Exhibition: Sargy Mann, Late Paintings

A most remarkable exhibition is running until March 10th at the Royal Drawing School (19–22 Charlotte Road, London EC2A 3SG).

Can a blind man paint? We would not ask if a blind man could think or feel. Sargy Mann saw, felt and thought when sighted. In a sighted painter, thinking and feeling are intensified by habit, by professional engagement and by sheer practice. By the concentrated act of painting, thoughts and feelings are imprinted, stored and collated in the mind and thereby provide templates and springboards for further artistic skirmishes. Mann showed through failing and eventual complete loss of sight that art is driven by minds; that powers honed through a lifetime’s practice are primarily imaginative, conceptual and, by no means, exclusively sight-dependent; that even a catastrophic loss of visual powers cannot thwart artistic will; that an artist’s mind is supreme.

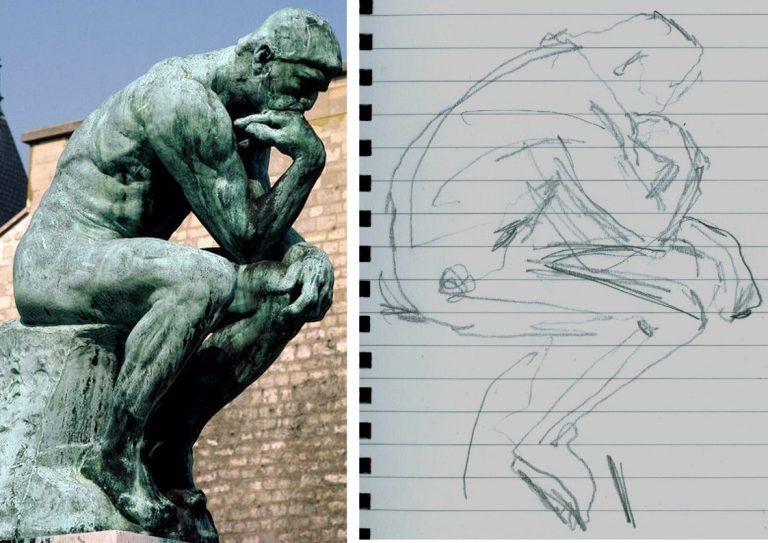

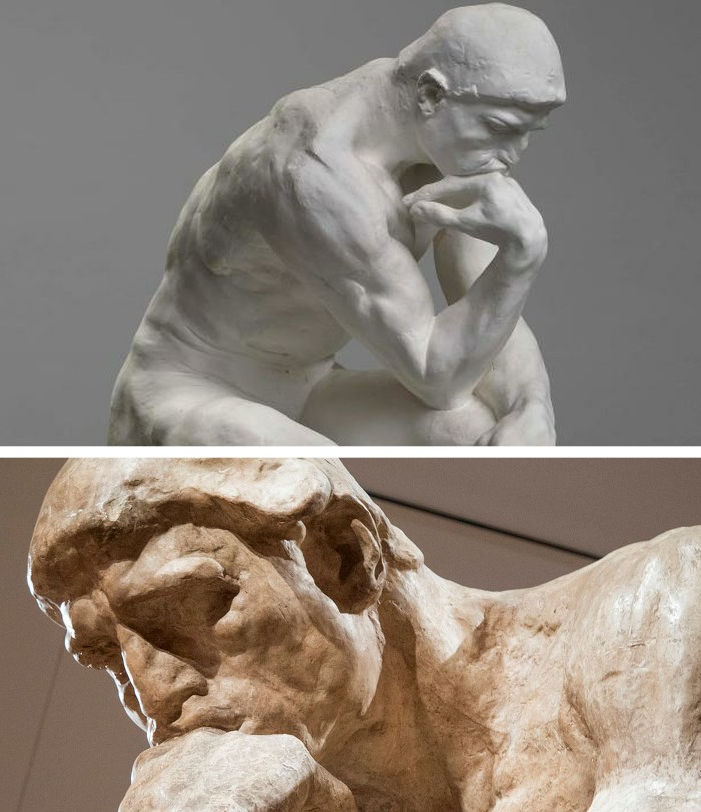

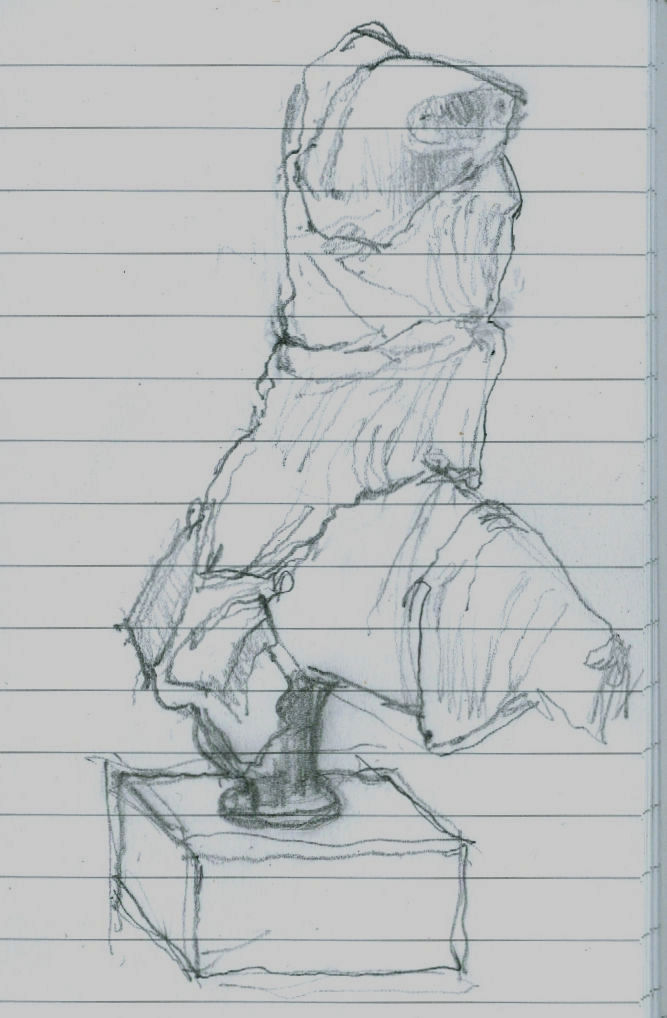

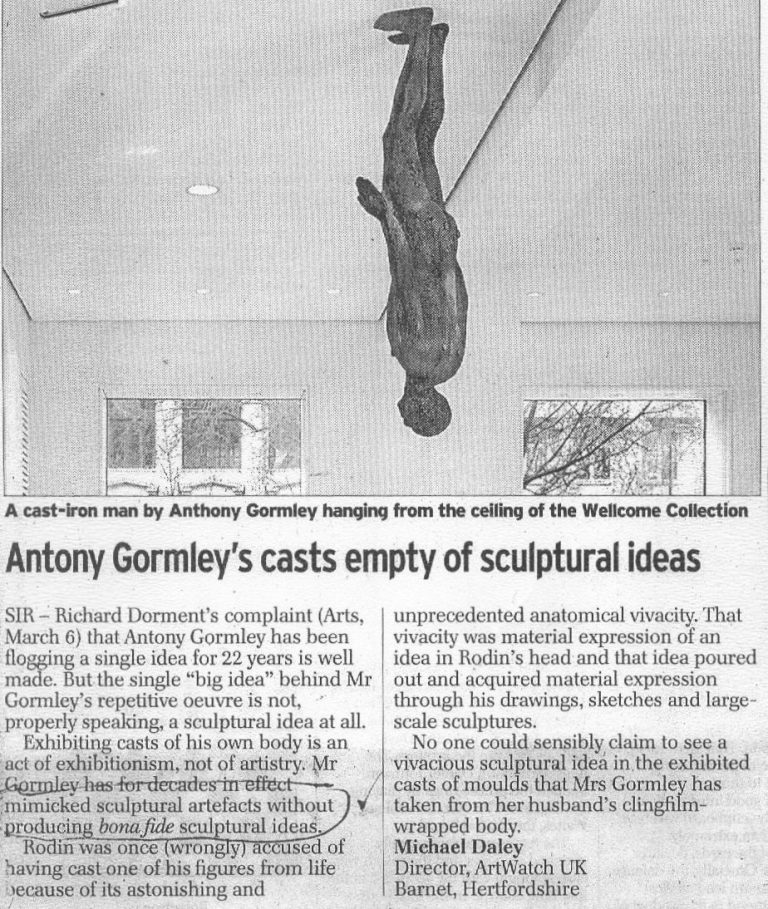

Sargy Mann (1937-2015) continued painting for the last ten years of his life after becoming completely blind. We know that an artist can draw with his eyes shut; can draw unseen objects from memory; can draw non-existent imagined objects. Rodin made drawings without taking his eyes off moving figures so as to fix their transient, momentary essentials by a felt but, at the moment of execution, unobserved drawing. A newspaper illustrator once had to make drawings of actors in character during opening-night performances. Because being seen drawing would have constituted an offensive distraction, he carried a short pencil and a small sketchbook in a jacket pocket and drew, hand-in-pocket, as he looked, recording and fixing features in his mind’s eye. Afterwards, he was able to produce finished caricatures for publication from his un-seen but physically recorded observations and notations. We know, of course, that composers can write music when deaf. We have long known that artists have adapted variously to declining levels of sightedness. As Degas lost sight he turned from the depiction of figures to plastic realisations of them – but, then, he had also once claimed that he would have preferred to make his fabulous dancer drawings in monochrome and had only added pastel colours to encourage their sales.

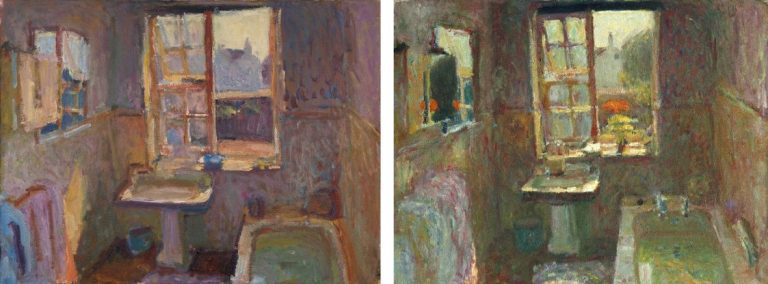

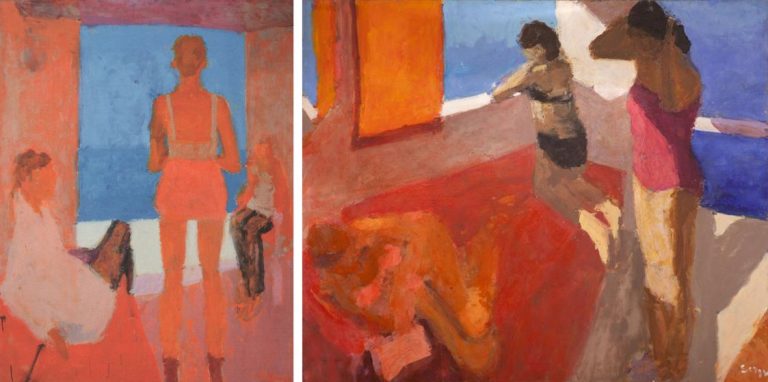

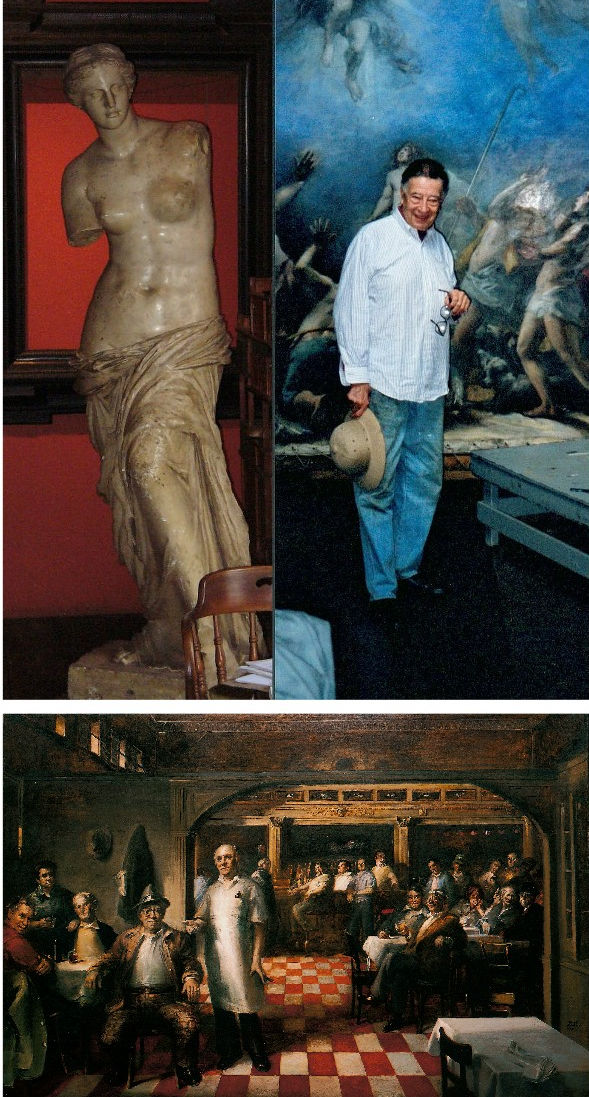

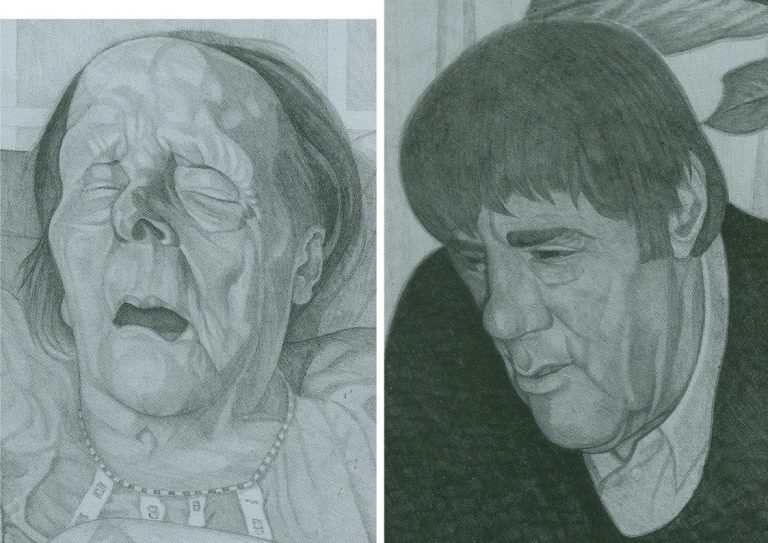

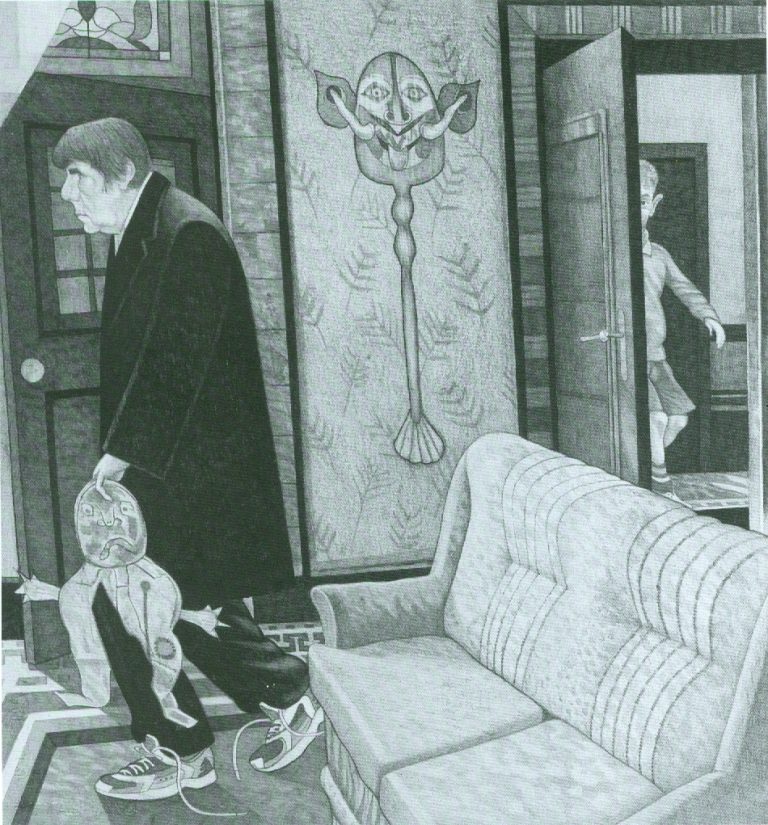

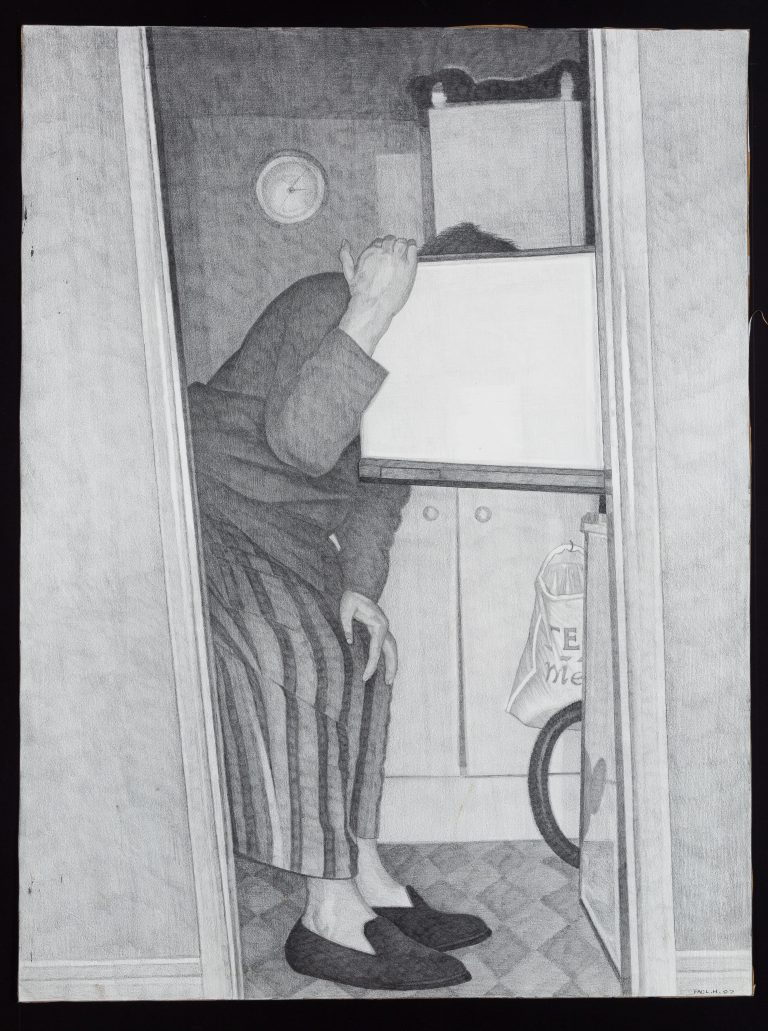

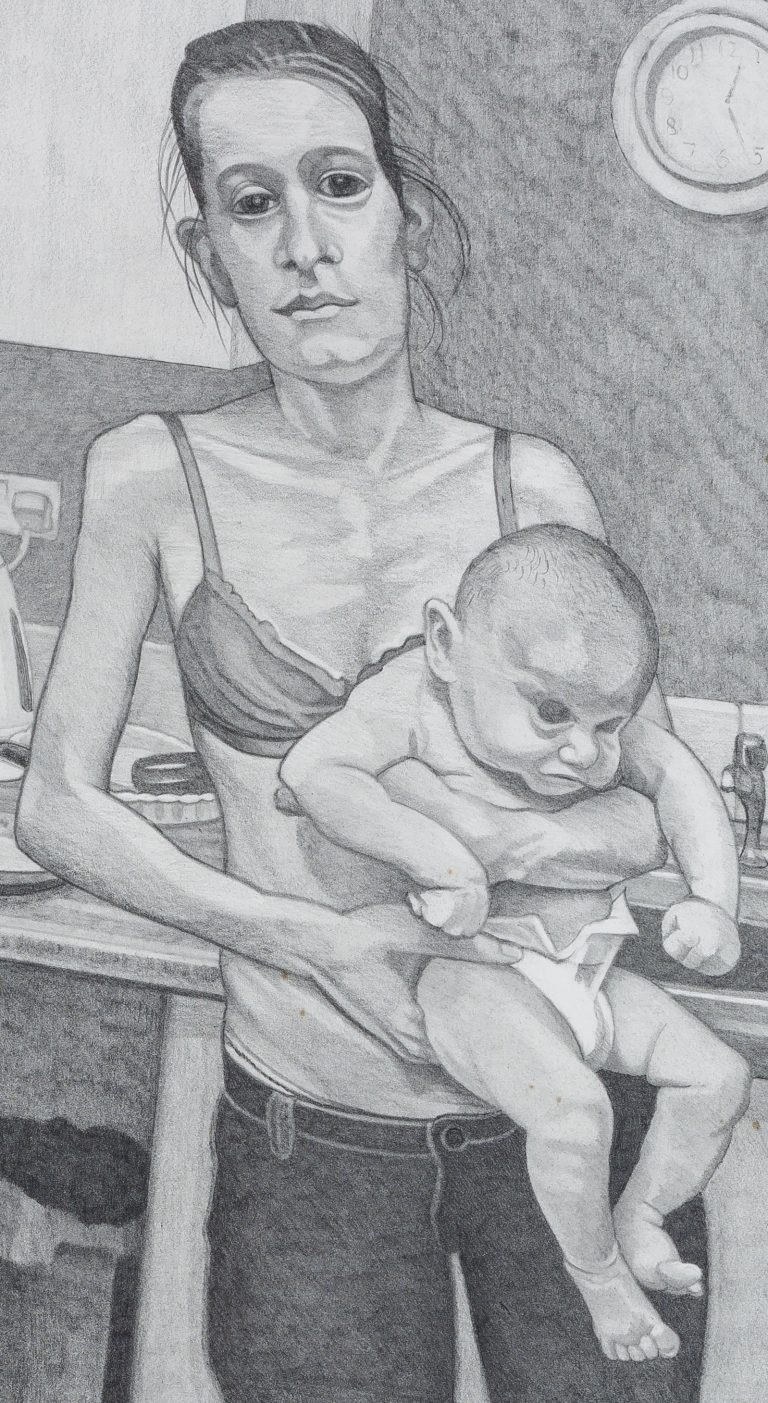

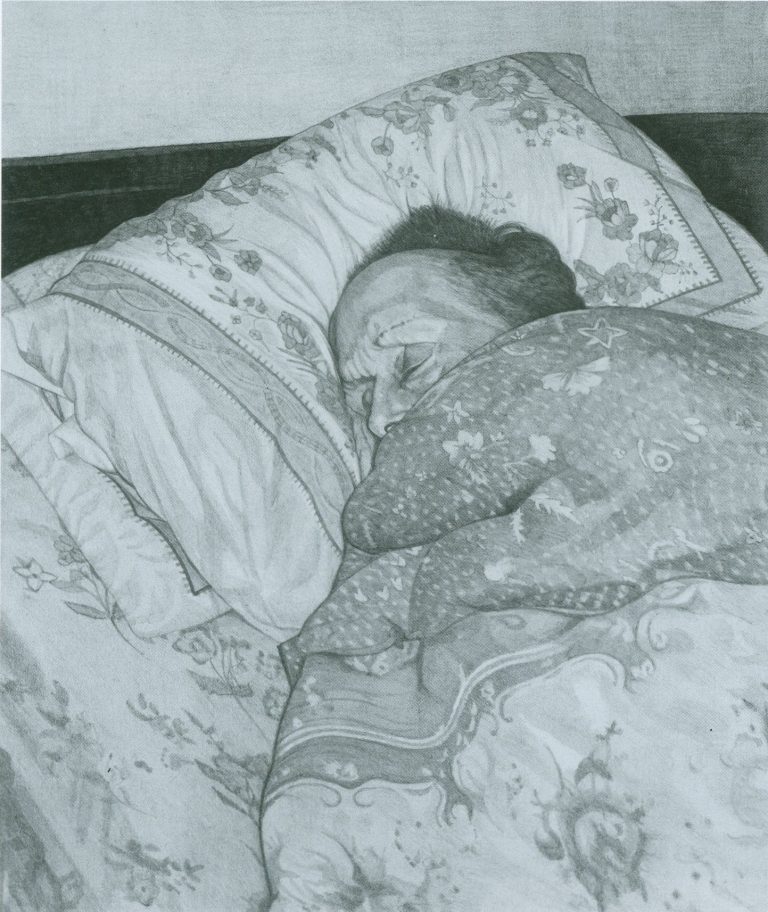

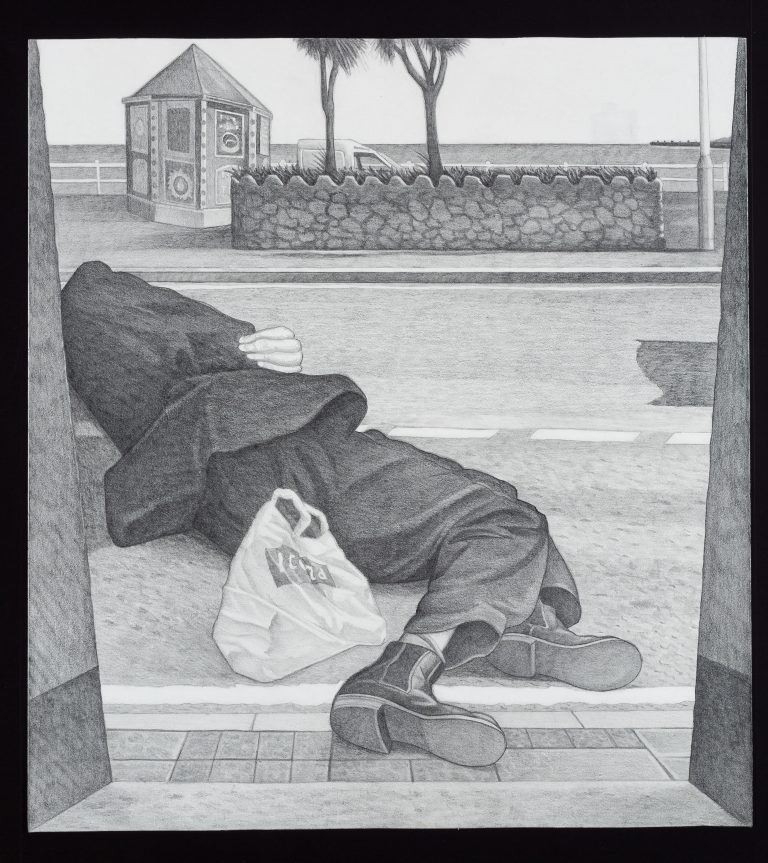

This exhibition of a blind man’s late paintings testifies to a remarkable artist and artistic intelligence no less than to a tenacious and courageous spirit. Mann’s works, writings and lectures can be seen in an excellent dedicated archive but, if at all possible, this handsome sensitively arranged exhibition should not be missed. In it, the viewer can stand before the often large canvases and in, as it were, the very space which Mann had occupied when painting his spatially and pictorially arranged figures as if seen from nature when in fact deduced from tactile/spatial awareness and recollected experiences. It must have been the case that Mann was proceeding in many respects as before when sighted – certainly, there had always been a strong “mapping” organising and orchestrating imperative in Mann’s painting as well as his highly attuned receptivity to light-generated colours and surfaces, as can be seen in figs. 2 and 3 below.

One might have imagined that with the complete loss of sight, engagement with the transient, perpetually shifting consequences and effects of light would, of necessity, have atrophied. Not so. With Mann, in a most unprecedented and unexpected development, as the figures became more classically affirmative, self-contained and monumental, so too, the colour chords intensified to a remarkable vibrancy and forcefulness as seen below at Figs. 4 and 5. This is not an exhibition to miss but it does close on the tenth of this month.

CODA

Sargy Mann (above) was an early and long-supportive member of ArtWatch. His exceptionally acute art critical intelligence and conceptual adroitness was well in evidence when, in 2000 with already failing sight, he produced the cautionary essay below on the shoals and perils of restoring drawings:

Michael Daley, Director, 7 March 2019

The Louvre Museum’s bizarre charge of “fake information” on the $450 million Salvator Mundi

The Louvre Museum in Paris has attacked one of its own named Leonardo restoration consultants – Jacques Franck – with professional disparagement and an allegation of having conveyed “fake information”.

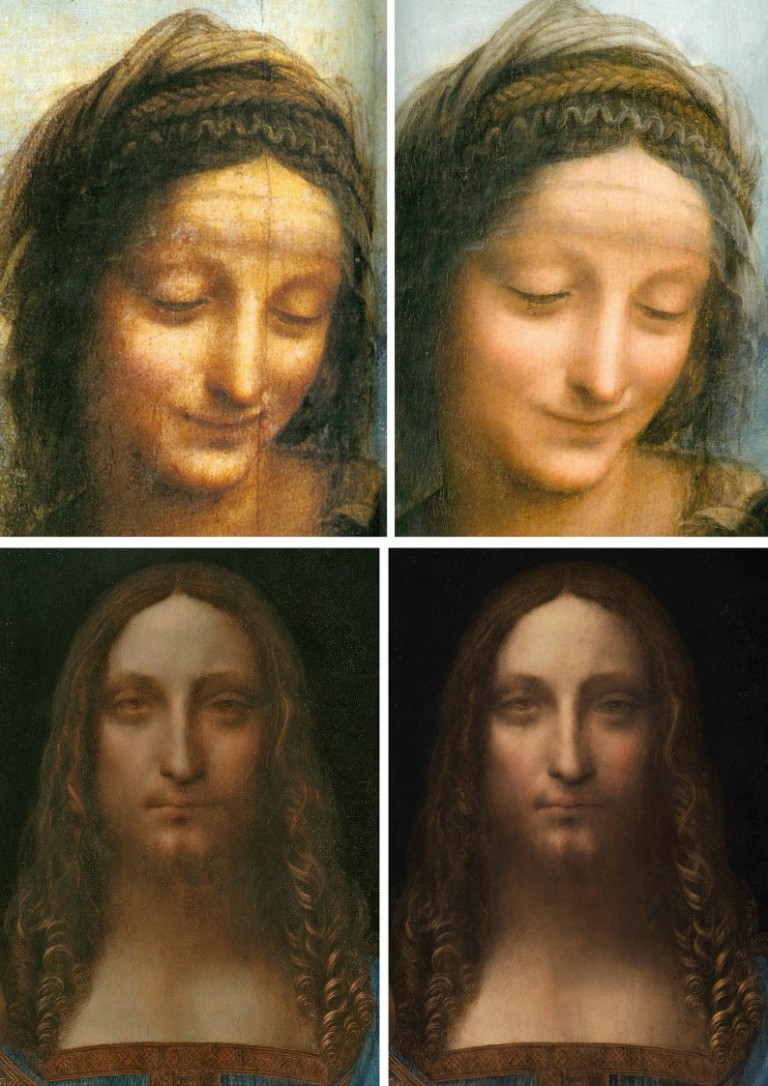

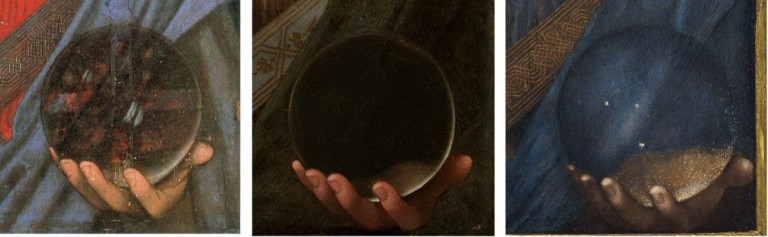

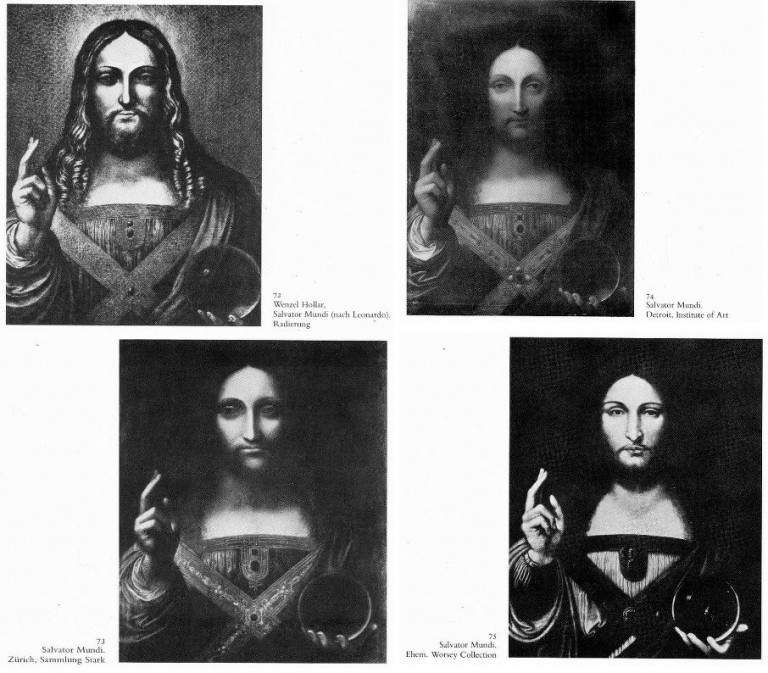

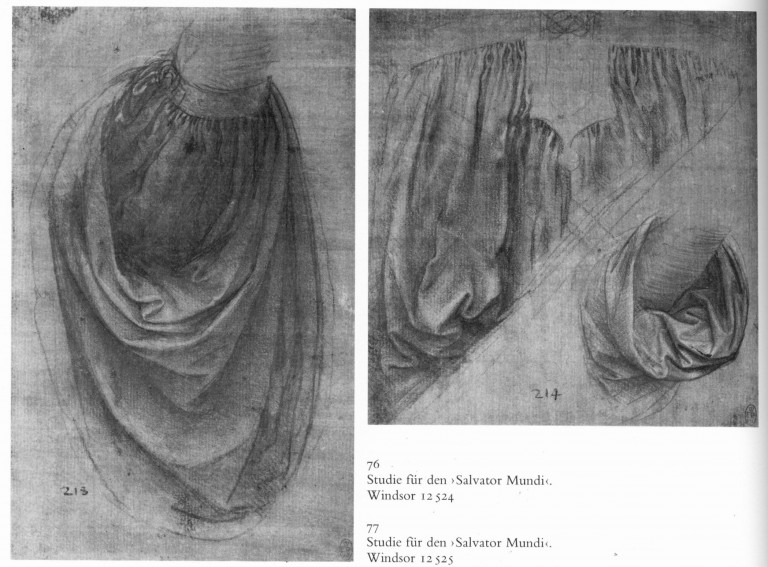

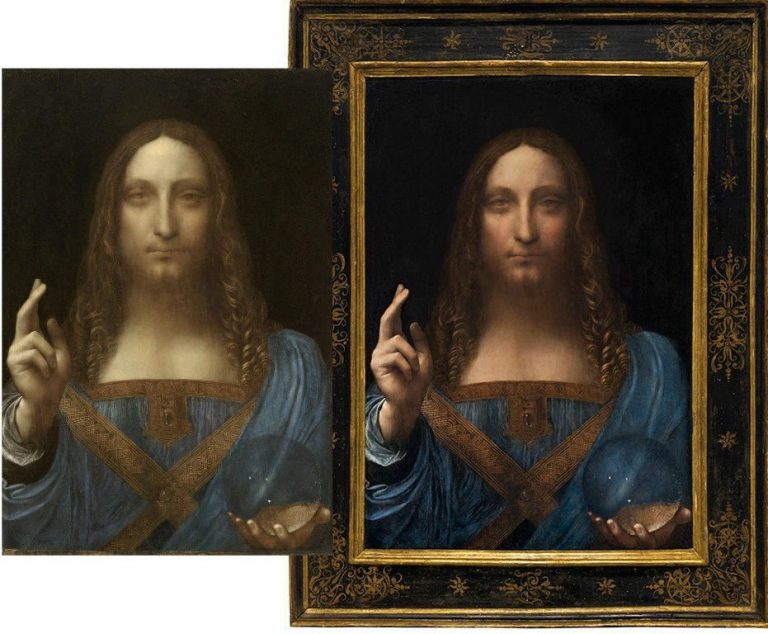

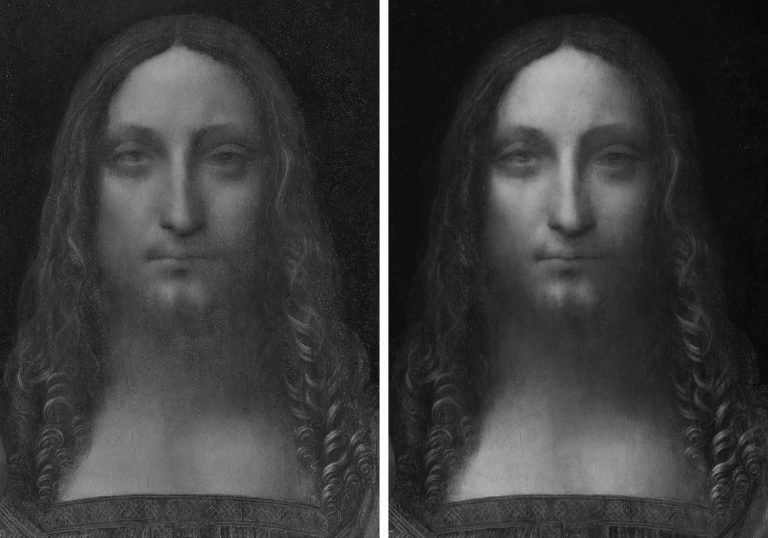

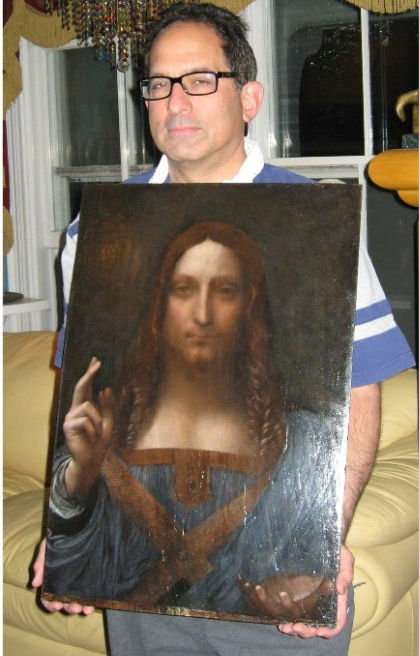

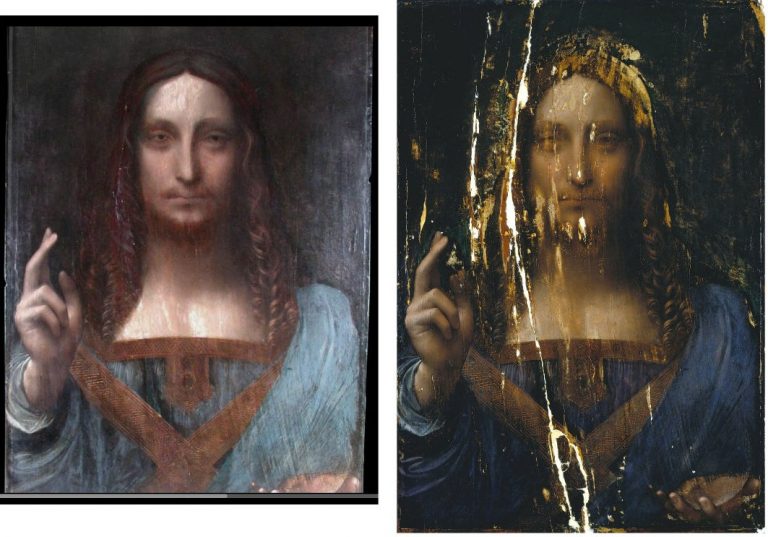

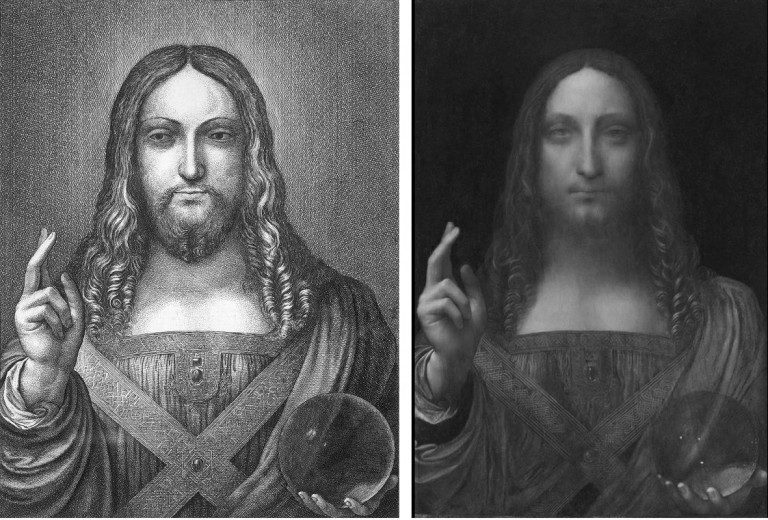

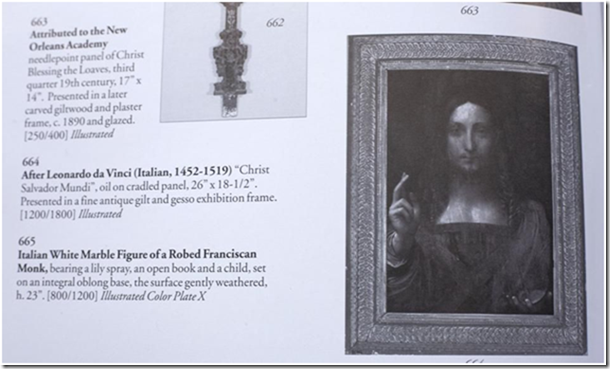

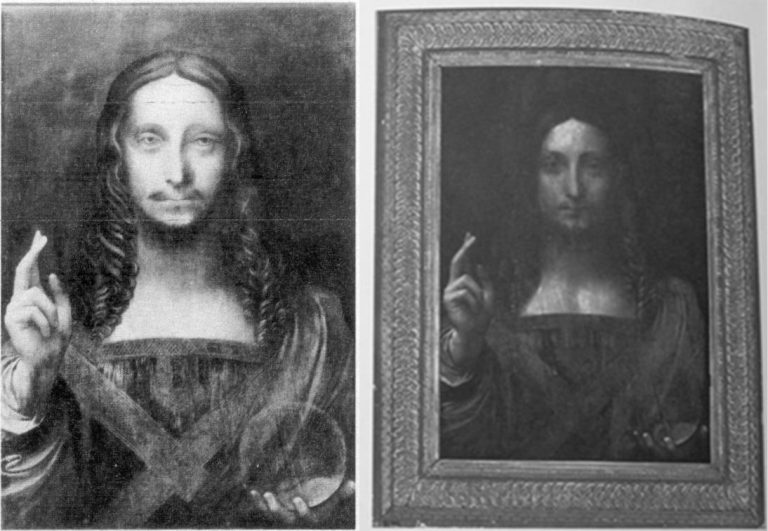

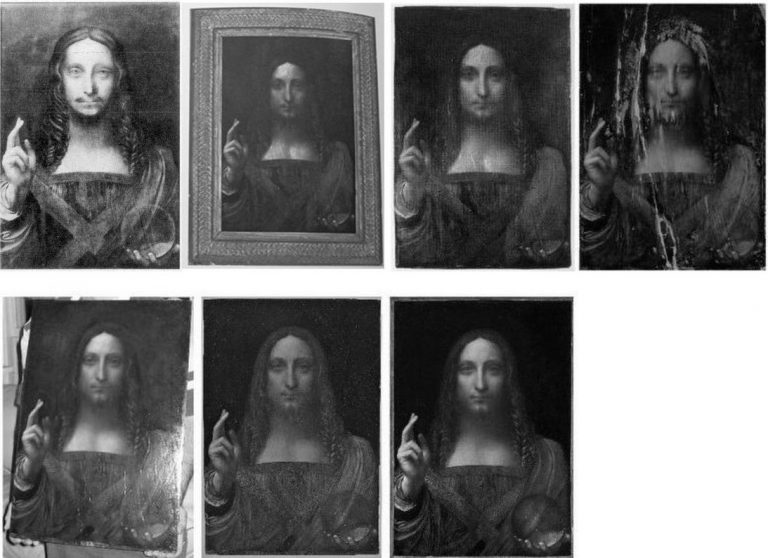

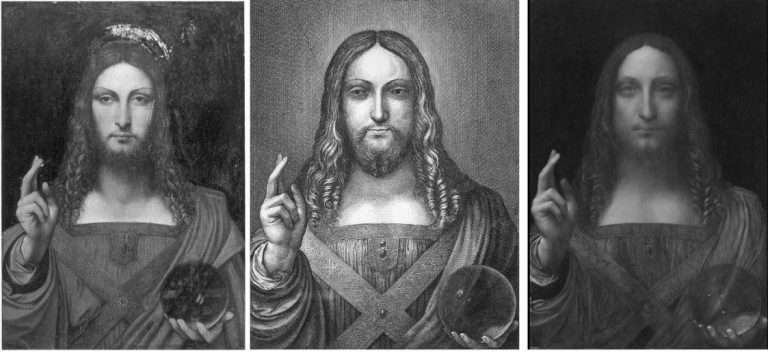

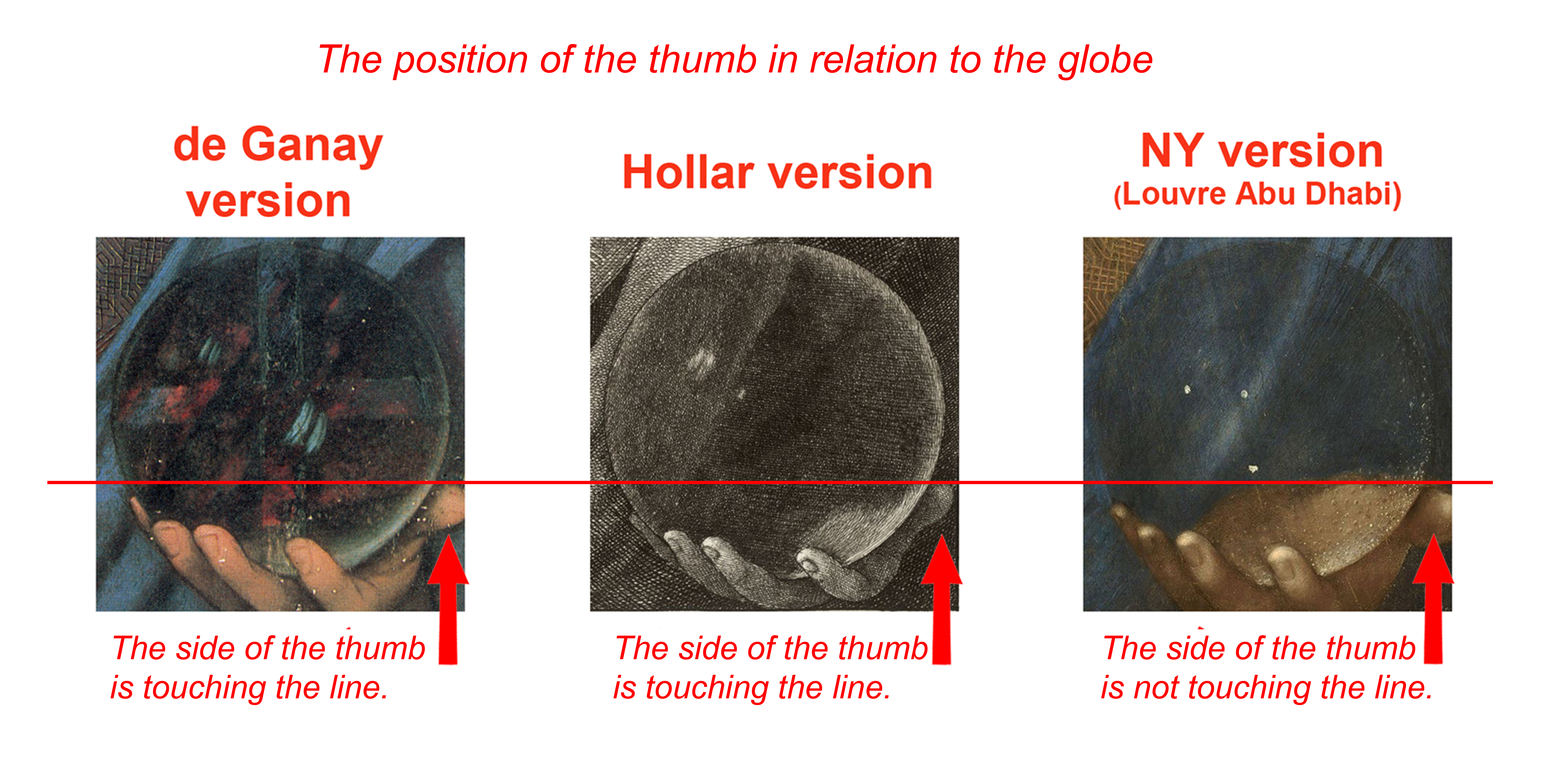

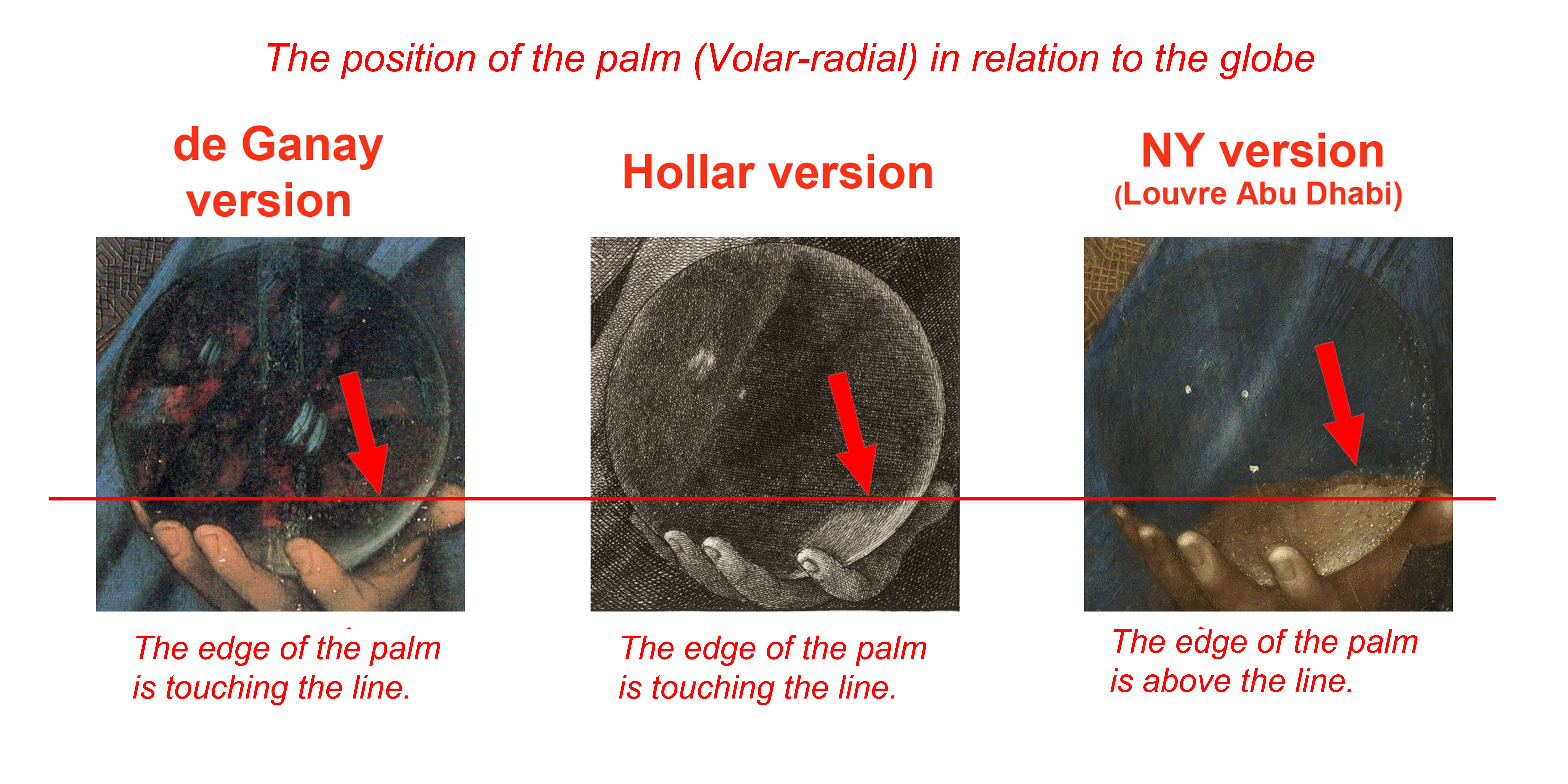

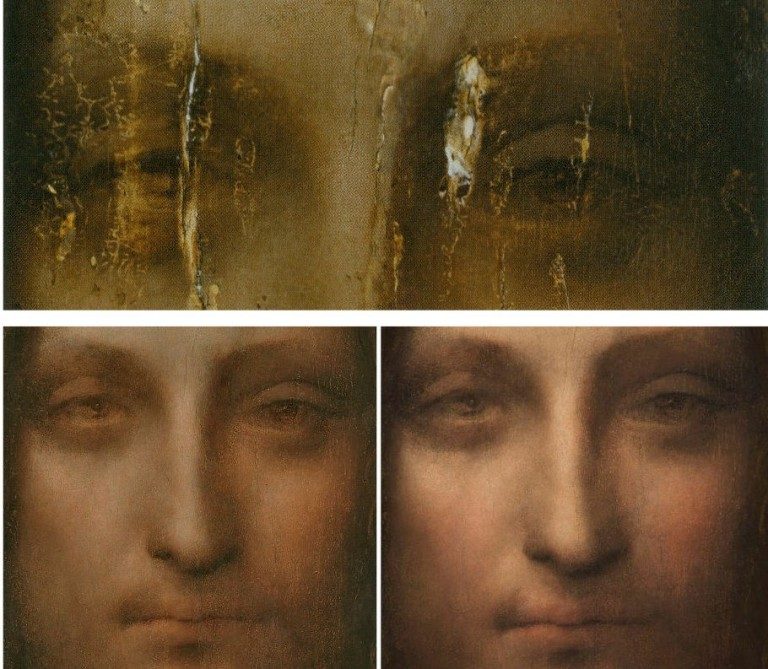

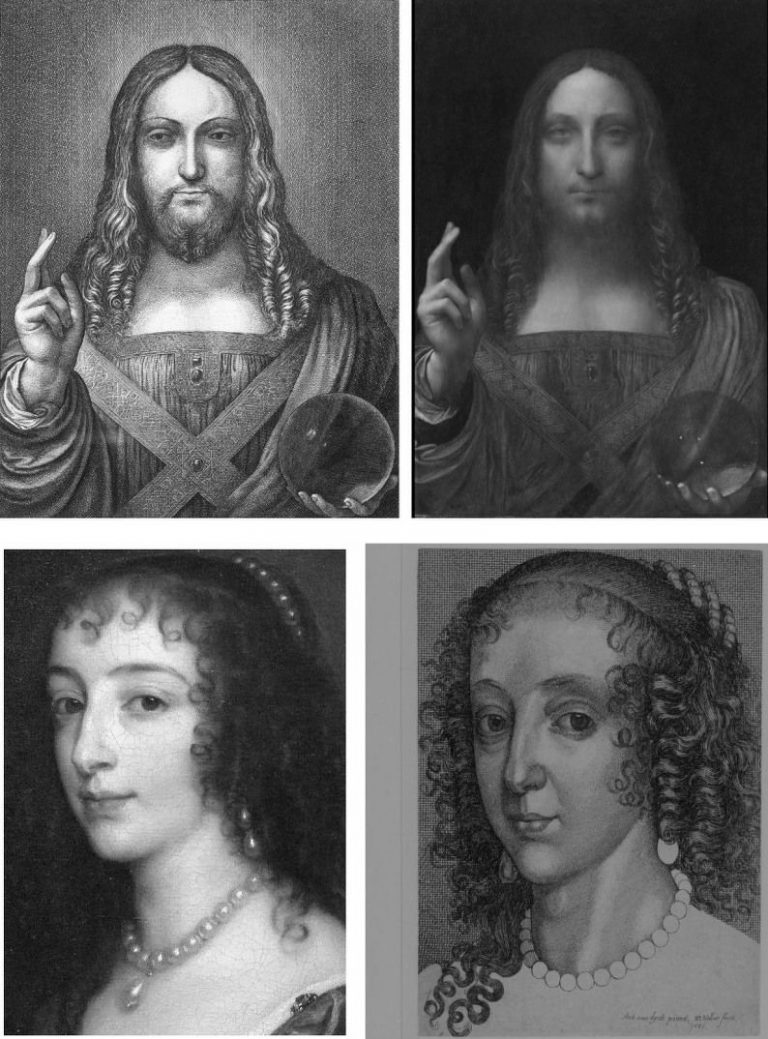

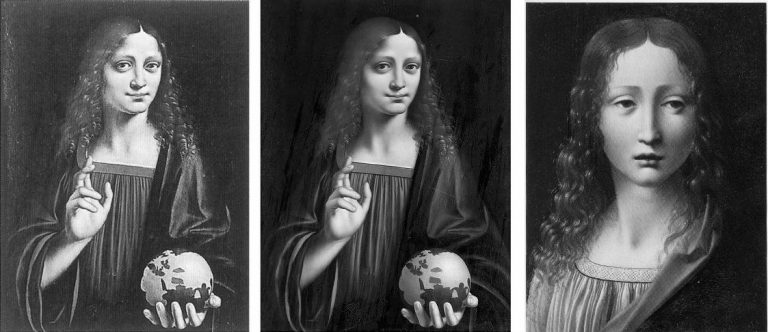

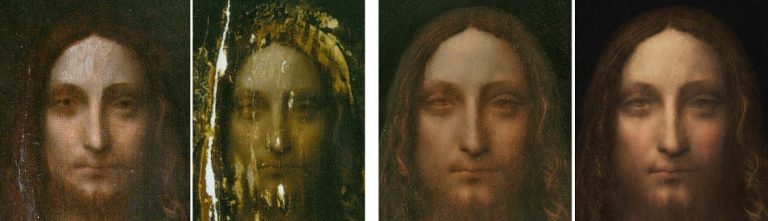

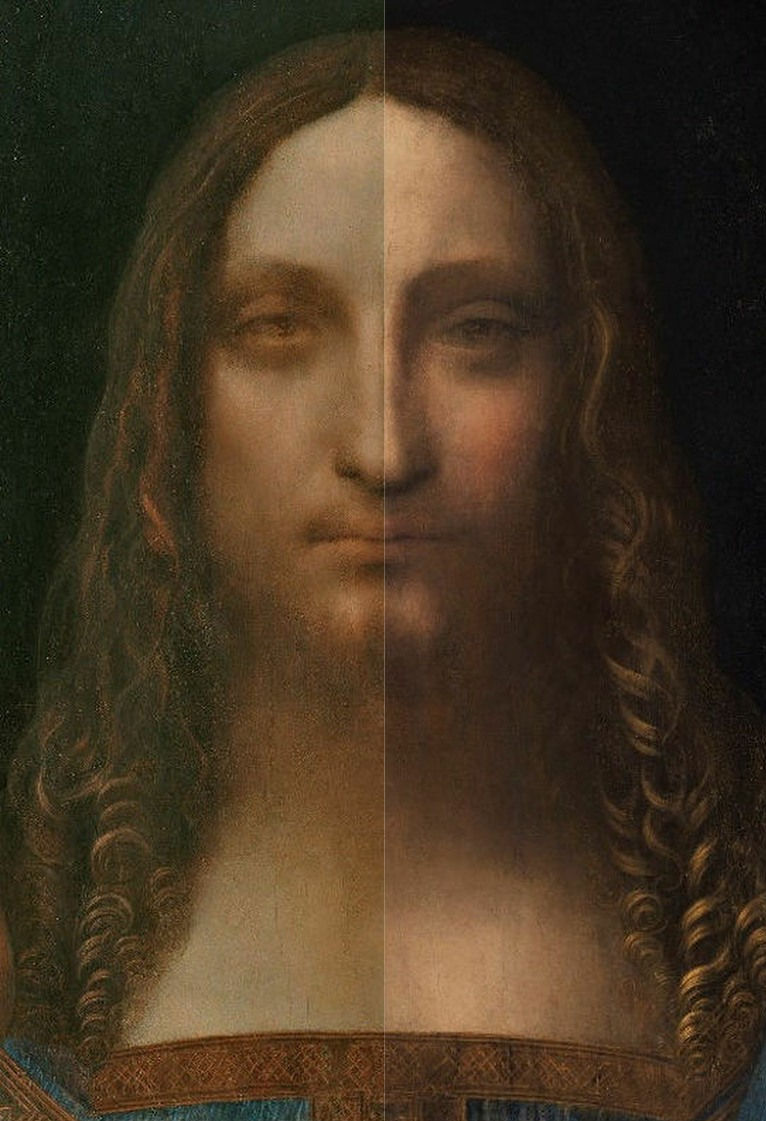

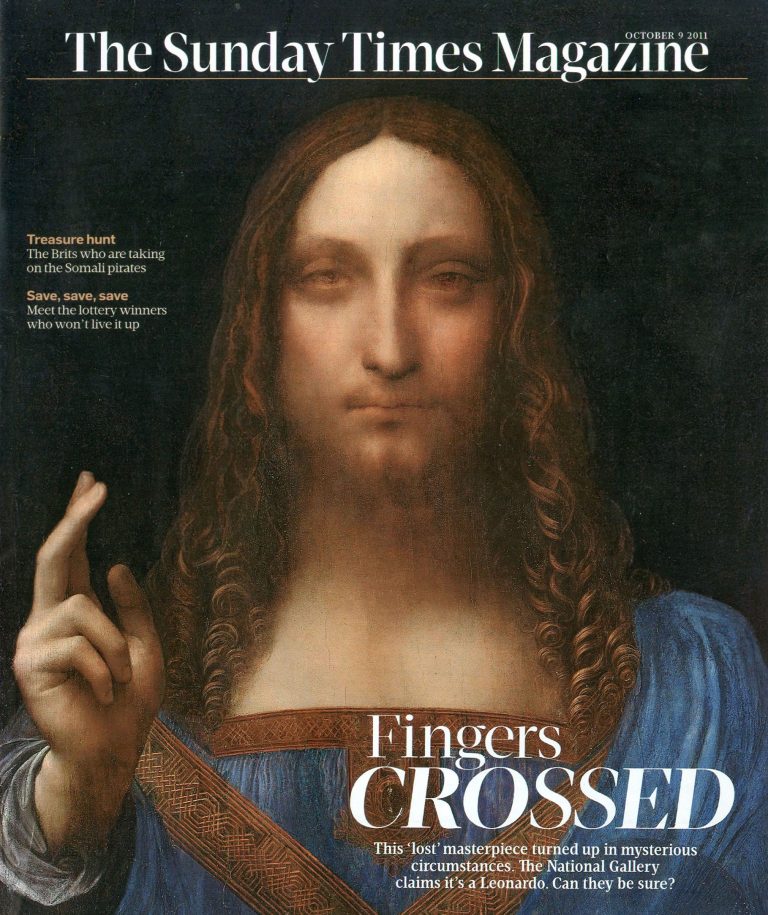

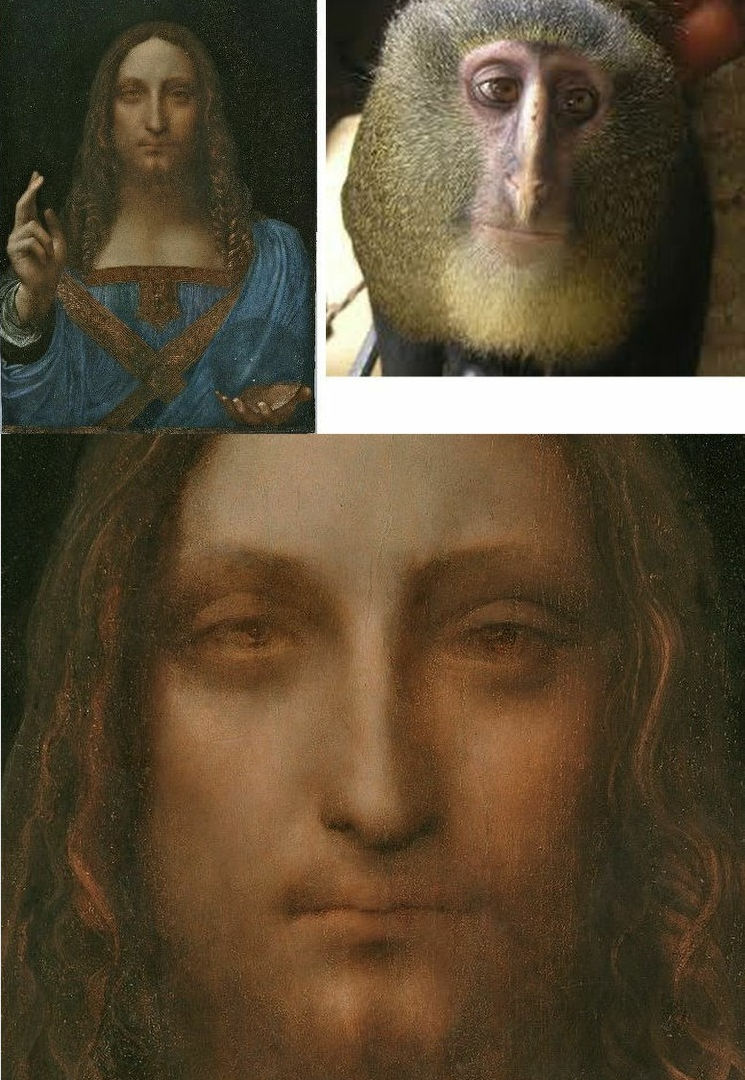

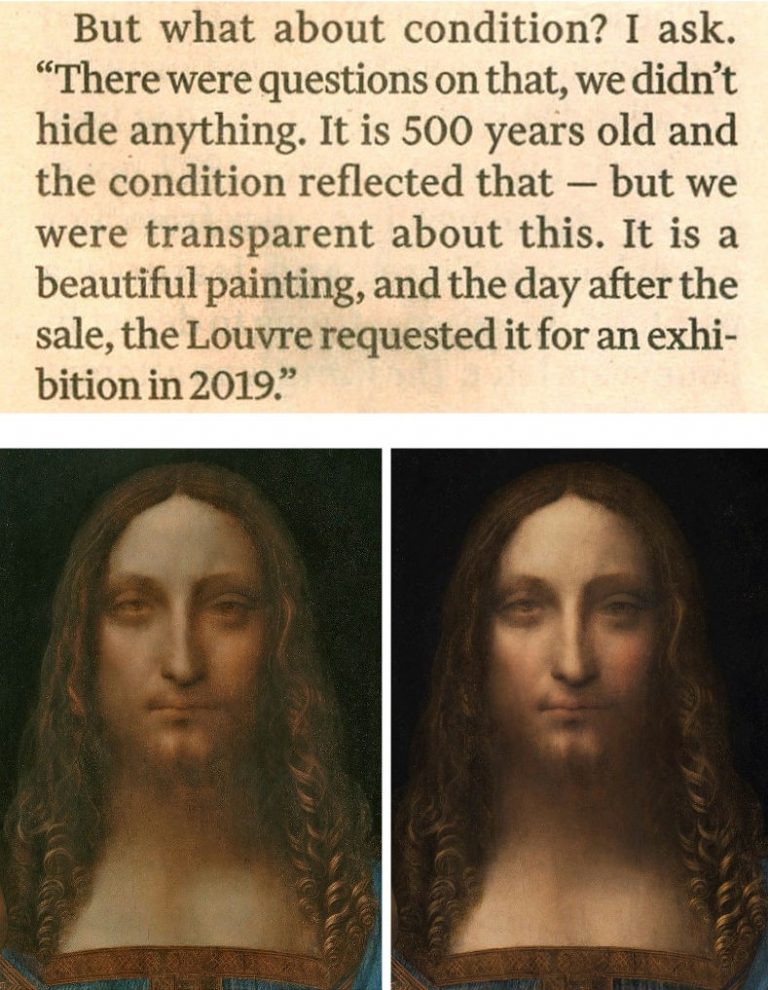

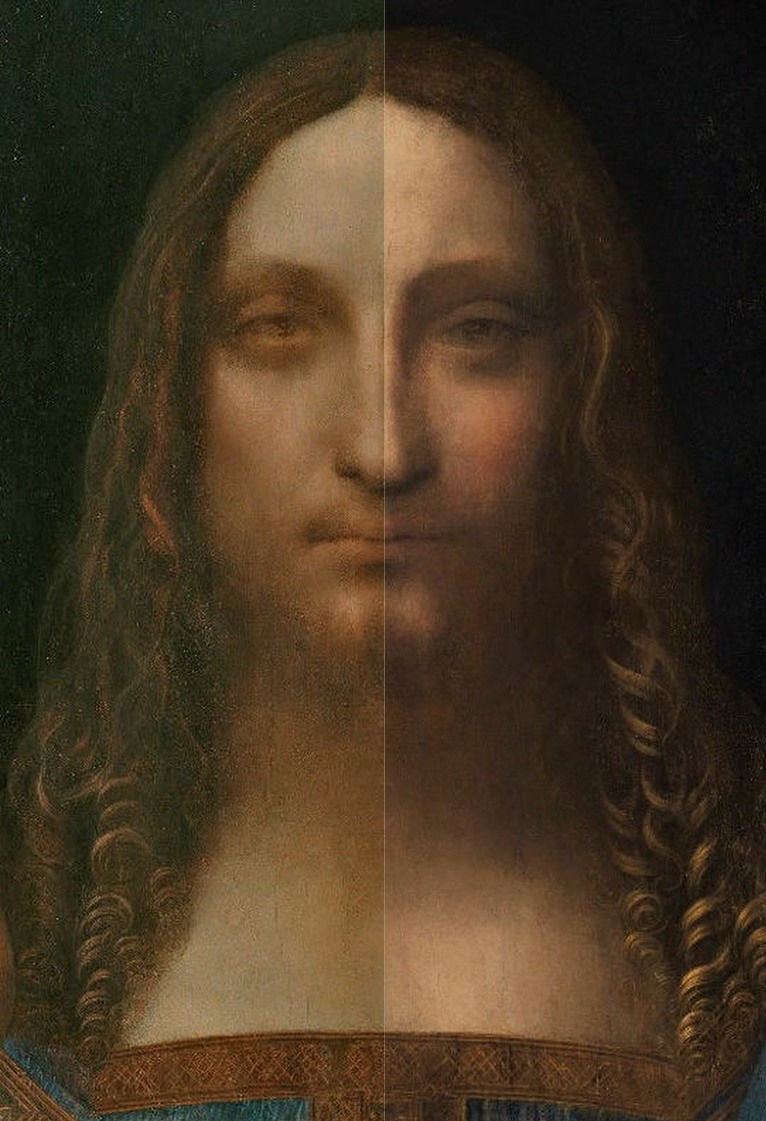

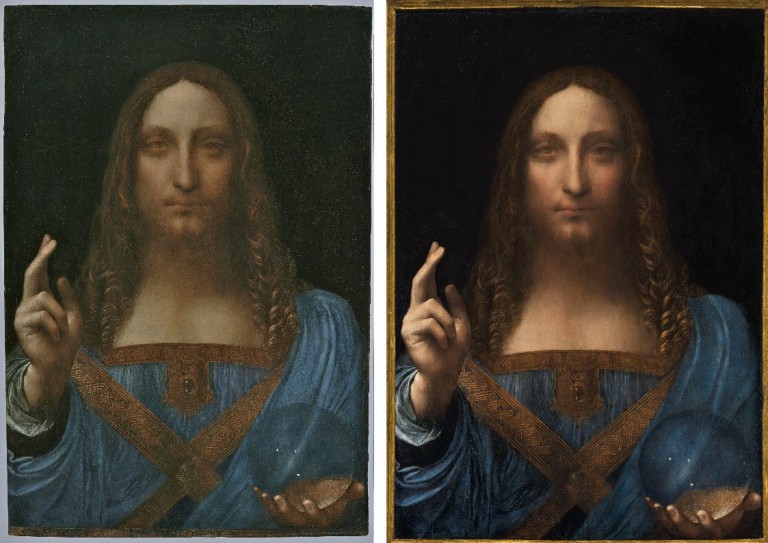

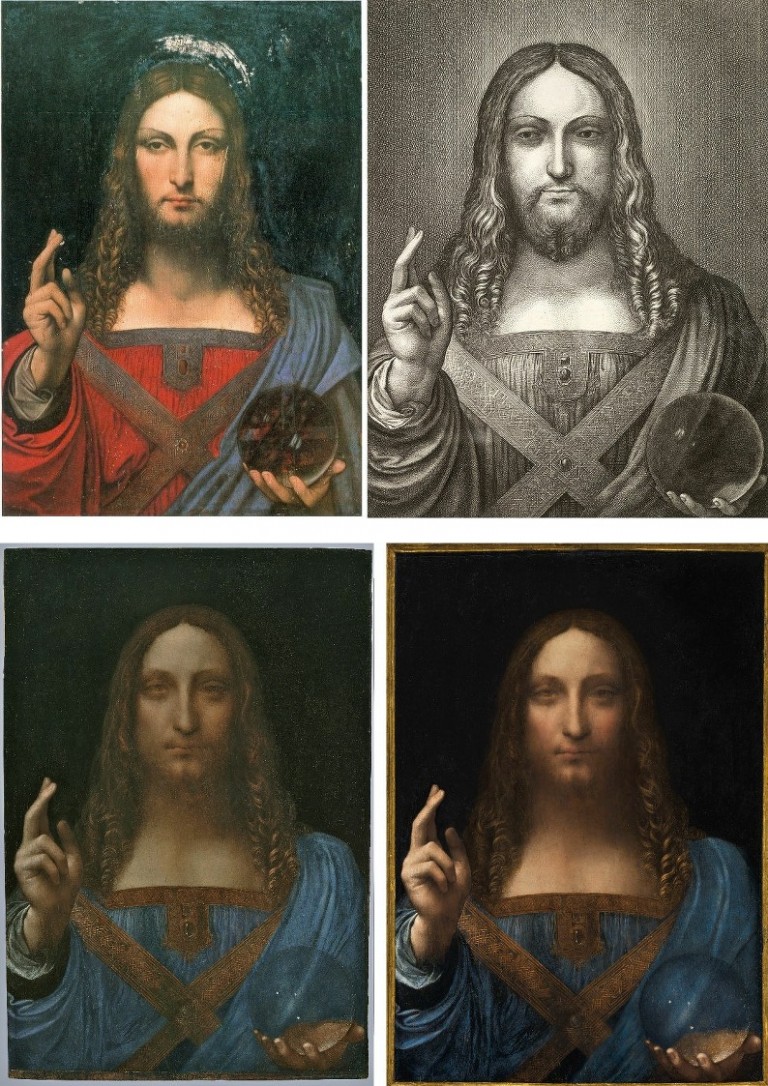

Above, Fig. 1: Left, the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as when taken in 2005 (still sticky from a recent treatment) to the New York studio of the restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini; right, as when taken in 2008 by one of the consortium of owners, Robert Simon, to the National Gallery in London for a covert viewing by a small group of Leonardo specialists.

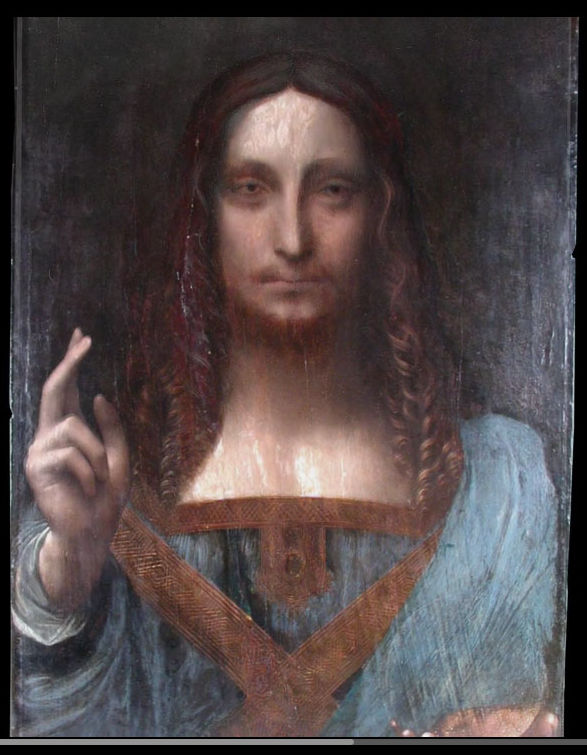

Above, Fig 2: Left, the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi as exhibited in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 exhibition Leonardo da Vinci – Painter at the Court of Milan; right, as seen at the end of Modestini’s restoration programmes in 2017 at Christie’s, New York.

Whenever vicious personal attacks are made by institutions on experts, two things should always be considered: what, precisely, is being said; and, what has been left unsaid. The Louvre’s Trumpian “Fake information” slur on Franck was made by its press officers in response to a report by Dalya Alberge in the Sunday Telegraph (“Paris Louvre ‘will not show’ world’s most expensive painting amid doubts over authenticity”) that the Leonardo painting technique specialist, Jacques Franck, has been told by high level politicians that the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi will not be included in the Paris Louvre’s forthcoming Leonardo exhibition and that Louvre staff “know that the Salvator Mundi is not a Leonardo”.

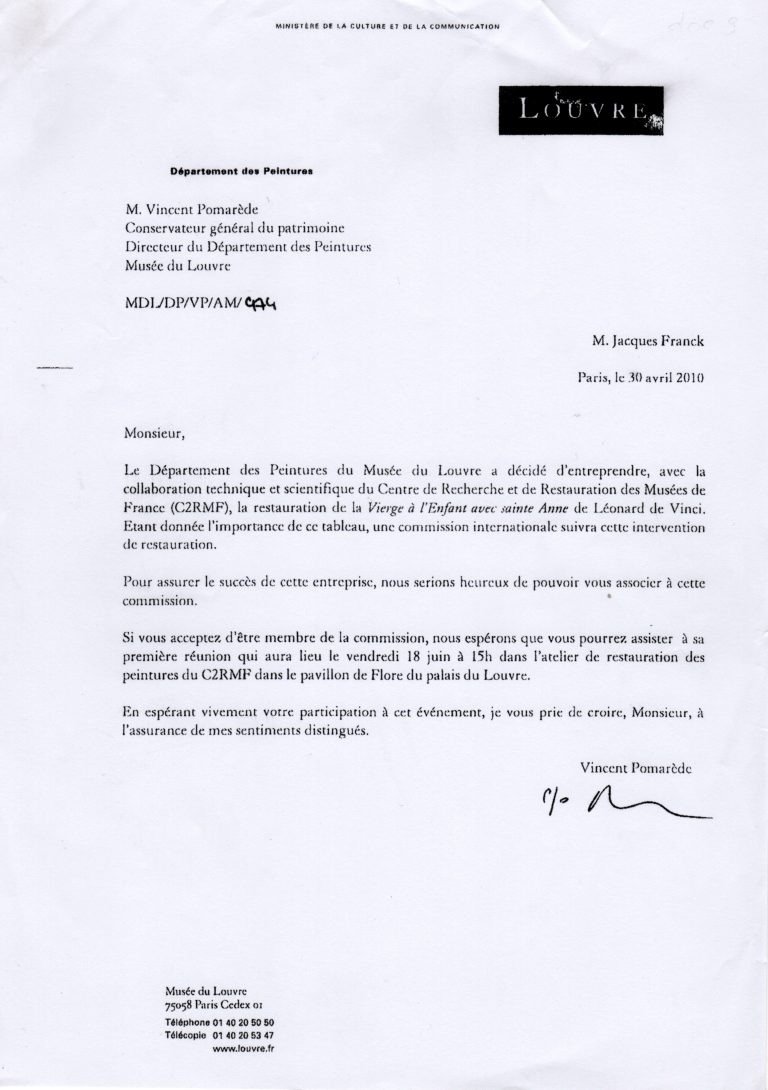

Jacques Franck’s role as advisor to the Louvre’s Leonardo restorations

In attempts to defuse and refute Franck’s (honest) testimony, the museum’s press officers have also scattered red herrings and sown misinformation. To the Mailonline (“Is the world’s most expensive painting a FAKE?”) they claimed that:

“M. Franck was part of the scholars who have been consulted 7 or 8 years ago for the restoration of the Saint Ann.

“He is not currently working on the Leonardo da Vinci exhibition and has never been curator for the Louvre.

“His opinion is his personal opinion, not the one of the Louvre.”

It should go without saying that when called by the Louvre to give technical advice, Franck’s expert views are his own and not those of the museum – why else would he be being called in? No one had claimed that Franck is a Louvre curator. No one had claimed he is working on the Louvre’s forthcoming Leonardo exhibition. So, contrary to appearances, nothing was being refuted. However, on the extent and frequency of his contributions, it would seem that the Louvre’s officials have misinformed the museum’s spokeswomen who have in consequence scattered seriously misleading accounts around the press.

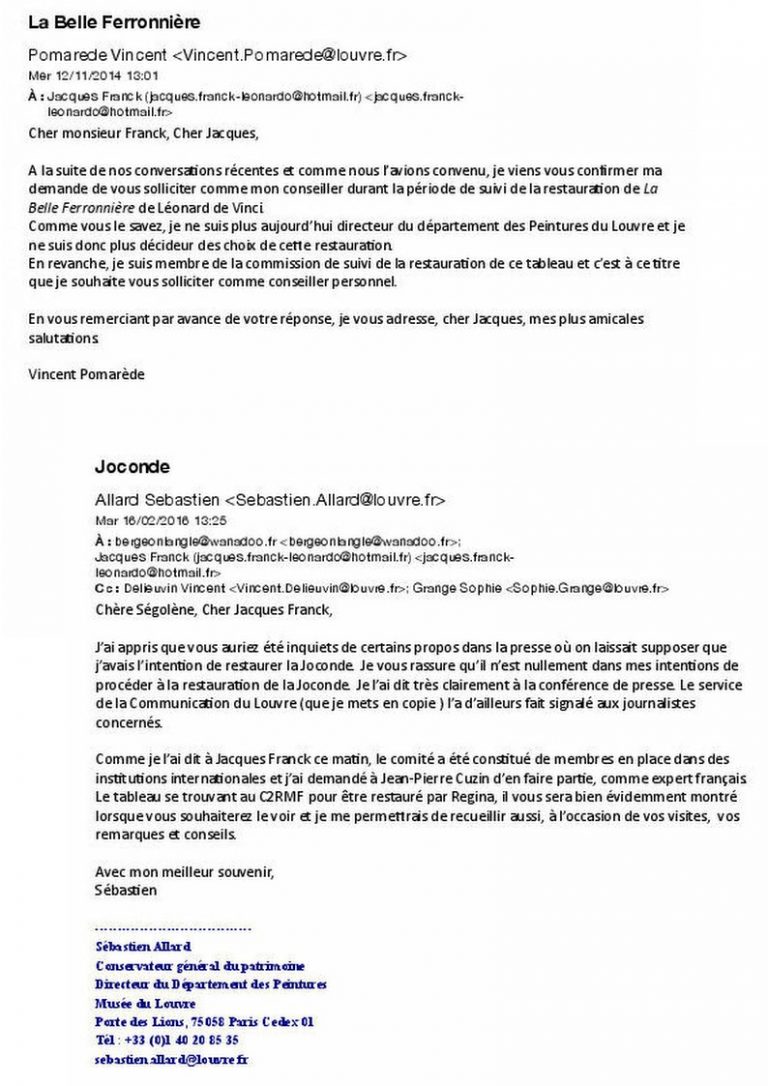

Contrary to their claims to the press, Franck’s association with the Louvre had not ended in 2011-12 after the controversial restoration of Leonardo’s the “Virgin and Child with St Anne” – see Endnote 2 and Figs. 8, 9 and 10. In 2014 his advice was sought by the Louvre when it planned to restore Leonardo’s portrait of the Belle Ferronnière (see Figs. 3 and 4 below). Vincent Pomarède was the Head of Paintings at the time, he had launched the project but before the restoration began he was appointed principal Assistant to the Louvre Museum’s Chairman. He was replaced by Sébastien Allard as Head of Paintings, who became ipso facto, as is the usual custom in the Louvre, the Chair of the scientific advisory committee, while Pomarède retained a prominent role in that committee, partly on account of having promoted the project when Head of Paintings, and also on account of being close to the Louvre’s own Chairman. At this stage he decided that Franck’s contribution was officially that of his special “private adviser” during “all the time that restoration would last”.

Two years later, in 2016, when the cleaning of Leonardo’s Saint John-the-Baptist started, Franck was asked jointly with Ségolène Bergeon Langle, the former head of Conservation in the Louvre (and a legendary figure of the French museums’ restoration), to supply “all remarks and advice” to the then new head of Paintings, Sébastien Allard, on joint visits to see the painting with him in the conservation studio.

The Paris Louvre’s inscrutable position on the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi

The case against Franck, as offered by the Louvre press office on 18 February to the Art Newspaper (“’We want Salvator Mundi’ for Leonardo blockbuster, Louvre says”) rested on two claimed statements of fact: that “the Musée du Louvre has asked for the loan of the Salvator Mundi for its October exhibition and truly wishes to exhibit the artwork”; and, that “the owner has not given his answer yet.”

Those claims are utterly perplexing. As the Art Newspaper noted, the Louvre’s statement suggests that the painting is not, after all, owned by the Louvre Abu Dhabi museum, but by a single individual, widely believed to be Mohammed bin Salman, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia. Can that really be the case? If so, when did the Paris Louvre make a direct request to him to borrow his painting for its big celebratory 2019 Leonardo exhibition? The terse but vague Louvre phrase “has asked” gives no indication of the timing of the request but the Louvre was understood, like the Royal Academy, to have requested such a loan in the immediate aftermath of the Salvator Mundi’s triumphant $450 million sale in November 2017. Was that earlier request renewed, or is it the sole and original request to which the Paris Louvre press office now refers? Either way, the question arises: What grounds has the Crown Prince given to the Paris Louvre museum for withholding his permission to borrow the Salvator Mundi?

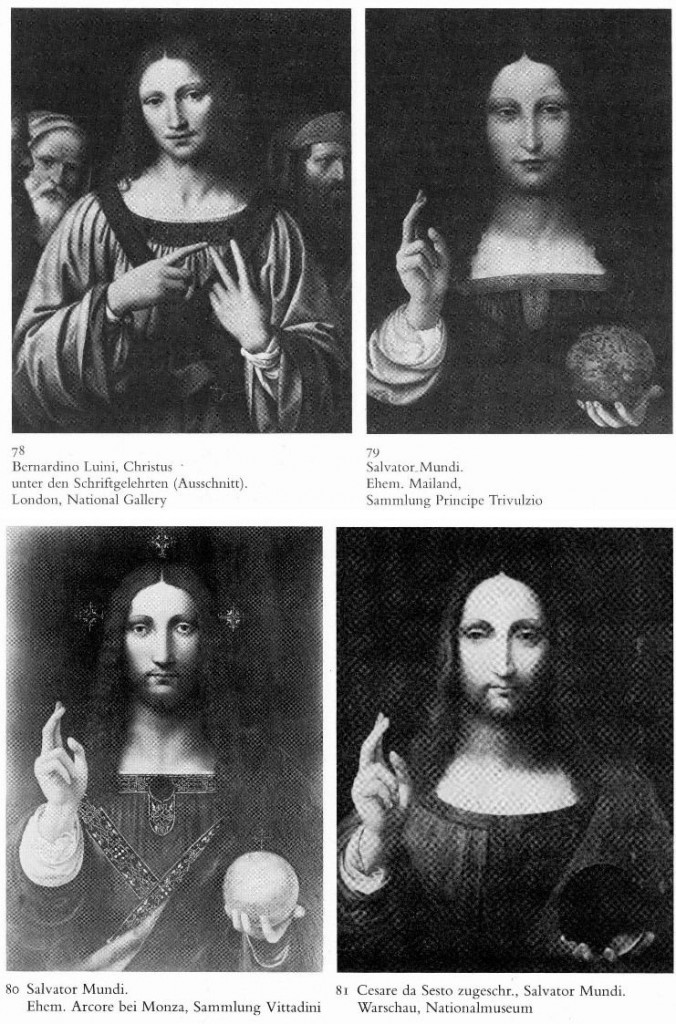

Curatorial Dogs that have not barked

Could it be that the Paris Louvre does still wish to include the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi (it would be immensely politically embarrassing for it to exclude the Abu Dhabi Louvre Museum painting from this year’s long-planned Leonardo extravaganza) but is no longer prepared to describe the painting in its own catalogue and literature as it was described first in the National Gallery exhibition of 2011-12 and later by Christie’s at its 2017 sale – namely, as a Salvator Mundi that “was painted by Leonardo da Vinci [and that] is the single original painting from which the many copies and student versions depend”? If, however, as today’s press officers imply but do not expressly state, the curators and the director of the Louvre really do presently consider the Abu Dhabi painting to be precisely as described in Christie’s’ sale literature, why was no one with curatorial authority at the museum prepared to make that claim publicly and within the official response to Franck’s cited contrary testimony? For that matter, has any Paris Louvre curator ever supported the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo ascription in written scholarly form?

At the same time, is it not also possible that the Salvator Mundi’s individual owner or the Louvre Abu Dhabi museum – whichever presently pertains – will not accede to a loan request on anything less than an assurance from the Paris Louvre that, if included in the major Leonardo anniversary exhibition, it will be categorised as an entirely and unquestionably secure autograph Leonardo prototype painting? If such possibilities are not the case, what exactly has been the cause of the fifteen month-long stand-off between Paris and Abu Dhabi and the cause of the latter’s failure to exhibit the painting – or, even, to disclose its whereabouts? As for the present ownership, after the work was auctioned in November 2017, Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism released a statement saying it had acquired the work for the new Louvre Abu Dhabi museum.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi’s undisclosed whereabouts

The Abu Dhabi museum was scheduled to launch the Salvator Mundi last September but it cancelled its own event with no explanation. It had been widely expected that the Louvre Abu Dhabi would announce plans to exhibit its Salvator Mundi on the 10 February 2018 official visit of the French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe, who toured the Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum on Saadiy island in the Emirati capital, specifically to launch the French-Emirati “Year of Cultural Dialogue” in the company of Shiekh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, CEO of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. But once again, the world’s most expensive painting made a no-show on a no-explanation: the Minister and the CEO both declined to answer any questions about the unexplained decision not to exhibit the painting in Abu Dhabi. (See “A day in the life of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi Annexe’s pricey new Leonardo Salvator Mundi ” and Fig. 5 below.)

Above, Fig. 5: The French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe (centre) poses with Shiekh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (right), CEO of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, during inauguration of BNP paribas Abu Dhabi Global market Branch on February 10, 2018, as photographed by Karim Sahib for AFP and featured in Art Daily’s “The Best Photos of the Day” on February 11, 2018.

Whatever the problem was on those two earlier occasions, it is clear on the Paris Louvre’s press office’s latest statements that that blockage remains in place – just as the whereabouts of the painting itself remain undisclosed fifteen months after the painting was sold for a world record price. The essential question therefore remains outstanding: Why will the Abu Dhabi Louvre museum neither exhibit its own Salvator Mundi painting nor agree to lend it to the Paris Mother-Museum? In truth, the issue here is not one of fake information by critics of the attribution, but of a bizarre combined refusal by two museums and/or a prince to explain their own repeatedly aborted-actions and prolonged failures to reach an agreement or disclose information.

If Franck’s sources are correct in claiming that the Paris Louvre Museum has lost confidence in the Salvator Mundi as an autograph Leonardo, then an explanation for the present perplexing state of affairs offers itself: there exists today a perfect state of mutual paralysis as the Louvre wishes to avoid an international, inter-governmental embarrassment by including the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi painting but not as an accredited autograph work; while the owner(s) will gladly lend it but not as an attributed work of Leonardo’s studio.

The present manifest disinclination of the Louvre’s own officers and curators to make any personal declaration of confidence in this Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo attribution is encountered also among almost all of the painting’s original dozen or so Christie’s-cited supporters. If, as the Paris Louvre’s press officers claim, the Abu Dhabi painting really does retain the confidence of both the museum’s own curatorial staff and the dozen or so scholars identified as supporters by Christie’s ahead of the sale, as an autograph work of Leonardo, they would all seem to share a funny way of not-showing it. As things stand, and as we were reported as saying in the 17 February Sunday Telegraph, “What we now have is effectively an un-dead painting – no one believes in it; no one will say where it is; no one can lay it to rest.”

Endnote 1:

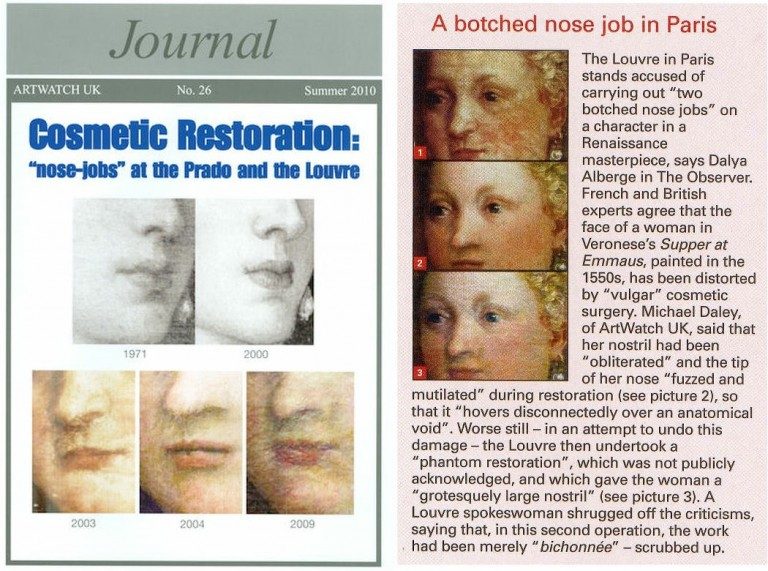

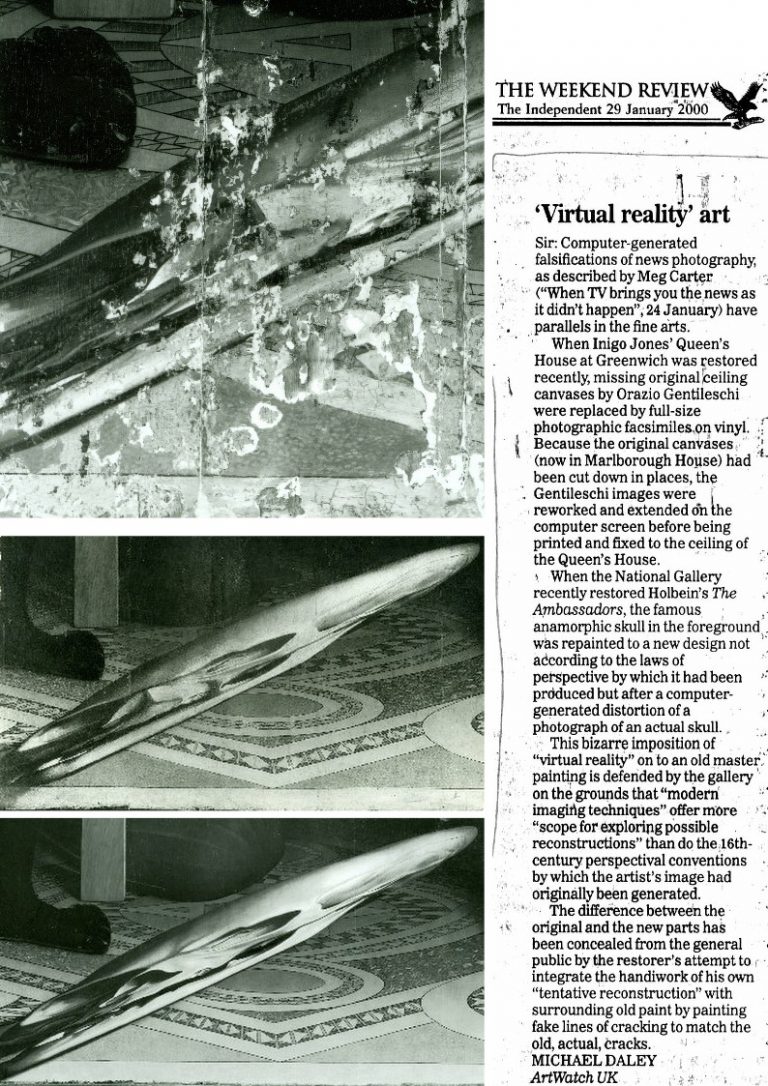

Experience shows that on matters of art restoration Louvre press office claims are sometimes best taken with a pinch of salt. In 2010 we carried a report of a covert second repainting at the Louvre of a face in a Veronese painting – see “A spectacular restoration own-goal: undoing, re-doing and (on the quiet) re-re-doing a Veronese masterpiece at the Louvre Museum.”

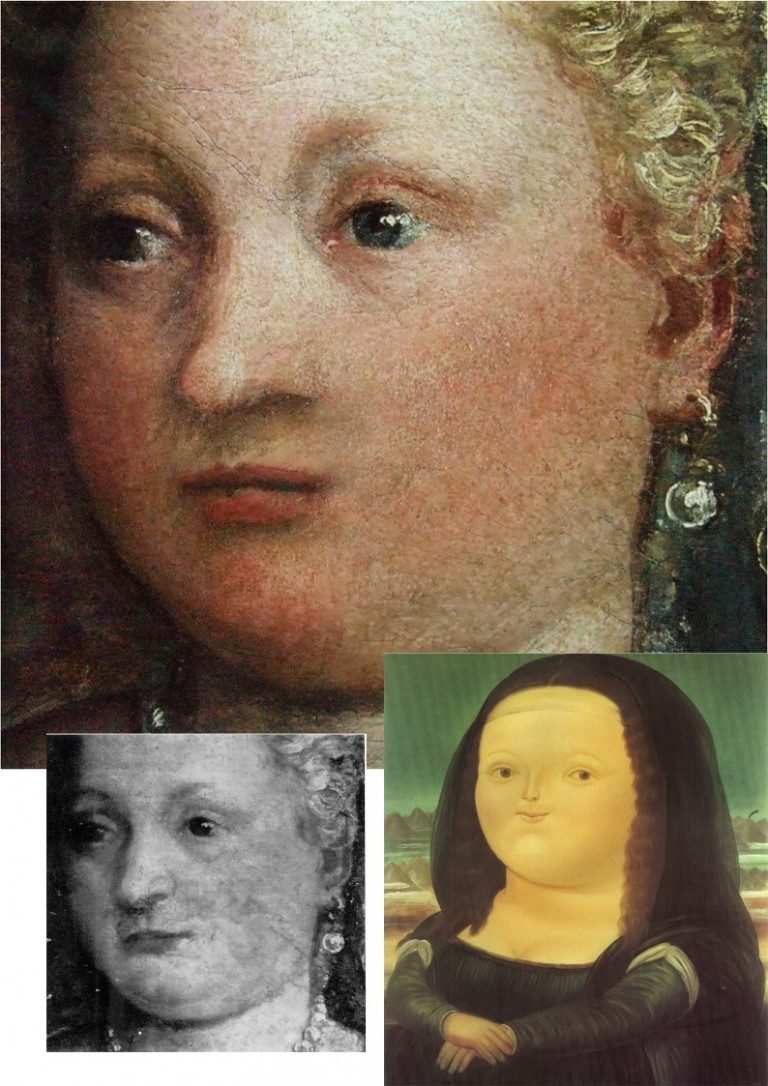

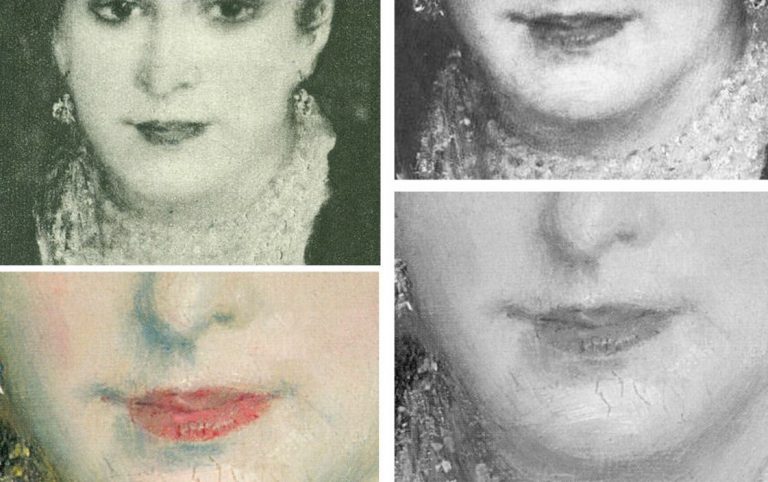

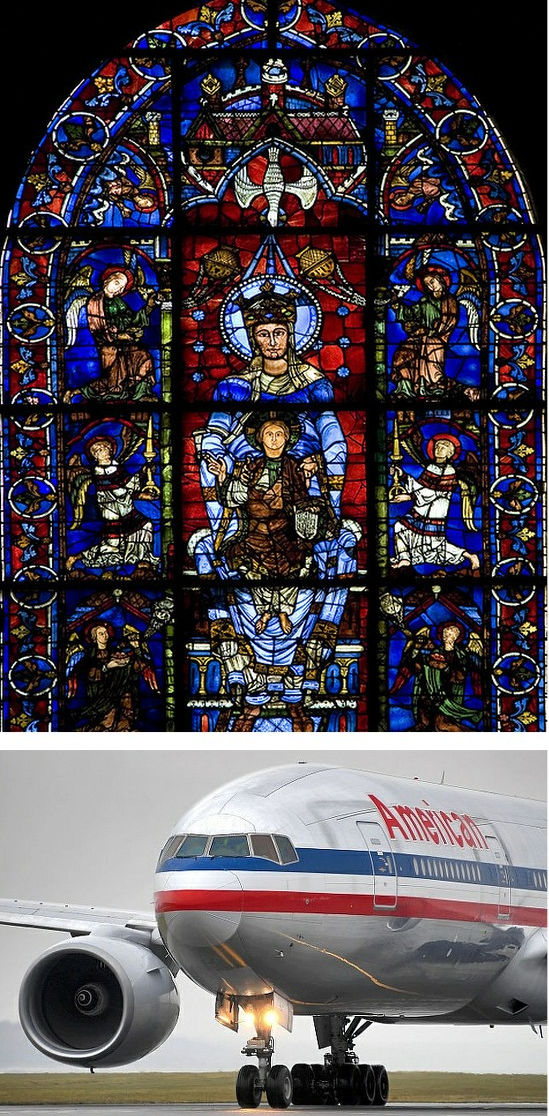

Above, Figs. 6 and 7: However good their intentions, however avowedly “ethical” their professional codes, restorers, like forgers (who are often themselves restorers or ex-restorers), cannot avoid leaving personal imprints and those of their cultural milieus in their repainting. The more ambitious the aspirant, the more deficiencies of artistic reading and anatomical understanding can be imposed on mute works of art. The Louvre Veronese restorer above seemed in thrall to the pneumatic forms and miniaturised features of Botero. That such eccentric aesthetic predilections should ever have been institutionally authorised would augur badly for the Mona Lisa herself in a Louvre Museum today where the curators are bingeing on radical restorations as they play catch-up with the technological adventurism long-encountered in British and American museums.

In June 2010 when the arts journalist Dalya Alberge asked for explanations of this second covert and unrecorded repainting of the Veronese face, the Louvre press officer stated that the restoration had consisted of the painting being merely “scrubbed up” (“bichonnée” – a term normally used for very light interventions such as dusting or retouching a minor scratch unnoticed in the museum etc). That the museum’s official description bore little connection with the pictorial truth of the situation can be seen at glance above at Figs. 6 and 7 and here:

“Louvre masterpiece by Veronese ‘mutilated’ by botched nose jobs”.

Endnote 2:

On the Paris Louvre’s controversial restoration of Leonardo’s the “Virgin and Child with St Anne”, see:

“The Louvre Leonardo Restoration Committee Resignations”;

“What Price a Smile? The Louvre Leonardo Mouths that are Now at Risk”;

“Another Restored Leonardo, Another Sponsored Celebration – Ferragamo at the Louvre…”;

“Rocking the Louvre: the Bergeon Langle Disclosures on a Leonardo da Vinci restoration”.

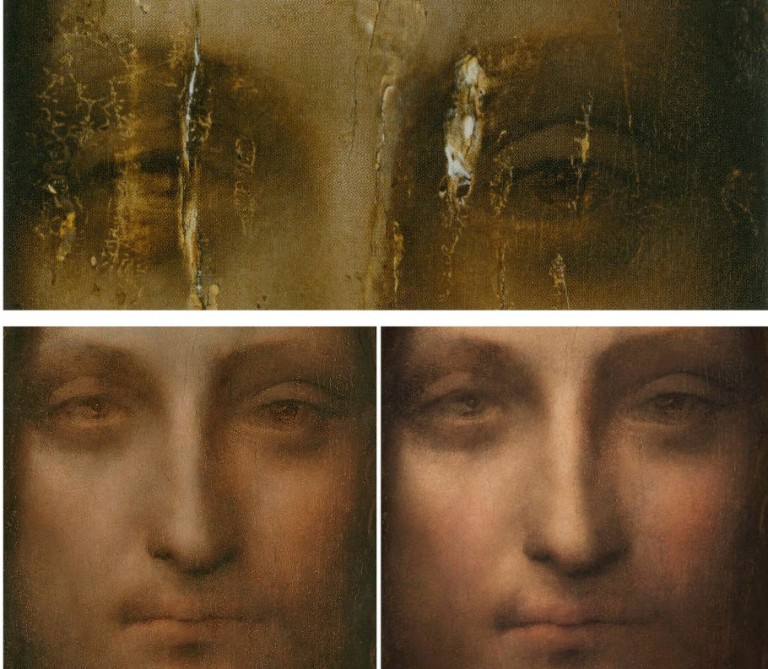

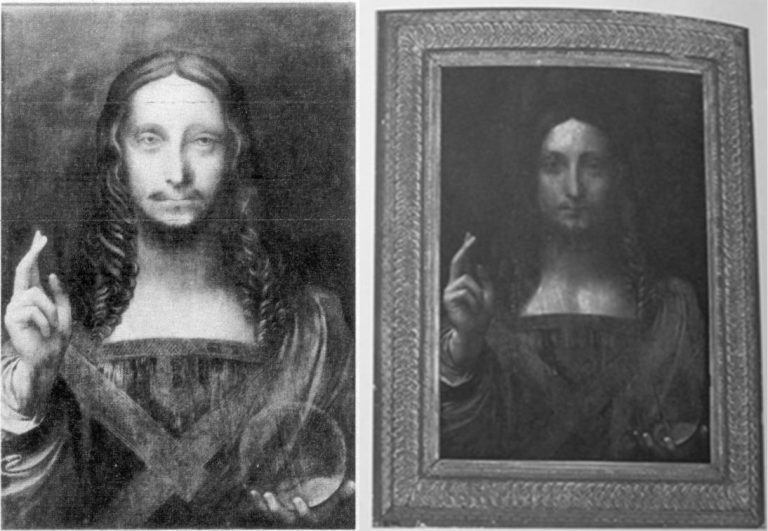

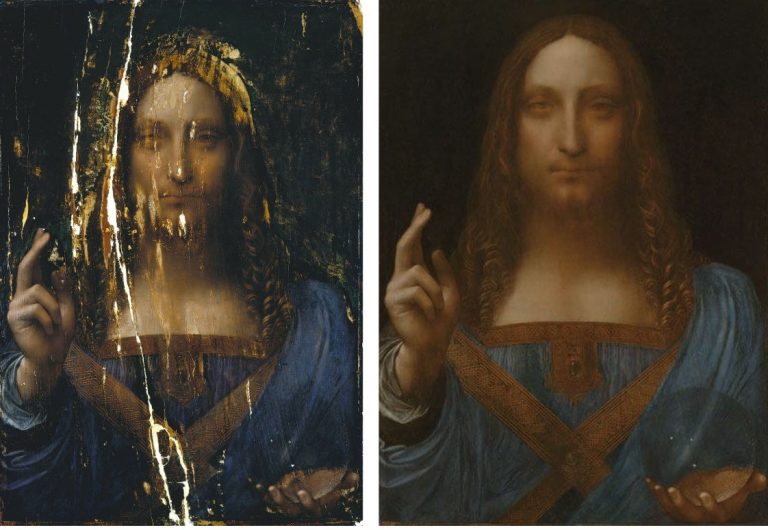

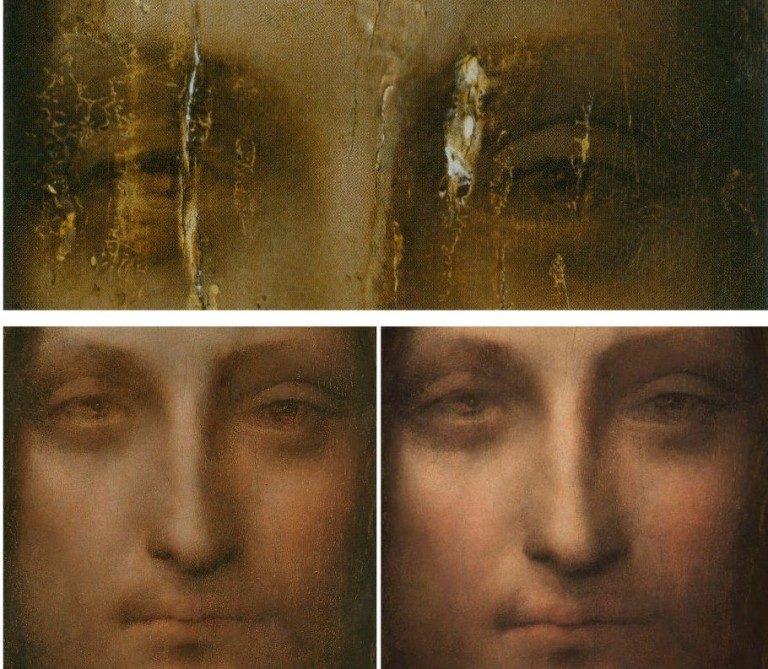

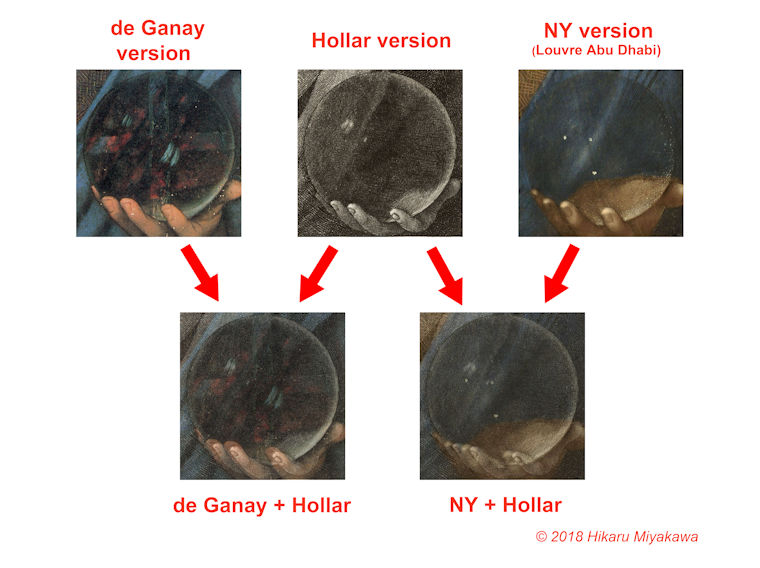

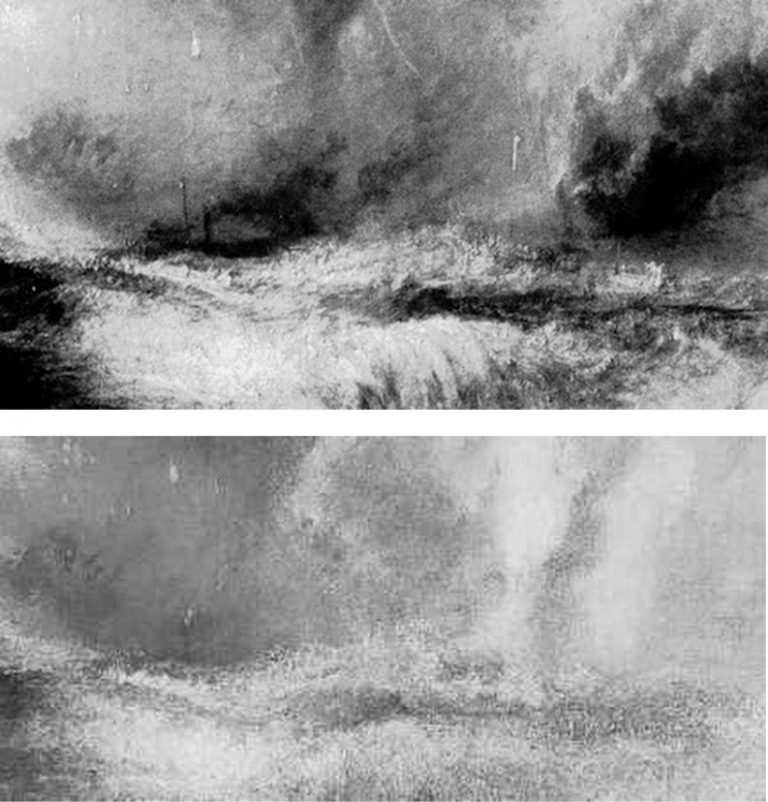

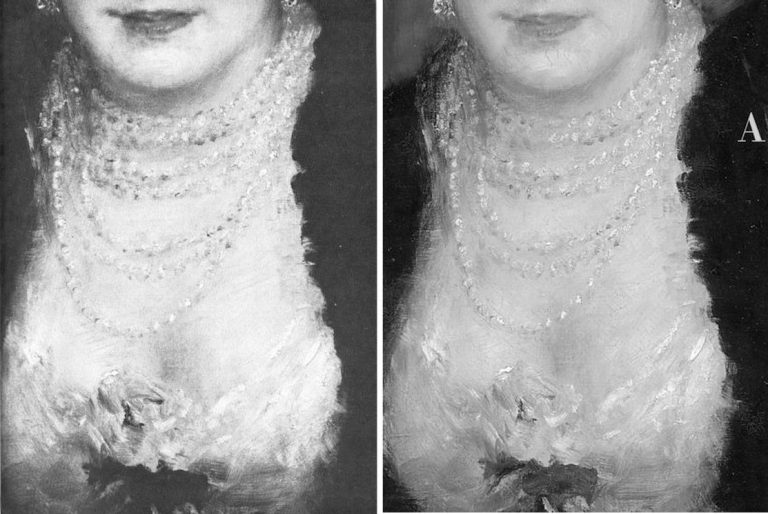

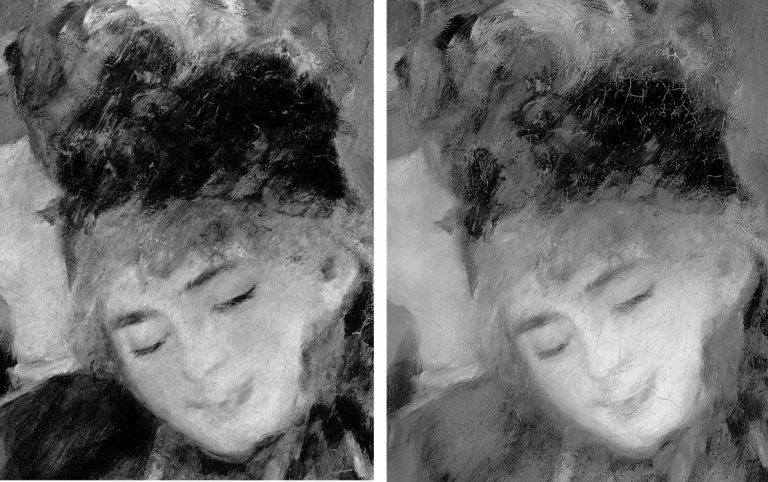

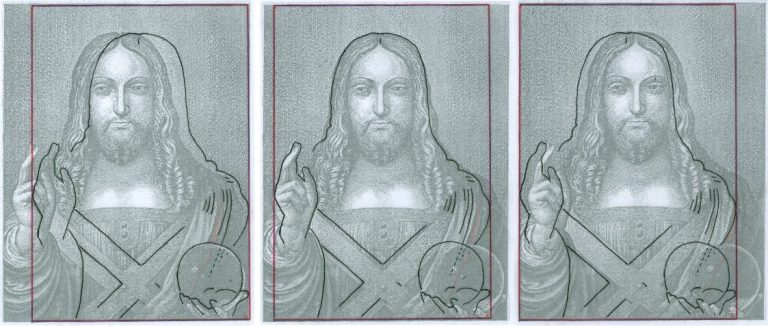

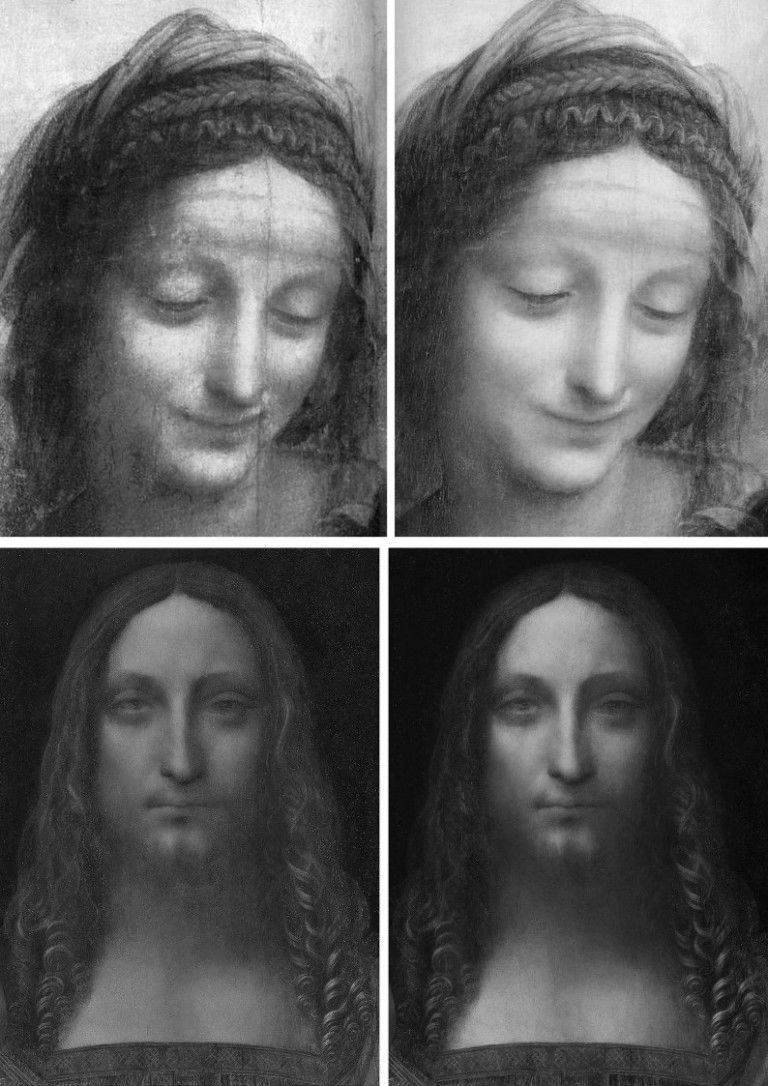

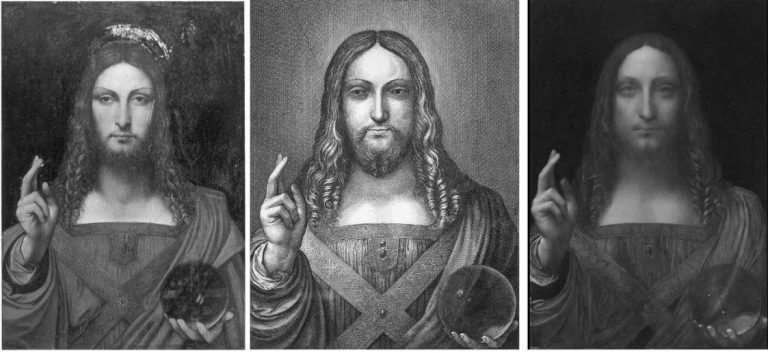

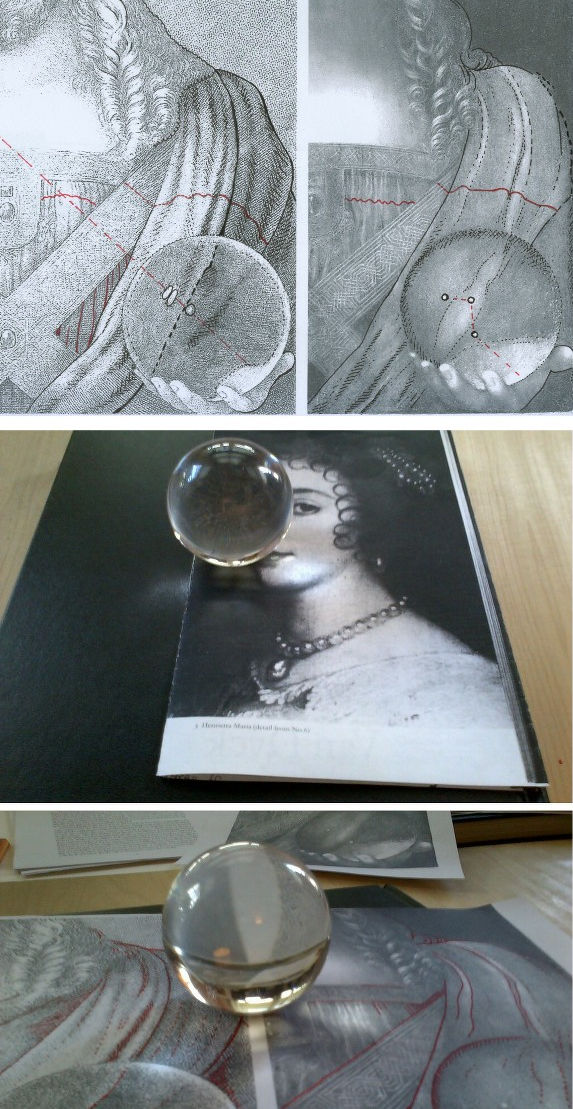

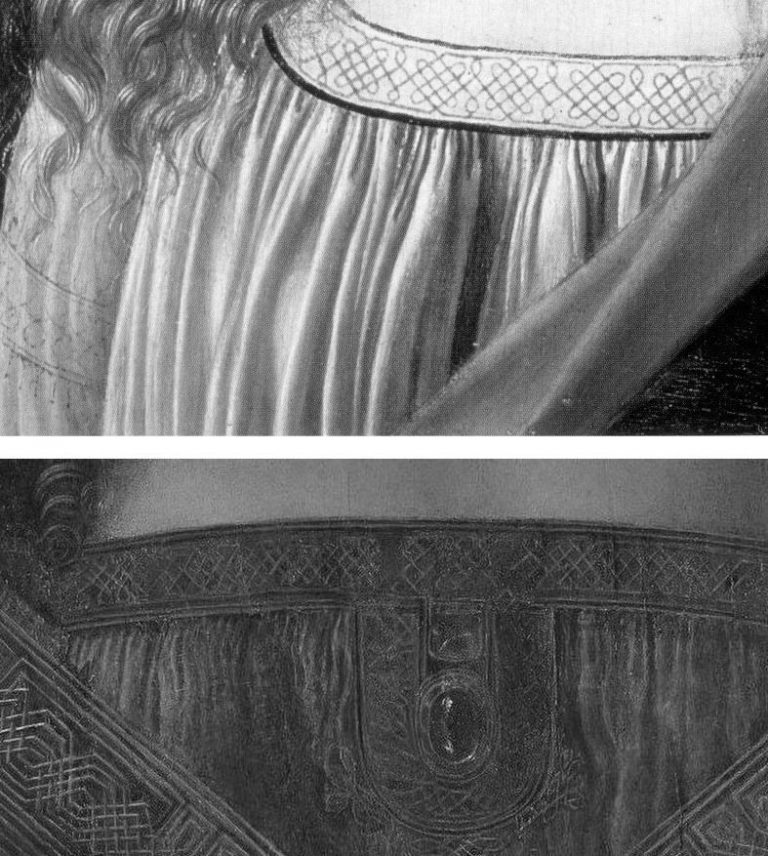

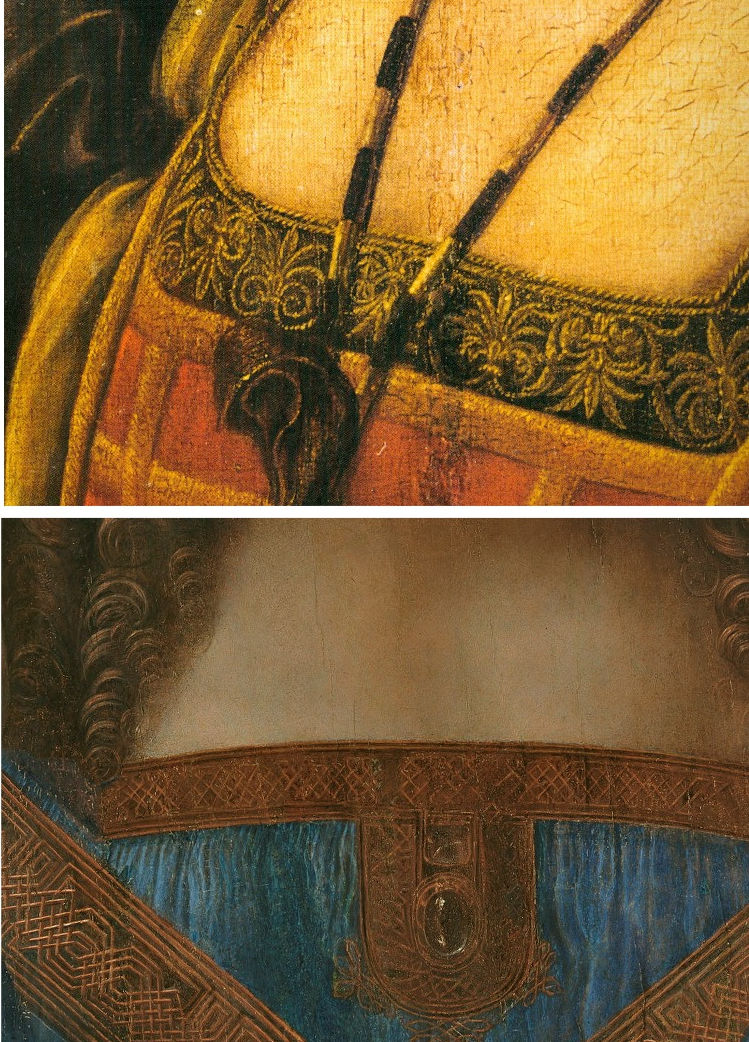

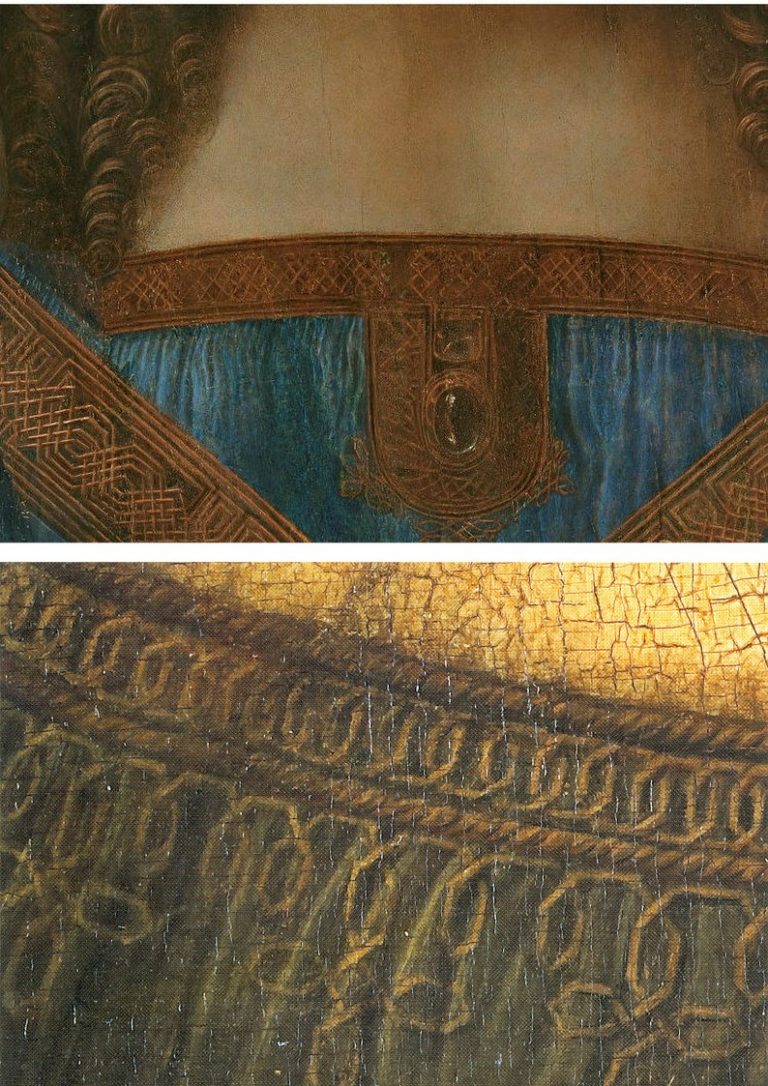

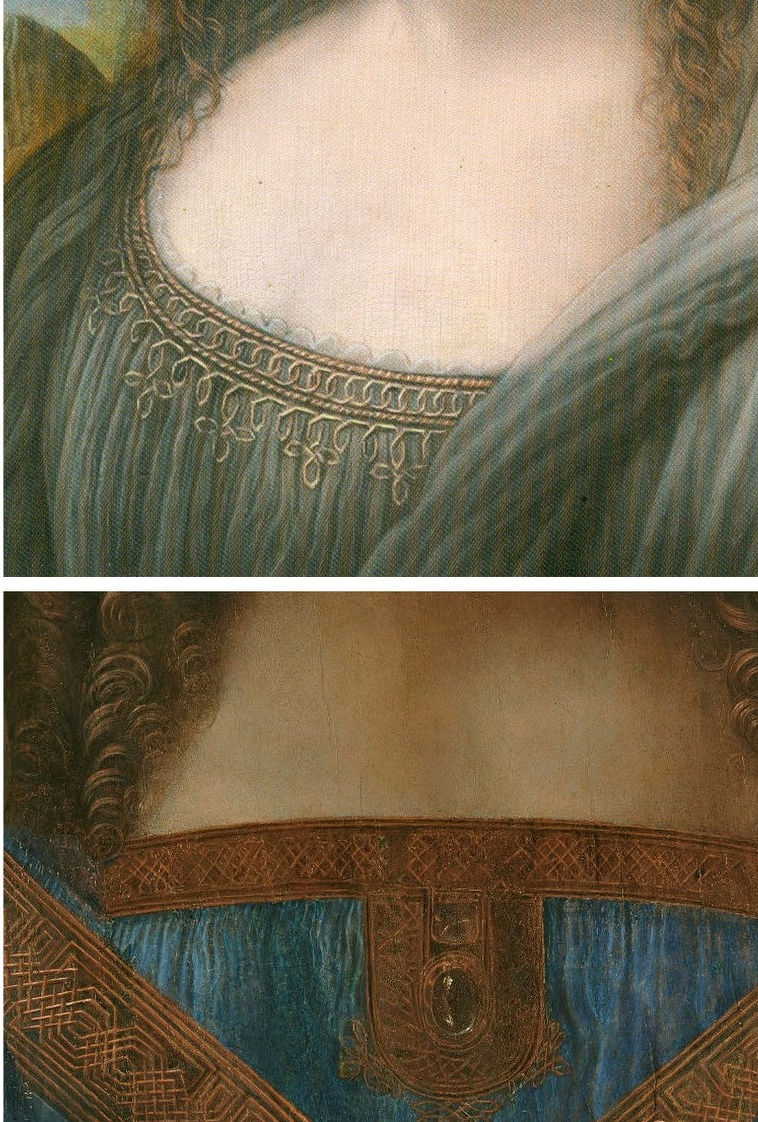

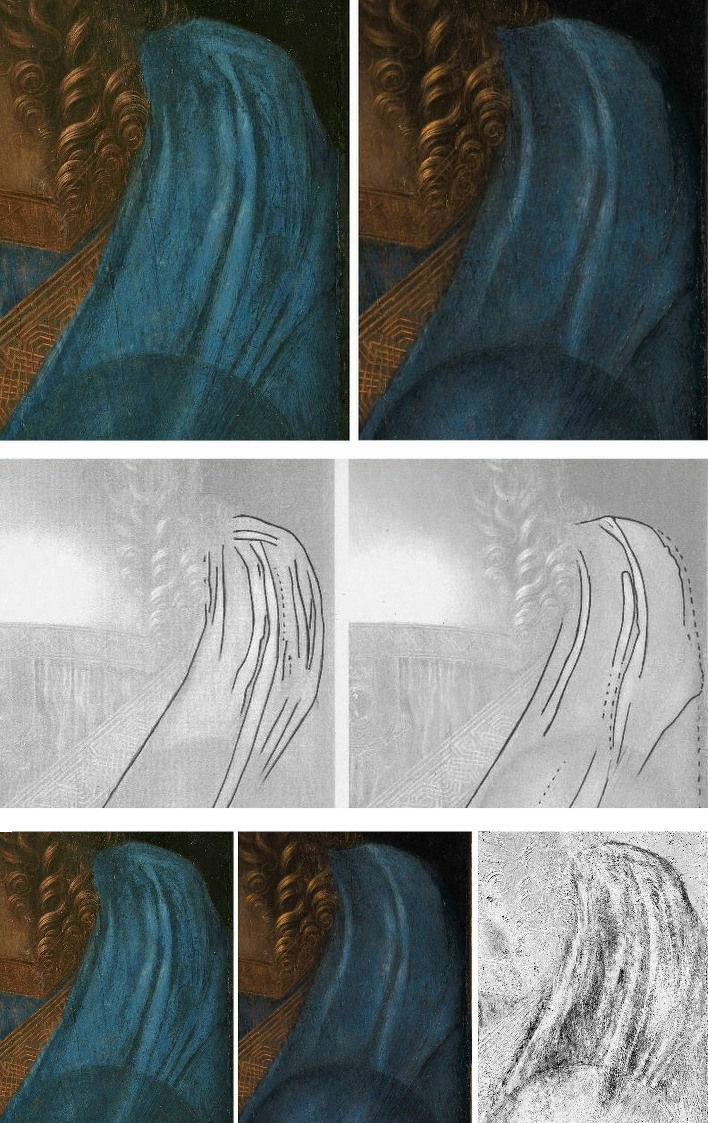

Above, Figs. 8, 9 and 10: Top and centre, a detail of the Louvre’s “Virgin and Child with St Anne”, before restoration, left; after restoration, right. Above a detail of the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi, as exhibited at the National Gallery in 2011, left, as sold at Christie’s in 2017.

In the above three sequences we can see the principal twin consequences of “restoration” procedures: with a bona fide Leonardo masterpiece (top and centre) values are diminished and degraded. With a not-Leonardo, above, we see attempts to move a painting further towards a modern conception of what bona fide Leonardos look like. The outcomes – degradation or falsification – can occur on the same work. There are more restorers than ever before in history and they are ceaselessly working and re-working a finite pool of old master paintings which resemble themselves less and less. Pontormos and Giorgiones alike increasing resemble coloured drawings.

Michael Daley, Director, 22 February 2019

The Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Not “Pear-shaped” – Dead in the water

The attribution of the world’s most expensive painting – the $450 million Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi – has collapsed under the combined weights of two scholars’ findings and the picture’s own artistic and art historical implausibility. Having disappeared immediately after its world-record sale at Christie’s, New York, in November 2017, this Leonardo-in-hiding is also mired in allegations of a joint involvement in the sale by presidents Trump and Putin. The toxic proximity of those two heads of state is a matter of intense national political concern in the United States where high-level official investigations are underway – as are a number of legal actions concerning auction house buyer/seller conflicts of interest. As those disputes play out, we consider the workings of today’s art historical and art market interface.

THE ART CRITICAL CONTEXT

In the 1990s we claimed common failures of connoisseurship in bad restorations and misattributions but thought the latter less serious because potentially correctable. That distinction is dissolving as increasingly many upgrading attributions are made on the back of “improving” restoration transformations. Generally speaking, connoisseurship shortcomings are evident in failures to detect outright fake old masters and in too-ready acceptances of elevated restoration-enhanced school works. Purpose-made fakes are closely related in their fabrications to the painted “recoveries” of supposedly original authentic appearances on stripped-down pictures. (See “A Restorer’s Aim – The fine line between retouching and forgery”.) The fakery of artificially distressed new paint and false painted craquelure is common to routine restorations; to restoration-assisted upgrades; and, to outright fakes. On the additional, extraordinary rise of the “painted-in” insinuation of computer-generated virtual reality into old master pictures, see “The New Relativisms and the Death of ‘Authenticity’” and Fig. 4 below.

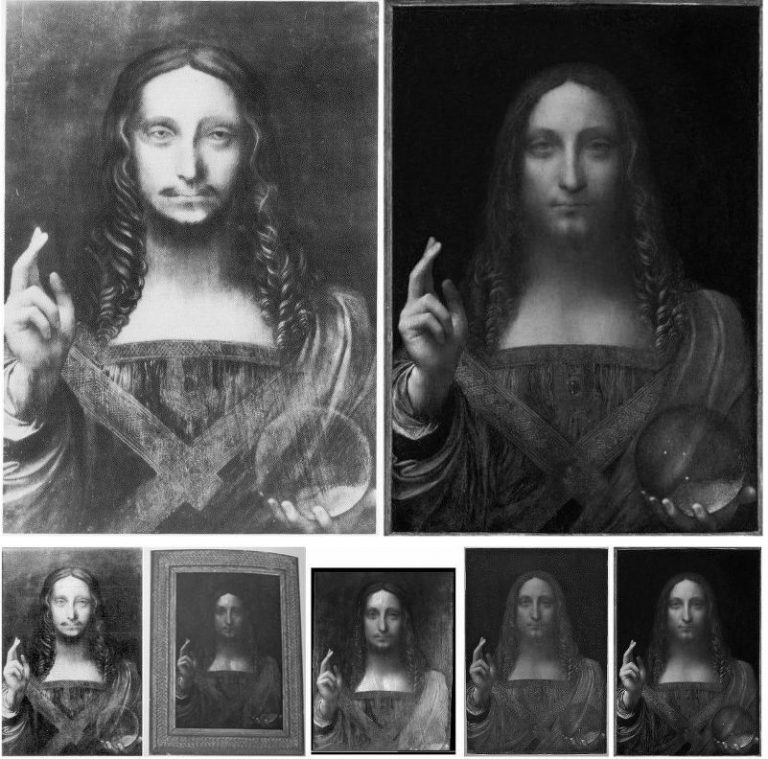

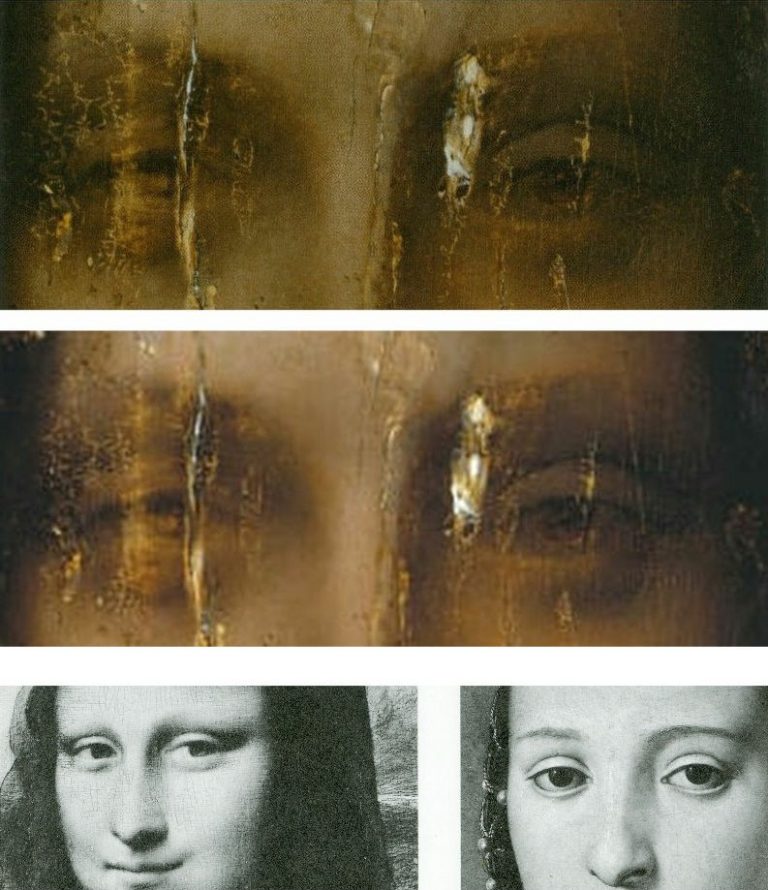

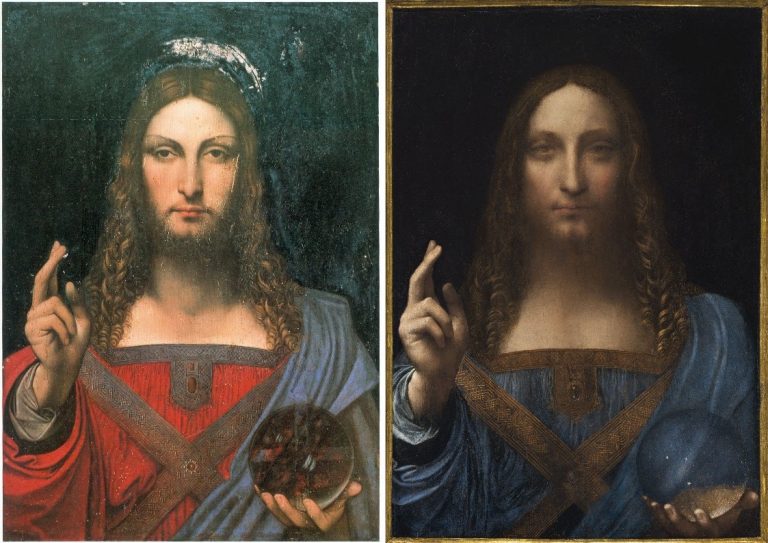

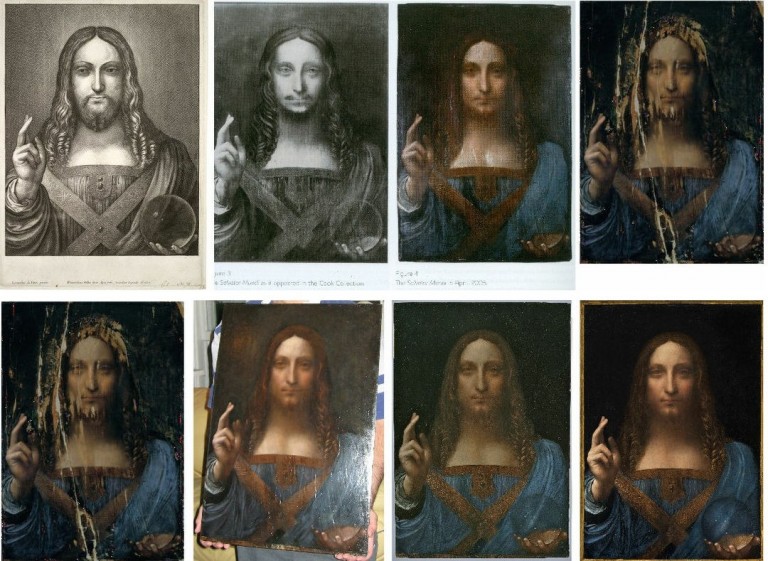

Above, Fig. 2: Top row, the Metropolitan Museum’s Duccio Madonna and Child, as seen in 1904 and in 2004 (when sold for c. $50 million); above, the Leonardo Salvator Mundi as seen in c. 2005 and in 2017 (when sold for $450 million).

Above, Fig. 3: Top row, the present Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi painting as seen in 1912 and when sold in November 2017. Bottom row: as at the same dates but showing some intermediary restoration states.

Attributions, like restorations, are made in socio-cultural contexts. Here, we examine the marketing of the upgraded Salvator Mundi with reference to the marketing of a picture that had received a spectacular upgrading a century earlier – the Metropolitan Museum’s 2004 acquisition of a tiny Duccio Madonna and Child. In both cases we see elevations of studio works that had first emerged at the beginning of the 20th century and were converted through restorations into claimed major autograph works. In both cases, when viewed dispassionately and art critically, the upgraded works are seen to stand anomalous within their allotted oeuvres. In both cases, the elevations thwarted the articulation of potentially more fruitful and better informed art historical narratives.

In studying the two cases we encounter errors of connoisseurship that rest on plain failures to look; failures to discern; and failures to make use of the sharpest art critical tool in the connoisseur’s tool box – the humble photo-comparison. This methodological abstemiousness can seem wilful and perverse as much as neglectful – some disavow photo-testimony outright as a critical tool. In the visual arts, and with today’s greatly enhanced photographic means of reproduction and transmission, there can no excuse for advocates’ declining to provide visual demonstrations of claims made in support of attributions or restorations.

THE PROBLEMS OF SCHOLARLY ADVOCACY ON THE MARKET

Where once a respected scholar might have proposed an attribution in an academic journal or forum in anticipation of critical responses, today, at the high end of the art market, teams of professional supporters are assembled one-by-one behind the scenes prior to some Big Media Announcement of a “discovered” masterpiece. Within such procedures, successive scholars’ invitations to appraise works are inescapably compromised by awareness of already committed supporters. At a certain point of accumulated critical mass it can be felt a) tempting to join and/or b) professionally unwise to dissent openly. A sense can grow that nothing will be permitted to count as evidence against that which has been collectively endorsed, and that any opposition will incur a risk of being dubbed a “hostile” party. At the low end, the trade euphemism for the many restoration-enhanced upgrades is “a sleeper”.

RECENT ARTWATCH WARNINGS AND ENGAGEMENTS

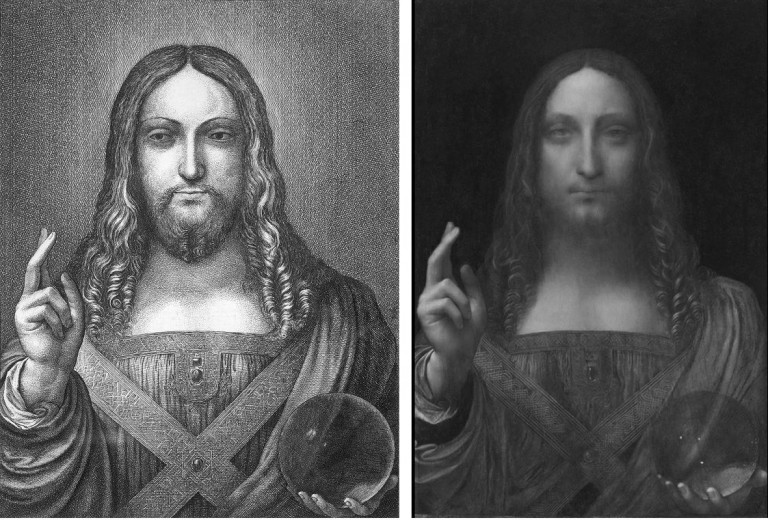

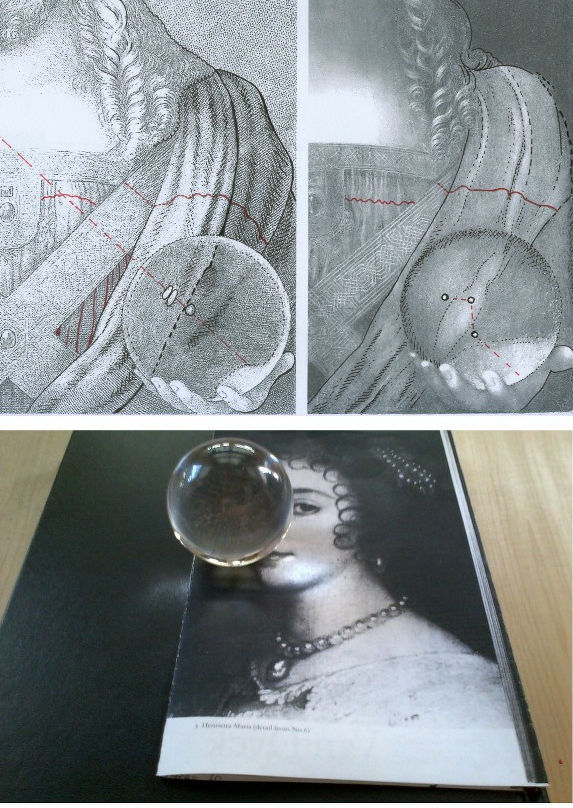

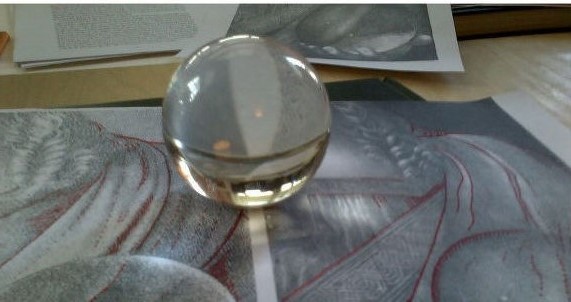

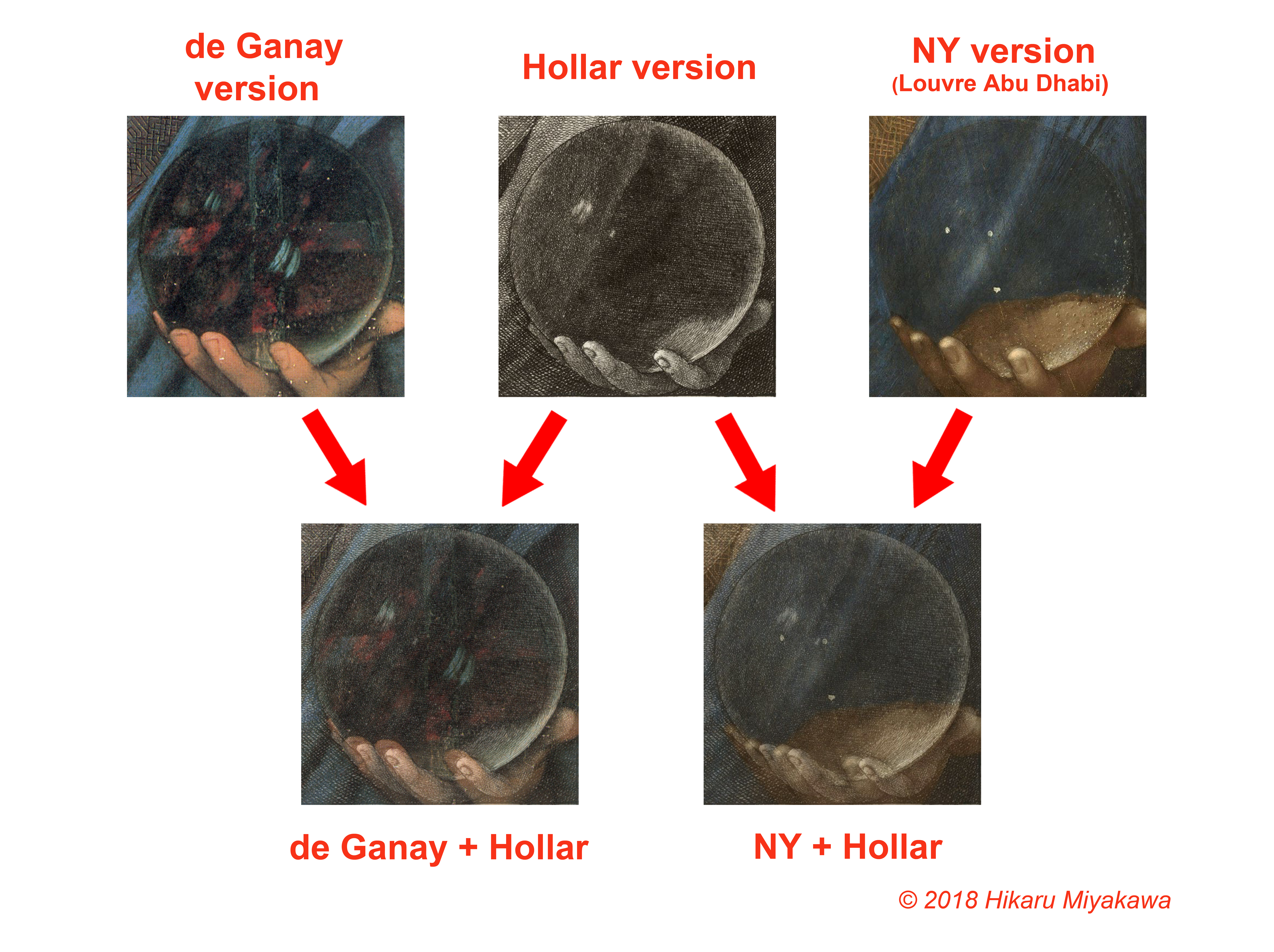

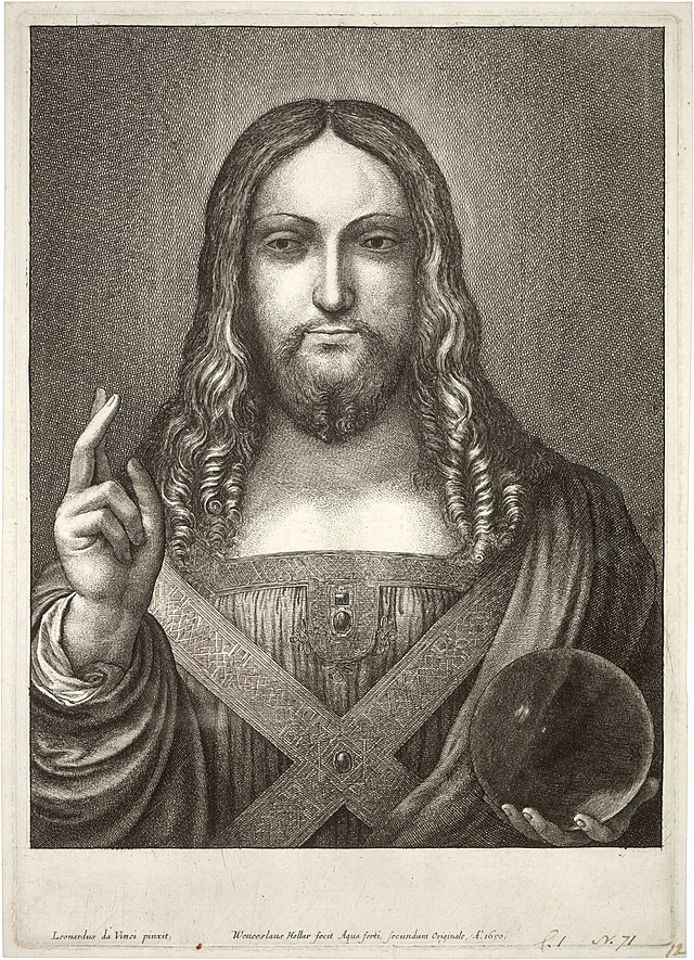

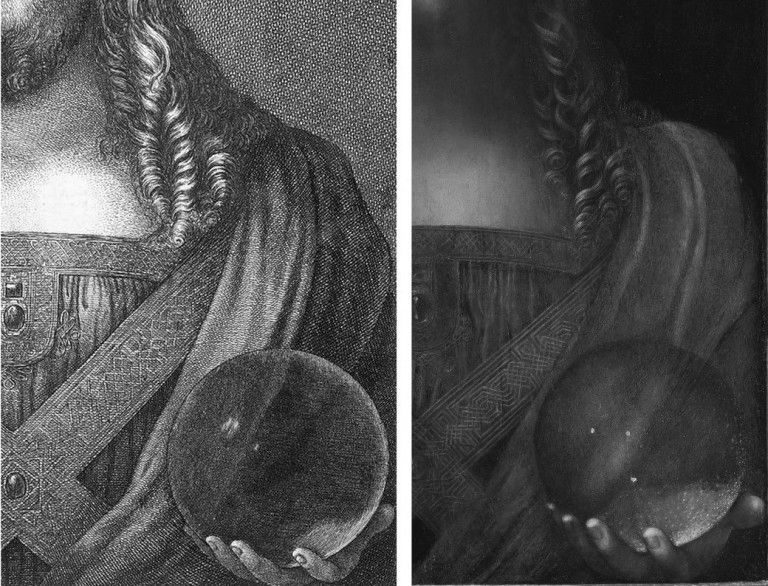

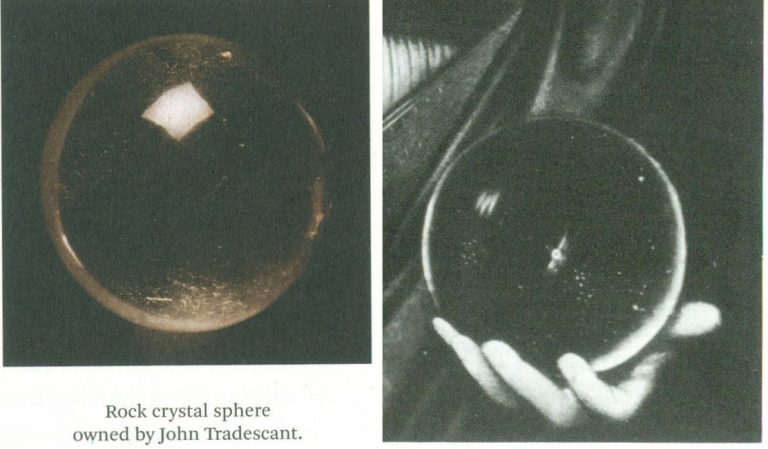

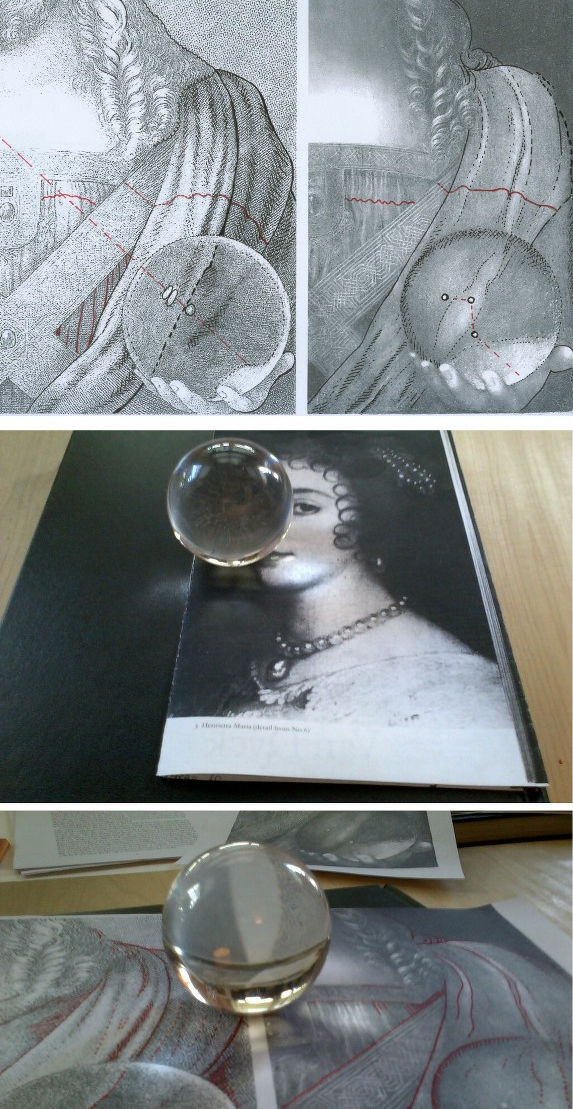

ArtWatch warnings on the Salvator Mundi’s Leonardo attribution: 1) On 11 November 2011 we pointed out (letter, the Times, Fig. 5 above) that the Salvator Mundi painting then on exhibition as a Leonardo at the National Gallery, and that is now the Louvre Abu Dhabi picture, lacked a sophisticated optical effect copied in 1650 by Wenceslaus Hollar from a painting then thought to be a Leonardo. 2) On 19 October 2017, nearly a month ahead of the 15 November sale of the Salvator Mundi at Christie’s, New York, we objected (in the Guardian) that the painting was inconsistent with Leonardo’s depictions of figures; that it lacked the sophisticated optical effects copied by Hollar; and, that there was insufficient evidence to support a Leonardo attribution. 3) On 14 November 2017, the day before the Salvator Mundi sale at Christie’s, New York, we warned that the provenances compiled by the National Gallery in 2011 and Christie’s in 2017 were unsupported, inflated and overly-reliant on then (and still) unpublished researches of one of the work’s first owners – see “Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation”.

CHRISTIE’S MARKETING OF A SALVATOR MUNDI AS A “MALE MONA LISA” AND AN EARLIER CASE

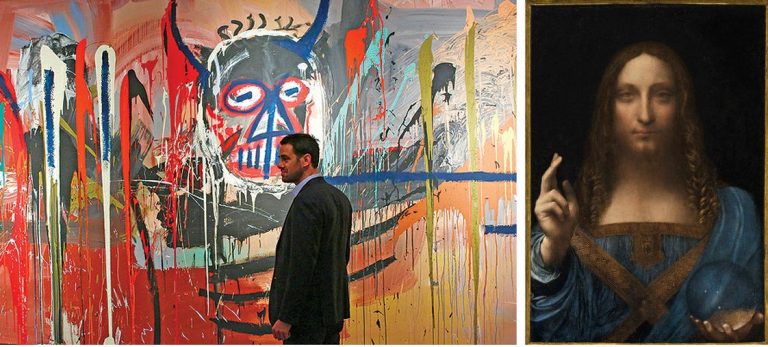

Above, top, Fig. 6: Left, Loïc Gouzer, co-chairman of Americas post-war and contemporary art at Christie’s stands next to “Untitled” by Jean-Michel Basquiat during a Christie’s, New York, press preview; right, the Salvator Mundi when sold as a Leonardo at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 – the last time it was publicly seen. (It is presently rumoured to be in a Freeport storage depot in Switzerland.)

Gouzer, who is leaving Christie’s, had claimed: “Young people look at Leonardo the same way they look at Basquiat.”

The day after Christie’s 15 November 2017 sale of the $450million Salvator Mundi, Thomas Campbell, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, observed that the “eye-popping” price was no surprise in a market where “speculation, marketing and branding have displaced connoisseurship as the metrics of value”.

Todd Levin, an art adviser, told the New York Times: “This was a thumping epic triumph of branding and desire over connoisseurship and reality.” (See “How Salvator Mundi became the most expensive painting ever sold at auction”.)

George Goldner, former chairman of drawings and prints at the Metropolitan Museum, has said the allure of the Salvator Mundi “has nothing to do with art and everything to do with money,” and that “If you were to spend $450m on a rare car or diamond and put it on display, a lot of people would come to see it. If the Salvator Mundi had sold for $20m, nobody would go. Any painting that sells for $450m will attract crowds for a while. Then, all of a sudden, people won’t care anymore”.

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM DUCCIO MADONNA AND CHILD

Above, Fig. 7: Three views of the Metropolitan Museum’s Duccio Madonna and Child

Goldner is right of course – who queues now to see the Met’s famous “Duccio” (Fig. 7, above) which, like the Leonardo Salvator Mundi, emerged at the beginning of the 20th century with no history? The then recently restored Duccio had been launched by Berenson’s wife (Mary Logan) and a protégé (Frederick Mason Perkins) in 1904 at a time when Florence was “a factory of forgers”, according to Federico Zeri, and with modern wire nails embedded under its ancient and battered gilded gesso. By further coincidence, both pictures arrived at the beginning of this century after long absences (1949 to 2004 for the Met Duccio, 1958 to 2005 for what is now the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi-in-storage.)

In hindsight, the sale of the $50 million Duccio in 2004 served Christie’s as a model for that of the Salvator Mundi. The task in both cases was to market as an absolutely secure blue chip autograph old master, a work that had arrived very late in the historical day, without provenance, and from within a large group of related but artistically diverse pictures. Both works were successfully presented by Christie’s, on substantial expert authority, when, on a full art critical and documentary interrogation, neither can safely be so regarded.

Although we still cannot examine the Salvator Mundi’s unpublished technical literature, with the Duccio we can (thanks to earlier generous assistance from Keith Christiansen, the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of European Paintings at the Met) examine that picture’s part-published technical literature and the under-reported means by which it had emerged from an antiques shop a century earlier and was, after restoration, instantly attributed to Duccio by its owner. As with the Salvator Mundi, there is no record of such a work having been produced by Duccio and no attempt has been made either to demonstrate that the Met picture was an original prototype for the many other versions of the type or to acknowledge the many historic variants themselves. Instead, five modern forgeries of the Berenson-upgraded Duccio are cited by Christiansen on grounds that they “testify to its prestige.”

THE MET DUCCIO CONTROVERSY LITERATURE:

The case for the Metropolitan Duccio has been put principally by Keith Christiansen in: the Fall 2005 Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (“Recent acquisitions”, p. 15 – “among the most important single acquisitions of the last two decades”); an October 2007 Apollo article, “The Metropolitan’s Duccio” – which was described as “the first full account”; the Summer 2008 Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin – “Duccio and the Origins of Western Painting”; also in 2008, a special Met re-printed publication, Duccio and the Origins of Western Paintings.

The case against was put by Professor James Beck in the last chapter of his 2006 book From Duccio to Raphael – Connoisseurship in Crisis, and by Michael Daley who, after corresponding with Christiansen over the attribution, published three articles in the Jackdaw magazine between November 2008 and March 2009: “GOOD BUY DUCCIO?”; “BUYER BEWARE”; “TOXIC ATTRIBUTIONS?”

FURTHER SALVATOR MUNDI AND MET DUCCIO CONNECTIONS: MARKETING THE ATTRIBUTIONS

As with the Salvator Mundi, Christie’s marketed the painting as a “Last Chance to Buy a Duccio”. Christiansen is listed by Christie’s as one of the Salvator Mundi’s supporters, as also is the Met’s chief picture restorer, Michael Gallagher, and as was Christiansen’s predecessor as paintings’ chairman, the late Everett Fahy.

When purchased, the Met Duccio had never been technically analysed. This long out-of-sight work was only subjected to technical analysis by the Met after acquisition and after challenges to its authenticity had been made by Beck and other scholars. As with the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi, the subsequent technical examination reports were not published or made available to independent scholars.

GUSH, ACQUISITIONS, SUSCEPTIBLE VIEWERS, SYCOPHANCY AND ABSENCES OF “STYLE CRITICISM”

Like Robert Simon on the Salvator Mundi, Keith Christiansen is a life-long devotee of the artist in question. His accounts of the Met Duccio have inclined towards the rhapsodic while eschewing direct engagement with style criticism. He recalls being struck on his first (2004) encounter with the Duccio at Christie’s, London, that “Like a poem or a piece of music, a great work of art – even a very small one – it has the power to cast a spell over susceptible viewers, to draw them into the world of its creator. For a few moments we were silent, each of us registering our impressions… Ever since, almost forty years ago, I first stood before the Maestà in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena, I have been haunted by Duccio’s singular gift for suggesting an ineffable, sacred presence in his depictions of the Virgin and Child, and it is this quality that first struck me – except that in this small picture there is an intimacy in the relation of mother to child that is quite different from what one finds in the artist’s public altarpieces, and the face of the Virgin is touched by a haunting melancholy even more poignant than I remembered from his larger public paintings…I knew the picture from old black and white photographs in books on Sienese painting and the two principle monographs on Duccio and his followers…There are few works of art I longed to see more than this small but astonishing picture…[which] would have been at the top of anyone’s wish list for acquisition…”

With big acquisitions museums take hyperbole and heroising gush to be in institutional order. The Met Duccio was by far the museum’s costliest ever and for a while it sparked an ecstatically uncritical hysteria. A New York restorer/dealer, Marco Grassi, for example, likened the picture’s emergence to the discovery of a manuscript score for a Mozart quartet. The world had earlier missed the chance to see it, he wrote (New Criterion, February 2005), because it was “on its way to London to be offered for sale, privately, through Christie’s.” But then, the happiest of endings:

“The Stoclet Duccio – we can now proudly call it ‘the Metropolitan Duccio’ – is an astonishing achievement…the artist places the Virgin at a slight angle to the viewer, behind a fictive parapet. She gazes away from the Child into the distance while He playfully grasps at Her veil. One must appreciate that every aspect of this composition represents a departure from pre-existing convention. With these subtle changes, Duccio consciously developed an image of sublime tenderness and poignant humanity, almost an echo of the spiritual renewal that St. Francis of Assissi had wrought only a few decades earlier…If, adding ‘strength to strength’ is a judicious policy in building collections, then, with the addition of the Duccio, its rewards will be particularly bountiful for the Metropolitan…And so, the Metropolitan’s recent arrival now rules supreme in this exalted company, and surely this could not have happened were it not for the outstanding quality of the museum’s curatorial resources. Chief Curator Everett Fahy and Associate Curator Keith Christiansen of the Department of European Paintings, in addition to Laurence Kanter, Curator of the Lehman Collection, constitute, together, a particularly prestigious concentration of scholarly expertise in the field in earlier Italian painting. No other museum can boast of a more distinguished team. One suspects that they, more forcefully and convincingly than anyone, made the case for the Metropolitan’s prodigious expenditure, and their advocacy merits our gratitude and applause…”

The celebration of “every aspect a departure” within an oeuvre is an inherently problematic and art-critically dangerous intoxication.

HOW A DREAM WISH MATERIALISED

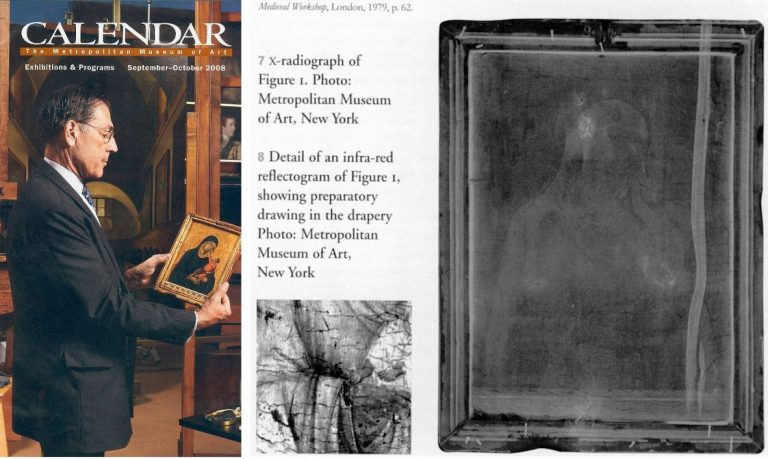

Above, Fig. 8: Left, the Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Philippe de Montebello contemplating the museum’s Duccio Madonna and Child (after its acquisition); centre, a fragment of an infra-red image of the painting, as published in Apollo in 2007; right, an x-ray of the framed Metropolitan Duccio panel, also as published in Apollo and showing the modern wire nails that no one had noticed or acknowledged.

Christiansen described how the Duccio picture was drawn to his attention in Danny Danziger’s (endlessly fascinating) 2007 Museum – Behind the Scenes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

“Nicholas Hall of Christie’s, with whom I have been friends for many years, phoned me up and said ‘I would like you to have lunch with me; there is something I’d like to show you.’ During the meal he slipped me a transparency, and I looked at it. It was a painting that had not been seen by any of the major Duccio specialists for fifty years…”

What could possibly go wrong? Nothing, Christiansen clearly thought: “…it had been in the Stoclet family and out of circulation. ‘Fantastic, how about the price? I asked. He told me. OK, I said, ‘I will deal with that later.’ And then we finished lunch.” Note, re frequently disparaging art world dismissals of photo-testimony, first, a curator had committed to the cause of a work he had never seen on sight of a single photograph; second, the Met’s director, Philippe de Montebello, would also become hooked on the painting through that photograph; third, that for over half a century, professionally-speaking, the picture’s Berenson-made attribution had been sustained on photo-testimony alone. Christiansen would later put it like this: “In 1949, [the then owner of the Duccio, the financier Adolfe] Stoclet and his wife died within a short time of each other. The collection was divided among their children, but access to it was increasingly difficult and there was even uncertainty as to whether the Duccio had been sold. The result was that a generation of scholars had to formulate their opinions on the basis of photographs, of which, fortunately, extremely good ones had long been available.”

THE CIRCUMSTANCES CONCERNING THE WITHDRAWAL FROM THE 2003 SIENA EXHIBITION

In Calvin Tomkins’ 11 July 2005 New Yorker article “The Missing Madonna”, it is said that the Met’s then head of European paintings, the late Everett Fahy, visited the Stoclets’ house in Brussels in 2002 to negotiate with of one the relatives for the Duccio’s loan (later rescinded) to the 2003 exhibition in Siena. Fahy may possibly have been the first scholar to see the painting in over fifty years. Tomkins reports Fahy saying that the picture “still hung then where it had always had, in Adolphe Stoclet’s private studio”. Christiansen later reported (Apollo 2007) that “Stoclet did not hang his gold ground pictures in this modern [Josef Hoffmann-designed house] setting but kept them in a large cupboard, taking them out, one by one, on Sunday afternoons or on the occasion of a visit of a guest such as Berenson.” Kenneth Clark had been the source of the cupboard storage claim. Fahy noted, “Everything the Stoclets collected was something you could put in your hand, small and precious”. Small, but not always precious. As Frances Vieta established (and Beck acknowledged in his 2006 connoisseurship book), Stoclet had owned two little Duccios, one of which proved to be a modern forgery in 1989. It, too, had been attributed to Duccio by Berenson’s protégé, Frederick Mason Perkins, who, along with Berenson’s wife, Mary Logan, had also upgraded the Met Duccio Madonna and Child, and two hugely expensive sculptures bought by Helen Frick that were also subsequently exposed as modern forgeries. Berenson himself had been taken in by half a dozen or so modern forgeries. The Cleveland Museum had been taken, too, but recovered when it identified modern wire nails and paints in a “Sano di Pietro” and declared it a fake. Before the Met picture had been first upgraded to Duccio by its owner, some had thought it a Sano di Pietro. The Cleveland Museum downgraded another Sano di Pietro to a school work when it – like the Met picture – was found to contain azurite not ultramarine. “With attributions”, Fahy held, “it’s not the number of people who agree with you, it’s the quality of their judgments.” The Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi had, reportedly, been unsuccessfully offered to Christie’s in 2005.

The Met picture, having narrowly missed a public viewing in the 2003 Siena exhibition for Duccio and his followers, suffered further non-visibility when Christie’s put the newly-emerged work into a private sale among just three major museums: the dollar-rich Getty Museum, which had balked at the asking price; the Louvre, which was said to be working on getting the money for the (then and still not-disclosed) asking price; and the Metropolitan Museum. Under this private sale arrangement it is possible that barely more than a dozen experts had seen the painting before it was sold to the Met and thereafter was trumpeted as an unquestionably autograph seminal and revolutionary work in the history of Western painting – and all this, as mentioned, ahead of a technical examination. The avoidance of public scrutiny during the sale seems to have occurred by design, not accident. Calvin Tomkins, whose New Yorker disclosures have not, so far as we know, been challenged, added:

“Although the ‘Madonna and Child’ was well-known in art-historical circles as the only one of Duccio’s dozen or so surviving paintings to remain in private hands, its whereabouts had been uncertain since the death, in 1949, of its last registered owner, the Belgian collector Adolphe Stoclet. In fact the picture never left the Stoclet House in Brussels. Stoclet and his wife… had willed the house to their son, Jacques, whose widow held onto it until her death in 2001. Soon after that, her heirs, (four daughters) who are very high on anonymity, agreed to lend it to an important exhibition in Siena, Duccio and his school…a few weeks before the opening in 2003, the painting was withdrawn. This coincided with rumours of an impending sale, which turned out to be true.

“Although everyone involved in the transaction is bound by omertà, it is known that both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the principal auction houses, engaged in lengthy and fiercely competitive negotiations with the heirs, and Christie’s eventually won the prize. ‘The family was very keen that the painting go to a public museum or institution,’ according to Nicholas Hall, international director of Christie’s Old Masters department. This was one reason that the family decided upon a private ‘treaty’ sale, in which the auction house and the seller determine the price and then offer the work to selected potential buyers, rather than letting it take its chances at public auction; another reason was that a private sale is more private. ‘We got it by putting a significantly higher valuation on the painting than anyone else – by multiples – based on its being the last Duccio in private hands and its being so impeccably preserved,’ Hall told me. Hall himself never met the sellers. ‘The contract document must have been four inches thick, and it was the most rigidly controlled transaction I’ve ever been involved in,’ he said…”

CHRISTIE’S LAVISH PRESENTATION LITERATURE

Tomkins reported that, in addition to the transparency, Nicholas Hall had given Christiansen the “lavish presentation booklet that Christie’s had prepared for prospective buyers”. On whose imprimatur or on what scholarly authority had that booklet been prepared? How many people got to see it? When Christie’s auctioned the Salvator Mundi, the publicly-disseminated provenance was frankly acknowledged to have derived from the National Gallery’s 2011 catalogue entry; the restorer’s 2012 report; and, through their declared joint indebtedness, to the (still today) unpublished researches of one of the original 2005-2012 consortium of dealer/owners.

A COURTIER FLATTERS?

When Christiansen left his lunch with his old friend at Christies, he wondered what to do next about the tiny work he considered “probably the most important early Italian picture that could ever come on the market”. Should he call his director who was on vacation in Canada? He decided to wait: “and then I went into his office and said, ‘I am duty bound to show you this,’ and then I showed him the transparency. I casually said to him, ‘You know, Philippe, you deserve this picture. Tom Hoving had his [1970 $5.5 million Velazquez] Juan de Pareja, Rorimer had his Rembrandt [“Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer” for $2.3 million in 1961]; I don’t see why you shouldn’t have this towards the end of your career’.”

Christiansen continued (to Danziger): “My director fortunately is a person who loves old master paintings, who grew up with old master paintings and worked as a curator in this department and does not need to be told much. He was completely riveted by it. He asked me the price while he kept looking at it, and then he said, ‘I don’t see how we can get it…’ But that, I imagine, was also when the wheels began to turn in his head, because when I left, I thought there was a real possibility.” In the heady post-acquisition days of November 2004 Christiansen recalled to Carol Vogel in the New York Times that when the director was first shown the photograph “it took him about 30 seconds to say ‘We really have to have this’”.

At the same time, Tomkins had made clear why de Montebello might have gagged on the price. The Getty Museum (which has been bitten by fakes) had already turned it down: “reportedly, because of the price. This struck Christiansen as ironic because the price was so clearly predicated on the fifty-five million dollars that the Getty had agreed to pay, two years earlier, for Raphael’s small, perfectly preserved Madonna of the Pinks.” That little Raphael in the mint of condition had, like the even littler Met Duccio, lost its original back when, for some reason it was polished by its artist/restorer/dealer/smuggler owners. When the cradle was removed from the back of the by-then Met Duccio, it was found to have been scraped down to the bare wood, on which was written an ascription to…a member of Duccio’s school. Like the Salvator Mundi, the little Raphael was one of many versions of the subject – there are over fifty-five Madonna of the Pinks. James Beck remarked in his 2006 connoisseurship book: “I find it appropriate to claim, given the situation as has already been sketched, there is no chance whatever that the Northumberland painting is an original Raphael.” But for sure, within a couple of weeks of seeing the photograph, de Montebello, Christiansen and the Met’s chief restorer, Dorothy Mahon, flew to London to see the Madonna and Child armed with a magnifier and a UVF lamp to spot retouches.

BUY FIRST LOOK AFTERWARDS

The next morning, after a couple of hours of inspection at Christie’s in London with Christiansen and Mahon, de Montebello made a quick and high offer (without Board authorisation). It was immediately accepted by Christie’s but under the terms of this “private treaty sale” the picture could not be removed from Christie’s to undergo examinations at the Met and be presented to the Board’s Acquisitions Committee for appraisal and possible approval, as was customary. This was because, as Christiansen put it, “the picture wasn’t leaving Christie’s until the whole deal was finished”. Why so – and why accepted by the Met when such a huge sum was at stake? Had this condition been stipulated by owners who seemingly had developed cold feet about the picture being seen for the first time in over half a century in the context of a show on Duccio and his followers?

In his 1993 memoir Making the Mummies Dance Thomas Hoving recalled that when he went to Christie’s in London in 1970 (with the then head of restoration, Hubert von Sonnenberg, Everett Fahy, and a Board member, Ted Rousseau), the chairman of the auction house, Sir Peter Chance – “the very symbol of upper-class culture neatly folded around commerce” – explained “The condition’s perfect…the picture will not be cleaned up for the sale. Lord Radnor forbids it. He is also against anyone…examining it…scientifically. But no matter, we all matriculated into connoisseurs without all these fashionable instruments, if I may say so, Dr. von Sonnenberg.” (Hoving was bemused when Sir Peter put the price at “approaching the two million guinea mark” – a guinea being a pound, plus a shilling: “While Sotheby’s always conducted their sales in pounds, Christie’s favoured the more pretentious guinea.” In those days the joke was that at Christie’s gentlemen pretended to be salesmen while at Sotheby’s salesmen pretended to be gentlemen. In today’s globalised ownership-fluxing art world it might prove impossible to slide a cigarette paper between them.)

That Velazquez painting truly was one of the greatest portraits ever to come to market – and, in some part it was so because it had probably not been touched in a century and a half. When the Met staffers revisited the next day, von Sonnenberg held the picture against the window when the guard left the room and discovered that it had never been lined – hence the extraordinary vigour and sparkle of the brush work. As soon as Hoving and von Sonnenberg took possession it was sent secretly to Wildenstein’s – not to the Met itself – and there it went straight under the conservation chemical cosh on a claim of dirty varnish-removal but, in reality, in conformity with the museum’s imperious proprietary and aesthetic imperatives. (See “Discovered Predictions: Secrecy and Unaccountability at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York” and “Why is the Metropolitan Museum of Art afraid of public disclosures on its picture restorers’ cleaning materials?”) Even before it might become “The Metropolitan Velazquez” the portrait became a Met-treated painting and no one else at the museum, let alone its paying public, ever got to see the great masterpiece in its unadulterated state. To his credit Rorimer had earlier confessed (privately) to Alexander Eliot that the Met’s restorers had ruined its Rembrandts – and those poor paintings were not alone:

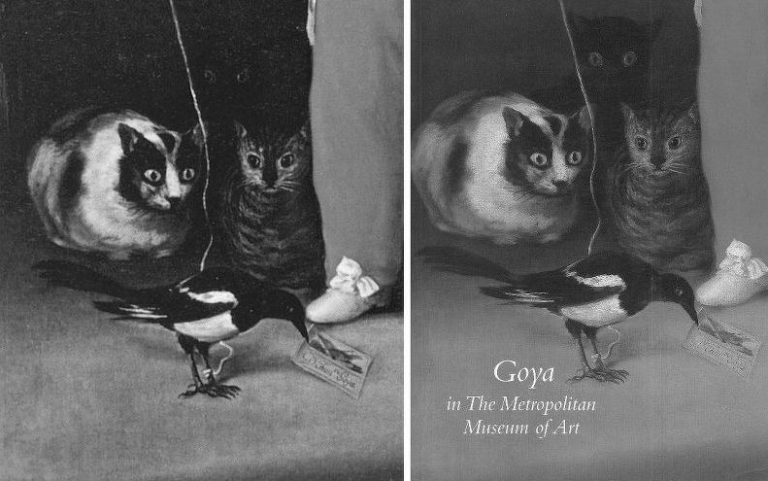

Above, Figs. 9 and 10: Details of the Met’s Goya portrait of the young Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga who died before he was eight years old. As seen before cleaning (left) and after cleaning (right).

In July 2005 Philippe de Montebello explained to Calvin Tomkins (New Yorker): “It’s the single most important purchase during my twenty-eight years as director – It’s my ‘Juan de Pareja’, it’s my ‘Aristotle.’” De Montebello later explained in the Summer 2008 Met Bulletin that he had moved so fast on an unexamined work because he felt authorised by:

“the assurance that comes from the trust I have learned to place in the curators and conservators of this great institution…As I held the picture in my hands, enraptured by its wonderful quality…I was treated all the while to Keith’s impassioned scholarship…it was particularly Keith’s precise and learned assessment of the picture that allowed me to consider the acquisition an imperative.”

(For a fuller account of de Montebello’s decision to buy, see CODA below.)

Immediately after spending nearly $50million on the unexamined Duccio at Christie’s in London, Christiansen, de Montebello and Mahon went to see the National Gallery’s Duccio triptych The Virgin and Child with Saints. Christiansen recalled (as reported in Danziger, 2007): “After about two hours at Christie’s we all walked down to the National Gallery where they have a very rare and beautiful Duccio triptych, which is simply marvellous – a touchstone of Duccio’s work – and we all felt that ‘ours’ was every bit as fine and in certain respects, more intimate and direct.” The following year, in a foreword to the 2008 Summer Met. Bulletin Christiansen elaborated:

“…we decided to walk the few blocks to the National Gallery, which owns a portable triptych by Duccio that has long been a cornerstone of its superb collection of early Italian paintings. The triptych is a work of extraordinary beauty and impeccable craftsmanship. Duccio struck a slightly different key than in the picture we had been examining, placing greater emphasis on the regal bearing of the Virgin. The motif of the Child playing with his mother’s veil is further developed, so that Christ unfurls a rich cascade of folds. But these enhancements came at the expense of the simple dignity and touching humanity of the small panel we had seen at Christie’s. In short, we felt that we had before us the opportunity of acquiring a painting that was on a par with one of Duccio’s most admired and best-preserved works, a painting that represented the artist at the very height of his powers.”

Michael Daley, Director, 6 February 2019

In Part II we consider why the Met team might have been advised to view the National Gallery Duccio triptych (and its dossiers) before visiting Christie’s and buying on the spot.

CODA:

Martin Gayford accompanied Philippe de Montebello on a walk around the Metropolitan Museum, as recorded in his 2014 book RENDEZ-VOUS WITH ART. In his chapter “The Case of the Duccio Madonna”, Gayford wrote: “We ended up sitting on a bench near perhaps Philippe’s most celebrated acquisition: a small exquisite Madonna and Child by the 14th century Sienese master, Duccio. It remains the most expensive single object ever purchased by the museum. So how, I asked, did he make the momentous decision to buy it?” De Montebello replied:

“When the Duccio was on offer, I had, as Director, to decide whether the picture was worth the huge sum I would have to raise to acquire it. To arrive at this decision, I had to wear several hats all at once: one of these was that of an informed art lover, the French ‘amateur’, and in that role focus on the seductive and lyrical lines, the harmony of the colours, the felicitous choreography of the hands and feet, the wonder of the human contact coincident with a certain respectful detachment in the depiction of figures, that are, after all divine. I also had to don my art historian’s hat and note that this Duccio was one of the very first pictures that mark the transition from medieval to Renaissance image making. It represented a key moment, a break from hieratic Byzantine models to a more gentle humanity.

“To be more specific, and it is more than just a recondite detail, look at how the parapet at the bottom connects the fictive, sacred world of the painting with temporal one of the viewer. This important observation – among others – was made by the curator Keith Christiansen as we were examining the picture in London. This led him to conclude that Duccio must have seen the Giotto frescoes in Assisi depicting the life of St. Fancis, where the illusionistic framework, including the parapet, relates the narrative scenes to the architecture of the church.

But Martin, you want to know the truth? All those considerations were largely irrelevant when the time came to decide whether to spend in the region of $45 million on the work. For this, I needed my museum director’s hat. The quantitative assessment had to be based on different criteria. First and foremost were the old-fashioned notions of quality, craft and skill. Did the work sing? Did it stop me in my tracks and did it then hold my attention? Was I reluctant to turn away from it too quickly?

“However, in my mind, the question of relative importance and quality was always pushing itself forward. That the work was beautiful and admirably well painted was not enough. It needed also to be very important, exceptional in every way, and extremely rare. If there had been three or four others similar to this one it would have meant that this picture should command a lower price.

“Then there was the question of what the price of this panel should be in comparison with one of the missing predella panels from Duccio’s Maestà in Siena were it to come up for sale. This is because the Madonna was and is a self-contained, independent and devotional image; it doesn’t belong to a larger work, the wholeness of it is part of its beauty and impact. The entire story is there in that one painting. That, too, added to its value.

“Then, as curators, we also needed to be concerned with the physicality of the work. After all, this object, which can be held in the hand, has weight and a certain thickness, and is vulnerable to the vagaries of time. Part of what drove me to buy the Duccio was the fact that for close to an hour I did hold it in my hands, that I did turn it around, looking at the back, sensing its weight, measuring its thickness. It had a corporeal reality that was almost, to use a paradox, mystical.

“No longer bound by image alone, as one would be when looking at a photograph – or even from a distance – I then focussed on the deep burn marks at the bottom of the frame, obviously made by votive candles, confirming that this was indeed a devotional picture. Just a few additional details resulted from close examination, not the least of which was that the picture was in impeccable condition, a rare thing when it comes to Trecento gold ground pictures, as most works have suffered greatly over time, mostly I’m afraid at the hands of restorers.

If you are a student of art, just think of the Jarves collection at Yale, where many of the pictures, early renaissance works, are now a near total ruin. We were also able to confirm that this was indeed not an incomplete work, a wing of a Diptych for example, there is a hole at the top indicating that the picture was hung from a hook.

“Then, of course, came the issues of the provenance or ownership history, an important preoccupation of art historians, for what it may reveal about the work. While it obviously began life as a devotional picture, made for an unknown patron, it eventually ended up in the hands of two major European collectors: Count Grigory Stroganoff at the end of the 19th century, and later the Belgian financier Adolphe Stoclet, in his Brussels house, which is a masterpiece of the Wiener Werkstätte. Also, the Duccio had been lent to the great Sienese exhibition of 1904 where it was highly praised; indeed one art historian Mary Logan (Bernard Berenson’s wife), deemed it the single finest work in the exhibition.

In addition, and not a minor factor in gauging the price, was the knowledge that there would most probably never be another Duccio for sale, as this was the only work of his known to exist outside of a museum. I also knew – which is why I made a quick and high offer – that the Louvre, the other major museum that did not have a Duccio, was after it as well and was going to make a real effort to buy it.

“So some competitive nerve was struck, and thus the need for pre-emptive action. While it may not have been conscious, I think that there is no question that a part of me wanted my institution to own that Duccio – over and above its importance to the proper representation of the development of Sienese art in the Trecento – simply to have it as yet another major work that would confirm the stature of the Met.

“At this point, the sum of all the above, which occurred in a rush of sensory and intellectual responses, led to an important psychological factor, which should not be underestimated in such cases: it is that of the curator/acquisitor experiencing what is a quasi-libidinal charge (you might even call it lust, albeit of a high order); the irrepressible need to win; to have taken the object of desire. You can’t get away from that. We are all human beings. Institutions are not just made of stone, glass and steel, they are run by people. It is absurd to try to maintain and project total objectivity.

“As a result of all these considerations, these thoughts, observations, calculations and feelings, as well as the confidence I gained from learned colleagues, the Met boasts this masterpiece of Trecento painting, while the Louvre, with its outstanding collection of Italian paintings, is still, and may forever be, lacking a Duccio. This actually saddens me, and I hope that a fine Duccio does turn up someday, from somewhere, and they can get it.”

Two troubled Leonardos

Two supposed Leonardos are now in difficulties. The Salvator Mundi, sold for half a billion dollars just over a year ago, hasn’t been seen since. In France, the Saint Sebastian drawing saved for the nation was not bought and has now been put back on the international market.

In the Guardian today (“An £18m saint…but is Sebastian drawing really by Leonardo?”) Dalya Alberge reports that the Leonardo scholar Martin Landrus believes the recently discovered and attributed ink drawing of a Saint Sebastian that is being offered by the Tajan auction house is not entirely – or, rather, is mostly not by Leonardo. Dr. Landrus was struck by poor ink drawing “nervously traced” over “much lighter lines that may have been autograph”. Possibly so, but ink lines studiously executed over faint guidelines made in erasable materials like chalk, charcoal or pencil in what would appear to be a quickly executed inventive study (as opposed to a drawing made from an already posed life model) are also encountered in pastiche inventions made by third parties.

The possibility should also be considered that this newly-emerged Saint Sebastian (above right) is a “portmanteau” drawing composed from elements borrowed or adapted from bona fide Leonardo drawings such as the Saint Sebastian ink study (above left) in the Hamburger Kuntshalle. In questions of attribution, differences or inconsistencies weigh more heavily than similarities and correspondances. Both drawings above are made of ink over fainter drawing. Both are of Saint Sebastian tied to a tree. However, notwithstanding the subject’s extreme plight, the Hamburg figure is a clear adaptation of a classical figure: the raised shoulder is placed above a stretched torso contour, while the lower shoulder is placed above a raised hip with the inescapable consequence that the torso’s contour is compressed and bunched (see the comparison with a real figure below). Throughout the Hamburg drawing the lines are spare, elegant and sometimes almost notational – see the way the centre line that begins under the rib cage shifts into alignment with the plane of the abdomen which is set in opposition to that of the chest. There is no such clarity and figural acuity in the newly-emerged drawing even though it contains considerably more drawn marks. Where the Hamburg drawing has three differently placed heads (two inked and one in chalk or pencil) all are individually compatible with the body, while in the Tajan auction house drawing the single head is snapped and twisted back in almost broken fashion and there are two radically conflicting poses in the torso below it. In one of these both arms are tied behind the tree in a manner that leaves the true left shoulder dropped below that of the right. In the alternative version the situation is reversed: the true left arm has been pulled up as if tied to a higher branch but this dramatic change of design and anatomical orientation carries no consequences for the rest of the figure: the abdomen remains untidily anatomically bunched. The true left breast remains dropped below that of the right, even though the true left shoulder has been rotated both upwards and backwards. It is hard to believe that so great a draughtsman as Leonardo could have confined such a radical shift of positioning to a single discrete part of a figure. As well as anyone Leonardo understood the manner in which bodies combine “architectural” structures with fluidity, mobility and grace. By contrast, it is easy to imagine how someone wishing simply to compose a study in the manner and style of a Leonardo sketch/design might commit such solecisms.

(For discussion of the rising tide of discovered works by great old masters, see our 15 December 2016 post “Leonardo and the Growing Sleeper Crisis”.)

Michael Daley, 17 November 2018

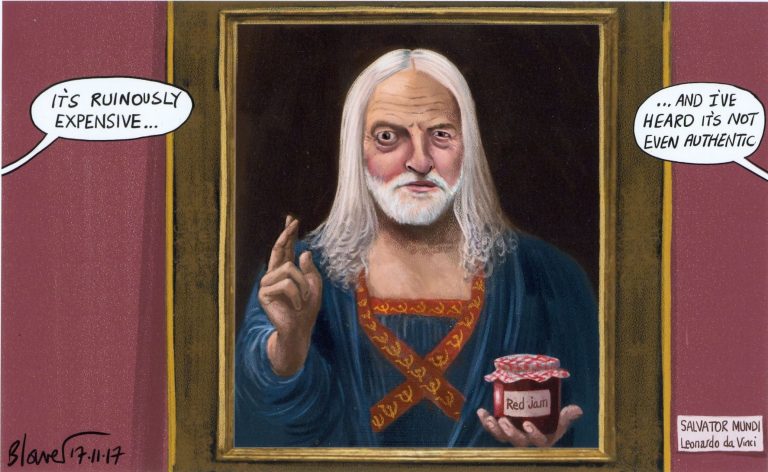

The pear-shaped Salvator Mundi

Things have gone very badly pear-shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. It took thirteen years to discover from whom and where the now much-restored painting had been bought in 2005. And it has now taken a full year for admission to emerge that the most expensive painting in the world dare not show its face; that this painting has been in hiding since sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 for $450 million. Further, key supporters of the picture are now falling out and moves may be afoot to condemn the restoration in order to protect the controversial Leonardo ascription.

Above, Fig. 1: the Salvator Mundi in 2008 when part-restored and about to be taken by one of the dealer-owners, Robert Simon (featured) to the National Gallery, London, for a confidential viewing by a select group of Leonardo experts.

Above, Fig. 2: The Salvator Mundi, as it appeared when sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017.

THE SECOND SALVATOR MUNDI MYSTERY

The New York arts blogger Lee Rosenbaum (aka CultureGrrl) has performed great service by “Joining the many reporters who have tried to learn about the painting’s current status”. Rosenbaum lodged a pile of awkwardly direct inquiries; gained a remarkably frank and detailed response from the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini; and drew a thunderous collection of non-disclosures from everyone else. A full year after the most expensive painting in the world was sold, no one will say where it has been/is or when, if ever, it might next be seen. (See “Leonardo Canards: Conservator Dianne Modestini Debunks Doubts Over the Elusive ‘Salvator Mundi’”.)

After the Salvator Mundi’s recent no-show at Abu Dhabi Louvre, concerns and rumours have grown exponentially. (See our “Two developments in the no-show Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi saga” and “How the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi became a Leonardo-from-nowhere”.)

AN ENDURING SUPPORTER

Throughout this protracted no-show, Professor Martin Kemp, the most high profile art historical advocate of the painting’s Leonardo attribution, has offered assurances. Immediately ahead of the November 2017 sale he made a promotional video for Christie’s, New York, that was specifically designed to combat our and other warnings, warnings that he now characterizes in his self-valedictory memoir Living with Leonardo as “misinformation appearing in the press”. The Times reported on 28 August: “‘looking at the whole science’ including the rock crystal sphere that Christ was holding and the depth of field convinced [Kemp, that] ‘with Leonardo you have this wonderful body of context, of extra evidence…it is rock solid, it is damaged but rock solid’.” Kemp frequently fuses appeals to rock solid scientific evidence with art critical hyperbole. For example, to the owner of the supposed Leonardo drawing “La Bella Principessa”, he said of a partial finger print:

“This is yet one more component of what is as consistent a body of evidence as I have ever seen. I will be happy to emphasize that we have something as close to an open and shut case as is ever likely with an attribution of a previously unknown work to a major master. As you know, I was hugely sceptical at first, as one needs to be in the Leonardo jungle, but now I do not have the slightest doubt that we are dealing with a work of great beauty and originality that contributes something special to Leonardo’s oeuvre. It deserves to be in the public domain.”

So far as we know, that supposed Leonardo drawing (which the National Gallery excluded from its 2011-12 Leonardo show) remains unsold in one of Yves Bouvier’s freeports. Kemp recently assured the world that wonderful things are in train for the Salvator Mundi next year. Against his bullishness, the picture’s long-serving restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini, has now disclosed to Rosenbaum: “I have no idea about the future of the painting. No one does. Not the French, not Martin Kemp. I assume the people from Abu Dhabi know something, but they are not talking to anyone, not even the French.”

Rosenbaum had tried the Louvre, Paris:

“I thought the venerable French museum would at least be able to answer my question regarding its own exhibition plans, but Sophie Grange of the Louvre’s press office said only this: ‘It is too early, one year ahead, to communicate on the list of the loans for the Louvre exhibition. Concerning Louvre Abu Dhabi, they communicate themselves about their own collection.’ Grange advised me to get in touch with Faisal Al Dhahri at Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism—one of the three officials whom I’d already attempted to contact several times, to no avail. I think this is called: ‘Getting the Run-Around.’”

THE GOOD THINGS TO COME

Kemp may have had in mind the forthcoming 2019 Louvre exhibition to mark the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death but no one at the Paris Louvre will now confirm that the Abu Dhabi Louvre Salvator Mundi will be included. Is Paris about to spurn Abu Dhabi’s $450 million acquisition? Failure to include the work next year would risk humiliating the United Arab Emirates (who paid something like Euros 400 million for the right to exploit the Louvre title – roughly the cost of one big yacht) when French foreign policy dictates every deployment of soft cultural power to gain influence in that traditionally Anglophile quarter.

…AND THE UNKOWN UNKNOWNS

Why are so many players so silent on this painting? Why is the art world being kept in this state of darkening paralysis? Some background might help explain the jitters. The art market greatly fears the pending trial in New York between Sotheby’s and the Russian collector Dmitry Rybolovlev who seeks $380 million from the auction house for an alleged conspiracy to defraud him through his own adviser, Yves Bouvier. In 2013 Sotheby’s brokered a private sale of the Salvator Mundi for $80 million to Bouvier, the owner of a string of “tax-efficient” freeports – his Geneva facility alone reputedly holds $100 billion of art. The consortium of vendors claimed that a non-disclosure agreement made with Sotheby’s preventing them from disclosing the picture’s origins. Bouvier immediately sold the painting on (“flipped” in art trade parlance) to Rybolovlev for $127.5 million – an undisclosed mark-up of $47.5 million, with Sotheby’s, reportedly, pocketing $3 million as an agent’s fee. The Swiss police authorities recently detained Rybolovlev for questioning due to “reported allegations of corruption and ‘influence peddling.’ Rybolovlev is allegedly tied to Philippe Narmino, the former justice minister in Monaco, who retired last year after he was accused of working under the influence of the Russian collector in his fraud case against Bouvier…” Earlier, Rybolovlev had filed a complaint against Bouvier in Monaco. The latter was arrested on charges of fraud and money laundering and released on $10 million bail. Bouvier is now reported to be in Singapore. With Rybolovlev furious at being over-charged in 2013, the consortium of vendors who sold indirectly to him for $80 million are thought to remain aggrieved at being short-changed by $47.5 million on the picture’s value and having been pre-emptively blocked from action by a Sotheby’s law suit. Sotheby’s are reportedly seeking assistance from Christie’s in a separate legal fight with a dealer over the sale of a demonstrably and now scientifically-confirmed fake Frans Hals…

THE ART AND ATTRIBUTION STAKES

Unsavory art market churning must not swamp the serious art and attribution concerns at stake with this Salvator Mundi. Modestini’s reported statement to Rosenbaum merits close reading. Her first concerns are the painting’s physical condition, well-being and whereabouts:

“It’s supposed to have been in Switzerland, but I’m not quite convinced, because a conservator who was asked to make a condition report more than a month ago still hadn’t seen it as of last Monday [22 Oct. 2018]. I’m rather worried because although it was framed in a microclimate, it is not a long-term solution. I’m pretty sure it left Christie’s in mid-May. Then it disappeared. It never went to Abu Dhabi… However, the panel is badly damaged and exceptionally reactive to changes in RH [relative humidity]. It needs to be at not less than 45% RH, even though it has some protection because it’s in a microclimate created by sealing it up in an envelope of Marvelseal —a standard technique.”

Modestini’s second concern is professional and personal:

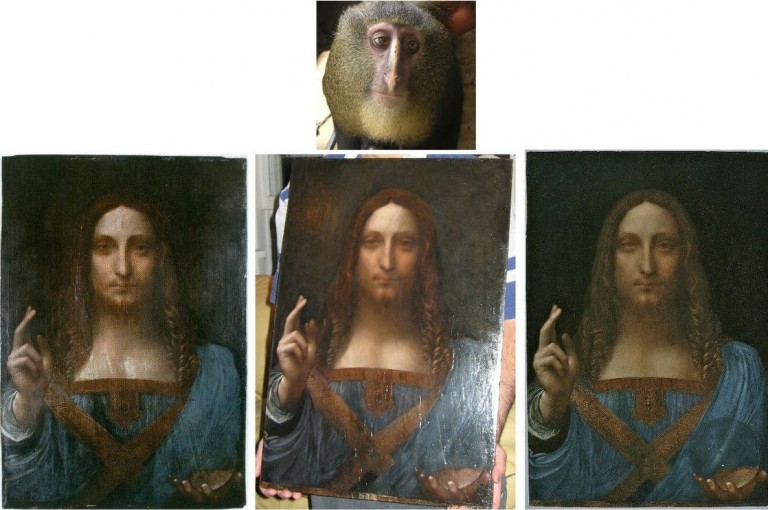

“The Abu Dhabi announcement [that it had postponed display of the painting] had nothing to do with the nonsense about its being 85% by Dianne Modestini and the rest by [Bernardino] Luini. [The Luini theory, advanced by Leonardo scholar Matthew Landrus, was reported by Dalya Alberge in the Guardian and picked up by Smithsonian Magazine, among others.]”

Above, Fig. 3: Left, the Salvator Mundi as restored in 2008; right, a National Gallery painting attributed to Bernardino Luini.

A GREAT FALL-OUT?

It is understandable that Modestini should be sensitive and defensive – no professionally conscientious person enjoys criticism. Following our demonstrations of the extent to which the painting changed appearances at her hand (albeit on the advice of and with support from a high-ranking group of art historical experts) between 2005 and 2017, there are now signs that art historical advocates of the Salvator Mundi may be preparing to disavow the successive restorations to protect the credibility of their attribution. Consider Jonathan Jones’ recent (15 October) account in the Guardian – “The Da Vinci mystery: why is his $450m masterpiece really being kept under wraps?”

Jones, who was the embedded journalist-of-choice within the National Gallery’s conservation department when its version of the Virgin of the Rocks was being restored, bluntly contends that it might have been better if the Salvator Mundi had not been restored at all:

“Surely it would have been more true to the greatest artist who ever lived to let his timeworn masterpiece speak to us directly. Is the Louvre Abu Dhabi taking a closer look? I think it should.”

In this maneuvre, Jones seems to draw support from Martin Kemp, who, along with a few other select experts, had been invited by the National Gallery’s incoming director, Nicholas Penny, to the confidential 2008 viewing of the Salvator Mundi when part repainted, as at Fig. 1:

“When the painting was cleaned, it turned out that Christ had two right thumbs… ‘Both thumbs,’ says Kemp of the raw state, ‘are rather better than the one painted by Dianne.’”

Kemp will likely have known that Modestini had painted out the restoration-exposed second thumb on the advice of Luke Syson, the curator of the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition in which Kemp had been set to have some curatorial input until, as he puts it: “it was later decided that all the curation should be conducted in-house”. Modestini acknowledged Syson’s guidance in her (2014) published account of her restorations preceding the painting’s appearance in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition. Syson, who went to the Metropolitan Musem, New York, has recently been appointed director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. It is possible that had Kemp been co-curator, the National Gallery Leonardo show would have included a second Kemp-supported Leonardo upgrade, the “La Bella Principessa” drawing. In any event, an emboldened Jones has now challenged Robert Simon, one of the original consortium of dealer-owners: “Why didn’t he leave the painting in its raw yet beautiful state after it was stripped down? Wasn’t that an incredible object in itself?” Simon stood firm:

“We considered leaving it, considered more limited restoration, as well as a more extensive one…In the end we decided to do what we felt was best for the picture…we felt that bringing it back to life as much as possible was the way to go.”

Jones reports Simon’s annoyance with criticisms of the restoration – he absolutely rejects the possibility of any artistic “falsehood” being introduced. “I found [Thomas Campbell’s] comments both ill-informed and offensive. ‘Inpainting’ is the right way to describe what has happened here – retouching restricted to areas of loss. In the restoration no original paint was covered.”

(When the picture was sold in November 2017 Thomas Campbell, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum, presciently tweeted that he hoped the anonymous buyer who had just paid $450m “understands conservation issues” and had “read the small print”.)

WHAT WAS DONE IN THE SALVATOR MUNDI RESTORATIONS

The claim never to have over-painted is universally asserted by restorers. While no code of restoration “ethics” sanctions painting over surviving original paint, the profession’s philosophical pieties constantly conflict with observable visual facts. We have previously shown that if you juxtapose halves of the two Salvator Mundi faces, as seen in 2011-12 at the National Gallery and at Christie’s in November 2017 (see Fig. 7 below), there is a mismatch: scarcely any passages of painting run across the halves. As the photo-records below testify, this version of the many Leonardesque Salvator Mundis has enjoyed two distinct identities in seven years and three in ten years. We discuss the unreported covert transition from the second to the third below.

DISPARAGING PHOTO-TESTIMONY

Modestini and Kemp are united on one point: both hold that restorers cannot be held to account by photo-comparisons of the alterations they make to works of art. The claim is untenable – how else might appraisals of restorations be made given that pre-restoration appearances are consumed in restorations? Both the restorer and the art historian further contend that photographs are inherently unreliable because susceptible to malicious manipulation. Modestini offers this variation on that ancient restoration slur:

“I have refrained from commenting on some of the recent articles about the restoration. However, in light of the fact that no one can now see the actual painting, various digital images are standing in for the original, all of which can be manipulated any way one wants and are a sort of falsification of the original.”

That is unworthy. First, why would anyone maliciously tamper with images to make false claims of non-existent injuries that could easily be exposed by the photographic record? How long did it take to expose the Trumpian White House’s tampering with film footage of a journalist’s attempt to retain a microphone? Second, does Modestini mean to imply that the clear photographically recorded differences between the painting’s 2011 and 2017 states are the combined result of malicious critics and auction house promotional manipulations? Modestini’s citation of the second plank of the traditional Restorers’ Defence – that all photographs of paintings are inherently untrustworthy and misleading – is scarcely more credible:

“It is very difficult to photograph any painting accurately, this one especially, because of the many thin layers, subtlety of skin tones, delicacy of transitions etc. Most paintings have three dimensions, not two. That affects our perception of them. I hardly recognize the image that now passes for the ‘Salvator Mundi.’ The photo lamps or strobes (in the case of the Christie’s images) produce a simulacrum of the actual painting, more vivid, sharper, snazzier, if you will, than the actual battered image that I restored as carefully as I could, trying not to invent anything. These flashy images cannot include the nuances and problems created by the three dimensionality of the corrugated surface and are being compared with an only slightly more accurate scan of a good 8×10 transparency of the cleaned state, which was more honest.”

That last image (here at Figs. 5-10) has been published with a drum roll by Jones in the Guardian as if a proof of Leonardo’s hand when it had been published by Modestini in 2014 (albeit small and in printed not online form). Although a considerable improvement on earlier versions (as published by us) it does not tell a different story. On the Jones premise, will Modestini now produce equally high-resolution photographs taken before and after each of her various interventions (2005-08; 2008-11; post 2012 and pre-2017)? If she insists that all photographs are inherently untrustworthy and easily falsifiable, will she explain why so many photographs of paintings are made and published and why they never carry visual health warnings? Are all photographs previously made for restorers’ own restoration reports now deemed to be unreliable testimony?