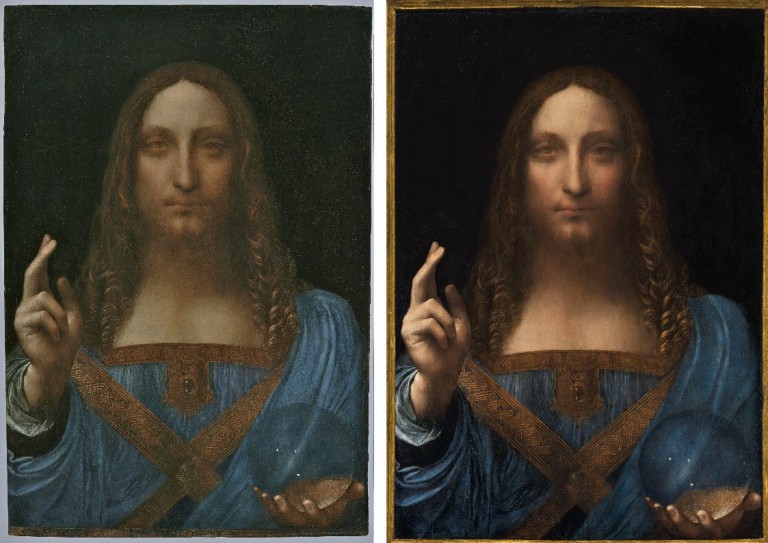

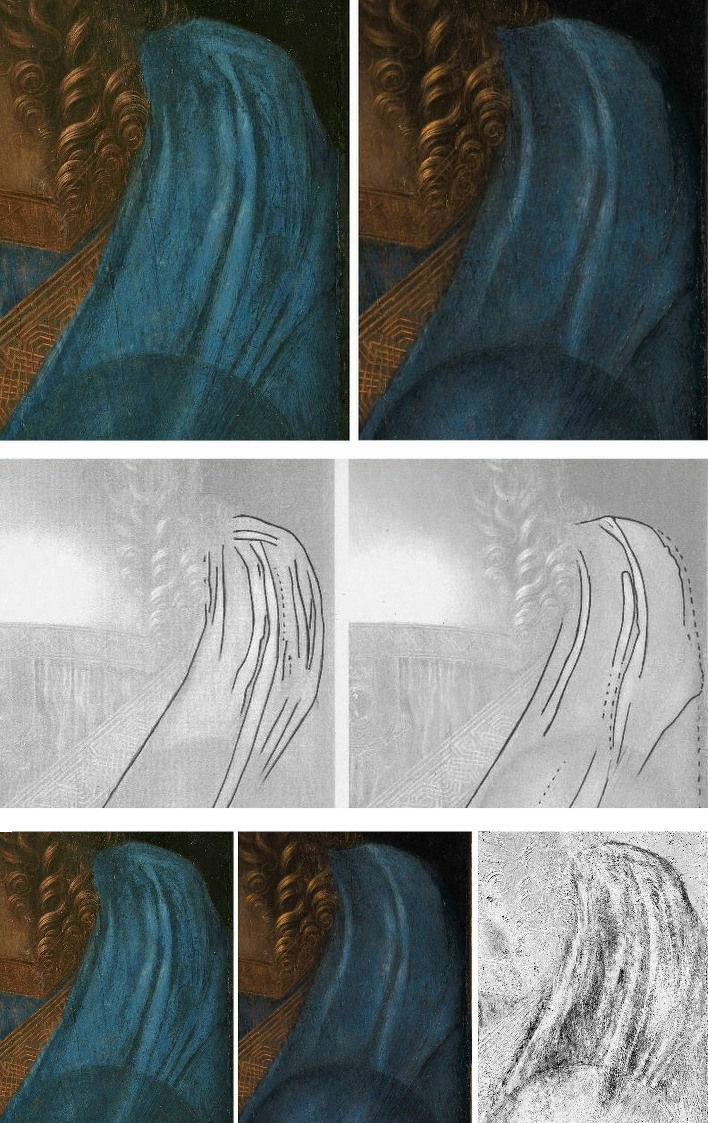

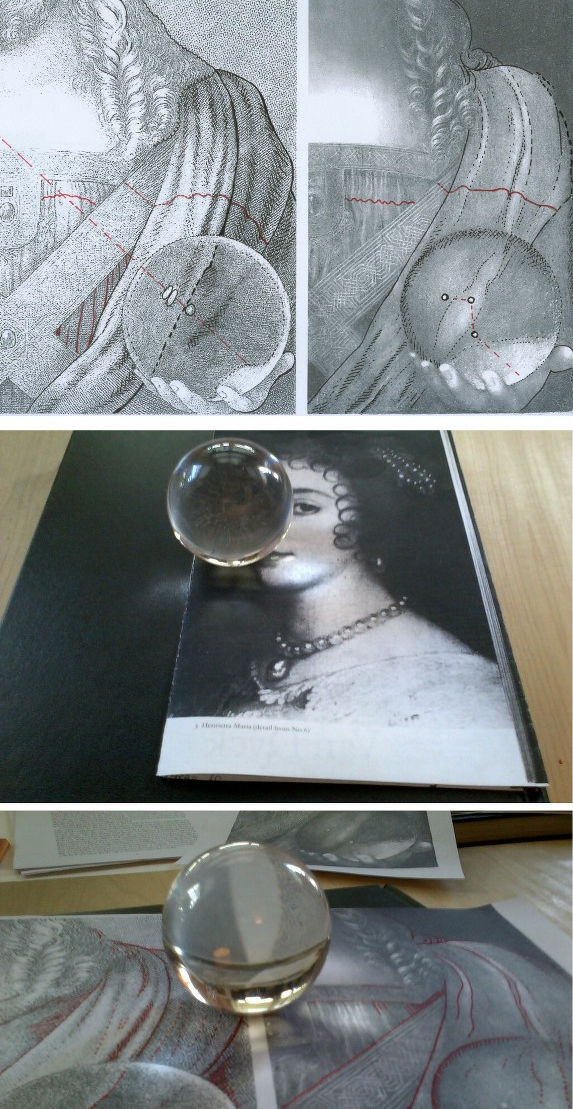

“There were actually two stages of the current restoration. In 2008 when it went to London to be studied by several Leonardo experts, there was less retouching. I hadn’t replaced the glazes on the orb, finished the eyes, suppressed the pentimenti on the thumb and stole, and several other small details but, chiefly, the painting still had the mud-coloured modern background that was close in tone to the hair. Two years later I was troubled by the way the background encroached upon the head, trapping it in the same plane as the background. Having seen the richness of the well-preserved browns and blacks in the London Virgin of the Rocks and based on fragments of the black background which had not been covered up by the repainting, I suggested to the owners that it might be worthwhile to try to recover the original background and finish the complete restoration.”

Thus, Modestini had intervened radically on the painting shortly before it was included in the National Gallery’s major 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition and two years after it was appraised by selected Leonardo scholars at the National Gallery.

4) Restoration campaigns, like wars, are easy to start. In 2012 Modestini acknowledged an ambition to finish a “complete restoration”, after seeing the National Gallery’s restored Virgin of the Rocks. Permission, she recalled, was granted to strip and repaint the entire background:

“The initial cleaning [i. e. paint and varnish removal] was promising especially where the verdigris had preserved the original layers. Unfortunately, in the upper parts of the background, the paint had been scraped down to the ground and in some cases the wood itself. Whether or not I would have begun had I known, is a moot point. Since the putty and overpaint were quite thick I had no choice but to remove them completely. I repainted the large missing areas in the upper part of the painting with ivory black and a little cadmium light red, followed by a glaze of rich warm brown, then more black and vermilion. Between stages I distressed and then retouched the new paint to make it look antique. The new colour then freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair, and made a different, altogether more powerful image.”

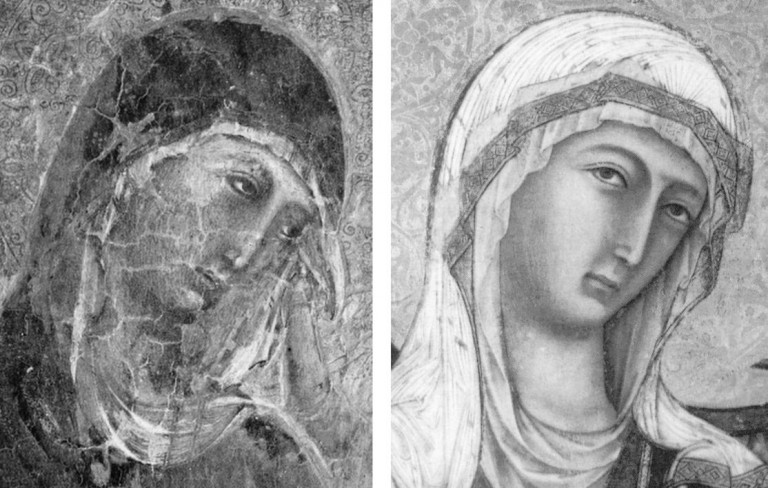

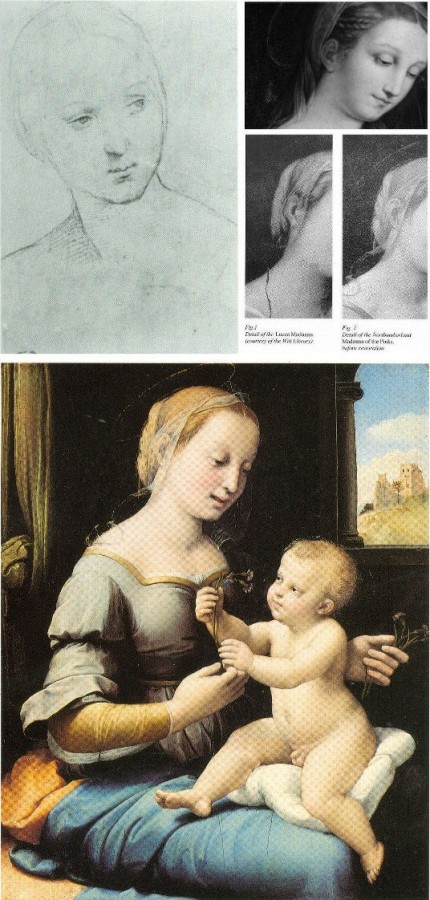

5) “Restorations”, which might more accurately be described as “stripped and painted re-presentations commissioned by owners”, are rarely straightforward and unproblematic. Modestini made her decisions in the sincere belief that the London Virgin of the Rocks is an entirely autograph Leonardo painting and therefore a reliable guide to her own interventions on the Salvator Mundi. However, that Leonardo attribution has only been widely thought to be the case since the painting’s recent restoration. Kenneth Clark, when director of the National Gallery thought otherwise. In 1944 he said of the head of the picture’s angel: “This is one part of our Virgin of the Rocks where the evidence of Leonardo’s hand seems undeniable, not only in the full, simple modelling, but in the drawing of the hair. The curls around the shoulder have exactly the same movement as Leonardo’s drawings of swirling water. Beautiful as it is, this angel lacks the enchantment of the lighter, more Gothic angel in the Paris version…” Of the head of the Virgin, Clark wrote:

“…It is uncertain how much of this replica [of the first, Louvre, Virgin of the Rocks] he [Leonardo] executed with his own hand, and this head of the Virgin is the most difficult part of the problem. It is too heavy and lifeless for Leonardo and the actual type is un-Leonardesque; yet it is painted in exactly the same technique as the angel’s head in the same picture; and that is so perfect that Leonardo must surely have had a hand in it. Both show curious marks of palm and thumb…made when the paint was wet, and no doubt covered by glazes long since removed. This perhaps is a clue to the problem. A pupil did the main work of drawing and modelling, and before the paint was dry Leonardo put in the finishing touches. Most of these have been removed from the Virgin’s face but remain in the angel’s, where perhaps they were always more numerous.”

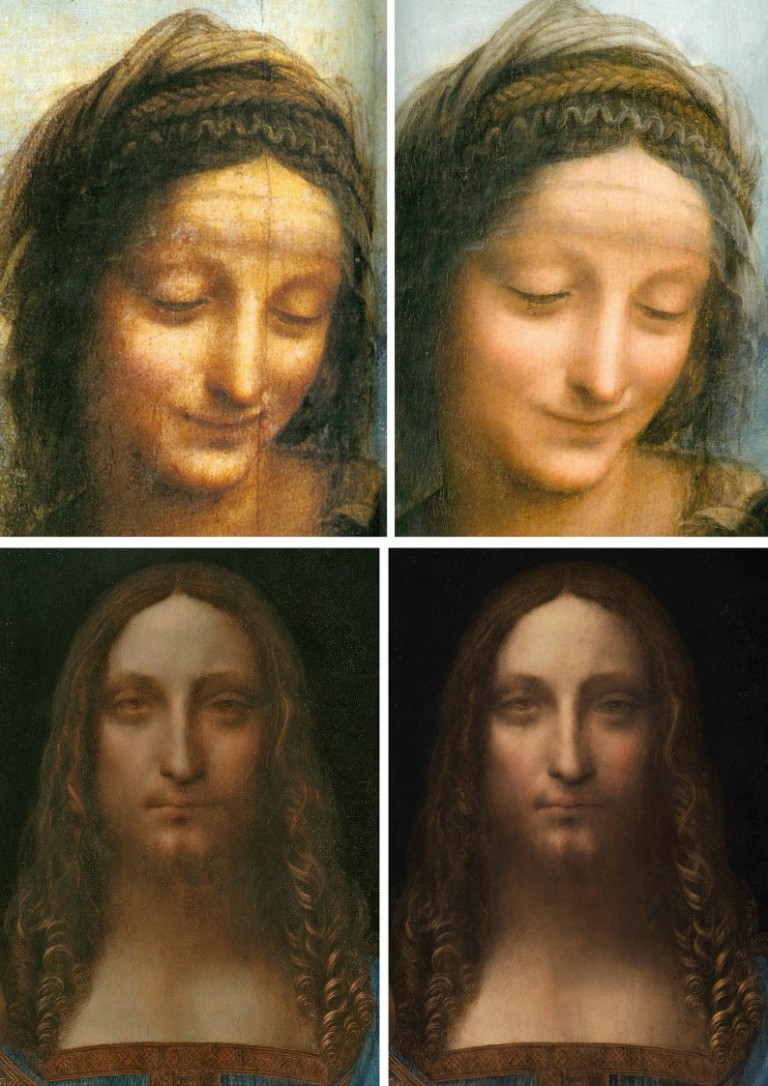

Above, top: The head of the Virgin in the National Gallery’s (second) version of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin of the Rocks, as published in 1944 in Kenneth Clark’s One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery. Above, the Head of the Virgin as published in the 1990 re-issue of Clark’s “Details” book and, therefore, after its post-war restoration by Helmut Ruhemann but before its more recent re-restoration by Larry Keith (in which the mouth of the Angel was altered, on Luke Syson’s advice, as discussed here in “Something Not Quite Right About Leonardo’s Mouth ~ The Rise and Rise of Cosmetically Altered Art”).

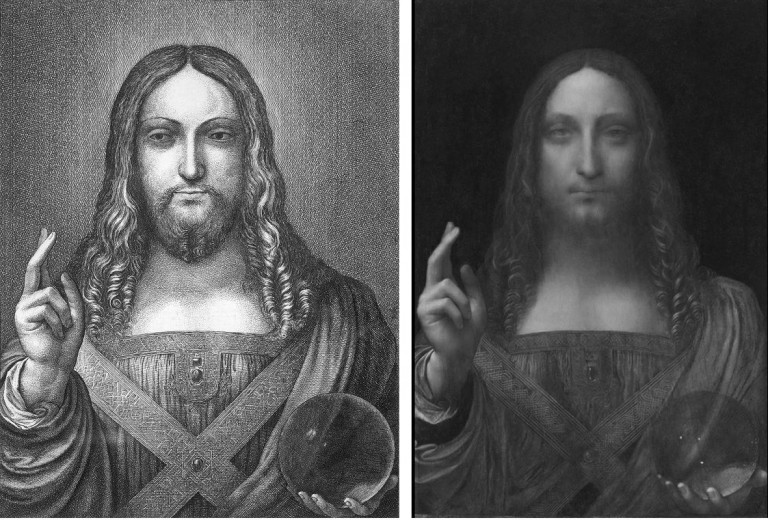

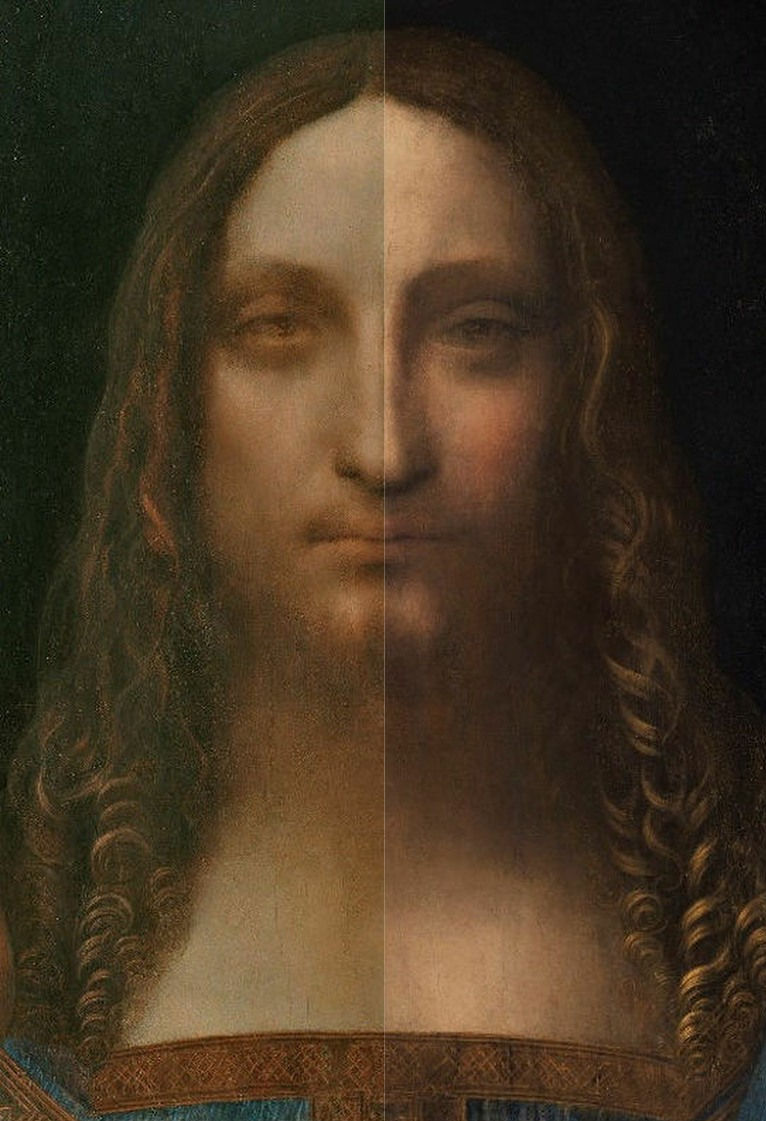

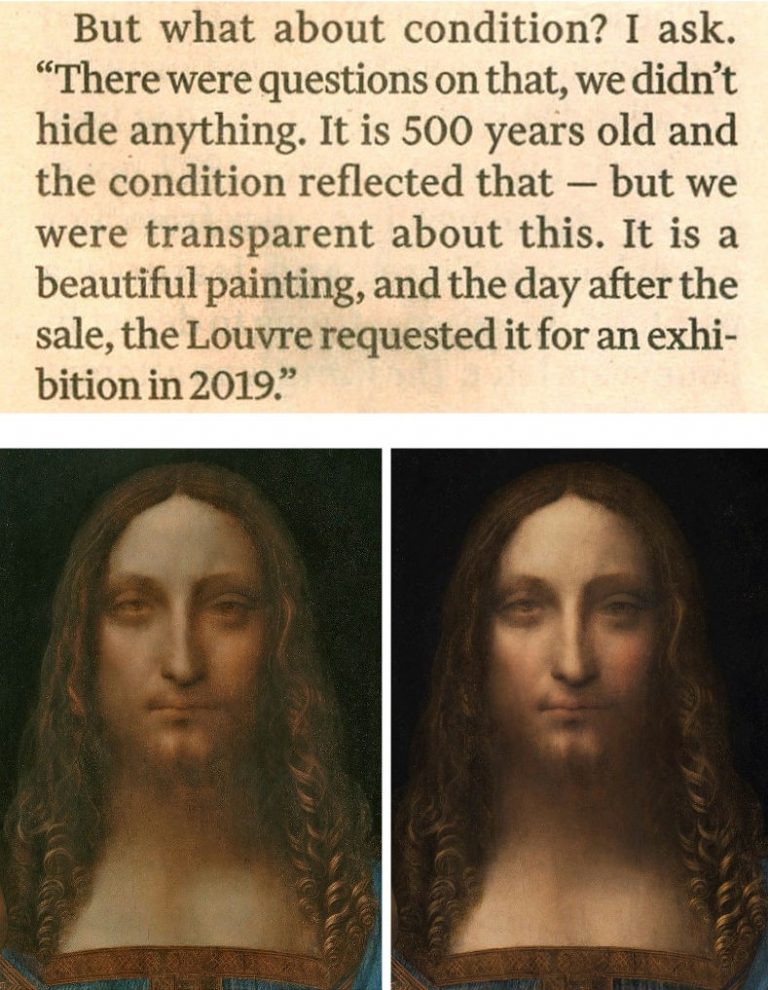

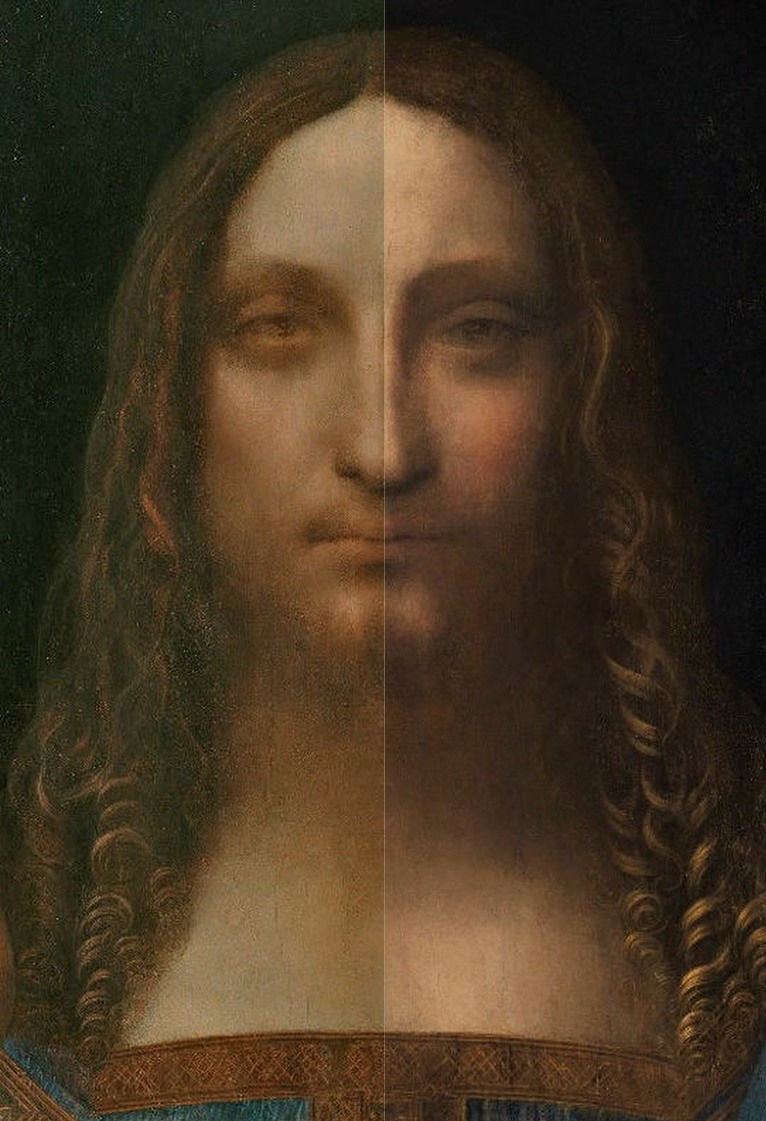

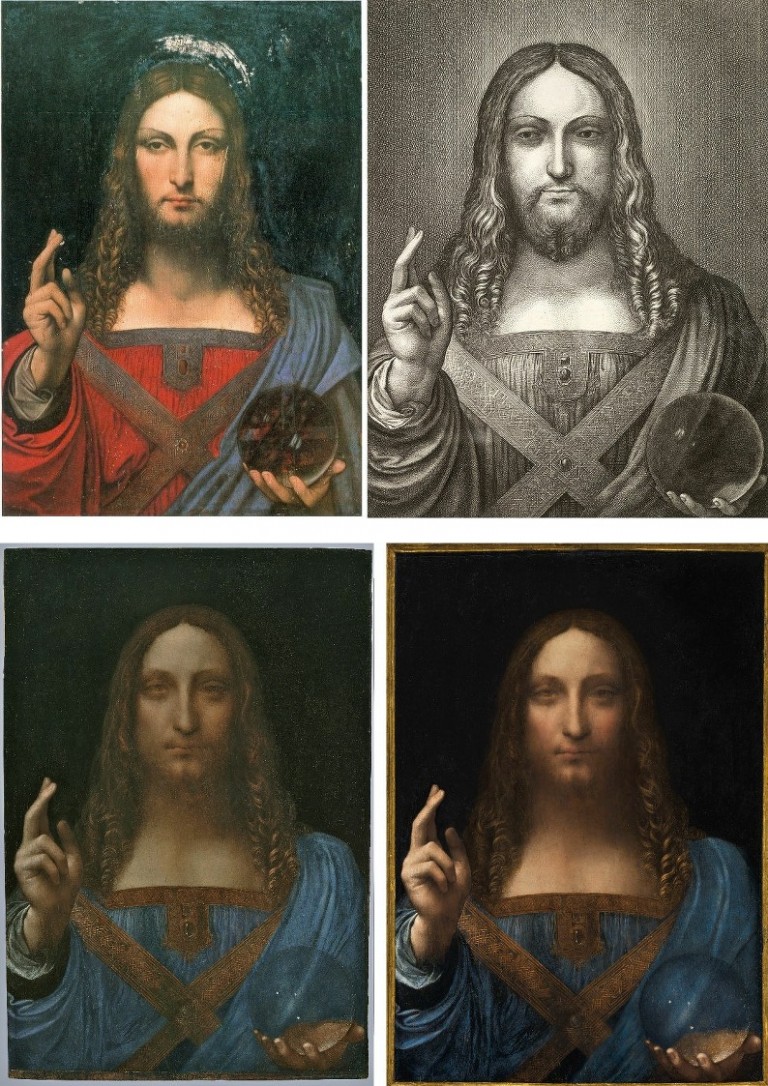

Above, the face in the accredited Leonardo da Vinci Salvator Mundi, as exhibited, left, in the National Gallery in 2011-12, and, right, as when sold at Christie’s in November 2017.

In 1990 the National Gallery remarked that “as a result of” the picture’s 1949 restoration “the differences between the heads are perhaps less apparent”. That being so, either one face had received new glazing or the other had lost original glazing. For Kemp, a crucial technical proof of Leonardo’s authorship of the Salvator Mundi is the fact that technical examinations had disclosed that “As is generally the case with Leonardo, infrared rays delivered the most striking results. It was good to be able to see that the artist had pressed his hand in to the tacky paint above Christ’s left eye – which we have seen to be characteristic of Leonardo’s technique.”

THE UNDERSTANDING TODAY ON THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S OWNERSHIP BETWEEN 2005 AND 2013

In his seventh chapter (“The Saviour”) Kemp twice discusses the ownership of the Salvator Mundi. He does so first with regard to the exclusion from the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition of the “La Bella Principessa” drawing (– whose Leonardo ascription he has energetically advocated):

“This episode highlighted the rationale for the inclusion of the Salvator Mundi. Was it on the market? Would exhibiting it mean that the National Gallery was tacitly involved in a huge act of commercial promotion? It seemed highly likely that it was also ‘in the trade’ [like the ‘La Bella Principessa’]. All I knew at this stage [2011] was that it was being represented by Robert Simon. He told me that it was in the hands of a ‘good owner’ who intended to do the right thing by it, and I did not inquire any further.”

So, it would seem that the National Gallery had not disclosed the identity of the owner/owners to the scholars it invited to appraise the painting. Kemp continued:

“I was keen to consider the painting in its own right, not in relation to its ownership. I speculated, of course, that Robert might have a financial interest, perhaps a share in its ownership; and I assumed that he was gaining some kind of legitimate income from his work on the picture’s behalf. But the gallery was assured that the work was not on the market. Understandably keen to exhibit it, they were happy to accept this assurance…Might the Salvator have been less well regarded if its messy sale [in 2013, privately through Sotheby’s] to Bouvier [for $80m – $68m in cash and a Picasso valued at $12m, according to Georgina Adam in her “Dark Side of the Boom” book] and its resale [to Dimitry Rybolovlev for $127.5m] had been apparent before its public debut [at the National Gallery in 2011-12]? It has turned out to be a substantial mess. In November 2016, an article in The New York Times reported the latest developments: three ‘art traders’ (Robert Simon, Warren Adelson and Alexander Parrish) were disconcerted to find that painting was ‘flipped’ by Bouvier for $47.5m more than their selling price. Was Sotheby’s a knowing party to the the resale? The auction house claimed that it was not, taking pre-emptive legal action to block any law suit by the ‘traders’….It was however a great surprise to find that the Salvator was to be sold at Christie’s in New York on 15 November 2017 at a mega-auction of celebrity works from the modern era. The auctioneers sent the painting on a glamorous marketing tour of Hong Kong, San Francisco and London. I was approached by the auctioneers to confirm my research and agreed to record a video interview to combat the misinformation appearing in the press – providing I was not drawn into the actual sale process.”

Where would we be without a free and vigilant press? Where, precisely, is the $450m Salvator Mundi today?

Michael Daley, 10 April 2018

In Celebration: Paul Anthony Harford, Draughtsman

Recent sickening art world tendencies seem to be crescendoing and calling for some antidote; for some demonstration and reminder of how artistic scruple diligence dedication and humanity might trump the mightiest, most meretriciously hyped, art market-buoyed artefacts and no-talent productions that are currently feted in venerable museums and country piles.

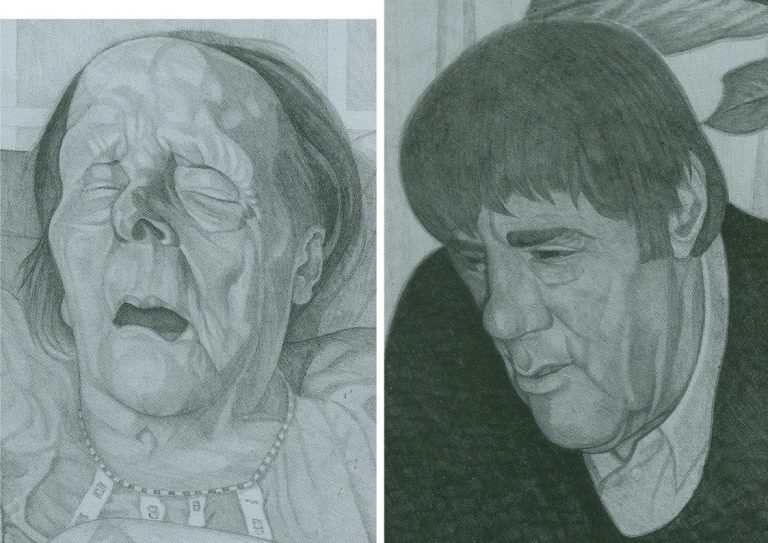

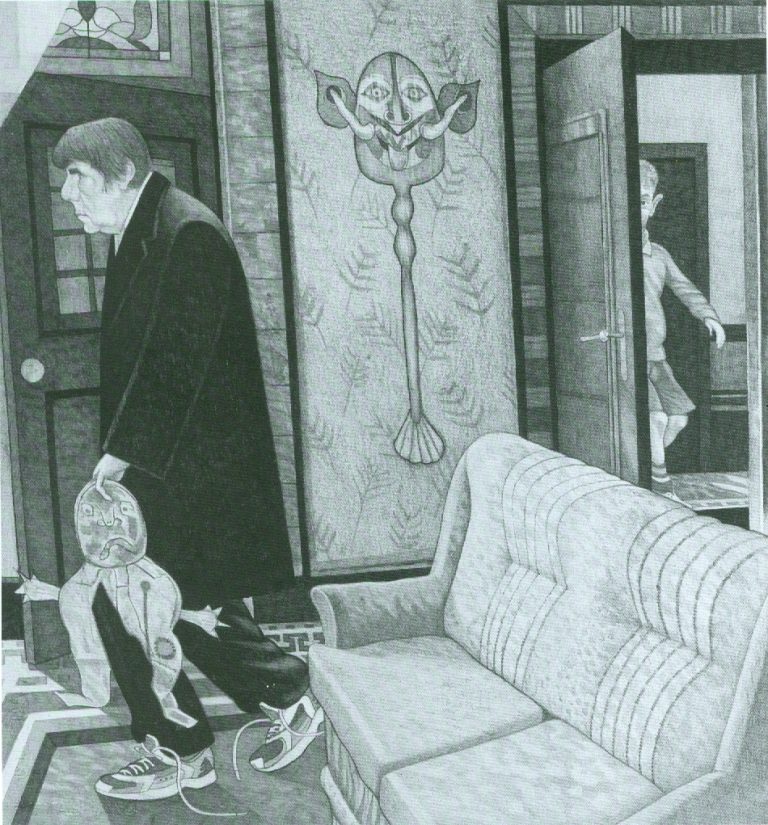

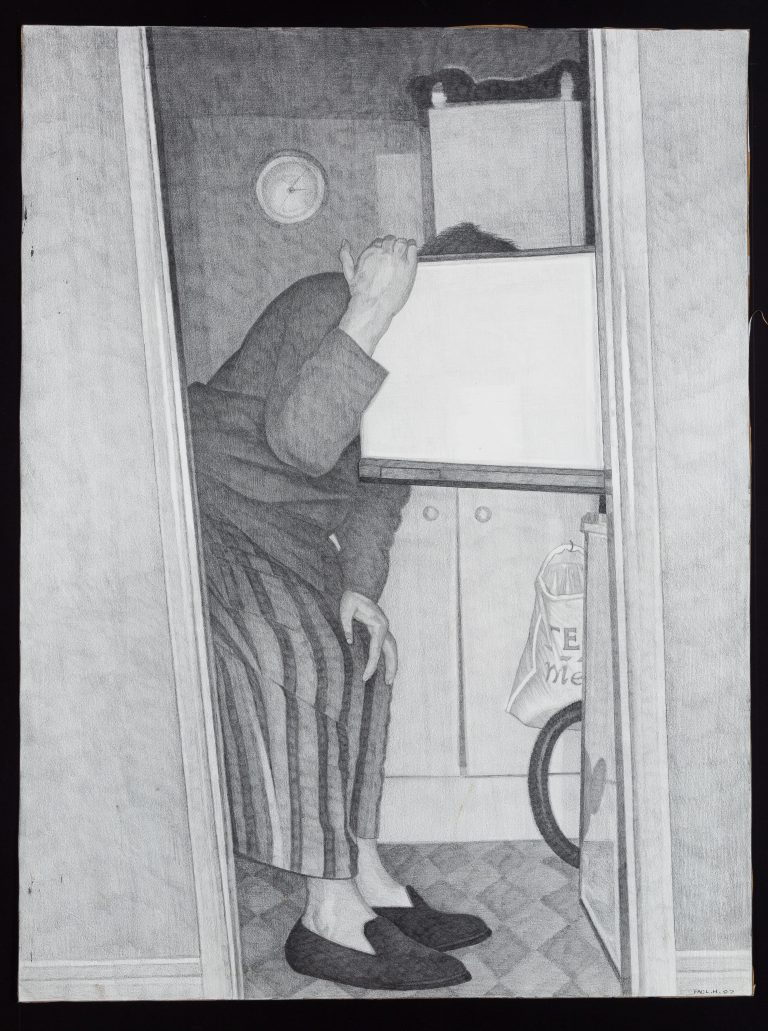

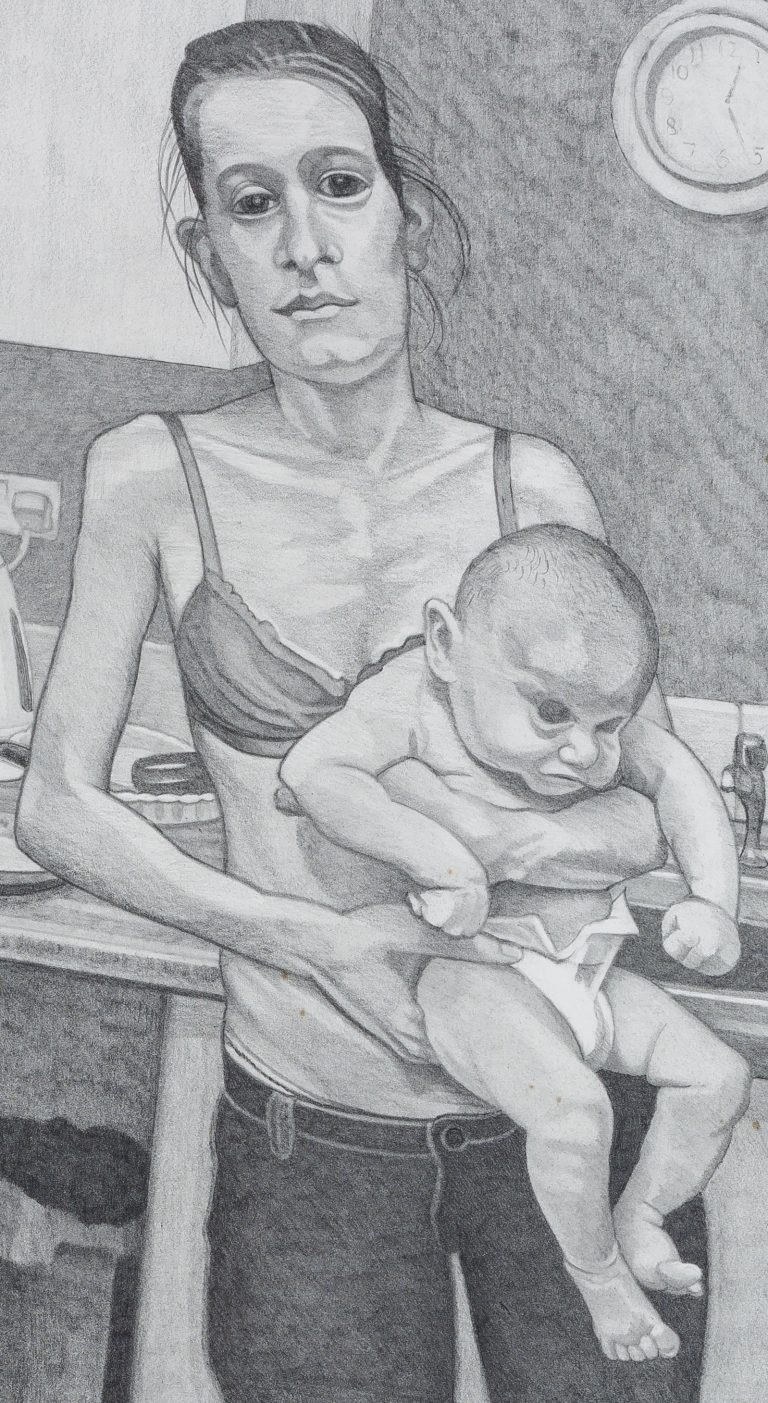

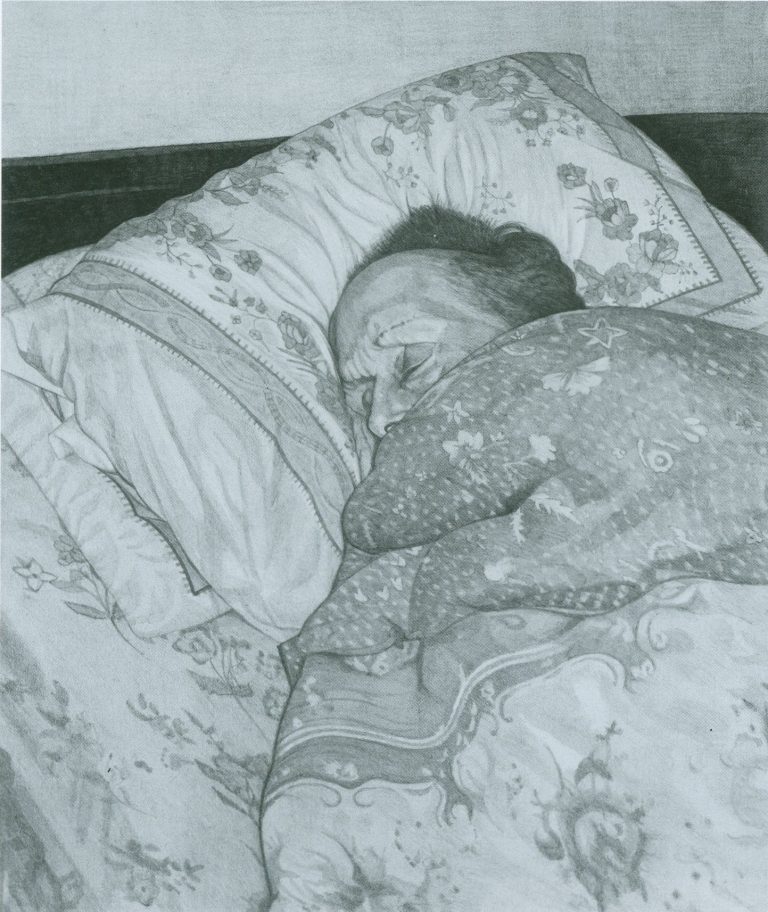

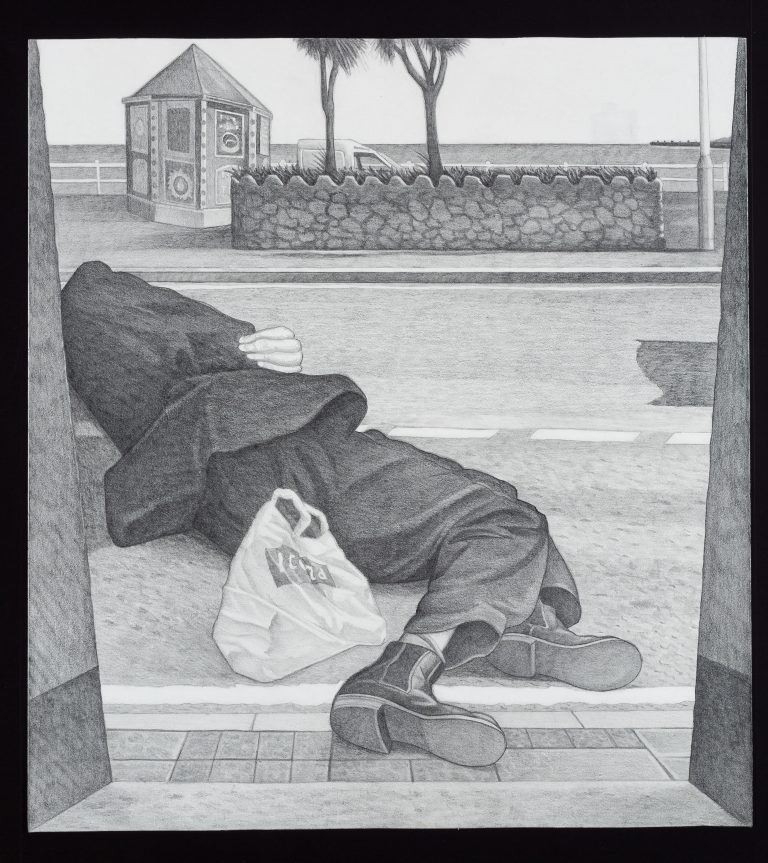

A stunning distinctive show is currently running (until 22 April) at the Focal Point Gallery in Southend-on-Sea. It is accompanied by a modest thoughtful catalogue that celebrates a monumental achievement. An elegant, matter-of-fact foreword by the gallery’s director, Joe Hill, announces an utterly autograph voice and a most haunting corpus of pencil-drawn works (- some examples or details of which are shown below):

“‘Other Voices, Other Rooms’ is an exhibition publication dedicated to the work of Paul Anthony Harford.

“Harford lived and made drawings in Southend-on-Sea and Weymouth, before passing away at the age of 73 in Leigh-on-Sea in 2016. Harford produced hundreds of meticulous, large-scale drawings throughout his lifetime. His remarkable work delicately interrogates the everyday and the commonplace against the background of the faded British seaside.

“Harford attended Byam Shaw School of Art in London as mature student, following this he moved his young family to Southend-on-Sea after a chance advertisement for a seafront flat caught his attention. He secured a job cleaning windows in Southend’s High Street before eventually earning a new position, riding the electric cream and green pier trains to clean the arcades at the end of the pier where he witnessed the devastating fire of 1976.

“His drawings are rooted in his lived experience and shed light on his unique viewpoint of the British seaside town. Often putting himself at the centre of the work, Harford’s drawings disclose some of the underlying truths prevalent in these places. Later in life Harford depicts the seaside as a complex refuge, a site where addictive behaviours are acted out and the typically unseen realities of aspiration and decline are laid bare.

Harford had no real in interest in gaining recognition for his work and so never sought opportunities to exhibit. His emotional connection to the drawings made him unable to contemplate parting with or showing them. They were all kept, stacked several layers deep around the walls of his attic studio.

Unfortunately, I never had the pleasure of meeting Paul before he passed away. I came to know about the work through his family. Since this moment, I have tried to know this character through the illustrated world he had created. The series identifies a seaside life removed from the conventional picture of the bustling Victorian seafront. The draw of these towns as a place of refuge and solace is an all too familiar tale to all us seaside dwellers.

“I would especially like to thank Elsa Harford for her vision, enthusiasm and support throughout this project and her two sons Paul and Stefan Harford for lending the work for the exhibition.”

Michael Daley, 2 April 2018

Startling disclosures on the re-re-restored Leonardo Salvator Mundi

One of the many mysteries surrounding the sale of the Modestini Leonardo Salvator Mundi that fetched $450m at Christie’s on 17 November 2017 was the identity of the under-bidder who staked $370m. The Daily Mail would seem to have the answer:

“EXCLUSIVE: The world’s most expensive painting cost $450 MILLION because two Arab princes bid against each other by mistake and wouldn’t back down (but settled by swapping it for a yacht)

• Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ sold at an auction last November for a record-breaking $405.3million

• It was later revealed the painting’s buyer was Saudi Prince Bader bin Abdullah

• Palace insiders said the purchase was on behalf of the country’s crown prince Mohammed Bin Salman, whose regime was criticized for the purchase

• De-facto United Arab Emirates ruler Mohammed Bin Zayed also sent a representative to bid on the painting at the Christie’s New York auction

• Neither knew the other was bidding, instead they both feared losing the auction to reps from the Qatari ruling family – fierce rivals of UAE and Saudi Arabia

• Qatar’s ruling family was offered the painting just a year earlier for $80 million

• Salman’s $450 million purchase was condemned by critics of his regime

• After facing criticism, he struck a deal with his Emirati counterpart to swap the painting for a superyacht also worth $450 million”

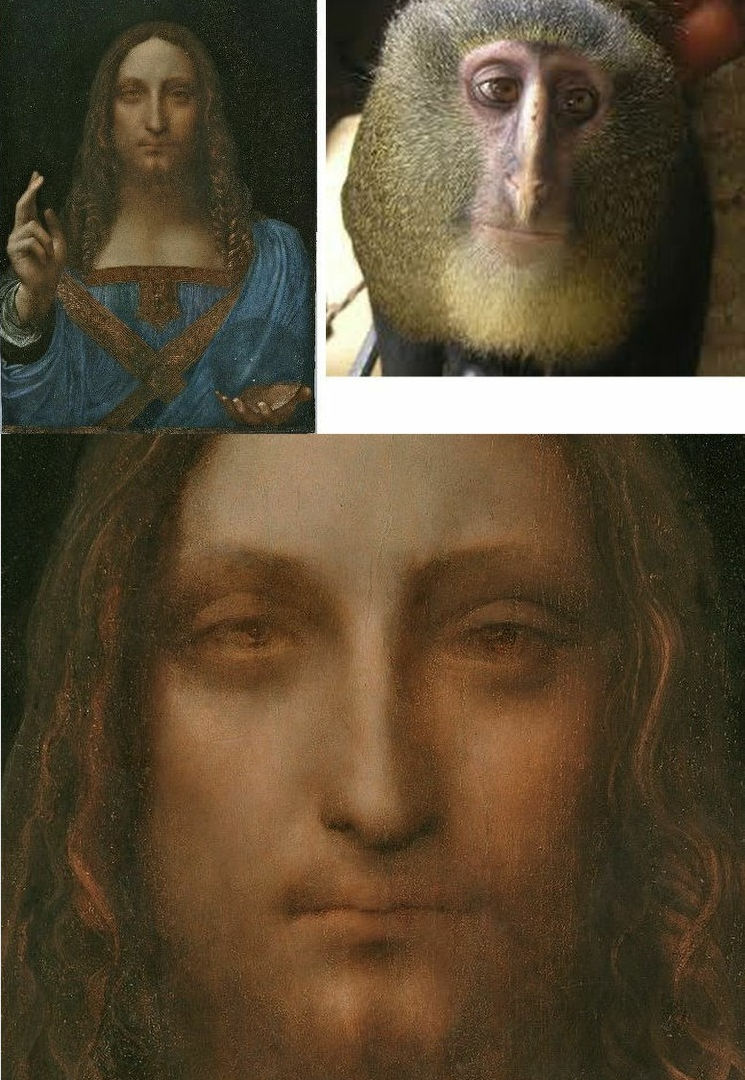

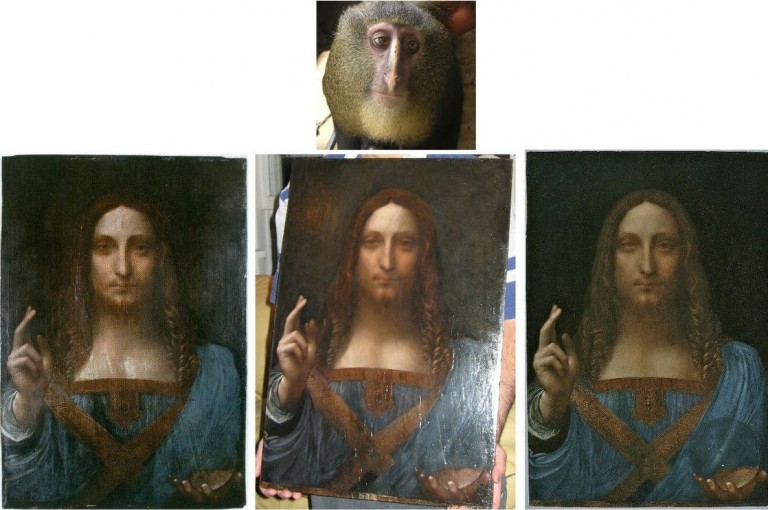

The Mail’s remarkable account rather makes monkeys out of those cheer-leading art market commentators who took the record price achieved by Christie’s as if a confirmation of the (untenable) attribution. See the whole account here:

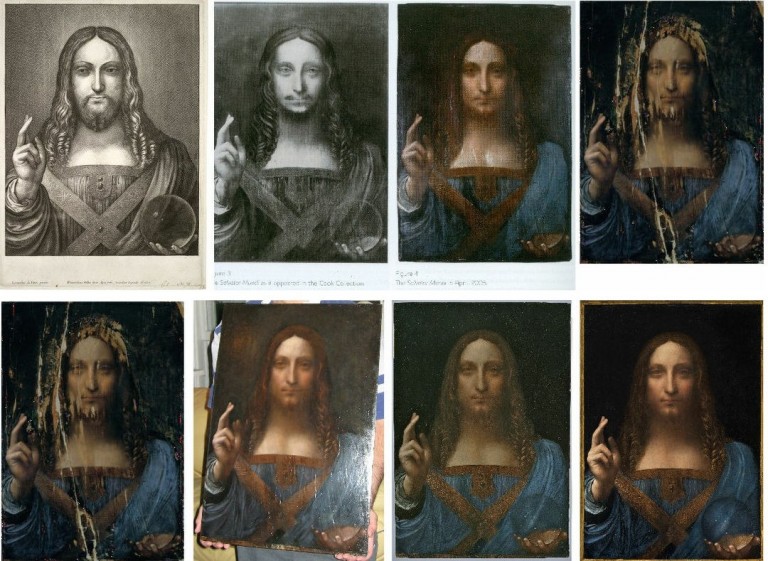

The Royal Academy, having unsuccessfully requested the Dianne Dwyer Modestini Mark III Version of the painting for its (magnificent) Charles I Collection exhibition the day after the sale, may have had a close escape. Curators at the Louvre, who bagged the painting for their planned big Leonardo anniversary exhibition next year, might now be given pause for thought. The Mail article shows the $450m Salvator Mundi not as it was sold in 2017 but as it was exhibited in 2011 at the National Gallery in its Modestini Mark II version. Professor Martin Kemp necessarily reproduced the Modestini Mark II version in the 2011 edition of his book Leonardo but he continues to reproduce that now obliterated version in his new memoir Living with Leonardo – Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond which goes on sale tomorrow.

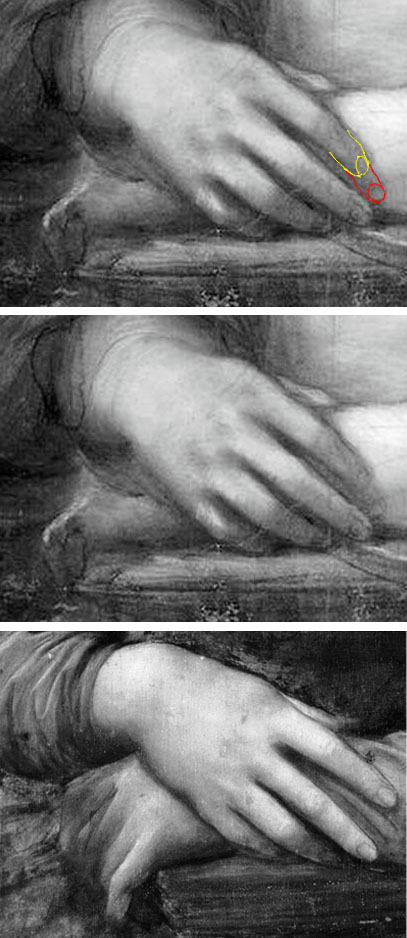

To see the Mark II state of the painting, as in 2011, click on our: The Reception of the First Version of the Leonardo Salvator Mundi . To see the Modestini Marks II and III versions together, click on: The $450m New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part II: It Restores, It Sells, therefore It Is. To see the extent of the changes between 2011 and 2017, click on The “Salvator Mundi” attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, from the authentication in 2011/12 to the sale in 2017, on which site Dr Martin Pracher (- who first spotted the post-2011 re-restoration) shows a number of details in gif formats that will enable even the most aesthetically disadvantaged viewer to appreciate the scale of the transformation this attributed Leonardo had undergone without any acknowledgement by Christie’s before its now-legendary – if not notorious – 17 November 2017 sale.

Michael Daley, 29 March 2018

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: No. 3 [11 March 2018] – The Reception of the First Version of the Leonardo Salvator Mundi

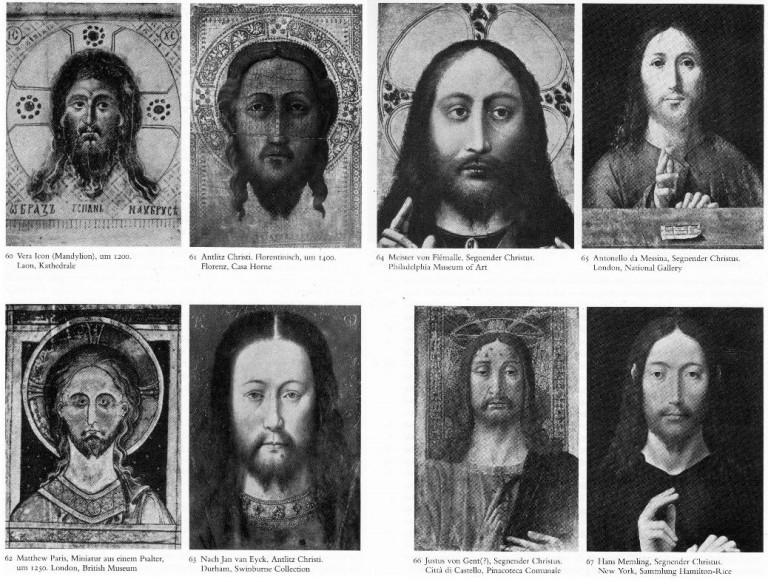

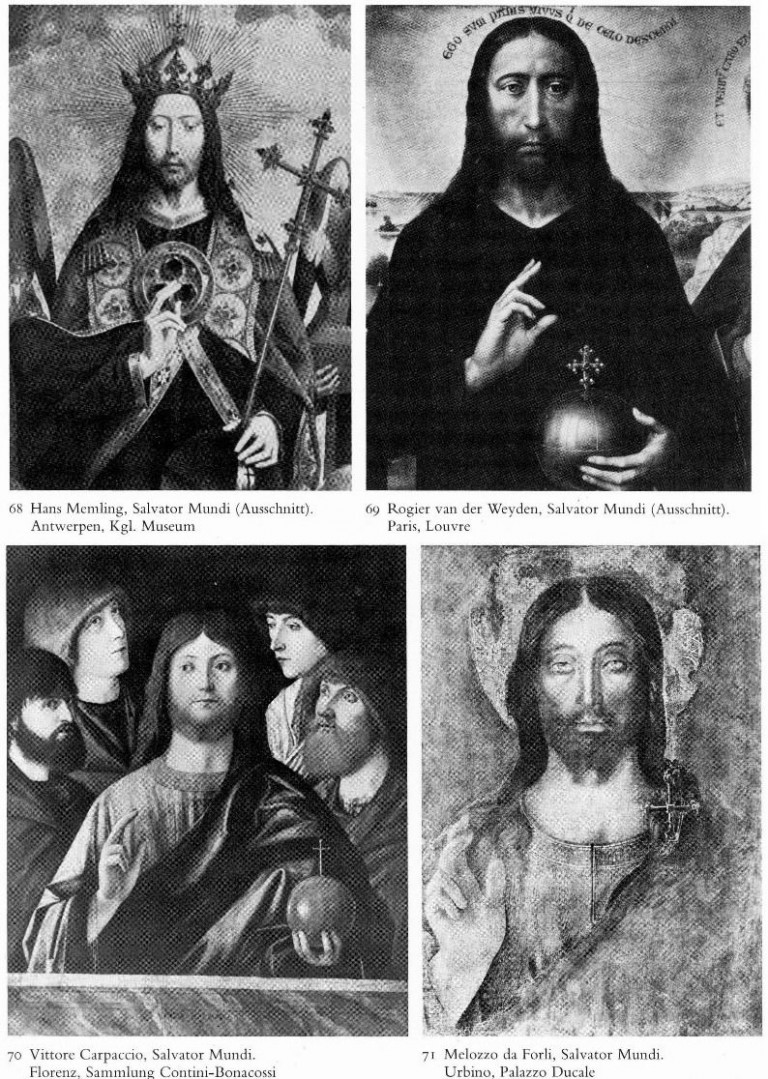

Mounting concerns over transparency in art world deals are throwing back-dated light on the Salvator Mundi’s reception in its first-restored incarnation when included in the 2011 National Gallery exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S FIRST PUBLIC OUTING IN 2011

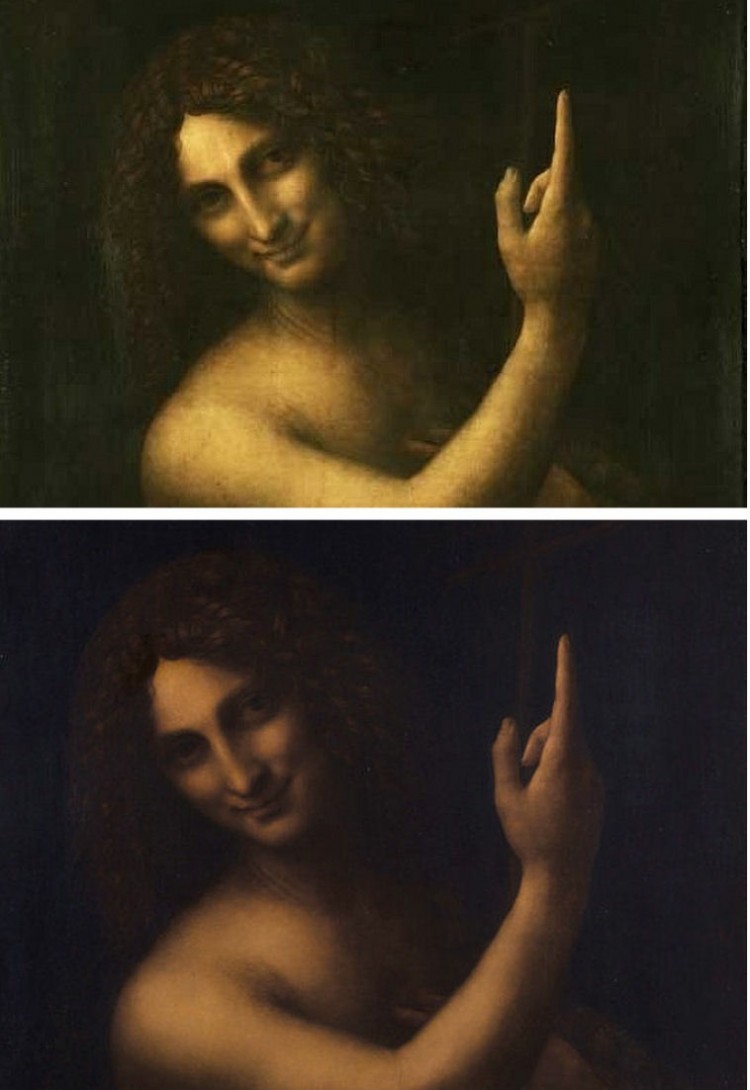

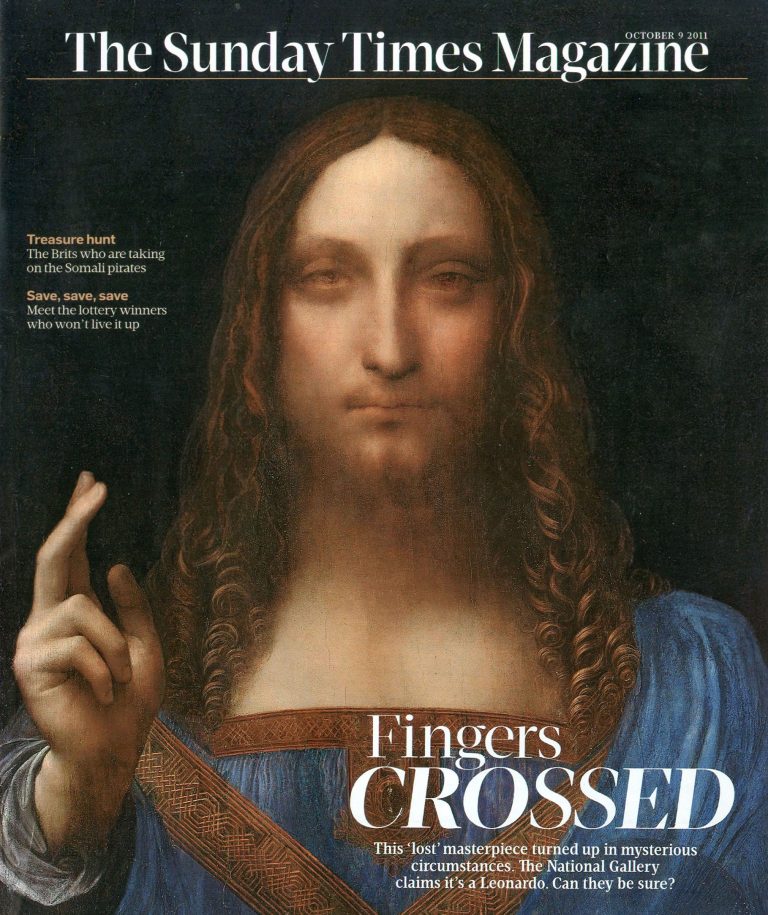

Above, top, the Sunday Times magazine cover of 9 October 2011. Above, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen after repainting in 2011, left; above, right, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen in November 2017 after further repainting between 2012 and 2017.

In the 9 October 2011 Sunday Times (“LEONARDO? CONVINCE ME”), Kathy Brewis wrote:

“For a few weeks in London you will be able to see the Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World) up close. It might be your only chance. Much of the painting’s history remains obscure. Its ownership is a closely guarded secret. Robert Simon, a New York art dealer, is representing the owner or owners – the official line is it is a ‘consortium’. Why all the secrecy? ‘It’s just privacy and security’, says Simon, ‘One doesn’t want people knocking on the door.’

“…He showed it to Mina Gregori, a retired professor at Florence University, who was stunned: ‘I believe it’s by Leonardo.’ Then he showed it to Nick Penny, who had just been appointed director of the National Gallery. ‘He understood it in a nanosecond. He said that one of his ambitions was for the gallery to be a venue for scholarly inquiry and research and that he’d like the painting to be brought to London so it could be compared with the Virgin of the Rocks.’ It was Penny who told him [Simon]: ‘You need a consensus…’

“Since Robert Simon went public with the discovery, he has received many emails from Leonardo fanatics. ‘There’s the serious obsession and there’s the lunatic one – people for whom Leonardo is a source of fantasy. The paintings are not knowable,’ he muses. ‘Every one of them presents a problem and a challenge.’ Even at this stage? ‘Art historians are a prickly, competitive lot. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone stuck their hand up and said “I don’t believe it”’. Could the experts be wrong? ‘They could be wrong about anything. But as much as I believe anything in this world, I believe this is by Leonardo.’”

Above, and top left, the Salvator Mundi as exhibited in 2011 at the National Gallery’s big Leonardo exhibition.

Kathy Brewis continued:

“…Frank Zöllner of Leipzig University [- and author of the Leonardo catalogue raisonné] is a rare dissenter: he thinks the proportions of the nose (‘too long’ for such a perfectionist as Leonardo) make it more likely to have been painted by a talented follower. The rest are convinced, if a little jealous that they didn’t unearth it themselves. ‘People in the art world get sniffy about dealers,’ says Bendor Grosvenor, director of the London fine-art dealership Philip Mould. ‘But if it wasn’t for the trade, discoveries like this wouldn’t be made. Specialist dealers are the ones who are prepared to buy a dirty picture, roll their sleeves up and get stuck in to seeing what it is.’

“Is it wise for the National Gallery to put it on show so soon after its authentication? ‘They are taking a risk,’ says Grosvenor, ‘and I can’t applaud them enough for it. Connoisseurship is a nebulous discipline. There can never be absolute 100% proof. You have to accept there’s an element of doubt and go with it.’”

Note – On 5 March 2018 Grosvenor declared himself an ex-dealer on his blog Art History News: “Now, portraiture can be a hard sell – I know this from having spent over a decade actually selling portraits, in my former life as a dealer.” This did not come as an absolute bolt out of the blue: although he remains a director of the Scottish auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull Limited, last year Grosvenor briefly closed down his website following certain professional criticisms, commenting as he did so: “at the same time AHN also makes me a significant number of, well, ‘enemies’ is not too strong a term. Every walk of life has its Salieris, but in the art market there are an awful lot of them.”

Kathy Brewis continued with a discussion on the Salvator Mundi’s owners:

“Luke Syson, the show’s curator is one of the few people who know who owns the picture. ‘We couldn’t exhibit it otherwise. It’s not being wafted to us in a brown envelope.’”

Ben Hoyle reported the Salvator Mundi’s owners’ plans in the Times of 12 November 2011 (“It’s kind of scary – I wrapped it in a bin liner and jumped into a taxi with it”):

“‘Everyone involved recognises the importance of it as a work of art. Doing the right thing has been very important and will continue to be,’ Mr Simon says. If that means selling it for half the price they could attract, to ensure that it stays on public view, then they would prefer to do that.”

In the event the picture was sold privately by Sotheby’s in 2013 to a Swiss businessman, Yves Bouvier, who is known as the “Freeport King” (and who, among many commercial interests, owns an art conservation and authentication service), for appreciably less than the sums of $150-200m being talked about in 2011 (when the owners reportedly had turned down a $100m offer). The original consortium and Robert Simon received $80m for the Salvator Mundi from Bouvier who resold it for $127.5m to the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev.

To this day we do not know who owned the Salvator Mundi before 2005 or between 2005 and 2013. From whomever and by whomever it was bought in 2005, the painting’s reception as an attributed Leonardo in 2011 was very far from uniformly rapturous. In addition to the dissenting scholars we cited on 14 November 2017 (see THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF THE NEW YORK SALVATOR MUNDI), a number of newspaper art critics were un-persuaded.

In the 13 November 2011 Sunday Telegraph (“The genius of Leonardo”), Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote:

“…The picture is certainly Leonardesque. But is it by Leonardo? That is the considerably-more-than-million-dollar question for the consortium of art dealers who acquired the work a few years ago for an undisclosed sum. If the attribution holds up they can expect to reap £125m as a reward for their good judgement.

“Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan is a breathtaking and truly remarkable exhibition which brings together around half of the surviving 15 or so surviving paintings by the famously dilatory artist of the Italian Renaissance…Two works in particular appear destined to come under scholarly fire.

“Although it gets the thumbs up from the National Gallery’s curator, [Luke] Syson, there will certainly be those who question the new Christ. The picture undeniably displays a number of the painter’s characteristic devices and mannerisms, but there are other aspects of it that seem foreign to Leonardo himself.

“He was prized by his contemporaries as one of the most innovative and forceful painters of emotion, yet the face of this Christ seems peculiarly inert. Taken individually, its elements are convincing enough, but viewed as a whole its expression seems to lack a certain subtle Leonardo magic: the spark of inner life and feeling…”

Even after the picture had been re-done-over by the restorer, Diane Modestini, ahead of the 15 November 2017 sale, the Sunday Times’ art critic, Waldemar Januszczak, responded with less tact than Graham-Dixon (“The Miracle of da Vinci: Turning a £45 Oddity into a £341m Old Master”, 19 November 2017):

“…To call the Salvator Mundi untypical is massively to understate the case. It resembles nothing else Leonardo painted

“The claim by Loic Gouzer, chairman of contemporary art at Christie’s in New York, that the record-breaking Jesus bears ‘a patent compositional likeness’ to the Mona Lisa had me laughing out loud. Yes, it shows the upper half of a figure in a frame. But that is the only compositional likeness the Salvator Mundi shares with the Mona Lisa…

“The next time I saw the painting was in 2011 when the big Leonardo exhibition was opened in London. Full of magnificent loans – the Lady With an Ermine, from Poland; the Virgin of the Rocks from the Louvre – it really was a once-in-a-lifetime event. And there on the wall was the recently rediscovered Salvator Mundi looking just as strange and sci-fi as I remembered it.

“At the time it was owned by a consortium of art dealers who had bought it in an American estate sale for $10,000 as a work by a follower of Leonardo. The dealers had it comprehensively cleaned and repainted. The National Gallery, eager to give its show a boost, announced it as the first new Leonardo discovered in 100 years. Wow…

“Soon after its London unveiling it was sold on to the Russian Billionaire, Dmitry Rybolovlev, for a reputed £98m. It was Rybolovlev who sold it again in New York last week.

“How did Leonardo’s sci-fi Christ, who looks as if he belongs on the cover on one of L Ron Hubbard’s scientology textbooks, end up costing all those shekels? It was mostly due to the wicked brilliance of Christie’s.

“Not only did the auction house tour the picture noisily to Hong Kong, and London before the New York sale, drumming up interest among the newly rich, but its hype department was also in full swing on this one. Finding a new Leonardo, boomed Gouzer, ‘is rarer than finding a new planet’. It’s ‘the greatest discovery of the century’ repeated the Christie’s chorus.

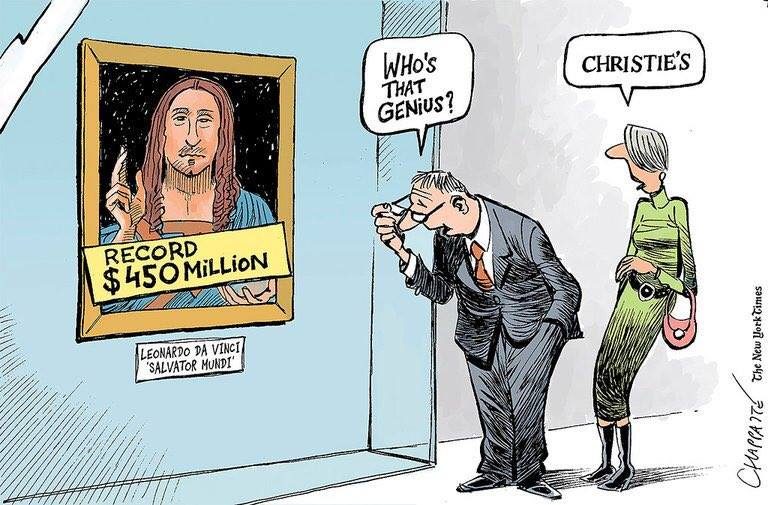

Above, Patrick Chappatte’s take on the Salvator Mundi sale/attribution for the New York Times. Below, Patrick Blower’s incorporation of the Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, for the Daily Telegraph:

Waldemar Januszczak continued:

“In recent years modern art has been where the money goes. A new generation of mega-rich collectors who know a lot about luxury brands but not much about art, have piled into the market and sent prices soaring.

“Earlier this year a quickly splattered Jean-Michel Basquiat of a face shaped like a skull sold in New York for an astonishing £85m. By putting the Leonardo in such a context, Christie’s circumnavigated the knowledgeable world of the Old Master collector and headed straight for the dumb f**** with the money.

“There are various ways to understand events in New York on Wednesday night [of 15 November 2017].

“You can see them as evidence of Leonardo’s treasured and mythic status in art. You can see them as testimony to the power of attribution. Or you can see them as proof that we live in a mad world that has lost sense of true value and in which obscenely rich people waste obscene amounts of money on the obscene acquisition of trophy art. Going, going, gone.”

SUPPORT AND DISSENT

It so happens that the scholar who first attributed the Salvator Mundi to Leonardo, Professor Mina Gregori, was also the first scholar to attribute the proposed Leonardo drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Professor Martin Kemp. However, “La Bella Principessa” was not included in the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition and, seven years later, it remains unsold. Although we know precisely why the dissenting scholars rejected the Salvator Mundi attribution (- they published their views in the scholarly press), we have virtually no information of who said what and in what order among the consensus of scholars listed by Christie’s (see Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation).

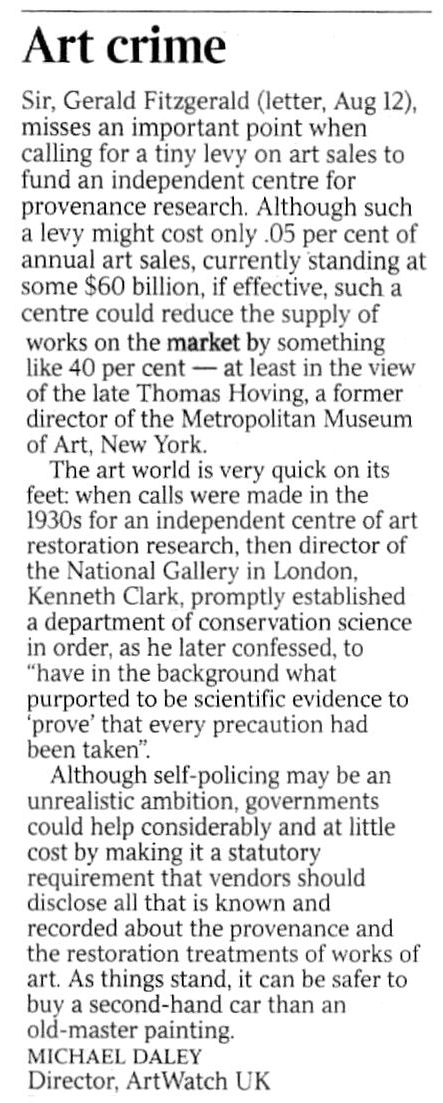

SECRET DEALS – AND THE ARTS CLUB

Since we began warning on this site in 2014 of the threat to market confidence posed by the art world’s toxic attributions and specifically called for increased transparency through a statutory requirement that vendors should disclose all that is known and recorded about the provenance and the restoration treatments of works of art (“As things stand, it can be safer to buy a second-hand car than an old master painting” – “Art crime”, ArtWatch UK letter, the Times, 13 August 2014), secret deals have come under increasingly intense investigation. In her 2017 book Dark Side of the Art Boom, Georgina Adam wrote:

“At its base, the Bouvier/Rybolovlev dispute was about the nature of their business conducted within a market that has always thrived on secret backroom deals. By keeping vendors and buyers apart – they may never know who the other is – and insisting on discretion, agents, dealers, advisors can use this anonymity to their advantage. Various reasons can be put forward, from the need for security to the desire to avoid family quarrels or the taxman, to the risk of someone else bagging the work for sale. In the Bouvier/Rybolovlev case, one of Bouvier’s emails about a Magritte, said: ‘I must carry out this [negotiation] with the greatest discretion to avoid drawing attention to the painting and its owner; the risk is that we could lose it at auction.”

In this weekend’s Financial Times (10/11 March 2018 – “Laundering Picasso: British dealer among accused in $50m case”), Melanie Gerlis cites the emergence of another highly embarrassing series of documents:

“Potential shenanigans involving art are in the spotlight once again. London art dealer Matthew Green is among defendants in the case against Beaufort Securities, three other corporations and five other individuals, accused by the US Department of Justice of a multiyear $50m-plus securities fraud and scheme to launder money, partly through the sale of a £6.7m painting by Picasso.

“The indictment alleges that Green, described as the owner of Mayfair Fine Art Limited, met last month with an investment manager from Beaufort Securities (now declared insolvent), as well as a property developer and an undercover federal agent masquerading as a client of the brokerage firm. At this meeting held around February 5, the court papers say that the agent-client was told he could ‘purchase a painting from Green using the proceeds of the stock manipulation deals and later sell the painting to “clean the money”’…The papers describe the art business as ‘the only market that is unregulated’”.

“The papers also say that Green – who had allegedly asked for a 5 per cent profit on the transaction, ‘so that he would not be asked why he was in the money laundering business’”. [Green] sent a message via What’sApp to the Beaufort Securities manager that read: ‘[O]bviously because of the nature of this transaction we need to preserve a certain amount of anonymity which [the undercover agent] and I discussed and clarified at the Arts Club!’”

UNDERCHARGING FOR CURRENT MARKET PRACTICES

The Art Market Monitor blogger, Marion Manneker, made this observation in his (5 March) comments on the trial:

“Green doesn’t seem to know that the price for laundering money is much higher than 5% which definitely isn’t worth the risk if it gets you indicted after being in business all of three months. Worse still, Green and his partners don’t seem to be the swiftest criminals. They boasted that the art market is unregulated but then created a scheme that seems to have had little to do with the art market itself.

“The art sale is only one of several money-laundering venues that the person was offered. Offshore banks and real estate deals figure prominently in the indictment. What’s more, Green’s scheme could have been conducted in just about any commercial transaction. And, since the payment for the Picasso was due March 6, 2018, we’ll never know if Green was actually capable of pulling off the sale at the price he claims or would have survived any kind of audit.”

OLD HABITS DIE HARD?

Manneker’s comments on the cut-price scale of Matthew Green’s alleged laundering service charges recalls certain comments of Kenneth Clark who recognized that his appointment as director of the National Gallery at a very tender age owed much to the fact, as he wrote in his 1977 memoir Another Part of the Wood, that:

“[T]he ideal candidate for the post was disqualified. This was a Finnish art-historian named Tancred Borenius. He was a good scholar, a pleasant companion and a passionate upholder of the concept of the monarchy. He would have made an ideal courtier. Unfortunately, he was known to have followed the continental practice, described above, of taking payments for certificates of authenticity; and what was worse, quite small payments (known as ‘smackers under the table’); if he had taken large payments like a few scholars on the continent, no one would have objected.”

Michael Daley, 11 March 2018

UPDATE, 12 March 2018. On 11 March, a Sunday Telegraph supplement (“Arts, Antiques and Collectibles”) carried a “Promotional feature” – “Managing Risk When Buying and Selling Art” – for the law firm Constantine / Cannon. In offering the firm’s services, the article began:

“TRADING IN ART has traditionally been done on a handshake, but this is changing. You would not buy or sell a house without relying on a lawyer to prepare the contract, would you? The same goes with art, and now buyers and sellers are increasingly turning to lawyers to help them manage the risks associated with expensive works. The art market used to function like a club of like-minded people, but that’s no longer the case. The market now is truly global, and it has become less transparent in the process…”

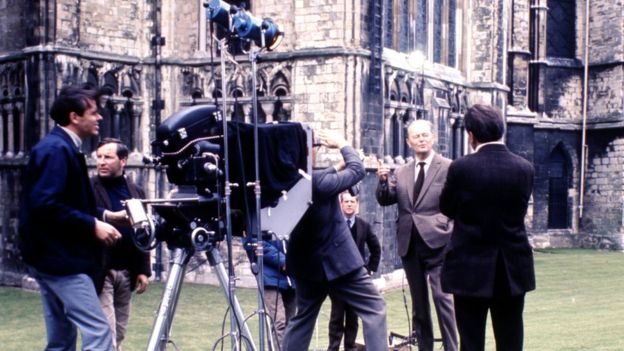

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: No. 1 – Civilisations and Burrell Loans

It’s official: the BBC remake of Kenneth Clark’s highly acclaimed television series Civilisation is an intellectually incoherent artistically obtuse “right-on” mish-mash. It is official: Glasgow is repeatedly dicing with Burrell’s bequeathed art for financial peanuts and supposed profile enhancement.

NICE PICTURES, POOR WORDS

Above, top, Kenneth Clark shooting on the still-acclaimed 1969 series Civilisation; above, Simon Schama fronting the scathingly-received 2018 multi-voiced Civilisations outside Itimad-ud-Daulah’s Tomb in Agra, Uttar Pradesh.

“…By adding a single pluralising letter to the classic BBC art history series Civilisation (1969), the programme makers of Civilisations opened up the tantalising possibility of producing a new TV series that didn’t simply match its singular predecessor, but was much better.

“You can see the sense in the idea. Instead of an old-fashioned, patriarchal, white, western, male view of human cultures and creativity, why not make a show that acknowledges there are different civilisations and different views, which can be put across by different presenters? (In this case, three TV-ready, scarf-wearing academics: Mary Beard, David Olusoga and Simon Schama.) …from the programmes I have seen, Civilisations is more confused and confusing than a drunk driver negotiating Spaghetti Junction in the rush hour.

Above left, Aphrodite of Menophantos, Praxiteles, (4th Century BCE), Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome; above, right, Hand Stencils found in the Cave of El Castillo in Spain.

“The series starts with Schama – who has ‘always felt at home in the past’ – showing us library footage of an Islamic State wrecking crew in Mosul destroying ancient art and artefacts.

“He tells us the grisly story of how they brutally murdered the 82-year-old Syrian scholar Khaled al-Asaad for withholding information from them as to the whereabouts of the antiquities under his curatorial care in Palmyra.

“‘The record of human history brims over with the rage to destroy,’ the historian tells us with his passion dial turned up all the way to 11 (it rarely dips below 10).

“There is no mention made of similarly barbaric acts that have taken place over millennia – on occasion perpetrated by a civilisation much closer to home – or an explanation as to the cultural rationale behind the actions of those wielding the sledgehammers in this instance.

“…Music swells, titles roll, and we’re off – back to the beginning and the caves of South Africa, where we are shown a 77,000-year-old block of red ochre with the ‘oldest deliberately decorative [human] marks ever discovered’.

“This is ‘the beginning of culture’, Schama tells us, but he doesn’t dwell. Moments later we’re travelling through time and space like Doctor Who in a sci-fi remake of Treasure Hunt, touching down around 40,000 years later in northern Spain to visit El Castillo Cave.

“Here, both the programme and the presenter start to settle down and enjoy what they’ve brought us to see: cave paintings and hand stencils.

“Apparently similar images have been found ‘as far apart as Indonesia and Patagonia’, which is interesting. But then frustrating as no explanation is forthcoming to enlighten us as to why that might be.

“We are told: ‘These hand stencils do what nearly all art that would follow would aspire to. Firstly, they want to be seen by others. And then they want to endure beyond the life of the maker.’

“Really? Was that actually the motivation behind our stencil-making ancestor? Was he or she honestly most concerned with artistic ego and posterity? Were the painted hands even intended as art? Could they not have been a functional way-finding device or a ritualistic mark or part of a magical spell?

“…These are patchwork programmes with rambling narratives that promise much but deliver little in way of fresh insight or surprising connections.

Above, Mary Beard fronting Civilisations at the Colossi of Memnon in Luxor, Egypt.

“Mary Beard’s episode, How Do We Look, is particularly disappointing because the premise is so enticing, as is the prospect of one of our foremost thinkers on matters cultural giving us a new perspective.

Sadly, other than a couple of memorable TV moments when Beard encounters an ancient statue for the first time, we are offered little to excite our imaginations.

We don’t get the alluded-to update on Clark’s Eurocentric views or on John Berger’s Walter Benjamin-inspired Ways of Seeing series.

There is no substantial new polemic with which to wrestle. Instead we are served a tepid dish of the blindingly obvious (art isn’t just about the created object but also about how we perceive it), and the downright silly (an ancient story about a young man who supposedly ejaculated on a nude sculpture of Aphrodite thousands of years ago, which Beard describes with great theatricality as rape – ‘don’t forget Aphrodite [the stone statue] never consented’).

Above, David Olusoga fronting Civilisations with Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“David Olusoga is altogether more measured and less mannered than his fellow presenters. His two films – one exploring the meeting of cultures between the 15th and 18th Centuries, the other looking at the enlightenment and industrialisation – benefit from his inquisitive nature and relaxed style.

“If the scripts in the series are far from being literary masterpieces, the camerawork is of the highest quality throughout – although there are too many stylised shots of out-of-focus presenters with their backs to us.

“But when trained on art and artefacts, the new technology and techniques at the 21st Century TV director’s disposal provide us with plenty of delicious visual treats (the images from Simon Schama’s trip to Petra are stunning).

“Ultimately though, Civilisations feels like a series made by committee: a terrific-sounding idea on paper that I suspect was a lot harder to realise in practice.

“The result is a well-intentioned, well-funded series that has top TV talent in all departments but which ended up being less than the sum of its parts. A case of too many cooks, maybe?”

– Will Gompertz, the BBC’s art editor (Will Gompertz review: Civilisations on BBC Two 3 March 2018).

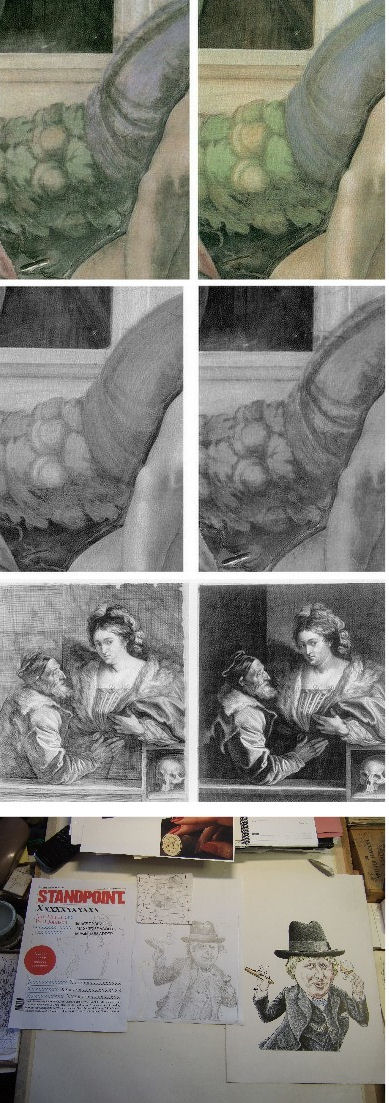

NICE PICTURES, NEEDLESS MULTIPLE RISKS

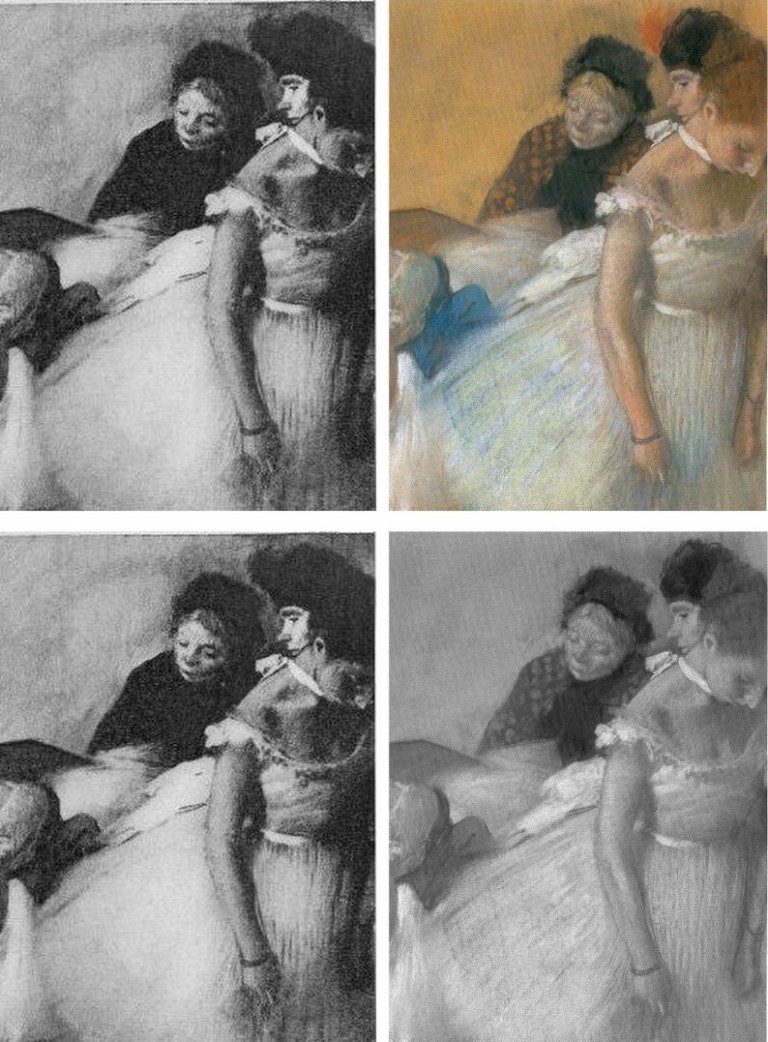

Above, Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal (1874) CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

“Fascinating details about a tour of the Burrell Collection’s late 19th-century French paintings have been revealed. Financial data on touring exhibitions is normally highly secret, but the Burrell’s data has been recorded in a report for a Glasgow City Council meeting on Thursday (8 March). This meeting is expected to approve the exhibition loans.

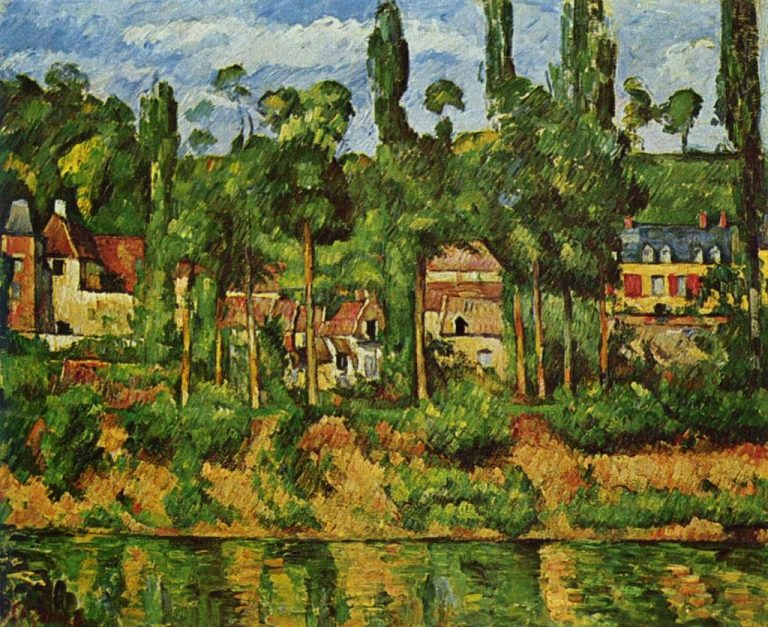

“A group of 58 works is being lent to the Musée Cantini in Marseille, which reopens on 18 May after refurbishment. The council report values the 47 paintings and 11 works on paper at £180.7m. The pictures include Degas’s The Rehearsal (around 1874) and Cézanne’s The Château of Médan (around 1880).

“Although the Japanese tour will be larger, with 55 paintings and 25 works on paper (including seven non-Burrell works from Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum), the value of the loans will be lower: £141.8m.

“What is even more interesting [is] the complex financial details of the deal. No fee is being paid by the Musée Cantini, but a sponsor is assisting the Burrell. It will contribute €100,000 towards the exhibition costs and €50,000 towards the Burrell’s refurbishment costs. The Art Newspaper understands that the sponsor is likely to be the London-based financial advisors Rothschild & Co and its new Marseille banking partner, Rothschild Martin Maurel.

“The Japanese tour, which will go to five venues from this October to January 2020, is being financed on a different basis. Each venue is paying a hire fee of £30,000, plus £1 per visitor after the first 100,000. If, for the sake of argument, each venue attracts 150,000 visitors, then the full total from Japan would be £400,000 (plus €50,000 for the French venue).

“When the tour idea was first considered, five years ago, the Burrell hoped to raise many millions from a touring exhibition, but this target has proved much too ambitious. James Robinson, the director of the Burrell Renaissance project, says that ‘profile raising for the Burrell and for Glasgow is just as important as the funding’.

“The Burrell Collection… building is now in need of a fundamental refurbishment. The cost of the refurbishment project is estimated at £66m, which means that the touring shows may bring in around 1% of the total. Glasgow City Council is to provide up to half the £66m and the Heritage Lottery Fund has awarded £15m, with contributions from other donors.

“Under the terms of Burrell, who died in 1958, his works could not be lent abroad because he was concerned about transport risks. In 2014 the Burrell trustees obtained special approval from the Scottish Parliament to enable them to lend abroad. The collection’s works by Degas are currently on loan to London’s National Gallery, until 7 May.

“The Burrell Collection closed for refurbishment in October 2016 and is due to reopen in late 2020.”

– Martin Bailey, “Revealed: the profits of staging a touring exhibition”, The Art Newspaper, 5 March 2018

Above, Cézanne, Château de Médan (1880) CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Michael Daley, 5 March 2018

Coda: For our earlier words on the overturning of the terms of Burrell’s bequest, see:

“Protecting the Burrell Collection ~ A Blast against Risk-Deniers”;

Nouveau riche? Welcome to the Club!

Our previous news/notice – “A day in the life of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s pricey new Leonardo Salvator Mundi” – was pegged on Georgina Adam’s Financial Times interview with Christie’s CEO, Guillame Cerutti.

In today’s Art Market Monitor blog, Marion Maneker defends Georgina Adam’s book, The Dark side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, against a review in The New Republic:

“Unfortunately, [Rachel] Wetzler’s idea of a critique is to somehow fault Adam for not belabouring the obvious context of her book:

‘But while Adams paints a detailed and convincingly dire picture of the art world’s excesses, she never fully probes its implications. Perhaps ironically, its central weakness is her narrow focus on the activities of the art market itself: Her book largely brackets an exploration of the art market from the broader context of rising income inequality, economic exploitation, and staggering concentrations of wealth in the hands of the very few, all of which have enabled activity at the its upper reaches to continue unabated despite global downturns in other financial sectors. According to the sociologist Olav Velthuis, the art market ultimately benefits from an unequal distribution of wealth, as newly minted billionaires turn to blockbuster art purchases as a means of announcing their arrival…’”

Maneker dismisses the general charge as “both obvious and silly” but sows confusion with a claim that the rich “have many ways to announce their arrival” other than by social climbing. While that, too, may be self-evident it distracts from the force and precision of Adam’s analysis of certain shortcomings within the art market’s own institutions. When speaking of an apparent art world unwillingness to eliminate decades-long fraudulent practices – even after the most revelatory scandals – Georgina Adam (p. 191-2) pinpoints specific failures:

“What is surprising is the lack of impact the art market scandals have actually had, as lawyer Donn Zaretsky told me:

‘I haven’t seen much change after Knoedler [’s great Fakes Scandal]…I still see people doing deals on a handshake. The fact is the art market is a market but also a social world. If people are buying Tribeca real estate they will do the necessary research, bring in the lawyers, stitch up the contracts, and yet if they buy a picture for $3m they will hardly do anything.

‘It’s all part of this social world, meeting the artist, going to the parties. And buying art is an entrée to this world. You need to understand this in order to understand why these things happen, and why the art market will be so hard to regulate.’”

Marion Maneker’s Art Market Monitor blog of 22 February linked to a discussion between Glenn Fuhrmann and Lary Gagosian and noted that: “in this interview, one can see some indications of how deeply Gagosian’s success is tied to his ability to create among his clientele the sense of belonging to an exclusive club.”

There exist further three-way relationships between dealers, auction houses and collectors. Gagosian reportedly underwrote the recent $450m sale at Christie’s of the Salvator Mundi with a $100m guarantee to buy. This is said to have been in exchange for a $60m guarantee from the Salvator Mundi’s vendor to buy – in the very same auction of modern art – a Gagosian-owned Warhol of Leonardo’s Last Supper.

Michael Daley, 27 February 2018

A day in the life of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s pricey new Leonardo Salvator Mundi

On February 10th the Financial Times carried an interview – “The king of King Street” – with Guillame Cerutti, the French-born and École Nationale d’Administration-educated CEO of the (French-owned) British auction house, Christie’s, by Georgina Adam.

On the same day as the interview by Georgina Adam, author of Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses Of The Art Market In The 21st Century, the French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe, toured the Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum on Saadiyat island in the Emirati capital, to launch the French-Emirati “Year of Cultural Dialogue” in the company of Shiekh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, CEO of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (see Figs. 4 and 5).

Above, Fig. 1: Christie’s CEO Guillame Cerutti, as photographed by Anna Huix for the FT, 10 February 2018.

Georgina Adam asked Christie’s CEO if he had been surprised by the price of the Salvator Mundi sold at Christie’s, New York, on 17 November 2017 for $450 million (as an entirely autograph Leonardo da Vinci painting):

“He pauses. ‘Yes, because before the sale it was difficult to ask anyone to predict that level. But at the same time our major clients are looking for trophies. They want quality and rarity in any field. This painting had both aspects, it ticked all the boxes.’”

On 11 December 2017 money.cnn reported that Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism had confirmed that it had purchased what was the most expensive painting in the world for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the museum’s first outpost outside France, but it had declined to comment on the owner. The New York Times had reported (“Mystery Buyer of $450 Million ‘Salvator Mundi’ Was a Saudi Prince”) that the man behind the purchase was a little-known Saudi prince named Bader bin Abdullah bin Farhan al-Saud, an associate of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Saudi Arabia, through its embassy in Washington, subsequently said that the prince was acting as a middleman for the United Arab Emirates, a key ally in the region: “His Highness Prince Badr, as a friendly supporter of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, attended its opening ceremony on November 8th and was subsequently asked by the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism to act as an intermediary purchaser for the piece.”

When Adam asked about the Salvator Mundi painting’s condition Guillame Cerutti responded:

“There were questions on that, we didn’t hide anything. It is 500 years old and the condition reflected that – but we were transparent about this. It is a beautiful painting, and the day after the sale, the Louvre requested it for an exhibition in 2019.”

In Christie’s pre-sale essay “Salvator Mundi – The rediscovery of a masterpiece: Chronology, conservation, and authentication” the painting was said to have been discovered in 2005 “masquerading as a copy” in a “regional auction” in the United States. The curiously anthropomorphised notion of an inanimate artefact seeking to deceive, might no less appropriately be applied today to a damaged and covertly re-restored painting that still lacks a secure provenance. The essay’s account of the work’s “conservation” revealed that in 2007 “A comprehensive restoration of the Salvator Mundi is undertaken by Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Senior Research fellow and Conservator of the Kress Program in Paintings Conservation at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.” Modestini was said to have concluded that: “the important parts of the painting are remarkably well-preserved, and close to their original condition”.

Above, Figs. 2 and 3: showing the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi when exhibited in 2011-12 as an entirely autograph Leonardo in the National Gallery’s Leonardo da Vinci ~ Painter at the Court of Milan exhibition, left; and then, right, as offered for sale by Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017.

In its pre-sale lot essay on the painting, Christie’s acknowledged an “initial phase of the conservation” that ran from 2005 to 2007, and that the entire conservation programme had been brought to completion in 2010 before the painting was included as “The newly discovered Leonardo masterpiece, dating from around 1500” in the National Gallery’s major Leonardo exhibition of 2011-12. The essay notes that the painting had been acquired from “an American estate”. At no point before the November 2017 sale, so far as we know, had Christie’s acknowledged the further extensive campaign of restoration that we have shown to have occurred between 2012, when the picture returned from London to New York, and the November 2017 sale where it fetched $450 million and caused some commentators to fear that an important and vital market might be “on the edge of becoming seriously troubling” – see: “The $450m New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part II: It Restores, It Sells, therefore It Is”.

Notwithstanding Mr Cerutti’s FT interview, we still do not know when – or to what purpose – restoration was resumed after the National Gallery Leonardo exhibition but, as we have reported, a Christie’s spokeswoman confirmed to the Daily Mail in December 2017 that Dianne Modestini, had worked on the painting “Prior to its presentation for sale at Christie’s”. (See “Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo da Vinci painting which became world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in the last five years”.)