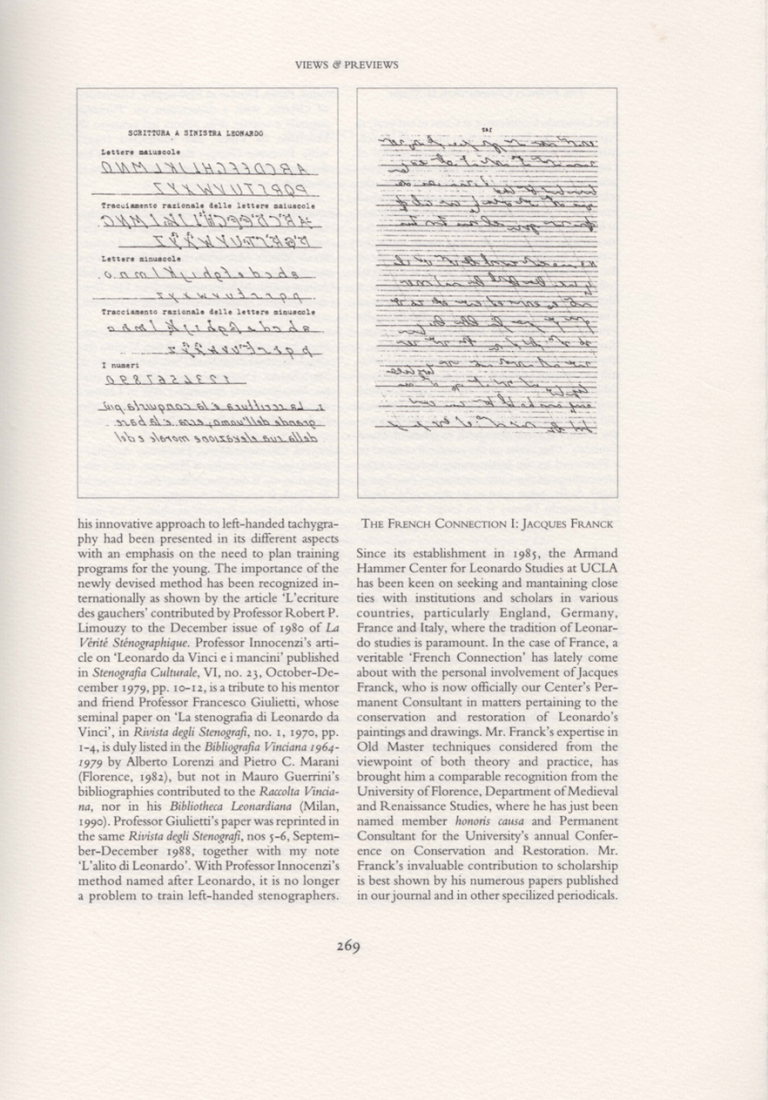

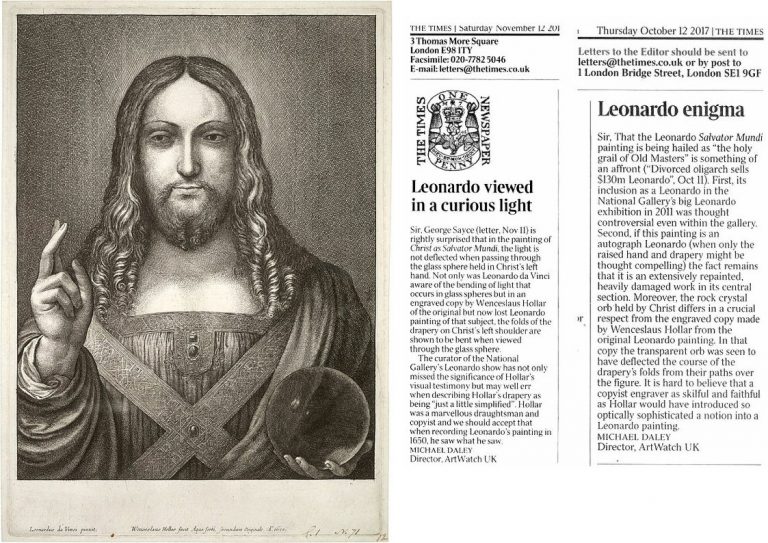

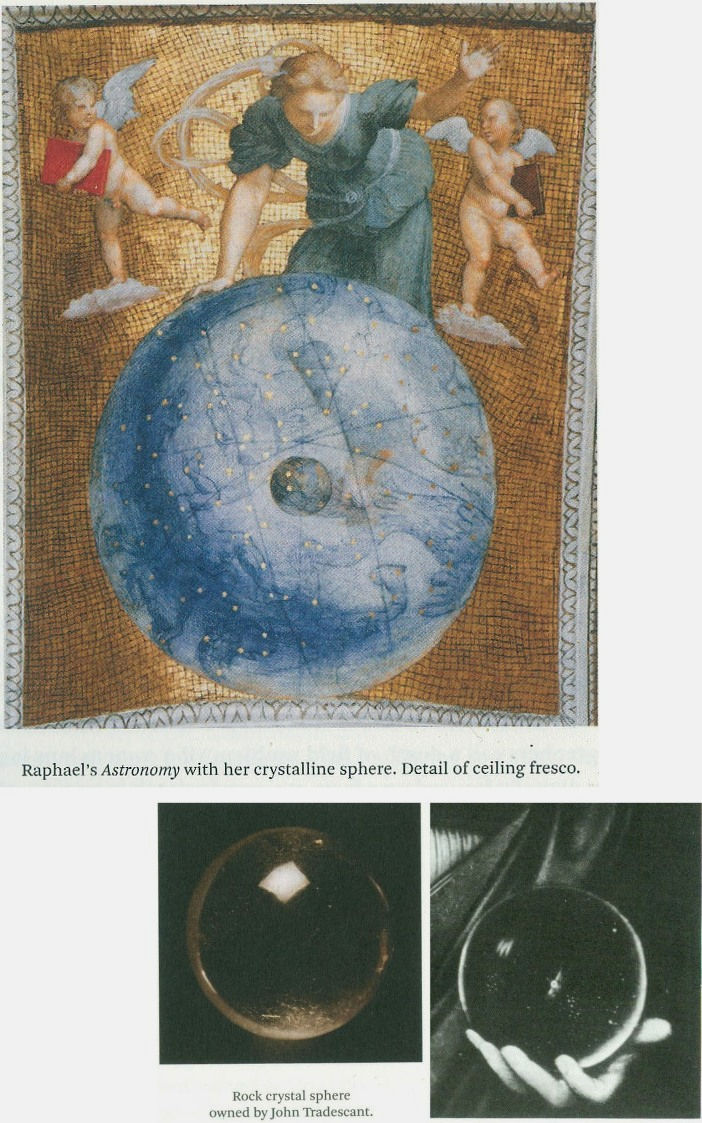

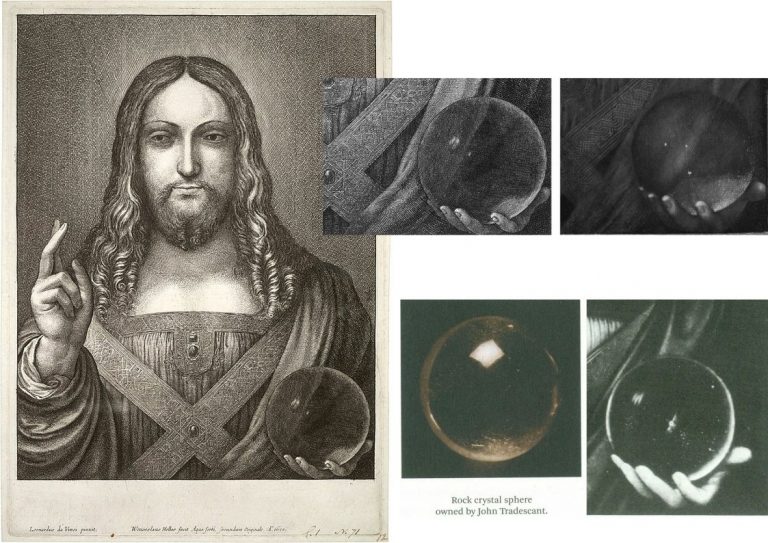

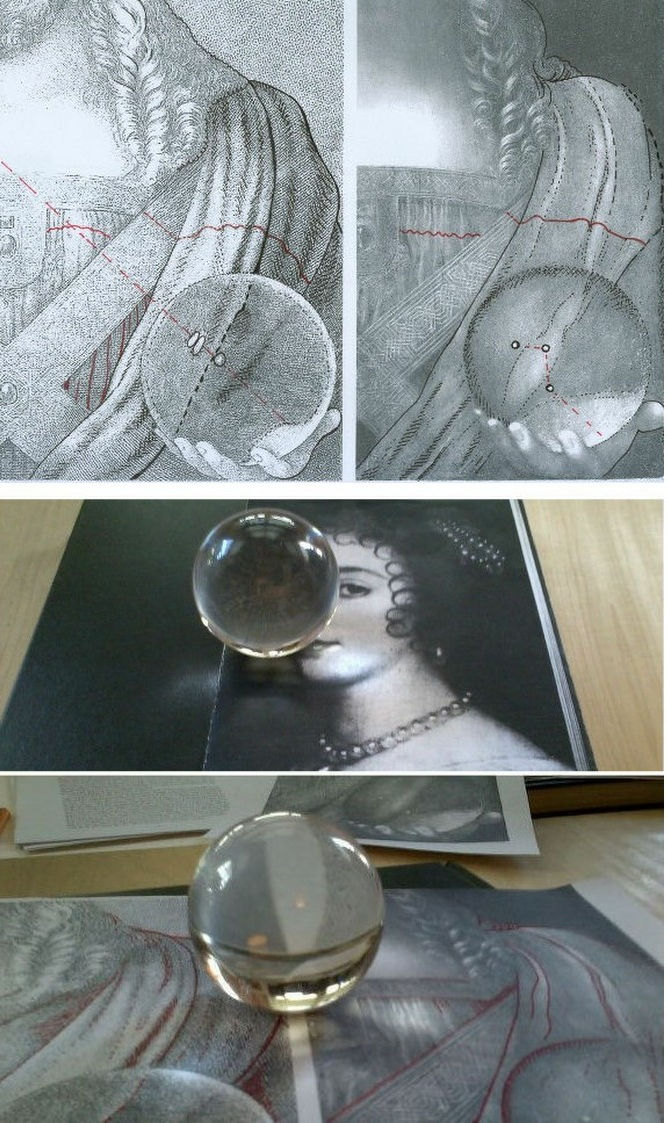

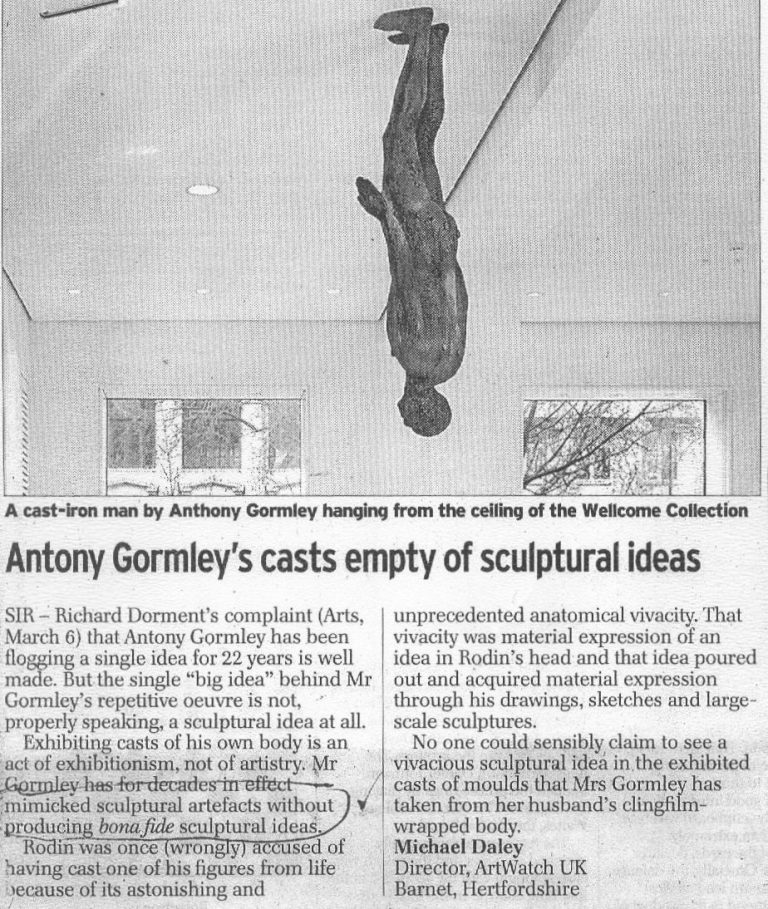

To Criticise a Critic

An examination of certain pre-emptive scholarly/art market establishment strikes against a pending book that rejects the Rubens ascription of the National Gallery’s contested Samson and Delilah.

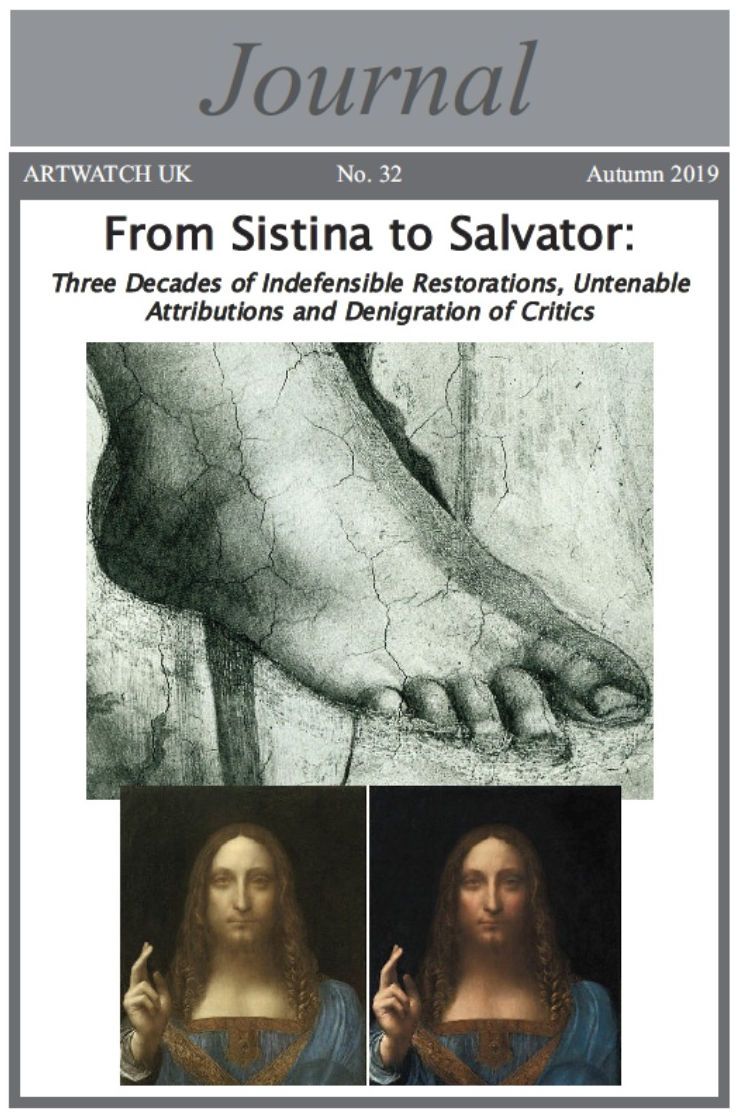

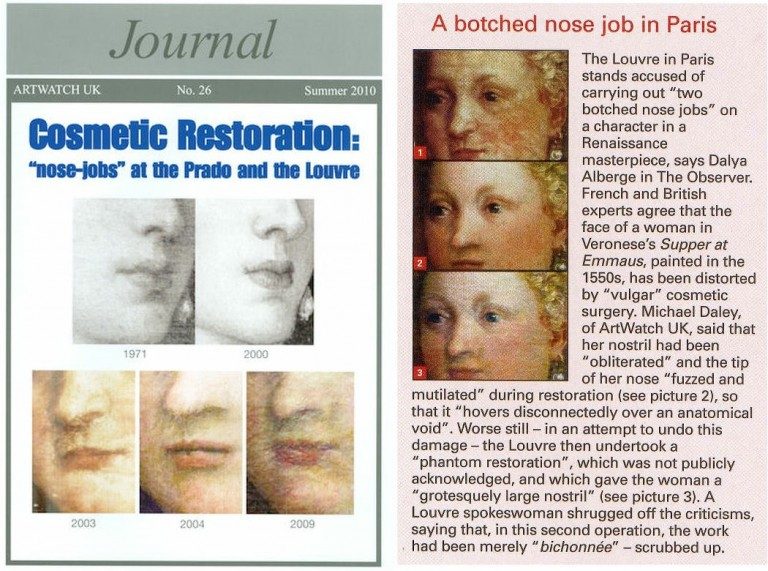

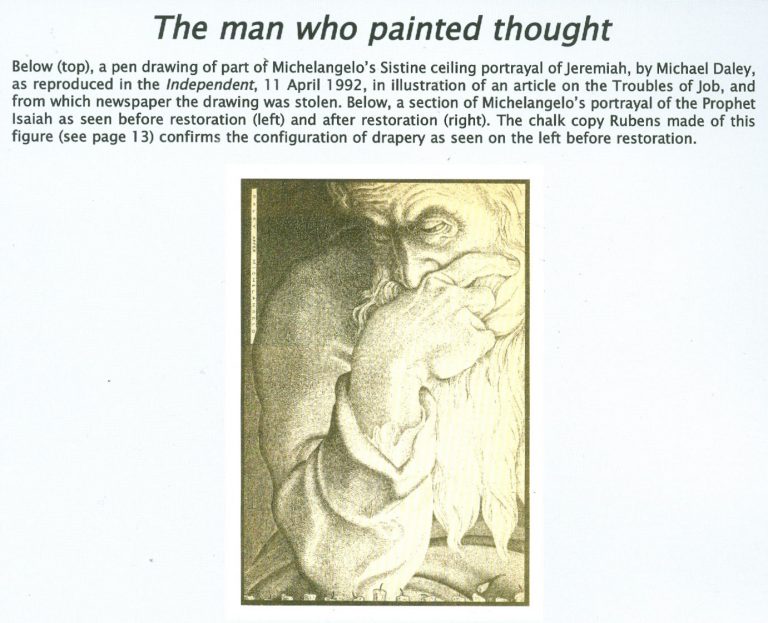

Michael Daley writes: Those who challenge art establishment scholars or institutions can suffer swift repudiation and denigration in lieu of frank and open debate, as I discovered when supporting Prof James Beck’s criticisms of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling restoration in the late 1980s. In the 1996 edition of the Beck/Daley Art Restoration – The Culture, The Business, And The Scandal, in a chapter headed “The Establishment Counter-attacks”, I noted:

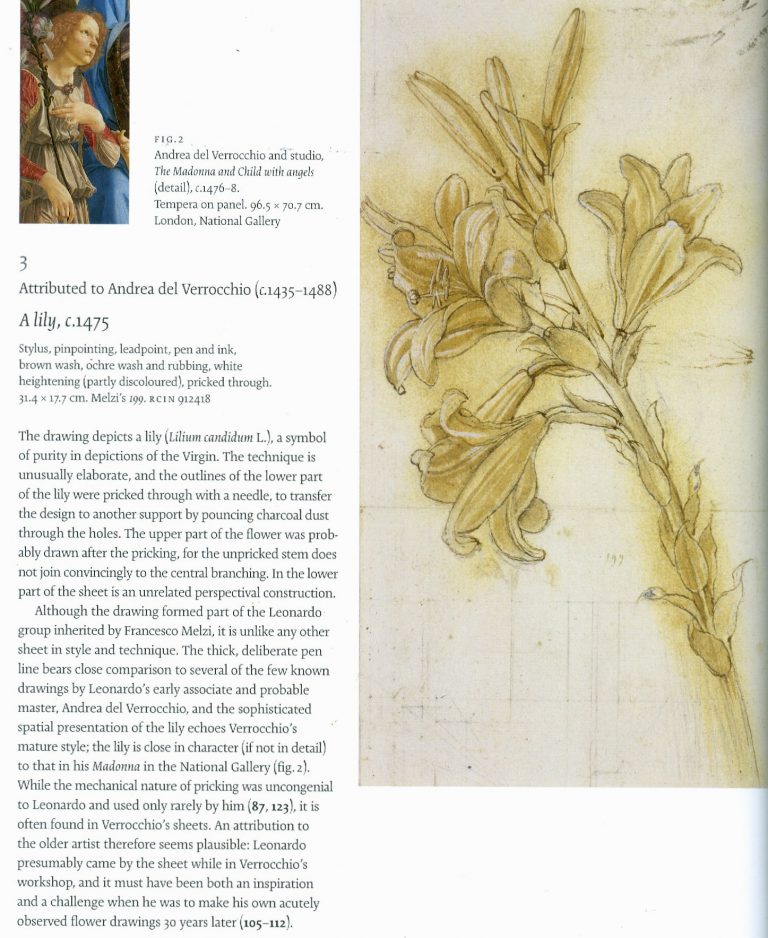

“When criticized in this area, institutions react institutionally, which is to say, by deploying self-protecting mechanisms common to all establishments. The best and most favoured response is no response, implying that the criticism is inconsequential and deserves to be ignored. In those instances where a response is unavoidable, it is thought best to be made by proxy… When a direct defence is necessary, its tone becomes all important. By tradition, the tone ranges from amused disdain, through supercilious dismissiveness to outright disparagement and attempts to discredit personal or professional credentials.”

It seems little has changed and that responses to the imminent arrival of Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s book on the National Gallery’s supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah (NG6461 – The Fake National Gallery Rubens) have run true to institutional templates. As a case in point, take this even-handed Artnet account: “Is This Rubens Real? Inside the ‘Samson and Delilah’ Debate” by Jo Lawson-Tancred.

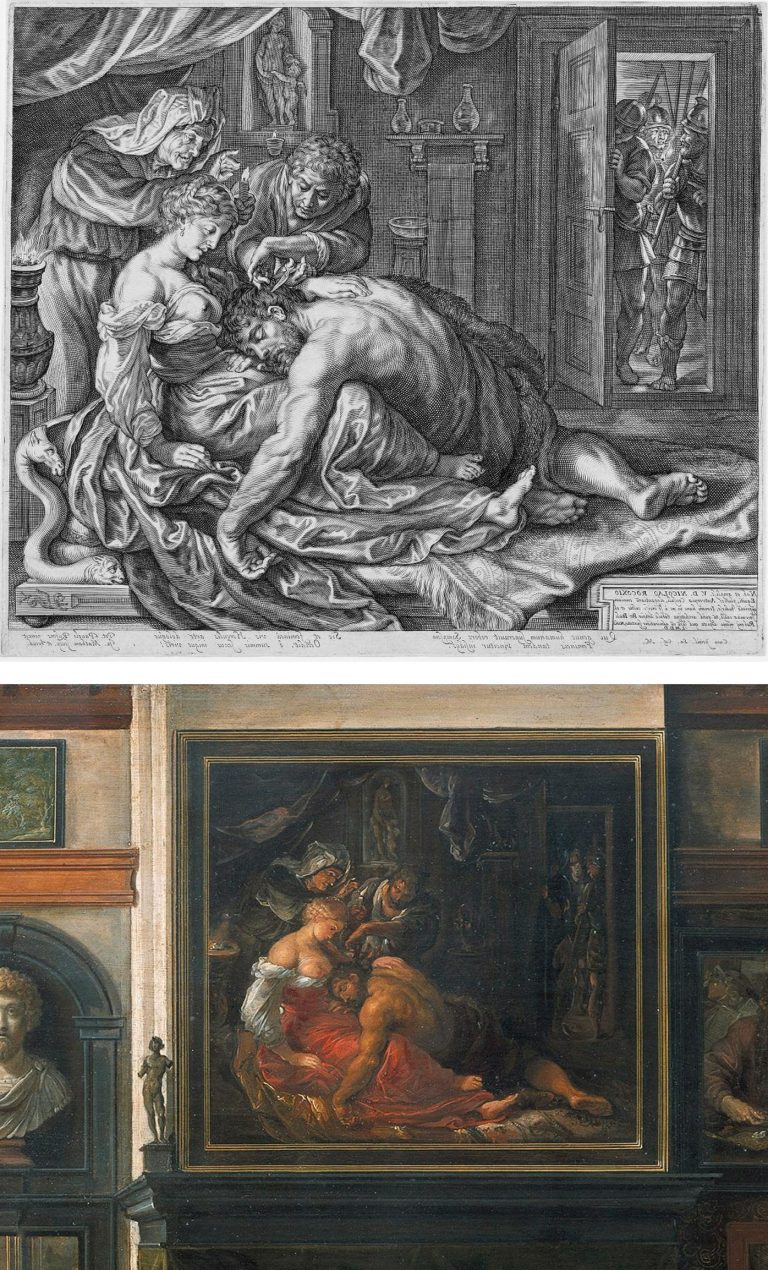

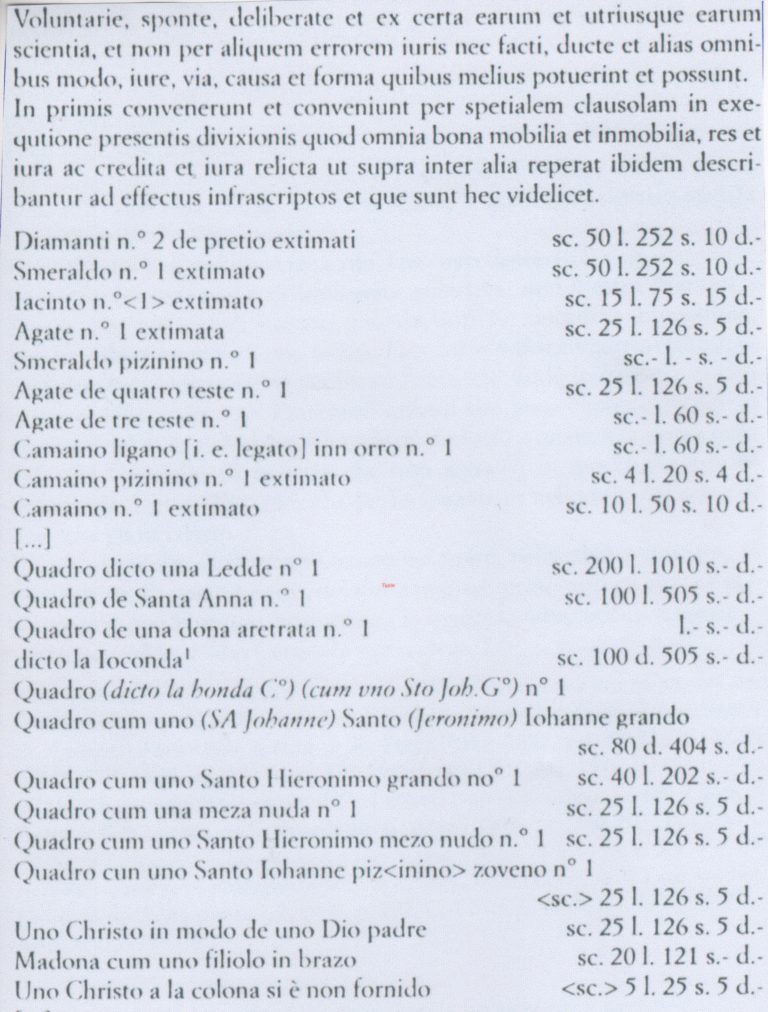

Lawson-Tancred reports an anonymous National Gallery spokesman’s claims that the picture “has long been accepted by Rubens scholars” and that the Gallery finds no cause to update its initial technical examination of the painting [as had been reported in its 1983 Technical Bulletin] and whose “findings remain valid.” The first part is true – Rubens scholars had so accepted the attribution. However, the insistence that the report on the then recently acquired, exhibited, and restored £2.53mn picture requires no updating disregards subsequent findings on this and other Rubens paintings.

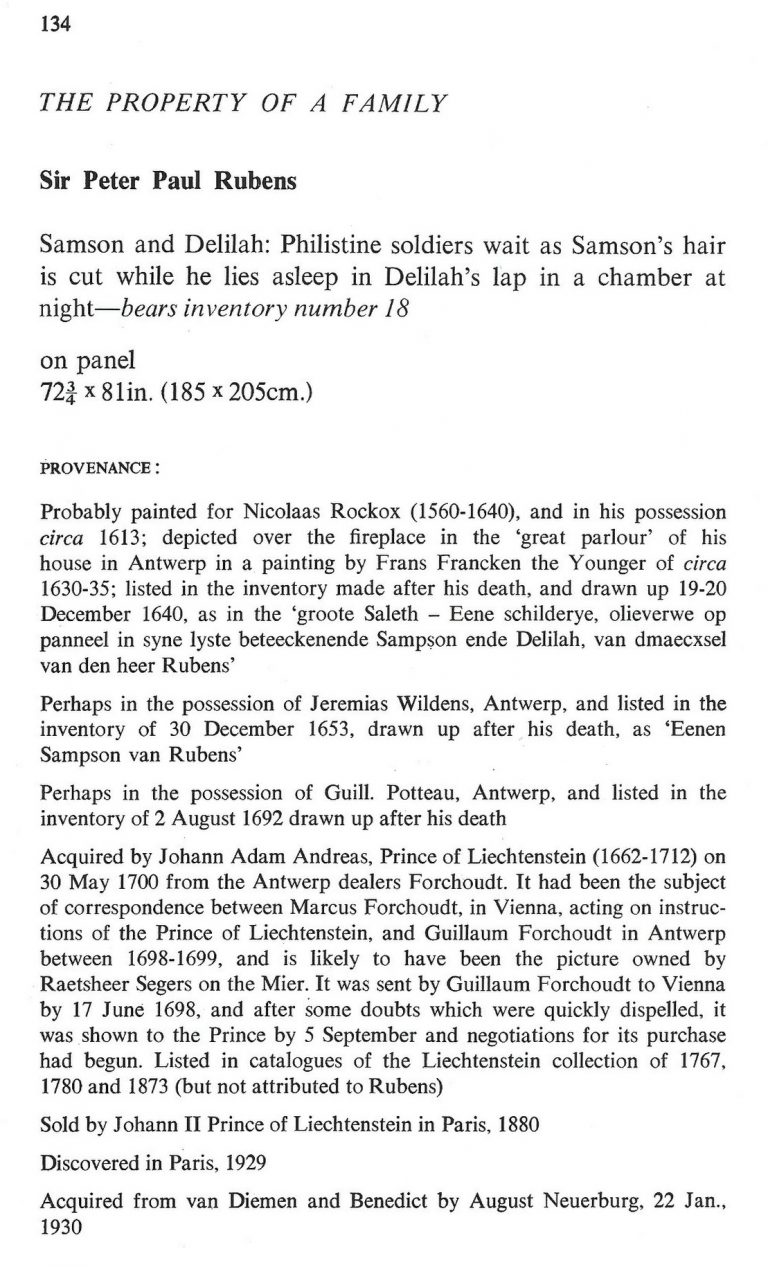

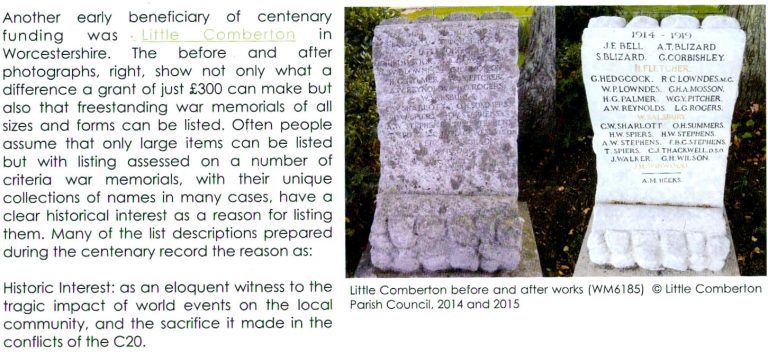

To be precise, the Gallery claimed in 1983: “At some time, probably during the present century, the panel was planed-down to a thickness of 3mm and subsequently glued onto a sheet of blockboard”. As Doxiadis and we have established the picture had emerged as a panel in 1929 – albeit ascribed to Honthorst. Crucially, it had remained a panel when sent to Christie’s, London, for sale in 1980 as an autograph Rubens – indeed it was precisely so described in Christie’s 1980 catalogue (see Fig. 1 below.) The picture’s physical state as a panel had been disclosed to Doxiadis by a Belgian banker who had wished to buy the picture for the Rockox House museum in 1977 and who again held it in Antwerp for its owner in 1980 before sending it on her behalf to Christie’s, London. Beyond any question, it was still an intact panel at that date.

WHERE’S THE BEEF?

Fig. 1, above: Christie’s 1980 sale catalogue entry on the Rubens-attributed Samson and Delilah panel. Note how the entry comprises a daisy-chain of “probablys” and “possiblys” – and also its parenthetical disclosure that, throughout its claimed long stay in the Liechtenstein Collection, this Samson and Delilah had not been judged a Rubens.

Given that we informed the National Gallery a quarter of a century ago of the picture’s confirmed physical status as a bowed and cradled panel in good shape in 1980, its 1983 technical account has long needed correction because the planing had not taken place before 1980, let alone in the 19th century. And yet, that manifestly unfounded suggestion that the planing might have occurred before the 20th century had been endorsed by Joyce Plesters, the Gallery’s Head of Science in the 1983 Technical Bulletin: “Unfortunately, as David Bomford has described, the back of the panel had been planed down to a thickness of only about 3mm and then the whole set into blockboard before the picture was acquired by the National Gallery…” In truth, it had not been set into the blockboard, but rather, as Bomford had correctly reported, and Doxiadis would later discover, it had been glued onto a blockboard sheet larger than itself and fitted into a new purpose made frame.

On the combined records of 1929 and 1980 that Doxiadis and we had uncovered – and as on Christie’s own published catalogue description – it followed that the planing could only have occurred after the picture was sold to the Gallery for its then world record Rubens price of £2.53million in 1980. Our concerns were compounded when informed (by the National Gallery’s then director, Neil MacGregor) that the Gallery had not followed its own procedure of preparing written curatorial and restoration reports on the picture’s desirability and condition to assist the trustees when they examined the picture (which had been loaned to the Gallery ahead of the sale – see below) to consider an authorisation of the purchase.

AN APPEAL TO AUTHORITY

In view of Doxiadis’s recently reported disclosures on the picture’s physical condition in 1980 (Dalya Alberge “Fresh doubt cast on authenticity of Rubens painting in the National Gallery,” ) Lawson-Tancred might have questioned or challenged the National Gallery’s abiding stance. Instead, she reported:

“…despite the marginal but adamant voices of researchers like Doxiadis, top scholars in the field support Samson and Delilah’s authenticity unequivocally. Chief among these is Nils Büttner, chairman of the Centrum Rubenianum in Antwerp, who is working on the Corpus Rubenianum, the definitive catalogue raisonné for the Flemish Baroque painter. He has previously described the doubts about Samson and Delilah’s provenance as “conspiracy theories.” However, Lawson-Tancred also noted that “Büttner [had] declined to comment on Doxiadis’s book”. While Büttner, presumably, has not yet read the unpublished book, his assertions received immediate support from players in the art trade:

“Büttner’s position is backed by his peers like Adam Busiakiewicz, a lecturer and consultant on Old Master paintings for Sotheby’s. He pointed out to the Telegraph that Doxiadis is not a scholar of the period and has mostly published on Greco-Roman antiquities previously. Though she ‘had a hunch the quality of the picture wasn’t good enough’, he said, ‘I think there are some misunderstandings about the painting.’”

On misunderstandings, Busiakiewicz (who seems also to be employed by the art market “sleeper-hunter” and former Philip Mould assistant, Bendor Grosvenor, on the latter’s “Art History News” blog site), paraded just such in his reported burst of professional condescension to Doxiadis:

“Busiakiewicz explained that a comparison between Samson and Delilah and other paintings by Rubens are complicated, especially when they were made decades apart. ‘He’s an artist that changed his style throughout his career,’ he said. ‘Art historians who specialize in paintings like Rubens’ can track these changes.’ It is for this reason that the National Gallery painting has been connected to Rubens’s interest in the work of Caravaggio and other Renaissance masters whose work he had, at that time, recently encountered while traveling in Italy.”

While it is widely known that Rubens underwent changes of manner in his later paintings, Busiakiewicz failed to acknowledge (or appreciate?) that Doxiadis, we, and other critics of the attribution, such as Dr Kasia Pisarek, have for decades pointed out and demonstrated that the Samson and Delilah is glaringly unlike the bona fide Rubens paintings made precisely in that brief period when the artist had just returned from Italy.

Specifically, we had reminded readers in November 2021 that:

“In a pioneering 1992 report, the scholar/painter Euphrosyne Doxiadis and the painters Stephen Harvey and Siân Hopkinson, conducted a focussed survey of six Rubens paintings of 1609 and 1610 and demonstrated that “All these display a consistency and quality of style which is not shared by the Samson and Delilah”. That report – “Delilah cut off Samson’s hair, but who cut off his toes? The case against the National Gallery’s ‘Rubens’ Samson and Delilah” – was placed in the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah dossiers and is published on the dedicated In Rubens Name website.”

WHITHER THE PANEL’S BACK

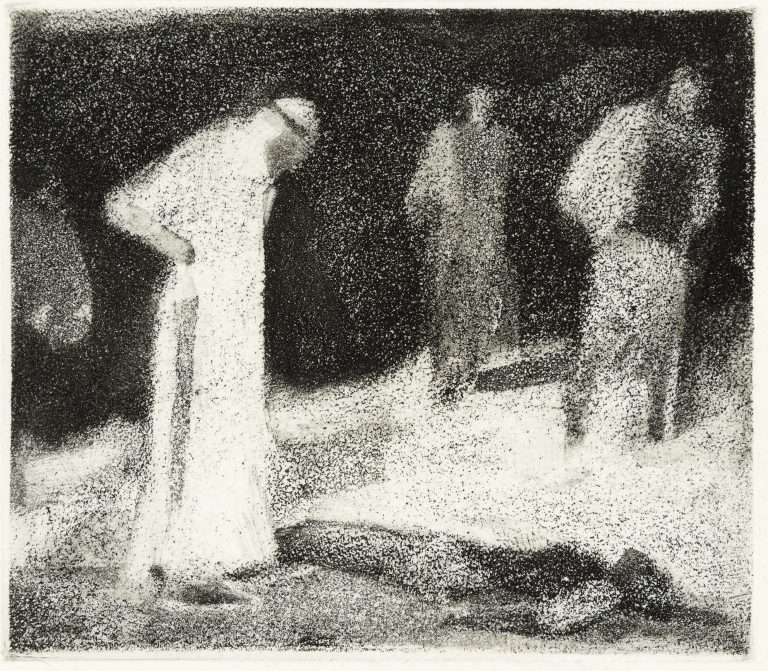

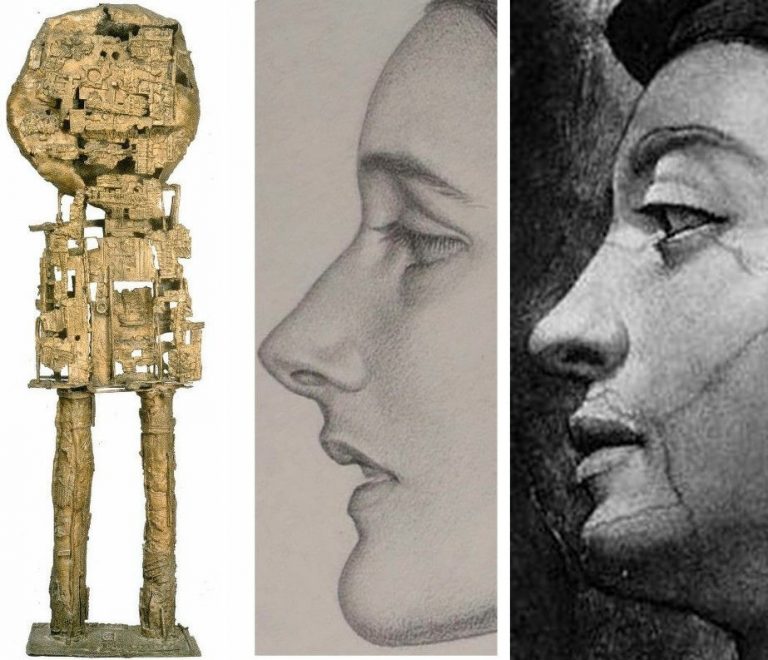

Above, Fig. 2: The covers of two ArtWatch UK journals given over to detailed accounts of the Samson and Delilah problems and shortcomings.

In issue 21 Kasia Pisarek wrote: “The Corpus Rubenianum project is based on the archive left by the late Dr Ludwig Burchard. Should it perhaps follow it less closely? Dr Burchard was an active Rubens attributionist in Berlin before the Second World War and in London afterwards. Several paintings formerly attributed to Rubens’s school or studio or even to another artist (such as Samson and Delilah), were reinstated by Burchard as by the master. I traced many of his attributions – he was not infallible in his judgement and changed his mind. Surprisingly, over sixty pictures* attributed to Rubens were later downgraded (in Corpus Rubenianum) to studio works, copies or imitations.” Pisarek adds: “they were, however, mostly portraits of small or medium dimensions.”

If a major work like Samson and Delilah might be considered something of an exception, Doxiadis supplies a possible explanation – Burchard was a relative of one of the owners of the dealing firm that had brought the supposed Honthorst to the marketplace.

*On the subsequent completion of her PhD thesis – Rubens and Connoisseurship: Problems of Attribution and Rediscovery in British and American Collections – Dr Pisarek remarked: “I traced many paintings attributed by Ludwig Burchard… At least seventy-five works he certified authentic were subsequently downgraded to studio works, copies, and imitations in the volumes of the Corpus Rubenianum, and the list is not complete… can we trust Burchard’s old rediscovery and attribution of the London Samson and Delilah?)

In issue No.11 we had written: “On December 17th 1998 Dr Jaffe [David Jaffé, then Senior Curator at the National Gallery] writes: ‘Sotheby’s auctioned Rubens Deluge as ‘oil on oak panel’ when, in fact, it was on a marouflaged panel’.” But how is this known? It was so, Jaffé discloses, “according to the condition report made in 1996-97 when the picture was loaned the National Gallery…” But no such condition report was made when the Samson and Delilah was loaned to the National Gallery by Christies ahead of the sale. That condition report on the Deluge had been prepared by the National Gallery’s timber specialist restorer, Anthony Reeve. As recently as 1982 Reeve had reported in the National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin (see Fig. 7) that the Samson and Delilah was “one of only three well-made straightforward Rubens panels in the collection” – which panels, he elaborated, required stable humidity because otherwise “The effect of wood shrinkage on the exposed backs of the panel…is for the front to become convex, and perhaps slightly corrugated”. Had the Samson and Delilah been planed-down and glued to blockboard at that date there would have been no possibility of its back being subjected to environmental hazards. It might be thought inconceivable that the National Gallery should have lost recollection of Reeve’s testimony by the following year and when writing in the same publication. As the National Gallery’s senior picture restorer Reeve was held after his death by Neil MacGregor to be the “supreme practitioner of his generation.”

There are yet further confirmations of the panel’s still-then exposed back. Doxiadis had obtained a Belgian condition report on the Samson and Delilah which began: “On arrival on 4 March 1980, about 14.30 hours the painting mentioned above (panel, 185 x 205 cms) was in good shape…” Doxiadis’s account squared with testimony supplied to ArtWatch by the art critic Brian Sewell (an ex-Christie’s man who took pride in having there identified an oil sketch as the modello for the Rubens Samson and Delilah), namely: that the panel had not been mounted on blockboard; that the back of the panel had been painted in a darkish matt colour and was criss-crossed with supporting bars of wood; that because Christie’s customary stencil number was made with dark paint it had been superimposed over a patch of white paint Christie’s had applied to the panel’s back.

Presumably Busiakiewicz has yet to access the 1992 Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson report. For the record, the document I found in the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah dossiers was a copy of the picture’s 1929 certificate of authenticity written by the great but subsequently discredited Rubens specialist Ludwig Burchard who had observed: “The picture is in a remarkably good state of preservation with even the back of the panel in its original condition”.

A CRITICAL FORMATION ASSEMBLES…

Where Busiakiewicz patronises Doxiadis on an allegedly insufficient familiarity with the Samson and Delilah literature, Nils Büttner has been joined in that disparagement by Bert Watteeuw, the director of the Antwerp Rubens House. As John Smith reports in the EuroWeekly:

“The latest suggestion that this is a 20th-century copy comes from Greek art historian Euphrosyne Doxiadis in her new book The Fake Rubens although this accusation finds little support from one of Belgium’s top Rubens experts Bert Watteeuw. Not only does he pour scorn on her status as a genuine expert, suggesting that anyone of any standard would have already checked with his Antwerp Rubens House and other specialist houses about the painting. In addition, he also said: ‘the provenance of this painting is very well known throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. A provenance that can be trusted is always crucial’…”

This implied claim of a trustworthy Rubens provenance was a brazen sleight of hand: what John Smith was not to know is that, as shown above, the provenance concerned at no point confirmed the painting as being by Rubens’ hand. Being thus kept in the dark, poor Smith could only but conclude: “Whilst the National Gallery has kept a dignified silence on the matter of the painting, it is no doubt delighted that one of the great Rubens scholars has come out publicly to dismiss the fake claim by Doxiadis which Watteeuw considers is purely invented to promote her book.”

Delighted as the National Gallery might be and while its Trappist silence might do yet further service as an institutionally imperative damage limitation exercise, it remains an untenable stance because, as one very distinguished former National Gallery trustee at the time of the Samson and Delilah purchase told Doxiadis, “the truth will come out – it always does”. As for Watteeuw, for a Rubens scholar at the supposed top of his professional tree to resort to professionally unfounded claims and personally directed abuse is as counterproductive as it is contemptible.

Moreover, in this regard, Watteeuw might be considered a serial offender: when apprised of negative AI findings on the Samson and Delilah panel he told another journalist, Colin Clapson (‘Fake Rubens in London’s National Gallery? This painting is genuine” counters Rubens House director Bert Watteeuw”) that Doxiadis’s soon-to-be-published book is “Complete nonsense and not based on facts. To begin with, I do not know this art historian and that is a sign. Most researchers on Rubens have passed by our Rubens House and the Rubenianium, the Rubens Library, in the search of sources and information,’ says Bert Watteeuw, the director of the Antwerp Rubens House. ‘Moreover, Doxiadis has an agenda of her own: to promote her book and that seems to be working well. In such cases conspiracies à la Dan Brown are more interesting than science.’ Whilst attacking its critic, Watteeuw gifts the National Gallery a clean bill of scholarly probity on its protracted silence: “‘The painting ‘Samson and Delilah’ in London is a genuine Rubens, a masterpiece. It is logical that the National Gallery does not want to comment or discuss its authenticity,’ he says.”

DISALLOWED TESTIMONY

In view of the above it might seem that among Rubens establishment scholars generally and for the National Gallery itself, nothing can be allowed to count as evidence against the challenged panel’s Rubens ascription. For example, in 2021, the brushwork of the Samson and Delilah was compared with that found in no fewer than 148 uncontested Rubens paintings. As Dalya Alberge noted in the Guardian (“Was famed Samson and Delilah really painted by Rubens? No, says AI”), “Its report concludes: ‘The AI System evaluates Samson and Delilah not to be an original artwork by Rubens with a probability of 91.78%.’ In contrast, the scientists’ analysis of another National Gallery Rubens – A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning – came out with a probability of 98.76% in favour of the artist.”

Such disinterested testimony is dismissed by the affronted – and perhaps professionally discomfited – scholarly grandees: “Watteeuw also dismisses AI research dating from a few years ago. ‘When that appeared, we engaged in extensive behind-the-scenes dialogue with that Swiss firm that had carried it out. AI can only work if you train it with an artist’s entire oeuvre. That was not the case at that time.’” (Watteeuw was here echoing Bendor Grosvenor’s mis-characterisation of the Swiss firm: “It is simply not possible to determine whether a painting is by Rubens by relying on poor quality images [sic] of not much more than half of his oeuvre…”) First, there is once again, as with Doxiadis, an implicit professional slur on the firm in question. Second, there is yet further evidence that logic is underemployed by many art establishment players: if, given the very great distinctiveness of Rubens’ style and painterly applications, you can find no visual correspondences when comparing the Samson and Delilah’s brushwork with a single one of 148 secure Rubens paintings, why would you be likely to find such correspondences in another batch of equally secure Rubens paintings? At this point, calling for yet more extensive AI tests on a vast oeuvre – and one with ever-shifting boundaries – is procrastination, the obliging sister of obdurate institutional silence.

CAN’T SEE – OR WON’T SEE?

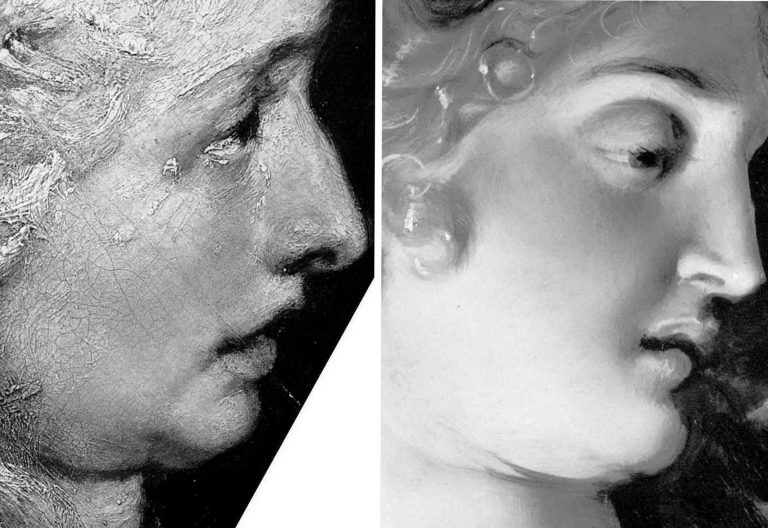

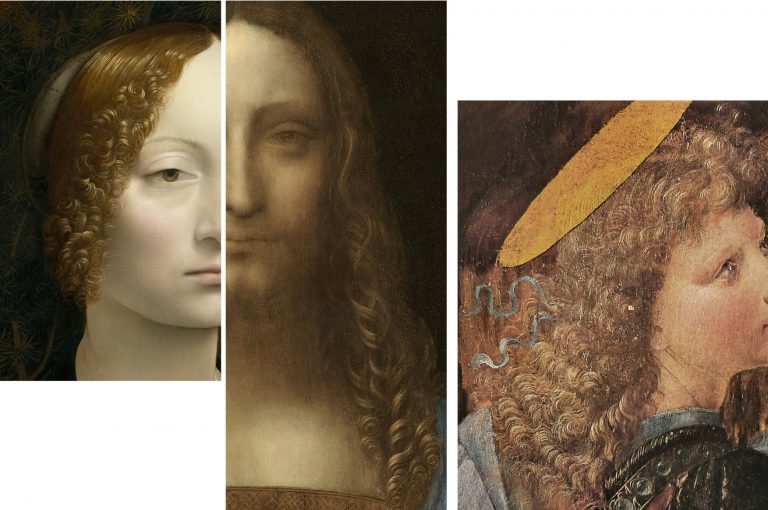

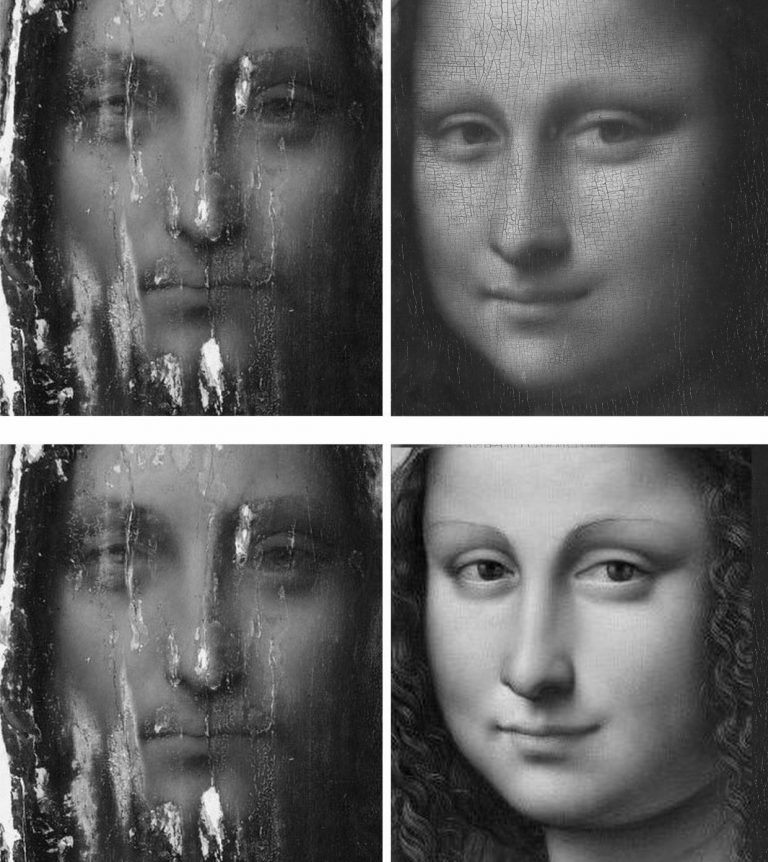

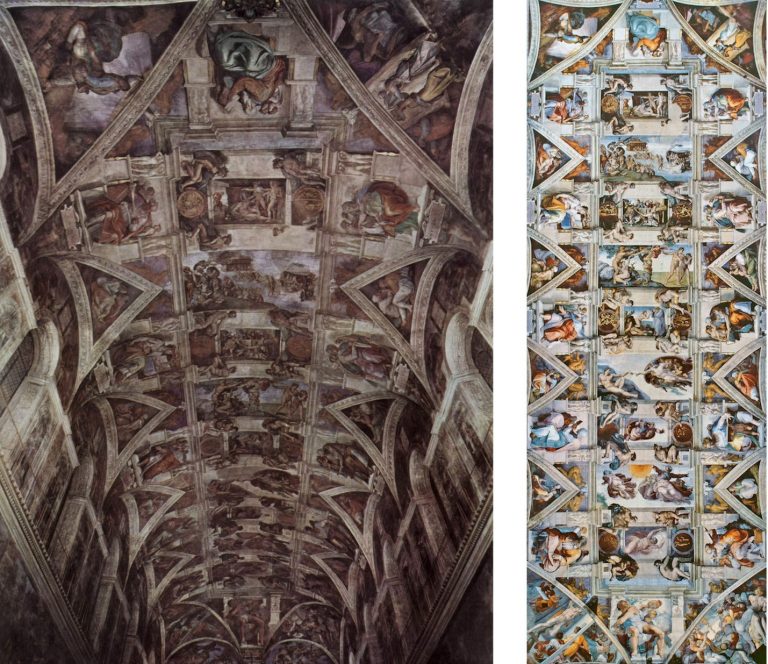

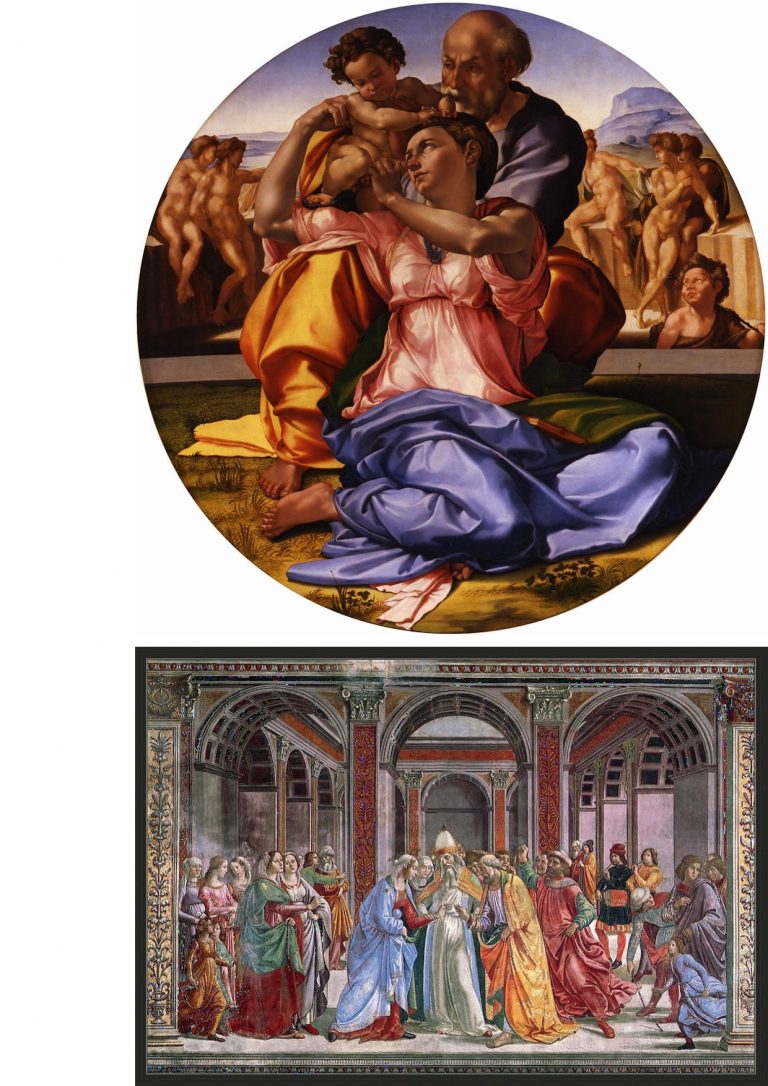

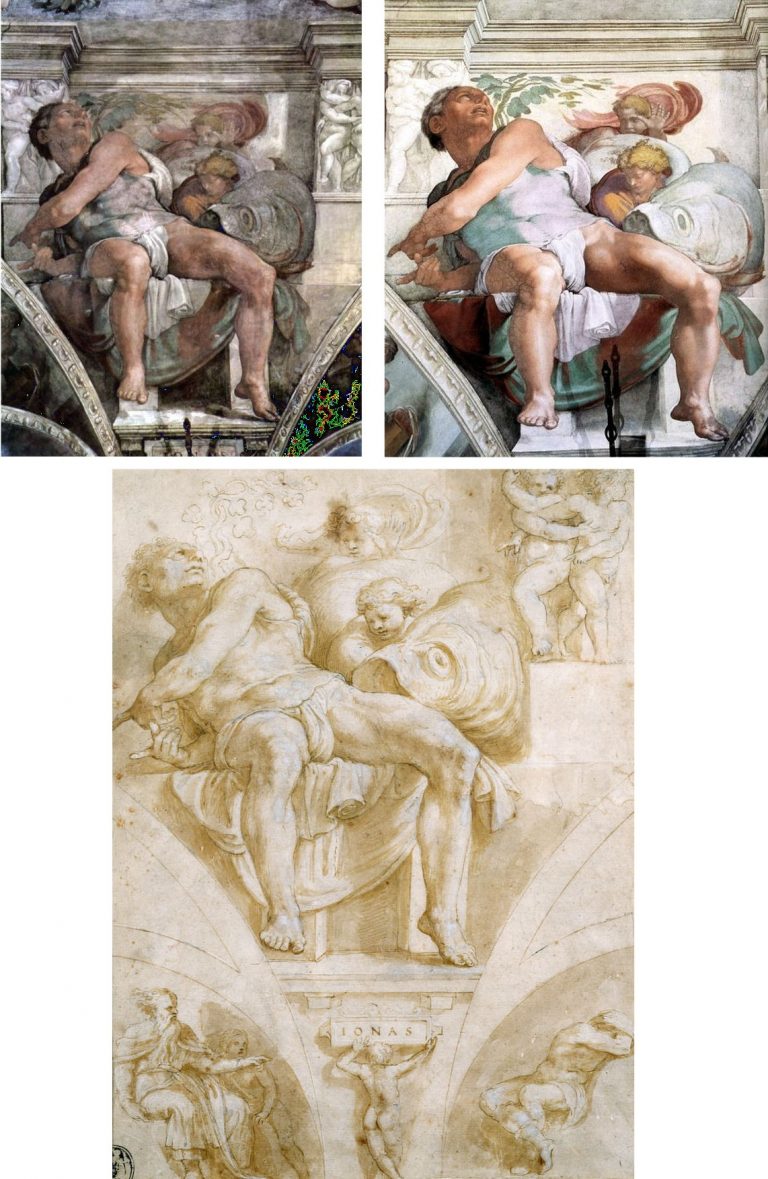

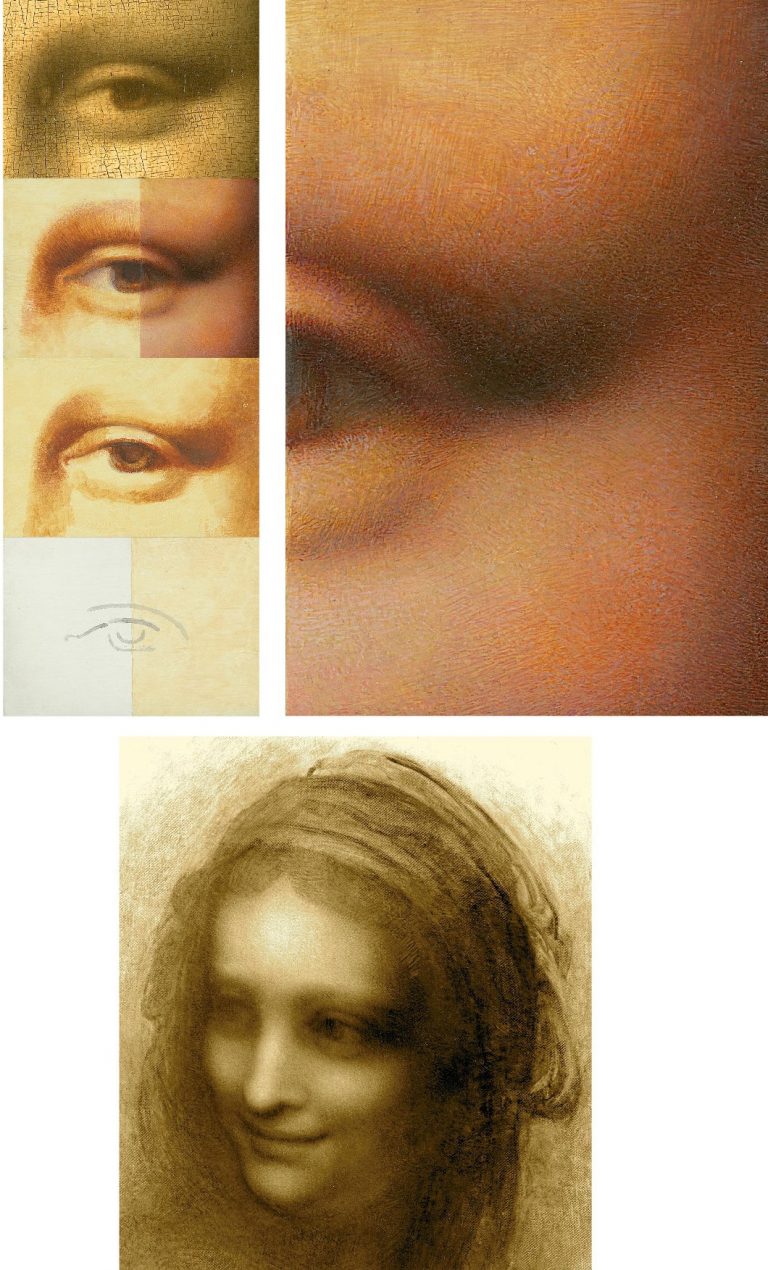

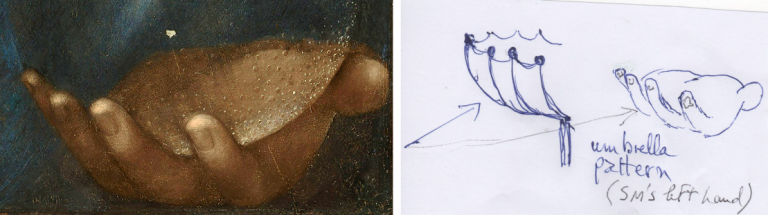

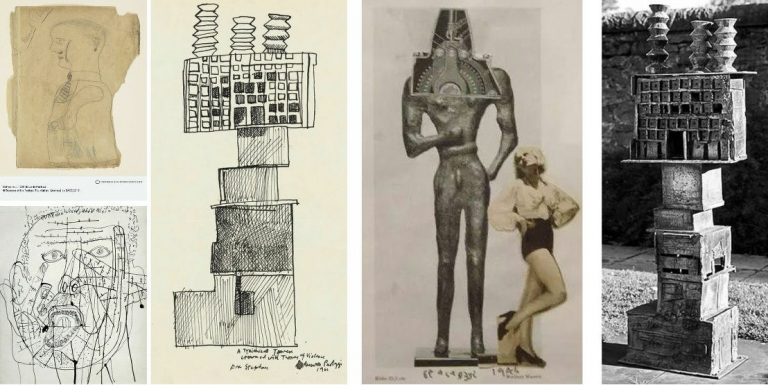

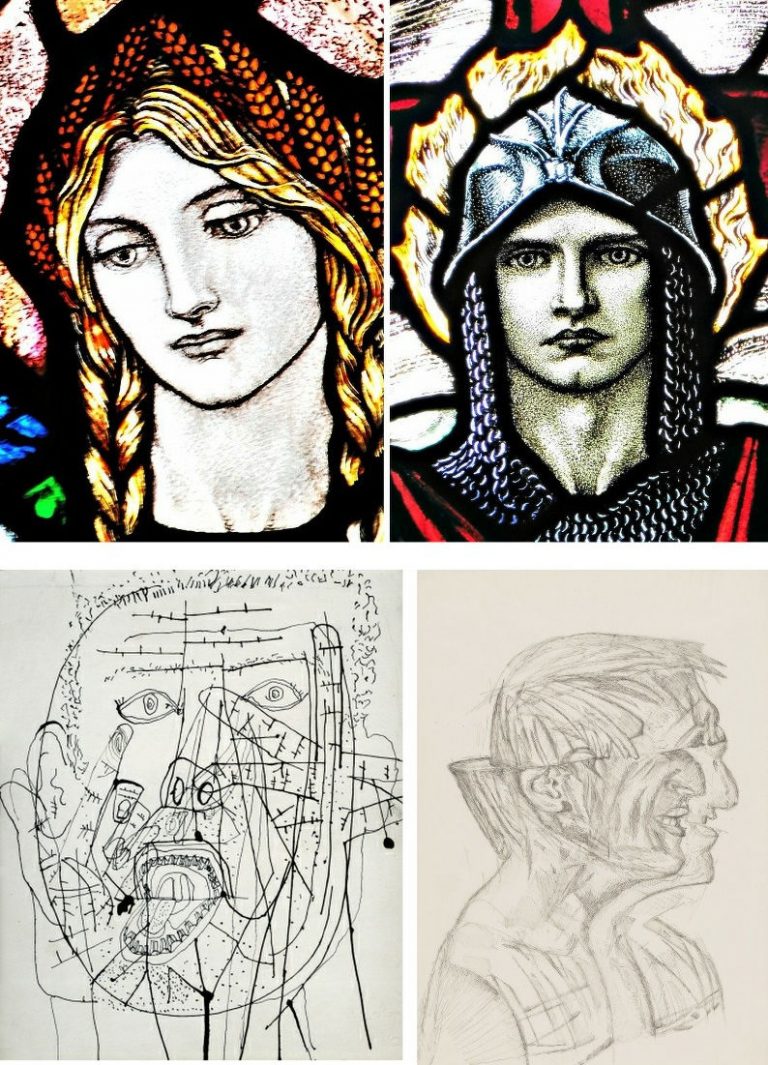

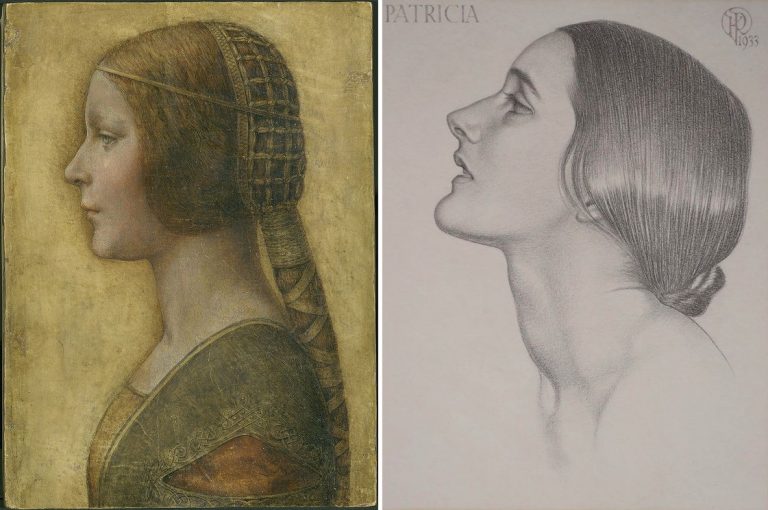

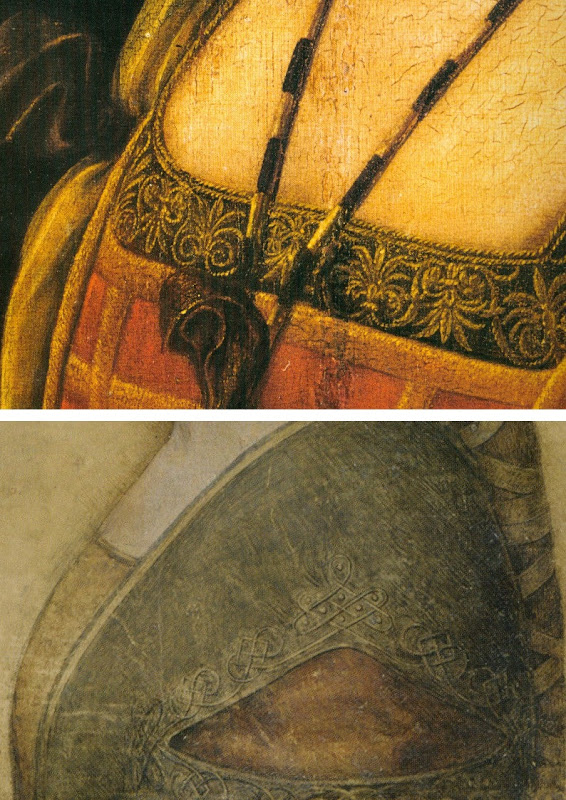

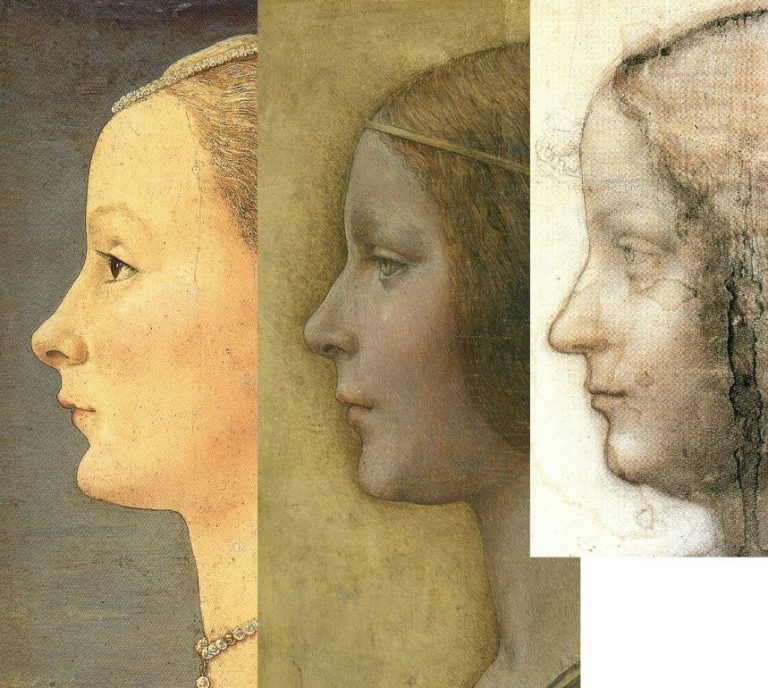

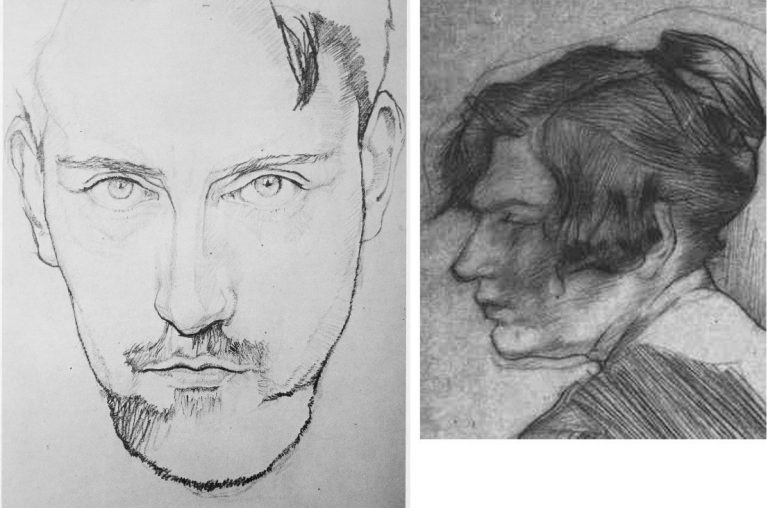

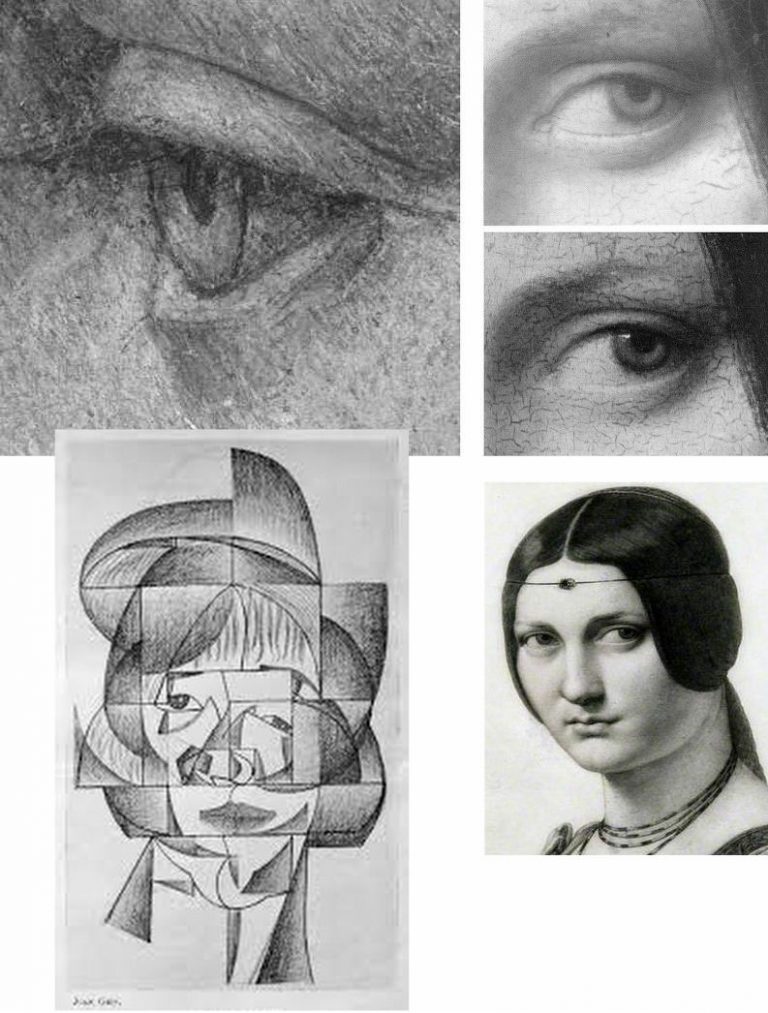

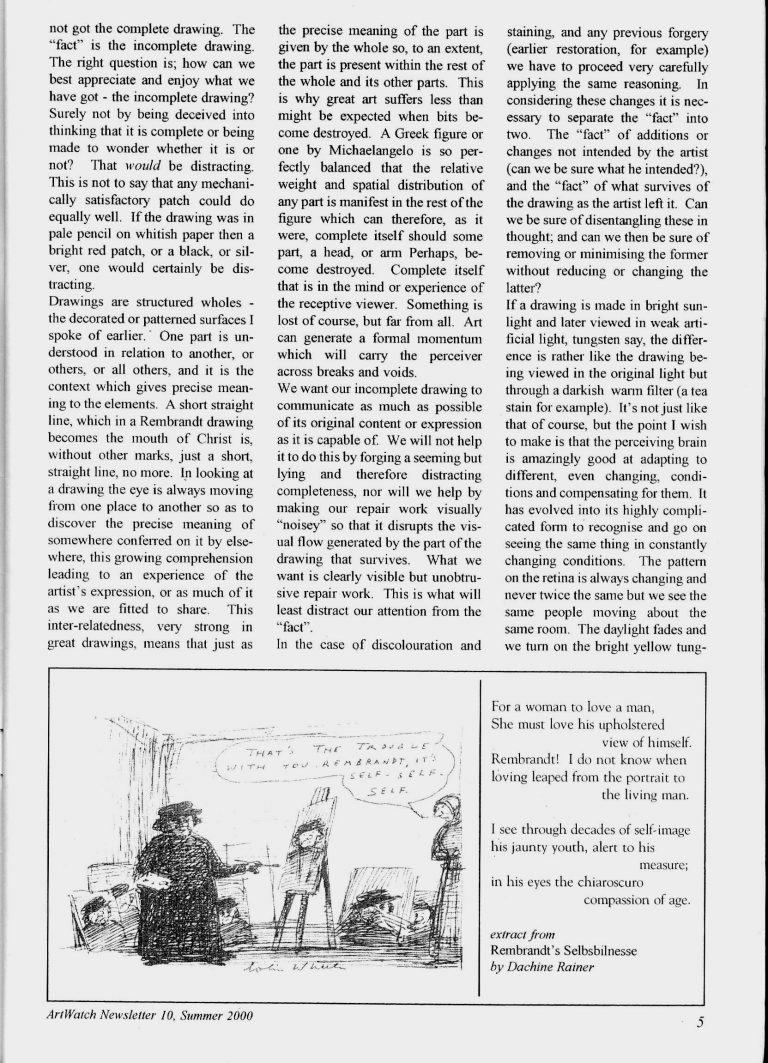

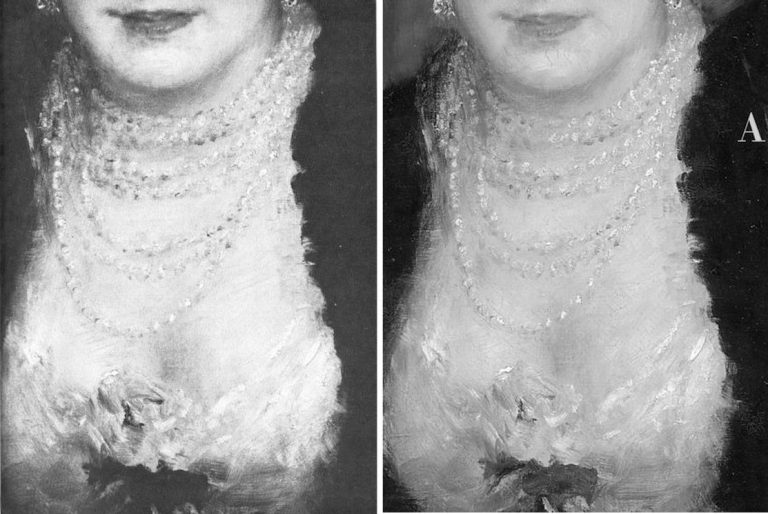

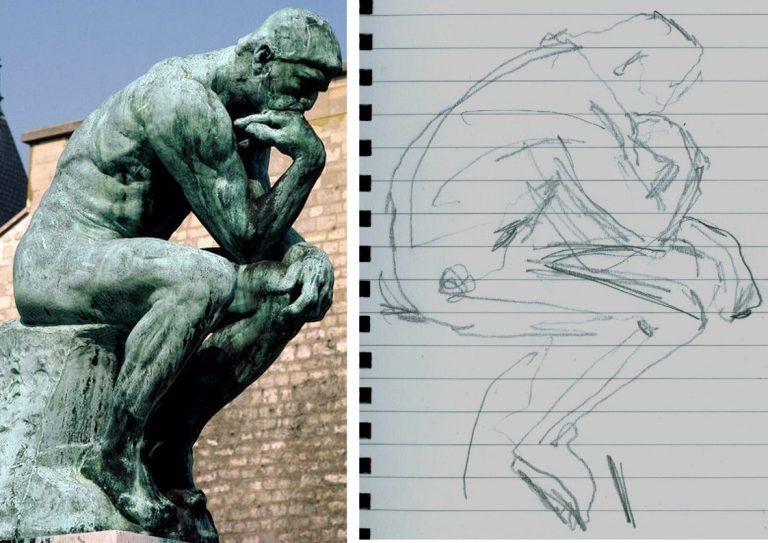

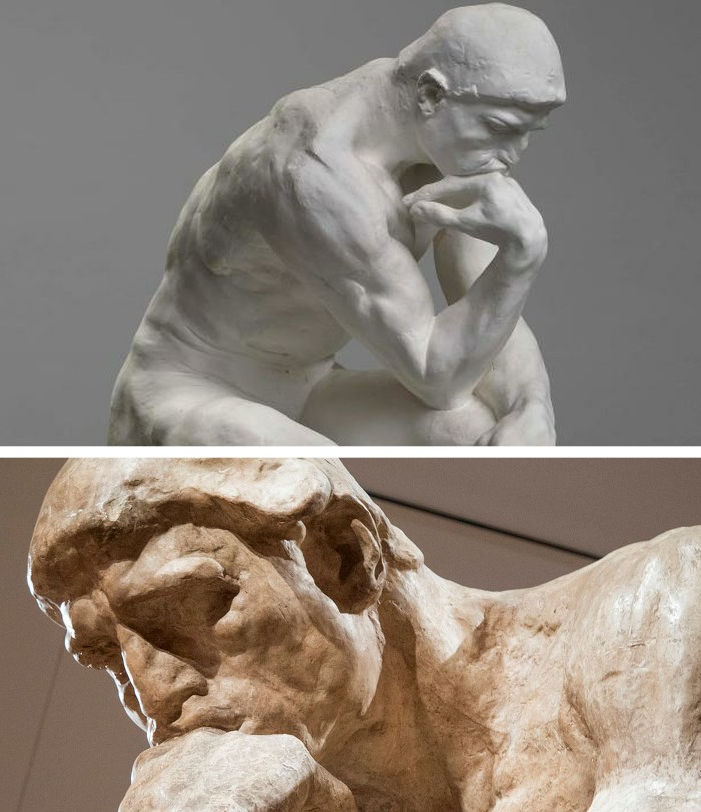

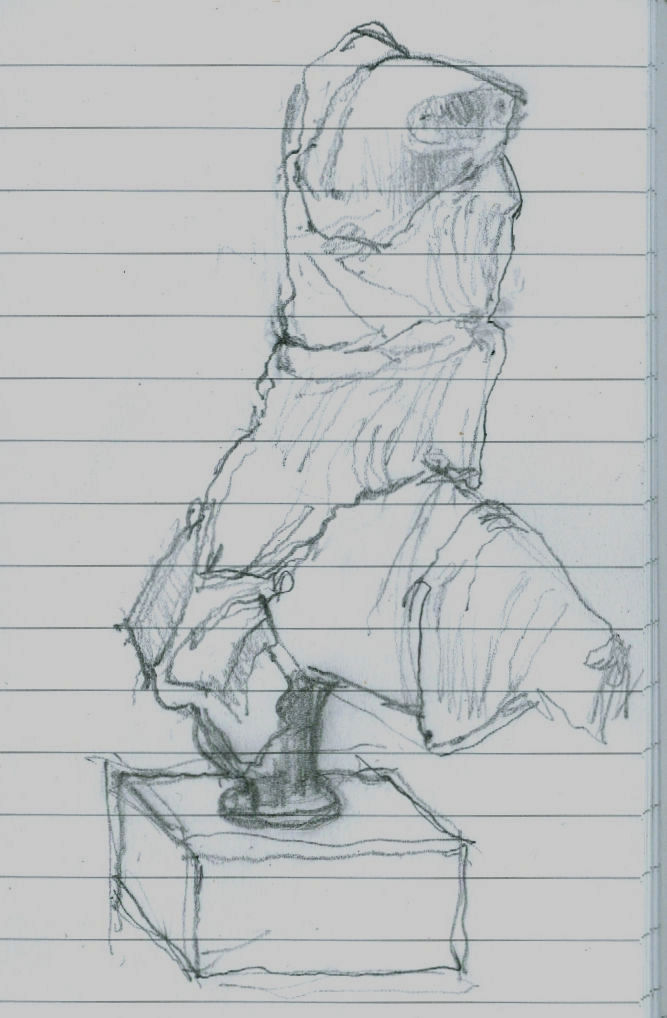

Professor James Beck once remarked that too many of his peers “look with their ears” and that it is “only the artists who can see things clearly”. It so happens that all the principal critics of the Samson and Delilah picture – Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson/Daley/Pisarek – happen to have trained as artists, as Beck himself had done. Doxiadis noticed what no Rubens scholar, so far as we know, had noticed: that while Rubens painted with round brushes, the shadowy author of the Samson and Delilah had deployed flat brushes.

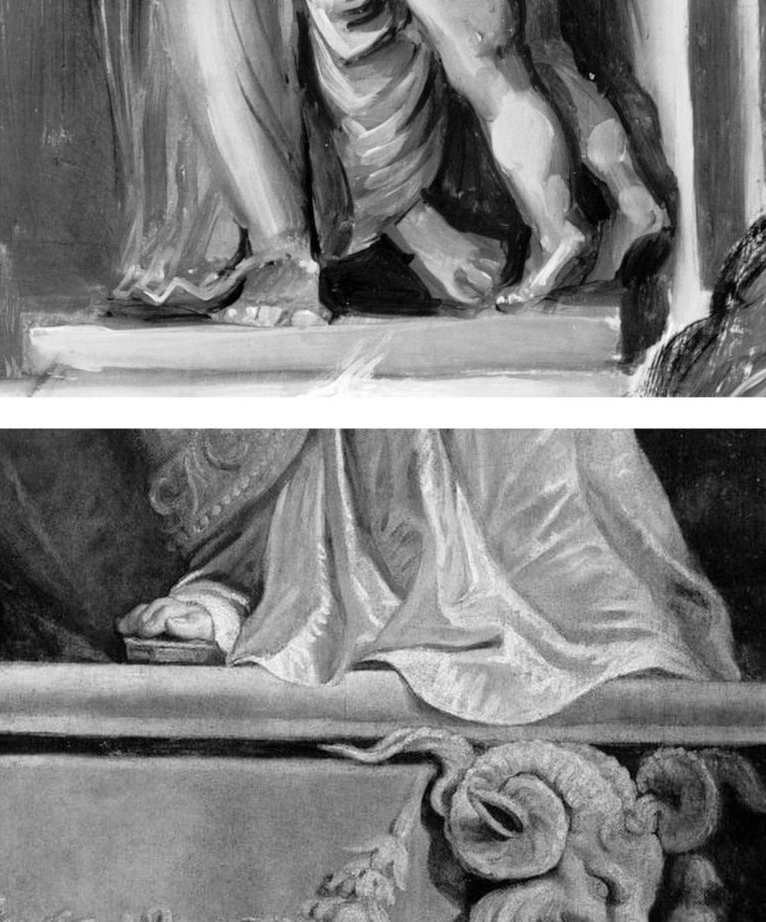

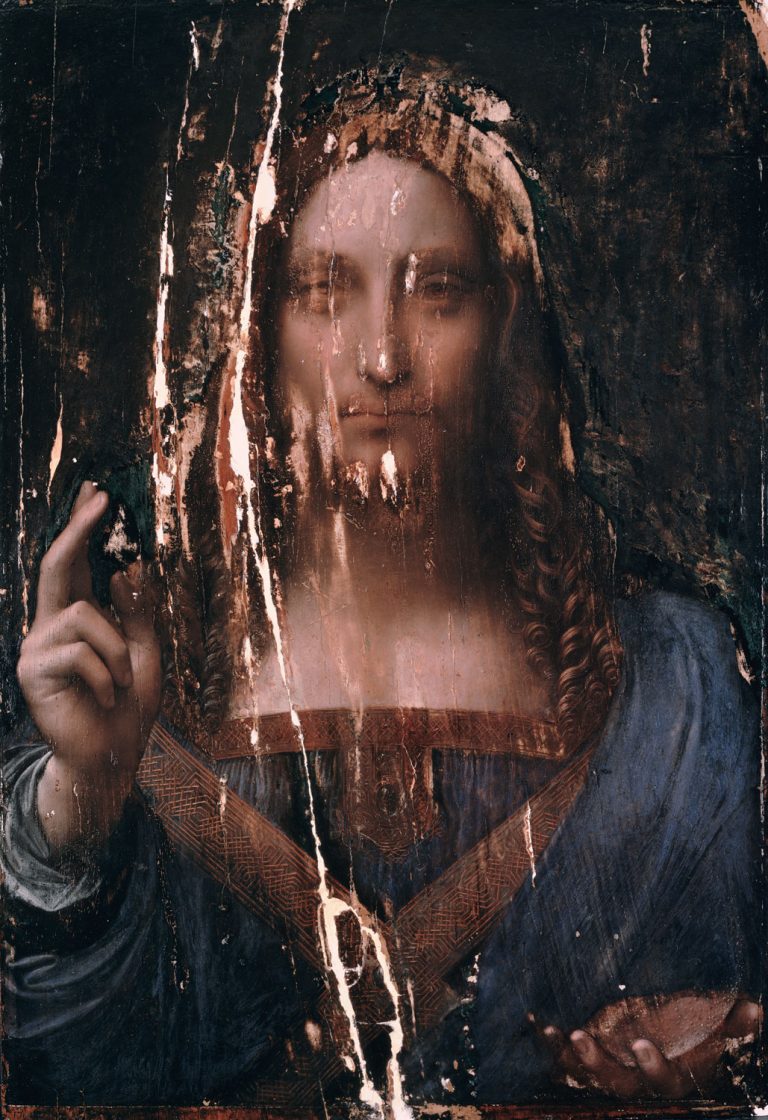

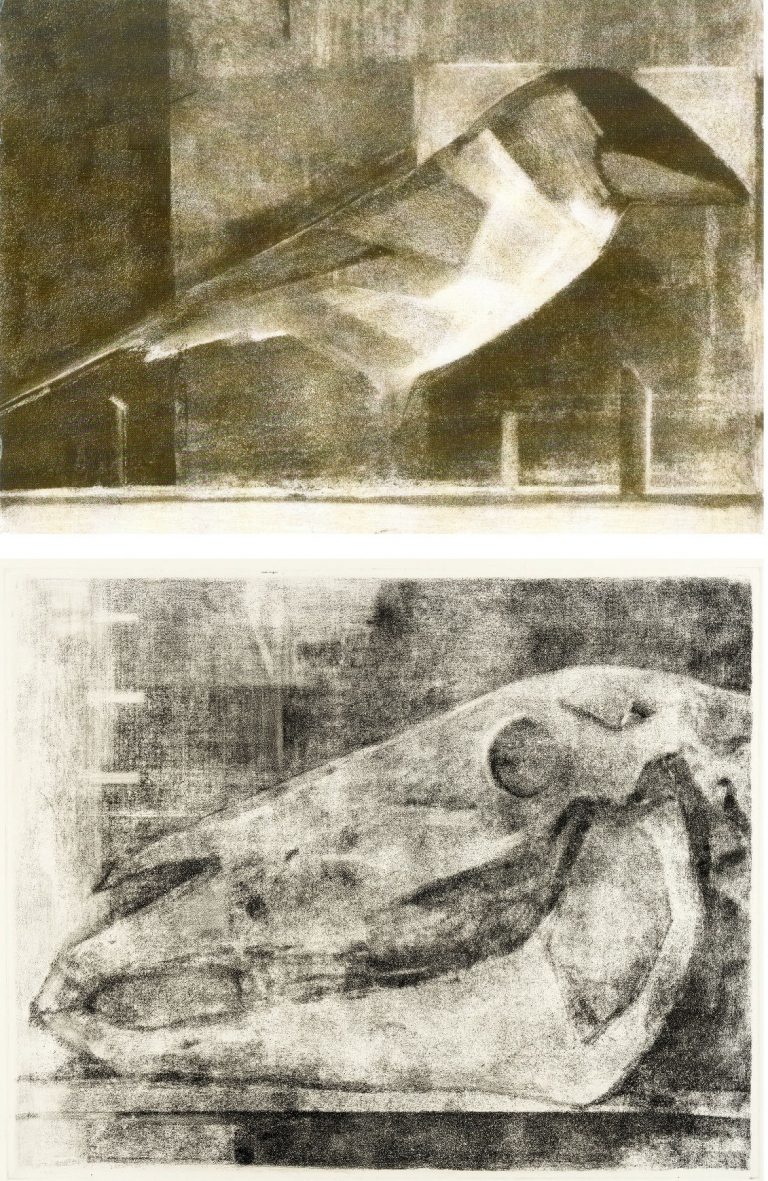

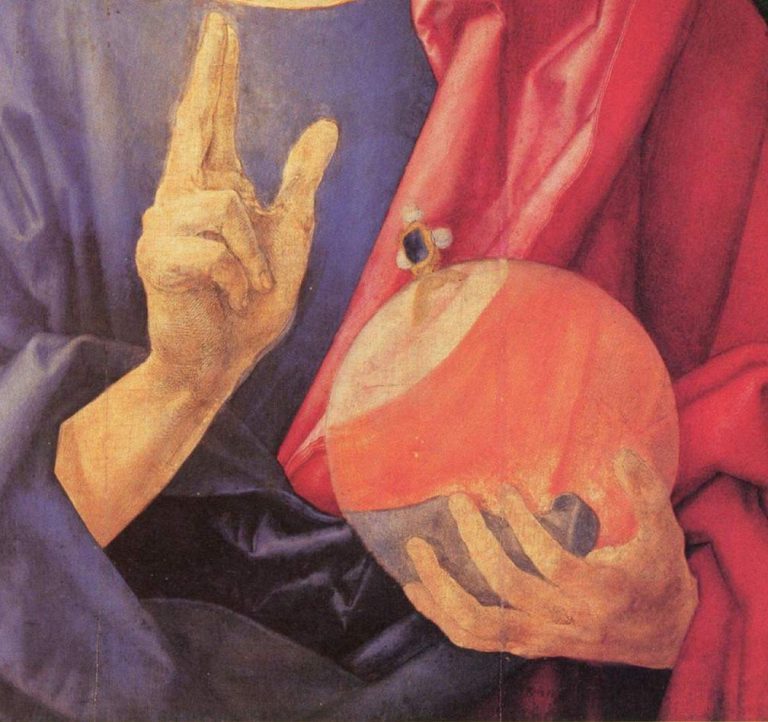

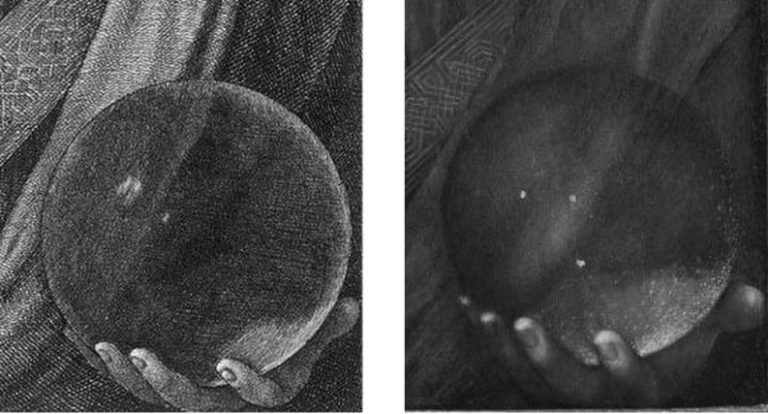

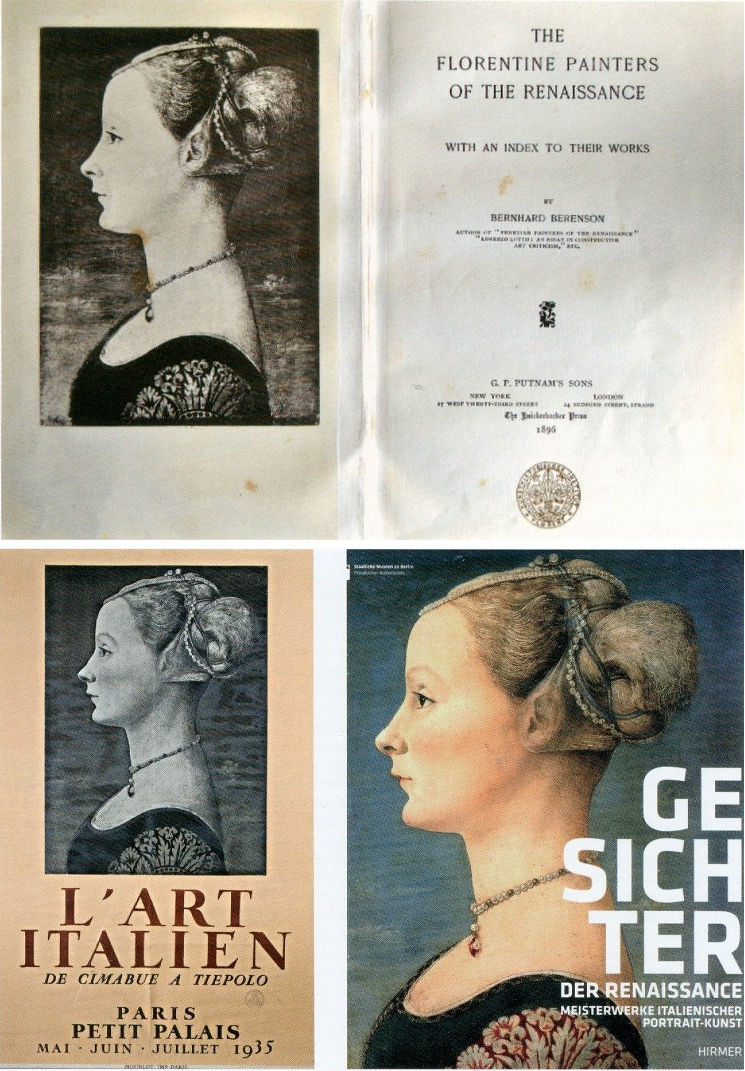

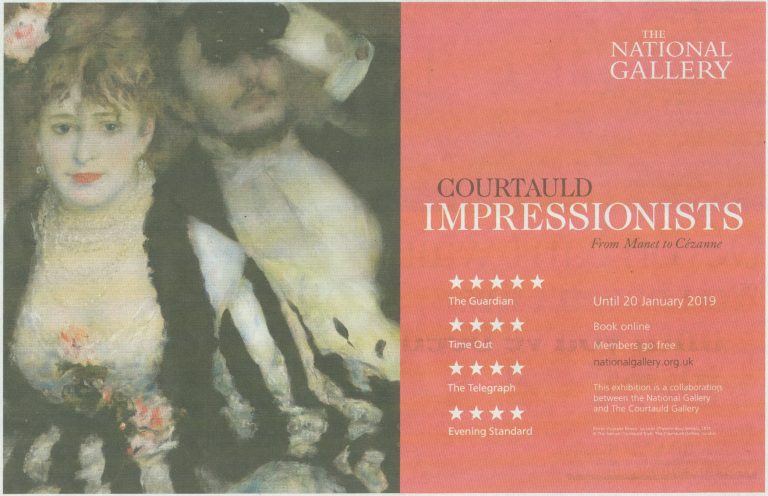

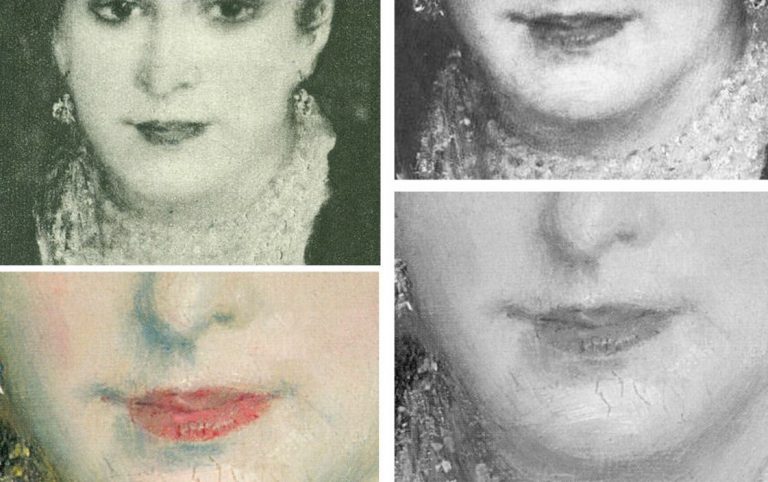

Above, Fig. 3: Top, detail of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah; above, detail of Rubens’ The Raising of the Cross, Antwerp Cathedral. Where the former is claimed to be a lost picture Rubens painted in 1609-10, the latter was indisputably made by Rubens between 1610-11. Such pronounced differences in brushwork are inconceivable as that of two autograph paintings made at the same moment in Rubens’ oeuvre. Who, looking at this photo-comparison, could believe that Rubens had flitted between the ugly angular Cubist faceted feet in the Samson and Delilah statue (– try counting the toes and note the Art Deco zigzagging hem), and the superb plastic fluency, grace and anatomical fidelity seen throughout the Raising of the Cross?

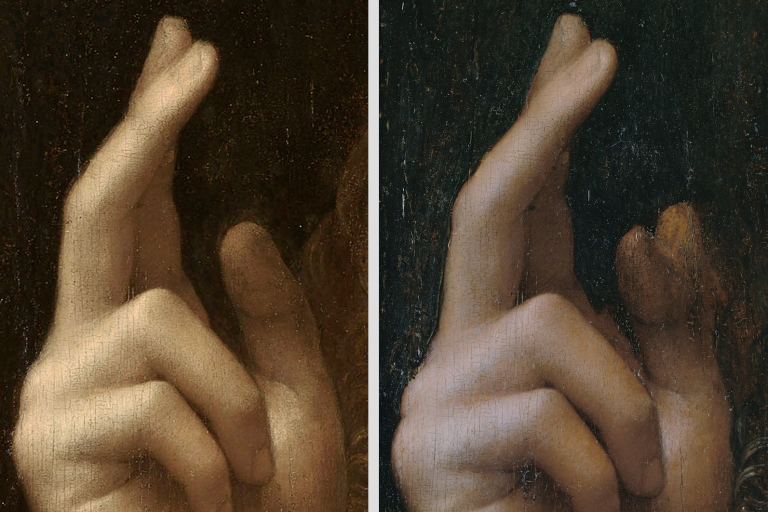

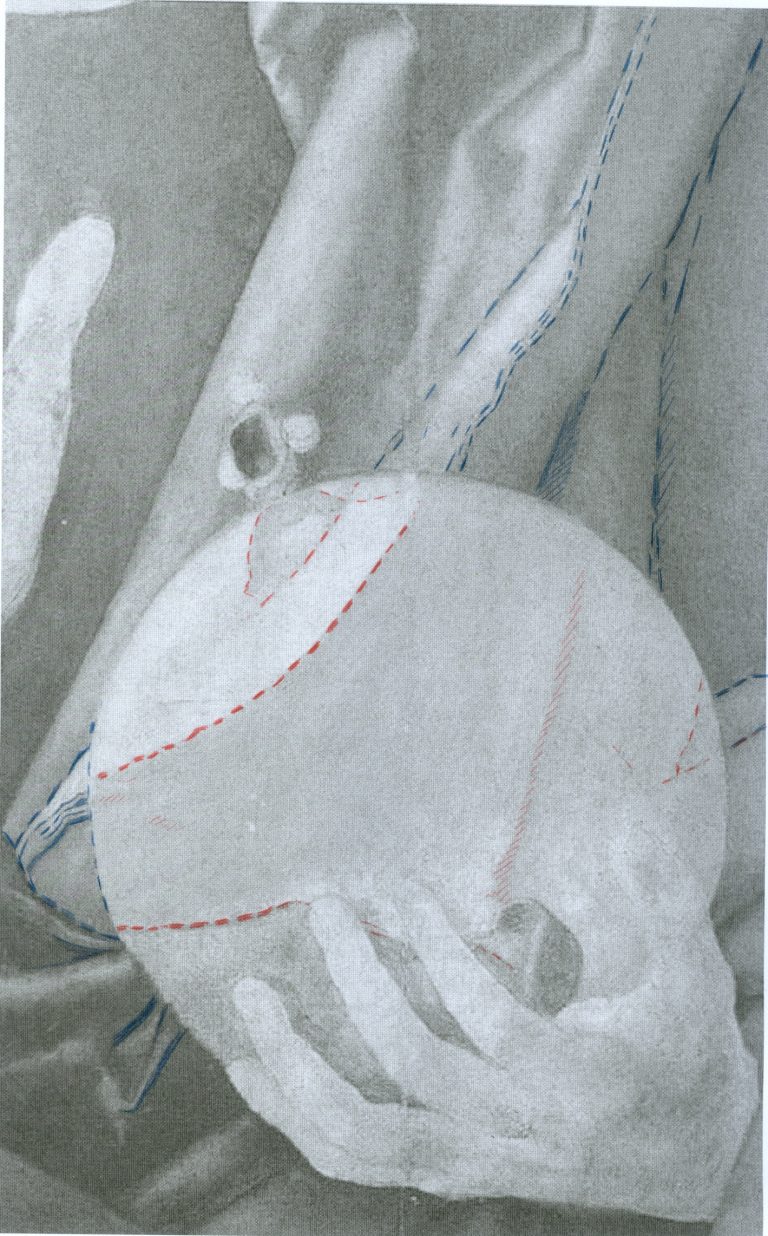

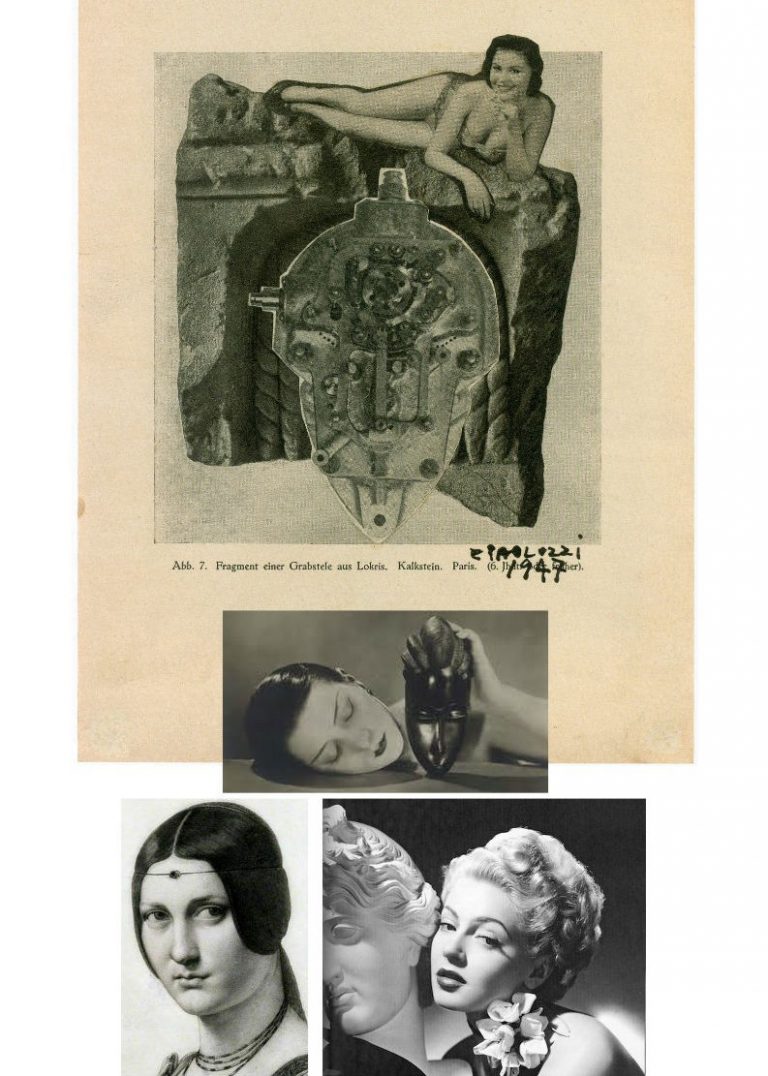

Above, Fig. 4: Two copies of the lost original Rubens Samson and Delilah – Top, Jacob Matham’s c. 1613 engraving (here reversed); bottom, Frans Francken II, a detail of his oil on copper depiction of the Grand Salon in Nicolaas Rockox’s House, made between 1615 and before 1640. Neither copy shows the cropped right foot found on the National Gallery picture. No one has cited a similarly cropped limb in any finished Rubens painting.

Above, Fig. 5: The National Gallery’s supposed Rubens Samson and Delilah painting.

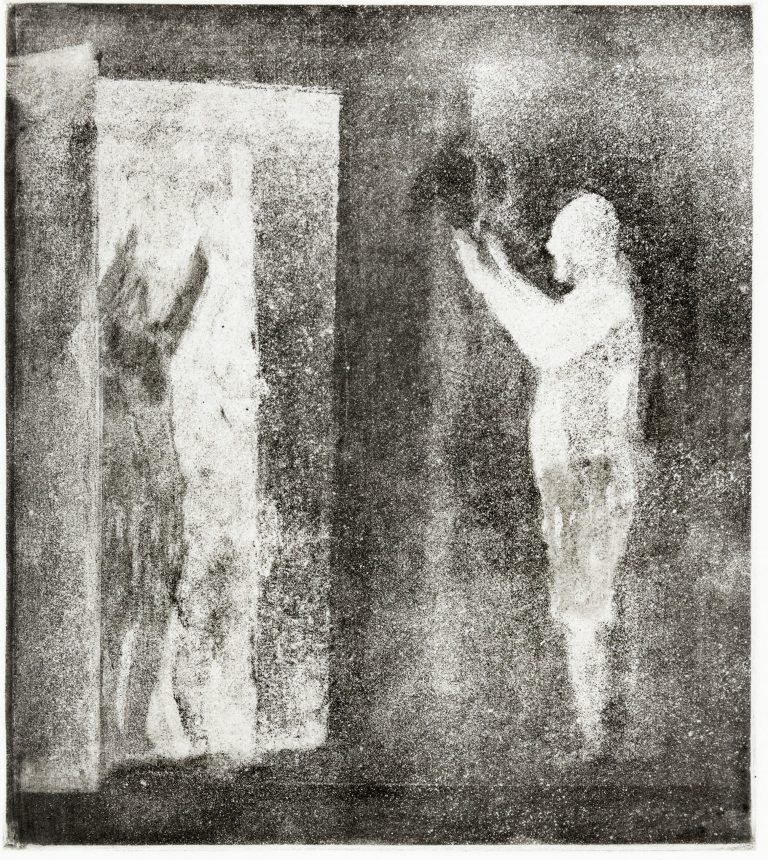

Above, Fig. 6: Left, a detail (from the left wing) of Rubens’ 1609-1610 The Raising of the Cross, Antwerp Cathedral. Right, a detail of the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah which Christopher Brown (David Jaffe’s predecessor as Senior Curator at the National Gallery) dates at “c.1609” and Jaffé puts “about 1610”. Among the National Gallery picture’s countless visual disqualifications, we would cite: the thinness of the paint; the absence of a 17th century craquelure; the irresolute profile; the cinematic lighting of the head; and, the anatomical and perspectival travestying of Delilah’s nose/mouth/chin configuration.

For many more disqualifying photo-comparisons, see Abigail Buchanan’s “The National Gallery ‘masterpiece’ that’s probably a fake”.

TANGLED DOCUMENTARY WEBS…

Such clinching visual evidence, however, leaves Adam Busiakiewicz unmoved and unpersuaded. He tells the Daily Telegraph that the National Gallery Samson and Delilah could be in no one but Rubens’ hand – viz: “‘It is a really stonking great picture,’ he says. ‘The textures, the sumptuous drapery, the muscular back – no one except Rubens could have painted that.’” Each to his own art critical estimations, perhaps, but what happened to the Samson and Delilah when in the National Gallery’s restoration studios is – or should be – a matter of scrupulously recorded and reported facts. We are now faced by a major art institution that cannot/will not give a proper and credible account of its own actions; that effectively denies, even, the historical record of its own doings. Consider the recorded facts: (1) it is a matter of record that this painting emerged in 1929 as a sound panel and that it remained so in 1977 (when exhibited in Antwerp); (2) it is known that in 1980 the picture was a panel when it was dispatched to London; when it arrived in London; and, when it was sold in London to the National Gallery; (3) it is known that when in London and on exhibition at the National Gallery it remained a panel in 1982 (- see Fig. 7 below). However, it is also known that the following year the National Gallery claimed – after the picture had been restored at the Gallery – that it was not now a panel at all – and, indeed, that it had not been a panel for a very long time and possibly, even, into the 19th century or beyond. This extraordinary denial of the picture’s own documented historical record might seem inexplicable in a major national institution, but it is by no means unprecedented – and nor, for that matter, is the Gallery’s effective outsourcing of its own defence to obligingly helpful scholarly proxies.

Not the least consequence of misleading institutionally-official accounts is the corruption of subsequent scholarship and the making of monkeys out of good faith and technically trusting patrons. In part-defence against widespread and prolonged criticisms of its notoriously over-energetic techno-adventurist restorations, the National Gallery ran a series of didactic, so-called “Making and Meaning” exhibitions. One such in 1996-97 was Rubens’s Landscapes. It was organised jointly by the Gallery’s then senior curator, Christopher Brown, and by its senior restorer, Anthony Reeve. The exhibition was sponsored by Esso UK plc and its chairman and chief executive, K.H. Taylor, expressed pleasure in being associated with “the quality of research and scholarship that are the Gallery’s hallmarks”. In turn, the then National Gallery director, Neil MacGregor, expressed gratitude to Esso for its generosity, for year after year, in enabling the Gallery to “present to the public recent research on how and why the pictures were made”. In a section on the rigorously high standards of professional panel making in 17th century Antwerp it was noted that panels were marked with their makers’ monograms and that the panel back of Rubens’s “Chapeau de Paille” portrait bore Antwerp’s coat of arms and the carved initials of its maker, Michiel Vriendt. However, with the Samson and Delilah no such assurance was offered. Instead, the reader seemingly learns – with a nod to the contrary testimony of Reeve and Bomford/Plesters (see Fig. 7 below) that “A particularly fine panel made for Rubens by an Antwerp panelmaker is that for the Samson and Delilah, painted about 1609 for Nicolaas Rockox…” But then, after a section reprising Reeve’s own 1982 Technical Bulletin account of the risks posed to such fine panels by fluctuations in humidity, comes an abrupt claim that “The Samson and Delilah was planed down to a thickness of about three millimetres and set into [sic] a new blockboard panel before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1980 and so no trace of a panelmaker’s mark can be found…”

Now, in Fig. 7 above we see two incompatible accounts that were made and published just a year apart in successive National Gallery Technical Bulletins. Which of the contrary pair might be taken by the public and future scholars to be the more reliable and trustworthy record? Reeve’s account had preceded that of Bomford/Plesters – he had seen and reported what he saw and knew. Brown must therefore have found himself in the unenviable position of having to choose between Reeve’s earlier account and the later contrary one of Bomford/Plesters. That is, he had either to accept that the picture came into the Gallery after it had been planed down by some unknown party at an indeterminate date and that Reeve had imagined and chronicled an entirely fictional panel comprised of “six [sic] horizontal oak planks, carefully planed and jointed”, or, recognising that Reeve of all people was unlikely to have confounded a new sheet of blockboard with an early 17th century Flemish oak panel and extol its technical virtues even among Rubens’s panels, or… what? What could Brown say of the Bomford/Plesters account when he was aware that the picture’s own dossiers contained the already widely press-reported and potentially explosive 1992 Doxiadis/Harvey/Hopkinson report precisely challenging the Bomford/Plesters account? Could he go down the middle and say that while the picture had come into the gallery as a panel in good shape – as Reeve had testified – when subsequently taken into restoration, it had been planed down and glued onto (not “into”) a new sheet of blockboard – and do so without offering any explanation for such a radical and inescapably material and historical evidence-erasing procedure? In the event, Brown did neither. Rather, he fudged a technically-incoherent mongrel account even though he and Reeve were the exhibition’s joint authors. That is, on the one hand he spoke of the Samson and Delilah having been a “particularly fine panel made for Rubens by an Antwerp panelmaker” and then, leaving a gaping, mystifying narrative hole in his own account, jumped to “The Samson and Delilah panel was planed down to… etc. etc.” This was a curatorial equivalent of the old comic book cop-out gag “With one bound, Jack was free”. It is not easy to conclude other than that it had seemed institutionally imperative to dissemble rather than clarify.

8 March 2025.

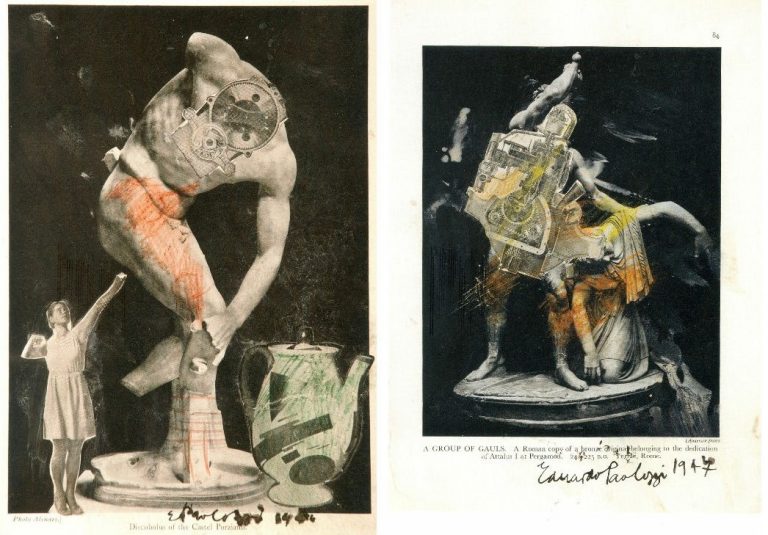

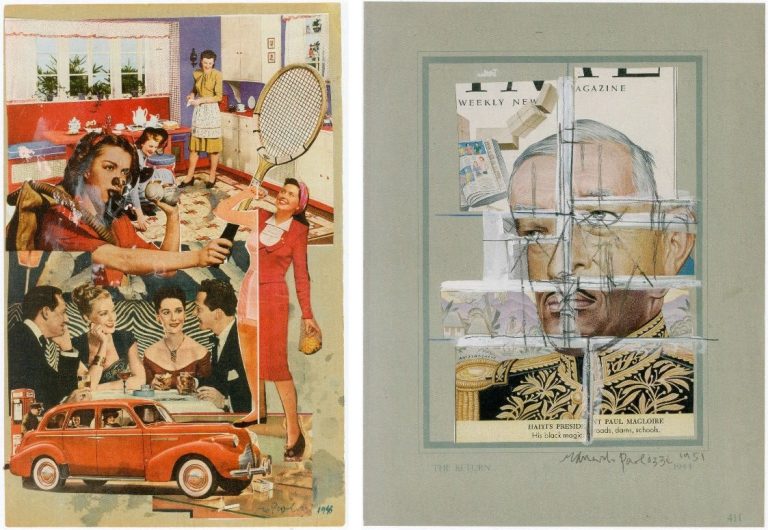

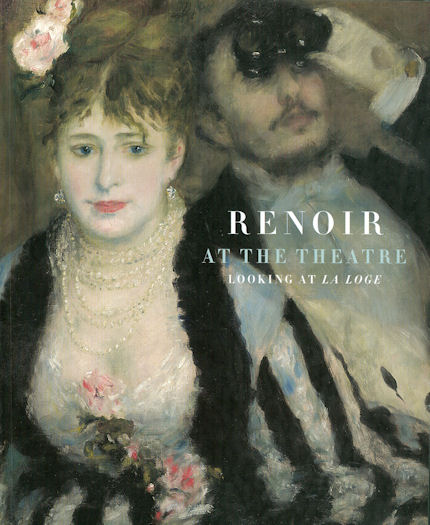

Good buy Duccio?

In Part I* of III, Michael Daley introduces the [$45-50m.] purchase of a panel attributed to the father of the Siennese school of painting (*As published in the November/December 2008 issue of the Jackdaw).

Spending pots of money on works of art is rarely without risk. The Metropolitan Museum’s 2004 decision to pay between $45-$50m (- in a blind “treaty” sale conducted by Christie’s) for the “Stoclet” Duccio Madonna and Child, already seems a source of anxiety. That the acquisition breached the Met’s own “due process” requirements was initially flaunted. It is no more. Our own researches suggest (– as will be discussed in Part II) that the attribution may prove unsound.

Four years after the Met’s Board authorised payment (- after the event ) for this Duccio, the architects of the acquisition, Philippe de Montebello, who is retiring after thirty-one years as Director, and Keith Christiansen, the Museum’s curator of European Painting, now seem to be saying: “The Duccio remains a great acquisition – but it was his responsibility more than mine”.

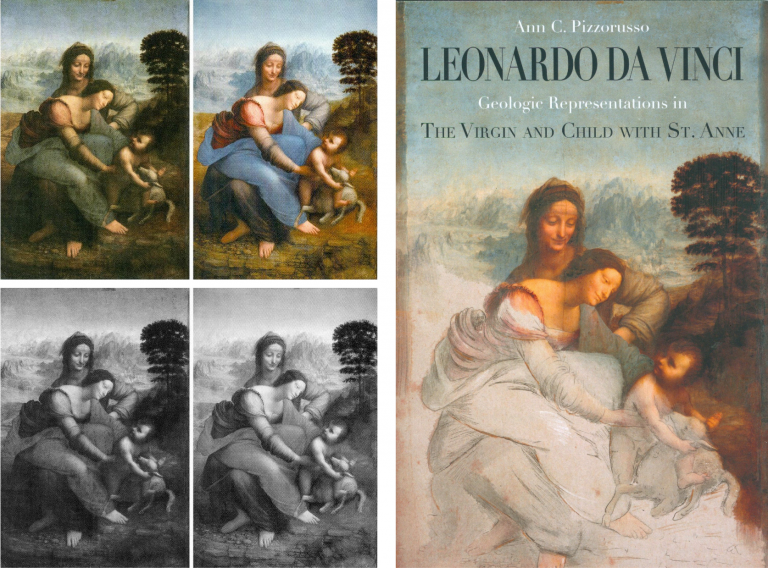

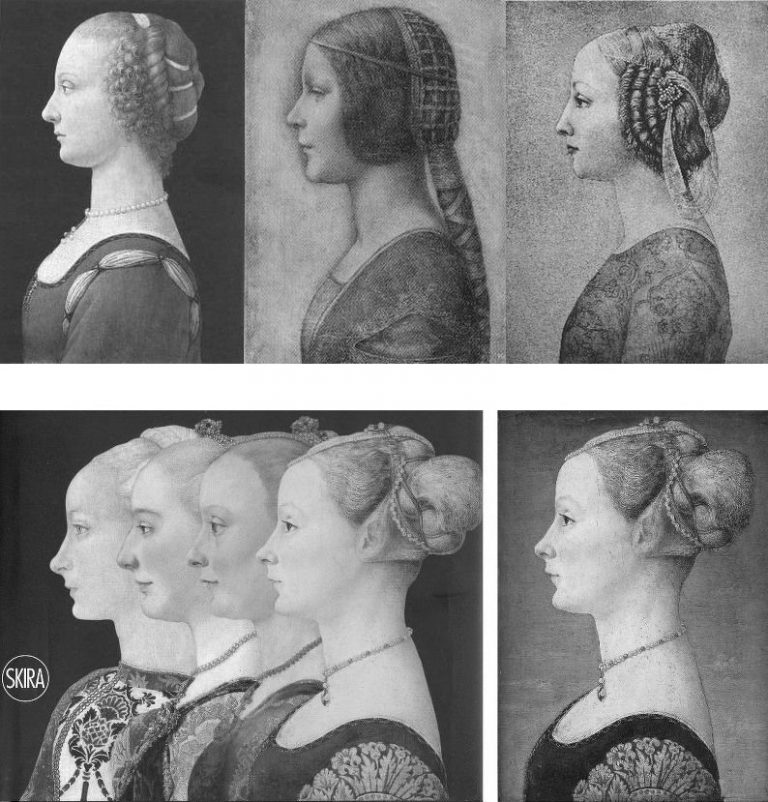

Above, the “Met Duccio” as it appears today (right) and as it appeared in 1904 (left) when it had recently emerged without provenance – that is: it was said to have been bought by a Russian collector from an antiques shop.

Christiansen gave detailed account of his role in Danny Danziger’s 2007 book Museum ~ Behind the scenes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

“…Nicholas Hall of Christie’s, with whom I have been friends for many years, phoned me up and said, ‘I would like you to have lunch with me; there is something I’d like to show you.’ During the meal he slipped me a transparency, and I looked at it.

It was a painting that had not been seen by any of the major Duccio specialists for fifty years; it had been in the hands of the Stoclet family and out of circulation. ‘Fantastic, how about the price?’ I asked. He told me. ‘OK,’ I said, ‘I will deal with that later.’ And then we finished our lunch.

…I waited for the director to come back from his vacation. And then I went into his office and said, ‘I am duty bound to show you this,’ and then I showed him the transparency. I casually said to him, ‘You know, Philippe, you deserve this picture. Tom Hoving had his Juan de Pareja [a stunning portrait by Velazquez, bought in 1970 for $5.5m], Rorimer had his Rembrandt [the majestic double portrait Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, bought in 1961 for $2.3m.]; I don’t see why you shouldn’t have this towards the end of your career’…”

De Montebello told Calvin Tomkins in the New Yorker (July 2005):

“I was just smitten by the transparency, as anyone would be, and I decided we had to go and look at this picture… It’s the single most important purchase during my twenty-eight years as director. It’s my Juan Parega, it’s my Aristotle with the bust of Homer… There was not an ounce of doubt in my mind about it… Technically I was not authorized to make an offer. I just took a chance that my trustees would go along.”

Christiansen had lauded this decisiveness in the New York Times on November 10 2004: “When I showed it to him, it took him about 30 seconds to say, ‘We really have to have this.’” But in a prefatory note to the Metropolitan Museum’s Summer 2008 Art Bulletin (which is given over to Christiansen’s: “Duccio and the Origins of Western Painting”), de Montebello now downplays his own role:

“…I wish simply to correct the misleading impression that in making an acquisition of this importance and expense, it was my response to the picture’s quality and art historical significance and my confidence in that response that was the determinative factor… recommending so large an expenditure to our Acquisitions Committee required more than just my response… It required that this response be reinforced by the assurance that comes from the trust I have learned to place in the curators and conservators in this great institution… As I held the picture in my hands, enraptured by its wonderful quality… I was treated all the while to Keith’s impassioned scholarship… it was particularly Keith’s precise and learned assessment of the picture that allowed me to consider the acquisition an imperative.”

In his own Bulletin foreword, Christiansen again admits this was a work known to scholars only by photographs; that it had very recently been withdrawn from a (comparative) exhibition on Duccio and his followers – despite being in the catalogue; that it had never undergone any modern scientific analysis; and, that in the normal course of events, it would have been sent to the Museum for examination and eventual presentation before the Acquisitions Committee, composed of members of the Board of trustees. He then tells how he and the Met’s restorer, Dorothy Mahon, travelled with the Director to Christie’s, London:

“We spent about two hours with the picture before calling the Christie’s representatives back into the room. I imagined that we were now about to embark on drawn-out discussions and negotiations, with intense pressure from other institutions. This assumption proved dead wrong. The Director seized the initiative and stated that he was prepared to make an offer for the painting. I don’t know who was more taken aback, the Christie’s representatives or Dorothy and I… On the return flight I noticed that the Director was bent over a list of what seemed to be various funds that might be applied to the purchase of the picture. ‘You must have worked out the mechanics for this even before we left to examine the picture,’ I observed. ‘Oh yes, this trip was to confirm that the picture was as extraordinary as it already seemed to me, and if it was, I had determined we were going to get it.’ Trustees still needed to be consulted and further funds identified, and weeks were to pass before a final deed of sale was signed. But the key step had been taken…”

Indeed it had.

Coming next in Part II: “BUYER BEWARE”

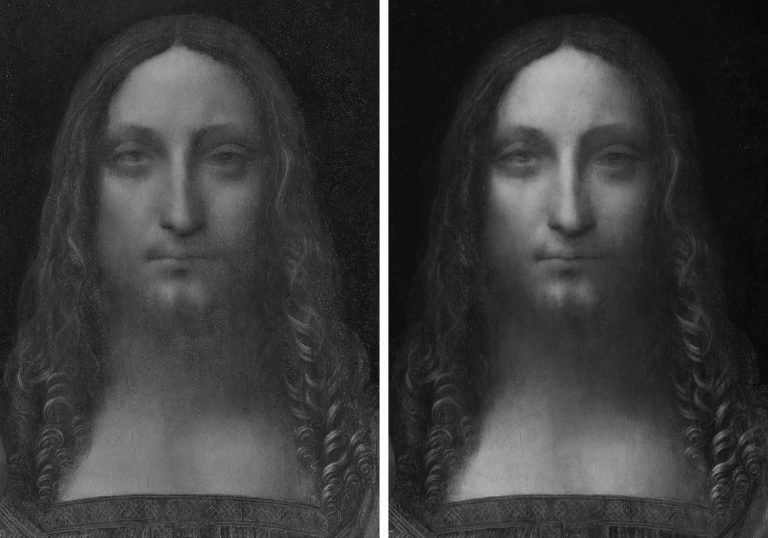

Further Thoughts II: The less and less Leonardo ex-Cook collection Salvator Mundi

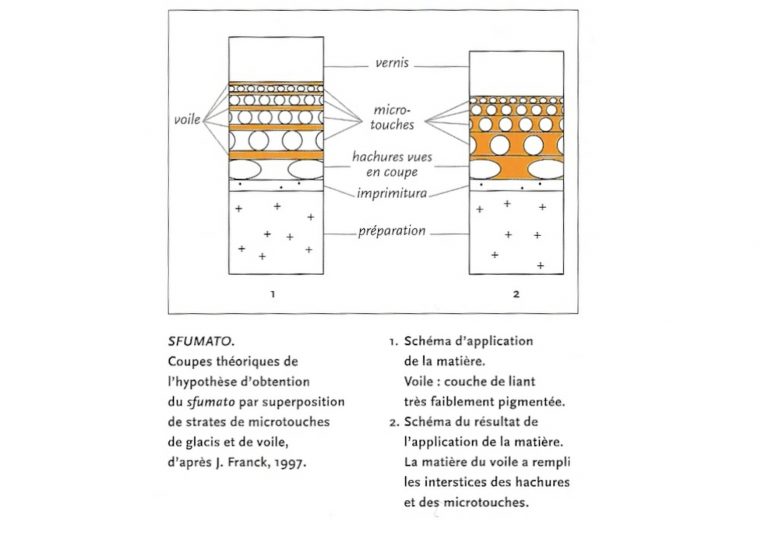

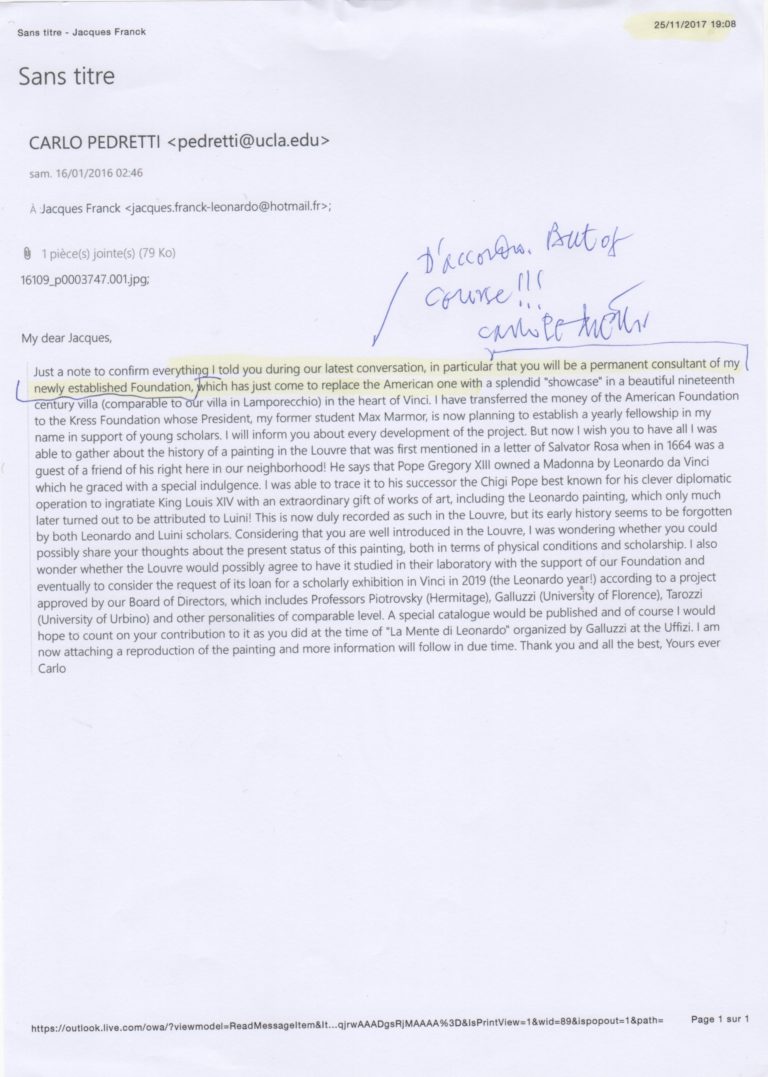

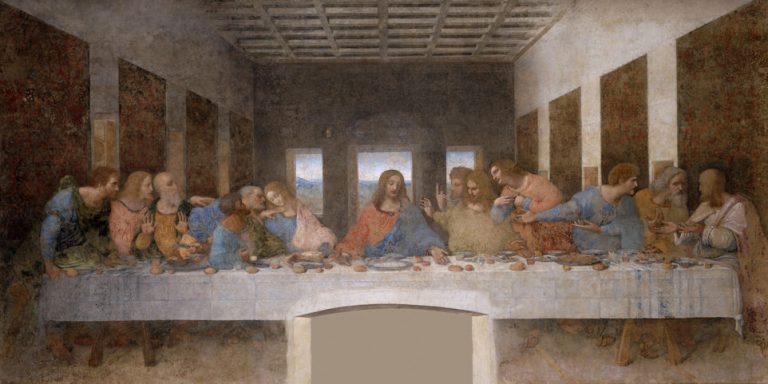

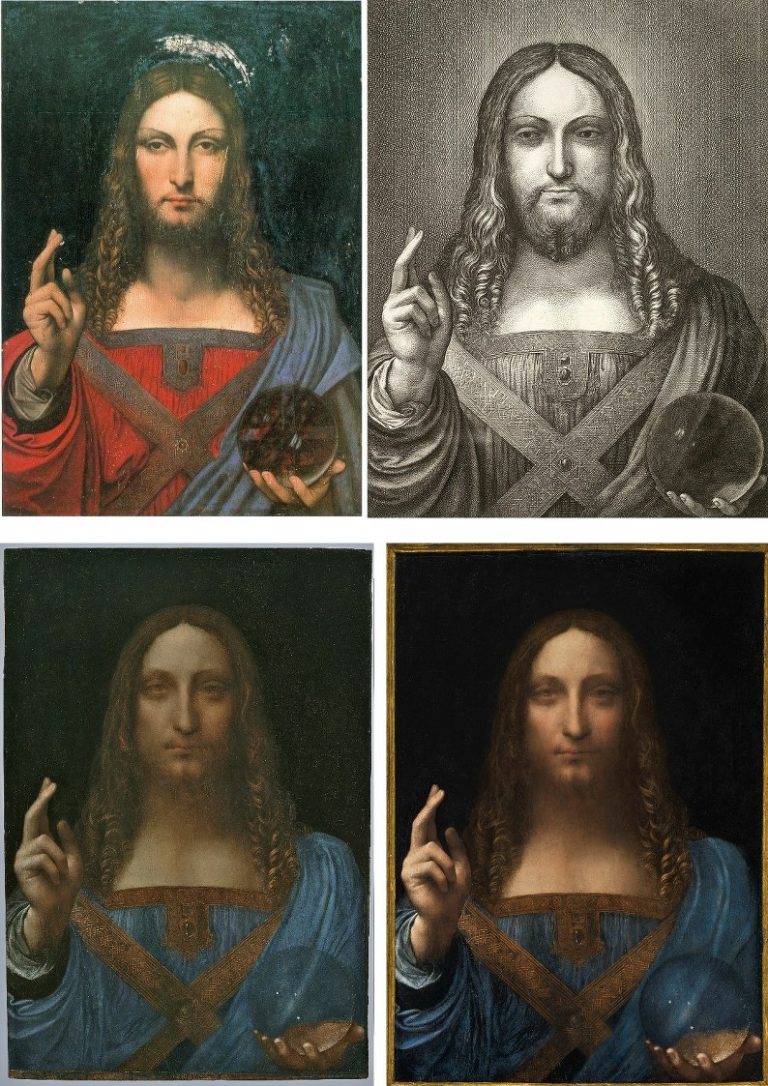

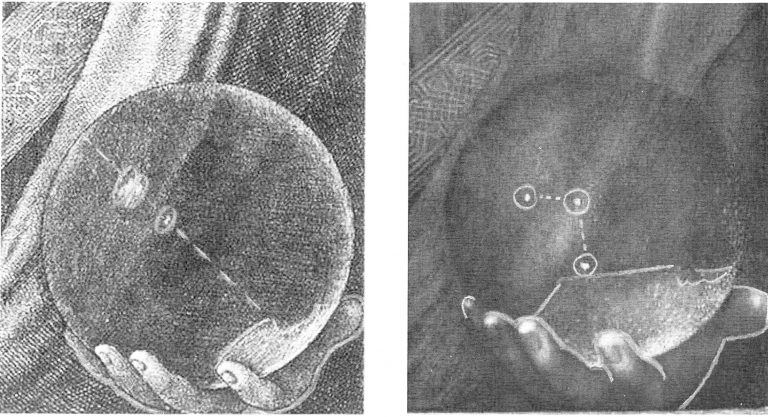

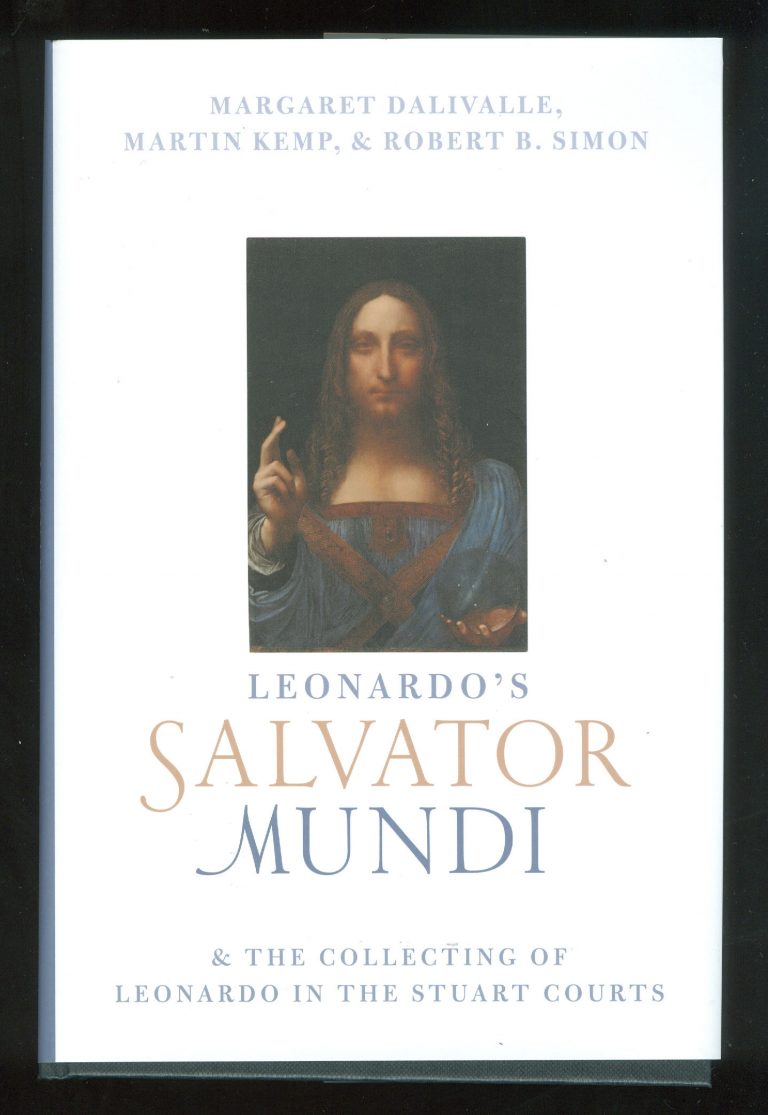

Jacques Franck here concludes his three-part demolition of the once attributed but now deposed, $450m New York/Russian/Saudi Leonardo da Vinci Salvator Mundi picture’s supposed stylistic, artistic and technical credentials.

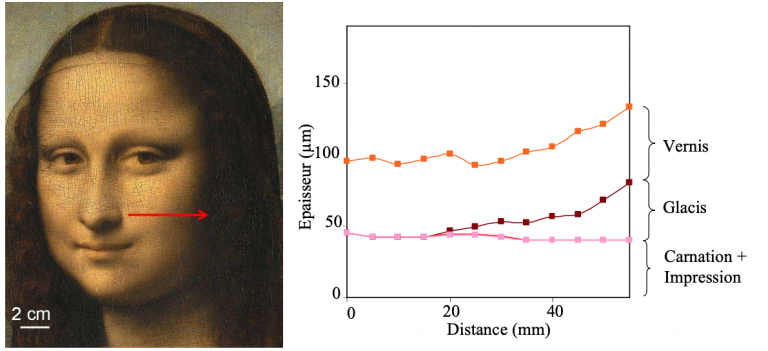

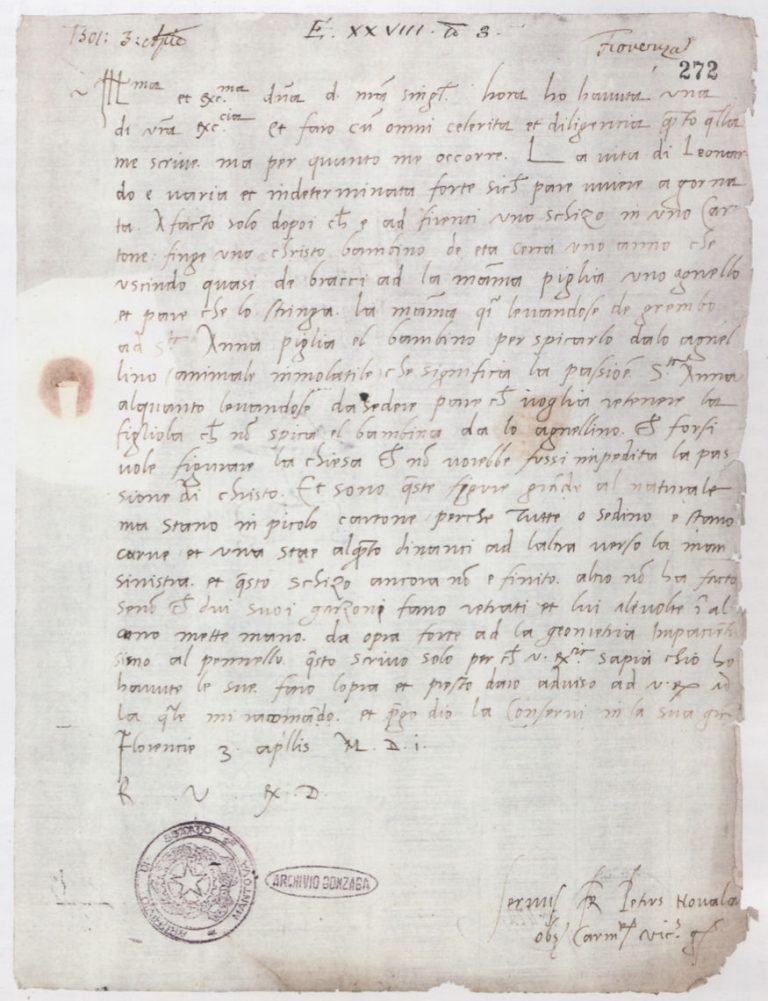

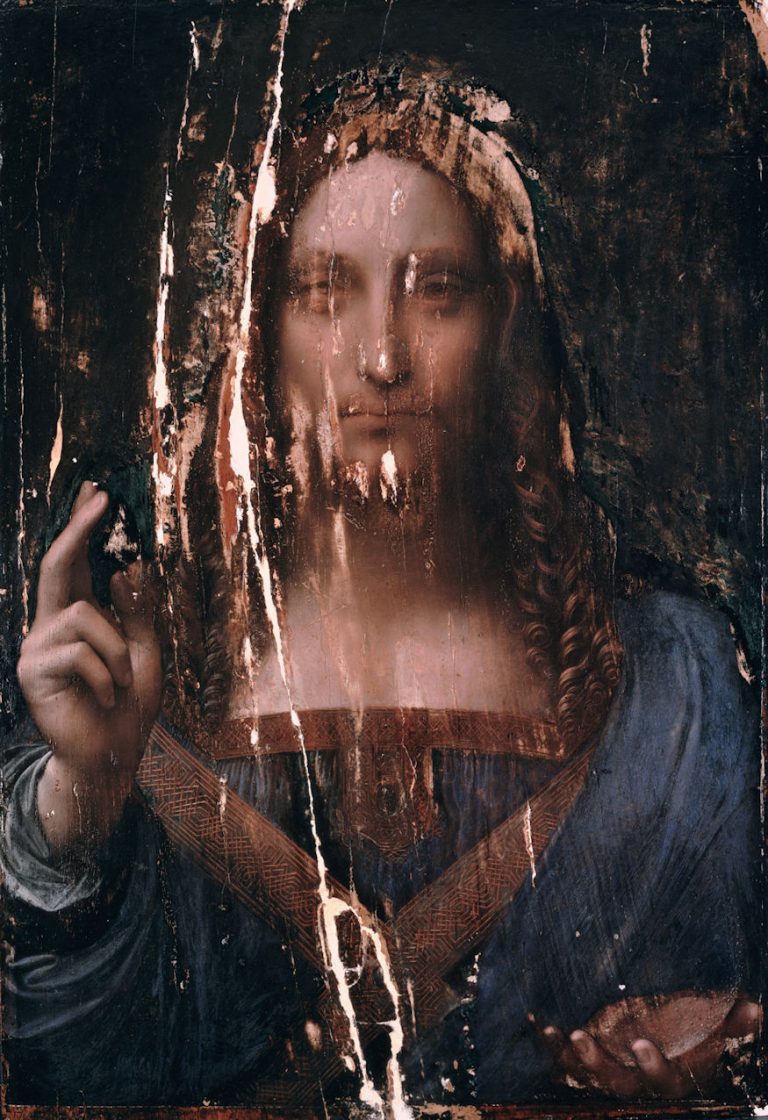

Jacques Franck writes: Many events have occurred since the publication here of my August 2020 essay on the “New York Salvator Mundi” and it seems timely to update and close the subject in the light of recently emerged technical data on the controversial painting. To grasp the present situation, a reprise of recent key events is necessary.

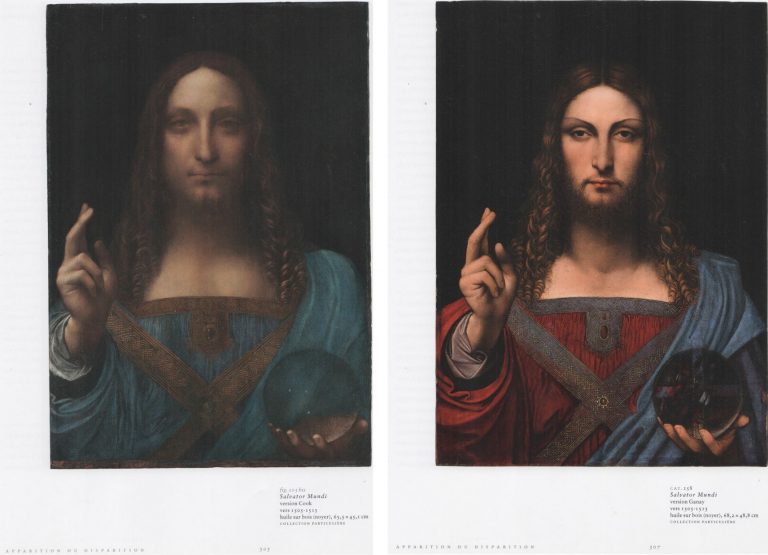

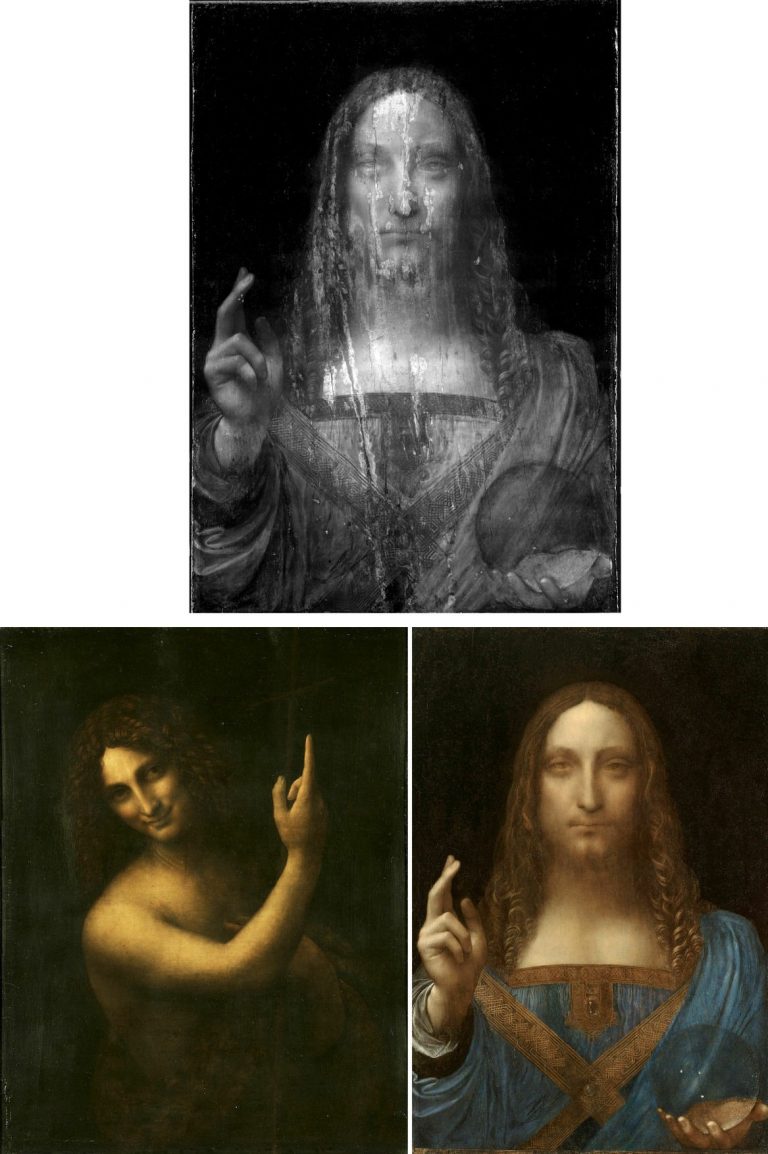

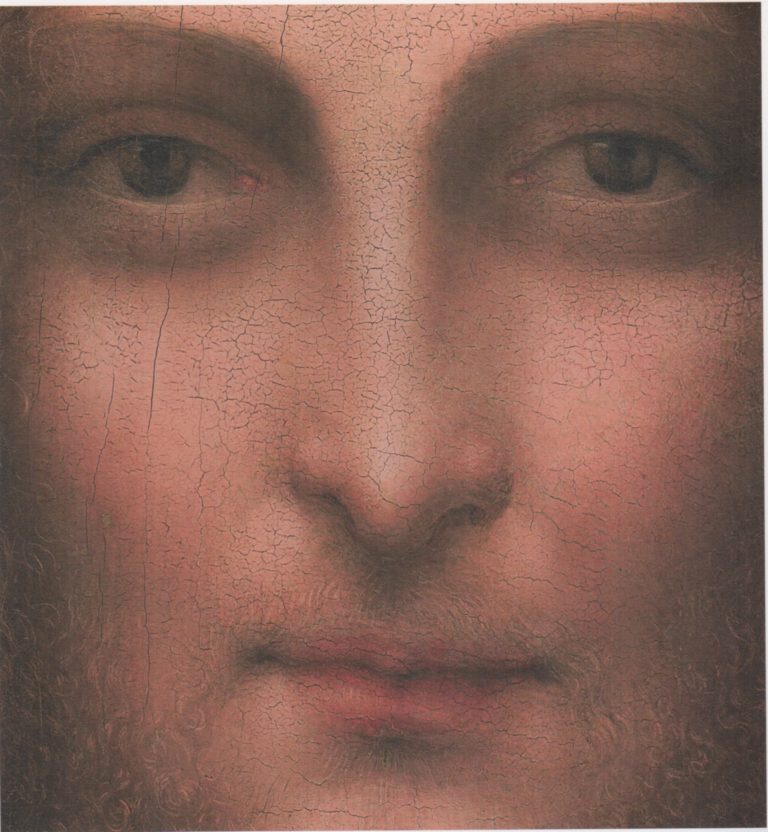

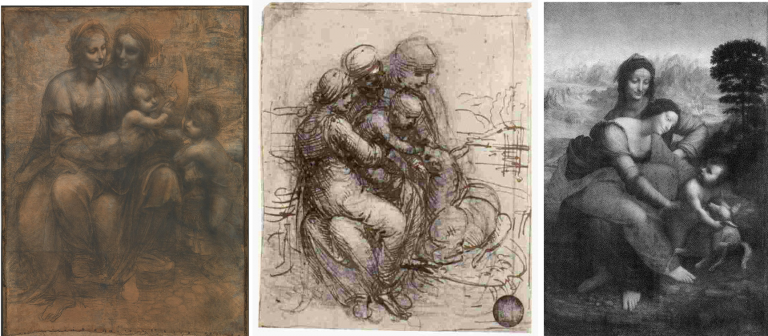

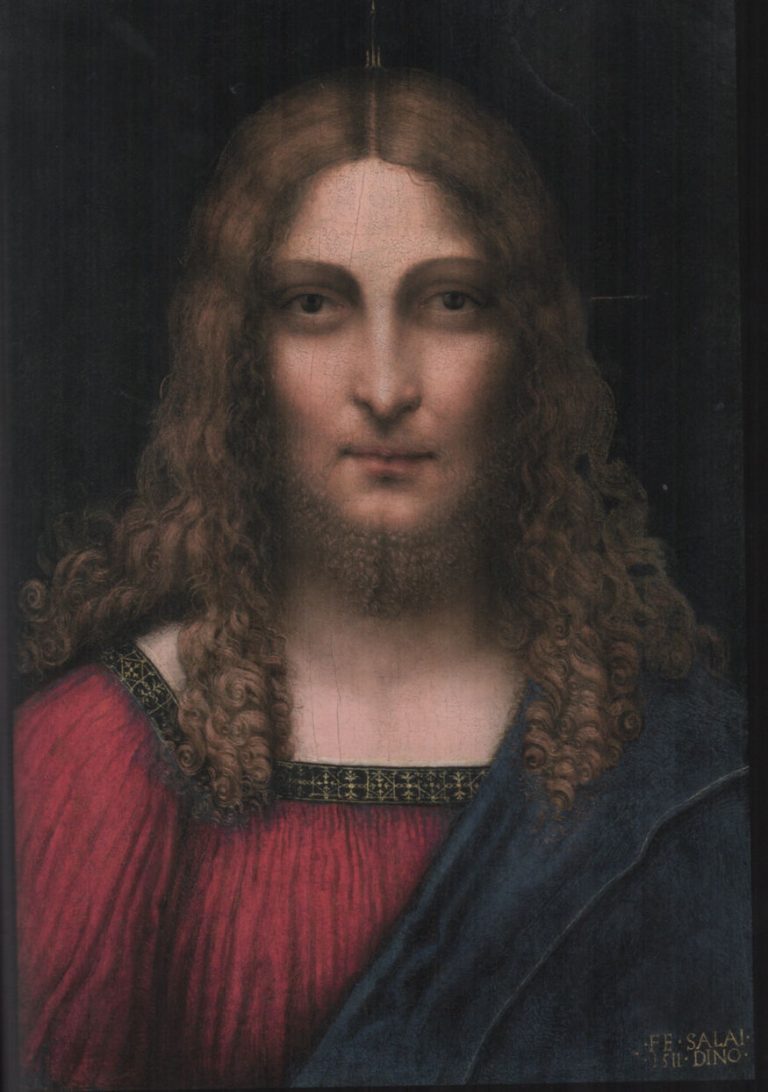

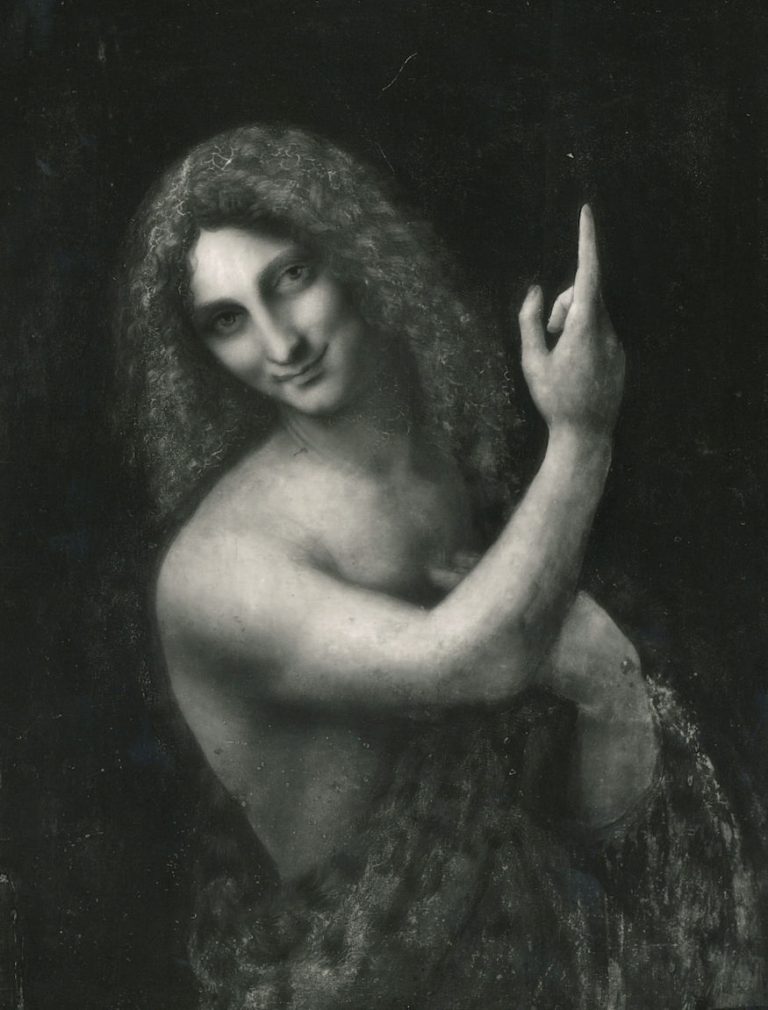

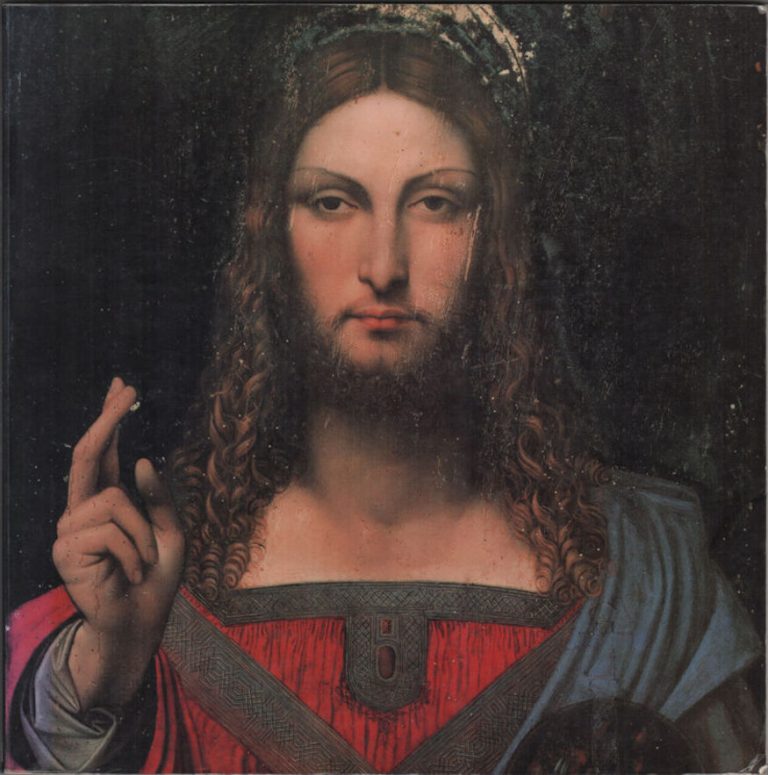

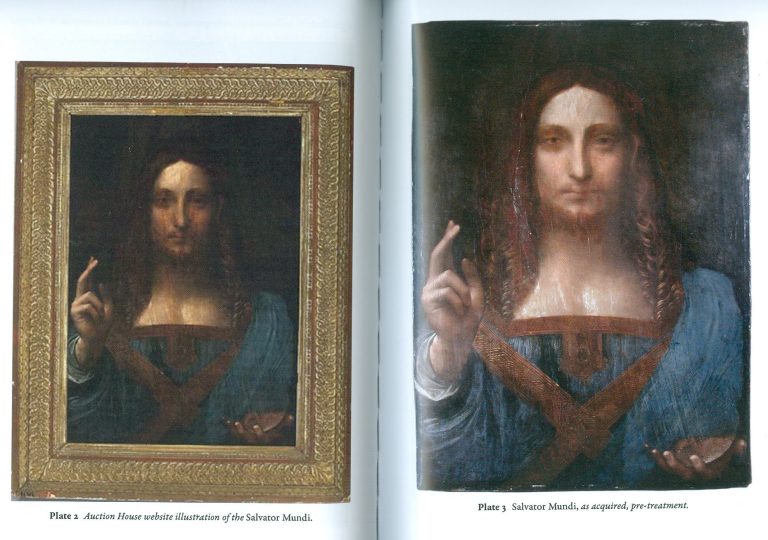

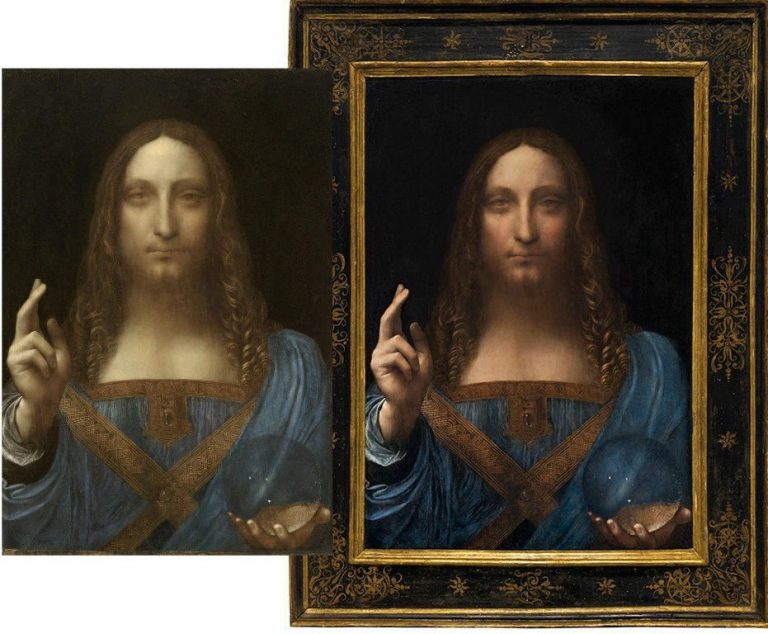

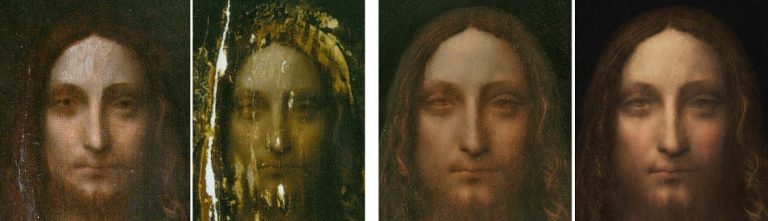

Above, Fig. 1: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of. G. A. Boltraffio?), Christ as Salvator Mundi (“the Cook version of Salvator Mundi“), c. 1506/1508-1513, oil on walnut, 65.5 x 45.1 cm (Private Collection), as seen in 2011-12.

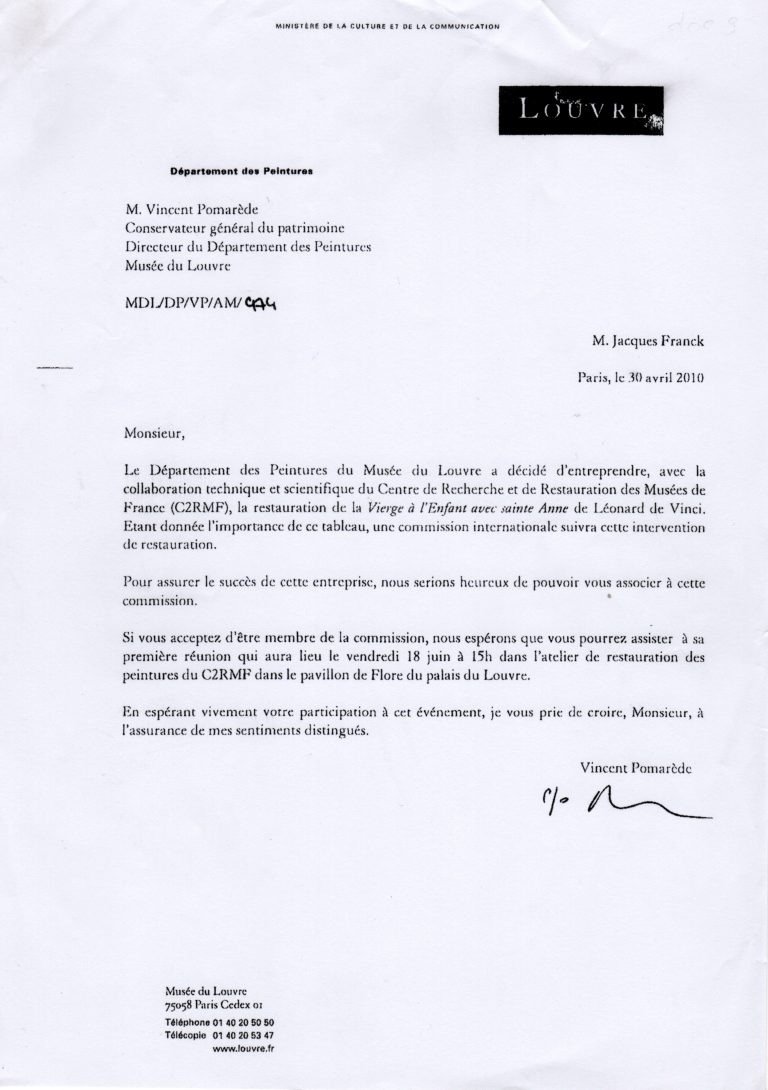

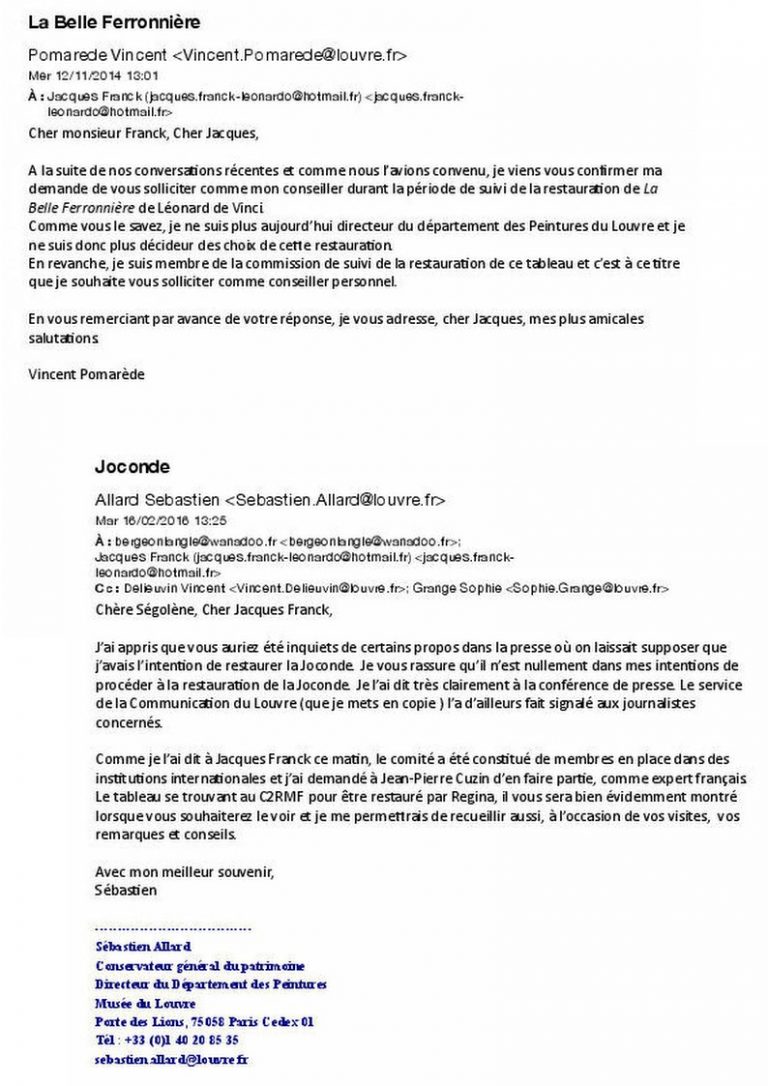

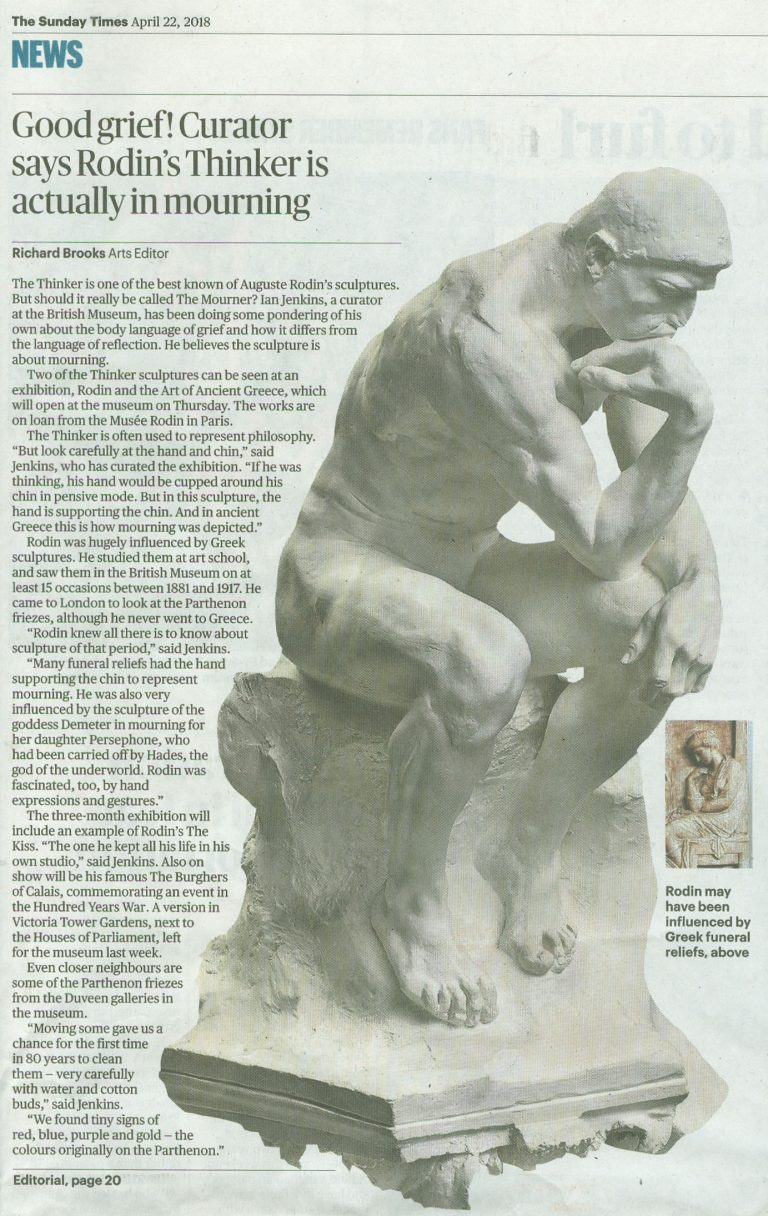

The Louvre’s junked book: a contradiction that does not exist

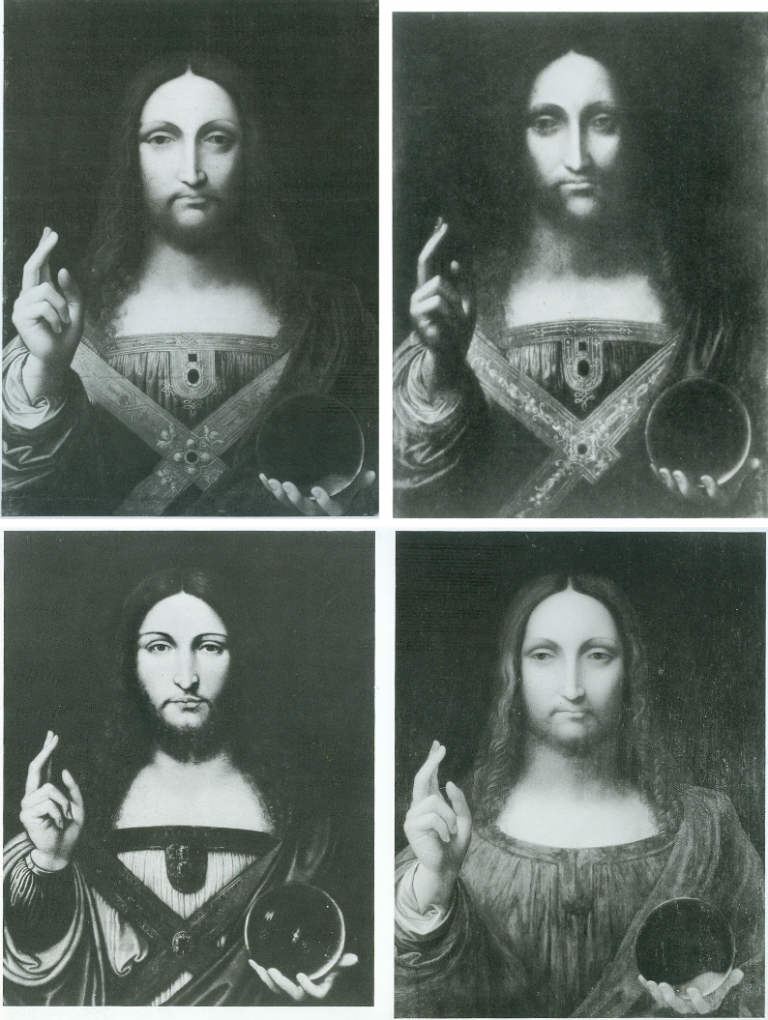

It cannot be doubted that months before the Louvre’s major Leonardo da Vinci exhibition opened in Paris in Autumn 2019 the museum still believed that the Salvator Mundi was an autograph work of Leonardo. This is testified by the fact that the initial version of the Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition catalogue was printed with the (former New York, now Saudi) painting labelled as an indisputably true da Vinci picture. Shortly afterwards, that first version of the catalogue was suppressed and a new version was printed with a radically revised attribution. In it, the work – which itself was not included in the exhibition – was simply reproduced and listed as “Fig. 103 bis. Salvator Mundi version Cook” (meaning a “studio work” with a status analogous to that of another well-known Leonardo studio Salvator Mundi, called the “Ganay version”) (Fig. 2 below). Whatever reasons precipitated this sudden change, the new designation definitively constituted the Museum’s then – and still – estimation of the former New York and now “Saudi Salvator Mundi”. At this stage, that judgement is, of course, irreversible.

Above, Fig. 2: Left, Léonard de Vinci, exhibition catalogue, Louvre éditions, Paris, 2019, p. 305 (Cook Salvator Mundi); right, Léonard de Vinci, exhibition catalogue, Louvre éditions, Paris, 2019, p. 307 (Ganay Salvator Mundi).

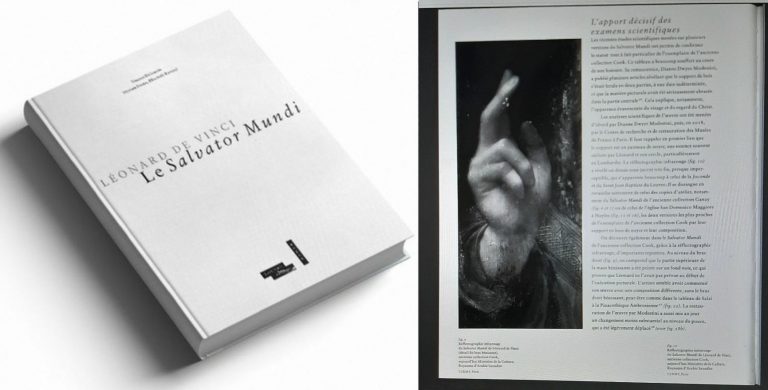

The Disappeared Louvre Technical Book – aka the “would-be-decisive-scientific-examination-of-short-lived-appearance” of December 2019

Above, Fig. 3: Left, Vincent Delieuvin, Myriam Eveno, Élisabeth Ravaud, Léonard de Vinci, Salvator Mundi, Louvre éditions – Hazan, Paris 2019, (as published in The Art Newspaper); right, a page taken from Vincent Delieuvin, Élisabeth Ravaud, Léonard de Vinci. Le Salvator Mundi, Louvre éditions – Hazan, Paris, 2019.

Above, Fig. 4: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, back of the wood panel.

Quite strangely, a 46-page booklet titled “Léonard de Vinci. Le Salvator Mundi” was published jointly by the Louvre and its laboratory (C2RMF) six weeks after the exhibition’s 24 October 2019 opening at the Louvre (Fig. 3, above). On no official announcement or evident sanction, the booklet is said to have made a very brief and accidental appearance in the Museum’s bookshop in December 2019. Its authors, Vincent Delieuvin (Leonardo curator at the Louvre), Myriam Eveno and Élisabeth Ravaud (Louvre’s laboratory C2RMF scientists), had considered and contended that the New York Salvator Mundi is an authentic Leonardo. Thus, their historical and scientific essays radically opposed the picture’s studio attribution as stated in the official exhibition catalogue. Unsurprisingly, the dissenting publication was swiftly withdrawn and the museum itself neither recognized the book’s existence nor its embarrassing contents.

With the reasons for the booklet’s leak still remaining obscure, it would be risky indeed to accept a theory in circulation whereby the pro-Leonardo version of the catalogue had been printed together with the scientific booklet in the event of the Salvator Mundi being exhibited, while another entire catalogue, in which the picture was downgraded, had also been printed simultaneously on the possibility that a loan of the picture might be refused. Such a scenario does not accord with the fact that the junked booklet was printed in December 2019 – which is to say, after the exhibition had opened – while both versions of the exhibition catalogue, one of which was abandoned, had been printed two months earlier in October. Such a theory would thus suggest that Louvre Museum staffs’ scientific investigations are determined not by matters of hard material evidence and duly considered professional judgements but, rather, according to political expediencies such as whether or not a loan request might be granted. Who could believe such a tale? Science is science and it is certainly not a discipline with one rule for one political eventuality and one rule for another. Museum laboratory researchers certainly do not draft contrary and rival test results from a single investigation so that they might comply with an institution’s future stance. Moreover, while the phantom book’s existence was known to the small circle of the Leonardo specialists after its short-lived bookshop appearance, for a long time, nobody was fully apprised of its actual contents (bar rare circulating scanned pages).

The problematic ‘‘Mona Lisa‘s male alter ego’’

While the Salvator Mundi‘s standing was not intended to remain unresolved indefinitely, its intrinsic mystery deepened with certain revelations disclosed in an April 2021 French documentary film “The Saviour For Sale. The Story of Salvator Mundi” by Antoine Vitkine on the picture’s various stages of upgrading as a retrieved Leonardo masterpiece which culminated in November 2017 when sold as such at Christie’s, New York, for $450m. Besides the sensational episodes of the work’s thriller-like route to financial success, the film addressed the long-expected loan to the Louvre and the consequent stumbling negotiations between the museum and the Salvator Mundi‘s owner, the Saudi prince Mohammad bin Salman, nicknamed MBS. Thus, we first learn that in June 2018 the panel painting was sent to the Louvre to be examined at length closely in the Museum’s laboratory and that the results of this survey, confirming the Leonardo attribution, are those recorded and discussed in the withdrawn booklet (Fig. 3 above); but then, that shortly before the blockbuster’s inauguration, the Louvre invited several Leonardo specialists to examine the painting before finalizing a loan process with MBS. At that date in 2019, the scholars’ opinion was not as favourable as that of the C2RMF scientists in 2018 and the work was downgraded to being by Leonardo in part only. The film also reports that MBS (quite understandably) resisted his property’s lowered artistic status and made clear that unless the Salvator Mundi was exhibited next to the Mona Lisa (thereby underscoring its originally claimed status when promoted by Christie’s as a “Male Mona Lisa” ahead of its November 2017 sale) the loan would be refused. Misinterpreting this imbroglio, certain parties today claim that the 2019 downgrading had prompted the Prince’s exorbitant clause. In any event, the subsequent insistence that the Salvator Mundi be shown in the exhibition as the ‘‘Mona Lisa‘s male alter ego’’, side by side, was one the Louvre could not accept for security reasons quite aside from the work’s recently lowered artistic status.

The revelations of the Vitkine film precipitated an art world earthquake: the long-running suspense from the moment the Louvre requested the loan from the owner shortly after the November 2017 New York sale, until the very day of the Leonardo exhibition opening in Paris, two years later, had been the consequence of a tumultuous negotiation over the artistic status and attribution of the painting that terminated in a late and drastic 2019 reappraisal. The unexpected downgrading by the museum that holds the most important collection of Leonardo masterpieces in the world, including the legendary Mona Lisa, constituted the strongest possible reversal and disavowal to the accrued federation of parties that had fervently and assiduously promoted the work as a Leonardo for over a decade.

Needless to say, the recent leaking of the contents of the withdrawn booklet – “the book that doesn’t exist” as many have called it – by Leonardo upgrade partisans has considerably increased the saga’s fog of ambiguity and even restored hope among the True Leonardo Believers that their icon may yet be crowned as an autograph work of the master. Nevertheless, given that the Salvator Mundi picture concerned cannot be both a true Leonardo and a studio work, the staggering contradiction between the Louvre’s present (and official attribution, as advised by leading specialists) and the C2RMF’s earlier scientific investigation of 2018, has yet to be resolved. For that reason, checking the internal scientific consistency of the “no book” now seems both essential and urgent.

Like many Leonardo scholars I have been supplied a PDF of the book “for information”, so to speak. Since, with its now international circulation, the book’s contents are no longer a guarded secret and given that many of its issues are at the heart of my own researches there are no reasons for me not to make public my observations on the mystery book’s contents and postulates. The task is made easier because the C2RMF 2018 investigation has been supplemented by other earlier and institutionally separate investigations conducted over a number of years before and after the 2017 New York sale, notably in the USA.

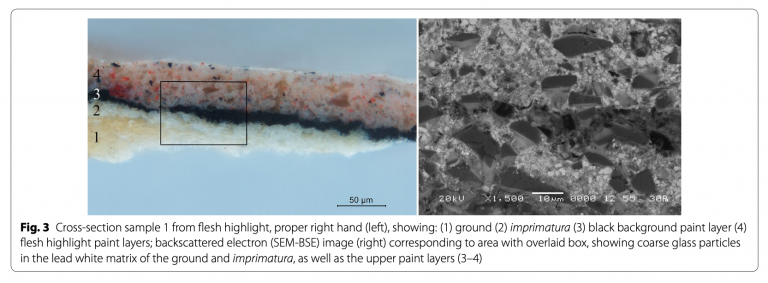

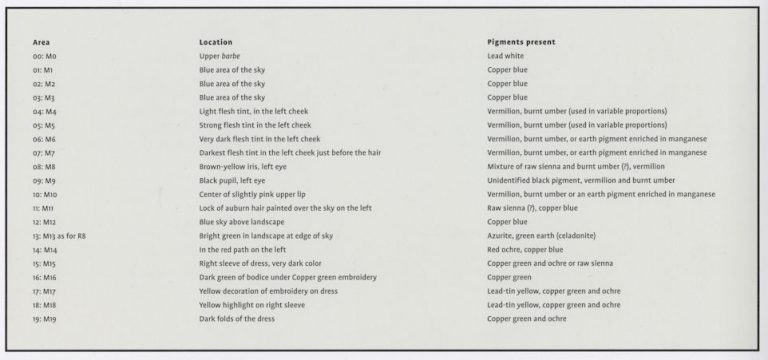

The assorted technical analyses of the Cook version of Salvator Mundi

The phantom Louvre booklet displays two essays: Vincent Delieuvin’s historical account of the undocumented creation of a Salvator Mundi by Leonardo (hereafter referred to as Delieuvin, 2019); and a detailed technical report by Myriam Eveno and Élisabeth Ravaud, both C2RMF scientists (hereafter referred to as Eveno and Ravaud, 2019). I shall mainly review this latter essay (albeit with some forays into Delieuvin’s piece) because its material addresses the factual aspects of the picture – that is, its physical structure and the specific components used for its execution. When necessary, I shall also refer to an American scientific investigation whose last stage was published on 20 April 2020 in Heritage Science by Nica Gutman Rieppi, Beth A. Price, Ken Sutherland, Andrew P. Lins, Richard Newman, Pen Wang, Tin Wang and Thomas J. Tague Jr. (hereafter, Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020) [1]. Some of the latter’s work was delivered by Dianne Modestini in 2014 [2].

Delieuvin’s optimistic tone contrasts with the tests themselves, which are far from conclusive, as we shall see (“The decisive contribution of the scientific examination”, Delieuvin, 2019, p. 14, my translation – unless specified, all translations are mine). My astonishment was pronounced when, having noticed the poorly significant elements actually observed by Eveno and Ravaud, I encountered the conclusion: “[In our opinion] the examination of the Salvator Mundi seems to demonstrate that Leonardo has executed the work indeed” (Eveno and Ravaud, p. 38). That latter statement was audacious: although the scientific investigation of paintings is inescapable as a rational means to understand both their structures and techniques – and as such, is of crucial assistance to art historians – it can never prove whether a painting is by one hand or another, here being that of Leonardo.

From misinterpreted observations to rushed conclusions (why the C2RMF’s 2018 scientific investigation was not to be made public)

Let us now consider a number of points which explicitly reveal why the two questionable Louvre essays, which bear conclusions extrapolated from shaky grounds, were – rightly – not meant to be published by the Louvre.

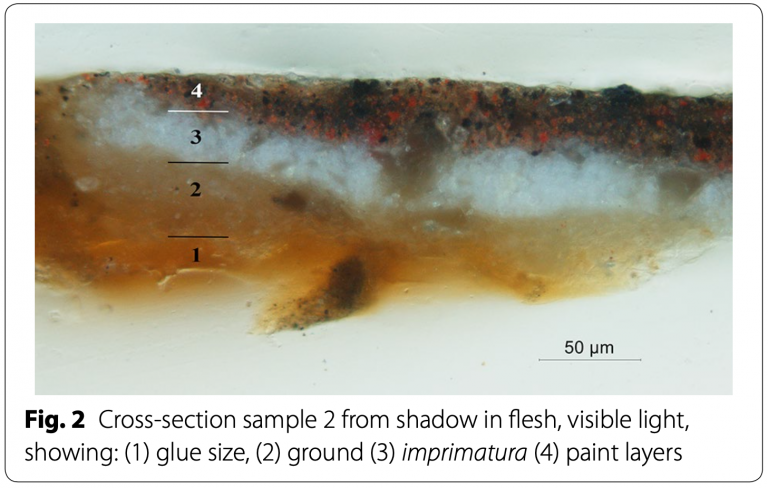

I: Panel preparation

Above, Fig. 5 [after Rieppi, Price, Sutherland, et al., 2020, Fig. 2]: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, a cross section sample from shadow in flesh, visible light, showing: (1) glue size, (2) ground, (3) imprimitura, (4) paint layers.

Above, Fig. 6: Ambrogio de’ Predis (?), Portrait of a Man aged 20 (“The Archinto Portrait”), 1494, oil on walnut, 54.4 x 38.4 cm (panel), London, National Gallery.

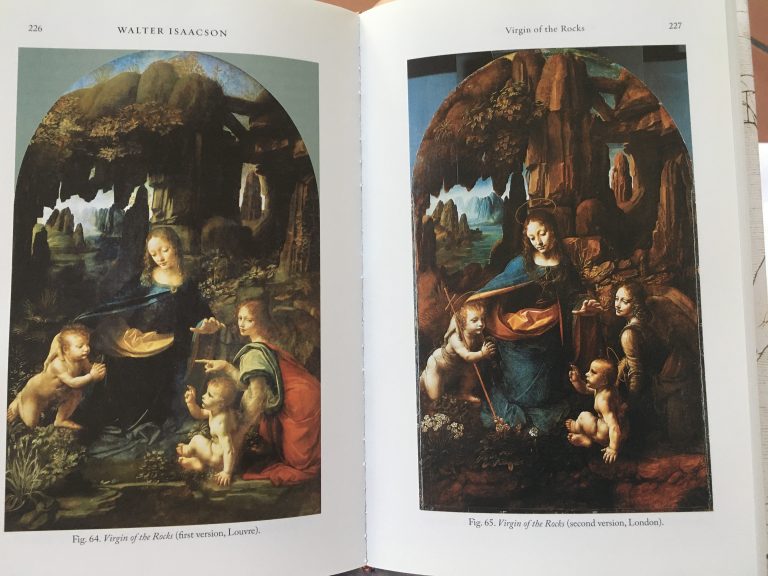

Unlike most Leonardos (aside from the Belle Ferronnière and Saint John the Baptist), the (NY/Saudi) Salvator Mundi was painted on a walnut panel prepared with a white ground applied over the wood, which had first been coated with an unpigmented size layer (Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al. 2020, p. 9, fig. 2) (Figs. 4 and 5, above). The traditional calcium sulphate gesso is, however, mainly encountered in numerous Leonardos like the Adoration of the Magi, the Louvre version of The Virgin of the Rocks or the Saint Anne. With those, the white ground layer was followed by a thinner off-white priming layer called imprimitura; both layers contain a lead white pigment presumably bound in oil, while a small amount of a lead-tin yellow was found in the thinner second layer. These ground layers also contain glass particles of variable dimensions (consistent with manganese-containing soda-lime glass) of a type commonly encountered in Italian paintings (Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020, p. 10-12).

Eveno and Ravaud admit that the panel preparation (with the ground layers laid directly over the sized wood) of the then New York picture is unusual for Leonardo. Against that, they contend that it is found also in works like the Lady with an Ermine, the Belle Ferronnière and the Mona Lisa (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 37). While this preparatory configuration is an established fact concerning the (now) Saudi Salvator Mundi, as testified by the cross-sections published under Modestini’s direction, to my knowledge no samples (except one in the Lady with an Ermine in 1960, which is yet to be re-examined in the light of modern-day scientific methods) have been taken from the above-mentioned Leonardos. As a result, this technique of preparation is simply presumed in their case despite the researches published by the same C2RMF team in 2014 [3]. Additionally, from the latter publication we learn that this same panel preparation (ground layers of lead white applied on a walnut wood board) has been identified in Leonardo’s circle’s panel paintings, notably in the Portrait of Bernardo di Salla by Giovanni Francesco Caroto (Louvre), in a Salvator Mundi privately owned (Leonardo school) and, quite interestingly, in the Archinto Portrait attributed – notably – to either Ambrogio de ‘Predis or Marco d’Oggiono (both Leonardo’s main assistants) kept in the National Gallery in London (Ravaud and Eveno, 2014, p. 135 sq.) (Fig. 6, above). In other words, no striking evidence exists that might prove that the panel preparation in the Salvator Mundi is clearly and uniquely specific to Leonardo’s own usage, or indeed confirms that, thanks to this technical feature – as stated by the two C2RMF scientists – the possibility of its being a studio work can be automatically rejected.

Furthermore, and as if in lieu of any technical confirmation, the authors hold the preparation’s peculiarity (never observed in any of Leonardo’s own works) as strong evidence per se, on the grounds that “it accords well with Leonardo’s inventive mind, who constantly experiments new recipes, as testified by the great variety of the preparatory processes [he] employed throughout his career” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 37). And this hypothesis is offered despite the fact that the addition of grained and powdered glass particles to the two ground layers is itself another peculiarity, never encountered in Leonardo paintings either (idem) while, conversely, it has been identified in the priming layer (called imprimitura) laid over the gesso preparation in works by such artists as Lorenzo Costa, Perugino, Vincenzo Foppa, and, regularly from 1501 onwards, by Michelangelo (idem) (see infra, Fig. 12, right, backscattered electron [SEM-BSE] image).

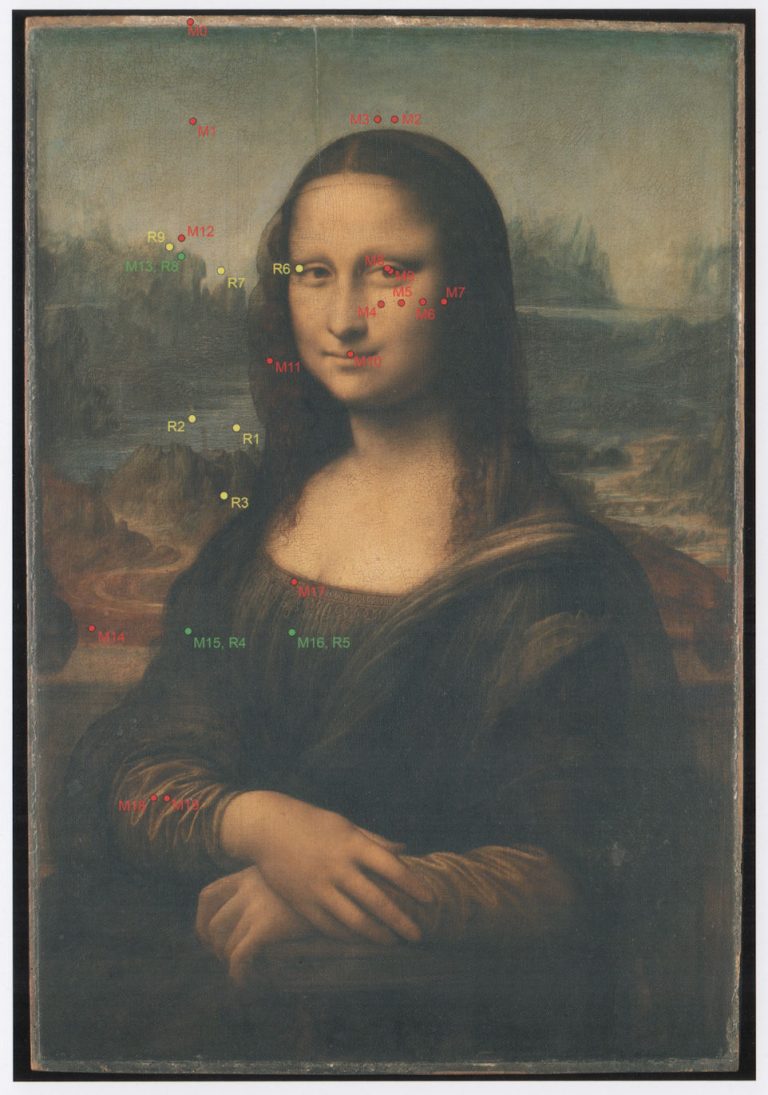

Above, Fig. 7: top, Raphael, The Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Nicholas of Bari (“The Ansidei Madonna”), dated 1505, oil on poplar, 245 x 157 cm (painted area 216.8 x 147.6 cm), London, National Gallery; above, The Ansidei Madonna, a cross-section from the grey paint of the architecture in which particles of glass are visible in the pale yellow imprimitura.

Given that this observation is strange to Leonardo’s known practice and corresponds much more to that of other painters, including Raphael (not cited in Eveno’s and Ravaud’s 2019 essay) (Fig. 7, above) – and, presumably, to their circles – one wonders how the two C2RMF researchers came to take it as a distinctive sign of his technique. Moreover, they are further at risk when positing themselves firmly on a specific role of the glass in the ground layers: “its use, even in the preparation, appears to us as being a distinctive characteristic of Leonardo’s quest for transparency” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019 p. 38). It is true that the use of glass in paintings may be a means to improve the translucency of the paint layer, according to specific conditions, in which the refraction index of the glass and the layers where it will be introduced. In fact, the ground layers are not the level in the paint film where Leonardo would need transparency, but are where he might want to secure the proper drying of the paint, hence the American researchers’ acknowledging statement: “Glass may alternatively have been used for aesthetic effect by enhancing the translucency of the paint, but in the case of the Salvator Mundi, the glass in the lower ground and imprimitura layers more likely functioned as a siccative since these layers are not visible in the final painting image. It is also possible that the glass was added to adjust the handling and textural properties of the panel preparation materials” (Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020, p. 13) [4].

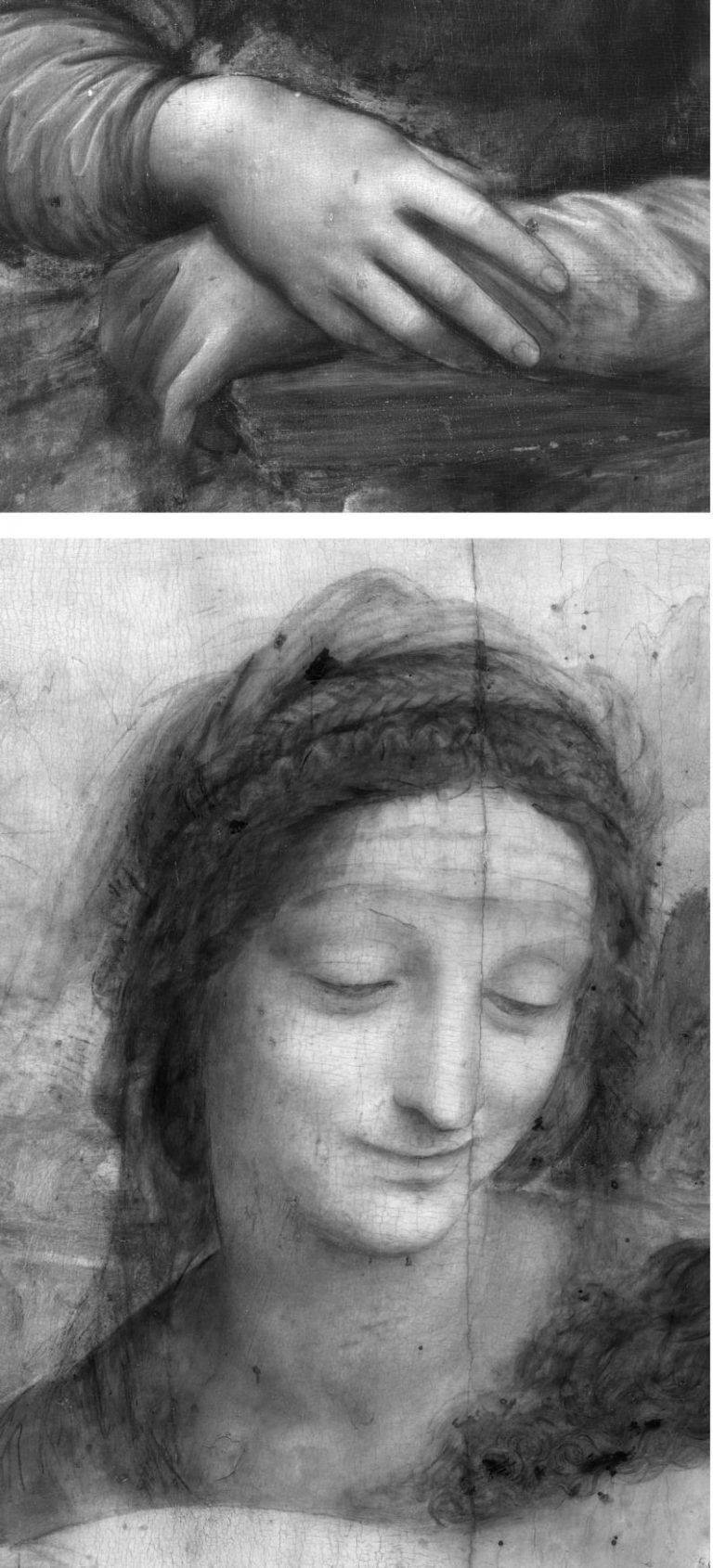

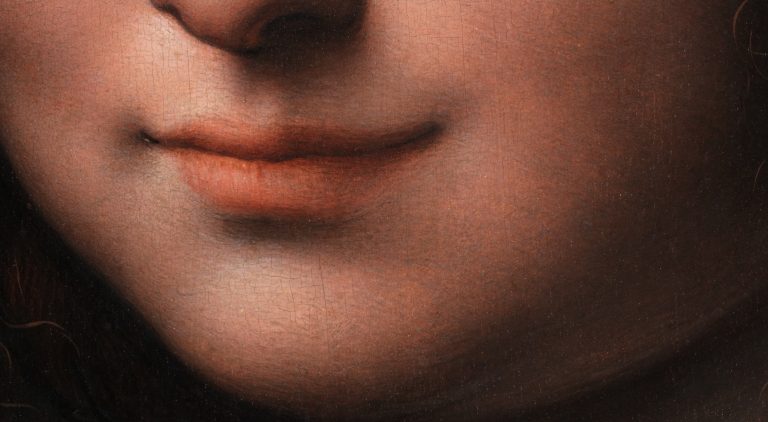

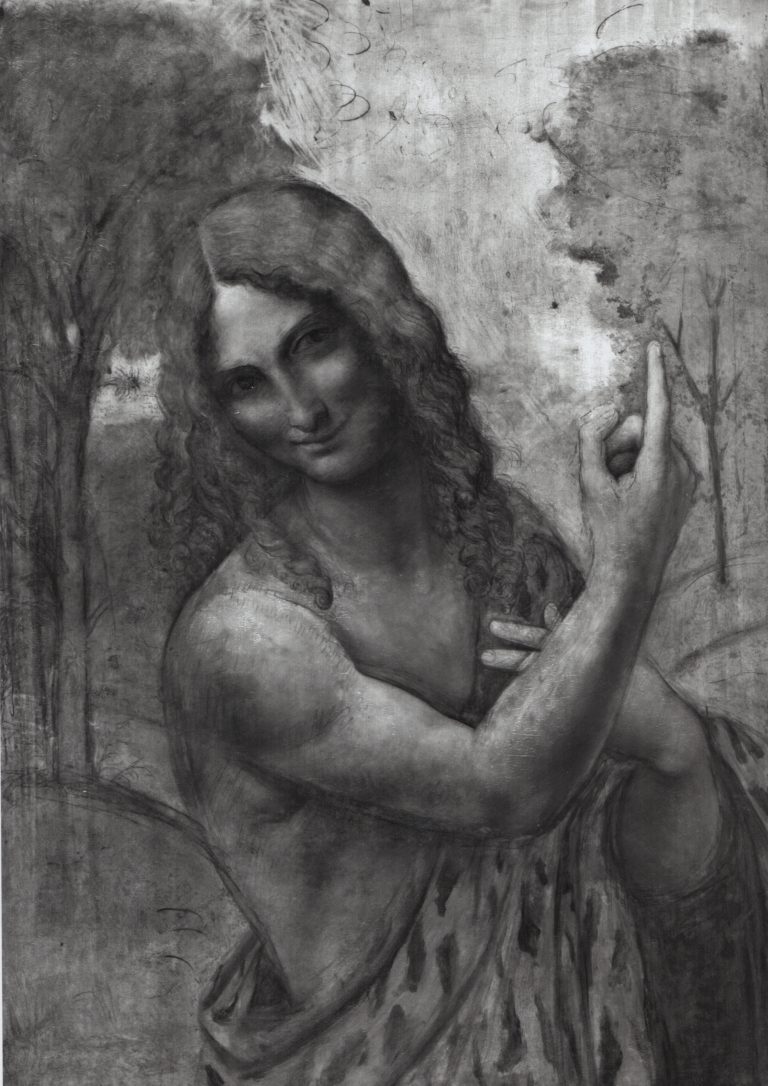

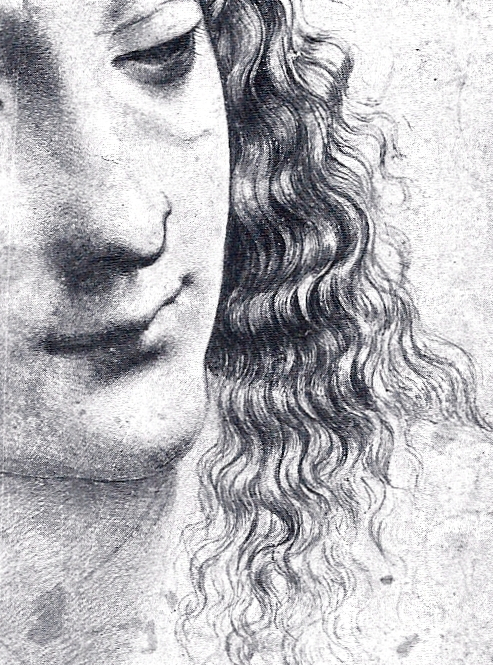

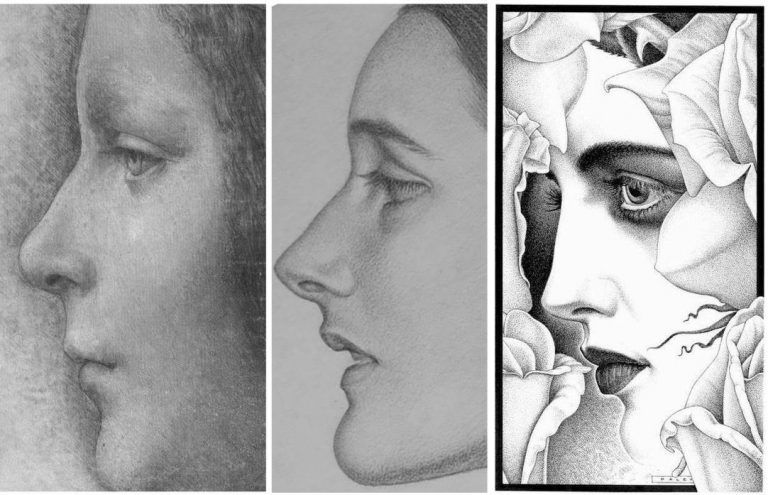

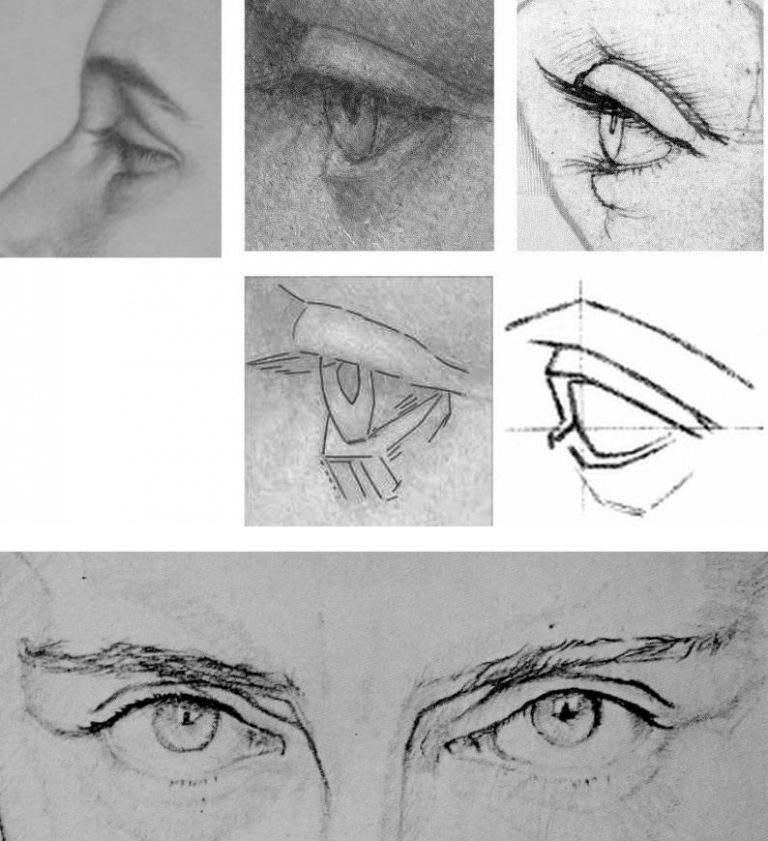

II: The underdrawing and the partial use of the infrared reflectograms

Infrared reflectography helps to detect underdrawings in paintings: infrared rays traverse the paint surface and reveal the underlying lines and wash techniques used to draw and sketch out the overall composition when they are constituted, in particular, of carbonaceous materials such as charcoal, bone black, or soot (lampblack) containing inks. Once again, Delieuvin expresses astounding optimistic views regarding the underdrawing found in the Cook Salvator Mundi: “Infrared reflectography has revealed a very thin and imperceptible underdrawing which much resembles that of the Mona Lisa and of the Saint John the Baptist in the Louvre” (Delieuvin, 2019, p. 14). This is not exactly what can be understood from Eveno’s and Ravaud’s report in the same book: “[Infrared examination has revealed] some rare thin lines absorbing infrared rays, therefore of an a priori carbonaceous nature. They delimit in particular the left eye’s iris. One notices the presence of a double contour line on a well-preserved fragment of the upper lip, although no spolvero dots can be distinguished. The other lines of the composition’s implementation have seemingly been executed in the course of the painting process” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 31).

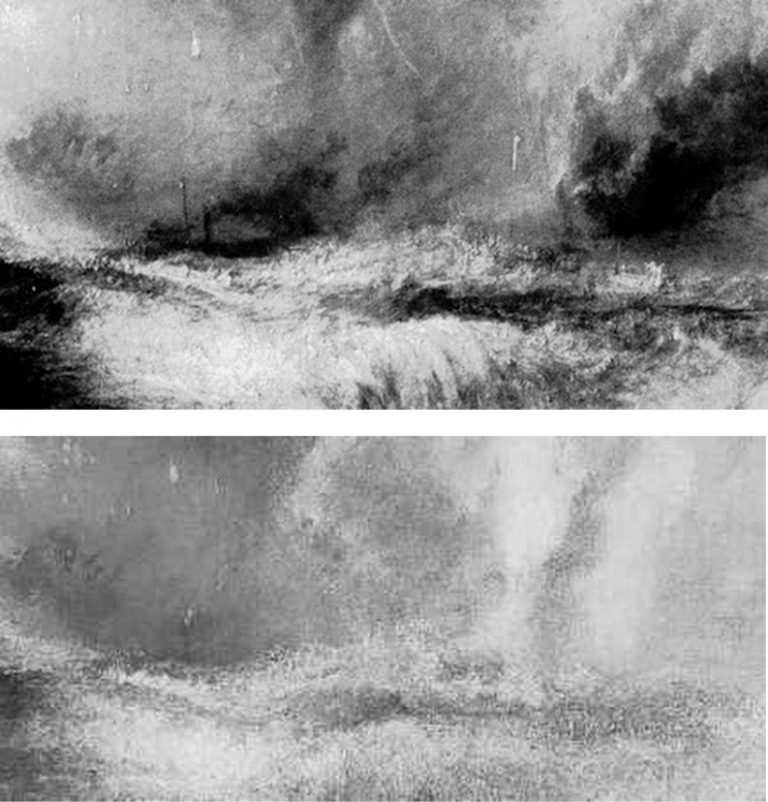

Above, Fig. 8: top, Leonardo, The Mona Lisa, oil on poplar, 77 x 53 cm, c. 1501-1517, Paris, musée du Louvre, detail of hands (infrared reflectogram hereafter referred to as IRR); below, Leonardo, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (“The Saint Anne”), 1501-1517, oil on poplar, 168.4 x 113 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, detail of Saint Anne (IRR). In Lisa’s proper right hand, delicate contour lines have been traced to define further a now imperceptible drawing transferred from a cartoon. Thanks to tiny spolvero dots appearing on some contour lines, the use of a pricked cartoon to transfer the composition is identified in the Louvre Sainte Anne distinctly, in particular in the Saint’s proper left eyelid. The scarce and very small fragments of underdrawing in the New York Salvator Mundi are not decisive towards Leonardo’s authorship given that they don’t compare the typology of the artist’s original underdrawings. Besides, the artistic level of the painting does not match that seen in visible light in the above masterpieces.

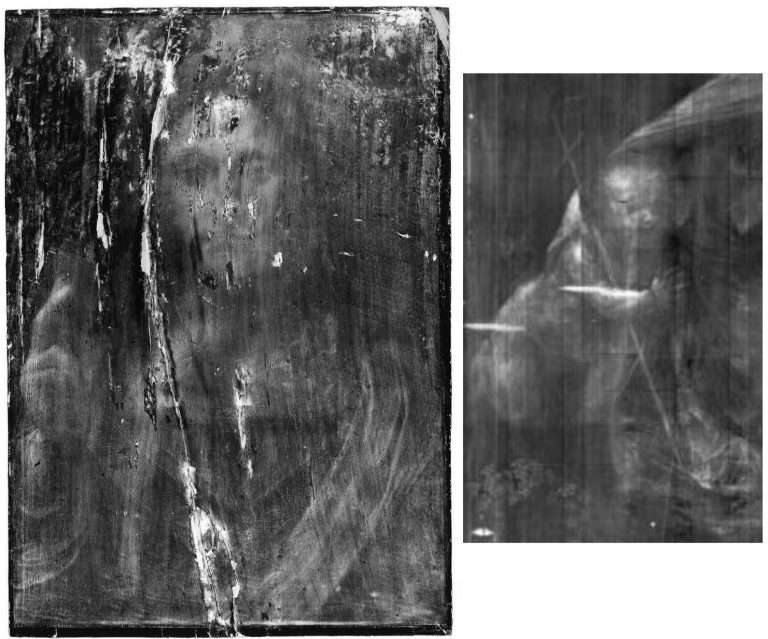

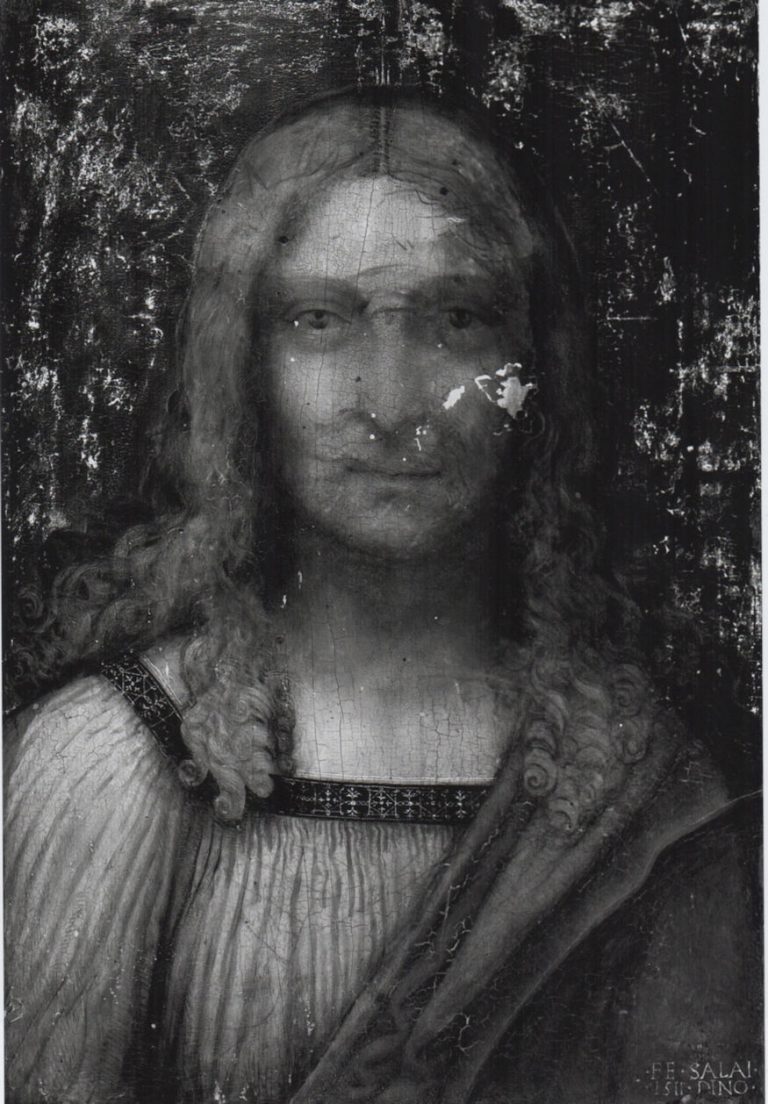

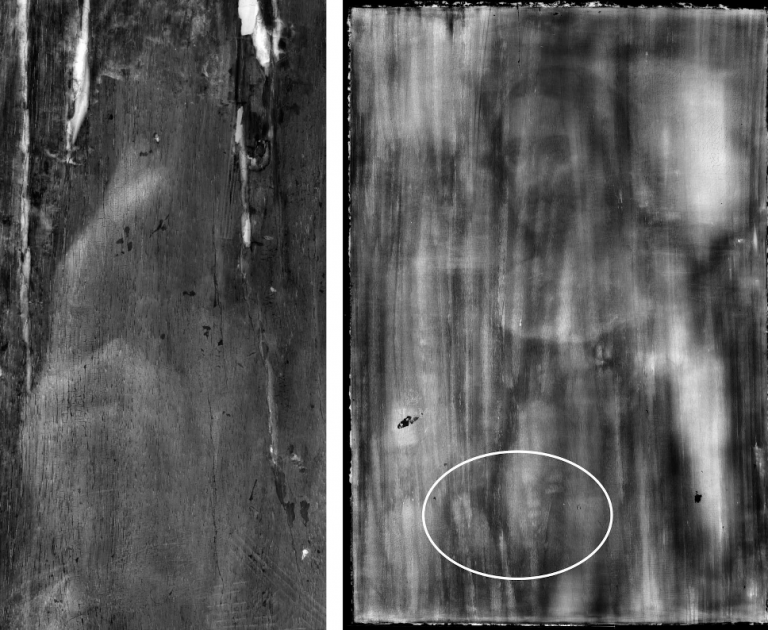

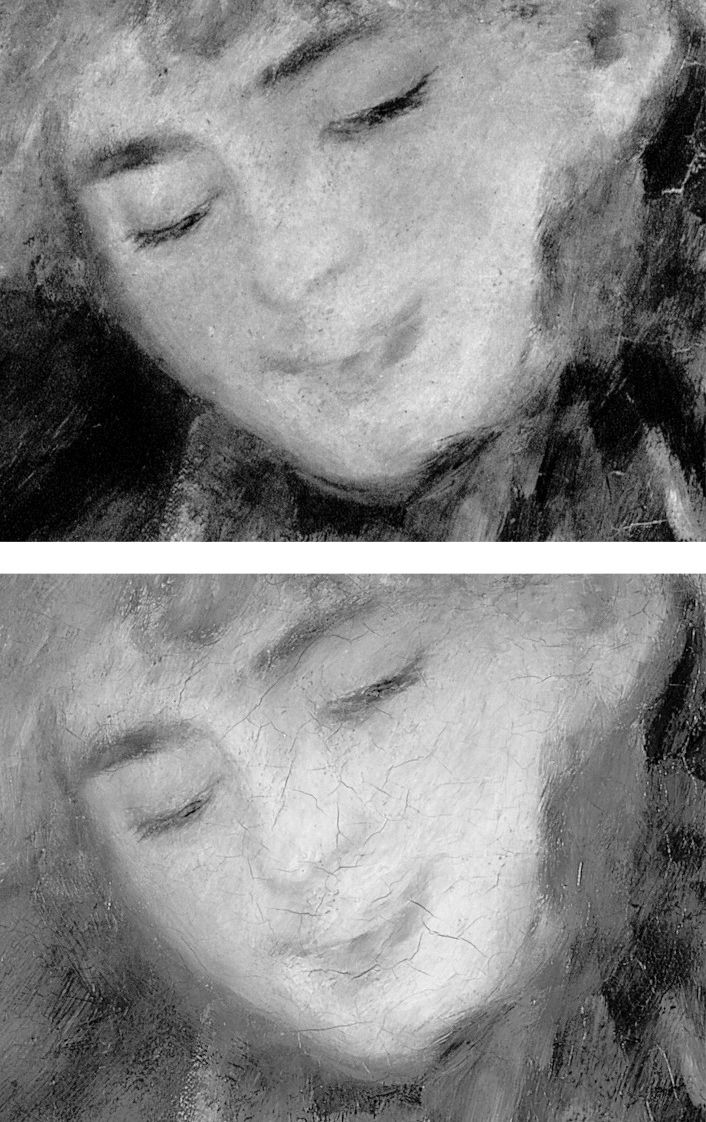

These observations are, of course, far too slight to help one figure out whether or not the Salvator Mundi‘s underdrawing compares directly with those of the late Leonardos, like the one faintly discernible, and so, just partly, in the Mona Lisa, or the one in the Louvre Saint Anne, which, conversely, is far more substantial and legible (Fig. 8, above). As already mentioned, while an excessive interpretation is drawn by Delieuvin from a barely significant item of technical information, what really matters in the infrared tests of the painting – and is therefore of far greater importance – is blatantly ignored by the three authors of the “no book”. There is a clear reason to this: the C2RMF’s infrared image is that of the restored picture, in which what is of interest does not show because the infrared rays’ deep penetration through the paint layer is stopped by the modern materials used by Modestini to reconstitute the background visually (Fig. 9, below). Fortunately, another image does exist (Fig. 10, below): it was made in 2007, before what subsists of the dark background was restored, heavily in my opinion, thus masking what is so essential in the infrared tests of the Saudi painting, that is the thick emphatic black contours of Christ’s head, shoulders and face. This crucial visual document is missing in both the withdrawn Louvre/C2RMF 2019 book and in the excellent American survey of April 2020. The significance of that image had been published in my interview in Beaux-Arts Magazine in January 2018 and for that reason, it has been known to all the parties involved closely in the Salvator Mundi‘s scientific expertise. Nonetheless, this very image does not appear either, in full at least, in Dianne Modestini’s own post-cleaning essay of 2014 on the controversial work [5]. Some details, however, especially the so fascinating one of Christ’s head, are reproduced. As the reader knows from my “Further thoughts I” posted here last year, the infrared reflectogram (IRR) of the Salvator Mundi’s background free of any inpainting reveals the amazing analogy that exists between the thick black contours of Christ’s head (a sketching-out technique never practiced by Leonardo) and those observed in a signed and dated Head of Christ, painted in 1511 by the Master’s favourite pupil and collaborator, Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called Salai (see “Further Thoughts I”, Figs. 7-11) [6]. To date, my discovery has not been commented on by those it concerns most, i. e., the various adepts at the Leonardo attribution, but it will not be kept in the background for ever.

Above, Figs. 9 A, B, and C: [A] top, workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi (IIR scan with restored background concealing the sketching out contours of Christ’s head, face, neck and shoulders); [B] below left, Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist (before the last cleaning), oil on wood, c. 1510-1517, Paris, musée du Louvre; [C] below right, The Cook version of Salvator Mundi in visible light (as in Fig. 1 above). The problem with the Modestini heavily retouched background is revealed in a clear-cut fashion when the restored stage (here, that of 2011-12, when exhibited at the National Gallery, and not yet that of 2017 when sold at Christie’s, New York) is compared visually with Leonardo’s Saint John the Baptist in the Louvre. In the latter, there is no distinct separation between light and shade. No background exists, so to speak, just an invasive obscure space within which the figure of St. John is defined thanks to the lighted zones and the transitional shading, thus resulting in an impalpable image in strict accordance with Leonardo’s quest for spatial unity between the forms and their environment, a process in which that duality is subdued extensively. In technical terms, therefore, the shadows in the background and in the foreground of the Louvre picture appear to be of the same value and “mysterious” quality. That is not the case in the Saudi Salvator Mundi: Christ’s figure is far more defined than that of St. John and clearly stands against a dark background, the shapes still have boundaries and do not float within an obscure, indefinable space like in the Louvre picture: it is an unsubtle characteristic corresponding much more to the studio’s aesthetic options observed during Leonardo’s Milanese periods of 1482-1499 and 1506/08 -1513 and for a long time after his death.

Above, Fig. 10: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi (IIR scan, 2007), before restoration, showing the heavy outlines of the underlying sketching out – unlike Leonardo’s own practice – of Christ’s head, face, neck and shoulders.

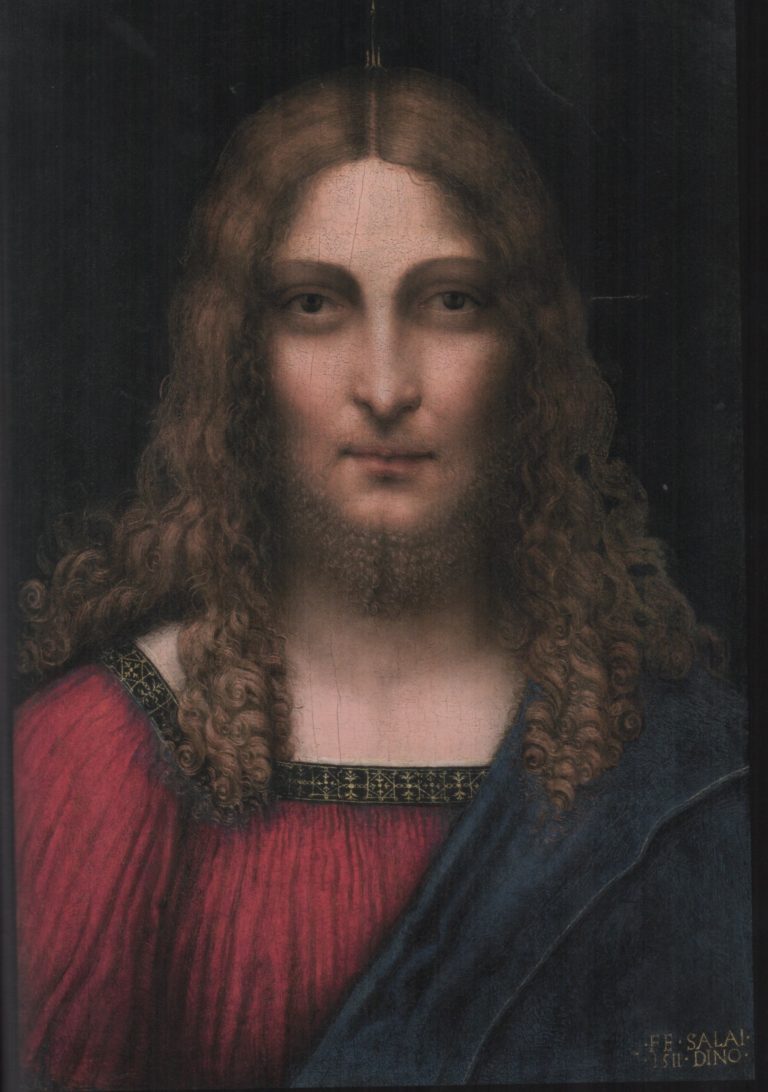

Above, Fig. 11: Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called “Salai”, Head of Christ, oil on wood, signed and dated 1511, 53 x 37.5 cm, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

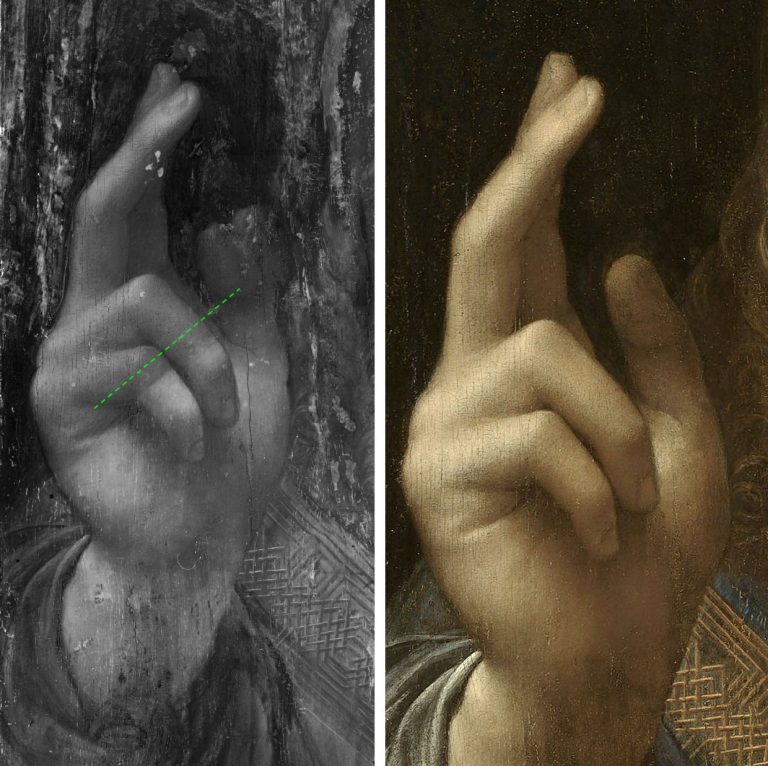

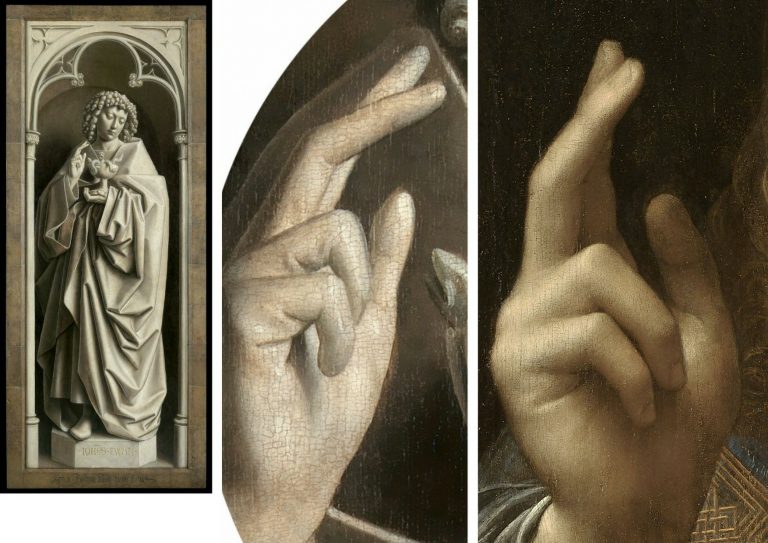

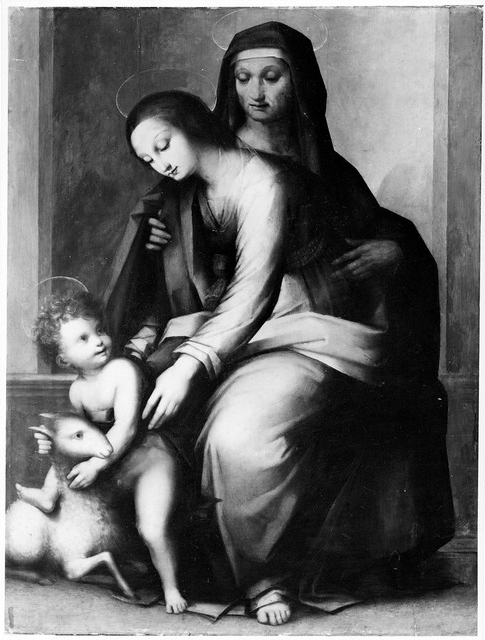

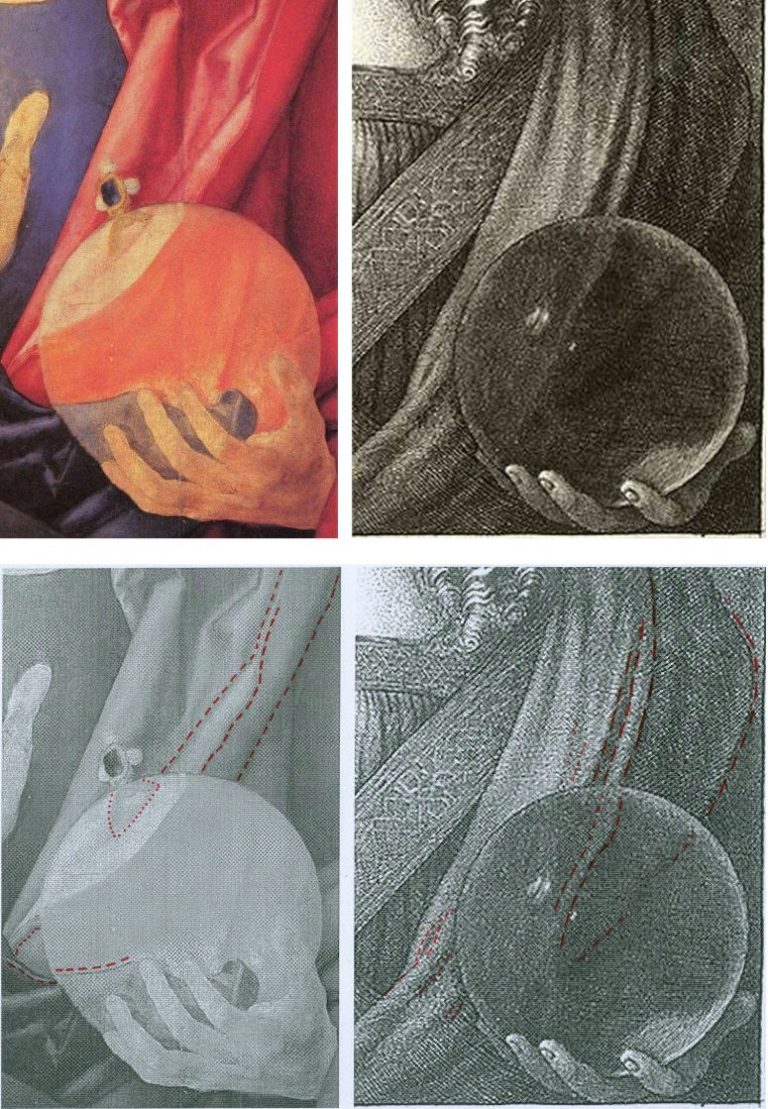

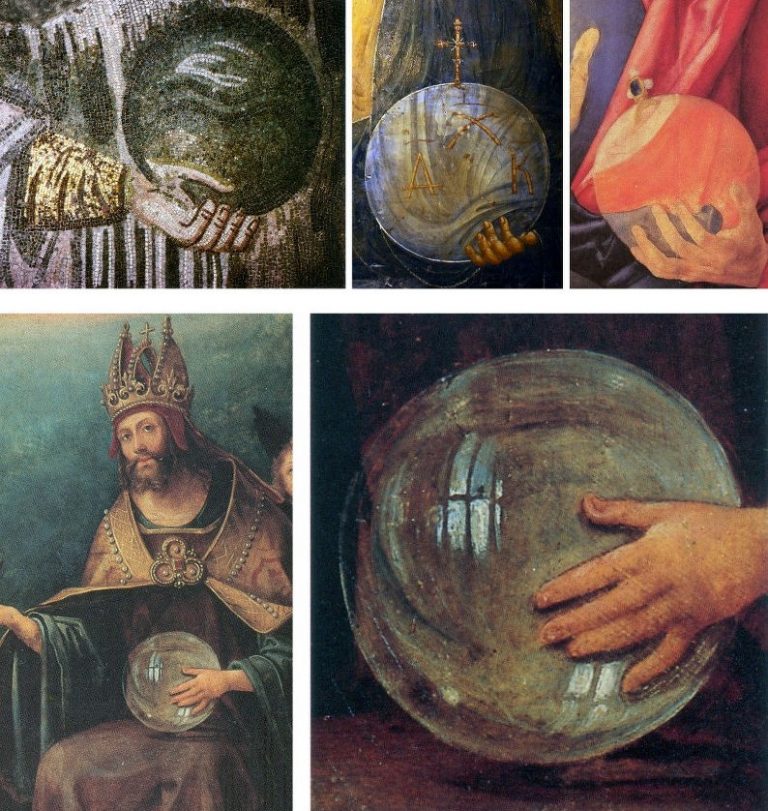

III: The blessing hand

The blessing hand is another flagrant case of extrapolated interpretation by the authors of the junked book: the elements now observed by both the C2RMF scientific team and the American one cast definitive doubt over Leonardo’s presumed contribution to the work’s execution. Still following his own line very quietly, Delieuvin seems to consider that what science reveals on that hand’s making is nothing to worry about: “Thanks to infrared reflectography, important pentimenti [autograph revisions made during the painting process] are discovered in the former Cook collection Salvator Mundi. In the proper right arm one can understand that the upper part of the blessing hand has been painted over a black background, thus proving that Leonardo had not planned it at the beginning of the execution. It seems that the artist had started working on a different composition, with no blessing arm, possibly like in Salai’s [Head of Christ] in the Ambrosiana” (Delieuvin, 2019, p. 14), (Figs. 11, 12 and 13.)

Above, Fig. 12 [after Rieppi, Price, Sutherland et al., 2020, Fig. 3]: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, cross-section sample from flesh highlight showing, left: (1) ground, (2) imprimitura, (3) black background paint layer, (4) flesh highlight paint layers. The backscattered electron (SEM-BSE) image – right – shows coarse glass particles in layers 1-4. The black background paint layer underlying the flesh highlight is clearly visible here: it does not correspond to any recorded Leonardo practice.

Above, Fig. 13: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail: IRR scan image showing the black background seen through the translucent flesh paint of Christ’s right proper hand (along green dotted line); right, the proper right hand, after restoration and in visible light.

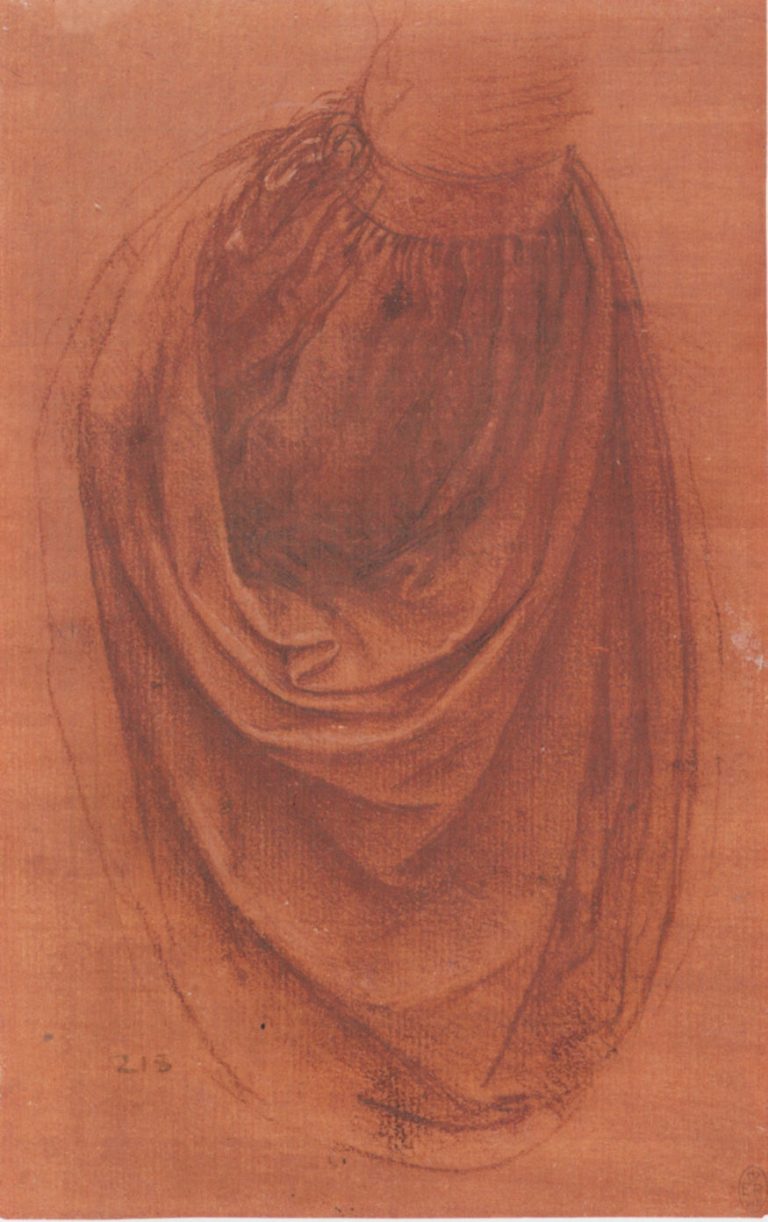

That, of course, is not the interpretation that should be drawn from this extraordinary discovery in order to respect both technical and historical accuracy: a pentimento, a word meaning “repentance” or “regret” in Italian, is an action, while being an adjustment or correction, that is consistent with the composition as it was conceived by the artist at the outset. From this standpoint, Delieuvin is right in considering that the initial composition of the Cook Salvator Mundi was identical to that of Salai’s Head of Christ in the Ambrosiana: it is the more certain as the black background was, if not finished, largely painted around the Saviour’s head and down his proper right shoulder when the blessing hand was added (as shown on the infrared documents and the cross-section sample reproduced here (Figs. 10, 12 and 13, above). We are therefore faced with a change stricto sensu, because, in chronological terms the pentimento is executed during the painting sessions inherent of the initial creation, thus within one and the same artistic logic of forms that were born together, whereas a change – or transformation – of composition and iconography is not: it radically modifies the initial composition’s outward appearance and can occur at any time, whether early or late, after that composition was left as it first was. In many cases, it may well be an autograph move and, consequently, not necessarily the sign of a late, apocryphal addition, yet in that of the controversial Salvator Mundi, its authenticity can be doubted insofar as the blessing hand’s gesture, anatomy and perspective are so wrong that Leonardo’s authorship seems improbable. What cannot be established, however, is the moment when the change took place, despite the C2RMF’s attempt to prove (on unconvincing grounds) that it is in Leonardo’s hand and soon followed the abandoned original idea (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 32). Also, it is worth of note that, interestingly, while Christ’s tunic and proper left sleeve are drawn carefully in the Windsor studies RL 12524 and 12525 (see “Further thoughts I”, figs. 2 and 3), no hand was conceived by Leonardo, whether sketchily or not on the latter sheets, or even traced on a separate one. The hand holding the orb has not been projected either. It strengthens my feeling that those projects were meant for the studio as a guideline for the figure’s clothing alone, and so without reaching a stage including the hands, thus suggesting that the assistants were left on their own for the execution of the whole painting (hence the stiffness observed in most parts of the drapery work and the weak, ill-depicted anatomy of the hands).

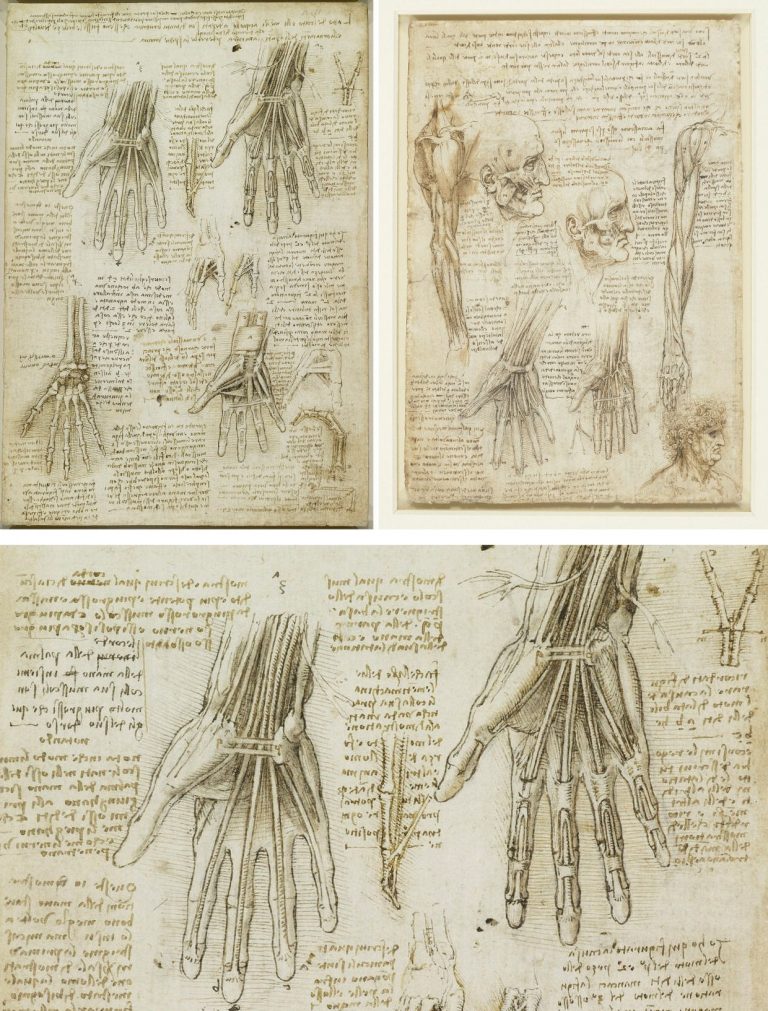

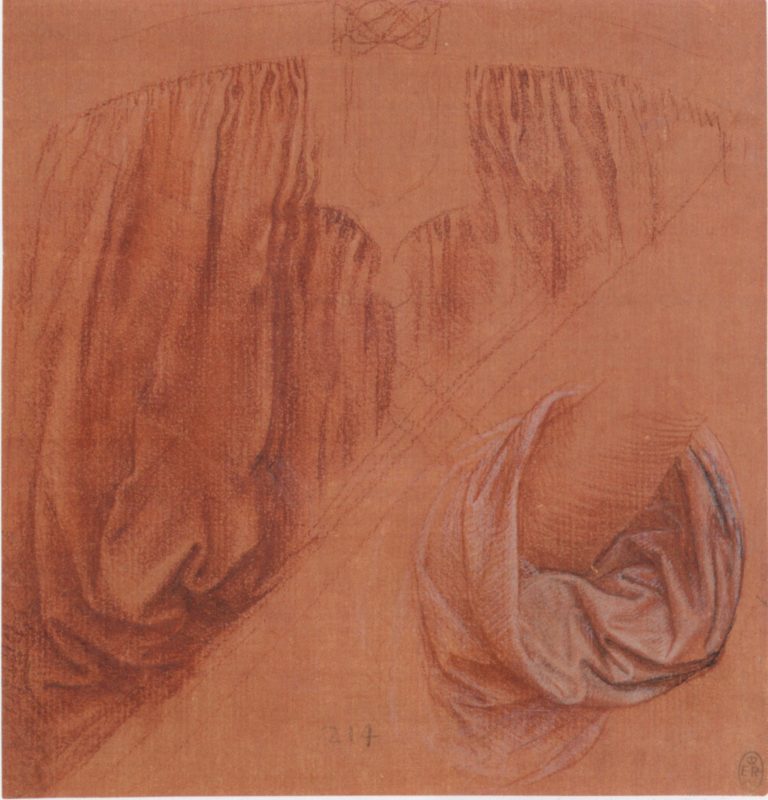

Above, Fig. 14: top, left, Leonardo, The bones, muscles and tendons of the hand, c. 1510-1511, pen and ink with wash, over black chalk, 28.8 x 20.2 cm, Windsor Castle, Royal Library, RL 19009r; top right and, above, detail, Leonardo, The muscles of the face and arm, and the nerves and veins of the hand, c. 1510-1511, pen and ink with wash, over black chalk, 28.8 x 20 cm, Windsor Castle, Royal Library, RL 19012v.

At this stage, it seems helpful to provide historical elements demonstrating Leonardo’s incredibly deep knowledge of the human hand, of its anatomy and functioning. As the reader will see, acknowledging the mass of work and the so pertinent observations contained in the artist’s research on this issue alone, is the best way to realize that the Cook Salvator Mundi’s blessing hand does not accord with Leonardo’s anatomical concepts and depictions: “The principal movements of the hand are 10; that is, forwards, backwards, to right and to left, in a circular motion, up or down, to close and to open, and to spread the fingers or to press them together” (Codex Atlanticus, folio 124v (45v-a), Richter, § 353, c. 1515- 1516). And again: “[Of the motions of the fingers] The movements of the fingers principally consist in extending and bending them. This extension and bending vary in manner; that is, sometimes, they bend altogether at the first joint; sometimes they bend, or extend, halfway, at the 2nd joint; and sometimes they bend in their whole length and in all the three joints at once. If the 2 first joints are hindered from bending, then the 3rd joint can be bent with greater ease than before; it can never bend of itself, if the other joints are free, unless all three joints are bent. Besides all these movements there are 4 other principal motions of which 2 are up and down, the two others from side to side; and each of these is effected by a single tendon. From these there follow an infinite number of other movements always effected by two tendons; one tendon ceasing to act, the other takes up the movement. The tendons are made thick inside the fingers and thin outside; and the tendons inside are attached to every joint but outside they are not” (Codex Atlanticus, folio 273a recto (99 v-a), Richter, §354, c. 1510).

As one can see, Leonardo’s disquisition on finger movements rules out anything other than bending along a plane for each finger and provides no rotary option for any of them. To perfect the Master’s own demonstration, I have reproduced here (Fig. 14, above) two magnificent drawings of the anatomy of the hand kept in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle: beyond any discussion they prove that the artist who painted Christ’s blessing hand with something like a broken raised finger (it rotates clockwise, thus suggesting such a traumatic pathology) in the Cook Salvator Mundi cannot be the one who drew the genius sheets in Windsor. But why then such a hand? Although it is difficult to answer that question, I have long suspected that its overall concept and shape does not have an origin in Leonardo’s bottega and that its pattern, more precisely that of the “broken finger”, seems to correspond to an archaic style, thus medieval, and possibly to a Northern school artist. Whether right or not, this presumption is somehow confirmed by the right proper hand of Saint John the Evangelist in Jan van Eyck’s polyptych of the Mystic Lamb (1432), a grisaille painting at the back of a shutter of the work, where appears the same anomalous raised finger as seen in the Cook Salvator Mundi and in its numerous variants (Fig. 15, below). Neither Leonardo nor any of his close collaborators ever saw the Ghent altarpiece but this hand could well be a prototype copied from model-books by travelling artists who had circulated in Europe throughout the 15th century and had brought it to Italy at some unspecified moment. At the time the Cook Salvator Mundi was painted (c. 1510?), Leonardo was far too skilled an anatomist and an innovator to have taken any notice of such a model, but it might have been imitated while modernized by a less brilliant artist like Salai, who had spent his life in the Master’s orbit and never created anything of his own. Once again, this issue cannot be considered supportive of the Leonardo attribution. Moreover, as we shall now see, other disqualifying archaisms exist in the painting.

Above, Fig. 15: left, and centre, Jan van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece (The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb),1432, oil on wood panels, 3.4 m x 4.6m, Ghent, St Bavo’s Cathedral, showing Saint John the Evangelist, 148. 7 x 55. 3 cm, and in detail, the blessing hand; right, the restored hand in the Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi. In truth, Van Eyck’s raised middle finger is less twisted, and hence less faulty, than that in the Saudi Salvator Mundi, but its perspective is nevertheless wrong: the nail should not show so much and be in full profile instead, if at all. Also, the lower part of the finger tip should be seen more from underneath.

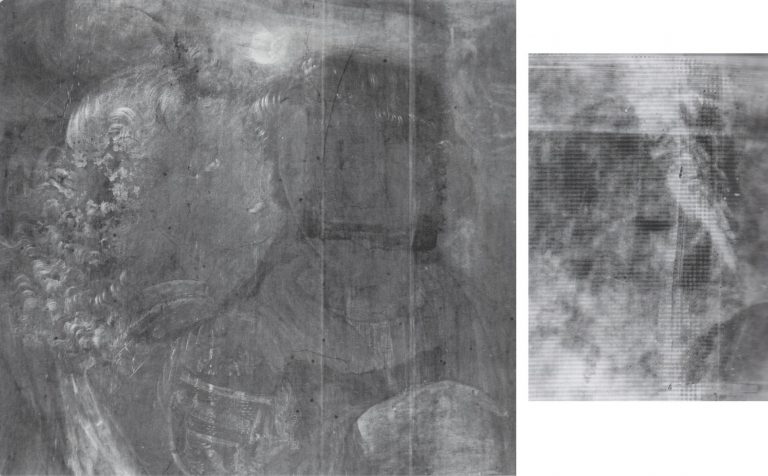

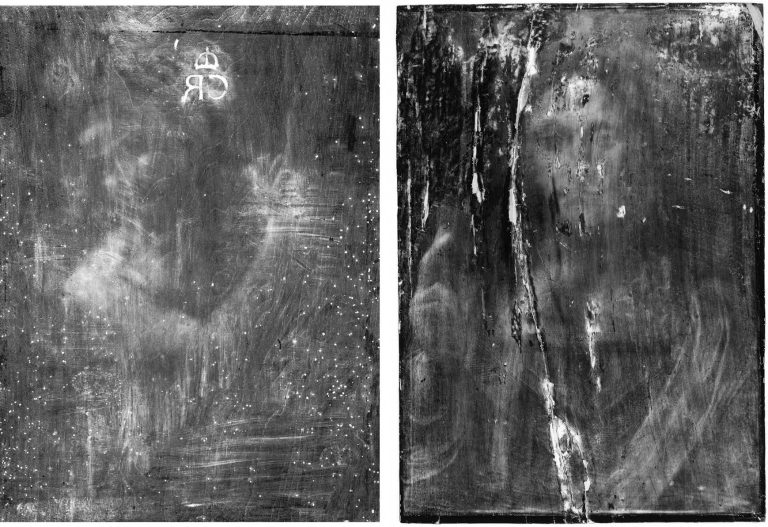

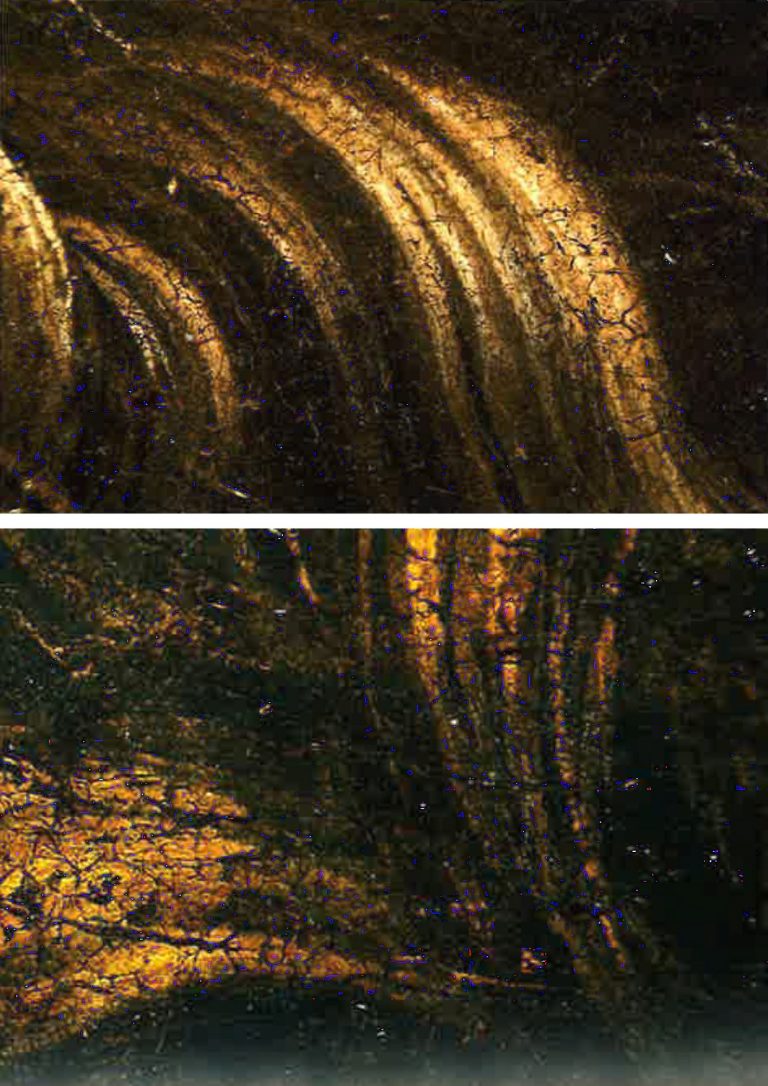

IV: (A) X-ray testimony, (B) Christ’s curls

Another case in point is the typology of the X-radiograph image of the panel painting, which is also described in a tendentious manner that would leave no doubt about the work’s authenticity: “The X-radiograph of the picture displays the same ghostly image as is seen in the Saint Anne, the Mona Lisa and Saint John-the-Baptist, which is a typical feature of Leonardo’s works after 1500” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019, p. 38).

(A) – Once again, the reader is supplied with no contextual information that would otherwise disclose its arbitrariness. To my knowledge, no systematic and critical survey has been undertaken until now on the X-ray images of the Leonardos of that period with regard to X-rays of the studio’s productions, which exercise proves highly instructive (see below). Besides, the X-ray images of Leonardo’s own paintings, whatever the period of their creation, show a great variety of aspects depending, firstly, on the nature of the preparation, and secondly, on the particular technique used in the coloured layers of the paint film, and this is most especially the case in the flesh sections. For example, from roughly 1500 onwards Leonardo uses less and less lead white in the flesh paints of his figures, which abstemiousness results in the pictures’ ghostly looking radiographs whose aspect is very different from those of earlier works like the Lady with an Ermine (c. 1490) or the Belle Ferronnière (c. 1495). In the latter, the use of lead white was substantial. However, in Leonardo’s case such matters should not be simplified according to his oeuvre’s chronology : unexpectedly, one can see a marked similarity between the blurred, practically illegible X-radiograph of the head of Leonardo’s Angel in the Baptism of Christ (1472-1475) and that of Saint Anne in the Louvre’s Virgin and Child with Saint Anne painted thirty years later (c. 1501-1517), (Fig. 16, below).

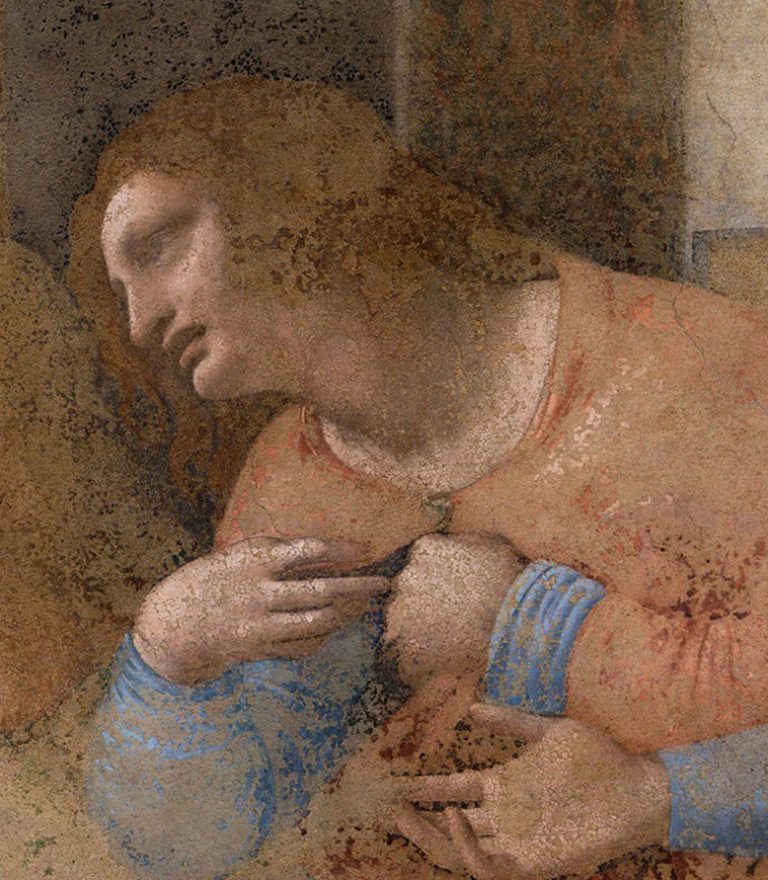

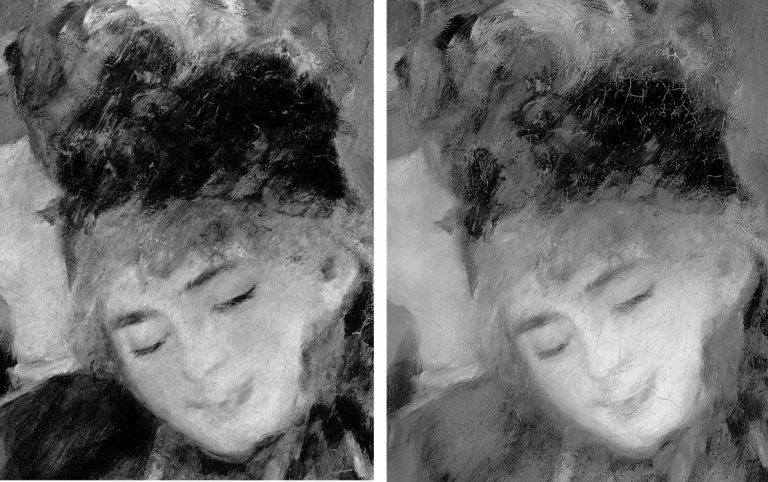

Above, Fig. 16: left, Verrocchio and Leonardo, The Baptism of Christ, before 1470/ 1472 -1476 (?), tempera and oil on poplar, 177 x 151 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, X-radiograph of Leonardo’s Angel’s head (painted in oils); right, Leonardo, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, oil on poplar, 168 x 130 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, X-radiograph of Saint Anne’s head.

Above, Fig. 17: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, X-radiograph; right, Leonardo and studio (including G.A. Boltraffio), The Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1493-1499 (?)/1506-1508, oil on poplar, London, National Gallery, 189.5 x 120 cm, X-radiograph of the Infant Saint John.

Above, Fig. 18: left, Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist, c. 1510-1517, oil on walnut p, 69 x 57 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, X-radiograph; right, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, X-radiograph. In the X-radiograph of the Louvre Saint John the Baptist, one’s eye can grasp but few elements of the composition as seen in visible light (the pointing hand is illegible and the Saint’s austere garment doesn’t show at all), whereas Salvator Mundi’s X-ray image is much more consistent with the work’s aspect in visible light.

As just suggested, unless it were to be studied in the future by a cross-disciplinary team closely and rationally, this X-ray issue remains unclear and susceptible to misinterpretation. For myself, I have noticed through years of examination of the X-radiographs of Leonardo’s original paintings in the Louvre that none of them displays an image entirely consistent with that seen in direct light: when one or more details of the work can be identified on the radiograph without problem, the rest is not. In other words, the relating compositions are at best partly legible, not more. This is not the case with the Cook Salvator Mundi, whose X-ray image is misty indeed, yet reasonably consistent with what the painting looks like in day light, a legible aspect due to a very regular and even distribution of lead white over the whole composition, used for shaping and modelling in a conventional, unimaginative fashion. This resembles the use of lead white encountered in what is considered to be Boltraffio’s brush in the London National Gallery’s Virgin of the Rocks (Fig. 17, above). In contrast, in Leonardo’s X-rayed brushwork the use of lead white appears both spontaneous and random, with no lead white where one would otherwise expect it. To me this is exactly where stands the subtle, yet distinct border between the Master and his assistant(s) (Fig. 18, above).

Adding a touch of complexity to this appeal for caution with regard to the interpretation of X-ray documents close to Leonardo and his circle, the noteworthy fact stands that, in terms of typology, the X-radiographs of Salai’s Head of Christ and that of the Ganay version of Salvator Mundi are not legible at all and, in some ways, resemble the X-radiograph of the Louvre Saint Anne (Fig. 19, below).

Above, Fig. 19: left, Gian Giacomo Caprotti, called “Salai”, Head of Christ, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, X-radiograph; centre, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, the Ganay version of Salvator Mundi, oil on walnut, 68. 2 x 48.2 cm, Private Collection, X-radiograph; right, Leonardo, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, Paris, musée du Louvre, X-radiograph.

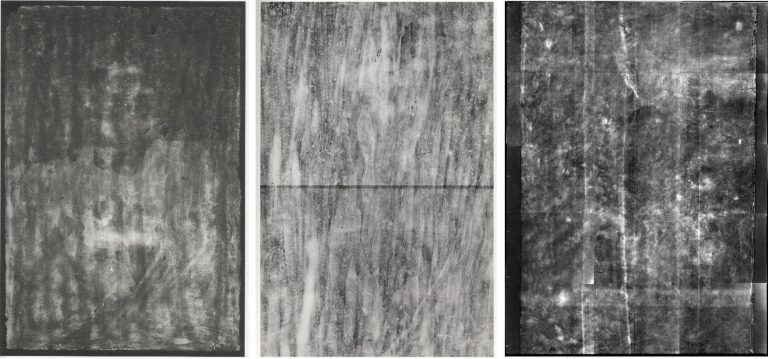

Above, Fig. 20: details, left, Leonardo, Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1474-1475, tempera and oil on poplar, 38.8 x 36.7 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art, detail of hair; centre, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail of hair; right, Verrocchio and Leonardo, The Baptism of Christ, Florence, tempera and oil on poplar, c. 1468 – 1470/ 1472 – 1475 (?), 177 x 151cm, Uffizi Gallery, detail of Leonardo’s Angel’s hair.

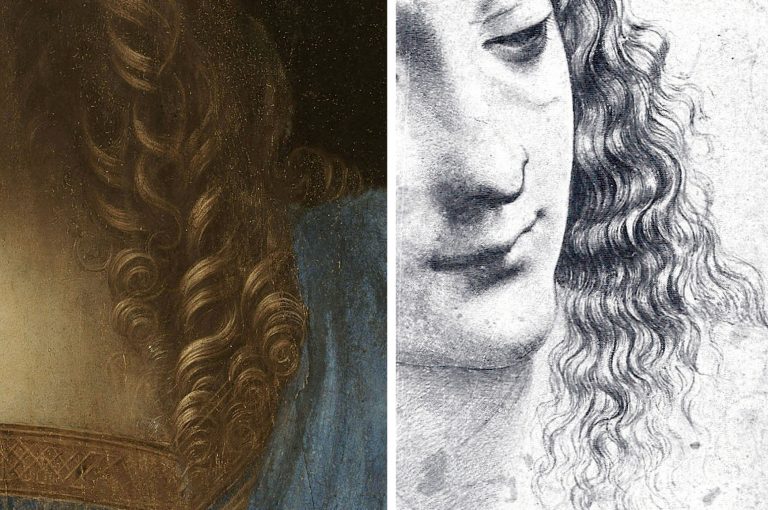

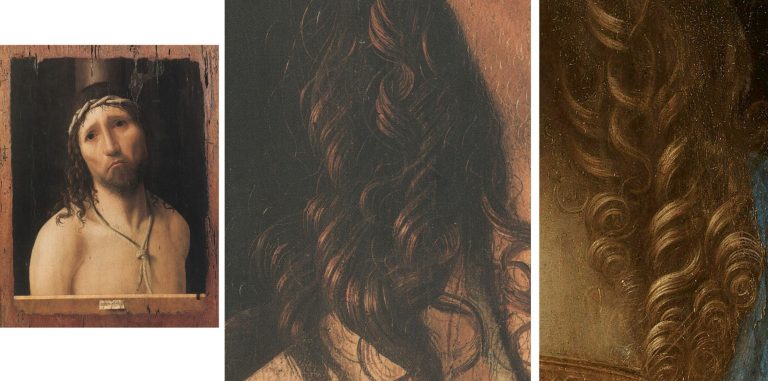

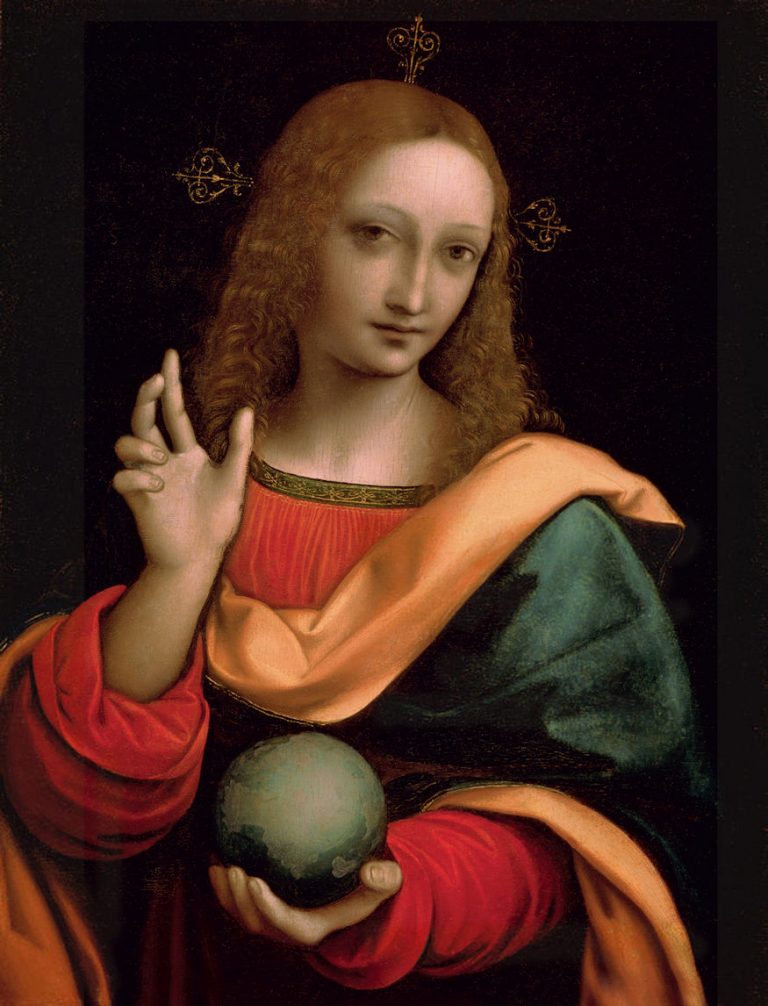

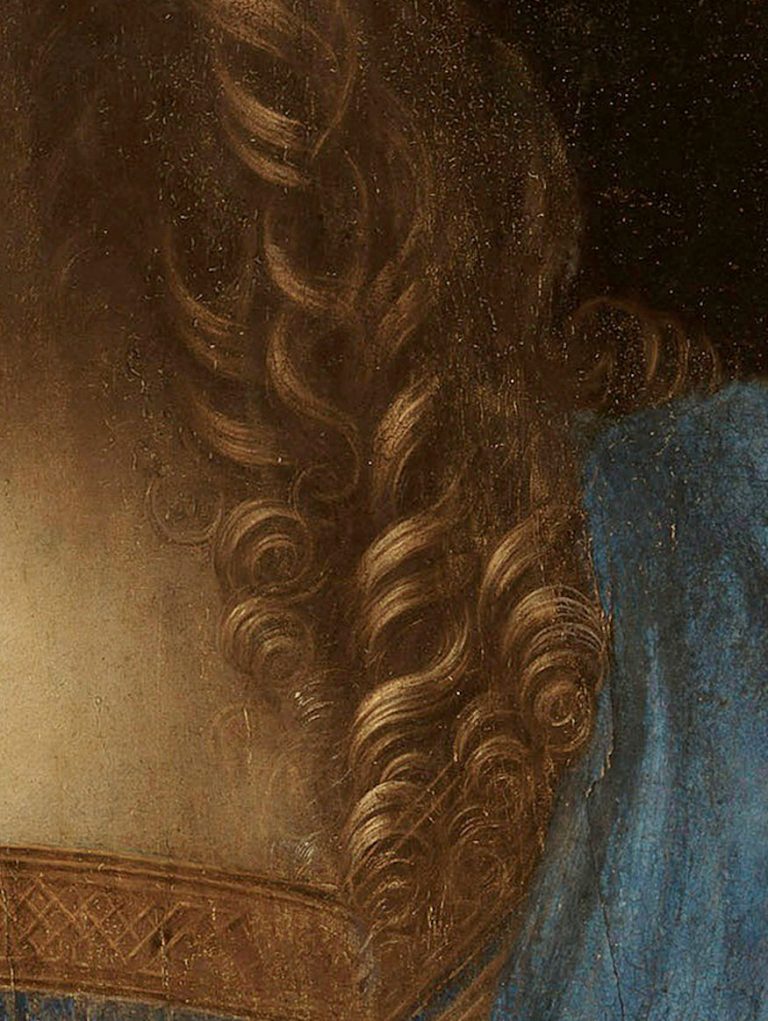

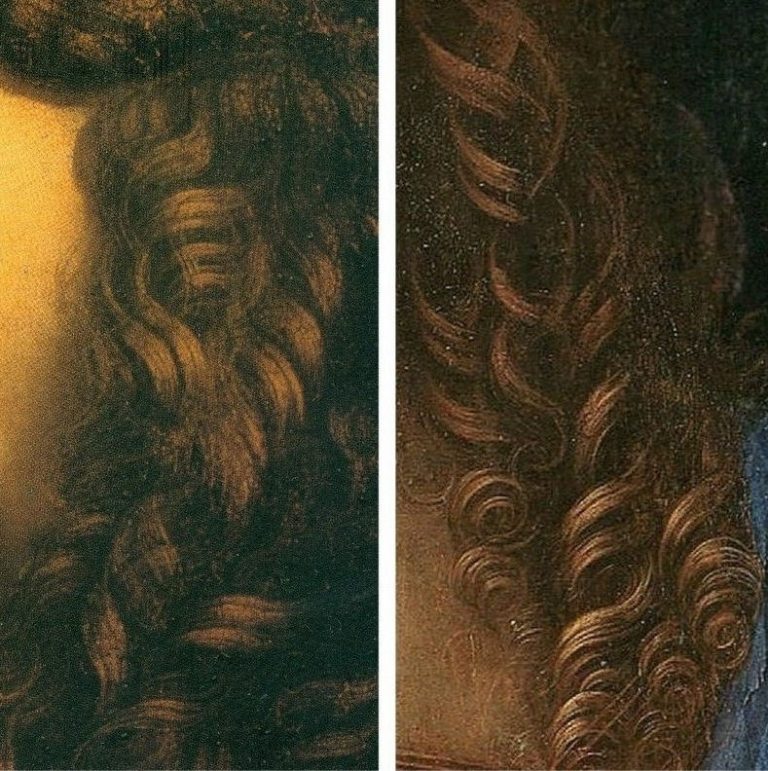

(B) – The book’s authors’ espousal of Christ’s ringlets – which they compare to Leonardo’s superb hair in the Louvre Saint John the Baptist – is also disconcerting for many reasons. “The curls falling on [Christ’s] proper left shoulder are rendered lavishly (…) Their technique is reminiscent of those of Saint John-the-Baptist in the Louvre.” (Delieuvin, 2019 p. 16) “The hair is partly damaged and the best-preserved zones are the curls falling on the proper left side of Christ’s face (…) The very fine execution of these curls is remarkable and is reminiscent of [Leonardo’s] Saint John the Baptist’s magnificent curls” (Eveno and Ravaud, 2019 p. 34 -36).

The curls in question are certainly painted with extreme delicacy but are they really reminiscent of the Saint’s hair in the Louvre Saint John? Not really, in my opinion, for the style of these ringlets, not only does not resemble the hair executed by Leonardo in his late period, it is nowhere seen in any of his paintings except, perhaps, for a slight resemblance to the permed ringlets in the Portrait of Ginevra de Benci, which picture, however, dates to c. 1475 (Fig. 20). Such a period rules out the possibility that Leonardo would have gone back to his early Florentine style, as best perceived in his Angel in the Baptism of Christ, to paint the Cook Salvator Mundi’s ringlets of c. 1505-1510. The latter’s otherwise systematic and careful treatment (in the fine passages) induces my feeling that Boltraffio’s brush is not strange to their precious chiselling (Fig. 21, below), which, oddly, resembles an earlier style in the treatment of hair, such as that executed in a somehow close technique in Antonello’s Ecce Homo of 1475 in Piacenza, as at Fig. 22, below.

Above, Fig. 21: left, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail of hair; right, G. A. Boltraffio, Study for the heads of a Madonna and Child, silverpoint on paper, 29. 7 x 22 cm, Chatsworth, Duke of Devonshire and Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, detail of Madonna’s hair.

Above, Fig. 22: left, Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo, 1475, oil on wood (oak?), 48.5 x 38 cm (painted area 43 x 32. 4 cm), Piacenza, Collegio Alberoni; centre, Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo, detail of hair; right, detail of hair from the Cook version of Salvator Mundi. The painting technique employed in Salvator Mundi’s hair by Leonardo’s assistants c. 1510 is close to that of curly hairs executed by Antonello thirty-five years earlier.

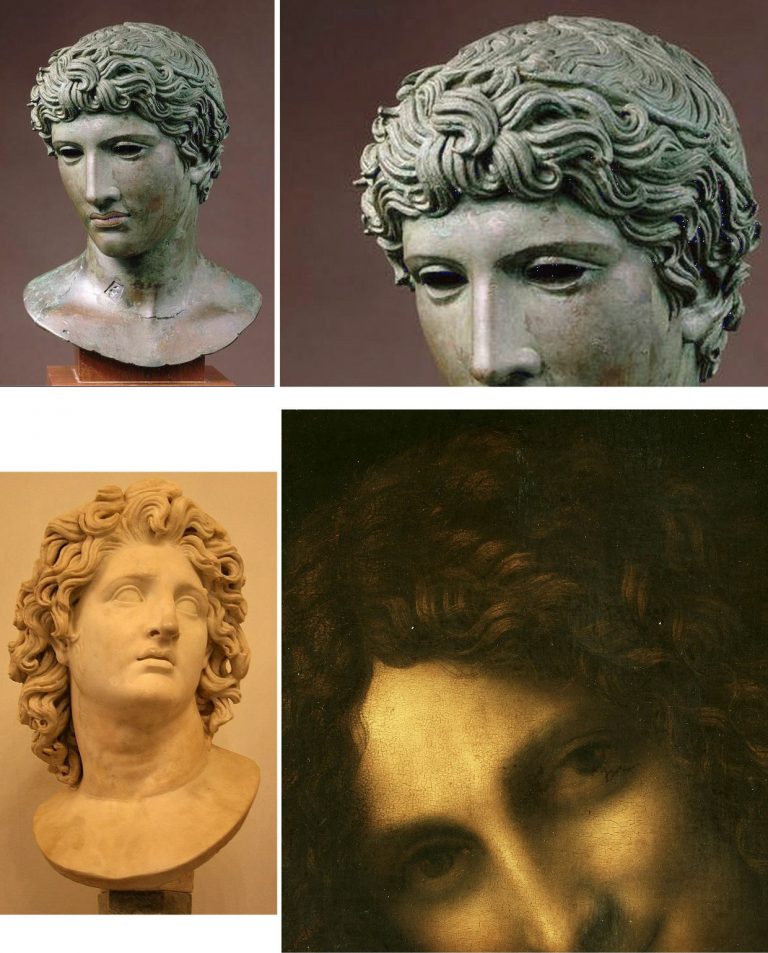

Above, Fig. 23: top left and right, Herculaneum, Campania (Southern Italy), Head of a Youth (“The Benevento Head”), 50 BC, hollow-cast bronze with red copper veneer and inlaying, H. 33cm, Paris, musée du Louvre; below left, Alexander the Great as Helios, marble, Roman copy after an Hellenistic original from 300-200 BC, H. 58. 3 cm, Rome, Musei Capitolini. Below right: Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist, musée du Louvre, detail of hair.

In truth, the overall conception of Saint John the Baptist’s hair is far stronger and more masterly than that in the Salvator Mundi: its interweaving of the locks in complex snake-like waves is of a breath-taking beauty, and its originality, nowhere else then seen in Western art, testifies unquestionably to Leonardo’s close study of the Antique. Effectively, among many examples that could prove my point, The Benevento Head (c. 50 BC, Louvre) – as above at Fig. 23, top – or Alexander the Great as Helios in Rome (a marble copy apparently executed under the reign of emperor Hadrian) as above at Fig. 23, below left, both give an idea of the artist’s concerns with the Hellenistic and Roman sources determining his late style, although their perfect assimilation results in a formula entirely detached from any plagiarism. It is therefore evident that the somehow late Gothic touch that still survives in the Salvator Mundi’s well-arranged curls is symptomatic of a Leonardo imitator from his close circle.

Above, Fig. 24: top, Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio?), the Cook version of Salvator Mundi, detail of hair viewed under optical microscope; above, Leonardo, Saint John the Baptist, Paris, musée du Louvre, detail of hair viewed under optical microscope.