IN THEIR OWN WORDS: No. 3 [11 March 2018] – The Reception of the First Version of the Leonardo Salvator Mundi

Mounting concerns over transparency in art world deals are throwing back-dated light on the Salvator Mundi’s reception in its first-restored incarnation when included in the 2011 National Gallery exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI’S FIRST PUBLIC OUTING IN 2011

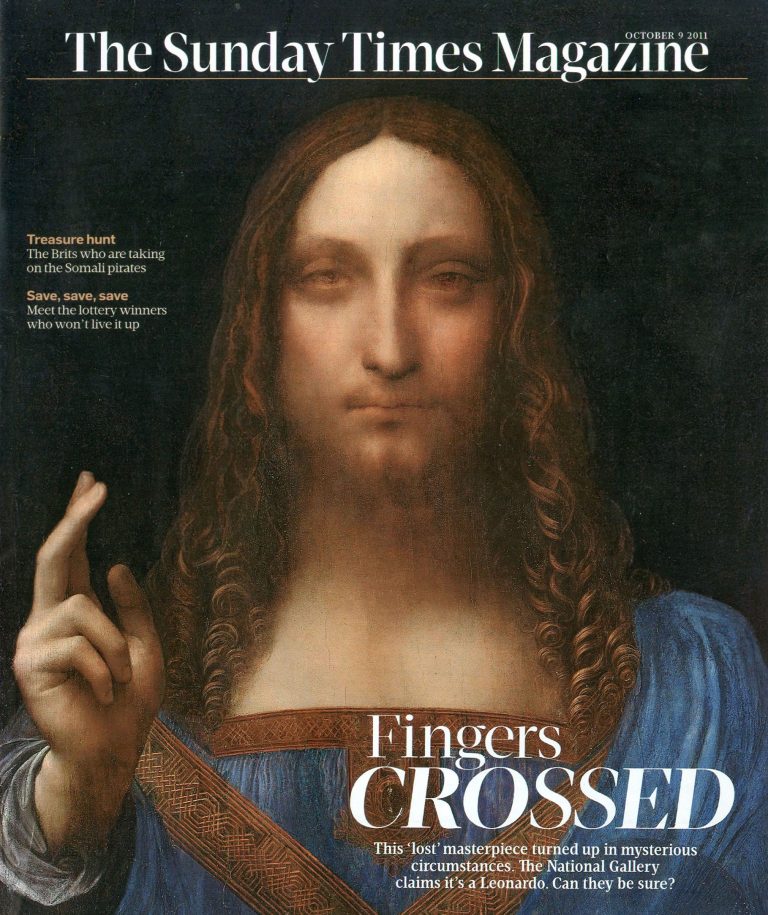

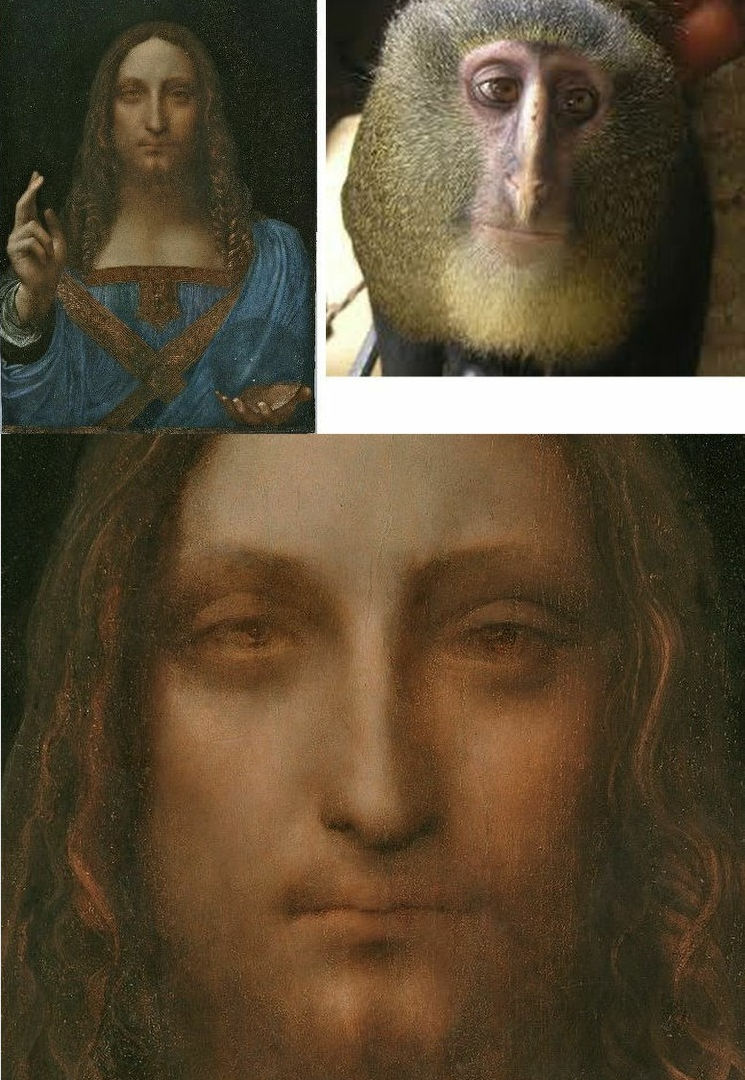

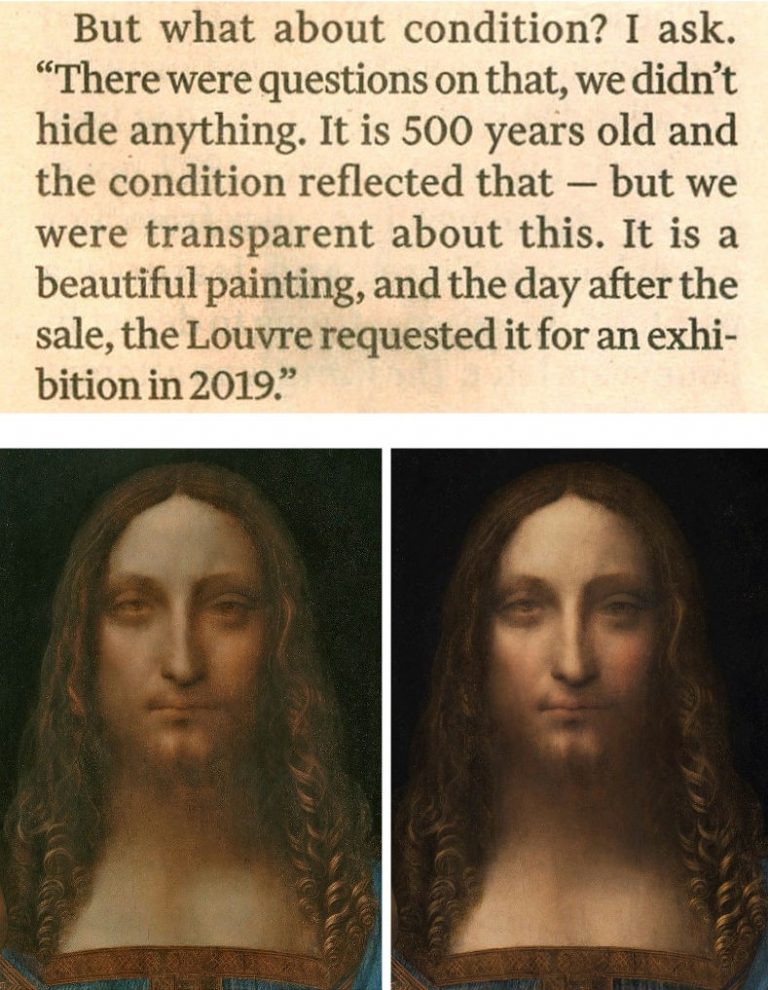

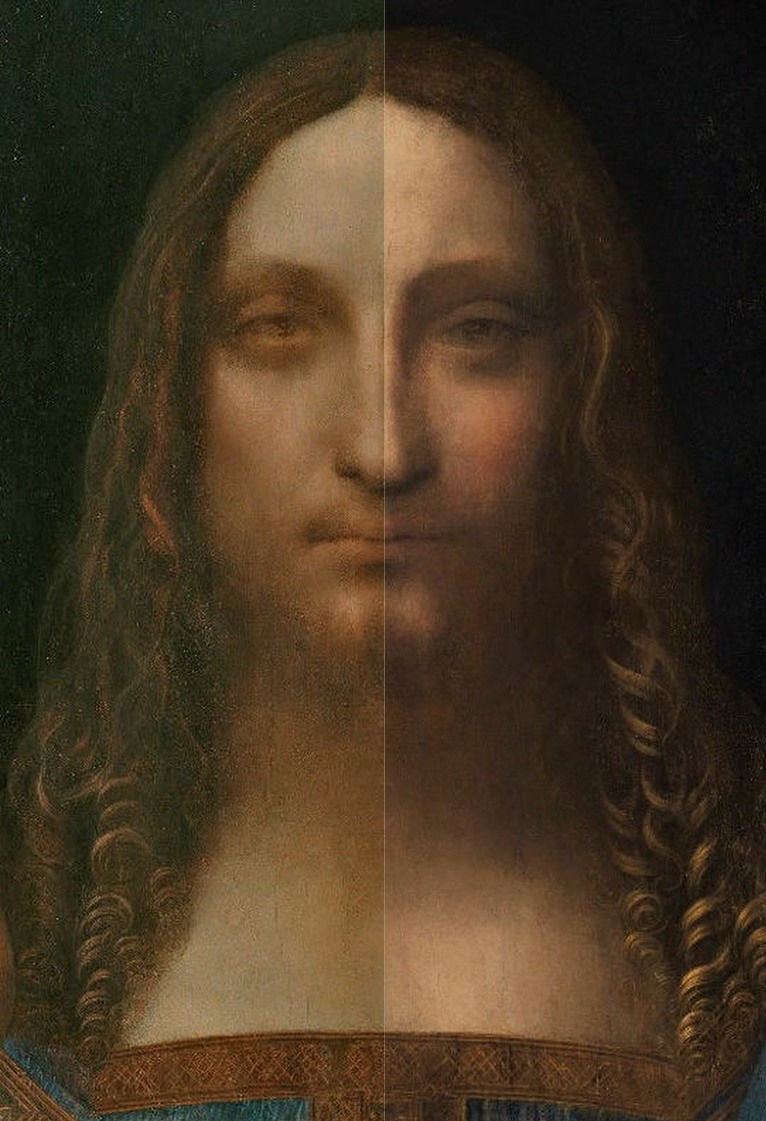

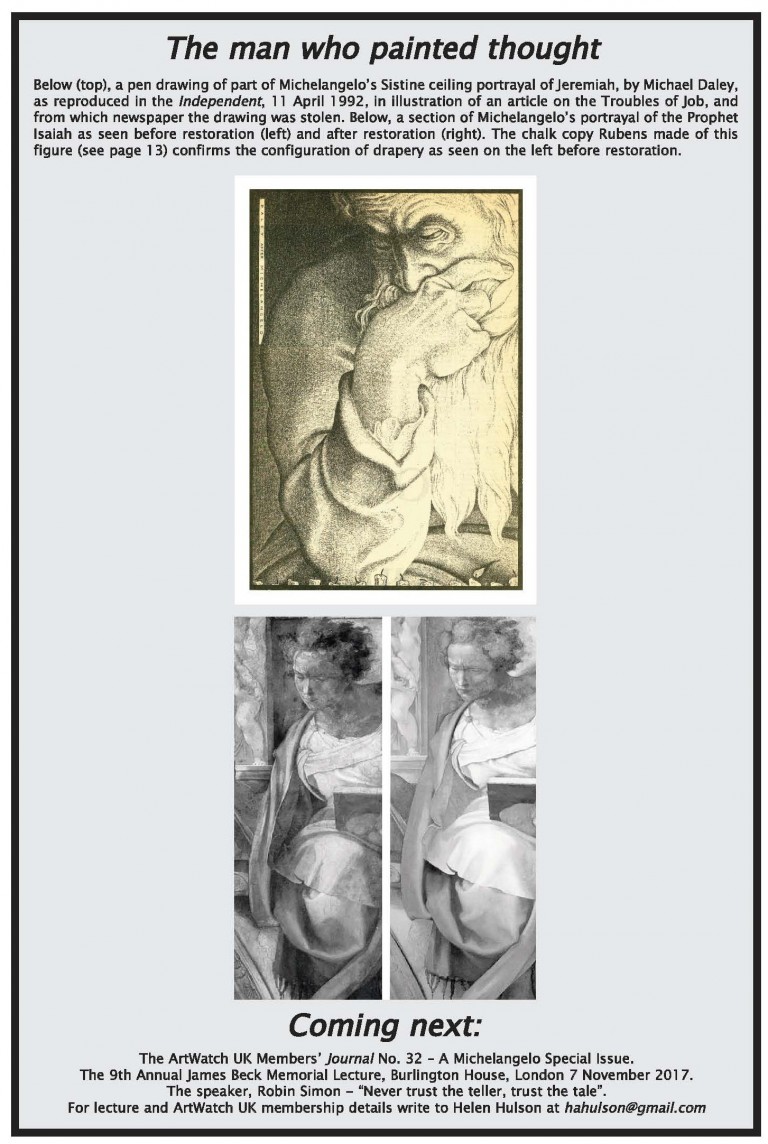

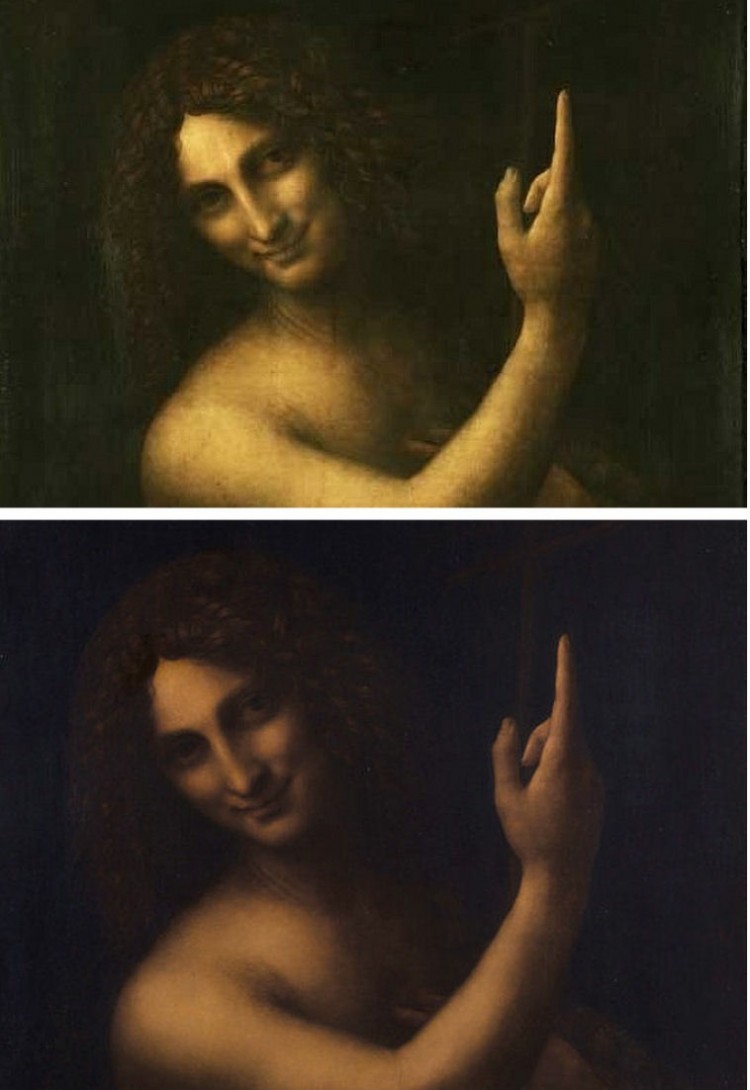

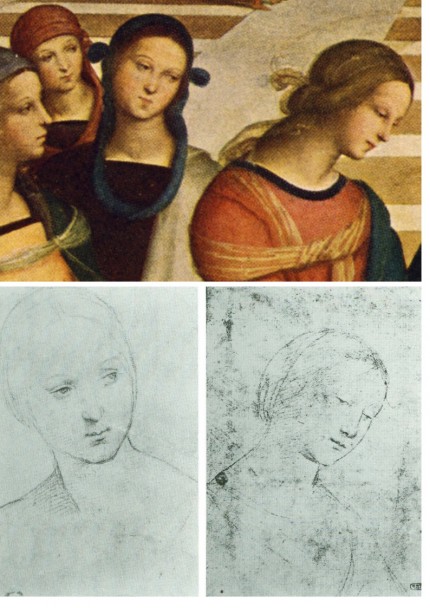

Above, top, the Sunday Times magazine cover of 9 October 2011. Above, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen after repainting in 2011, left; above, right, the face of Christ in the Salvator Mundi as seen in November 2017 after further repainting between 2012 and 2017.

In the 9 October 2011 Sunday Times (“LEONARDO? CONVINCE ME”), Kathy Brewis wrote:

“For a few weeks in London you will be able to see the Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World) up close. It might be your only chance. Much of the painting’s history remains obscure. Its ownership is a closely guarded secret. Robert Simon, a New York art dealer, is representing the owner or owners – the official line is it is a ‘consortium’. Why all the secrecy? ‘It’s just privacy and security’, says Simon, ‘One doesn’t want people knocking on the door.’

“…He showed it to Mina Gregori, a retired professor at Florence University, who was stunned: ‘I believe it’s by Leonardo.’ Then he showed it to Nick Penny, who had just been appointed director of the National Gallery. ‘He understood it in a nanosecond. He said that one of his ambitions was for the gallery to be a venue for scholarly inquiry and research and that he’d like the painting to be brought to London so it could be compared with the Virgin of the Rocks.’ It was Penny who told him [Simon]: ‘You need a consensus…’

“Since Robert Simon went public with the discovery, he has received many emails from Leonardo fanatics. ‘There’s the serious obsession and there’s the lunatic one – people for whom Leonardo is a source of fantasy. The paintings are not knowable,’ he muses. ‘Every one of them presents a problem and a challenge.’ Even at this stage? ‘Art historians are a prickly, competitive lot. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone stuck their hand up and said “I don’t believe it”’. Could the experts be wrong? ‘They could be wrong about anything. But as much as I believe anything in this world, I believe this is by Leonardo.’”

Above, and top left, the Salvator Mundi as exhibited in 2011 at the National Gallery’s big Leonardo exhibition.

Kathy Brewis continued:

“…Frank Zöllner of Leipzig University [- and author of the Leonardo catalogue raisonné] is a rare dissenter: he thinks the proportions of the nose (‘too long’ for such a perfectionist as Leonardo) make it more likely to have been painted by a talented follower. The rest are convinced, if a little jealous that they didn’t unearth it themselves. ‘People in the art world get sniffy about dealers,’ says Bendor Grosvenor, director of the London fine-art dealership Philip Mould. ‘But if it wasn’t for the trade, discoveries like this wouldn’t be made. Specialist dealers are the ones who are prepared to buy a dirty picture, roll their sleeves up and get stuck in to seeing what it is.’

“Is it wise for the National Gallery to put it on show so soon after its authentication? ‘They are taking a risk,’ says Grosvenor, ‘and I can’t applaud them enough for it. Connoisseurship is a nebulous discipline. There can never be absolute 100% proof. You have to accept there’s an element of doubt and go with it.’”

Note – On 5 March 2018 Grosvenor declared himself an ex-dealer on his blog Art History News: “Now, portraiture can be a hard sell – I know this from having spent over a decade actually selling portraits, in my former life as a dealer.” This did not come as an absolute bolt out of the blue: although he remains a director of the Scottish auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull Limited, last year Grosvenor briefly closed down his website following certain professional criticisms, commenting as he did so: “at the same time AHN also makes me a significant number of, well, ‘enemies’ is not too strong a term. Every walk of life has its Salieris, but in the art market there are an awful lot of them.”

Kathy Brewis continued with a discussion on the Salvator Mundi’s owners:

“Luke Syson, the show’s curator is one of the few people who know who owns the picture. ‘We couldn’t exhibit it otherwise. It’s not being wafted to us in a brown envelope.’”

Ben Hoyle reported the Salvator Mundi’s owners’ plans in the Times of 12 November 2011 (“It’s kind of scary – I wrapped it in a bin liner and jumped into a taxi with it”):

“‘Everyone involved recognises the importance of it as a work of art. Doing the right thing has been very important and will continue to be,’ Mr Simon says. If that means selling it for half the price they could attract, to ensure that it stays on public view, then they would prefer to do that.”

In the event the picture was sold privately by Sotheby’s in 2013 to a Swiss businessman, Yves Bouvier, who is known as the “Freeport King” (and who, among many commercial interests, owns an art conservation and authentication service), for appreciably less than the sums of $150-200m being talked about in 2011 (when the owners reportedly had turned down a $100m offer). The original consortium and Robert Simon received $80m for the Salvator Mundi from Bouvier who resold it for $127.5m to the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev.

To this day we do not know who owned the Salvator Mundi before 2005 or between 2005 and 2013. From whomever and by whomever it was bought in 2005, the painting’s reception as an attributed Leonardo in 2011 was very far from uniformly rapturous. In addition to the dissenting scholars we cited on 14 November 2017 (see THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF THE NEW YORK SALVATOR MUNDI), a number of newspaper art critics were un-persuaded.

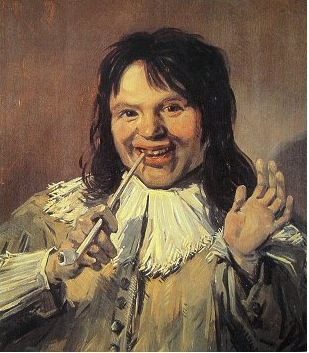

In the 13 November 2011 Sunday Telegraph (“The genius of Leonardo”), Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote:

“…The picture is certainly Leonardesque. But is it by Leonardo? That is the considerably-more-than-million-dollar question for the consortium of art dealers who acquired the work a few years ago for an undisclosed sum. If the attribution holds up they can expect to reap £125m as a reward for their good judgement.

“Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan is a breathtaking and truly remarkable exhibition which brings together around half of the surviving 15 or so surviving paintings by the famously dilatory artist of the Italian Renaissance…Two works in particular appear destined to come under scholarly fire.

“Although it gets the thumbs up from the National Gallery’s curator, [Luke] Syson, there will certainly be those who question the new Christ. The picture undeniably displays a number of the painter’s characteristic devices and mannerisms, but there are other aspects of it that seem foreign to Leonardo himself.

“He was prized by his contemporaries as one of the most innovative and forceful painters of emotion, yet the face of this Christ seems peculiarly inert. Taken individually, its elements are convincing enough, but viewed as a whole its expression seems to lack a certain subtle Leonardo magic: the spark of inner life and feeling…”

Even after the picture had been re-done-over by the restorer, Diane Modestini, ahead of the 15 November 2017 sale, the Sunday Times’ art critic, Waldemar Januszczak, responded with less tact than Graham-Dixon (“The Miracle of da Vinci: Turning a £45 Oddity into a £341m Old Master”, 19 November 2017):

“…To call the Salvator Mundi untypical is massively to understate the case. It resembles nothing else Leonardo painted

“The claim by Loic Gouzer, chairman of contemporary art at Christie’s in New York, that the record-breaking Jesus bears ‘a patent compositional likeness’ to the Mona Lisa had me laughing out loud. Yes, it shows the upper half of a figure in a frame. But that is the only compositional likeness the Salvator Mundi shares with the Mona Lisa…

“The next time I saw the painting was in 2011 when the big Leonardo exhibition was opened in London. Full of magnificent loans – the Lady With an Ermine, from Poland; the Virgin of the Rocks from the Louvre – it really was a once-in-a-lifetime event. And there on the wall was the recently rediscovered Salvator Mundi looking just as strange and sci-fi as I remembered it.

“At the time it was owned by a consortium of art dealers who had bought it in an American estate sale for $10,000 as a work by a follower of Leonardo. The dealers had it comprehensively cleaned and repainted. The National Gallery, eager to give its show a boost, announced it as the first new Leonardo discovered in 100 years. Wow…

“Soon after its London unveiling it was sold on to the Russian Billionaire, Dmitry Rybolovlev, for a reputed £98m. It was Rybolovlev who sold it again in New York last week.

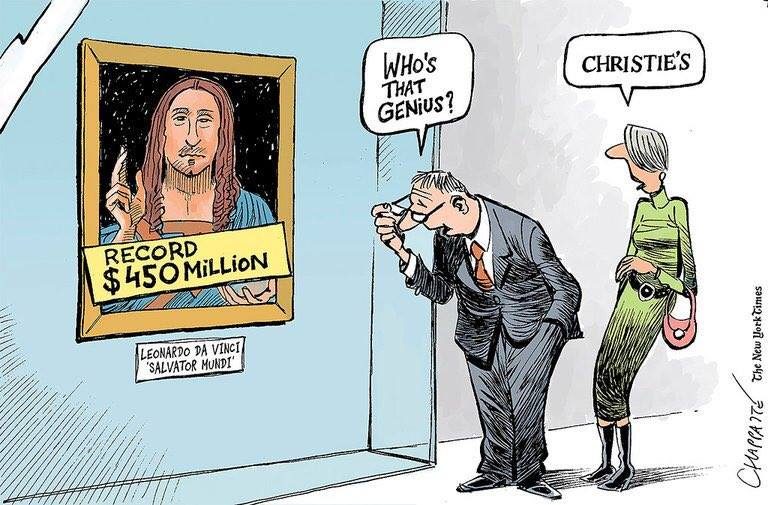

“How did Leonardo’s sci-fi Christ, who looks as if he belongs on the cover on one of L Ron Hubbard’s scientology textbooks, end up costing all those shekels? It was mostly due to the wicked brilliance of Christie’s.

“Not only did the auction house tour the picture noisily to Hong Kong, and London before the New York sale, drumming up interest among the newly rich, but its hype department was also in full swing on this one. Finding a new Leonardo, boomed Gouzer, ‘is rarer than finding a new planet’. It’s ‘the greatest discovery of the century’ repeated the Christie’s chorus.

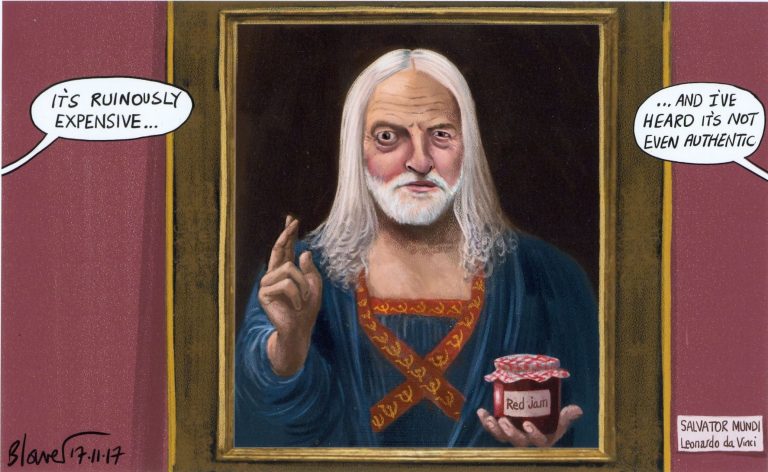

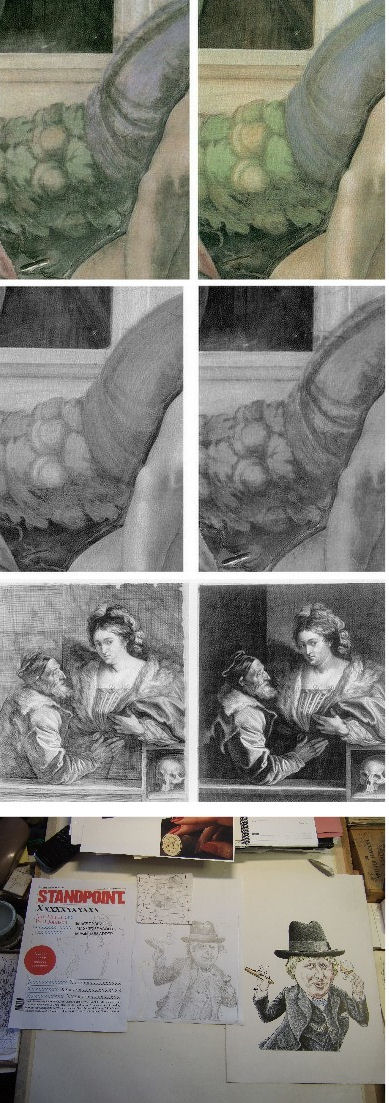

Above, Patrick Chappatte’s take on the Salvator Mundi sale/attribution for the New York Times. Below, Patrick Blower’s incorporation of the Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, for the Daily Telegraph:

Waldemar Januszczak continued:

“In recent years modern art has been where the money goes. A new generation of mega-rich collectors who know a lot about luxury brands but not much about art, have piled into the market and sent prices soaring.

“Earlier this year a quickly splattered Jean-Michel Basquiat of a face shaped like a skull sold in New York for an astonishing £85m. By putting the Leonardo in such a context, Christie’s circumnavigated the knowledgeable world of the Old Master collector and headed straight for the dumb f**** with the money.

“There are various ways to understand events in New York on Wednesday night [of 15 November 2017].

“You can see them as evidence of Leonardo’s treasured and mythic status in art. You can see them as testimony to the power of attribution. Or you can see them as proof that we live in a mad world that has lost sense of true value and in which obscenely rich people waste obscene amounts of money on the obscene acquisition of trophy art. Going, going, gone.”

SUPPORT AND DISSENT

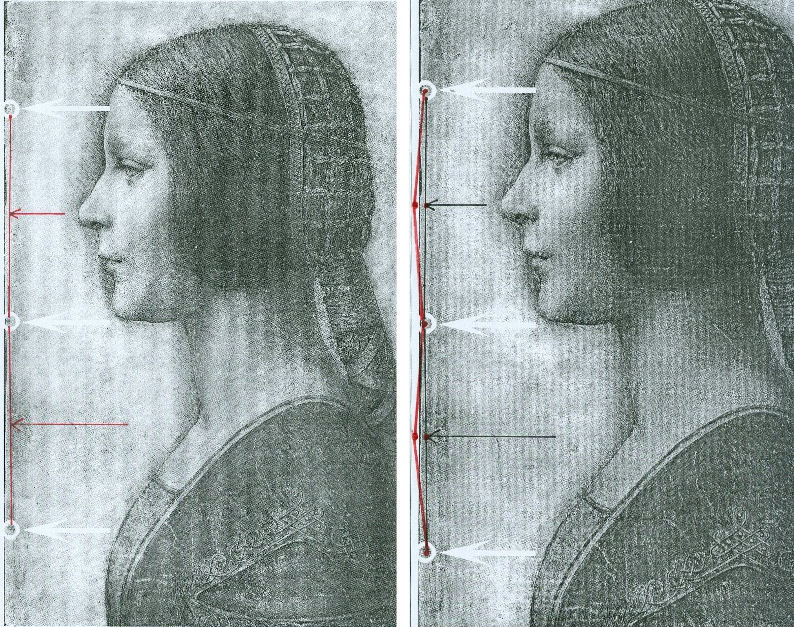

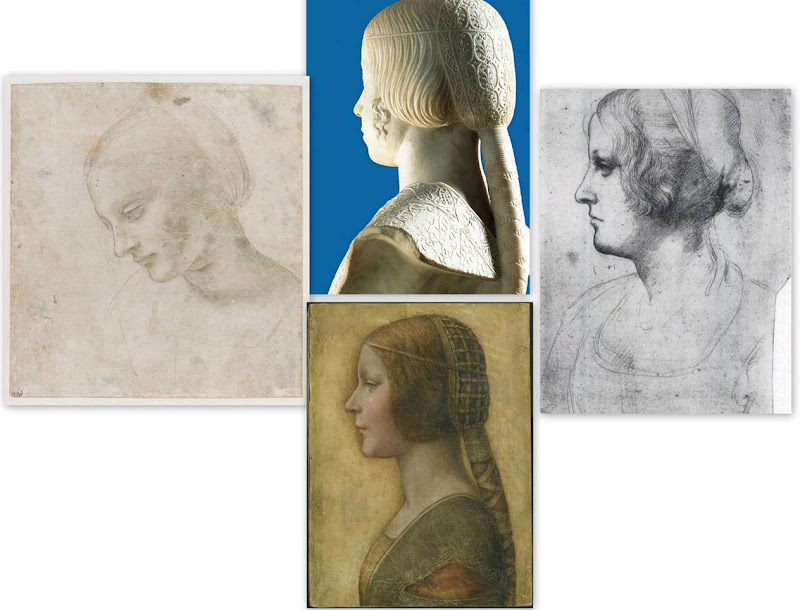

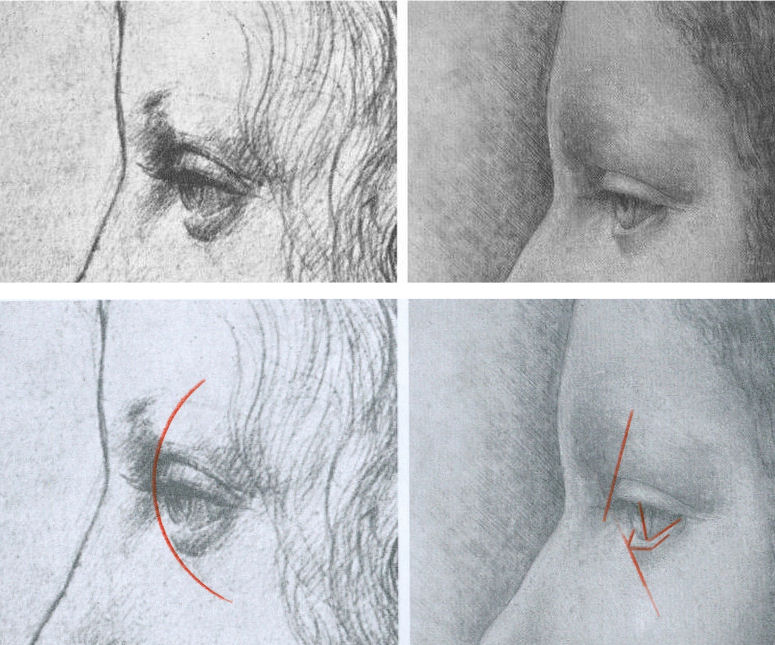

It so happens that the scholar who first attributed the Salvator Mundi to Leonardo, Professor Mina Gregori, was also the first scholar to attribute the proposed Leonardo drawing that was dubbed “La Bella Principessa” by Professor Martin Kemp. However, “La Bella Principessa” was not included in the National Gallery’s Leonardo exhibition and, seven years later, it remains unsold. Although we know precisely why the dissenting scholars rejected the Salvator Mundi attribution (- they published their views in the scholarly press), we have virtually no information of who said what and in what order among the consensus of scholars listed by Christie’s (see Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation).

SECRET DEALS – AND THE ARTS CLUB

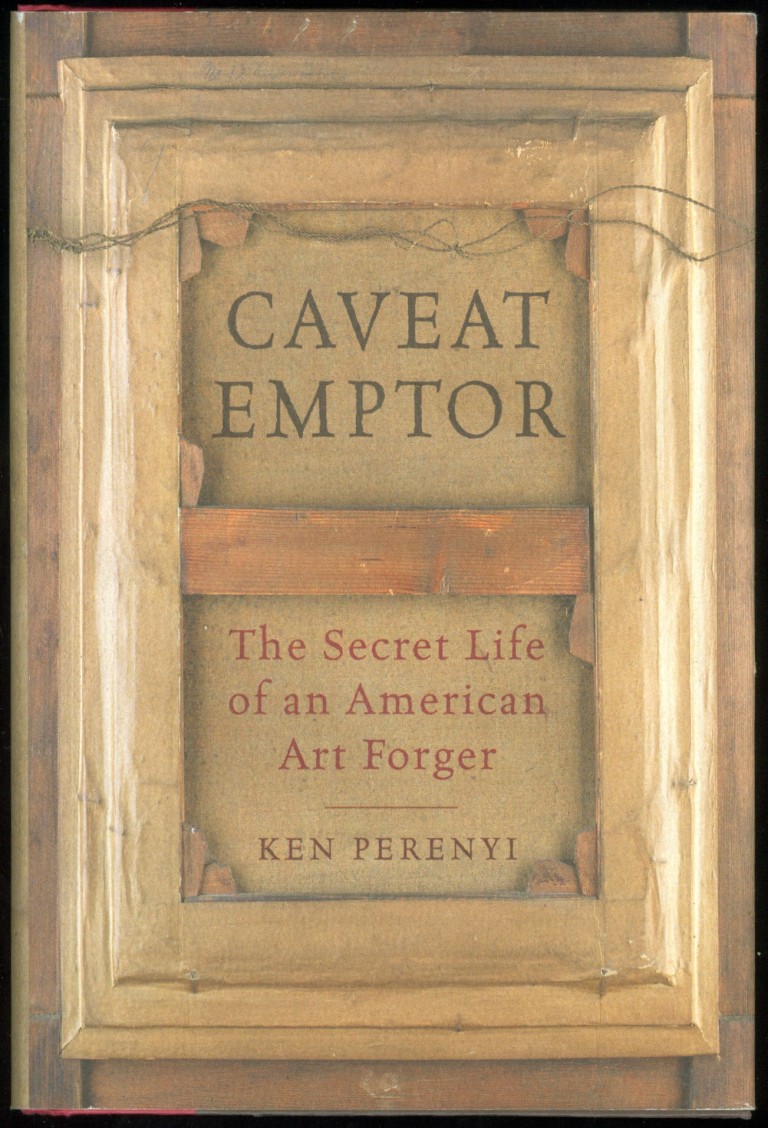

Since we began warning on this site in 2014 of the threat to market confidence posed by the art world’s toxic attributions and specifically called for increased transparency through a statutory requirement that vendors should disclose all that is known and recorded about the provenance and the restoration treatments of works of art (“As things stand, it can be safer to buy a second-hand car than an old master painting” – “Art crime”, ArtWatch UK letter, the Times, 13 August 2014), secret deals have come under increasingly intense investigation. In her 2017 book Dark Side of the Art Boom, Georgina Adam wrote:

“At its base, the Bouvier/Rybolovlev dispute was about the nature of their business conducted within a market that has always thrived on secret backroom deals. By keeping vendors and buyers apart – they may never know who the other is – and insisting on discretion, agents, dealers, advisors can use this anonymity to their advantage. Various reasons can be put forward, from the need for security to the desire to avoid family quarrels or the taxman, to the risk of someone else bagging the work for sale. In the Bouvier/Rybolovlev case, one of Bouvier’s emails about a Magritte, said: ‘I must carry out this [negotiation] with the greatest discretion to avoid drawing attention to the painting and its owner; the risk is that we could lose it at auction.”

In this weekend’s Financial Times (10/11 March 2018 – “Laundering Picasso: British dealer among accused in $50m case”), Melanie Gerlis cites the emergence of another highly embarrassing series of documents:

“Potential shenanigans involving art are in the spotlight once again. London art dealer Matthew Green is among defendants in the case against Beaufort Securities, three other corporations and five other individuals, accused by the US Department of Justice of a multiyear $50m-plus securities fraud and scheme to launder money, partly through the sale of a £6.7m painting by Picasso.

“The indictment alleges that Green, described as the owner of Mayfair Fine Art Limited, met last month with an investment manager from Beaufort Securities (now declared insolvent), as well as a property developer and an undercover federal agent masquerading as a client of the brokerage firm. At this meeting held around February 5, the court papers say that the agent-client was told he could ‘purchase a painting from Green using the proceeds of the stock manipulation deals and later sell the painting to “clean the money”’…The papers describe the art business as ‘the only market that is unregulated’”.

“The papers also say that Green – who had allegedly asked for a 5 per cent profit on the transaction, ‘so that he would not be asked why he was in the money laundering business’”. [Green] sent a message via What’sApp to the Beaufort Securities manager that read: ‘[O]bviously because of the nature of this transaction we need to preserve a certain amount of anonymity which [the undercover agent] and I discussed and clarified at the Arts Club!’”

UNDERCHARGING FOR CURRENT MARKET PRACTICES

The Art Market Monitor blogger, Marion Manneker, made this observation in his (5 March) comments on the trial:

“Green doesn’t seem to know that the price for laundering money is much higher than 5% which definitely isn’t worth the risk if it gets you indicted after being in business all of three months. Worse still, Green and his partners don’t seem to be the swiftest criminals. They boasted that the art market is unregulated but then created a scheme that seems to have had little to do with the art market itself.

“The art sale is only one of several money-laundering venues that the person was offered. Offshore banks and real estate deals figure prominently in the indictment. What’s more, Green’s scheme could have been conducted in just about any commercial transaction. And, since the payment for the Picasso was due March 6, 2018, we’ll never know if Green was actually capable of pulling off the sale at the price he claims or would have survived any kind of audit.”

OLD HABITS DIE HARD?

Manneker’s comments on the cut-price scale of Matthew Green’s alleged laundering service charges recalls certain comments of Kenneth Clark who recognized that his appointment as director of the National Gallery at a very tender age owed much to the fact, as he wrote in his 1977 memoir Another Part of the Wood, that:

“[T]he ideal candidate for the post was disqualified. This was a Finnish art-historian named Tancred Borenius. He was a good scholar, a pleasant companion and a passionate upholder of the concept of the monarchy. He would have made an ideal courtier. Unfortunately, he was known to have followed the continental practice, described above, of taking payments for certificates of authenticity; and what was worse, quite small payments (known as ‘smackers under the table’); if he had taken large payments like a few scholars on the continent, no one would have objected.”

Michael Daley, 11 March 2018

UPDATE, 12 March 2018. On 11 March, a Sunday Telegraph supplement (“Arts, Antiques and Collectibles”) carried a “Promotional feature” – “Managing Risk When Buying and Selling Art” – for the law firm Constantine / Cannon. In offering the firm’s services, the article began:

“TRADING IN ART has traditionally been done on a handshake, but this is changing. You would not buy or sell a house without relying on a lawyer to prepare the contract, would you? The same goes with art, and now buyers and sellers are increasingly turning to lawyers to help them manage the risks associated with expensive works. The art market used to function like a club of like-minded people, but that’s no longer the case. The market now is truly global, and it has become less transparent in the process…”

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: No. 1 – Civilisations and Burrell Loans

It’s official: the BBC remake of Kenneth Clark’s highly acclaimed television series Civilisation is an intellectually incoherent artistically obtuse “right-on” mish-mash. It is official: Glasgow is repeatedly dicing with Burrell’s bequeathed art for financial peanuts and supposed profile enhancement.

NICE PICTURES, POOR WORDS

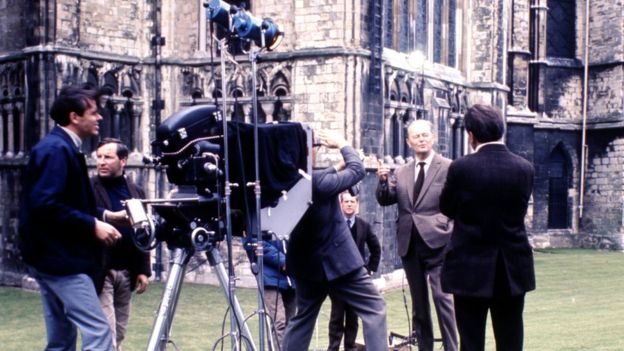

Above, top, Kenneth Clark shooting on the still-acclaimed 1969 series Civilisation; above, Simon Schama fronting the scathingly-received 2018 multi-voiced Civilisations outside Itimad-ud-Daulah’s Tomb in Agra, Uttar Pradesh.

“…By adding a single pluralising letter to the classic BBC art history series Civilisation (1969), the programme makers of Civilisations opened up the tantalising possibility of producing a new TV series that didn’t simply match its singular predecessor, but was much better.

“You can see the sense in the idea. Instead of an old-fashioned, patriarchal, white, western, male view of human cultures and creativity, why not make a show that acknowledges there are different civilisations and different views, which can be put across by different presenters? (In this case, three TV-ready, scarf-wearing academics: Mary Beard, David Olusoga and Simon Schama.) …from the programmes I have seen, Civilisations is more confused and confusing than a drunk driver negotiating Spaghetti Junction in the rush hour.

Above left, Aphrodite of Menophantos, Praxiteles, (4th Century BCE), Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome; above, right, Hand Stencils found in the Cave of El Castillo in Spain.

“The series starts with Schama – who has ‘always felt at home in the past’ – showing us library footage of an Islamic State wrecking crew in Mosul destroying ancient art and artefacts.

“He tells us the grisly story of how they brutally murdered the 82-year-old Syrian scholar Khaled al-Asaad for withholding information from them as to the whereabouts of the antiquities under his curatorial care in Palmyra.

“‘The record of human history brims over with the rage to destroy,’ the historian tells us with his passion dial turned up all the way to 11 (it rarely dips below 10).

“There is no mention made of similarly barbaric acts that have taken place over millennia – on occasion perpetrated by a civilisation much closer to home – or an explanation as to the cultural rationale behind the actions of those wielding the sledgehammers in this instance.

“…Music swells, titles roll, and we’re off – back to the beginning and the caves of South Africa, where we are shown a 77,000-year-old block of red ochre with the ‘oldest deliberately decorative [human] marks ever discovered’.

“This is ‘the beginning of culture’, Schama tells us, but he doesn’t dwell. Moments later we’re travelling through time and space like Doctor Who in a sci-fi remake of Treasure Hunt, touching down around 40,000 years later in northern Spain to visit El Castillo Cave.

“Here, both the programme and the presenter start to settle down and enjoy what they’ve brought us to see: cave paintings and hand stencils.

“Apparently similar images have been found ‘as far apart as Indonesia and Patagonia’, which is interesting. But then frustrating as no explanation is forthcoming to enlighten us as to why that might be.

“We are told: ‘These hand stencils do what nearly all art that would follow would aspire to. Firstly, they want to be seen by others. And then they want to endure beyond the life of the maker.’

“Really? Was that actually the motivation behind our stencil-making ancestor? Was he or she honestly most concerned with artistic ego and posterity? Were the painted hands even intended as art? Could they not have been a functional way-finding device or a ritualistic mark or part of a magical spell?

“…These are patchwork programmes with rambling narratives that promise much but deliver little in way of fresh insight or surprising connections.

Above, Mary Beard fronting Civilisations at the Colossi of Memnon in Luxor, Egypt.

“Mary Beard’s episode, How Do We Look, is particularly disappointing because the premise is so enticing, as is the prospect of one of our foremost thinkers on matters cultural giving us a new perspective.

Sadly, other than a couple of memorable TV moments when Beard encounters an ancient statue for the first time, we are offered little to excite our imaginations.

We don’t get the alluded-to update on Clark’s Eurocentric views or on John Berger’s Walter Benjamin-inspired Ways of Seeing series.

There is no substantial new polemic with which to wrestle. Instead we are served a tepid dish of the blindingly obvious (art isn’t just about the created object but also about how we perceive it), and the downright silly (an ancient story about a young man who supposedly ejaculated on a nude sculpture of Aphrodite thousands of years ago, which Beard describes with great theatricality as rape – ‘don’t forget Aphrodite [the stone statue] never consented’).

Above, David Olusoga fronting Civilisations with Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“David Olusoga is altogether more measured and less mannered than his fellow presenters. His two films – one exploring the meeting of cultures between the 15th and 18th Centuries, the other looking at the enlightenment and industrialisation – benefit from his inquisitive nature and relaxed style.

“If the scripts in the series are far from being literary masterpieces, the camerawork is of the highest quality throughout – although there are too many stylised shots of out-of-focus presenters with their backs to us.

“But when trained on art and artefacts, the new technology and techniques at the 21st Century TV director’s disposal provide us with plenty of delicious visual treats (the images from Simon Schama’s trip to Petra are stunning).

“Ultimately though, Civilisations feels like a series made by committee: a terrific-sounding idea on paper that I suspect was a lot harder to realise in practice.

“The result is a well-intentioned, well-funded series that has top TV talent in all departments but which ended up being less than the sum of its parts. A case of too many cooks, maybe?”

– Will Gompertz, the BBC’s art editor (Will Gompertz review: Civilisations on BBC Two 3 March 2018).

NICE PICTURES, NEEDLESS MULTIPLE RISKS

Above, Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal (1874) CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

“Fascinating details about a tour of the Burrell Collection’s late 19th-century French paintings have been revealed. Financial data on touring exhibitions is normally highly secret, but the Burrell’s data has been recorded in a report for a Glasgow City Council meeting on Thursday (8 March). This meeting is expected to approve the exhibition loans.

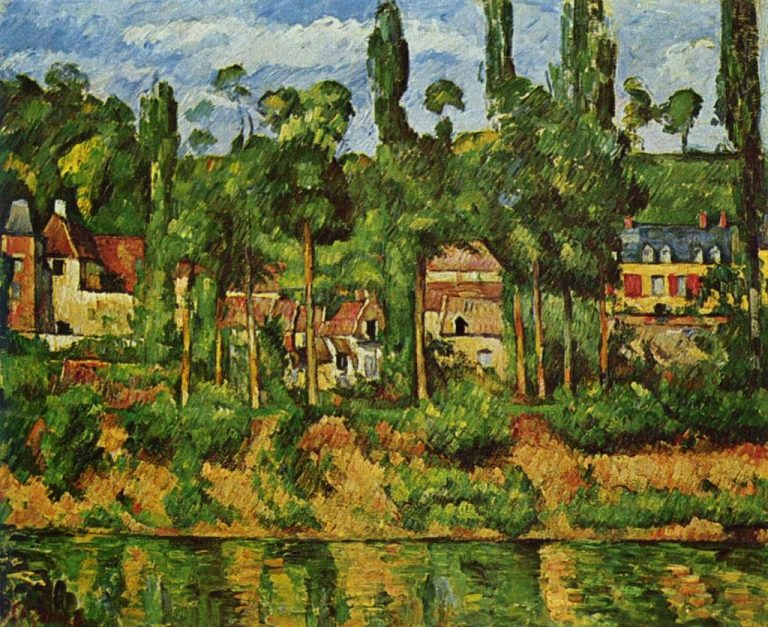

“A group of 58 works is being lent to the Musée Cantini in Marseille, which reopens on 18 May after refurbishment. The council report values the 47 paintings and 11 works on paper at £180.7m. The pictures include Degas’s The Rehearsal (around 1874) and Cézanne’s The Château of Médan (around 1880).

“Although the Japanese tour will be larger, with 55 paintings and 25 works on paper (including seven non-Burrell works from Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum), the value of the loans will be lower: £141.8m.

“What is even more interesting [is] the complex financial details of the deal. No fee is being paid by the Musée Cantini, but a sponsor is assisting the Burrell. It will contribute €100,000 towards the exhibition costs and €50,000 towards the Burrell’s refurbishment costs. The Art Newspaper understands that the sponsor is likely to be the London-based financial advisors Rothschild & Co and its new Marseille banking partner, Rothschild Martin Maurel.

“The Japanese tour, which will go to five venues from this October to January 2020, is being financed on a different basis. Each venue is paying a hire fee of £30,000, plus £1 per visitor after the first 100,000. If, for the sake of argument, each venue attracts 150,000 visitors, then the full total from Japan would be £400,000 (plus €50,000 for the French venue).

“When the tour idea was first considered, five years ago, the Burrell hoped to raise many millions from a touring exhibition, but this target has proved much too ambitious. James Robinson, the director of the Burrell Renaissance project, says that ‘profile raising for the Burrell and for Glasgow is just as important as the funding’.

“The Burrell Collection… building is now in need of a fundamental refurbishment. The cost of the refurbishment project is estimated at £66m, which means that the touring shows may bring in around 1% of the total. Glasgow City Council is to provide up to half the £66m and the Heritage Lottery Fund has awarded £15m, with contributions from other donors.

“Under the terms of Burrell, who died in 1958, his works could not be lent abroad because he was concerned about transport risks. In 2014 the Burrell trustees obtained special approval from the Scottish Parliament to enable them to lend abroad. The collection’s works by Degas are currently on loan to London’s National Gallery, until 7 May.

“The Burrell Collection closed for refurbishment in October 2016 and is due to reopen in late 2020.”

– Martin Bailey, “Revealed: the profits of staging a touring exhibition”, The Art Newspaper, 5 March 2018

Above, Cézanne, Château de Médan (1880) CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Michael Daley, 5 March 2018

Coda: For our earlier words on the overturning of the terms of Burrell’s bequest, see:

“Protecting the Burrell Collection ~ A Blast against Risk-Deniers”;

Nouveau riche? Welcome to the Club!

Our previous news/notice – “A day in the life of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s pricey new Leonardo Salvator Mundi” – was pegged on Georgina Adam’s Financial Times interview with Christie’s CEO, Guillame Cerutti.

In today’s Art Market Monitor blog, Marion Maneker defends Georgina Adam’s book, The Dark side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, against a review in The New Republic:

“Unfortunately, [Rachel] Wetzler’s idea of a critique is to somehow fault Adam for not belabouring the obvious context of her book:

‘But while Adams paints a detailed and convincingly dire picture of the art world’s excesses, she never fully probes its implications. Perhaps ironically, its central weakness is her narrow focus on the activities of the art market itself: Her book largely brackets an exploration of the art market from the broader context of rising income inequality, economic exploitation, and staggering concentrations of wealth in the hands of the very few, all of which have enabled activity at the its upper reaches to continue unabated despite global downturns in other financial sectors. According to the sociologist Olav Velthuis, the art market ultimately benefits from an unequal distribution of wealth, as newly minted billionaires turn to blockbuster art purchases as a means of announcing their arrival…’”

Maneker dismisses the general charge as “both obvious and silly” but sows confusion with a claim that the rich “have many ways to announce their arrival” other than by social climbing. While that, too, may be self-evident it distracts from the force and precision of Adam’s analysis of certain shortcomings within the art market’s own institutions. When speaking of an apparent art world unwillingness to eliminate decades-long fraudulent practices – even after the most revelatory scandals – Georgina Adam (p. 191-2) pinpoints specific failures:

“What is surprising is the lack of impact the art market scandals have actually had, as lawyer Donn Zaretsky told me:

‘I haven’t seen much change after Knoedler [’s great Fakes Scandal]…I still see people doing deals on a handshake. The fact is the art market is a market but also a social world. If people are buying Tribeca real estate they will do the necessary research, bring in the lawyers, stitch up the contracts, and yet if they buy a picture for $3m they will hardly do anything.

‘It’s all part of this social world, meeting the artist, going to the parties. And buying art is an entrée to this world. You need to understand this in order to understand why these things happen, and why the art market will be so hard to regulate.’”

Marion Maneker’s Art Market Monitor blog of 22 February linked to a discussion between Glenn Fuhrmann and Lary Gagosian and noted that: “in this interview, one can see some indications of how deeply Gagosian’s success is tied to his ability to create among his clientele the sense of belonging to an exclusive club.”

There exist further three-way relationships between dealers, auction houses and collectors. Gagosian reportedly underwrote the recent $450m sale at Christie’s of the Salvator Mundi with a $100m guarantee to buy. This is said to have been in exchange for a $60m guarantee from the Salvator Mundi’s vendor to buy – in the very same auction of modern art – a Gagosian-owned Warhol of Leonardo’s Last Supper.

Michael Daley, 27 February 2018

A day in the life of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s pricey new Leonardo Salvator Mundi

On February 10th the Financial Times carried an interview – “The king of King Street” – with Guillame Cerutti, the French-born and École Nationale d’Administration-educated CEO of the (French-owned) British auction house, Christie’s, by Georgina Adam.

On the same day as the interview by Georgina Adam, author of Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses Of The Art Market In The 21st Century, the French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe, toured the Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum on Saadiyat island in the Emirati capital, to launch the French-Emirati “Year of Cultural Dialogue” in the company of Shiekh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, CEO of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (see Figs. 4 and 5).

Above, Fig. 1: Christie’s CEO Guillame Cerutti, as photographed by Anna Huix for the FT, 10 February 2018.

Georgina Adam asked Christie’s CEO if he had been surprised by the price of the Salvator Mundi sold at Christie’s, New York, on 17 November 2017 for $450 million (as an entirely autograph Leonardo da Vinci painting):

“He pauses. ‘Yes, because before the sale it was difficult to ask anyone to predict that level. But at the same time our major clients are looking for trophies. They want quality and rarity in any field. This painting had both aspects, it ticked all the boxes.’”

On 11 December 2017 money.cnn reported that Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism had confirmed that it had purchased what was the most expensive painting in the world for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the museum’s first outpost outside France, but it had declined to comment on the owner. The New York Times had reported (“Mystery Buyer of $450 Million ‘Salvator Mundi’ Was a Saudi Prince”) that the man behind the purchase was a little-known Saudi prince named Bader bin Abdullah bin Farhan al-Saud, an associate of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Saudi Arabia, through its embassy in Washington, subsequently said that the prince was acting as a middleman for the United Arab Emirates, a key ally in the region: “His Highness Prince Badr, as a friendly supporter of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, attended its opening ceremony on November 8th and was subsequently asked by the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism to act as an intermediary purchaser for the piece.”

When Adam asked about the Salvator Mundi painting’s condition Guillame Cerutti responded:

“There were questions on that, we didn’t hide anything. It is 500 years old and the condition reflected that – but we were transparent about this. It is a beautiful painting, and the day after the sale, the Louvre requested it for an exhibition in 2019.”

In Christie’s pre-sale essay “Salvator Mundi – The rediscovery of a masterpiece: Chronology, conservation, and authentication” the painting was said to have been discovered in 2005 “masquerading as a copy” in a “regional auction” in the United States. The curiously anthropomorphised notion of an inanimate artefact seeking to deceive, might no less appropriately be applied today to a damaged and covertly re-restored painting that still lacks a secure provenance. The essay’s account of the work’s “conservation” revealed that in 2007 “A comprehensive restoration of the Salvator Mundi is undertaken by Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Senior Research fellow and Conservator of the Kress Program in Paintings Conservation at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.” Modestini was said to have concluded that: “the important parts of the painting are remarkably well-preserved, and close to their original condition”.

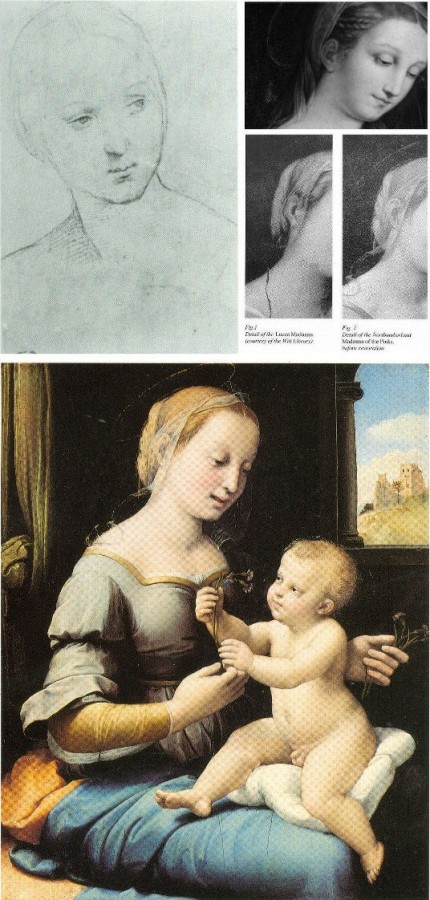

Above, Figs. 2 and 3: showing the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi when exhibited in 2011-12 as an entirely autograph Leonardo in the National Gallery’s Leonardo da Vinci ~ Painter at the Court of Milan exhibition, left; and then, right, as offered for sale by Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017.

In its pre-sale lot essay on the painting, Christie’s acknowledged an “initial phase of the conservation” that ran from 2005 to 2007, and that the entire conservation programme had been brought to completion in 2010 before the painting was included as “The newly discovered Leonardo masterpiece, dating from around 1500” in the National Gallery’s major Leonardo exhibition of 2011-12. The essay notes that the painting had been acquired from “an American estate”. At no point before the November 2017 sale, so far as we know, had Christie’s acknowledged the further extensive campaign of restoration that we have shown to have occurred between 2012, when the picture returned from London to New York, and the November 2017 sale where it fetched $450 million and caused some commentators to fear that an important and vital market might be “on the edge of becoming seriously troubling” – see: “The $450m New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part II: It Restores, It Sells, therefore It Is”.

Notwithstanding Mr Cerutti’s FT interview, we still do not know when – or to what purpose – restoration was resumed after the National Gallery Leonardo exhibition but, as we have reported, a Christie’s spokeswoman confirmed to the Daily Mail in December 2017 that Dianne Modestini, had worked on the painting “Prior to its presentation for sale at Christie’s”. (See “Auctioneers Christie’s admit Leonardo da Vinci painting which became world’s most expensive artwork when it sold for £340m has been retouched in the last five years”.)

In today’s Guardian (Financial, p. 32, “A switch is flipped and renaissance is suddenly fragile”), Larry Elliot attributes the Salvator Mundi’s gasp-inducing record high price to an “obvious” explanation: “Rock-bottom interest rates and Quantitative Easing have driven up the prices of assets sought by the already well-off. It has been the classic case of too much money chasing too few goods.” Georgina Adam noted that Guillaume Cerutti “quickly points out that in 2017 Christie’s sold seven of the top 10 lots at auction – including the Leonardo”. Cerutti might arguably be seen as one who has fuelled as well as benefitted from the current boom by having shut down Christie’s lower-value operation in South Kensington and cut-back that in Amsterdam so as to direct resources to Asia and Los Angeles.

Above, Figs. 4 and 5: Top, French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe (right), tours the Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum on February 10, 2018, on Saadiyat island in the Emirati capital, to launch the French-Emirati “Year of Cultural Dialogue”. Above, the French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe (centre) poses with Shiekh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (right), CEO of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, during inauguration of BNP paribas Abu Dhabi Global market Branch on February 10, 2018, as photographed by Karim Sahib for AFP and featured in Art Daily’s The Best Photos of the Day on February 11, 2018.

Michael Daley, 12 February 2018

Degas and the Problem of Finish

Alexander Adams

Daphne Barbour & Suzanne Quillen Lomax (eds.), Facture: Conservation, Science, Art History. Volume 3: Degas, National Gallery of Art, distr. Yale University Press, 2017, 196pp, fully illus., pb, £50, ISBN 978 0 300 23011 6

Jane Munro, Degas: A Passion for Perfection, Yale University Press, 2017, 272pp, 250 col./mono illus., hb, £40, ISBN 978 0 300 22823 6

The new title published by the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., Facture: Conservation, Science, Art History. Volume 3: Degas, examines its large collection of art by Edgar Degas as a starting point for discussions about issues of interpretation, finish and conservation regarding Degas’s oeuvre. The problem of finish is one that applies more to Degas than any other French artist of the Nineteenth century. Contemporaries criticised (and, more rarely, praised) Degas’s art for its open and unfinished appearance. This was not a case of stuffy regressives wanting a glossy varnished surface to paintings but often genuinely perplexed viewers feeling the artist had not fully resolved matters. What Degas considered finished and unfinished was also unclear to the artist himself. He would exhibit pieces that seem to have been arrested at an early stage; at other times he would retrieve and rework paintings he had already signed, exhibited and sold. Multiple signatures on a work indicate radical revision of a piece as the artist reconsidered what he considered to be finished. His standards evolved over his long career but even experts have trouble deciding what is finished and what is unfinished, especially as the bulk of his art remained in the studio and much of it was unsigned.

Classicism and Radicalism

Visible pentimenti could be intrusive and Degas’s habit of sanding down surfaces of oil paintings but then not fully repainting them left viewers doubtful about whether the painting had actually been completed. (Specifically, the long working periods, extensive revisions and awkward and incomplete appearances of the canvases The Fallen Jockey and Edmondo and Thérèse Morbilli make these “problem pictures”.) Signatures do not resolve such questions as Degas did not sign all works, especially drawings, which could be categorised as either working material or finished art depending on who was appraising it (or trying to sell it).

Degas was the Impressionist who received the most thorough grounding in academic fine-art tradition and also the one who experimented most technically and aesthetically. He could be reckless and sometimes destroyed art by overworking it. He could also be impatient and imprudent. Hoenigswald and Jones (in Facture) mention the case of Portrait of Mlle Fiocre in the ballet “La Source” (c. 1867-8) as an instance when Degas prematurely varnished an oil painting for salon display. The varnish interacted with the wet paint and he had to call on the services of a conservator to remove the varnish, which inevitably damaged the picture surface. He rarely varnished work himself but did not rule it out and recommended that Pau museum varnish his Cotton Office in New Orleans (1873) when the museum acquired it. However, that instruction regarding an early highly-finished oil is not carte blanche for the varnishing of all his oils, especially later ones.

Degas could be both methodical and capricious. He would prepare carefully and spend long periods of reflection. There is Vollard’s famous anecdote of him “sunning” his pastels for extended periods to degrade fugitive pigments so that he could be confident of his colours not ageing too drastically once applied. At other times he could work hectically, impatiently fixing broken limbs of his statuettes with gimcrack bodges, later allowing his clay pieces to be reduced to crumbled dust. Rather than always fully conceiving his compositions beforehand, he would start a work and have to add strips of paper to expand the surface. The use of tracing paper – mainly to allow tracing and transferring of designs – as a support for finished drawings is problematic as the vegetable starch in the calque makes the support fragile and prone to discoloration; the oils in the paper oxidise and discolour. Degas would have tracing paper sheets glued to board supports to impart rigidity and prevent the paper curling or ripping. Exquisite sketches exposing areas of untouched paper have been changed irretrievably by the fading effect of sunlight on the dyes in the commercially prepared colour paper. (For whatever reason, many similar works by a colleague of Degas’s student days, Moreau, have fared rather better.)

The perplexing confluence of technical brilliance, peculiar material combinations, unconventional working methods and appalling insouciance makes Degas’s art a tricky proposition for conservators. Respecting the artist’s wishes is not always possible when the artist can be so contradictory in his approaches apparent even in one work of art.

Degas’s technique for many works was mixed. Monotypes in black ink would often be worked over so extensively in pastel, gouache and body colour that the original print disappeared under the colourful top layer. The artist’s penchant for privacy meant that his techniques and attitudes are a mystery which scientific analysis is only now uncovering. One of the great mysteries is his formula for pastel fixative. Pastels (particularly heavily worked ones) require fixing with a clear sealant for transport or for reworking. This fixative impairs colour intensity and tonal contrast and artists have struggled to find a solution that is effective yet as unobtrusive as possible. Views on the subject have ranged from the idea Degas creating his own secret formula (which has never been uncovered) to the view that Degas used a standard mixture common to the period. Microscopic analysis of a pastel in the NGA collection reveals a dried bubble of fixative (less than half a millimetre across) which contains protein, implying a solution including casein or rabbit/fish-skin glue applied with an atomiser.

Forensic analysis suggests that Degas worked pastels wet and dry, using hard and soft tools, brushes, his fingers, adding, subtracting and burnishing, with frequent layers of fixative. Despite the liberal use of fixative, the absence of tooth on the smooth tracing-paper support makes those drawings especially fragile, something that has to be born in mind in this age of frequent and distant travel for temporary exhibition.

Dance Examination

Above, Fig. 1: Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Dance Examination (Examen de Danse), 1880, pastel on paper, 622 x 465 mm, Denver Art Museum, anonymous gift. Photography courtesy Denver Art Museum

The new exhibition at Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (closes 14 January; tours to Denver Art Museum 18 February-20 May 2018) allows viewers to decide what they think of the condition of Dance Examination (1880) [See “Fakes, Falsifications and Failures of Connoisseurship” – Ed.]. The catalogue Degas: A Passion for Perfection includes high-quality illustrations of this pastel and others. This pastel has previously been discussed by Artwatch. Compared to the 1918 photograph there has been noticeable change. It is difficult to ascertain what is due to fading, restorer intervention and variation in photography. Some changes seem clearly evidence of fading. The blue of the bending dancer’s sash is increasingly showing through the white overdrawing of the standing dancer’s dress. The top layer of white is less opaque than it was. The red cockade is less prominent than it was, though why that might be is unclear. Some areas do seem to have been deliberately altered: the wall seems to have been cleaned; the shadow between the leftmost leg of the bending dancer has been streamlined by slimming the wedge of shadow adjacent to the dancer’s other foot (to our right) and making the shadow more uniform; the bench seems to have been smoothed, with some near horizontal lines in the original (in the centre and right) having been blended or over drawn. That said, the new photograph has more contrast than the 2002 photograph, which seems way too pale and lacking contrast, demonstrating that the 2002 reproduction was a poor one. The new photograph suggests that there has not been a determined campaign to retouch the whole drawing but instead very particular instances of alteration (probably early, between photographs one (1918) and two (1949)) combined with fading of particular pigments. The pastel entered the Denver Art Museum collection in 1941.

The Bronzes

Above, Fig. 2: Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Arabesque over the Right Leg, Left Arm in Front, First Study, c.1882–95, coloured wax over a commercially prefabricated metal wire armature, attached to a wooden base, 23.5 x 13.7 x 27.5 cm, © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

What makes the NGA’s Degas collection unique is the group of the artist’s original statuettes. These were retrieved from multiple floors of Degas’s last house in the months after his death. The heirs agreed to the figures being catalogued, graded and (if possible) repaired with a view to casting them. Many remains were found to be unsalvageable but 74 items were repaired and cast in bronze in various editions. Exact casting details were not recorded methodically. The majority of original items were in pastiline (like plasticine) over a commercially manufactured articulated wire armature adapted by the artist, which was later coated with pigmented beeswax, which allowed detailed finish, though Degas rarely applied fine details. The exception is Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1878-81), his famous life-size statue in a real bodice and tutu, which was the only sculpture he publicly exhibited. (The original is now in the NGA collection.) X-rays reveal Degas used clay, corks, paintbrush handles and rags to add bulk to the statuettes and when limbs became detached he would use pins of nails to reattach them. The figures (almost all of them either female figures or horses) were attached to wooden base boards, sometimes with props to support them.

Degas’s attitudes to his statuettes were mixed. He worked hard on them and sometimes showed them to visitors. He kept some in vitrines. Yet he neglected some finished pieces and allowed them to become badly damaged. He never cast any pieces in bronze though he did make notes about foundries; it was apparently his wish that none of the models be cast in bronze.

The restorer(s) of the statuettes who prepared the models for casting approached the task with a mixture of attentive respect and no-nonsense pragmatism. The decision to disregard Degas’s aversion to casting in bronze was a matter for the heirs. The restorer(s) had the practical task of repairing damage, most often in limb breakages. Sometimes the limbs had been fractured, sometimes completely detached. Breaks were repaired and blended with the original facture. Often props on the originals were replaced and completely removed from the casts. (There exists an incomplete photographic record that documents the original statuettes before preparation for casting, showing breakages.) The restorer(s) attempted to preserve as much as possible of the originals but felt no compunction about making alterations to suit the expectations of collectors of the day, including blending their repairs with the original facture. Obviously, the casting process made almost invisible the visible repairs in the original figurines.

In the 1950s the original wax statuettes resurfaced in the foundry. They were purchased by Paul Mellon and most were donated to the NGA. Three original dancer figurines ended up in the Fitzwilliam Museum collection and are included in the current exhibition; the catalogue reproduces x-rays of them, showing the armature and packing inside.

In Facture expert essayists from NGA staff address the chaotic editioning of the bronzes, authorised, unauthorised and possibly pirated. Two foundries cast bronzes from 1920 until the mid-1930s, often as and when demand necessitated new sets. Foundry records are incomplete or suppressed. Two essays in this book study of the construction of the sculptures and various stamps; measurement in millimetres of the exact dimensions of casts and metallurgical analysis suggest the chronology and status of hundreds of the over 1,200 genuine casts. Further sets, which are considered by some to be fakes, continue to circulate. Comparative photographs show differences between casts. These photographs show the variable results of the moulding and casting processes and others which might the work of the finishers.

These volumes (especially the NGA’s Facture) will be essential references for collectors, dealers and scholars in Degas.

Alexander Adams, 3 November 2017

[See also, Alexander Adams: Degas: Themes and Finish. For details of the 2017 James Beck Memorial Lecture (the speaker: Robin Simon – “Never trust the teller, trust the tale”) see A memorial lecture, two journals and an assault on scholarship.]

Leonardo, Salvator Mundi, and an “unusual lapse”

On 20 October, Bendor Grosvenor posted an attack, “’Mystery’ over Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’”, on a Guardian article written by Dalya Alberge, “‘Puzzling anomaly’ at heart of £75m artwork”.

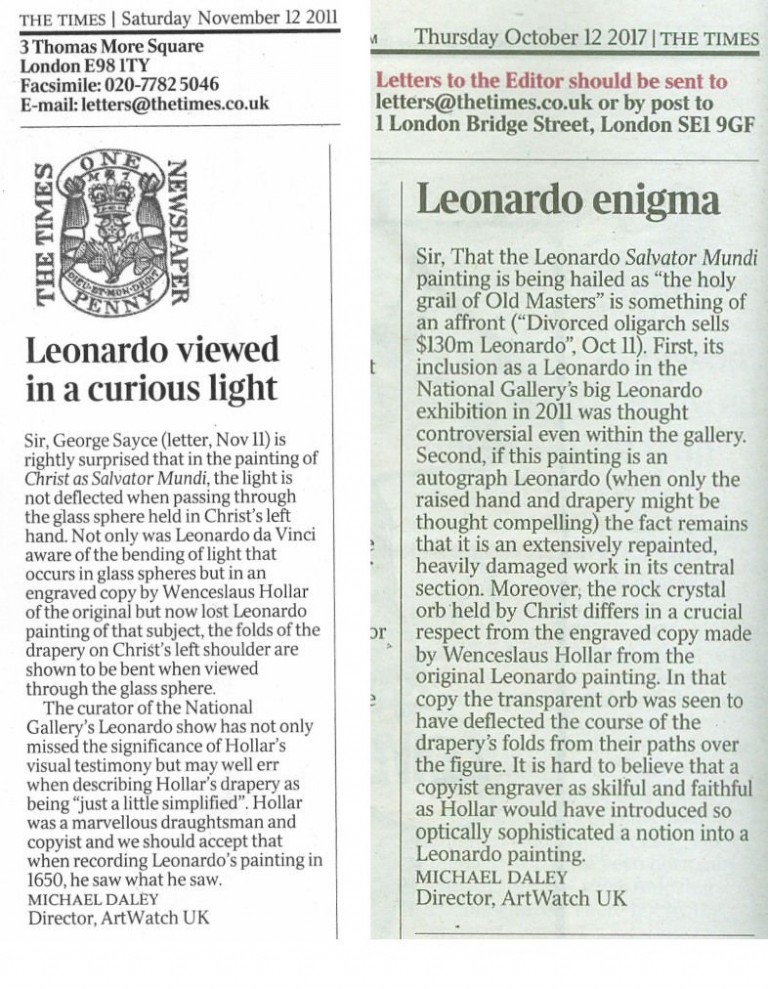

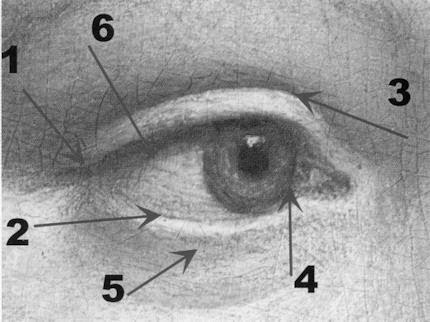

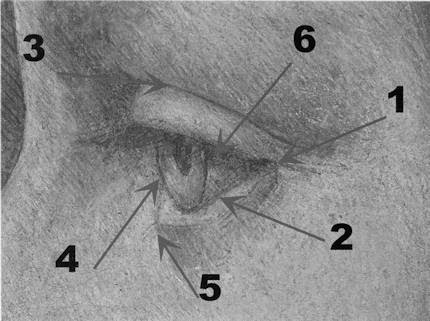

The Guardian piece had reported my views on the viability of the recent attribution to Leonardo of a damaged and re-restored Salvator Mundi painting (Fig. 3 below) and it had noted the addressing of those views by Walter Isaacson in his new book Leonardo da Vinci ~ The Biography. (My concerns had been published in two – unchallenged – letters to the Times: “Leonardo viewed in a curious light”, 12 November 2011, and “Leonardo enigma”, 12 October 2017. See Fig. 1 below).

Grosvenor carries the following passage from Alberge’s article:

“But in a forthcoming study, Leonardo da Vinci: The Biography, Walter Isaacson questions why an artistic genius, scientist, inventor, and engineer showed an ‘unusual lapse or unwillingness’ to link art and science in depicting the orb.

“He writes: ‘In one respect, it is rendered with beautiful scientific precision…But Leonardo failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb.’

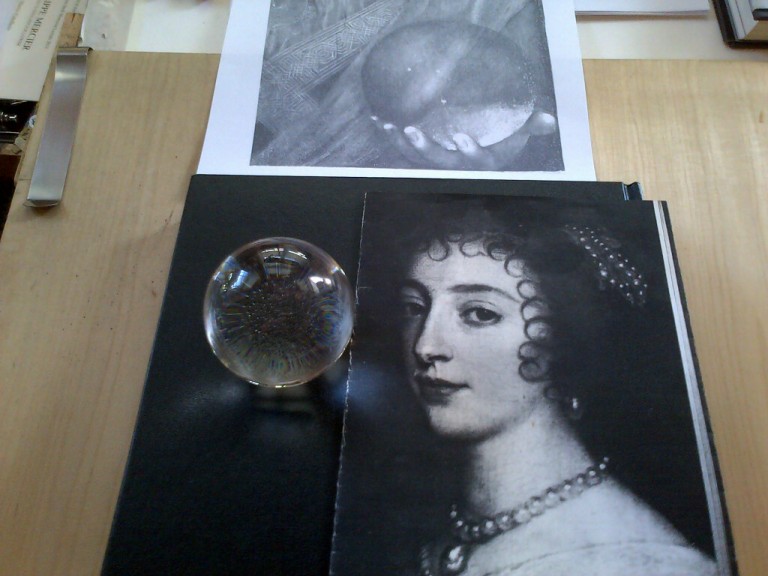

“‘Solid glass or crystal, whether shaped like an orb or a lens, produces magnified, inverted, and reversed images. [See Fig. 4 below] Instead Leonardo painted the orb as if it were a hollow glass bubble that does not refract or distort the light passing through it.’

“He argues that if Leonardo had accurately depicted the distortions, the palm touching the orb would have remained the way he painted it, but hovering inside the orb would be a reduced inverted mirror image of Christ’s robes and arm.”

Grosvenor then contends that:

“All of which might lead you to believe that Isaacson did not think the painting was by Leonardo, or at least was raising serious questions.”

In so claiming, Grosvenor seemed to have overlooked this further passage in which Alberge reports a conversation she had with the author:

“Isaacson said Leonardo filled his notebooks with diagrams of light bouncing around. So did he [Leonardo] choose ‘not to paint it that way, because he thought it would be a distraction…or because he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality’.”

That passage correctly indicates that Isaacson was genuinely perplexed as to why Leonardo had on that occasion not painted in a way that might have been expected, given his great interest and passion for optical laws. It did not say that Isaacson himself had concluded that Leonardo had not painted the picture. However, Grosvenor adds:

“But on his Facebook page, Isaacson writes: ‘Just to be very clear, this article leaves a bit of a false impression. In my new book, I state clearly and unequivocally that the painting of Salvator Mundi is by Leonardo. And I explore the reasons that he did not show the crystal orb distorting the robes of Christ. I say it was a conscious decision on Leonardo’s part. I do not say in my book, nor did I say in the interview, nor do I believe, that anyone but Leonardo painted this painting. I believe he made a decision to paint the crystal orb in a way that is miraculous and not distracting. All of the experts I know agree, from Martin Kemp to Luke Syson.’”

It is not the case that all Leonardo experts endorse the Leonardo attribution. Nor is it apparent why Isaacson might have felt impelled to make such a “lawyered-sounding” statement over what he feared might at most be “a bit of a false impression” but Grosvenor seemed to relish the fact of it:

“So that’s that; nothing to see here. And please don’t be at all persuaded by the attempt, elsewhere in the article, to use Wenceslaus Hollar’s engraving of the Salvator Mundi to cast doubt on the painting. It has been suggested that because the engraving shows some small, in some cases actually imperceptible, differences to the painting at Christie’s, then the painting at Christie’s might not be the painting which was engraved. This is fantasy art history. First, such differences reflect more on Hollar’s ability as an engraver than the painting. Second, compare other examples of Hollar’s engravings with the paintings to which they relate and you will see that he regularly altered aspects of the composition. Third, we cannot know how long Hollar had to study the original. Finally, Hollar saw the painting more than one hundred years after it was painted. Who knows what might have happened to it in that period?”

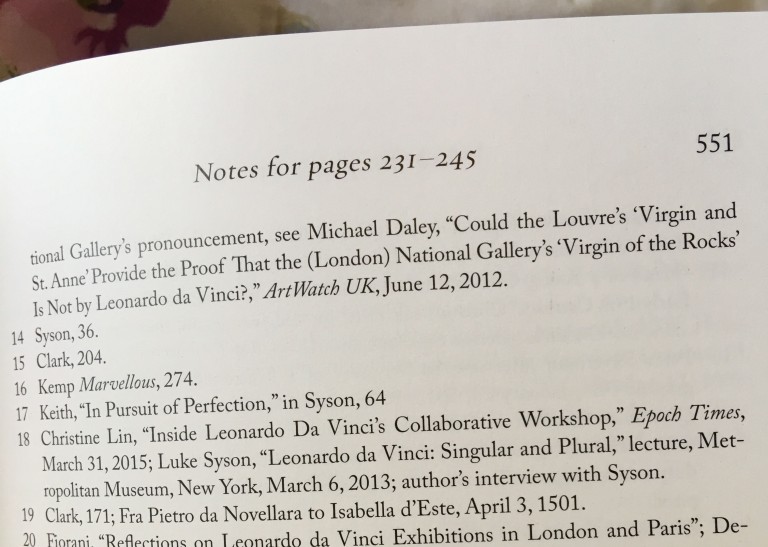

Grosvenor’s strained disparagement of Hollar’s engraved testimony (“small, in some cases imperceptible”) alludes to quoted remarks of mine in the Guardian article and to my 12 October Times letter (“Leonardo enigma”). Coming as this does from a man who has likened himself to a Mozart among Salieris in the art dealing, sleeper-hunting community, it may require a response consisting of the very clearest visual evidence. Such will follow in a later post. Here, it might be noted that although my position is certainly not shared by Isaacson, it was not disparaged by him in his book. To the contrary, during his interview for the Guardian article he generously acknowledged having been prompted by my views to raise the very question of why Leonardo might have painted the orb in such a strikingly unexpected fashion. In addition, he cited our 12 June 2012 article “Could the Louvre’s ‘Virgin and St Anne Provide the Proof that the (London) National Gallery’s ‘Virgin of the Rocks’ Is Not by Leonardo da Vinci?”. (See Fig. 2 below.)

CODA – Walter Isaacson on the Salvator Mundi in his Leonardo da Vinci ~ The Biography:

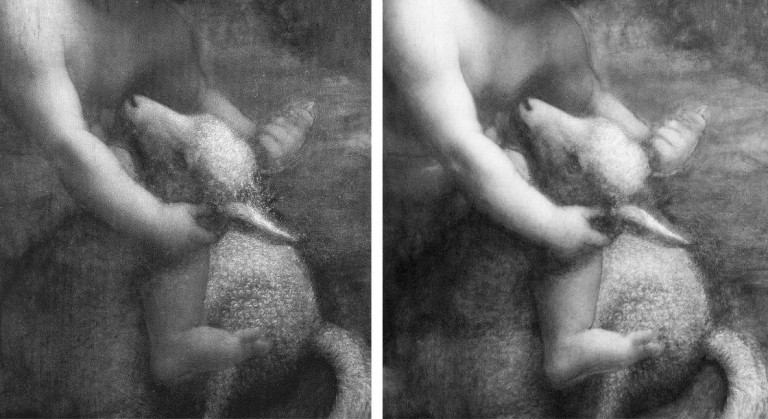

“There is, however, a puzzling anomaly in the painting [see Fig. 3 above], one that seems to be an unusual lapse or unwillingness by Leonardo to link art and science. It involves the clear crystal orb that Jesus is holding. In one respect, it is rendered with beautiful scientific precision. There are three jagged bubbles in it that have the irregular shape of the tiny gaps in crystal called inclusions.

“Around that time, Leonardo had evaluated rock crystals as a favor for Isabella d’Este, who was planning to purchase some, and he captured accurately the twinkle of inclusions. In addition, he included a deft and scientifically accurate touch, showing he had tried to get the image correct: the part of Jesus’ palm pressing into the bottom of the orb is flattened and lighter, as it would indeed appear in reality. But Leonardo failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb. Solid glass or crystal, whether shaped like an orb or a lens, produces magnified, inverted, and reversed images. Instead, Leonardo painted the orb as if it were a hollow glass bubble that does not refract or distort the light passing through it. At first glance it seems as if the heel of Christ’s palm displays a hint of refraction, but a closer look shows the slight double image occurs even in the part of the hand not behind the orb; it is merely a pentimento that occurred when Leonardo decided to shift slightly the hand’s position. Christ’s body and the folds of his robe are not inverted or distorted when seen through the orb. At issue is a complex optical phenomenon. Try it with a solid glass ball [see our demonstration at Fig. 4 below]. A hand touching the orb will not appear to be distorted. But things viewed through the orb that are an inch or so away, such as Christ’s robes, will be seen as inverted and reversed. The distortion varies depending on the distance of the objects from the orb. If Leonardo had accurately depicted the distortions, the palm touching the orb would have remained the way he painted it, but hovering inside the orb would be a reduced and inverted mirror image of Christ’s robes and arm.

“Why did Leonardo not do this? It is possible that he had not noticed or surmised how light is refracted in a solid sphere. But I find that hard to believe. He was, at the time, deep into his optics studies, and how light reflects and refracts was an obsession. Scores of notebook pages are filled with diagrams of light bouncing around at different angles. I suspect that he knew full well how an object seen through a crystal orb would appear distorted, but he chose not to paint it that way, either because he thought it would be a distraction (it would indeed have looked very weird), or because he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality to Christ and his orb.”

Michael Daley, 23 October 2017

A memorial lecture, two journals and an assault on scholarship

‘Never trust the teller trust the tale’, cautioned DH Lawrence. He meant: don’t pay attention to what anyone tells you about a work of art, not even the artist; nor, we might add, a ‘curator of interpretation’. Study it yourself. But can we always trust the evidence of our own eyes?

THE ANNUAL JAMES BECK MEMORIAL LECTURE: ‘Never trust the teller trust the tale’

On 7 November the ninth annual ArtWatch International James Beck Memorial Lecture will given by Robin Simon and held in Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W. 1. Robin Simon is Honorary Professor of English at University College, London, and the editor of The British Art Journal, which esteemed publication has launched an attack on the prohibitively high fees that museums now charge scholars for reproducing works of art – even when, as often, these are publicly owned and out of copyright – in their publications and lectures (- see below “A licence to print money, a licence to kill scholarship, at the Tate, the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery”). His recent books include Hogarth, France and British Art and (with Martin Postle) Richard Wilson and the Transformation of European Landscape Painting. Professor Simon writes:

‘Never trust the teller trust the tale,” cautioned DH Lawrence. He meant: don’t pay attention to what anyone tells you about a work of art, not even the artist; nor, we might add, a ‘curator of interpretation’. Study it yourself. But can we always trust the evidence of our own eyes?

Above, Mars chastising Cupid by Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582–1622), 1613. Art Institute of Chicago.

For details of the (evening) lecture and tickets, please contact Helen Hulson at:hahulson@gmail.com.

THE ARTWATCH UK JOURNAL AND THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2015 CONFERENCE ‘ART, LAW AND CRISES OF CONNOISSEURSHIP’

Later this month we publish the ArtWatch UK members’ Journal No. 31. It comprises 112 pages and contains the full and illustrated proceedings of the 5 December 2015 conference “Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship” organised by ArtWatch UK, the Center for Art Law, New York, and LSE Law – see below. It will be followed in December by issue No. 32, a special edition on Michelangelo. The ArtWatch UK Journal, is not sold but is distributed free to all members. For membership details please contact Helen Hulson at: hahulson@gmail.com.

A LICENCE TO PRINT MONEY, A LICENCE TO KILL SCHOLARSHIP, AT THE TATE, THE BRITISH MUSEUM AND THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

The British Art Journal (XVIII, 1 2017) editorial in full:

Compare two statements, beginning with the National Gallery of Art, Washington:

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART. OPEN ACCESS POLICY FOR IMAGES OF WORKS OF ART PRESUMED IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN.

‘With the launch of NGA Images, the National Gallery of Art implements an open access policy for digital images of works of art that the Gallery believes to be in the public domain. Images of these works are now available free of charge for any use, commercial or non-commercial. Users do not need to contact the Gallery for authorization to use these images. They are available for download at the NGA Images website (images.nga.gov).’

Now the Tate:

‘One of Tate’s core goals is to promote enjoyment of, and engagement with, art and artists within our collection, to audiences wherever they are in the world. As part of this, we are releasing some of our Archive collection digital content and some items from our main Collection for use for non-commercial and educational purposes under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported) licence. The aim is to provide a simple, standardised way to grant copyright permission for the use of Tate’s intellectual property (its photography) and artists’ creative work for specific uses only, whilst safeguarding Tate’s own income from its IP in commercial contexts whilst ensuring artists, copyright holders and Tate get credit for their work and are protected by law.’

And so what, then, is ‘commercial’ use? The Tate begins:

‘Creative Commons defines commercial use as “reproducing a work in any manner that is primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or monetary compensation”.’

Unfortunately for the Tate, this does not suit it at all, since no-one could argue that academic work in particular is ‘primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or monetary compensation’. If it were to be excluded, the Tate would not be able to seize fees for the vast majority of publishing about its collections. And so it simply invents its own definition, even while still invoking the Creative Commons licence, bringing academic (and indeed any other) work within ‘commercial use’, as follows:

‘Tate further defines commercial use… [our italics] [as] use on or in anything that itself is charged for [! our exclamation], on or in anything connected with something that is charged for, or on or in anything intended to make a profit or to cover costs [we are running out of !s]… Tate would usually regard the following uses of Tate imagery as commercial activity: use online or in print by commercial organisations, including (for the avoidance of doubt) trading arms of charities; use on an individual’s website in such a way that adds value to their business, or for promotional purposes, or where offering a service to third parties; use of images by university presses [we can afford one more !] in publications online or in print; use in publicity and promotional material connected with commercial events; unsolicited use of images by news media, including front covers and centre-page spreads; use in compilations of past examination papers; use by commercial galleries and auction houses.’

And so any publication, however useful to the Tate in expanding public knowledge and understanding of works in the collection, if it is to avoid the hefty fees that the Tate imposes, must needs be handed out free and never, ever, published by a university press… This attitude is disgraceful. Alas, the British Museum, which under Neil MacGregor and Antony Griffiths had a praiseworthy free use of images in Prints and Drawings, has followed the Tate’s lead and now invokes a Creative Commons licence with the purpose of imposing reproduction fees, as does the National Portrait Gallery.

The Tate has given up on attempts to assert copyright in works of art that are actually out of copyright, and instead asserts that it is now, rather, protecting the copyright of its photographs of those works, defining them as its ‘intellectual property’ (IP) in what is meant to be a nifty sidestep. That cannot, however, avoid the fact that, as we have pointed out in these pages, this is unsound in law, in view of the purely mechanical nature of the image-recording operation. Fascinatingly, the NPG seems to have a different understanding of the matter, asserting in a letter in response to an enquiry about it:

‘The National Portrait Gallery owns the copyright of the majority of the images in its collection. Even if an image is “out of copyright”, as it is still part of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, then copyright continues to be managed by the Gallery.’

This runs directly contrary to copyright law defined in the NPG’s own ‘Introduction to copyright’, as follows:

‘Under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended), copyright protects original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works; films; sound recordings; broadcasts and typographical arrangements… Copyright usually lasts for the creator’s lifetime, plus the end of 70 years after their death.’

Precisely. We note that works under copyright must be ‘original’ in UK law. But the photographs of works in these collections, if they are to the job they are required to do, must needs exclude originality and remain precisely faithful to, yes, the original works – most of which are, of course, out of copyright.

The adoption of Creative Commons licences has nothing to do with the law of copyright in the UK. It is simply a device adopted in order to allow the museums to continue to charge for the reproduction of out-of-copyright works of art in their care, which, moreover, belong to the public they are charging for use. There seems, frankly, no good reason for this restrictive practice if these museums are indeed concerned, as the Tate puts it, ‘to promote enjoyment of, and engagement with, art and artists’. Could it be, then, that its purpose is to perpetuate the employment of the gallery staff who collect the money? Any fees collected will be largely cancelled out by costs: salaries, administration, office space, equipment, pensions and so on. Any profits are likely to be minimal and of no real help to the institution: but they are obtained at the greatest possible cultural and educational cost.

For a museum that is not a profit; it is a loss.

For whose benefit do these museums exist? Do they exist for the benefit of the staff who run them or for that of the public and the world of knowledge they were created to serve? Do they aim to enhance knowledge of their collections? If so, why do they go out of their way to penalize any publication or form of dissemination of images that does that work for them? The use of images of works of art in ‘news media… front covers’ or even on biscuit tins, bathmats or shower curtains, all serve the same purpose, which, to repeat, the Tate defines as ‘to promote enjoyment of, and engagement with, art and artists’.

Strange to say, these ‘Creative Commons’ licences originate in the USA where, however, the position, as set out by the NGA above, is clear and simple, and directly contrary to that of these UK museums. No wonder the Tate has to add so many subordinate clauses and pseudo-legal assertions to the provisions of the Creative Commons licence it invokes.

It would be a far, far better thing if these pointlessly rapacious museums in the UK adopted a different, transatlantic, model: that of the National Gallery of Art in Washington and of countless other museums throughout the USA. What are they afraid of?

And who pays for digitizing their images? It so happens that the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art handed out it largest ever grant, £500,000, to the British Museum to digitize its British drawings, surely not with the intention that the museum might now charge for their use. The Mellon Centre’s parent institution is the Yale Center for British Art – where images of artworks in the collections are offered free for any purpose.

To return to the Tate… If, say, you look up Arthur Melville on the Tate website you will find that his biography, far from being written by a curator, as one might hope, is simply a link to Wikipedia. By what right? Yes, by yet another Creative Commons licence which, luckily for the cynical Tate, states on the Wikipedia site that anyone may ‘share… copy, distribute and transmit the work… for any purpose, even commercially.’

Now that sounds like a sensible licence.

Michael Daley, 17 October 2017

The (not so-new) latest New Leonardo Discovery

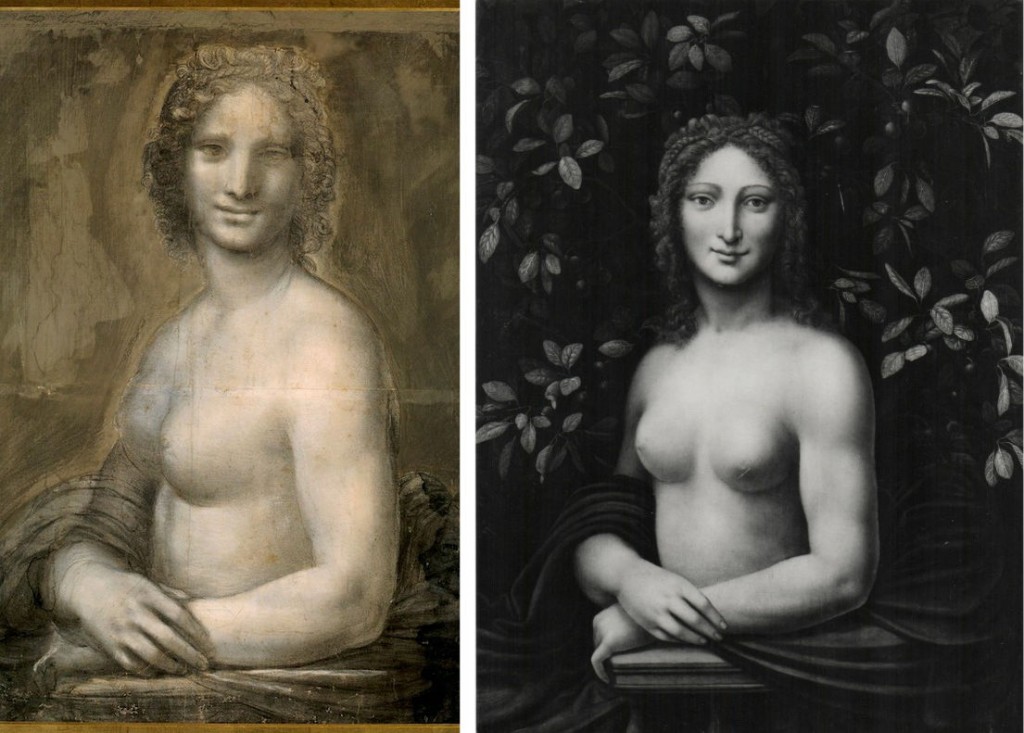

On 29 September it was widely reported that researchers at the Louvre now believe that a drawing at the Musée Condé in Chantilly – the so-called “Joconde nue” – to be Leonardo’s lost preparatory nude study for the Mona Lisa.

The claimed discovery seemed bold and unleashed global coverage – see, for example, the BBC’s ‘Mona Lisa nude sketch’ found in France, National Geographic’s ‘Nude Mona Lisa’ Sketch May Have Been da Vinci’s, and Fortune’s ‘Historians Think They’ve Found a Nude Drawing of Mona Lisa’

In reality, this latest New Leonardo Discovery is a warm-up of an old, on-the-record, attribution. In 1988 Jacques Franck, the art historian/painter trained in Old Master techniques (and a current restoration adviser to the Louvre), had closely examined the Joconde nue in the Château of Chantilly along with Amélie Lefébure, former Head curator of the Musée Condé, and Dominique Le Marois, a restorer in the French museums. At that date the drawing had long been considered the work of an anonymous Leonardo imitator and contemporary but on close visual examination Franck concluded that it was mostly executed by Leonardo and he advised the then director of the Chantilly Estate, Prof. Germain Bazin, accordingly. His (written) ascription was accepted by leading Leonardo specialists, including Profs. Bazin and René Huyghe.

Above, Fig. 1: Here attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, Joconde nue, c. 1500-1506 ?, black chalk on brown prepared paper, 72 x 54 cm. Chantilly, Musée Condé, Inv. 32 (27).

Above, Fig. 2: a detail of Joconde nue (as published showing prick marks when the design was transferred for use on panel.)

Because the Joconde nue had been heavily retouched over the centuries and rendered barely legible in many sections, some thought it necessary that it be subjected to a wide range of forensic tests. This was rejected by Prof. Bazin for fear that, should the work be widely accepted as a true Leonardo, it would then undergo a drastic and likely harmful cleaning. Although forensic investigations have improved significantly in the last thirty years, that risk remains. On his personal recollections of the sheet and in the light of the restorer M. Le Marois’s alarming and still extant 1988 condition report, Franck now fears that an essentially technical underpinning of the Leonardo ascription will prompt further and more invasive technical interventions. He tells AWUK:

“The Joconde nue’s authentication by scientific means will be quite a challenge to the Louvre’s laboratory. For sure they will be able to check the paper and date it correctly, yet the materials in themselves cannot establish that the drawing is the work of Leonardo himself as opposed to that of a close disciple. The composition has been considerably harmed by apocryphal retouchings and the pricking for transfer onto a panel to get an oil painting out of it [See Fig. 2 above and Fig. 5 below]. Further, at a later date, possibly in the 19th century, some thick aqueous paint was applied to the background in order to conceal various alterations (stains, rings, etc.). As a result, many of the forms are hardly legible in terms of Leonardo’s artistic standards.

“The brutal interference of the alterations with the impalpable modelling on which Leonardo’s overall drawing is based has grossly denatured it. When I realized this, I intended to clean the work ‘virtually’ by reconstructing the drawn composition as closely as possible to what it had once been. The task would have been huge but this reaffirmation of my conclusions on the drawing’s status provides a compelling and urgent occasion for that task to be undertaken soon. The growing conceit of restorers that they can recover original states that have been largely subsumed within alien and deleterious additions has repeatedly been shown to be foolhardy with Leonardo.”

As in 1988, the authenticity of the Chantilly cartoon should stand or fall today on the strength of its aesthetic force and originality, which is to say: as seen by eye and not on the basis of some technical analysis of the drawing’s component material innards. Nearly three decades ago Jacques Franck felt that he had seen enough with his trained draughtsman’s eye to make a firm ascription to Leonardo (as was reported in letters to the then director) and today he recalls that:

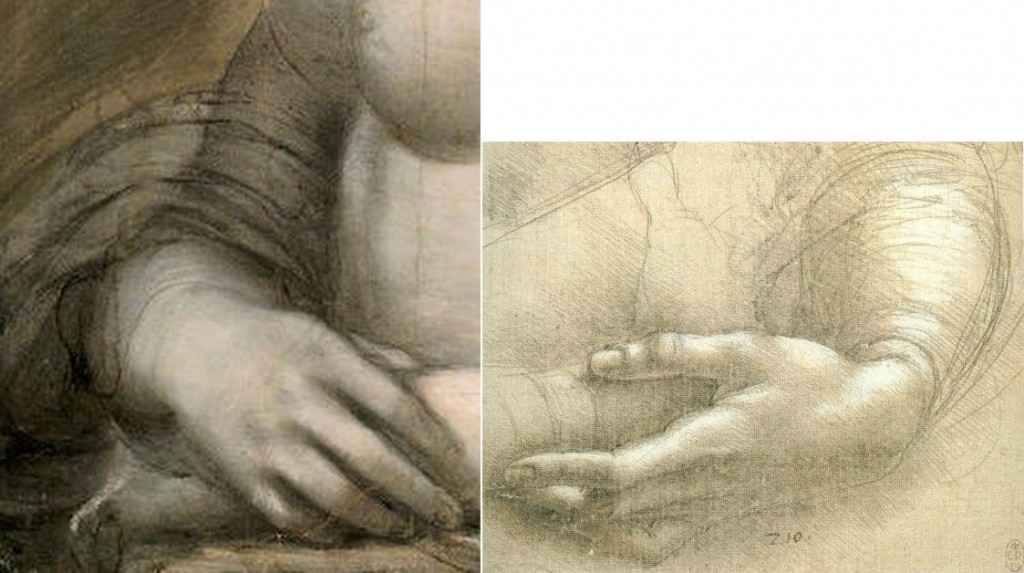

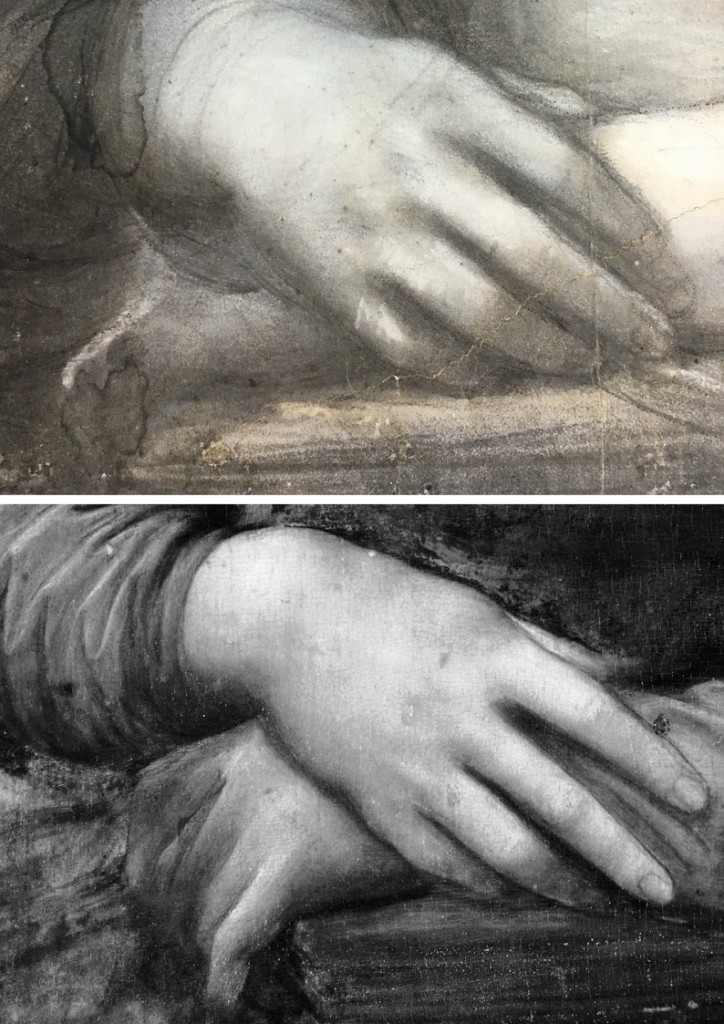

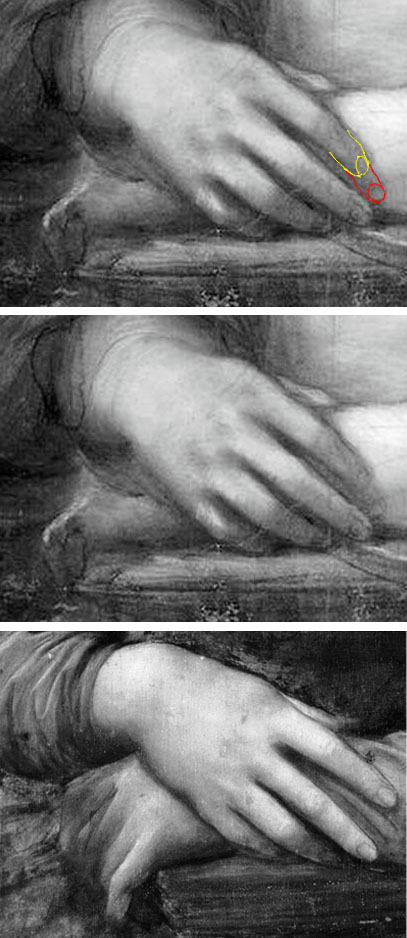

“Besides the characteristics of Leonardo’s late style visible in so many chalk drawings (either red or black), kept notably in the Queen’s collections at Windsor, what struck me at once was the hands. Their execution reminded me of the underdrawing of the Mona Lisa’s own hands in the Louvre picture as revealed in infrared light [See Figs. 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8]. Although such forensics weren’t as developed in 1988 as they are now, at the time the extant infrared images of the Mona Lisa [see Fig. 7 for a more recent image] were defined well enough to help my eye notice that extraordinary resemblance between the painted and drawn hands at first glance. Leonardo had clearly used a very fine brush to trace the contours of the fingers in the cartoon and the painting, hence the thin outlines to be seen in the fingers in both. This similarity isn’t mere chance, it simply means that the hands and, of course the rest of the cartoon is indeed a Leonardo work. Also, the Joconde nue’s forefinger was obviously longer at the outset [Figs. 7 and 8] but Leonardo changed his mind and reduced its length afterwards using wash, exactly as it is in the Louvre picture now. A crucial pentimento probably meaning that the Chantilly cartoon preceded the painted version of the famous portrait.”

Above, Fig. 3: (left) Leonardo da Vinci, Studies of hands, c. 1480-81, silver-point on pink prepared paper, Windsor Castle, Royal Library, n° 12616; (right) a section of Leonardo da Vinci, the Adoration of the Magi, 1480-81, oil on wood panel, 246 x 243 cm. Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Inv. 1890 : n° 1594.

Above, Fig. 4: (left) a detail of the hands of Joconde nue, at Fig. 1; (right) Leonardo da Vinci, Studies of a woman’s hands, c. 1478 (?), silver-point, heightened with white on pink prepared paper, 21. 5 x 15 cm. Windsor Castle, Royal Library, n° 12558.

Above, Fig. 5: (left) Joconde nue; (right) After Leonardo da Vinci, Joconde nue as Primavera, 16th century (?), 89 x 65 cm. Switzerland, private collection (formerly Mackenzie collection).

Above, Fig. 6: a detail of Joconde nue showing prick marks used for transferring the design, and, the artist’s revision and shortening of the index finger.

Above, Fig. 7: (top) the revised right hand of Joconde nue and (bottom), by way of comparison, a circa 2004 Louvre infra-red image (all rights reserved) of the right hand of the Mona Lisa.

Above, Fig. 8: showing (top) the revised right hand of Joconde nue with the first state of the forefinger indicated in red and the revised state indicated in yellow – graphic by Gareth Hawker; (centre) the right hand of Joconde nue and, by way of comparison, (bottom) the right hand of the Mona Lisa as seen in the Louvre infra-red image at Fig. 7.

Michael Daley, 3 October 2017

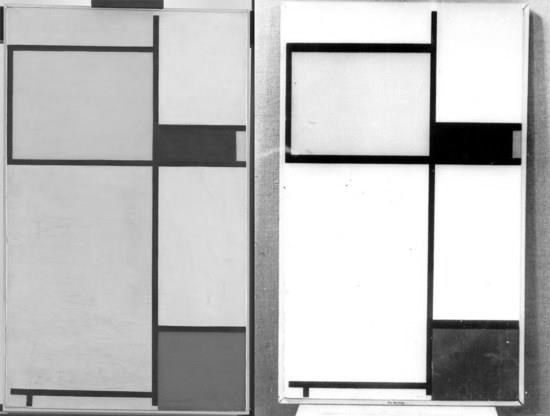

Mondrian, Schmondrian – another lapse of museum expertise

Another day, yet another herd of museum experts are bitten by a work that should not, on a cursory glance, have been taken as what it purported to be.

Yesterday Nina Siegal reported in the New York Times (‘It Might Have Been a Masterpiece, but Now It’s a Cautionary Tale’) on the mega-embarrassment of museum experts at the Bozar Center for the Arts in Brussels, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland, who had all taken on trust a work of unexamined provenance owned by an anonymous private collector who lives in Switzerland. As Ms Siegal puts it:

“What started out as a potentially major cultural discovery now turns out instead to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of presenting works of art owned by private collectors that have not been systematically vetted. In this case, art experts seem to have passed the buck on conducting basic due diligence on the artwork before displaying it as a Mondrian — putting their own reputations on the line because they gave such credence to a private collector.”